Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- STEP ONE: The method begins with a search in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) [22] for an experimental crystallographic information file (CIF); the identifier 733458 was used in this case. From the CIF, a “motif” was identified in the first step, defined as the PDB file residue. The choice of residue was made to facilitate the creation of the crystal structure (Fm-3m) in the fcc lattice, avoiding the duplication of atoms during unit cell formation.

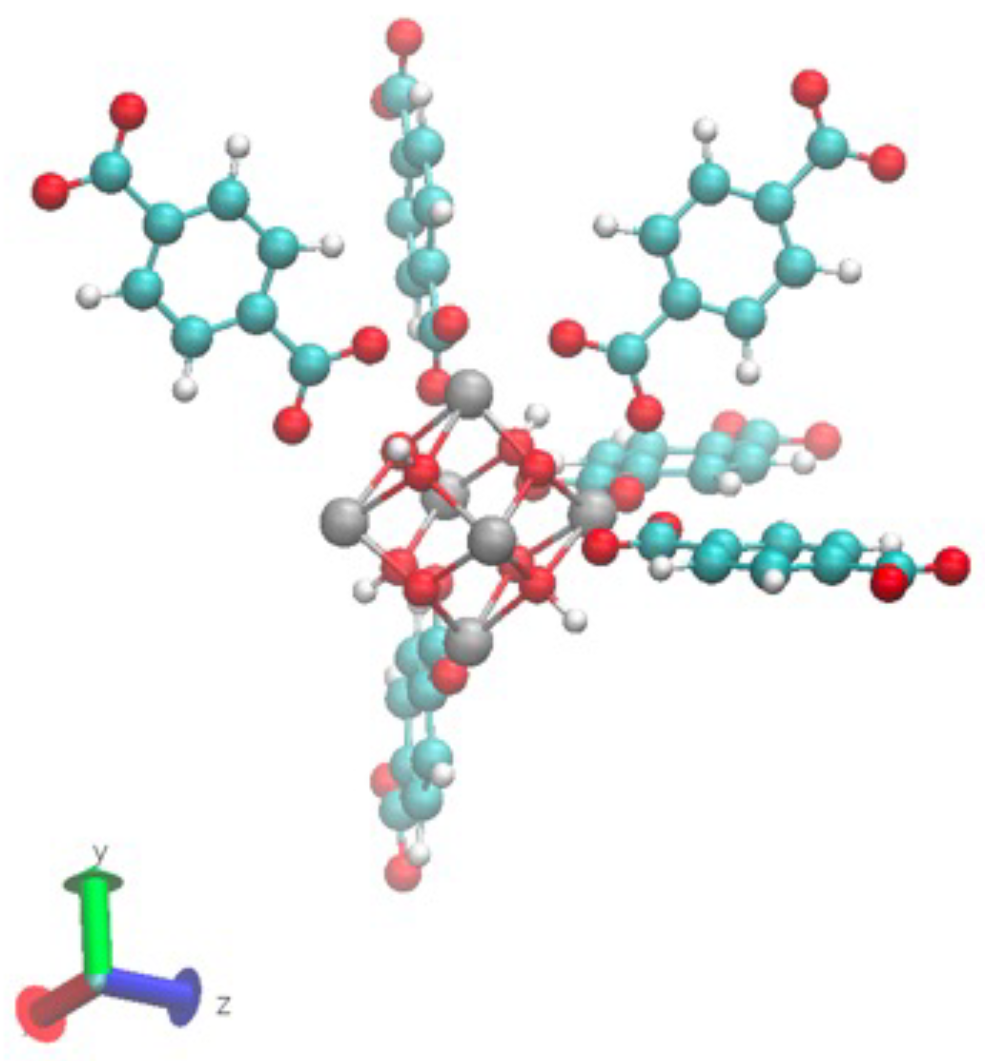

- STEP TWO: The motif was made by hand using VESTA [23] to open the CIF file and export it to an XYZ file, Avogadro [24] to open the XYZ file to build the motif and add hydrogens, and a text editor to assign different atom names to each atom in the motif to link the information with the force field and the PSF file. The result of this step is shown in Figure 3. The force field file, which is called par_file.inp in Figure 2, defines the atom types and was also created in this step. The connections between atom names and atom types were made in step four.

