Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Citizen Science and Engagement

2.2. Gamification in Non-Game Contexts

2.3. Gamification in Citizen Science

2.4. Theoretical Foundations

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design

3.1.1. Participants and Setting

- Registered users. A total of 49 users created a GREENCROWD account, however just 40 participants completed a baseline socio-demographic survey (age bracket, gender identity, study major, employment status, digital-skills self-rating, perceived disadvantage, residence postcode). Most participants (38 out of 49; 77.55%) belonged to the 18–24 years age group, classified as young adults or university-age. Only two participants fell outside this group—one in the 25–34 range (early adulthood) and one in the 45–54 range (late adulthood), each representing 2.04% of the sample. Nine users (18.37%) did not declare their age range. The interquartile range (IQR = 20–24)—which represents the middle 50% of the participants’ age distribution—confirms that most respondents were in their early twenties, aligning with the university student demographic (Table 1). In terms of gender identity, 30 participants identified as male (75%) and 10 as female (25%), indicating a gender imbalance in the sample. Importantly, no significant differences were observed across groups regarding study major, employment status, digital-skills self-rating, perceived disadvantage, or residential location, supporting the demographic homogeneity of the analytical sample.

- Active contributors. 7 students (15% of registrants) submitted at least one complete task set during the study window; this subgroup constitutes the analytical sample for behavioural metrics.

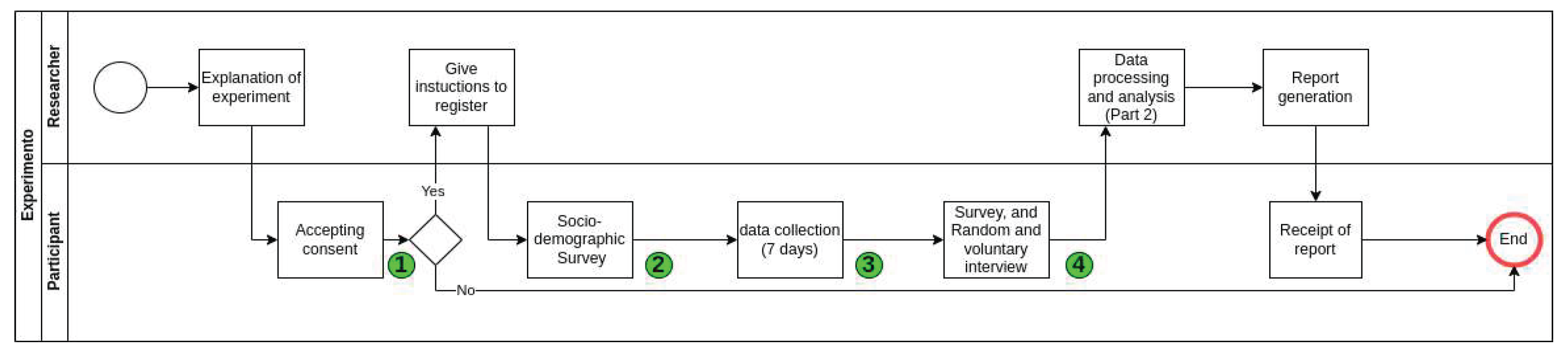

- Ethics. The protocol, depicted in Figure 1, was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Assessment Committee of the University of Deusto (Ref. ETK-61/24-25). In-app onboarding provided a study information sheet; participants gave explicit, GDPR-compliant e-consent and could withdraw at any point without penalty.

3.2. Intervention: The Gamified Experiment

3.2.1. Daily Task Structure

3.2.2. Micro-task Components

- Complete a site survey (environmental rating, issue identification, and site usage frequency).

- Upload a geo-tagged photograph reflecting current site conditions.

- Provide suggestions for site improvement and indicate willingness to participate in future student-led initiatives.

3.2.3. GREENCROWD

- Interactive Map with POIs and Dynamic Scoring: After login, the users can join to any available campaign in the system, then the user views a map overlaid with daily POIs, each associated with specific environmental observation tasks and points values (this depends on the gamification group that users belong to). These values are dynamically updated based on time, frequency, or contextual rules defined in the campaign logic (Figure 2)

- Modular Task Workflow: In this experiment the tasks were structured in a three-step format: (i) environmental perception ratings, (ii) geotagged photo uploads, and (iii) suggestion prompts and willingness-to-engage indicators. This modularity simplifies user experience and improves data completeness (Figure 3).

- Points, Leaderboard and Feedback Layer: After submitting a response, participants are shown the points earned for the completed task (Figure 4). Participants can monitor their own cumulative points and relative position on a public leaderboard. While users can see their own alias and ranking, other entries appear anonymized (e.g., “***123”), preserving participant confidentiality while still leveraging social comparison as a motivational driver (Figure 5).

- Device-Agnostic and Responsive Design: GREENCROWD is optimized for mobile devices, supporting real-time geolocation, camera integration, and responsive layouts, thereby reducing barriers to participation in field-based conditions.

3.2.4. Gamification Layer

- Random Group: Participants received a score generated by a stochastic function. If no previous point history existed, a random integer between 0 and 10 was assigned. If prior scores were available, a new score was randomly drawn from the range between the minimum and maximum historical values of previously assigned points. This approach simulates unpredictable reward schedules often found in game mechanics.

- Static Group: Similar to the Random group in its initial stage, a random value between 0 and 10 was assigned in the absence of historical data. However, once past scores existed, the participant’s reward was determined as the mean of the minimum and maximum previous values. This method introduces a fixed progression logic, providing more predictable feedback than random assignment, while still maintaining some variability.

