Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Origin of the Oocysts

2.2. Oocyst Sporulation

2.3. Oocyst Concentration

2.4. Oocyst Counting and Morphometry

2.5. Standardization of the Inoculum and Infection of the Mice

2.6. Evaluation of Body Weight Development

2.7. Recovery of Hypnozoites from Organs

2.8. Infectivity of Sporozoites and Hypnozoites

2.9. Recovery of Oocysts from the Biological Assay

2.10. Statistical Analysis

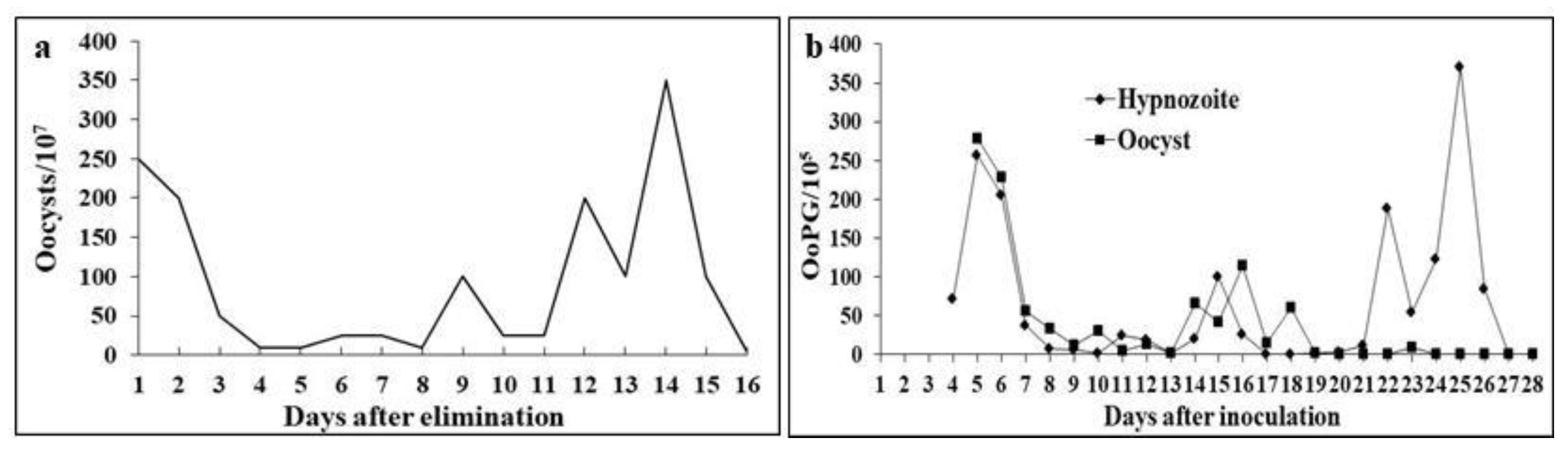

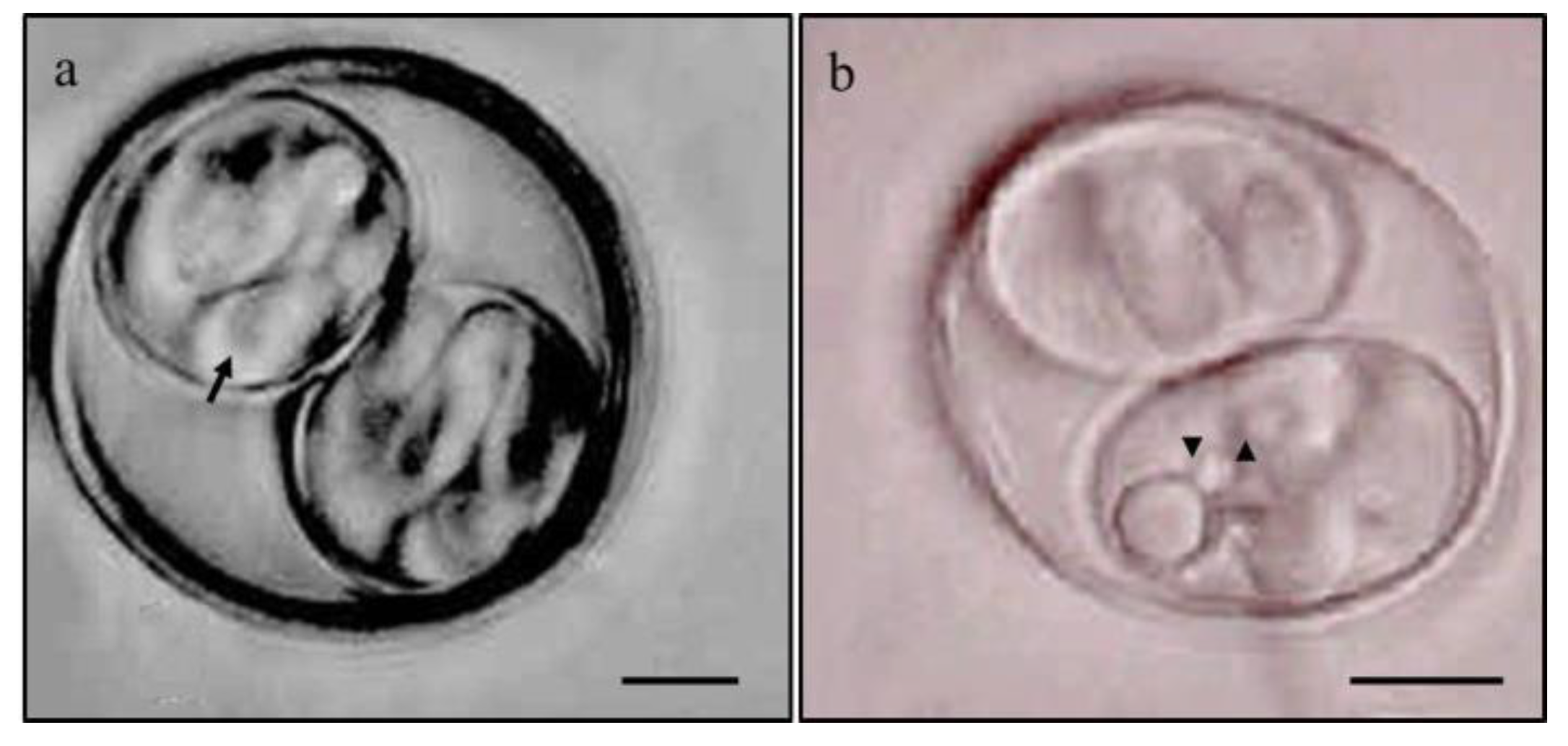

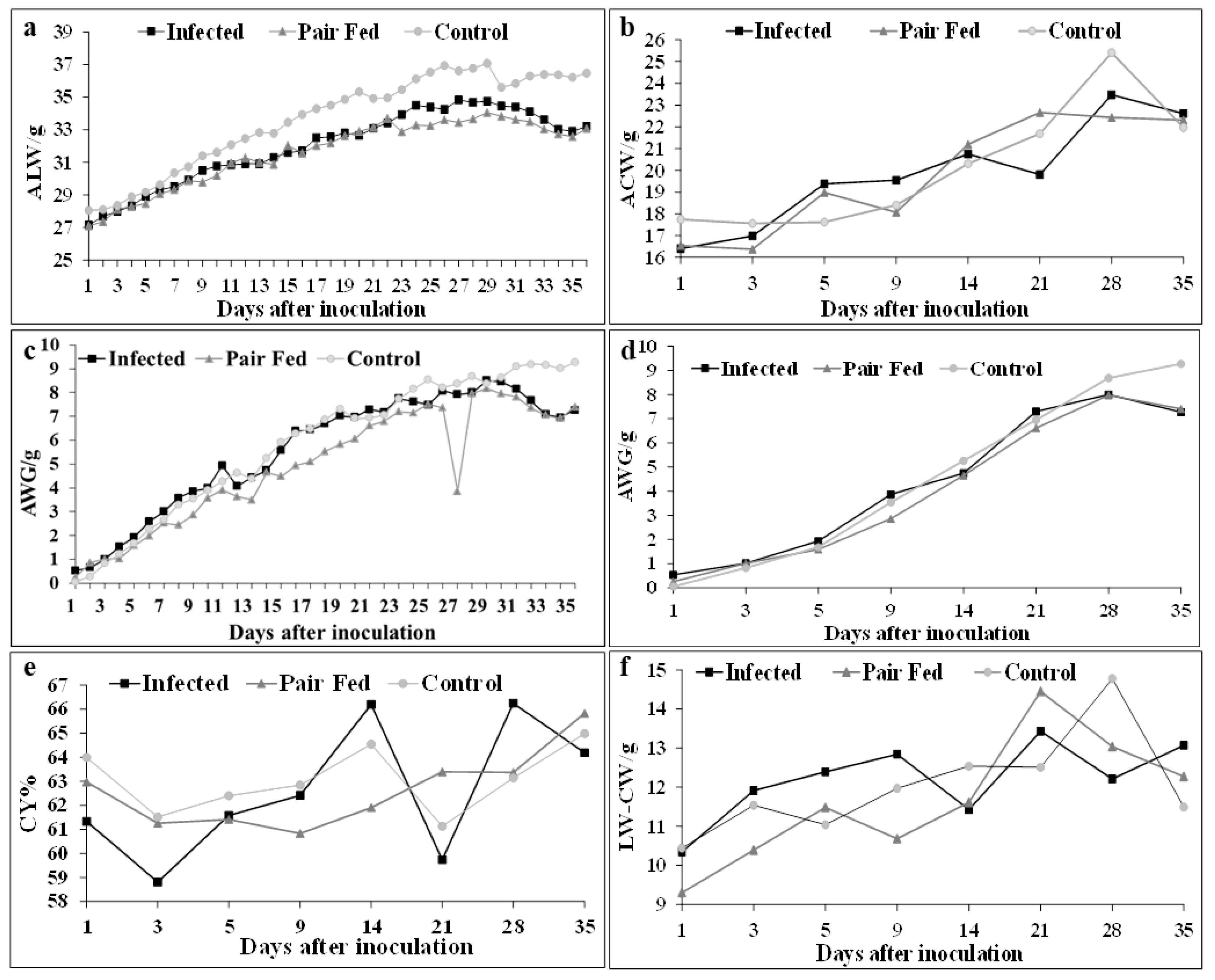

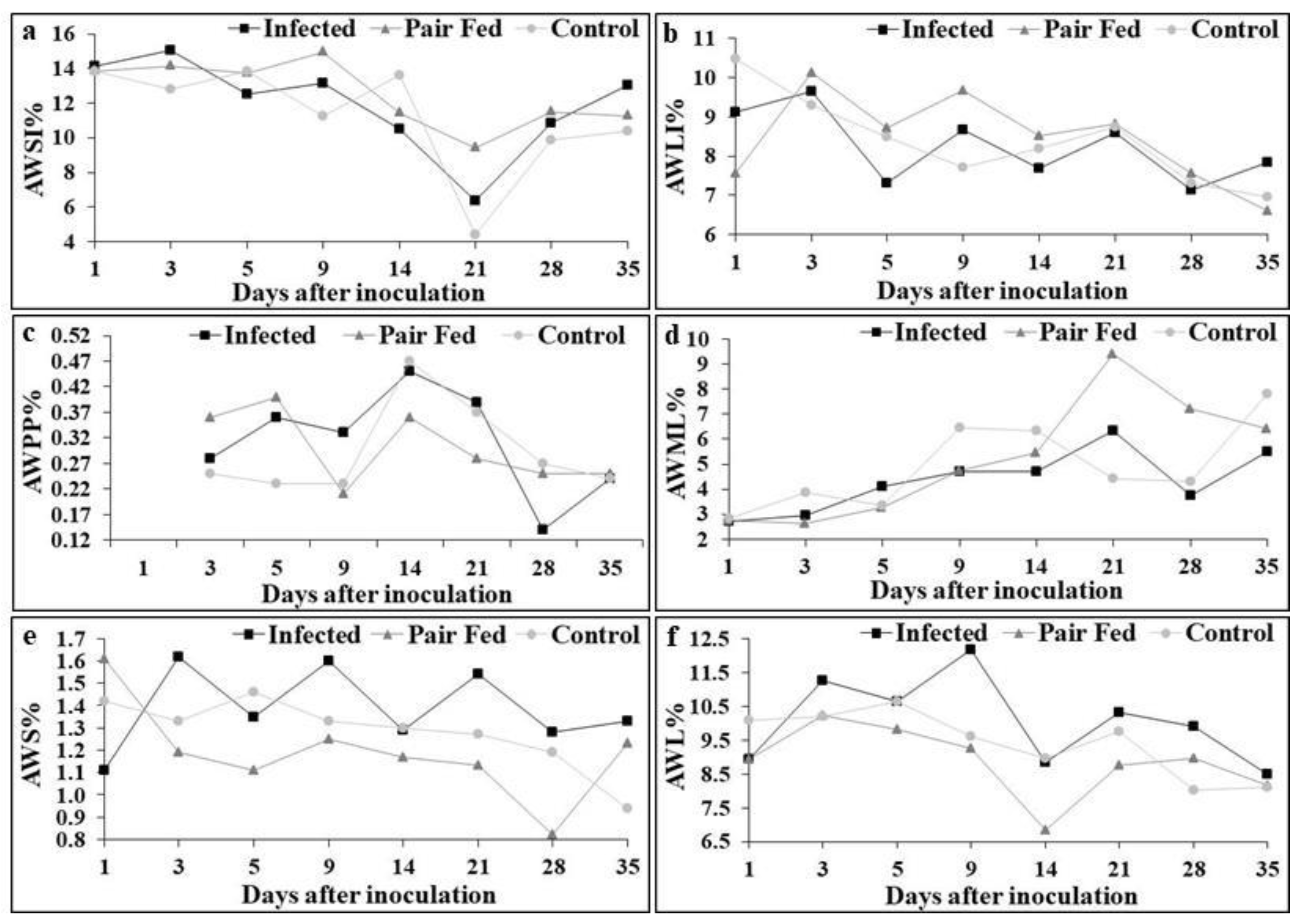

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frenkel, J.K. Besnoitia wallace in cats and rodents: with a reclassification of other cyst-forming isosporoid coccidia. J. Parasitol. 1977, 63, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.D. The Sarcocystidae: Sarcocystis, Frenkelia, Toxoplasma, Hammondia, and Cystoisospora. J. Parasitol. 