Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

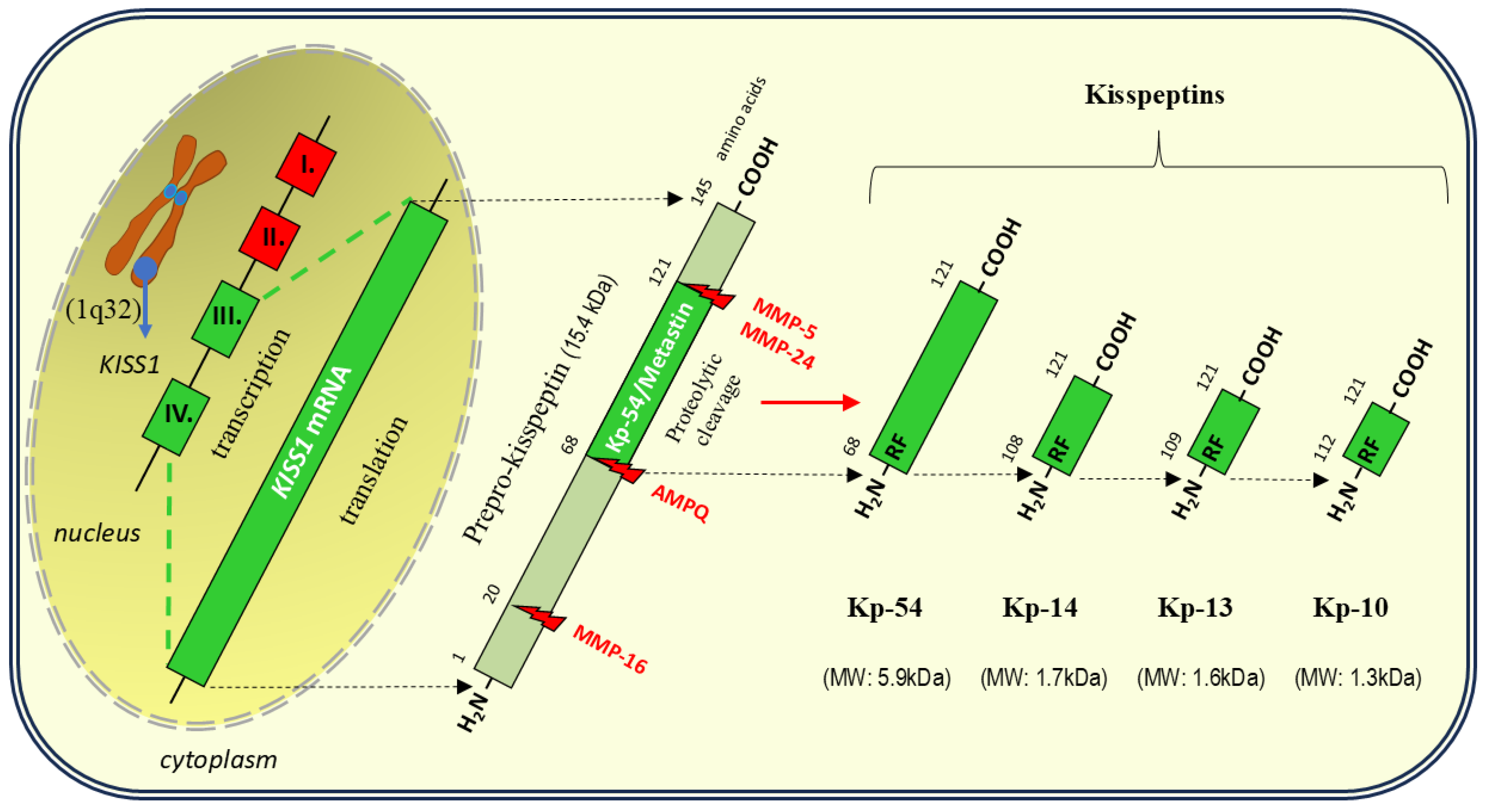

2. Kisspeptin

2.1. Structure

2.2. Sources of Kisspeptin in the Body

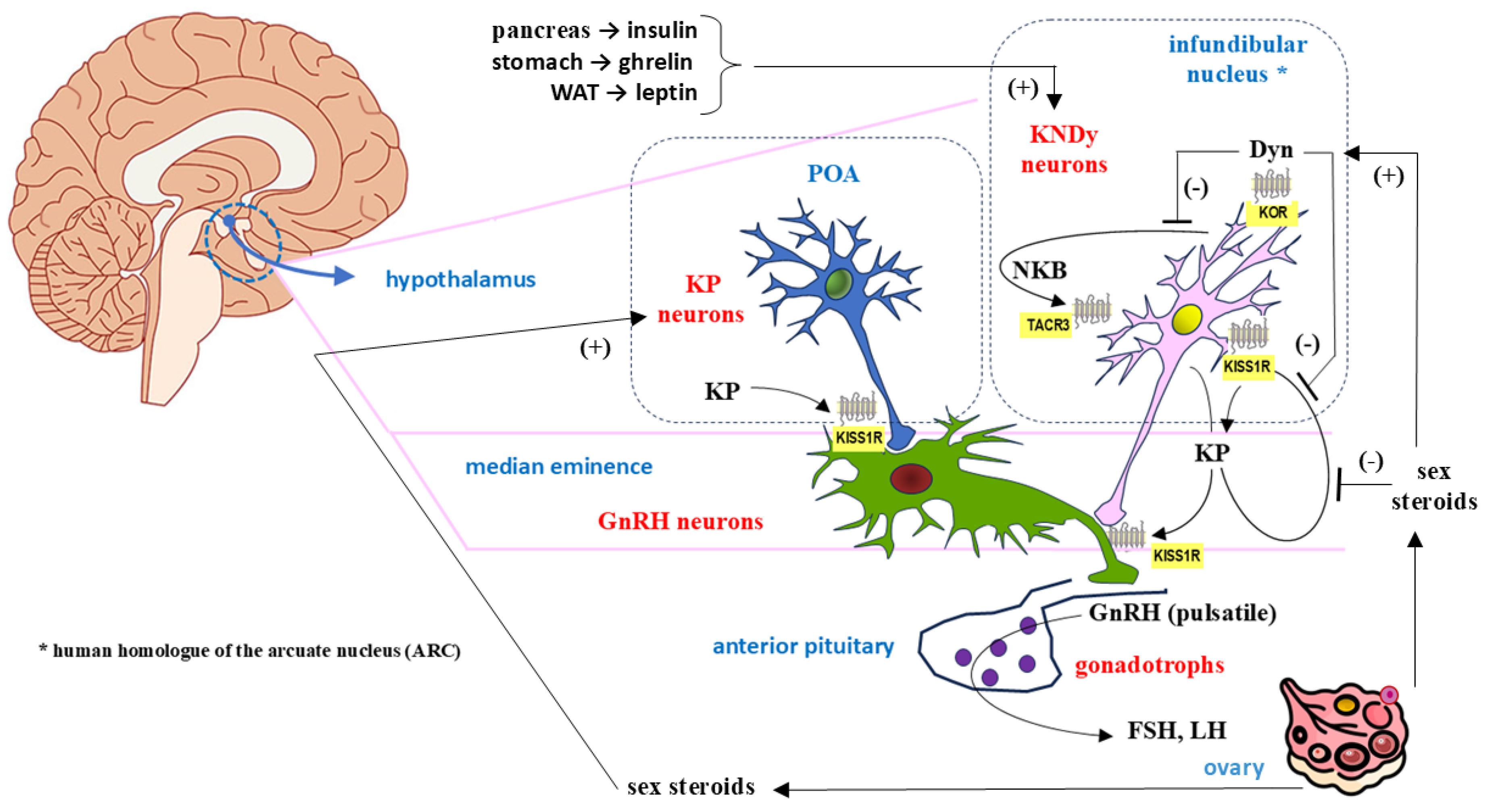

2.2.1. Neuronal Kisspeptin in the Central Nervous System (CNS)

2.2.2. Kisspeptin, Neurokinin B, and Dynorphin (KNDy) Neurons

2.2.3. Extraneuronal Sources of Kisspeptin

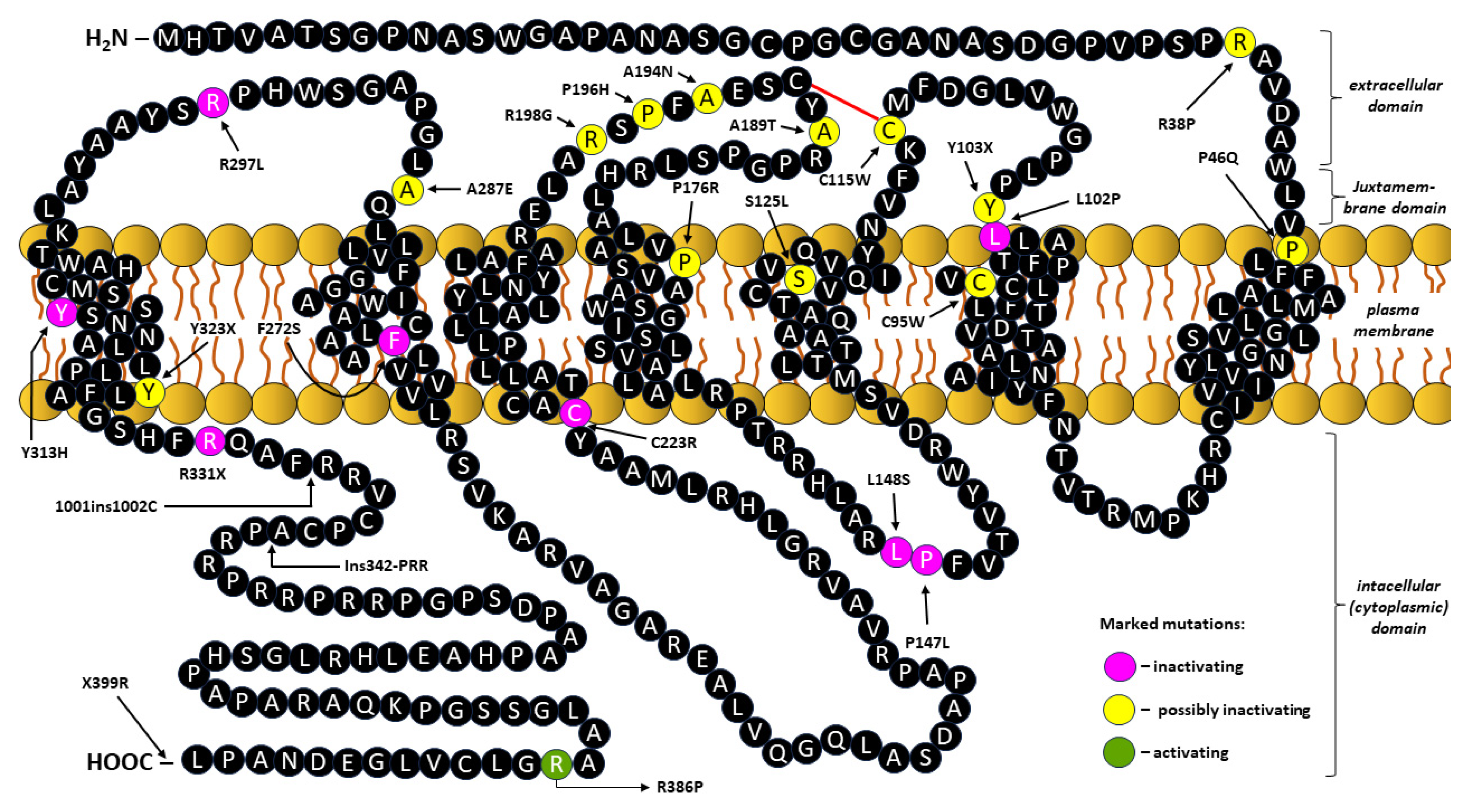

3. Kisspeptin Receptor (KISS1R/GPR54)

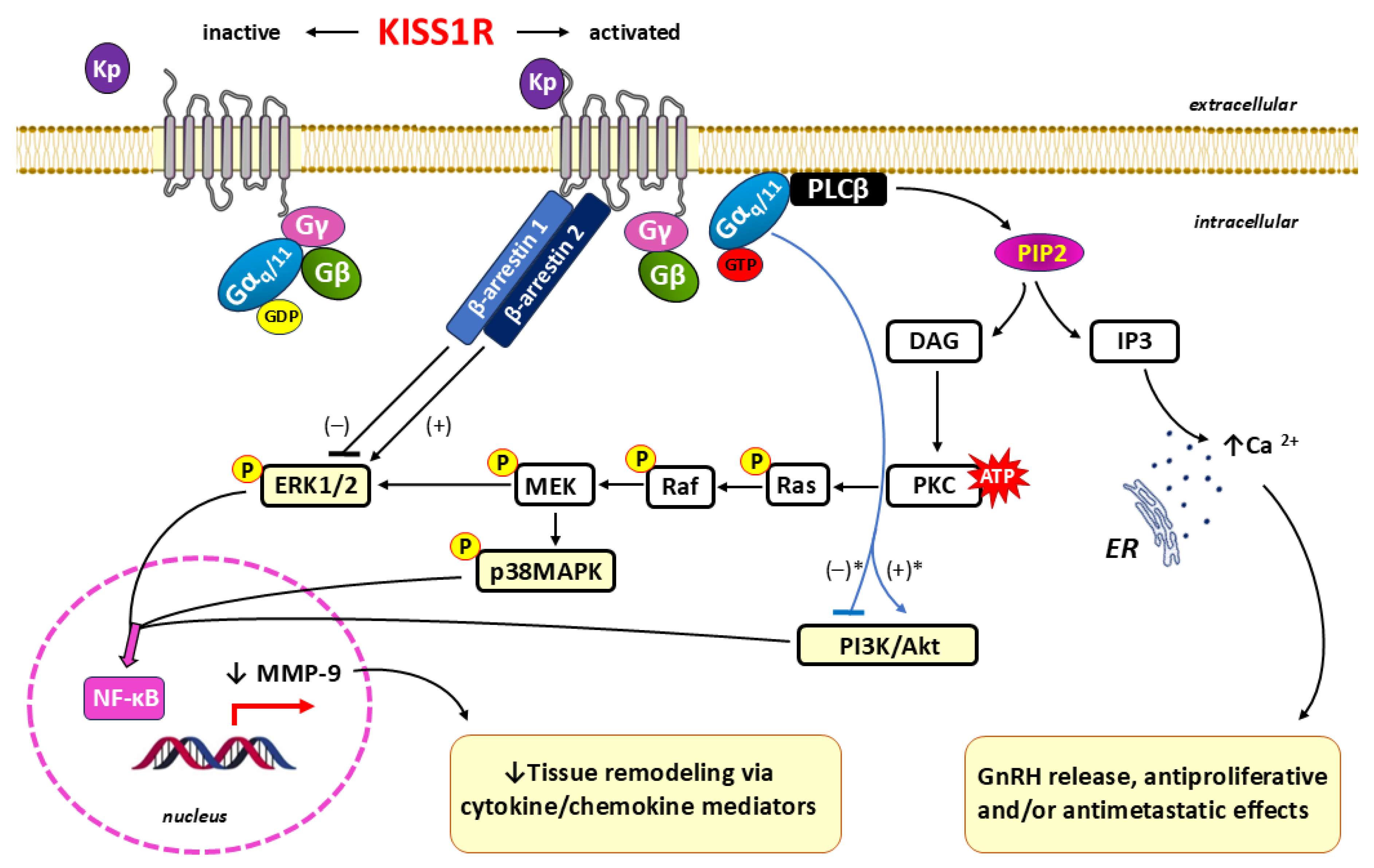

3.1. Kisspeptin/KISS1R Signaling

4. Kisspeptin in Early Pregnancy

4.1. Embryo Implantation

4.2. Trophoblast Invasion–Vascular Remodeling–Placentation

5. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Dufour S, Quérat B, Tostivint H, Pasqualini C, Vaudry H, Rousseau K. Origin and Evolution of the Neuroendocrine Control of Reproduction in Vertebrates, With Special Focus on Genome and Gene Duplications. Physiol Rev. 2020;100(2):869-943. [CrossRef]

- Pillerová M, Borbélyová V, Hodosy J, Riljak V, Renczés E, Frick KM, Tóthová Ľ. On the role of sex steroids in biological functions by classical and non-classical pathways. An update. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2021;62:100926. [CrossRef]

