INTRODUCTION

Partial nephrectomy is considered the gold standard for treating localized renal tumors and diseased renal tissue, as it’s been shown to have favorable outcomes related to overall mortality and cancer-specific mortality relative to radical nephrectomy. [

1,

2] Aside from providing beneficial oncological outcomes, another key objective of partial nephrectomy is to preserve healthy renal tissue and its associated function and ultimately lower the incidence of postoperative chronic kidney disease.[

3] Nonetheless, a postoperative decline in renal function is expected after partial nephrectomy due to loss of nephron mass related to parenchymal excision or ischemic/ inflammatory insult. [

4] Hence, preventive measures to minimize surgical insult, nephron deficiency, and loss of kidney function are warranted to fully optimize patient outcomes.

Amniotic membrane (AM) is the innermost layer of the placenta that enwraps and protects the fetus during pregnancy. This biological tissue is known to possess anti-inflammatory, anti-scarring, and pro-regenerative properties that are important for fetal development, and subsequently has been used clinically in many medical specialties to promote healing in patients with wounds.[

5] For example, AM is commonly applied in ophthalmology to promote healing without scar formation in patients with superficial ocular surface wounds and its also been used in podiatry as a wound covering to promote healing in patients with chronic foot ulcers that are non-responsive to conservative care.[

5] In urology, AM has also been used in many applications such as bilateral nerve-sparing prostatectomy, interstitial cystitis, along the suture line during bladder reconstruction, and after ureterolysis as a ureteral wrap.[

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] In particular, adjunctive application of AM has been shown to expediate postoperative functional recovery after robot-assisted prostatectomy when placed over the neurovascular bundle due to its anti-inflammatory and anti-scarring properties.[

6,

7] As excessive inflammation is known to result in scar formation and potentially loss of kidney function,[

11,

12,

13] it was hypothesized that adjunctive use of AM applied on the excision site during partial nephrectomy could help reduce inflammation and scarring ultimately preserving renal function. We herein assessed the adjunctive use of AM to preserve function after robotic partial nephrectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective medical chart review was conducted at a single-center on high-risk patients who underwent partial nephrectomy with cryopreserved ultra-thick AM allograft from August 2021 and August 2024. Patients were considered high-risk if they had pre-operative GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, a solitary kidney, or multiple comorbidities increasing peri- and post-operative risk. Patients were eligible for inclusion in this study if they had clinically diagnosed localized tumors, underwent partial nephrectomy with cryopreserved ultra-thick AM allograft between the specified timeframe, and had at least 1 month of follow-up data. Patients were excluded if they had distant metastasis and lymph node metastasis. The study was reviewed by the Sterling Institutional Review Board (Atlanta, GA) and was determined to be exempt under 45 CFR §46.104(d). Patient consent was waived under Category 4 Exemption (DHHS).