-

Adaptive Group: This group received dynamically calculated scores based on five reward dimensions informed by user behavior and task context:

- ○

- Base Points (DIM_BP): Adjusted inversely according to the number of previous unique responses at the same Point of Interest (POI), to encourage spatial equity in data collection.

- ○

- Location-Based Equity (DIM_LBE): If a POI had fewer responses than the average across POIs, a bonus equivalent to 50% of base points was granted.

- ○

- Time Diversity (DIM_TD): A bonus or penalty based on participation at underrepresented time slots, encouraging temporal coverage. This was computed by comparing task submissions during the current time window versus others.

- ○

- Personal Performance (DIM_PP): Reflects the user’s behavioral rhythm. If a participant’s task submission interval improved relative to their own average, additional points were awarded.

- ○

- Streak Bonus (DIM_S): Rewards consistent daily participation using an exponential formula scaled by the number of consecutive participation days.

- Points: Awarded for each completed survey and photo submission. Participants could see their points both before and after each task.

- Leaderboard: A public, real-time leaderboard displayed cumulative points and fostered social comparison.

- Material prizes: In recognition of participation, eight material prizes (valued between €25–€30 each) were made available at the end of the study. These included LED desk lamps with wireless chargers, high-capacity USB 3.0 drives, wireless earbuds, and external battery packs (27,000mAh, 22.5W). The purpose of these rewards was to acknowledge and appreciate participants’ involvement, rather than to act as the primary incentive for participation. All prizes were communicated transparently to participants prior to the intervention, with an emphasis on their role as a token of appreciation rather than as competition drivers.

3.2.5. Technical Support and Compliance

3.2.6. Engagement Assessment

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Participant Profile: Demographics and Participation Rates

