Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Archaeological tourism – definition, roles and impacts

2.2. Sustainable development and archaeotourism

2.3 The issue of archaeological site valuation and the methods for assessing tourism potential

3. Materials and Methods

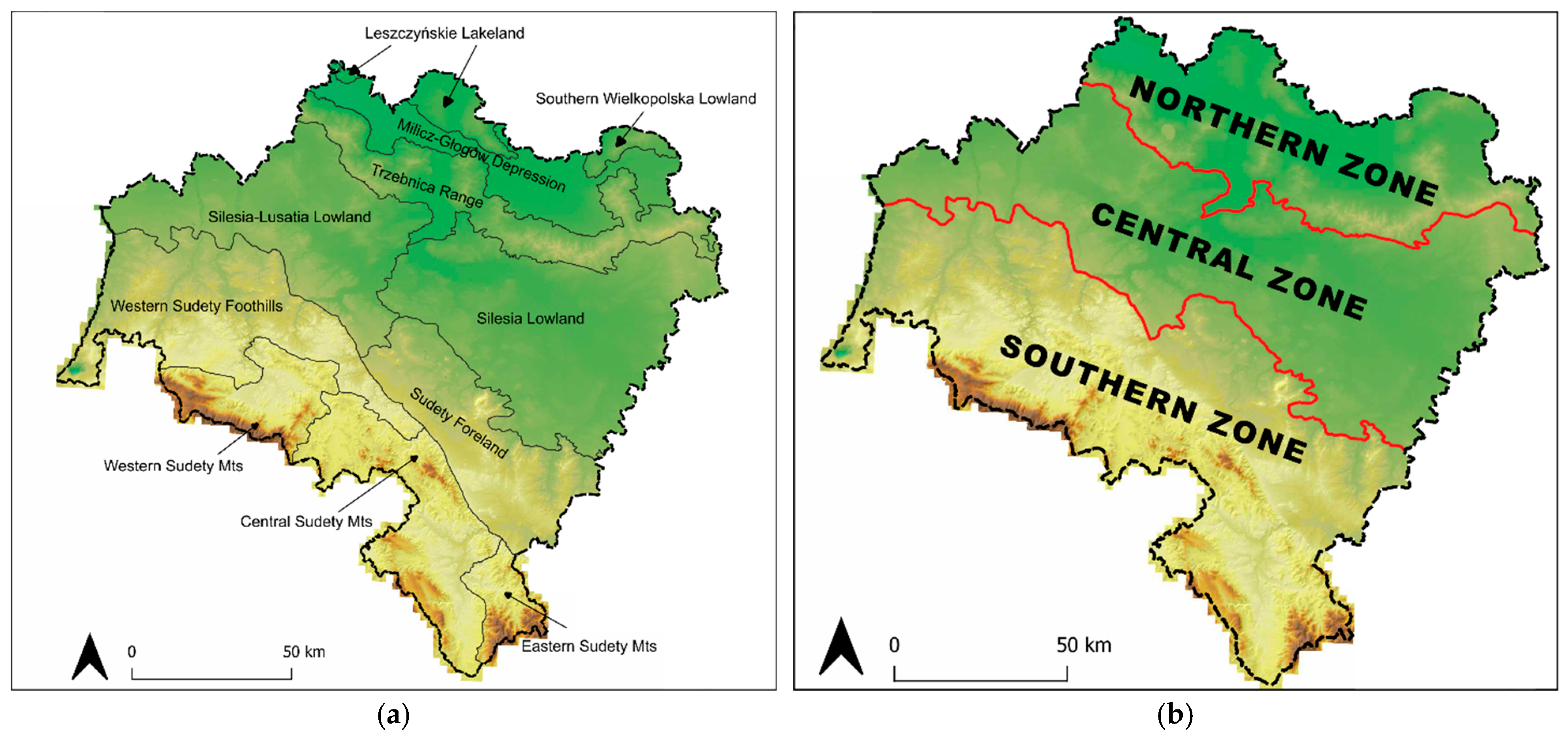

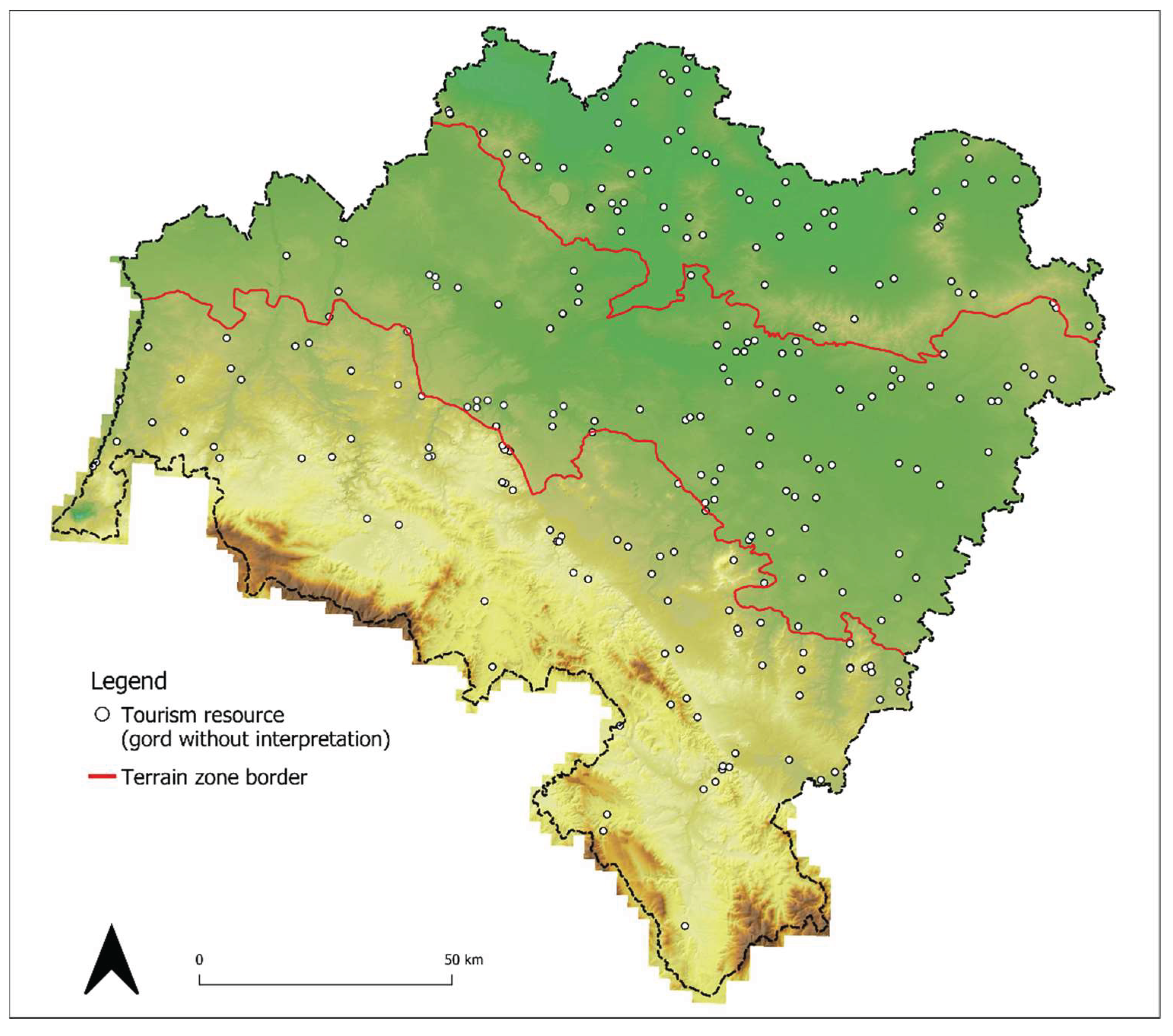

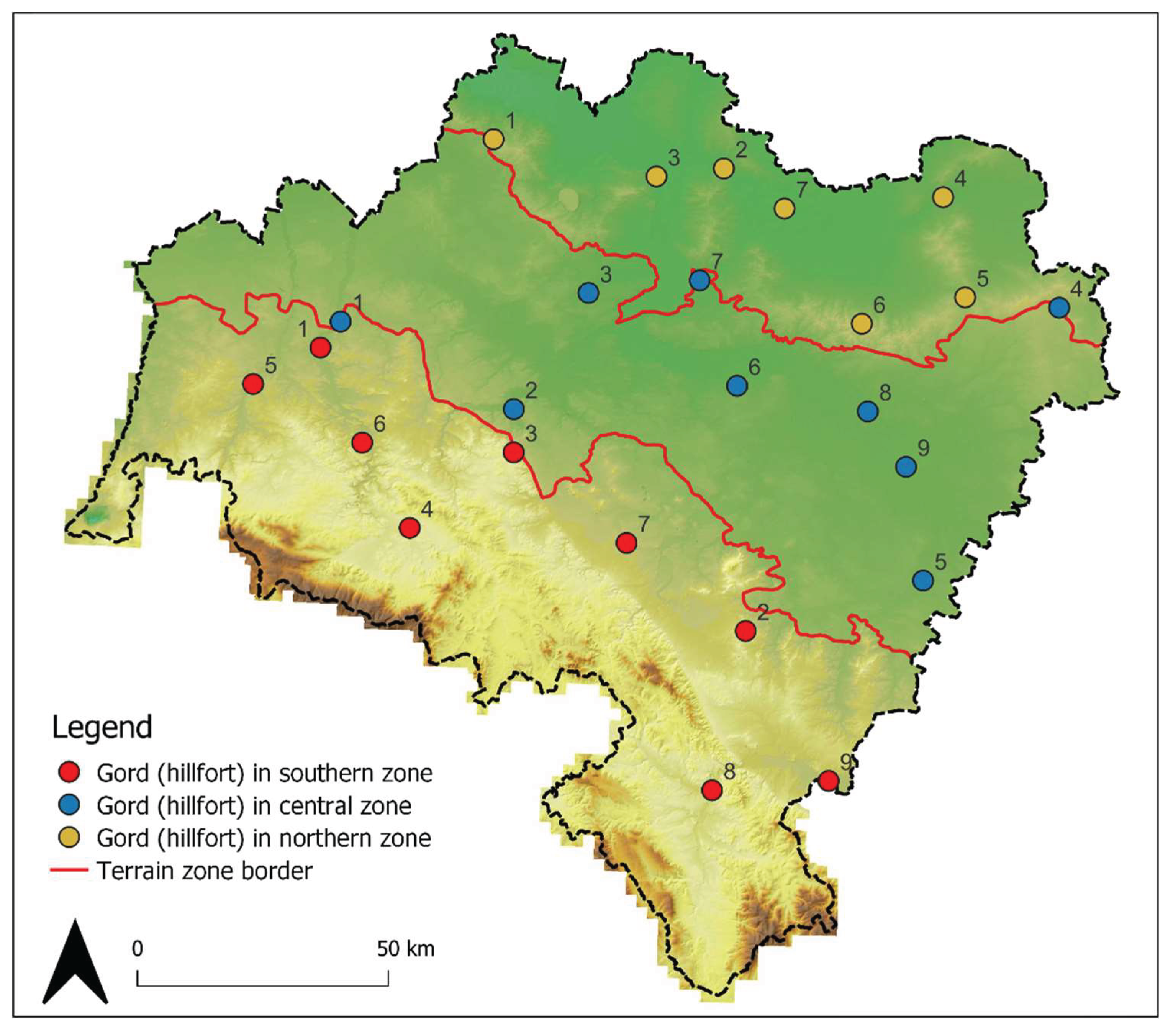

3.1. Study area

- Southern Zone (SZ): Comprising mountainous areas, foothills, and foreland regions (Sudetes, Western Sudetes Foothills, and Sudetes Foreland).