1981, 28, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreno, R.A.; Schnitzler, B.E.; Jeffries, A.C.; Tenter, A.M.; Johnson, A.M.; Barta, J.R. Phylogenetic analysis of coccidia based on 18S rDNA sequence comparison indicates that Isospora is most closely related to Toxoplasma and Neospora. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 1998, 45, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzen, C.; Müller, A.; Bialek, R.; Diehl, V.; Salzberger, B.; Fätkenheuer, G. Taxonomic position of the human intestinal protozoan parasite Isospora belli as based on ribosomal RNA sequences. Parasitol. Res. 2000, 86, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, J.R.; Martin, D.S.; Carreno, R.A.; Siddall, M.E.; Profousj-Uchelka, H.; Hozza, H.; Powles, M.A.; Sundermann, C. Molecular phylogeny of the other tissue coccidia: Lankesterella and Caryospora. J. Parasitol. 2001, 87, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, J.R.; Schrenzel, M.D.; Carreno, R.; Rideout, B.A. The genus Atoxoplasma (Garnham 1950) as a junior objective synonym of the genus Isospora (Schneider 1881) species infecting birds and resurrection of Cystoisospora (Frenkel 1977) as the correct genus for Isospora species infecting mammals. J. Parasitol. 2005, 91, 726–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, D.S.; Dubey, J.P.; Blackburn, B.L. Biology of Isospora spp. from humans, nonhuman primates and domestic animals. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1997a, 10, 19–34. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P; Lindsay, D.S. Coccidiosis in dogs—100 years of progress. Vet. Parasitol. 2019, 266, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasma, Neospora, Sarcocystis and other tissue cyst forming coccidia of humans and animals. In: Parasitic Protozoa, Kreier, J.P. (ed). Academic Press, New York, 1993, pp. 5–57.

- Dubey, J.P.; Mehlhorn, H. Extraintestinal stages of Isospora ohioensis from dogs in mice. J. Parasitol. 1978, 64, 689–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, J.P. Life cycle of Isospora ohioensis in dogs. Parasitol. 1978, 77, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehl, I.E.; Prosl, H.; Mundt, H.C.; Tichy, A.G.; Joachim, A. Canine isosporosis -epidemiology of field and experimental infections. J. Vet. Med. 2006, 53, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Cheon, D.S.; Moon, E.A.; Seo, D.J.; Jung, S.; Shin, H.; Choi, C. Identification of Cystoisospora ohioensis in a Diarrheal Dog in Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2018, 56, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, N.D. Veterinary Protozoology; Iowa State University Press, Ames, 1985, 414 pp.

- Hilali, M.; Nassar, A.M.; El-Ghaysh, A. Camel (Camelus dromedarius) and sheep (Ovis aries) meat as a source of dog infection with some coccidian parasites. Vet. Parasitol. 1992, 43, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilali, M.; Fatani, A.; Al-Atiya, S. Isolation of tissue cysts of Toxoplasma, Isospora, Hammondia and Sarcocystis from camel (Camelus dromedarius) meat in Saudi Arabia. Vet. Parasitol. [CrossRef]

