Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Geological Heterogeneous Field

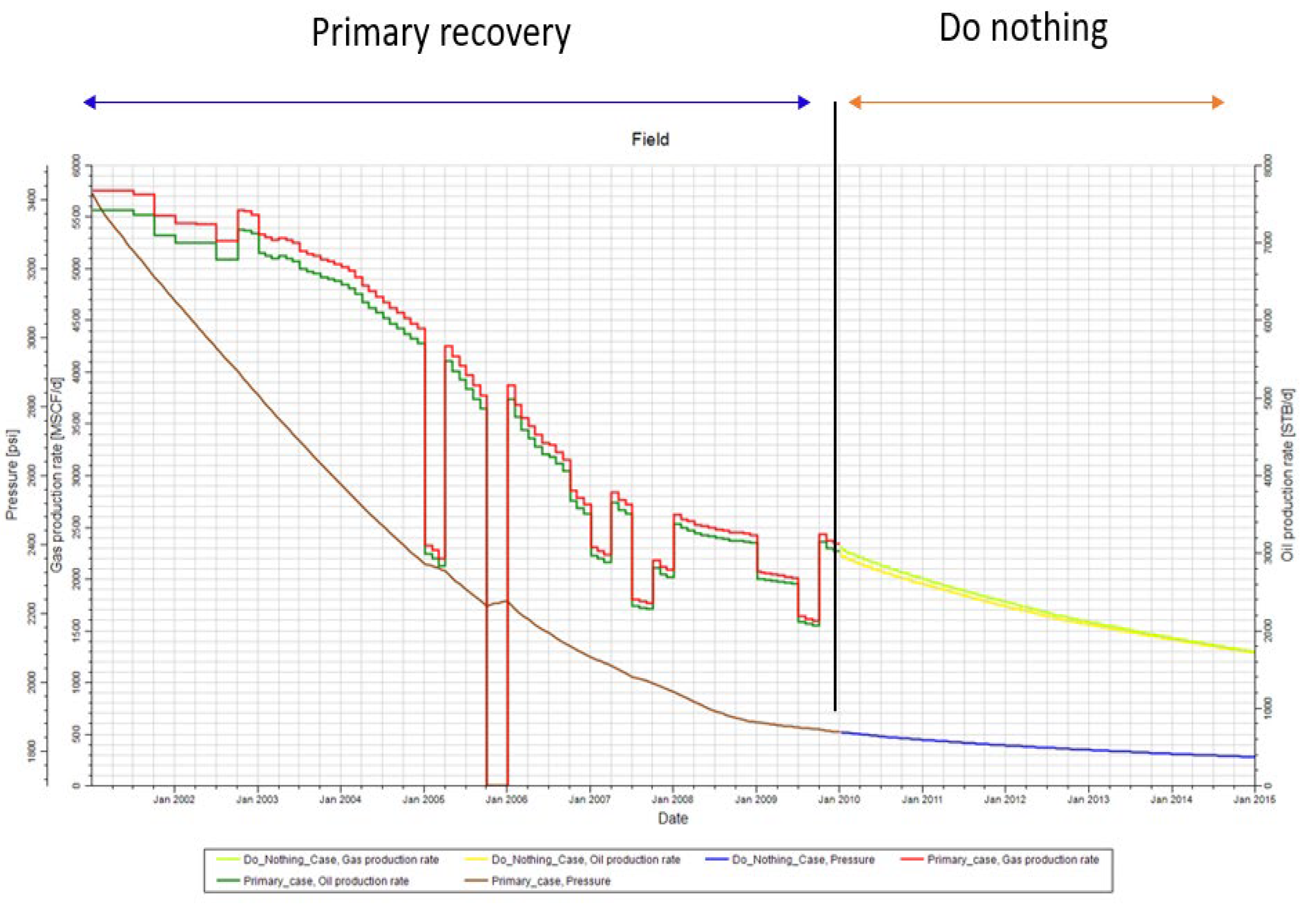

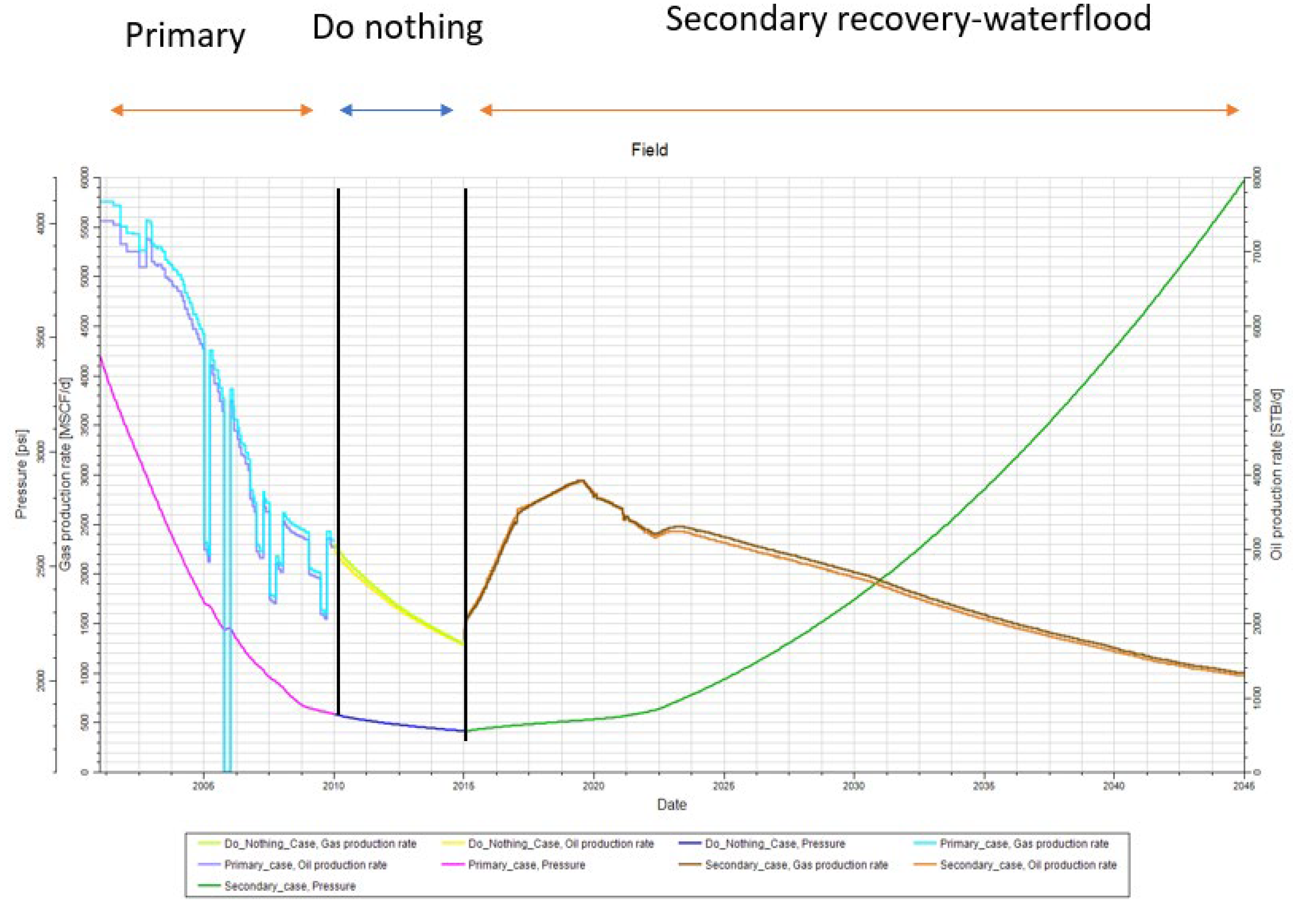

1.1.1. Reservoir History

2. Methodology

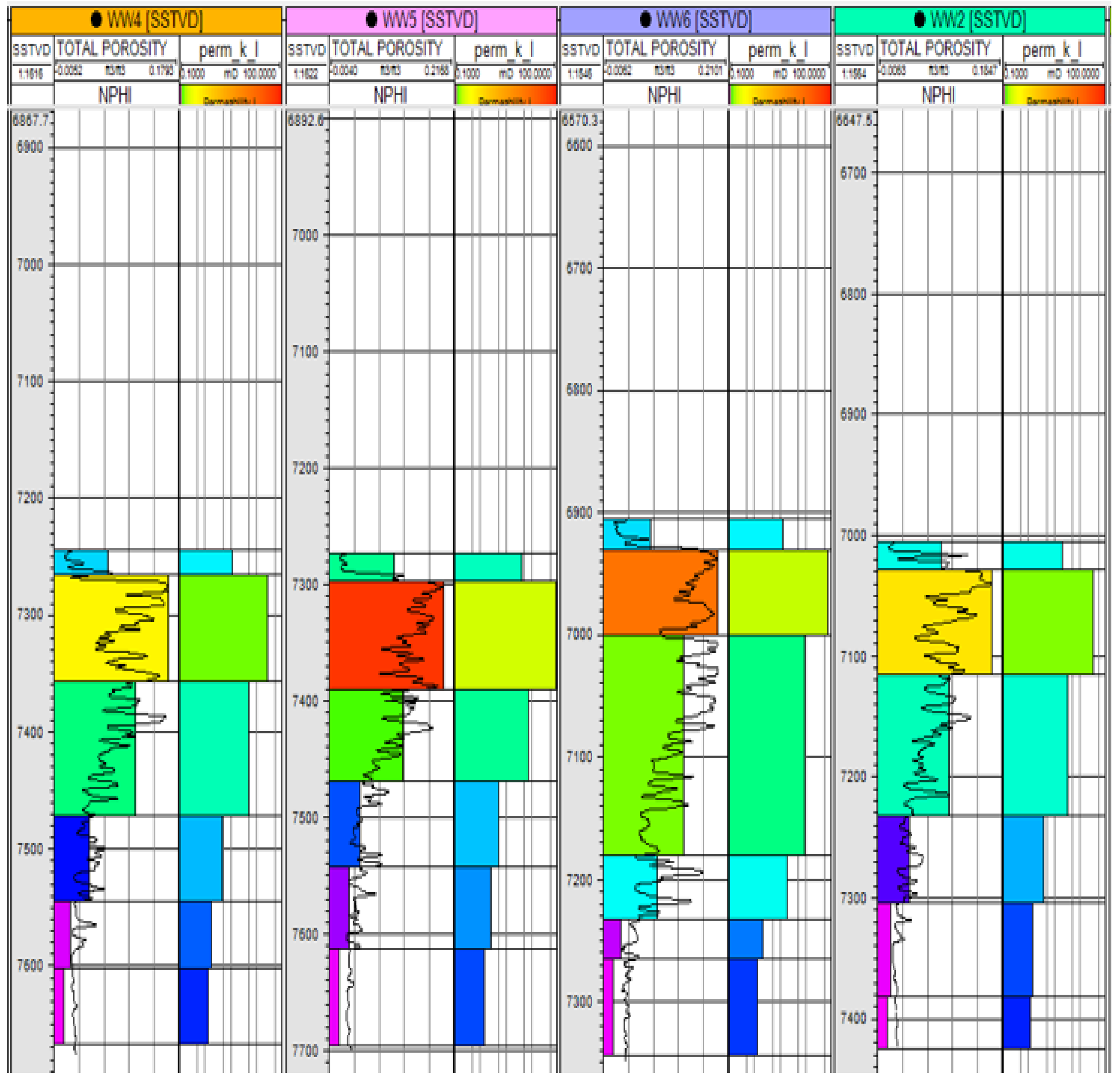

2.1. Data Collection and Preliminary Analysis

