Abbreviations: mast cell tumor (MCT); mammary gland tumor (MGT); tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs); vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

1. Introduction

Mast cells are bone marrow-derived cells involved in allergic and hypersensitivity reactions and also secrete histamine, heparin, and proteases 1. Mast cell tumors (MCTs) account for 21% of common dog skin cancers 2, and Boxers (1.95%) and Golden Retrievers (1.39%) are commonly known to develop MCTs 3. The metastasis of an MCT to another organ is approximately 4% 4. In dogs, MCTs mostly occur on the skin 5, but they can also occur in other organs, such as the gastrointestinal tract 6, oral mucosa 7, and lungs 8. Primary mast cell tumors originating from lymph nodes are exceedingly rare, with only a few reports having documented cases in visceral lymph nodes such as the hepatopancreatic lymph node 9 and the mesenteric lymph node 10 11. To date, there have been no documented cases of primary mast cell tumors originating from cutaneous lymph nodes in dogs. Here, the authors report the first canine case of a primary mast cell tumor originating from the inguinal lymph node. Additionally, in humans, mast cells are associated with various types of tumors, either contributing to their inhibition or promoting their growth 12. Mast cells are hypothesized to contribute to the development of canine mammary malignant tumors (MGTs) by promoting angiogenesis, similar to some tumors described in the human species 13. The role of MCTs in promoting MGT progression is not fully elucidated, although evidence from human studies suggests that mast cells play a role in weakening stromal–epithelial interactions, and this process may contribute to MGT development and facilitate angiogenesis 12. The case in this study also supports this point, as the MCT primarily originated from the nearby inguinal lymph node and facilitated the concurrent growth of MGT. We investigated the molecular mechanism of correlation between MCT and MGT through a literature review and provided a plausible explanation of this case by focusing on vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) 14 and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) 15.

In July 2024, a 9-year-old intact female Maltese was diagnosed with kidney stones and a spleen tumor at a local hospital and was referred to Yeeun Animal Hospital. At Yeeun Animal Hospital, tumors in the 3rd and 5th mammary glands on the left were additionally confirmed via physical examination. Cytological examination was conducted on two palpable masses in the left mammary region.

2. Case Presentation

In March 16, 2024, splenic tumor and kidney stones were incidentally found in a 9-year-old intact female Maltese visiting a local hospital and were referred to Yeeun Ani-mal Hospital (Seoul, South Korea). After physical examination on Yeeun Animal hospital, mammary gland masses were additionally found through palpation which were located in the left 3rd and 5th mammary gland. In May 1, Fine needle aspiration (FNA) was done in the left 3rd and 5th mammary gland and after checking mast cell tumor in the left 5th mammary gland through FNA and benign tumor in the left 3rd mammary gland, efforts to find a clear primary mast cell tumor origin including additional physical examination, radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography were performed in May 4.

After the examination and procedures, hydronephrosis arose due to a ureteral stone descending from the left kidney. Therefore, emergency surgery was performed in May 8 with comprehensive surgical procedure including ureterotomy for ureteral stent and stone removal and left partial mastectomy with inguinal lymph node, Splenectomy and ovariohysterectomy. Also, histopathological examination was performed by Antech (Seongnam, South Korea) after the comprehensive surgery and the results were nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (spleen), grade 1 mammary complex carcinoma (left third mammary tumor), and metastatic mast cell tumor (left inguinal lymph node), respectively, in May 23 as shown in

Table 1. Additional C-kit mutation PCR test was done by the Michigan State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (MI, USA) in June 2024. At the pet owner's request, IHC (immuno-histochemical staining) staining was not performed. Mast cell leukemia was ruled out via a peripheral blood smear and finally CT scans to find mast cell tumor origin were performed in June 21, 2024 at Shine Animal Hospital (Seoul, South Korea). After CT scan, additional biopsy of the mast cell tumor origin candidates was performed by Antech and three inguinal nodules were diagnosed as mild lymphoid follicular hyperplasia, and the other three masses found in the hind body were diagnosed as nodular sebaceous hyperplasia, lipoma, and normal-haired skin respectively, in June 27, 2024 (table 1).

Based on all imaging tests and biopsies that were performed on this dog, the tumor was diagnosed as a primary mast cell tumor, which originated from the left inguinal lymph node. Even though the findings of histopathological examinations, such as those shown in

Figure 1D, are generally seen in metastatic mast cell tumors, they may also be seen in primary mast cell tumors. There were no other findings of primary mast cell tumors in other organs (supplementary figure, figure 2), such as those shown in

Table 1, as confirmed through consecutive biopsy and CT scans.

After finding the origin of the tumor, the patient received vinblastine and prednisolone-based chemotherapy 16 for 16 weeks as C-kit PCR 8 and 11 was negative (

Table 2) which can be interpreted as less likely to respond to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The chemotherapy protocol was started on July 20, vinblastine was administered intravenously at a dose of 2 mg/m² biweekly for a total of eight treatments (16 weeks). Prednisolone (2 mg/kg) was orally administered daily and was gradually tapered before discontinuation. As of October 2024, no metastases, recurrences, or new tumors were observed in follow-up ex-aminations. As of February 2025, the patient is recovering well with no clinical signs or tumor recurrence to date and as well in April 2025.

