Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

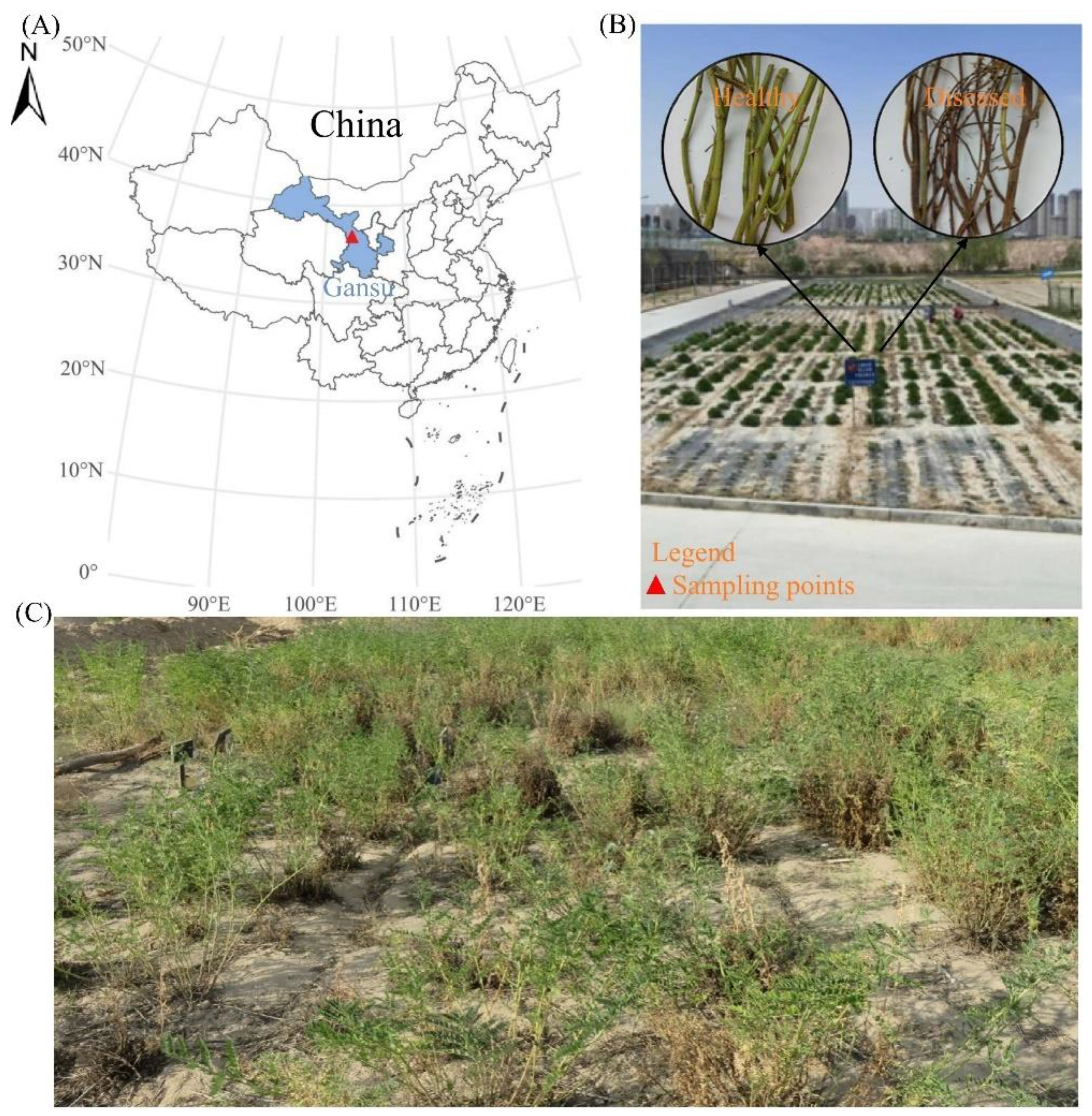

2.1. Overview and Management of the Experimental Site

2.2. Collection and Preservation of Plant Materials