4.2. Quantitative Findings

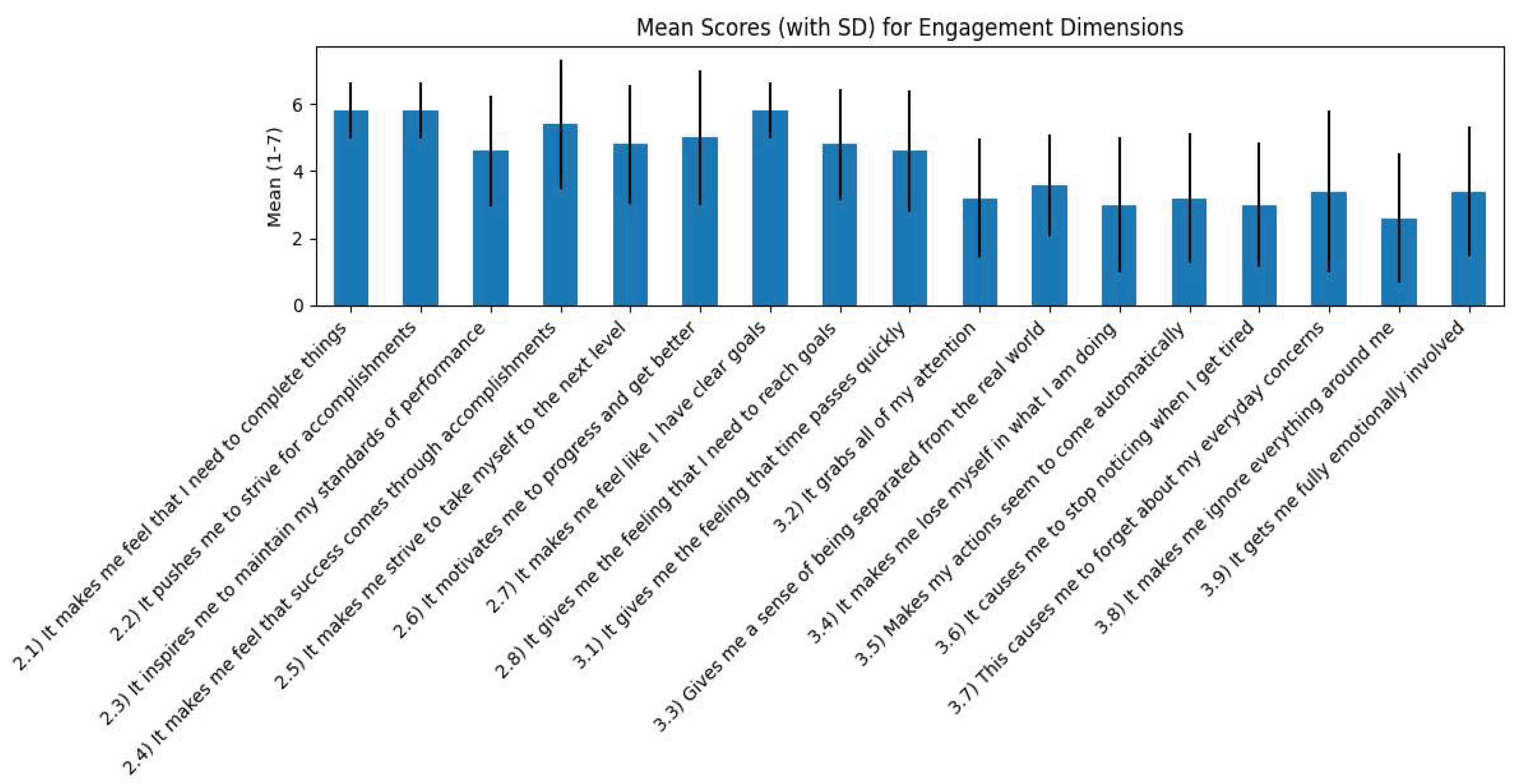

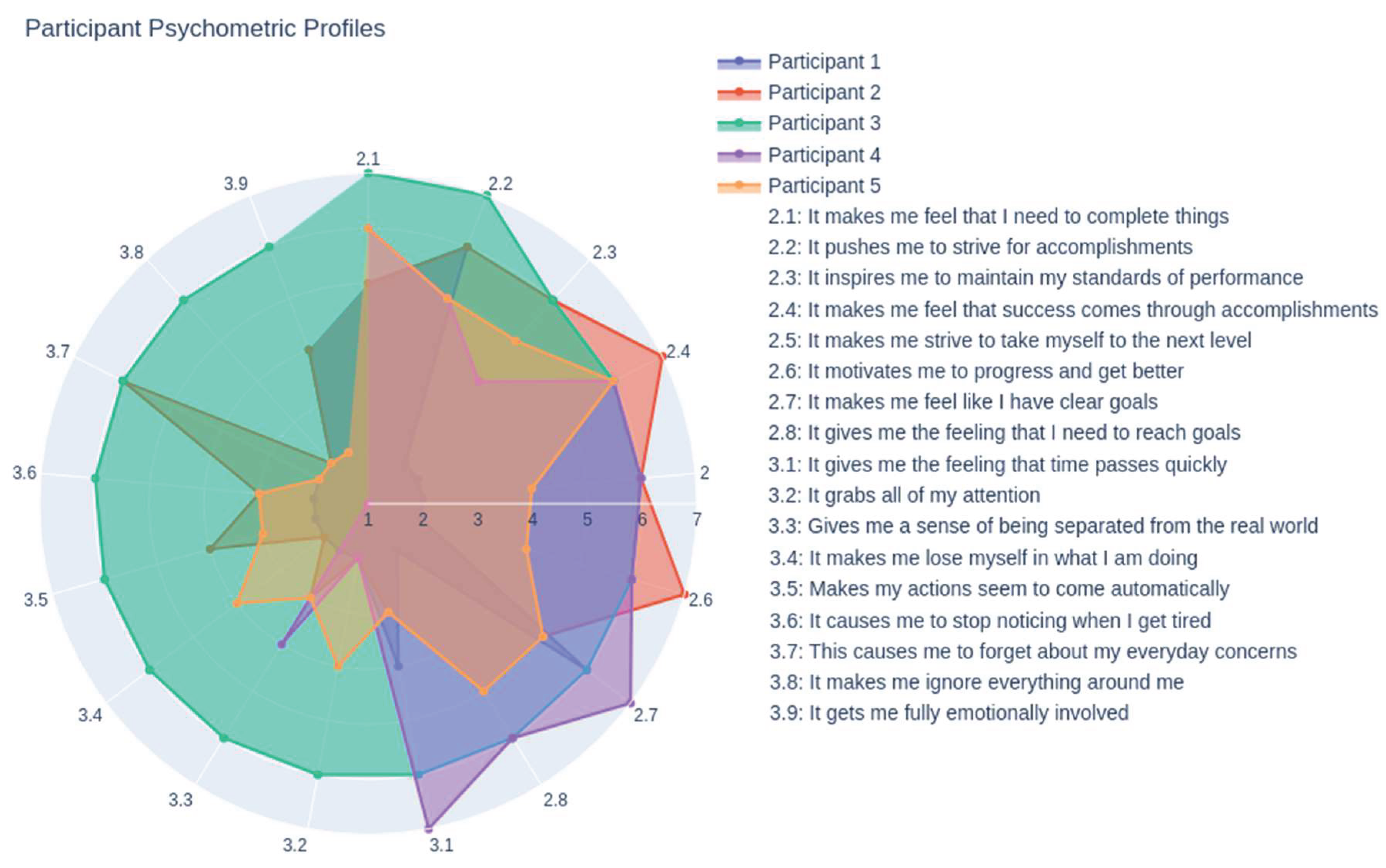

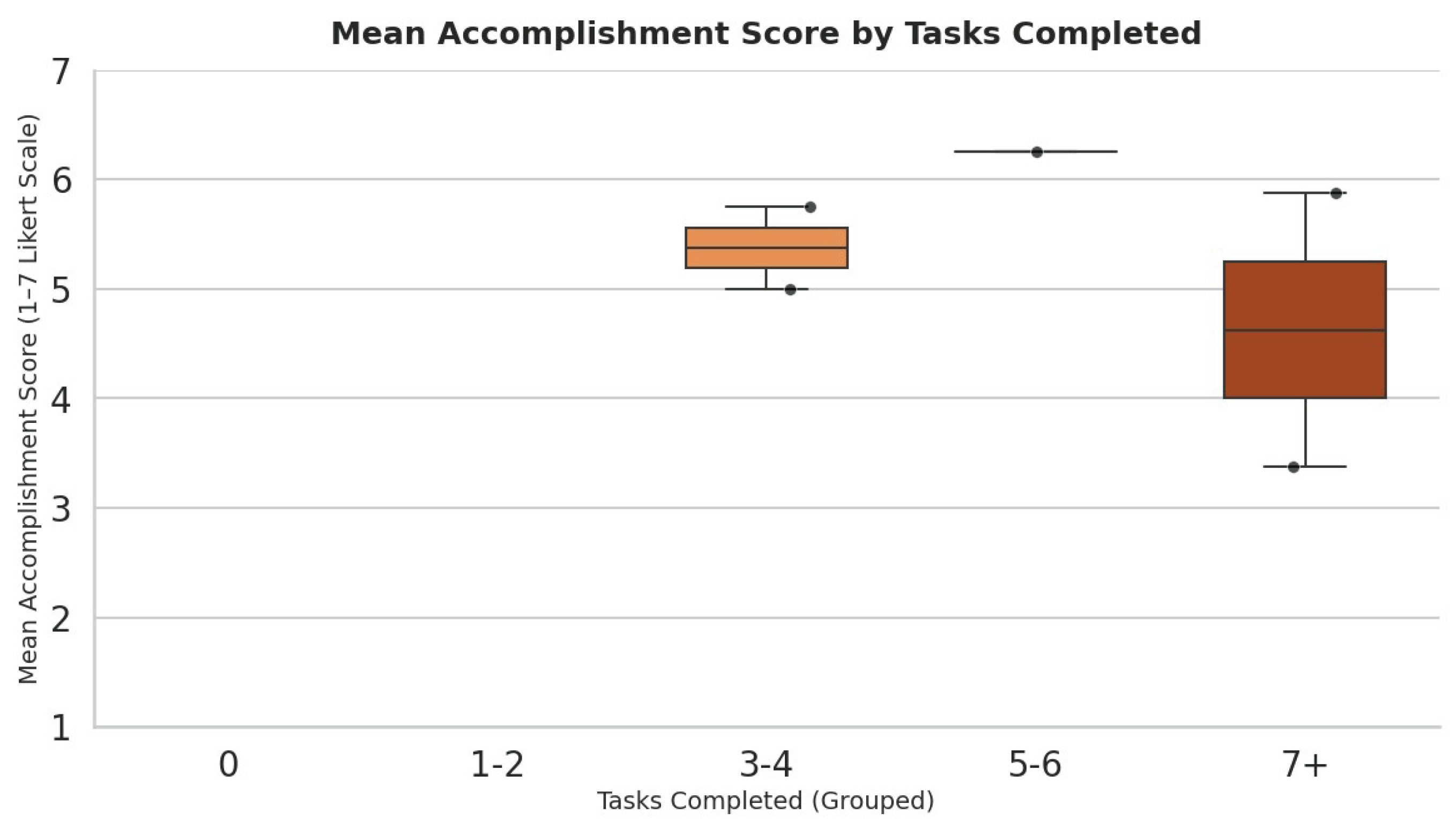

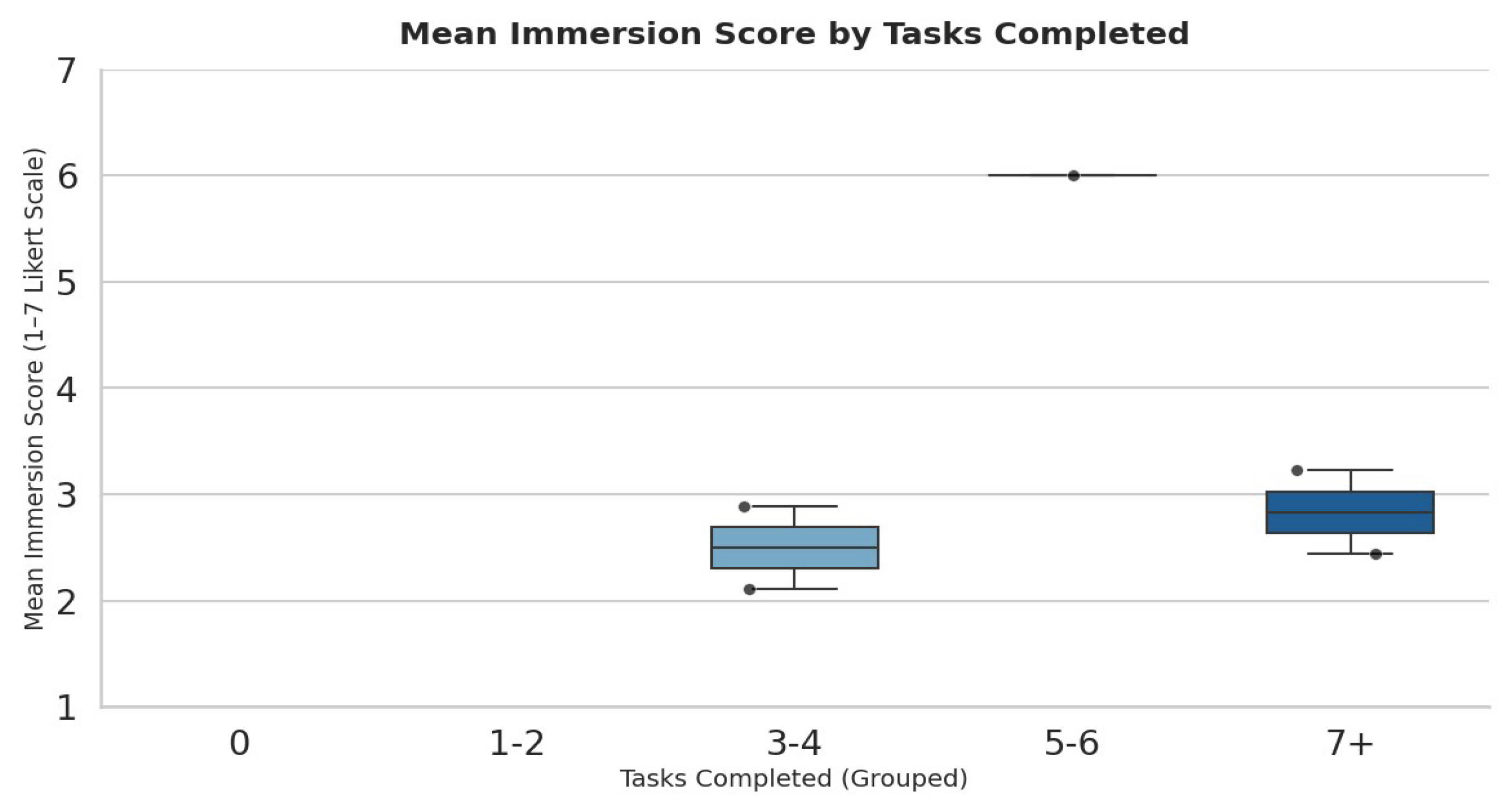

4.2.1. Distribution of Engagement, Accomplishment, and Immersion

4.2.2. Notable Individual Differences and Trends

4.2.3. Association Between Task Completion and Engagement

4.2.4. Data Visualizations

4.3. Qualitative Insights

4.3.1. Motivations for Participation

- Curiosity and Novelty: Several participants expressed initial curiosity about participating in a real-world experiment using a digital platform. One stated: “I wanted to see how it worked and if the platform would really motivate me to do the tasks.”

- Desire to Contribute: There was a recurrent theme of wanting to contribute to environmental improvement on campus: “It felt good to think our observations could help the university or city get better.”

- Appreciation for Recognition: Some cited the value of being recognized or rewarded, even if modestly: “I participated more because I knew there was a leaderboard and some prizes, but not only for that.”

4.3.2. Barriers and Constraints

- Time Management: All participants mentioned that balancing the experiment with their academic workload was a challenge: “Some days I just forgot or was too busy to go to the POIs.”

- Repetitiveness and Task Fatigue: A few noted the repetitive nature of tasks as a demotivating factor by the end of the week: “At first it was fun, but by day three it felt like doing the same thing.”

4.3.3. Perceptions of Gamification

- Leaderboard and Points: Most reported that seeing their position on the leaderboard was a motivator for continued participation, but only up to a point: “I liked checking if I was going up, but when I saw I couldn’t catch up, I just did it for myself.”

- Prizes as Acknowledgment: Participants did not view the material prizes as the main incentive, but as a positive gesture: “I would have done it anyway, but it was nice to have a little prize at the end.”

