Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What were the barriers and facilitators to effective outbreak management in nursing homes?

- What were the key learnings from practice and experience that improved outbreak management in LTRCFs over the multiple waves?

- What are the priority areas for more effective infection prevention and control and future pandemic preparedness in LTRCFs?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search

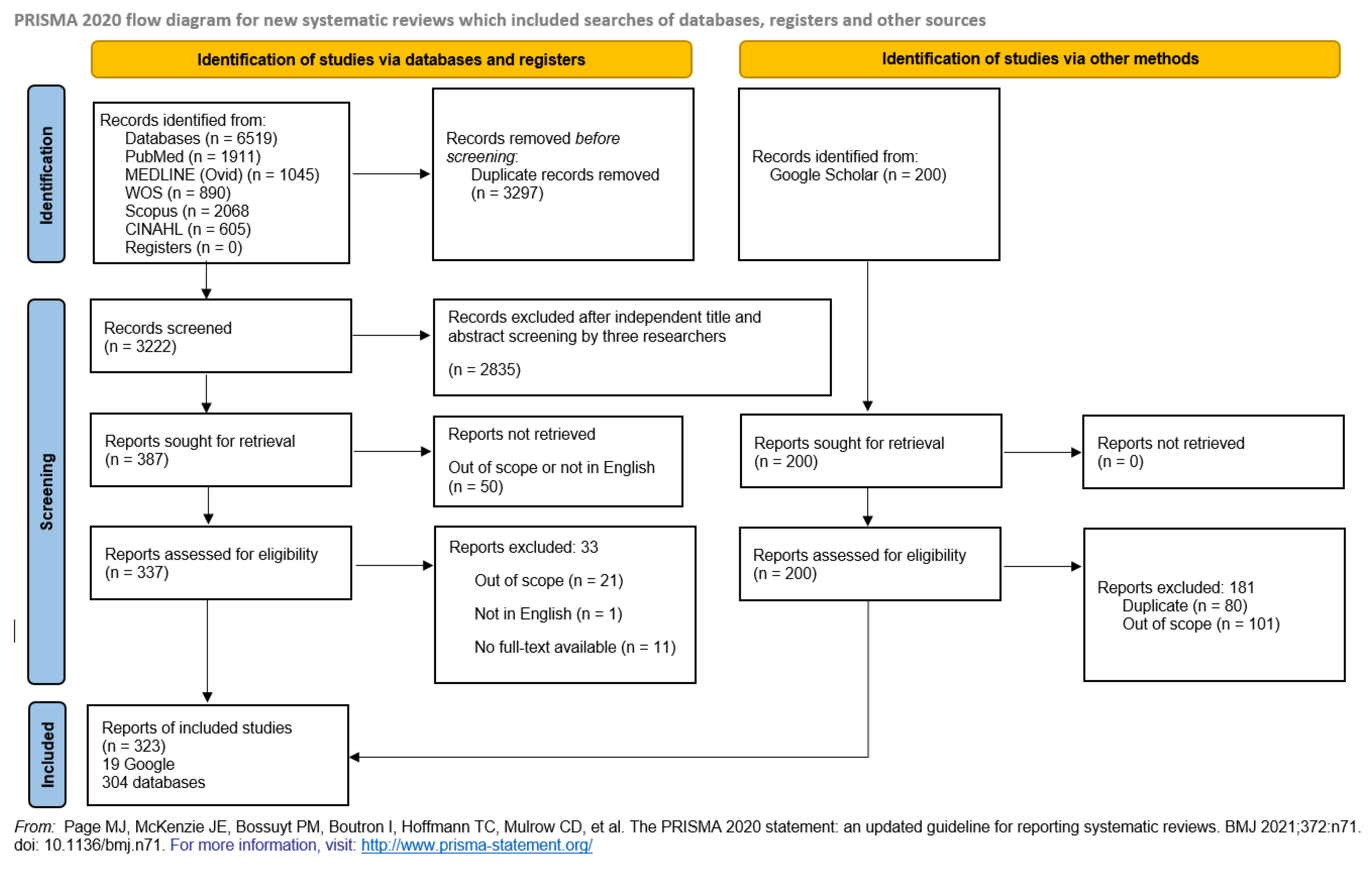

2.5. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.6. Data Charting Process and Data Items

2.7. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

2.8. Synthesis of Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Barriers and Facilitators for Prevention and Management of Outbreaks in LTRCFs

3.2.1. Infection Prevention and Control Challenges and Response to the Pandemic

3.2.2. Social Model of Care and the Built Environment of Nursing Homes

3.2.3. Nursing Home Staffing

3.2.4. Leadership and Staff Practices

3.2.5. Support and Guidance Received During the Pandemic

3.2.6. Learning and Priorities

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- COVID-19 Excess Mortality Collaborators. Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020–2021. Lancet 2022, 399, 1513–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J. Future pandemics are inevitable, but we can reduce the risk. [Internet]. Horizon. The EU Research & Innovation Magazine. 2021 Dec [cited 2024 Aug 24]. Available from: https://projects.research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/en/horizon-magazine/qa-future-pandemics-are-inevitable-we-can-reduce-risk.