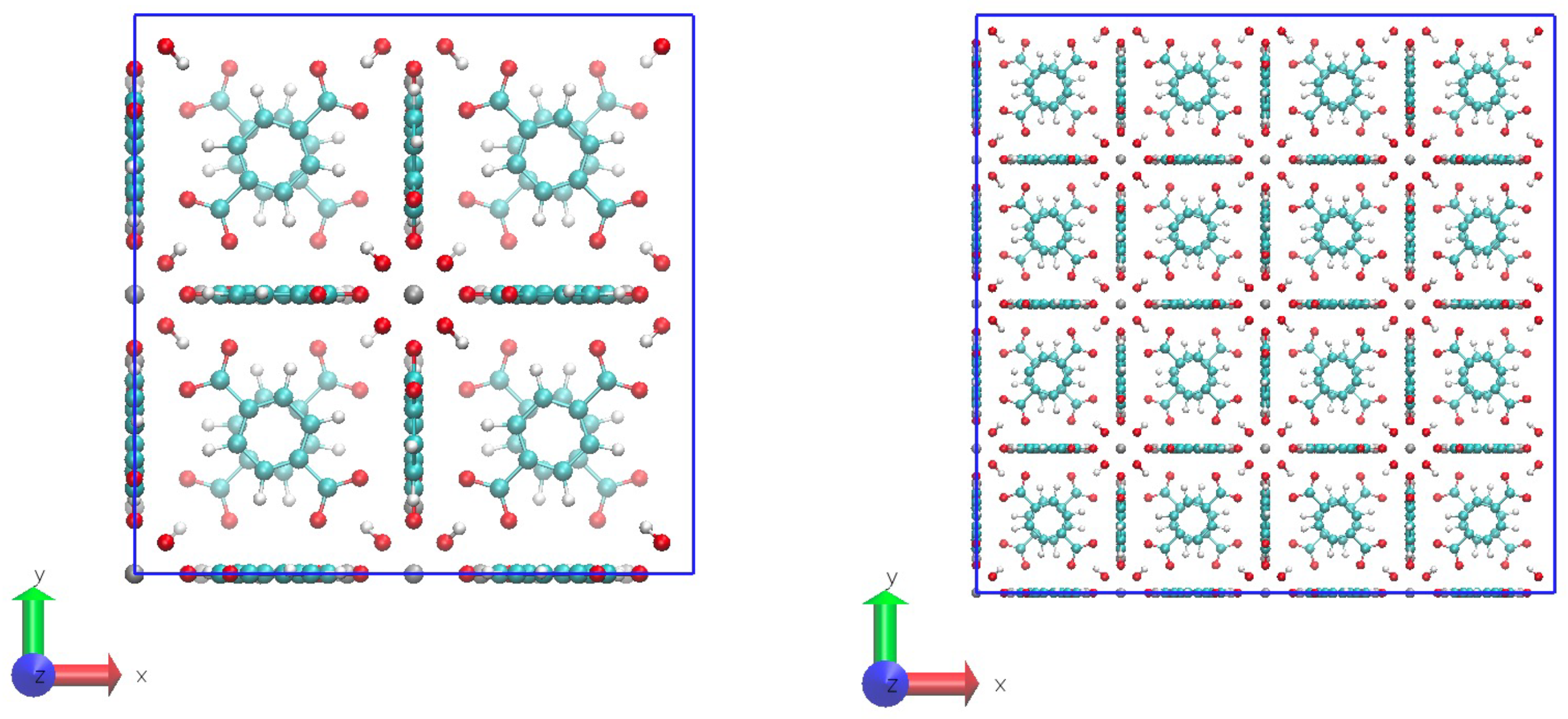

- STEP THREE: The unit cell of the UiO-66 was created with a homemade code by repeating the motif in the face-centered-cubic lattice. Here, a super cell of 2x2x2 unit cells was created and it was cut to fix it in a periodic box. Examples of the system are in Figure 4. Another homemade code was made to identify the pairs of atoms that must bond through the periodic boundary conditions to maintain the crystal structure. This resulted in a list of pairs of atoms, called pbc_bonds.tcl in Figure 2 to be read in the following step. This part must be clear whether the structure will be full-periodic (x, y, z) or semi-periodic (x, y) to build the appropriate list of atoms.