- Fairness and Engagement: Some voiced that the system was fair because everyone had the same opportunity each day but also suggested ways to make the game more dynamic, such as varying tasks or giving surprise bonuses.

4.3.4. Social and Emotional Aspects

- Sense of Community: In the interview with two participants, there was discussion of sharing experiences with classmates, even if there was no formal team component: “We talked about it in class, comparing our scores and photos.”

- Enjoyment and Frustration: While most described the experience as “fun” or “interesting,” minor frustrations included technical glitches and lack of immediate feedback after submissions.

4.4. Integration of Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Findings

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Methodological Reflections

5.4. Limitations

5.4. Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| VTAE | Volunteer Task Allocation Engine |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| POI | Point of Interest |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| PBL | Points, Badges and Leaderboards |

| GAMEFULQUEST | Gameful Experience Questionnaire (validated psychometric scale) |

| IQR | Interquartile Range (statistical measure) |

| M | Mean (statistical average) |

| SD | Standard Deviation (statistical measure) |

| RQ | Research Question |

| IAM | Identity and Access Management |

| QUAN | Quantitative (in mixed-methods research design) |

| QUAL | Qualitative (in mixed-methods research design) |

Appendix A. Assigned Task at Each Point of Interest

- Select All

- 🗑️ Litter and garbage

- 🚗 Air pollution or traffic congestion

- 🔊 Noise from vehicles or people

- 🌱 Lack of green areas or trees

- 💧 Water puddles, drains or flooding

- 🧱 Damaged infrastructure (e.g., benches, paths)

- ⚠️ Safety concerns

- ❌ None of the above

- None

- Other (describe)

- As part of

Appendix B. Experiment Protocol: Evaluation of Gamification Impact in GREENCROWD

- -

- Understand how reward mechanisms (base points, geolocation equity, time diversity, personal performance, and participation streaks) influence participant motivation.

- -

