Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

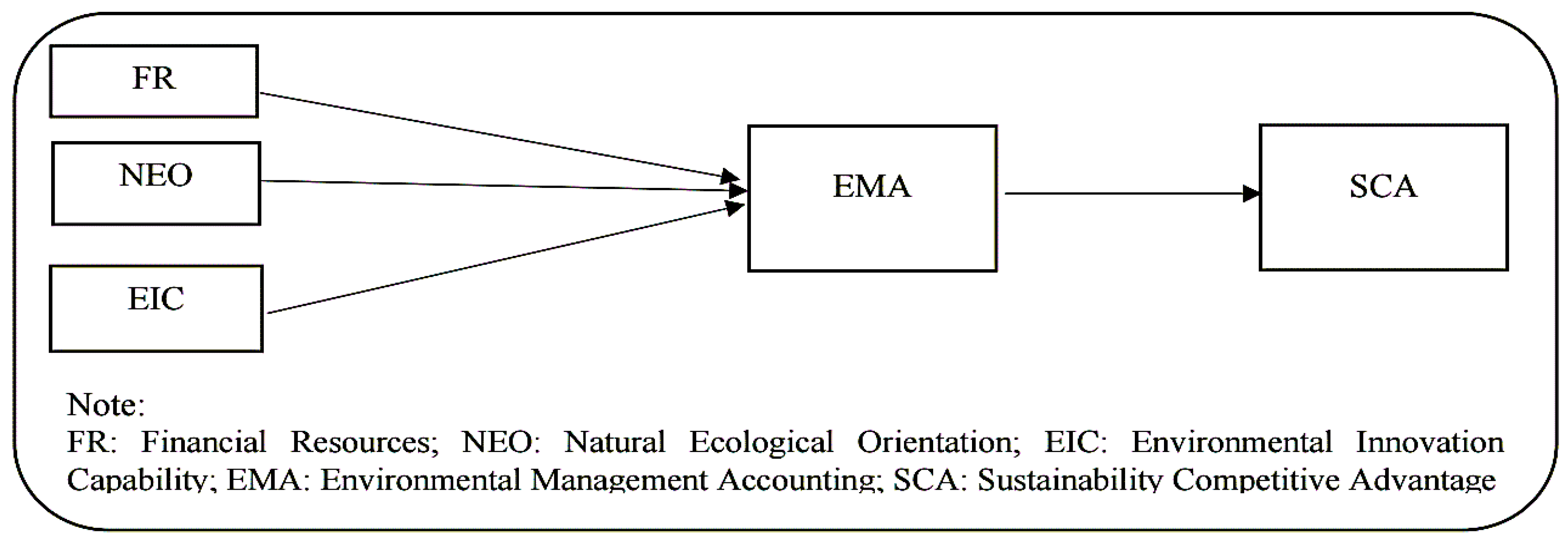

- To examine the direct effect of FR, NEO and EIC on EMA adoption

- To examine the indirect effect of FR, NEO and EIC on SCA through EMA adoption.

- To examine the direct effect of EMA adoption on SCA.

2. Literature Review

EMA Adoption Across Kenyan Manufacturing SMEs

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Natural Resource-Based View

3.2. Financial Resources, EMA and SCA

3.3. Natural Environmental Orientation, EMA and SCA

3.4. Environmental Innovation Capabilities, EMA and SCA

3.5. EMA Adoption and SCA

4. Research Design

4.1. Data and Sampling

4.2. Operationalization of Constructs

| Constructs | Definition | Operationalization | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Resources (FR) | The volume of fund possessed by the companies that can be exploited once they require to finance their investments, capital and current activities | Measured on a Likert scale: 1=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree |

[57] |

| Natural Environmental Orientation (NEO) | An intangible organizational resource that embodies an environmentally conscious organizational culture or strategic orientation, reflecting the firm’s commitment to environmental sustainability and its overarching philosophy of operating in a socially and ecologically responsible manner. | Measured on a Likert scale: 1=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree |

[24], [68] |

| Environmental Innovation Capabilities (EIC) | the application of new, or remarkably improved, products (goods or services), processes, marketing methods, organizational structures and institutional arrangements which, with or without intent, lead to environmental improvements compared to relevant alternatives | Measured on a Likert scale: 1=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree |

[51], [90] |

| Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) | The producing, analysing, and using of financial and non-financial (or monetary and physical) environment-related information, which support firms in relation to resource allocation, cost saving and decision making while simultaneously improving SCA | Measured on a Likert scale: 1=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree |

[2,35,38] |

| Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) | A strategy that creates lasting value for a firm by differentiating it from competitors, making it difficult for others to replicate. It encompasses innovation, quality improvement, cost reduction, and socio-environmental initiatives to secure a dominant market position and enhance market share. | Measured on a Likert scale: 1=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree |

[93] |

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Assessing Psychometric Properties

5.2. Descriptive Statistics

5.3. Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

7.2. Practical Contributions

7.3. Limitations and Scope for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dechezleprêtre, A.; Sato, M. The Impacts of Environmental Regulations on Competitiveness. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2017, 11, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latan, H.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; de S, A.B.L.; Wamba, S.F.; Shahbaz, M. “Effects of environmental strategy, environmental uncertainty and top management’s commitment on corporate environmental performance: The role of environmental management accounting,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 180, pp. 297–306, 2018.

- Agan, Y.; Acar, M.F.; Borodin, A. Drivers of environmental processes and their impact on performance: a study of Turkish SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 51, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoud, M.A.; Fayad, R.; El-Fadel, M.; Kamleh, R. Drivers, barriers and incentives to implementing environmental management systems in the food industry: A case of Lebanon. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Burritt, R.; Chen, J. The potential for environmental management accounting development in China. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2015, 11, 406–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osano, H.M. Global expansion of SMEs: role of global market strategy for Kenyan SMEs. J. Innov. Entrep. 2019, 8, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raga, S.; Mendez-Parra, M.; Velde, D.W.T. “Overview of trade between Kenya and the European Union (EU) ODI-FSD Kenya emerging analysis series Series Key messages,” no. December, 2021, [Online]. Available: www.odi.org/publications/overview-of-trade-.

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. “A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after,” J. Manag., vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 1464–1479, 2011.

- Desouza, P. Air pollution in Kenya: a review. Air Qual. Atmosphere Heal. 2020, 13, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macharia, K.K.; Gathiaka, J.K.; Ngui, D. Energy efficiency in the Kenyan manufacturing sector. Energy Policy 2022, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Moulang, C.; Hendro, B. Environmental management accounting and innovation: an exploratory analysis. Accounting, Audit. Account. J. 2010, 23, 920–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, A.N.; Lee, K.; Kaluarachchilage, P.K.H. Institutional pressures, environmental management strategy, and organizational performance: The role of environmental management accounting. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 30, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, J.-F.; Journeault, M. Eco-control: The influence of management control systems on environmental and economic performance. Accounting, Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, G.M.; Amores-Salvadó, J.; Navas-López, J.E. Environmental Management Systems and Firm Performance: Improving Firm Environmental Policy through Stakeholder Engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 23, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiaei, K.; Bontis, N.; Alizadeh, R.; Yaghoubi, M. Green intellectual capital and environmental management accounting: Natural resource orchestration in favor of environmental performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 31, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, N.; Lee, K.-H. Corporate cleaner production strategy development and environmental management accounting: A contingency theory perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, K.M.; Amir, A.M.; Maelah, R.; Jalaludin, D. Effects of institutional pressures, organisational resources, and capabilities on environmental management accounting for sustainability competitive advantage. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2023, 24, 1284–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.A.S.; Waghule, S.N.; Hasan, M.B. Linking environmental management accounting to environmental performance: the role of top management support and institutional pressures. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamasak, R. “The contribution of tangible and intangible resources, and capabilities to a firm’s profitability and market performance,” Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 252–275, 2017.

- Christ, K.L.; Burritt, R.L. Environmental management accounting: the significance of contingent variables for adoption. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 41, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H. Factors affecting the implementation of environmental management accounting: A case study of pulp and paper manufacturing enterprises in Vietnam. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B. Corporate environmentalism: the construct and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keszey, T. Environmental orientation, sustainable behaviour at the firm-market interface and performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K.; Ma, K.H.Y. Environmental Orientation of Exporting SMEs from an Emerging Economy: Its Antecedents and Consequences. Manag. Int. Rev. 2016, 56, 597–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Huo, B. The impact of environmental orientation on supplier green management and financial performance: The moderating role of relational capital. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schriber, S.; Löwstedt, J. Tangible resources and the development of organizational capabilities. Scand. J. Manag. 2015, 31, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, R.D.; Hansen, D.R. Ecoefficiency: Defining a role for environmental cost management. Account. Organ. Soc. 2007, 33, 551–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Hoejmose, S.; Marchant, K. “Environmental Management in SMEs in the UK: Practices, Pressures and Perceived Benefits,” Bus. Strategy Environ., vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 423–434, 2012.