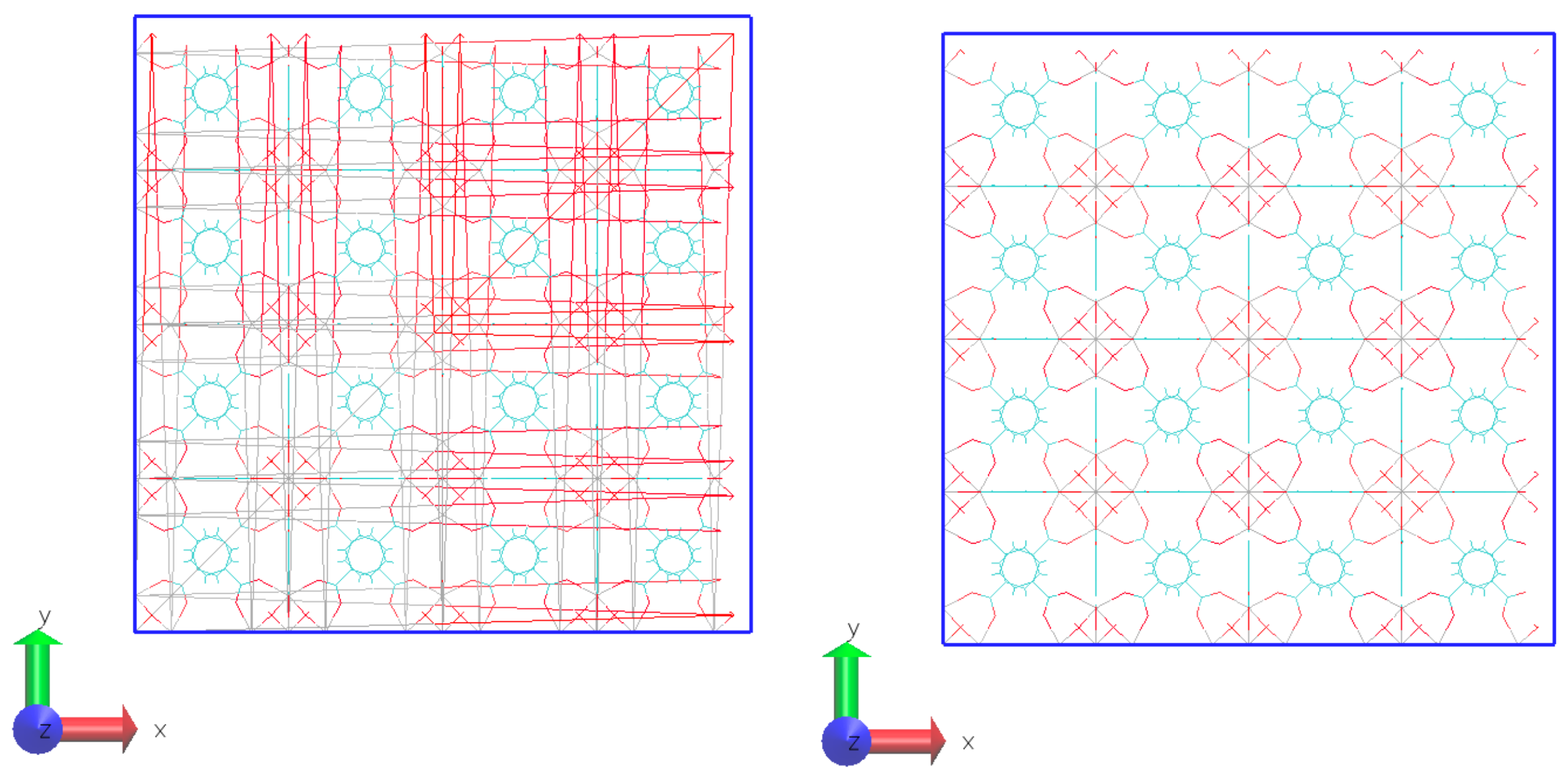

- STEP FOUR: The PSF file was created using the Topotools plugin [25] on VMD. The Topotools script defines the atom name, atom type, charge, and mass for each atom in the motif. Also, Topotools detects the bonds, angles, dihedrals, and impropers, including the list of pairs of atoms connected through the periodic boundary conditions. The PSF file connects pairs of atoms within the periodic boundary, rendering it unsuitable for visualizing snapshots, as the VMD would display connections with the periodic images of the system, resulting in numerous bonds spanning the box from side to side. For visualization, a second PSF file must be built, but not including the list of pairs of atoms from step three. Figure 5 shows the same system with the PSF file for calculation and visualization.

- STEP FIVE: The configuration file, called MD.conf in Figure 2, is created according to the desired kind of simulation, following the instructions in the NAMD user manual. At this point, it is important for the electrostatic treatment for the full-periodic system to use the PME (Particle Mesh Ewald) method and the semi-periodic system to use the MSM (Multilevel Summation Method). As in step four, Topotools automatically detects dihedrals and impropers, most of which