The RDSF algorithm can be used for investigating and analyzing a wide range of mathematical and engineering problems. In practical problems, sufficient information is often available to analyze the issue effectively. In such cases, the information can be classified, and the objective function’s value can be calculated based on various parameter values to construct the M-space. However, for theoretically posed problems, it is often necessary to use computational methods to generate data randomly. This generated data is then used to compute the objective function’s value and create the M-space.

3.1. Analysis and Review of Partial Differential Equations (PDEs)

One of the most significant applications of the RDSF algorithm explored in this article is the investigation of the solvability of partial differential equations (PDEs). PDEs are one of the most important mathematical problems that are widely used in various technical and engineering fields. Finding exact or approximate solutions to these equations is crucial, as deriving a general solution is often impossible and typically requires case-by-case analysis.

In this study, we initially examined various PDEs intuitively by employing diverse functions and generating random data computationally using the RDSF algorithm. Through the analysis of these mathematical functions, we identified potential solutions to specific PDEs with the desired level of approximation. This approach enabled us to derive a general solution framework.

To achieve this, we introduce the necessary concepts and present a theorem. Subsequently, we demonstrate how the RDSF algorithm, in conjunction with this theorem, can be utilized to obtain approximate solutions with the desired accuracy for any given PDE.

Definition 1. We call the n-variable real-valued function FADF if the function is finite and all its derivatives of any order are also finite with respect to each of its variables.

Example 1. The and functions are FADF by definition.

Theorem 1. For any arbitrary partial differential equation (PDE) with coefficients that are finite within the domain of its independent variables, and all its derivatives exist, there exists at least one real-valued function f of the FADF type and a dependent constant ε, such that within the domain of the independent variables, this function brings the equation to an acceptable value close to zero.

Proof. We consider an arbitrary equation of the form

, where

represents the set of independent variables, and

U is the dependent variable. Furthermore, we express the desired equation

in its general form as:

We consider the FADF function

and

within the domain of definition of the equation, where

k represents the degree of the equation. By substituting

into the equation, we obtain:

where

is a function with maximum powers up to order

k.

By considering the properties of the FADF function in the domain of defining the independent variables of the equation, there is a constant value

such that:

According to the assumption of the theorem, within the domain of the independent variables of the equation, the coefficients of the PDE equation are finite. Thus, the constant value can be chosen such that the PDE equation is sufficiently close to zero, and based on the acceptable value of the distance of the PDE from zero, the value of the constant can be estimated.

Consequently, there exists a real-valued function of the FADF type:

which reduces the equation sufficiently close to zero. This function can be considered an approximate solution to the equation, depending on the specific conditions of the equation. □

Corollary 1. According to the proof, it is practically impossible to calculate the exact value of the constant ε within the domain of the independent variables due to the high dimensionality of the problem. As a result, we are left with an equation involving several variables, which cannot be solved accurately. Therefore, by using the RDSF algorithm and generating random values, we can determine an appropriate value for ε within a limited tolerance.

Example 2.

We consider the following heat equation:

where is the temperature at position and time t [11].

To check the solvability of the above equation, we consider the following FADF function:

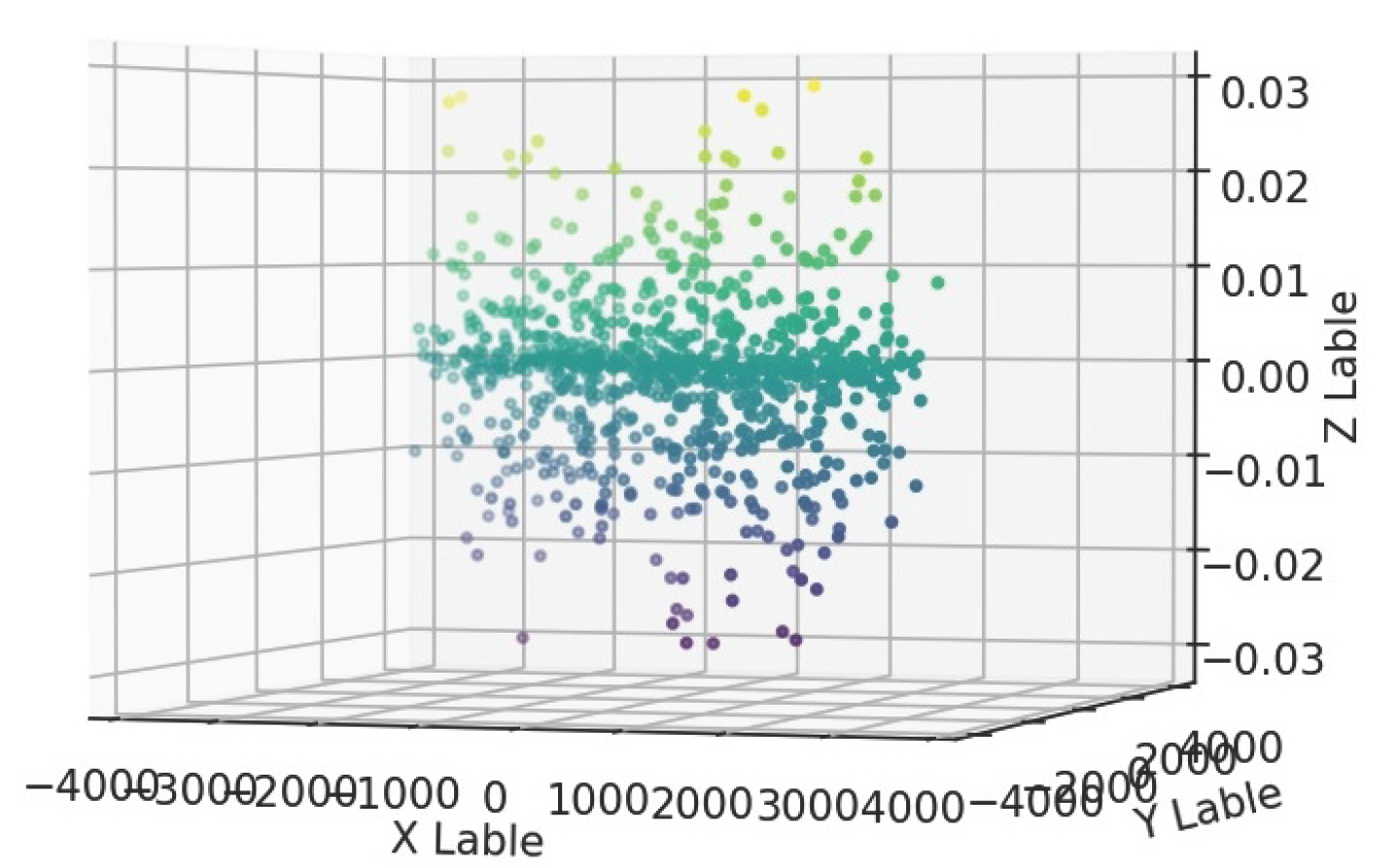

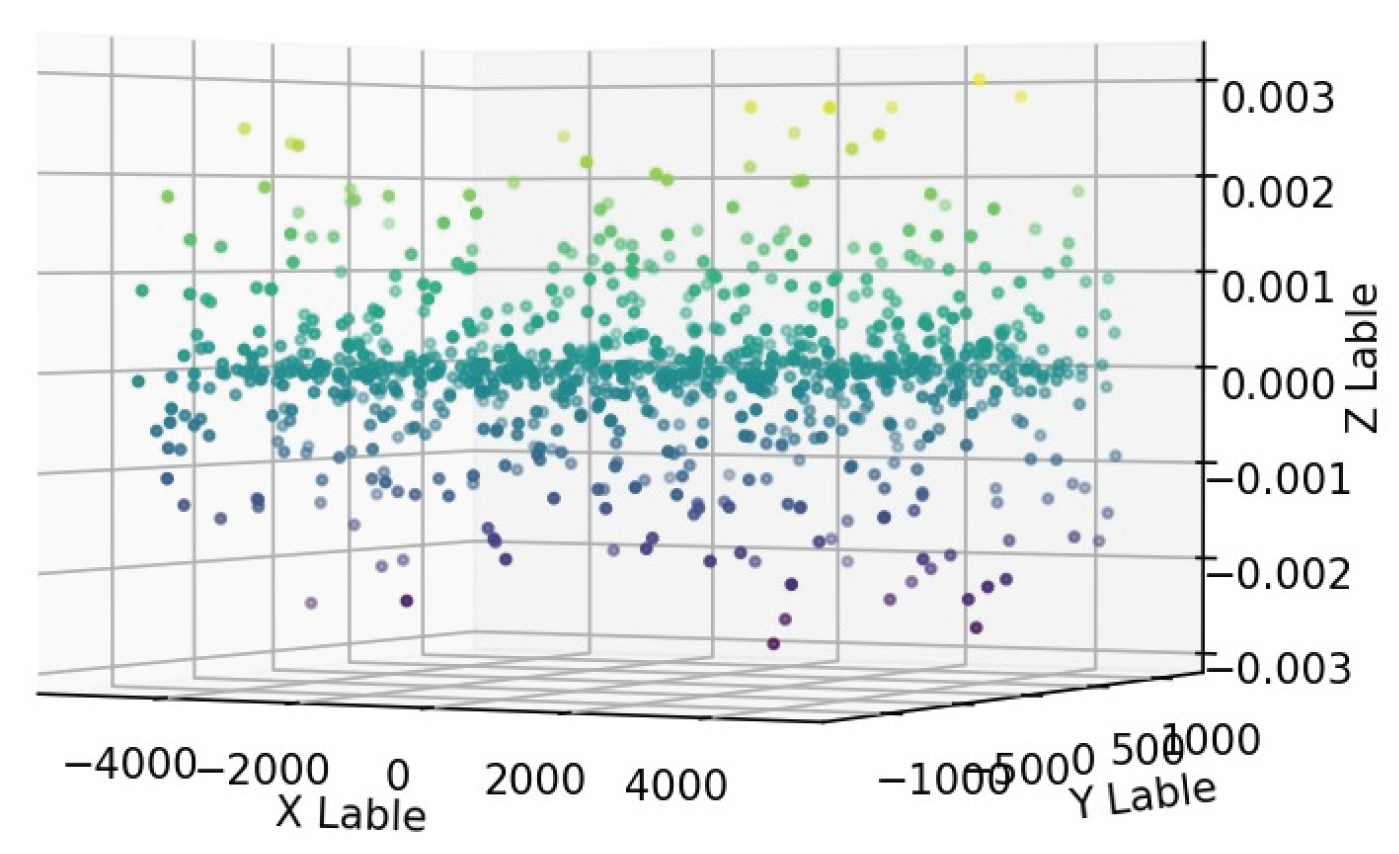

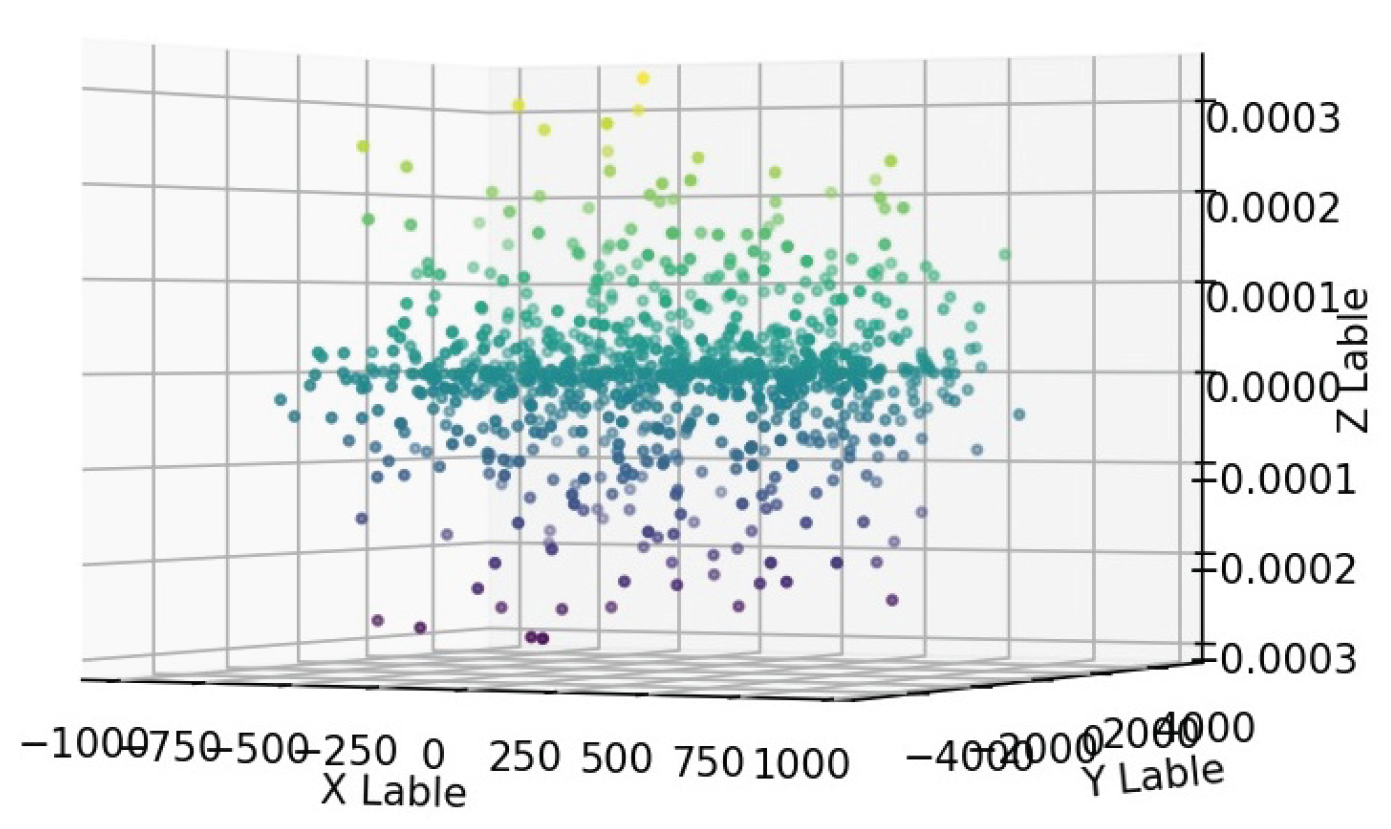

With a dependent constant value (see Figure 1), which serves as the initial value for the dependent constant of this function, we substitute the function into the equation. Based on the RDSF algorithm and using a computer, random values for the independent variables are generated. We then evaluate the deviation from the zero objective function by plotting a three-dimensional graph. This process is repeated until an appropriate value for the dependent constant ε is obtained, based on the acceptable error margin in the calculations. After performing calculations for 500 random points, the results are presented in the form of the following graph:

According to the diagram, the dispersion of the target function in the interval is greater than at other points. To find a more suitable solution, we re-evaluate the initial constant value using values smaller than the original, such as (see Figure 2) and (see Figure 3), and analyze the resulting graphs.

Based on the obtained graphs and the analysis of the dispersion of the objective function values, the best estimate for the dependent constant is .

Therefore, according to the acceptable approximation, the function:

is the most suitable option among the evaluated values for solving the PDE equation in this example.

3.2. Analysis and Investigation of the Dispersion of Prime Numbers

Finding prime numbers is one of the most fascinating topics in mathematics [

12]. In this section, we employ the RDSF algorithm to study the distribution of prime numbers. Since any non-prime natural number can be expressed as a product of the numbers 1 through 9, we construct the

n-dimensional spaces (

M) required by the RDSF algorithm. These spaces consist of

n-dimensional points that include the values 1 to 9. The largest number in this space is represented in the form:

For each number generated by multiplying the members of the n-dimensional space (), we define the value of the objective function at that point in the M-space as the number of times we add one to the resulting number to reach the first prime number. We then construct the n-dimensional space required by the RDSF algorithm and plot the final 3-dimensional diagrams for the 3-, 4-, and 5-dimensional spaces as examples.

