1. Introduction

The adoption of Large Language Models (LLMs) has begun to reshape core processes in higher education by providing benefits such as personalized learning support, immediate feedback, and streamlined administrative tasks [Dempere et al., 2024; Gan et al., 2023]. Yet these models also pose concerns around data privacy, misinformation, and the perpetuation of biases from their underlying training corpora, barriers that significantly shape how society perceives and accepts these technologies [Walter, 2024]. Furthermore, the digital divide remains a critical factor in whether such tools can be integrated fairly and effectively. Disparities in digital literacy and resource access disproportionately affect students from diverse demographic backgrounds, potentially exacerbating negative perceptions of LLMs and limiting their equitable adoption [Zhou, Fang, and Rajaram, 2025].

In parallel, the successful integration of such tools often hinges on users’ technology readiness—encompassing comfort, optimism, and willingness to learn—and their perceptions of a system’s usefulness and ease of use. When these factors converge favorably, adoption likelihood rises, as individuals with higher readiness levels are more inclined to perceive practical value and overcome initial uncertainties [Godoe and Johansen, 2012]. Conversely, individuals exhibiting lower technology readiness may still be reluctant to adopt even clearly beneficial tools, underscoring the importance of addressing diverse user profiles through targeted support and clear evidence of LLMs educational value.

Against this backdrop, Wijaya et al. [2024] underscore that college students’ readiness for AI is highly variable, and high proficiency in AI-related technologies does not automatically translate into improved educational outcomes unless supported by thoughtful instructional design. Effective AI integration relies on fostering social norms—encompassing peer influences, institutional policies, and cultural practices that normalize and encourage the use of GenAI—and establishing a robust ethical framework that addresses concerns such as data privacy, bias, and potential negative impacts. Together, these elements ensure that technical competence is balanced with an environment and guidelines that promote responsible and equitable adoption of AI in educational settings.

Further extending the conclusions drawn from college-based studies, Carvalho et al. [2024] applied the Attitude Towards Artificial Intelligence Scale (ATAI) across multiple professional contexts and found that participants commonly regard AI as beneficial, yet harbor notable concerns about potential job displacement and ethical dilemmas. Nevertheless, the study highlights a critical disconnect: many participants either could not identify specific AI tools or were unaware of the extent to which AI-driven systems are already embedded in their daily routines, which increases the risk of unconscious biases or exploitative use.

Such gaps in awareness and readiness underscore the imperative for structured, inclusive approaches to GenAI education and policy. Metacognition plays a pivotal role here, as it enables individuals to monitor, evaluate, and adapt their own cognitive processes when engaging with complex technological systems [Yin et al., 2024; Zhou, Teng, and Al-Samarraie, 2024]. By equipping computing learners with the ability to reflect on and refine their learning processes, metacognitive skills foster more user-friendly and adaptive interactions with digital tools, coding and data analysis [Leite, Guarda, and Silveira, 2023].

In higher education, metacognition is increasingly vital—not only for academic achievement but also for tackling societal issues such as ethical decision-making, responsible GenAI use, and bridging the digital divide [Zhou, Fang, and Rajaram, 2025]. Expanding on this concept, Tu et al. [2023] argue that LLMs are reshaping the data science pipeline, moving learners from task execution toward higher-order thinking, creativity, and project oversight, precisely the areas where metacognitive skills are vital.

Additionally, recent evidence highlights GenAI’s influence on the mental health of teachers and students, manifesting in both positive and negative ways. In a study with over 300 educators, Delello et al. [2025] note that automating routine tasks can lower stress levels and lighten teachers’ workloads, giving them more time and energy for lesson planning and individualized student support. However, there is a risk of increased social isolation and overreliance on technology, leading to anxiety or dependency among students who rely on GenAI to passively fulfill academic tasks.