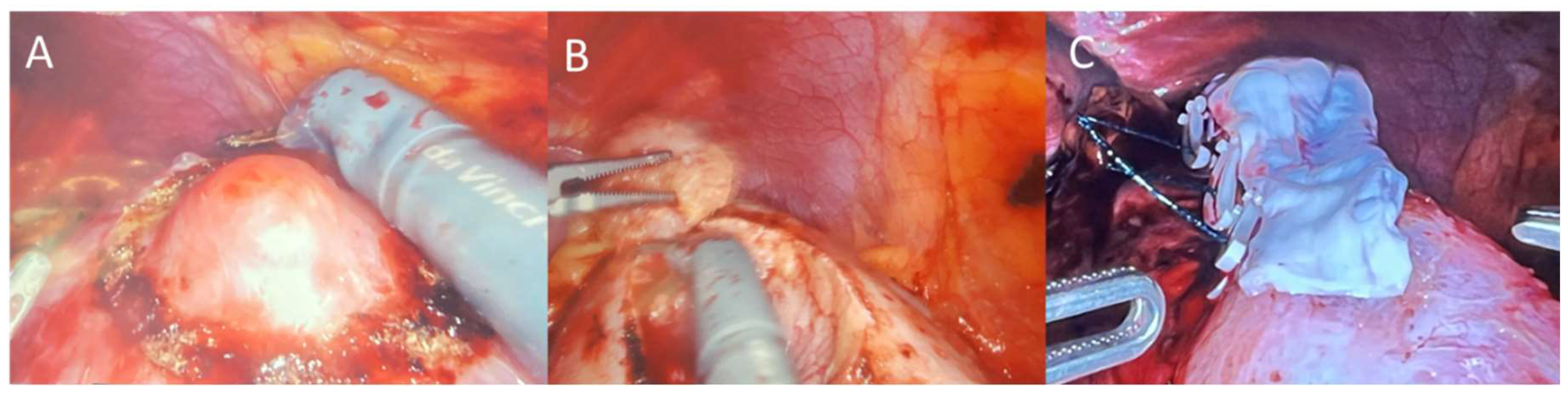

All partial nephrectomy procedures were performed by one surgeon using the four-arm da Vinci surgical system (Intuitive Surgical; Sunnyvale, CA, USA) using a similar technique for each patient as previously described.[

14] In brief, the patient is placed in the flank position, table is flexed, insufflation is performed, robotic trocars are placed (shifted laterally for obese patients), colon was reflected to allow access to retroperitoneum, peritoneum was incised, blunt dissection was performed to locate and expose the diseased tissue on the kidney, the area around the tumor was marked circumferentially by cautery, ultrasound and indocyanine green were used to confirm the tumor margin was appropriately demarcated, renal artery was clamped, tumor was excised, parenchymal defect was closed every 1 cm with 3-0 sutures with a clip to sandwich close the renal parenchyma for hemostasis, and artery was unclamped. A 6x3 cm pre-hydrated AM graft (BioTissue, Miami, FL, USA) was then taken from its sterile packaging under strict aseptic conditions and rinsed with saline, introduced through the 12mm trocar, placed over the renal incision as a barrier with Small Graptor (grasping retractor) and ProGrasp forceps (Intuitive Surgical; Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and secured in place using fibrin hemostat spray (

Figure 1). Diseased renal tissue was extracted, drain placed, trocars removed, and wounds were closed with sutures.

Data collected from the medical charts included demographic information, significant medical history including co-morbidities, tumor location, warm ischemia times, blood loss, excised tissue size, excised tissue pathology, and renal functional outcomes of Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) and serum creatinine levels, which were evaluated pre-operatively and up to 36-months post-operatively. The incidence of cancer recurrence and complications were also assessed. The primary outcome measure was the change in renal function (i.e. GFR and creatinine) at follow-up compared to baseline. Adverse events were further classified if they were procedure related or product related.

Outcomes were analyzed between groups using the Student’s t test for continuous factors and the Chi-Square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical factors. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v. 20.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL, USA). A p value < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

A total of 40 subjects (21 female; 19 male) met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis. The subjects had an average age of 67.9 ± 9.8 years and were predominantly overweight or obese (80% of subjects) with an average body mass index of 30.9 ± 6.8 lbs/in

2. Only 2 subjects (5%) mentioned a family history of kidney cancer. Additional demographic information can be found in

Table 1. The mean GFR and creatinine levels at baseline were 73.4 ± 20.1 ml/min and 1.03 ± 0.51 mg/dl, respectively. Eight (20%) subjects had a GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m

2 prior to the surgery.

A total of 41 partial nephrectomy procedures were performed on the left (n=21) or right (n=20) kidney of the forty subjects (1 subject had surgery on both kidneys). Surgery was uneventful in all cases, with an average warm ischemia time of 11.9 ± 2.0 min and average blood loss of 63.7 ± 51.1ml. The average specimen weight was 15.2 ± 13.4 g and average specimen volume was 27.8 ± 30.8 cm3. A positive surgical margin was only noted in 2 (5%) cases.

To assess the change in renal function, GFR and creatinine levels were compared between preoperative and postoperative visits (

Figure 2). GFR was noted to slightly decline 6.6 ± 11.3 ml/min at 1 month, but stayed relatively constant thereafter with an average change of -9.4 ± 13.3 ml/min at 6 months, -3.9 ± 12.1 ml/min at 12 months, -5.1 ± 17.8 ml/min at 24 months, and -4.0 ± 11.2 ml/min at 36 months compared to preoperative GFR. Similarly, the average change in creatinine slightly increased 0.086 ± 0.163 mg/dl at 1 month and 0.183 ± 0.263 mg/dl at 6 months, but declined thereafter 0.116 ± 0.251 mg/dl at 12 months, 0.094 ± 0.220 mg/dl at 24 months, and 0.081 ± 0.130 mg/dl at 36 months when compared to preoperative creatinine levels.

