1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are traumatic events occurring in children below 18 years old which traditionally included ten spectrums: physical, sexual, or emotional abuse; physical or psychological neglect; parental substance abuse or mental illness; parental incarceration; and parental divorce or domestic violence (Felitti et al., 1998). Over the last decade, growing evidence on ACEs has led to an expansion of the traditional ACEs spectrums, extending beyond individual and family-centred trauma to include adversities originating from the broader community and socio-economic conditions, such as discrimination, community violence, bullying, economic hardship, gun violence, war or civil unrest, and global health crisis such as COVID-19 (Felitti et al., 1998; Madigan et al., 2023). Approximately 16% of the global population has greater than four ACEs, while in some low and middle income countries (LMICs), this figure could be as high as 88% driven by factors such as poverty, inadequate healthcare access, and societal instability (Madigan et al., 2023).

ACEs are contributors to the rising global mental health burden, which is especially high in low-income economies (Felitti et al., 1998; Lowell et al., 2011; Madigan et al., 2023). To address the increasing challenges posed by familial, and socio-economic adversities, it is essential to advocate for a shift from the traditional institutional-based mental health treatment services to a community-based mental health approach that prioritizes building community capacity and resources for support and early intervention. The US center for disease control (CDC)’s public health approach to ACEs highlights addressing conditions that cause adversities and meeting the needs of children and parents are essential for preventing ACEs by changing social norms, familial and neighbourhood environments, as well as individual behaviours (Control & Prevention, 2019). Policies mandating ACEs screening, like those in the California State of The US (Shimkhada et al., 2022), and preventive measures endorsed by countries like Scotland (Davidson et al., 2020), highlight the importance of addressing ACEs at the community level.

Policy responses to ACEs are however largely absent in most LMICs. Existing mental health services are often delivered from fragile local health and social systems that lack the skills, resources, and knowledge to manage childhood adversities and mental disorders (Wijayanti & Iqbal, 2023). Poverty, social stigma, and misconceptions often exacerbate the burden of mental disorders among young population (Lowell et al., 2011). Given the resource limitations across LMICs, expanding the roles of lay health workers (LHWs), such as female community health volunteers, lady health workers, peer workers, health promoters/educators, and village health workers, to the delivery of ACEs-focused programs could potentially be a strategy to prevent and manage childhood mental disorders at the local level (Barnett et al., 2018).

However, evidence on feasibility as well as implementation of LHW-led ACEs interventions have not been considered in global health. This paper highlights the potential roles of LHWs in addressing ACEs and feasibility of integrating ACEs-focused programs into existing LHW-led community health frameworks in resource limited settings.

2. Main Text

2.1. LHW-Led Community-Based Mental Health Programs in LMICs

A LHW is a health worker who performs healthcare-related functions but lacks formal professional or paraprofessional certification or a tertiary education degree (World Health Organization, 2018). LHWs play crucial roles in community engagement and delivering essential services, including health education, disease prevention, and basic medical care, often under the supervision of qualified healthcare professionals. Selected from their communities, LHWs are thoroughly trained and supported to be integral members of the public health and primary healthcare workforce across LMICs to successfully provide services in the areas of child health (e.g., immunization, breastfeeding, care for childhood illness), maternal health (e.g., self-care, family planning, healthcare seeking, monitoring), and infectious diseases (e.g., treatment adherence for TB, HIV, Covid 19), as well as general health care services (Lewin et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2014).

Several organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), and Save the Children US, have developed tools and training modules to train and mobilize community-level health workers in recognizing mental health needs, offering psychosocial support and timely referrals to mental health services (Partners In Health, 2021). For instance, a peer-delivered psychosocial intervention, comprising psychoeducation, parenting support, and play activities, was successfully implemented by trained peers, known as mother volunteers, in the resource-poor Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh (from October 2019 to September 2020). The trained mother volunteers conducted weekly 60-minute sessions for small groups of women, showed success in reducing psychological distress and depression among mothers, while also supporting their children's emotional, and cognitive development (Siddique et al., 2022).

In 2014, Tanzanian trained lay counsellors, with assistance from a national trainer, conducted a group-based trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (Psychoeducation, parenting, relaxation, affective modulation, cognitive coping, trauma narrative and processing, in-vivo exposure, and enhancing safety) for orphaned children, which achieved reductions in grief, post-traumatic stress, depression, and behavioral problems related to past traumatic events (O'Donnell et al., 2014). The authors concluded that trained lay counselors delivered the intervention with high fidelity, despite having limited prior mental health experience.

