Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

A. Material

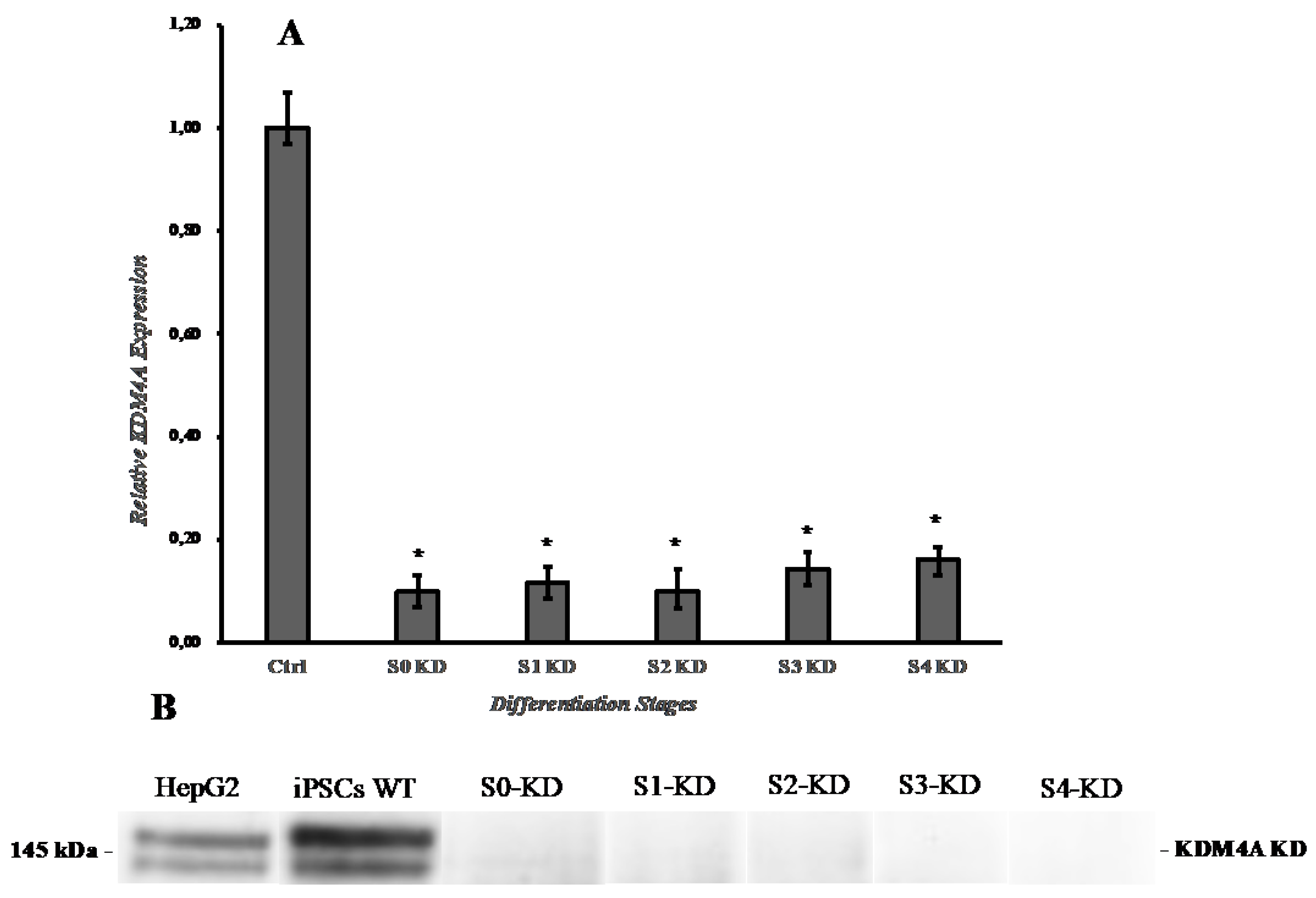

B. Knockdown of KDM4A in iPSCs with shRNA:

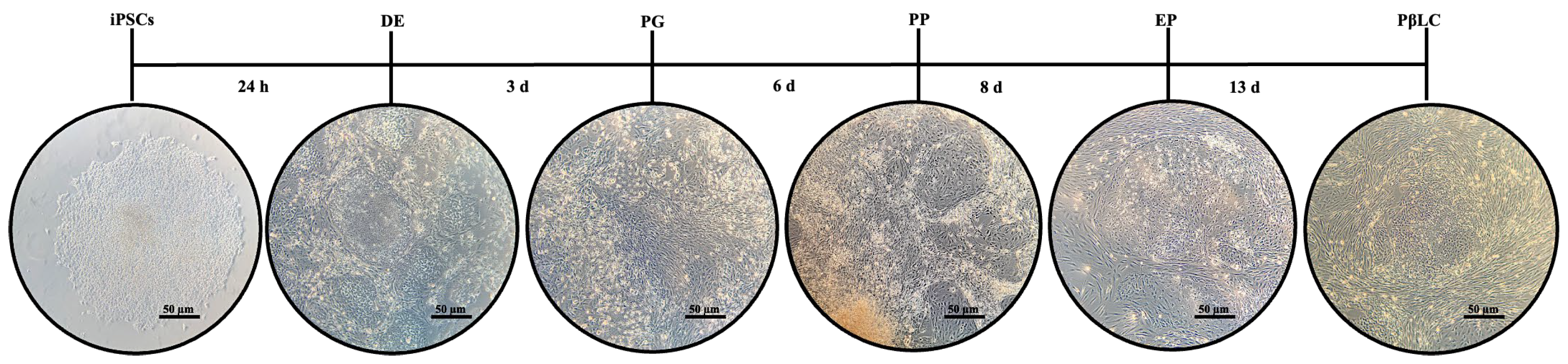

C. iPSCs Differentiation

D. RT-PCR and qPCR Analysis of Gene Expression

E. Immunofluorescence

F. Western Blot

G. Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS)

H. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of shKDM4A on iPSCs self-Renewal and Growth Rate