- Chidambaram, P. Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief: state reporting of cases and deaths due to COVID-19 in long-term care facilities. Accessed April 26, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-reporting-of-cases-and-deaths-due-to-covid-19-in-long-term-care-facilities/. 26 April.

- ECDC Public Health Emergency Team; Danis, K.; Fonteneau, L.; Georges, S.; Daniau, C.; Bernard-Stoecklin, S.; Domegan, L.; O’Donnell, J.; Hauge, S.H.; Dequeker, S.; et al. High impact of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities, suggestion for monitoring in the EU/EEA, May 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000956. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cazzoletti, L.; Zanolin, M.E.; Tussardi, I.T.; Alemayohu, M.A.; Zanetel, E.; Visentin, D.; Fabbri, L.; Giordani, M.; Ruscitti, G.; Benetollo, P.P.; et al. Risk Factors Associated with Nursing Home COVID-19 Outbreaks: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Jones, A.; Daneman, N.; Chan, A.K.; Schwartz, K.L.; Garber, G.E.; Costa, A.P.; Stall, N.M. Association Between Nursing Home Crowding and COVID-19 Infection and Mortality in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemali, S.; Mari-Sáez, A.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Weishaar, H. Health care workers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Human resources for health. 2022, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner S, Botero-Tovar N, Herrera MA, et al. Systematic review of experiences and perceptions of key actors and organisations at multiple levels within health systems internationally in responding to COVID-19. Implementation Sci. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; Hempel, S. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR), checklist and explanation. Annals of internal medicine. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of advanced nursing. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brainard, J.; Rushton, S.; Winters, T.; Hunter, P.R. Introduction to and spread of COVID-19-like illness in care homes in Norfolk, UK. Journal of Public Health. 2021, 43, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, R.T.; Yun, H.; Casalino, L.P.; Myslinski, Z.; Kuwonza, F.M.; Jung, H.Y.; Unruh, M.A. Comparative performance of private equity–owned US nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA network open. 2020, 3, e2026702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, F.L.; Bacigalupo, I.; Salvi, E.; Lacorte, E.; Piscopo, P.; Mayer, F.; Ancidoni, A.; Remoli, G.; Bellomo, G.; Losito, G. Italian National Institute of Health Nursing Home Study Group. The Italian national survey on Coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic spread in nursing homes. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2021, 36, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, J. Playing the cards we are dealt: covid-19 and nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, B.E.; Grabowski, D.C.; Barnett, M.L. Severe staffing and personal protective equipment shortages faced by nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: study examines staffing and personal protective equipment shortages faced by nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health affairs. 2020, 39, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meershoek, A.; Broek, L.; Crea-Arsenio, M. Perspectives from the Netherlands: Responses from, Strategies of and Challenges for Long-Term Care Health Personnel. Healthcare Policy. 2022, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachholz, P.A.; Jacinto, A.F. Comment on: Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Geriatrics and Long-Term Care: The ABCDs of COVID-19. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68, 1168–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inzitari, M.; Risco, E.; Cesari, M.; Buurman, B.M.; Kuluski, K.; Davey, V.; Bennett, L.; Varela, J.; Prvu Bettger, J. Nursing homes and long term care after COVID-19: A new ERA? The journal of nutrition health aging. 2020, 24, 1042–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Meschiany, G. Who Helped Long-Term Care Facilities and Who Did Not During COVID-19? A Survey of Administrators in Israel. Journal of Aging Social Policy. 2022, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, A.F.; Ling, S.M. COVID-19 in the long-term care setting: the CMS perspective. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68, 1366–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, D.; Perehudof, K.; Younis, M.M.; Zhang, W.H. The Challenges Faced by Nursing Homes During the Early COVID-19 Outbreak. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2022, 34, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.K.; Mclaws, M.L.; Forsyth, D.R. COVID-19 in aged care homes: a comparison of effects initial government policies had in the UK (primarily focussing on England) and Australia during the first wave. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2021, 33, mzab033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowper, B.; Jassat, W.; Pretorius, P.; Geffen, L.; Legodu, C.; Singh, S.; Blumberg, L. COVID-19 in long-term care facilities in South Africa: No time for complacency. SAMJ: South African Medical Journal. 2020, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanaugh, A.M. Suspected recurrent SARS-CoV-2 infections among residents of a skilled nursing facility during a second COVID-19 outbreak—Kentucky, July–November 2020. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, R.F.; Silva, M.B.; Marcos, D.A.; Rosa, C.D.; Wetzel, W.; Delvalle, R. Nursing recommendations for facing dissemination of COVID-19 in Brazilian Nursing Homes. Revista brasileira de enfermagem. 2020, 73 (Suppl. 2), e20200260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehan, A.; Uth, R.; Gadbois, E.A.; Baier, R.R.; Gravenstein, S.; Zullo, A.R.; Kabler, H.; Loiacono, M.M.; Bardenheier, B.H. Impact of COVID-19 on influenza and infection control practices in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2023, 71, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, L. Care homes and COVID-19 in Hong Kong: how the lessons from SARS were used to good effect. Age and ageing. 2021, 50, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Kuo, Y.H.; Chuang, S.T.; Yen, H.R.; Tou, S.I. The experience of executing preventive measures to protect a nursing home in Taiwan from a COVID-19 outbreak. European Geriatric Medicine. 2021, 12, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biven, S.; Hassell, M.; Viegas, M. Remain Vigilant for the Vulnerable! Kentucky Nurse 2021, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Vital COVID lessons ignored. Lamp. 2020;77(5), 12–14. Accessed Aug 27, 2024. https://issuu.com/thelampnswnma/docs/hc_thelamp_octnov20_final.