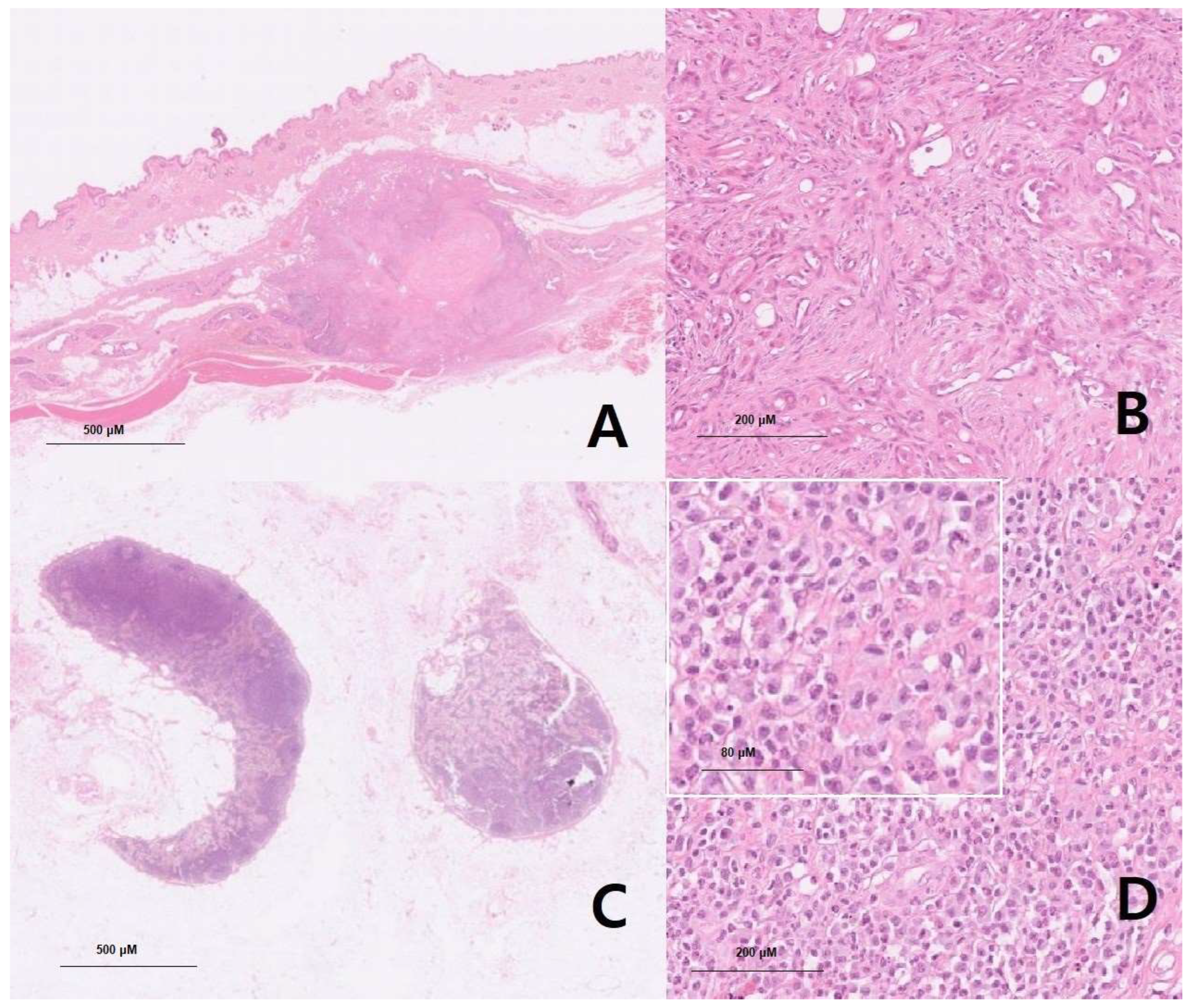

Specimens A and B: Left third mammary gland mass, 0.8 cm x 0.6 cm (4.4 cm x 3.2 cm including skin), firm and solid with no hemorrhage, and solitary.

MICROSCOPIC DESCRIPTION: (A) At X40 magnification, neoplastic epithelial cells were surrounded by myoepithelial cells and were well demarcated and nodular. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis were moderate in the neoplastic cells in the mammary mass specimen, with no mitotic figures observed. (B) At X100 magnification, myoepithelial cells appeared spindle-shaped to stellate with in-distinct cell borders, with moderate amounts of amphophilic to eosinophilic to basophilic vacuolated to fibrillary to homogeneous cytoplasm and ovoid to elongate open nuclei with variable amounts of coarse chromatin and either indistinct or 1-2 small nucleoli. Neo-plastic cells were polygonal to cuboidal and had variable distinct cell borders. Necrosis was seen in the central area, while numerous plasma cells and lymphocytes were present in the periphery. Grade 1 mammary complex carcinoma was confirmed comprehensively. Scale bars = 500 μM, and 200 μM (inset).

Specimens C and D: Left inguinal lymph node, 1.1 cm x 1.0 cm, firm and solid with no hemorrhage, and solitary.

MICROSCOPIC DESCRIPTION: (C) At X40 magnification, moderate follicular and paracortical hyperplasia were observed in the lymph node specimen, accompanied by moderate sinus histiocytosis. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis were moderate, and mitotic figures were frequently observed. (D) At X100 magnification, the neoplastic mast cells featured distinct cell borders and exhibited a round morphology with moderate amounts of cytoplasm containing basophilic granules. Finely stippled chromatin was centrally located in an oval nucleus. A small number of eosinophils were mixed among neoplastic mast cells. These effacements of normal nodal structure, along with an overt number of mast cells, are generally seen in metastatic mast cell tumors (HN3, scale HN0-HN3). Scale bars = 500 μM, 200 μM and 80 μM (inset).