- Identify whether certain elements of the system may generate unintended effects (e.g., inequality in reward distribution or demotivation among specific participant profiles).

- -

- Improve the quality and fairness of the system prior to large-scale implementation.

- -

- A systematic analysis of participatory behaviour under different reward conditions.

- -

- Quantitative evidence on the effectiveness of the system’s design.

- -

- A scientific foundation for adjusting or scaling the gamification model, in alignment with principles of fair and inclusive participation.

- Voluntary participation: For real participants, explicit informed consent will be obtained as per the approved protocol.

- Privacy and anonymity: The experiment may utilize simulated or anonymized data. GREENCROWD does not collect email addresses, only a unique participant identifier. If real data is used, all approved safeguards (anonymization, pseudonymization, and restricted access) will be applied.

- Right to withdraw: Participants may withdraw at any time by referencing their unique ID, with all associated data deleted.

- Data scope: No additional sensitive data will be collected, and the original data processing purpose remains unchanged.

- Use of results: Results are solely for scientific evaluation and system improvement; there are no individual negative consequences.

- No adverse consequences: The gamification system does not impact access to external resources or services. Any modifications will be based on fairness and equity.

- Consent Form:

- b.

- Socio-Demographic Survey:

- c.

- Data Collection:

- d.

- Post-Experiment Engagement Survey:

- -

- It makes me feel that I need to complete things.

- -

- It pushes me to strive for accomplishments.

- -

- It inspires me to maintain my standards of performance.

- -

- It makes me feel that success comes through accomplishments.

- -

- It makes me strive to take myself to the next level.

- -

- It motivates me to progress and get better.

- -

- It makes me feel like I have clear goals.

- -

- It gives me the feeling that I need to reach goals.