2.3. Digestion of Grass Samples

2.4. Isolation and Cultivation of A.gansuense

2.5. Determination of Selenium Content

2.6. Determination of Mineral Elements

2.7. Preparation for Determination of Swainsonine

2.8. Sample Processing

2.9. Drawing and Measurement of the Standard Curve for Swainsonine

3. Results

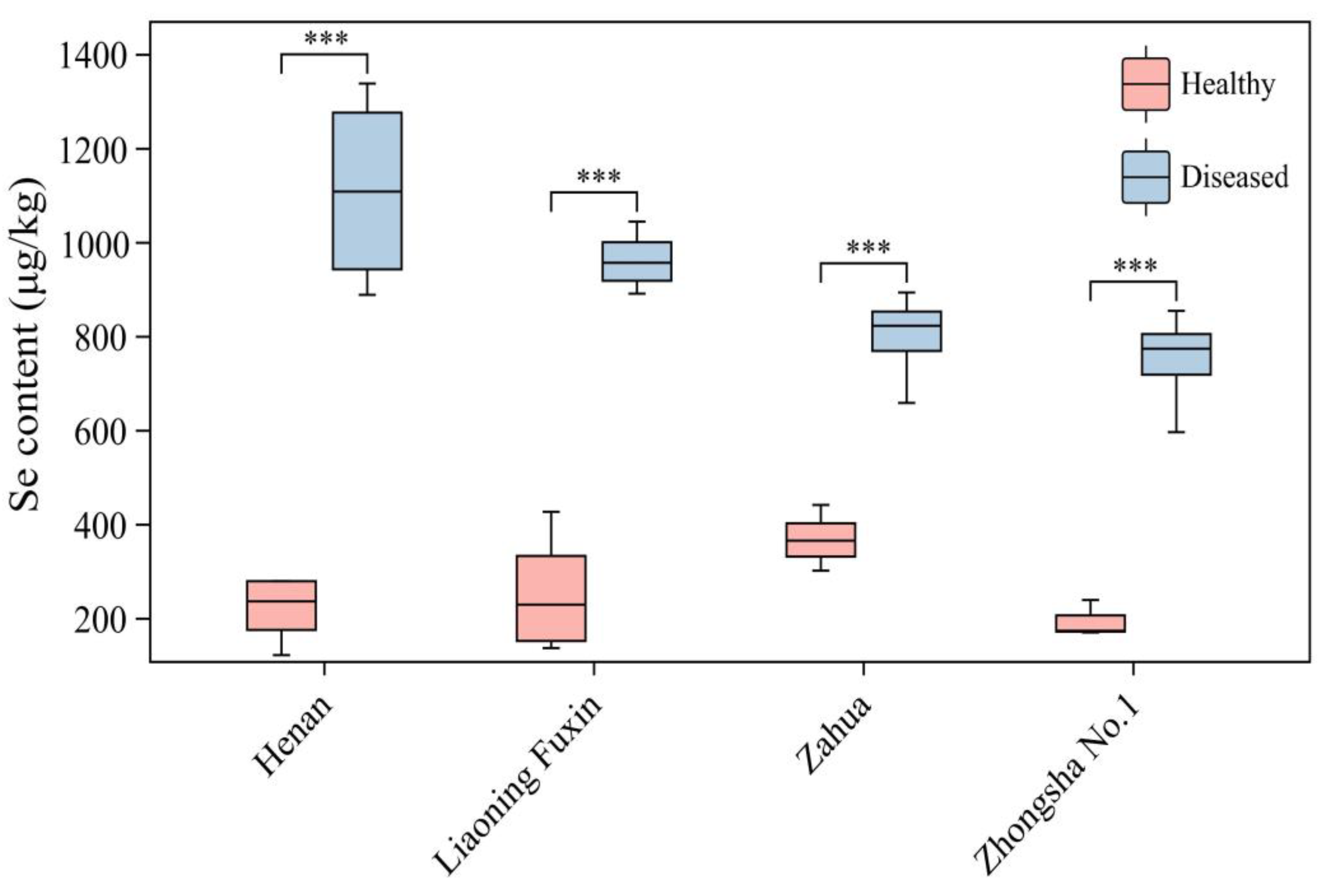