Between May and October 2010, India’s Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) program expanded the roles of community health workers by integrating screening for depression and anxiety symptoms, delivering psychosocial interventions, and educating and facilitating referrals for individuals with (severe) mental health concerns into their maternal and child health program. (Kasturkar et al., 2023; Pathare et al., 2023; Rahul et al., 2021). In rural Pakistan, between April 2005 to March 2006, the Lady Health Workers program included maternal mental health and early childhood development activities, particularly in rural areas where essential mental health services were scarce (Rahman et al., 2008). Engaging LHWs to provide mental health support through home visits and to link families facing mental health challenges to local services have also been pilot-tested in South American countries like Peru, and Brazil (Group; Marchionatti et al., 2023).

Although, previous evidence shows that trained and supervised LHWs can lead the community-based mental health programs in low-resource settings, this evidence mostly comes from specific, early phase, pilot interventions. Additionally, the current community-based mental health service models across LMICs seem to perpetuate a reactive approach to mental health, where the focus remains on managing symptoms rather than preventing them by addressing their root causes. Most of these initiatives primarily focus on the general population and therefore lack targeted interventions for children and their families to address the root causes of mental health burdens rooted in childhood trauma, familial dysfunction or socio-economic harms (Knerr et al., 2013). As Marie-Mitchell and Kostolansky (2019) demonstrated improved intermediate outcomes for interventions mobilizing LHWs, as opposed to professionals, which showed the largest effects (Marie-Mitchell & Kostolansky, 2019), it remains a significant question whether community-based approaches to address ACEs would be effective in resource-limited settings (Mwashala et al., 2022).