- Colldén H, Nilsson ME, Norlén AK, Landin A, Windahl SH, Wu J, Gustafsson KL, Poutanen M, Ryberg H, Vandenput L, Ohlsson C. Comprehensive Sex Steroid Profiling in Multiple Tissues Reveals Novel Insights in Sex Steroid Distribution in Male Mice. Endocrinology. 2022;163(3):bqac001. [CrossRef]

- Chatuphonprasert W, Jarukamjorn K, Ellinger I. Physiology and Pathophysiology of Steroid Biosynthesis, Transport and Metabolism in the Human Placenta. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1027. [CrossRef]

- Goodman RL, Herbison AE, Lehman MN, Navarro VM. Neuroendocrine control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone: Pulsatile and surge modes of secretion. J Neuroendocrinol. 2022;34(5):e13094. [CrossRef]

- Filicori, M. Pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone: clinical applications of a physiologic paradigm. F S Rep. 2023;4(2 Suppl):20-26. [CrossRef]

- Garg D, Berga SL. Neuroendocrine mechanisms of reproduction. Handb Clin Neurol. 2020;171:3-23. [CrossRef]

- Koysombat K, Dhillo WS, Abbara A. Assessing hypothalamic pituitary gonadal function in reproductive disorders. Clin Sci (Lond). 2023;137(11):863-879. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui K, Bentley GE, Kriegsfeld LJ, Osugi T, Seong JY, Vaudry H. Discovery and evolutionary history of gonadotrophin-inhibitory hormone and kisspeptin: new key neuropeptides controlling reproduction. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22(7):716-27. [CrossRef]

- Dhillo, W. Timeline: kisspeptins. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1(1):12-3. [CrossRef]

- Ohtaki T, Shintani Y, Honda S, Matsumoto H, Hori A, Kanehashi K, Terao Y, Kumano S, Takatsu Y, Masuda Y, Ishibashi Y, Watanabe T, Asada M, Yamada T, Suenaga M, Kitada C, Usuki S, Kurokawa T, Onda H, Nishimura O, Fujino M. Metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes peptide ligand of a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2001;411(6837):613-7. [CrossRef]

- Stafford LJ, Xia C, Ma W, Cai Y, Liu M. Identification and characterization of mouse metastasis-suppressor KiSS1 and its G-protein-coupled receptor. Cancer Res. 2002;62(19):5399-404.

- Makri A, Pissimissis N, Lembessis P, Polychronakos C, Koutsilieris M. The kisspeptin (KiSS-1)/GPR54 system in cancer biology. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34(8):682-92. [CrossRef]

- Rhie, YJ. Kisspeptin/G protein-coupled receptor-54 system as an essential gatekeeper of pubertal development. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2013;18(2):55-9. [CrossRef]

- Joy KP, Chaube R. Kisspeptin control of hypothalamus-pituitary-ovarian functions. Vitam Horm. 2025;127:153-206. [CrossRef]

- Sobrino V, Avendaño MS, Perdices-López C, Jimenez-Puyer M, Tena-Sempere M. Kisspeptins and the neuroendocrine control of reproduction: Recent progress and new frontiers in kisspeptin research. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2022;65:100977. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Rodriguez A, Kauffman AS, Cherrington BD, Borges CS, Roepke TA, Laconi M. Emerging insights into hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis regulation and interaction with stress signalling. J Neuroendocrinol. 2018;30(10):e12590. [CrossRef]

- Koysombat K, Tsoutsouki J, Patel AH, Comninos AN, Dhillo WS, Abbara A. Kisspeptin and neurokinin B: roles in reproductive health. Physiol Rev. 2025;105(2):707-764. [CrossRef]

- Radovick S, Babwah AV. Regulation of Pregnancy: Evidence for Major Roles by the Uterine and Placental Kisspeptin/KISS1R Signaling Systems. Semin Reprod Med. 2019;37(4):182-190. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Li Z, Jiang W, Ling Y, Kuang H. Reproductive functions of Kisspeptin/KISS1R Systems in the Periphery. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2019;17(1):65. [CrossRef]

- Hu KL, Chang HM, Zhao HC, Yu Y, Li R, Qiao J. Potential roles for the kisspeptin/kisspeptin receptor system in implantation and placentation. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25(3):326-343. [CrossRef]

- D'Occhio MJ, Campanile G, Baruselli PS. Peripheral action of kisspeptin at reproductive tissues-role in ovarian function and embryo implantation and relevance to assisted reproductive technology in livestock: a review. Biol Reprod. 2020;103(6):1157-1170. [CrossRef]

- Panting EN, Weight JH, Sartori JA, Coall DA, Smith JT. The role of placental kisspeptin in trophoblast invasion and migration: an assessment in Kiss1r knockout mice, BeWo cell lines and human term placenta. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2024; 36:RD23230. [CrossRef]

- Szydełko-Gorzkowicz M, Poniedziałek-Czajkowska E, Mierzyński R, Sotowski M, Leszczyńska-Gorzelak B. The Role of Kisspeptin in the Pathogenesis of Pregnancy Complications: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(12):6611. [CrossRef]

- Musa E, Salazar-Petres E, Vatish M, Levitt N, Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Matjila MJ. Kisspeptin signalling and its correlation with placental ultrastructure and clinical outcomes in pregnant South African women with obesity and gestational diabetes. Placenta. 2024;154:49-59. [CrossRef]

- López-Ojeda W, Hurley RA. Kisspeptin in the Limbic System: New Insights Into Its Neuromodulatory Roles. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022;34(3):190-195. [CrossRef]

- Pinilla L, Aguilar E, Dieguez C, Millar RP, Tena-Sempere M. Kisspeptins and reproduction: physiological roles and regulatory mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2012; 92(3):1235-316. [CrossRef]

- Tena-Sempere, M. GPR54 and kisspeptin in reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2006; 12(5):631-9. [CrossRef]

- Hu KL, Chen Z, Li X, Cai E, Yang H, Chen Y, Wang C, Ju L, Deng W, Mu L. Advances in clinical applications of kisspeptin-GnRH pathway in female reproduction. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2022;20(1):81. [CrossRef]

- Ke R, Ma X, Lee LTO. Understanding the functions of kisspeptin and kisspeptin receptor (Kiss1R) from clinical case studies. Peptides. 2019;120:170019. [CrossRef]

- Silveira LG, Noel SD, Silveira-Neto AP, Abreu AP, Brito VN, Santos MG, Bianco SD, Kuohung W, Xu S, Gryngarten M, Escobar ME, Arnhold IJ, Mendonca BB, Kaiser UB, Latronico AC. Mutations of the KISS1 gene in disorders of puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(5):2276-80. [CrossRef]

- Gorkem U, Kan O, Bostanci MO, Taskiran D, Inal HA. Kisspeptin and Hematologic Parameters as Predictive Biomarkers for First-Trimester Abortions. Medeni Med J. 2021;36(2):98-105. [CrossRef]

- Horikoshi Y, Matsumoto H, Takatsu Y, Ohtaki T, Kitada C, Usuki S, Fujino M. Dramatic elevation of plasma metastin concentrations in human pregnancy: metastin as a novel placenta-derived hormone in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(2):914-9. [CrossRef]

- Cetković A, Miljic D, Ljubić A, Patterson M, Ghatei M, Stamenković J, Nikolic-Djurovic M, Pekic S, Doknic M, Glišić A, Bloom S, Popovic V. Plasma kisspeptin levels in pregnancies with diabetes and hypertensive disease as a potential marker of placental dysfunction and adverse perinatal outcome. Endocr Res. 2012;37(2):78-88. [CrossRef]

- d'Anglemont de Tassigny X, Jayasena CN, Murphy KG, Dhillo WS, Colledge WH. Mechanistic insights into the more potent effect of KP-54 compared to KP-10 in vivo. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176821. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2018; 13(1):e0192014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192014. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Moenter SM. Differential Roles of Hypothalamic AVPV and Arcuate Kisspeptin Neurons in Estradiol Feedback Regulation of Female Reproduction. Neuroendocrinology. 2020;110(3-4):172-184. [CrossRef]

- Mills EG, Dhillo WS. Invited review: Translating kisspeptin and neurokinin B biology into new therapies for reproductive health. J Neuroendocrinol. 2022;34(10):e13201. [CrossRef]

- Gottsch ML, Cunningham MJ, Smith JT, Popa SM, Acohido BV, Crowley WF, Seminara S, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. A role for kisspeptins in the regulation of gonadotropin secretion in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2004;145(9):4073-7. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson J, d'Anglemont de Tassigny X, Colledge WH, Caraty A, Herbison AE. Distribution of kisspeptin neurones in the adult female mouse brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21(8):673-82. [CrossRef]