3.1. Determination Results of Selenium Content

3.2. Standard Curves for Other Mineral Elements

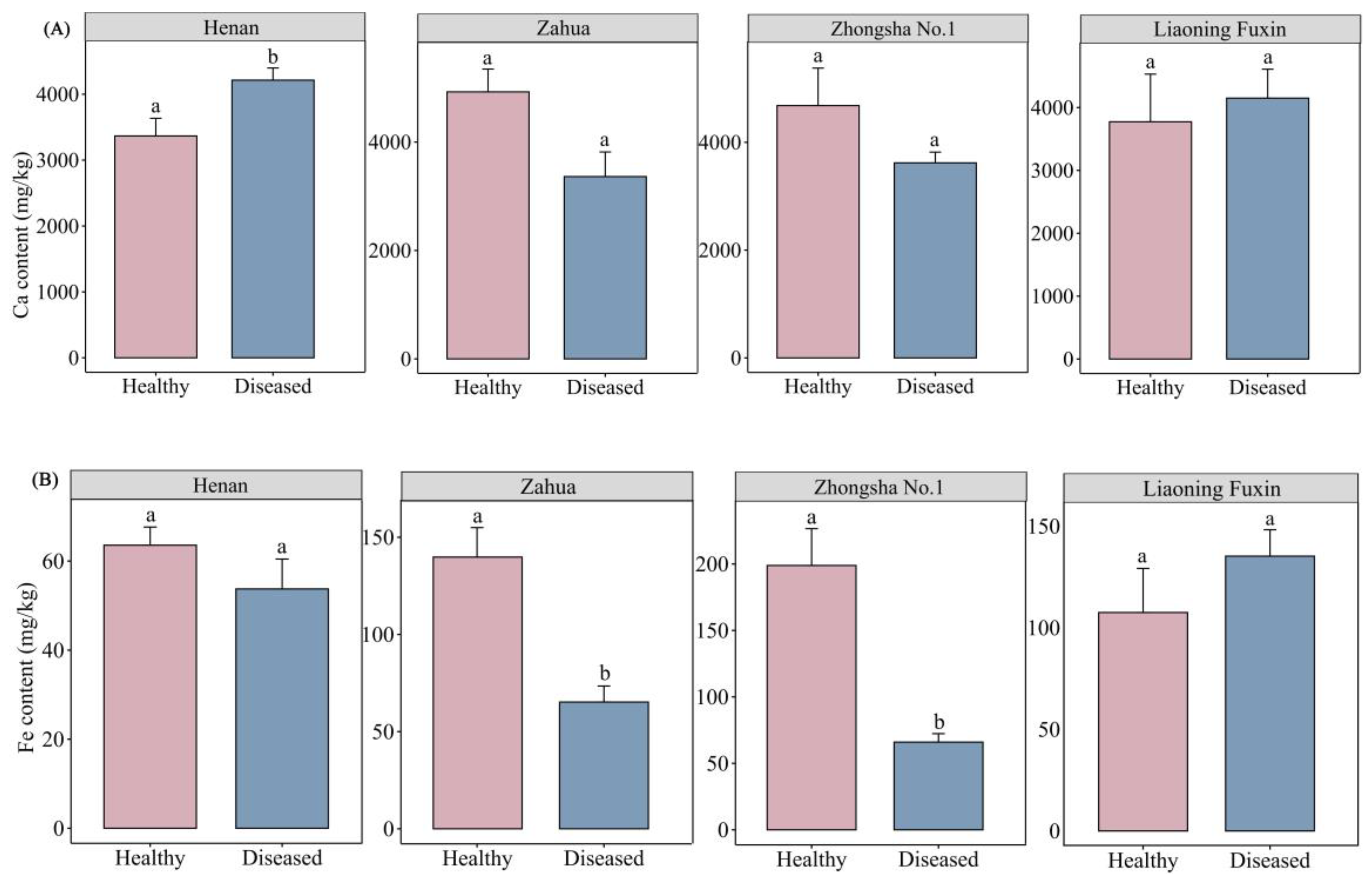

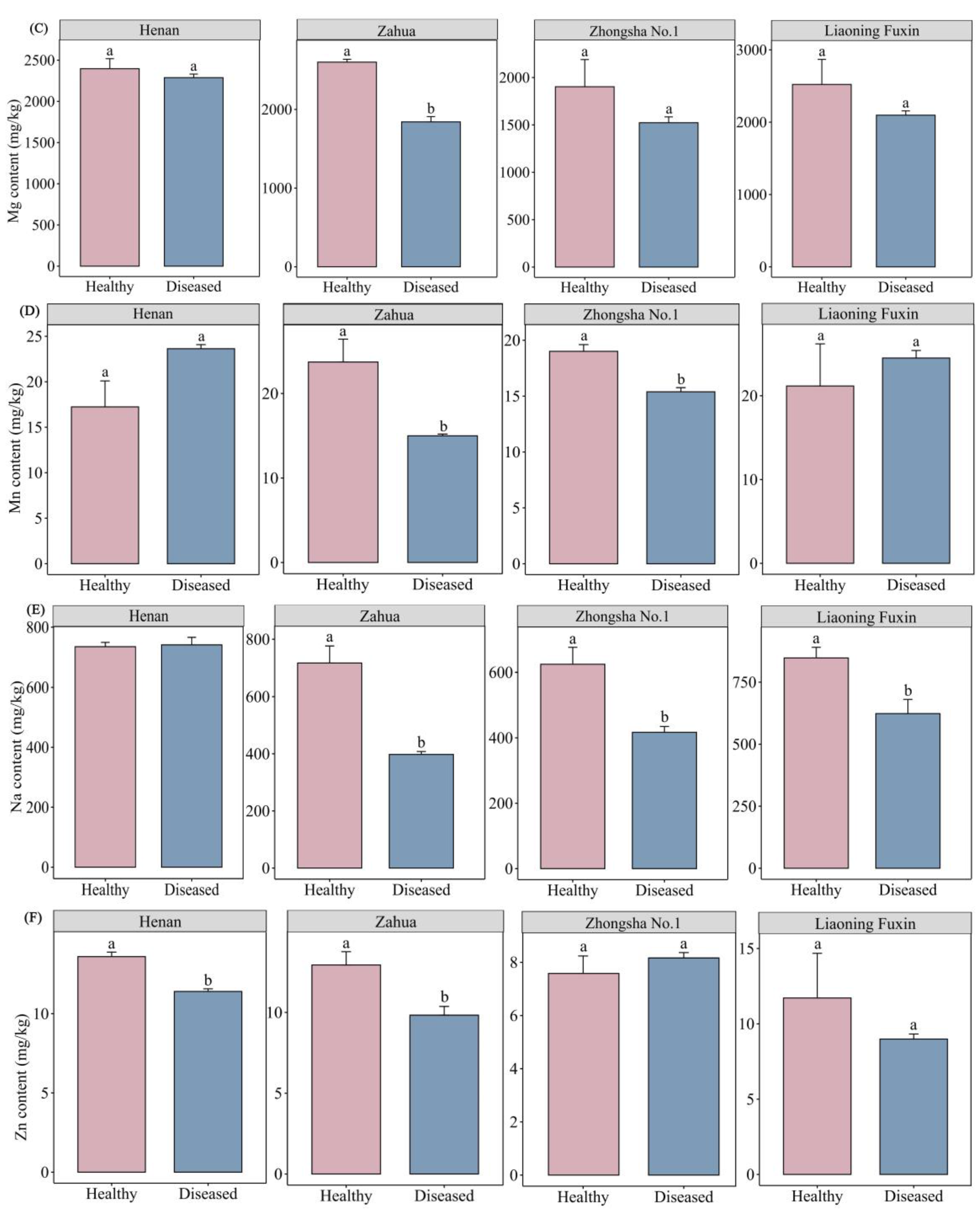

3.3. The content of Elements