1.1. Objectives

As computing becomes increasingly embedded in everyday life, it is crucial to understand how metacognitive strategies mediate the social and behavioral dimensions of technology use. In this context, metacognitive strategies are expected to positively predict LLM acceptance and act as a protective factor against cognitive and emotional depletion. To test this hypothesis, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is used to analyze the interplay between metacognition, academic burnout, and LLM acceptance in computing education. The mediation hypotheses are elaborated as follows:

H1: Effective metacognitive strategies are positively associated with the acceptance and perceived usefulness and value of LLMs as learning tools.

H2: Effective metacognitive strategies are negatively related to academic burnout, such that an increased use of these strategies is associated with lower levels of cognitive and emotional depletion.

H3. The perceived usefulness of LLMs as effective learning aids—by reducing cognitive and emotional workload—increases with higher levels of academic burnout.

H4: Academic burnout mediates the relationship between effective metacognitive strategies and LLM acceptance, such that the stress-reducing benefits of metacognitive strategies are expected to indirectly promote a more favorable acceptance of LLMs.

1.2. Related Works

Recent research has begun to explore how generative AI (GenAI) impacts student cognition and learning outcomes in higher education. Zhou, Teng, and Al-Samarraie [2024], for instance, examined how students’ perceptions of GenAI influence critical thinking and problem-solving, while also underscoring the mediating role of self-regulation. Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), they surveyed 223 university students to assess three core attributes of GenAI—perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and perceived learning value—and their impact on higher-order cognitive skills. The authors reported that while ease of use significantly fostered critical thinking and problem-solving through self-efficacy, perceived learning value and usefulness did not. These findings suggest that, while AI tools can offer an environment conducive to developing higher-order cognitive skills, this might not necessarily translate to the enhancement of students’ skills.

Expanding upon these foundations, Xiao et al. [2024] conducted a large-scale investigation to examine how AI literacy shapes students’ academic well-being and educational attainment in online learning contexts. In their SEM, administered among undergraduate students from both Iran and China, the authors identified a direct positive relationship between AI literacy and students’ academic performance. More importantly, they demonstrated that academic well-being—encompassing factors such as engagement, positive emotions, and sense of purpose—acts as a key mediator in this process, amplifying the effect of AI literacy on learning outcomes.

Sapancı [2023] also investigated the relationships between metacognition, students’ well-being, and academic burnout using SEM with psychometric data. The study, conducted with 310 convenience-sampled students, demonstrated that dysfunctional metacognitions positively predict burnout, whereas mindfulness serves as a protective factor. These findings suggest that students who struggle with self-regulation and experience high cognitive stress may develop negative attitudes toward learning. Conversely, students with effective metacognitive strategies are better equipped to manage academic demands, reducing burnout and increasing openness to learning.

2. Methodology

2.1. Procedures and Participants

The dataset used in this study is a publicly available educational dataset on Kaggle [Pinto, 2025], comprising responses from 178 undergraduate students enrolled in computer and data science programs at the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB). Of the participants, 143 were male (80.3%) and 35 female (19.7%), a distribution that reflects the gender imbalance typical of computing courses at the institution. The dataset includes detailed sociodemographic information and responses to five psychometric scales, originally developed in Portuguese and contextualized for the use of data analysis and LLMs. This linguistic and disciplinary tailoring is particularly relevant, as Pinto et al. [2023] emphasize that LLMs are having an early and pronounced impact on computing education—only 4.5% of students in the sample reported not using LLMs for academic tasks.

2.2. Instruments

To examine the relationships between academic burnout, learning strategies with LLMs, and technology acceptance, three psychometric instruments were selected from the five available in the dataset: Academic Burnout Model, 4 items (ABM-4); Learning Strategies Scale with Large Language Models, 6 items (LS/LLMs-6); and LLM Acceptance Model Scale, 5 items (TAME/LLMs-5). Each scale employed a 7-point Likert format, allowing for nuanced measurement of students' perceptions and behaviors.

The ABM-4 assesses students’ levels of academic burnout, focusing on key dimensions such as emotional exhaustion, disengagement, and perceived academic overload. Validated by Pinto et al. [2023], ABM-4 evaluates the extent to which students experience mental and emotional strain due to academic pressures, capturing their self-reported fatigue and motivation decline in response to prolonged academic demands (

Table 1). The total score is calculated by summing the items, reflecting the overall intensity of burnout symptoms.