2.2. Lay Health Workers’ Roles in Addressing ACEs

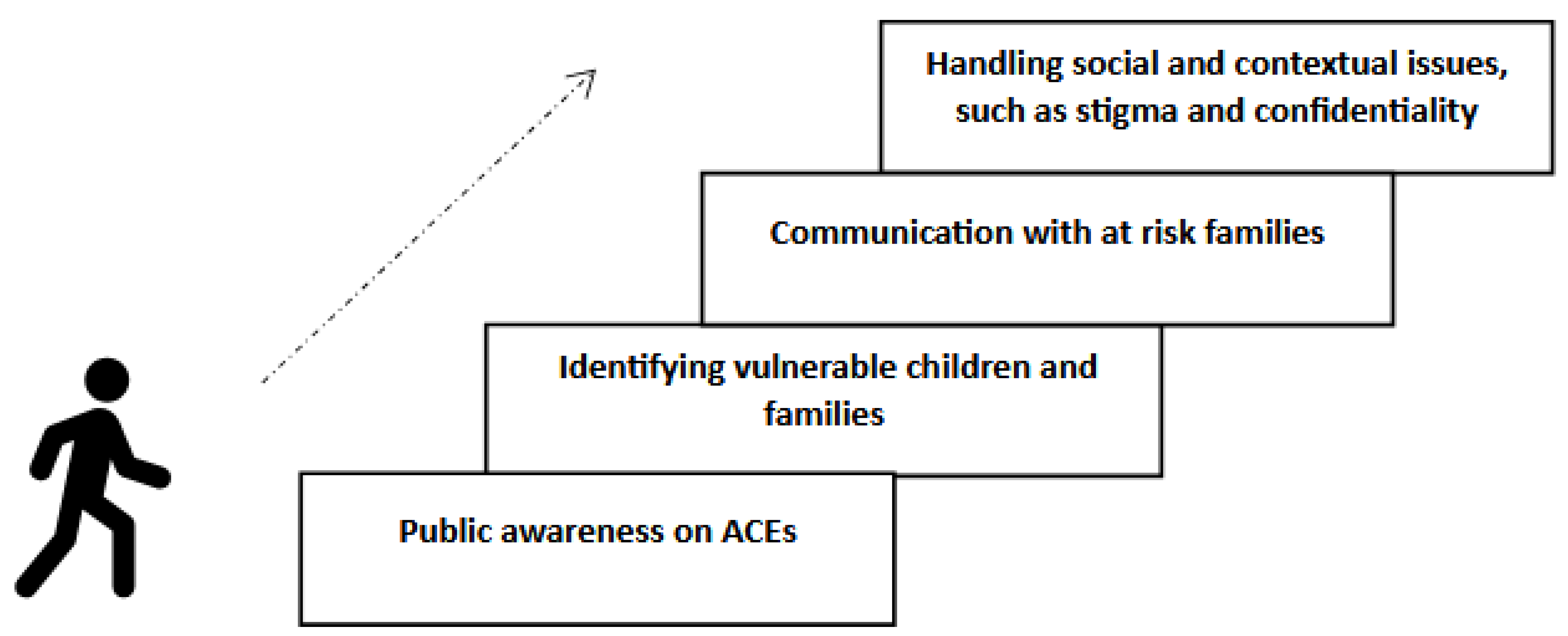

LHWs’ roles that have been noted to have some success in the literature in preventing ACEs and mitigating their harmful impacts include: creating awareness, identifying at risk children and families, educating and empowering families, and addressing underlying social and contextual issues (

Figure 1)(Marie-Mitchell & Kostolansky, 2019).

Traditional parenting practices rooted in harsh discipline, cultural norms, and hierarchical family structures are associated with mental disorders in childhood, including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and behavioural issues (Knerr et al., 2013). To address these problems, WHO underscores the importance of positive parenting practices across LMICs (World Health Organization, 2022), characterized by responsiveness, acceptance, warmth, and age-appropriate discipline (Young et al., 2021). By leveraging their context-specific knowledge, LHWs can play a critical role in promoting awareness regarding the importance of positive childhood experiences and the significance of positive parenting, tailoring programs to align with cultural norms and needs (Lakind & Atkins, 2018). Educating families about ACEs and their impact on physical and mental health can encourage timely support-seeking from mental health professionals (Rajapakse et al., 2020), as well as, addressing unresolved parental trauma and parenting issues can help break intergenerational cycles of harmful behaviour, fostering healthier family environments (Bütikofer et al., 2023).

Nepal’s female health volunteers, often members of women's groups or microfinance collectives, have utilized regular gatherings to discuss positive community experiences, which potentially provides a supportive space for mothers to share experiences about positive parenting practices (e.g., breast feeding, nutrition, education). The women’s group can find ways to fight against the adverse effects of poverty and stress, on poor health outcomes (Cooper et al., 2022). In Pakistan, LHW-led initiatives combining parenting and nutrition interventions demonstrated improvements in maternal caregiving behaviours, leading to parent-child bonds, a decrease in severe punishments, improved interactions between mothers and children and improved early childhood development (Yousafzai et al., 2018).

Several pilot studies have indicated that home visits are generally well-received by families and demonstrated modest results in cognitive and language development, improved parent–child interactions, reduction of child problem behaviours, child maltreatment, and long-term substance use (Johnson et al., 2017; Lowell et al., 2011; Olds et al., 1997). These programs typically involve community-based LHWs, who leverage their shared backgrounds, trust, and rapport with families to conduct ACE screening and awareness initiatives during home visits. In a prospective observational pilot study with 10 participants, DuMont et al. (2007) found that home visiting program for screening and parenting education delivered by family support workers who live in the target community and share the same language and cultural backgrounds positively impacted parenting behaviors, reducing minor physical aggression and harsh parenting (DuMont et al., 2008).

By educating high-risk families with young children on ACEs and positive parenting practices, and providing access to support services, future ACEs may be prevented. LHWs may however face multiple barriers in discussing ACEs with families due to feelings of incompetency, fear of causing more harm, and emotional discomfort. Additionally, the stigma surrounding childhood adversities, such as sexual abuse or mental illness, often prevents families from discussing and seeking help, support and treatment due to fear of criticism or social repercussions (Dumke et al., 2024; Hinshaw, 2005). This is particularly relevant in LMICs, where social norms and economic disparities often obscure trauma and abuse (National Academies of Sciences, 2018).

