Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

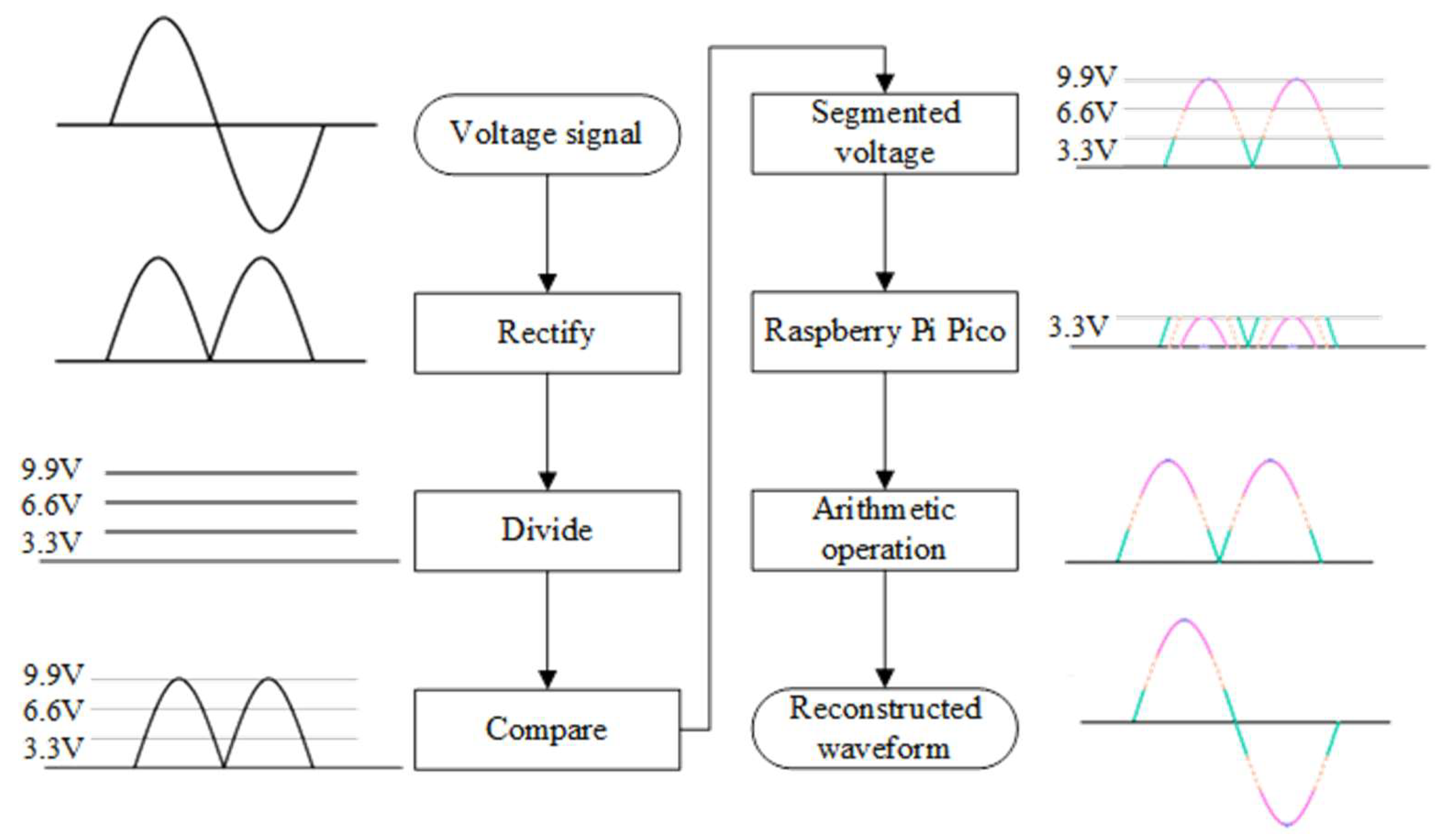

2. Acquisition Principle

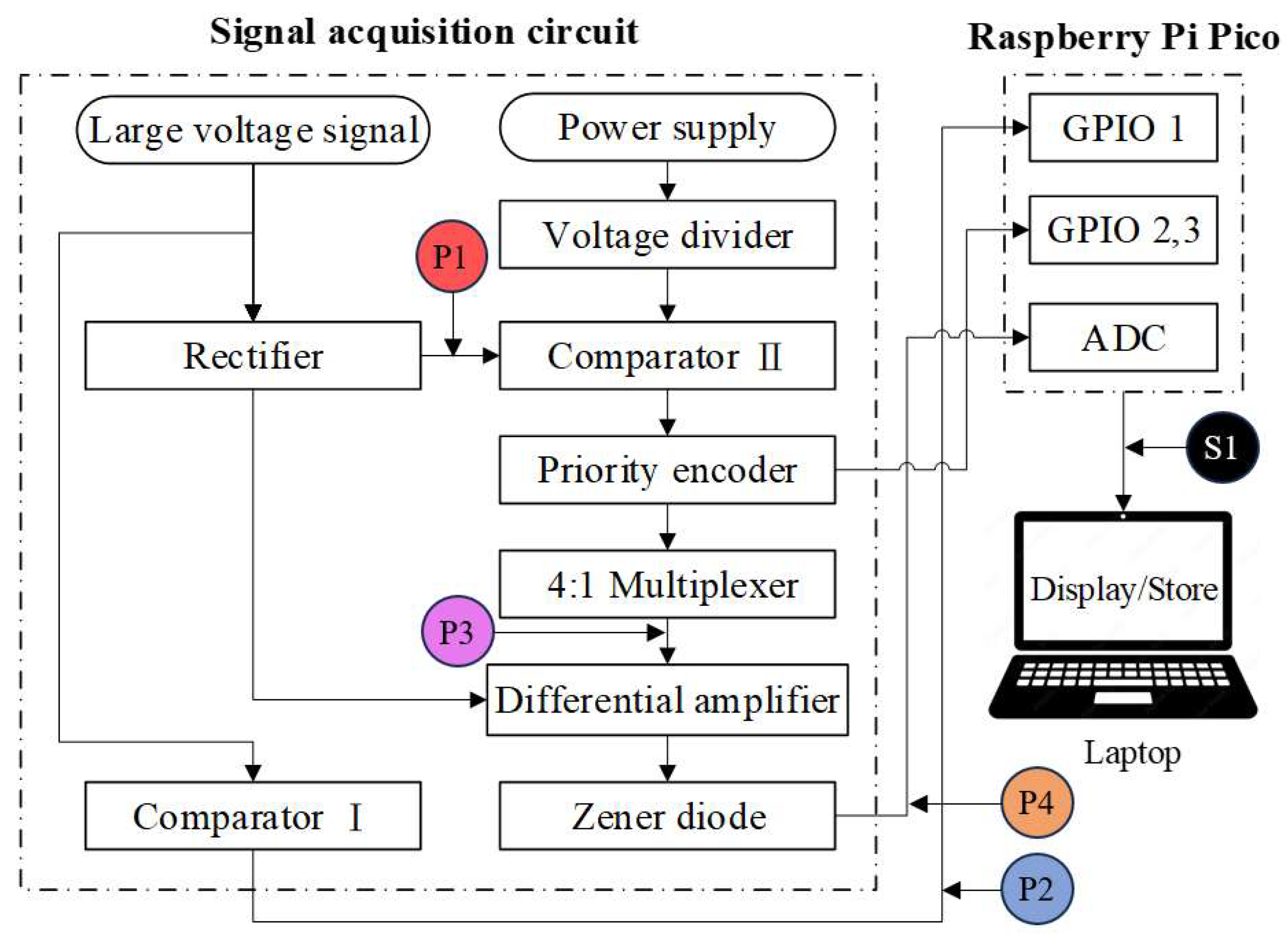

3. Implementation of Signal Acquisition System

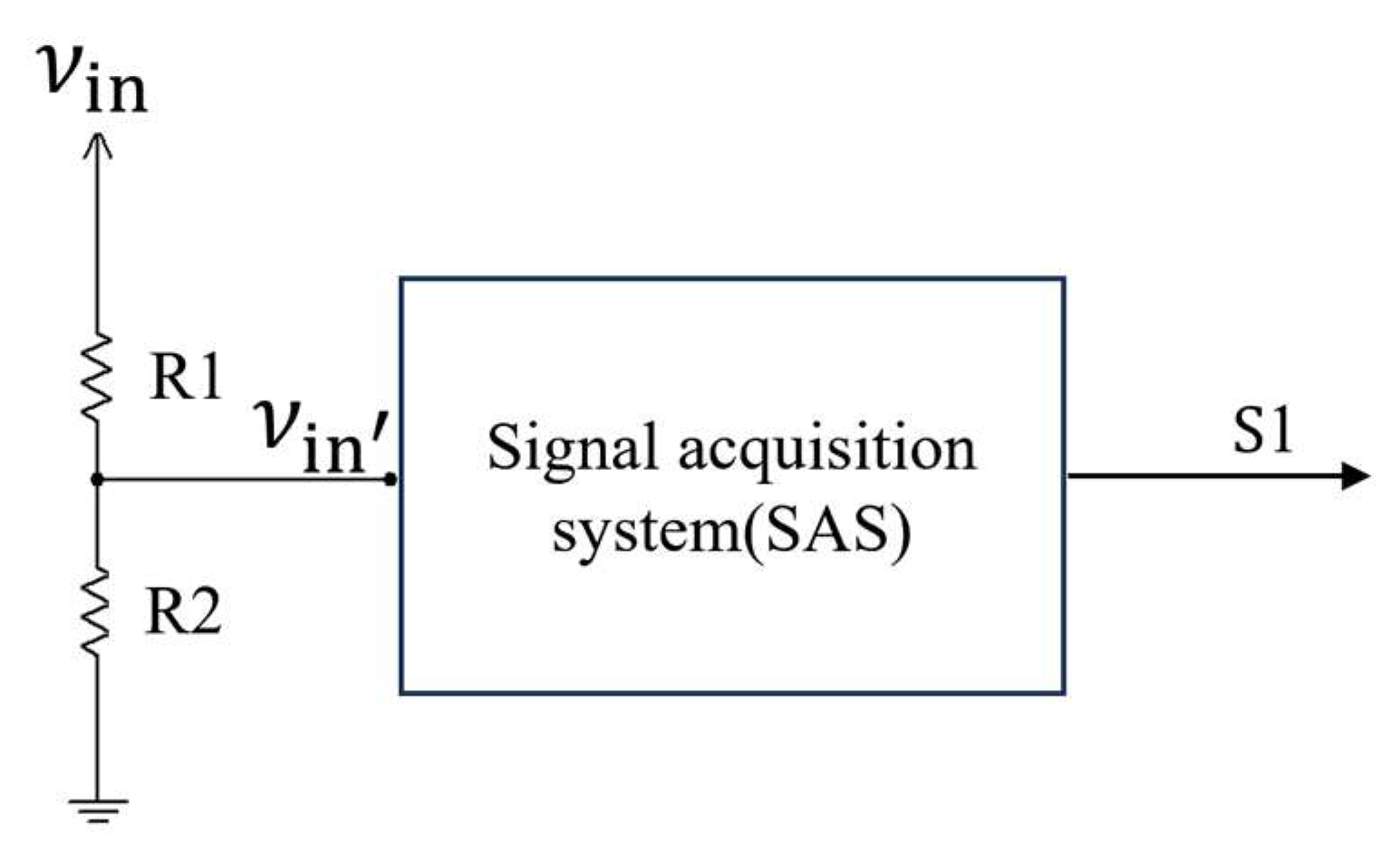

3.1. Signal Acquisition Circuit

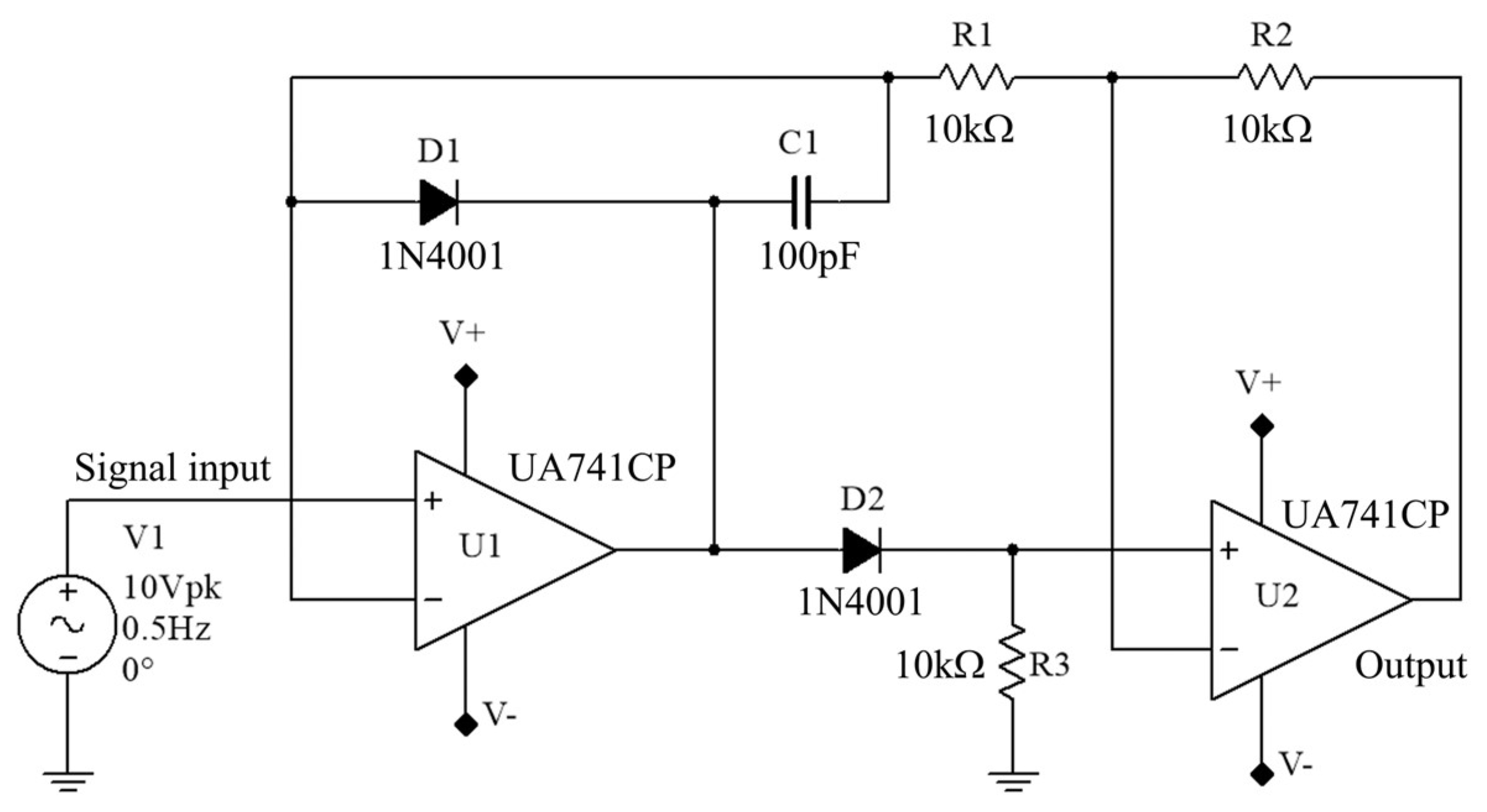

3.1.1. Precision Rectifier