Figure 2.

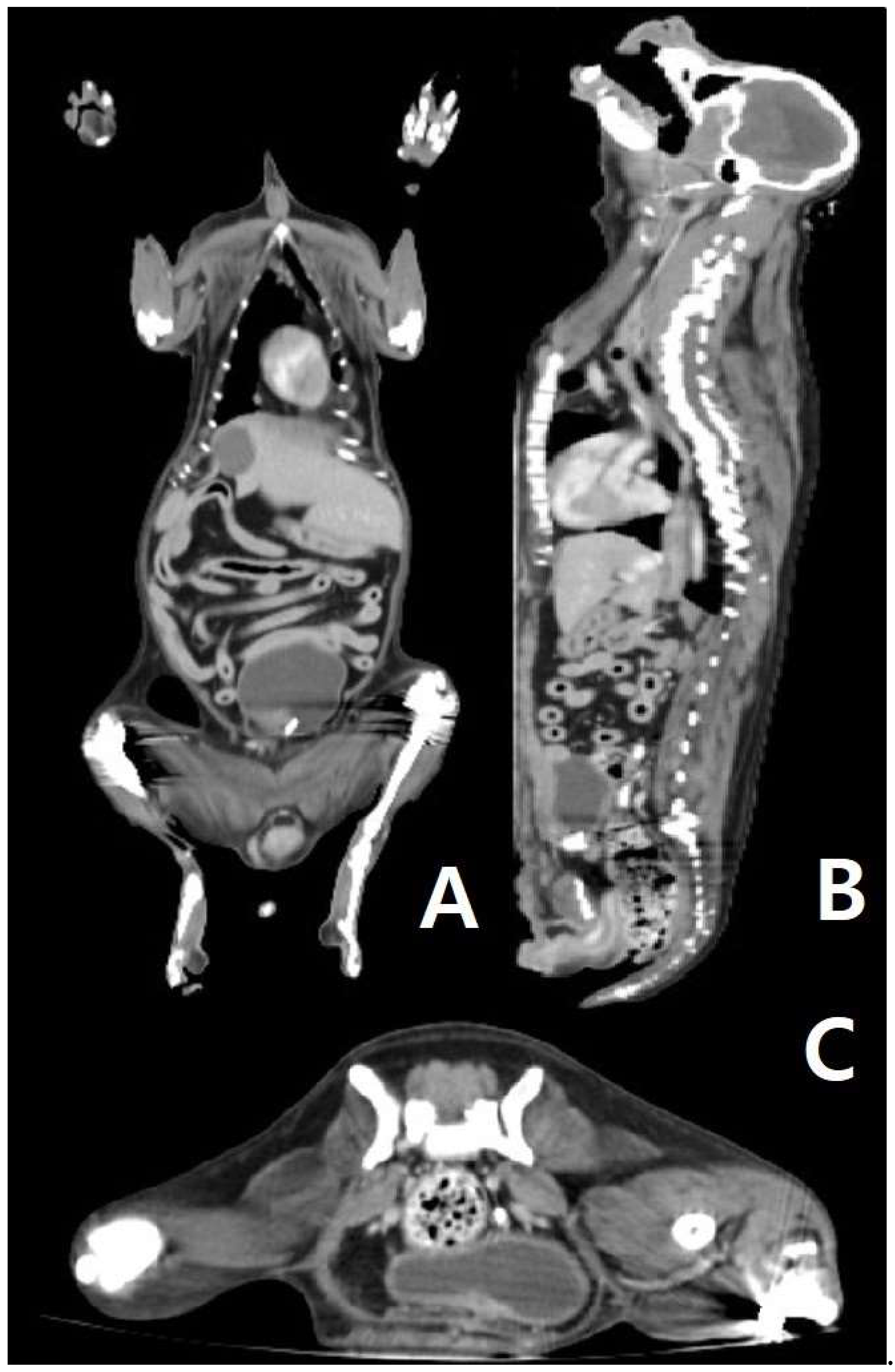

(A, B, and C): CT scan of the patient’s body. (A) In the dorsal view of the CT scan, there is no sign of a primary tumor in the abdominal organ and thorax. (B) In the sagittal view of the CT scan, there is no sign of a primary tumor in the abdominal organ and thorax. (C) In the transverse view of the CT scan (posterior abdomen), there is no sign of a primary tumor in the abdominal organ and thorax.

Figure 2.

(A, B, and C): CT scan of the patient’s body. (A) In the dorsal view of the CT scan, there is no sign of a primary tumor in the abdominal organ and thorax. (B) In the sagittal view of the CT scan, there is no sign of a primary tumor in the abdominal organ and thorax. (C) In the transverse view of the CT scan (posterior abdomen), there is no sign of a primary tumor in the abdominal organ and thorax.

3. Discussion

Canine MCTs primarily occur in the skin, as previously described, with numerous cases reported of cutaneous MCT metastasizing to other organs, such as the heart 17, bone marrow18, urinary bladder, spleen, liver, and kidney 19. The involvement of lymph nodes is common, and identifying the primary organ of MCTs is essential for prognosis and treatment. 19.