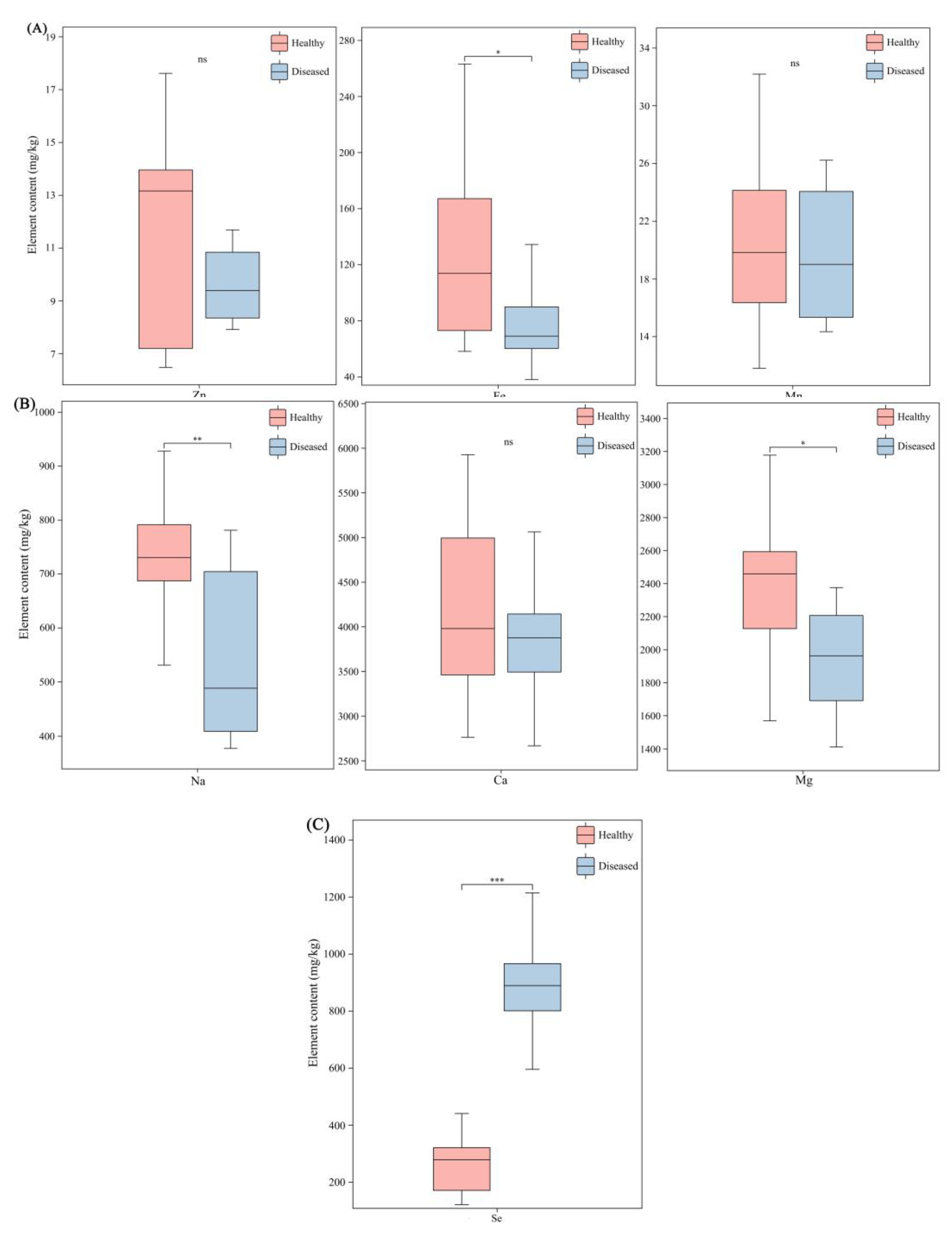

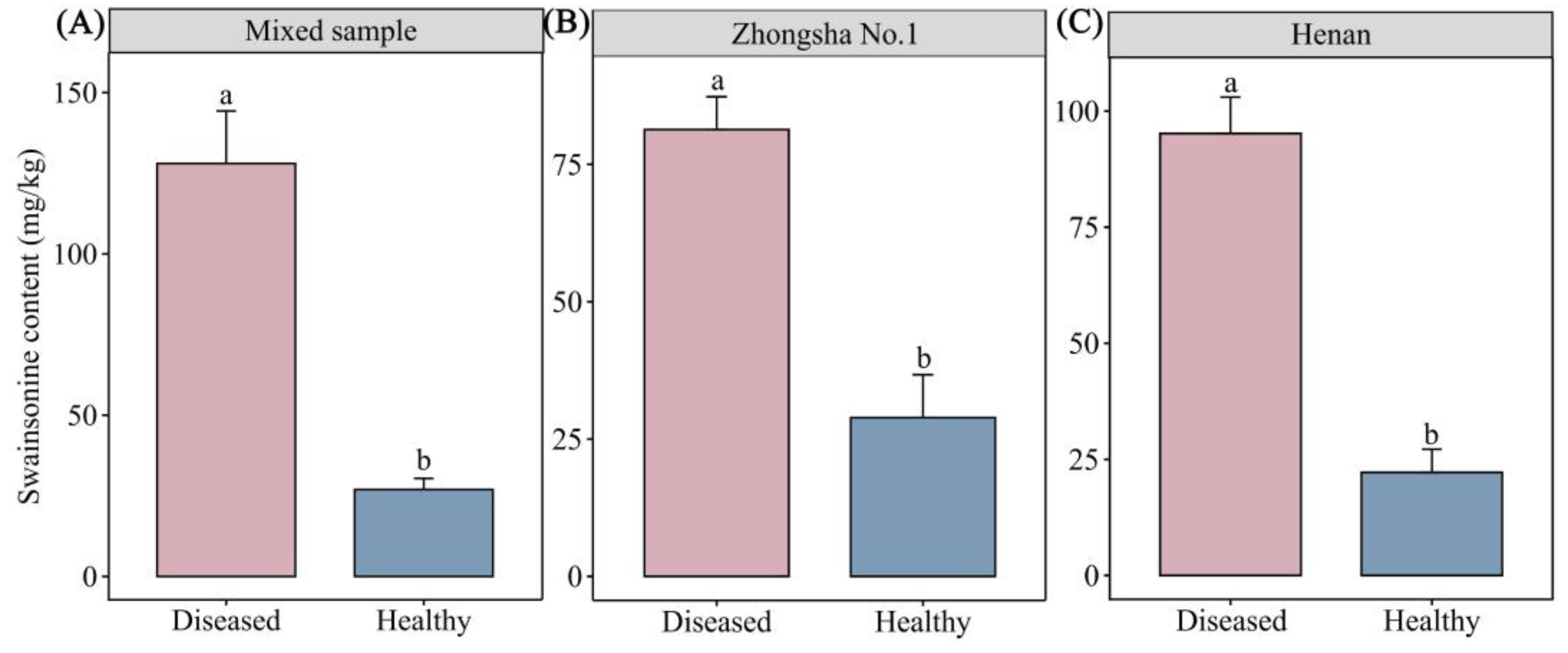

3.4. Results of Swainsonine Test

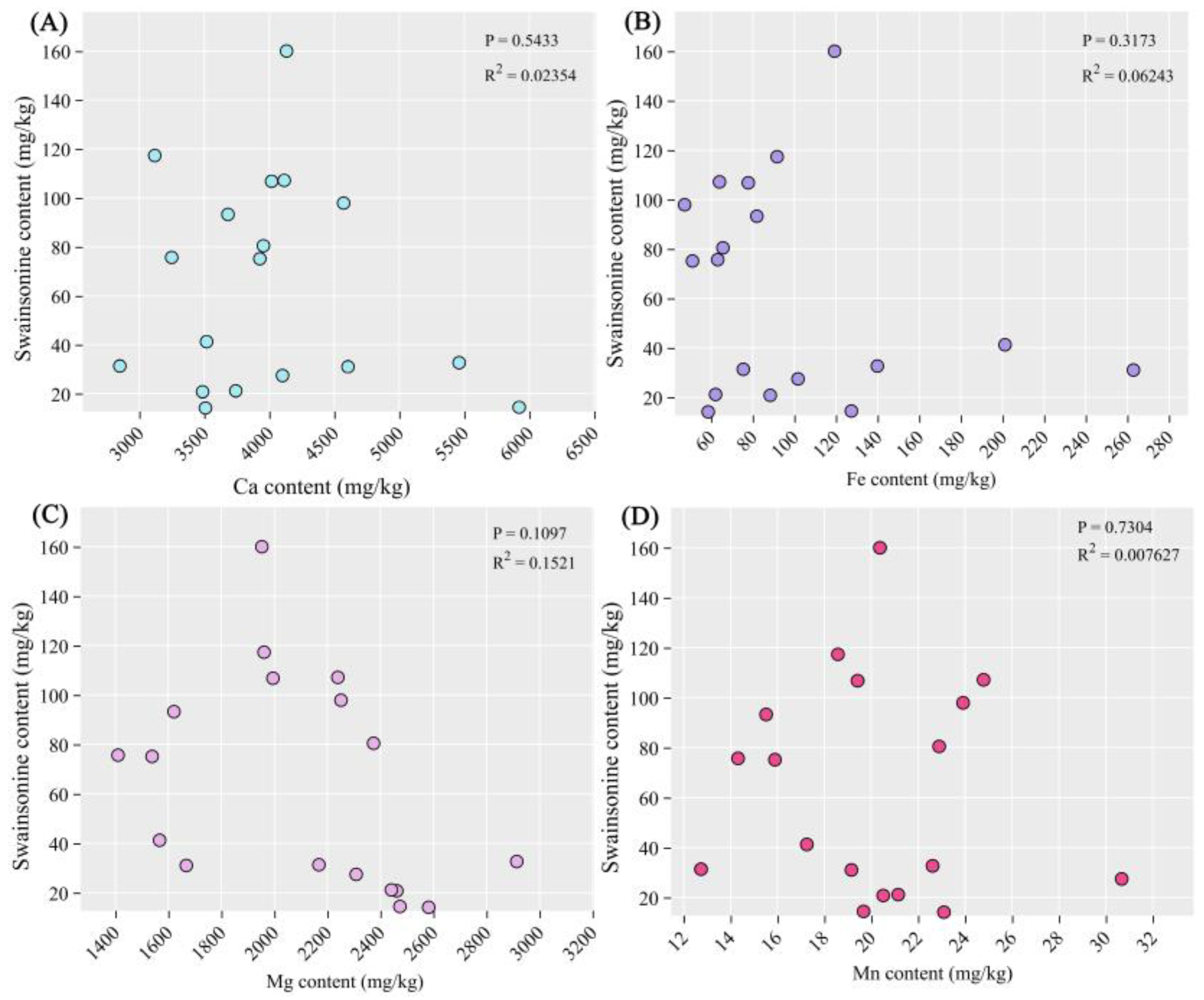

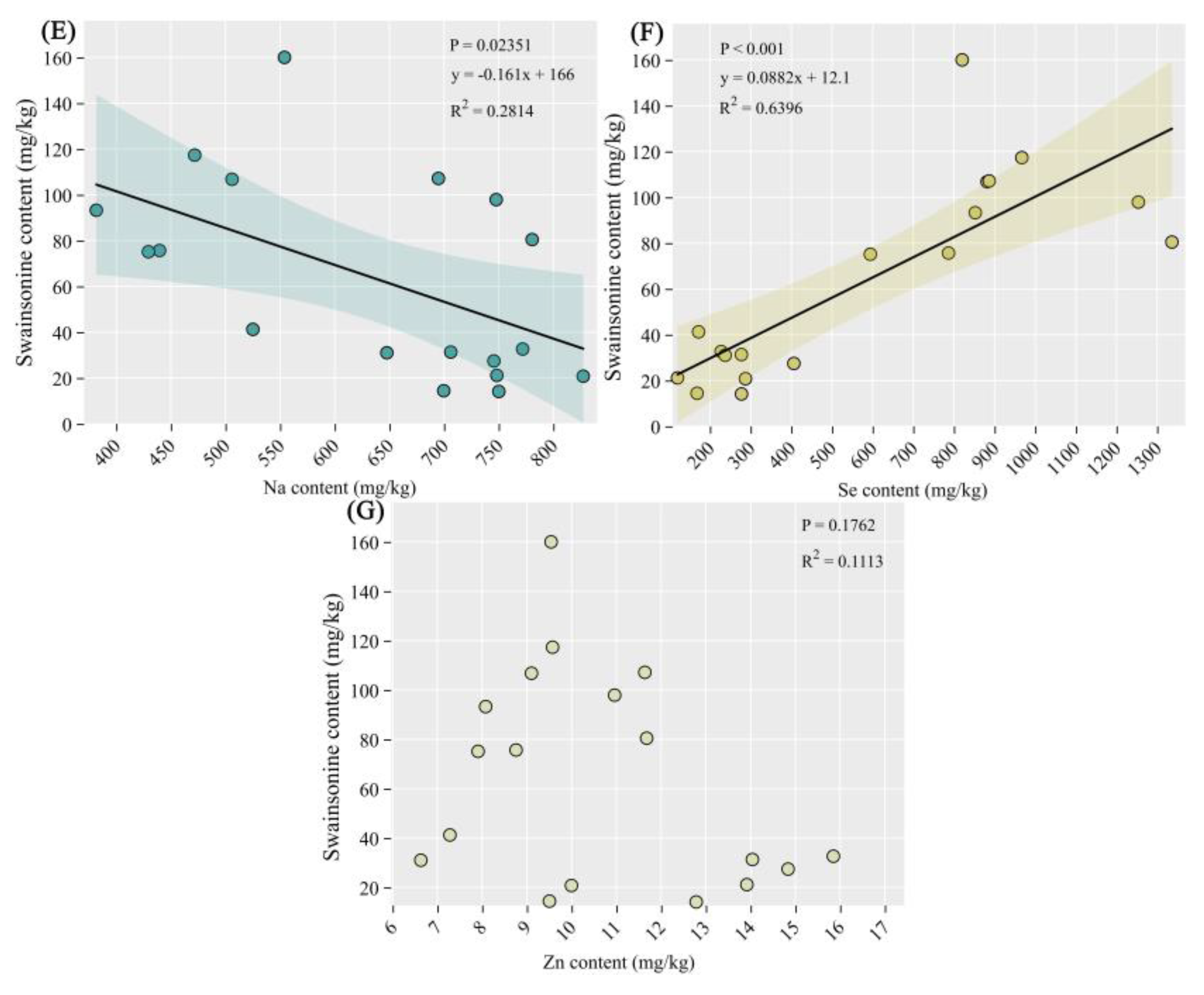

3.5. The correlation Between Swainsonine and Elements

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in Selenium Content of Diseased Plants and Its Impact on Livestock Feeding

