1. Introduction

Drought is one of the most impactful abiotic factors affecting yield in agricultural and horticultural systems [

1,

2,

3,

4]. For example, Kim et al. [

5] analysed historical drought impact and global production data and showed an average yield reduction for annual crops in a single drought period of 8% for wheat, 7% for maize, 3% for rice and 7% for soy. Yield losses tend to be greater in slower growing perennials, e.g., 26% loss was observed in apple in a single season [

6], and can be further exacerbated because water deficit can adversely affect flower initiation, shoot length and branching, leading to decreased yield in subsequent growing seasons [

7]. With climate change, the frequency, intensity, duration and geographic spread of drought periods are predicted to increase globally [

5]. Furthermore, agriculture and horticulture are the biggest consumers of freshwater [

3] and global demands for food (hence water) are increasing, placing even more pressure on a limited resource. Future crop yields and worldwide food security are at risk if we cannot address this issue.

Plants respond to drought by physical and chemical changes mediated by their transcriptome. Gene responses to drought have been intensely studied [

3,

4,

8,

9], with numerous reviews showing that key components include genes of the abscisic acid (ABA) pathway [

10,

11,

12]. ABA is the primary phytohormone involved in responses to abiotic stresses such as water extremes (drought, flooding), temperature stress (both hot and cold), and excessive salinity [

10,

11,

13,

14]. ABA is a key mitigator of the plant drought response because it quickly stimulates short-term physiological changes, such as stomatal closure, thus regulating water loss through transpiration. In addition, ABA also regulates longer term responses, such as dormancy and growth inhibition via regulation of signaling peptides and various drought-responsive genes, e.g., genes encoding for membrane and protein stabilization, antioxidant activity, and biosynthesis of osmolytes. [

11,

12,

15]. While considerable progress has been made in understanding phytohormone roles in the plant response to abiotic stress, there are still gaps in our knowledge, including a clear understanding of the complex effects of hormonal crosstalk and multiple stresses, understanding the potential trade-off between induced stress responses and yield, as well as the effects of innate vs induced tolerance in different plant varieties. Moreover, the rationale behind most of these cited studies is to provide an understanding of molecular responses to water stress, with a view to breeding new plant varieties with improved drought resilience [

3]. In contrast, there are considerably fewer studies, particularly in perennials, that use combined measurements of phytohormonal and transcriptional biomarkers to understand how treatments can be applied to established cultivars to induce greater tolerance to subsequent drought stress in existing plantings, in a process known as priming [

16,

17,

18].

Treatments that can be used to condition plants to improve their stress tolerance include gradual exposure to a stress factor, e.g., controlled water deprivation [

19], and/or the exogenous application of compounds (priming agents) such as phytohormones and plant metabolites [

20]. Experimental applications of phytohormones, including salicylic acid (SA) [

21,

22], cytokinins (CK) [

23], and ABA [

24], have demonstrated potential benefit in improving drought resilience. However, there are few commercialized priming agents to mitigate the impacts of drought stress, and these are largely restricted to use in annuals, rather than woody perennials because of the additional biological complexities and time constraints of slower growth cycles associated with the latter. The impact of severe drought on existing plantings of perennials has more durable and deleterious effects than on annuals, with the time taken to reach full production after re-planting requiring years, hence the use of priming agents in perennials merits further research. One suitable candidate for such research is acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM), a commercially available SA analogue that is often used to induce biotic stress resistance. Exogenous application of SA activated stress response molecular pathways and alleviated water stress in watermelon, rice, wheat, and barley [

25,

26,

27,

28]. SA also triggered the accumulation of ABA under both normal and salinity stressed tomato plants, which enhanced osmotic adaptation and improved photosynthetic pigments and growth [

29]. Furthermore, application of ASM has been shown to enhance drought tolerance in creeping bentgrass [

30], induce stomatal closure in Japanese radish [

31], and stimulate ABA accumulation in kiwifruit [

32], which might improve tolerance to osmotic stress.

The exemplar crop chosen for this study was apple. Drought stress can affect apple quality and yield in both the current and subsequent seasons [

33,

34], and may cause tree death. Grafted apple trees take at least seven years to reach full production, and breeding of new cultivars can take up to 15 years [

35,

36], leaving the industry with a significant recovery period should existing plantings suffer severe drought. Commercial apple plantings comprise scions grafted onto rootstocks, with the rootstocks performing a key role in controlling tree growth and drought tolerance characteristics [

37]. Rootstock genotype has been shown to have a major influence on the response of the scion to water stress [

38]. Malling 9 rootstock (M9) is a commonly used strong-dwarfing rootstock thought to confer some drought resistance via ABA-mediated control of stomata [

39]. Cornell-Geneva 202 (CG202), a semi-dwarfing rootstock, appears to have reduced drought tolerance relative to M9 [

40], but the reverse result has also been observed [

41]. Results from most studies on apple rootstocks are based on empirical physiological data without any matching data on biochemical and genetic biomarkers [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

To address gaps in our knowledge, the aims of this study were:

To identify robust phytohormonal and transcriptomic biomarkers that align with physiological drought responses in two apple rootstocks

To determine the effect of exogeneous ASM application on these biomarkers and compare induced responses in the two rootstocks

The underlying hypotheses are that phytohormonal and transcriptional markers can be used to study drought responses in rootstocks from a metabolic angle, and that the SA analogue, ASM, can be used to induce/prime for drought resistance in a woody perennial (apple).

The study reported here provides the first results from a research programme that adopts a novel approach by the combined use of selected phytohormones and genetic targets, previously associated with stress response and signaling in apple and annual model plants. This provides more understanding into drought resilience mechanisms at a systems level than use of either group of biomarkers on its own and could be used in the future to examine the relationship between the timing and the amplitude of the biochemical and transcriptional responses.

3. Discussion

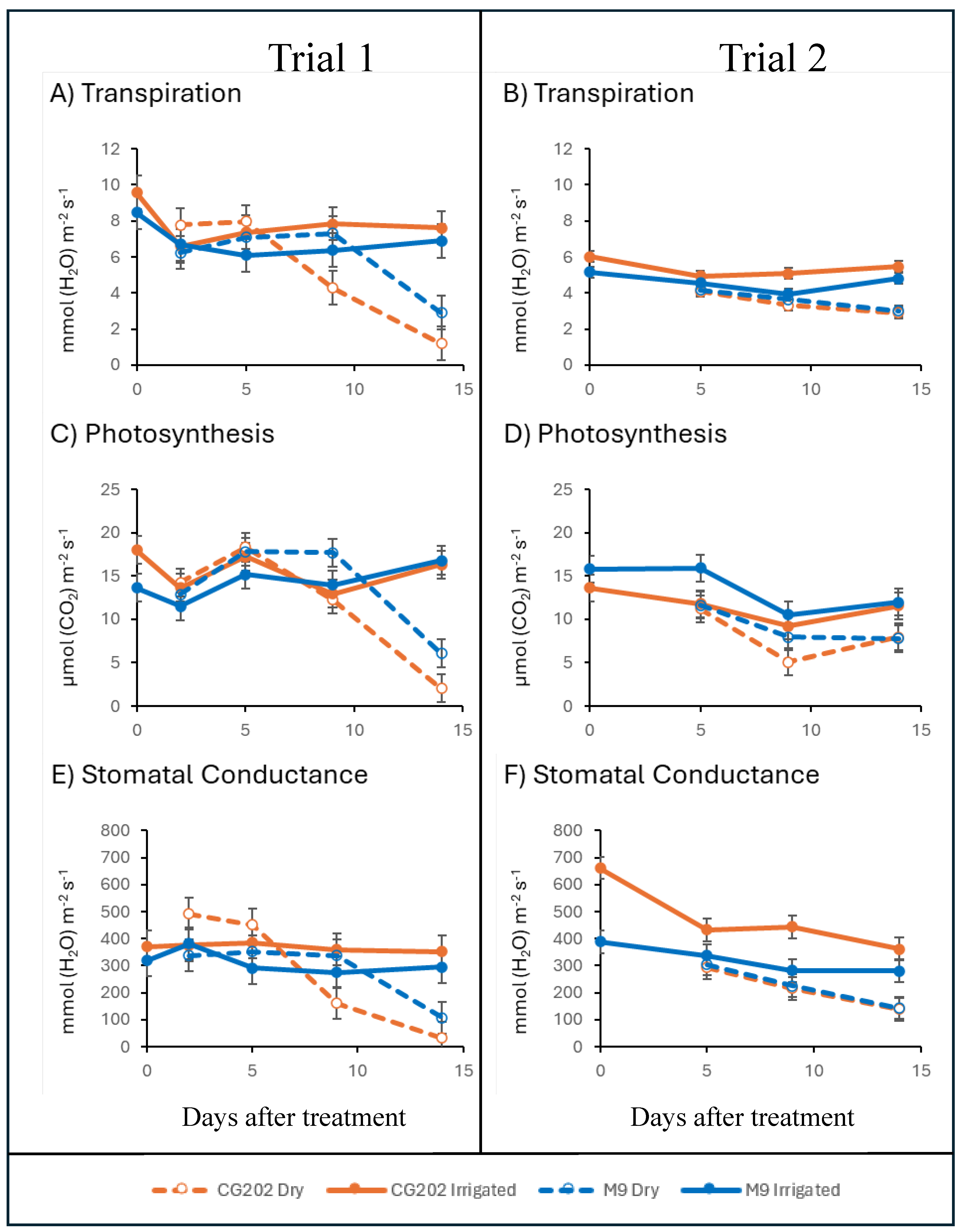

This research aimed to establish if transcriptomic and phytohormonal markers could assess the response to drought in dwarfing (M9) and semi-dwarfing (CG202) apple rootstocks, and whether pre-treatment with the SA-analogue, ASM, could induce drought resistance. Drought resulted in a significant decrease in transpiration, photosynthesis and stomatal conductance in both rootstocks. The physiological responses occurred earlier in CG202 than M9 in both trials, suggesting a quicker response to water stress in CG202. Moreover, there was faster and greater accumulation of ABA metabolites (especially in Trial 2), and stronger upregulation of ABA pathway genes (in both trials) in CG202 than in M9. Biochemical and genetic reactions were more intense in the root than in the leaf tissue, with the roots being the primary site of water stress perception. Application of ASM had no discernable effect on the physiological, transcriptomic and biochemical parameters measured. Taken together, these data suggest that statistically significant, differentially accumulated biochemical compounds (ABA, PA, cisOPDA, and IAA) and gene families (CYP707A1/A2, NCED3, RD29B, PYL4, MdbHLH130 and SDH1) showing consistent trends in this study were suitable biomarkers of the drought response and that ASM was not an effective primer – at least within the constraints of this study.

Gas exchange measurements showed that the Dry treatment significantly affected both rootstocks in both trials leading to a significant reduction in the transpiration rate, photosynthesis, and stomatal conductance. Transpiration and stomatal responses generally occurred earlier in CG202 (after 5-9 days without water) than in M9 (after 14 days without water). It is not possible to conclude if the earlier responses in CG202 reflect greater sensitivity or greater resistance and/or resilience to drought. Drought resistance can be described as the ability to maintain growth during a drought and resilience as the ability to recover growth after a drought [

45]. The gas exchange data indicated that water stress imposed by day 14 was possibly too severe, as both rootstocks had low photosynthetic rates, transpiration rates and stomatal conductance. The plants were showing severe physical symptoms of water stress. which in turn impaired health equally in both rootstocks, complicating any discussion of drought resistance. Whilst not a direct measurement of stomatal aperture, stomatal conductance measures the rate of gaseous exchange (e.g., CO2 exchange) through the stomata, with a drop indicating stomatal closure [

46]. ABA-mediated stomatal closure is a common physiological response to drought [

47], which aims to conserve water/limit water loss, as measured by transpiration rate, but which also limits gaseous exchange necessary for photosynthesis. In both trials, 14 days without water resulted in a 50% loss in pot weight and photosynthetic rates were significantly decreased to the same extent in both rootstocks. Visually, CG202 and M9 exhibited similar physical appearances indicative of severe water stress, i.e., leaf wilting/chlorosis, particularly in the top 25% of each plant. For future studies, especially on potted plants, we would recommend a less severe water stress, for example shorter periods of drought deprivation followed by rewatering cycles [

40], and/or using water stress treatments that consist of percentage reductions of the maximum water content at pot capacity [

44]. Recovery data after a period of re-watering were not collected in this study, so it is also not possible to comment on drought resilience. Recovery following dehydration stress is perhaps of greater significance in perennial crops than annuals and will be considered in our future studies. Information in the literature about the relative drought resistance and/or resilience of CG202 and M9 is conflicting, with Xu and Ediger [

40] suggesting that M9 is more drought resistant than CG202, which they defined as more efficient CO

2 assimilation, higher net photosynthesis, and smaller declines in stomatal conductance, i.e., more stringent stomatal control, and reduced water use/lower transpiration rates during stress. In contrast, Choi et al. [

41] focused on measuring soil and water potential, water use efficiency (WUE), and vegetative growth and dry matter, both during drought stress and recovery periods, and found CG202 to be more drought resilient than M9. They observed that although M9 had better WUE than CG202 at the height of water stress, CG202 exhibited a lower leaf:fine root ratio than M9, which is thought to lessen the impact of xylem embolism (air-filled tracheids and/or vessels) on impairing stem water transport, thus contributing to better recovery post drought stress. The anomalous findings between these studies may also be associated with differences between resistance and resilience definitions as well as experimental differences including the age of the rootstock-scion systems used (1-3 years), the scions used for grafting (‘Ambrosia’ vs ‘Fuji’), the duration and frequency of the drought regimes imposed as well as highly variable environmental conditions and soil characteristics in field trials. Moreover, these results are not directly comparable to the current study on rootstocks alone because the published studies were on grafted rootstock-scions. However, whilst scion will affect results, generally the rootstock is considered to play the more important role in determining drought resilience in grafted apple [

38,

48]. Interestingly, Xu and Ediger [

40] found that rootstock choice influenced both stomatal size and density on a common scion, Ambrosia™, with higher density and smaller sized stomata found on ‘Ambrosia’ leaves grafted onto M9 versus CG202. This may in part explain the more stringent stomatal control that they observed in the ‘Ambrosia’/M9 grafted plants.