The LS/LLMs-6 is designed to analyze how students engage with LLMs as learning tools, this scale consists of two distinct subscales: Dysfunctional Learning Strategies (DLS/LLMs-3) and Metacognitive Learning Strategies (MLS/LLMs-3). The DLS/LLMs-3 subscale identifies ineffective learning approaches, such as passive reliance on AI-generated content, while the MLS/LLMs-3 subscale captures active metacognitive strategies that enhance learning, such as planning, monitoring, and evaluating AI-assisted knowledge acquisition. Validated by Pinto et al. [2023], this scale ensures a structured assessment of how students integrate LLMs into their learning processes (

Table 2). To compute the total score, the DLS/LLMs-3 score is subtracted from the MLS/LLMs-3 score, as the two subscales are inversely related. This method yields a more interpretable index of functional engagement with LLMs and reflects the balance between constructive and dysfunctional metacognition.

The TAME/LLMs-5 evaluates students’ acceptance and perceived usefulness of LLMs as an educational tool, measuring factors such as trust in AI-generated content, ease of use, and willingness to integrate LLMs into academic routines. Originally validated by Pinto et al. [2023], TAME/LLMs-5 provides insights into students' attitudes toward AI-powered learning technologies (

Table 3). The total score is calculated by summing all item responses, after reverse-coding the negatively worded item, which is phrased to reflect skepticism or resistance toward LLM use.

2.3. Data Analysis

The data analysis was performed in Python. Before estimating the model, all observed variables were standardized using the StandardScaler from the scikit-learn (sklearn.preprocessing) module to ensure comparability of path coefficients and to enhance model convergence efficiency [Pedregosa et al., 2011]. The mediation model was estimated using the semopy library, which offers a flexible Python-based framework for SEM analysis. This approach follows best practices in the field as outlined by Wolf et al. [2013], enabling estimation of both direct and indirect effects through latent and observed variables.

To improve statistical robustness, a bootstrap procedure was applied to generate confidence intervals and p-values for the total and indirect effects, accounting for the sampling distribution of the mediation paths [Preacher and Hayes, 2008]. Compared to traditional regression-based mediation techniques, SEM provides a more nuanced understanding of the complex interrelations between constructs in educational psychology [Wolf et al., 2013].

2.4. GenAI Usage Statement

ChatGPT-4o was used to translate the article into English, ensuring accuracy and clarity while maintaining the original meaning and coherence of the text. However, the authors remain fully responsible for the interpretation, use, and final content of the manuscript.