During the process of finding the origin of the MCT, mast cell leukemia, which is rare in dogs 20, was first considered due to the infiltration of the mast cells in the lymph nodes. However, this was excluded since there was no increase in the number of mast cells in a peripheral blood smear. During the first surgery, the large tumor on the left mammary gland and the spleen were removed, and these organs were found to not be a primary MCT. After surgery to identify the primary organ of MCT, even the small nodules found through CT were biopsied, but no suspected mast cell tumors other than the lymph nodes were found. Therefore, the final diagnosis for the patient in this case was a primary MCT of the lymph node and it is significant as being first case to utilize ultrasound, CT scan and biopsy to scrutinize the origin.

In general, canine lymph node primary MCT is uncommon, and to the authors’ knowledge, there have been no case reports since 2009 11. Previous reports of primary MCT in lymph nodes are rare and include cases in the hepatopancreatic lymph node 9, cranial mesenteric lymph node 10, and mesenteric lymph node 11. This is the first reported case of MCT primarily occurring in cutaneous lymph nodes, notable for its academic significance in employing advanced imaging techniques for the identification of primary cutaneous MCT and performing biopsies on all suspicious lesions. Cutaneous lymph nodes have the advantage of being easily palpated during physical examination and accessible for cytological evaluation. If mast cell infiltration is observed in lymph nodes with concurrent MCT in a nearby skin mass, which can be confirmed by cytological examination, it is generally considered lymph node metastasis from proximal skin tumors. However, as shown in this case, if a primary mass is not identified near the lymph nodes via physical examination or imaging, the possibility of primary MCT in the lymph nodes should be considered. This study represents an essential trial to challenge existing assumptions and expand the diagnostic perspective in small-animal cancer.

In addition, this patient did not show any lymph node changes upon physical examination as of December 2024, after the first diagnosis of primary MCT of lymph nodes in March 2024, and other skin masses are not palpable. Also, X-ray U/S phase metastasis has not been confirmed. It is also believed to enhance the academic value of the paper by providing prognostic information for primary surface lymph node metastatic cancer (MCT) treatment involving surgical removal and adjuvant chemotherapy through continuous follow-up monitoring. Since there was no c-kit mutation in the specimen, as confirmed by PCR test, chemotherapy was performed as opposed to targeted therapy according to the standard protocol 21 22.

3.1. Correlation Between MCT and MGT Growth

Although it is uncertain whether MGT is positively correlated with primary MCT, and in some case reports, MCT and MGT arise concurrently 23, MGT is common in senior intact female dogs; therefore, the occurrence of MCT and MGT in the patient may be an independent event. Additionally, BRCA-1 gene mutation, which is crucial in breast cancer, affects the regulation of VEGF, which leads to dysregulation of the gene and increases angiogenesis in humans 24. Also, mast cells release VEGF and promote tumor angiogenesis in humans 25, and a similar phenomenon was detected in canines 26, but the detailed mechanism has not been well documented in canines compared to humans. On the other hand, there are subclasses of macrophages: M0 27, M1, M2, and M2-like TAM 28. MGT and TAM are positively correlated in canines29, and TAM also releases cytokines such as VEGF, TNF- α. TAM and mast cells work together in the tumor environment, inhibiting or facilitating the progression of the tumor depending on the stage 30. It has also been reported that tumor-associated mast cells are less frequently observed in malignant mammary gland tumors than in mammary gland hyperplasia 31. Considering these factors together, it is not clear whether the growth of MCT and MGT is positively correlated because it is multifactorial.

3.2. Hypothesis of Rare Primary Lymph Node MCT

Mast cells release VEGF 32, and the overexpression of VEGF in the skin leads to the growth of tumors 33. Therefore, by putting these facts together, it is plausible to determine that cutaneous MCT is more common than in other organs. On the other hand, lymphatic vessel endothelium is more permeable than blood vessel endothelium 34, which makes it more difficult to attach to the blood vessel, contributing to the tumor microenvironment 35. However, mast cells lead to chemotaxis to laminin 36 and is essential in the metastasis of primary tumors, as mediated by macrophages 37. Nevertheless, it is theoretically possible that MCT primarily originates from the lymph node, as previously reported in the visceral lymph node 9, and this study is the first to report MCT originating from the cutaneous lymph node.

4. Conclusions

This case report is significant because it is the first to report MCTs primarily originating from the inguinal lymph node utilizing ultrasound, CT scan and biopsy. We also provide possible explanation for rarity of MCT originated from lymph node which can be investigated in future follow up research. Additionally, since there have been very few cases of primary MCT in lymph nodes, no histopathological criteria currently exist for assessing prognosis. This case study also suggests that if numerous cases of lymph node primary MCT are reported, pathological criteria for prognosis evaluation can be examined in a follow-up study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L., K.C., and G.K.; formal analysis and methodology, N.L. and K.C.; writing, N.L. and K.C.; supervision, K.C.; project administration, N.L. and K.C.; funding acquisition, N.L. and K.C. All authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed consent was waived (or exempted) from the IRB (SNUIRB-2025-NH-005) due to the retrospective nature of this case study. Prior to collecting samples, all pet owners signed informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A (Supplementary Figures)

Figure 1.

