Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Relevance of the Research Topic

3. Review of the Current State of the Art in the Subject Area of the Article

4. Functional Capabilities of Electronic Component Selection Systems

- Search for components by name and parameters. The basic option is to search for the component of interest by its name, article number, or keywords. A more advanced option is parametric search, when the user sets filters by technical characteristics (for example, voltage range, case type, frequency, power, etc.) and the system displays all components that meet the specified criteria [1]. Parametric search allows you to narrow down tens of thousands of options to a few suitable ones without knowing the specific article number of the part. Most platforms provide catalogs with a hierarchy of component categories and a set of attributes for filtering.

- Access to technical information. Systems contain extensive information about components: basic technical characteristics, descriptions, images, connection diagrams, etc. Links to passport data (datasheet) in PDF format are often integrated. Some platforms (for example, large distributors) publish technical documentation and reference books on their websites, as well as articles or notes on the use of components [1]. The presence of reliable and up-to-date technical information directly in the system saves the engineer’s time and reduces the risk of errors.

- Comparison and selection of analogs. An important function is the selection of similar components. If the required component is unavailable or expensive, the system can offer a list of analogs - components with similar parameters, compatible in basic characteristics. Some platforms support cross - reference between components from different manufacturers [1]. For example, domestic search sites eFind.ru, ChipFind.ru and Optochip.org implement the selection of analogs of imported and domestic microcircuits interchangeably [1]. The selection of analogs can be carried out according to interchangeability tables previously entered into the database or by comparing parameters (including tolerances). Modern intelligent systems can use recommender system methods to find the closest analog, even if the parameters do not match exactly.

- Analysis of suppliers, prices and availability of electronic components. For each component, information about suppliers is usually provided: which distributors or manufacturers have this component in stock and at what price. Large aggregators collect data on the warehouses of hundreds of suppliers and allow you to quickly assess the availability of a component on the market [67,68]. For example, the Octopart system is directly linked to supplier data and shows current balances, prices and life cycle statuses for more than 61 million components [69]. This makes it possible to immediately take into account economic and logistical factors when choosing a component - prices, minimum lots, delivery times. Some systems offer price analysis tools (price trend charts, price comparisons from different sellers) and even price change forecasts.

- Comparison of components by parameters. A useful feature is the side-by-side comparison of several selected components. The system displays a table of parameters for two or more components, highlighting the differences. This makes it easier to select the best option from a group of functionally similar parts. For example, the Wizerr smart platform allows you to instantly compare the pins, packages, dimensions, and electrical parameters of several components [70]. Such a comparison table saves time when analyzing trade-offs (e.g., current consumption and cost).

- Intelligent search and filtering methods. Advanced systems implement elements of artificial intelligence for smarter searching. This may include auto-completion and input correction (understanding the engineer’s intentions in case of an imprecise request), searching by synonyms and related terms, rating sorting of results by relevance or popularity in the industry. Solutions are emerging that allow for dialog search: for example, upload a text description of requirements or a fragment of a diagram and receive component recommendations. Some recent developments make it possible to search in natural language or even using images (visual search), although this is less common at the moment [71]. Another direction is the integration of chatbots for interaction with a knowledge base about components. For example, the Wizerr platform claims a function for interactive communication with datasheets: an engineer can ask a question to an AI model, which, having “read” thousands of technical documentation, will give an answer based on the specific characteristics of the component of interest [70].

- Group search and list management. In the case of large projects, the function of one-time verification of the list of components (for example, loading the bill of materials – BOM) is useful. A number of systems can perform group search – processing several positions at once: this allows, for example, to load a list of required denominations and get a summary for each (found/not found, availability, analogs, etc.). According to the analysis, only a few platforms have group search [1], for example, Optochip.org [72], FindChips.com [73] and Farnell.com [74]. Large platforms also offer personal accounts for project and BOM management: storing lists of selected components, exporting to CAD or ERP, notification of status changes (for example, obsolescence), etc.

- Additional services and integrations. Many systems complement the search with a whole range of related services: calculators, links to the application, communities. For example, some foreign platforms (Digi-Key, Farnell, etc.) contain sections with thematic literature, reference books, and forums for engineers [1]. This allows users to share experiences, receive recommendations, and receive support. Commercial platforms often offer APIs for integration (more on this below) and even mobile applications for access to search on the go [1]. Finally, specialized corporate systems can integrate with CAD systems, product data management systems (PDM/PLM), and purchasing modules, providing an end-to-end process - from selection at the design stage to ordering and supporting the component in production.