- Semaan SJ, Kauffman AS. Developmental sex differences in the peri-pubertal pattern of hypothalamic reproductive gene expression, including Kiss1 and Tac2, may contribute to sex differences in puberty onset. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2022;551:111654. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz de la Torre LP, Trujillo Hernández A, Eguibar JR, Cortés C, Morales-Ledesma L. Sex-specific hypothalamic expression of kisspeptin, gonadotropin releasing hormone, and kisspeptin receptor in progressive demyelination model. J Chem Neuroanat. 2022;123:102120. [CrossRef]

- Shibata M, Friedman RL, Ramaswamy S, Plant TM. Evidence that down regulation of hypothalamic KiSS-1 expression is involved in the negative feedback action of testosterone to regulate luteinising hormone secretion in the adult male rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19(6):432-8. [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy S, Guerriero KA, Gibbs RB, Plant TM. Structural interactions between kisspeptin and GnRH neurons in the mediobasal hypothalamus of the male rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) as revealed by double immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. Endocrinology. 2008;149(9):4387-95. [CrossRef]

- Smith JT, Shahab M, Pereira A, Pau KY, Clarke IJ. Hypothalamic expression of KISS1 and gonadotropin inhibitory hormone genes during the menstrual cycle of a non-human primate. Biol Reprod. 2010;83(4):568-77. [CrossRef]

- Rometo AM, Krajewski SJ, Voytko ML, Rance NE. Hypertrophy and increased kisspeptin gene expression in the hypothalamic infundibular nucleus of postmenopausal women and ovariectomized monkeys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007; 92(7):2744-50. [CrossRef]

- Hrabovszky E, Ciofi P, Vida B, Horvath MC, Keller E, Caraty A, Bloom SR, Ghatei MA, Dhillo WS, Liposits Z, Kallo I. The kisspeptin system of the human hypothalamus: sexual dimorphism and relationship with gonadotropin-releasing hormone and neurokinin B neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31(11):1984-98. [CrossRef]

- Moore AM, Coolen LM, Porter DT, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. KNDy Cells Revisited. Endocrinology. 2018;159(9):3219-3234. [CrossRef]

- Velasco I, Franssen D, Daza-Dueñas S, Skrapits K, Takács S, Torres E, Rodríguez-Vazquez E, Ruiz-Cruz M, León S, Kukoricza K, Zhang FP, Ruohonen S, Luque-Cordoba D, Priego-Capote F, Gaytan F, Ruiz-Pino F, Hrabovszky E, Poutanen M, Vázquez MJ, Tena-Sempere M. Dissecting the KNDy hypothesis: KNDy neuron-derived kisspeptins are dispensable for puberty but essential for preserved female fertility and gonadotropin pulsatility. Metabolism. 2023;144:155556. [CrossRef]

- Beltramo M, Robert V, Decourt C. The kisspeptin system in domestic animals: what we know and what we still need to understand of its role in reproduction. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2020;73:106466. [CrossRef]

- Xie Q, Kang Y, Zhang C, Xie Y, Wang C, Liu J, Yu C, Zhao H, Huang D. The Role of Kisspeptin in the Control of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis and Reproduction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:925206. [CrossRef]

- Uenoyama Y, Nagae M, Tsuchida H, Inoue N, Tsukamura H. Role of KNDy Neurons Expressing Kisspeptin, Neurokinin B, and Dynorphin A as a GnRH Pulse Generator Controlling Mammalian Reproduction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12: 724632. [CrossRef]

- Oride A, Kanasaki H. The role of KNDy neurons in human reproductive health. Endocr J. 2024;71(8):733-743. [CrossRef]

- Moore AM, Novak AG, Lehman MN. KNDy Neurons of the Hypothalamus and Their Role in GnRH Pulse Generation: an Update. Endocrinology. 2023 Dec;165(2): bqad194. [CrossRef]

- Hrabovszky E, Sipos MT, Molnár CS, Ciofi P, Borsay BÁ, Gergely P, Herczeg L, Bloom SR, Ghatei MA, Dhillo WS, Liposits Z. Low degree of overlap between kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin immunoreactivities in the infundibular nucleus of young male human subjects challenges the KNDy neuron concept. Endocrinology. 2012;153(10):4978-89. [CrossRef]

- Lehman MN, He W, Coolen LM, Levine JE, Goodman RL. Does the KNDy Model for the Control of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Pulses Apply to Monkeys and Humans? Semin Reprod Med. 2019;37(2):71-83. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, VM. Metabolic regulation of kisspeptin - the link between energy balance and reproduction. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(8):407-420. [CrossRef]

- Nandankar N, Negrón AL, Wolfe A, Levine JE, Radovick S. Deficiency of arcuate nucleus kisspeptin results in postpubertal central hypogonadism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2021;321(2):E264-E280. [CrossRef]

- Campideli-Santana AC, Gusmao DO, Almeida FRCL, Araujo-Lopes R, Szawka RE. Partial loss of arcuate kisspeptin neurons in female rats stimulates luteinizing hormone and decreases prolactin secretion induced by estradiol. J Neuroendocrinol. 2022; 34(11):e13204. [CrossRef]

- Szukiewicz, D. Current Insights in Prolactin Signaling and Ovulatory Function. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(4):1976. [CrossRef]

- Torres E, Pellegrino G, Granados-Rodríguez M, Fuentes-Fayos AC, Velasco I, Coutteau-Robles A, Legrand A, Shanabrough M, Perdices-Lopez C, Leon S, Yeo SH, Manchishi SM, Sánchez-Tapia MJ, Navarro VM, Pineda R, Roa J, Naftolin F, Argente J, Luque RM, Chowen JA, Horvath TL, Prevot V, Sharif A, Colledge WH, Tena-Sempere M, Romero-Ruiz A. Kisspeptin signaling in astrocytes modulates the reproductive axis. J Clin Invest. 2024;134(15):e172908. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Liu Q, Huang G, Wen J, Chen G. Hypothalamic Kisspeptin Neurons Regulates Energy Metabolism and Reproduction Under Chronic Stress. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:844397. [CrossRef]

- Harter CJL, Kavanagh GS, Smith JT. The role of kisspeptin neurons in reproduction and metabolism. J Endocrinol. 2018;238(3):R173-R183. [CrossRef]

- Patel R, Smith JT. Novel actions of kisspeptin signaling outside of GnRH-mediated fertility: a potential role in energy balance. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2020;73: 106467. [CrossRef]

- Oyedokun PA, Akangbe MA, Akhigbe TM, Akhigbe RE. Regulatory Involvement of Kisspeptin in Energy Balance and Reproduction. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2025;83(1): 247-261. [CrossRef]

- Dhillo WS, Murphy KG, Bloom SR. The neuroendocrine physiology of kisspeptin in the human. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2007;8(1):41-6. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya M, Babwah AV. Kisspeptin: beyond the brain. Endocrinology. 2015; 156(4):1218-27. [CrossRef]

- Hu KL, Zhao H, Yu Y, Li R. Kisspeptin as a potential biomarker throughout pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;240:261-266. [CrossRef]

- Dhillo WS, Savage P, Murphy KG, Chaudhri OB, Patterson M, Nijher GM, Foggo VM, Dancey GS, Mitchell H, Seckl MJ, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Plasma kisspeptin is raised in patients with gestational trophoblastic neoplasia and falls during treatment. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291(5):E878-84. [CrossRef]

- Tsoutsouki J, Patel B, Comninos AN, Dhillo WS, Abbara A. Kisspeptin in the Prediction of Pregnancy Complications. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13: 942664. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Yuan L, Han S, Xuan M, Liu D, Tian B, Yu W. Reduced Kiss-1 expression is associated with clinical aggressive feature of gastric cancer patients and promotes migration and invasion in gastric cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2020;44(3):1149-1157. [CrossRef]

- Wu HM, Chen LH, Chiu WJ, Tsai CL. Kisspeptin Regulates Cell Invasion and Migration in Endometrial Cancer. J Endocr Soc. 2024;8(3):bvae001. [CrossRef]

- Loosen SH, Luedde M, Lurje G, Spehlmann M, Paffenholz P, Ulmer TF, Tacke F, Vucur M, Trautwein C, Neumann UP, Luedde T, Roderburg C. Serum Levels of Kisspeptin Are Elevated in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. Dis Markers. 2019; 2019:5603474. [CrossRef]