- Estabrooks, C.A. Staffing for Quality in Canadian Long-Term Care Homes. HealthcarePapers. 2021, 20, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, K.; Mitchell, L.; Stokes, D.; Lacey, E.; Crowley, E.; Kelleher, C.C. A rapid systematic review of measures to protect older people in long-term care facilities from COVID-19. BMJ open. 2021, 11, e047012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, D.M.; Barker, R.T. Single-site employment (multiple jobholding) in residential aged care: A response to COVID-19 with wider workforce lessons. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2022, 41, e298–e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Watts, A.G.; Khan, S.U.; Forsyth, J.; Brown, K.A.; Costa, A.P.; Bogoch, I.I.; Stall, N.M. Impact of a public policy restricting staff mobility between nursing homes in Ontario, Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2021, 22, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lum, T.; Shi, C.; Wong, G.; Wong, K. COVID-19 and long-term care policy for older people in Hong Kong. Journal of Aging Social Policy. 2020, 32, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.R.; Huang, H.C.; Huang, H.C.; Chen, W. Preparing for COVID-19: The experiences of a long-term care facility in Taiwan. Geriatrics Gerontology International. 2020, 20, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnasso, R.; Iommazzo, I.; Corbi, G.; Celi, F.; Iannicelli, A.M.; Ferrara, N.; Ruosi, C. Italian long-term care facilities during COVID-19 era: A review. Journal of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2022, 70, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernadou, A.; Bouges, S.; Catroux, M.; Rigaux, J.C.; Laland, C.; Levêque, N.; Noury, U.; Larrieu, S.; Acef, S.; Habold, D.; Cazenave-Roblot, F. High impact of COVID-19 outbreak in a nursing home in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, France, March to April 2020. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2021, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakaev, I.; Retalic, T.; Chen, H. Universal Testing-Based Response to COVID-19 Outbreak by a Long-Term Care and Post-Acute Care Facility. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, D.J.; Lanzi, M.; Saberi, P.; Love, R.; Linkin, D.R.; Kelly, J.J.; Jhala, D.; Amorosa, V.; Hofmann, M.; Doyon, J.B. Mitigation of a coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in a nursing home through serial testing of residents and staff. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2021, 72, e394–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.; Jenq, G.; Mills, J.P.; Beal, J.; Diviney Chun, E.; Newton, D.; Gibson, K.; Mantey, J.; Hurst, K.; Jones, K.; Mody, L. Partnering with local hospitals and public health to manage COVID-19 outbreaks in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2021, 69, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollner-Schwetz, I.; König, E.; Krause, R.; Pux, C.; Laubreiter, L.; Schippinger, W. Analysis of COVID-19 outbreaks in 3 long-term care facilities in Graz, Austria. American Journal of Infection Control. 2021, 49, 1350–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davó, L.; Seguí, R.; Botija, P.; Beltrán, M.J.; Albert, E.; Torres, I.; López-Fernández, P.Á.; Ortí, R.; Maestre, J.F.; Sánchez, G.; Navarro, D. Early detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection cases or outbreaks at nursing homes by targeted wastewater tracking. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2021, 27, 1061–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricic, T.; Nickel, O.; Aximu-Petri, A.; Essel, E.; Gansauge, M.; Kanis, P.; Macak, D.; Richter, J.; Riesenberg, S.; Bokelmann, L.; Zeberg, H. A direct RT-qPCR approach to test large numbers of individuals for SARS-CoV-2. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0244824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA News Release, FDA Approves First COVID-19 Vaccine, Approval Signifies Key Achievement for Public Health (For Immediate Release: August 23, 2021) URL: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-COVID-19-vaccine#:~:text=Since%20Dec.,age%20on%20May%2010%2C%202021. Accessed on July 29th, 2024.

- Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Petrovic, M.; Pei, X.; Tian, Q.B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and corresponding control measures on long-term care facilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age and Ageing. 2023, 52, afac308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigl, J.A.; Werlang, T.; Wessendorf, M.; Helbing, H. Vaccine-masked spread of SARS-CoV2 in an elderly care home, and how to prevent a spill-over into the general population. Journal of Public Health. 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, T.; Tucker, M.; Gray, C.; Lee, K.; Modina, K.; Gray, Z. Lessons learned in preventing COVID-19 within a skilled nursing facility during the early pandemic. Geriatric Nursing. 2021, 42, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilches, T.N.; Nourbakhsh, S.; Zhang, K.; Juden-Kelly, L.; Cipriano, L.E.; Langley, J.M.; Sah, P.; Galvani, A.P.; Moghadas, S.M. Multifaceted strategies for the control of COVID-19 outbreaks in long-term care facilities in Ontario, Canada. Preventive medicine. 2021, 148, 106564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouslander, J.G.; Saliba, D. Early success of COVID-19 vaccines in nursing homes: Will it stick? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2021, 69, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbalayen, F.; Dutheillet-de-Lamothe, V.; Letty, A.; Le Bruchec, S.; Pondjikli, M.; Berrut, G.; Benatia, L.; Ndiongue, B.M.; Fourrier, M.A.; Armaingaud, D.; Josseran, L. The COVID-19 pandemic and responses in nursing homes: a cross-sectional study in four European countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022, 19, 15290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aykaç, N.; Yüksel Eryiğit, Ö.; Elbek, O. Evaluation Of The Measures Taken In Nursing Homes Of The Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality During The Covid-19 Pandemic. Turkish Journal of Geriatrics/Türk Geriatri Dergisi. 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, J.; Tort, S. What are the effects of COVID-19 entry regulation measures in long-term care facilities (LTCFs)? Cochrane Clinical Answers. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, C.; Stall, N.M.; Haimowitz, D.; Aronson, L.; Lynn, J.; Steinberg, K.; Wasserman, M. Recommendations for welcoming back nursing home visitors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a Delphi panel. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020, 21, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosch, M.; Heppner, H.J.; Singler, K. Recommendations for the management of COVID-19 pandemic in long term care facilities. MMW-Fortschritte der Medizin. 2021, 163, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Coronavirus kills 32 residents in Seattle nursing homes: More testing likely to reveal many milder cases. Hospital Infection Control and Prevention. 2020, 47. [Google Scholar]