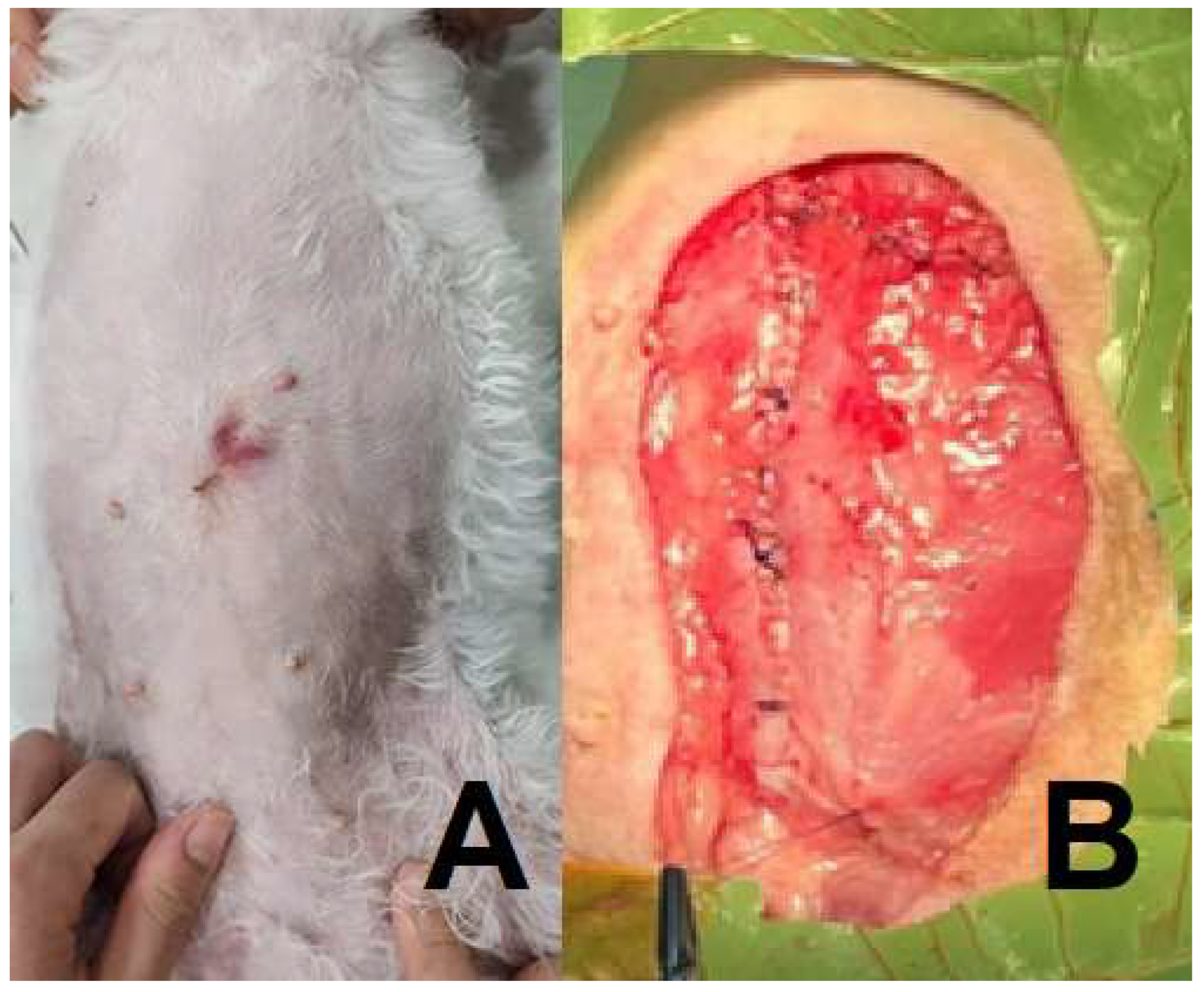

(A, B). (A) Macroscopic lesion of the left inguinal lymph node mass. (B) Surgical removal of the left 3rd, 4th, and 5th mammary gland tumors.

Figure 1.

(A, B). (A) Macroscopic lesion of the left inguinal lymph node mass. (B) Surgical removal of the left 3rd, 4th, and 5th mammary gland tumors.

Figure 2.