- -

- It gives me the feeling that time passes quickly.

- -

- It grabs all of my attention.

- -

- Gives me a sense of being separated from the real world.

- -

- It makes me lose myself in what I am doing.

- -

- Makes my actions seem to come automatically.

- -

- It causes me to stop noticing when I get tired.

- -

- This causes me to forget about my everyday concerns.

- -

- It makes me ignore everything around me.

- -

- It gets me fully emotionally involved.

Appendix C. Post-Experiment Interview Protocol

- -

- Estimated Duration: 20–30 minutes

- -

- Format: Individual semi-structured interview

- -

- Type: Semi-structured (flexible follow-up based on participant answers)

- -

- Can you briefly describe your overall experience participating in the experiment?

- -

- Did you participate every day, only on some days, or sporadically? What influenced your level of participation?

- -

- Did you feel you had the freedom to decide when and how to participate? (Autonomy)

- -

- Did you feel that you improved or developed skills throughout the activity? (Competence)

- -

- Did you feel part of a community or connected with other participants? (Relatedness)

- -

- Do you recall the game elements used in the experiment (e.g., points, rewards, leaderboard)? What were your thoughts about them?

- -

- Did any of these game elements motivate you to participate more or engage more deeply? Which ones and why?

- -

- At any point, did you feel the game elements distracted you from the core purpose of the activity?

- -

- Would you have participated the same way without the gamified elements? Why or why not?

- -

- When completing tasks, was your main focus on doing them accurately or completing them quickly to gain rewards?

- -

- Did you feel you were competing against others or more against yourself? How did that affect your behavior?

- -

- Were there moments when you repeated tasks to improve your score or bonus? Why?

- -

- Would you describe the experience as enjoyable or fun? What made it so (or not)?

- -

- Were there moments that frustrated you or made you lose interest? What were they?

- -

- Did you feel recognized or appreciated for your contributions (e.g., through feedback, scores, or rankings)?

- -

- Would you like to see gamified approaches like this used in other projects or classes? Why or why not?

- -

- Would you change anything about the reward system or task design?

- -

- What would you improve to make the experience more meaningful or engaging?

- -

- Is there anything else you would like to share about your experience?