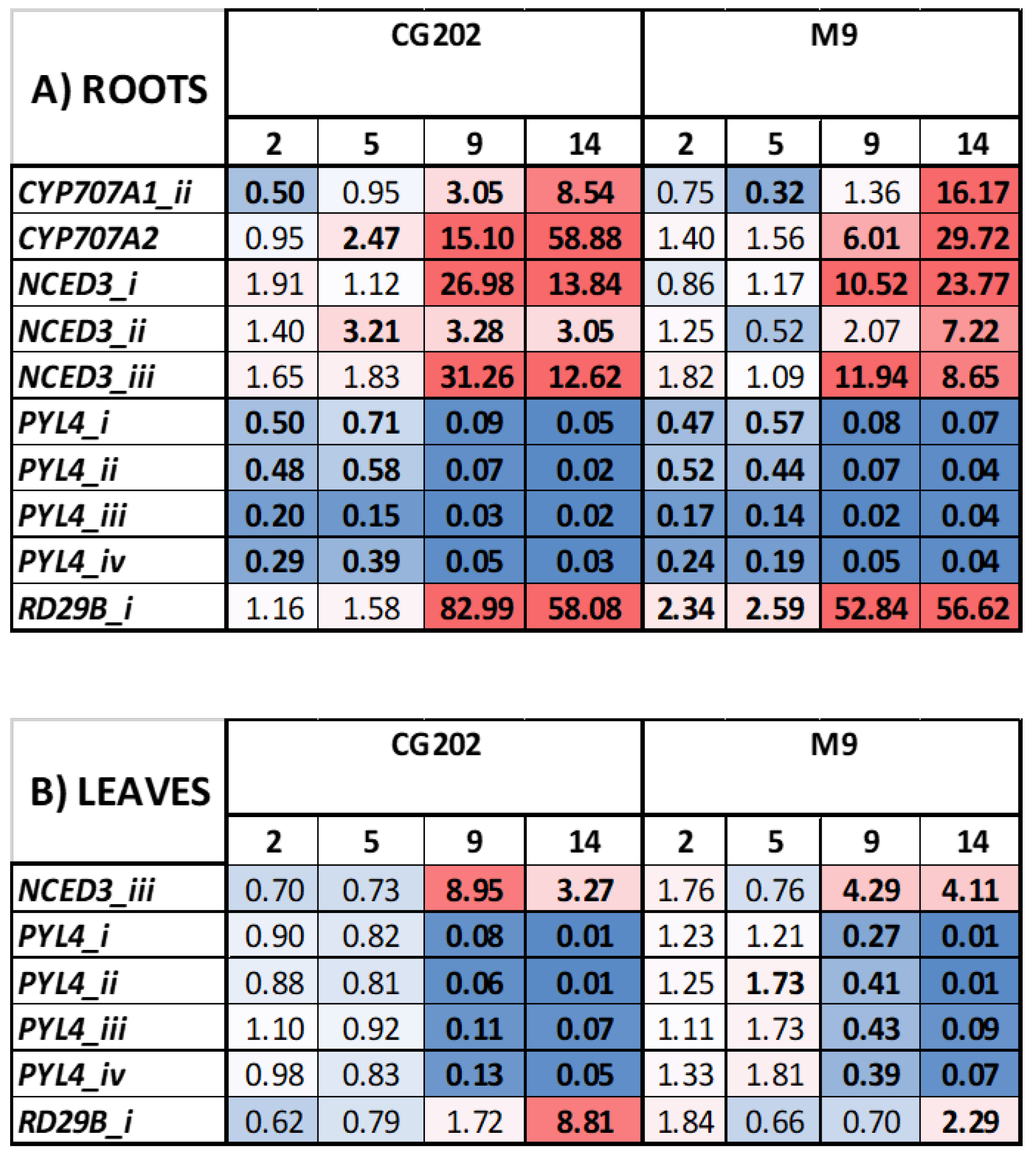

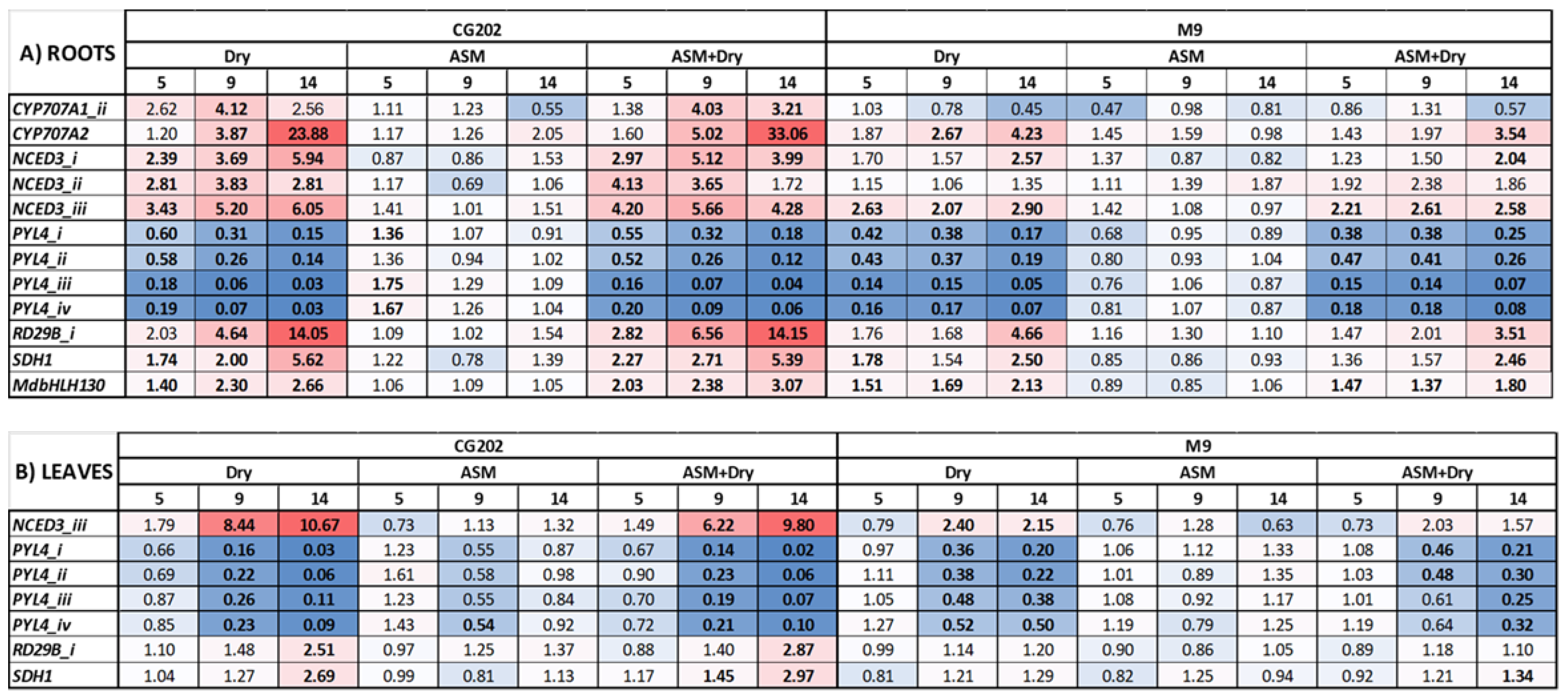

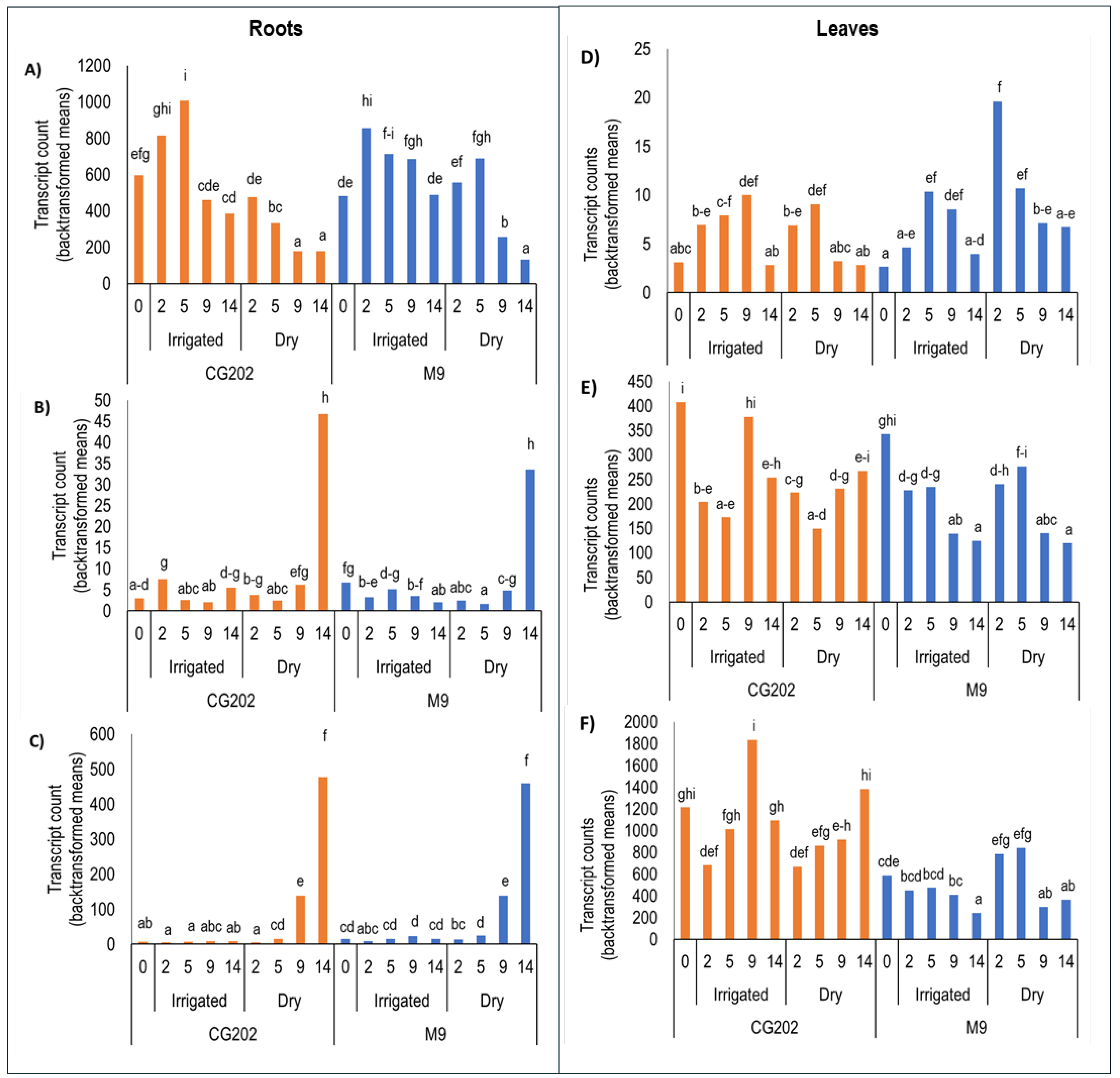

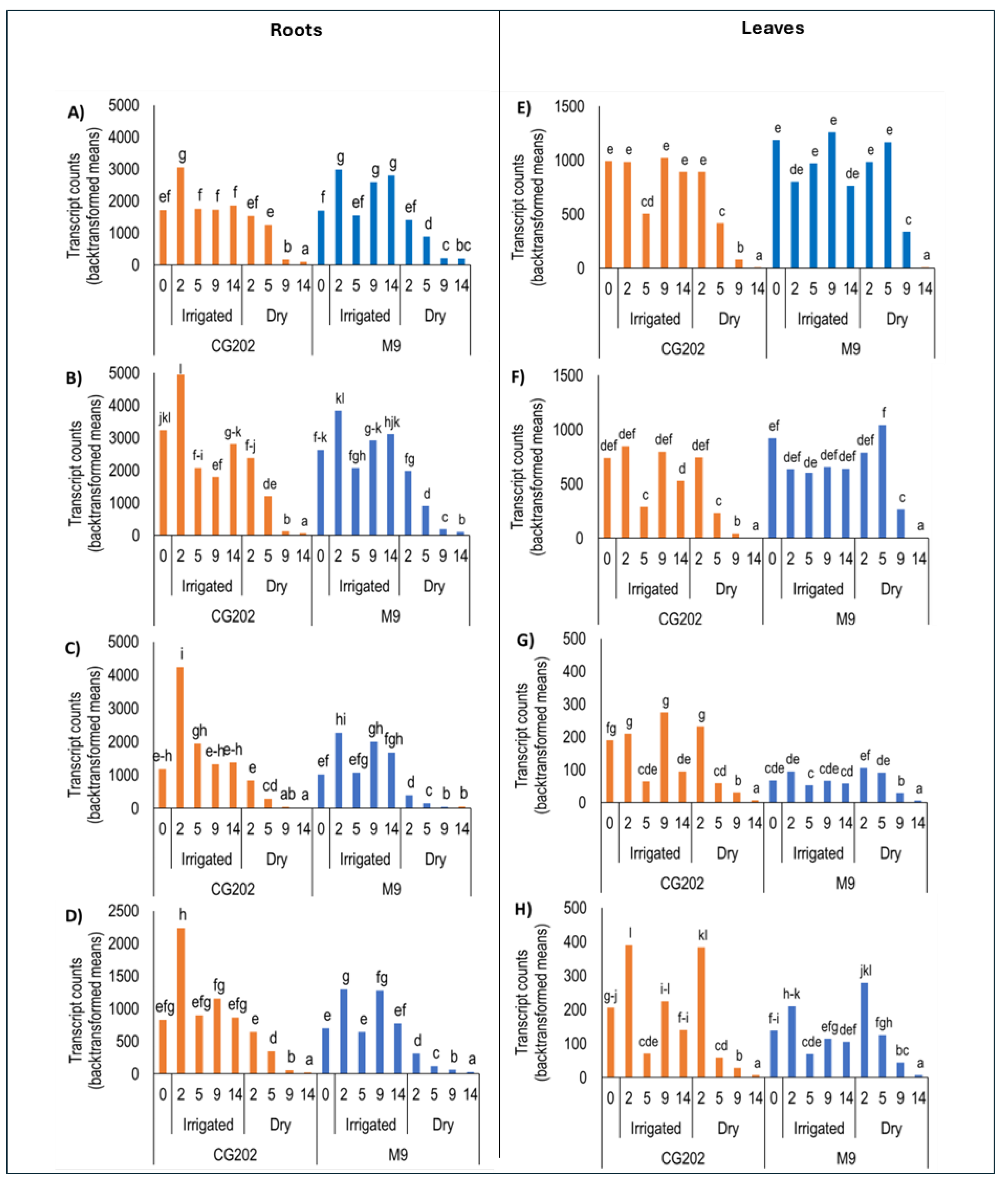

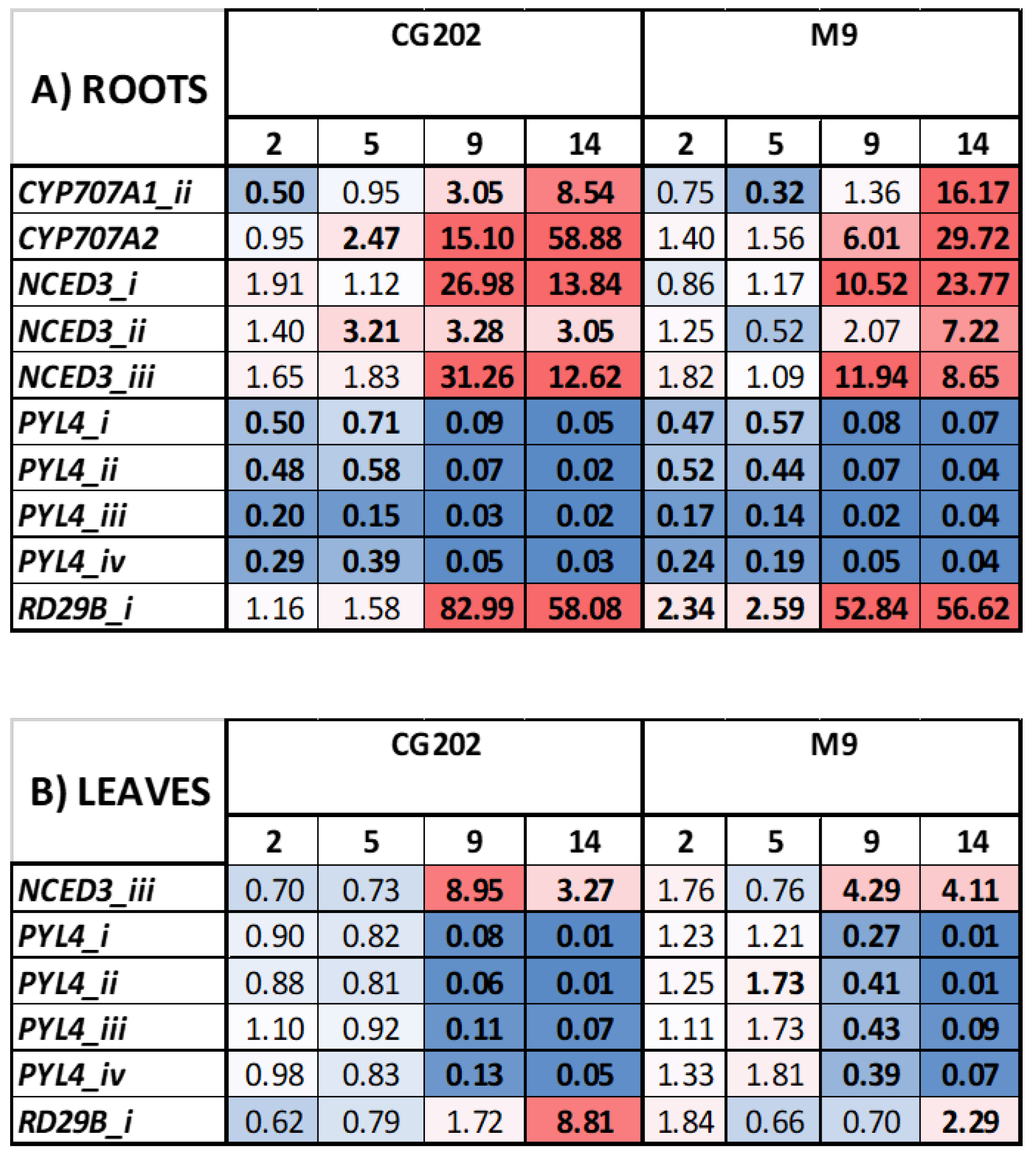

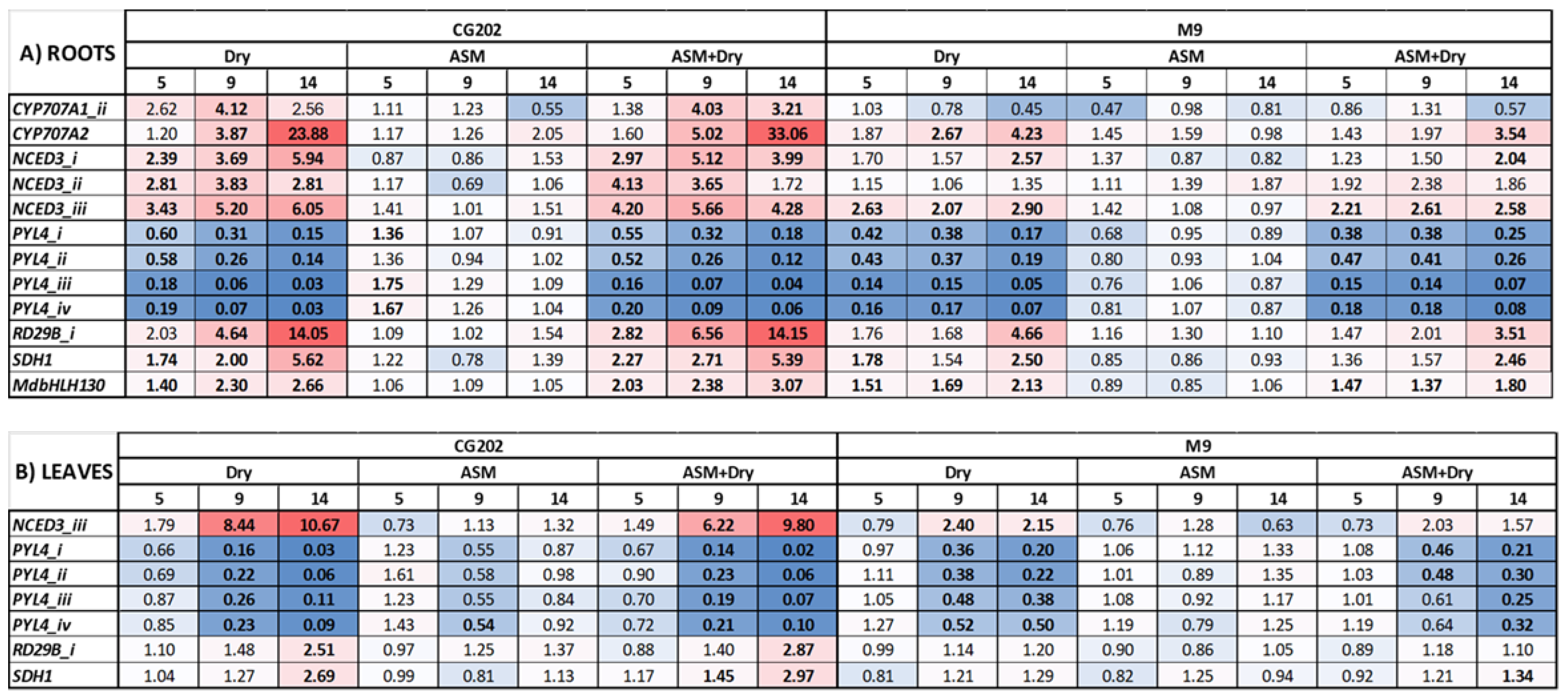

To select suitable (transcriptional) gene markers, potential candidates needed to show convincing responses to transcriptional regulation/mRNA expression associated with the drought response, i.e., statistically significant differential expression, consistent patterns over the two trials (for those genes common to both gene sets) and responses that mirrored physiological and biochemical changes. Gene families meeting these requirements were the PYL4, CYP707A1/A2, NCED3, RD29B, MdbHLH130, and SDH1 gene families. Apart from the first gene family, these all started with low basal levels of expression (less than 50 copies) but were significantly upregulated with drought, with a faster and more elevated response occurring in the root tissue of CG202 than M9. The same trends were apparent in leaf tissue of both rootstocks, but overall, upregulation was less than in the root tissue, although expression within some gene families was sometimes tissue- and isoform-specific. The PYL4 gene family was expressed at high basal levels in irrigated plants in roots (up to 5000 copies in both rootstocks) and leaves (up to 1000 copies in both CG202 and M9) and decreased significantly with drought, with greater downregulation occurring in GC202 than M9. This pattern of downregulation was also found for this subfamily in Arabidopsis [

49]. All these gene families, except SDH1, are directly or indirectly involved with ABA metabolism. As well as modulating stomatal closure, increased ABA concentrations are known to increase the root:shoot ratio and promote the growth of lateral roots in Arabidopsis [

10]. This study did not analyse the transcriptional expression of genes where the predominant modes of regulation identified in the literature involved post-transcriptional, post-translational or epigenetic changes.

Intensity of the stress responses, e.g., differential expression of genes in the Dry treatment, was greater in Trial 1 than in Trial 2. This was reflected in the environmental data, where the temperature was hotter in Trial 1 than in Trial 2, especially during the first few days where the maximum temperature differed by approximately 8°C and the minimum temperature by 10°C degrees. High temperatures often accompany drought in nature and are likely to have had an additive effect [