3. Results

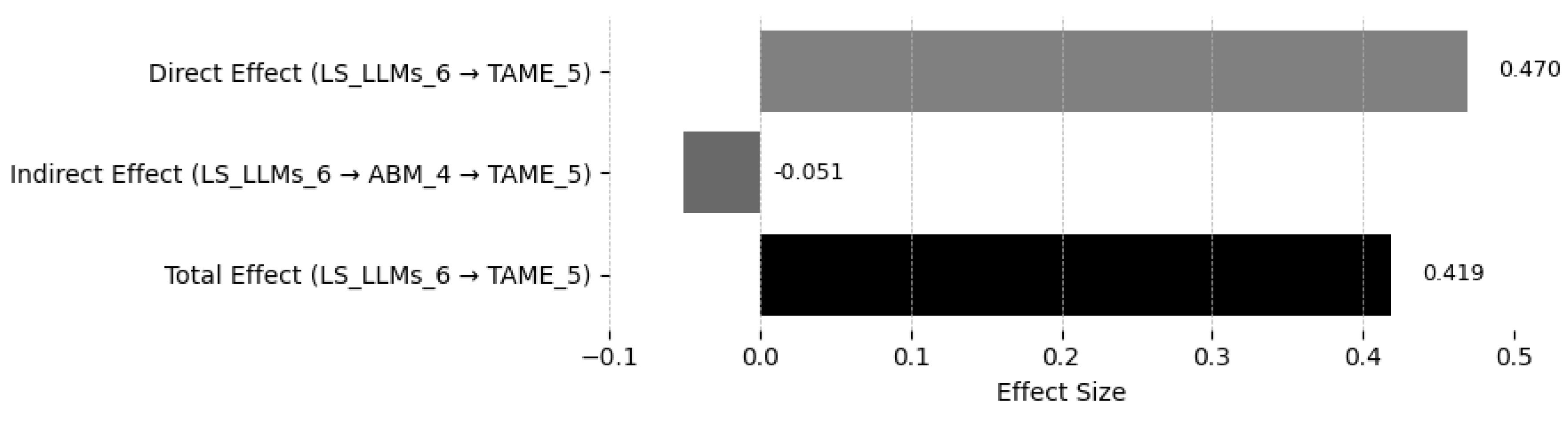

The SEM analysis examined whether academic burnout (ABM-4) mediates the relationship between learning strategies involving LLMs (LS/LLMs-6) and LLM acceptance (TAME/LLMs-5). The results indicate that the direct effect of LS/LLMs-6 on TAME/LLMs-5 remains significant and strong (β = 0.470,

p < .001, β² ≈ 0.220), reinforcing the idea that students who engage more effectively with LLMs are more likely to accept them as valuable educational tools. This model accounts for 22% of the variance in LLM acceptance (

H1 accepted;

Figure 1).

The results indicate an excellent model fit to the data. The chi² = 0.000011 with a p-value = 0.997 is virtually zero and non-significant, suggesting that the model does not significantly differ from the observed data—an ideal outcome in structural modeling. Furthermore, incremental and absolute fit indices such as CFI (1.019), GFI (1.0), AGFI (0.999), NFI (1.0), and TLI (1.077) all exceed the commonly accepted thresholds (typically ≥ 0.95), reinforcing the strength of the model fit. The RMSEA = 0 indicates a perfect fit, and the low values of AIC and BIC suggest a parsimonious and well-specified model.