5. Review of Existing Systems and Solutions

5.1. Search Engines and Aggregators of Electronic Components

5.2. Specialized Information Systems (MDM) and Component Databases

5.3. Integration with CAD and Corporate Development Systems

5.4. Comparative Analysis of Existing Systems

5.5. The Most Significant Scientific Publications on Developments for the Period 2015 – 2025

5.6. Problems and Difficulties According to Literature and Practice

6. Ways to Overcome Difficulties and Development Prospects

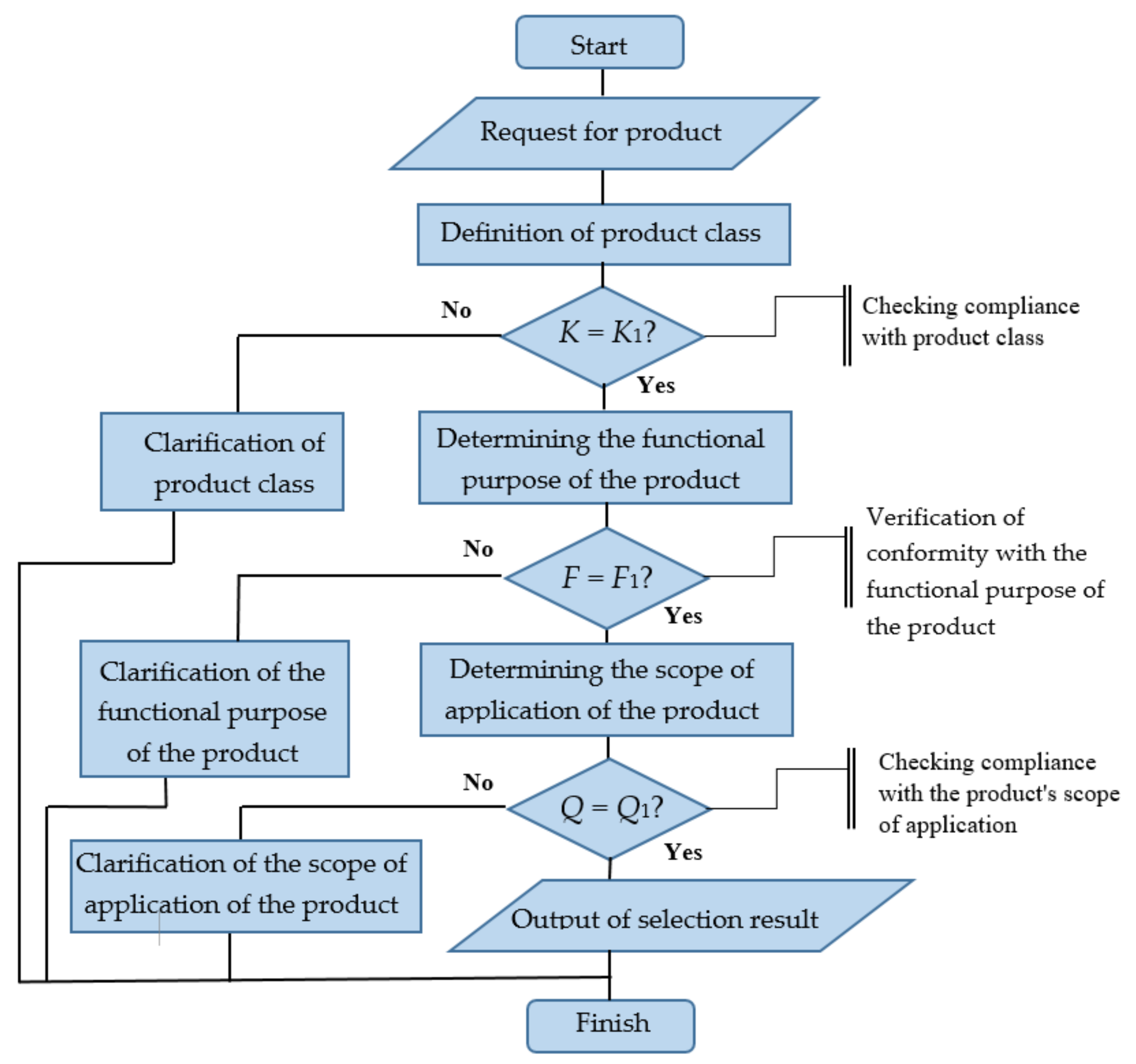

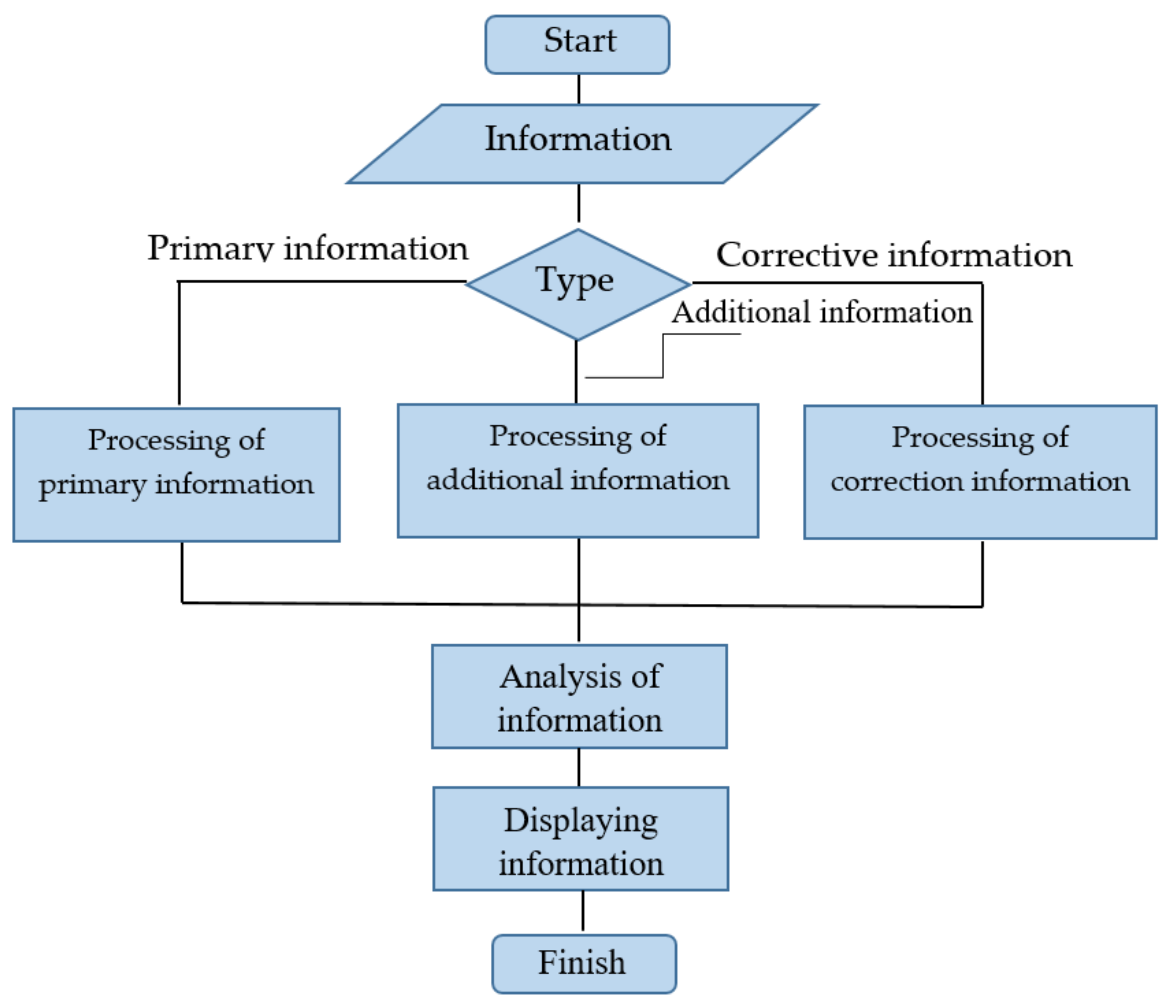

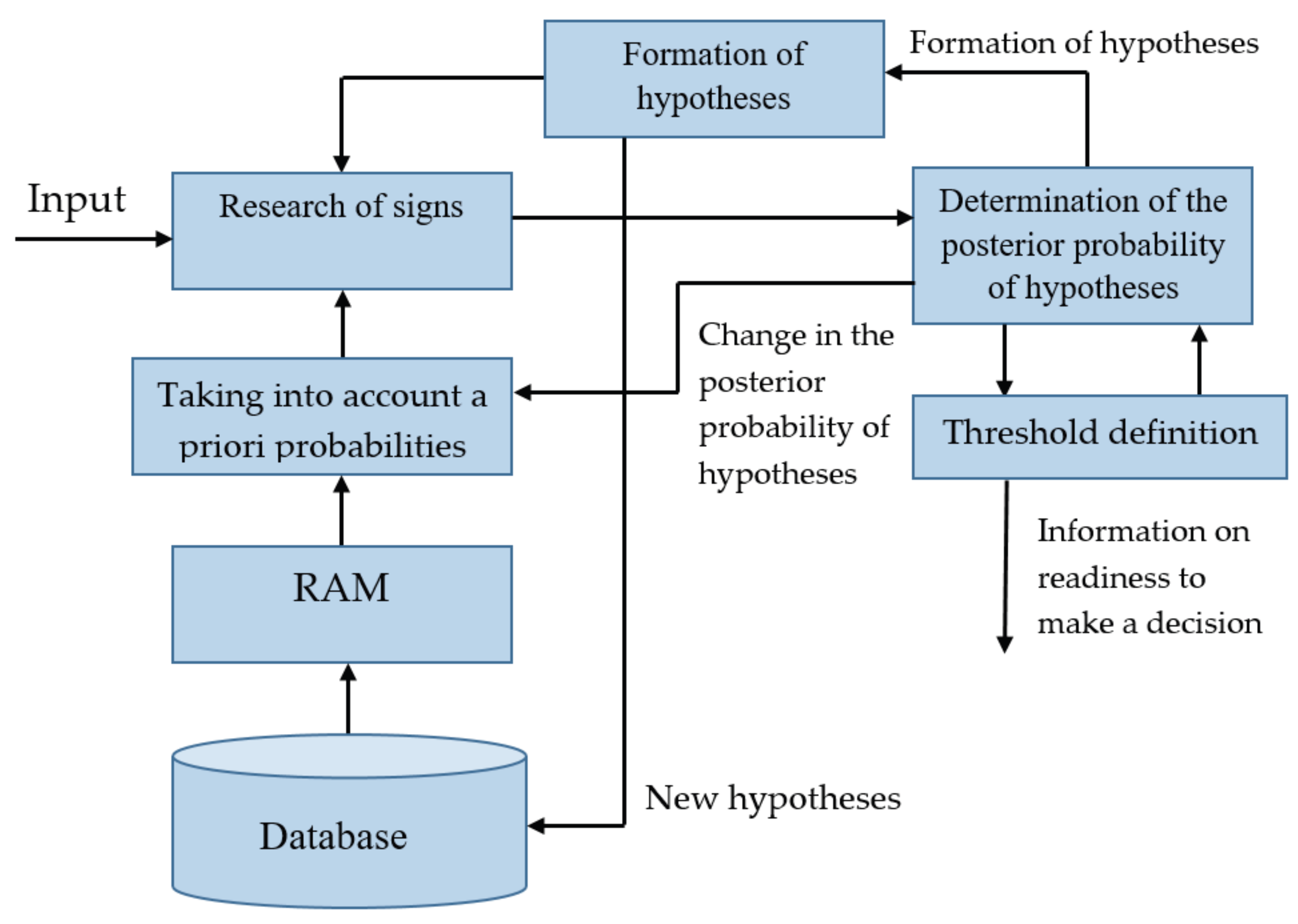

7. Proposed Steps for the Development of the System

7.1. Masking Unnecessary Information

7.2. Creating Lists of Favorites and Underdogs

7.3. Creating a List of Typical Reliable Solutions

7.4. Proposals for the Creation of the System

- -

- access to the database;

- -

- extracting data from various arrays;

- -

- modeling the rules for processing and analyzing information;

- -

- modeling forms of presentation of analysis results;

- -

- artificial intelligence at the level of expert subsystems.