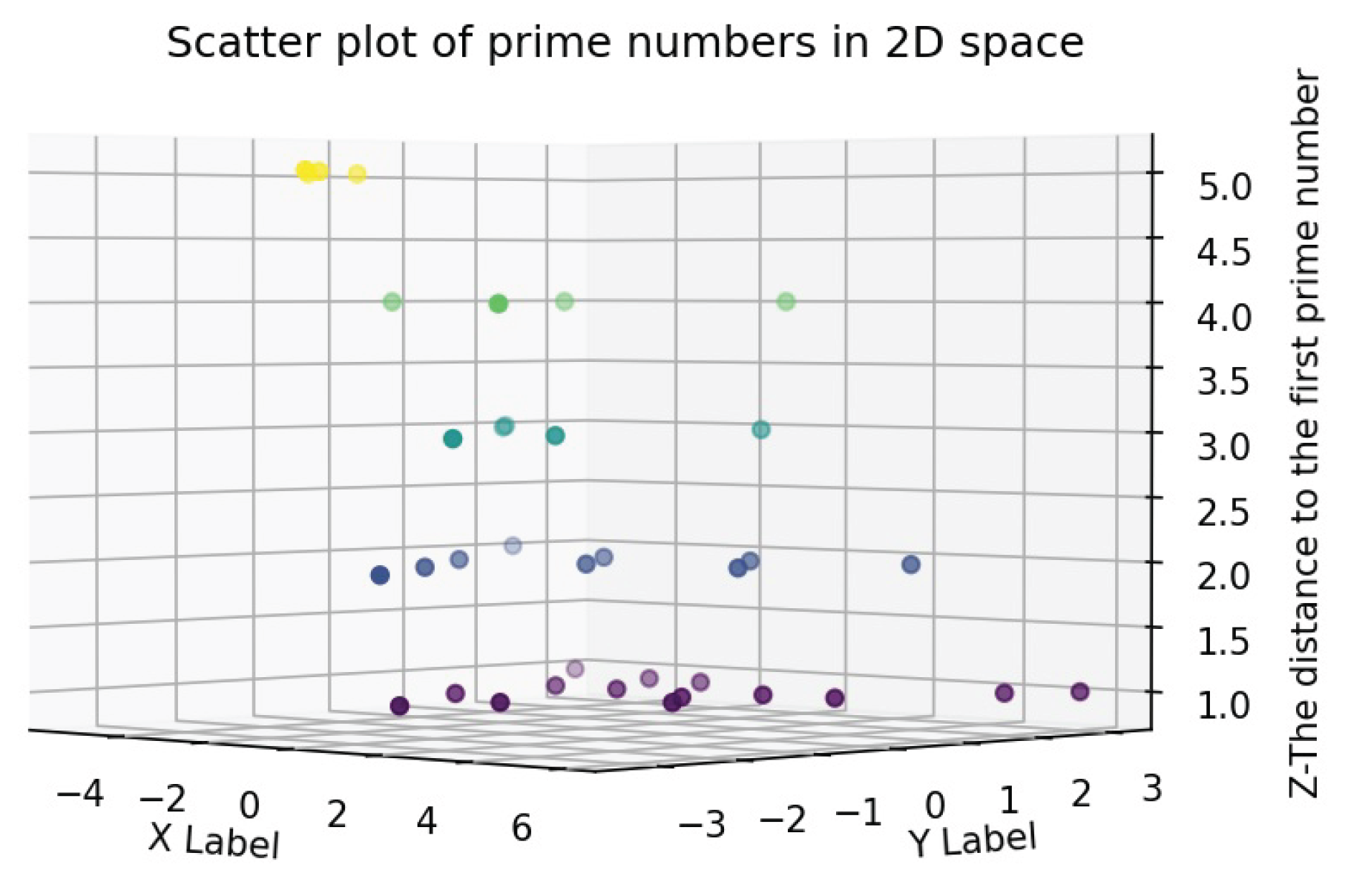

In the two-dimensional space (see

Figure 4), for the parameter of the first number after each product of the members of the space, the values 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 are obtained with scattering counts of 14, 9, 5, 4, and 4, respectively. The highest concentration occurs at points with distances of 1 and 2, and the dispersion decreases for higher values.