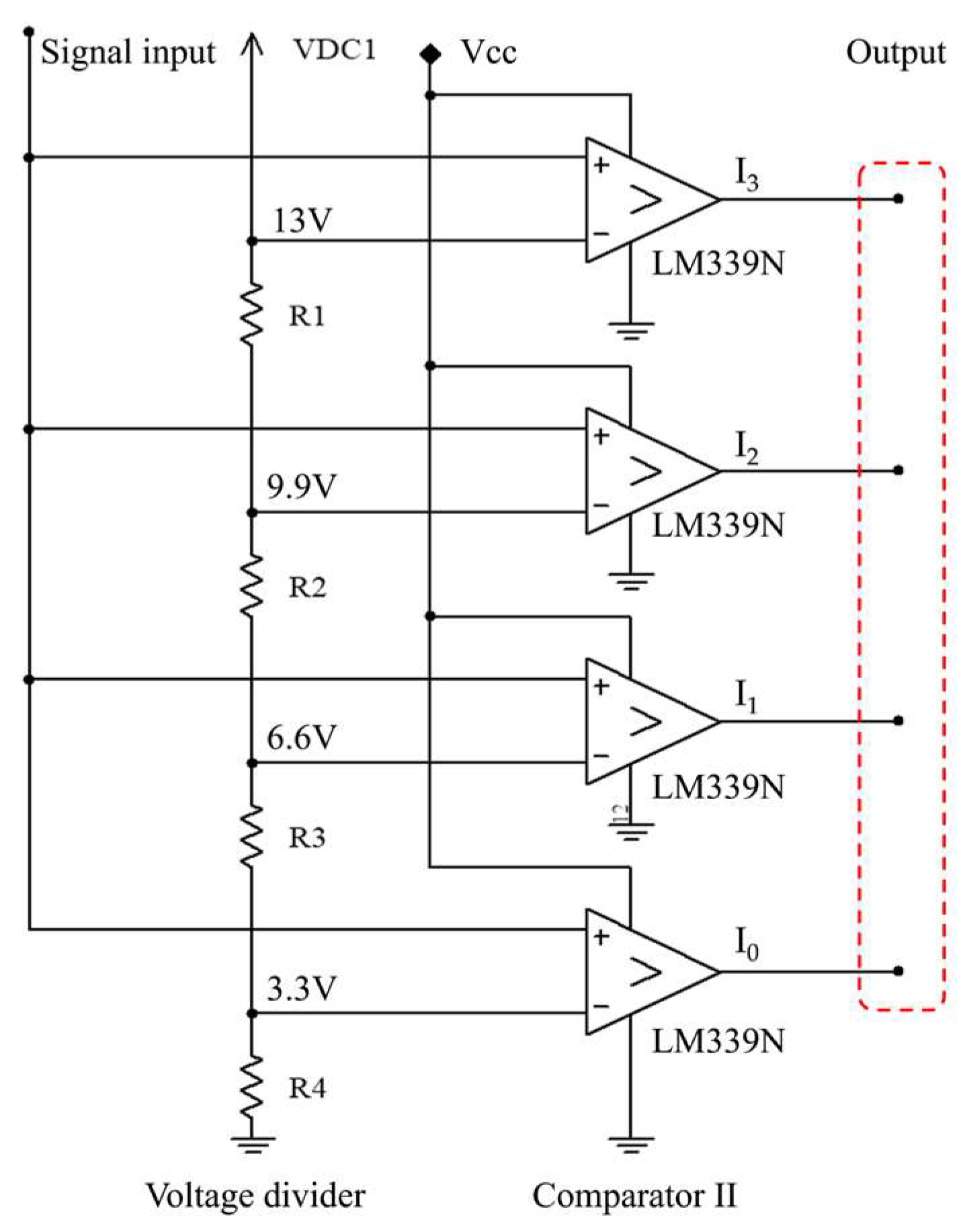

3.1.2. Voltage Divider

3.1.3. Comparators

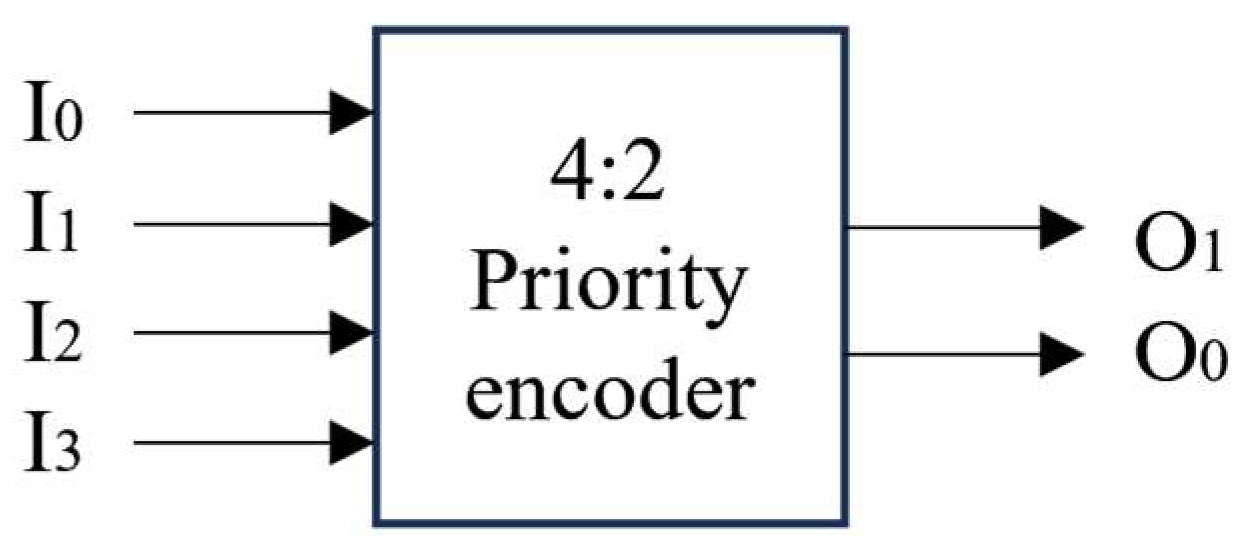

3.1.4. Priority Encoder

| Input | Output | ||||

| I3 | I2 | I1 | I0 | O1 | O0 |

| X | X | X | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| X | X | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| X | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

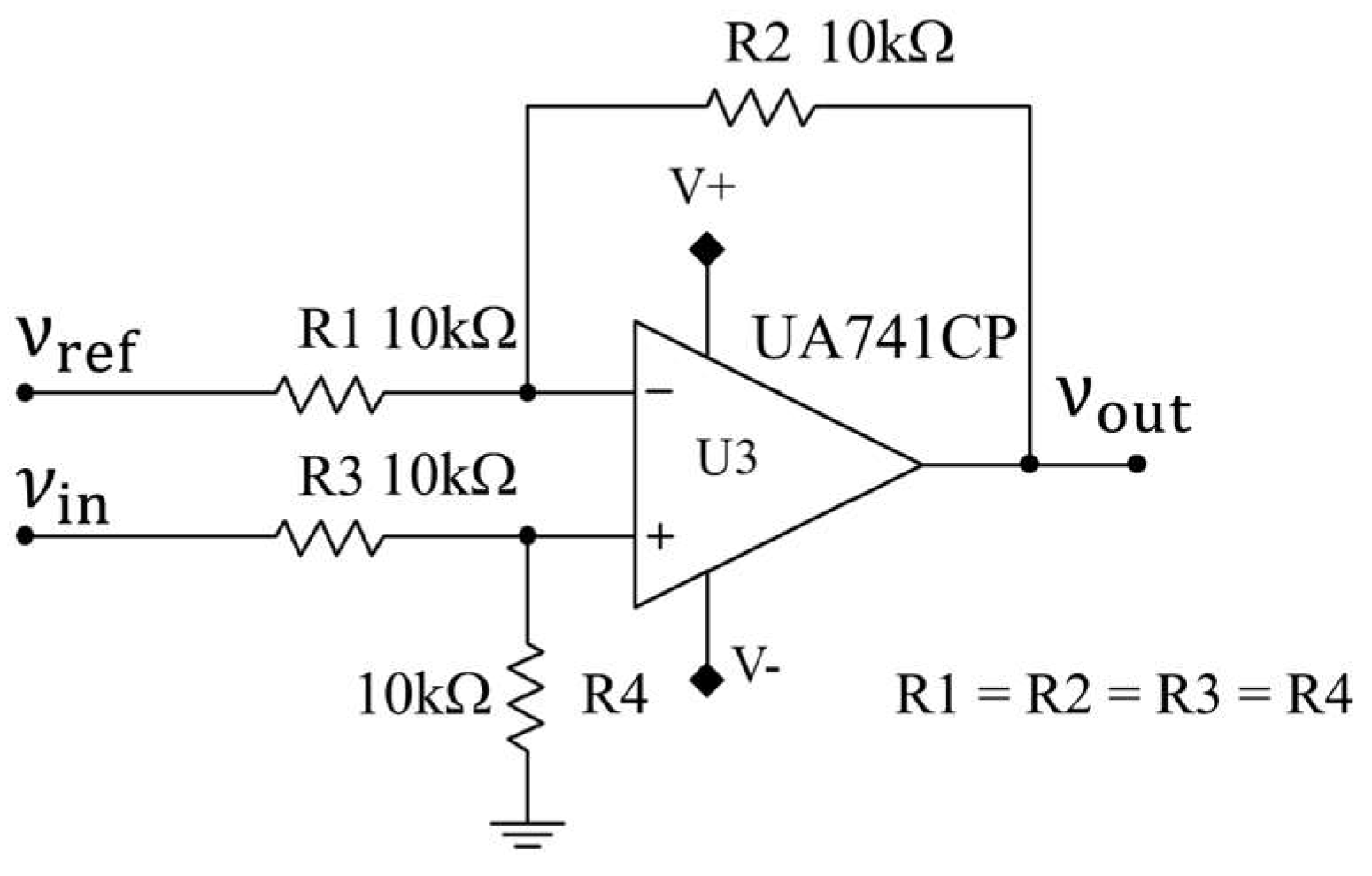

3.1.5. Multiplexor and Differential Amplifier

3.2. Raspberry Pi Pico

3.2.1. GPIO

| GPIO | GPIO | ||||

| 1 | Polarity | 2 | 3 | (V) | |

| 0 | Positive | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | Negative | 0 | 1 | 3.3 | |