4.2. Alterations in the Concentrations of Other Mineral Elements in Diseased A.adsurgens

4.3. The Influence of Changes in Swainsonine Content of Diseased Astragalus adsurgens on Livestock and Its Correlation with Mineral Elements

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, Q.Z.; Gui, R.; Na, R.S.; Nada, M.D.; Zhai, Z.H. Study on productivity of Astragalus adsurgens Pall. with different growth periods. Grassland of China 1999, 5, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Lei, Z.Y.; Feng, X.Q. Gas Chromatographic Determination of Trace 3-Nitropropionic Acid in Astragalus adsurgens. Grassland of China 1992, 3, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.F. Revisiting the Forage Utilization Issues of Astragalus adsurgens. Pratacultural Science 1987, 2, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, D.; Ralphs, M.; Welch, K.; Stegelmeier, B. Locoweed poisoning in livestock. Rangelands 2009, 31, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.G.; Dong, S.T.; Yang, Z.B.; Yang, W.R.; Jiang, S.Z. Experiment on Feeding Small-tailed Han Sheep with Astragalus adsurgens. Pratacultural Science 2008, 3, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Z.; Nan, Z.B. Symptomology and etiology of a new disease, yellow stunt, and root rot of standing milkvetch caused by Embellisia sp. in Northern China. Mycopathologia 2007, 163, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Nan, Z.B.; Hou, F.J. The roles of an Embellisia sp. causing yellow stunt and root rot of Astragalus adsurgens and other fungi in the decline of legume pastures in northern China. Australasian Plant Pathology 2007, 36, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L. Study on molecular biology of Embellisia astragali. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Z.; Nan, Z.B. A new species, Embellisia astragali sp. nov., causing standing milk-vetch disease in China. Mycologia 2007, 99, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woudenberg, J.H.C.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Binder, M.; Crous, P.W. Alternaria redefined. Studies in mycology 2013, 75, 171–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Li, Y.Z.; Creamer, R. A re-examination of the taxonomic status of Embellisia astragali. Current Microbiology 2016, 72, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z. Study of yellow stunt and root rot (Embellisia astragali sp. nov. Li & Nan) of Astragalus adsurgens. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Z.; Creamer, R.; Baucom, D.; Nan, Z.B. Pathogenic Embellisia astragali on Astragalus adsurgens is very closely related to locoweed endophyte. Phytopathology 2011, 101, S102–S103. [Google Scholar]

- James, L.F.; Hartley, W.J.; Kampen, K.R.V. Syndromes of astragalus poisoning in livestock. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1981, 178, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegelmeier, B.L.; James, L.F.; Panter, K.E.; Gardner, D.R.; Pfister, J.A.; Ralphs, M.H.; Molyneux, R.J. Dose response of sheep poisoned with locoweed (Oxytropis sericea). Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 1999, 11, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.C.; James, L.F. Toxicity of nitro-containing Astragalus to sheep and chicks. Journal of Range Management 1975, 28, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.H. Plant Biology, 2th ed.Science: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; Zamioudis, C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Weller, D.M.; Van Wees, S.C.M.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. Induced Systemic Resistance by Beneficial Microbes. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2014, 52, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, T.; Taiz, L. and Zeiger, E. Plant physiology. 3rd edn. Annals of Botany 2003, 91, 750–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.Y.; Xu, K.; Wang, X.F.; Zhu, Y.H. Research progress on mineral nutrition and plant disease mechanism. Journal of Gansu Agricultural University 2003, (4), 385–393. [Google Scholar]

- Marschner, H. Marschner’s mineral nutrition of higher plants. Science Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.Q.; Huang, L.P.; Zhang, Z. Research Progress of the Relationship Between Mineral Nutrients Deficiency orImbalance and Plant Disease. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin 2016, 32, 174–176. [Google Scholar]