- Newbert, S.L. Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: an assessment and suggestions for future research. Strat. Manag. J. 2006, 28, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassells, S.; Lewis, K.V. Environmental management training for micro and small enterprises: the missing link? J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2017, 24, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M. Innovation capability in SMEs: A systematic review of the literature. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, P.G.; Mathias, M.A.S.; da Rocha, A.B.T.; de Oliveira, O.J. “Understanding and implementing environmental management in small entrepreneurial ventures: supply chain management, production and design,” J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev., vol. 30, no. 7, pp. 1445–1475, 2023.

- Jalaludin, D.; Sulaiman, M.; Ahmad, N.N.N. “Environmental management accounting: an empirical investigation of manufacturing companies in Malaysia,” J. Asia-Pac. Cent. Environ. Account., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 31–45, 2010.

- Solovida, G.T.; Latan, H. Linking environmental strategy to environmental performance: Mediation role of environmental management accounting. Sustain. Accounting, Manag. Policy J. 2017, 8, 595–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, J. Exploring the effects of institutional pressures on the implementation of environmental management accounting: Do top management support and perceived benefit work? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 28, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungai, E.M.; Ndiritu, S.W.; Rajwani, T. Do voluntary environmental management systems improve environmental performance? Evidence from waste management by Kenyan firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yale Universit Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy, “Environmental Performance Index Ranking country performance on sustainability issues.” 2022.

- Jamil, C.Z.M.; Mohamed, R.; Muhammad, F.; Ali, A. Environmental Management Accounting Practices in Small Medium Manufacturing Firms. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, K.M.; Amir, A.M.; Sulaiman, M. Material Flow Cost Accounting, Perceived Ecological Environmental Uncertainty, Supplier Integration and Business Performance: A Study of Manufacturing Sector in Malaysia. Asian J. Account. Gov. 2017, 8, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J.; Hansen, E.G. Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H. “Why and how to adopt green management into business organizations?: The case study of Korean SMEs in manufacturing industry,” Manag. Decis., vol. 47, no. 7, pp. 1101–1121, 2009.

- Hart, S.L. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvado, J.A.; de Castro, G.M.; Lopez, J.E.N.; Verde, M.D. Environmental innovation and firm performance: A natural resource-based view. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Darnall, N.; Edwards, D. “Predicting the cost of environmental management system adoption: The role of capabilities, resources and ownership structure,” Strateg. Manag. J., vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 301–320, 2006.

- Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: a longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strat. Manag. J. 2004, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Bennett, M.; Burritt, R.L.; Jasch, C. Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) as a Support for Cleaner Producion. Springer, Dordrecht., 2008. [CrossRef]

- Sari, R.N.; Pratadina, A.; Anugerah, R.; Kamaliah, K.; Sanusi, Z.M. Effect of environmental management accounting practices on organizational performance: role of process innovation as a mediating variable. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2020, 27, 1296–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derchi, G.B.; Burkert, M.; Oyon, D. Environmental management accounting systems: A review of the evidence and propositions for future research. Stud. Manag. Financ. Account. 2013, 26, 197–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasch, C. Environmental and Material Flow Cost Accounting: principles and procedures, vol. 53, no. 9. Springer Science & Business Media., 2008.

- Cainelli, G.; De Marchi, V.; Grandinetti, R. Does the development of environmental innovation require different resources? Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 94, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, P.S.; Blome, C.; Schleper, M.C.; Subramanian, N. Supply chain collaboration and eco-innovations: An institutional perspective from China. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 2734–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. “Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage,” J. Manag., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 99–120, 1991.

- Pe, E.A.; Ruiz, C.C.; Fenech, F.C. “Environmental management systems as an embedding mechanism: a research note,” Account. Audit. Account. J., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 403–422, 2007.

- Russo, M.V.; Fouts, P.A. “A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental performance and profitability,” Acad. Manage. J., vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 534–559, 1997.