| 1 | 0 | 6.6 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 9.9 | |||

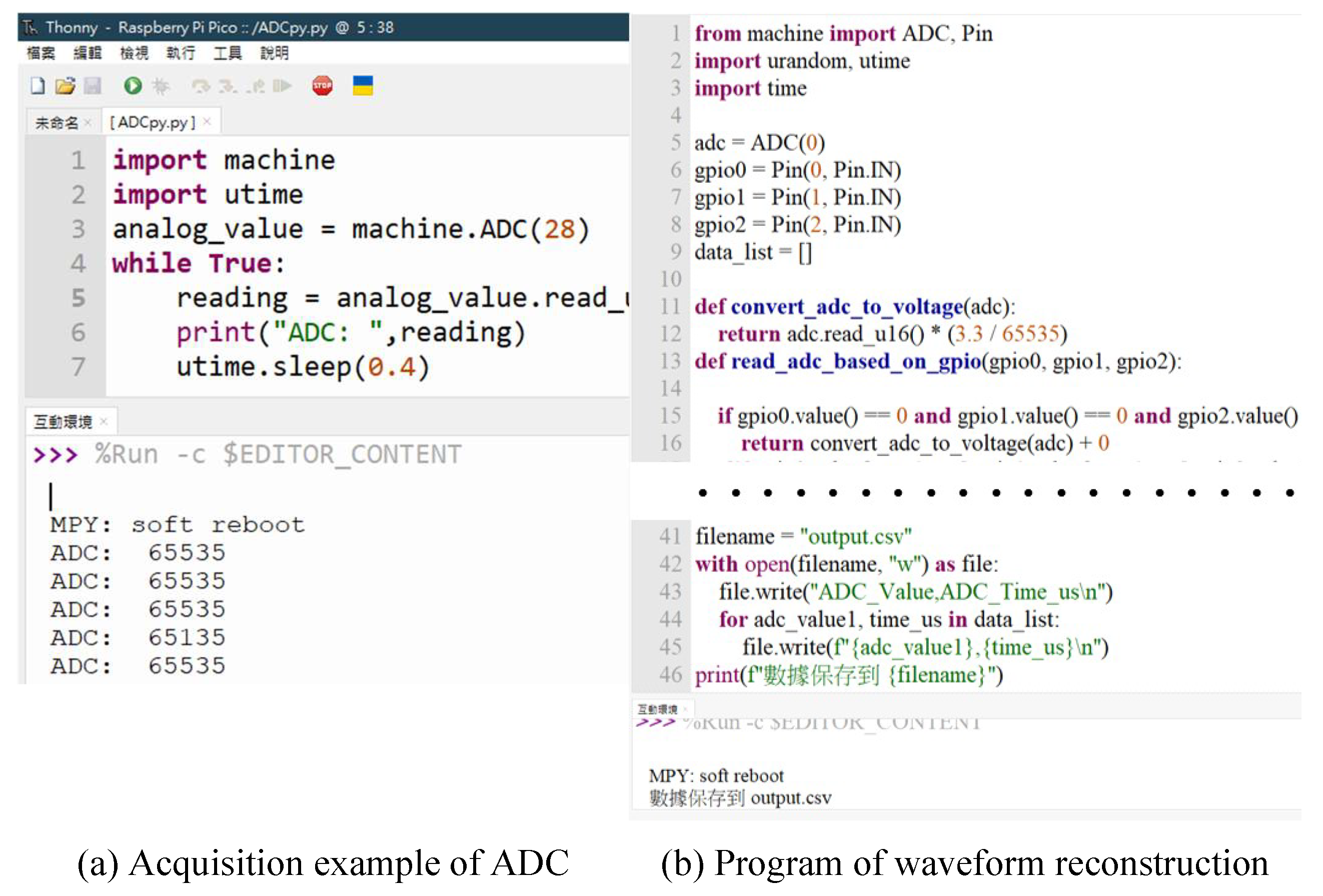

3.2.2. ADC

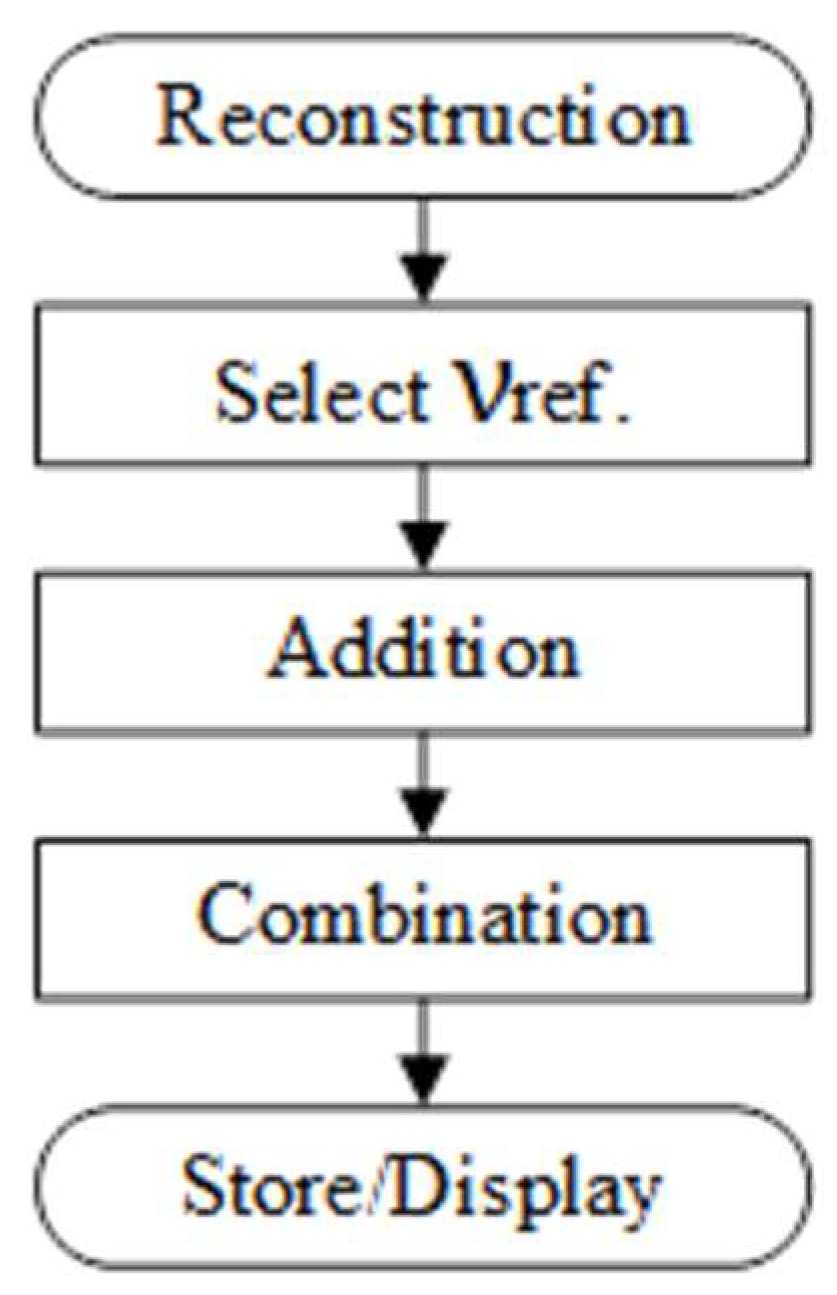

3.2.2. Waveform Reconstruction Program

4. Simulation Works

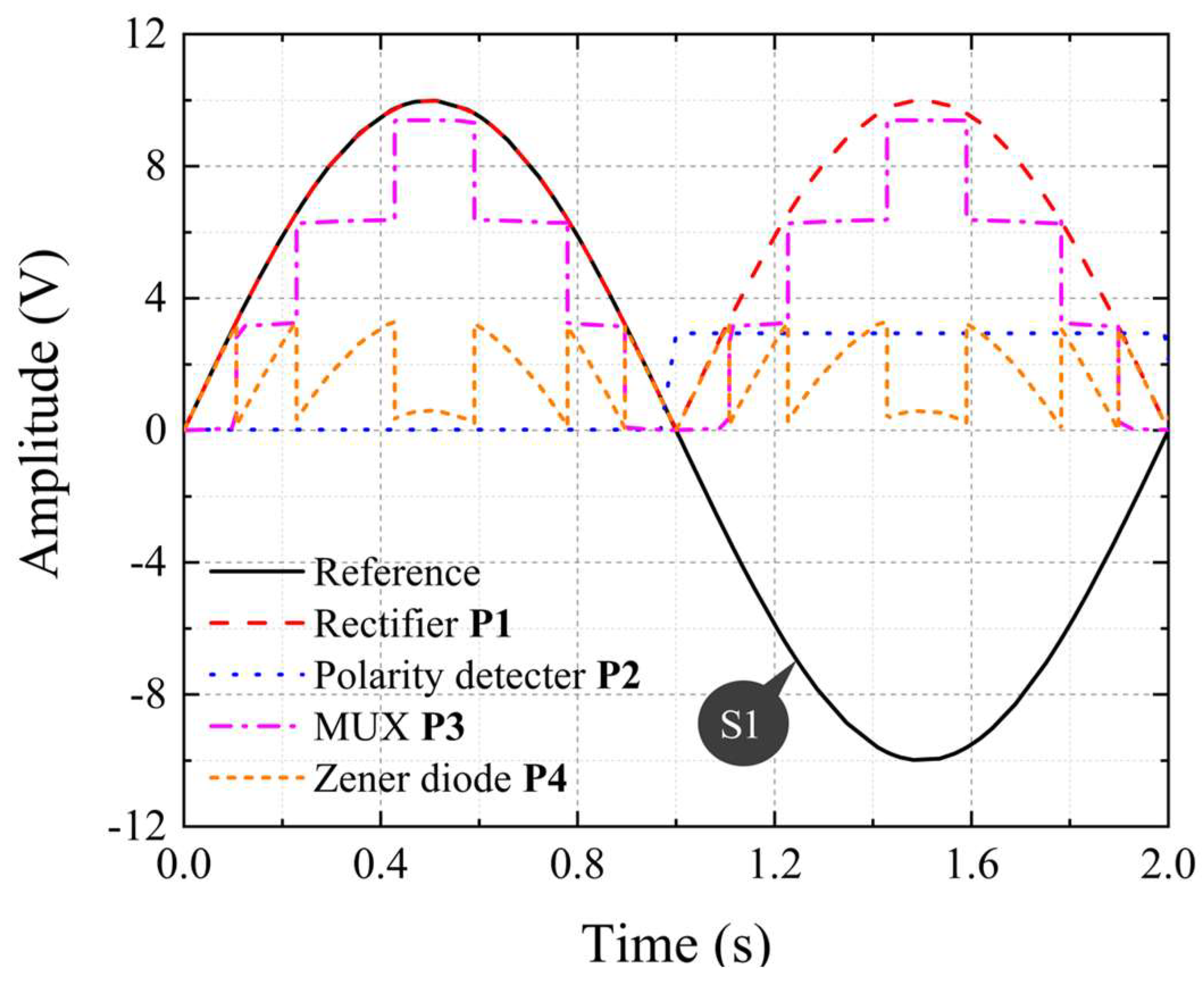

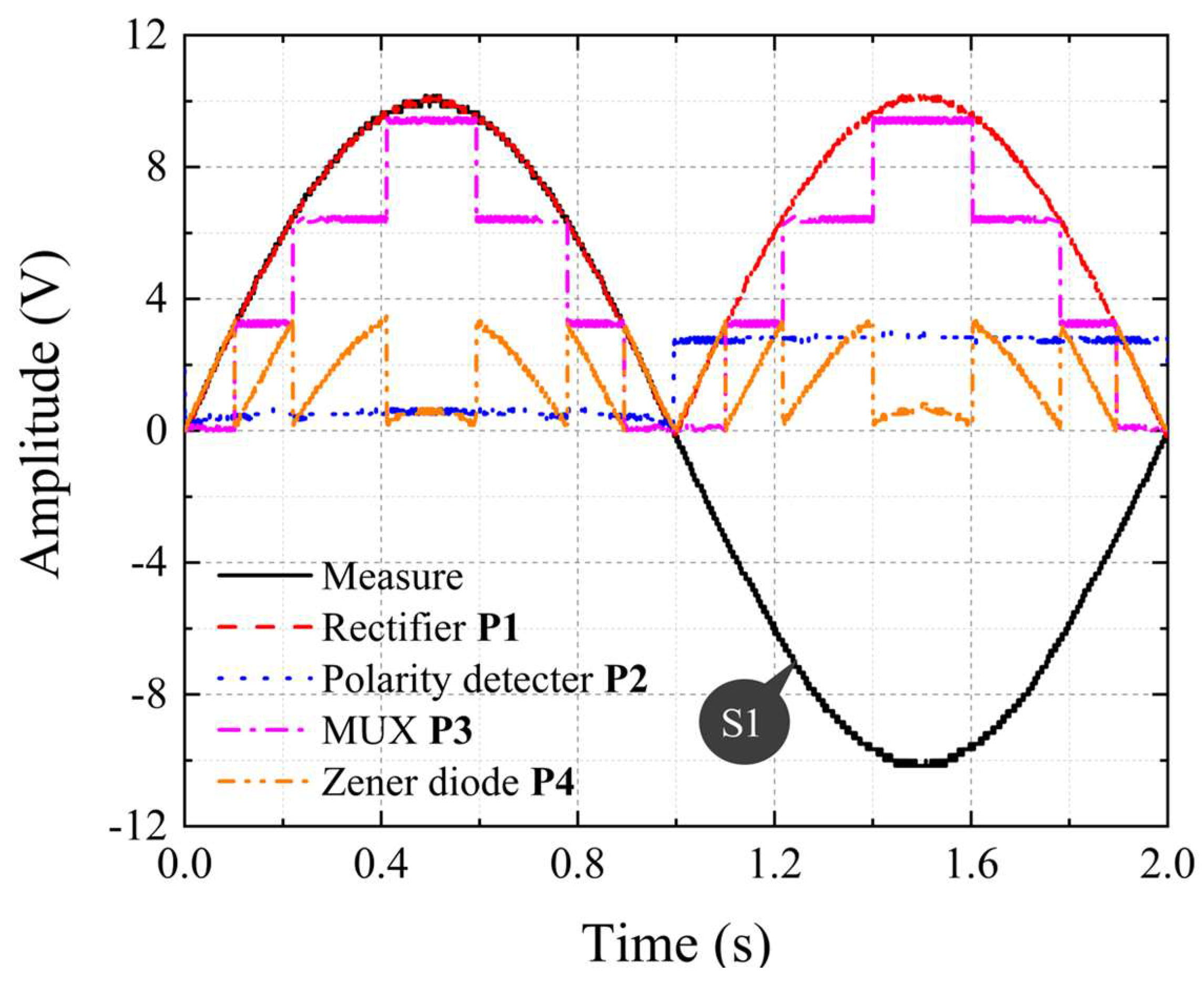