- Kim CW, Lee HK, Nam MW, Choi Y, Choi KC. Overexpression of KiSS1 Induces the Proliferation of Hepatocarcinoma and Increases Metastatic Potential by Increasing Migratory Ability and Angiogenic Capacity. Mol Cells. 2022;45(12):935-949. [CrossRef]

- Zhu N, Zhao M, Song Y, Ding L, Ni Y. The KiSS-1/GPR54 system: Essential roles in physiological homeostasis and cancer biology. Genes Dis. 2020;9(1):28-40. [CrossRef]

- Ulasov IV, Borovjagin AV, Timashev P, Cristofanili M, Welch DR. KISS1 in breast cancer progression and autophagy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019;38(3):493-506. [CrossRef]

- Guzman S, Brackstone M, Wondisford F, Babwah AV, Bhattacharya M. KISS1/KISS1R and Breast Cancer: Metastasis Promoter. Semin Reprod Med. 2019;37(4):197-206. [CrossRef]

- Ly T, Harihar S, Welch DR. KISS1 in metastatic cancer research and treatment: potential and paradoxes. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020;39(3):739-754. [CrossRef]

- Fratangelo F, Carriero MV, Motti ML. Controversial Role of Kisspeptins/KiSS-1R Signaling System in Tumor Development. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:192. [CrossRef]

- Stathaki M, Stamatiou ME, Magioris G, Simantiris S, Syrigos N, Dourakis S, Koutsilieris M, Armakolas A. The role of kisspeptin system in cancer biology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;142:130-140. [CrossRef]

- Hiden U, Bilban M, Knöfler M, Desoye G. Kisspeptins and the placenta: regulation of trophoblast invasion. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2007;8(1):31-9. [CrossRef]

- Santos BR, Dos Anjos Cordeiro JM, Santos LC, Barbosa EM, Mendonça LD, Santos EO, de Macedo IO, de Lavor MSL, Szawka RE, Serakides R, Silva JF. Kisspeptin treatment improves fetal-placental development and blocks placental oxidative damage caused by maternal hypothyroidism in an experimental rat model. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022; 13: 908240. [CrossRef]

- Taylor J, Pampillo M, Bhattacharya M, Babwah AV. Kisspeptin/KISS1R signaling potentiates extravillous trophoblast adhesion to type-I collagen in a PKC- and ERK1/2-dependent manner. Mol Reprod Dev. 2014;81(1):42-54. [CrossRef]

- Cockwell H, Wilkinson DA, Bouzayen R, Imran SA, Brown R, Wilkinson M. KISS1 expression in human female adipose tissue. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287(1):143-7. [CrossRef]

- Dudek M, Kołodziejski PA, Pruszyńska-Oszmałek E, Sassek M, Ziarniak K, Nowak KW, Sliwowska JH. Effects of high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes on Kiss1 and GPR54 expression in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and peripheral organs (fat, pancreas and liver) in male rats. Neuropeptides. 2016;56:41-9. [CrossRef]

- Pruszyńska-Oszmałek E, Wojciechowska M, Krauss H, Sassek M, Leciejewska N, Szczepankiewicz D, Nowak KW, Piątek J, Nogowski L, Sliwowska JH, Kołodziejski PA. Obesity is associated with increased level of kisspeptin in mothers' blood and umbilical cord blood - a pilot study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(19):5993-6002. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe A, Hussain MA. The Emerging Role(s) for Kisspeptin in Metabolism in Mammals. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:184. [CrossRef]

- Sliwowska JH, Woods NE, Alzahrani AR, Paspali E, Tate RJ, Ferro VA. Kisspeptin a potential therapeutic target in treatment of both metabolic and reproductive dysfunction. J Diabetes. 2024;16(4):e13541. [CrossRef]

- Gottsch ML, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. From KISS1 to kisspeptins: An historical perspective and suggested nomenclature. Peptides. 2009;30(1):4-9. [CrossRef]

- Kirby HR, Maguire JJ, Colledge WH, Davenport AP. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXVII. Kisspeptin receptor nomenclature, distribution, and function. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62(4):565-78. [CrossRef]

- Wu Z, Chen G, Qiu C, Yan X, Xu L, Jiang S, Xu J, Han R, Shi T, Liu Y, Gao W, Wang Q, Li J, Ye F, Pan X, Zhang Z, Ning P, Zhang B, Chen J, Du Y. Structural basis for the ligand recognition and G protein subtype selectivity of kisspeptin receptor. Sci Adv. 2024;10(33):eadn7771. [CrossRef]

- Muir AI, Chamberlain L, Elshourbagy NA, Michalovich D, Moore DJ, Calamari A, Szekeres PG, Sarau HM, Chambers JK, Murdock P, Steplewski K, Shabon U, Miller JE, Middleton SE, Darker JG, Larminie CG, Wilson S, Bergsma DJ, Emson P, Faull R, Philpott KL, Harrison DC. AXOR12, a novel human G protein-coupled receptor, activated by the peptide KiSS-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(31):28969-75. [CrossRef]

- Acierno JS Jr, Shagoury JK, Bo-Abbas Y, Crowley WF Jr, Seminara SB. A locus for autosomal recessive idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism on chromosome 19p13.3. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(6):2947-50. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso JC, Félix RC, Bjärnmark N, Power DM. Allatostatin-type A, kisspeptin and galanin GPCRs and putative ligands as candidate regulatory factors of mantle function. Mar Genomics. 2016;27:25-35. [CrossRef]

- Quillet R, Ayachi S, Bihel F, Elhabazi K, Ilien B, Simonin F. RF-amide neuropeptides and their receptors in Mammals: Pharmacological properties, drug development and main physiological functions. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;160:84-132. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa K, Maedomari R, Sato Y, Gotoh K, Kudoh S, Kojima A, Okada S, Ito T. Kiss1R Identification and Biodistribution Analysis Employing a Western Ligand Blot and Ligand-Derivative Stain with a FITC-Kisspeptin Derivative. ChemMedChem. 2020;15(18):1699-1705. Erratum in: ChemMedChem. 2021;16(4):725. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202000990. [CrossRef]

- Pasquier J, Kamech N, Lafont AG, Vaudry H, Rousseau K, Dufour S. Molecular evolution of GPCRs: Kisspeptin/kisspeptin receptors. J Mol Endocrinol. 2014;52(3): T101-17. [CrossRef]

- Kotani M, Detheux M, Vandenbogaerde A, Communi D, Vanderwinden JM, Le Poul E, Brézillon S, Tyldesley R, Suarez-Huerta N, Vandeput F, Blanpain C, Schiffmann SN, Vassart G, Parmentier M. The metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes kisspeptins, the natural ligands of the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR54. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(37):34631-6. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Qin M, Fan L, Gong C. Correlation Analysis of Genotypes and Phenotypes in Chinese Male Pediatric Patients With Congenital Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:846801. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Hu M, Du T, Yang L, Li Y, Feng L, Luo J, Yao H, Chen X. Homozygous mutation of KISS1 receptor (KISS1R) gene identified in a Chinese patient with congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (CHH): case report and literature review. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2024;37(11):999-1008. [CrossRef]

- Geng D, Zhang H, Liu X, Fei J, Jiang Y, Liu R, Wang R, Zhang G. Identification of KISS1R gene mutations in disorders of non-obstructive azoospermia in the northeast population of China. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34(4):e23139. [CrossRef]

- Schöneberg T, Liebscher I. Mutations in G Protein-Coupled Receptors: Mechanisms, Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73(1):89-119. [CrossRef]

- Heydenreich FM, Marti-Solano M, Sandhu M, Kobilka BK, Bouvier M, Babu MM. Molecular determinants of ligand efficacy and potency in GPCR signaling. Science. 2023;382(6677):eadh1859. [CrossRef]

- Roa J, Aguilar E, Dieguez C, Pinilla L, Tena-Sempere M. New frontiers in kisspeptin/GPR54 physiology as fundamental gatekeepers of reproductive function. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29(1):48-69. [CrossRef]

- Abbara A, Clarke SA, Dhillo WS. Clinical Potential of Kisspeptin in Reproductive Health. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(8):807-823. [CrossRef]

- Gianetti E, Seminara S. Kisspeptin and KISS1R: a critical pathway in the reproductive system. Reproduction. 2008;136(3):295-301. [CrossRef]