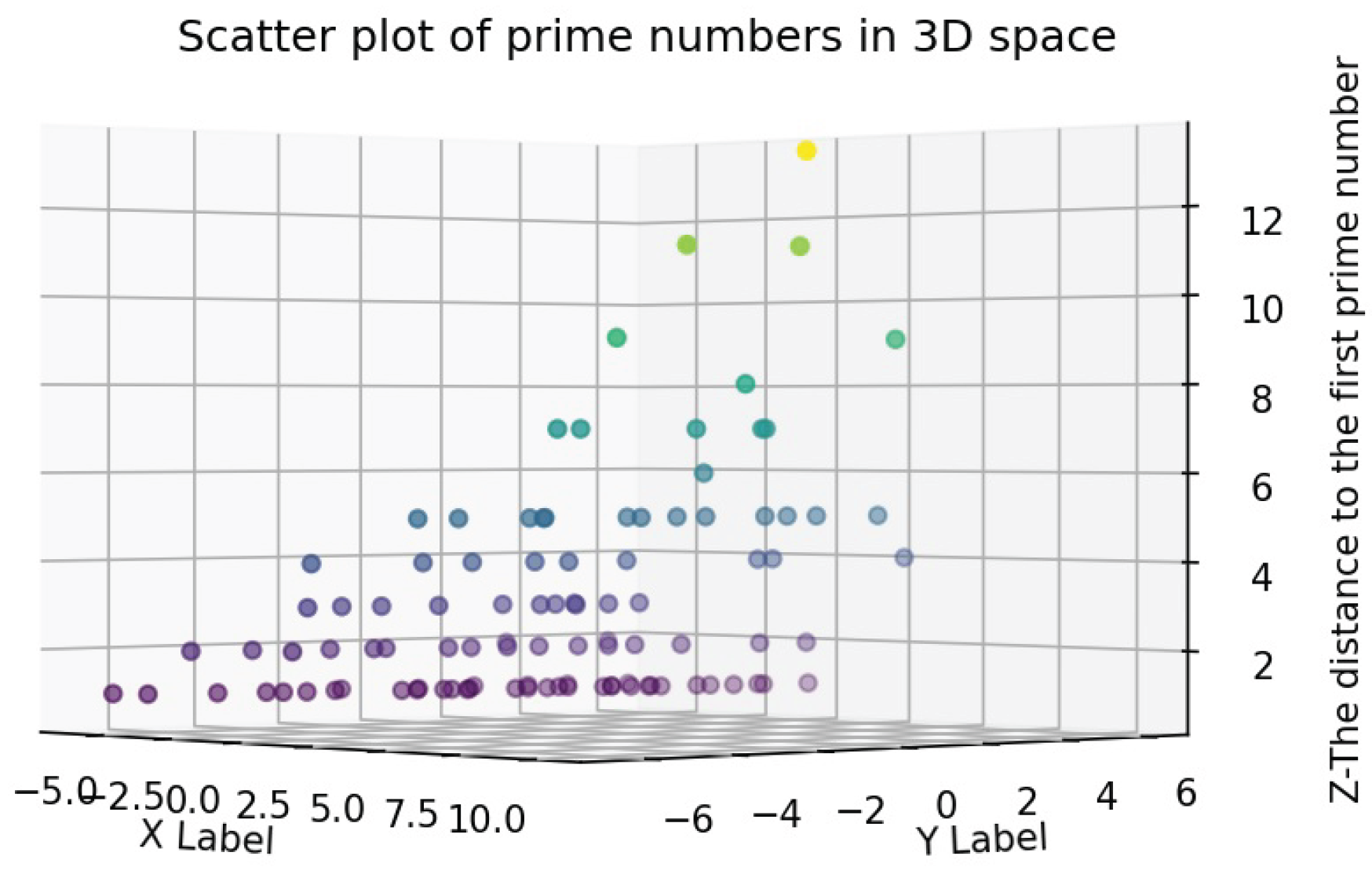

In the three-dimensional space (see

Figure 5), for the parameter of the first number after each product of the members of the space, the values 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, and 13 are obtained, with scattering counts of 37, 18, 11, 9, 13, 1, 5, 1, 2, 2, and 1, respectively. The highest concentration occurs at points with distances of 1 to 5, and the dispersion decreases for higher values.

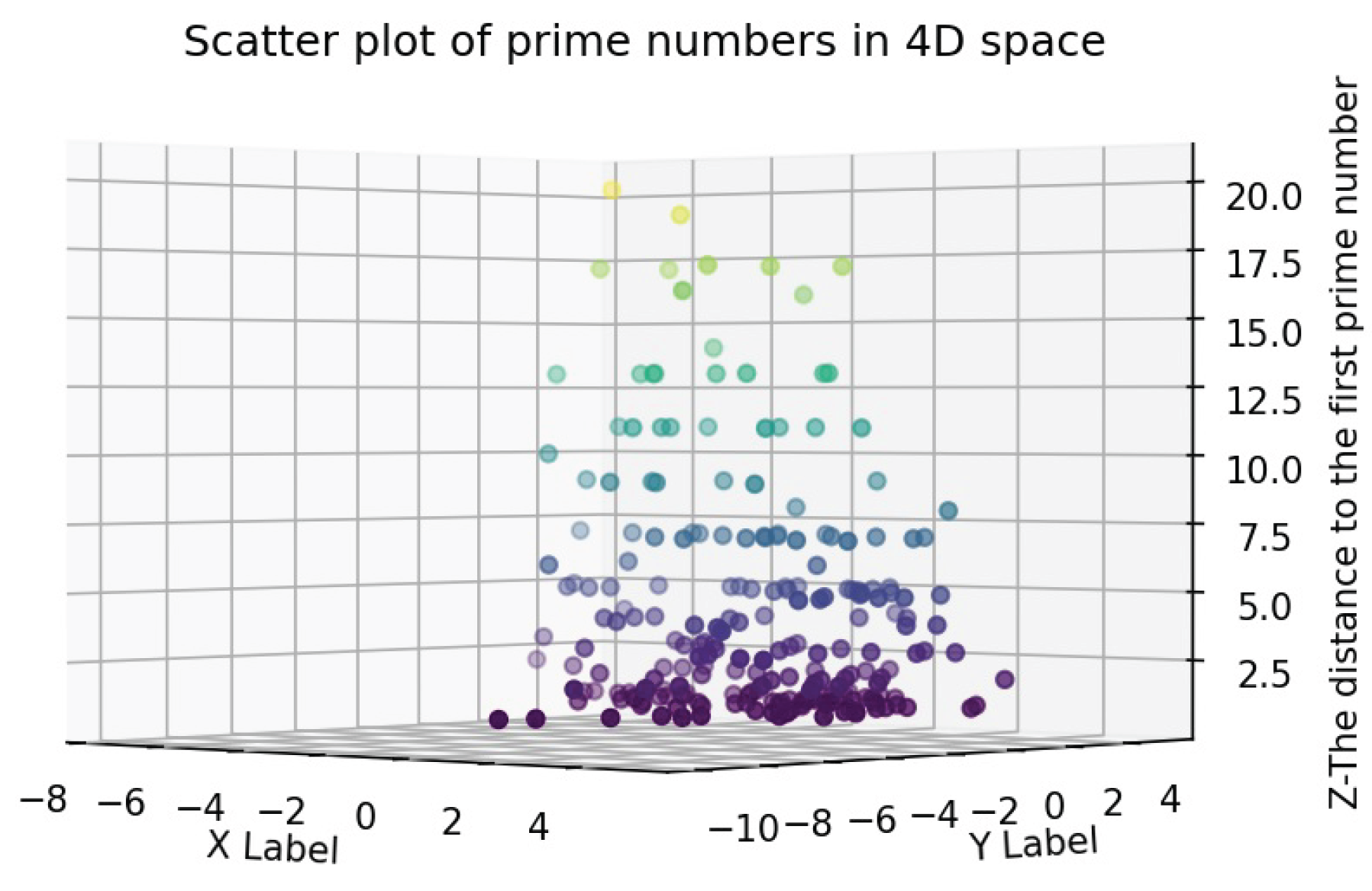

In the four-dimensional space (see

Figure 6), for the parameter of the first number after each product of the members of the space, the values 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 19, and 20 are obtained, with scattering counts of 75, 28, 21, 16, 26, 3, 19, 2, 7, 1, 9, 8, 1, 2, 5, 1, and 1, respectively. The highest concentration occurs at points with distances of 1 to 7, and the dispersion decreases for higher values. Additionally, points with a distance of 10, which were not observed in the three-dimensional space, appear in this space.