No complications were observed attributable to the application of AM, although 2 (5%) patients had urinary tract infection within 1 month and 3 (8%) subjects had reduced libido postoperative. No re-admissions or cancer recurrence occurred.

DISCUSSION

Renal function preservation is a key aim following partial nephrectomy. Although partial nephrectomy offers oncologic benefits by allowing nephron-sparing surgery in patients with localized renal tumors, incomplete recovery of nephrons is a significant risk which can lead to long-term renal impairment. Studies have shown a decline in renal function of approximately 20% in the operated kidney and 10% globally for patients after partial nephrectomy.[

4] In order to help minimize loss of renal function and expediate recovery, additional nephron-sparing techniques such as avoiding prolonged warm ischemia, using hemostatic agents, and preserving as much of the normal functional parenchyma as possible are commonly employed. Building off that notion, our findings further suggest that the use of AM as a biological membrane over the renal incision during partial nephrectomy may help contribute to improved healing, better functional preservation, and a reduced risk of postoperative complications as evidenced by maintained serum creatinine and GFR levels and lack of adverse events including arteriovenous malformations, urine leakage, urinary fistulas, and ureteral stricture formation in patients with low GFR levels preoperatively (73.4 ± 20.1 ml/min). These findings align with prior studies in other surgical models, where AM has been shown to promote significantly faster healing of surgical-incisional wounds and expedite recovery of function after prostatectomy in particular in patients with high-risk for poor wound healing.[

6,

15]

The AM has long been recognized for its pro-regenerative properties, including anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and pro-vasculogenic effects. These attributes make it an attractive adjunctive measure for use in renal surgery, where the preservation of kidney function and the prevention of scarring are critical. Previous studies have shown that AM contains growth factors and extracellular matrix components including Heavy Chain- Hyaluronic Acid/ Pentraxin 3 (HC-HA/PTX3), which have been shown to be key for its therapeutic benefits to help mitigate inflammatory responses and promote healing.[

5,

16] This is important during and after partial nephrectomy as surgical insult damages cells which release pro-inflammatory cytokines and leads to influx of neutrophils and macrophages inflammatory cells to clear debris and aid in activating surrounding cells. [

11] The nearby fibroblasts, endothelial, mesenchymal and epithelial cells then work to promote vasculature network and repair the damaged tissue.[

11] However, abnormal and persistent inflammation may lead to scar formation and progressive renal disease.[

11] To help prevent such circumstances from occurring, AM has been shown to promote apoptosis of pro-inflammatory cells, reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, and prevent differentiation of pro-scarring myofibroblasts by downregulating transforming growth factor-β.[

5] The HC-HA/PTX3 within AM has also been shown to de-differentiate myofibroblasts and return the cells to their normal function which would facilitate regeneration rather than fibrosis.[

17] Collectively the properties may help support the regeneration of renal parenchyma, particularly in the setting of partial nephrectomy, where the remaining kidney tissue must adapt to a reduced functional mass.

Although our findings suggest that partial nephrectomy with adjunctive AM was safe and associated with beneficial clinical outcomes, the interpretation of results are limited by the retrospective design and lack of a control group. There may also be selection bias and the results are not representative of the general population. It is possible the renal function may have been preserved without use of AM or without a significant removal or devascularization of nephrons. Albeit our results compare favorably to other findings published in the literature. Limitations on the adjunctive use of AM would also be lack of accessibility and cost of the tissue, which may limit clinical adoption. Further prospective, controlled studies are needed to establish cost-effectiveness. Furthermore, although no cancer recurrence was noted in our series and a few preliminary studies have suggested AM has the potential to reduce tumorigenicity,[

18] further long-term studies are warranted to monitor recurrence rates. Similar long-term studies evaluating AM during prostatectomy have shown no increased recurrence rates.[

6,

19] No recurrence was noted in our series despite a positive surgical margin rate of 5%, which compares favorably with the reported rates of 0.1-10.7% in contemporary robotic partial nephrectomy series.[

20] Further studies are also warranted to understand the optimal use of AM in patients with higher severity of renal parenchymal damage and scar formation risk, and assessment of glomerular architecture after surgery to further support the protective role of AM in maintaining renal integrity. Even so, these preliminary findings suggest adjunctive application of AM in partial nephrectomy presents a promising technique.