- Journeault, M. The Influence of the Eco-Control Package on Environmental and Economic Performance: A Natural Resource-Based Approach. J. Manag. Account. Res. 2016, 28, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.U.; Anwar, M.; Li, S.; Khattak, M.S. Intellectual capital, financial resources, and green supply chain management as predictors of financial and environmental performance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19755–19767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, B.; Chadee, D. Environmental sustainability orientation and financial resources of small manufacturing firms in the Philippines. Soc. Responsib. J. 2012, 8, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, M.S.; Wu, Q.; Ahmad, M. Influence of financial resources on sustainability performance of SMEs in emerging economy: The role of managerial and firm level attributes. Bus. Strat. Dev. 2023, 6, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerva, M.C.; Triguero-Cano, Á.; Córcoles, D. Drivers of green and non-green innovation: empirical evidence in Low-Tech SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 68, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Leonidou, C.N.; Fotiadis, T.A.; Zeriti, A. Resources and capabilities as drivers of hotel environmental marketing strategy: Implications for competitive advantage and performance. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-C.; Deegan, C. “Environmental Management Accounting and Environmental Accountability Within Universities: Current Practice and Future Potential,” Environ. Manag. Account. Clean. Prod., p. (pp. 301-320), 2008.

- Singh, M.; Brueckner, M.; Padhy, P.K. Environmental management system ISO 14001: effective waste minimisation in small and medium enterprises in India. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 102, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniskis, J.K.; Stasiskiene, Z. “Environmental management accounting in Lithuania: exploratory study of current practices, opportunities and strategic intents,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 14, no. 14, pp. 1252–1261, 2006.

- Othman, R.; Arshad, R.; Aris, N.A.; Arif, S.M.M. Organizational Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage of Cooperative Organizations in Malaysia. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M. Direct and indirect effects of eco-innovation, environmental orientation and supplier collaboration on hotel performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, B.; Ozanne, L.K. “Challenges of the ‘“green imperative”’: a natural resource-based approach to the environmental orientation–business performance relationship,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 58, pp. 430–438, 2005.

- Kang, Y.; He, X. Institutional Forces and Environmental Management Strategy: Moderating Effects of Environmental Orientation and Innovation Capability. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2018, 14, 577–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K.; He, H.; Kai, H.; Wang, W.Y.C. “Industrial Marketing Management Environmental orientation and corporate performance: The mediation mechanism of green supply chain management and moderating effect of competitive intensity,” Ind. Mark. Manag., vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 621–630, 2012.

- Tatoglu, E.; Bayraktar, E.; Arda, O.A. Adoption of corporate environmental policies in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, K.H.; Theyel, G.; Wood, C.H. Identifying Firm Capabilities as Drivers of Environmental Management and Sustainability Practices – Evidence from Small and Medium-Sized Manufacturers. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2012, 21, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M. Innovation capability in achieving higher performance: perspectives of management and employees. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2016, 29, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, K.; Sloan, T. Firm size and its impact on continuous improvement. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2011, 56, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M.; Ukko, J. “Facilitating innovation capability through performance measurement: A study of Finnish SMEs,” Manag. Res. Rev., vol. 36, no. 10, pp. 991–1010, 2013.

- Castela, B.M.; Ferreira, F.A.; Ferreira, J.J.; Marques, C.S. Assessing the innovation capability of small- and medium-sized enterprises using a non-parametric and integrative approach. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 1365–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. “A Framework Linking Intangible Resources and Capabilities to Sustainble Competitve Advantage,” Strateg. Manag. J., vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 607–618, 1993.

- Porter, M.E. “Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors.,” Compet. Strategy N. Y. Free, 1980.

- Do, B.; Nguyen, N. “The Links between Proactive Environmental Strategy, Competitive Advantages and Firm Performance : An Empirical Study in Vietnam,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 12, p. 4962, 2020.

- Junquera, B.; Barba-Sánchez, V. Environmental Proactivity and Firms’ Performance: Mediation Effect of Competitive Advantages in Spanish Wineries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. “The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility,” Harv. Bus. Rev., vol. 84, no. 12, pp. 78–92, 2006.

- Gunarathne, N.; Lee, K.-H. “Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) for Environmental Management and Organizational Change: An Eco Control Approach,” J. Account. Organ. Change, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 362–383, 2015.