- Zayed, A.A.; El-Ghaysh, A. Pig, donkey and buffalo meat as a source of some coccidian parasites infecting dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 1998, 78, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, J.K.; Dubey, J.P. Rodents as vectors for feline coccidia Isospora felis and Isospora rivolta. J. Infect. Dis. 1972, 125, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenkel, J.K.; Smith, D.D. Determination of the genera of cystforming coccidia. Parasitol. Res. 2003, 91, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.S.; Lopes, C.W.G. Avaliação do parasitismo por Cystoisospora felis (Wenyon, 1923) Frenkel, 1977 (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) em coelhos tipo carne. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 1998, 7, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Filho, P.R.; Melo, P.S.; Massad, F.V.; Lopes, C.W.G. Determinação da infecção de suínos por Cystoisospora felis (Wenyon, 1923) Frenkel, 1977 (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) através de prova biológica em felinos livres de coccídios. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2003, 12, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Massad, F.V.; Oliveira, F.C.R.; Albuquerque, G.R.; Lopes, C.W.G. Hipnozoítas de Cystoisospora ohioensis (Dubey, 1975) Frenkel, 1977 (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) em frangos. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Vet. 2003, 10, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, P.S.; Carvalho Filho, P.R.; Lopes, C.W.G.; Flausino, W.; Oliveira, F.C.R. Hypnozoites of Cystoisospora felis (Wenyon, 1923) Frenkel, 1977 (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) isolated from piglets experimentally infected. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2003, 12, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, D.S.; Dubey, J.P.; Toivio-Kinnuncan, M.A. , Michiels, J.F.; Blagburn, B.L. Examination of extraintestinal tissue cysts of Isospora belli. J. Parasitol. 83, 620–625. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benator, D.A.; French, A.L.; Beaudet, L.M.; Levy, C.S.; Orenstein, J.M. Isospora belli infection associated with acalculous cholecystitis in a patient with AIDS. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 663–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, Z.; Topazian, M.D. Isospora cholangiopathy: case study with histologic characterization and molecular confrmation. Hum. Pathol. 2009, 40, 1342–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, J.N.; Etchart, C.B.; Astudillo, O.G.; Chertcoff, A.V.; Pantano, M.L.; Carnevale, S. Cystoisospora belli, liver disease and hypothesis on the life cycle. Parasitol. Res. 2022, 121, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo, C.; Macher, A.M; Radany, E.H. Disseminated extraintestinal isosporiasis in a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1987, 87, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michiels, J.F.; Hofman, P.; Bernard, E.; Saint Paul, M.C.; Boissy, C.; Mondain, V.; Lefichoux, Y.; Loubiere, R. Intestinal and extraintestinal Isospora belli infection in an AIDS patient. A second case report. Pathol. Res. Pract. 1994, 190, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comin, C.E.; Santucci, M. Submicroscopic profile of Isospora belli enteritis in a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 1994, 18, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, J.N.; Carnevale, S.; Mariano, M.; Kuo, L.H.; Caballero, A.; Chertcoff, A.; Ibáñez, C.; Bozzini, J.P. Isosporosis and unizoite tissue cysts in patients with acquired immunodefciency syndrome. Hum. Pathol. 2001, 32, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, J.K.; Silva, M.B.; Saldanha, J.C. ; De Silva-Vergara. M.L.; Correia, D.; Barata, C.H.; Silva, E.L.; Ramirez, L.E.; Prata, A. Presença extra-intestinal de cistos unizóicos de Isospora belli em paciente com SIDA: relato de caso. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2003a, 36, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loss, Z.G.; Lopes, C.W.G. . Alguns aspectos clínicos na infecção experimental por Cystoisospora felis (Wenyon, 1926) Frenkel, 1976 (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) em gatos. Arq. UFRRJ 1992a, 15, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Loss, Z.G.; Lopes, C.W.G. Aspecto patológicos da infecção experimental por Cystoisospora felis (Wenyon, 1926) Frenkel, 1976 (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) em gatos. Arq. UFRRJ 1992b, 15, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeséri, L. Beiträge Zur Ätiologie der Coccidiose der hunde. 1. Isospora canis sp. n. Acta Vet. Hung. 1959, 10, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, J.P. Isospora ohioensis sp. n. proposed for I. rivolta of the dog. J. Parasitol. 61, 462–465. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trayser, C.V.; Todd, K.S. Life cycle of Isospora burrowsi n sp (Protozoa: Eimeriidae) from the dog Canis familiaris. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1978, 39, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rommel, M.; Zielasko, B. Untersuchungen uber den Lebenszyklus von Isospora burrowsi (Trayser and Todd, 1978) aus dem Hund. Berl. tierarztl. Wschr. 1981, 94, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dubey, J.P.; Mahrt, J.L. Isospora neorivolta sp. n. from the domestic dog. J. Parasitol. 1978, 64, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadros, W.; Laarman, J.J. Sarcocystis and related coccidium parasites: a brief general review, together with a discussion on some biological aspects of their life cycles and a new proposal for their classification. Act. Leid. 1976, 44, 1–107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dubey, J.P.; Capenter, J.L.; Speer, C.A.; Topper, M.J.; Uggla, A. Newly recognized fatal protozoan disease of dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1988, 192, 1269–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, F.C.R. Avaliação da infecção experimental em camundongos albinos com oocistos esporulados de Cystoisospora ohioensis (Dubey, 1975) Frenkel, 1977 (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) e sua transmissão ao cão doméstico. Tese (Medicina Veterinária, Parasitologia Veterinária), Instituto de Veterinária, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, Seropédica, 172 pp., 2001.

- Oliveira, F.C.R.; Albuquerque, G.R.; Munhoz, A.D.; Lopes, C.W.G. . Oocysts of Cystoisospora ohioensis (Dubey, 1975) Frenkel, 1977 (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) in naturally infected puppies from a litter. Rev. Univ. Rural 2000, 22, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Brazil. Law No. 11,794, of October 8, 2008. It regulates subsection VII of §1 of Article 225 of the Federal Constitution, establishing procedures for the scientific use of animals; repeals Law No. 6,638, of May 8, 1979; and makes other provisions.

- CFMV. Resolution No. 714, of June 20, 2002. It establishes procedures and methods for animal euthanasia and provides other measures. Available at: http://ts.cfmv.gov.br/manual/arquivos/resolucao/714.pdf.

- Dubey, J.P. Refinement of pepsin digestion method for isolation of Toxoplasma gondii from infected tissues. Vet. Parasitol. 1997, 1, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.C.R.; Albuquerque, G.R.; Munhoz, A.D.; Lopes, C.W.G.; Massad, F.V. Hipnozoítas de Cystoisospora ohioensis (Dubey, 1975) Frenkel, 1977 (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) recuperados de órgãos de camundongos através da digestão péptica. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. 2001, 10, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Oduye, O.O.; Bobade, P.A. Studies on an outbreak of intestinal coccidiosis in the dog. J Small Anim Pract. 1979, 20, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, W.M.; Correa, C.N.M.; Langoni, H.; Volpato, O.A.; Tsunoda, K. Canine isosporosis. Canine Pract., 1983, 10: 44-46.