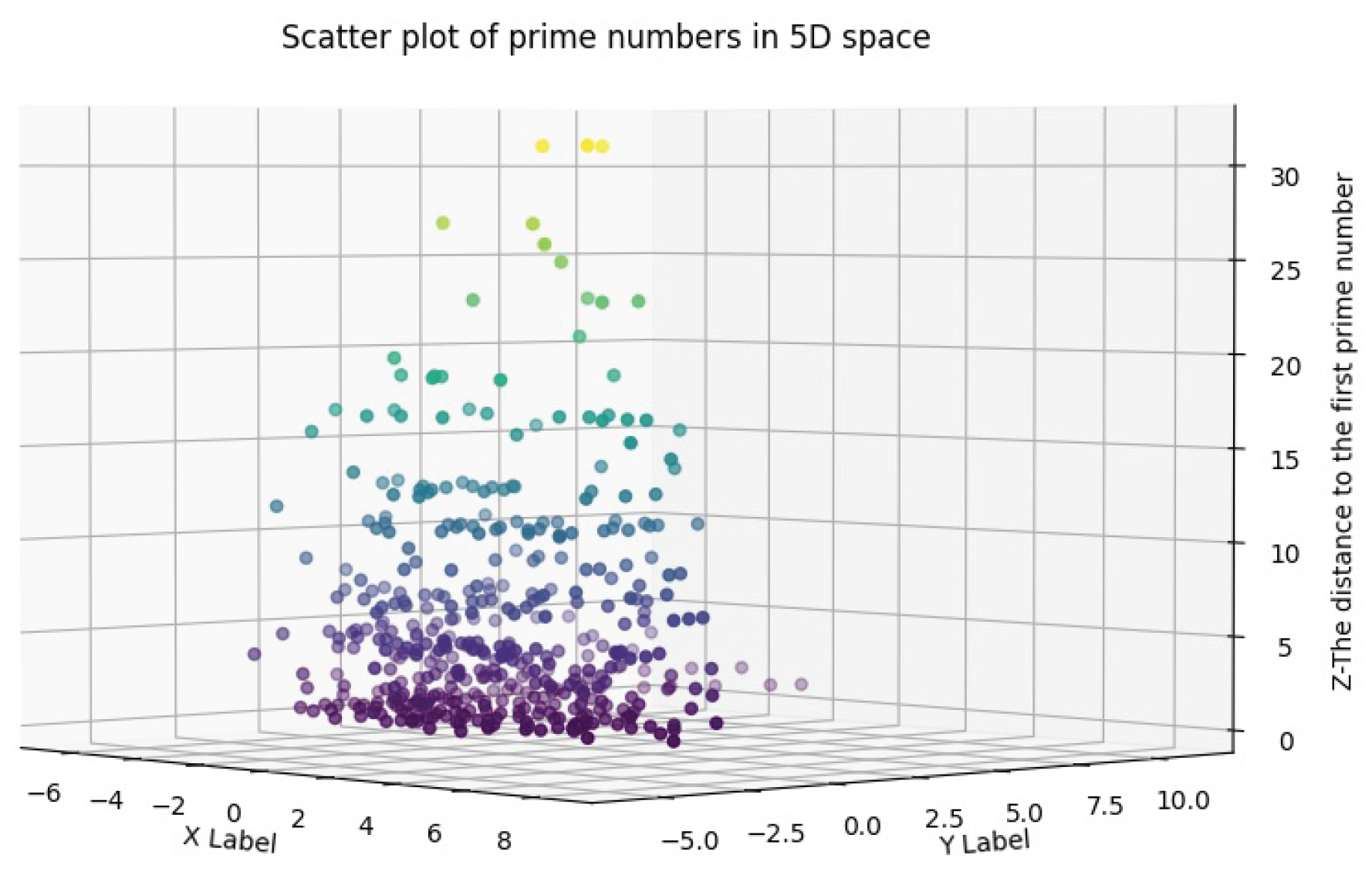

In the five-dimensional space (see

Figure 7), for the parameter of the first number after each product of the members of the space, the values 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 23, 25, 26, 27, and 31 are obtained, with scattering counts of 127, 39, 39, 25, 50, 5, 38, 9, 15, 1, 31, 1, 20, 3, 1, 5, 13, 6, 1, 1, 4, 1, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The highest concentration occurs at points with distances of 1 to 13, and the dispersion decreases for higher values. Additionally, points with distances of 12 and 15, which were not observed in the four-dimensional space, appear in this space.

In this application of the RDSF algorithm, by analyzing the results, the following conclusion can be drawn:

Corollary 2.

If represent an arbitrary m-dimensional space, then based on the degree of dispersion, the probability that the natural number:

is a prime number is higher for values of t between 1 and the dimension of the space (m), and lower for values greater than m.

3.3. Analysis and Investigation of the Behavior of Multivariate Arbitrary Real-Valued Functions

Assuming is a real-valued function of an arbitrary variable, we can use the RDSF algorithm to analyze the behavior of this function around a specific value. Using Python software, we select random values for the variables within their domain to form the M-space. Notably, the more points we generate, the more accurate the analysis becomes with the help of the RDSF algorithm.

Following the algorithm’s steps, we calculate the function for the set of randomly generated points. In the next step, we apply the MDS method to map these points into a 2-dimensional space while preserving their pairwise distances. Then, we add the value of the function at each n-dimensional point to create a 3-dimensional space. By plotting the 3-dimensional graph and observing the proximity of the dimension related to the function’s value, we can analyze the behavior of the function near the desired point.

Example 3.