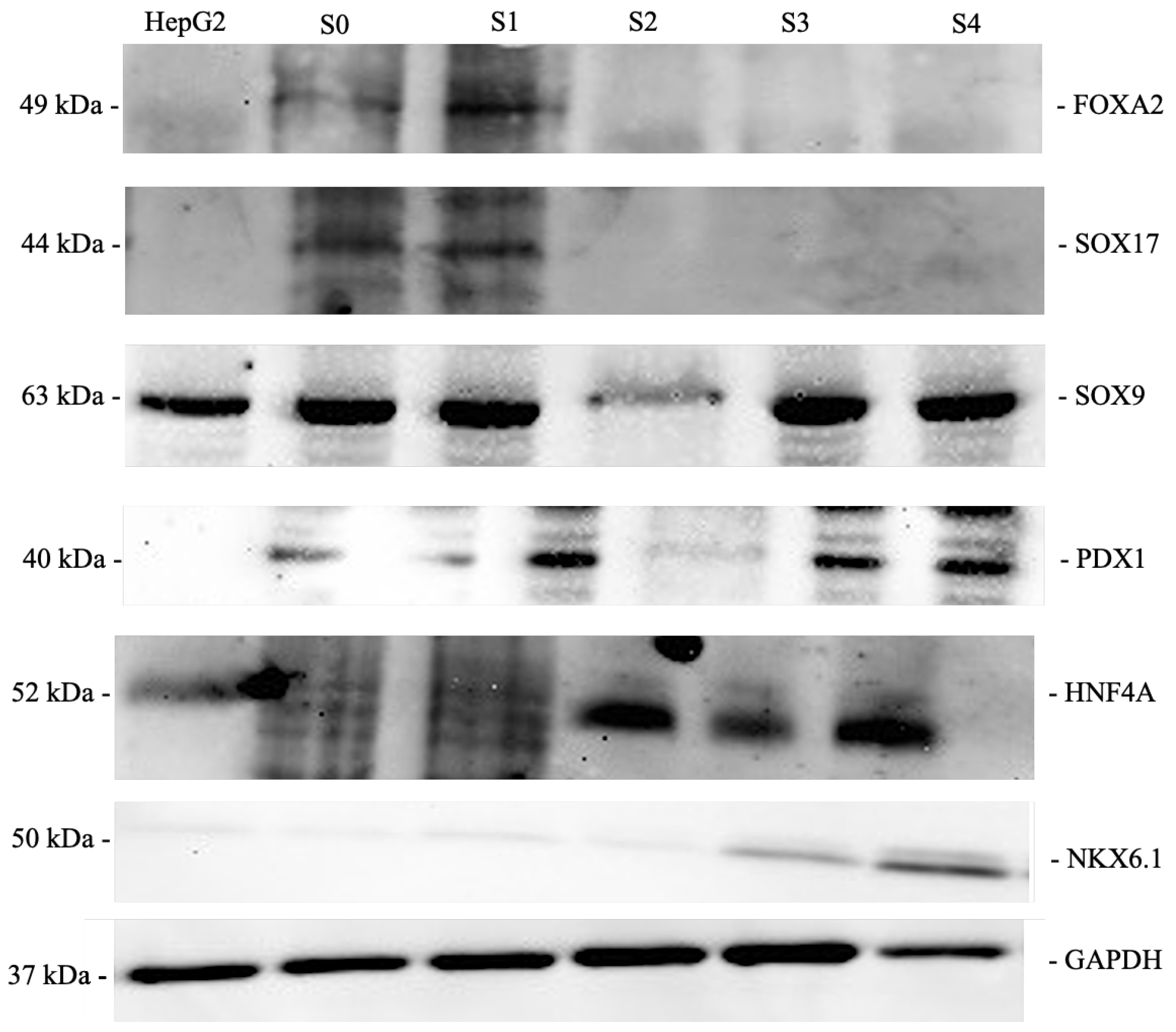

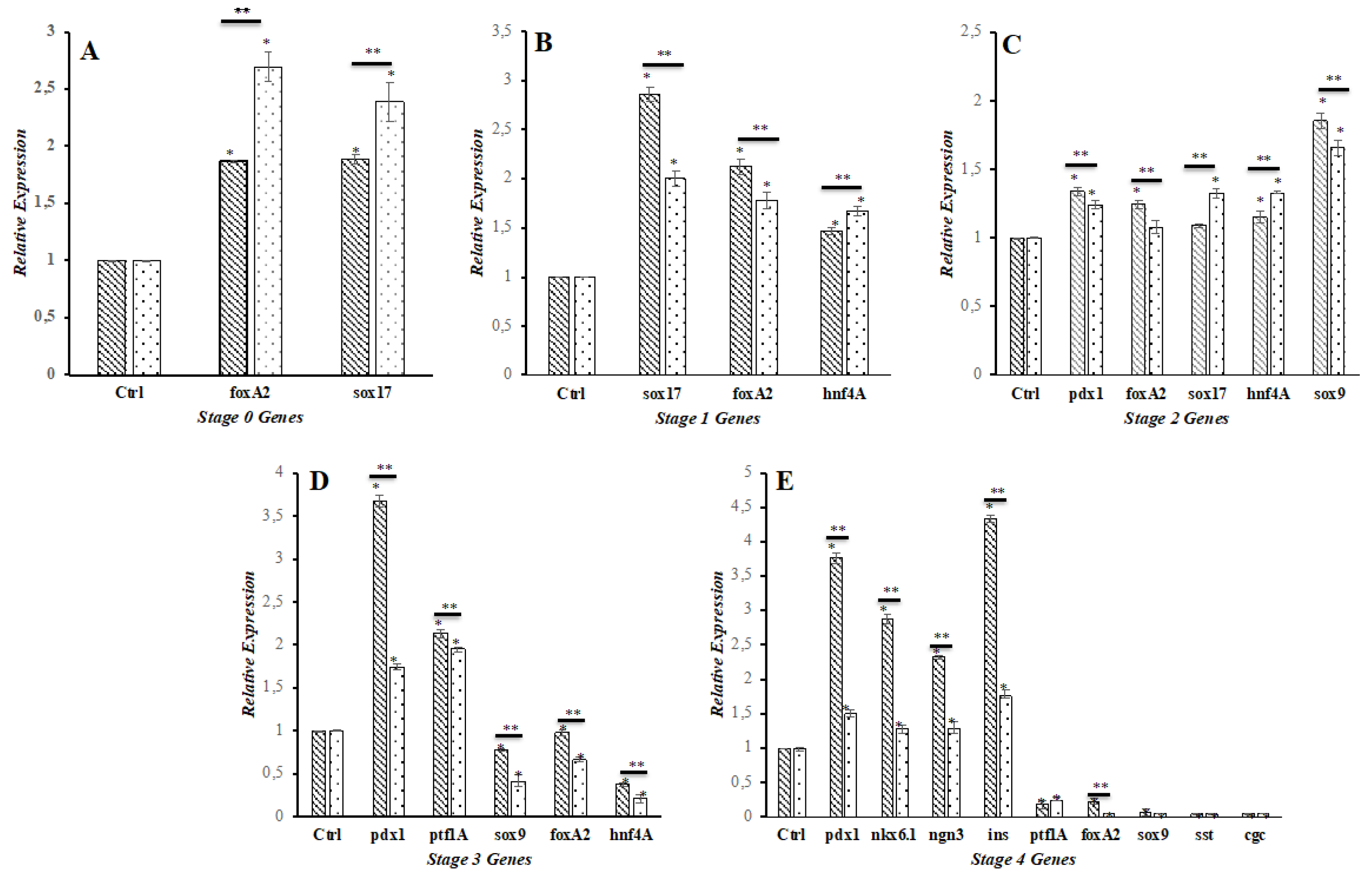

3.2. Effect of shKDM4A on iPSCs Differentiation to Pancreatic ß-Like Cells (PßLC)

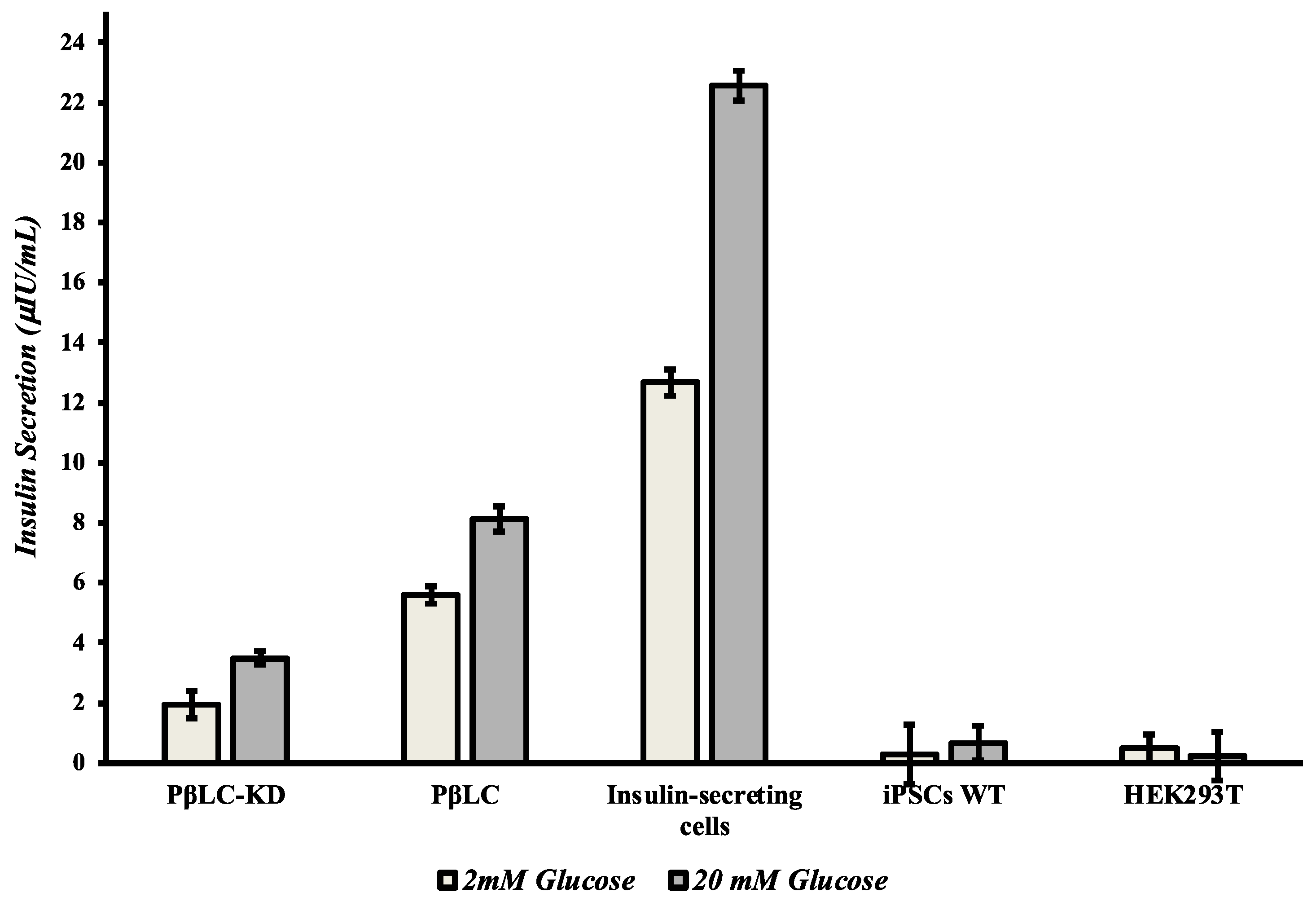

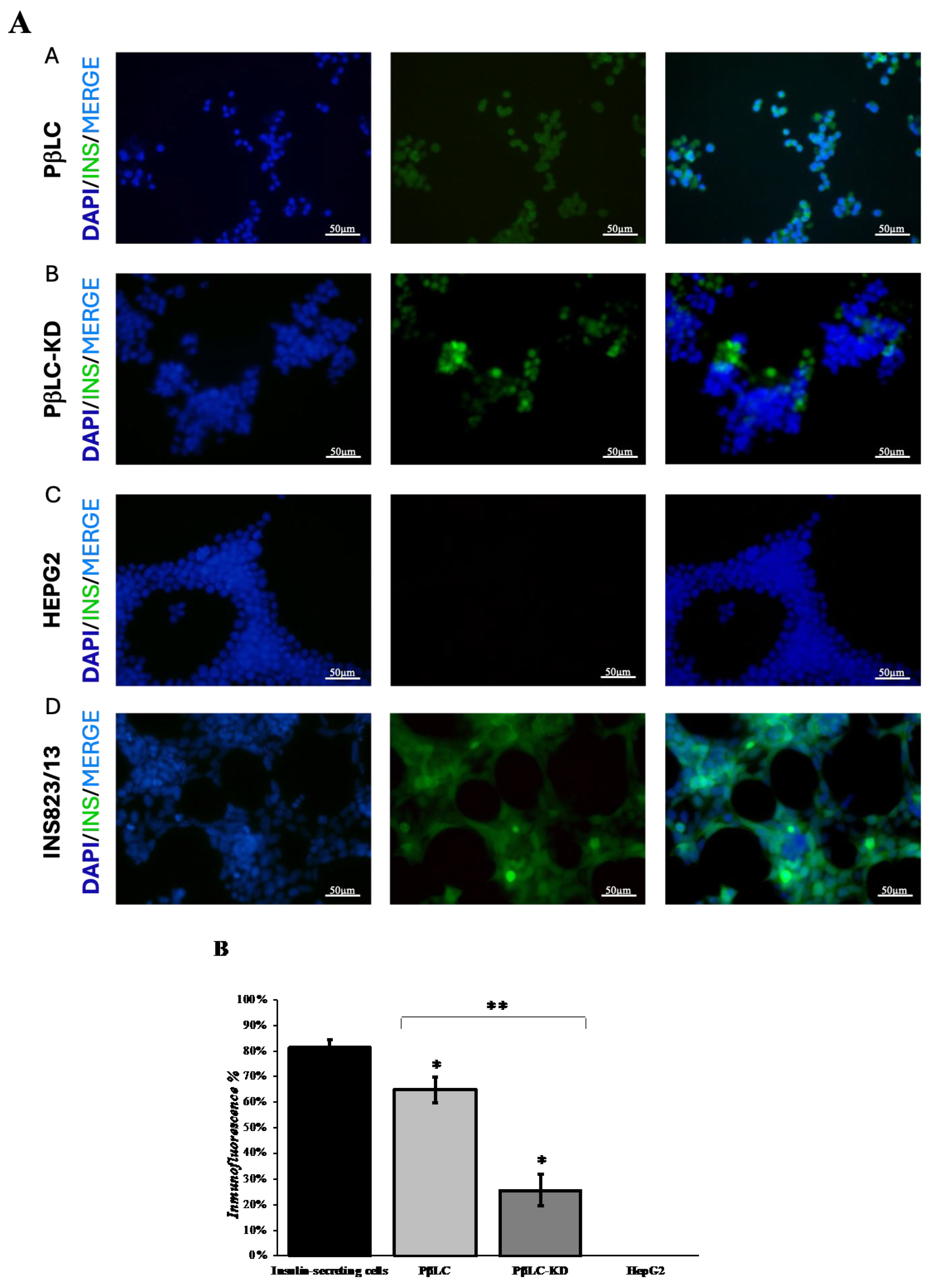

3.3. PβLC KDM4A-KD Insulin Secretion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosales, W.; Lizcano, F. The Histone Demethylase JMJD2A Modulates the Induction of Hypertrophy Markers in iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Front Genet 2018, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra-Calderas, L.; Gonzalez-Barrios, R.; Herrera, L.A.; Cantu de Leon, D.; Soto-Reyes, E. The role of the histone demethylase KDM4A in cancer. Cancer Genet 2015, 208, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, J.; Lizcano, F. Kdm4c is Recruited to Mitotic Chromosomes and Is Relevant for Chromosomal Stability, Cell Migration and Invasion of Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2018, 