- Olson, M.E. Coccidiosis caused by Isospora ohioensis-like organisms in three dogs. Can. Vet. J. 1985, 26, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Penzhorn, B.L.; De Cramer, K.G.M.; Booth, L.M. Coccidial infection in German shepherd dog pups in a breeding unit. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 1992, 63, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.H.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.D.; Xu, H.K. A case of mixed infection of canine distemper and intestinal protozoa. Chin. J. Prev. Vet. Med. 1993, 19, 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, S.S.; Juyal, P.D.; Kalra, I.S. Clinical Isosporiasis in a racer greyhound dog. Indian Vet. J. 1997, 14, 413–414. [Google Scholar]

- Altreuther, G.; Gasda, N.; Schroeder, I.; Joachim, A.; Settje, T.; Schimmel, A.; Hutchens, D.; Krieger, K.J. Efficacy of emodepside plus toltrazuril suspension (Procox R® oral suspension for dogs) against prepatent and patent infection with Isospora canis and Isospora ohioensis-complex in dogs. Parasitol. Res., 2011, 109 (Suppl 1): S9–S20. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P.; Weisbrode, S.E.; Rogers, W.A. Canine coccidiosis attributed to an Isospora ohioensis-like organism: a case report. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.M.; Zajac, A.M.; Charles, S.; Duncan, R.B.; Lindsay, D.S. Cystoisospora canis Nemeséri, 1959 (syn. Isospora canis), infections in dogs: clinical signs, pathogenesis, and reproducible clinical disease in beagle dogs fed oocysts. J. Parasitol. [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, C.E.; Dubey, J.P. Enteric Coccidial Infections: Isospora, Sarcocystis, Cryptosporidium, Besnoitia, and Hammondia. Vet. Clin: Small Anim. Pract. [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Li, J.; Gong, P.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X. Cystoisospora spp. from dogs in China and phylogenetic analysis of its 18S and ITS1 gene. Vet. Parasitol. [CrossRef]

- Barrera, J.P.; Montoya, A.; Marino, V.; Sarquis, J.; Checa, R.; Miró, G. Cystoisospora spp. infection at a dog breeding facility in the Madrid region: Infection rate and clinical management based on toltrazuril metaphylaxis. Vet. Parasitol. 2024; 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P. Re-evaluation of merogony of a Cystoisospora ohioensis-like coccidian and its distinction from gametogony in the intestine of a naturally infected dog. Parasitol. [CrossRef]

- Mahrt, J.L. Endogenous stages of the life cycle of Isospora rivolta in the dog. J. Parasitol., 1967, 14, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, E.M. , Lopes C.W.G. (1971). Comportamento da Isospora canis, Isospora felis e Isospora rivolta em infecções experimentais em cães e gatos. Arq. UFRRJ 1971, 1, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasma, Hammondia, Besnoitia, Sarcocystis and other tissue cyst-forming coccida of man and animals. In: Protozoa, Kreier, J.P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, 1977; Volume 3, pp. 102–219.

- Dubey, J.P. Experimental Isospora canis and Isospora felis infection in mice, cats, and dogs. J. Protozool. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasma, Hammondia, Besnoitia, Sarcocystis and other tissue cyst-forming coccidia of man and animals. In: Protozoa, Kreier, J.P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, 1992; Volume 6, pp.120–128.

- Brösigke, S.; Heine, J.; Boch, J. Der Nachweis extraintestinallen entwicklingstadien (Dormozoiten) in extraintestinall mit Cystoisospora rivolta oozysten infizierten Mausen. Kleintierprax., 1982, 27, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Loss, Z.G.; Lopes, C.W.G. Efeito da infecção experimental por Cystoisospora felis (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) no ganho de peso de camundongos. Arq. UFRRJ 1992c, 15, 109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, R.B.; Lopes, C.W.G. Distribuição de hipnozoítas de Cystoisospora felis (Weyon, 1923) Frenkel, 1977 (Apicomplexa: Sarcocystidae) em camundongos albinos experimentalmente infectados. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 1996, 5, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.S.; Lopes, C.W.G. Hipnozoítas de Cystoisospora felis (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae). Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Vet. [CrossRef]

- Fayer, R. , Frenkel J.K. (1979). Comparative infectivity for calves of oocysts of feline coccidia: Besnotia, Hammondia, Cystoisospora, Sarcocystis and Toxoplasma. J. Protozool. [PubMed]