- Central Zone (CZ): Encompassing lowland areas in the regional core (Silesia-Lusatia Lowlands and Silesia Lowland).

- Northern Zone (NZ): Including the Trzebnica Range, Milicz-Głogów Depression, and fragments of other physical-geographical units.

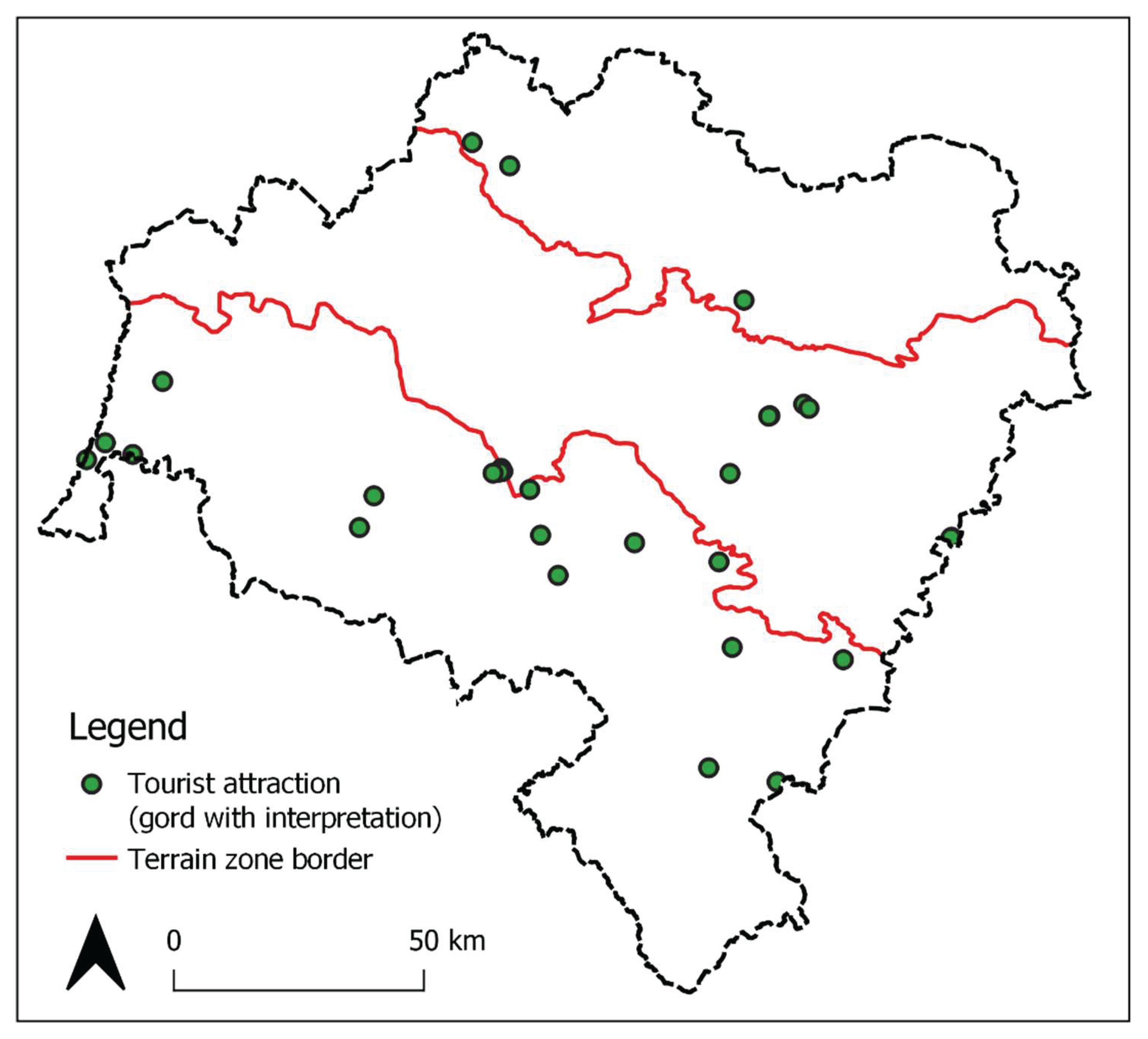

3.2. Subject of research

3.3 Aims and research questions

- How many of the numerous hillforts in Lower Silesia exhibit high tourism potential, enabling their transformation into viable attractions?

- If the southern part of Lower Silesia is the most touristically attractive region, do hillforts in this area also demonstrate the highest tourism potential?

