Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

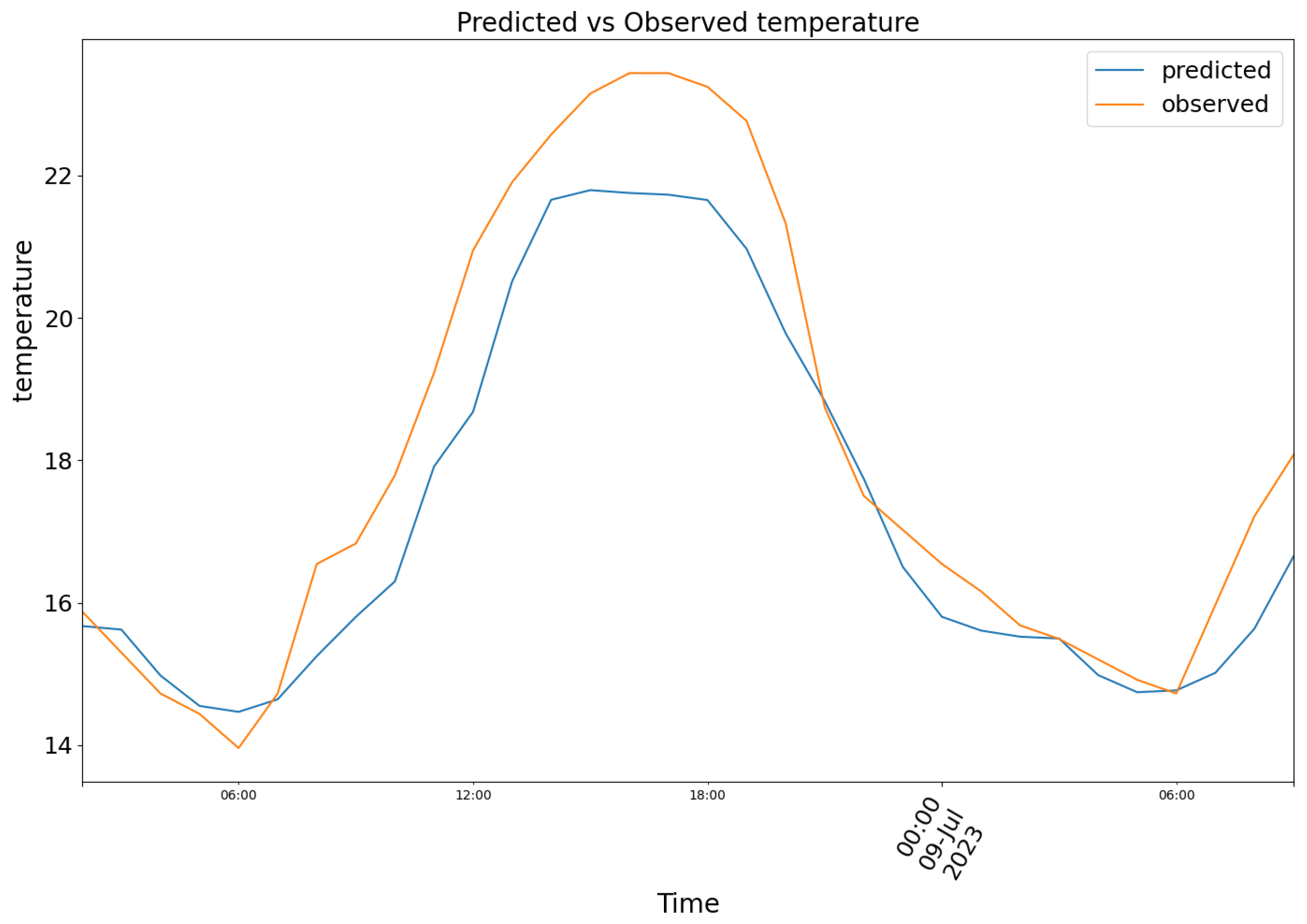

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

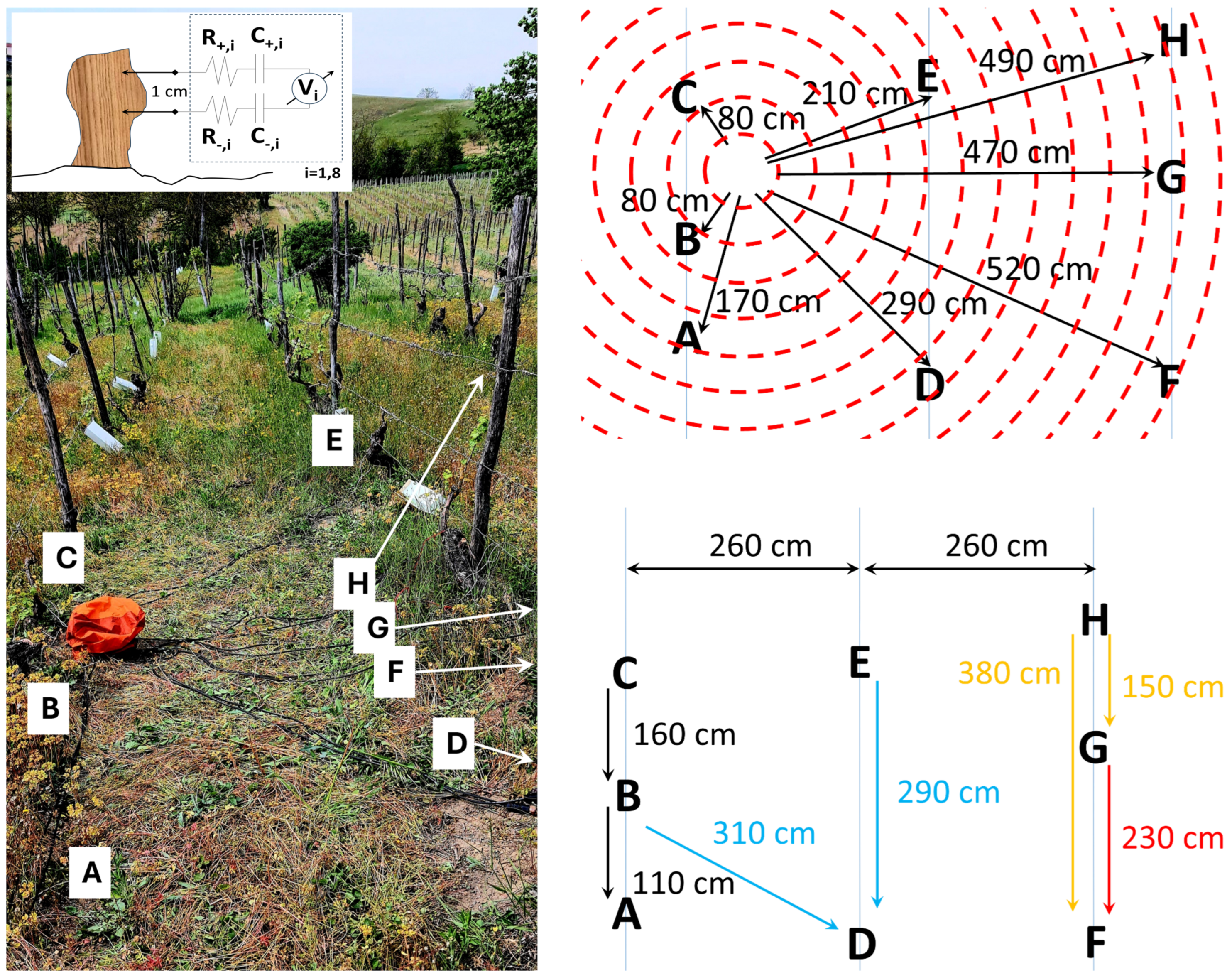

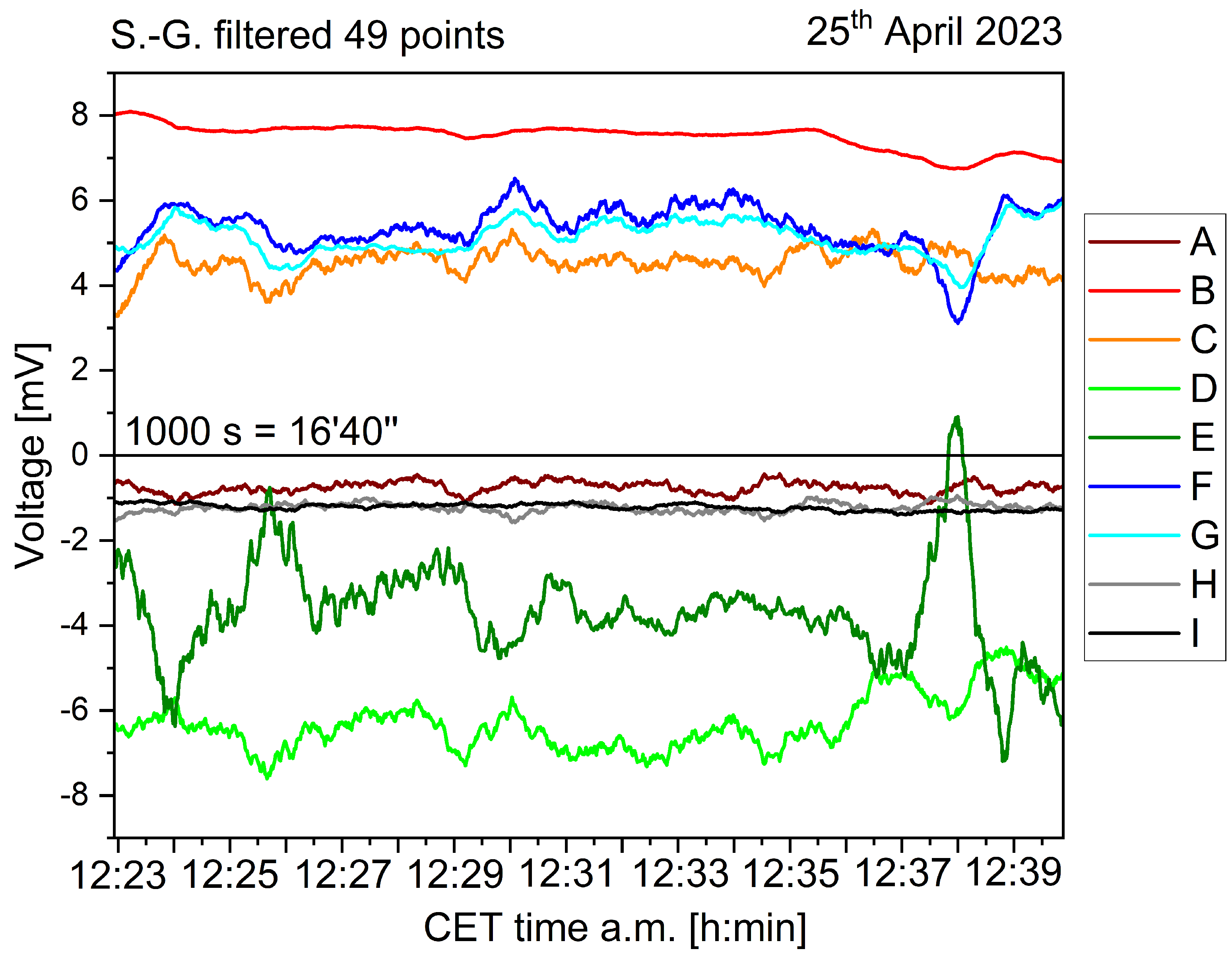

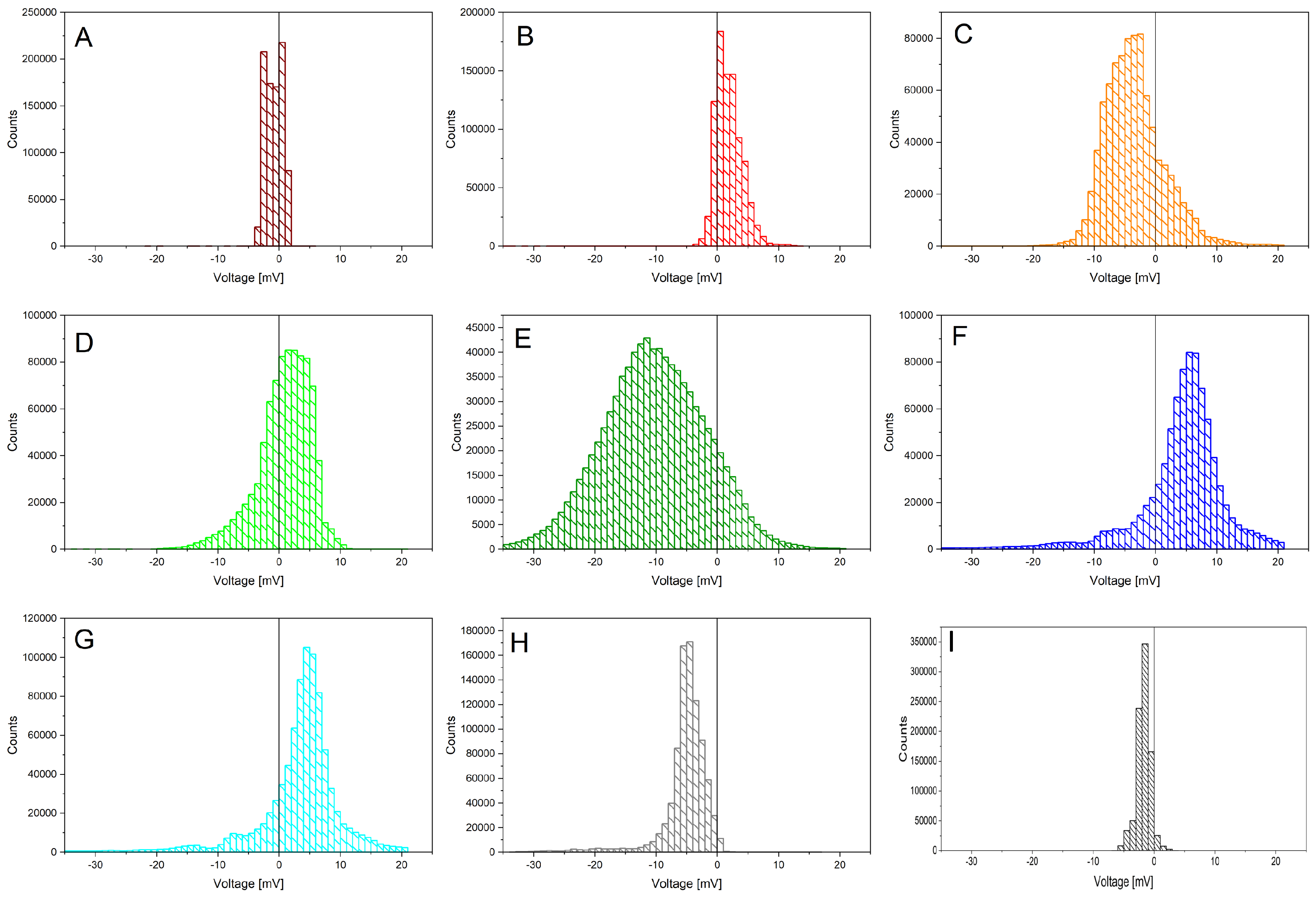

2.1. Experimental Setup and Data Statistics

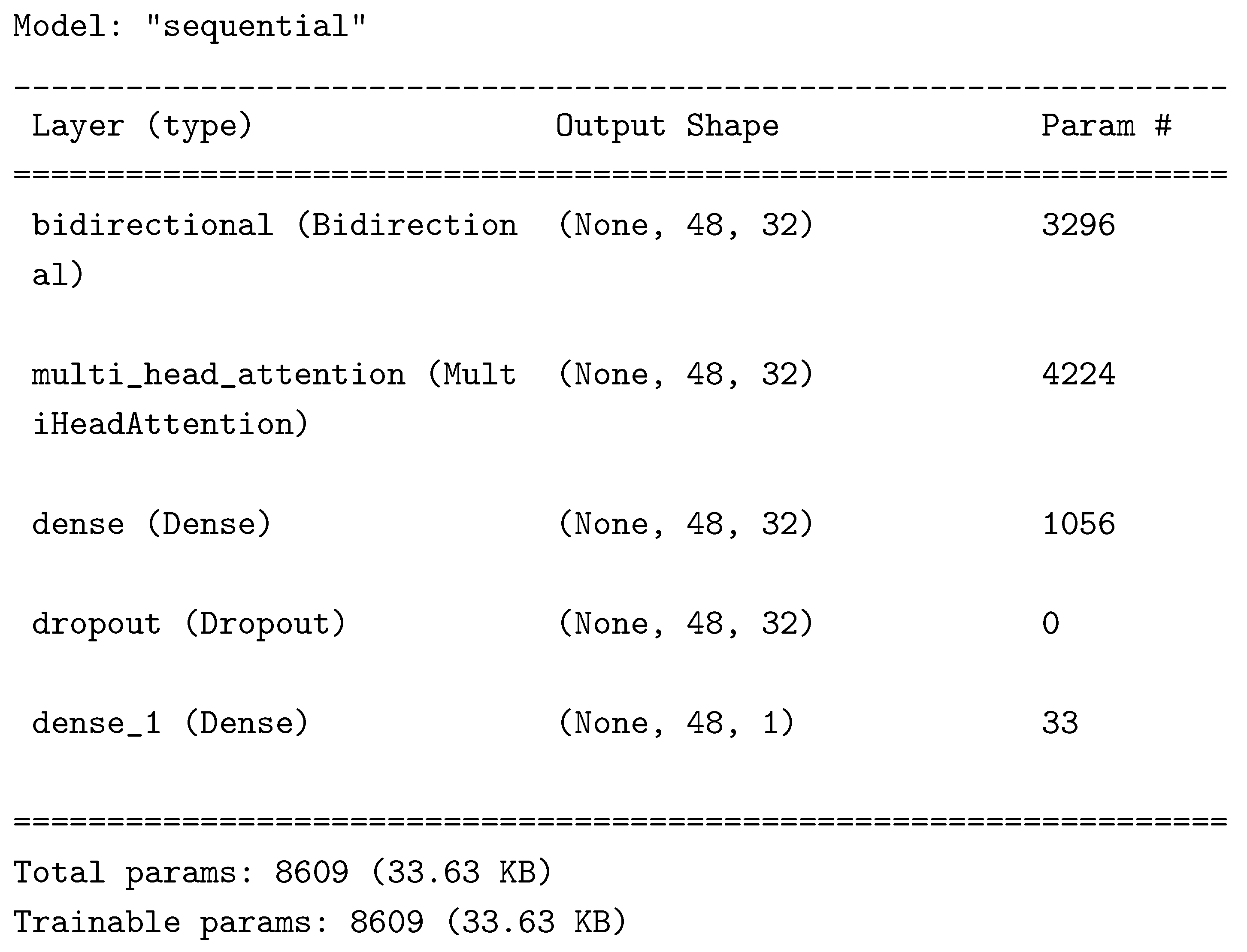

2.2. Software Setup

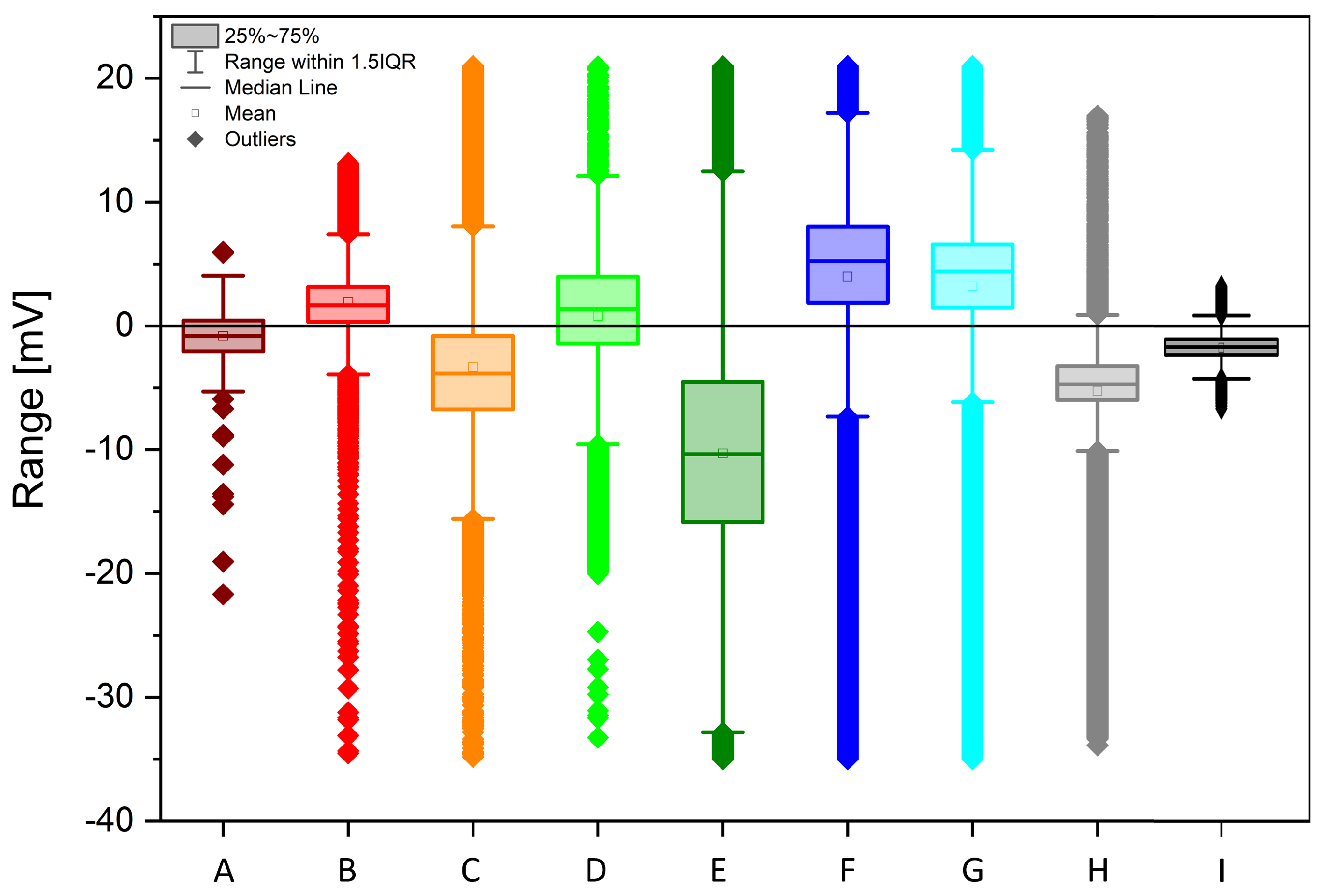

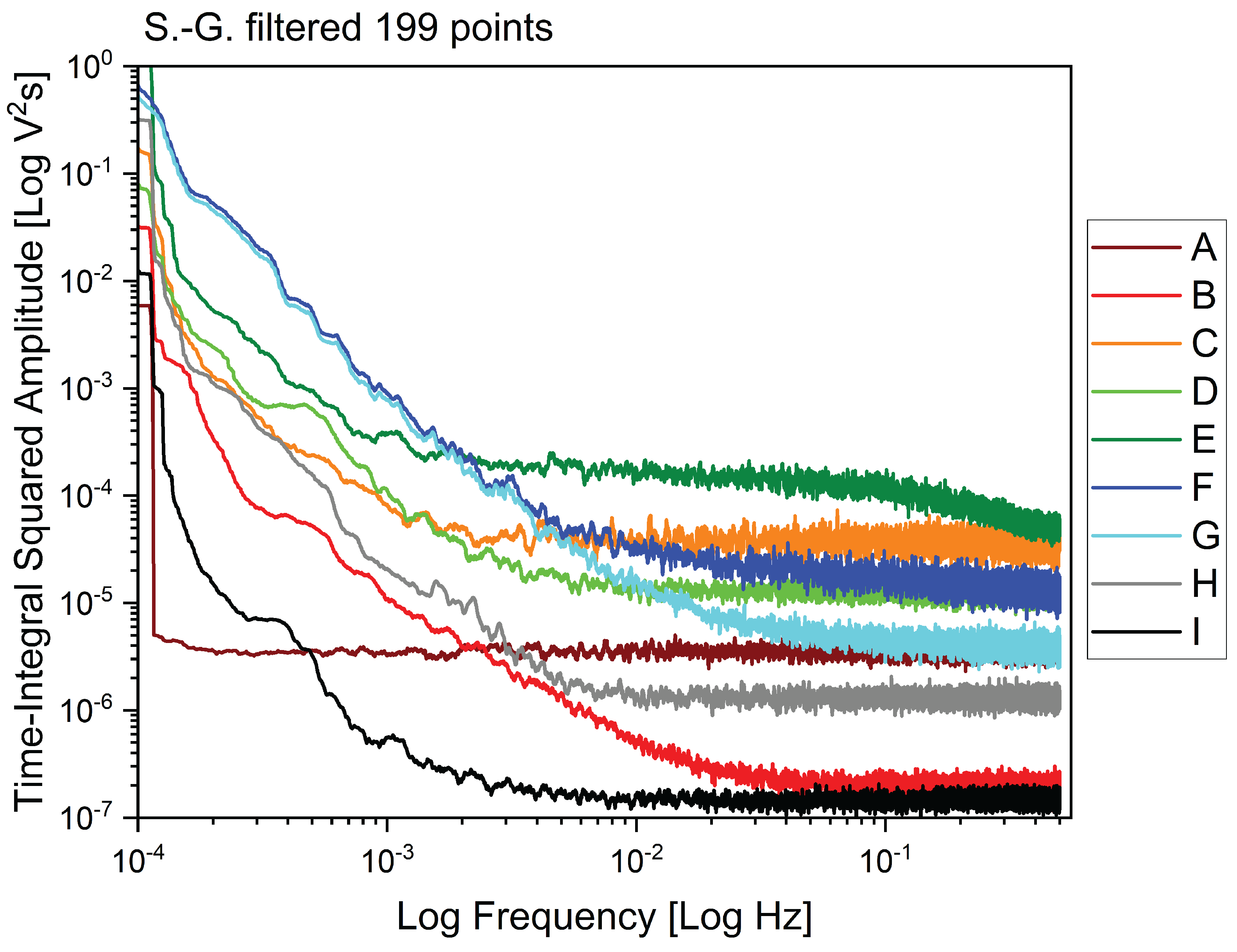

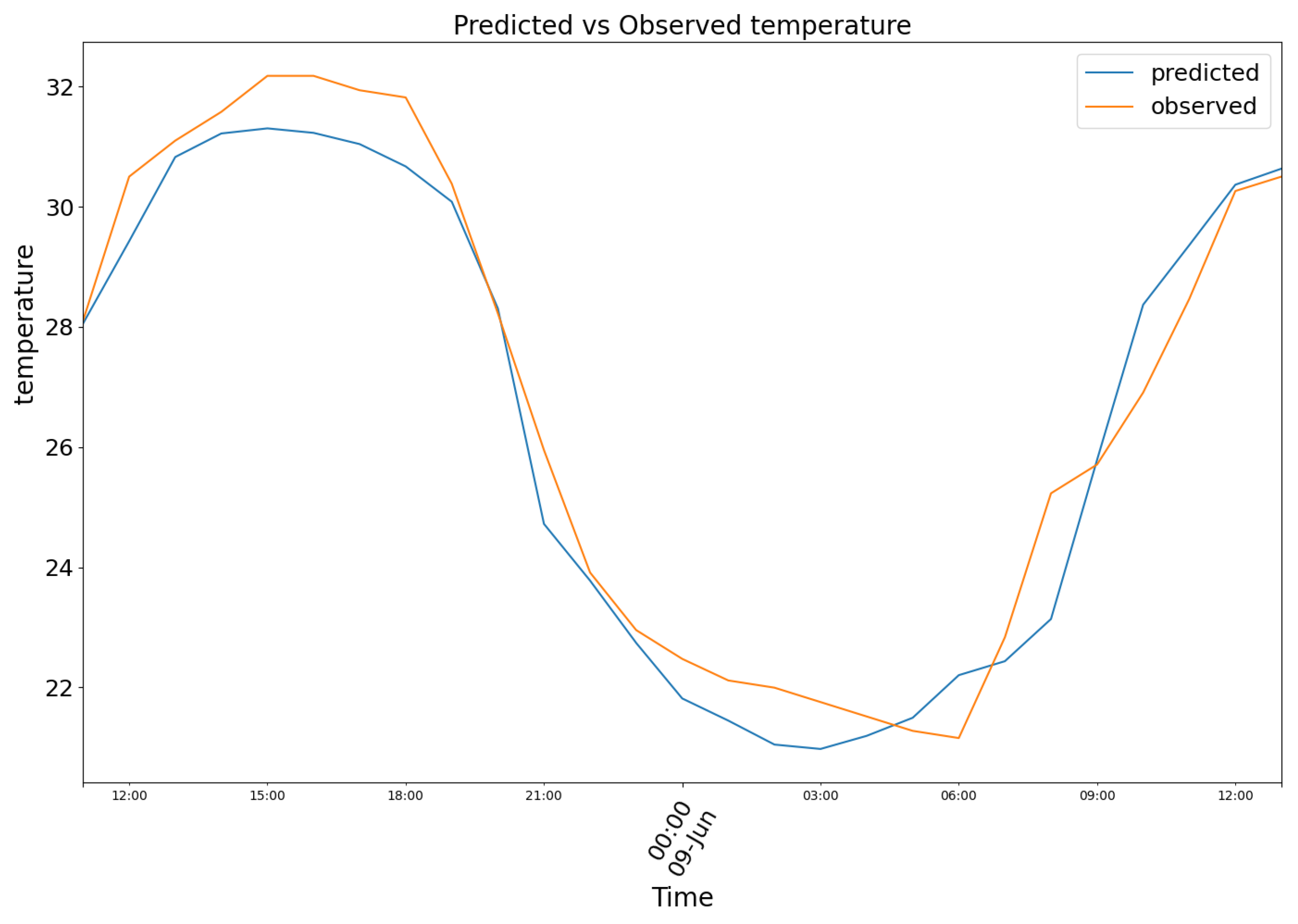

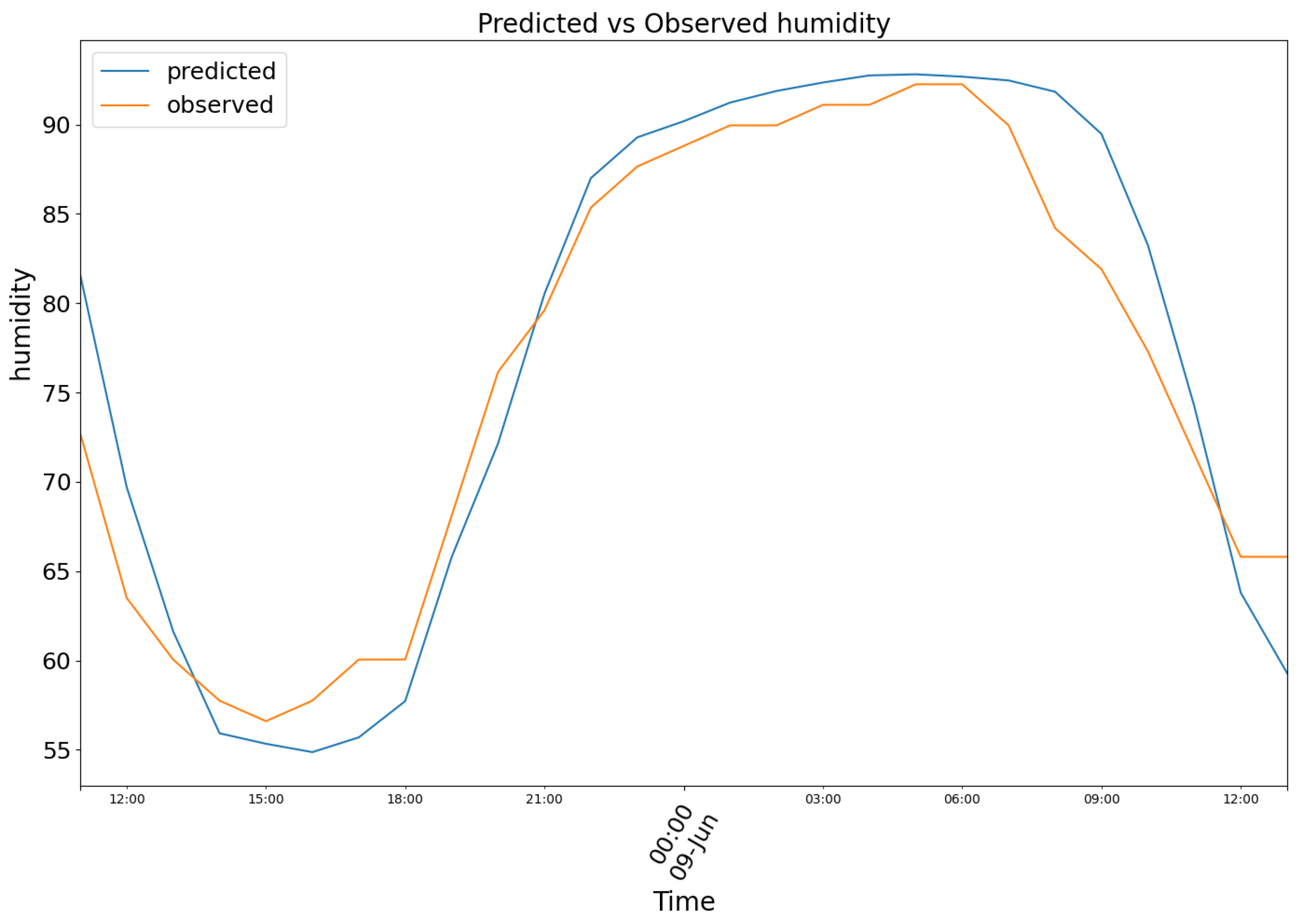

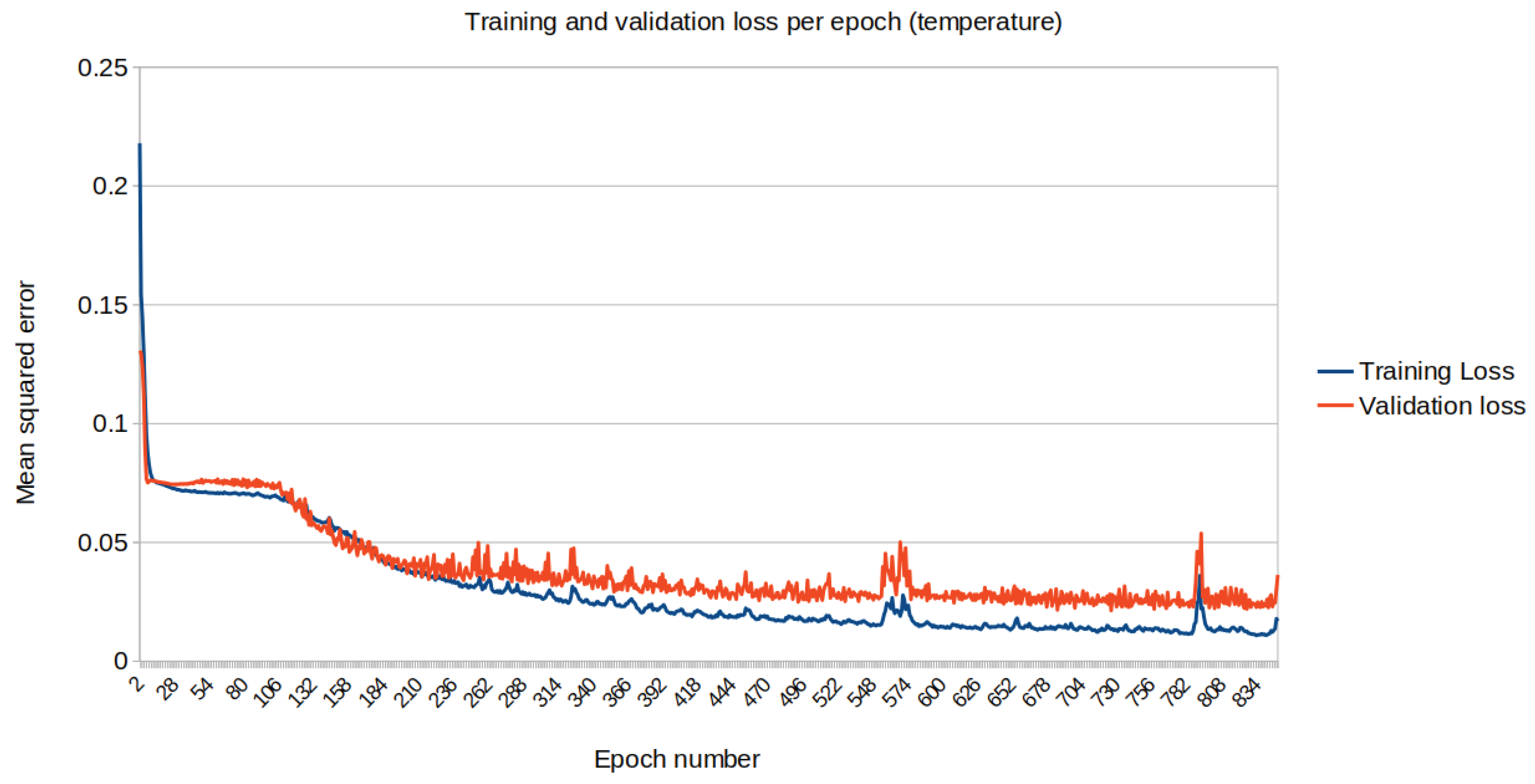

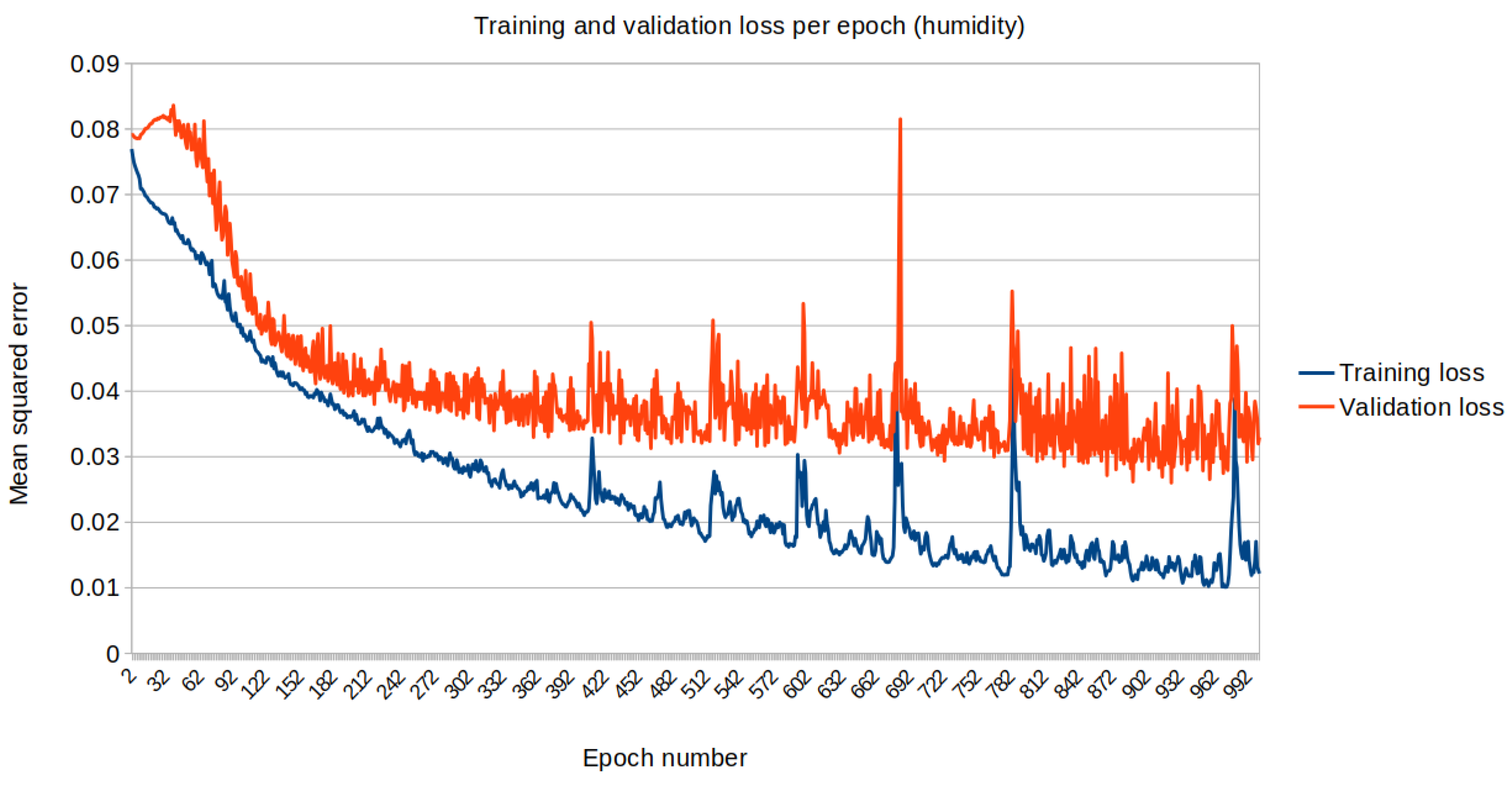