12, 1178223418773075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilichini, E.; Haumaitre, C. Implication of epigenetics in pancreas development and disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015, 29, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K. Cellular reprogramming. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Whetstine, J.R. Dynamic regulation of histone lysine methylation by demethylases. Mol Cell 2007, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Young, B.; Wang, Y.; Davidoff, A.M.; Rankovic, Z.; Yang, J. Recent Advances with KDM4 Inhibitors and Potential Applications. J Med Chem 2022, 65, 9564–9579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Yu, H. Structural insights into histone lysine demethylation. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2010, 20, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zang, J.; Whetstine, J.; Hong, X.; Davrazou, F.; Kutateladze, T.G.; Simpson, M.; Mao, Q.; Pan, C.H.; Dai, S.; et al. Structural insights into histone demethylation by JMJD2 family members. Cell 2006, 125, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.C.; Van Rechem, C.; Whetstine, J.R. Histone lysine methylation dynamics: establishment, regulation, and biological impact. Mol Cell 2012, 48, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Kim, G.W.; Jeon, Y.H.; Yoo, J.; Lee, S.W.; Kwon, S.H. Advances in histone demethylase KDM4 as cancer therapeutic targets. FASEB J 2020, 34, 3461–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, R.L.; Masson, N.; Dunne, K.; Flashman, E.; Kawamura, A. The Activity of JmjC Histone Lysine Demethylase KDM4A is Highly Sensitive to Oxygen Concentrations. ACS Chem Biol 2017, 12, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, N.L.; Dere, R. Mechanistic insights into KDM4A driven genomic instability. Biochem Soc Trans 2021, 49, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, W.L.; Janknecht, R. KDM4/JMJD2 