- Which variables are most critical to include in a preliminary assessment of hillforts for tourism development?

- Physical and morphological attributes,

- Accessibility and proximity to infrastructure,

- Conservation status,

- Representation in tourism literature and digital media.

3.4. Resources and research methods

3.5. Assessment method of tourism potential of hillfort

- Physical characteristics,

- Surroundings and accessibility,

- Information visibility.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Inventory of hillfords in Lower Silesia

- Southern Zone: 88 hillforts (35% of the total),

- Central Zone: 93 hillforts (37%),

- Northern Zone: 70 hillforts (27%).

- 9 hillforts from the Southern Zone,

- 9 from the Central Zone,

- 7 from the Northern Zone.

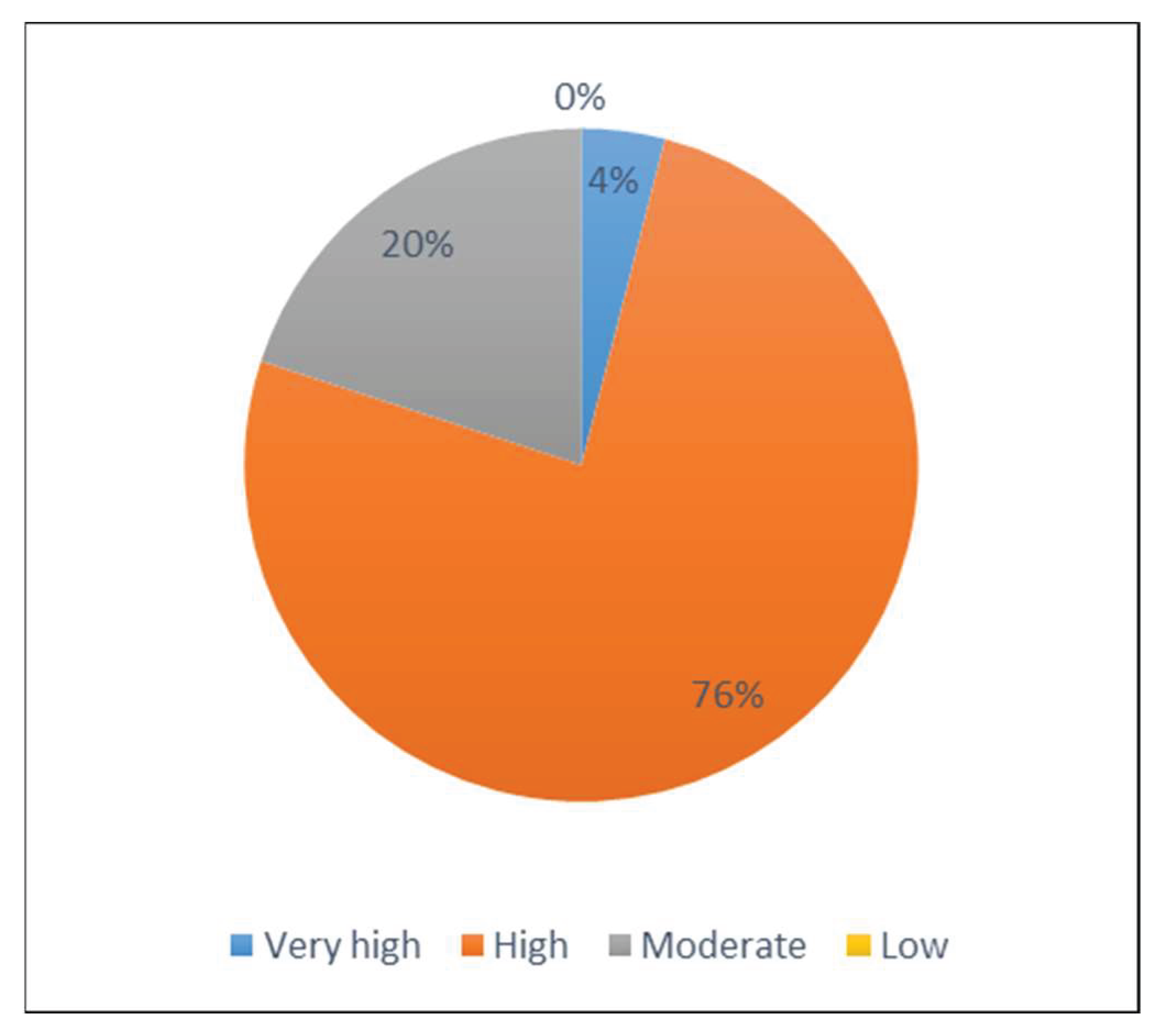

4.2. Tourism potential assessment of selected hillfords

- Category 1 (Site Characteristics): 70% of maximum points (ca. 29/40),

- Category 2 (Surroundings and Accessibility): 60% (ca. 15/25),

- Category 3 (Information Visibility): 56% (ca. 5,6/10) (Table 5).

4.3. Physical characteristics assessment

4.4. Assessment of surroundings, accessibility and information visibility

5. Conclusions

5.1. Final results and further research

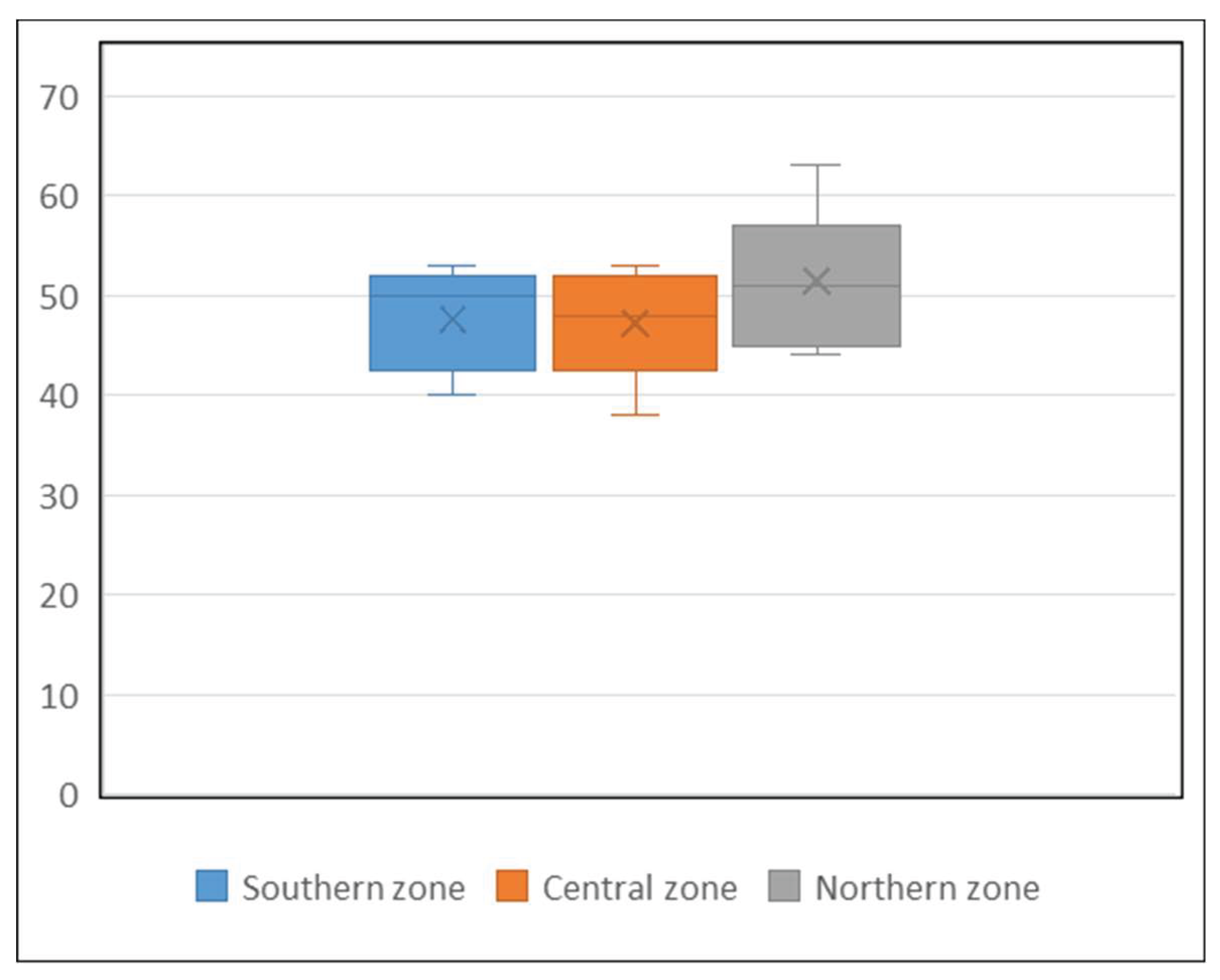

- Hypothesis 1 (Due to the distribution of hillforts across zones with distinct terrain morphologies, monuments exhibit significant variations in tourism potential scores) was rejected. The mean scores for tourism potential across all three zones demonstrated negligible variation, indicating comparable levels of assessed value.