- American Geriatrics Society. American Geriatrics Society (AGS) policy brief: COVID-19 and assisted living facilities. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, G.E.; Holmes, A.L.; Ibrahim, J.E. COVID-19 and residential aged care: priorities for optimising preparation and management of outbreaks. Medical Journal of Australia. 2021, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, H.R.; Loomer, L.; Gandhi, A.; Grabowski, D.C. Characteristics of US nursing homes with COVID-19 cases. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, J.K.; McMinn, M.; Vaughan, J.E.; Fleuriot, J.; Guthrie, B. Care-home outbreaks of COVID-19 in Scotland March to May 2020: national linked data cohort analysis. Age and Ageing. 2021, 50, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, S.; Dumond-Stryker, C.; Tandan, M.; Preisser, J.S.; Wretman, C.J.; Howell, A.; Ryan, S. Nontraditional small house nursing homes have fewer COVID-19 cases and deaths. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2021, 22, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinspun, D.; Matthews, J.H.; Bonner, R.; Moreno-Casbas, T.; Mo, J. COVID-19 pandemic in long-term care: an international perspective for policy considerations. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2023, 10, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.C.; Grey, T.; Kennelly, S.; O’Neill, D. Nursing home design and COVID-19: balancing infection control, quality of life, and resilience. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020, 21, 1519–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, J. COVID-19 crisis advances efforts to reimagine nursing homes. JAMA. 2021, 326, 1568–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, G.L. COVID-19 in a Sydney nursing home: a case study and lessons learnt. The Medical Journal of Australia 2020, 213, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barasteh, S.; Azimi, A.V.; Khademi, F.; Goharinezhad, S.; Rassouli, M. Covid-19 and nursing home residents: The potential role of geriatric nurses in a special crisis. Nursing Practice Today. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longmore, M. COVID-19 exposes weaknesses in aged care. Kai Tiaki: Nursing New Zealand 2020, 26, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cigler, B.A. Nursing Homes and COVID-19: One State’s Experience. International Journal of Public Administration. 2021, 44, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuylsteke, B.; Cuypers, L.; Baele, G.; Stranger, M.; Paralovo, S.L.; André, E.; Laga, M. The role of airborne transmission in a large single source outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 in a Belgian nursing home in 2020. Epidemics 2022, 40, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Use the environment to prevent and control COVID-19 in senior-living facilities: An analysis of the guidelines used in China. HERD: Health Environments Research Design Journal. 2021, 14, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brass, A.; Shoubridge, A.P.; Larby, N.; Elms, L.; Sims, S.K.; Flynn, E.; Miller, C.; Crotty, M.; Papanicolas, L.E.; Wesselingh, S.L.; Morawska, L. Targeted reduction of airborne viral transmission risk in long-term residential aged care. Age and ageing. 2022, 51, afac316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Man, P.; Paltansing, S.; Ong, D.S.; Vaessen, N.; van Nielen, G.; Koeleman, J.G. Outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a nursing home associated with aerosol transmission as a result of inadequate ventilation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2021, 73, 170–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barretto Filho, A.C.; Salotto, D.B.; Schoueri, J.F.; Tsutsui, J.M.; Granato, C.F.; Yamaguchi, M.B.; Carvalho, R.D.; Zacarias, N.; Marcelino, A.S.; Rabelo, R.; Jacob Filho, W. COVID-19 containment management strategies in a nursing home. einstein (São Paulo). 2022, 20, eAO6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, R.M.; Goring, R. Practical steps to improve air flow in long-term care resident rooms to reduce COVID-19 infection risk. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020, 21, 893–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykgraaf, S.H.; Matenge, S.; Desborough, J.; Sturgiss, E.; Dut, G.; Roberts, L.; McMillan, A.; Kidd, M. Protecting nursing homes and long-term care facilities from COVID-19: a rapid review of international evidence. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2021, 22, 1969–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, A.; Hollmann, P.; Lundebjerg, N.; et al. American Geriatrics Society. American Geriatrics Society policy brief: COVID-19 and nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68, 908–911. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Prevention is key to reducing the spread of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2022, 6689–6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackman, C.; Farber, S.; Feifer, R.A.; Mor, V.; White, E.M. An illustration of SARS-CoV-2 dissemination within a skilled nursing facility using heat maps. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68, 2174–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aged care: Inconsistent use of, P.P.E. Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand. 2020;26(8), 43. Accessed on Aug 25, 2024. https://issuu.com/kaitiaki/docs/kai_tiaki_september_2020.

- Covid-19 News. Australian Journal of Dementia Care. (2021) 10(2), 8. Accessed Aug 25, 2024. https://journalofdementiacare.com/journal-issues/supporting-meaningful-activity-in-hospital/.

- Blain, H.; Rolland, Y.; Schols, J.M.; Cherubini, A.; Miot, S.; O’Neill, D.; Martin, F.C.; Guérin, O.; Gavazzi, G.; Bousquet, J.; Petrovic, M. August 2020 interim EuGMS guidance to prepare European long-term care facilities for COVID-19. European geriatric medicine. 2020, 11, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, J.E.; Li, Y.; McKee, G.; Eren, H.; Brown, C.; Aitken, G.; Pham, T. Characteristics of nursing homes associated with COVID-19 outbreaks and mortality among residents in Victoria, Australia. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2021, 40, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Mantey, J.; Washer, L.; Meddings, J.; Patel, P.K.; Montoya, A.; Mody, L. When planning meets reality: COVID-19 interpandemic survey of Michigan Nursing Homes. American Journal of Infection Control 2021, 49, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillemer, K.; Subramanian, L.; Hupert, N. The importance of long-term care populations in models of COVID-19. Jama. 2020, 324, 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu, M.; Genesse, J.C.; St-Martin, K. High death rate of older persons from COVID-19 in Quebec (Canada) long-term care facilities: Chronology and analysis. The Journal of Adult Protection 2021, 23, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, R.; Han, X.; Yaraghi, N. Compress the curve: a cross-sectional study of variations in COVID-19 infections across California nursing homes. BMJ open. 2021, 11, e042804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aïdoud, A.; Poupin, P.; Gana, W.; Nkodo, J.A.; Debacq, C.; Dubnitskiy-Robin, S.; Fougère, B. Helping nursing homes to manage the COVID-19 crisis: an illustrative example from France. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68, 2475–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotty, F.; Watson, R.; Lim, W.K. Nursing homes: the titanic of cruise ships–will residential aged care facilities survive the COVID-19 pandemic? Internal medicine journal. 2020, 50, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, J.K.; Stoltey, J.; Scott, H.M.; DuBois, A.; Golden, L.; Philip, S.; Aragón, T.J. Early COVID-19 successes in skilled nursing facilities in San Francisco.