50] on the stress response seen in Trial 1. However, statistical comparisons between Trials 1 and 2 were not made because of the many variables that would complicate interpretation, e.g., different plants, seasonal factors, temperature differences.

CYP707A1/A2 genes were significantly upregulated by drought, especially in CG202 vs M9 roots. The CYP707A1/A2 enzyme groups are key ABA catabolic genes encoding ABA 8’-hydroxylases that convert biologically active ABA to an unstable intermediate 8’-hydroxy-ABA that is cyclized to the inert PA metabolite [

51]. Endogenous concentrations of ABA are thought to be controlled by a balance between biosynthesis versus catabolism, transport to different parts of the plant, and cycling between inert glycosylated storage forms (ABA-glucose ester) and more biologically active aglycone pools [

10]. However, the role of CYP707A family is so crucial to regulating internal ABA concentrations that mutants deficient in CYP707A activity accumulate more ABA than lines overexpressing ABA biosynthesis enzymes [

10]. The different CYP707A enzyme groups are known to have different spatial and temporal patterns of expression that reflect slightly different physiological roles [

10]. For instance, CYP707A1 is most important for ABA catabolism midway during seed development and is localized within the embryo whilst CYP707A2 regulates ABA levels during late stages of seed maturation/germination and is found in both the embryo and endosperm in Arabidopsis [

52]. The transcript levels of all CYP707A groups were induced by dehydration in Arabidopsis, with CYP707A1 shown to play an important role in regulating ABA pools in the stomatal guard cells [

53]. In the current study, tissue-differentiated gene expression patterns were also observed for the different CYP707A groups and isoforms within those groups. Basal expression levels of

CYP707A1_ii and

CYP707A2_i were up to 240-fold more abundant in leaves than roots and remained high in leaves throughout the experiment but increased significantly in roots in the Dry treatment. The reverse was true for

CYP707A1_i, where baseline levels were up to 120-fold greater in roots than leaves, and transcript numbers decreased by up to 50% in roots in the Dry treatment. These observations may suggest a more fundamental role for

CYP707A1_ii and

CYP707A2_i in regulating ABA in the leaf guard cells, whereas reduced abundance of

CYP707A1_i in the roots in the Dry treatment would lead to increased ABA concentrations, possibly promoting adventitious root formulation.

