Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Materials (INCI Nomenclature)

2.2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Development of the Emulsion

3.1.1. In Vitro Emulsion Evaluation on Gelatin Support Cells [23]

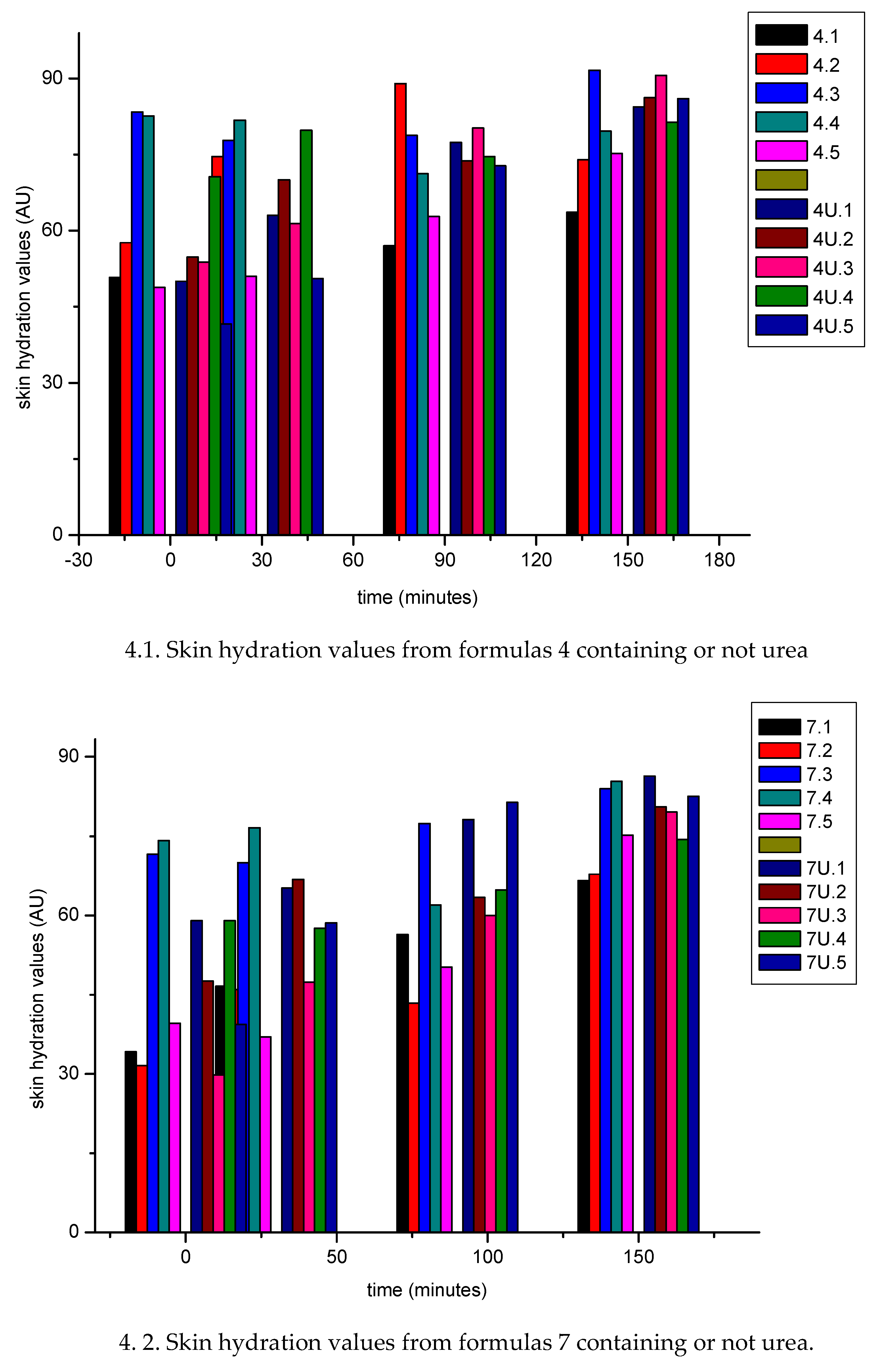

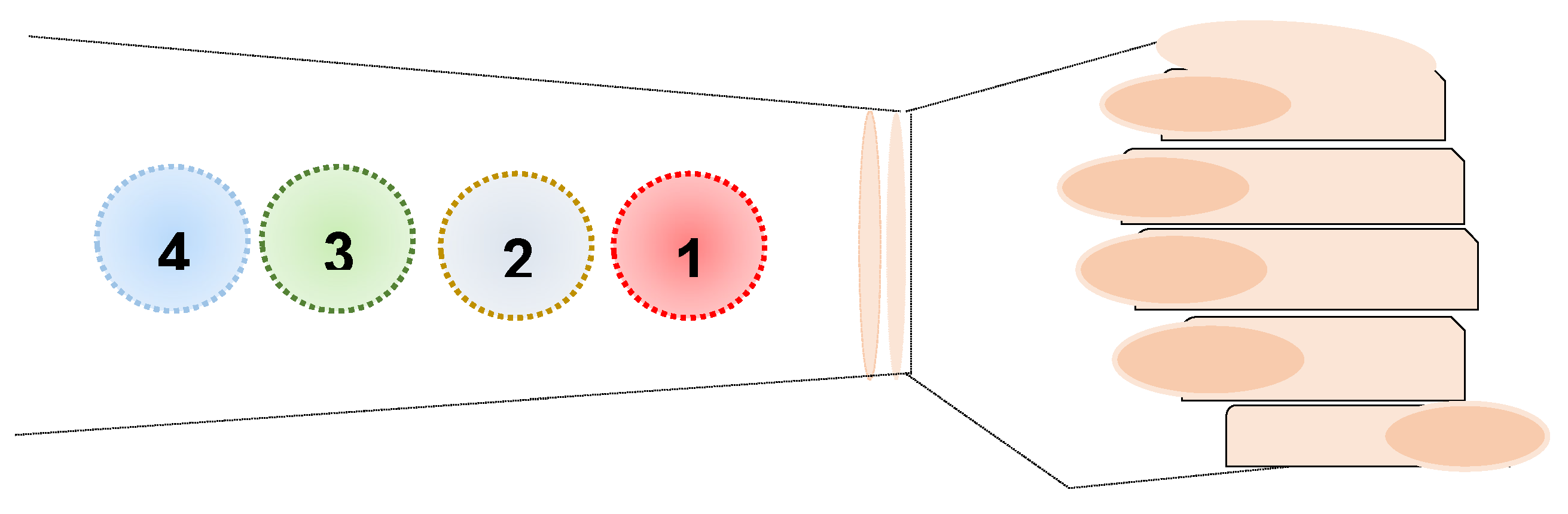

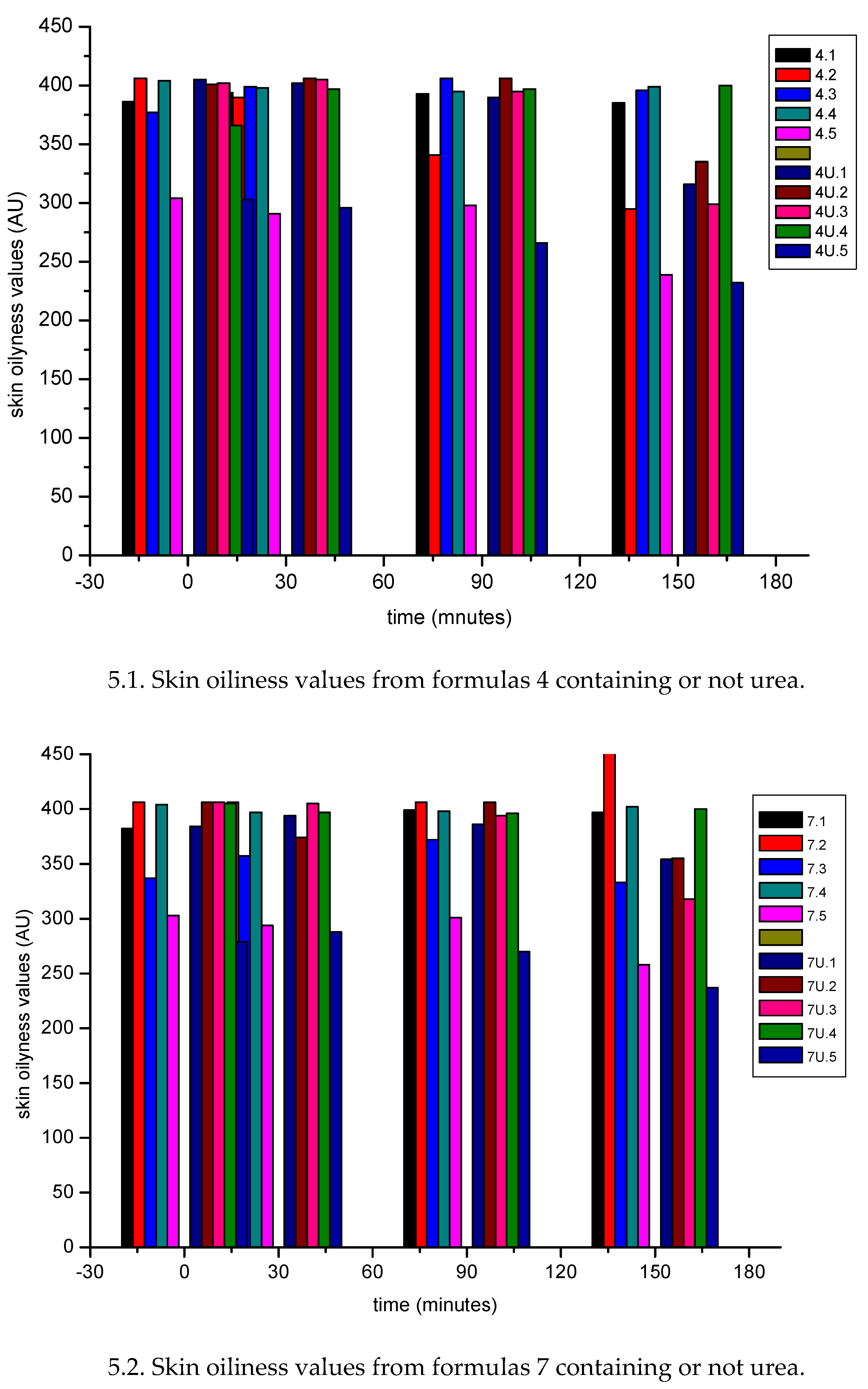

3.1.2. In Vivo Emulsion Evaluation- Skin Application

4. Conclusion

Ethical Aspects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lim, K.-M. (2021). Skin Epidermis and Barrier Function. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(6), 3035. [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, J. R., Chandan, N., Lio, P., & Shi, V. Y. (2023). The skin barrier and moisturization: function, disruption, and mechanisms of repair. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology, 36(4), 174-185. [CrossRef]

- Sparr, E, Björklund, S, DatPham, Q, Mojumdar, EH, Stenqvist, Gunnarsson, BM, Topgaard, D. (2023). The stratum corneum barrier - From molecular scale to macroscopic Properties. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 67(10) 101725. [CrossRef]