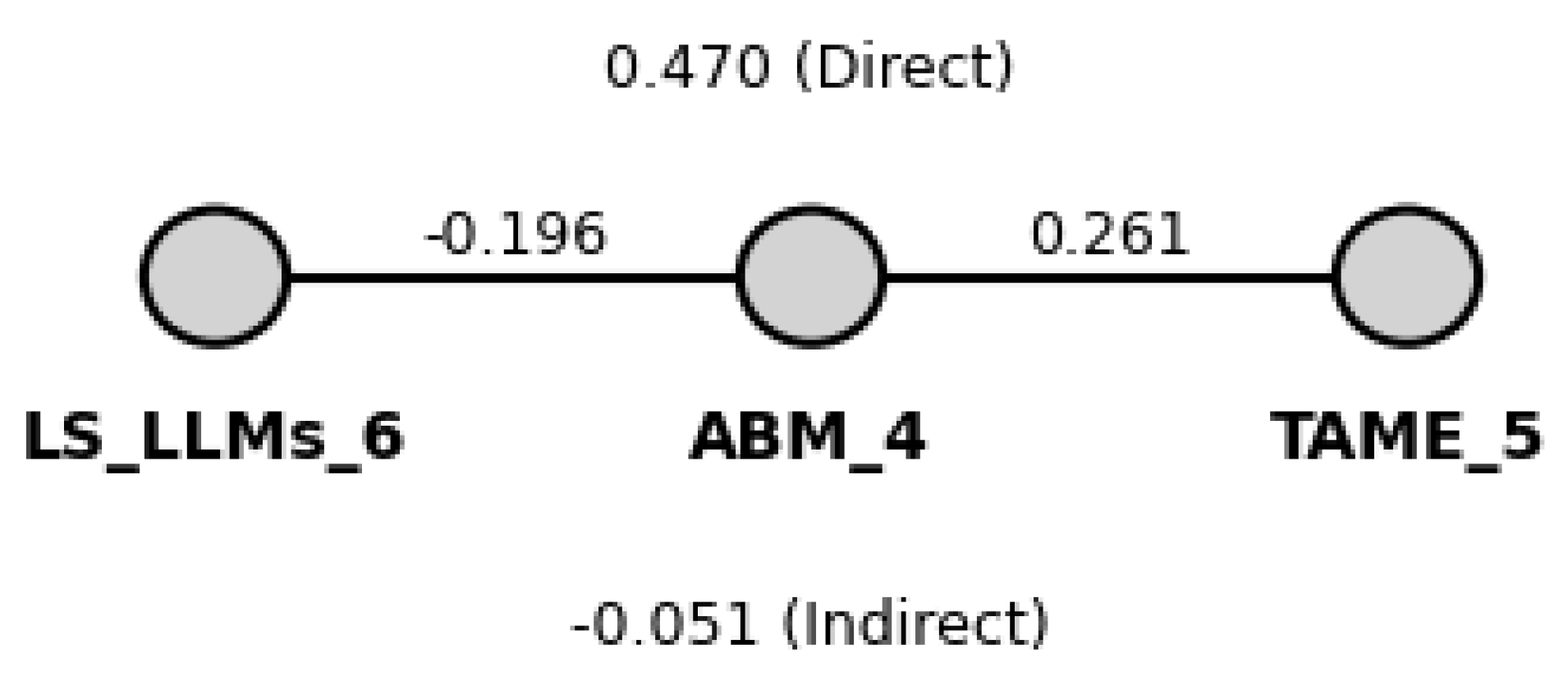

The relationship between LS/LLMs-6 and ABM-4 was also significant (β = -0.195,

p = .007, β² ≈ 0,038), indicating a negative association (

H2 accepted;

Figure 2). This suggests that higher engagement in structured learning strategies with LLMs is linked to lower academic burnout (3.8% of variance explained). Moreover, ABM-4 significantly predicted TAME-5 (β = 0.260,

p < .001, β² ≈ 0,067), suggesting that students experiencing more burnout tend to report higher acceptance of LLMs (6.7% of variance explained)—possibly using them as a compensatory tool to manage academic demands (

H3 accepted;

Figure 2).

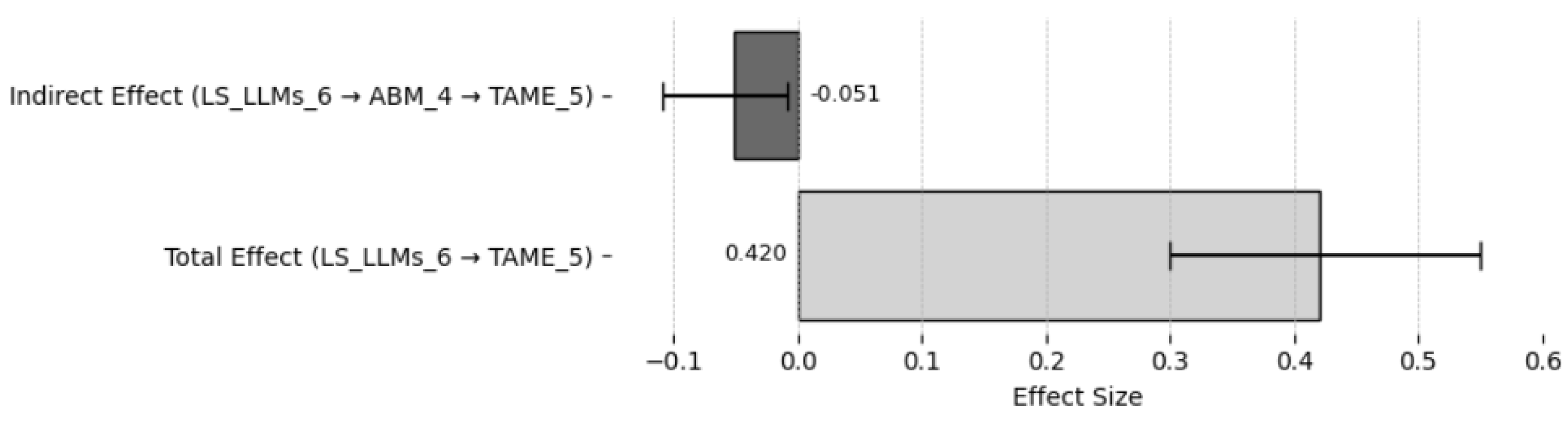

Interestingly, the indirect effect through burnout (ABM-4) was negative (β = –0.051), indicating a suppressor effect (