Manzo et al. (2018)(Manzo et al., 2018), and Counts et al. (2017)(Counts et al., 2017) in their qualitative studies from the US, emphasised on developing skills of LHWs to improve support for and acceptance by families and children. There is US-based evidence that showed that LHW-led, trauma-informed community education program, demonstrated increasing self-efficacy and leadership skills in LHWs, and enabling them to provide parents with individualized care strategies (Burns et al., 2019). Trained LHWs who are empathetic and well-aware of sensitivity of discussion of childhood adversities with families and children can effectively bridge the cultural barriers that often hinder health-seeking behaviours. Their integration into the community and the trust they build are pivotal in addressing misconceptions and stigma (Carrara et al., 2023).

3. Discussion

ACEs-focused community-based mental health services should provide an opportunity to address child mental health comprehensively by fostering community education, enabling early identification, empowering families, and strengthening referral systems (Marie-Mitchell & Kostolansky, 2019). To achieve this across LMICs, community-based mental health programs must train and empower LHWs to recognize signs of trauma and familial dysfunction, incorporate identifying at risk children into existing program frameworks, parenting education and develop health system structures to address trauma-related mental disorders (Goddard, 2021). The incorporation of trauma-informed care into LHW training to enhance their ability to identify trauma-related behaviors, provide immediate support, and connect families to mental health services has been proven effective in pilot studies from African countries, including Ivory Coast, Tanzania and Zambia (Muriuki & Moss, 2016; Murray et al., 2015; O'Donnell et al., 2014).

However, significant structural challenges that need addressing including limited training and resources, minimal professional support, and the lack of robust referral systems (Musoke et al., 2022). While LHWs are well-positioned to identify children and families vulnerable to ACEs, yet their roles are not structured within current community-based mental health programs in LMICs (Partners In Health, 2021). Additionally, navigating this role comes with significant personal challenges, such as maintaining confidentiality. As LHWs often have close personal connections within the communities they serve, this may lead to ethical dilemmas, particularly when sensitive mental health information is involved. Any breaches of confidentiality, whether intentional or unintentional, could undermine trust and compromise the effectiveness of their work, and could lead to emotional strain, burnout, and frustration (Geldsetzer et al., 2017; Søvold et al., 2021).

Addressing these barriers requires continuous training and education, sufficient resources, and systemic support to enhance LHWs' effectiveness and the long-term impact of their interventions A shift toward child-centered health strategies is essential, with a greater emphasis on strengthening family relationships, promoting positive parenting practices, and fostering supportive environments (Control & Prevention, 2019). Moreover, a "system of care" at the primary healthcare level for addressing ACEs and childhood mental disorders, characterized by a comprehensive, individualized, well-integrated, and community-based approach tailored to the strengths, needs, and culture of families, is needed (Murphy et al., 2024).

By embedding LHWs within a well-integrated, community-driven, primary health care, resource-limited settings can begin to address ACEs and reduce subsequent mental disorders effectively, creating a foundation for healthier families and resilient communities. Drawing lessons from existing successful global programs, such as psychoeducation and community referrals, and adapting them to include child-specific and ACE-focused components would maximize the effectiveness of LHW interventions. Policymakers and program developers must recognize the importance of addressing ACEs and prioritize funding, training, and infrastructure development for these efforts.

4. Conclusions

Community-based health initiatives currently fall short in addressing the underlying causes of mental health burdens rooted in childhood adversities and familial dysfunction in LMICs. Given these resource limitations, expanding the roles of LHWs to address ACEs offers a promising strategy for improving childhood mental health and well-being. LHWs can serve as essential first responders, by identifying at-risk children and families, connecting them to information and support and addressing underlying social and contextual issues for long-term outcomes. Important to note is that the success of such interventions depends on providing adequate training, support, and a robust health system to ensure LHWs can manage their responsibilities effectively. When properly empowered, LHWs can potentially be mobilised effectively to address the root causes of mental disorders in children and improve long-term mental health outcomes. The promise is yet to be tested in large-scale studies.

Declaration of competing interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Barnett, M.L.; Lau, A.S.; Miranda, J. Lay Health Worker Involvement in Evidence-Based Treatment Delivery: A Conceptual Model to Address Disparities in Care. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2018, 14, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, B.M.; Merritt, J.; Chyu, L.; Gil, R. The Implementation of Mindfulness-Based, Trauma-Informed Parent Education in an Underserved Latino Community: The Emergence of a Community Workforce. American Journal of Community Psychology 2019, 63, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bütikofer, A. , Ginja, R., Karbownik, K., & Landaud, F. (Breaking) Intergenerational Transmission of Mental Health. The Journal of Human Resources 2023, 59, S108–S151. [Google Scholar]

- Carrara, B.S.; Bobbili, S.J.; Ventura, C.A.A. Community Health Workers and Stigma Associated with Mental Illness: An Integrative Literature Review. Community Mental Health Journal 2023, 59, 132–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Control, C.f.D. , & Prevention (2019). Preventing adverse childhood experiences: Leveraging the best available evidence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,.