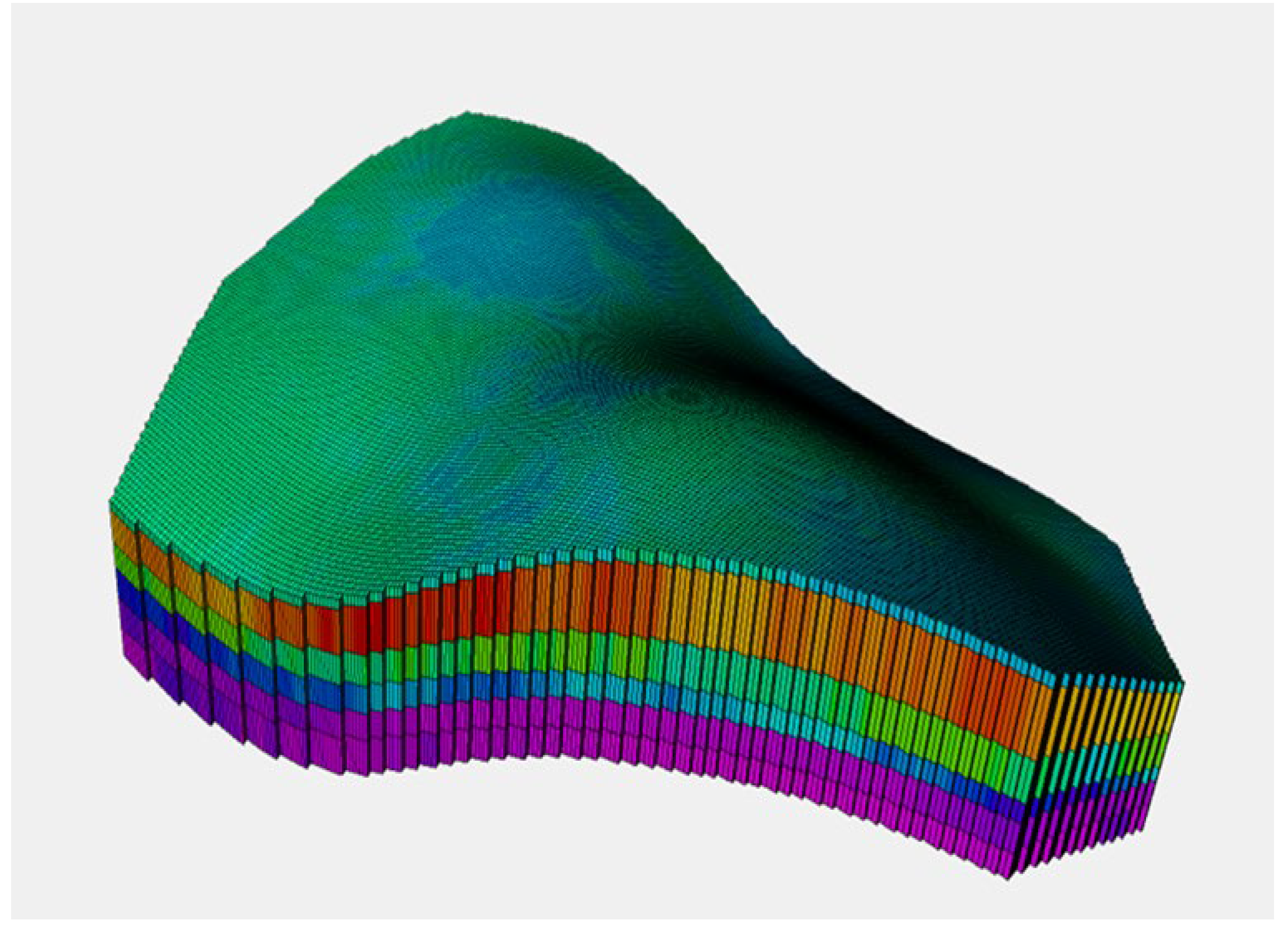

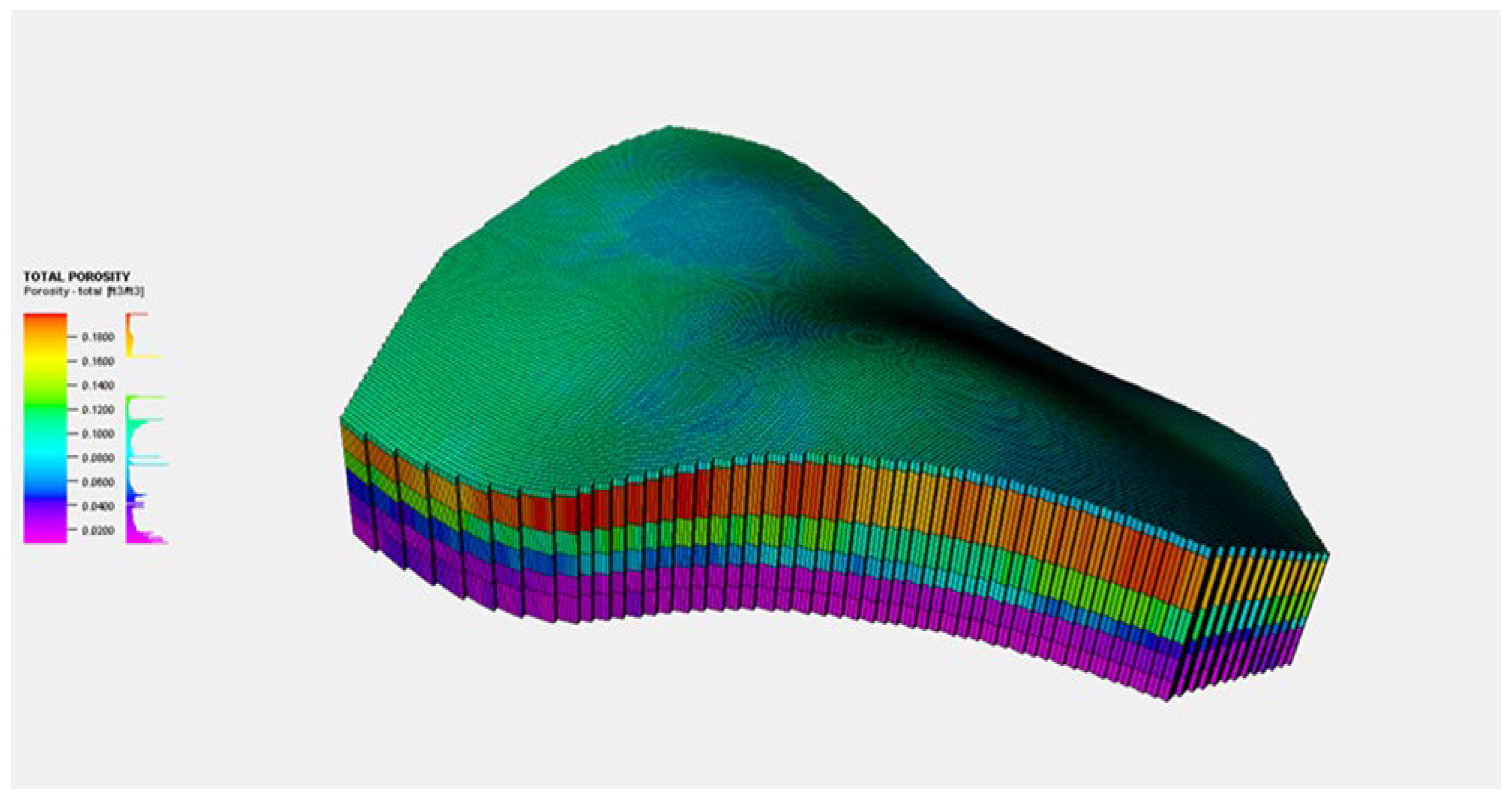

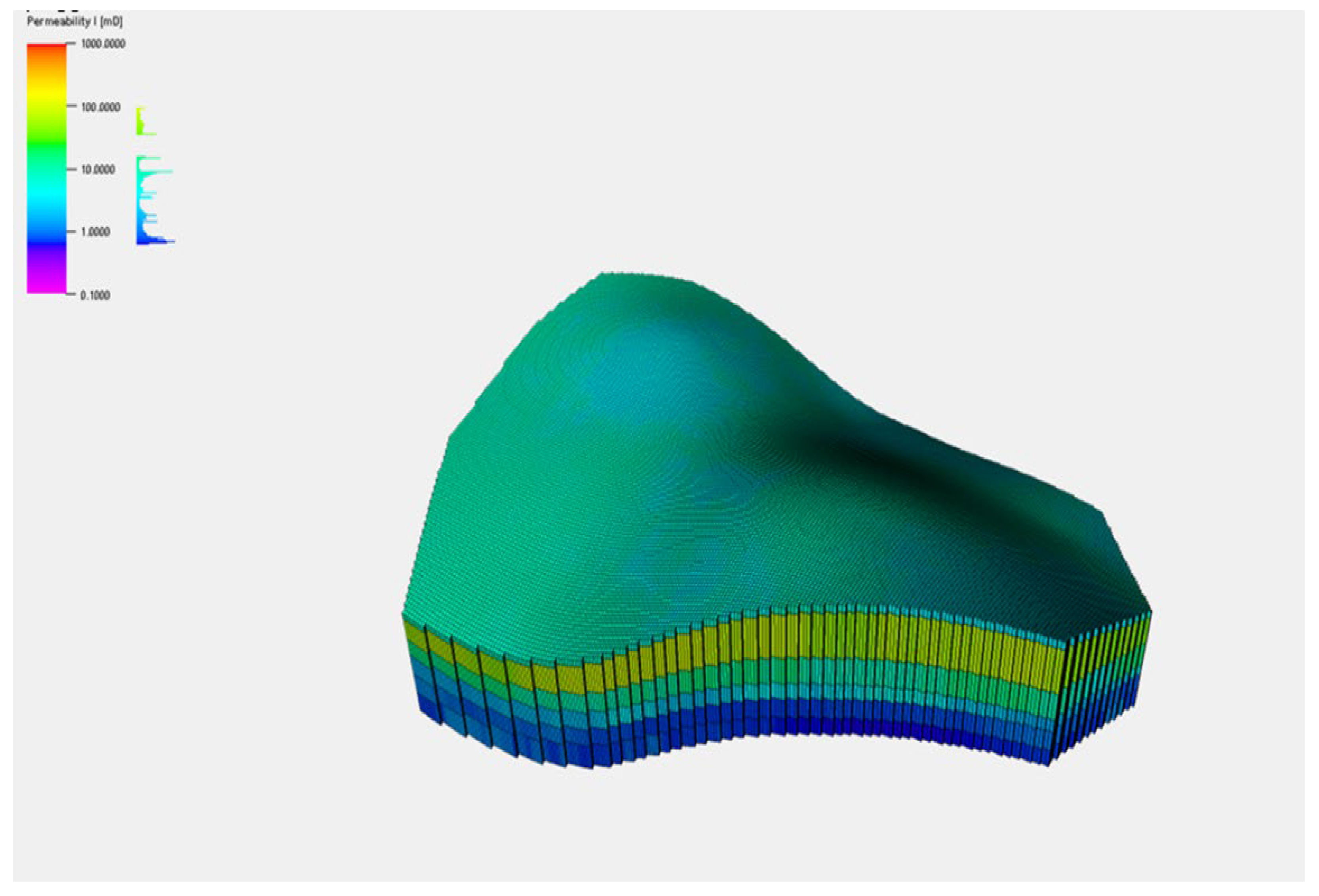

2.2. Construction of the Geological and Simulation Models

2.3. Screening Process

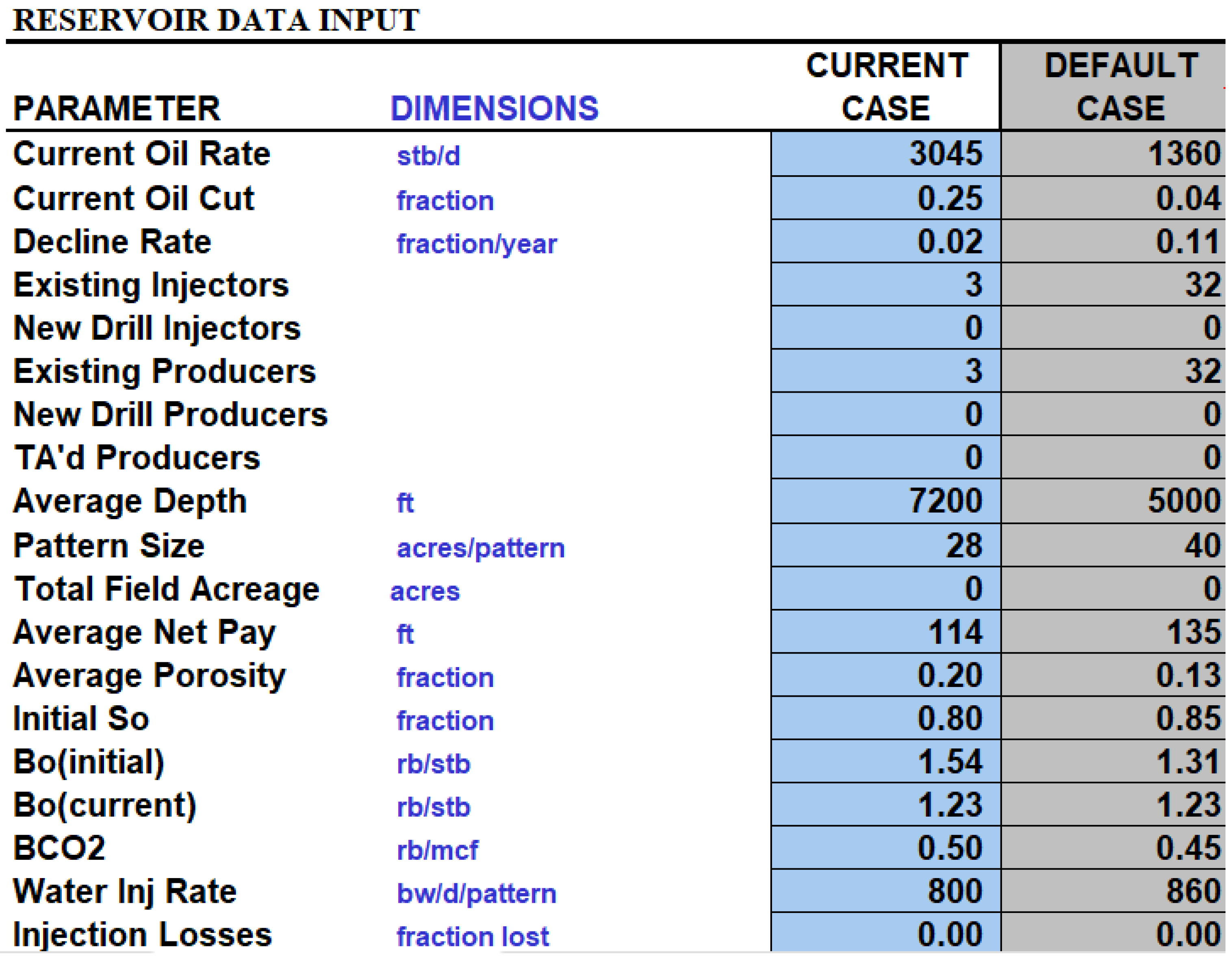

2.3.1. Using the CO2-Prophet

| Parameter | Value | Units |