H4 rejected;

Figure 3). Although metacognitive strategies reduce burnout (as expected), and burnout is positively associated with LLM acceptance—potentially reflecting reactive, coping-oriented use—this indirect pathway resulted in a suppressor effect. This suggests that the strong association between metacognitive strategies and LLM acceptance is not driven by students using LLMs to escape academic obligations. Instead, it appears to reflect a more proactive and strategic engagement with the technology, rooted in metacognitive competence.

However, the small indirect effect through academic burnout indicates that it is not the primary mediator in the relationship between learning strategies and acceptance, accounting for only about 0.26% of the variance (β² = (–0.051)² ≈ 0.0026). This implies that other psychological or contextual factors may play a more substantial mediating role, warranting further investigation. Bootstrap analysis with 10,000 resamples confirmed the statistical significance of this indirect effect (β = –0.051, 95% CI [–0.108, –0.008],

p = .015), supporting the suppressor interpretation (

Figure 3).

Finally, the model presented no concerns regarding multicollinearity, as the Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) for ABM-4 and LS/LLMs-6 were both near 1.04, well below conventional thresholds (VIF < 5), confirming that the predictors were statistically independent. The model also converged in a single iteration using the SLSQP optimizer, reinforcing the stability and reliability of the parameter estimates [Wolf et al., 2013].

4. Discussion

4.1. Rationalizing Predictive Paths and Mediating Effects

The results of this study provide empirical evidence that effective metacognitive learning strategies involving LLMs significantly influence students' acceptance and perceived usefulness of these technologies—both directly and indirectly through academic burnout (22% of variance explained). Students who plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning through AI tools tend to recognize their benefits more clearly. The LS/LLMs-6 includes items such as “I use LLMs to clarify doubts and fill gaps in my programming knowledge” and “I correct my codes using LLMs”, which reflect intentional, self-regulated learning behaviors (

Table 1). These practices are associated with a negative relationship to academic burnout (3.8% of variance explained), supporting the idea that students who employ effective AI-assisted learning strategies tend to experience less cognitive and emotional exhaustion. This aligns with prior literature suggesting that self-regulated learning can mitigate academic stress [Sapancı, 2023].

Although metacognitive strategies are associated with reduced academic burnout, the results reveal that burnout itself positively predicts students’ acceptance of LLMs. This indicates that students experiencing higher levels of academic strain may be more likely to adopt LLMs as a coping mechanism—particularly those who are tech-savvy and comfortable leveraging AI to alleviate cognitive and emotional overload. In this subgroup, LLMs appear to serve not only as learning tools but also as buffers against academic pressure, accounting for approximately 6.7% of the variance in LLM acceptance. These findings suggest a dual role for LLMs: while they support strategic learning for some students, they may represent reactive support systems for others who are overwhelmed by academic demands.

However, the indirect effect of metacognitive strategies on LLM acceptance—mediated through reduced burnout—was very small (0.26% of variance explained) and negative, a statistical pattern known as a suppressor effect. This implies that while burnout contributes to LLM adoption in some students, this coping-driven pathway may hinder the stronger and more central association between metacognitive engagement and constructive LLM use. In other words, students who actively plan, monitor, and evaluate their AI-assisted learning are not primarily motivated by stress or avoidance, but rather by an intentional effort to enhance understanding and autonomy. This distinction is critical: it challenges the narrative that students rely on LLMs to “cheat” or shortcut learning, highlighting instead that proficient, self-regulated learners engage with these tools in pedagogically meaningful ways.