All isoforms in the NCED3 family were also significantly upregulated in the Dry treatment in roots, and

NCED3_iii in leaves, with greater upregulation in CG202 than in M9. The NCED3 family is the key regulator of ABA synthesis in Arabidopsis, with increased ABA synthesis being a pivotal response to drought stress [

11,

12,

13]. Upregulation of ABA synthesis was greater in the roots rather than leaves of both rootstocks, but especially in GC202, a result mirrored in a drought study in kiwifruit [

54]. Although ABA is thought to be predominantly synthesised in the leaves where stomata are located, synthesis in the roots does occur [

55]. Moreover, ABA synthesis in one plant part and transport to another is a well-established phenomenon, with Manzi et al. [

56] showing that hormonal transport from aerial organs contributed to sustained to ABA accumulation in long-term drought-stressed tomato roots, and Hu et al. [

55] data supporting transport of ABA in the reverse direction. In addition, Hu et al. [

55] showed that the initial site of water stress governs the pattern of ABA synthesis, with synthesis occurring first in the roots when root tissue is directly stressed and vice versa when water stress was imposed directly on peanut leaves. In the current study, roots are the first part of the plant to sense the water shortages and therefore could be expected to respond strongly/rapidly in terms of ABA synthesis, with a stronger induced response in CG202 than M9. Further spatial expression profiles underlying ABA synthesis/catabolism in different tissue types could be an interesting avenue for further study. Overall, the significant increase in both NCED3-mediated ABA biosynthesis and CYP707A catabolysis suggests that drought appears to be stimulating ABA metabolism as a whole, with a stronger transcriptomic response occurring in CG202 (especially in the roots) than in M9.

Response to Dehydration 29B, isoform i (

RD29B_i) was upregulated in both trials of the current study, with the strongest responses occurring in CG202 roots. The RD29B family are ABA-dependent genes involved in downstream parts of the ABA signaling cascade that have been shown to be upregulated in response to both drought and to application of an effective drought priming agent (a plant growth promoting rhizobacterium) in Arabidopsis [

57]. The RD29B phenology tree in apple consists of two distinct branches, both of which were quite distant from RD29B in Arabidopsis, indicating evolutionary divergence. Only one of the family members,

RD29B_i was significantly upregulated in response to drought in the current study and mainly in roots, which possibly points to the different tissue-specific roles played by members of the same gene family, with a strong drought-induced response in root tissue.

bHLH130, a TF, is thought to be involved in stomatal regulation, with bHLH TFs identified as contributing to improved drought tolerance in transgenic apple calli [

3]. Dehydration-induced bHLH130 has been shown to regulate stomatal closure, increased the expression of ROS-scavenging and stress-related genes in tobacco leading to increased tolerance to drought [

58] and belongs to the same clade as ABA-Responsive Kinase Substrate 1 (AKS1) from Arabidopsis. Takahashi et al. [

59] showed that AKS1 is modulated by ABA which causes the inhibition of KAT1 expression by releasing AKS1 from interaction with the KAT1 protein, thereby limiting stomatal opening. The basis of this release is the monomerization of AKS1 through phosphorylation by ABA-responsive SnRK2 kinases. This stomatal response mediated by AKS1 is likely a late process and may, for example, reduce the reopening of stomata after severe drought episodes. In the current study, a significant upregulation of

MdbHLH130 of more than 2-fold was observed only in roots of GC202, and in M9 to a lesser extent, which does not fit with the leaf stomatal response theory. However, baseline abundance of

MdbHLH130 was up to 2.8-fold greater in leaves than in roots, suggesting that its main role in stomatal closure regulation in leaves is a basal rather than an induced response. This gene marker was only introduced into the second gene set used to probe Trial 2, so further trial data are required to verify this result.

Sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH1) is involved in sugar metabolism converting sorbitol to fructose [

60]. This marker was newly introduced in Trial 2 and was the most abundantly expressed of all the genes in that trial, with the greatest expression occurring in GG202 roots and leaves (basal levels of around 10,000 copies increased to around 30,000 copies with drought). High abundance of SDH1 in root and leaf tissues is consistent with the central role of sugar metabolism in plant growth and source/sink relationships. Potential dual roles of this enzyme in the drought response could include modulating cellular osmotic adaptation, which is a common response in water deficiency, and/or the fructose could act as an emergency store of energy that can be utilised after an initial increase in sorbitol to adapt to the water stress. Emergency energy stores become particularly important once photosynthesis is limited by reduced external gaseous exchange associated with stomatal closure.

The PYL4 family acted as a negative marker of drought response, with significant downregulation occurring with drought in both rootstocks and tissue types, but with a more extreme and rapid response occurring in CG202 than M9, especially in root tissue. A particular class of protein phosphatases (PP2Cs of the A clade) inhibit a key node of the ABA response by binding SnRK2 kinases, preventing these kinases from activating downstream ABA signaling responses [

10]. These PP2Cs are kept quiescent and effectively sequestered by the PYR/PYL ABA receptor family in the presence of ABA. There are different classes of PYR/PYL ABA receptor proteins which include dimeric and monomeric classes as well as classes with different affinities to ABA and different expression profiles. The dimeric PYL classes (e.g., PYR1/PYL1-2) show lower affinity/higher dissociation constants for ABA (>50 µM) than monomeric PYLs (e.g., PYL4, PYL9, ~1 µM) but in the presence of their matching PP2C-A clade protein partners they form ternary (PP2C sequestering) complexes with much higher ABA affinities in the 30-60 nM range [

61,

62]. Dimeric PYR/PYLs are compromised in the surface that interacts with their PP2Cs partners and are therefore highly dependent upon ABA to adopt a PP2C binding/sequestering conformations. Monomeric receptors are able to interact to some degree with PP2Cs even in the absence of ABA. Monomeric PYL4 shows high expression across multiple tissues and therefore probably plays a critical role in sequestering PP2CAs [

63]. In support of this theory, the four members of the PYL4 family tested in this study also showed high basal expression in roots (up to 5000 copies) and leaves (up to 3000 copies) of both rootstocks. In maize, PYL4-like genes showed differential expression patterns in leaves with some members of the PYL4 family showing decreases in response to ABA while others showed increases [

64] whilst in roots, PYL4 showed dose-dependent ABA down-regulation. PYL4 is rapidly downregulated in response to drought in Arabidopsis [

49], and drought-induced downregulation of the PYL4 family was also observed in roots and leaves of another dicot, kiwifruit, with the degree of the response being more extreme in roots than leaves [

54]. Interestingly the PYL9 family is thought to play an important role in regulating lateral root growth, and coordinated signals sent through PYL9 are an important component of drought recovery [

65], with over-expression of PYL9 also shown to provide tolerance to drought in both Arabidopsis and rice [

66]. However, the PYL9 genes tested in Trial 1 did not show any significant differential response to drought and so were excluded from Trial 2. One possible explanation for this anomaly is that the complete family of PYL9-like genes in apple was not included in this study, and rather representative members chosen from each of the distinct branches in the phenological tree were used. It is therefore possible that we did not select the most responsive members of this gene family.