- Jasch, C. Environmental management accounting (EMA) as the next step in the evolution of management accounting. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Mail and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, no. 133. 2014.

- Banerjee, S.B.; Iyer, E.S.; Kashyap, R.K. Corporate Environmentalism: Antecedents and Influence of Industry Type. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, F.; Eskander, S.M.; Fankhauser, S.; Diop, M. How do African SMEs respond to climate risks? Evidence from Kenya and Senegal. World Dev. 2018, 108, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, J.-F.; Boiral, O.; Roy, M.-J. The Tracking of Environmental Costs: Motivations and Impacts. Eur. Account. Rev. 2013, 23, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, J.-F.; Boiral, O.; Roy, M.-J. Strategic cost management and performance: The case of environmental costs. Br. Account. Rev. 2016, 48, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2011.

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. “Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research,” Eur. Bus. Rev., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 106–121, 2014.

- Pondeville, S.; Swaen, V.; De Rongé, Y. Environmental management control systems: The role of contextual and strategic factors. Manag. Account. Res. 2013, 24, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Othman, M.S.H.; Saeidi, P. The moderating role of environmental management accounting between environmental innovation and firm financial performance. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2018, 19, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. F. of Accountants [IFAC, “International Guidance Document,” Environ. Manag. Account., no. New York: USA., 2005.

- Burritt, R.L.; Hahn, T.; Schaltegger, S. “Towards a Comprehensive Framework for Environmental Management Accounting -Links Environmental Management Accounting Tools Between Business Actors and,” Aust. Account. Rev., vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 39–50, 2002.

- De Guimarães, J.C.F.D.; Severo, E.A.; de Vasconcelos, C.R.M. “The influence of entrepreneurial, market, knowledge management orientations on cleaner production and the sustainable competitive advantage,” J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1653–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylinen, M.; Gullkvist, B. The effects of organic and mechanistic control in exploratory and exploitative innovations. Manag. Account. Res. 2014, 25, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. “The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In Marcoulides G. A. (Ed.),” Mod. Methods Bus. Res., vol. 295, no. 2, pp. 295–336, 1998.

- Chin, W.W. “How to Write Up and Report PLS Analyses,” in Handbook of Partial Least Squares, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Wijethilake, C. Proactive sustainability strategy and corporate sustainability performance: The mediating effect of sustainability control systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 196, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarros, J.C.; Gray, J.; Densten, I.L.; Cooper, B. The Organizational Culture Profile Revisited and Revised: An Australian Perspective. Aust. J. Manag. 2005, 30, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schriesheim, C.A.; Powers, K.J.; Scandura, T.A.; Gardiner, C.C.; Lankau, M.J. Improving Construct Measurement In Management Research: Comments and a Quantitative Approach for Assessing the Theoretical Content Adequacy of Paper-and-Pencil Survey-Type Instruments. J. Manag. 1993, 19, 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. , Research Method for Business: A skill Building Approach, 7th edition. Wiley & Son Ltd., 2013.

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. , A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM)., 2nd Edition. Sage publications, 2017.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Wang, Y.-M.; Wu, T.-W.; Wang, P.-A. An Empirical Analysis of the Antecedents and Performance Consequences of Using the Moodle Platform. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2013, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. “Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies,” Strateg. Manag. J., vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 195–204, 1999.

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. , Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge, 1988.

- Carrión, G.C.; Nitzl, C.; Roldán, J.L. “Mediation analyses in partial least squares structural equation modeling: Guidelines and empirical examples,” Partial Least Sq. Path Model. Basic Concepts Methodol. Issues Appl., pp. 173–195, 2017.

- Ye, J.; Kulathunga, K.M.M.C.B. How Does Financial Literacy Promote Sustainability in SMEs? A Developing Country Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, T.-Y.; Chan, H.K.; Lettice, F.; Chung, S.H. The influence of greening the suppliers and green innovation on environmental performance and competitive advantage in Taiwan. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2011, 47, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The Brundtland Report from the World Commission on Economic Development (WCED) defines sustainable development as fulfilling current needs without hindering future generations from fulfilling their own needs [45]. |

| 2 |

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Company’s year of establishment, | 0-5 | 21 | 10% |