- Fidanza, M.A.; Dernoeden, P.H. Interaction of nitrogen source, application timing, and fungicide on Rhizoctonia blight in ryegrass. Hortscience A Publication of the American Society for Horticultural Science 1996, 31, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, C.V.; Rao, G.R.; Reddy, K.B. Effect of nitrogen and potassium nutrition on sheath rot incidence and phenol content in rice(Oryz asativa L.). Indian Journal of Plant Physiology 2001, 16, 254–257. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.R.; Kolte, S.J. Effect of soil-applied NPK fertilizers on severity of black spot disease (Alternaria brassicae) and yield of oilseed rape. plant and soil 1994, 167, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; He, P.; Jin, J.Y. Advances in effect of potassium nutrition on plant disease resistance and its mechanism. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science 2006, 12, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, K.G.; Zhao, X.Q.; Li, J.Q.; Liu, X.L. Progressing on the Relation between Mineral Nutrients and Plant Disease. Journal of China Agricultural University 2000, 5, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, W.S.; Sams, C.E.; Kelman, A. Enhancing the natural resistance of plant tissues to postharvest diseases through calcium applications. HortScience 1994, 29, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, D.M.; Jones, J.B. The role of magnesium in plant disease. Plant and soil 2013, 368, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.K.; Singh, R.D. Effect of Nitrogenous Fertilizers and Trace Elements on the Severity of Alternaria Blight of Bottle Gound. Annals of Arid Zone 1992, 31, 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gadi, B.; Jeffrey, G. Copper as a biocidal tool. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2005, 12, 2163–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Sawant, I.S.; Sawant, S.D.; Saha, S.; Kadam, P.; Somkuwar, R.G. Aqueous chlorine dioxide for the management of powdery mildew vis-a-vis maintaining quality of grapes and raisins. Journal of Eco-friendly Agriculture 2017, 12, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ehret, D.L.; Utkhede, R.S.; Frey, B.; Menzies, J.G.; Bogdanoff, C. Foliar applications of fertilizer salts inhibit powdery mildew on tomato. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 2002, 24, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigati, M.; Falciola, L.; Mussini, P.; Beretta, G.; Facino, R.M. Determination of selenium in Italian rices by differential pulse cathodic stripping voltammetry. Food Chemistry 2007, 105, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, K.; Bieri, J.G.; Briggs, G.M.; Scott, M.L. Prevention of Exudative Diathesis in Chicks by Factor 3 and Selenium. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology & Medicine 1957, 95, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.Q.; Yin, Z.F.; Wei, L.H.; Wang, Y.J.; Yang, X.Y. The duality of selenium and its related health issues. Journal of chengde medical college 1999, 1, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Peng, Z.K.; Luo, Z.M. The multiple biological functions of selenium and its impact on human and animal health. Journal of Hunan Agricultural University 1997, 23, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayman, M.P.; Margaret, P. Selenium and human health. The Lancet 2012, 379, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, D.; Raisbeck, M.F. Pathology of experimentally induced chronic selenosis (alkali disease) in yearling cattle. Journal of Veterinary diagnostic investigation 1995, 7, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.X.; Zhou, W.S.; Guo, S.H. Advances of Studies on Microelement Selenium in Plants. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences 2009, 37, 5844–5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A.; Shrift, A. Selenium: toxicity and tolerance in higher plants. Biological Reviews 1982, 57, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, X.F.; Xu, H.S. Functions of Selenium in Plants. Plant Physiology Journal 1999, 35, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H. Selenosis. Chinese Journal of Veterinary Science 1993, 13, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.X.; Zheng, B.S.; Zhao, C.Z.; Yin, C.Q.; Lang, Y.B.; Zhang, A.L. Study on Selenium in Poisonous Oxytropis Plants (Locoweed) from the Hexi Corridor and Its Association with Livestock Poisoning. Advances in Earth Science 2004, 19, 502–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.X.; Zheng, B.S.; Wang, M.S.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, X.J.; Ling, H.W.; Luo, C. Environmental Geochemistry of Selenium in the Hexi Corridor Region and Investigation into the Causes of Livestock Poisoning by Toxic Plants. Acta Mineralogica Sinica 2006, 26, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, F.; Bi, D.; Wang, H.K.; Li, H.Y.; Zhou, S.B.; Zhao, Q.G.; Yin, X.B. Distribution and Speciation of Selenium in Alkaline Soils and Agricultural Products of Lanzhou. Soils 2012, 44, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.J.; Li, H.Y.; Wang, G.Y.; Wang, P. Analysis of Selenium Speciation in Soils and Key Agricultural Products from Lanzhou City. Gansu Science and Technology Information 2016, 45, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, M.; Li, Y.Z. Alternaria gansuense, a Plant Systematic Fungal Pathogen Producing Swainsonine in Vivo and in Vitro. Current Microbiology 2023, 80, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.H.; Zhai, X.H.; Li, Q.F.; Wang, J.H.; Geng, G.X. Determination of Swainsonine in Astragalus locoweed by internal standard gas chromatography. Journal of Northwest Sci-Tech University of Agriculture and Forestry 2008, 36, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Gardner, D.R.; Pfister, J.A. Swainsonine-containing plants and their relationship to endophytic fungi. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2014, 62, 7326–7334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Gardner, D.R.; Lee, S.T.; Pfister, J.A.; Stonecipher, C.A.; Welsh, S.L. A swainsonine survey of North American Astragalus and Oxytropis taxa implicated as locoweeds. Toxicon 2016, 118, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Gardner, D.R.; Ralphs, M.H.; Pfister, J.A.; Welch, K.D.; Green, B.T. Swainsoninine concentrations and endophyte amounts of Undifilum oxytropis in different plant parts of Oxytropis sericea. Journal of chemical ecology 2009, 35, 1272–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; He, B.X. A study on the toxicity of Oxytropis kansuonisis in sheep. Chinese Journal of Veterinary Medicine 1995, 21, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Mo, C.H.; Zhao, B.Y.; Cao, G.R. Study on the Toxicity of Intermittent Feeding of Oxytropis kansuensis to Sheep. Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Medicine 1998, 30, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, B.Q.; Xue, D.M.; Cao, G.R.; Duan, D.X. Pathological Observations of Oxytropis kansuensis Poisoning in Goats. Journal of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine 1991, 3, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.F.; Wang, J.H.; Yuan, Y.; Qi, X.R.; Zhao, Y. Pathology of Oxytropis glacialis Poisoning in Goats. Chinese Journal of Veterinary Science 2001, 21, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Nan, Z.B.; Li, Y.Z. Toxicity of standing milkvetch infected with Alternaria gansuense in white mice. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2025, 11, 1477970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).