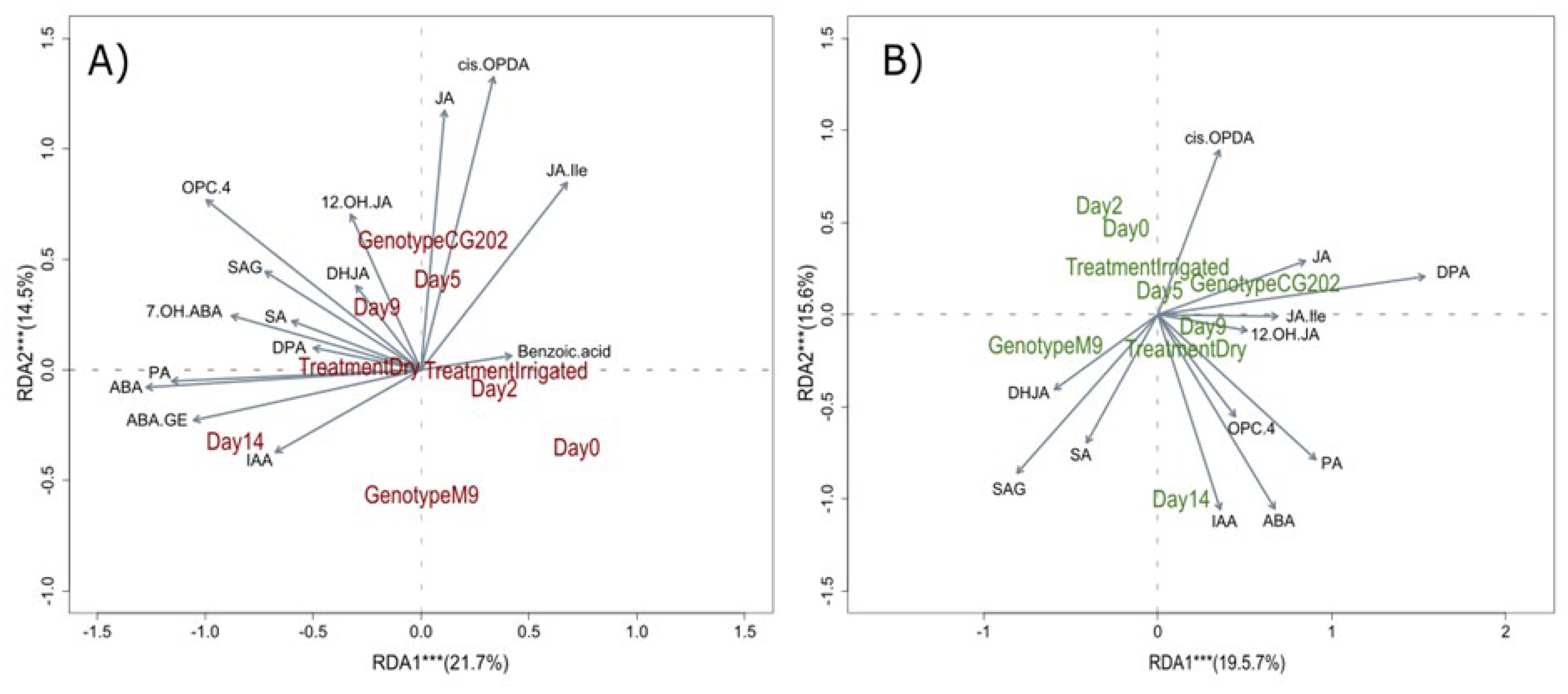

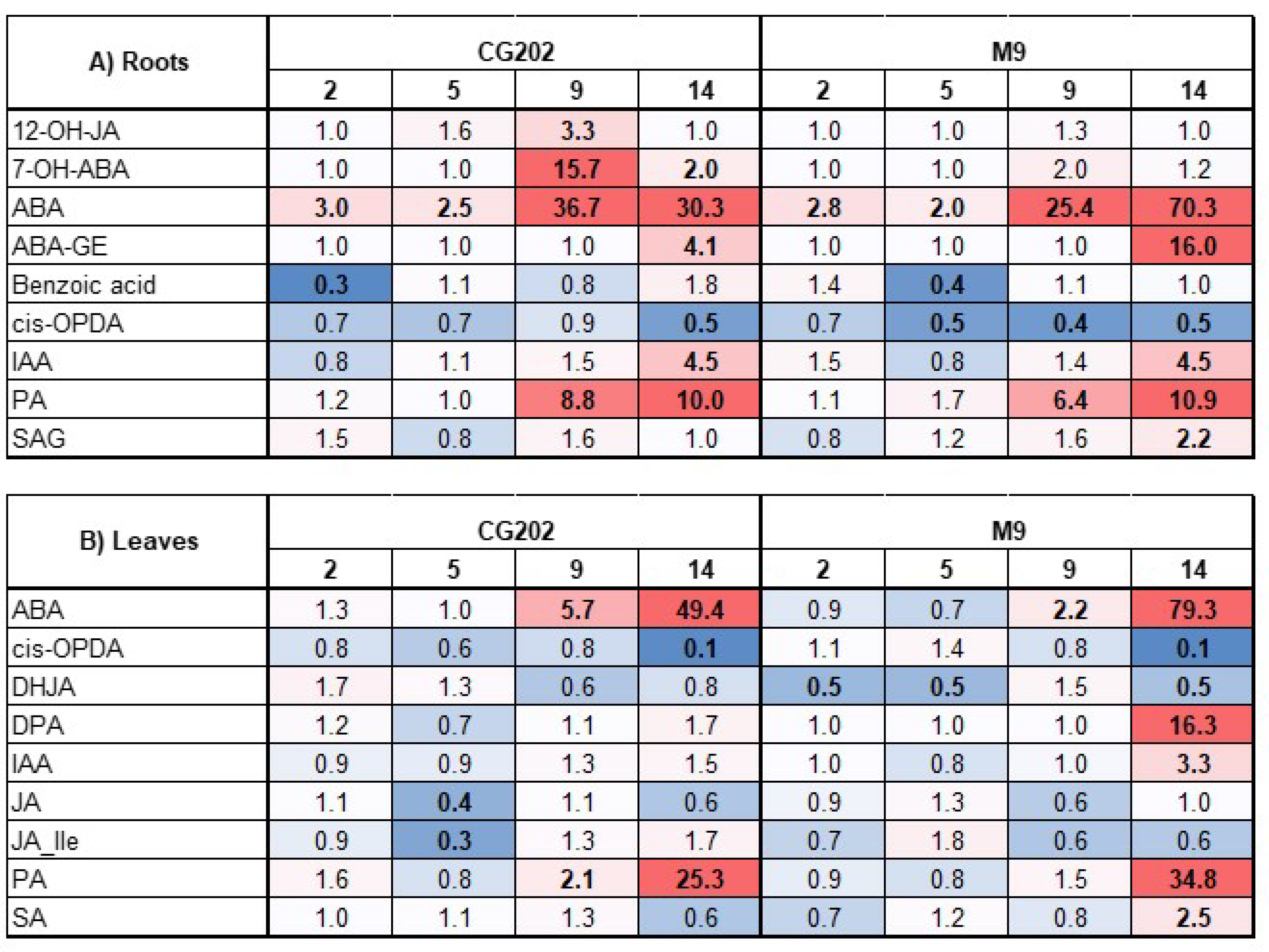

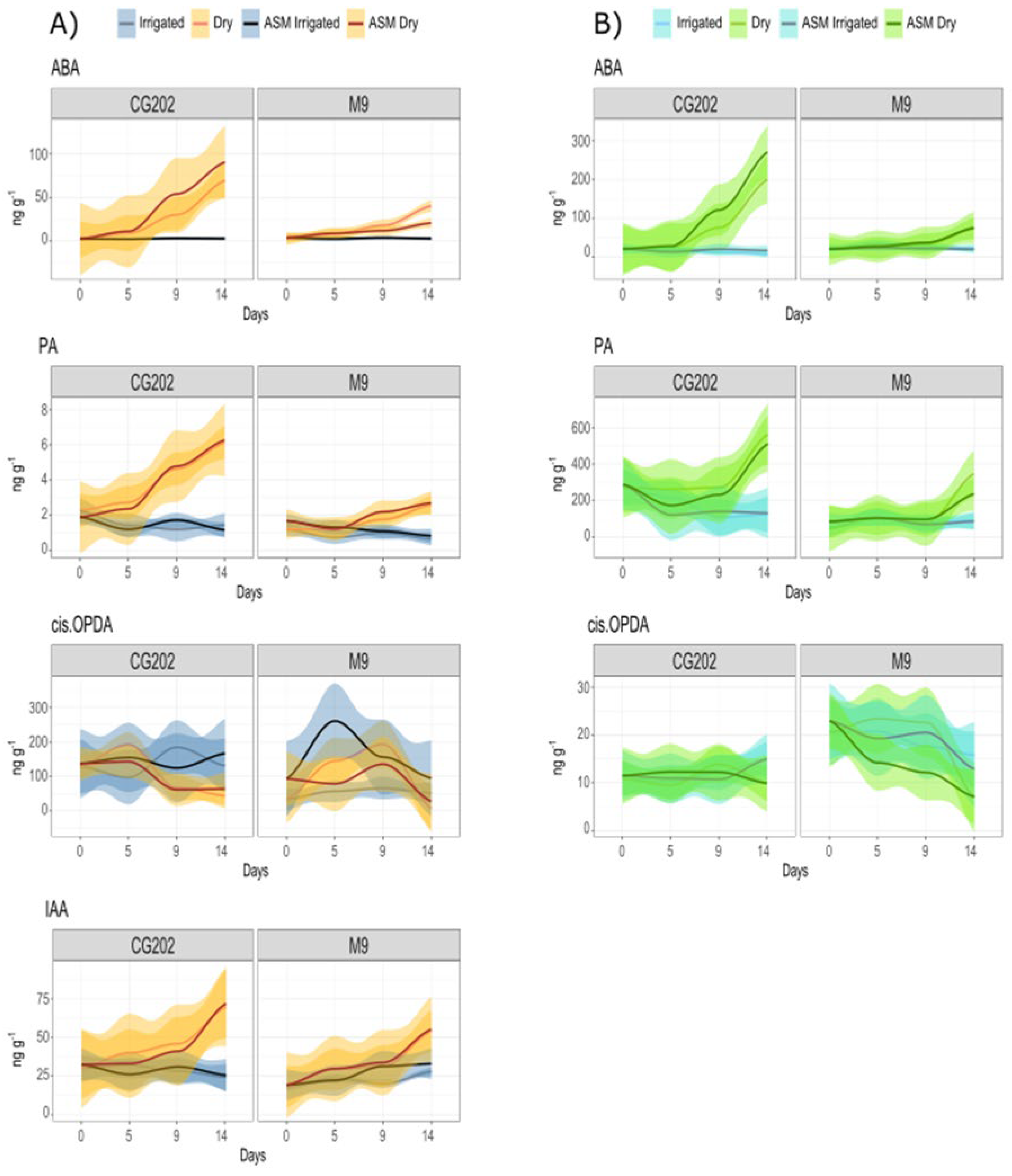

Four main classes of phytohormones and their metabolites were quantified in this study, and their compositions were affected by tissue type, rootstock genotype and drought treatment, with consistent trends across both trials. In both genotypes, ABA and SA-derivatives accumulated in leaves, while higher concentrations of jasmonates and IAA were quantified from roots. While these phytohormones can be produced in multiple cell types and organs, they are predominantly synthesized in chloroplasts (SA, JA) or leaf cells (ABA, IAA) and transported where needed [

67]. Root tips also synthesise IAA as key regulator for root development in crosstalk with ethylene and jasmonates. While the most bioactive jasmonate form, JA-Ile, is mainly known for its roles in plant defenses against biotic stresses, it also promotes lateral root formation by inhibiting primary and adventitious roots in crosstalk with auxin [

68]. In this study young/developing root tissue was sampled in contrast to mature leaves, which may explain the elevated concentrations of IAA and JA-Ile in actively growing root samples. The genotype comparison showed that CG202 produced constitutively higher concentrations of abscisates and jasmonates in both roots and leaves, while M9 had higher SA content, especially in leaves. A recent study highlighted increased pest-resistance of CG202 [

69], which is likely instigated by higher basal levels of JA-Ile and demonstrates the multifunctional role of this phytohormone. SA is also commonly associated with its role in mitigating biotic stresses, however, it is also known to induce stomata closure and consequently reduce photosynthetic activity in a variety of crop plants [

70]. Higher basal concentrations of SA might compensate for lower ABA in regulating stomata movement in M9 when compared to CG202.

ABA is the primary phytohormone associated with drought stress and stomata closure [

10] in plants and in this study its concentration increased rapidly in roots and after 9-days in leaves of both rootstock genotypes in response to water limitation. This was also observed for its catabolite PA, which forms spontaneously from 8’-hydroxy-ABA (8-OHABA), and might exhibit some residual physiological activity to extend ABA-regulated functions [

71]. Both phytohormones were recognised as positive chemical markers for drought responses in roots and leaves. Cytochrome P450 monoxidases catalyse the hydroxylation of ABA to 8-OHABA and are encoded by the CYP707A gene family. CYP707A2 was identified as its most drought-responsive member in this study, with transcript levels magnitudes higher in CG202 than M9. Together with increased expression of the ABA biosynthesis gene NCED3_iii in droughted CG202, these findings indicate that ABA metabolism is genetically upregulated in this rootstock genotype.

In roots only, IAA was highlighted as positive chemical marker for drought stress as it increased significantly after 14-days without irrigation in both genotypes. This aligns with observations in tobacco, where water deficit induced IAA accumulation in roots but not in leaves [

72]. Moreover, drought-induced IAA was shown to increase the formation of first and second order lateral roots, as a likely strategy to increase water uptake and a similar mechanism is possible for apple rootstocks.

In contrast, cis-OPDA was identified as a negative chemical marker to water limitation. While concentrations were higher in roots, they decreased in response to extended drought in both leaves and roots of both genotypes. This drought-induced downregulation of cis-OPDA in apple rootstocks is difficult to explain and requires further investigation, as it contrasts with observations from studies using annual plants, which commonly report an upregulation of this oxylipin in response to stress [

73]. While cis-OPDA is the biosynthetic precursor of JA, it is known act as a signaling molecule independent of JA responses. Besides acting as transcriptional activator for stress-related genes [

74], it was shown to accumulate in guard cells and partake in regulating stomatal closure [

75], thus mitigating drought stress.

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the use of phytohormones as priming agents to mitigate negative effects of drought in plants [

76]. ASM (a functional analogue of SA) was an excellent candidate to assess for potential drought priming in our apple system because SA has been previously shown to ameliorate the negative effects of drought through improving the photosynthetic performance, stimulating SA-mediated defence responses and enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes [

26,

77]. ASM application also reduced transpirational water loss through inducing stomatal closure in the monocot, creeping bentgrass [

30,

78]. However, ASM application did not alter any of the physiological factors measured in the current study, in contrast to results shown in watermelon, rice, wheat, barley and tomatoes [

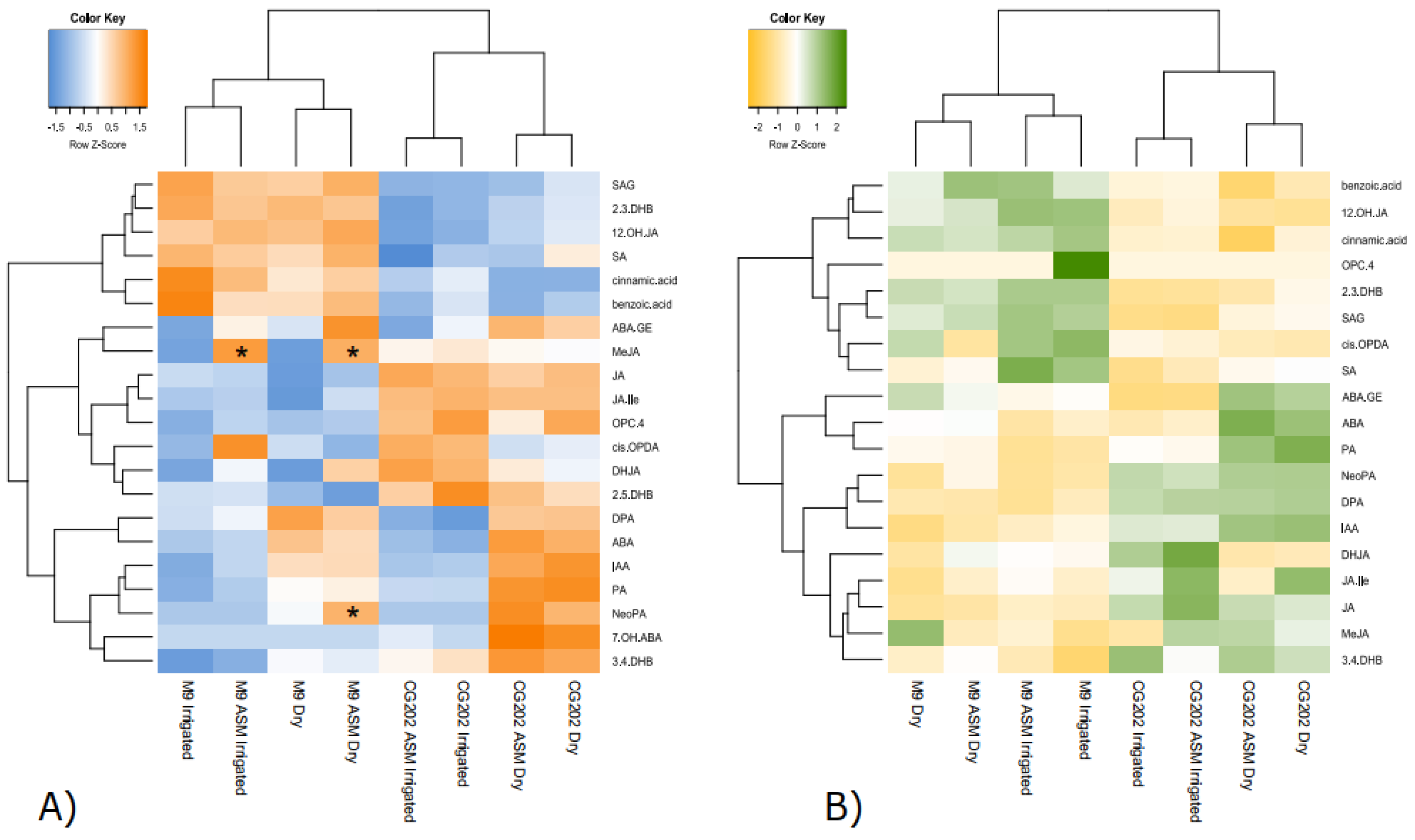

25,

27,

29]. Differences between the current study and ours might be due to rate and frequency of ASM application, and/or timing of biomarker measurement relative to ASM application. However, one lasting response post-application was genotype-specific and resulted in increased MeJA concentrations in M9 roots in both Irrigated and Dry plants. As a precursor to JA-Ile production, MeJA might promote lateral root formation in ASM-treated M9 rootstocks but whether it mitigates drought-stress responses is unlikely because no other physiological, chemical or genetic markers were altered in response to its application

