Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

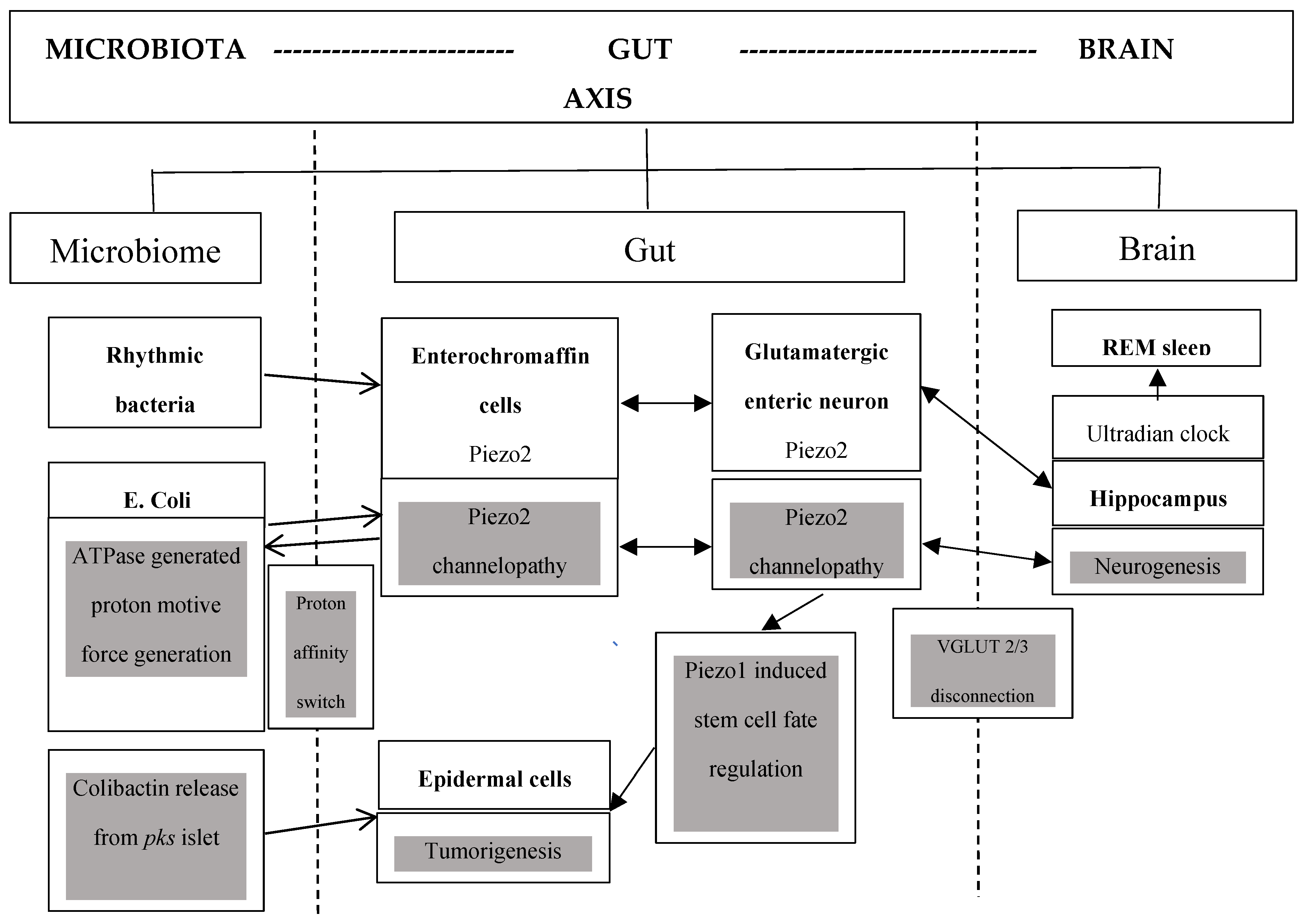

2. Piezo2 Channelopathy, Dysbiosis and Circadian Regulation

3. Colibactin, Escherichia Coli and Piezo2

4. Blue Light Link to Colorectal Cancer

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diaz-Gay, M.; Dos Santos, W.; Moody, S.; Kazachkova, M.; Abbasi, A.; Steele, C.D.; Vangara, R.; Senkin, S.; Wang, J.; Fitzgerald, S., et al. Geographic and age variations in mutational processes in colorectal cancer. Nature 2025, 10.1038/s41586-025-09025-8. [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.K.; Fortin, B.M.; Fellows, R.C.; Habowski, A.N.; Verlande, A.; Song, W.A.; Mahieu, A.L.; Lefebvre, A.; Sterrenberg, J.N.; Velez, L.M., et al. Disruption of the circadian clock drives Apc loss of heterozygosity to accelerate colorectal cancer. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eabo2389. [CrossRef]

- Adnan, D.; Trinh, J.Q.; Sharma, D.; Alsayid, M.; Bishehsari, F. Early-onset Colon Cancer Shows a Distinct Intestinal Microbiome and a Host-Microbe Interaction. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2024, 17, 29-38. [CrossRef]

- Moossavi, S.; Bishehsari, F. Microbes: possible link between modern lifestyle transition and the rise of metabolic syndrome. Obes Rev 2019, 20, 407-419. [CrossRef]

- Bishehsari, F.; Mahdavinia, M.; Vacca, M.; Malekzadeh, R.; Mariani-Costantini, R. Epidemiological transition of colorectal cancer in developing countries: environmental factors, molecular pathways, and opportunities for prevention. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 6055-6072. [CrossRef]

- Ugai, T.; Sasamoto, N.; Lee, H.Y.; Ando, M.; Song, M.; Tamimi, R.M.; Kawachi, I.; Campbell, P.T.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Weiderpass, E., et al. Is early-onset cancer an emerging global epidemic? Current evidence and future implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022, 19, 656-673. [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.H.; Lukacs, V.; de Nooij, J.C.; Zaytseva, D.; Criddle, C.R.; Francisco, A.; Jessell, T.M.; Wilkinson, K.A.; Patapoutian, A. Piezo2 is the principal mechanotransduction channel for proprioception. Nat Neurosci 2015, 18, 1756-1762. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Acquired Piezo2 Channelopathy is One Principal Gateway to Pathophysiology. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2025, 30, 33389. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Cai, S.; Ye, C.; Li, T.; Tian, Y.; Liu, E.; Cai, J.; Yuan, X.; Yang, H.; Liang, Q., et al. Neural influences in colorectal cancer progression and therapeutic strategies. Int J Colorectal Dis 2025, 40, 120. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Is acquired Piezo2 channelopathy the critical impairment of the brain axes and dysbiosis? 2025.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Leung, V.H.; Seradj, S.H.; Sonmez, U.; Servin-Vences, M.R.; Xiao, S.; Ren, X.; Wang, L.; Mishkanian, S.A., et al. A key role of PIEZO2 mechanosensitive ion channel in adipose sensory innervation. Cell Metab 2025, 37, 1001-1011 e1007. [CrossRef]

- Passini, F.S.; Bornstein, B.; Rubin, S.; Kuperman, Y.; Krief, S.; Masschelein, E.; Mehlman, T.; Brandis, A.; Addadi, Y.; Shalom, S.H., et al. Piezo2 in sensory neurons regulates systemic and adipose tissue metabolism. Cell Metab 2025, 37, 987-1000 e1006. [CrossRef]

- Elek, D.; Toth, M.; Sonkodi, B.; Acs, P.; Kovacs, G.L.; Tardi, P.; Melczer, C. The Efficacy of Soleus Push-Up in Individuals with Prediabetes: A Pilot Study. Sports (Basel) 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Rothenberg, M.E.; Sun, X.; Bachert, C.; Artis, D.; Zaheer, R.; Deniz, Y.; Rowe, P.; Cyr, S. Neuroimmune interplay during type 2 inflammation: Symptoms, mechanisms, and therapeutic targets in atopic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2024, 153, 879-893. [CrossRef]

- Buzás, A.; Sonkodi, B.; Dér, A. Principal Connection Between Typical Heart-Rate-Variability Parameters as Revealed by a Comparative Analysis of Their Heart-Rate- and Age-Dependence. In Preprints, Preprints: 2025; 10.20944/preprints202505.0641.v2.