- -

- powerful multiprocessor computing machines in the form of special OLAP servers;

- -

- special methods of multivariate analysis;

- -

- special data warehouses (DWh).

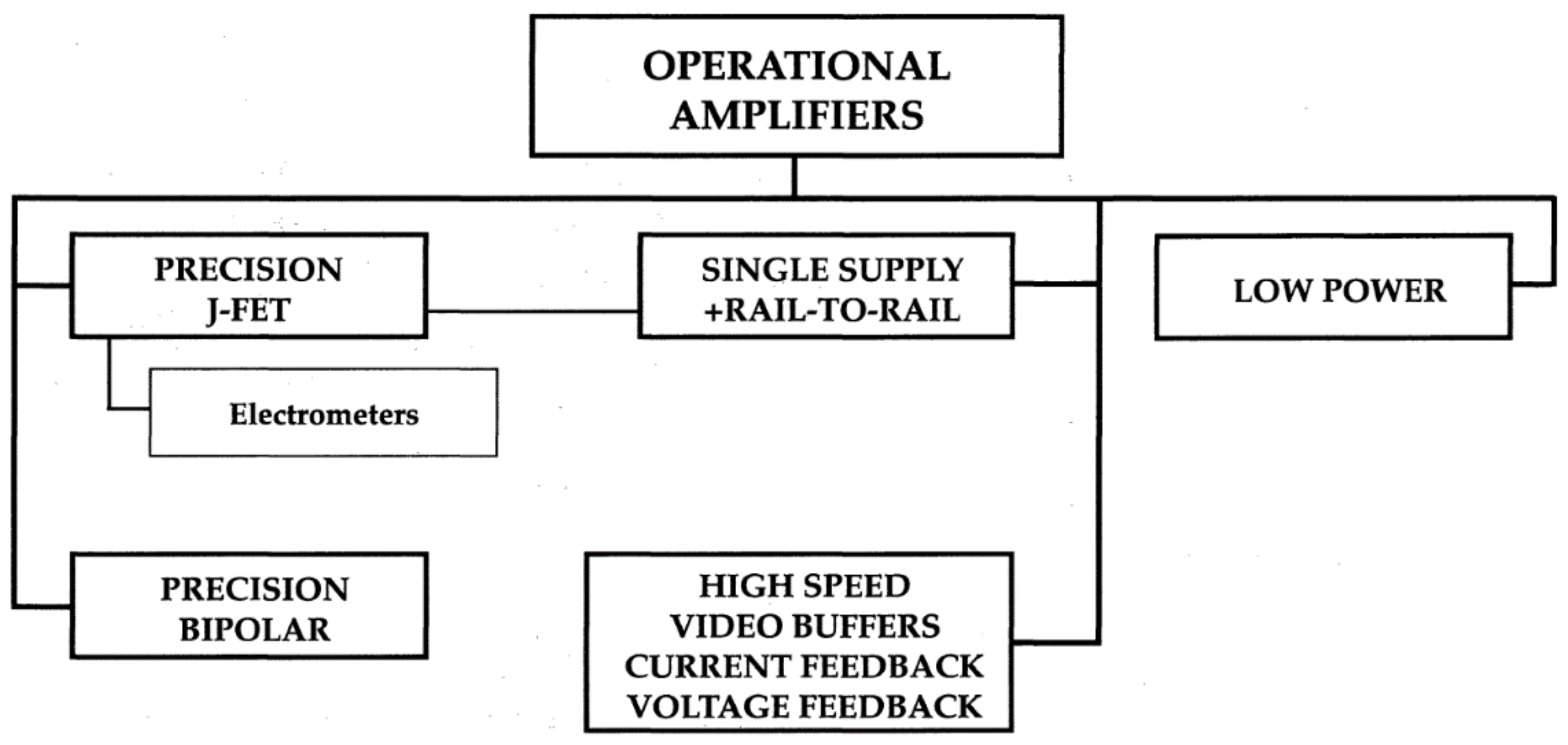

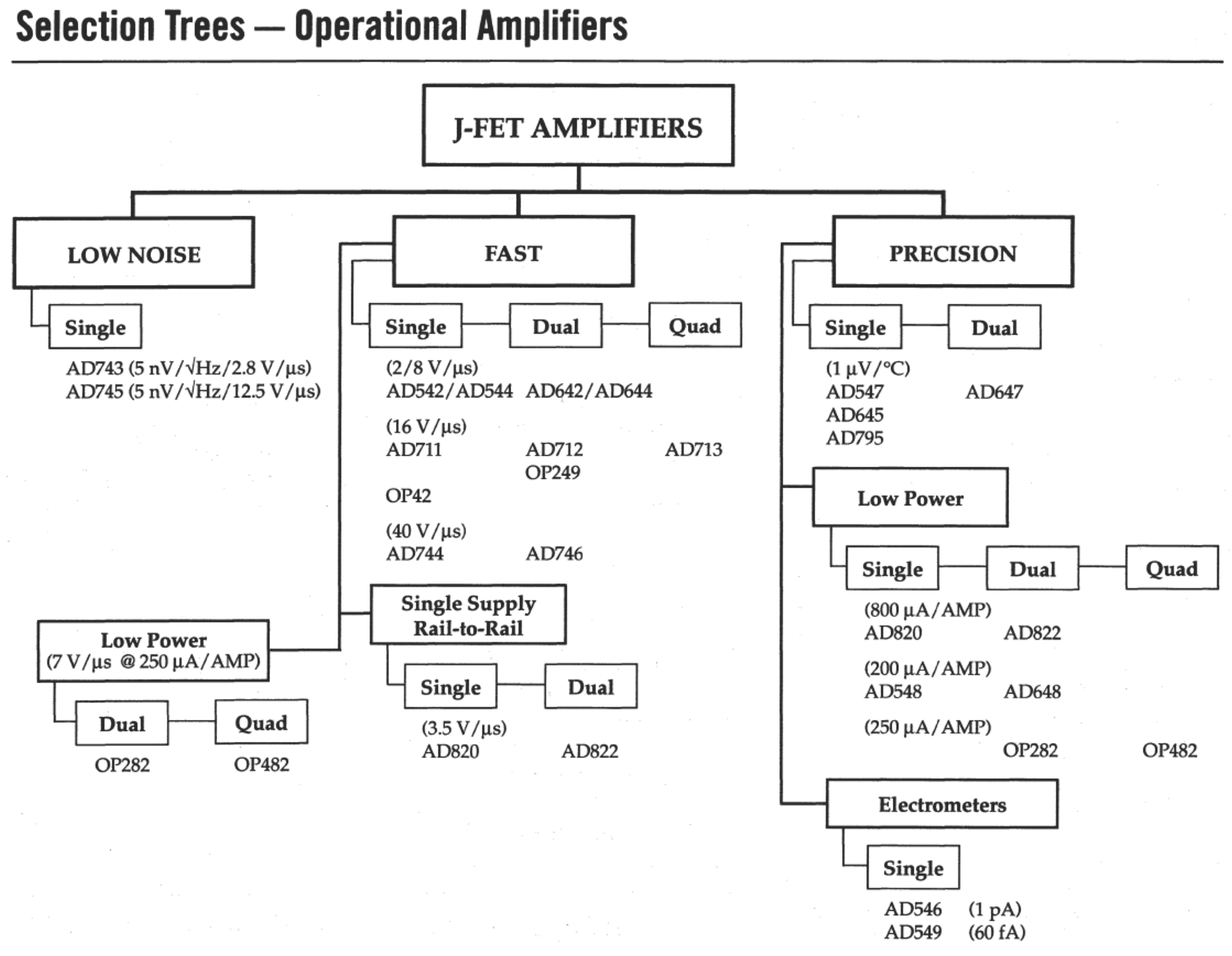

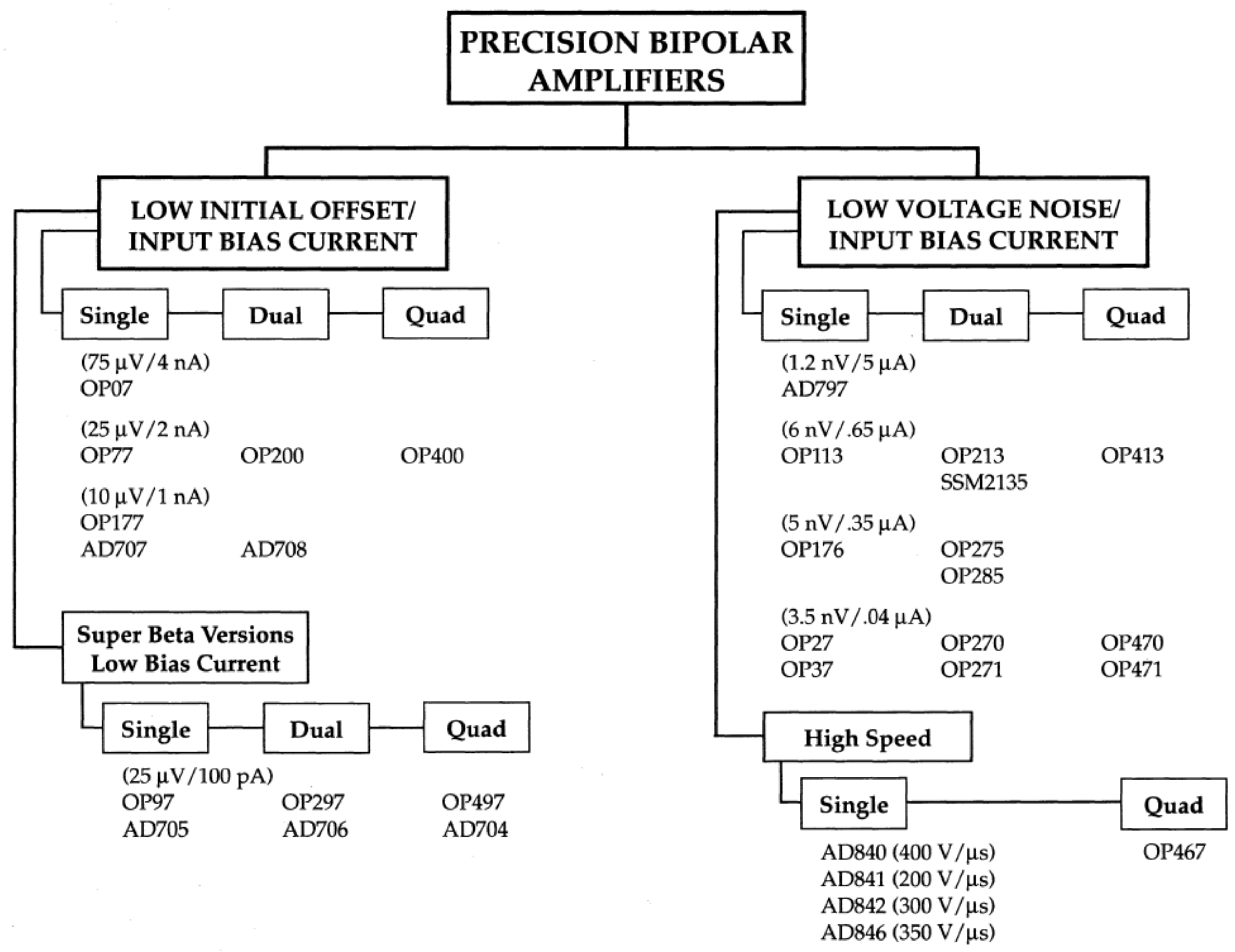

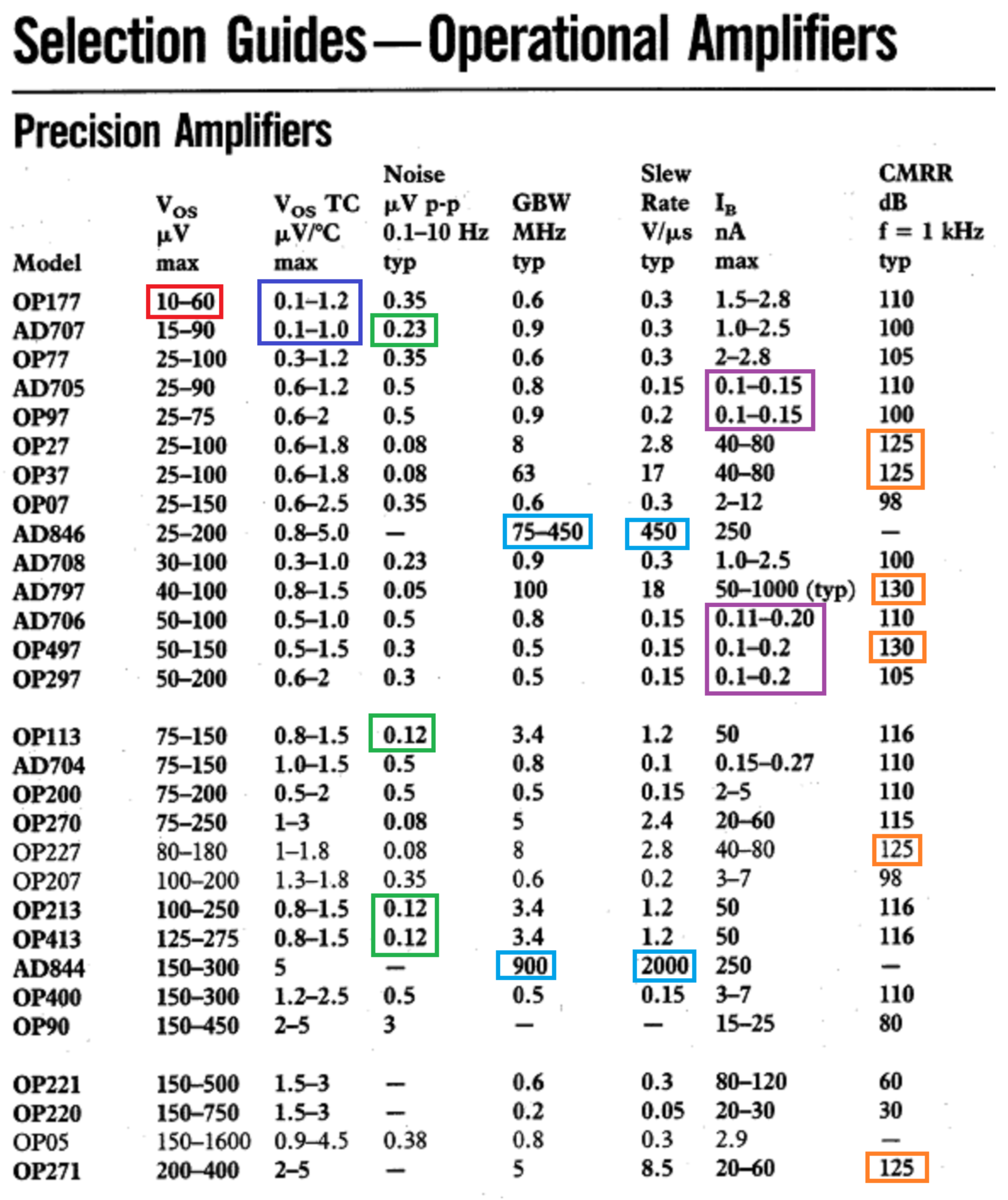

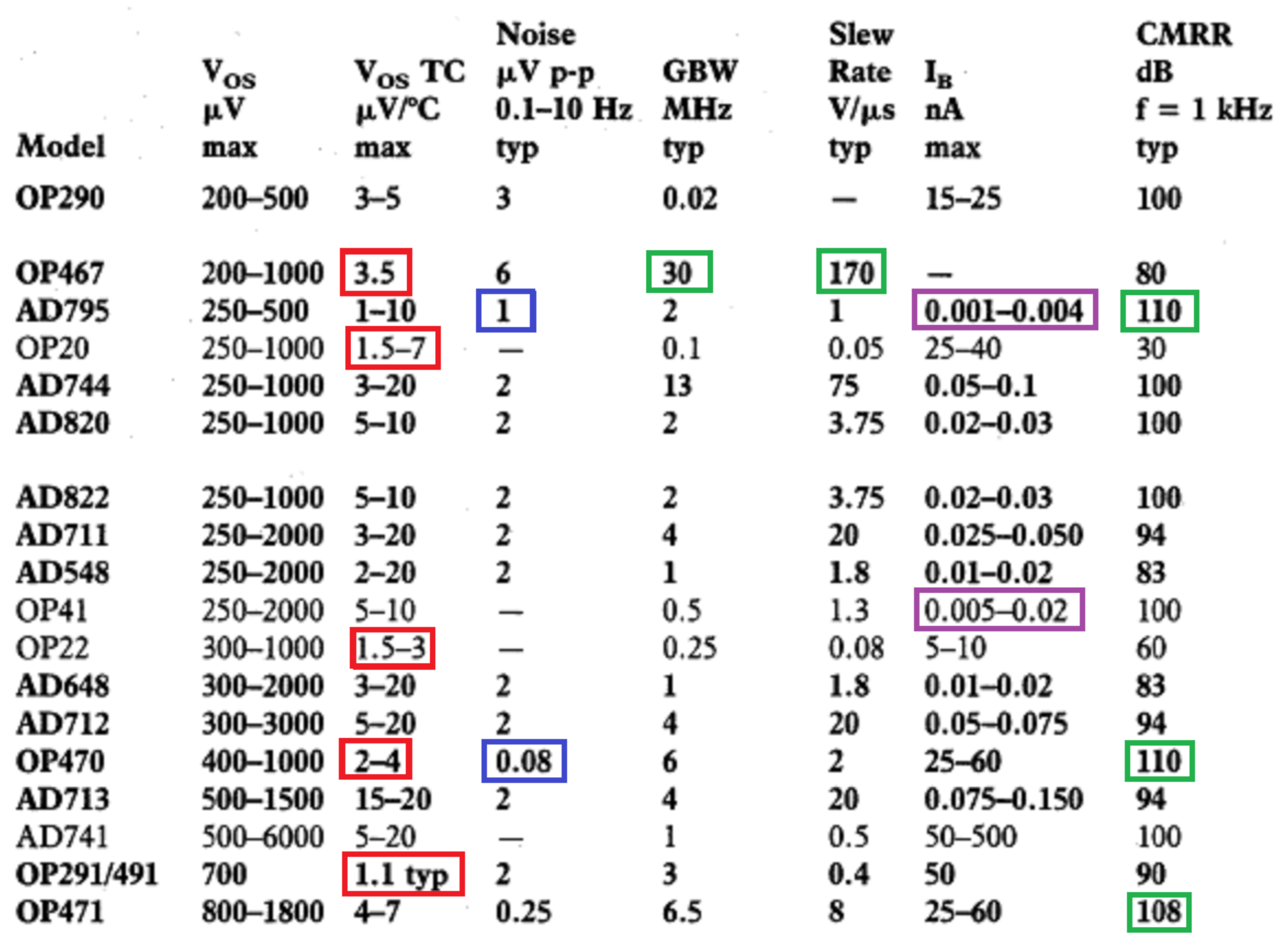

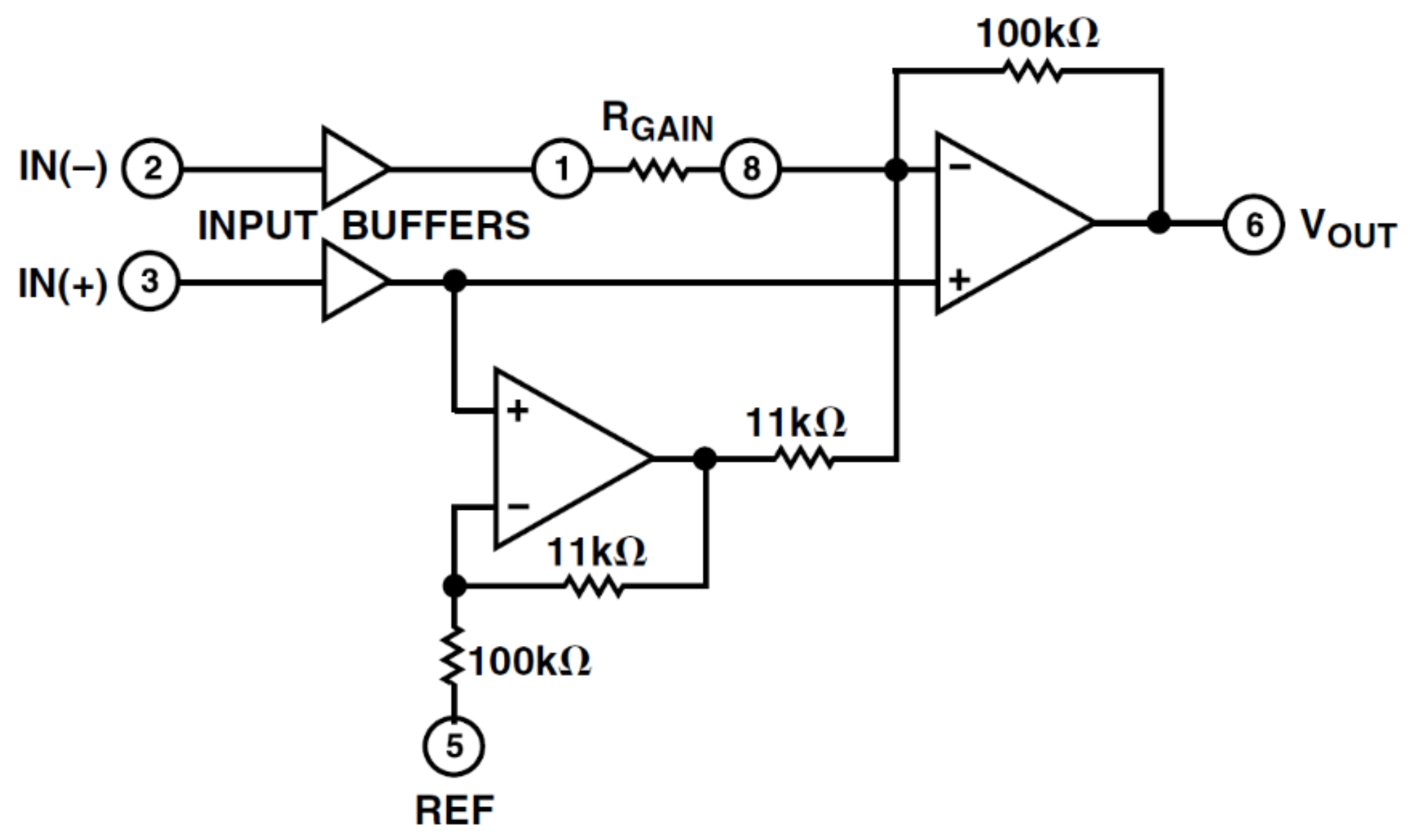

7.5. Example of Choosing an Operational Amplifier

- I.

- Precision J-FET Amplifiers.

- I.

- II. Single Supply Amplifiers.

- I.

- III. Precision Bipolar Amplifiers.

- I.

- IV. High Speed Video Buffers.

- I.

- V. Current Voltage Feedback Amplifiers.

- I.

- VI. Low Power Amplifiers.

- ◊

- Single; Dual; Quad;

- ◊

- Precision;

- ◊

- Bipolar;

- ◊