This study identified candidate phytohormonal and transcriptomic ‘drought’ biomarkers that correlated either positively or negatively with physiological responses to drought in M9 and CG202 rootstock plants. The transcriptomic biomarkers encompassed a wide range of functional processes associated with the main stress-response hormone, ABA, including biosynthesis (NCED3), catabolism (CYP707A1/2), and the signaling response (PYL4, RD29B). The biochemical markers also represent three phytohormone pathways associated with abiotic stress responses, i.e., ABA, PA (ABA pathway); cisOPDA (JA pathway); and IAA (Auxins). The development of robust drought biomarkers is essential to facilitate the development of stress mitigation strategies that rely on increased plant tolerance to drought. This applies both to breeding programmes and to selection of chemical and biological agents that may prime or condition plants for greater drought resilience, with the latter enabling protection in existing plantings. The characterisation of responses to moderate and severe drought across different apple rootstock genotypes can aid identification of genetic factors that are critical for drought tolerance. This would include integration between plant physiological, transcriptomic and phytohormonal data and environmental modelling to enable the selection of genotypes more suited to the different drought scenarios.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Temperature data and respective sample time points (arrows) in Trial 1 and Trial 2. Tissue samples were collected, and physiology measurements were recorded between 10:00 am and noon on each day. Figure S2: Heat map presenting fold-change gene expression data in A) root, and B) leaf tissue, induced by drought stress conditions in Malus domestica CG202 and M9 rootstocks after 2, 5, 9, and 14 days without water, in Trial 1. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. There were five replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. Gene expression was quantified by PlexSet® NanoString using CKB4, FYPP3 and GPAT1 as reference genes. Genes of interest are listed in the left-hand column. Numeric values give the fold changes relative to irrigated plants, sampled at the same time periods. Red colouration indicates a fold-increase, blue a fold-decrease, and white is no fold change relative to the control. Colour intensity is indicative of the degree of change, but all fold increases greater than 10 have the same red colour intensity. Statistically significant differences from the control plants at each timepoint, as determined by AVOVA (p ≤ 0.05) analysis, are indicated in bold typeface. Figure S3: Heat map presenting fold-change in gene expression data in leaves, induced by drought stress conditions and acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM) application in Malus domestica GG202 and M9 rootstocks after 5, 9, and 14 days without water, in Trial 2. ASM (10 mg a.i./plant) was applied as a root drench, both 14 days before the start of experiment and again on day 0, immediately before dripper removal. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day. There were three replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. Gene expression was quantified by PlexSet® NanoString using CKB4, FYPP3, GPAT1, LTL1, and Protein GRIP as reference genes. All fold changes (numeric values in the figure) are relative to irrigated plants at the same time. Red colouration indicates a fold-increase, blue a fold-decrease, and white is no fold change relative to the control. Statistically significant differences from the control at each timepoint, as determined by ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05) analysis, are indicated in bold typeface. Figure S4: Heat map presenting fold-change in gene expression data in leaves, induced by drought stress conditions and acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM) application in Malus domestica GG202 and M9 rootstocks after 5, 9, and 14 days without water, in Trial 2. ASM (10 mg a.i./plant) was applied as a root drench, both 14 days before the start of experiment and again on day 0, immediately before dripper removal. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day. There were three replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. Gene expression was quantified by PlexSet® NanoString using CKB4, FYPP3, GPAT1, LTL1, and Protein GRIP as reference genes. All fold changes (numeric values in the figure) are relative to irrigated plants at the same time. Red colouration indicates a fold-increase, blue a fold-decrease, and white is no fold change relative to the control. Statistically significant differences from the control at each timepoint, as determined by ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05) analysis, are indicated in bold typeface. Figure S5: Transcript counts (backtransformed log2 gene counts) as measured by PlexSet® NanoString in roots (A-C) and leaves (D-F) in CG202 and M9 Malus domestica rootstocks after 5, 9 and 14 days without water, in Trial 2. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. Acetyl-S-methyl (ASM), at 10 mg a.i./plant, was applied as a root drench, both 14 days before the start of experiment and again on day 0, immediately before dripper removal. There were three replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock used for NanoString. CKB4, FYPP3, GPAT1, LTL1, and Protein GRIP were used as reference genes. The genes presented are A&D) CYP707A1_i; B&E) CYP707A1_ii C&F) CYP707A2_i. Different lettering over bars indicates statistically significant differences, as shown by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD), p ≤ 0.05, for each gene. Figure S6: Transcript counts (backtransformed log2 gene counts) as measured by PlexSet® NanoString in roots (A-D) and leaves (E-H) in CG202 and M9 Malus domestica rootstocks after 5, 9 and 14 days in irrigated and Dry plants, in Trial 2. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. Acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM), at 10 mg a.i./plant, was applied as a root drench, both 14 days before the start of experiment and again on day 0, immediately before dripper removal. There were three replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. CKB4, FYPP3, GPAT1, LTL1, and Protein GRIP were used as reference genes. The genes presented are A&E) PYL4_i; B&F) PYL4_ii C&G) PYL4_iii; D&H) PYL4_iv. Different lettering over bars indicates statistically significant differences, as shown by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD), p ≤ 0.05, for each gene. Figure S7: Transcript counts (backtransformed log2 gene counts) as measured by PlexSet® NanoString in roots (A-C) and leaves (D-F) in CG202 and M9 Malus domestica rootstocks after 0, 2, 5, 9 and 14 days in irrigated and Dry plants, in Trial 1. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. There were five replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. CKB4, FYPP3 and GPAT1 were used as reference genes. The genes presented are A&D) NCED3_i; B&E) NCED3_ii; C&F) NCED3_iii. Different lettering over bars indicates statistically significant differences, as shown by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD), p ≤ 0.05, for each gene. Figure S8: Transcript counts (backtransformed log2 gene counts) as measured by PlexSet® NanoString in roots (A-C) and leaves (D-F) in CG202 and M9 Malus domestica rootstocks after 0, 5, 9 and 14 days in irrigated and Dry plants, in Trial 2. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. Acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM), at 10 mg a.i./plant, was applied as a root drench, both 14 days before the start of experiment and again on day 0, immediately before dripper removal. There were three replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. CKB4, FYPP3, GPAT1, LTL1, and Protein GRIP were used as reference genes. The genes presented are A&D) NCED3_i; B&E) NCED3_ii; C&F) NCED3_iii. Different lettering over bars indicates statistically significant differences, as shown by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD), p ≤ 0.05, for each gene. Figure S9: Transcript counts (backtransformed log2 gene counts) for RD29B_i as measured by PlexSet® NanoString in roots (A&C) and leaves (B&D) in CG202 and M9 Malus domestica rootstocks. Measurements were recorded after 0, 2, 5, 9 and 14 days in irrigated and Dry plants in Trial1 (A&C) and after 5, 9 and 14 days in Trial 2 (B&D). Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. In Trial 2, acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM), at 10 mg a.i./plant, was applied as a root drench, at 14 days before the start of experiment and again on day 0, immediately before dripper removal. There were five replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock in Trial 1 and three in Trial 2. CKB4, FYPP3 and GPAT1 were used as reference genes in Trial 1, and CKB4, FYPP3, GPAT1, LTL1, and Protein GRIP in Trial 2. Different lettering over bars indicates statistically significant differences, as shown by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD), p ≤ 0.05. Figure S10: Clustered Heatmap of phytohormone concentrations common to leaves and roots of two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9) across common sampling timepoints (day 0, 2, 5, 9, 14) in Trial 1. Dry: drought-treated, Control: Irrigated. Data are scaled by row with yellow hues indicating positive and blue hues negative standard (Z-) scores, i.e., relative concentrations. SA: salicylic acid; SAG: salicylic acid glucoside; IAA: indole-3-acetic acid; ABA: abscisic acid; PA: phaseic acid; DPA: dihydrophaseic acid; JA: jasmonic acid; JA-Ile: jasmonic acid-isoleucine; X12.OH.JA: 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid; DHJA: dihydrojasmonic acid; OPC-4: 4-(3-oxo-2-(pent-2-en-1-yl)cyclopentyl)octanoic acid; cis-OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid. Figure S11: Redundancy analysis (RDA) sample plots for A) roots and B) leaves from two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9), with genotype, treatment (Dry vs Irrigated) and sampling day (0, 2, 5, 9, 14 days) as response variables, in Trial 1. The asterisks indicate that explained variance is significant by the respective component at *α=0.05, ** α=0.01, *** α=0.001. Figure S12: Clustered Heatmap of phytohormone concentrations common to leaves and roots of two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9) across common sampling timepoints (day 5, 9, 14) in Trial 2. Dry: drought-treated, Control: Irrigated, ASM: Actiguard-treated. Data are scaled by row with purple hues indicating positive and green hues negative standard (Z-) scores, i.e., relative concentrations. SA: salicylic acid; SAG: salicylic acid glucoside; DHB: dihydroxy benzoic acid; IAA: indole-3-acetic acid; ABA: abscisic acid; PA: phaseic acid; DPA: dihydrophaseic acid; ABA.GE: abscisic acid glucoside; NeoPA: Neophaseic acid; JA: jasmonic acid; JA-Ile: jasmonic acid-isoleucine; X12.OH.JA: 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid; DHJA: dihydrojasmonic acid; OPC-4: 4-(3-oxo-2-(pent-2-en-1-yl)cyclopentyl)octanoic acid; cis-OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid; MeJA: Methyl Jasmonate. Figure S13: Redundancy analysis (RDA) sample plots for A) roots and B) leaves from two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9), with genotype, treatment (dry vs irrigated) and sampling day (5, 9, 14 days) as response variables, in Trial 2. The asterisks indicate that explained variance is significant by the respective component at *α=0.05, ** α=0.01, *** α=0.001. Figure S14: Heat map presenting fold-change data of metabolite concentrations in A) leaves, and B) roots of Malus domestica GG202 and M9 rootstocks after 0, 2, 5, 9, and 14 days without water. All fold changes are relative to irrigated plants at the same time point. Red colouration indicates a fold-increase, blue a fold-decrease, and white is no change relative to the irrigated control. A 2-fold change cutoff was applied for variable selection and bolded data indicate samples with min 2-fold change difference. DHB: dihydroxy benzoic acid; IAA: indole-3-acetic acid; ABA: abscisic acid; PA: phaseic acid; DPA: dihydrophaseic acid; 7-OH-ABA: 7’-hydroxy-abscisic acid; ABA-GE: abscisic acid glucoside; NeoPA: Neo phaseic acid; JA: jasmonic acid; JA-Ile: jasmonic acid-isoleucine; 12-OH-JA: 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid; DHJA: dihydrojasmonic acid; cis-OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid; MeJA: Methyl Jasmonate. Table S1: Identification of reference genes (RGs) and genes of interest (GoI) used for gene expression analysis by PlexSet® NanoString of apple rootstock responses to drought and acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM) application in this study.

Figure 1.

Transpiration rate (A, B), photosynthesis rate (C, D), and stomatal conductance (E, F), in CG202 and M9 Malus domestica rootstocks after 2 (Trial 1 only), 5, 9 and 14 days without water (Dry). Data for Trial 1 given in A, C, E and from Trial 2 in B, D, F. Irrigated control plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. There were five replicate plants per sampling time, treatment and rootstock. Mean ± standard error bars from ANOVA shown.

Figure 1.

Transpiration rate (A, B), photosynthesis rate (C, D), and stomatal conductance (E, F), in CG202 and M9 Malus domestica rootstocks after 2 (Trial 1 only), 5, 9 and 14 days without water (Dry). Data for Trial 1 given in A, C, E and from Trial 2 in B, D, F. Irrigated control plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. There were five replicate plants per sampling time, treatment and rootstock. Mean ± standard error bars from ANOVA shown.

Figure 2.

Heat map presenting fold-change gene expression data in A) root tissue, and B) leaf tissue, induced by drought stress conditions in Malus domestica GG202 and M9 rootstocks after 2, 5, 9, and 14 days without water, in Trial 1. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. There were five replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. Gene expression was quantified by PlexSet® NanoString using CKB4, FYPP3 and GPAT1 as reference genes. Genes of interest are listed in the left-hand column. Numeric values give the fold changes relative to irrigated plants, sampled at the same time periods. Red colouration indicates a fold-increase, blue a fold-decrease, and white is no fold change relative to the control. Colour intensity is indicative of the degree of change, but all fold increases greater than 10 have the same red colour intensity. Statistically significant differences from the control plants at each timepoint, as determined by AVOVA (p ≤ 0.05) analysis, are indicated in bold typeface.

Figure 2.

Heat map presenting fold-change gene expression data in A) root tissue, and B) leaf tissue, induced by drought stress conditions in Malus domestica GG202 and M9 rootstocks after 2, 5, 9, and 14 days without water, in Trial 1. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. There were five replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. Gene expression was quantified by PlexSet® NanoString using CKB4, FYPP3 and GPAT1 as reference genes. Genes of interest are listed in the left-hand column. Numeric values give the fold changes relative to irrigated plants, sampled at the same time periods. Red colouration indicates a fold-increase, blue a fold-decrease, and white is no fold change relative to the control. Colour intensity is indicative of the degree of change, but all fold increases greater than 10 have the same red colour intensity. Statistically significant differences from the control plants at each timepoint, as determined by AVOVA (p ≤ 0.05) analysis, are indicated in bold typeface.

Figure 3.