4.1. Simulation Waveforms and Signals

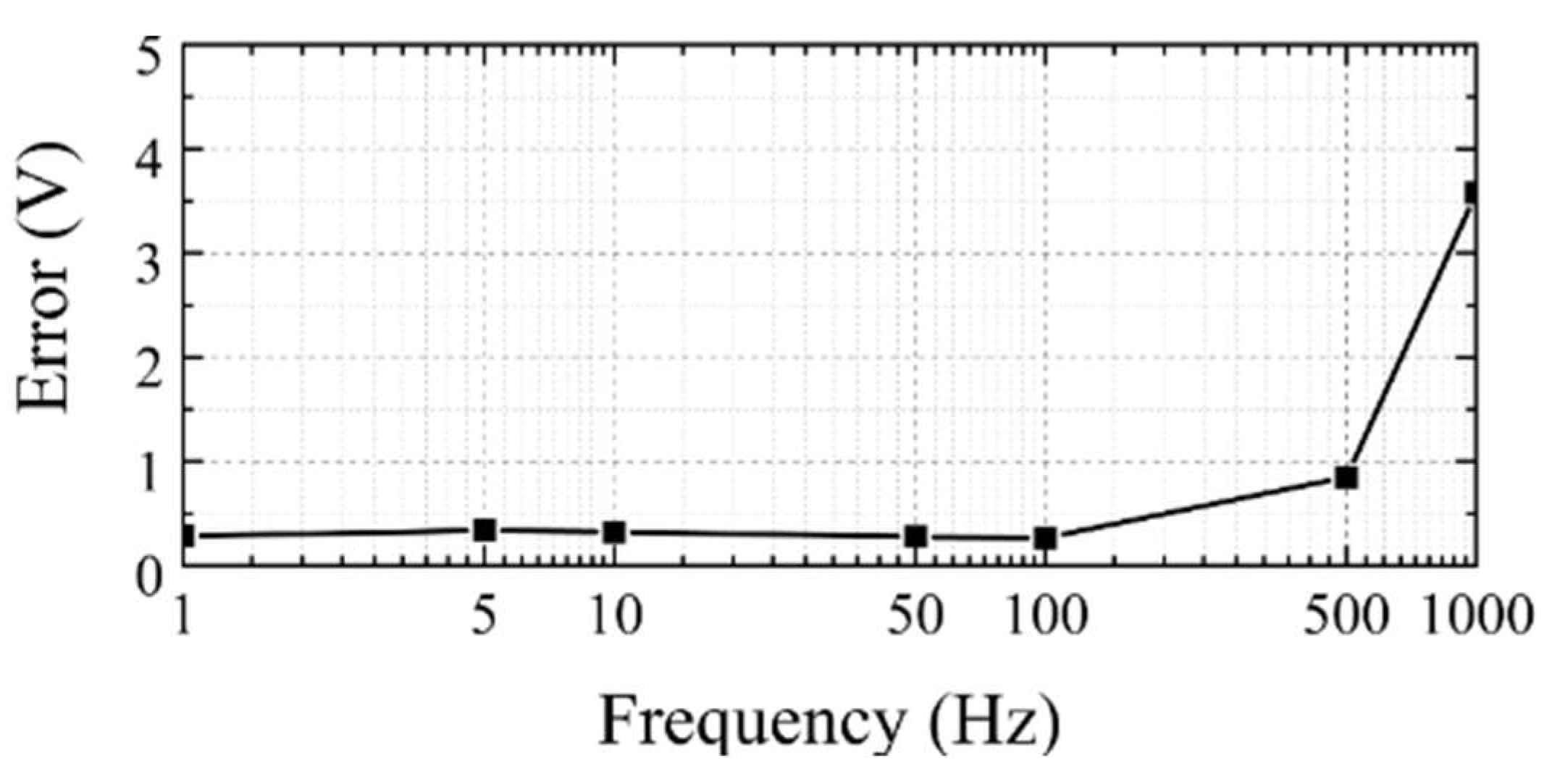

4.2. Simylation Waveform Affected by Frequency

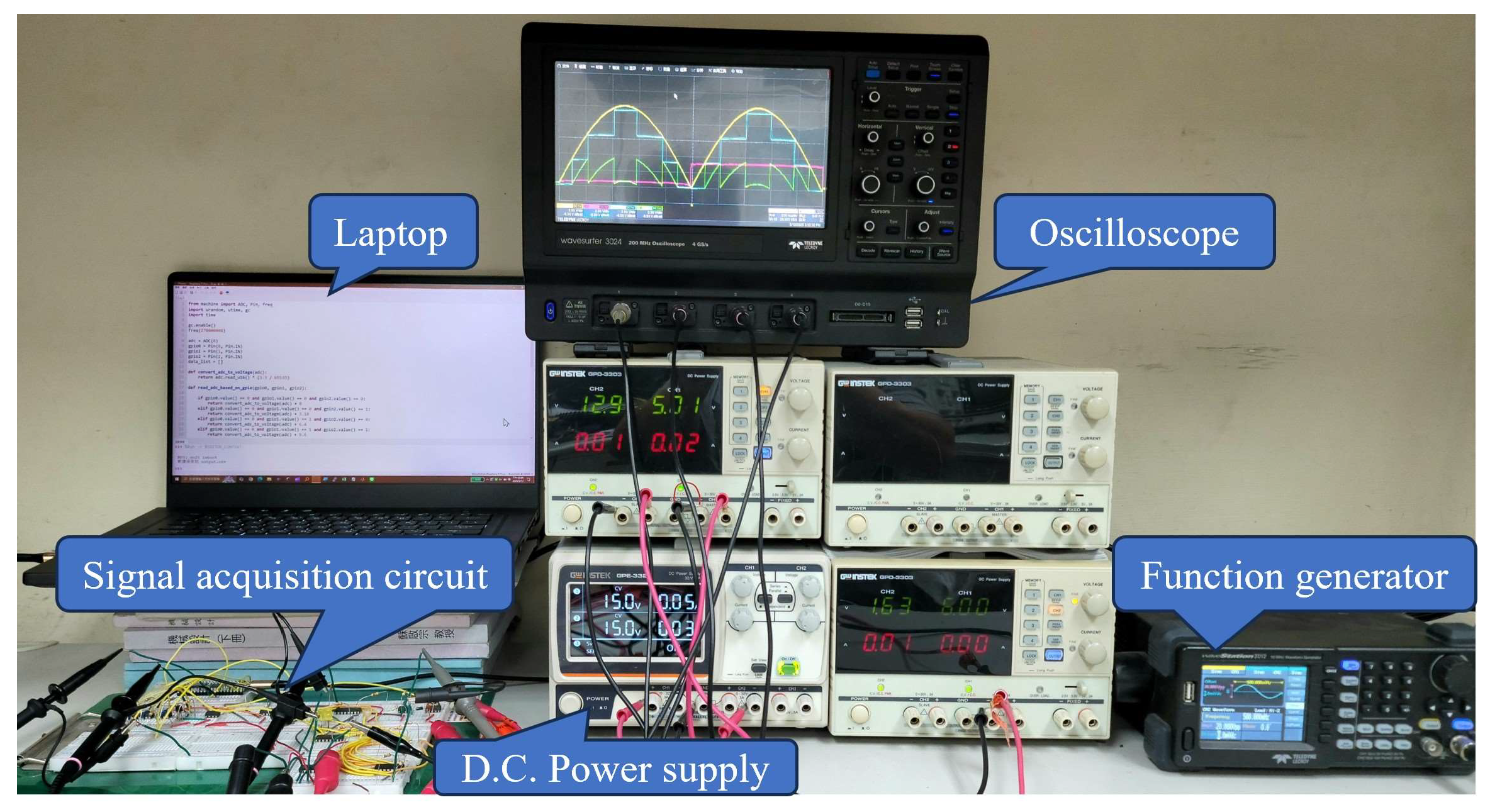

5. Experimental Verification

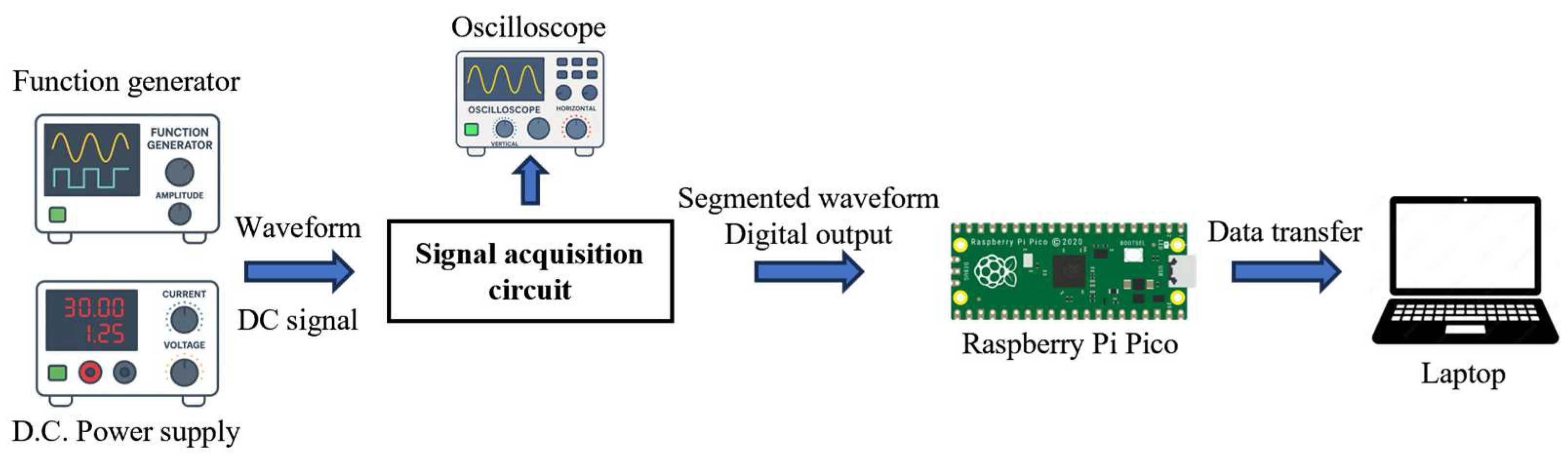

5.1. Experimental Setup

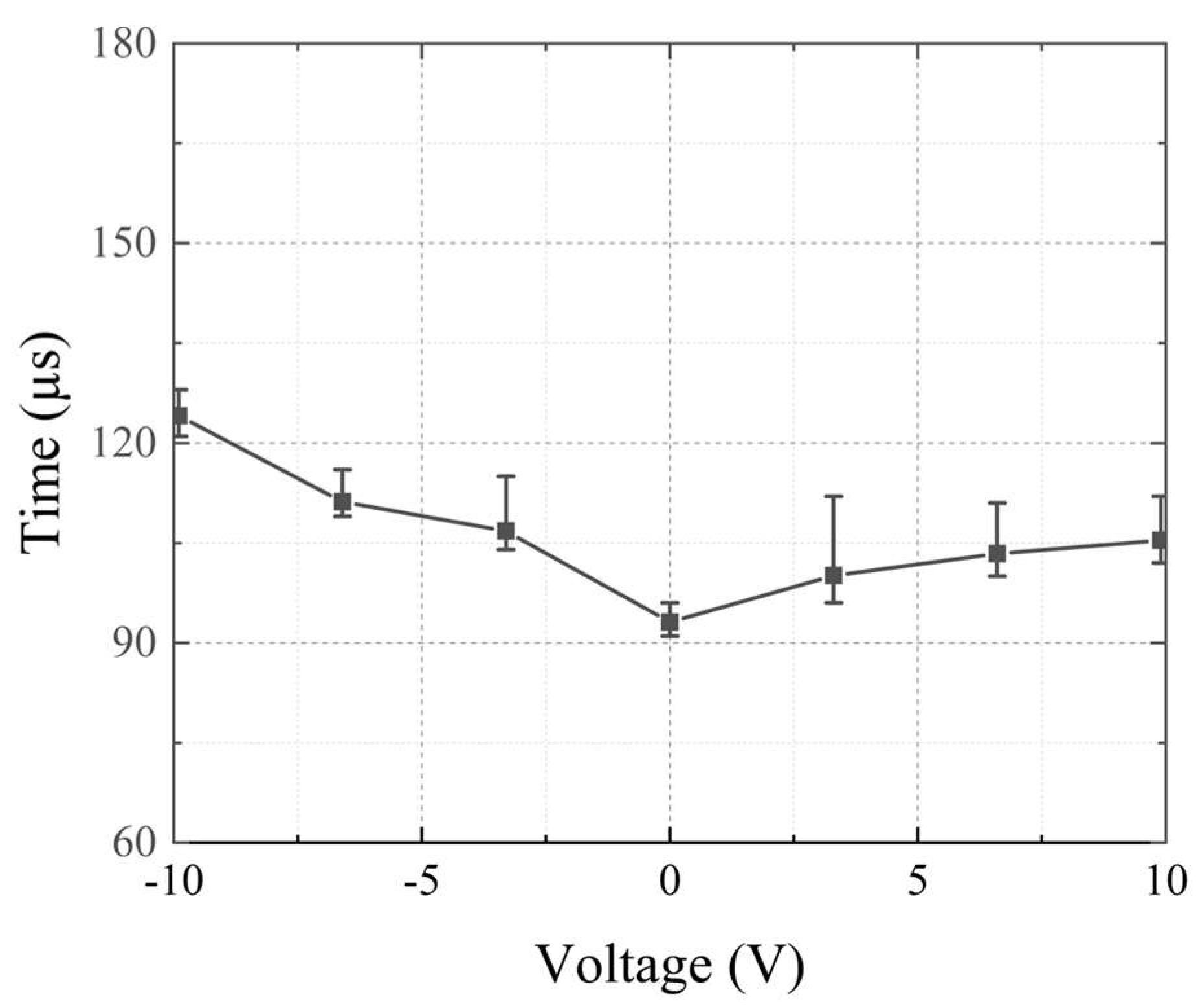

5.2. Measured Time Delay of ADC