histone demethylases: epigenetic regulators in cancer cells. Cancer Res 2013, 73, 2936–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wu, J.C. Epigenetic Modulations of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: Novel Therapies and Disease Models. Drug Discov Today Dis Models 2012, 9, e153–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninova, M.; Fejes Toth, K.; Aravin, A.A. The control of gene expression and cell identity by H3K9 trimethylation. Development 2019, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Qi, J.; Wei, B.; Yang, J.; Liang, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; et al. H3K9 methylation is a barrier during somatic cell reprogramming into iPSCs. Nat Genet 2013, 45, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicetto, D.; Zaret, K.S. Role of H3K9me3 heterochromatin in cell identity establishment and maintenance. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2019, 55, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.T.; Kooistra, S.M.; Radzisheuskaya, A.; Laugesen, A.; Johansen, J.V.; Hayward, D.G.; Nilsson, J.; Agger, K.; Helin, K. Continual removal of H3K9 promoter methylation by Jmjd2 demethylases is vital for ESC self-renewal and early development. EMBO J 2016, 35, 1550–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Everett, L.J.; Lim, H.W.; Patel, N.A.; Schug, J.; Kroon, E.; Kelly, O.G.; Wang, A.; D’Amour, K.A.; Robins, A.J.; et al. Dynamic chromatin remodeling mediated by polycomb proteins orchestrates pancreatic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xie, F.; Liu, P.; Xu, S. Differentiation of pluripotent stem cells for regenerative medicine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016, 471, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Chang, C.; Huang, G.; Zhou, Z. The Role of Epigenetics in Type 1 Diabetes. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1253, 223–257. [Google Scholar]