- Hypothesis 2 (Hillforts in the southern zone achieve the highest tourism potential ratings, reflecting the region’s established reputation as Lower Silesia’s most touristically attractive area) was also rejected, as the northern zone yielded the highest mean scores.

5.2. Evaluation of method and recommendations

- Source accessibility limitations - challenges arose in accessing up-to-date archaeological literature and artifact typologies due to the fragmented availability of publications. Additionally, the level of detail in excavation publications varied significantly across sites.

- Tourism potential beyond physical attributes - despite low ratings in physical characteristics for certain sites, their tourism potential remained considerable due to locational advantages, surrounding infrastructure, or contextual features. For example, hillfort in Boguszyn, physically combined with a religious landmark (chapel), equipped with accessible parking, and offering panoramic views – demonstrated high potential despite modest physical scores.

- expand or separate evaluative categories – differentiate between research history and artifact typology assessments to reduce conceptual overlap.

- integrate historical sources – introduce a criterion assessing historical written records, which are critical for constructing site narratives.

- evaluate structural remains – add a category for assessing preserved structural features (e.g., stone/brick constructions) that enhance landscape appeal.

- re-calibrate scenic value metrics – diminish the weight assigned to viewpoint assessments

- incorporate risk analysis: integrate criteria for safety considerations for both tourists (e.g., terrain hazards) and sites (e.g., visitor-induced degradation).

- stakeholder engagement: assessing the willingness and capacity of local authorities and communities to participate in site stewardship.

- collaborative frameworks: evaluating partnerships with conservation and archaeological authorities to ensure alignment with preservation standards.

- interpretative feasibility: determining the viability of reconstructions and heritage interpretation strategies to enhance visitor engagement.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Category 1: Physical characteristics (40 points).

| Criterion | Indicators and scores |

| Site status* | 4 – Confirmed archaeological site recorded in the Register of Archaeological Monuments 3 – Confirmed archaeological site listed in the Archaeological Heritage Inventory or presumed site recorded in the Register of Archaeological Monuments 2 – Confirmed site not recorded in Register or Inventory or presumed site recorded in the Archaeological Heritage Inventory1 – Presumed site recognized by specialists (archaeologists or related fields) but unregistered0 – Presumed site identified by amateurs (e.g., enthusiasts) |

| * In Poland, archaeological heritage is cataloged through two distinct tiers of documentation:1) Register of Archaeological Monuments (Rejestr Zabytków Archeologicznych) – the highest legal tier, comprising sites of exceptional historical, scientific, or cultural significance. 2) Archaeological Heritage Inventory (Ewidencja Zabytków Archeologicznych) – a comprehensive administrative list maintained at the voivodship (województwo) level, encompassing all identified archaeological sites regardless of significance. | |

| Chronology and archaeological cultures | 3 – A site with a confirmed chronology spanning ≥2 settlement phases and/or usage dating to ≥2 centuries and/or associated with ≥2 archaeological cultures2 – A site with a confirmed chronology spanning 1 settlement phase and/or usage dating to 1 century and/or associated with 1 archaeological culture1 – A site with tentative chronology/archaeological culture0 – A site with undetermined chronology/archaeological culture |

| Research, documentation, literature | 6 – Open-area excavations yielding abundant artefacts (incl. rare/unique), providing extensive knowledge about the site presented in documentation and/or publications5 – Open-area excavations yielding common artefacts, providing extensive knowledge about the site presented in documentation and/or publications4 – Test excavations (trial pits) with rare and common artefacts, providing significant verified knowledge about the site presented in documentation and/or publications3 – Test excavations (trial pits) with common artifacts providing significant verified knowledge about the site or surface surveys with rare finds, presented in documentation and/or publications2 – Surface surveys with common artefacts, providing basic knowledge about the site, presented in documentation and/or publications1 – Surface surveys without artefacts, with basic description in documentation and/or publications0 – No research, documentation, or literature |

| State of preservation | 4 - A well-preserved site without damage3 – A well-preserved site with minor damage (e.g., partial damage to earth walls or motte/mound)2 – The surface of the site is ≥50% preserved, retaining structural components, allowing typological identification1 – The surface of the site is ≥50% preserved, without structural components or the site is preserved <50% of the surface, but with structural elements (e.g. part of the earth wall)0 – A site destroyed by more than 50%, without characteristic elements or with elements of objects that are difficult to recognise and identify |

| Site complexity | 3 – Multi-component site with clear boundaries (e.g., fortified settlement with bailey/suburb and ditch/moat)2 – Two-component site with clear boundaries (e.g., gord in form of hill with ditch or earth walls)1 – Single-component site with clear boundaries (e.g., simple motte without ditch)0 – A site without clear boundaries, difficult to recognise in the landscape |

| Site size | 4 – Very large (>1 ha)3 – Large (>0.5 – 1 ha)2 – Medium (>0.1 – 0.5 ha)1 – Small (0.01–0.1 ha)0 – Very small (<0.01 ha) |

| Site visibility | The number of directions (sides) from the outside, from which the site can be observed:3 – Fully visible from all sides, ≥1 unobstructed view2 – Visible from ≥2 sides with minor obstructions1 – Visible from 1 side with minor obstructions0 – Visibility obstructed from all sides |

| Land cover | 3 – Open meadow/lawn or exposed terrain 2 – Mixed cover (meadow/forest) with sparse undergrowth or treeless area with dense vegetation (e.g. grass) partially obscuring the visibility of the structural elements of the site1 – Park/forest with sparse undergrowth0 – Park/forest with dense undergrowth (shrubs/tall grass) severely limiting visibility of the site |

| Site prominence** in the case of multi-component sites, the highest element/object is taken into account | Prominence above surrounding terrain6 – >4 m 5 – >3–4 m4 – >2–3 m3 – >1.5–2 m2 – >1–1.5 m 1– 0.5–1 m0 – <0.5 m |

| Viewpoint | 4 – On-site with a vast, multi-plan panorama3 – On-site with an average (e.g. single-plan) panorama2 – Within 100 m, with a vast, multi-plan panorama1 – Within 100 m, with an average (e.g. single-plan) panorama0 – At a distance of more than 100 m |

- Category 2: Surroundings and accessibility (25 points).

| Criterion | Indicators and scores |

| Land accessibility | 4 – Open area, fenceless, publicly accessible (e.g., state-owned forests, urban parks)3 – Open area, but with unclear ownership or private land, fenceless, with access permitted2 – Closed area (e.g. private land), no possibility of entering the site, but with the possibility of approaching the object directly and observing it easily1 – Closed area (e.g. private), no possibility of entering the site, possibility of easy observation of the site from a distance of up to 50 m0 - Closed area (e.g. private), no possibility of entering the site, possibility of limited observation from a distance of up to 50 m or observation from a distance of over 50 m |

| Proximity to tourist trails | 5 – At least 2 different trail types or at least 3 trails of one type crossing the site4 – 2 trails of one type crossing the site3 – 1 trail crossing the site 2 – ≤200 m from nearest trail1 – 200–500 m from nearest trail0 – >500 m from trails |

| Type of access (road, path) | 4 – Adjacent to the asphalt road3 – Adjacent to the unsealed road or within 100 m of an asphalt road with a clearly visible path2 – ≤100 m from the unsealed road with a clearly visible path to the site or >100 to 500 m from the asphalt road with a clearly visible path to the site1 – 100–500 m from the unsealed road with a clearly visible path to the site0 – >500 m from any road |

| Distance to public transport | Proximity to a train station or bus stop:2 – within 1 km 1 – >1 to 5 km0 – >5 km |

| Nearby archaeological sites | 3 – Within 5 km from at least 1 developed site (tourist attraction) or at least 1 site of another type2 – At least 2 tourism resources (undeveloped sites) within a distance of 5 km1 – At least 1 tourism resource (undeveloped site) within a distance of 5 km0 – No sites within 5 km |

| Proximity to tourist attractions | 5 – ≤1 km from supra-regionally significant attraction4 – ≤1 km from regionally significant attraction3 – ≤1 km from locally significant attraction2 – >1 to 5 km from supra-regional attraction1 – >1 to 5 km from regional/local attraction0 – >5 km from any attraction |

| Parking availability | 2 – ≤200 m from site1 – >200 m–1 km0 – >1 km |

- Category 3: Information visibility (10 points).