- Franssen D, Tena-Sempere M. The kisspeptin receptor: A key G-protein-coupled receptor in the control of the reproductive axis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;32(2):107-123. [CrossRef]

- Shen S, Wang D, Liu H, He X, Cao Y, Chen J, Li S, Cheng X, Xu HE, Duan J. Structural basis for hormone recognition and distinctive Gq protein coupling by the kisspeptin receptor. Cell Rep. 2024;43(7):114389. [CrossRef]

- Lyon AM, Tesmer JJ. Structural insights into phospholipase C-β function. Mol Pharmacol. 2013; 84(4):488-500. [CrossRef]

- Kanemaru K, Nakamura Y. Activation Mechanisms and Diverse Functions of Mammalian Phospholipase C. Biomolecules. 2023;13(6):915. [CrossRef]

- Ubeysinghe S, Wijayaratna D, Kankanamge D, Karunarathne A. Molecular regulation of PLCβ signaling. Methods Enzymol. 2023;682:17-52. [CrossRef]

- Paknejad N, Hite RK. Structural basis for the regulation of inositol trisphosphate receptors by Ca2+ and IP3. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25(8):660-668. Erratum in: Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25(9):902. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0119-4. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz EA, Takahashi H, Karakas E. Structural basis for activation and gating of IP3 receptors. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1408. [CrossRef]

- Lučić I, Truebestein L, Leonard TA. Novel Features of DAG-Activated PKC Isozymes Reveal a Conserved 3-D Architecture. J Mol Biol. 2016;428(1):121-141. [CrossRef]

- Kolczynska K, Loza-Valdes A, Hawro I, Sumara G. Diacylglycerol-evoked activation of PKC and PKD isoforms in regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism: a review. Lipids Health Dis. 2020; 19(1):113. [CrossRef]

- Krebs J, Agellon LB, Michalak M. Ca(2+) homeostasis and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress: An integrated view of calcium signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;460(1):114-21. [CrossRef]

- Bagur R, Hajnóczky G. Intracellular Ca2+ Sensing: Its Role in Calcium Homeostasis and Signaling. Mol Cell. 2017;66(6):780-788. [CrossRef]

- Peng J, Tang M, Zhang BP, Zhang P, Zhong T, Zong T, Yang B, Kuang HB. Kisspeptin stimulates progesterone secretion via the Erk1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in rat luteal cells. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1436-1443.e1. [CrossRef]

- Kim GL, Dhillon SS, Belsham DD. Kisspeptin directly regulates neuropeptide Y synthesis and secretion via the ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways in NPY-secreting hypothalamic neurons. Endocrinology. 2010;151(10):5038-47. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Kazanietz MG. Divergence and complexities in DAG signaling: looking beyond PKC. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24(11):602-8. [CrossRef]

- Szereszewski JM, Pampillo M, Ahow MR, Offermanns S, Bhattacharya M, Babwah AV. GPR54 regulates ERK1/2 activity and hypothalamic gene expression in a Gα(q/11) and β-arrestin-dependent manner. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):e12964. [CrossRef]

- Ahow M, Min L, Pampillo M, Nash C, Wen J, Soltis K, Carroll RS, Glidewell-Kenney CA, Mellon PL, Bhattacharya M, Tobet SA, Kaiser UB, Babwah AV. KISS1R signals independently of Gαq/11 and triggers LH secretion via the β-arrestin pathway in the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2014; 155(11):4433-46. [CrossRef]

- Pampillo M, Camuso N, Taylor JE, Szereszewski JM, Ahow MR, Zajac M, Millar RP, Bhattacharya M, Babwah AV. Regulation of GPR54 signaling by GRK2 and {beta}-arrestin. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(12):2060-74. [CrossRef]

- Kahsai AW, Shah KS, Shim PJ, Lee MA, Shreiber BN, Schwalb AM, Zhang X, Kwon HY, Huang LY, Soderblom EJ, Ahn S, Lefkowitz RJ. Signal transduction at GPCRs: Allosteric activation of the ERK MAPK by β-arrestin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(43):e2303794120. [CrossRef]

- Hu KL, Zhao H, Chang HM, Yu Y, Qiao J. Kisspeptin/Kisspeptin Receptor System in the Ovary. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;8:365. [CrossRef]

- Gan DM, Zhang PP, Zhang JP, Ding SX, Fang J, Liu Y. KISS1/KISS1R mediates Sertoli cell apoptosis via the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway in a high-glucose environment. Mol Med Rep. 2021; 23(6):477. [CrossRef]

- Yabluchanskiy A, Ma Y, Iyer RP, Hall ME, Lindsey ML. Matrix metalloproteinase-9: Many shades of function in cardiovascular disease. Physiology (Bethesda). 2013;28(6):391-403. [CrossRef]

- Wahab F, Atika B, Shahab M, Behr R. Kisspeptin signalling in the physiology and pathophysiology of the urogenital system. Nat Rev Urol. 2016;13(1):21-32. [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Fabián S, Arreola R, Becerril-Villanueva E, Torres-Romero JC, Arana-Argáez V, Lara-Riegos J, Ramírez-Camacho MA, Alvarez-Sánchez ME. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Angiogenesis and Cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1370. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Wu C, Shen Y, Wang K, Tang L, Zhou M, Yang M, Pan T, Liu X, Xu W. Ten-eleven translocation 2 demethylates the MMP9 promoter, and its down-regulation in preeclampsia impairs trophoblast migration and invasion. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(26):10059-10070. [CrossRef]

- Plaks V, Rinkenberger J, Dai J, Flannery M, Sund M, Kanasaki K, Ni W, Kalluri R, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 deficiency phenocopies features of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(27):11109-14. [CrossRef]

- Yan Y, Fang L, Li Y, Yu Y, Li Y, Cheng JC, Sun YP. Association of MMP2 and MMP9 gene polymorphisms with the recurrent spontaneous abortion: A meta-analysis. Gene. 2021;767:145173. [CrossRef]

- Chiu KL, He JL, Chen GL, Shen TC, Chen LH, Chen JC, Tsai CW, Chang WS, Hsia TC, Bau DT. Impacts of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Promoter Genotypes on Asthma Risk. In Vivo. 2024;38(5): 2144-2151. [CrossRef]

- Pulito-Cueto V, Atienza-Mateo B, Batista-Liz JC, Sebastián Mora-Gil M, Mora-Cuesta VM, Iturbe-Fernández D, Izquierdo Cuervo S, Aguirre Portilla C, Blanco R, López-Mejías R. Matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors as upcoming biomarker signatures of connective tissue diseases-related interstitial lung disease: towards an earlier and accurate diagnosis. Mol Med. 2025; 31(1):70. [CrossRef]

- Bilban M, Ghaffari-Tabrizi N, Hintermann E, Bauer S, Molzer S, Zoratti C, Malli R, Sharabi A, Hiden U, Graier W, Knöfler M, Andreae F, Wagner O, Quaranta V, Desoye G. Kisspeptin-10, a KiSS-1/metastin-derived decapeptide, is a physiological invasion inhibitor of primary human trophoblasts. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 8):1319-28. [CrossRef]

- Roseweir AK, Katz AA, Millar RP. Kisspeptin-10 inhibits cell migration in vitro via a receptor-GSK3 beta-FAK feedback loop in HTR8SVneo cells. Placenta. 2012;33(5):408-15. [CrossRef]

- Francis VA, Abera AB, Matjila M, Millar RP, Katz AA. Kisspeptin regulation of genes involved in cell invasion and angiogenesis in first trimester human trophoblast cells. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99680. [CrossRef]

- Moore KL, Persaud TVN, The developing human: clinically oriented embryology, 7th edition, Saunders, 2003:520.

- Thowfeequ S, Srinivas S. Embryonic and extraembryonic tissues during mammalian development: shifting boundaries in time and space. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2022;377(1865):20210255. [CrossRef]

- Donovan MF, Cascella M. Embryology, Weeks 6-8. [Updated 2022 Oct 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan- [(accessed on 10 May 2025)]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563181/.