- McDowell, R.; Perrott, S.; Murchie, P.; Cardwell, C.; Hughes, C.; Samuel, L. Oral antibiotic use and early-onset colorectal cancer: findings from a case-control study using a national clinical database. Br J Cancer 2022, 126, 957-967. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wanggou, S.; Bodalia, A.; Zhu, M.; Dong, W.; Fan, J.J.; Yin, W.C.; Min, H.K.; Hu, M.; Draghici, D., et al. A Feedforward Mechanism Mediated by Mechanosensitive Ion Channel PIEZO1 and Tissue Mechanics Promotes Glioma Aggression. Neuron 2018, 100, 799-815 e797. [CrossRef]

- Thaiss, C.A.; Zeevi, D.; Levy, M.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Suez, J.; Tengeler, A.C.; Abramson, L.; Katz, M.N.; Korem, T.; Zmora, N., et al. Transkingdom control of microbiota diurnal oscillations promotes metabolic homeostasis. Cell 2014, 159, 514-529. [CrossRef]

- Reitmeier, S.; Kiessling, S.; Clavel, T.; List, M.; Almeida, E.L.; Ghosh, T.S.; Neuhaus, K.; Grallert, H.; Linseisen, J.; Skurk, T., et al. Arrhythmic Gut Microbiome Signatures Predict Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 258-272 e256. [CrossRef]

- Ubilla, P.K.; Ferrada, E.; Marquet, P.A. Rhythmic Bacteria as Biomarkers for Circadian-Related Diseases. 2025, 10.21203/rs.3.rs-5723754/v1. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zhao, M.; Su, Y.; Liu, S.; Lin, Y.; Da, H.; Yue, C.; Liu, Y.; Jing, D.; Zhao, Q., et al. Chronic Stress Dampens Lactobacillus Johnsonii-Mediated Tumor Suppression to Enhance Colorectal Cancer Progression. Cancer Res 2024, 84, 771-784. [CrossRef]

- McCollum, S.E.; Shah, Y.M. Stressing Out Cancer: Chronic Stress Induces Dysbiosis and Enhances Colon Cancer Growth. Cancer Res 2024, 84, 645-647. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhou, G.; Wang, L.; Xiao, B. Tethering Piezo channels to the actin cytoskeleton for mechanogating via the cadherin-beta-catenin mechanotransduction complex. Cell Rep 2022, 38, 110342. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B.; Resch, M.D.; Hortobagyi, T. Is the Sex Difference a Clue to the Pathomechanism of Dry Eye Disease? Watch out for the NGF-TrkA-Piezo2 Signaling Axis and the Piezo2 Channelopathy. J Mol Neurosci 2022, 72, 1598-1608. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Progressive Irreversible Proprioceptive Piezo2 Channelopathy-Induced Lost Forced Peripheral Oscillatory Synchronization to the Hippocampal Oscillator May Explain the Onset of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Pathomechanism. Cells 2024, 13, 492.

- Sonkodi, B.; Hortobágyi, T. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and delayed onset muscle soreness in light of the impaired blink and stretch reflexes – watch out for Piezo2. Open Medicine 2022, 17, 397-402, doi:doi:10.1515/med-2022-0444.