| Criterion | Indicators and scores |

| Type of information source(points added up, max 8 points) | +3 – A site presented in travel guides/travel portals+2 – A site presented in specialized historical/geographic sources (regional studies) or regional websites+2 – A site presented in open-access archaeological databases (e.g. zabytek.pl) or in archaeological publications +1 – Marked on tourist maps0 – No information or erroneous data, e.g. the site is marked on the map wrongly |

| Geocaching presence | 2 – Cache on-site1 – Cache ≤200 m from site0 – cache >200 m away |

References

- Bahn, P.G. Archaeology. The Essential Guide to Our Human Past, 1st ed.; Publisher: Smithsonian Books, Washington, DC, the US, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, C.; Carr, N. Tourism and archaeology: an introduction. In Tourism and archaeology. Sustainable meeting grounds; Walker, C., Carr, N., Eds.; Left Coast Press: New York, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kairišs, A.; Oļevska, I. Development Aspects of Archaeological Sites in Latvia. Arch. Lituana, 2021, 22, 10–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D. J.; Tahan, L. G. . In Archaeology and Tourism: Touring the Past. In Archaeology and Tourism: Touring the Past; Timothy, D. J., Tahan, L. G., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Burtenshaw, P. Tourism and the Economic Value of Archaeology. In Archaeology. In Archaeology and Tourism: Touring the Past; Timothy, D. J., Tahan, L. G., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McGettingan, F.; Rozenkiewicz, A. Archaeotourism—The Past is Our Future. In Cultural Tourism; Raj, R., Griffin, K., Morpeth, N., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, 2013; pp. 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Banasiak, P.; Wielocha, E. Sprawozdanie z ogólnopolskiej interdyscyplinarnej konferencji naukowej Forum Archeologii Publicznej. Popularyzacja i edukacja archeologiczna. In Forum Archeologii Publicznej. Popularyzacja i edukacja archeologiczna; Banasiak, P., Freygant-Dzieruk, M., Stawarz, N., Wielocha, E., Eds., Łódź-Toruń, 2020, 11–24.

- Occupancy of tourist accommodation establishments in 2024, Statistics Poland. 2024, 11. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/culture-tourism-sport/tourism/occupancy-of-tourist-accommodation-establishments-in-2024,11,3.html (accessed on 30.04.2025).

- Turystyka w województwie dolnośląskim w 2023, r. Statistical Office in Wrocław. Available online: https://wroclaw.stat.gov.pl/opracowania-biezace/opracowania-sygnalne/kultura-sport-turystyka/turystyka-w-wojewodztwie-dolnoslaskim-w-2023-r-,1,12.html (accessed on 30.04.2025).

- UNWTO. Global Report on the power of youth travel. Available online: https://www.wysetc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Global-Report_Power-of-Youth-Travel_2016.pdf (accessed on 30.04.2025).

- Ketter, E. Millennial travel: tourism micro-trends of European Generation Y. JTF; 2020, 7, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polish Tourism Organization. Available online: https://ttgpolska.pl/rafal-szmytke-ocena-polskiego-sezonu-turystycznego-2024/ (accessed on 30.04.2025).

- Rogowski, M. Diagnoza i optymalizacja turystyfikacji (zjawiska overtourism’u) w parku narodowym. Available online: https://kpn.gov.pl/pliki-do-pobrania/otworz/a5a99070-0634-4b25-aea6-302b32fb3d4f.pdf (accessed on 30.04.2025).

- Rogowski, M. A method for overtourism optimisation for protected areas. JORT, 2025, 49, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analiza ruchu turystycznego we Wrocławiu w roku 2024. Available online: https://www.wroclaw.pl/beta2/files/dokumenty/769556/Prezentacja%20-%20Ruch%20Turystyczny%20we%20Wroc%C5%82awiu%202024.pdf (accessed on 30.04.2025).

- Timothy, D.J. Cultural heritage and tourism. An introduction; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baram, U. Tourism and archaeology. In Encyclopedia of Archaeology, 1st ed.; Pearshall, D.M., Ed.; Academic Press: USA, 2007, 2131–2134. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Busaidi, Y. Public interpretation of archaeological heritage and archaeotourism in the Sultanate of Oman. PhD thesis, Cardiff School of Management, Cardiff, 2008.

- Thomas, B.; Langlitz, M. Archaeotourism, archaeological site preservation, and local communities. In Feasible management of archaeological heritage sites open to tourism, 1st. ed.; Comer, D.C., Willems, A., Eds.; Springer Cham: Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo, R. F.; Porter, B. W. Archaeotourism and the Crux of Development. AN; 2010, 51, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Erdoğan, H.A.; Samuels, J. Archaeological Heritage and Tourism: The Archaeotourism Intersection, Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites. 2024, 26, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanier, K.; Senica, T. Archaeological Tourism Products: Towards a Concept Definition. AT-TIJ 2023, 16, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter,T. L. Heritage Tourism and Archaeology: Critical Issues. The SAA Archaeological Record, 2005, 5, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Boniface, P. Managing quality cultural tourism, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pacifico, D.; Vogel, M. Archaeological sites, modern communities, and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res., 2012, 39, 3–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Cros, H.; McKercher, B. Cultural tourism, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London-New York, UK, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fyall, A.; Leask, A.; Barber, S.B. Marketing archaeological heritage for tourism. In Archaeology and Tourism: Touring the Past; Timothy, D. J., Tahan, L. G., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fushiya, T. Archaeological Site Management and Local Involvement: A Case Study from Abu Rawash, Egypt. CMAS 2013, 12, 324–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Guide to Best Practices for Archaeological Tourism. Available online: https://www.archaeological.org/pdfs/AIATourismGuidelines.pdf (accessed on 3.05.2025).

- Dhanjal, S. Archaeological sites and informal education: Appreciating the archaeological process. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites. 2008, 10, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S. Community archaeology. In Key Concepts in Public Archaeology, 1st ed.; Moshenska, G., Ed.; UCL Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bartecki, B. The Goths’ Return to the Hrubieszów Basin. The Social Use of Archaeological Heritage for Building a Local Identity. Analecta Archaeologica Ressoviensia 2018, 13, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauf, D.S. The European Route of Megalithic Culture: Pathways to Europe’s Earliest Stone Architecture. In Feasible management of archaeological heritage sites open to tourism, 1st. ed.; Comer, D.C., Willems, A., Eds.; Springer Cham: Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schierhold, K. Westphalian Megaliths Go Touristic: Archaeological Research as a Base for the Development of Tourism, In Feasible management of archaeological heritage sites open to tourism, 1st. ed.; Comer, D.C., Willems, A., Eds.; Springer Cham: Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Nyaupane, G.P. Cultural heritage and tourism in developing world. A regional perspective, 1st ed.; Routledge: London-New York, UK-USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, T. Archaeological Heritage Education: Citizenship from the Ground Up. Treballs d’Arqueologia 2009, 15, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chowaniec, R. Archaeology for everyone. Presenting archaeological heritage to the public in Poland; Ministry of Science and Higher Education: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pawleta, M. Przeszłość we współczesności. Studium metodologiczne archeologicznie kreowanej przeszłości w przestrzeni społecznej; Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM: Poznań, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Afkhami, B. Archaeological tourism; characteristics and functions. JHAAS, 2021, 6, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, D. Archaeology and education In Key Concepts in Public Archaeology, 1st ed.; Moshenska, G., Ed.; UCL Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chowaniec, R. Dziedzictwo archeologiczne w Polsce. Formy edukacji i popularyzacji; Archaeology Institute of Warsaw University: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosio Arias, A.G.; Moreno Escobar, J.J.; Tejeida Padilla, R.; Morales Matamoros, O. Historical-Cultural Sustainability Model for Archaeological Sites in Mexico Using Virtual Technologies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7337–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, N.; Demas, M. Immovable Heritage: Appropriate Approaches to Archaeological Sites and Landscapes. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, 2nd ed.; Smith, C., Ed.; Springer: New York, USA, 2020, 5554–5568. [Google Scholar]