- Efrat, S. Epigenetic Memory: Lessons From iPS Cells Derived From Human beta Cells. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11, 614234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyave, F.; Uscategui, Y.; Lizcano, F. From iPSCs to Pancreatic beta Cells: Unveiling Molecular Pathways and Enhancements with Vitamin C and Retinoic Acid in Diabetes Research. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Doi, A.; Wen, B.; Ng, K.; Zhao, R.; Cahan, P.; Kim, J.; Aryee, M.J.; Ji, H.; Ehrlich, L.I.; et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2010, 467, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Luan, Y.; Feng, Q.; Chen, X.; Qin, B.; Ren, K.D.; Luan, Y. Epigenetics and Beyond: Targeting Histone Methylation to Treat Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 807413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbe, R.M.; Holowatyj, A.; Yang, Z.Q. Histone lysine demethylase (KDM) subfamily 4: structures, functions and therapeutic potential. Am J Transl Res 2013, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Obayomi, S.M.B.; Wei, Z. Epigenetic Regulation of beta Cell Identity and Dysfunction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 725131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.B.B.; Kimura, C.H.; Colantoni, V.P.; Sogayar, M.C. Stem cells differentiation into insulin-producing cells (IPCs): recent advances and current challenges. Stem Cell Res Ther 2022, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manea, T.; Nelson, J.K.; Garrone, C.M.; Hansson, K.; Evans, I.; Behrens, A.; Sancho, R. USP7 controls NGN3 stability and pancreatic endocrine lineage development. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.; Dubauskaite, J.; Melton, D.A. Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development 2002, 129, 2447–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Banerjee, A.; Herring, C.A.; Attalla, J.; Hu, R.; Xu, Y.; Shao, Q.; Simmons, A.J.; Dadi, P.K.; Wang, S.; et al. Neurog3-Independent Methylation Is the Earliest Detectable Mark Distinguishing Pancreatic Progenitor Identity. Dev Cell 2019, 48, 49–63 e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboa, D.; Barsby, T.; Lithovius, V.; Saarimaki-Vire, J.; Omar-Hmeadi, M.; Dyachok, O.; Montaser, H.; Lund, P.E.; Yang, M.; Ibrahim, H.; et al. Functional, metabolic and transcriptional maturation of human pancreatic islets derived from stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40, 1042–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, N.; Dhawan, S. DNA Methylation Patterning and the Regulation of Beta Cell Homeostasis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 651258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantuzzi, F.; Toivonen, S.; Schiavo, A.A.; Chae, H.; Tariq, M.; Sawatani, T.; Pachera, N.; Cai, Y.; Vinci, C.; Virgilio, E.; et al. In depth functional characterization of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived beta cells in vitro and in vivo. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 967765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwakoti, P.; Rennie, C.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.J.; Tuch, B.E.; McClements, L.; Xu, X. Challenges with Cell-based Therapies for Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2023, 19, 601–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Ikeda, Y. PDX1, Neurogenin-3, and MAFA: critical transcription regulators for beta cell development and regeneration. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017, 8, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, B.; Karam, M.; Al-Khawaga, S.; Abdelalim, E.M. Enhanced differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into pancreatic progenitors co-expressing PDX1 and NKX6.1. Stem Cell Res Ther 2018, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigha, II; Abdelalim, E.M. NKX6.1 transcription factor: a crucial regulator of pancreatic beta cell development, identity, and proliferation. Stem Cell Res Ther 2020, 11, 459. [CrossRef]