- Bakerjian, D.; Boltz, M.; Bowers, B.; Gray-Miceli, D.; Harrington, C.; Kolanowski, A.; Mueller, C.A. Expert nurse response to workforce recommendations made by the coronavirus commission for safety and quality in nursing homes. Nursing outlook. 2021, 69, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.R.; Dunn, D.; Greenberg, S.A.; Shaughnessy, M. Infection Control in Long-Term Care: An Old Problem and New Priority. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2022, 23, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boltz, M. Long-Term Care and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learned. Nursing Clinics. 2023, 58, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Eichner, L.; Schlegel, C.; Roller, G.; Fischer, H.; Gerdes, R.; Sauerbrey, F.; Schönleber, S.; Weinhart, F.; Eichner, M. COVID-19 case findings and contact tracing in South German nursing homes. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2022, 22, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, M.; Cao, S.; Mi, J.; Yu, X.; Zhao, Q. Nursing Home in the COVID-19 Outbreak: Challenge, Recovery, and Resiliency. Journal of gerontological social work. 2020, 63, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heudorf, U.; Müller, M.; Schmehl, C.; Gasteyer, S.; Steul, K. COVID-19 in long-term care facilities in Frankfurt am Main, Germany: incidence, case reports, and lessons learned. GMS hygiene and infection control 2020, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Kimball A, Hatfield KM, Arons M, James A, Taylor J, Spicer K, et al. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in residents of a long-term care skilled nursing facility — King County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020, 69, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eye of the Storm. Lamp. 2020;77(3), 14–17. Accessed Aug 27, 2024. https://issuu.com/thelampnswnma/docs/hc_thelamp_junejuly20_fa3.

- Esper, J.J.; Garg, D.; McClafferty, B.R.; Golamari, R.; Jain, R. COVID-19 Isolation and Quarantine Guidelines for Older Adults in Nursing Homes. South Dakota Medicine. 2021, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, P.E.; Holahan, T.; Siskind, D.; Healy, E. Policy recommendations regarding skilled nursing facility management of coronavirus 19 (COVID-19), lessons from New York state. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020, 21, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnedo-Pena, A.; Romeu-Garcia, M.A.; Gascó-Laborda, J.C.; Meseguer-Ferrer, N.; Safont-Adsuara, L.; Prades-Vila, L.; Flores-Medina, M.; Rusen, V.; Tirado-Balaguer, M.D.; Sabater-Vidal, S.; Gil-Fortuño, M. Incidence, mortality, and risk factors of COVID-19 in nursing homes. Epidemiologia. 2022, 3, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghili, M.S.; Darvishpoor Kakhki, A.; Gachkar, L.; Davidson, P.M. Predictors of contracting COVID-19 in nursing homes: Implications for clinical practice. Journal of advanced nursing. 2022, 78, 2799–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Hamad, H.; Malkawi, M.M.; Al Ajmi, J.A.; Al-Mutawa, M.N.; Doiphode, S.H.; Sathian, B. Investigation of a COVID-19 outbreak and its successful containment in a long term care facility in Qatar. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021, 9, 779410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dora, A.V. Universal and serial laboratory testing for SARS-CoV-2 at a long-term care skilled nursing facility for veterans—Los Angeles, California, 2020. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2020, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.L.; Goodman, C.; Achterberg, W.; Barker, R.O.; Burns, E.; Hanratty, B.; Martin, F.C.; Meyer, J.; O’Neill, D.; Schols, J.; Spilsbury, K. Commentary: COVID in care homes—challenges and dilemmas in healthcare delivery. Age and ageing. 2020, 49, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.M.; Wetle, T.F.; Reddy, A.; Baier, R.R. Front-line nursing home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2021, 22, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.F.; Li, M.Q.; Liao, L.L.; Feng, H.; Zhao, S.; Wu, S.; Yin, P. A qualitative study of the first batch of medical assistance team’s first-hand experience in supporting the nursing homes in Wuhan against COVID-19. Plos one. 2021, 16, e0249656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, J.; Neckelmann, M.; Dintrans, P.V.; Salas, J.B. Improving long-term care facilities’ crisis response: Lessons from the COVID-19 in Chile. Journal of Long-Term Care 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambury, N.; Barrett, P.M.; Crompton, J.; O’Mahony, M.T.; O’Sullivan, M.B.; Murray, D.E.; Foley Nolan, C.; Sheahan, A. Practicalities and Yield from Mass Swabbing for COVID-19 in Residential Care Facilities in the South of Ireland. Journal of Aging Social Policy. 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, T.; Bellin, E.; Ehrlich, A.R. Older adults and Covid-19: The most vulnerable, the hardest hit. Hastings Center Report. 2020, 50, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Peromingo, J.; Serra-Rexach, J.A. Long-Term Care Facilities and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learned in Madrid. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baughman, A.W.; Renton, M.; Wehbi, N.K.; Sheehan, E.J.; Gregorio, T.M.; Yurkofsky, M.; Levine, S.; Jackson, V.; Pu, C.T.; Lipsitz, L.A. Building community and resilience in Massachusetts nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2021, 69, 2716–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Temkin-Greener, H.; Shan, G.; Cai, X. COVID-19 infections and deaths among Connecticut nursing home residents: facility correlates. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68, 1899–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanowski, A.; Cortes, T.A.; Mueller, C.; Bowers, B.; Boltz, M.; Bakerjian, D.; Harrington, C.; Popejoy, L.; Vogelsmeier, A.; Wallhagen, M.; Fick, D. A call to the CMS: Mandate adequate professional nurse staffing in nursing homes. AJN The American Journal of Nursing. 2021, 121, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, M.J.; La Delfa, A.; Sawhney, M.; Adams, D.; Abdel-Shahied, K.; Belfer, T.; Schembri, J.; Katz, K. Implementation and evaluation of an IPAC SWAT team mobilized to long-term care and retirement homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A pragmatic health system innovation. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2021, 22, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. National COVID-19 Residential Aged Care Emergency Communication Guide. 2021, 10(4), 39. Accessed Aug 28, 2024. www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/09/national-covid-19-residential-aged-care-emergency-communication-guide.