- Low Power; Very Low Power;

- ◊

- Low Noise;

- ◊

- Fast;

- ◊

- Electrometer;

- ◊

- Rail - to - Rail;

- ◊

- High Speed;

- ◊

- Voltage Feedback;

- ◊

- Current Feedback;

- ◊

- Low Initial Offset;

- ◊

- Input Bias Current;

- ◊

- Super Beta Versions;

- ◊

- Low Voltage Noise;

- ◊

- Input Bias Current;

- ◊

- First Generation;

- ◊

- Second Generation;

- ◊

- Special Function;

- ◊

- Clamp Amplifiers;

- ◊

- Buffer.

7.6. Рarsing Algorithms and Methods

8. Discussion and Conclusions

9. Conclusions

10. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| CAD | Computer aided design |

| DSAM | Decision Science Applications and Models |

| REA | Radio-electronic equipment |

| SW | Software |

| ECB | Element component base |

| BOM | Bill of materials |

| ERP | Enterprise resource planning (systems) |

| PDM | Product data management |

| PLM | Product life-cycle management |

| EDA(D) | Electronic computer-aided design |

| NDND | Not recommended for new design |

| EOL | End of Life (after some data) |

| API | Application programming interface |

| UIAS | Unified identification and authentication system |

| IHS | IHS Markit – name of company |

| AVL | Balanced binary search tree (named after inventors Adelson-Velsky and Landis) |

| PCN | Personal communications network: a system for connecting mobile phones: |

| XML | eXtensible Markup Language |

| CIS | Component Information System |

| CIP | Component Information Portal |

References

- Dmitry Ireshev. Rating of platforms for searching electronic components. 2018. https://habr.com/ru/articles/410031/ (In Russian).