- Mannar, V.; Boro, H.; Patel, D.; Agstam, S.; Dalvi, M.; Bundela, V. Epigenetics of the Pathogenesis and Complications of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. touchREV Endocrinol 2023, 19, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Wary, K.K.; Revskoy, S.; Gao, X.; Tsang, K.; Komarova, Y.A.; Rehman, J.; Malik, A.B. Histone Demethylases KDM4A and KDM4C Regulate Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells to Endothelial Cells. Stem Cell Reports 2015, 5, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Gamero, C.; Malla, S.; Aguilo, F. LSD1: Expanding Functions in Stem Cells and Differentiation. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.F.; Zhou, S.Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, W.; Li, N.; He, F.; Li, F.R. Inhibition of LSD1 promotes the differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells into insulin-producing cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2020, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsby, T.; Otonkoski, T. Maturation of beta cells: lessons from in vivo and in vitro models. Diabetologia 2022, 65, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimala, S.; Kumar, C.A.; Allouh, M.Z.; Ansari, S.A.; Emerald, B.S. Epigenetic modifications in pancreas development, diabetes, and therapeutics. Med Res Rev 2022, 42, 1343–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesolowska-Andersen, A.; Jensen, R.R.; Alcantara, M.P.; Beer, N.L.; Duff, C.; Nylander, V.; Gosden, M.; Witty, L.; Bowden, R.; McCarthy, M.I.; et al. Analysis of Differentiation Protocols Defines a Common Pancreatic Progenitor Molecular Signature and Guides Refinement of Endocrine Differentiation. Stem Cell Reports 2020, 14, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Accili, D. Reversing pancreatic beta-cell dedifferentiation in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Exp Mol Med 2023, 55, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Cho, H.; Rickert, R.W.; Li, Q.V.; Pulecio, J.; Leslie, C.S.; Huangfu, D. FOXA2 Is Required for Enhancer Priming during Pancreatic Differentiation. Cell Rep 2019, 28, 382–393 e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, K.; Polonsky, K.S. Pdx1 and other factors that regulate pancreatic beta-cell survival. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009, 11 (Suppl. 4), 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.C.H.; Lee, Y.L.; Fong, S.W.; Wong, C.C.Y.; Ng, E.H.Y.; Yeung, W.S.B. Hyperglycemia impedes definitive endoderm differentiation of human embryonic stem cells by modulating histone methylation patterns. Cell Tissue Res 2017, 368, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millman, J.R.; Xie, C.; Van Dervort, A.; Gurtler, M.; Pagliuca, F.W.; Melton, D.A. Generation of stem cell-derived beta-cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliuca, F.W.; Millman, J.R.; Gurtler, M.; Segel, M.; Van Dervort, A.; Ryu, J.H.; Peterson, Q.P.; Greiner, D.; Melton, D.A. Generation of functional human pancreatic beta cells in vitro. Cell 2014, 159, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastidas-Ponce, A.; Roscioni, S.S.; Burtscher, I.; Bader, E.; Sterr, M.; Bakhti, M.; Lickert, H. Foxa2 and Pdx1 cooperatively regulate postnatal maturation of pancreatic beta-cells. Mol Metab 2017, 6, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.L.; Liu, F.F.; Sander, M. Nkx6.1 is essential for maintaining the functional state of pancreatic beta cells. Cell Rep 2013, 4, 1262–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura-Nakajima, C.; Sakaguchi, K.; Hatano, Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Okazaki, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Yamane, T.; Oishi, Y.; Kamimoto, K.; Iwatsuki, K. Ngn3-Positive Cells Arise from Pancreatic Duct Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.J.; Peng, Y.C.; Yang, K.M. Cellular signaling pathways regulating beta-cell proliferation as a promising therapeutic target in the treatment of diabetes. Exp Ther Med 2018, 16, 3275–3285. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.E.; Newgard, C.B. Mechanisms controlling pancreatic islet cell function in insulin secretion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Har-Zahav, A.; Lixandru, D.; Cheishvili, D.; Matei, I.V.; Florea, I.R.; Aspritoiu, V.M.; Blus-Kadosh, I.; Meivar-Levy, I.; Serban, A.M.; Popescu, I.; et al. The role of DNA demethylation in liver to pancreas transdifferentiation. Stem Cell Res Ther 2022, 13, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name |

Forward CCGGGACTGCTGTTTATGCTCATTACTCGAGTAAT GAGCATAAACAGCAGTCTTTTTG |

Reverse AATTCAAAAAGACTGCTGTTTATGCTCATTACTCGAGTA ATGAGCATAAACAGCAGTC |

| Name | Forward | Reverse |

| Kdm4a | TGCGGCAAGTTGAGGATGGTCT | GCTGCTTGTTCTTCCTCCTCATC |

| foxA2 | GGAACACCACTACGCCTTCAAC | AGTGCATCACCTGTTCGTAGGC |

| sox17 | ACGCTTTCATGGTGTGGGCTAAG | GTCAGCGCCTTCCACGACTTG |

| hnf4A | GGTGTCCATACGCATCCTTGAC | AGCCGCTTGATCTTCCCTGGAT |

| pdx1 | GAAGTCTACCAAAGCTCACGCG | GGAACTCCTTCTCCAGCTCTAG |

| sox9 | AGGAAGCTCGCGGACCAGTAC | GGTGGTCCTTCTTGTGCTGCAC |

| ptf1A | GAAGGTCATCATCTGCCATCGG | CCTTGAGTTGTTTTTCATCAGTC |

| nkx6.1 | CCTATTCGTTGGGGATGACAGAG | TCTGTCTCCGAGTCCTGCTTCT |

| ngn3 | CCTAAGAGCGAGTTGGCACTGA | AGTGCCGAGTTGAGGTTGTGCA |

| ins | ACGAGGCTTCTTCTACACACCC | TCCACAATGCCACGCTTCTGCA |

| gcg | CGTTCCCTTCAAGACACAGAGG | ACGCCTGGAGTCCAGATACTTG |

| sst | CCAGACTCCGTCAGTTTCTGCA | TTCCAGGGCATCATTCTCCGTC |

| actB | CACCATTGGCAATGAGCGGTTC | AGGTCTTTGCGGATGTCCACGT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).