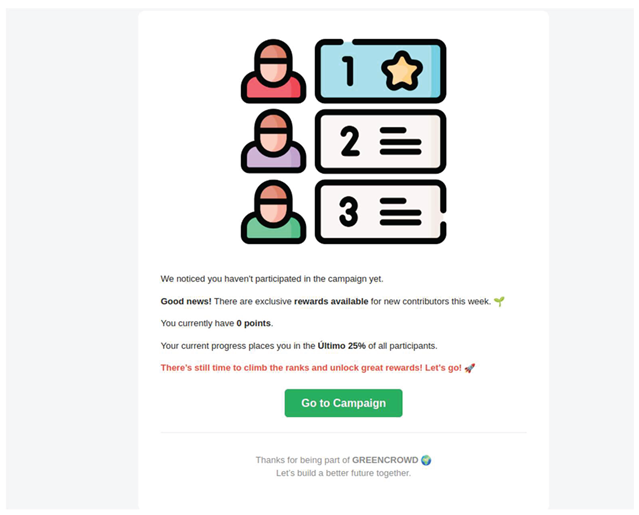

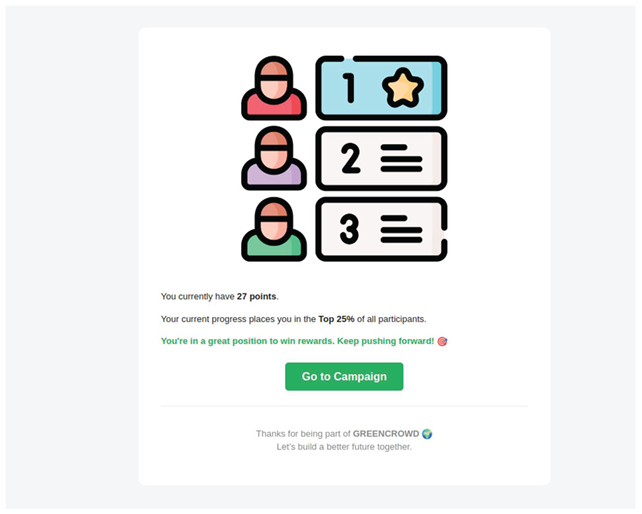

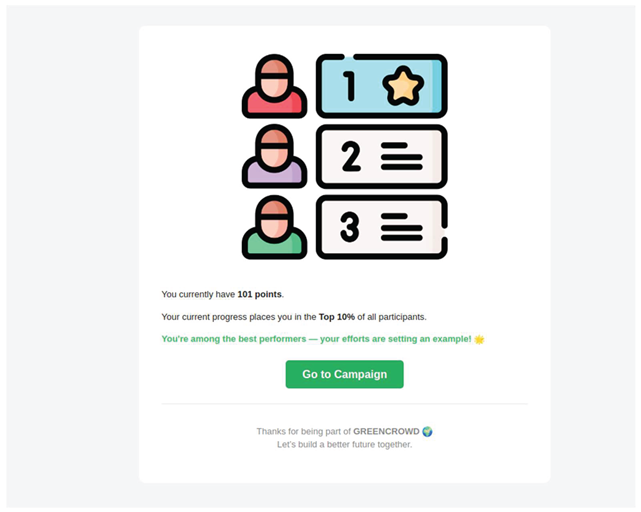

Appendix C. Example of Emails Sent to Participants During Campaign

References

- GREENGAGE - Engaging Citizens - Mobilizing Technology - Delivering the Green Deal | GREENGAGE Project | Fact Sheet | HORIZON. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101086530 (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Fraisl, D.; Hager, G.; Bedessem, B.; Gold, M.; Hsing, P.-Y.; Danielsen, F.; Hitchcock, C.B.; Hulbert, J.M.; Piera, J.; Spiers, H.; et al. Citizen Science in Environmental and Ecological Sciences. Nat. Rev. Methods Primer 2022, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappa, F.; Franco, S.; Rosso, F. Citizens and Cities: Leveraging Citizen Science and Big Data for Sustainable Urban Development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 648–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sherbinin, A.; Bowser, A.; Chuang, T.-R.; Cooper, C.; Danielsen, F.; Edmunds, R.; Elias, P.; Faustman, E.; Hultquist, C.; Mondardini, R.; et al. The Critical Importance of Citizen Science Data. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 650760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonney, R. Expanding the Impact of Citizen Science. BioScience 2021, 71, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengö, M.; Austin, B.J.; Danielsen, F.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á. Creating Synergies between Citizen Science and Indigenous and Local Knowledge. BioScience 2021, 71, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, M.J.O.; Hamlin, I.; Christelow, J.; Passmore, H.-A.; Richardson, M. The Benefits of Citizen Science and Nature-Noticing Activities for Well-Being, Nature Connectedness and pro-Nature Conservation Behaviours. People Nat. 2023, 5, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehn, U.; Gharesifard, M.; Ceccaroni, L.; Joyce, H.; Ajates, R.; Woods, S.; Bilbao, A.; Parkinson, S.; Gold, M.; Wheatland, J. Impact Assessment of Citizen Science: State of the Art and Guiding Principles for a Consolidated Approach. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1683–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citizen Science: Public Participation in Environmental Research. In Citizen Science; Cornell University Press, 2012; ISBN 978-0-8014-6395-2.

- Groom, Q.; Pernat, N.; Adriaens, T.; de Groot, M.; Jelaska, S.D.; Marčiulynienė, D.; Martinou, A.F.; Skuhrovec, J.; Tricarico, E.; Wit, E.C.; et al. Species Interactions: Next-Level Citizen Science. Ecography 2021, 44, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encarnação, J.; Teodósio, M.A.; Morais, P. Citizen Science and Biological Invasions: A Review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 8, 602980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, K.; Kobori, H. COVID-19 Pandemic Drives Changes in Participation in Citizen Science Project “City Nature Challenge” in Tokyo. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 255, 109001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelms, S.E.; Easman, E.; Anderson, N.; Berg, M.; Coates, S.; Crosby, A.; Eisfeld-Pierantonio, S.; Eyles, L.; Flux, T.; Gilford, E.; et al. The Role of Citizen Science in Addressing Plastic Pollution: Challenges and Opportunities. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 128, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, F.; Cudennec, C.; Abrate, T.; Allouch, C.; Annis, A.; Assumpção, T.; Aubert, A.H.; Bérod, D.; Braccini, A.M.; Buytaert, W.; et al. Citizens AND HYdrology (CANDHY): Conceptualizing a Transdisciplinary Framework for Citizen Science Addressing Hydrological Challenges. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2022, 67, 2534–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, M.J.O.; Adriaens, T.; Bertolino, S.; Eschen, R.; Essl, F.; Hulme, P.E.; Jeschke, J.M.; Roy, H.E.; Teixeira, H.; Groot, M. de Citizen Science Is a Vital Partnership for Invasive Alien Species Management and Research. iScience 2024, 27, 108623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinnen, K.R.R.; Jacobs, A.; Claus, K.; Ruyts, S.; Vercayie, D.; Lambrechts, J.; Herremans, M. ‘Animals under Wheels’: Wildlife Roadkill Data Collection by Citizen Scientists as a Part of Their Nature Recording Activities. Nat. Conserv. 2022, 47, 121–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Earnest, J.; Adam, M.; Clarke, R.; Yates, J.; Pennington, C.R. Careless Responding in Crowdsourced Alcohol Research: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Practices and Prevalence. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 30, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, J.M.; Hallett, R.A.; Roy, H.E.; Cleary, M. Citizen Science Can Enhance Strategies to Detect and Manage Invasive Forest Pests and Pathogens. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1113978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfian, M.; Ingensand, J.; Brovelli, M.A. The Partnership of Citizen Science and Machine Learning: Benefits, Risks, and Future Challenges for Engagement, Data Collection, and Data Quality. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, F.; Eicken, H.; Funder, M.; Johnson, N.; Lee, O.; Theilade, I.; Argyriou, D.; Burgess, N.D. Community Monitoring of Natural Resource Systems and the Environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 637–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, V. Motivation to Participate in an Online Citizen Science Game: A Study of Foldit. Sci. Commun. 2015, 37, 723–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinati, R.; Luczak-Roesch, M.; Simperl, E.; Hall, W. Because Science Is Awesome: Studying Participation in a Citizen Science Game. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Web Science; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Iacovides, I.; Jennett, C.; Cornish-Trestrail, C.; Cox, A.L. Do Games Attract or Sustain Engagement in Citizen Science? In A Study of Volunteer Motivations. In Proceedings of the CHI ’13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1101–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Bowser, A.; Hansen, D.; Preece, J.; He, Y.; Boston, C.; Hammock, J. Gamifying Citizen Science: A Study of Two User Groups. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the companion publication of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work & social computing; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Simperl, E.; Reeves, N.; Phethean, C.; Lynes, T.; Tinati, R. Is Virtual Citizen Science A Game? Trans Soc Comput 2018, 1, 6–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.A.; Gandhi, K.; Gander, A.; Cooper, S. A Survey of Citizen Science Gaming Experiences. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2022, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfine, M.; Muller, A.; Manners, R. Literature Review on Motivation and Incentives for Voluntary Participation in Citizen Science Projects. 2024.