- Zan, L.; Lusiani. M. Managing Change and Master Plans: Machu Picchu Between Conservation and Exploitation. Archaeologies 2011, 7, 329–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. The Effects of Tourism on the Cusco Region of Peru. Journal of Undergraduate Research 2008, 11, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, M.H.; Tayeh, S.A. The Impacts of Tourism Development on the Archaeological Site of Petra and Local Communities in Surrounding Villages. Asian Soc. Sci. 2011, 7, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comer, D.C. Tourism and Archaeological Heritage Management at Petra. Driver to Development or Destruction? Springer: New York, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miura, K. A note on the current impact of tourism on Angkor and its environs. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2007, 8, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germanà, M. L.; Kotarba-Morley, A. M. Ethics, Use, and Inclusion in Managing Archaeological Built Heritage: The Relationship Between Experts and Visitors/Users. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, 2nd ed.; Smith, C., Ed.; Springer: New York, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mairna, H. M. Cultural Heritage: A Tourism Product of Egypt Under Risk. JEMT 2021, 1, 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Comer, D.C.; Willems, W.; Tourism and archaeological heritage. Driver to development or destruction? ICOMOS, Paris, 2011. Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/1208/1/III-1-Article2_Comer_Willems.pdf (accessed on 3.05.2025).

- Almasri, R.; Ababneh, A. Heritage Management: Analytical Study of Tourism Impacts on the Archaeological Site of Umm Qais — Jordan. Heritage 2021, 4, 2449–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeben, J.; Groenwoudt, B.J.; Hallewas, D.P.; Willems, W.J.H. Proposals for a practical system of significance evaluation in archaeological heritage management, Eur. J. Archaeol. 1999, 2, 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Wurz, S.; Van der Merve, J.H. 2005, Gauging site sensitivity for sustainable archeotourism in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. SAAB 2005, 60, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, M.E.; Ecotourism. Principles, Practices and Policies for Sustainability. UNEP, 2002. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/ecotourism-principles-practices-and-policies-sustainability (accessed on 2.05.2025).

- McKercher, B.; Du Cros, H. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barrowclough, D. Visiting Malta’s Past: sustaining archaeology and tourism. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/7691014/Visiting_Maltas_Past_Sustaining_Archaeology_and_Tourism (accessed on 2.05.2025).

- Slehat, M.M. Evaluation of potential tourism resources for developing different forms of tourism: Case Study of Iraq Al-Amir and its surrounding areas — Jordan. PhD thesis, Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, 2018. Available online: https://edoc.ku.de/id/eprint/22441/ (accessed on 3.05.2025).

- Palumbo, G.; Al-Tikriti, W.Y.; Mahdy, H.; Al Nuaimi, A.; Al Kaabi, A.; Altawallbeh, D.E.; Muhammad, S.A.; Marcus, B. Protecting the Invisible: Site-Management Planning at Small Archaeological Sites in al-Ain, Abu Dhabi. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2014, 16, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avner, U. The potential of ancient sites in the Eliat Region for cultural tourism. In Tourism Destination Development and Branding, Conference Proceedings, Eilat, Israel, 14–17 October 2009, 107–126.

- Martínez-Hernández, C.; Mínguez, C.; Yubero, C. Archaeological Sites as Peripheral Destinations. Exploring Big Data on Fieldtrips for an Upcoming Response to the Tourism Crisis after the Pandemic. Heritage 2021, 4, 3098–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunis, E. Archaeology and Tourism: A Viable Partnership? Introduction. In Of the Past, for the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation; Agnew, N., Bridgland, J., Eds., Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, USA, 2006; Available online: https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/of_past_for_future.html (accessed on 12.04.2025).

- Ramsey, D.; Everitt, J. If you dig it, they will come! Archaeology heritage sites and tourism development in Belize, Central America. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoney, S. M. Presenting archaeological sites to the public in Scotland. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 2009. Available online: https://theses.gla.ac.uk/801/ (accessed on 15.04.2025).

- Blasco López, M. F.; Recuero Virto, N.; Aldas Manzano, J.; Garcia-Madariaga, J. Tourism sustainability in archaeological sites. JCHMSD 2018, 8, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco López, M. F.; Recuero Virto, N.; Aldas Manzano, J.; Garcia-Madariaga, J. Archaeological tourism: looking for visitor loyalty drivers. JHT 2020, 15, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Fernández, A.; Hernández-Rojas, R.; Jimber del Rio, J.A.; Casas-Rosal, J.C. Tourist Motivations and Satisfaction in the Archaeological Ensemble of Madinat Al-Zahra. Sustain. 2019, 11, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, H.A.; Birsen, A.G.; Bilim, Y. Archaeotourist: A Novel Tourist Type in Heritage Tourism, Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites., 2024, 26, 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The management of archaeological resources: the Airlie House report. McGimsey, C.R., Davis, H.A., Society of American Archaeology: Washington, USA, 1977. Available online: https://documents.saa.org/container/docs/default-source/doc-publications/archive/airlie_house.pdf (accessed on 15.04.2025).

- Carman, J. The importance of things: archaeology and the law. In Managing archaeology, 1st ed.; Cooper, M.A., Firth, A., Carman, J., Wheatley, D., Eds.; Routledge: London-New York, USA-UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kobyliński, Z.; Wysocki, J. Problemy wartościowania dziedzictwa archeologicznego. In Wartościowanie w ochronie i konserwacji zabytków; Szmygin, B., Ed., PKN ICOMOS & Politechnika Lubelska: Warszawa-Lublin, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kobyliński, Z. Kryteria i metody wartościowania dziedzictwa archeologicznego: aktualny stan dyskusji. In System wartościowania dziedzictwa. Stan badań i problemy; Szmygin, B., Ed., Politechnika Lubelska & PKN ICOMOS: Lublin-Warszawa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Glassow, M. Issues in evaluating the significance of archaeological resources. Am. Antiq. 1977, 42, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, M. On archaeological value. In Archaeological sites: Conservation and management; Sullivan, S., Mackay, M., Eds.; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/books/arch_sites_conserv_mgmnt.html (accessed on 21.03.2025).

- Du Cros, H. A new model to assist in planning for sustainable cultural heritage tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2002, 3, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; du Cros, H. Testing a Cultural Tourism Typology. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2003, 5, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, B. Archaeological tourism opportunity spectrum: experience based management and design as applied to archaeological tourism. MA thesis, Utah State University, 2015. Available online: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?params=/context/gradreports/article/1539/&path_info=auto_convert.pdf (accessed on 2.04.2025).