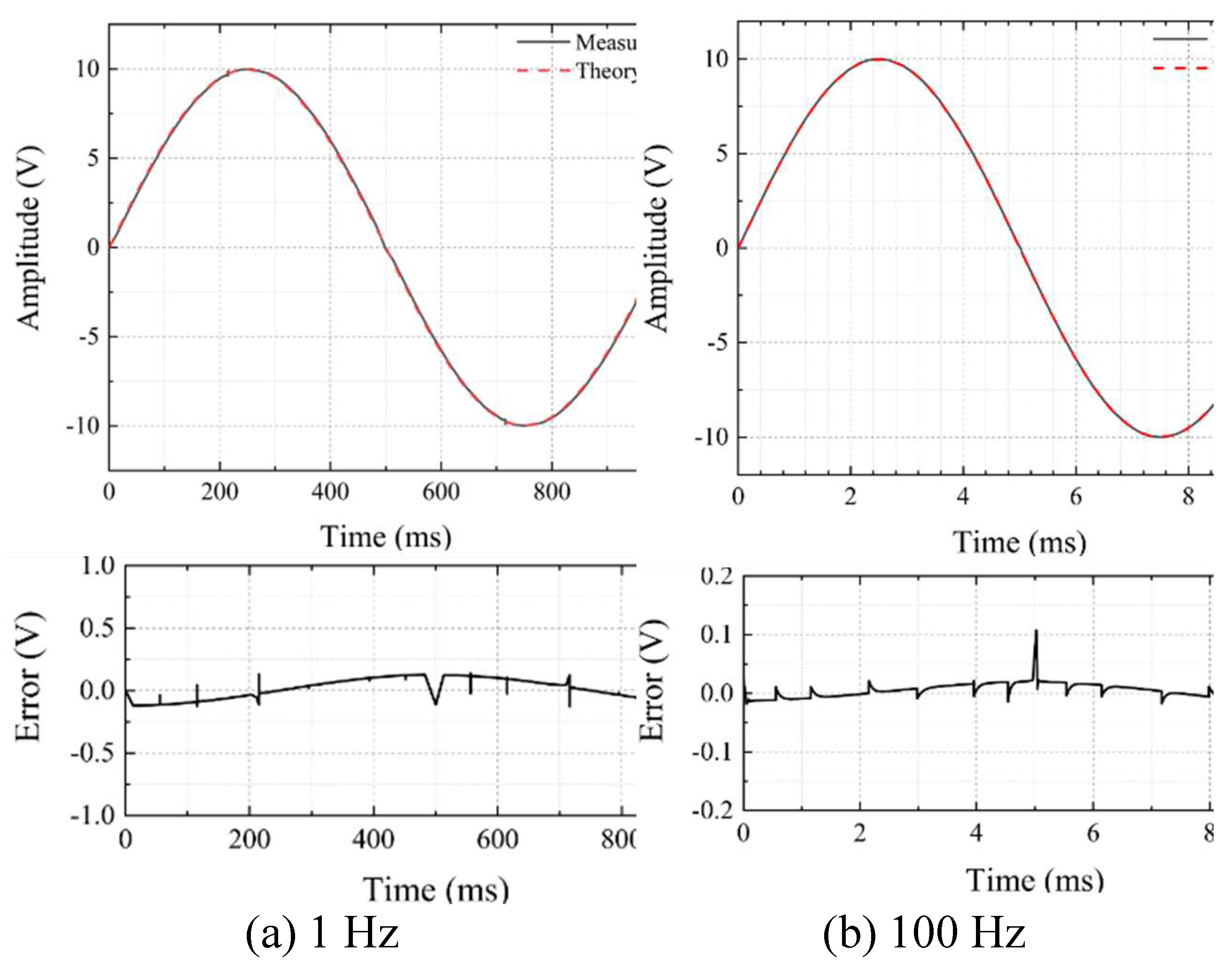

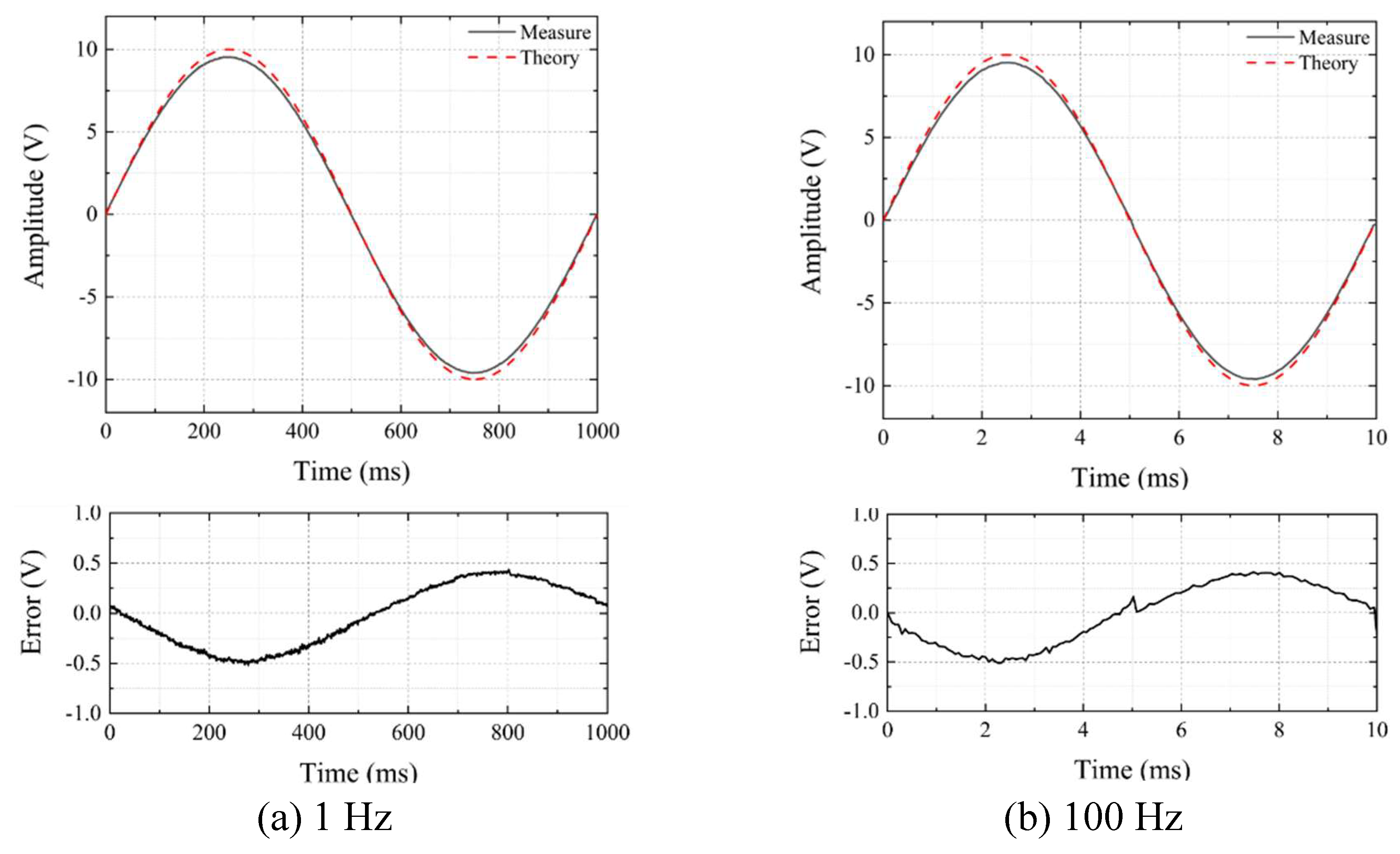

5.3. Measured Results of Sinusoidal Waveform

5.3.1. Reconstruction Waveform and Measured Signals

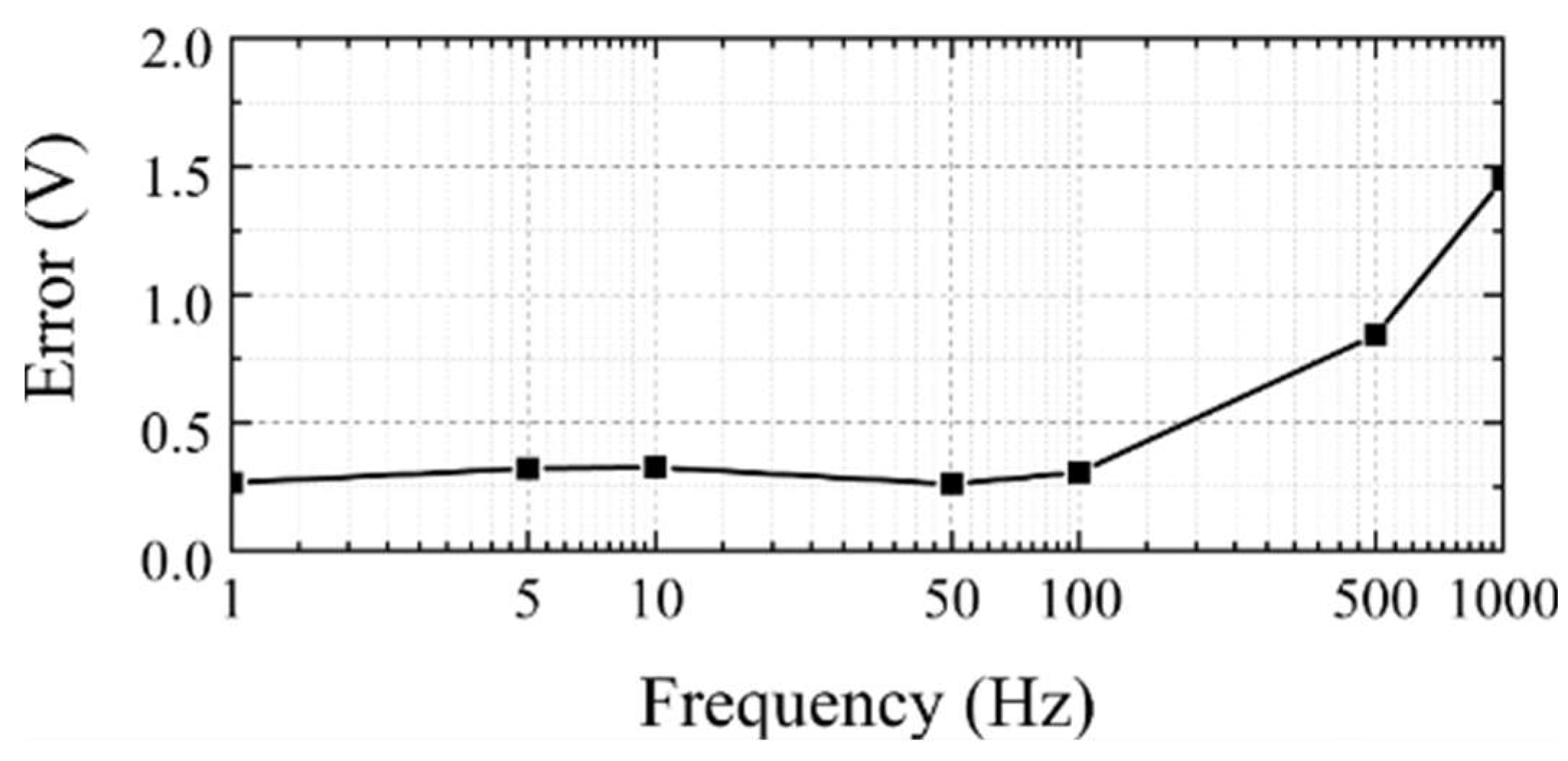

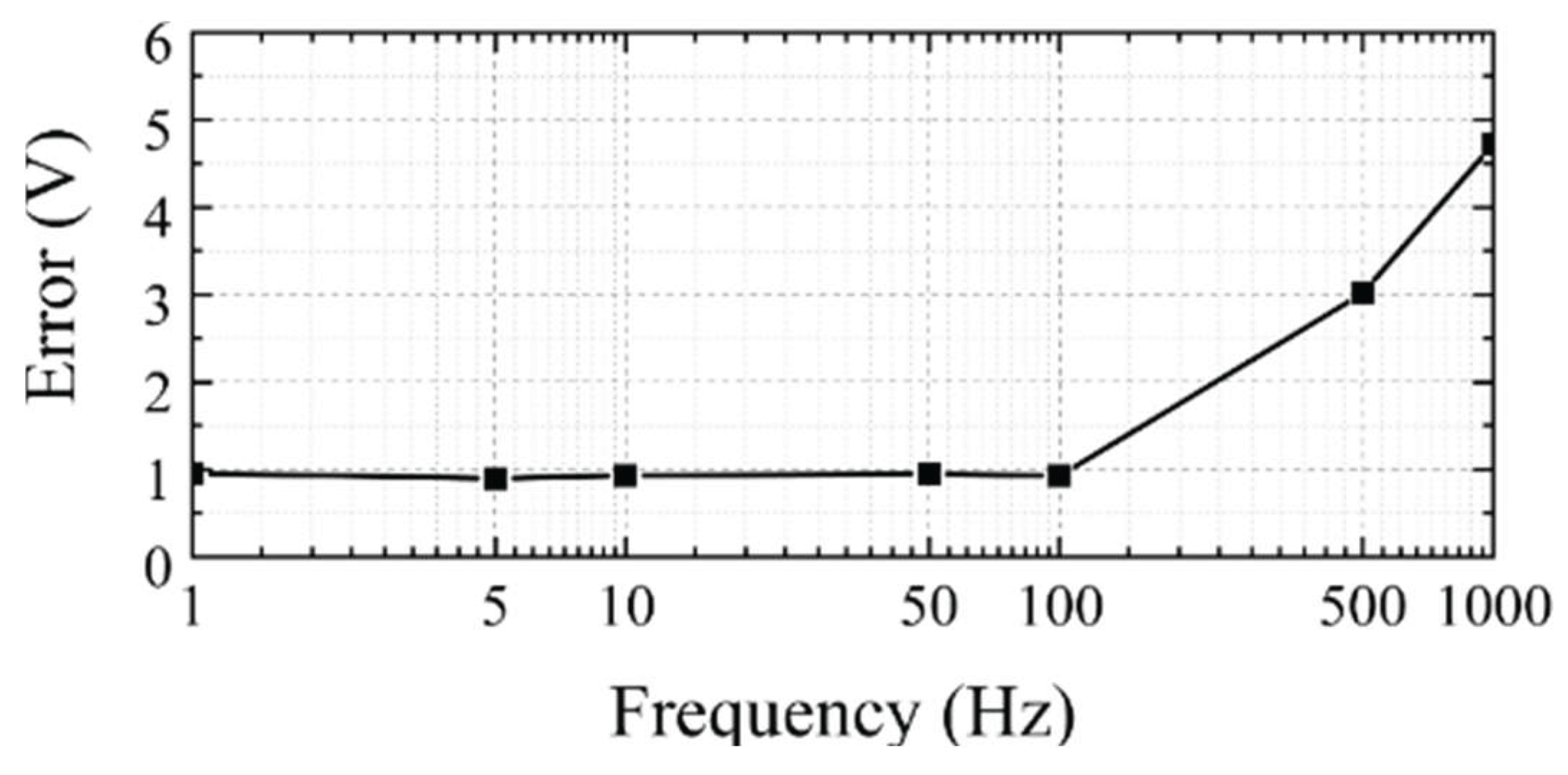

5.3.2. Reconstructed Waveform Affected by Frequency

5.4. Measured Results of Attenuated Sinusoidal Waveform

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The simulation results based on SPICE showed that a sinusoidal waveform with a large amplitude could be sensed and smoothly reconstructed. When the frequency was under 100 Hz, the PV error was with the value of 0.25 V.