- Asada, N., Morita, R., Kamiji, R., Kuwajima, M., Komorisono, M., Yamamura, T. & Yoshikawa, S. (2022). Evaluation of intercellular lipid lamellae in the stratum corneum by polarized microscopy. Skin Research and Technology, 28(3), 391-401. [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, O. K. (1959). Moisture regulation in the skin. Drug Cosmet Ind, 84(6), 732-3.

- Fowler, J. (2012). Understanding the role of natural moisturizing factor in skin hydration. Pract. Dermatol, 9, 36-40.

- Norlén L. Skin barrier structure and function: the single gel phase model. J Invest Dermatol. 2001 Oct;117(4):830-6. [CrossRef]

- Lacarrubba, F., Nasca, M. R., Puglisi, D. F., & Micali, G. (2020). Clinical evidences of urea at low concentration. International journal of clinical practice, 74, e13626. [CrossRef]

- Celleno L. Topical urea in skincare: A review. Dermatol Ther. 2018 Nov;31(6). [CrossRef]

- Piquero-Casals, J., Morgado-Carrasco, D., Granger, C. et al. Urea in Dermatology: A Review of its Emollient, Moisturizing, Keratolytic, Skin Barrier Enhancing and Antimicrobial Properties. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 11, 1905–1915 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Berardesca, E., & Cameli, N. (2020). Non-invasive assessment of urea efficacy: A review. International Journal of Clinical Practice,74. [CrossRef]

- 12. Iwai H, Fukasawa J, Suzuki T. (1998). A liquid crystal application in skin care cosmetics. Int J Cosmet Sci. Apr;20(2):87-102. [CrossRef]

- Morais J.M., Rocha-Filho P.A., Burguess D.J. (2009) Influence of phase inversion on the formation and stability of one-step multiple emulsions. Langmuir. 25:7954–7961. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M., Bishsoi, R.S., Shukla, A.K., Jain, C.P. (2019) Techniques for Formulation of Nanoemulsion Drug Delivery System: A Review. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci., 24 (3) 225- 234. Published online 2019 Sep 30. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari M., Monteiro L.C.L., Netz D.J.A., Rocha-Filho P.A. (2003) Identifying cosmetic forms and crystalline phases from ternary systems. Cosmet. Toilet. ;118: 61–70.

- Tyle P. Liquid crystals and their applications in drug delivery. In: Rosoff M., editor. Controlled Release of Drugs: Polymers and Aggregate Systems. Volume 4. VCH; New York, NY, USA: 1989. pp. 125–162.

- Andrade F.F., Santos O.D.H., Oliveira W.P., Rocha-Filho P.A. (2008); Influence of PEG-12 Dimethicone addition on stability and formation of emulsion containing liquid crystal. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 29:211218. https://. [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (2004). Guia de estabilidade de produtos cosméticos. Séries Temáticas. Série Qualidade 1., 1, Brasília, DF.