- Wolters, E.; Heydorn, A.O.; Laudahn, C. Cattle as intermediate host of Cystoisospora felis. [Das Rind als Zwischenwirt von Cystoisospora felis]. Berl. tierarztl. Wschr. 1980, 93, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boyles, T.H.; Black, J.; Meintjes, G.; Mendelson, M. Failure to eradicate Isospora belli diarrhea despite immune reconstitution in adults with HIV—A case series. PLoS One. [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, J.K.; Silva, M.B.; Saldanha, J.; De Silva, M.L.; Correia Filho, V.D.; Barata, C.H.; Lages, E.; Ramirez, L.E.; Prata, A. Isospora belli infection: Observation of unicellular cysts in mesenteric lymphoid tissues of a Brazilian patient with AIDS and animal inoculation. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.C.R.; Stabenow, C.S.; Massad, F.V.; Lopes, C.W.G. Hypnozoites of Cystoisospora Frankel, 1977 (Apicomplexa: Cystoisosporinae) in Mongolian gerbil lymph nodes and their transmission to cats free of coccidia. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. [PubMed]

- Brösigke, S. Untersuchungen an extraintestinalen entwicklungsstadien (Dormozoiten) von Cystoisospora rivolta der Katze in der Maus. Dissertation zur Erlangung der tiermedizinnischen Doktor der Tierarztlichen, Muchen, 1981, 37 pp.

- Dubey, J.P. Life cycle of Isospora rivolta (Grassi 1879) in cats and mice. J. Protozool., 1979, 26, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehlhorn, H.; Markus, M.B. Electron microscopy of stages of Isospora felis of the cat in the mesenteric lymph nodes of the mouse. Z. Parasitenkd., 1976, 51, 25–29. [CrossRef]

- Boch, J.; Göbel, E.; Heine, J.; Erber, M. Isospora-Infektionen bei Hund und Katze. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr, 1981, 94, 384–391.

- Markus, M.B. The hypnozoite of Isospora canis. S. Afr. J. Sci. 1983, 79, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, D.S.; Houk, A.E.; Mitchell, S.M.; Dubey, J.P. Developmental Biology of Cystoisospora (Apicomplexa: Sarcocystidae) Monozoic Tissue Cysts. J. Parasitol. [CrossRef]

- Long, P.L. The biology of the coccidia. Univ. Park Press: Baltimore, 1982, 502 pp.

| Route of Infection | na | Diameters | Morphometric | |

| Measured forms | Major | Minus | Indice | |

| Natural | ||||

| Oocyst | 100 | 21.39±1.71 (18.40-26.80) | 19.23±1.91 (14.40-25.00) | 1.11±0.08 (0.98-1.42) |

| Sporocyst | 100 | 15.48±1.42 (12.20-19.00) | 10.24±0.96 (8.40-13.00) | 1.51±0.13 (1.08-1.83) |

| Experimental using sporozoites | ||||

| Oocyst | 100 | 25.28±2.12 (19.84-29.76) | 23.32±2.18 (17.67-27.59) | 1.08±0.06 (1.00-1.34) |

| Sporocyst | 100 | 18.02±1.91 (13.02-21.70) | 11.59±1.57 (8.68-19.84) | 1.57±0.12 (1.00-1.97) |

| Experimental using hypnozoites | ||||

| Oocyst | 100 | 26.42±1.69 (22.32-30.07) | 24.47±1.36 (21.39-27.28) | 1.08±0.04 (1.00-1.20) |

| Sporocyst | 100 | 18.97±1.77 (11.47-22.63) | 12.00 (16.43-7.13) | 1.59±0.17 (1.13-2.07) |