- Cooper, J.; Dermentzis, J.; Loftus, H.; Sahle, B.W.; Reavley, N.; Jorm, A. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of parenting programs in real-world settings: A qualitative systematic review. Mental Health & Prevention 2022, 26, 200236. [Google Scholar]

- Counts, J.M.; Gillam, R.J.; Perico, S.; Eggers, K.L. Lemonade for Life—A pilot study on a hope-infused, trauma-informed approach to help families understand their past and focus on the future. Children and Youth Services Review 2017, 79, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.; Critchley, A.; Wright, L.H. Making Scotland an ACE-informed nation. Scottish Affairs 2020, 29, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumke, K.A. , Hamity, C., Peters, K., DiGangi, M., Negriff, S., Sterling, S.A., et al. Pediatric ACEs Screening and Referral: Facilitators, Barriers, and Opportunities for Improvement. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 2024, 17, 877–886. [Google Scholar]

- DuMont, K. , Mitchell-Herzfeld, S., Greene, R., Lee, E., Lowenfels, A., Rodriguez, M., et al. Healthy Families New York (HFNY) randomized trial: effects on early child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl 2008, 32, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J. , Anda, R.F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D.F., Spitz, A.M., Edwards, V., et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldsetzer, P. , Vaikath, M., De Neve, J.-W., Bossert, T.J., Sibandze, S., Mkhwanazi, M., et al. Distrusting community health workers with confidential health information a convergent mixed-methods study in Swaziland. Health Policy and Planning 2017, 32, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, A. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Trauma-Informed Care. J Pediatr Health Care 2021, 35, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, W.B. Healing minds, changing lives : a movement for community-based mental health care in Peru – delivery innovations in a low-income community, 2013-2016. Washington, D.C.

- Hinshaw, S.P. The stigmatization of mental illness in children and parents: developmental issues, family concerns, and research needs. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2005, 46, 714–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. , Woodward, A., Swenson, S., Weis, C., Gunderson, M., Deling, M., et al. Parents' adverse childhood experiences and mental health screening using home visiting programs: A pilot study. Public Health Nurs 2017, 34, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasturkar, P.; Sebastian, S.T.; Gawai, J.; Dukare, K.P.; Uke, T.; Wanjari, M.B. Assessing the Efficacy of Mental Health Assessment Training for Accredited Social Health Activists Workers in Rural India: A Pilot Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e37855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knerr, W.; Gardner, F.; Cluver, L. Improving Positive Parenting Skills and Reducing Harsh and Abusive Parenting in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Prevention Science 2013, 14, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakind, D.; Atkins, M.S. Promoting positive parenting for families in poverty: New directions for improved reach and engagement. Children and Youth Services Review 2018, 89, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, S. , Munabi-Babigumira, S., Glenton, C., Daniels, K., Bosch-Capblanch, X., van Wyk, B.E., et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010, 2010, Cd004015. [Google Scholar]

- Lowell, D.I.; Carter, A.S.; Godoy, L.; Paulicin, B.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Child FIRST: A Comprehensive Home-Based Intervention Translating Research Into Early Childhood Practice. Child Development 2011, 82, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S. , Deneault, A.A., Racine, N., Park, J., Thiemann, R., Zhu, J., et al. Adverse childhood experiences: a meta-analysis of prevalence and moderators among half a million adults in 206 studies. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, R.D.; Rangel, M.I.; Flores, Y.G.; de la Torre, A. A Community Cultural Wealth Model to Train Promotoras as Data Collectors. Health Promotion Practice 2018, 19, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchionatti, L.E.; Rocha, K.B.; Becker, N.; Gosmann, N.P.; Salum, G.A. Mental health care delivery and quality of service provision in Brazil. SSM - Mental Health 2023, 3, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie-Mitchell, A.; Kostolansky, R. A Systematic Review of Trials to Improve Child Outcomes Associated With Adverse Childhood Experiences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2019, 56, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriuki, A.M.; Moss, T. The impact of para-professional social workers and community health care workers in Côte d'Ivoire: Contributions to the protection and social support of vulnerable children in a resource poor country. Children and Youth Services Review 2016, 67, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A. , England, D., Elbarazi, I., Horen, N., Long, T., Ismail-Allouche, Z., et al. The long shadow of accumulating adverse childhood experiences on mental health in the United Arab Emirates: implications for policy and practice. Frontiers in Public Health.