- Kaci, G.; Goudercourt, D.; Dennin, V.; Pot, B.; Dore, J.; Ehrlich, S.D.; Renault, P.; Blottiere, H.M.; Daniel, C.; Delorme, C. Anti-inflammatory properties of Streptococcus salivarius, a commensal bacterium of the oral cavity and digestive tract. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014, 80, 928-934. [CrossRef]

- Saus, E.; Iraola-Guzman, S.; Willis, J.R.; Brunet-Vega, A.; Gabaldon, T. Microbiome and colorectal cancer: Roles in carcinogenesis and clinical potential. Mol Aspects Med 2019, 69, 93-106. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Miswired Proprioception in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Relation to Pain Sensation (and in Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness)-Is Piezo2 Channelopathy a Principal Transcription Activator in Proprioceptive Terminals Besides Being the Potential Primary Damage? Life (Basel) 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Sun, D. The synthesis of the novel Escherichia coli toxin-colibactin and its mechanisms of tumorigenesis of colorectal cancer. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1501973. [CrossRef]

- Gevorgyan, H.; Baghdasaryan, L.; Trchounian, K. Regulation of metabolism and proton motive force generation during mixed carbon fermentation by an Escherichia coli strain lacking the F(O)F(1)-ATPase. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 2024, 1865, 149034. [CrossRef]

- Homburg, S.; Oswald, E.; Hacker, J.; Dobrindt, U. Expression analysis of the colibactin gene cluster coding for a novel polyketide in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2007, 275, 255-262. [CrossRef]

- Iyadorai, T.; Mariappan, V.; Vellasamy, K.M.; Wanyiri, J.W.; Roslani, A.C.; Lee, G.K.; Sears, C.; Vadivelu, J. Prevalence and association of pks+ Escherichia coli with colorectal cancer in patients at the University Malaya Medical Centre, Malaysia. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0228217. [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.C.; Perez-Chanona, E.; Muhlbauer, M.; Tomkovich, S.; Uronis, J.M.; Fan, T.J.; Campbell, B.J.; Abujamel, T.; Dogan, B.; Rogers, A.B., et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science 2012, 338, 120-123. [CrossRef]

- Buc, E.; Dubois, D.; Sauvanet, P.; Raisch, J.; Delmas, J.; Darfeuille-Michaud, A.; Pezet, D.; Bonnet, R. High prevalence of mucosa-associated E. coli producing cyclomodulin and genotoxin in colon cancer. PLoS One 2013, 8, e56964. [CrossRef]

- Dejea, C.M.; Fathi, P.; Craig, J.M.; Boleij, A.; Taddese, R.; Geis, A.L.; Wu, X.; DeStefano Shields, C.E.; Hechenbleikner, E.M.; Huso, D.L., et al. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis harbor colonic biofilms containing tumorigenic bacteria. Science 2018, 359, 592-597. [CrossRef]

- Desplat, A.; Penalba, V.; Gros, E.; Parpaite, T.; Coste, B.; Delmas, P. Piezo1-Pannexin1 complex couples force detection to ATP secretion in cholangiocytes. J Gen Physiol 2021, 153. [CrossRef]

- Sonkodi, B. Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness Begins with a Transient Neural Switch. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 2319.

- Ren, L.; Meng, L.; Gao, J.; Lu, M.; Guo, C.; Li, Y.; Rong, Z.; Ye, Y. PHB2 promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenesis through NDUFS1-mediated oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, 44. [CrossRef]

- Aisu, Y.; Oshima, N.; Hyodo, F.; Elhelaly, A.E.; Masuo, A.; Okada, T.; Hisamori, S.; Tsunoda, S.; Hida, K.; Morimoto, T., et al. Dual inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis exerts a synergistic antitumor effect on colorectal and gastric cancer by creating energy depletion and preventing metabolic switch. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0309700. [CrossRef]

- Ewald, J.; He, Z.; Dimitriew, W.; Schuster, S. Including glutamine in a resource allocation model of energy metabolism in cancer and yeast cells. NPJ Syst Biol Appl 2024, 10, 77. [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Xu, A.; Yan, H.; Xu, D.; Zhang, J.; Fang, X. PIEZO2 promotes cell proliferation and metastasis in colon carcinoma through the SLIT2/ROBO1/VEGFC pathway. Adv Clin Exp Med 2023, 32, 763-776. [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.M.; Liddle, R.A. Mechanosensing Piezo channels in gastrointestinal disorders. J Clin Invest 2023, 133. [CrossRef]