may not be defined in the force field. When running NAMD, the software displays a message that a dihedral (or improper) has no defined parameters, and the atom type of the dihedral is reported. The solution is simple: each dihedral reported by NAMD must be included in the Force Field file with a constant force equal to zero.

3. Results

| Bulk | Surface | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | |

| Bond ZR-O1 (Å) | 2.256 | 2.219 | 2.294 | 2.234 | 2.197 | 2.272 |

| Angle O1-ZR-O1 (degree) | 66.96 | 63.48 | 70.62 | 59.34 | 56.32 | 62.99 |

| Dihedral ZR-O1-C1-C2 (degree) | 176.25 | 165.66 | 179.99 | 161.17 | 147.49 | 178.53 |

| Dihedral O1-C1-C2-C2 (degree) | 174.09 | 157.42 | 179.96 | -86.16 | -102.71 | -74.05 |

| Bulk | Surface | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | |

| Bond ZR-O1 (Å) | 2.257 | 2.210 | 2.293 | 2.260 | 2.219 | 2.298 |

| Angle O1-ZR-O1 (degree) | 66.94 | 63.88 | 69.92 | 60.47 | 58.13 | 63.67 |

| Dihedral ZR-O1-C1-C2 (degree) | 178.19 | 172.76 | 179.99 | 176.73 | 168.57 | 179.93 |

| Dihedral O1-C1-C2-C2 (degree) | 173.85 | 160.17 | 179.88 | 100.89 | 70.04 | 122.24 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MOF | Metal-organic framework |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| CIF | Crystal information file |