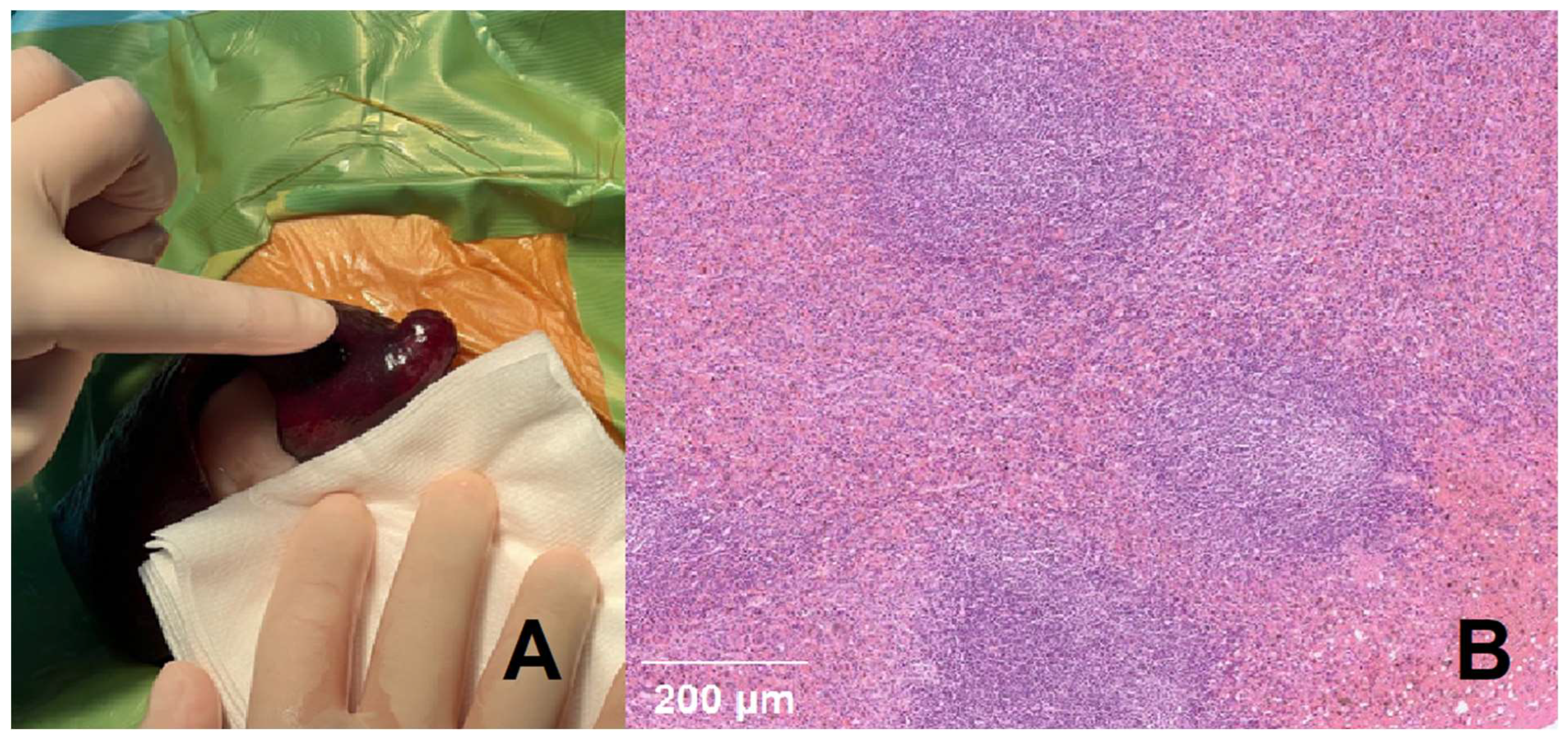

(A, B). (A) Macroscopic lesion of the splenic mass. (B) Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of spleen, Sections of the spleen contained a large nodular mass that was characterized by proliferation of multiple hyperplastic lymphoid follicles surrounded by red blood cells ad-mixed with hematopoietic precursor cells and megakaryocytes. Lymphoid follicles had retained polarity and prominent mantle zones. There was no evidence of neoplastic dis-ease within the sections examined histologically. (Scale bars = 200 μM, inset).).

Figure 2.

(A, B). (A) Macroscopic lesion of the splenic mass. (B) Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of spleen, Sections of the spleen contained a large nodular mass that was characterized by proliferation of multiple hyperplastic lymphoid follicles surrounded by red blood cells ad-mixed with hematopoietic precursor cells and megakaryocytes. Lymphoid follicles had retained polarity and prominent mantle zones. There was no evidence of neoplastic dis-ease within the sections examined histologically. (Scale bars = 200 μM, inset).).