- Vicente, C.M.; Ricci, R.; Nader, H.B.; Toma, L. Syndecan-2 is upregulated in colorectal cancer cells through interactions with extracellular matrix produced by stromal fibroblasts. BMC Cell Biol 2013, 14, 25. [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Song, H.K.; Hwang, E.S.; Lee, A.R.; Han, D.S.; Kim, S.E.; Oh, E.S. Up-regulation of syndecan-2 in proximal colon correlates with acute inflammation. FASEB J 2019, 33, 11381-11395. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Choi, Y.; Jun, E.; Kim, I.S.; Kim, S.E.; Jung, S.A.; Oh, E.S. Shed syndecan-2 enhances tumorigenic activities of colon cancer cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 3874-3886. [CrossRef]

- Jang, B.; Song, H.K.; Hwang, J.; Lee, S.; Park, E.; Oh, A.; Hwang, E.S.; Sung, J.Y.; Kim, Y.N.; Park, K., et al. Shed syndecan-2 enhances colon cancer progression by increasing cooperative angiogenesis in the tumor microenvironment. Matrix Biol 2022, 107, 40-58. [CrossRef]

- Provencio, I.; Jiang, G.; De Grip, W.J.; Hayes, W.P.; Rollag, M.D. Melanopsin: An opsin in melanophores, brain, and eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 340-345. [CrossRef]

- Wahl, S.; Engelhardt, M.; Schaupp, P.; Lappe, C.; Ivanov, I.V. The inner clock-Blue light sets the human rhythm. J Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201900102. [CrossRef]

- Bevan, R.J.; Hughes, T.R.; Williams, P.A.; Good, M.A.; Morgan, B.P.; Morgan, J.E. Retinal ganglion cell degeneration correlates with hippocampal spine loss in experimental Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2020, 8, 216. [CrossRef]

- Morozumi, W.; Inagaki, S.; Iwata, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Hara, H.; Shimazawa, M. Piezo channel plays a part in retinal ganglion cell damage. Exp Eye Res 2020, 191, 107900. [CrossRef]

- Kassumeh, S.; Weber, G.R.; Nobl, M.; Priglinger, S.G.; Ohlmann, A. The neuroprotective role of Wnt signaling in the retina. Neural Regen Res 2021, 16, 1524-1528. [CrossRef]

- Wahnschaffe, A.; Haedel, S.; Rodenbeck, A.; Stoll, C.; Rudolph, H.; Kozakov, R.; Schoepp, H.; Kunz, D. Out of the lab and into the bathroom: evening short-term exposure to conventional light suppresses melatonin and increases alertness perception. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 2573-2589. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Fremeau, R.T., Jr.; Duncan, J.L.; Renteria, R.C.; Yang, H.; Hua, Z.; Liu, X.; LaVail, M.M.; Edwards, R.H.; Copenhagen, D.R. Vesicular glutamate transporter 1 is required for photoreceptor synaptic signaling but not for intrinsic visual functions. J Neurosci 2007, 27, 7245-7255. [CrossRef]

- Tien, N.W.; Kim, T.; Kerschensteiner, D. Target-Specific Glycinergic Transmission from VGluT3-Expressing Amacrine Cells Shapes Suppressive Contrast Responses in the Retina. Cell Rep 2016, 15, 1369-1375. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, W. A color-coding amacrine cell may provide a blue-off signal in a mammalian retina. Nat Neurosci 2012, 15, 954-956. [CrossRef]

- Ettaiche, M.; Deval, E.; Cougnon, M.; Lazdunski, M.; Voilley, N. Silencing acid-sensing ion channel 1a alters cone-mediated retinal function. J Neurosci 2006, 26, 5800-5809. [CrossRef]