| Original Oil in Place | 2.58E+08 | STB |

| Initial formation volume factor | 1.54 | rb/stb |

| Initial Oil Saturation | 0.80 | frac |

| Temperature | 220 | OF |

| MMP | 3700 | psi |

| Oil Viscosity | 1.232 | cp |

| Dykstra Parsons coefficient | 0.7 | unitless |

| Salinity | 10,000 | ppm |

2.3.2. KM CO2 Flood Screening Model

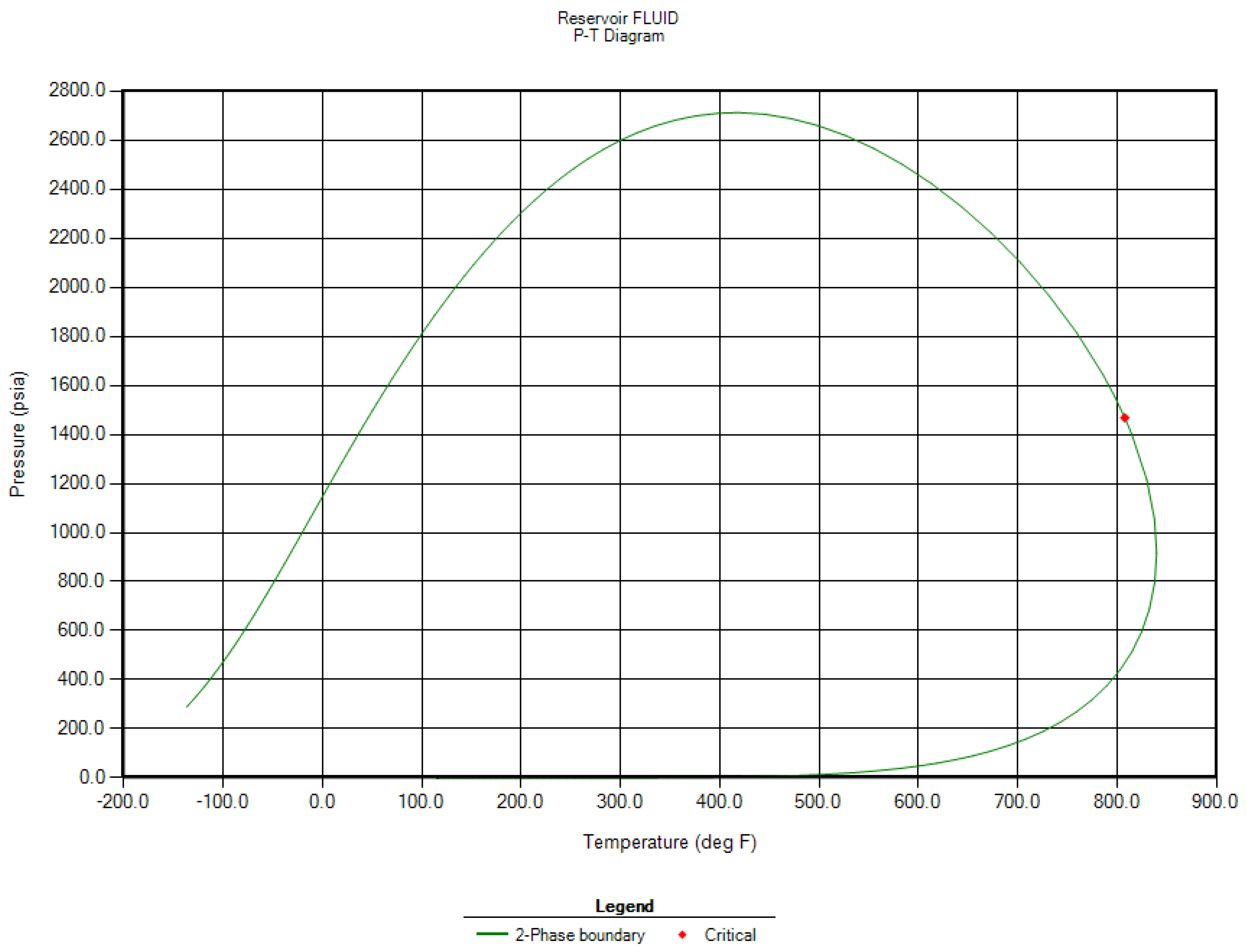

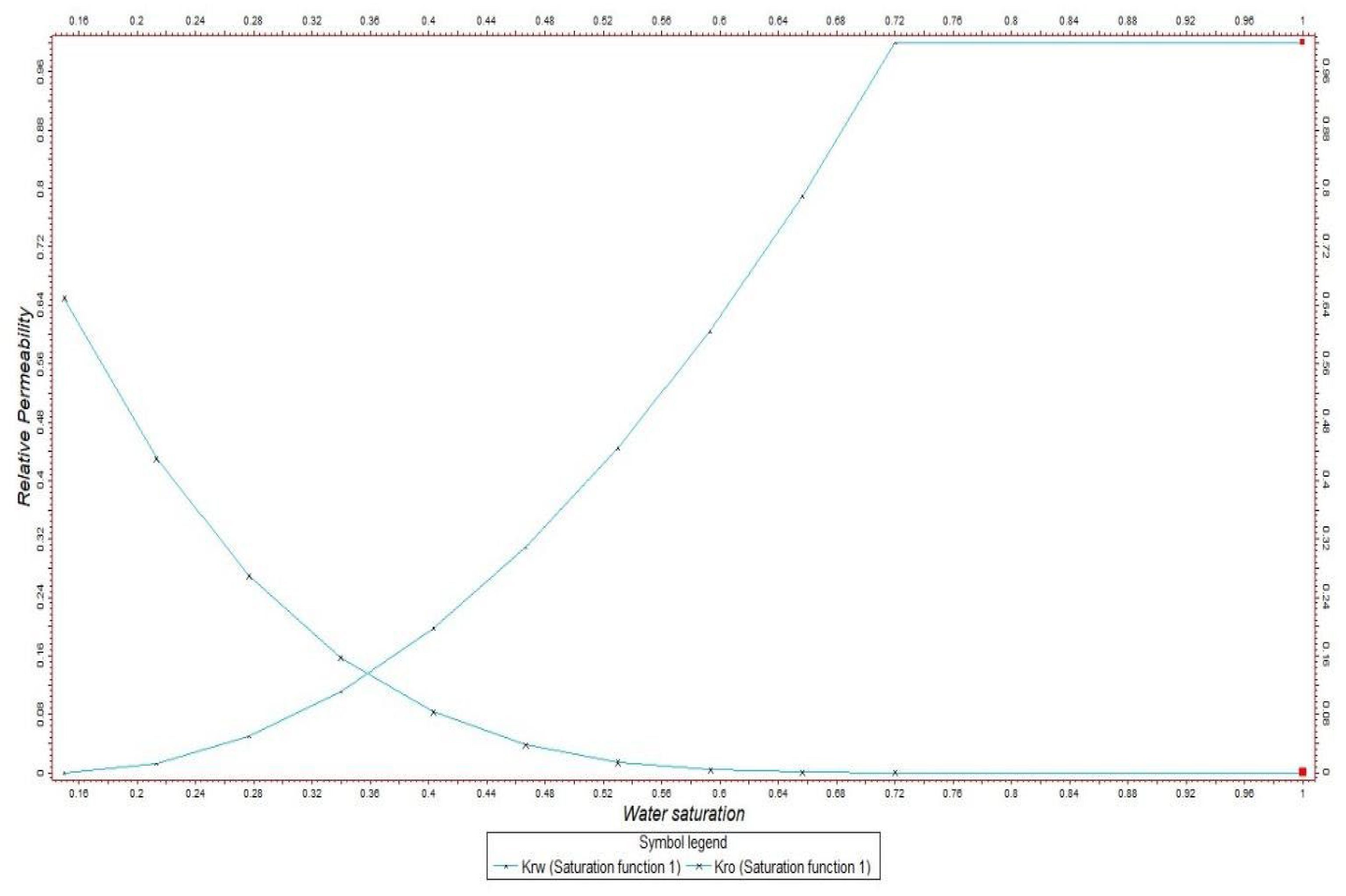

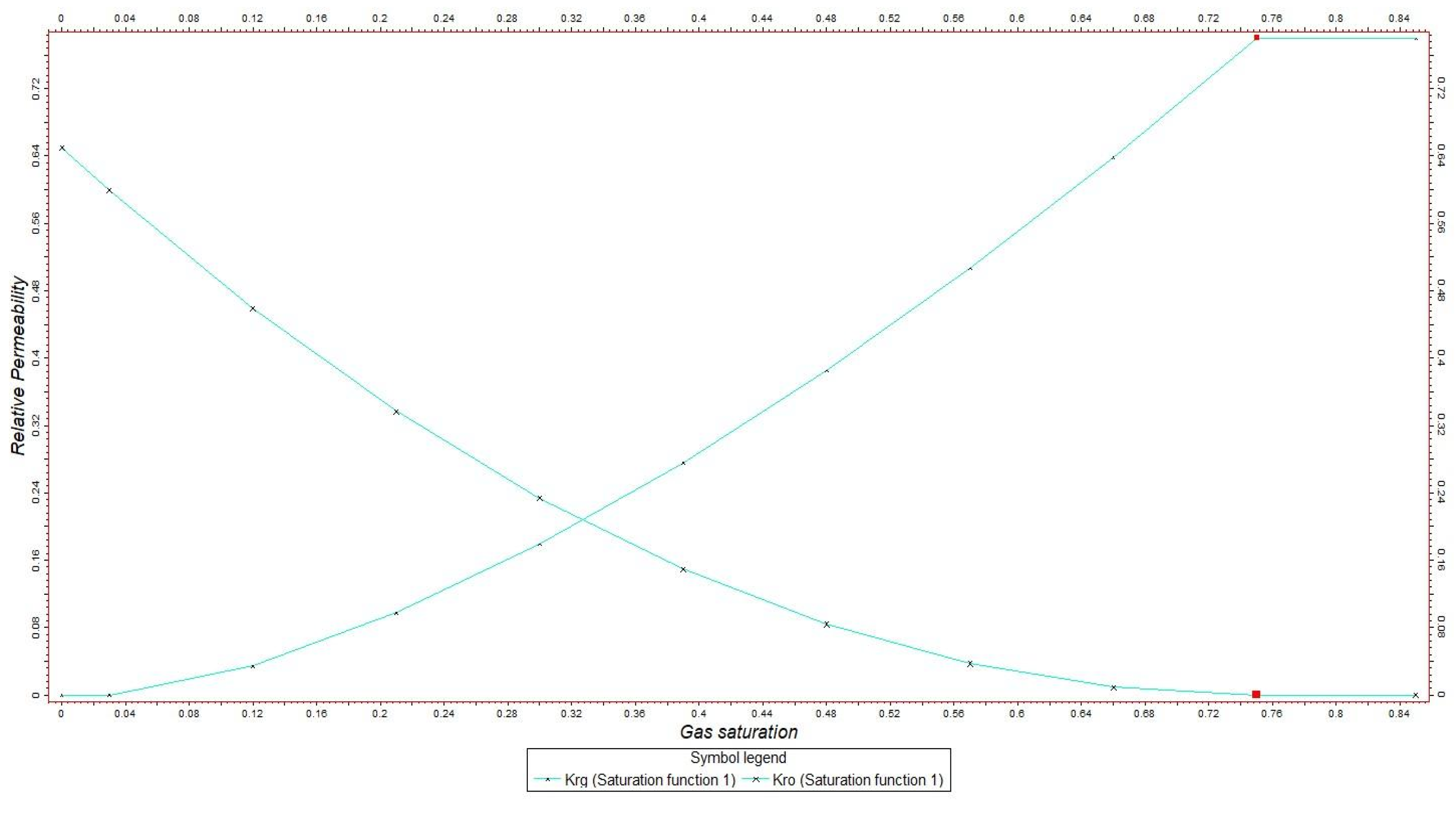

2.4. Development of A Compositional Simulation Model Fluid Model

| Component | Mol frac % | Mol wt.gm/mol | Crit.Temp (degR) Crit. Pres Psi Acentric Factor |