| DAIa | nb | GROUPSc | |||||||

| INFECTED | PAIR-FED | CONTROL | |||||||

| 0 | 45 | 27.22±2.74 | 27.11±2.22 | 28.04±2.80 | |||||

| 1 | 45 | 27.69±2.88 | 27.28±2.39 | 28.10±2.60 | |||||

| 3 | 40 | 28.33±3.18 | 28.30±2.01 | 28.88±2.77 | |||||

| 5 | 35 | 29.30±3.44 | 29.06±2.30 | 29.61±2.82 | |||||

| 9 | 30 | 30.77±2.86 | 30.19±2.56 | 31.28±3.22 | |||||

| 14 | 25 | 31.60±3.04 | 32.02±3.07 | 33.44±3.18 | |||||

| 15 | 20 | 31.70±2.78 | (K) | 31.57±2.44 | (K,Y) | 33.94±3.33 | (Z) | ||

| 16 | 20 | 32.66±2.70 | (KY) | 32.02±2.36 | (Y) | 34.30±3.35 | (K,Z) | ||

| 17 | 20 | 32.56±2.44 | (KY) | 32.18±2.36 | (Y) | 34.50±3.54 | (K,Z) | ||

| 18 | 20 | 32.80±2.25 | (KY) | 32.62±2.58 | (Y) | 34.86±3.60 | (K,Z) | ||

| 19 | 20 | 32.14±3.20 | (K) | 32.90±2.66 | (K,Y) | 35.32±3.64 | (Y,Z) | ||

| 21 | 20 | 33.42±2.21 | 33.75±3.05 | 34.95±3.93 | |||||

| 25 | 15 | 34.25±1.83 | (K) | 33.60±2.45 | (K,Y) | 36.93±4.50 | (Y,Z) | ||

| 26 | 15 | 34.83±2.02 | (KY) | 33.45±2.44 | (Y) | 36.61±4.31 | (K,Z) | ||

| 27 | 15 | 34.68±2.01 | (KY) | 33.66±2.59 | (Y) | 36.76±4.46 | (K,Z) | ||

| 28 | 15 | 34.75±2.03 | (K,Y) | 34.06±2.70 | (Y) | 37.07±4.34 | (K,Z) | ||

| 35 | 10 | 33.22±4.73 | 33.08±3.42 | 36.47±4.09 | |||||

| DAIa | nb | GROUPSc | |||||||

| INFECTED | PAIR-FED | CONTROL | |||||||

| 1 | 45 | 0.53±0.61 | (K) | 0.25±0.75 | (K,Y) | 0.05±0.66 | (Y,Z) | ||

| 2 | 40 | 0.66±0.76 | (KY) | 0.87±0.98 | (Y) | 0.28±0.76 | (K,Z) | ||

| 3 | 40 | 1.01±0.98 | 1.01±0.98 | 0.82±1.11 | |||||

| 5 | 35 | 1.93±1.34 | 1.58±1.33 | 1.68±1.12 | |||||

| 8 | 30 | 3.58±1.45 | (K) | 2.45±1.13 | (Y,Z) | 3.30±1.66 | (K,Z) | ||

| 9 | 30 | 3.86±1.47 | (K) | 2.86±1.28 | (Y,Z) | 3.53±1.70 | (K,Z) | ||

| 14 | 25 | 4.74±2.03 | 4.65±1.30 | 5.26±1.54 | |||||

| 15 | 20 | 5.59±1.61 | (K,Y) | 4.48±1.61 | (Y) | 5.93±1.58 | (K,Z) | ||

| 16 | 20 | 6.39±1.53 | (K) | 4.94±1.69 | (Y) | 6.29±1.55 | (K,Z) | ||

| 17 | 20 | 6.44±1.85 | (K) | 5.10±1.73 | (Y) | 6.49±1.56 | (K,Z) | ||

| 19 | 20 | 7.03±1.91 | (K,Z) | 5.82±1.85 | (K,Y) | 7.32±1.71 | (Z) | ||

| 21 | 20 | 7.30±2.05 | 6.61±1.92 | 6.95±2.02 | |||||

| 27 | 15 | 7.93±1.93 | (K) | 3.84±1.33 | (Y) | 8.37±2.32 | (K,Z) | ||

| 28 | 15 | 8.00±2.24 | 7.97±2.22 | 8.68±2.26 | |||||

| 35 | 10 | 7.27±4.71 | 7.41±3.29 | 9.27±2.47 | |||||

| DAIa | nb | GROUPSc | |||||||

| INFECTED | PAIR-FED | CONTROL | |||||||

| 1 | 5 | 16.40±0.65 | 16.54±1.12 | 17.75±2.75 | |||||

| 3 | 5 | 16.99±1.43 | 16.38±0.74 | 17.56±1.65 | |||||

| 5 | 5 | 19.38±1.35 | 18.98±0.36 | 17.62±1.91 | |||||

| 9 | 5 | 19.55±1.05 | 18.07±1.55 | 18.40±1.31 | |||||

| 14 | 5 | 20.75±3.59 | 21.19±3.11 | 20.30±1.65 | |||||

| 21 | 5 | 19.81±2.13 | (K,Z) | 22.66±0.41 | (Y) | 21.68±0.93 | (Y,Z) | ||

| 28 | 5 | 23.47±0.92 | (K,Y) | 22.43±1.30 | (Y) | 25.40±1.54 | (K,Z) | ||

| 35 | 5 | 22.61±1.00 | 22.31±2.41 | 21.96±1.30 | |||||

| DAIa | HYPOZOITES/VISCERA | TOTAL | |||||||||||||||

| Small intestine | Large intestine | Peyer's patch | Mesenteric lymph node | Spleen | |||||||||||||

| nb | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| 1 | 102 | 17.62 | 147 | 25.39 | 135 | 23.31 | 86 | 14.85 | 109 | 18.83 | 579 | 100 | |||||

| 3 | - | - | - | - | 50 | 7.17 | 506 | 72.60 | 141 | 20.23 | 697 | 100 | |||||

| 5 | - | - | - | - | 28 | 25.00 | 44 | 39.29 | 40 | 35.71 | 112 | 100 | |||||

| 9 | - | - | - | - | 9 | 4.89 | 60 | 32.61 | 115 | 62.50 | 184 | 100 | |||||

| 14 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 38 | 18.45 | 168 | 81.55 | 206 | 100 | |||||

| 21 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 60 | 23.90 | 191 | 76.10 | 251 | 100 | |||||

| 28 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 35 | 12.96 | 235 | 87.04 | 270 | 100 | |||||

| 35 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | 4.42 | 108 | 95.58 | 113 | 100 | |||||

| GRAND TOTAL | 102 | 4.23 | 147 | 6.09 | 222 | 9.20 | 834 | 34.58 | 1.107 | 45.90 | 2.412 | 100 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).