- Martella, R.; Clementini, E.; Kray, C. Crowdsourcing Geographic Information with a Gamification Approach. Geod. Vestn. 2019, 63, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotov, M.J.N. Collecting Data for Indoor Mapping of the University of Münster Via a Location Based Game. M.S., Universidade NOVA de Lisboa (Portugal): Portugal, 2014.

- Vasiliades, M.A.; Hadjichambis, A.C.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D.; Adamou, A.; Georgiou, Y. A Systematic Literature Review on the Participation Aspects of Environmental and Nature-Based Citizen Science Initiatives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, D.; Fernández-Caballero, A.; Pereira, A.; Rocha, N.P. Smart City Applications to Promote Citizen Participation in City Management and Governance: A Systematic Review. Informatics 2022, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GREENGAGE | GREENGAGE Project.

- Puerta-Beldarrain, M.; Gómez-Carmona, O.; Chen, L.; López-de-Ipiña, D.; Casado-Mansilla, D.; Vergara-Borge, F. A Spatial Crowdsourcing Engine for Harmonizing Volunteers’ Needs and Tasks’ Completion Goals. Sensors 2024, 24, 8117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, J.; Mason-Wilkes, W. Dark Citizen Science. Public Underst. Sci. 2024, 33, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffler, S.; Barbiéri, C.; Ghilardi-Lopes, N.P.; Leocadio, J.N.; Albertini, B.; Francoy, T.M.; Saraiva, A.M. A Buzz for Sustainability and Conservation: The Growing Potential of Citizen Science Studies on Bees. Sustainability 2021, 13, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinbrot, X.A.; Jones, K.W.; Newman, G.; Ramos-Escobedo, M. Why Citizen Scientists Volunteer: The Influence of Motivations, Barriers, and Perceived Project Relevancy on Volunteer Participation and Retention from a Novel Experiment. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2023, 66, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, M.; O’Hare, G.; Ties, S.; Williams, J. The Citizen Observatory: Enabling Next Generation Citizen Science. Bus. Syst. Res. J. 2022, 12, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, R.; Manesh, M.F.; Sorrentino, M. Mapping the State of the Art to Envision the Future of Large-Scale Citizen Science Projects: An Interpretive Review. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.; Fegert, J.D.; Wittmer, A.; Weinhardt, C. Digital Participation for Data Literate Citizens – A Qualitative Analysis of the Design of Multi-Project Citizen Science Platforms. IADIS Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2023, 18, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wehn, U.; Bilbao Erezkano, A.; Somerwill, L.; Linders, T.; Maso, J.; Parkinson, S.; Semasingha, C.; Woods, S. Past and Present Marine Citizen Science around the Globe: A Cumulative Inventory of Initiatives and Data Produced. Ambio 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.K.R.; Simone, A.; Mazzonetto, M. RRI Legacies: Co-Creation for Responsible, Equitable and Fair Innovation in Horizon Europe. J. RESPONSIBLE Innov. 2021, 8, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, T.B.; Ballard, H.L.; Lewenstein, B.V.; Bonney, R. Engagement in Science through Citizen Science: Moving beyond Data Collection. Sci. Educ. 2019, 103, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, J.; Hamari, J. The Rise of Motivational Information Systems: A Review of Gamification Research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L.V. Distribution Theory for Glass’s Estimator of Effect Size and Related Estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 1981, 6, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M.; Homner, L. The Gamification of Learning: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 32, 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristeidou, M.; Herodotou, C.; Ballard, H.L.; Higgins, L.; Johnson, R.F.; Miller, A.E.; Young, A.N.; Robinson, L.D. How Do Young Community and Citizen Science Volunteers Support Scientific Research on Biodiversity? The Case of iNaturalist. Diversity 2021, 13, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najwer, A.; Jankowski, P.; Niesterowicz, J.; Zwoliński, Z. Geodiversity Assessment with Global and Local Spatial Multicriteria Analysis. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2022, 107, 102665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Hollstein, L.; Aguilar, L.; Dwyer, J.; Auffrey, C. Youth Engagement in Water Quality Monitoring: Uncovering Ecosystem Benefits and Challenges. Architecture 2024, 4, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GitHub - Fvergaracl/Greencrowd. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20250309214115/https://github.com/fvergaracl/greencrowd (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Vergara Borge, F. Fvergaracl/GAME 2024.

- Högberg, J.; Hamari, J.; Wästlund, E. Gameful Experience Questionnaire (GAMEFULQUEST): An Instrument for Measuring the Perceived Gamefulness of System Use. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2019, 29, 619–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; and Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Deterding, S.; Kuhn, K.-A.; Staneva, A.; Stoyanov, S.; Hides, L. Gamification for Health and Wellbeing: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Internet Interv. 2016, 6, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age Range (Years) | Description | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | Young adults, university-age | 38 | 77,55 % |

| 25–34 | Early adulthood | 1 | 2,04 % |

| 35–44 | Mid-adulthood | 0 | 0 % |

| 45–54 | Late adulthood | 1 | 2,04 % |

| 55–64 | Pre-retirement or early senior years | 0 | 0 % |

| 65–74 | Early retirement | 0 | 0 % |

| 75–84 | Senior adults | 0 | 0 % |

| Over 85 | Elderly/advanced age | 0 | 0 % |

| No declared | No age range provided | 9 | 18,37 % |

| Total | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).