| N2 CO2 H2S |

0.44 | 28.013 | 227.16 492.31428 0.04 |

| 4.8 | 44.01 | 548.46 1071.3347 0.225 | |

| 2.51 | 34.076 | 672.48 1296.1827 0.1 | |

| C1 C2 |

28.78 | 16.043 | 343.08 667.78391 0.013 |

| 10.53 | 30.07 | 549.774 708.34473 0.0986 | |

| C3 C4 C5H12_FC6 HYPO1_04 |

7.42 | 44.097 | 665.64 615.76025 0.1524 |

| 4.72 | 58.124 | 755.1 543.45619 0.1956 | |

| 7.21 | 86.8 | 996.372 591.02878 0.2118 | |

| 33.59 | 190 | 1270.8 269.81762 0.516 |

2.4.1. Tuning/Regression Analysis

2.4.2. Equation of the State

2.5. Improved oil recovery (IOR) method

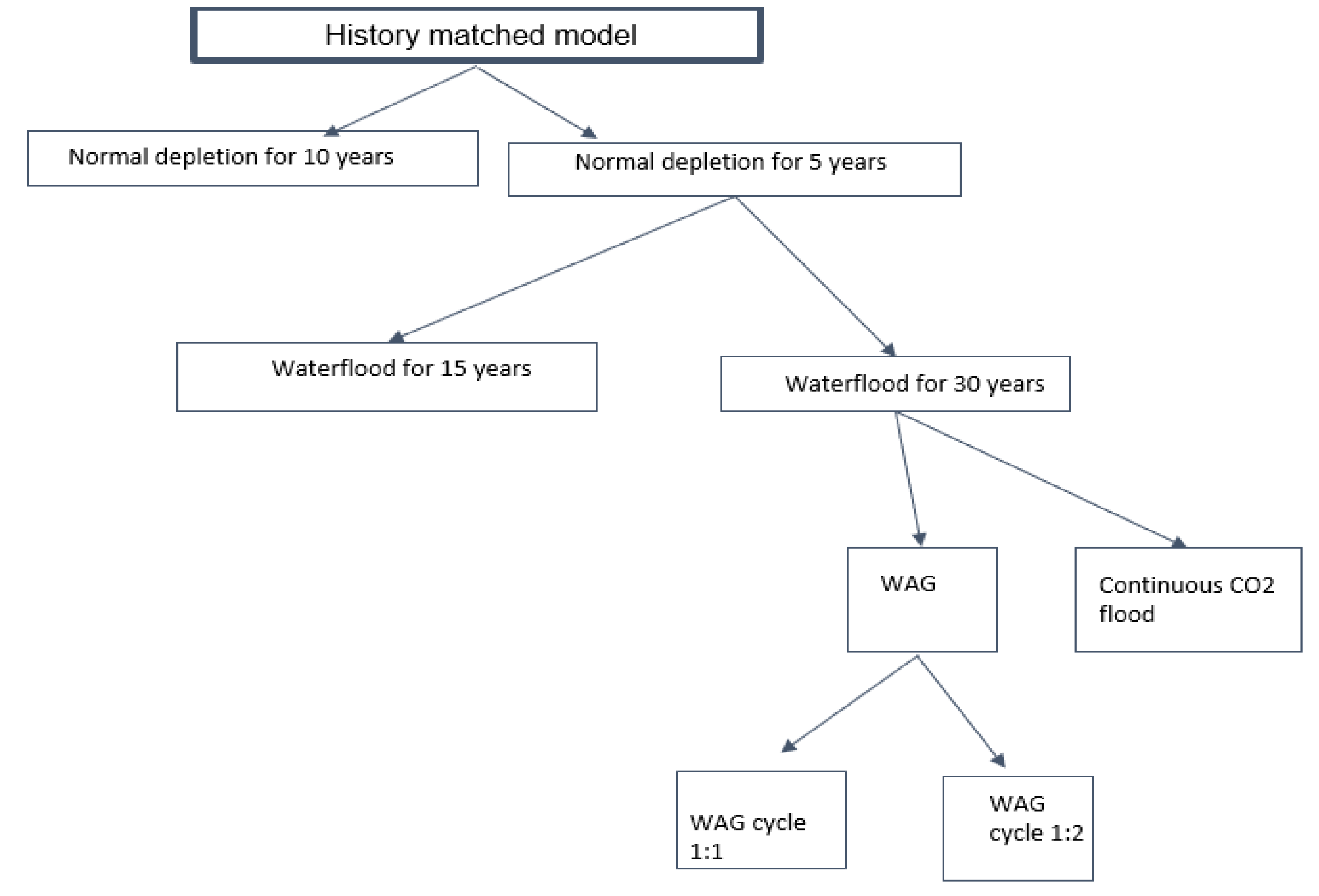

2.6. Development Scenarios