- Findlay JK, Gear ML, Illingworth PJ, Junk SM, Kay G, Mackerras AH, Pope A, Rothenfluh HS, Wilton L. Human embryo: a biological definition. Hum Reprod. 2007; 22(4):905-11. [CrossRef]

- Gorbunova O, Shirshev S. The effect of kisspeptin on the functional activity of peripheral blood monocytes and neutrophils in the context of physiological pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2022;151:103621. [CrossRef]

- Katirci Y, Kocaman A, Ozdemir AZ. Kisspeptin expression levels in patients with placenta previa: A randomized trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(28):e38866. [CrossRef]

- Kapustin RV, Drobintseva AO, Alekseenkova EN, Onopriychuk AR, Arzhanova ON, Polyakova VO, Kvetnoy IM. Placental protein expression of kisspeptin-1 (KISS1) and the kisspeptin-1 receptor (KISS1R) in pregnancy complicated by diabetes mellitus or preeclampsia. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301(2):437-445. [CrossRef]

- Hu KL, Zhang Y, Yang Z, Zhao H, Xu H, Yu Y, Li R. Predictive value of serum kisspeptin concentration at 14 and 21 days after frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;39(1):161-167. [CrossRef]

- Ye S, Zhou L. Role of serum kisspeptin as a biomarker to detect miscarriage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2024;27(1):2417934. [CrossRef]

- Silva PHAD, Romão LGM, Freitas NPA, Carvalho TR, Porto MEMP, Araujo Júnior E, Cavalcante MB. Kisspeptin as a predictor of miscarriage: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023;36(1):2197097. [CrossRef]

- Guo J, Feng Q, Chaemsaithong P, Appiah K, Sahota DS, Leung BW, Chung JP, Li TC, Poon LC. Biomarkers at 6 weeks' gestation in the prediction of early miscarriage in pregnancy following assisted reproductive technology. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023;102(8):1073-1083. [CrossRef]

- Abbara A, Al-Memar M, Phylactou M, Kyriacou C, Eng PC, Nadir R, et al. Performance of Plasma Kisspeptin as a Biomarker for Miscarriage Improves With Gestational Age During the First Trimester. Fertil Steril 2021;116(3):809–19. [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz A, Khalid A, Jamil Z, Fatima SS, Arif S, Rehman R. Kisspeptin: A Potential Factor for Unexplained Infertility and Impaired Embryo Implantation. Int J Fertil Steril. 2017;11(2):99-104. [CrossRef]

- Kim SM, Kim JS. A Review of Mechanisms of Implantation. Dev Reprod. 2017;21(4): 351-359. [CrossRef]

- Cohen M, Bischof P. Factors regulating trophoblast invasion. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007;64(3):126-30. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Xiao Y, Wang Y, Qian C, Zhang R, Liu J, Wang Q, Zhang H. Role of kisspeptin in decidualization and unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion via the ERK1/2 signalling pathway. Placenta. 2023;133:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Saadeldin IM, Koo OJ, Kang JT, Kwon DK, Park SJ, Kim SJ, Moon JH, Oh HJ, Jang G, Lee BC. Paradoxical effects of kisspeptin: it enhances oocyte in vitro maturation but has an adverse impact on hatched blastocysts during in vitro culture. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2012;24(5):656-68. [CrossRef]

- Dorfman MD, Garcia-Rudaz C, Alderman Z, Kerr B, Lomniczi A, Dissen GA, Castellano JM, Garcia-Galiano D, Gaytan F, Xu B, Tena-Sempere M, Ojeda SR. Loss of Ntrk2/Kiss1r signaling in oocytes causes premature ovarian failure. Endocrinology. 2014;155(8):3098-111. [CrossRef]

- Pinto FM, Cejudo-Román A, Ravina CG, Fernández-Sánchez M, Martín-Lozano D, Illanes M, Tena-Sempere M, Candenas ML. Characterization of the kisspeptin system in human spermatozoa. Int J Androl. 2012;35(1):63-73. [CrossRef]

- Yan L, Yang M, Guo H, Yang L, Wu J, Li R, Liu P, Lian Y, Zheng X, Yan J, Huang J, Li M, Wu X, Wen L, Lao K, Li R, Qiao J, Tang F. Single-cell RNA-Seq profiling of human preimplantation embryos and embryonic stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(9):1131-9. [CrossRef]

- Bischof P, Campana A. Molecular mediators of implantation. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;14(5):801-14. [CrossRef]

- Kleimenova T, Polyakova V, Linkova N, Drobintseva A, Medvedev D, Krasichkov A. The Expression of Kisspeptins and Matrix Metalloproteinases in Extragenital Endometriosis. Biomedicines. 2024;12(1):94. [CrossRef]

- Babwah, AV. Uterine and placental KISS1 regulate pregnancy: what we know and the challenges that lie ahead. Reproduction. 2015;150(4):R121-8. [CrossRef]

- Okada H, Tsuzuki T, Murata H. Decidualization of the human endometrium. Reprod Med Biol. 2018;17(3):220-227. [CrossRef]

- Calder M, Chan YM, Raj R, Pampillo M, Elbert A, Noonan M, Gillio-Meina C, Caligioni C, Bérubé NG, Bhattacharya M, Watson AJ, Seminara SB, Babwah AV. Implantation failure in female Kiss1-/- mice is independent of their hypogonadic state and can be partially rescued by leukemia inhibitory factor. Endocrinology. 2014;155(8):3065-78. [CrossRef]

- Shuya LL, Menkhorst EM, Yap J, Li P, Lane N, Dimitriadis E. Leukemia inhibitory factor enhances endometrial stromal cell decidualization in humans and mice. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25288. [CrossRef]

- Zhang P, Tang M, Zhong T, Lin Y, Zong T, Zhong C, Zhang B, Ren M, Kuang H. Expression and function of kisspeptin during mouse decidualization. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97647. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Zhang J, Li D, Liu C, Guo R, Xiao Y, Zhou L, Tong L, Zhang H. kisspeptin调控Notch1/Akt/Foxo1通路参与复发性流产患者子宫内膜蜕膜化 [Notch1/Akt/Foxo1 Pathway Regulated by Kisspeptin Is Involved in Endometrial Decidualization in Patients With Recurrent Spontaneous Abortion]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2024;55(3):542-551. Chinese. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer J, Vilos AG, Vilos GA, Bhattacharya M, Babwah AV. Uterine kisspeptin receptor critically regulates epithelial estrogen receptor α transcriptional activity at the time of embryo implantation in a mouse model. Mol Hum Reprod. 2021;27(10): gaab060. [CrossRef]

- León S, Fernandois D, Sull A, Sull J, Calder M, Hayashi K, Bhattacharya M, Power S, Vilos GA, Vilos AG, Tena-Sempere M, Babwah AV. Beyond the brain-Peripheral kisspeptin signaling is essential for promoting endometrial gland development and function. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29073. Erratum in: Sci Rep. 2016;6:30954. doi: 10.1038/srep30954. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Song S, Gu S, Gu Y, Zhao P, Li D, Cheng W, Liu C, Zhang H. Kisspeptin prevents pregnancy loss by modulating the immune microenvironment at the maternal-fetal interface in recurrent spontaneous abortion. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2024;91(2):e13818. [CrossRef]

- Williams, Z. Inducing tolerance to pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1159-61. [CrossRef]

- Gorbunova OL, Shirshev SV. Molecular mechanisms of the regulation by kisspeptin of the formation and functional activity of Treg and Th17. Biochem Moscow 2016;Suppl. Ser. A 10, 180–187. [CrossRef]

- Lyall F, Bulmer JN, Duffie E, Cousins F, Theriault A, Robson SC. Human trophoblast invasion and spiral artery transformation: the role of PECAM-1 in normal pregnancy, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction. Am J Pathol. 2001;158(5):1713-21. [CrossRef]

- Moser G, Windsperger K, Pollheimer J, de Sousa Lopes SC, Huppertz B. Human trophoblast invasion: new and unexpected routes and functions. Histochem Cell Biol. 2018; 150(4):361-370. [CrossRef]

- James JL, Saghian R, Perwick R, Clark AR. Trophoblast plugs: impact on utero-placental haemodynamics and spiral artery remodelling. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(8): 1430-1441. [CrossRef]

- Saghian R, Bogle G, James JL, Clark AR. Establishment of maternal blood supply to the placenta: insights into plugging, unplugging and trophoblast behaviour from an agent-based model. Interface Focus. 2019;9(5):20190019. [CrossRef]

- Velicky P, Knöfler M, Pollheimer J. Function and control of human invasive trophoblast subtypes: Intrinsic vs. maternal control. Cell Adh Migr. 2016;10(1-2):154-62. [CrossRef]