Heat map presenting fold-change in gene expression data in A) roots, and B) leaves, induced by drought stress conditions and acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM) application in Malus domestica ‘GG202’ and ‘M9’ rootstocks after 5, 9, and 14 days without water, in Trial 2. ASM (10 mg a.i./plant) was applied as a root drench, both 14 days before the start of experiment and again on day 0, immediately before dripper removal. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day. There were three replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. Gene expression was quantified by PlexSet® NanoString using CKB4, FYPP3, GPAT1, LTL1, and Protein GRIP as reference genes. All fold changes (numeric values in the figure) are relative to irrigated plants at the same time. Red colouration indicates a fold-increase, blue a fold-decrease, and white is no fold change relative to the control. Statistically significant differences from the control as each timepoint, as determined by AVOVA (p ≤ 0.05) analysis, are indicated in bold typeface.

Figure 3.

Heat map presenting fold-change in gene expression data in A) roots, and B) leaves, induced by drought stress conditions and acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM) application in Malus domestica ‘GG202’ and ‘M9’ rootstocks after 5, 9, and 14 days without water, in Trial 2. ASM (10 mg a.i./plant) was applied as a root drench, both 14 days before the start of experiment and again on day 0, immediately before dripper removal. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day. There were three replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. Gene expression was quantified by PlexSet® NanoString using CKB4, FYPP3, GPAT1, LTL1, and Protein GRIP as reference genes. All fold changes (numeric values in the figure) are relative to irrigated plants at the same time. Red colouration indicates a fold-increase, blue a fold-decrease, and white is no fold change relative to the control. Statistically significant differences from the control as each timepoint, as determined by AVOVA (p ≤ 0.05) analysis, are indicated in bold typeface.

Figure 4.

Transcript counts (backtransformed log2 gene counts) as measured by PlexSet® NanoString in roots (A-C) and leaves (D-E) in CG202 and M9 Malus domestica rootstocks after 2, 5, 9 and 14 days without water, in Trial 1. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. Measurements taken on day 0 represent the baseline level of gene expression for plants from both treatment groups. There were five replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. CKB4, FYPP3 and GPAT1 were used as reference genes. The genes presented are A&D) CYP707A1_i; B&E) CYP707A1_ii C&F) CYP707A2_i. Different lettering over bars indicates statistically significant differences, as shown by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD), p ≤ 0.05, for each gene.

Figure 4.

Transcript counts (backtransformed log2 gene counts) as measured by PlexSet® NanoString in roots (A-C) and leaves (D-E) in CG202 and M9 Malus domestica rootstocks after 2, 5, 9 and 14 days without water, in Trial 1. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. Measurements taken on day 0 represent the baseline level of gene expression for plants from both treatment groups. There were five replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. CKB4, FYPP3 and GPAT1 were used as reference genes. The genes presented are A&D) CYP707A1_i; B&E) CYP707A1_ii C&F) CYP707A2_i. Different lettering over bars indicates statistically significant differences, as shown by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD), p ≤ 0.05, for each gene.

Figure 5.

Transcript counts (backtransformed log2 gene counts) as measured by PlexSet® NanoString in roots (A-D) and leaves (E-H) in CG202 and M9 Malus domestica rootstocks after 2, 5, 9, and 14 days without water, in Trial 1. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. Measurements taken on day 0 represent the baseline level of gene expression for plants from both treatment groups. There were five replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. CKB4, FYPP3 and GPAT1 were used as reference genes. The genes presented are A&E) PYL4_i; B&F) PYL4_ii; C&G) PYL4_iii; and D&H) PYL4_iv. Different lettering over bars indicates statistically significant differences, as shown by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD), p ≤ 0.05, for each gene.

Figure 5.

Transcript counts (backtransformed log2 gene counts) as measured by PlexSet® NanoString in roots (A-D) and leaves (E-H) in CG202 and M9 Malus domestica rootstocks after 2, 5, 9, and 14 days without water, in Trial 1. Control irrigated plants received a total volume of 1.8 L water/day via drippers. Measurements taken on day 0 represent the baseline level of gene expression for plants from both treatment groups. There were five replicate plants/sample time/treatment/rootstock. CKB4, FYPP3 and GPAT1 were used as reference genes. The genes presented are A&E) PYL4_i; B&F) PYL4_ii; C&G) PYL4_iii; and D&H) PYL4_iv. Different lettering over bars indicates statistically significant differences, as shown by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD), p ≤ 0.05, for each gene.

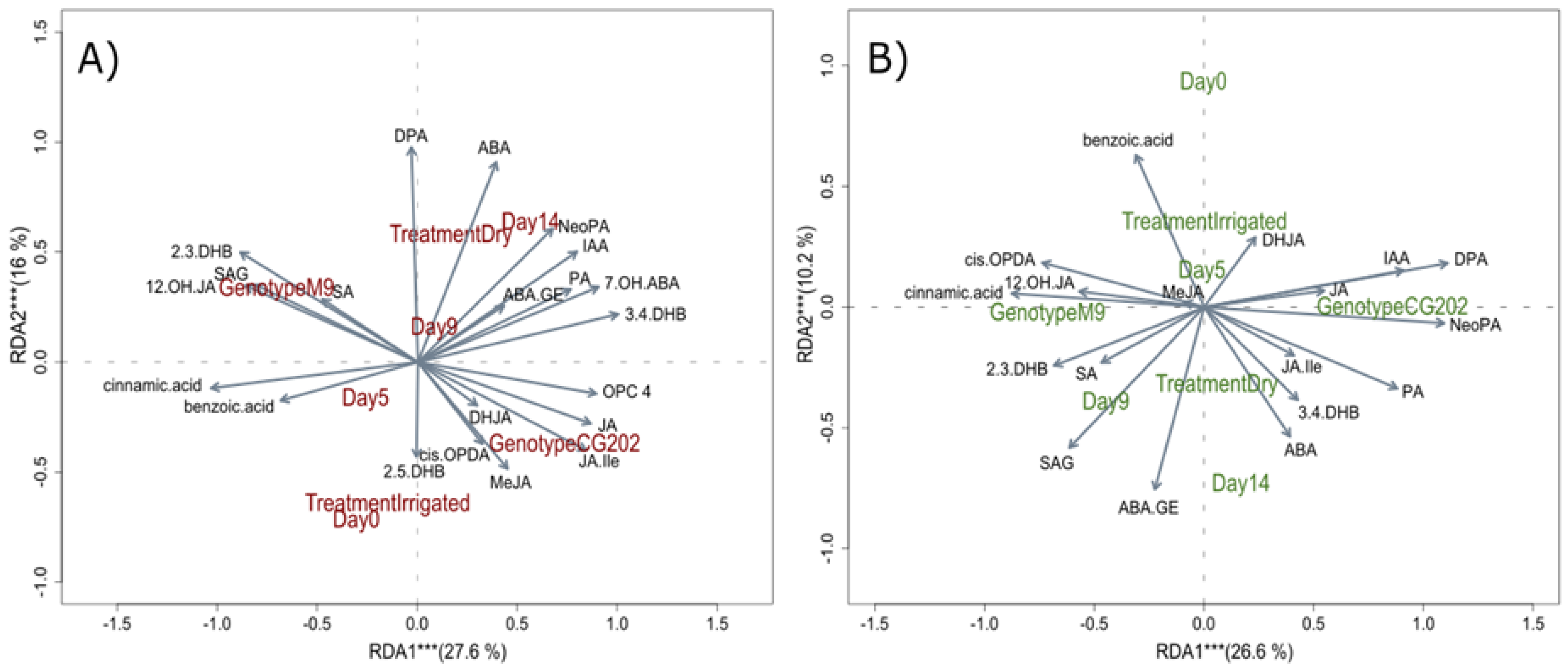

Figure 6.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) biplots for A) roots and B) leaves from two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9) with treatment (Dry vs Irrigated), genotype and sampling day as response variables in Trial 1. The vectors visualise variable loadings and sample distributions by group are highlighted in brown (B) and green (A) writing for roots leaves, respectively. The asterisks indicate that explained variance is significant by the respective component at *α=0.05, ** α=0.01, *** α=0.001. SA: salicylic acid; SAG: salicylic acid glucoside; IAA: indole-3-acetic acid; ABA: abscisic acid; PA: phaseic acid; DPA: dihydrophaseic acid; X7.OH.ABA: 7’-hydroxy-abscisic acid; ABA-GE: abscisic acid glucoside; JA: jasmonic acid; JA-Ile: jasmonic acid-isoleucine; X12OH.JA: 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid; DHJA: dihydrojasmonic acid; OPC.4: 4-(3-oxo-2-(pent-2-en-1-yl)cyclopentyl)octanoic acid; cis.OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid.

Figure 6.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) biplots for A) roots and B) leaves from two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9) with treatment (Dry vs Irrigated), genotype and sampling day as response variables in Trial 1. The vectors visualise variable loadings and sample distributions by group are highlighted in brown (B) and green (A) writing for roots leaves, respectively. The asterisks indicate that explained variance is significant by the respective component at *α=0.05, ** α=0.01, *** α=0.001. SA: salicylic acid; SAG: salicylic acid glucoside; IAA: indole-3-acetic acid; ABA: abscisic acid; PA: phaseic acid; DPA: dihydrophaseic acid; X7.OH.ABA: 7’-hydroxy-abscisic acid; ABA-GE: abscisic acid glucoside; JA: jasmonic acid; JA-Ile: jasmonic acid-isoleucine; X12OH.JA: 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid; DHJA: dihydrojasmonic acid; OPC.4: 4-(3-oxo-2-(pent-2-en-1-yl)cyclopentyl)octanoic acid; cis.OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid.

Figure 7.

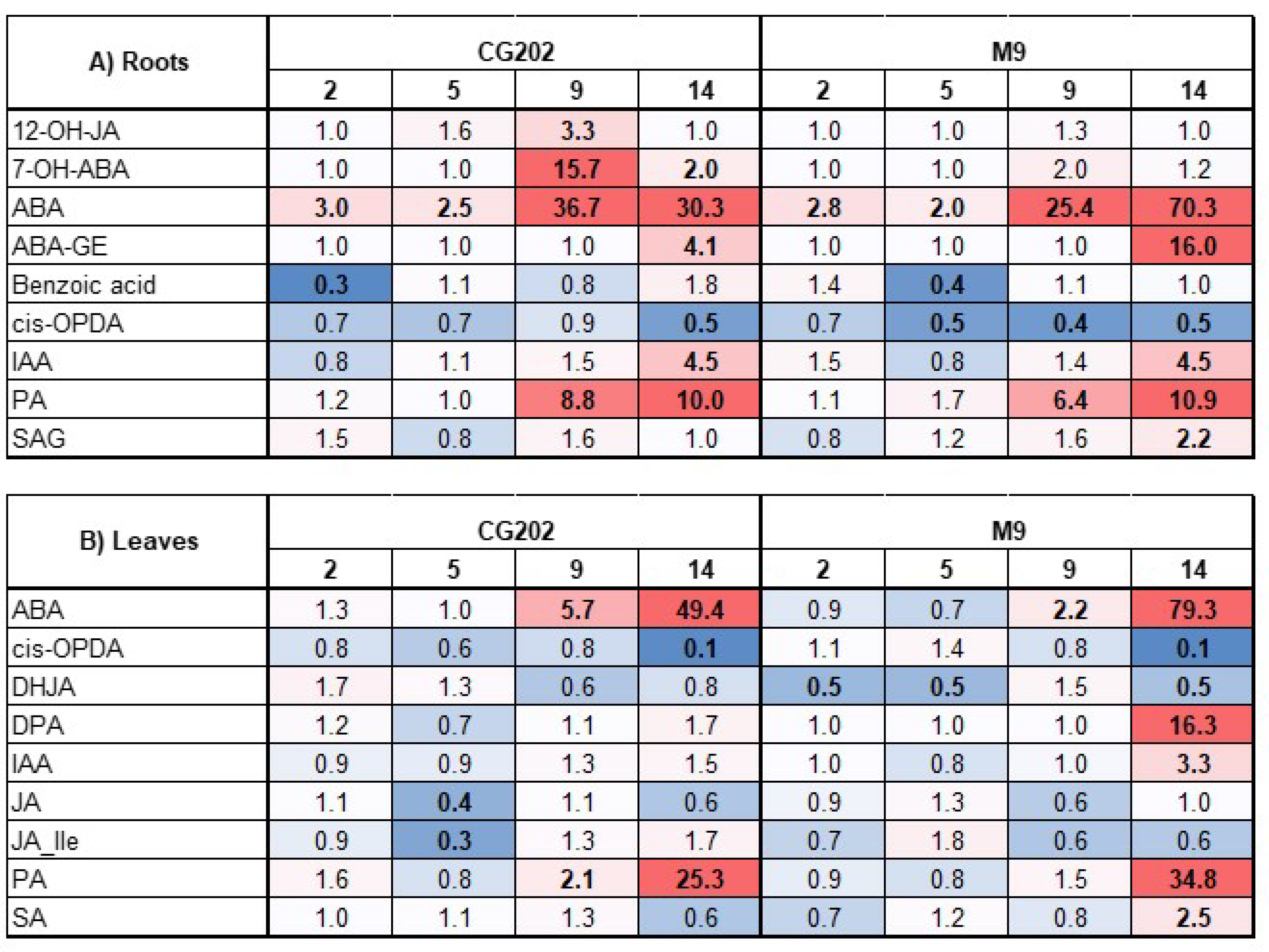

Heat map presenting fold-change data of metabolite concentrations in A) roots and B) leaves, of Malus domestica GG202 and M9 rootstocks after 0, 2, 5, 9, and 14 days without water in Trial 1. All fold changes are relative to irrigated plants at the same time point. Red colouration indicates a fold-increase, blue a fold-decrease, and white is no change relative to the irrigated control. Colour intensity is indicative of the degree of change, but all fold increases greater than 10 have the same red colour intensity. A 2-fold change cutoff was applied for variable selection and bolded data indicate samples with min 2-fold change difference. SA: salicylic acid; SAG: salicylic acid glucoside; IAA: indole-3-acetic acid; ABA: abscisic acid; PA: phaseic acid; DPA: dihydrophaseic acid; 7-OH-ABA: 7’-hydroxy-abscisic acid; ABA-GE: abscisic acid glucoside; JA: jasmonic acid; JA-Ile: jasmonic acid-isoleucine; 12-OH-JA: 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid; DHJA: dihydrojasmonic acid; cis.OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid.