- Pralong, J.P. A method for assessing tourist potential and use of geomorphological sites. Geomorphologie 2005, 11, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E. Scientific Research and Tourist Promotion of Geomorphological Heritage. GFDQ 2008, 31, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, P.; Pereira, D. Methodological guidelines for geomorphosite assessment. Geomorphologie 2010, 2, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytrowski, P.; Kicińska, A. Waloryzacja geoturystyczna obiektów przyrody nieożywionej i jej znaczenie w perspektywie rozwoju geoparków. Problemy Ekologii Krajobrazu 2011, 29, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Doktor, M.; Miśkiewicz, K.; Welc, E.; Mayer, W. Criteria of geotourism valorization specified for various recipients. Geotourism 2015, 3–4, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilha, J. Inventory and quantitative assessment of geosites and geodiversity sites: a review. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubalikova, L. Geomorphosite assesment for geotourism purposes. Czech J. Tour. 2013, 2, 80–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobak, A. Review of the assessment methods of abiotic nature sites used in geotourism. Prace Komisji Geografii Przemysłu Polskiego Towarzystwa Geograficznego 2021, 35, 116–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ihnatowicz, A.; Koźma, J.; Wajsprych, B. Wałbrzyski Obszar Geoturystyczny — inwentaryzacja geotopów dla potrzeb promocji geoturystyki. Przegląd Geologiczny 2011, 59, 722–731. [Google Scholar]

- Koźma, J.; Cwojdziński, S.; Ihnatowicz, A.; Pacuła, J.; Zagożdżon, P.P.; Zagożdżon, K.D. Możliwości rozwoju geoturystyki w regionie dolnośląskim na przykładzie wybranych projektów dotyczących inwentaryzacji i waloryzacji geostanowisk. In Mezozoik i Kenozoik Dolnego Śląska; Żelażniewicz, A., Wojewoda, J., Cieżkowski, W., Eds, Eds.; WIND: Wrocław, Polska, 2011, 137–158.; Available online: http://www.ptgeol.pl/wp-content/uploads/PTG_81_Zjazd_2011.pdf (accessed on 2.05.2025).

- Różycka, M. Atrakcyjność geoturystyczna okolic Wojcieszowa w Górach Kaczawskich. Przegląd Geologiczny 2014, 62, 514–521. [Google Scholar]

- Różycka, M.; Migoń, P. Visitors’ background as a factor in geosite evaluation. The case of Cenozoic volcanic sites in the Pogórze Kaczawskie region, SW Poland. Geotourism 2014, 3–4, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różycka, M. , Migoń P.,, Customer-oriented evaluation of geoheritage — on the example of volcanic geosites in the West Sudetes, SW Poland. Geoheritage 2018, 10, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowska, E.; Jaworski, K. 8th-10th century hillforts in the Sudetes – exploring current state of research and observations, towards new horizons. Acta Archaeol. Carpath. 2021, 56, 335–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrzan, K. Kraina grodów. Krajobraz społeczności zamieszkujących obszar między środkową Obrą a środkową Prosną w VIII–X/XI w. PhD thesis, IAE PAN, Wrocław, Poland, 2022.

- Rodak, S. Podstawy datowania grodów z końca X–początku XIII w. na Dolnym Śląsku. In pago Silensi – Wrocławskie Studia Wczesnośredniowieczne: Wrocław, Poland, 4, 2017.

- Herold, H. Strongholds and early medieval states. In The Routledge Handbook of East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1300, 1st ed.; Curta, F., Ed; Routledge, UK, 2021.

- Lepage, J.D. Dictionary of Fortifications: An Illustrated Glossary of Castles, Forts, & Other Defensive Works from Antiquity to the Present Day; Pen & Sword Military: Barnsley, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

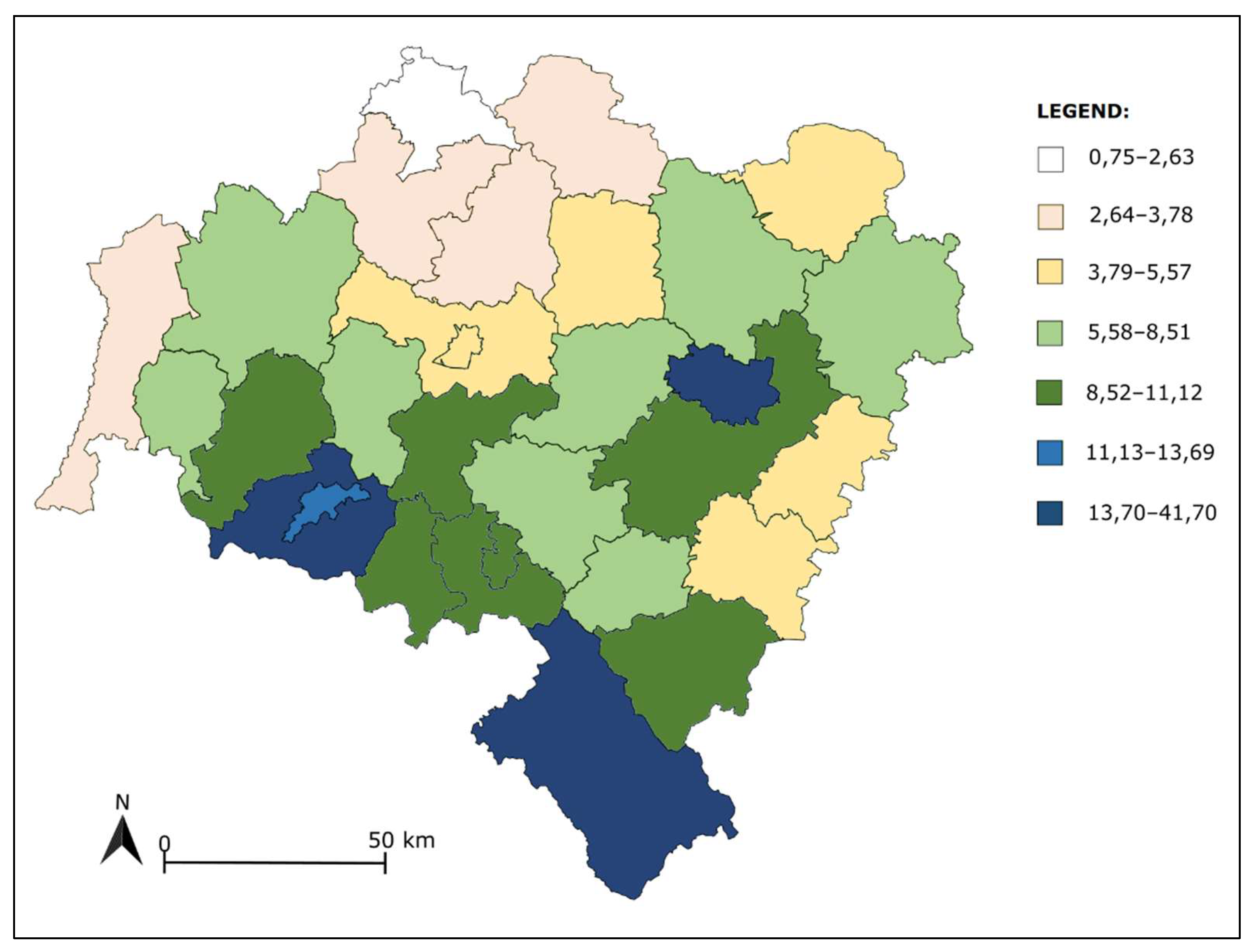

- Analiza walorów turystycznych powiatów i ich bezpośredniego otoczenia, Statistics Poland. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/statystyki-eksperymentalne/uslugi-publiczne/analiza-walorow-turystycznych-powiatow-i-ich-bezposredniego-otoczenia,1,1.html (accessed on 30.04.2025).

- Kaletynowie, M.; Lodowski, J. Grodziska wczesnośredniowieczne województwa wrocławskiego. Ossolineum: Wrocław, Poland, 1968.

- Jaworski, K. Grody w Sudetach (VIII-X w.). Uniwersytet Wrocławski: Wrocław, Poland, 2005.

- Nowakowski, D. Śląskie obiekty typu motte. Studium archeologiczno-historyczne. IAE PAN: Wrocław, Poland, 2017.

- Werczyński, D. Stanowiska archeologiczne na Dolnym Śląsku jako rzeczywiste walory turystyczne. PhD thesis, Institute of Geography and Regional Development: Wrocław; Poland, 2023.