- 70(8), 273.

- Championing education for COVID-19. (2020) Lamp. 77(6), 31. Accessed Aug 28, 2024. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit. 3324.

- Cofais, C.; Veillard, D.; Farges, C.; Baldeyrou, M.; Jarno, P.; Somme, D.; Corvol, A. COVID-19 epidemic: Regional organization centered on nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020, 68, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colas, A.; Baudet, A.; Regad, M.; Conrath, E.; Colombo, M.; Florentin, A. An unprecedented and large-scale support mission to assist residential care facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infection Prevention in Practice. 2022, 4, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Maxwell, C.J.; Armstrong, P.; Schwandt, M.; Moser, A.; McGregor, M.J.; Bronskill, S.E.; Dhalla, I.A. COVID-19 in long-term care homes in Ontario and British Columbia. Cmaj. 2020, 192, E1540–E1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni Chroinin, D.; Patil, A. Geriatric outreach to residential aged care: Embracing a dynamic approach in the COVID-19 era. Australas J Ageing. 2020, 39, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.; Chenn, L.M.; Romero-Ortuno, R. Nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review of challenges and responses. European Geriatric Medicine. 2021, 12, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.J.; Monsen, K.A.; Jeppesen, B.; Hanson, C.; Nichols, K.; O’Neill, K.; Lundblad, J. Interprofessional roles and collaborations to address COVID-19 pandemic challenges in nursing homes. Interdisciplinary journal of partnership studies. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poupin, P.; N’diaye, D.; Chaumier, F.; Lemaignen, A.; Bernard, L.; Fougère, B. Management of COVID-19 in a French nursing home: experiences from a multidisciplinary mobile team. The Journal of Frailty Aging. 2021, 10, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, L.L.; Naylor, M.D. “We are alone in this battle”: a framework for a coordinated response to COVID-19 in nursing homes. Journal of aging social policy. 2020, 32, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arons, M.M.; Hatfield, K.M.; Reddy, S.C.; Kimball, A.; James, A.; Jacobs, J.R.; Taylor, J.; Spicer, K.; Bardossy, A.C.; Oakley, L.P.; Tanwar, S. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. New England journal of medicine. 2020, 382, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, G.V. Initial and repeated point prevalence surveys to inform SARS-CoV-2 infection prevention in 26 skilled nursing facilities—Detroit, Michigan, March–May 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2020, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.C.; Chaisson, L.H.; Borgetti, S.; Burdsall, D.; Chugh, R.K.; Hoff, C.R.; Murphy, E.B.; Murskyj, E.A.; Wilson, S.; Ramos, J.; Akker, L. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 mortality during an outbreak investigation in a skilled nursing facility. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020, 71, 2920–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.K.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.I.; Peck, K.R. A systematic narrative review of comprehensive preparedness strategies of healthcare resources for a large resurgence of COVID-19 nationally, with local or regional epidemics: present era and beyond. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2020, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, G.; Bélanger-Gravel, A.; Eccles, M.; Grimshaw, J. Healthcare professionals’ intentions and behaviours: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implementation science. 2008, 3, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedson, J.; Skrip, L.A.; Pedi, D.; Abramowitz, S.; Carter, S.; Jalloh, M.F.; Funk, S.; Gobat, N.; Giles-Vernick, T.; Chowell, G.; de Almeida, J.R. A review and agenda for integrated disease models including social and behavioural factors. Nature human behaviour. 2021, 5, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group; Houghton, C.; Meskell, P.; Delaney, H.; Smalle, M.; Glenton, C.; Booth, A.; Chan, X.H.; Devane, D.; Biesty, L.M. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers’ adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: a rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 1996, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, N.C.; Goh, L.G.; Lee, S.S. Family physicians’ experiences, behaviour, and use of personal protection equipment during the SARS outbreak in Singapore: do they fit the Becker Health Belief Model? Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health / Asia-Pacific Academic Consortium for Public Health 2006, 18, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, A.; Hammond, N.E.; Fraser, J.F. The experiences of health care workers employed in an Australian intensive care unit during the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009: a phenomenological study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2010, 47, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, O. Barriers to the implementation of tuberculosis infection control among South African healthcare workers - Emerging Public Health Practitioner Awards. South African Health Review 2012, 2012/2013, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, H.J.; Veras-Estevez, B.A.; Pomeranz, J.L.; Perez-Then, E.N.; Marcelino Bs Lauzardo, M. Perceived barriers to adherence to tuberculosis infection control measures among health care workers in the Dominican Republic. MEDICC Review 2017, 19, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Woith, W.; Volchenkov, G.; Larson, J. Barriers and motivators affecting tuberculosis infection control practices of Russian health care workers. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2012, 16, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinatsa, F.; Engelbrecht, M.; Van Rensburg, A.J.; Kigozi, G. Voices from the frontline: barriers and strategies to improve tuberculosis infection control in primary health care facilities in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research 2018, 18, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore D, Gamage B, BE, Copes R, Yassi A, BC Interdisciplinary Respiratory Protection Study Group. Protecting health care workers from SARS and other respiratory pathogens: organizational and individual factors that affect adherence to infection control guidelines. American Journal of Infection Control 2005, 33, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.K.K.; Kwong, E.W.Y.; Hung, M.S.Y.; Pang, S.M.C.; Chiang, V.C.L. Nurses’ preparedness for infectious disease outbreaks: A literature review and narrative synthesis of qualitative evidence. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2018, 27, e1244–e1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, K.A.; Liuzzi, F.; Irvine, S.; Thompson, A.; Hepworth, E.; Hoyle, M.C.; Cruise, J.; Hine, P.; Walker, N.F. A ‘train the trainers’ approach to infection prevention and control training in pandemic conditions. Clinical Infection in Practice. 2023, 19, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Sánchez, E.; Alexander, C.M.; Atchison, C.; Patel, D.; Leung, W.; Calamita, M.E.; Garcia, D.M.; Cimpeanu, C.; Mumbwatasai, J.M.; Ramid, D.; Doherty, K. Evaluation of a personal protective equipment support programme for staff during the COVID-19 pandemic in London. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2021, 109, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nexø, M.A.; Kingod, N.R.; Eshøj, S.H.; Kjærulff, E.M.; Nørgaard, O.; Andersen, T.H. The impact of train-the-trainer programs on the continued professional development of nurses: a systematic review. BMC Medical Education. 2024, 24, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penna, A.R.; Hunter, J.C.; Sanchez, G.V.; Mohelsky, R.; Barnes, L.E.; Benowitz, I.; Crist, M.B.; Dozier, T.R.; Elbadawi, L.I.; Glowicz, J.B.; Jones, H. Evaluation of a Virtual Training to Enhance Public Health Capacity for COVID-19 Infection Prevention and Control in Nursing Homes. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2022, 28, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Yanagi, U.; Kagi, N.; Kim, H.; Ogata, M.; Hayashi, M. Environmental factors involved in SARS-CoV-2 transmission: effect and role of indoor environmental quality in the strategy for COVID-19 infection control. Environmental health and preventive medicine. 2020, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Lee, H.; Sang, H.; Muller, J.; Yang, H.; Lee, C.; Ory, M. Nursing home design and COVID-19: implications for guidelines and regulation. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2022, 23, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. 2020.

- World Health Organization. Infection prevention and control guidance for long-term care facilities in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance, 8 January 2021. World Health Organization; 2021.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).