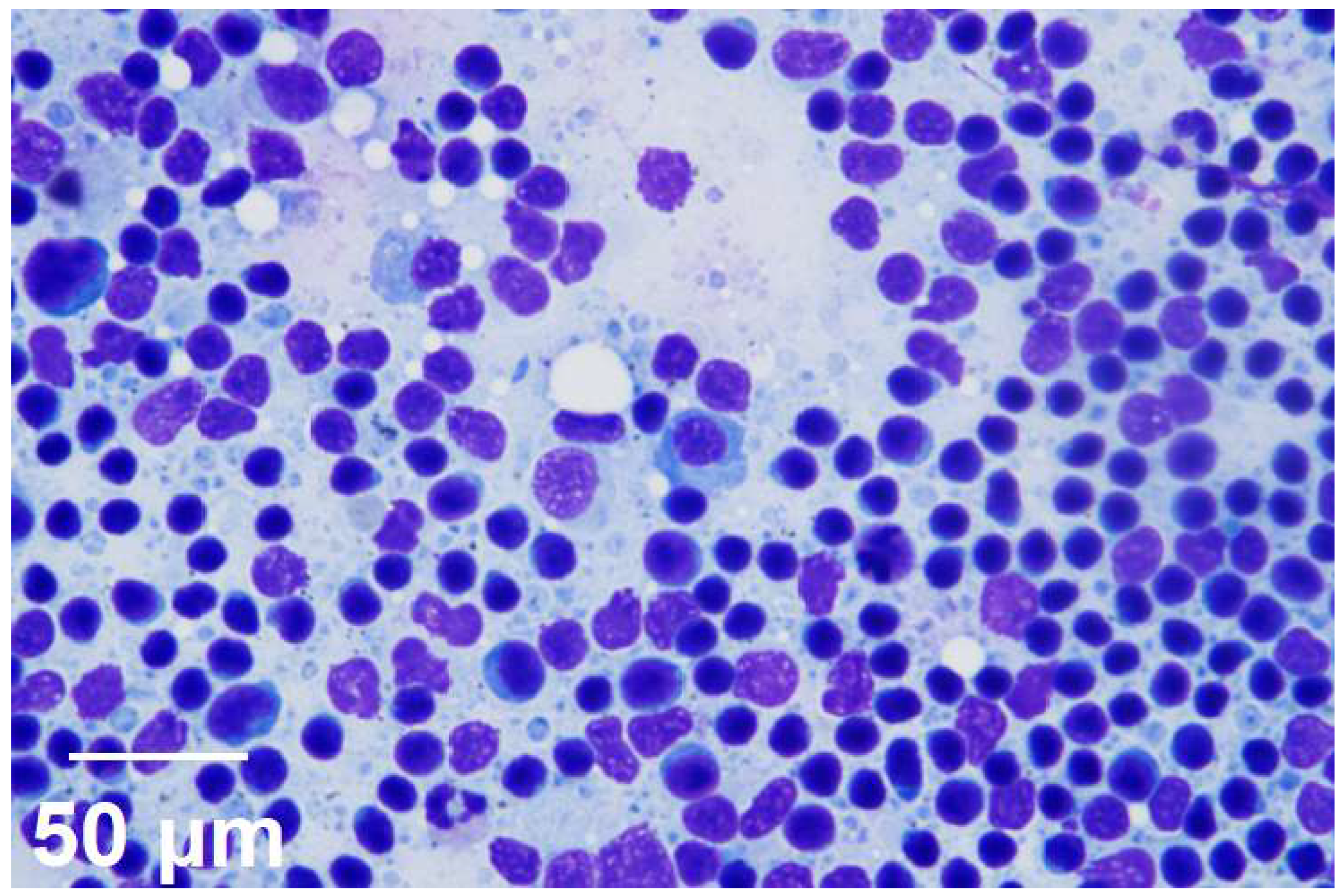

Figure 3.

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (right inguinal lymph node), Moderate cellularity, mild erythrocytes infiltration, most of lymphocyte are small with small number of large lymphocyte and neutrophil, macrophage and plasma cell are shown. There is no evidence of infectious agent. (Scale bars = 50 μM, inset).

Figure 3.

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (right inguinal lymph node), Moderate cellularity, mild erythrocytes infiltration, most of lymphocyte are small with small number of large lymphocyte and neutrophil, macrophage and plasma cell are shown. There is no evidence of infectious agent. (Scale bars = 50 μM, inset).

References

- Amin, K. The role of mast cells in allergic inflammation. Respiratory medicine 2012, 106, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiupel, M. Mast cell tumors. Tumors in domestic animals 2016, 176–202. [Google Scholar]