- Davis, HM. Analysis of creams and lotions. In: Senzel, AJ. Newburger’s manual of cosmetic analysis. Washington: Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 1997, cap.4, p. 32.

- Braconi F.L., Oliveira I.S., Baroni M.N.F., Rocha-Filho P.A. Aplicação cosmética do óleo de canola; Proceedings of XII Congresso Latino Americano e Ibérico de Químicos Cosméticos; São Paulo, Brazil. 27–31 August 1995; São Paulo, Brazil: Associação Brasileira de Cosmetologia, Tecnopress; 1995. pp. 6–19. ANAIS.

- Ribeiro A.M., Khury E., Gottardi D. Validação de testes de estabilidade para produtos cosméticos; Proceedings of the 12th Congresso Nacional de Cosmetologia; São Paulo, Brazil. 30 June–2 July 1998; São Paulo, Brazil: Associação Brasileira de Cosmetologia, ANAIS Tecnopress; 1998. pp. 349–375.

- Ferrari M. Obtenção e Aplicação de Emulsões Múltiplas Contendo óleos de Andiroba e Copaíba. (Mestrado em Ciências Farmacêuticas) Dissertação, Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo; Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil: 1998. p. 147.

- Rocha-Filho P.A., (1997). Occlusive power evaluation of O/W/O multiples emulsions on gelatin support cells. Int. J. Cosm. Science., 19, 65-73. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Rocha-Filho & M. Maruno (2023) O/W/O multiple emulsions containing soluble collagen: in vitro and in vivo skin biophysical properties evaluation, J Disp Sci Technology. [CrossRef]

- Teeranachaideekul, V., Soontaranon, S., Sukhasem, S. et al. (2023). Influence of the emulsifier on nanostructure and clinical application of liquid crystalline emulsions. Sci Rep. 13, 4185. [CrossRef]

- Santos, ODH; Rocha- Filho, PA. (2008). Influence of Surfactant on the Thermal Behavior of Marigold Oil Emulsions with Liquid Crystal Phases. J Drug Dev Pharmacy, 33 (5) 543- 549. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Li J, Shang Y, Zeng X. (2018). Study on the development of wax emulsion with liquid crystal structure and its moisturizing and frictional interactions with skin. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. Nov 1;171: 335-342. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, H., Usugi, T., Kawano, J., Ishida, A., Hayashi, S. Effect of Occlusivity of oil Film by the States of oil Film on the Skin Surface. J. Soc. Cosm. Chem., 1979,13 (2) 37-43. [CrossRef]

- Imokawa, G., Kuno, H., Kawai, M. (1991). Stratum Corneum Lipids Serve as a Bound-Water Modulator. J. Invest. Dermatology. 96 (6) 845- 851. [CrossRef]

| Sample nr | water (% w/w) |

oil (% w/w) |

surfactant (% w/w) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 60.0 | 30.0 | 10.0 |

| 7 | 50.0 | 40.0 | 10.0 |

| 14 | 40.0 | 20.0 | 40.0 |

| 37 | 45.0 | 20.0 | 35.0 |

| 58 | 25.0 | 20.0 | 55.0 |

| 82 | 60.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Sample nr↓ |

pH value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without urea | With urea | difference | |

| 4 | 6.64 | 7.27 | 0.63 |

| 7 | 6.36 | 6.70 | 0.34 |

| 14 | 6.79 | 7.63 | 0.84 |

| 37 | 6.33 | 6.57 | 0.24 |

| 58 | 6.37 | - | - |

| 82 | 5.91 | 7.37 | 1.46 |

|

Formula nr ↓ |

Before (B) |

After (A) application 300± 4mg |

angular coefficient difference (B- A) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0.99774 | 0.99677 | 0.0009 |

| 4U | 0.99892 | 0.97555 | 0.0233 |

| 7 | 0.99990 | 0.99981 | 0.0009 |

| 7U | 0.99866 | 0.99327 | 0.0053 |

| 14 | 0.99753 | 0.99981 | -0.0022 |

| 14U | 0.99158 | 0.99778 | -0.0062 |

| 37 | 0.99999 | 0.99961 | 0.0004 |

| 37U | 0.99792 | 0.99950 | 0.0015 |

| 82 | 0.99958 | 0.99986 | -0.0002 |

| 82U | 0.99585 | 0.99924 | 0.0033 |

| Sample nr | Occlusive power (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ↓ | Without urea (C) | With urea (D) | Difference (D-C) |

| 4 | 26.85 | 77.57 | 50.72 |

| 7 | 31.49 | 57.77 | 26.28 |

| 14 | 3.81 | 23.85 | 20.04 |

| 37 | 14.94 | 18.38 | 3.44 |

| 82 | 25.11 | 43.40 | 18.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).