| Between 5-10 | 39 | 19% | |

| Between 10-20 | 57 | 28 | |

| More than 20 | 89 | 43% | |

| Management Level | Junior management | 19 | 9.2% |

| Middle management | 89 | 43.2% | |

| Top management | 98 | 47.6% | |

| Experience Year | Less than a year | 5 | 2.4% |

| 1 - 5 years | 67 | 32.5% | |

| 6 - 10 years | 71 | 34.5% | |

| 11 - 20 years | 47 | 22.8% | |

| More than 20 years | 16 | 7.8% | |

| Type of Industries | Food | 101 | 49% |

| Metal | 11 | 5% | |

| Textiles | 18 | 8.5% | |

| Machinery | 1.5 | 1% | |

| Chemical | 5.5 | 2.5% | |

| Furniture | 3 | 1.5% | |

| Automobile | 1 | 1% | |

| Others | 65 | 31.5% | |

| Company Export Regions | Africa | 11 | 5.3% |

| Europe | 179 | 86.9% | |

| North America | 14 | 6.8% | |

| South America | 2 | 1% | |

| Export Share to Europe | KES 6 - 50 million | 50 | 24.3% |

| KES 51 - 1000 million | 156 | 75.7% |

| Construct | …+Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR | …+FR1 | 0.679 | 0.898 | 0.817 | 0.892 | 0.639 |

| …+FR2 | 0.570 | |||||

| …+FR3 | 0.753 | |||||

| …+FR4 | 0.681 | |||||

| …+FR5 | 0.731 | |||||

| …+FR6 | 0.699 | |||||

| …+FR7 | 0.996 | |||||

| NEO | …+NEO3 | 0.618 | 0.804 | 0.828 | 0.779 | 0.431 |

| …+NEO4 | 0.750 | |||||

| …+NEO5 | 0.760 | |||||

| …+NEO6 | 0.727 | |||||

| …+NEO7 | 0.577 | |||||

| …+NEO8 | 0.591 | |||||

| EIC | …+EIC1 | 0.584 | 0.810 | 0.817 | 0.813 | 0.434 |

| …+EIC2 | 0.574 | |||||

| …+EIC3 | 0.624 | |||||

| …+EIC4 | 0.654 | |||||

| …+EIC5 | 0.549 | |||||

| …+EIC6 | 0.621 | |||||

| …+EIC7 | 0.650 | |||||

| …+EIC8 | 0.503 | |||||

| EMA | …+EMA1 | 0.501 | 0.894 | 0.901 | 0.885 | 0.416 |

| …+EMA2 | 0.636 | |||||

| …+EMA3 | 0.603 | |||||

| …+EMA4 | 0.688 | |||||

| …+EMA5 | 0.669 | |||||

| …+EMA6 | 0.646 | |||||

| …+EMA7 | 0.593 | |||||

| …+EMA8 | 0.728 | |||||

| …+EMA9 | 0.601 | |||||

| …+EMA10 | 0.567 | |||||

| …+EMA11 | 0.570 | |||||

| …+EMA12 | 0.631 | |||||

| …+EMA13 | 0.808 | |||||

| …+EMA14 | 0.682 | |||||

| …+SCA1 | 0.661 | 0.739 | 0.747 | 0.740 | 0.493 | |

| …+SCA2 | 0.565 | |||||

| SCA | …+SCA3 | 0.658 | ||||

| …+SCA4 | 0.502 | |||||

| …+SCA5 | 0.623 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EIC | 0.659 | ||||

| 2. EMA | 0.430 | 0.645 | |||

| 3. FR | 0.374 | 0.215 | 0.799 | ||

| 4. NEO | 0.424 | 0.450 | 0.263 | 0.657 | |

| 5. SCA | 0.419 | 0.223 | 0.288 | 0.170 | 0.702 |

| Variables | Actual Range | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | |||