Figure 7.

Heat map presenting fold-change data of metabolite concentrations in A) roots and B) leaves, of Malus domestica GG202 and M9 rootstocks after 0, 2, 5, 9, and 14 days without water in Trial 1. All fold changes are relative to irrigated plants at the same time point. Red colouration indicates a fold-increase, blue a fold-decrease, and white is no change relative to the irrigated control. Colour intensity is indicative of the degree of change, but all fold increases greater than 10 have the same red colour intensity. A 2-fold change cutoff was applied for variable selection and bolded data indicate samples with min 2-fold change difference. SA: salicylic acid; SAG: salicylic acid glucoside; IAA: indole-3-acetic acid; ABA: abscisic acid; PA: phaseic acid; DPA: dihydrophaseic acid; 7-OH-ABA: 7’-hydroxy-abscisic acid; ABA-GE: abscisic acid glucoside; JA: jasmonic acid; JA-Ile: jasmonic acid-isoleucine; 12-OH-JA: 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid; DHJA: dihydrojasmonic acid; cis.OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid.

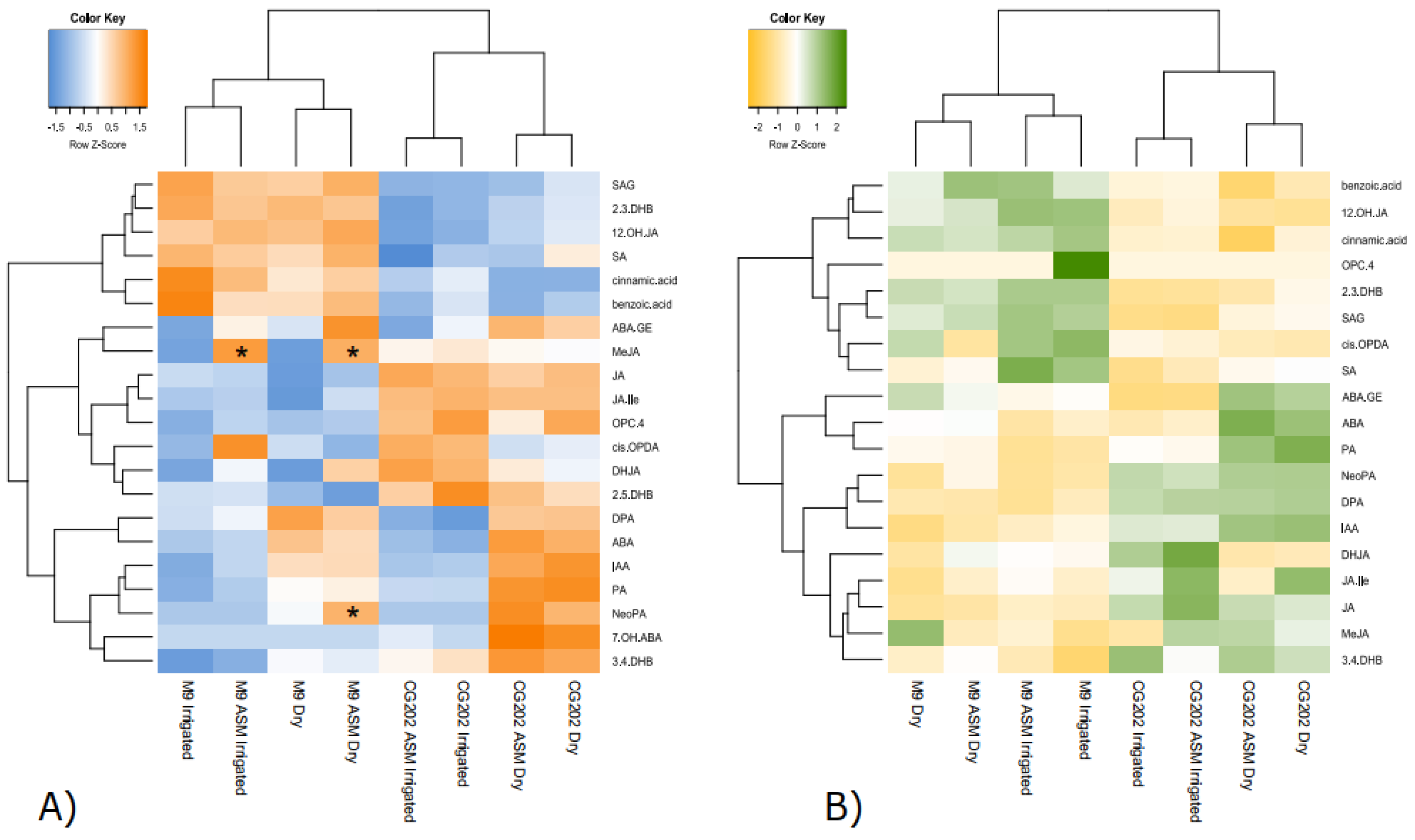

Figure 8.

Clustered Heatmap of phytohormone concentrations from two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9) across common sampling timepoints (day 5, 9, 14) in Trial 2. A) roots, B) leaves. Dry: drought-treated, Irrigated: Control, ASM: Actigard-treated. Data are scaled by row with orange (A) and green (B) hues indicating positive and blue (A) and yellow (B) hues negative standard (Z-) scores, i.e relative concentrations. Asterisks indicate statistical difference of ASM-treatment by sample based on pairwise comparison with α=0.05. SA: salicylic acid; SAG: salicylic acid glucoside; DHB: dihydroxy benzoic acid; IAA: indole-3-acetic acid; ABA: abscisic acid; PA: phaseic acid; DPA: dihydrophaseic acid; 7-OHABA: 7’-hydroxy-abscisic acid; ABA-GE: abscisic acid glucoside; NeoPA: neo phaseic acid; JA: jasmonic acid; JA-Ile: jasmonic acid-isoleucine; 12-OH-JA: 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid; DHJA: dihydrojasmonic acid; OPC-4: 4-(3-oxo-2-(pent-2-en-1-yl)cyclopentyl)octanoic acid; cis-OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid; MeJA: methyl jasmonate.

Figure 8.

Clustered Heatmap of phytohormone concentrations from two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9) across common sampling timepoints (day 5, 9, 14) in Trial 2. A) roots, B) leaves. Dry: drought-treated, Irrigated: Control, ASM: Actigard-treated. Data are scaled by row with orange (A) and green (B) hues indicating positive and blue (A) and yellow (B) hues negative standard (Z-) scores, i.e relative concentrations. Asterisks indicate statistical difference of ASM-treatment by sample based on pairwise comparison with α=0.05. SA: salicylic acid; SAG: salicylic acid glucoside; DHB: dihydroxy benzoic acid; IAA: indole-3-acetic acid; ABA: abscisic acid; PA: phaseic acid; DPA: dihydrophaseic acid; 7-OHABA: 7’-hydroxy-abscisic acid; ABA-GE: abscisic acid glucoside; NeoPA: neo phaseic acid; JA: jasmonic acid; JA-Ile: jasmonic acid-isoleucine; 12-OH-JA: 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid; DHJA: dihydrojasmonic acid; OPC-4: 4-(3-oxo-2-(pent-2-en-1-yl)cyclopentyl)octanoic acid; cis-OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid; MeJA: methyl jasmonate.

Figure 9.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) biplots for A) leaves and B) roots from two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9) with treatment (Dry vs Irrigated), genotype and sampling day as response variables in Trial 2. The vectors visualise variable loadings and sample distributions by group are highlighted in green (A) and brown (B) text for leaves and roots, respectively. The asterisks indicate that explained variance is significant by the respective component at *α=0.05, ** α=0.01, *** α=0.001. SA: salicylic acid; SAG: salicylic acid glucoside; DHB: dihydroxy benzoic acid; IAA: indole-3-acetic acid; ABA: abscisic acid; PA: phaseic acid; DPA: dihydrophaseic acid; 7-OHABA: 7’-hydroxy-abscisic acid; ABA-GE: abscisic acid glucoside; NeoPA: neo phaseic acid; JA: jasmonic acid; JA-Ile: jasmonic acid-isoleucine; 12-OH-JA: 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid; DHJA: dihydrojasmonic acid; OPC-4: 4-(3-oxo-2-(pent-2-en-1-yl)cyclopentyl)octanoic acid; cis-OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid; MeJA: methyl jasmonate.

Figure 9.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) biplots for A) leaves and B) roots from two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9) with treatment (Dry vs Irrigated), genotype and sampling day as response variables in Trial 2. The vectors visualise variable loadings and sample distributions by group are highlighted in green (A) and brown (B) text for leaves and roots, respectively. The asterisks indicate that explained variance is significant by the respective component at *α=0.05, ** α=0.01, *** α=0.001. SA: salicylic acid; SAG: salicylic acid glucoside; DHB: dihydroxy benzoic acid; IAA: indole-3-acetic acid; ABA: abscisic acid; PA: phaseic acid; DPA: dihydrophaseic acid; 7-OHABA: 7’-hydroxy-abscisic acid; ABA-GE: abscisic acid glucoside; NeoPA: neo phaseic acid; JA: jasmonic acid; JA-Ile: jasmonic acid-isoleucine; 12-OH-JA: 12-hydroxyjasmonic acid; DHJA: dihydrojasmonic acid; OPC-4: 4-(3-oxo-2-(pent-2-en-1-yl)cyclopentyl)octanoic acid; cis-OPDA: 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid; MeJA: methyl jasmonate.

Figure 10.

Line graphs showing the mean concentrations of drought-responsive phytohormone metabolites from A) Roots and B) Leaves of two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9) in Trial 2. Days indicate the time since watering for drought treated (Dry) plants, while control (Irrigated) plants were watered during the entire time course. Concentrations are given per tissue fresh weight and represent the mean of four biological replicates. 95% Confidence intervals are visualised by shading.

Figure 10.

Line graphs showing the mean concentrations of drought-responsive phytohormone metabolites from A) Roots and B) Leaves of two apple rootstock genotypes (CG202, M9) in Trial 2. Days indicate the time since watering for drought treated (Dry) plants, while control (Irrigated) plants were watered during the entire time course. Concentrations are given per tissue fresh weight and represent the mean of four biological replicates. 95% Confidence intervals are visualised by shading.

Table 1.

Change in pot weight (%) of droughted (Dry) plants over time relative to watered (Irrigated) plants at time 0 in two apple rootstocks, CG202 and M9, in Trial 1.

Table 1.

Change in pot weight (%) of droughted (Dry) plants over time relative to watered (Irrigated) plants at time 0 in two apple rootstocks, CG202 and M9, in Trial 1.

| Rootstock |

± Water |

% weight relative to controls at T01 |

| 0d |

2d |

5d |

9d |

14d |

| CG202 |

Irrigated |

- |

103 ±0.7 |

103 ±0.6 |

103 ±0.5 |

103 ±0.8 |

| Dry |

100 ±2.9 |

89 ± 2.5 |

79 ± 2.2 |

60 ±1.9 |

52 ±1.7 |

| M9 |

Irrigated |

- |

100 ±1.3 |

100 ±1.3 |

99 ±1.0 |

103 ±1.7 |

| Dry |

100 ±1.3 |

91 ±1.4 |

82 ±1.5 |

65 ±1.8 |

54 ±1.1 |

Table 2.

Change in pot weight (%) of droughted (Dry) plants over time relative to watered (Irrigated) plants at time 0 in two apple rootstocks Trial 2.

Table 2.

Change in pot weight (%) of droughted (Dry) plants over time relative to watered (Irrigated) plants at time 0 in two apple rootstocks Trial 2.

| Rootstock |

±Water |

±ASM |

% weight relative to controls at T01 |

| 5d |

9d |

14d |

| CG202 |

Irrigated |

No ASM |

99 ±1.4 |

101 ±1.8 |

100 ±1.1 |

| ASM |

100 ±1.7 |

101 ±1.4 |

100 ±0.8 |

| Dry |

No ASM |

77 ±2.4 |

63 ±1.6 |

56 ±1.7 |

| ASM |

78 ±1.7 |

64 ±2.3 |

55 ±1.2 |

| M9 |

Irrigated |

No ASM |

100 ±1.2 |

98 ±1.5 |

99 ±1.4 |

| ASM |

100 ±1.6 |

98 ±2.0 |

99 ±1.7 |

| Dry |

No ASM |

79 ±2.0 |

68 ±1.6 |

59 ±3.4 |

| ASM |

82 ±1.7 |

69 ±0.4 |

61 ±0.9 |