- (2)

- The DC voltages were applied to examine the time delay of voltage acquisition. When the voltage was 0, the average time delay was 93.1 μs; when the voltage was −9.9 V, the SAS appeared the largest time delay of 125 μs. That is, the sampling rate could reach 8,000 samples per second.

- (3)

- The experimental results based on SAS showed that a sinusoidal waveform with a large amplitude could be sensed and smoothly reconstructed. When the frequency was under 100 Hz, the PV error fluctuated within 0.27 ~ 0.34 V.

- (4)

- The experiments for the attenuated waveform based on the voltage divider were conducted. Although the waveforms could be smoothly reconstructed, the PV error ranging −0.5 ~ 0.4 V showed much worse acquisition accuracy than that without voltage attenuation.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Alternating current |

| ADC | Analog-to-digital converter |

| DC | Direct current |

| GPIO | General purpose input/output |

| I4.0 | Industry 4.0 |

| IoT | Internet of things |

| MUX | Multiplexor |

| OPA | Operational amplifier |

| SAS | Signal acquisition system |

| SPICE | Simulation program with integrated circuit emphasis |

References

- Qin, J.; Liu, Y.; Grosvenor, R. A Categorical Framework of Manufacturing for Industry 4.0 and Beyond. Procedia CIRP 2016, 52, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.M.; Saleh, M.; Al-Ahmari, A.M.; Anwar, S. The Impact of Industry 4.0 Technologies on Manufacturing Strategies: Proposition of Technology-Integrated Selection. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 21574–21583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Bagheri, B.; Kao, H.-A. A Cyber-Physical Systems Architecture for Industry 4.0-Based Manufacturing Systems. Manufacturing Letters 2015, 3, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Lo, C.-T. Smart Manufacturing Powered by Recent Technological Advancements: A Review. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2022, 64, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoom, T.; Ramzan, N.; Ahmed, S.; Ur-Rehman, M. Advances in Sensor Technologies in the Era of Smart Factory and Industry 4.0. Sensors 2020, 20, 6783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kler, R.; Ashish; Nimmagadda, P.; Navarajan, J.; Chauhan, D.; Babu, G.R. Recognition and Implementation of the Smart Manufacturing Systems in Industrial Sectors for Evolving Industry 4.0. Measurement: Sensors 2024, 31, 100987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanane, B.; Bentaha, M.-L.; Dafflon, B.; Moalla, N. Bridging the Gap between Industry 4.0 and Manufacturing SMEs: A Framework for an End-to-End Total Manufacturing Quality 4.0’s Implementation and Adoption. Journal of Industrial Information Integration 2025, 45, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskó, S.; Ruppert, T. The Future of Manufacturing and Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://docs.arduino.cc/hardware/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Available online: https://www.espressif.com/en/products/socs (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Available online: https://www.raspberrypi.com/products/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Schlobohm, J.; Pösch, A.; Reithmeier, E. A Raspberry Pi Based Portable Endoscopic 3D Measurement System. Electronics 2016, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrož, M. Raspberry Pi as a Low-Cost Data Acquisition System for Human Powered Vehicles. Measurement 2017, 100, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Zuriaga, A.M.; Llopis-Castelló, D.; Just-Martínez, V.; Fonseca-Cabrera, A.S.; Alonso-Troyano, C.; García, A. Implementation of a Low-Cost Data Acquisition System on an E-Scooter for Micromobility Research. Sensors 2022, 22, 8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukič, P. Štumberger, G. Intra-Minute Cloud Passing Forecasting Based on a Low Cost IoT Sensor—A Solution for Smoothing the Output Power of PV Power Plants. Sensors 2017, 17, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.I.S.; Dupont, I.M.; Carvalho, P.C.M.; Jucá, S.C.S. IoT Embedded Linux System Based on Raspberry Pi Applied to Real-Time Cloud Monitoring of a Decentralized Photovoltaic Plant. Measurement 2018, 114, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, I.; Portalo, J.M.; Calderón, A.J. Configurable IoT Open-Source Hardware and Software I-V Curve Tracer for Photovoltaic Generators. Sensors 2021, 21, 7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adigüzel, E.; Gürkan, K.; Ersoy, A. Design and Development of Data Acquisition System (DAS) for Panel Characterization in PV Energy Systems. Measurement 2023, 221, 113425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-S.; Wang, H.-W.; Liu, S.-H. An Integrated Accelerometer for Dynamic Motion Systems. Measurement 2018, 125, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, M.T.; Kim, J.-M.; Kim, C.H. Deep Learning-Based Bearing Fault Diagnosis Method for Embedded Systems. Sensors 2020, 20, 6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Ocampo, C.R.; Mera, J.M.; Cano-Moreno, J.D.; Garcia-Bernardo, J.L. Low-Cost, High-Frequency, Data Acquisition System for Condition Monitoring of Rotating Machinery through Vibration Analysis-Case Study. Sensors 2020, 20, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglari, A.; Tang, W. A Review of Embedded Machine Learning Based on Hardware, Application, and Sensing Scheme. Sensors 2023, 23, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.-Q.; Doan, H.-P.; Vu, V.Q.; Vu, L.T. Machine Learning and IoT-Based Approach for Tool Condition Monitoring: A Review and Future Prospects. Measurement 2023, 207, 112351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodrič, M.; Korbar, J.; Pogačar, M.; Čepon, G. Development of a Resource-Efficient Real-Time Vibration-Based Tool Condition Monitoring System Using PVDF Accelerometers. Measurement 2025, 251, 117183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandarkar, V.V.; Das, B.; Tandon, P. Real-Time Remote Monitoring and Defect Detection in Smart Additive Manufacturing for Reduced Material Wastage. Measurement 2025, 252, 117362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.-Y.; Sahoo, N.; Lin, H.-W.; Chang, Y.-H. Predictive Maintenance with Sensor Data Analytics on a Raspberry Pi-Based Experimental Platform. Sensors 2019, 19, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunicki, M.; Borucki, S.; Zmarzły, D.; Frymus, J. Data Acquisition System for On-Line Temperature Monitoring in Power Transformers. Measurement 2020, 161, 107909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiani, E.; Wang, L.-Y.; Liu, J.-C.; Huang, C.-K.; Wei, S.-J.; Yang, C.-T. An Intelligent Thermal Compensation System Using Edge Computing for Machine Tools. Sensors 2024, 24, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pei, H.; Kochan, O.; Wang, C.; Kochan, R.; Ivanyshyn, A. Method for Correcting Error Due to Self-Heating of Resistance Temperature Detectors Suitable for Metrology in Industry 4.0. Sensors 2024, 24, 7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iafolla, L.; Santoli, F.; Carluccio, R.; Chiappini, S.; Fiorenza, E.; Lefevre, C.; Loffredo, P.; Lucente, M.; Morbidini, A.; Pignatelli, A.; Chiappini, M. Temperature Compensation in High Accuracy Accelerometers Using Multi-Sensor and Machine Learning Methods. Measurement 2024, 226, 114090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Arellano, F.; López-Bonilla, O.R.; García-Guerrero, E.E.; Olguín-Tiznado, J.E.; Inzunza-González, E.; López-Mancilla, D.; Tlelo-Cuautle, E. Development of a Portable, Reliable and Low-Cost Electrical Impedance Tomography System Using an Embedded System. Electronics 2021, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.-H.; Lai, M.-Y.; Liu, Y.-T. Implementation of DDS Cloud Platform for Real-Time Data Acquisition of Sensors for a Legacy Machine. Electronics 2022, 11, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donca, I.-C.; Stan, O.P.; Misaros, M.; Stan, A.; Miclea, L. Comprehensive Security for IoT Devices with Kubernetes and Raspberry Pi Cluster. Electronics 2024, 13, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.raspberrypi.com/products/raspberry-pi-pico/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Thothadri, M. An Analysis on Clock Speeds in Raspberry Pi Pico and Arduino Uno Microcontrollers. American Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 2021, 6, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pete Wilson, P.E. High-Voltage Signal Conditioning for Low-Voltage ADCs. Application Report, SBOA097, Texas Instruments 2004.

- Aghenta, L.O.; Iqbal, M.T. Low-Cost, Open Source IoT-Based SCADA System Design Using Thinger.IO and ESP32 Thing. Electronics 2019, 8, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauzan, M.; Yanti, I. Utilization of ADC Pin on Arduino Nano to Measure Voltage of a Battery. TEKNOKOM: Jurnal Teknologi dan Rekayasa Sistem Komputer 2021, 4, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patangia, H.C.; Gregory, D. High Voltage Signal Processing Using a Small Signal Approach. IEEE International Symposium on Signal Processing and Information Technology 2007, 1088-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-X.; Chang, K.-M.; Liu, Y.-T. Signal Acquisition Device for Large Voltage Waveform Using Low-cost Raspberry Pi Pico W. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Mechatronics Technology (ICMT2024), Kanazawa, Japan, 11-19, 2024.

- Available online: https://www.eet-china.com/mp/a71275.html (accessed on 16 May 2025).

| Microcontroller | Clock speed(MHz) | SRAM (Kbyte) | Flash memory (Byte) | ADC(bit) | ADC voltage range (V) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pico | RP2040 | 133 | 264 | 2M | 12 | 0~3.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).