- Leiper, N. Tourist attraction systems. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widawski, K.; Krzemińska, A.; Zaręba, A.; Dzikowska, A. A Sustainable Approach to Tourism Development in Rural Areas: The Example of Poland. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMasri, R.; Ababneh, A. Heritage Management: Analytical Study of Tourism Impacts on the Archaeological Site of Umm Qais—Jordan. Heritage 2021, 4, 2449–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijewski, T.; Mikułowski, B.; Wyrzykowski, J. Geografia turystyki Polski., 5th ed.; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski, M. Ocena walorów widokowych szlaków turystycznych na wybranych przykładach z Dolnego Śląska. Problemy Ekologii Krajobrazu 2009, 35, 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Landorf, C. Cultural Value and Sustainable Development: A Framework for Assessing the Tourism Potential of Heritage Places. In Feasible management of archaeological heritage sites open to tourism, 1st. ed.; Comer, D.C., Willems, A., Eds.; Springer Cham: Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczorowski, J. Wykluczeni. O likwidacji transport zbiorowego na wsi i w małych miastach. Przegląd Planisty 2019, 4, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, J.P. Life on the „B List:” Archaeology and tourism at sites that aren’t postcard worthy, In Tourism and archaeology. Sustainable meeting grounds; Walker, C., Carr, N., Eds.; Left Coast Press: New York, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ihamäki, P. Geocachers: the creative tourism experience. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology 2012, 3, 152–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierhold, K. Westphalian Megaliths Go Touristic: Archaeological Research as a Base for the Development of Tourism. In Feasible management of archaeological heritage sites open to tourism, 1st. ed.; Comer, D.C., Willems, A., Eds.; Springer Cham: Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Criterion | Max score |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Physical characteristics | Site status | 4 |

| Chronology & archaeological cultures | 3 | |

| Research, documentation, literature | 6 | |

| State of preservation | 4 | |

| Site complexity | 3 | |

| Site size | 4 | |

| Site visibility | 3 | |

| Land cover | 3 | |

| Site prominence | 6 | |

| Viewpoint | 4 | |

| TOTAL | 40 | |

| 2. Surroundings and accessibility |

Land accessibility | 4 |

| Proximity to tourist trails | 5 | |

| Type of access (road, path) | 4 | |

| Distance to public transport | 2 | |

| Nearby archaeological sites | 3 | |

| Proximity to tourist attractions | 5 | |

| Parking availability | 2 | |

| TOTAL | 25 | |

| 3. Information visibility | Type of information source | 8 |

| Geocaching presence | 2 | |

| TOTAL | 10 |

| Tourism potential | % of total points | Score range |

|---|---|---|

| Very high | ≥80% | ≥60 |

|

High |

60–79% | 45–59 |

| Moderate | 40–59% | 30–44 |

| Low | <40% | <30 |

| Southern zone | ||

| No. | Hillfort name | Poviat |

| 1 | Otok, st. 2 | bolesławiecki |

| 2 | Roztocznik, st. 1 | dzierżoniowski |

| 3 | Pomocne, st. 1 (Górzec) | jaworski |

| 4 | Jelenia Góra - Grabary, st. 1 | m. Jelenia Góra |

| 5 | Nawojów Śląski, st. 1 (Łagów) | lubański |

| 6 | Marczów, st. 1 | lwówecki |

| 7 | Nowy Jaworów, st. 1 | świdnicki |

| 8 | Boguszyn, st. 1 | kłodzki |

| 9 | Chałupki, st. 1 | ząbkowicki |

| Central zone | ||

| No. | Hillfort name | Poviat |

| 1 | Bolesławiec, st. 1 | bolesławiecki |

| 2 | Krajów, st. 2 | legnicki |

| 3 | Niemstów, st. 6 (Zwierzyniec) | lubiński |

| 4 | Dziesławice, st. 1 | oleśnicki |

| 5 | Niemil, st. 1 | oławski |

| 6 | Kadłub, st. 4 | średzki |

| 7 | Wrzosy, st. 1 (Kretowice) | wołowski |

| 8 | Wrocław-Sołtysowice, st. 2 | m. Wrocław |

| 9 | Gajków, st. 10 | wrocławski |

| Northern zone | ||

| No. | Hillfort name | Poviat |

| 1 | Dankowice, st. 1 | głogowski |

| 2 | Bełcz Mały, st. 1 | górowski |

| 3 | Chobienia, st. 3 | lubiński |

| 4 | Milicz, st. 1 | milicki |

| 5 | Bukowinka, st. 1 | oleśnicki |

| 6 | Trzebnica, st. 3 | trzebnicki |

| 7 | Kędzie, st. 2 | trzebnicki |

| Southern zone | ||||||

| No. | Hillfort name | Cat. 1 | Cat. 2 | Cat. 3 | Total | Potential Level |

| 1 | Otok, st. 2 | 25 | 9 | 6 | 40 | Moderate |

| 2 | Roztocznik, st. 1 | 24 | 11 | 5 | 40 | Moderate |

| 3 | Pomocne, st. 1 (Górzec) | 24 | 19 | 7 | 50 | High |

| 4 | Jelenia Góra - Grabary, st. 1 | 25 | 14 | 7 | 46 | High |

| 5 | Nawojów Śląski, st. 1 (Łagów) | 28 | 15 | 8 | 51 | High |

| 6 | Marczów, st. 1 | 28 | 11 | 6 | 45 | High |

| 7 | Nowy Jaworów, st. 1 | 32 | 16 | 5 | 53 | High |

| 8 | Boguszyn, st. 1 | 28 | 19 | 6 | 53 | High |

| 9 | Chałupki, st. 1 | 24 | 19 | 8 | 51 | High |

| Central zone | ||||||

| No. | Hillfort name | Cat. 1 | Cat. 2 | Cat. 3 | Total | Potential Level |

| 1 | Bolesławiec, st. 1 | 28 | 15 | 5 | 48 | High |

| 2 | Krajów, st. 2 | 32 | 16 | 5 | 53 | High |

| 3 | Niemstów, st. 6 (Zwierzyniec) | 25 | 15 | 1 | 41 | Moderate |

| 4 | Dziesławice, st. 1 | 22 | 12 | 4 | 38 | Moderate |

| 5 | Niemil, st. 1 | 28 | 10 | 6 | 44 | Moderate |

| 6 | Kadłub, st. 4 | 30 | 17 | 6 | 53 | High |

| 7 | Wrzosy, st. 1 (Kretowice) | 31 | 12 | 7 | 50 | High |

| 8 | Wrocław-Sołtysowice, st. 2 | 28 | 15 | 8 | 51 | High |

| 9 | Gajków, st. 10 | 30 | 13 | 4 | 47 | High |

| Northern zone | ||||||

| No. | Hillfort name | Cat. 1 | Cat. 2 | Cat. 3 | Total | Potential Level |

| 1 | Dankowice, st. 1 | 28 | 14 | 3 | 45 | High |

| 2 | Bełcz Mały, st. 1 | 34 | 17 | 3 | 54 | High |

| 3 | Chobienia, st. 3 | 27 | 11 | 6 | 44 | High |

| 4 | Milicz, st. 1 | 32 | 18 | 7 | 57 | High |

| 5 | Bukowinka, st. 1 | 25 | 16 | 5 | 46 | High |

| 6 | Trzebnica, st. 3 | 30 | 25 | 8 | 63 | Very high |

| 7 | Kędzie, st. 2 | 28 | 18 | 5 | 51 | High |

| Southern Zone | AVG. | MDN. | SD |

| Category 1 | 26,44 | 26,5 | 2,59 |

| Category 2 | 14,78 | 14,5 | 3,61 |

| Category 3 | 6,44 | 6 | 1,07 |

| Total SZ | 47,25 | 48 | 4,85 |

| Central Zone | AVG. | MDN. | SD |

| Category 1 | 28,22 | 28 | 2,94 |

| Category 2 | 13,89 | 15 | 2,13 |

| Category 3 | 5,11 | 5 | 1,91 |

| Total CZ | 47,22 | 48 | 4,98 |

| Northern Zone | AVG. | MDN. | SD |

| Category 1 | 29,14 | 28 | 2,85 |

| Category 2 | 17 | 17 | 4 |

| Category 3 | 5,29 | 5 | 1,75 |

| Total NZ | 51,43 | 51 | 6,52 |

| TOTAL (N=25) | AVG. | MDN. | SD |

| Category 1 | 27,84 | 28 | 2,36 |

| Category 2 | 15,08 | 15 | 2,73 |

| Category 3 | 5,64 | 6 | 1,36 |

| TOTAL | 48,56 | 50 | 4,70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).