Funding

A grant was provided by BioTissue for costs related to the IRB review process.

Ethics approval

The Sterling Institutional Review Board (Atlanta, GA) and was determined to be exempt under 45 CFR §46.101(d).

Consent

No identifiable information was collected or used. The IRB approved request to waive consent.

Competing Interests

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- Deng, H., et al., Partial nephrectomy provides equivalent oncologic outcomes and better renal function preservation than radical nephrectomy for pathological T3a renal cell carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Int Braz J Urol, 2021. 47(1): p. 46-60. [CrossRef]

- El-Ghazaly, T.H., R.J. Mason, and R.A. Rendon, Oncological outcomes of partial nephrectomy for tumours larger than 4 cm: A systematic review. Can Urol Assoc J, 2014. 8(1-2): p. 61-6. [CrossRef]

- Leppert, J.T., et al., Incident CKD after Radical or Partial Nephrectomy. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2018. 29(1): p. 207-216. [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.C., et al., Decline in renal function after partial nephrectomy: etiology and prevention. J Urol, 2015. 193(6): p. 1889-98. [CrossRef]

- Tighe, S., et al., Basic science review of birth tissue uses in ophthalmology. Taiwan J Ophthalmol, 2020. 10(1): p. 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M., M. Esposito, and G. Lovallo, A single-center, retrospective review of robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy with and without cryopreserved umbilical cord allograft in improving continence recovery. J Robot Surg, 2020. 14(2): p. 283-289. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P.A., et al., Cryopreserved placental tissue allograft accelerates time to continence following robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Journal of Robotic Surgery, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Considine, J., et al., Amniotic bladder therapy: six-month follow up treating interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Can J Urol, 2024. 31(3): p. 11898-11903.

- Bioregenerative Umbilical Cord Amniotic Membrane Allograft Ureteral Wrap During Robot-Assisted Ureterolysis. Journal of Endourology Case Reports. 0(0): p. null. [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, M., Lovallo, G., Stifelman, M., & Ahmed, M. , ROBOT-ASSISTED LAPAROSCOPIC MANAGEMENT OF INFLATABLE PENILE PROSTHESIS RESERVOIR MIGRATION INTO BLADDER WITH UTILIZATION OF CRYOPRESERVED AMNIOTIC MEMBRANE AND UMBILICAL TISSUE. Journal of Urology, 2017. 197(4S): p. e1059. [CrossRef]

- Black, L.M., J.M. Lever, and A. Agarwal, Renal Inflammation and Fibrosis: A Double-edged Sword. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry, 2019. 67(9): p. 663-681. [CrossRef]

- Atik, Y.T., et al., The Simple Nephrectomy Is Not Always Simple: Predictors of Surgical Difficulties. Urologia Internationalis, 2022. 106(6): p. 553-559. [CrossRef]

- Li, B., et al., Inflammation drives renal scarring in experimental pyelonephritis. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology, 2017. 312(1): p. F43-F53. [CrossRef]

- Bhayani, S.B., da Vinci robotic partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: an atlas of the four-arm technique. J Robot Surg, 2008. 1(4): p. 279-85. [CrossRef]

- Bemenderfer, T.B., et al., Effects of Cryopreserved Amniotic Membrane-Umbilical Cord Allograft on Total Ankle Arthroplasty Wound Healing. J Foot Ankle Surg, 2019. 58(1): p. 97-102. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.C., HC-HA/PTX3 Purified From Amniotic Membrane as Novel Regenerative Matrix: Insight Into Relationship Between Inflammation and Regeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2016. 57(5): p. ORSFh1-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.T., et al., HC-HA/PTX3 Purified From Human Amniotic Membrane Reverts Human Corneal Fibroblasts and Myofibroblasts to Keratocytes by Activating BMP Signaling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2020. 61(5): p. 62. [CrossRef]

- Marleau, A.M., et al., Reduction of tumorigenicity by placental extracts. Anticancer Res, 2012. 32(4): p. 1153-61.

- Gottlieb, J., et al., Impact of Cryopreserved Placental Allografts on Biochemical Recurrence in Prostate Cancer. Cancers (Basel), 2024. 16(17). [CrossRef]

- Laganosky, D.D., C.P. Filson, and V.A. Master, Surgical Margins in Nephron-Sparing Surgery for Renal Cell Carcinoma. Curr Urol Rep, 2017. 18(1): p. 8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).