2.7. Economic Analysis

2.7.1. Capital Expenditures

2.7.2. CO2 Distribution System

2.7.3. Operating Expenditures

3. Results and Discussion

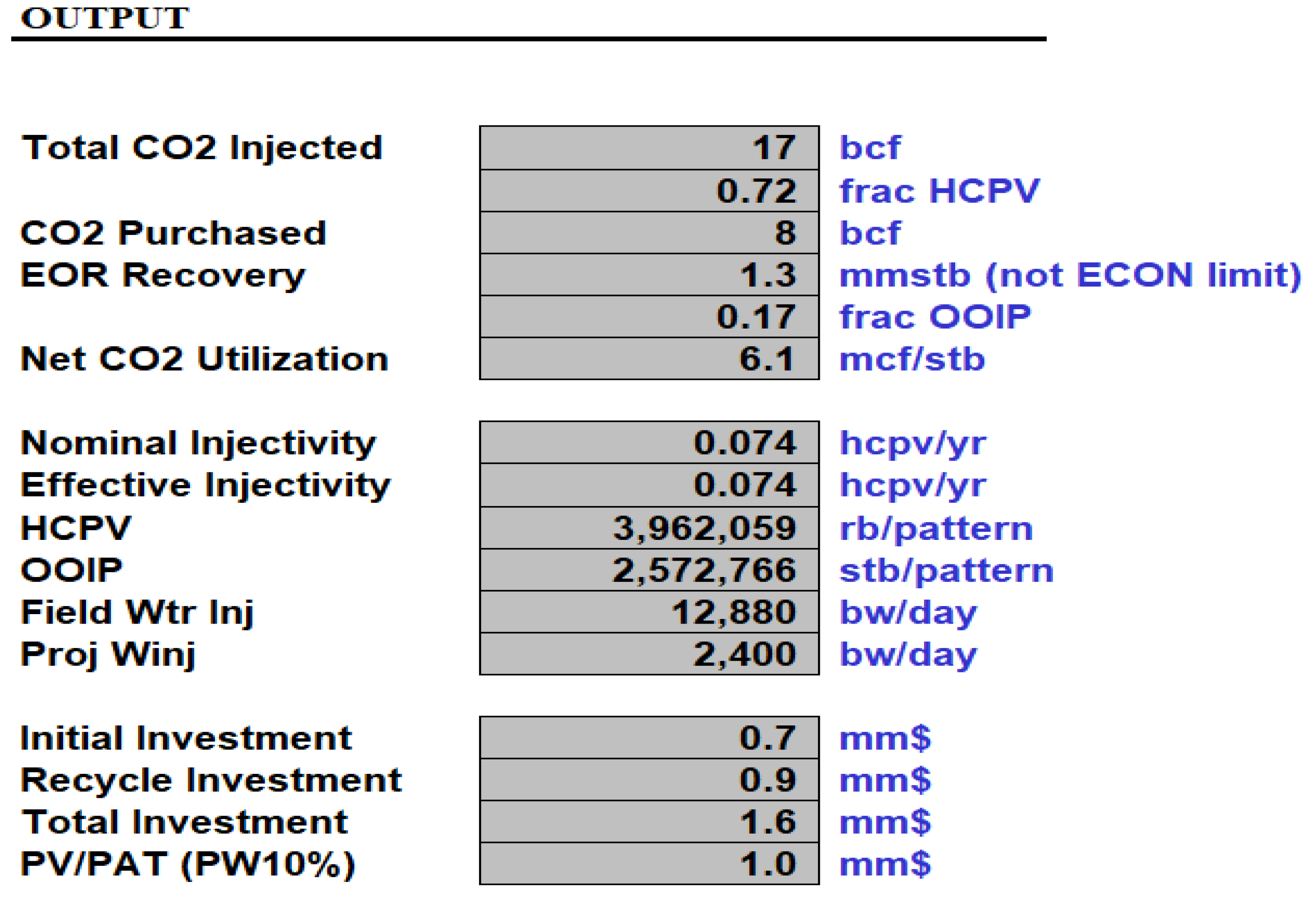

3.1. Results and Discussion from the CO2-Prophet

3.2. Results from the KM Scoping

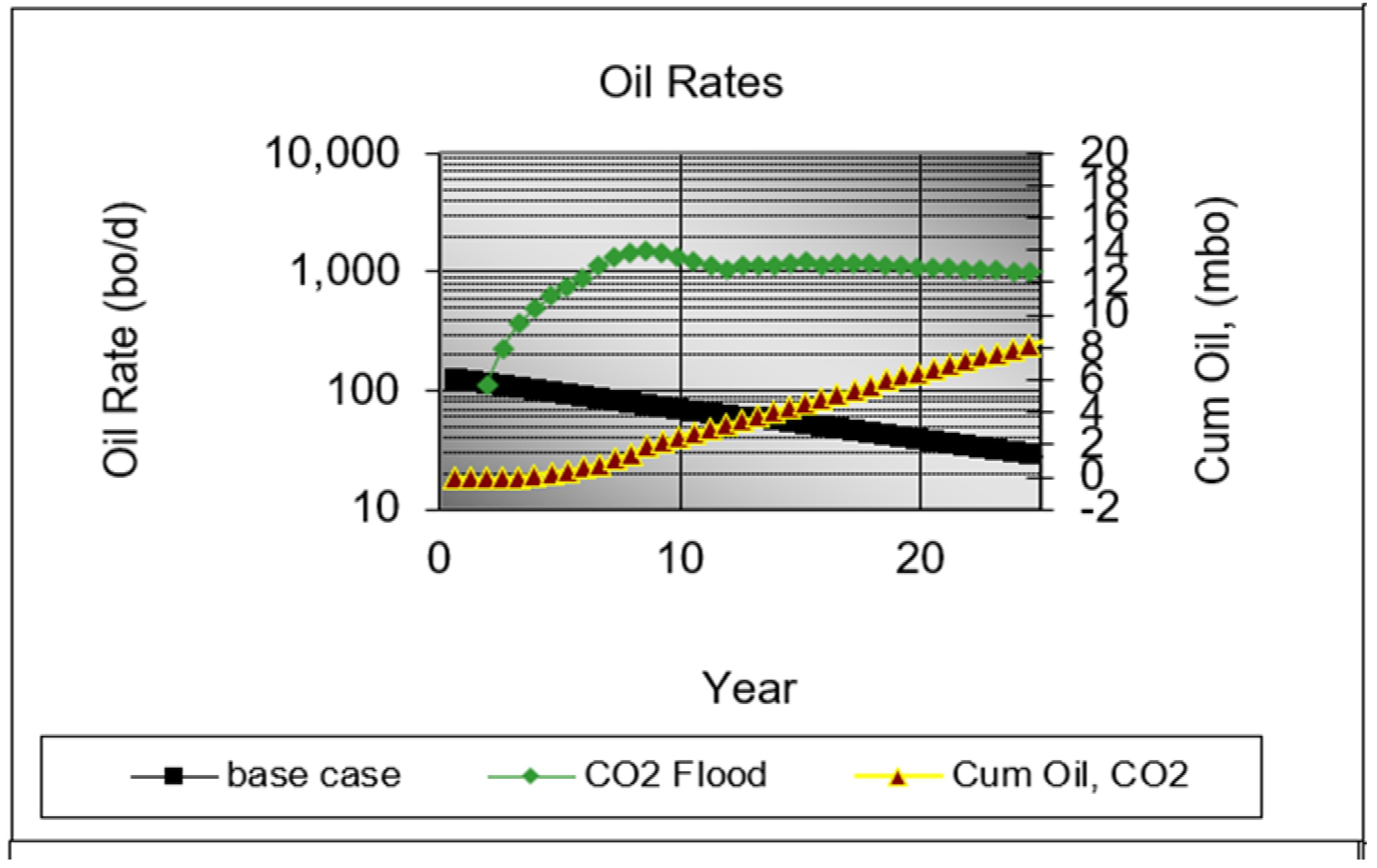