- Best Journals - Electronics and Electrical Engineering. Electronics (MDPI). https://research.com/journal/electronics-mdpi.

- Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P.; Heinrich, K. Machine learning and deep learning. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Sharma, R.; Jindal, N. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Applications-A Vision. Glob. Transit. Proc. 2021, 2, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, IH Deep Learning: A Comprehensive Overview on Techniques, Taxonomy, Applications and Research Directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 420. [CrossRef]

- Shalev-Shwartz, S.; Ben-David, S. Understanding Machine Learning: From Theory to Algorithms; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; p. 410. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; p. 800. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Sajjad, M.; Hussain, T.; Ullah, A. ; Imran, AS A Review on Traditional Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models for WBCs Classification in Blood Smear Images. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 10657–10673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y. A Comparison of Traditional Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Image Recognition. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1314, 012148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.A.; Chen, Z. ; Crandall, DJ Deep Neural Network–Based Detection and Verification of Microelectronic Images. J.Hardw. Syst. Secur. 2020, 4, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goobar, L. Machine Learning Based Image Classification of Electronic Components; KTH: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, G.; Luo, J.; He, J. An Electronic Component Recognition Algorithm Based on Deep Learning with a Faster SqueezeNet. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 2940286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Gu, J.; Sun, X.; Hou, Y.; Uddin, S. A Rapid Recognition Method for Electronic Components Based on the Improved YOLO-V3 Network. Electronics 2019, 8, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeva, P.; Bressan, M.; Tovar, A.; Vitria, J. Bayesian Classification for Inspection of Industrial Products. In Catalonian Conference on Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 399–407. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, S.; Wan, F.; Lei, G.; Xu, L.; Ye, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhou, W.; Xu, C. EC-YOLO: Improved YOLOv7 Model for PCB Electronic Component Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starodubov, D.; Danishvar, S. ; Abu Ebayyeh, AARM; Mousavi, A. Advancements in PCB Components Recognition Using WaferCaps: A Data Fusion and Deep Learning Approach. Electronics 2024, 13, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atik, I. Classification of Electronic Components Based on Convolutional Neural Network Architecture. Energies 2022, 15, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hożyń, S. Convolutional Neural Networks for Classifying Electronic Components in Industrial Applications. Energies. 2023, 16, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Gu, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, W.; Li, J. Research on Multi-Scene Electronic Component Detection Algorithm with Anchor Assignment Based on K-Means. Electronics 2022, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, J.; Wu, J. A Novel Electronic Component Classification Algorithm Based on Hierarchical Convolution Neural Network. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Changchun, China, 21–23 August 2020; Volume 474, p. 052081. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Xu, J.; Wu, J. A Novel Electronic Component Classification Algorithm Based on Hierarchical Convolution Neural Network. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Changchun, China, 21–23 August 2020; Volume 474, p. 052081. [Google Scholar]

- Kiddee, P.; Naidu, R.; Wong, M. H. Electronic waste management approaches: An overview. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1237–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanskanen, P. Management and recycling of electronic waste. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.; Caplan, S.; Horn, K.; Sharabi, M. Real-Time Defect Detection in Electronic Components during Assembly through Deep Learning. Electronics 2024, 13, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, C.; Ingman, J.; Varescon, E.; Kiviniemi, M. Detection of Cracks in Multilayer Ceramic Capacitors by X-ray Imaging. Microelectron. Reliab. 2016, 64, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E. Revealing Hidden Defects in Electronic Components with an AI-Based Inspection Method: A Corrosion Case Study. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 13, 1078–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Accountability Office. Defense Supply Chain DOD Needs Complete Information on Single Sources of Supply to Proactively Manage the Risks; Government Accountability Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spieske, A.; Birkel, H. Improving Supply Chain Resilience through Industry 4. 0: A Systematic Literature Review under the Impressions of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 158, 107452. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Chang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xu, H.; Chen, H.; Luo, Z. A Survey of Defect Detection Applications Based on Generative Adversarial Networks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 113493–113512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehranipoor, M.M.; Guin, U.; Forte, D. Counterfeit Integrated Circuits; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, L. W.; Sharpe, T. Faked Parts Detection of Counterfeiting of Electronics Components and Related Parts Is Widespread. but Newly Developed Methods Promise now to Help Identify Counterfeit Plastic-Encapsulated Components Using Detection Methods that Cannot Be Tricked. PLUS: The industry’s best up-close look at just how electronics components are faked and remarketed. Print. Circuit Des. Fab 2010, 27, 64.

- Aerospace Industries Association. Counterfeit Parts: Increasing Awareness and Developing Countermeasures; Aerospace Industries Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kishore, K. On the Crucial Role of On-Site and Visual Observations in Failure Analysis and Prevention. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2021, 21, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, G.S.; McPherson, J. W. Modeling of Interconnect Dielectric Lifetime under Stress Conditions and New Extrapolation Methodologies for Time-Dependent Dielectric Breakdown. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium Proceedings, 45th Annual, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 15–19 April 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Ohring, M.; Kasprzak, L. Chapter 9–Degradation of Contacts and Package Interconnections. In Reliability and Failure of Electronic Materials and Devices; Ohring, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 475–537. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Shen, H. Solder Joint Defect Detection in the Connectors Using Improved Faster- Rcnn Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Shukla, A.; Probst, R. The State of Health of Electrical Connectors. Machines 2024, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gaidai, O.; Sui, H.; Li, B. PO-YOLOv5: A Defect Detection Model for Solenoid Connector Based on YOLOv5. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambat, R.; Conseil-Gudla, H.; Verdingovas, V. Corrosion in Electronics. In Encyclopedia of Interfacial Chemistry: Surface Science and Electrochemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 134–144. ISBN 9780128098943. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, E. Preventing Corrosion-Related Failures in Electronic Assembly: A Multi-Case Study Analysis. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 13, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al- Zogbi, L.M.; Das, D.; Rundle, P.; Pecht, M. Breaking the Trust: How Companies Are Failing Their Customers. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 52522–52531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, GM; Hendry, L. C.; Stevenson, M. Supply Chain Traceability: A Review of the Benefits and Its Relationship with Supply Chain Resilience. Prod. Plan. Control 2023, 34, 1114–1134.

- Hienonen, R.; Lahtinen, R. Corrosion and Climatic Effects in Electronics; VTT Technical Research Center of Finland: Espoo, Finland, 2000; ISBN 9513858529. [Google Scholar]

- Sabat, W.; Klepacki, D.; Kamuda, K.; Kuryło, K. Analysis of LED Lamps’ Sensitivity to Surge Impulse. Electronics 2022, 11, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendsche, S.; Vick, R.; Habiger, E. Modeling and testing of immunity of computerized equipment to fast electrical transients. IEEE Trans. Electromagnetic Compat. 1999, 41, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.; Kwak, S.I.; Kwon, J. H.; Song, E. Simulation-Based System-Level Conducted Susceptibility Testing Method and Application to the Evaluation of Conducted-Noise Filters. Electronics 2019, 8, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Kennel, R.; Reddig, M.; Schlenk, M. Surge immunity test analysis for modern switching mode power supplies. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Telecommunications Energy Conference (INTELEC), Austin, TX, USA, 23–27 October 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Vrignon, B.; Caunegre, P.; Shepherd, J.; Wu, J. Automatic verification of EMC immunity by simulation. In Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Electromagnetic Compatibility of Integrated Circuits (EMC Compo), Nara, Japan, 15–18 December 2013; pp. 202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Sabat, W.; Klepacki, D.; Kuryło, K.; Kamuda, K. Mathematical Model of the Susceptibility of an Electronic Element to a Standardized Type of Electromagnetic Disturbance. Energies 2023, 16, 7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonschorek, K.-H.; Vick, R. Electromagnetic Compatibility for Device Design and System Integration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Humayun, M.; Jhanjhi, N.; Hamid, B.; Ahmed, G. Emerging Smart Logistics and Transportation Using IoT and Blockchain. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2020, 3, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, S.; Esbensen, K.; Geladi, P. Principal component analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1987, 2, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Wu, W.; Massart, D.L.; Boucon, C.; de Jong, S. Feature selection in principal component analysis of analytical data. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2002, 61, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Guo, Z.; Mei, D. Feature Selection Using Principal Component Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on System Science, Engineering Design and Manufacturing Informatization, Yichang, China, 12–14 November 2010; pp. 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Atik, I. Classification of Electronic Components Based on Convolutional Neural Network Architecture. Energies 2022, 15, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelenko Alexandra Viktorovna. “Scientific and technological directions of increasing the efficiency of the organization of production of electronic component base products in the context of import substitution “. diss. for the degree of candidate of technical sciences. 2017. Specialist. 05.02.22. https :// www . dissercat . com / content / nauchno - tekhnologicheskie - napravleniya - povysheniya - effektivnosti - organizatsii - proizvodstva - i (In Russian).