- Murray, L.K. , Familiar, I., Skavenski, S., Jere, E., Cohen, J., Imasiku, M., et al. An evaluation of trauma focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children in Zambia. Child Abuse Negl 2015, 37, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musoke, D. , Nyashanu, M., Bugembe, H., Lubega, G.B., O’Donovan, J., Halage, A.A., et al. Contested notions of challenges affecting Community Health Workers in low- and middle-income countries informed by the Silences Framework. Human Resources for Health 2022, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwashala, W.; Saikia, U.; Chamberlain, D. Instruments to identify risk factors associated with adverse childhood experiences for vulnerable children in primary care in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022, 2, e0000967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, E. , and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; Committee on Law and Justice; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Board on Global Health; Forum on Global Violence Prevention. (2018). The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Addressing the Social and Cultural Norms That Underlie the Acceptance of Violence: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief, N: (DC).

- O'Donnell, K. , Dorsey, S., Gong, W., Ostermann, J., Whetten, R., Cohen, J.A., et al. Treating Maladaptive Grief and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Orphaned Children in Tanzania: Group-Based Trauma-Focused Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2014, 27, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olds, D.L. , Eckenrode, J., Henderson, C.R., Jr., Kitzman, H., Powers, J., Cole, R., et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Jama 1997, 278, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partners In Health. (2021). General training toolkit: sample package of training materials for healthcare providers and community health workers. Partners In Health, Mental Health Program.

- Pathare, S. , Joag, K., Kalha, J., Pandit, D., Krishnamoorthy, S., Chauhan, A., et al. Atmiyata, a community champion led psychosocial intervention for common mental disorders: A stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial in rural Gujarat, India. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0285385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, H.B.; Zulliger, R.; Rogers, M.M. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health 2014, 35, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Malik, A.; Sikander, S.; Roberts, C.; Creed, F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008, 372, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, P. , Chander, K.R., Murugesan, M., Anjappa, A.A., Parthasarathy, R., Manjunatha, N., et al. Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) and Her Role in District Mental Health Program: Learnings from the COVID 19 Pandemic. Community Ment Health J 2021, 57, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, T. , Russell, A.E., Kidger, J., Bandara, P., López-López, J.A., Senarathna, L., et al. Childhood adversity and self-poisoning: A hospital case control study in Sri Lanka. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0242437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimkhada, R.; Miller, J.; Magnan, E.; Miller, M.; Coffman, J.; Corbett, G. Policy Considerations for Routine Screening for Adverse Childhood Events (ACEs). J Am Board Fam Med 2022, 35, 862–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, A. , Islam, A., Mozumder, T.A., Rahman, T., & Shatil, T. (2022). Forced Displacement, Mental Health, and Child Development: Evidence from the Rohingya Refugees.

- Søvold, L.E. , Naslund, J.A., Kousoulis, A.A., Saxena, S., Qoronfleh, M.W., Grobler, C., et al. Prioritizing the Mental Health and Well-Being of Healthcare Workers: An Urgent Global Public Health Priority. Front Public Health 2021, 9, 679397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayanti, A.; Iqbal, M. Assessing the Effectiveness of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Prevention Programmes in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: An Evaluation Review. International Journal of Engineering Business and Social Science 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2018). WHO guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programme. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Regional consultation on parent support for early childhood development and adolescent health in South-East Asia Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Young, M.; Ross, A.; Sheriff, A.; Deas, L.; Gnich, W. Child health interventions delivered by lay health workers to parents: A realist review. J Child Health Care 2021, 25, 628–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousafzai, A.K.; Rasheed, M.A.; Siyal, S. Integration of parenting and nutrition interventions in a community health program in Pakistan: an implementation evaluation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2018, 1419, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).