- Friedrichsen, K.; Hsiang, J.C.; Lin, C.I.; McCoy, L.; Valkova, K.; Kerschensteiner, D.; Morgan, J.L. Subcellular pathways through VGluT3-expressing mouse amacrine cells provide locally tuned object-motion-selective signals in the retina. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 2965. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shan, X.; Li, S.; Chang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wang, L.; Liang, F. Retinal light damage: From mechanisms to protective strategies. Surv Ophthalmol 2024, 69, 905-915. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, H.; Xu, Q.; Bu, Y.; Lei, Y. Redox Imbalance in the Development of Colorectal Cancer. J Cancer 2017, 8, 1586-1597. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, D.; Liu, H.; Hu, Y. Calcium homeostasis and cancer: insights from endoplasmic reticulum-centered organelle communications. Trends Cell Biol 2023, 33, 312-323. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; Greten, F.R. The inflammatory pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 2021, 21, 653-667. [CrossRef]

- Zechini, L.; Camilleri-Brennan, J.; Walsh, J.; Beaven, R.; Moran, O.; Hartley, P.S.; Diaz, M.; Denholm, B. Piezo buffers mechanical stress via modulation of intracellular Ca(2+) handling in the Drosophila heart. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 1003999. [CrossRef]

- Ventre, S.; Indrieri, A.; Fracassi, C.; Franco, B.; Conte, I.; Cardone, L.; di Bernardo, D. Metabolic regulation of the ultradian oscillator Hes1 by reactive oxygen species. J Mol Biol 2015, 427, 1887-1902. [CrossRef]

- Hirata, H.; Yoshiura, S.; Ohtsuka, T.; Bessho, Y.; Harada, T.; Yoshikawa, K.; Kageyama, R. Oscillatory expression of the bHLH factor Hes1 regulated by a negative feedback loop. Science 2002, 298, 840-843. [CrossRef]

- Takebayashi, K.; Sasai, Y.; Sakai, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Nakanishi, S.; Kageyama, R. Structure, chromosomal locus, and promoter analysis of the gene encoding the mouse helix-loop-helix factor HES-1. Negative autoregulation through the multiple N box elements. J Biol Chem 1994, 269, 5150-5156.

- Harima, Y.; Imayoshi, I.; Shimojo, H.; Kobayashi, T.; Kageyama, R. The roles and mechanism of ultradian oscillatory expression of the mouse Hes genes. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2014, 34, 85-90. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, S.; Zheng, L.; Ma, F.; Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Li, X. Hes1 promotes cell proliferation and migration by activating Bmi-1 and PTEN/Akt/GSK3beta pathway in human colon cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 38667-38680. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Wang, K.; Shen, K.; Yang, K.; Ni, X.; Liu, X., et al. HES1 promotes aerobic glycolysis and cancer progression of colorectal cancer via IGF2BP2-mediated GLUT1 m6A modification. Cell Death Discov 2023, 9, 411. [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.T.; Tsao, P.N.; Lin, H.L.; Tung, C.C.; Change, M.C.; Chang, Y.T.; Wong, J.M.; Wei, S.C. Hes1 Increases the Invasion Ability of Colorectal Cancer Cells via the STAT3-MMP14 Pathway. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0144322. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ke, J.; He, Z.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Q.; Ai, W.; Wang, G.; Wei, Y.; Zou, X.; Zhang, S., et al. HES1 Promotes Colorectal Cancer Cell Resistance To 5-Fu by Inducing Of EMT and ABC Transporter Proteins. J Cancer 2017, 8, 2802-2808. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.H.; Song, J.W.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Cao, L.; Wan, L.M.; Tan, Y.X.; Ji, S.P.; Liang, Y.M.; Gong, F. The acid-sensing ion channel, ASIC2, promotes invasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer under acidosis by activating the calcineurin/NFAT1 axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2017, 36, 130. [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, C.L.; Szabo, A.; Torok, B.; Banrevi, K.; Correia, P.; Chaves, T.; Daumas, S.; Zelena, D. A New Player in the Hippocampus: A Review on VGLUT3+ Neurons and Their Role in the Regulation of Hippocampal Activity and Behaviour. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Zygulska, A.L.; Furgala, A.; Krzemieniecki, K.; Wlodarczyk, B.; Thor, P. Autonomic dysregulation in colon cancer patients. Cancer Invest 2018, 36, 255-263. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).