3. Results

4. Conclusions and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaudhary, S.; Bajaj, S.B.; Mongia, S. Analysis of a Novel Integrated Machine Learning Model for Yield and Weather Prediction: Punjab Versus Maharashtra. In: Singh, Y., Verma, C., Zoltán, I., Chhabra, J.K., Singh, P.K. (eds) Proceedings of International Conference on Recent Innovations in Computing. ICRIC 2022. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering 2023, 83-93.

- Covert, M.W.; Gillies, T.E.; Takamasa, K.; Agmon, E. A forecast for large-scale, predictive biology: Lessons from meteorology. Cell Systems 2021, 12, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiolerio, A.; Gagliano, M.; Pilia, S.; Pilia, P.; Vitiello, G.; Dehshibi, M.; Adamatzky, A. Bioelectrical synchronization of Picea abies during a solar eclipse. Royal Society Open Science 2025, 12, 241786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randriamandimbisoa, M.V.; Nany Razafindralambo, N.A.M.; Fakra, D.; Ravoajanahary, D.A.; Gatina, J.C.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N. Electrical response of plants to environmental stimuli: A short review and perspectives for meteorological applications. Sensors International 2020, 1, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Toledo, G.R.A.; Parise, A.G.; Simmi, F.Z.; Costa, A.V.L.; Senko, L.G.S.; Debono, M.-W.; Souza, G.M. Plant electrome: the electrical dimension of plant life. Theoretical and Experimental Plant Physiology 2019, 31, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Dutoit, F.; Najdenovska, E.; Wallbridge, N.; Plummer, C.; Mazza, M.; Raileanu, L.E.; Camps, C. Electrophysiological assessment of plant status outside a Faraday cage using supervised machine learning. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 