- Barrientos G, Pussetto M, Rose M, Staff AC, Blois SM, Toblli JE. Defective trophoblast invasion underlies fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia-like symptoms in the stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rat. Mol Hum Reprod. 2017;23(7):509-519. [CrossRef]

- Huppertz, B. The Critical Role of Abnormal Trophoblast Development in the Etiology of Preeclampsia. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2018;19(10):771-780. [CrossRef]

- Staff AC, Fjeldstad HE, Fosheim IK, Moe K, Turowski G, Johnsen GM, Alnaes-Katjavivi P, Sugulle M. Failure of physiological transformation and spiral artery atherosis: their roles in preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(2S):S895-S906. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Liu J, Inuzuka H, Wei W. Functional analysis of the emerging roles for the KISS1/KISS1R signaling pathway in cancer metastasis. J Genet Genomics. 2022;49(3):181-184. [CrossRef]

- Harihar S, Welch DR. KISS1 metastasis suppressor in tumor dormancy: a potential therapeutic target for metastatic cancers? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023;42(1):183-196. [CrossRef]

- Anacker J, Segerer SE, Hagemann C, Feix S, Kapp M, Bausch R, Kämmerer U. Human decidua and invasive trophoblasts are rich sources of nearly all human matrix metalloproteinases. Mol Hum Reprod. 2011;17(10):637-52. [CrossRef]

- Hisamatsu Y, Murata H, Tsubokura H, Hashimoto Y, Kitada M, Tanaka S, Okada H. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Human Decidualized Endometrial Stromal Cells. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2021;43(3):2111-2123. [CrossRef]

- Janneau JL, Maldonado-Estrada J, Tachdjian G, Miran I, Motté N, Saulnier P, Sabourin JC, Coté JF, Simon B, Frydman R, Chaouat G, Bellet D. Transcriptional expression of genes involved in cell invasion and migration by normal and tumoral trophoblast cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(11):5336-9. [CrossRef]

- Ferretti C, Bruni L, Dangles-Marie V, Pecking AP, Bellet D. Molecular circuits shared by placental and cancer cells, and their implications in the proliferative, invasive and migratory capacities of trophoblasts. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13(2):121-41. [CrossRef]

- Gomes VCL, Sones JL. From inhibition of trophoblast cell invasion to proapoptosis: what are the potential roles of kisspeptins in preeclampsia? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2021;321(1):R41-R48. [CrossRef]

- Gomes VCL, Woods AK, Crissman KR, Landry CA, Beckers KF, Gilbert BM, Ferro LR, Liu CC, Oberhaus EL, Sones JL. Kisspeptin Is Upregulated at the Maternal-Fetal Interface of the Preeclamptic-like BPH/5 Mouse and Normalized after Synchronization of Sex Steroid Hormones. Reprod Med (Basel). 2022;3(4):263-279. [CrossRef]

- Todros T, Paulesu L, Cardaropoli S, Rolfo A, Masturzo B, Ermini L, Romagnoli R, Ietta F. Role of the Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor in the Pathophysiology of Pre-Eclampsia. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):1823. [CrossRef]

- Ietta F, Ferro EAV, Bevilacqua E, Benincasa L, Maioli E, Paulesu L. Role of the Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (MIF) in the survival of first trimester human placenta under induced stress conditions. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12150. [CrossRef]

- Martino NA, Rizzo A, Pizzi F, Dell'Aquila ME, Sciorsci RL. Effects of kisspeptin-10 on in vitro proliferation and kisspeptin receptor expression in primary epithelial cell cultures isolated from bovine placental cotyledons of fetuses at the first trimester of pregnancy. Theriogenology. 2015;83(6):978-987.e1. [CrossRef]

- Zhai J, Liu J, Zhao S, Zhao H, Chen ZJ, Du Y, Li W. Kisspeptin-10 inhibits OHSS by suppressing VEGF secretion. Reproduction. 2017;154(4):355-362. [CrossRef]

- Santos LC, Dos Anjos Cordeiro JM, da Silva Santana L, Santos BR, Barbosa EM, da Silva TQM, Corrêa JMX, Niella RV, Lavor MSL, da Silva EB, de Melo Ocarino N, Serakides R, Silva JF. Kisspeptin/Kiss1r system and angiogenic and immunological mediators at the maternal-fetal interface of domestic cats. Biol Reprod. 2021;105(1):217-231. [CrossRef]

- Cai J, Han X, Peng S, Chen J, Zhang JV, Huang C. Chemerin facilitates placental trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling through the pentose phosphate pathway. Life Sci. 2025 :123645. [CrossRef]

- Jansen CHJR, Kastelein AW, Kleinrouweler CE, Van Leeuwen E, De Jong KH, Pajkrt E, Van Noorden CJF. Development of placental abnormalities in location and anatomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(8):983-993. [CrossRef]

- Fox, H. (1992). Ectopic Sites of Placentation. In: Barnea, E.R., Hustin, J., Jauniaux, E. (eds) The First Twelve Weeks of Gestation. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Rathbun KM, Hildebrand JP. Placenta Abnormalities. StatPearls [Internet]. [Updated 2022 Oct 17]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL, USA: 2022. [(accessed on 5 May 2025)]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459355/.

- Ghafouri-Fard S, Shoorei H, Taheri M. The role of microRNAs in ectopic pregnancy: A concise review. Noncoding RNA Res. 2020;5(2):67-70. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ruiz A, Avendaño MS, Dominguez F, Lozoya T, Molina-Abril H, Sangiao-Alvarellos S, Gurrea M, Lara-Chica M, Fernandez-Sanchez M, Torres-Jimenez E, Perdices-Lopez C, Abbara A, Steffani L, Calzado MA, Dhillo WS, Pellicer A, Tena-Sempere M. Deregulation of miR-324/KISS1/kisspeptin in early ectopic pregnancy: mechanistic findings with clinical and diagnostic implications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(5):480.e1-480.e17. [CrossRef]

- Meena P, Mathur R, Meena ML. Kisspeptin: new biomarker of pregnancy. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2019;8(8):3021–3024. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan-Pyke C, Haisenleder DJ, Senapati S, Nicolais O, Eisenberg E, Sammel MD, Barnhart KT. Kisspeptin as a new serum biomarker to discriminate miscarriage from viable intrauterine pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(1):137-141.e2. [CrossRef]

- Jayasena CN, Abbara A, Izzi-Engbeaya C, Comninos AN, Harvey RA, Gonzalez Maffe J, Sarang Z, Ganiyu-Dada Z, Padilha AI, Dhanjal M, Williamson C, Regan L, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR, Dhillo WS. Reduced levels of plasma kisspeptin during the antenatal booking visit are associated with increased risk of miscarriage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(12):E2652-60. [CrossRef]

- Yuksel S, Ketenci Gencer F. Serum kisspeptin, to discriminate between ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage and first trimester pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022; 42(6):2095-2099. [CrossRef]

- Hu KL, Chen Z, Deng W, Li X, Ju L, Yang H, Zhang H, Mu L. Diagnostic Value of Kisspeptin Levels on Early Pregnancy Outcome: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Reprod Sci. 2022;29(12):3365-3372. [CrossRef]

- Kavvasoglu S, Ozkan ZS, Kumbak B, Sımsek M, Ilhan N. Association of kisspeptin-10 levels with abortus imminens: a preliminary study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012; 285(3):649-53. [CrossRef]

- Park DW, Lee SK, Hong SR, Han AR, Kwak-Kim J, Yang KM. Expression of Kisspeptin and its receptor GPR54 in the first trimester trophoblast of women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;67(2):132-9. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Tian J, Zhou L, Wu S, Zhang S, Qi L, Zhang H. Role of kisspeptin/GPR54 in the first trimester trophoblast of women with a history of recurrent spontaneous abortion. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10(8):8161-8173.

| Parameter | Normal pregnancy | Abnormal pregnancy # | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ectopic pregnancy | GTN | Placenta previa | Miscarriage | ||

| Kisspeptin concentration in plasma or serum |

↑* [33,197,198] |

↓ [67,69,195,196,200] |

↑ [68] |

↓ [143] |

↓ [145,146,148,198,199,200,201,202,203] or INC [32] |

| KISS1 expression in trophoblast/ placental tissue | N/A |

↓ [196] |

↑ [182] |

↓ [143] |

↓ [32,203,204] |

| KISS1R expression in trophoblast/ placental tissue | N/A | N/D |

↑ [182] |

↑ [143] |

↓ [32,204] or WNR [203] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).