- Shoop, S. J.; Marlow, S.; Church, D. B.; English, K.; McGreevy, P. D.; Stell, A. J.; Thomson, P. C.; O’Neill, D. G.; Brodbelt, D. C. Prevalence and risk factors for mast cell tumours in dogs in England. Canine Genetics and Epidemiology 2015, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Pearl, D.; Yager, J.; Best, S.; Coomber, B.; Foster, R. Canine subcutaneous mast cell tumor: characterization and prognostic indices. Veterinary Pathology 2011, 48, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welle, M. M.; Bley, C. R.; Howard, J.; Rüfenacht, S. Canine mast cell tumours: a review of the pathogenesis, clinical features, pathology and treatment. Veterinary dermatology 2008, 19, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, K.; Yamagami, T.; Nomura, K.; Narama, I. Mast cell tumors of the gastrointestinal tract in 39 dogs. Veterinary pathology 2002, 39, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.; Cripps, P.; Blackwood, L.; Berlato, D.; Murphy, S.; Grant, I. Canine oral mucosal mast cell tumours. Veterinary and comparative oncology 2016, 14, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, O.; de Lorimier, L.-P.; Beauregard, G.; Overvelde, S.; Johnson, S. Presumptive primary pulmonary mast cell tumor in 2 dogs. The Canadian Veterinary Journal 2017, 58, 591. [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik, A.; MacEwen, E.; Black, A.; Luckow, S. Extracutaneous mast-cell tumor in the dog. Veterinary Pathology 1982, 19, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.; Harvey, H.; Roth, L.; Callihan, D. Clostridial peritonitis associated with a mast cell tumor in a dog. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1986, 188, 188–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, K.; Sakaguchi, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Tominaga, M.; Hirayama, K.; Kadosawa, T.; Taniyama, H. Systemic candidiasis and mesenteric mast cell tumor with multiple metastases in a dog. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2009, 71, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, P.; Castellani, M. L.; Kempuraj, D.; Salini, V.; Vecchiet, J.; Tetè, S.; Mastrangelo, F.; Perrella, A.; De Lutiis, M. A.; Tagen, M. Role of mast cells in tumor growth. Annals of Clinical & Laboratory Science 2007, 37, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Lavalle, G.; Bertagnolli, A.; Tavares, W.; Ferreira, M.; Cassali, G. Mast cells and angiogenesis in canine mammary tumor. Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia 2010, 62, 1348–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D.; Annese, T.; Tamma, R. Controversial role of mast cells in breast cancer tumor progression and angiogenesis. Clinical Breast Cancer 2021, 21, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertola, L.; Pellizzoni, B.; Giudice, C.; Grieco, V.; Ferrari, R.; Chiti, L. E.; Stefanello, D.; Manfredi, M.; De Zani, D.; Recordati, C. Tumor-associated macrophages and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in canine cutaneous and subcutaneous mast cell tumors. Veterinary Pathology 2024, 03009858241244851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamm, D. H.; Mauldin, E. A.; Vail, D. M. Prednisone and vinblastine chemotherapy for canine mast cell tumor—41 cases (1992–1997). Journal of veterinary internal medicine 1999, 13, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yale, A. D.; Szladovits, B.; Stell, A. J.; Fitzgerald, S. D.; Priestnall, S. L.; Suarez-Bonnet, A. High-grade cutaneous mast cell tumour with widespread intrathoracic metastasis and neoplastic pericardial effusion in a dog. Journal of Comparative Pathology 2020, 180, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconato, L.; Bettini, G.; Giacoboni, C.; Romanelli, G.; Cesari, A.; Zatelli, A.; Zini, E. Clinicopathological features and outcome for dogs with mast cell tumors and bone marrow involvement. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2008, 22, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P. R.; Bianchi, M. V.; Bandinelli, M. B.; Rosa, R. B.; Echenique, J. V. Z.; Serpa Stolf, A.; Driemeier, D.; Sonne, L.; Pavarini, S. P. Pathological aspects of cutaneous mast cell tumors with metastases in 49 dogs. Veterinary Pathology 2022, 59, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIKASA, Y.; MORITA, T.; FUTAOKA, Y.; SATO, K.; SHIMADA, A.; KAGOTA, K.; MATSUDA, H. Connective tissue-type mast cell leukemia in a dog. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2000, 62, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, Y. N. B.; Soldi, L. R.; Silva, P. H. R. d.; Mesquita, C. M.; Paranhos, L. R.; Santos, T. R. d.; Silva, M. J. B. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors as an alternative treatment in canine mast cell tumor. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 10, 1188795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, D. R.; Wyatt, K. M.; Jardine, J. E.; Robertson, I. D.; Irwin, P. J. Vinblastine and prednisolone as adjunctive therapy for canine cutaneous mast cell tumors. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 2004, 40, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rifici, C.; Sfacteria, A.; Di Giorgio, S.; Giambrone, G.; Marino, G.; Mazzullo, G. Mast Cell Tumour and Mammary Gland Carcinoma Collision Tumour. Case report and literature review. Journal of the Hellenic Veterinary Medical Society 2022, 73, 4675–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, H.; Li, H.; Chun, P.; Avraham, S.; Avraham, H. K. Direct interaction between BRCA1 and the estrogen receptor regulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) transcription and secretion in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2002, 21, 7730–7739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrby, K. Mast cells and angiogenesis. Apmis 2002, 110, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebuzzi, L.; Willmann, M.; Sonneck, K.; Gleixner, K. V.; Florian, S.; Kondo, R.; Mayerhofer, M.; Vales, A.; Gruze, A.; Pickl, W. F. Detection of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptors Flt-1 and KDR in canine mastocytoma cells. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology 2007, 115, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D. A.; Myasoedova, V. A.; Revin, V. V.; Orekhov, A. N.; Bobryshev, Y. V. The impact of interferon-regulatory factors to macrophage differentiation and polarization into M1 and M2. Immunobiology 2018, 223, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Luo, J.; Guo, W.; Sun, L.; Lin, L. Targeting M2-like tumor-associated macrophages is a potential therapeutic approach to overcome antitumor drug resistance. NPJ Precision Oncology 2024, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L.; Rodrigues, M.; Gomes, D.; Salgado, B.; Cassali, G. Tumour-associated macrophages: Relation with progression and invasiveness, and assessment of M1/M2 macrophages in canine mammary tumours. The Veterinary Journal 2018, 234, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D. Mast cells and macrophages exert beneficial and detrimental effects on tumor progression and angiogenesis. Immunology letters 2013, 152, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfacteria, A.; Napoli, E.; Rifici, C.; Commisso, D.; Giambrone, G.; Mazzullo, G.; Marino, G. Immune cells and immunoglobulin expression in the mammary gland tumors of dog. Animals 2021, 11, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grutzkau, A.; Kruger-Krasagakes, S.; Baumeister, H.; Schwarz, C.; Kogel, H.; Welker, P.; Lippert, U.; Henz, B. M.; Moller, A. Synthesis, storage, and release of vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor (VEGF/VPF) by human mast cells: implications for the biological significance of VEGF206. Molecular biology of the cell 1998, 9, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larcher, F.; Murillas, R.; Bolontrade, M.; Conti, C. J.; Jorcano, J. L. VEGF/VPF overexpression in skin of transgenic mice induces angiogenesis, vascular hyperpermeability and accelerated tumor development. Oncogene 1998, 17, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunder, C. A.; St John, A. L.; Abraham, S. N. Mast cell modulation of the vascular and lymphatic endothelium. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2011, 118, 5383–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjunpää, H.; Llort Asens, M.; Guenther, C.; Fagerholm, S. C. Cell adhesion molecules and their roles and regulation in the immune and tumor microenvironment. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H. L.; Burbelo, P. D.; Yamada, Y.; Kleinman, H. K.; Metcalfe, D. Mast cells chemotax to laminin with enhancement after IgE-mediated activation. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 1989, 143, 4188–4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Flores-Borja, F.; Nassiri, S.; Miranda, E.; Lawler, K.; Grigoriadis, A.; Monypenny, J.; Gillet, C.; Owen, J.; Gordon, P. Integrin-mediated macrophage adhesion promotes lymphovascular dissemination in breast cancer. Cell reports 2019, 27, 1967–1978.e1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).