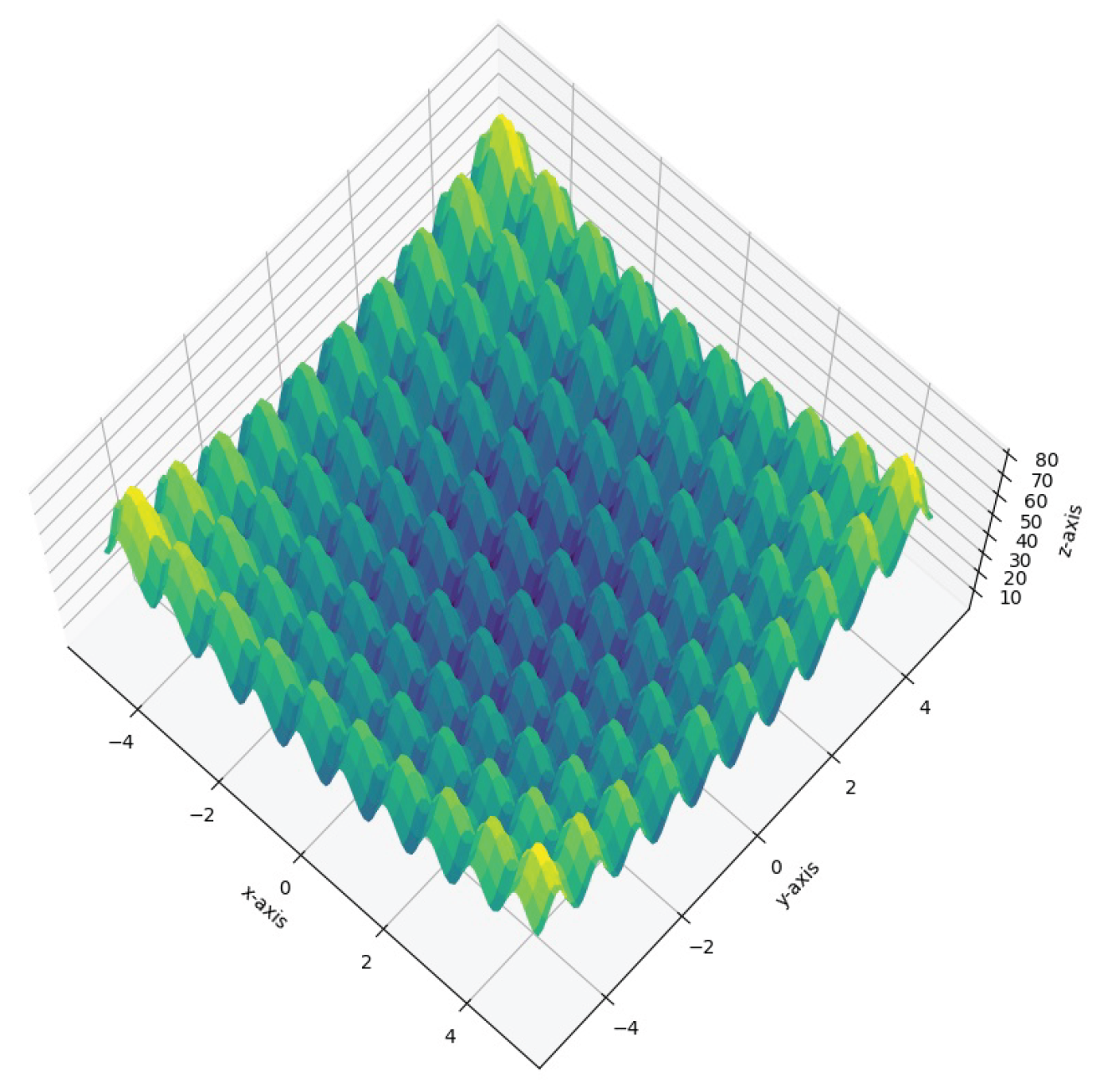

The Rastrigin function is one of the most well-known test functions in the field of multivariate optimization and evolutionary algorithms. Finding the minimum of this function is a relatively challenging task due to its extensive search space and the large number of local minima [13].

where:

is the input vector of dimension n.

A is a constant, typically set to 10.

n is the number of dimensions.

In the two-variable case (see Figure 8), the behavior of this function can be examined and visualized in a three-dimensional space, where the large number of local minima within a limited range is clearly observable.

In the three-variable case, since it is not possible to plot a four-dimensional space, one variable is typically held constant, and the remaining two variables along with the function value are analyzed in a three-dimensional space. By employing the RDSF algorithm and reducing the dimensions of the four-dimensional space, the behavior of the function can be intuitively examined in a three-dimensional space without assuming any variable to be constant, based on the behavior of all variables.