17073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najdenovska, E.; Dutoit, F.; Tran, D.; Rochat, A.; Vu, B.; Mazza, M.; Camps, C.; Plummer, C.; Wallbridge, N.; Raileanu, L. E. Identifying General Stress in Commercial Tomatoes Based on Machine Learning Applied to Plant Electrophysiology. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlova, E.; Yudina, L.; Sukhova, E.; Sukhov, V. Analysis of Electrome as a Tool for Plant Monitoring: Progress and Perspectives. Plants 2025, 14, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imam, T.; Hasri, A.; Hidetaka, N.; Rofiq, A.R.; Ades, T. Deep learning algorithm for room temperature detection using bioelectric potential of plant data. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2025, 101, 107214. [Google Scholar]

- Cattani, A.; de Riedmatten, L.; Roulet, J.; Smit-Sadki, T.; Alfonso, E.; Kurenda, A.; Graeff, M.; Remolif, E.; Rienth, M. Water status assessment in grapevines using plant electrophysiology. OENO One 2024, 58, 8209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.R.; Papa, J.P.; Rosalin Saraiva, G.F.; Souza, G.M. Automatic classification of plant electrophysiological responses to environmental stimuli using machine learning and interval arithmetic. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2018, 145, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzoli, A.; Jelmini, L.; Pezzatti, G.B.; Jermini, M.; Schumpp, O.; Debonneville, C.; Marcolin, E.; Krebs, P.; Conedera, M. Impact of the “Flavescence Dorée” Phytoplasma on Xylem Growth and Anatomical Characteristics in Trunks of ‘Chardonnay’ Grapevines (Vitis vinifera). Biology 2022, 11, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalman, R.E. New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems. Transactions of the ASME–Journal of Basic Engineering 1960, 82, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gers, F.A.; Schmidhuber, J. Recurrent nets that time and count. Proceedings of the IEEE-INNS-ENNS International Joint Conference on Neural Networks. IJCNN 2000. Neural Computing: New Challenges and Perspectives for the New Millenniu 2000, 3, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Openweather https://openweather.co.uk/accuracy-and-quality.

- Aguila, S.F. , Fuentes Barrios A.; Lorenzo S.L. Evaluation of the Nowcasting and very Short-Range Prediction System of the National Meteorological Service of Cuba. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2021, 8, 36. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).