- Ali, S.; Hafeez, Y.; Humayun, M. ; Jhanjhi, NZ; Ghoniem, R. M. An Aspects Framework for Component-Based Requirements Prediction and Regression Testing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, M.; Chatzipetrou, P.; Wnuk, K.; Alégroth, E.; Gorschek, T.; Papatheocharous, E.; Shah, S. M. A.; Axelsson, J. Selecting Component Sourcing Options: A Survey of Software Engineering’s Broader Make-or-Buy Decisions. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2019, 112, 18–34. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0950584919300710?via%3Dihub.

- Umran Alrubaee, A.; Cetinkaya, D.; Liebchen, G.; Dogan, H. A Process Model for Component-Based Model-Driven Software Development. Information 2020, 11, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W. C.; Atukeren, E.; Yim, H. Overseas Market Expansion Strategy of the Global Electronic Components Company Based on the AHP Analysis of Factors in Technology, Organization, and Environment Context: A Case of Samsung Electro-Mechanics. Systems 2023, 11, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methodology for constructing a distributed information system for searching scientific and technical information based on an object data model. Shvedenko V.N., Shchekochikhin O.V., Sinkevich E.A. VINITI RAS, Journal: Scientific and technical information. Series 2: Information processes and systems, 2020, no. 2. pp. 7–14. (In Russian).

- Shvedenko V. N., Shvedenko V. V., Shchekochikhin O. V. Application of structural polymorphism in the creation of process management information systems // Scientific and technical information. Ser. 2. - 2018. - No. 11. - P. 9-15. (In Russian).

- Shvedenko V. N., Shvedenko V. V., Shchekochikhin O. V. Using structural and parametric polymorphism in creating digital twins // Scientific and technical information. Ser. 2. - 2019. - No. 3. - P. 21-24. (In Russian).

- Shvedenko V.N., Shchekochikhin O.V., Cherkasova N.V. Search for an architectural solution for information support of a digital twin of a complex system // Scientific and technical information. Ser. 2. - 2020. - No. 4. - P. 18-21. (In Russian).

- Component selection tool employs AI algorithms. https://www.edn.com/component-selection-tool-employs-ai-algorithms/#:~:text=At%20a%20time%20when%20there,time%20component%20recommendations%20that%20work.

- Michael Mariani. Why Mitigating Obsolescence During Electronic Component Selection Is a Critical Risk Management Strategy. https://www.z2data.com/insights/mitigating-obsolescence-during-electronic-component-selection-is-critical#:~:text=Component%20Obsolescence%20Is%20on%20the,Rise.

- Search for electronic components and electrical equipment from more than 900 suppliers in Russia and abroad. https://efind.ru/ (In Russian).

- ChipFind: Search for electronic components in 3050 supplier warehouses: Russia, Ukraine, foreign suppliers. https://www.chipfind.ru/ (In Russian).

- Octopart. Platform for access to data on electronic components. https://www.altium.com/ru/.

- Wizerr, AI. Wizerr AI. Your AI -Teammate for Electronic Components. https://www.wizerr.ai/.

- Conrad Wolfenstein . Search Engines and AI: Crawling Websites and AI to Trustworthy Search Results. https://xpert.digital/ru/%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B7%D1%83%D0%BB%D1%8C%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%82%D1%8B-%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B0-m8jwayk5/#:~:text=%D0%9F%D0%BE%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2%D1%8B%D0% B5%20%D1%81%D0%B8%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BC%D1%8B%20%D0%B8%20%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%BA%D1%83%D1%81%D1%81%D 1%82%D0%B2%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%BD%D1%8B%D0%B9%20%D0%B8%D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BB%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%82 , (In Russian).

- https://optochip.org/.

- https://www.findchips.com/.

- https://www.farnell.com/.

- siliconexpert.com.

- cdn.ihs.com.

- The New Era of Electronics Design. https://www.celus.io/.

- https://cdn.ihsmarkit.com/.

- Transforming Electrical and Electronic Systems Design. https://www.zuken.com/en/.

- https://www.altium.com/.

- http://developer.digikey.com/.

- Mohd. Abbas Rizvi. Automated Electronic Component Selection: A Machine Learning approach. Final Thesis MSc. Business Information Technology. 67 p. 2022. Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Mathematics & Computer Science University of Twente Drienerlolaan 5. 7522 NB Enschede The Netherlands. https://essay.utwente.nl/90637/1/RIZVI_MBIT_EEMCS.pdf.

- Stofkova, J.; Krejnus, M.; Stofkova, KR; Malega, P.; Binasova, V. Use of the Analytic Hierarchy Process and Selected Methods in the Managerial Decision-Making Process in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11546. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/18/11546. [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Liu, J.N.K.; Ngai, EWT Application of Decision-Making Techniques in Supplier Selection: A Systematic Review of Literature. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 3872–3885. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S095741741201281X?via%3Dihub.

- Subrata Chakraborty. TOPSIS and Modified TOPSIS: A comparative analysis. Decision Analytics Journal . Volume 2 , March 2022, 100021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dajour.2021.100021 . https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S277266222100014X.

- Petrillo, A.; Salomon, V.A.P. ; Tramarico, CL State-of-the-Art Review on the Analytic Hierarchy Process with Benefits, Opportunities, Costs, and Risks. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2023, 16, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunantara N. A review of multi-objective optimization: Methods and its applications. Cogent Engineering, 2018, vol. 5. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/23311916.2018.1502242?needAccess=true. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. A.; Chaabane, A.; Dweiri, FT Multi-criteria decision-making methods application in supply chain management: A systematic literature review. In Multi-Criteria Methods and Techniques Applied to Supply Chain Management; Salomon, V., Ed.; Tech Open: London, UK, 2018; pp. 3–31. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/59664.

- Y. Fukano, S. Obara. K. Hoshino, Y. Sugure. Japanese Patent JP 2023-025831. “Electronic component selection system and method.” Geneva, Jan. 19. Hitachi Astemo, Ltd. 2520, Takaba, Hitachinaka-shi, Ibaraki 3128503. Published on Jan 16, 2025. https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/WO2025013271 (In Japanese).

- Changing tides: the new role of resilience and sustainability in logistics and supply chain management: innovative approaches for the shift to a new era. ISBN 978-3-756541-95-9. [CrossRef]

- Adapting to the future: how digitalization shapes sustainable logistics and resilient supply chain management. ISBN 978-3-754927-70-0. [CrossRef]

- Data science and innovation in supply chain management: how data transforms the value chain. ISBN 978-3-750249-49-3. [CrossRef]

- Artificial intelligence and digital transformation in supply chain management: innovative approaches for supply chains. ISBN 978-3-750249-47-9. [CrossRef]

- The road to a digitalized supply chain management. ISBN 978-3-746765-35-8. [CrossRef]

- Where do we get information about our components? Cellus Knowledge Base. https://www.celus.io/knowledge/where-do-we-get-information-about-our-components#:~:text=supporting%20electronics%20engineers%20and%20technical,shortages%2C%20and%20ensuring%20environmental%20compliance.

- Zakeri, S. , Chatterjee, P., Konstantas, D. et al. A decision analysis model for material selection using simple ranking process. Sci Rep 13, 8631 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Certificate of state registration of computer program No. 2023614155 Russian Federation, Program for visualization of data on electronic products: application No. 2023612746, date of receipt 02/14/2023: date of state registration in the Register of computer programs 02/27/2023 / Rubtsov Yu.V., Dormidoshina D.A., Krinitsky V.V., Kurilov A.V., Okunev K.E.; applicant JSC Central Design Bureau Dayton.