4.2. Reflections for Educational Practice

Computing courses are often among the first to experience the disruptive impact of emerging technologies like LLMs. Students in these fields tend to be more technologically inclined, more exploratory in their use of digital tools, and more receptive to automation. At the same time, LLMs are particularly well-suited for programming tasks—often outperforming their performance in theoretical exams from other disciplines. Programming, after all, is a language of logic and structure, which aligns well with the capabilities of generative AI. This dual advantage has raised concerns in academia about the potential misuse of LLMs, particularly regarding academic dishonesty in computing assignments or exams.

On the other hand, the findings of this study suggest a different narrative: students who engage most actively with these technologies are not primarily motivated by cheating or shortcutting the learning process. Instead, they are driven by the pedagogical and practical advantages LLMs offer, such as real-time debugging, code optimization, and the ability to build functioning software for real-world use cases. These students perceive LLMs as collaborative cognitive partners, tools that can accelerate project-based learning and foster deeper engagement with complex tasks. Importantly, the results highlight that metacognitive learners—those who plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning with intention—are more likely to adopt LLMs constructively. They are not using AI to escape learning, but to enhance it, transforming how knowledge is acquired and applied.

This calls into question traditional evaluation models in computing education. If solving predefined problems or reproducing syntax is no longer a meaningful challenge in the presence of LLMs, then our assessment practices must evolve. Rather than prioritizing memorization and isolated exercises, educational systems should embrace project-based assessments that reward planning, collaboration, and innovation. Evaluating how students set goals, navigate complexity, and make informed decisions—hallmarks of metacognitive growth—may provide a far more accurate reflection of their competence in a world increasingly mediated by intelligent technologies.

4.3. So What if ChatGPT Taught It?

The findings on LLM acceptance and metacognition align with broader discussions on how AI-driven tools are perceived and adopted in education. The acceptance of LLMs is not solely dependent on their technical capabilities but also on students’ cognitive strategies, social influence, and their ability to manage academic stress. This perspective is echoed in the systematic review by Sardi et al. [2025], which found that 71.4% of studies reported a positive impact of generative AI on self-regulated learning, especially through personalized learning paths, metacognitive scaffolding, and motivational support. Likewise, 62.5% of studies identified enhancements in critical thinking, particularly in activities involving reflection, analysis, and decision-making.

Additionally, recent research by Zhou, Fang, and Rajaram [2025] expands this discussion by addressing how disparities in digital literacy and access influence students’ ability to fully benefit from AI-enhanced education. Their large-scale survey of UK undergraduates revealed that students from disadvantaged backgrounds or international origins often lack equitable access to digital resources, which limits their capacity to engage in networked learning environments. In this sense, Zhou, Fang, and Rajaram [2025] provide valuable context to our findings by showing that structural inequalities in digital access and literacy may mediate students’ willingness and ability to meaningfully adopt GenAI tools. Promoting equity in digital education, therefore, is not only a matter of infrastructure, but also of fostering critical digital and metacognitive skills — essential for navigating an increasingly AI-mediated academic landscape.

Beyond cognitive, emotional, and structural factors, ethical awareness and sustainability considerations also play a central role in shaping attitudes toward LLMs. Silva et al. [2024] conducted a survey with computing students and found that future developers acknowledge the importance of ethical, social, and privacy-related responsibilities in designing AI systems. Their results show growing ethical awareness among students, while also pointing to the need for more robust education in digital ethics and socially responsible computing. These findings support the call for AI literacy to encompass not only technical skills but also critical thinking about the implications of AI in society.

Similarly, Breder et al. [2024] examine the environmental impact of large-scale AI systems and introduce the concept of the AI sustainability paradox—the tension between using AI for sustainable development and the environmental costs of building and deploying such systems. Their study highlights the high energy consumption and CO₂ emissions involved in training LLMs and advocates for transparent reporting of environmental costs using accessible tools. These considerations encourage a broader view of GenAI acceptance that includes ecological responsibility and promotes practices such as green AI. Together, these studies emphasize that the adoption of LLMs must be framed not only in terms of usability and efficiency, but also in terms of ethical alignment, equitable access, and environmental impact.