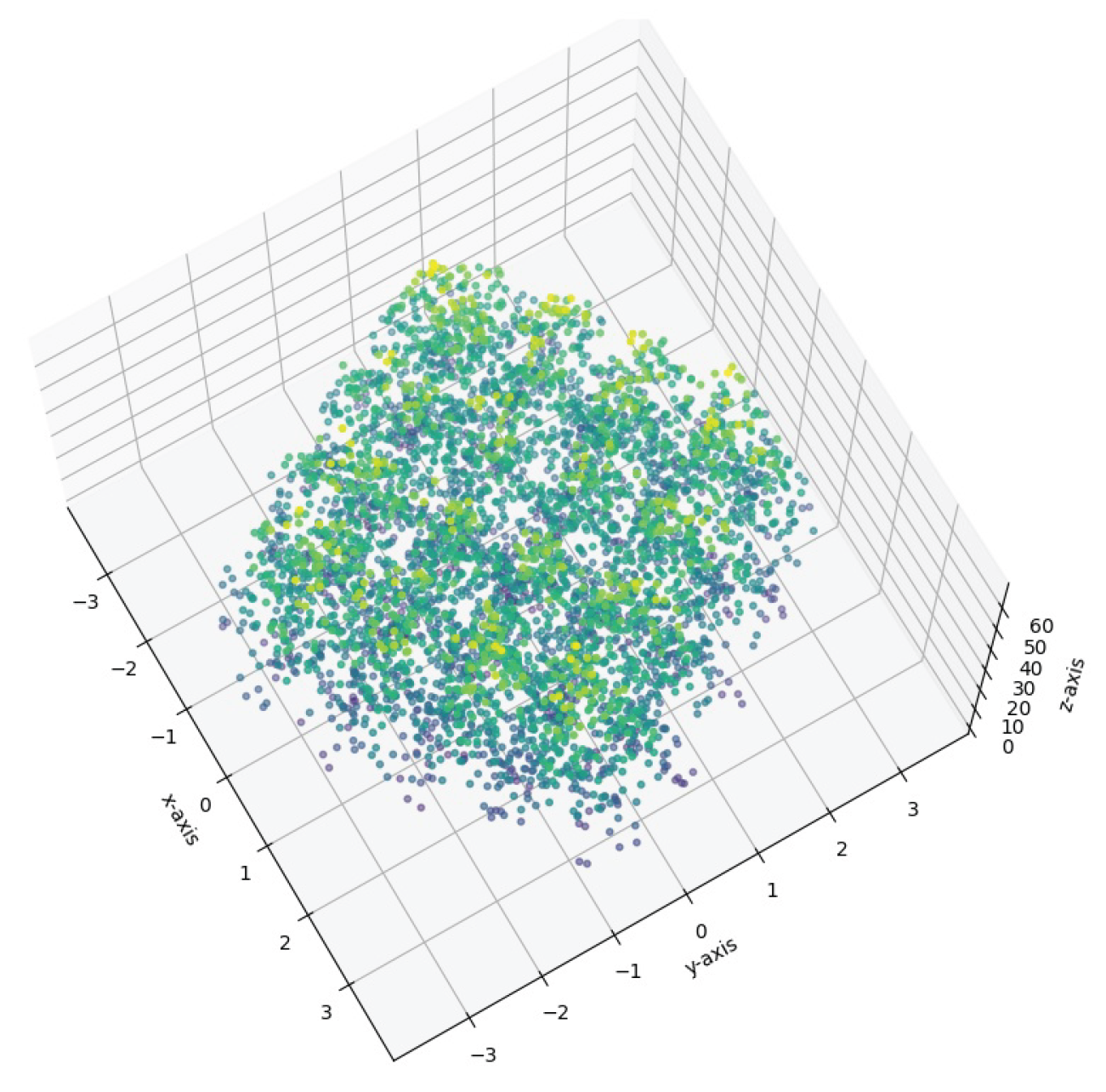

First, in the smaller range , using a computer and following the steps of the RDSF algorithm, random data is generated within this range, and the corresponding graph is obtained (see Figure 9). As can be observed, similar to the two-variable case, there are numerous local minima within this small range.

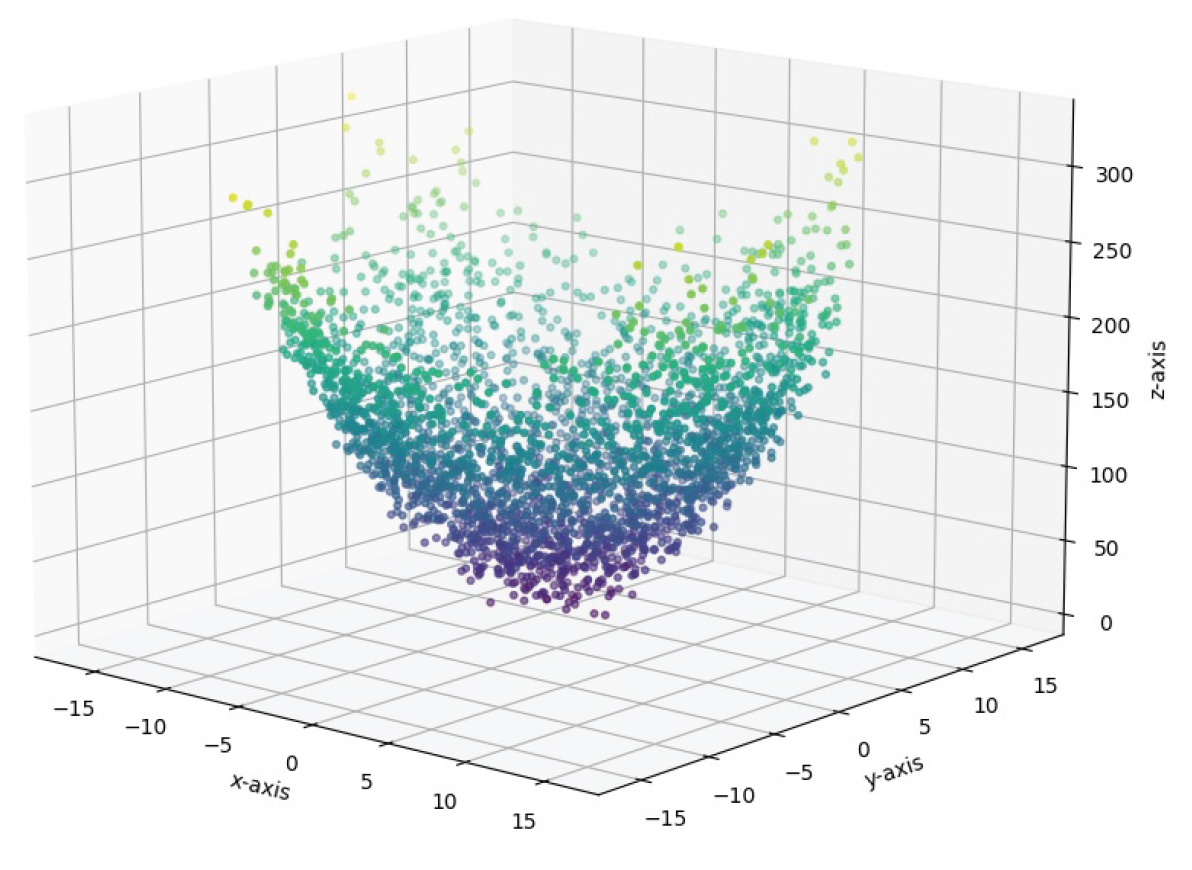

Next, in the larger range , using the RDSF algorithm and a computer, data is generated, and the observable space is obtained (see Figure 10). In this case, the global minimum of the function at the origin (zero point) is clearly visible, similar to the two-dimensional case.

In this problem, without imposing any constraints on the variables, the behavior of the function is visually examined, and previous findings regarding the existence of numerous local minima and a single global minimum at the origin are clearly confirmed.