| FR | 1 | 5 | 3.916 | 0.895 |

| NEO | 1 | 5 | 4.262 | 0.706 |

| EIC | 1 | 5 | 4.120 | 0.692 |

| EMA | 1 | 5 | 4.247 | 0.635 |

| SCA | 1 | 5 | 3.847 | 0.816 |

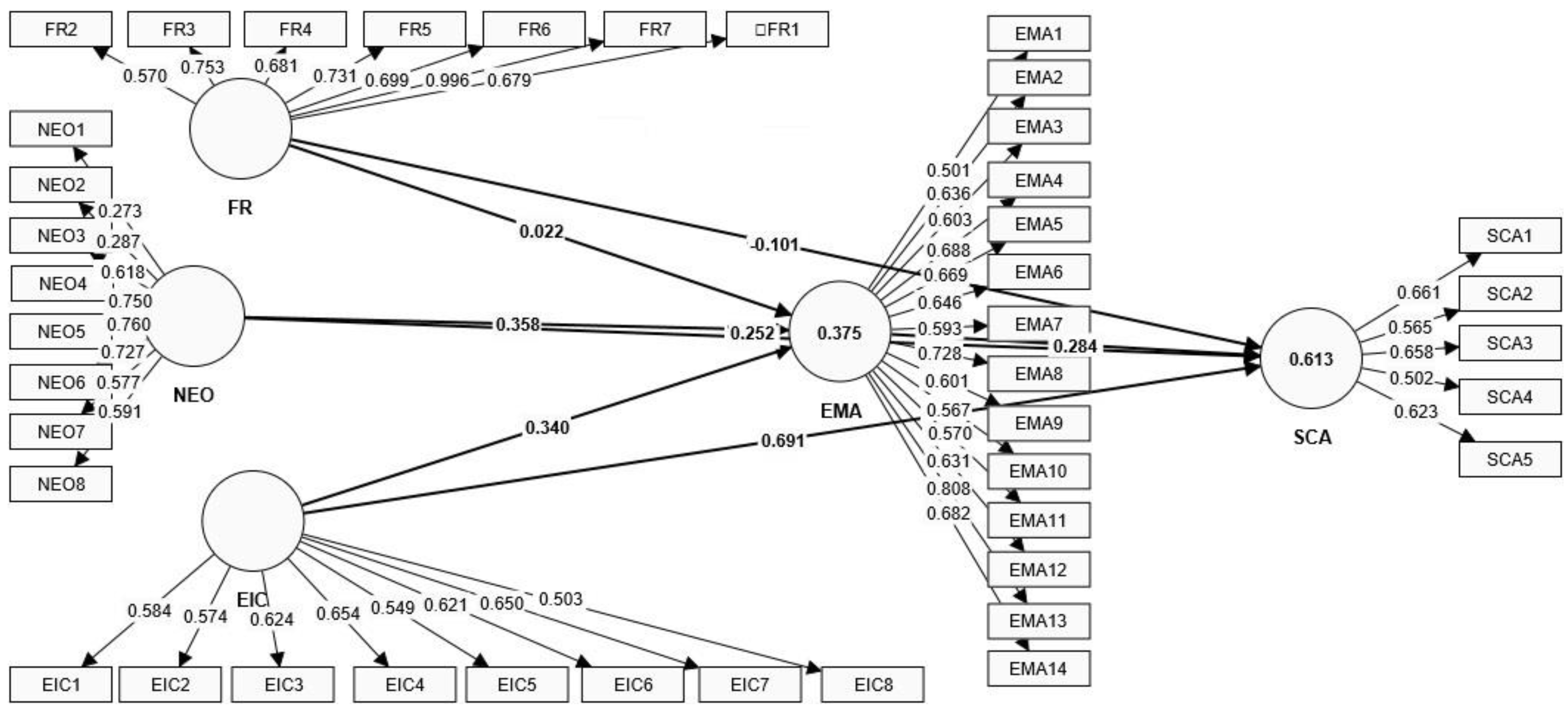

| Constructs | Standardized Coefficients | Collinearity Statistics VIF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR | 0.022 | 1.337 | ||

| NEO | 0.358 | 1.311 | ||

| EIC | 0.340 | 1.645 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Coef (ß) | T-Value | P-value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1(a) | FR -> EMA | 0.022 | 0.249 | 0.804 | Not Supported |

| H2(a) | NEO-> EMA | 0.358** | 4.859 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3(a) | EIC-> EMA | 0.340** | 4.536 | 0.003 | Supported |

| H4 | EMA-> SCA | 0.284** | 3.199 | 0.000 | Supported |

| R2 | EMA | 0.375 | |||

| R2 | SCA | 0.613 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Coef (ß) | T-Value | P-value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1(b) | FR -> EMA -> SCA | -0.101 | 0.824 | 0.410 | Not Supported |

| H2(b) | NEO-> EMA -> SCA | 0.252** | 2.768 | 0.006 | Supported |

| H3(b) | EIC-> EMA -> SCA | 0.691** | 6.378 | 0.000 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).