- Certificate of state registration of computer program No. 2022683437 Russian Federation, Program for the formation of a database of electronic products: application No. 2022682511, date of receipt 11/22/2022: date of state registration in the Register of computer programs 12/05/2022 / Rubtsov Yu.V., Dormidoshina D.A., Krinitsky V.V., Shishkova Yu.M., Okunev K.E.; applicant JSC Central Design Bureau Dayton.

- Certificate of state registration of computer program No. 2022668891 Russian Federation, Program for managing data on electronic products: application No. 2022667557, date of receipt 09/27/2022: date of state registration in the Register of computer programs 10/13/2022 / Rubtsov Yu.V., Dormidoshina D.A., Krinitsky V.V., Vladimirov A.I., Okunev K.E.; applicant JSC Central Design Bureau Dayton.

- Certificate of state registration of the database No. 2015621293 Russian Federation, Electronic Components Buildings: application No. 2015620803, date of receipt 06/26/2015: date of state registration in the Database Register 08/26/2015 / Gryaznova T.V., Dovgan I.D., Rubtsov Yu.V. applicant JSC Central Design Bureau Dayton.

- Analog Devices, Inc., 1994. Design-in Reference Manual: Data converters, Amplifiers, Special linear products, Support Components. https://dn721907.ca.archive.org/0/items/bitsavers_analogDevilogDevicesDesignInReferenceManual_187344457/1994_Analog_Devices_Design-In_Reference_Manual.pdf.

- MAXIM 1995 New Releases Data Book. Vol. 4.

- Burr Bruwn IC Data Book, Linear Products, 1995. https://archive.org/details/burrbrownintegra00burr.

- AMP04. Data Sheet. Analog Devices. https://www.rlocman.ru/i/File/2020/09/09/AMP04.pdf.

- AMP04. Data Sheet. Analog Devices. https://www.rlocman.ru/i/File/2017/10/09/AD7714.pdf.

| System | Functionality | Using AI | Supplier support | Selection of analogues | Interface (languages) | API Openness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digi-Key (search in wiki, distribu tor) | Parametric search by catalog; current prices and balances; datasheets, applications; community forums. | No (traditional filters and search). | One supplier (Digi-Key’s own warehouse, + Market place). | Partially (alternatives are recommended when the product is unavailable). | English + partial translation into other languages [1]. | Yes (REST API for catalog and orders [81]). |

| Octopart (aggregator / search engine) | Search by name and parameters in a database of >60 million components [80]; information about many distributors; integration with CAD. | Clearly not (focus on data aggregation; intelligent search by parameters). | Multiple suppliers (data directly from distributors and manufacturers) [80]. | Yes (there are lists of substitutions and equivalents, if known). | Interface in English (Altium website with description is multi lingual). | Yes (open API for search and BOM services [75]). |

| SiliconExpert (MDM platform) | Global database; deep attributes, EOL/PCN statuses; BOM analysis; change notifications; regulatory compliance. | Yes (lifetime prediction, ML-based risk analysis) [75]. | Thousands of suppliers (neutral database) [75]. | Yes (shows recommended substitutes, secondary sources). | English (focused on the global market; localizations are limited). | Partially (API access for clients, integration with CAD/PLM [76]). |

| IHS Markit (Accuris) (MDM platform) | Huge database (>540 million records) [76]; technical data + life cycle, compliance; search for components and manufac turers; reports and analytics. | There are elements (obsolescence analytics, reliability ratings). | Wide coverage of manufacturers and distributors (neutral base) [77]. | Yes (provides lists of cross- references, replace ments). | English ( de facto industry standard; possibly some Chinese/Japanese for local versions). | Yes ( Parts XML web services, integration with systems like Celus [77]). |

| Zuken Component Manage ment (CAD) / PLM integ ration) | Corporate component library; search within approved components by parameters; model binding; Component Cloud with validated data [79]. | No (traditional base, filled manually or by import). | Depends on the content (usually data on suppliers manually or from external sources). | Limited (analogues are set manually or through a filter by parameters). | English, Japanese (developer – Zuken, Japan; no Russian interface). | Limited (API for integration with PLM, but not publicly open). |

| Siemens EDA / PartQuest (CAD integra tion) | Integrated component search; corporate catalog in Xpedition; connection to Teamcenter PLM; component status management. | No (basic functionality without ML, rules and filters). | Several (via PartQuest access to a number of distributors, otherwise - only your own lists). | Yes, partially (PartQuest issued similar Digi-Key items, the internal catalog may contain substitutes). | English (Mentor / Siemens interfaces, possibly support for individual languages locally). | Yes, for corporate integration (scripts, ODBC/SQL to the library; PartQuest open API was for partners). |

| Note: The table only covers some of the systems presented; there are others (e.g., Cadence CIP, Celus, domestic eFind / chipfind, Wizerr AI platform, etc.). The data provided is relevant for recent years and may change as the systems evolve. | ||||||

| V OS mcV | V OSTC mcV /C | S N mcV | GBW MHz | SR V/ mcs | I B nA | F1, kHz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OP 177 A | 10 max | 0.2 type | 0.3 5 type | 0.6 type | 0.3 type | 1.5 max | 110 |

| AD 70 7 | 25 max | 15 max 5 type |

0.23 type | 0.9 type | 0.3 type | 1.0 max | 1 0 0 |

| AD 705 A | 90 max | 1.2 max 0.2 type |

0.5 type | 0.8 type | 0.3 type | 0.06 typ 0.15 max |

110 |

| OP97 A | 25 max 10 type |

0.3 type | 0.5 type | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 max 0.03 typ |

100 |

| AD846 A | 2 00 max 25 type |

5 max 0.8 type |

0.2 | 80 | 450 | 250 | 80 small 16 full amp |

| AD797 | 40 – 100 | 0.8 – 1.5 | 0.05 | 100 | 18 | 50– 1000 | 130 |

| AD706 | 50 – 100 | 0.5 – 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.15 | 0.11– 0.2 | 110 |

| OP497 | 50 – 150 | 0.5 – 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.1– 0.2 | 130 |

| OP297 | 50 – 200 | 0.6 – 2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.1– 0.2 | 105 |

| OP113 | 75 – 250 | 0.8 – 1.5 | 0.12 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 50 | 116 |

| OP213 | 100–250 | 0.8 – 1.5 | 0.12 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 50 | 116 |

| OP413 | 125–275 | 0.8 – 1.5 | 0.12 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 50 | 116 |

| OP227 | 80–180 | 1 – 1.8 | 0.08 | 8 | 2.8 | 40 – 80 | 125 |

| AD844 | 150–300 | 1.2 – 2.5 | 0.5 | 900 | 2000 | 250 | - |

| OP271 | 200-400 | 2 – 5 | - | 5 | 8.5 | 20 – 60 | 126 |

| AD795 | 250–500 | 1 – 10 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.001–0.004 | 110 |

| OP41 | 250–2000 | 5 – 10 | - | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.005–0.02 | 100 |

| OP470 | 400–1000 | 2 – 4 | 0.08 | 6 | 2 | 25 – 60 | 110 |

| V OS mcV | V OSTC mcV /C | S N mcV | GBW MHz | SR V/ mcs | I B nA | F1, kHz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OP 177 A | 10 max | 0.2 type | 0.3 5 type | 0.6 type | 0.3 type | 1.5 max | 110 |

| AD 705 A | 90 max | 1.2 max 0.2 type |

0.5 type | 0.8 type | 0.3 type | 0.06 typ 0.15 max |

110 |

| AD797 | 40 – 100 | 0.8 – 1.5 | 0.05 | 100 | 18 | 50– 1000 | 130 |

| AD706 | 50 – 100 | 0.5 – 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.15 | 0.11– 0.2 | 110 |

| OP497 | 50 – 150 | 0.5 – 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.1– 0.2 | 130 |

| OP227 | 80–180 | 1 – 1.8 | 0.08 | 8 | 2.8 | 40 – 80 | 125 |

| AD844 | 150–300 | 1.2 – 2.5 | 0.5 | 900 | 2000 | 250 | - |

| AD795 | 250–500 | 1 – 10 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.001–0.004 | 110 |

| OP470 | 400–1000 | 2 – 4 | 0.08 | 6 | 2 | 25 – 60 | 110 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).