| PBD | Protein data bank file |

| PSF | Protein structure file |

References

- Cai, X.; Xie, Z.; Li, D.; Kassymova, M.; Zang, S.Q.; Jiang, H.L. Nano-sized metal-organic frameworks: Synthesis and applications. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2020, 417, 213366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowsell, J.L.C.; Yaghi, O.M. Metal–organic frameworks: a new class of porous materials. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2004, 73, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, B.M.; Al-Hamadani, Y.A.J.; Son, A.; Park, C.M.; Jang, M.; Jang, A.; Kim, N.C.; Yoon, Y. Applications of metal-organic framework based membranes in water purification: A review. Separation and Purification Technology 2020, 247, 116947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jobic, H.; Salles, F.; Kolokolov, D.; Guillerm, V.; Serre, C.; Maurin, G. Probing the Dynamics of CO2 and CH4 within the Porous Zirconium Terephthalate UiO-66(Zr): A Synergic Combination of Neutron Scattering Measurements and Molecular Simulations. Chemistry – A European Journal 2011, 17, 8882–8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehbe, M.; Abu Tarboush, B.J.; Shehadeh, M.; Ahmad, M. Molecular dynamics simulations of the removal of lead(II) from water using the UiO-66 metal-organic framework. Chemical Engineering Science 2020, 214, 115396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzabasaki, M.; Galdadas, I.; Tylianakis, E.; Klontzas, E.; Cournia, Z.; Froudakis, G.E. Multiscale simulations reveal IRMOF-74-III as a potent drug carrier for gemcitabine delivery. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2017, 5, 3277–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, K.M.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, J. Glucose recovery from aqueous solutions by adsorption in metal–organic framework MIL-101: a molecular simulation study. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 12821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babarao, R.; Jiang, J. Unraveling the Energetics and Dynamics of Ibuprofen in Mesoporous Metal−Organic Frameworks. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2009, 113, 18287–18291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, N.; Wang, Z.; Hu, S.; Mou, Y.; Li, Z.; Lyu, Q. Effect of linker configuration and functionalization on the seawater desalination performance of Zr-MOF membrane. Chemical Physics Letters 2021, 780, 138949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroushaki, T.; Dekamin, M.G.; Hashemianzadeh, S.M.; Naimi-Jamal, M.R.; Ganjali Koli, M. A molecular dynamic simulation study of anticancer agents and UiO-66 as a carrier in drug delivery systems. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 2022, 113, 108147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Paesani, F.; Lessio, M. Computational insights into the interaction of water with the UiO-66 metal–organic framework and its functionalized derivatives. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2023, 11, 10247–10258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Fan, X.; Wang, S.; Huang, L.; Ju, S.; Li, W. Insights into adsorption and diffusion of CO2, CH4 and their mixture in MIL-101(Cr) via molecular simulation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 480, 148215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohmmad, A.; Mosavian, M.H.; Moosavi, F. Pharmaceutically active compounds removal from aqueous solutions by MIL-101(Cr)-NH2: A molecular dynamics study. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 278, 116333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Materials Studio. Available online: https://www.3ds.com/products/biovia/materials-studio.

- NAMD. Available online: https://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/namd/.

- VMD. Available online: https://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/.

- Phillips, J.C.; Braun, R.; Wang, W.; Gumbart, J.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Villa, E.; Chipot, C.; Skeel, R.D.; Kalé, L.; Schulten, K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2005, 26, 1781–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, A.U.; Boutin, A.; Fuchs, A.H.; Coudert, F.X. Investigating the Pressure-Induced Amorphization of Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework ZIF-8: Mechanical Instability Due to Shear Mode Softening. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2013, 4, 1861–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CHARMM-GUI. Available online: https://charmm-gui.org.

- psfgen. Available online: https://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/plugins/psfgen/.

- Coudert, F.X. Reproducible Research in Computational Chemistry of Materials. Chemistry of Materials 2017, 29, 2615–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCDC. Available online: https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.

- VESTA. Available online: https://jp-minerals.org/vesta/en/.

- AVOGADRO. Available online: https://www.openchemistry.org/projects/avogadro2/.

- Topotools. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/akohlmey/software/topotools.

- Phillips, J.C.; Hardy, D.J.; Maia, J.D.C.; Stone, J.E.; Ribeiro, J.V.; Bernardi, R.C.; Buch, R.; Fiorin, G.; Hénin, J.; Jiang, W.; et al. Scalable Molecular Dynamics on CPU and GPU Architectures with NAMD. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2020, 153, 044130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, G.; Sun, Y.; Huang, L. A computational study of water in <span style="font-variant:small-caps;">UiO</span> -66 <span style="font-variant:small-caps;">Zr-MOFs</span> : Diffusion, hydrogen bonding network, and confinement effect. AIChE Journal 2021, 67, e17035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Han, Y. Bulk and local structures of metal–organic frameworks unravelled by high-resolution electron microscopy. Communications Chemistry 2020, 3, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 100 K, 1 atm | 350 K, 1 atm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Min | Max | Mean | Min | Max | |

| Bond ZR-O1 (Å) | 2.253 | 2.219 | 2.296 | 2.253 | 2.173 | 2.320 |

| Angle O1-ZR-O1 (degree) | 65.96 | 62.90 | 70.21 | 66.09 | 60.07 | 71.69 |

| Dihedral ZR-O1-C1-C2 (degree) | 176.12 | 168.98 | 179.99 | 174.30 | 160.55 | 179.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).