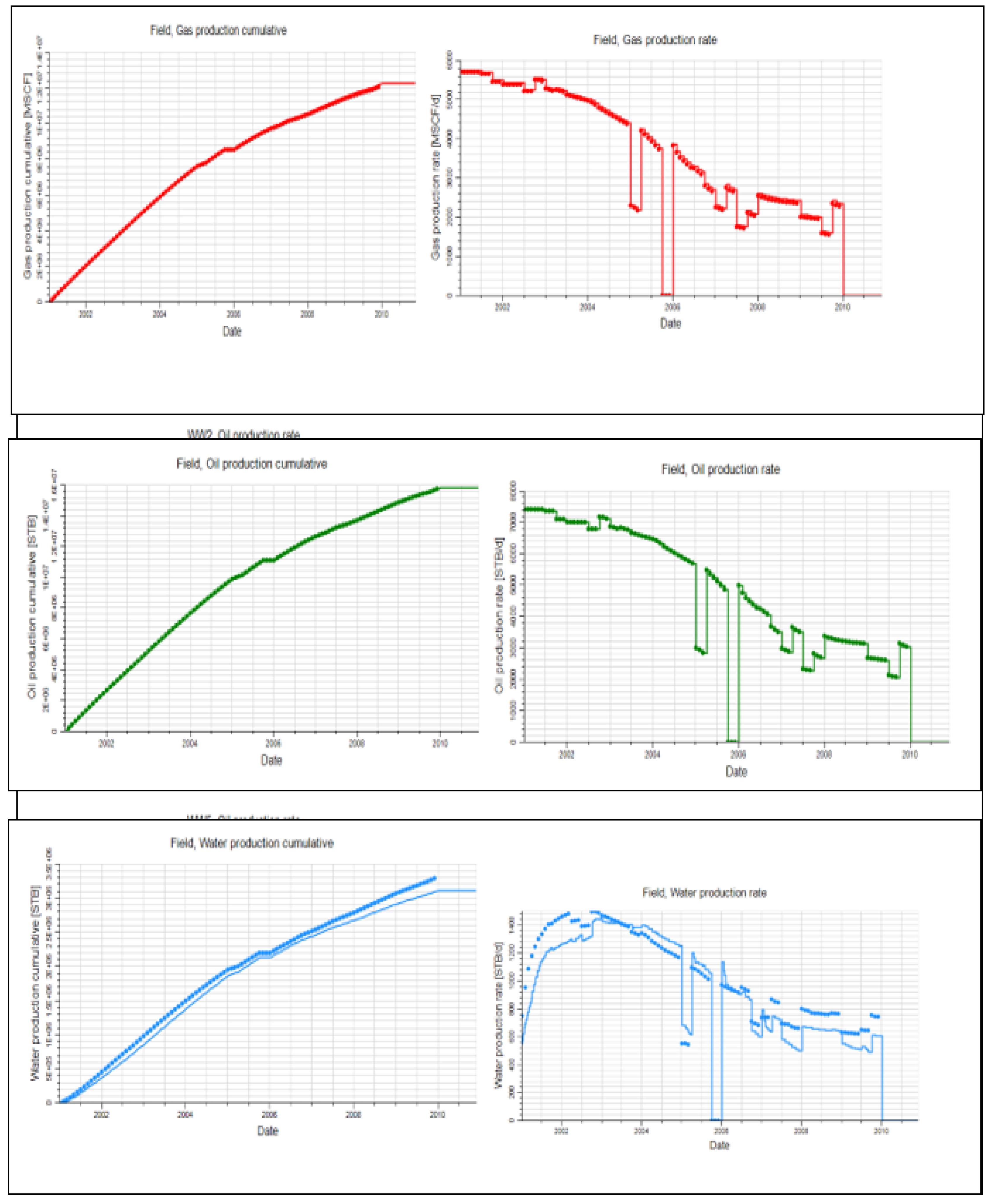

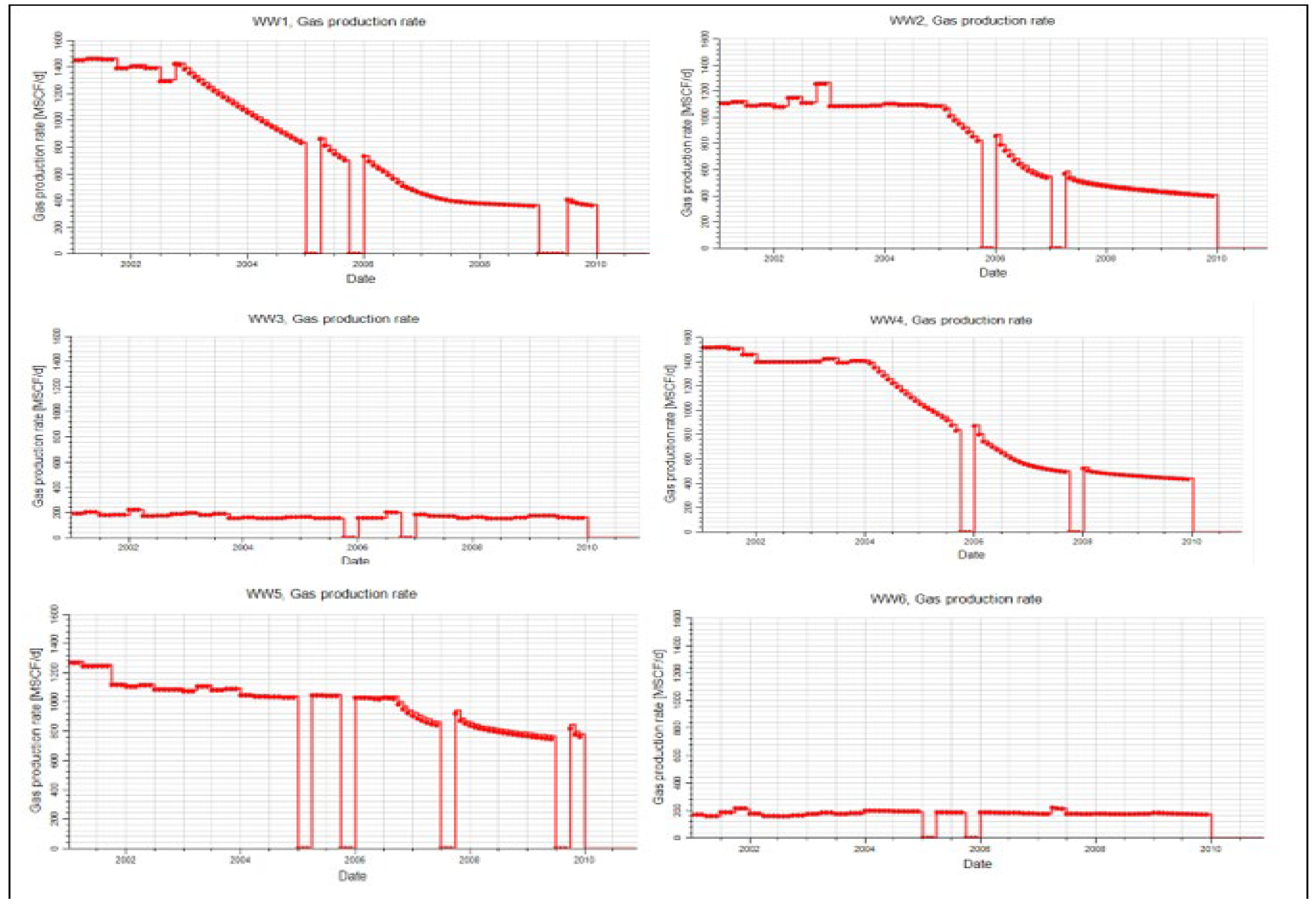

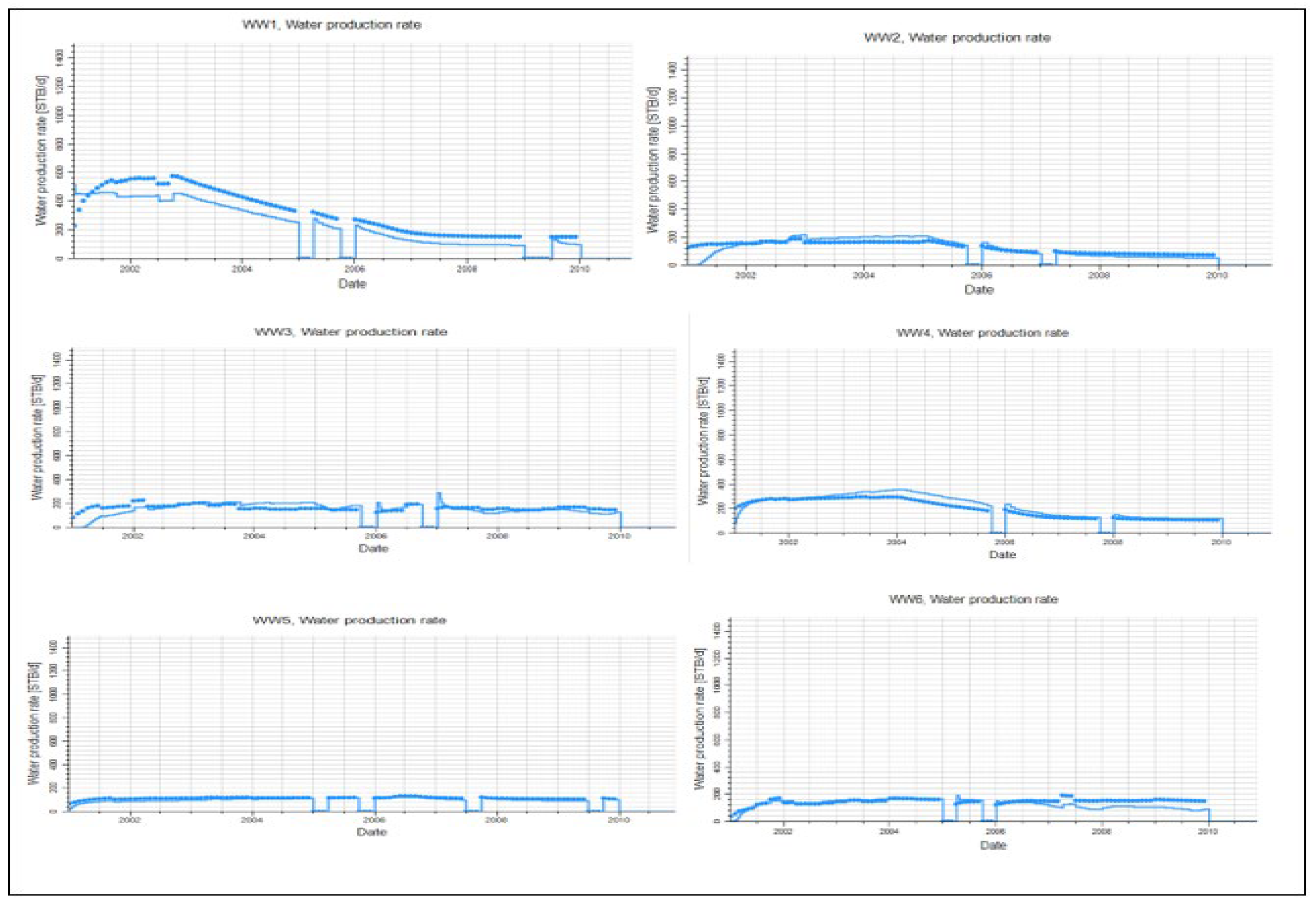

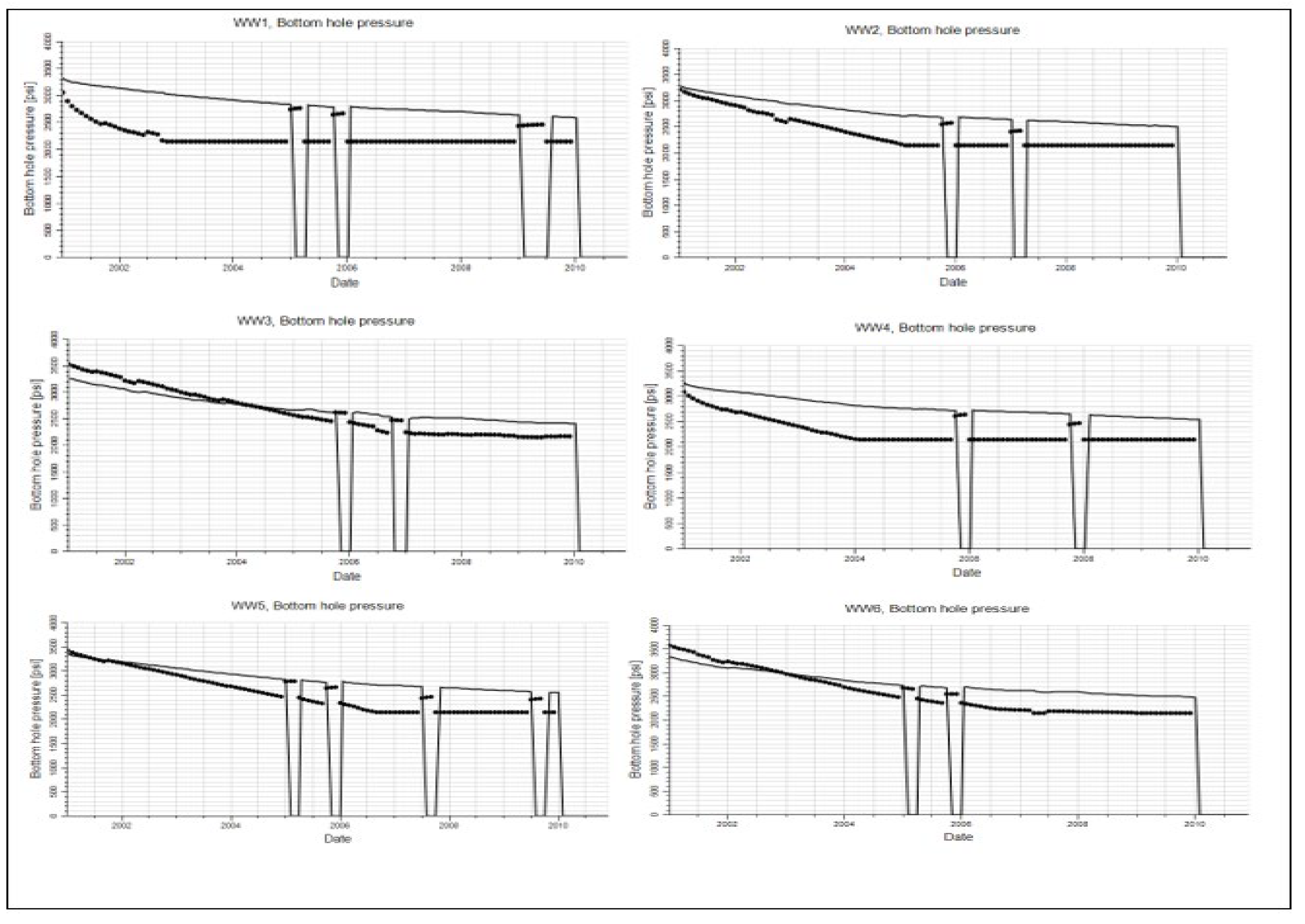

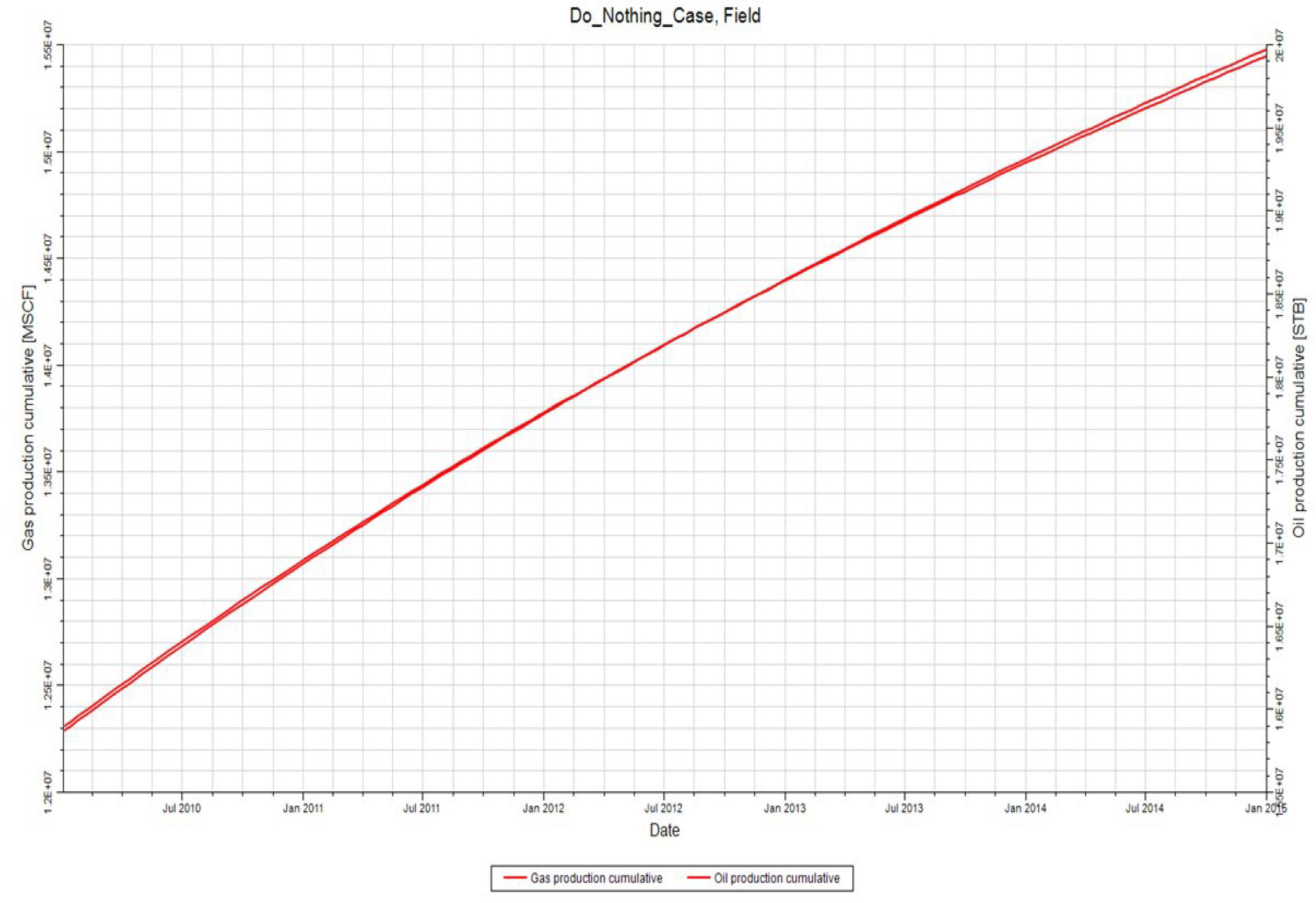

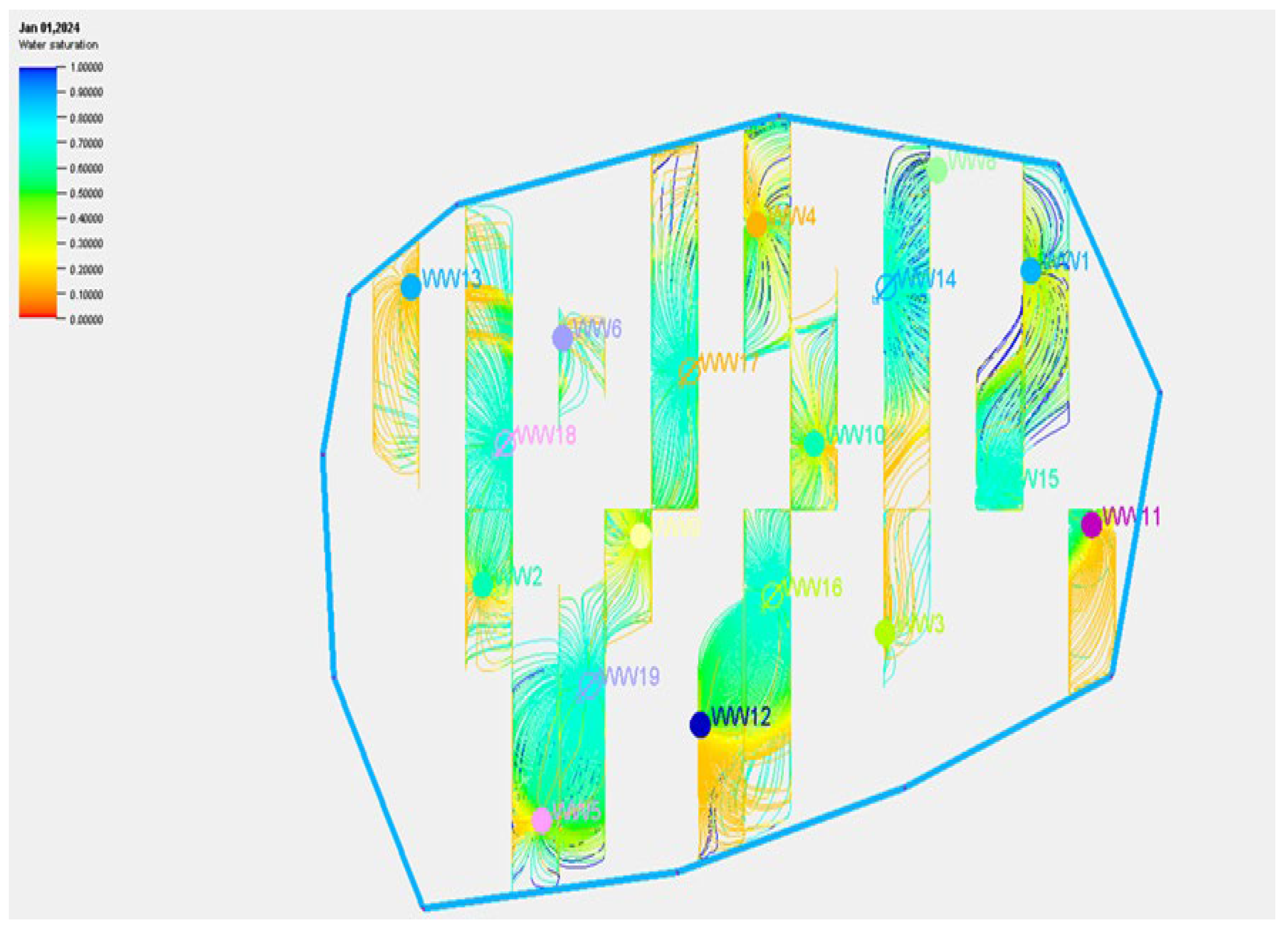

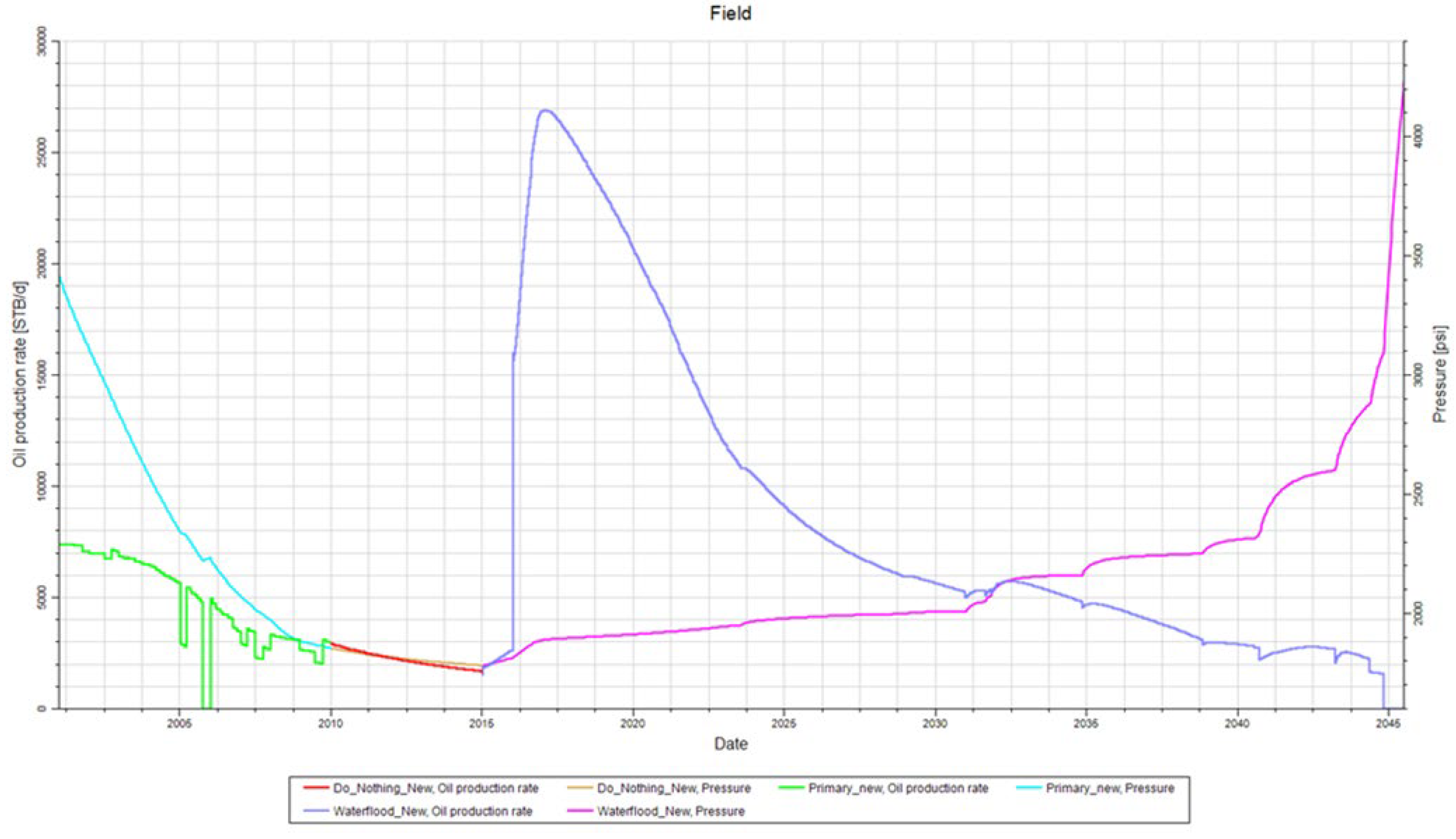

3.3. Simulation Results for the History Match

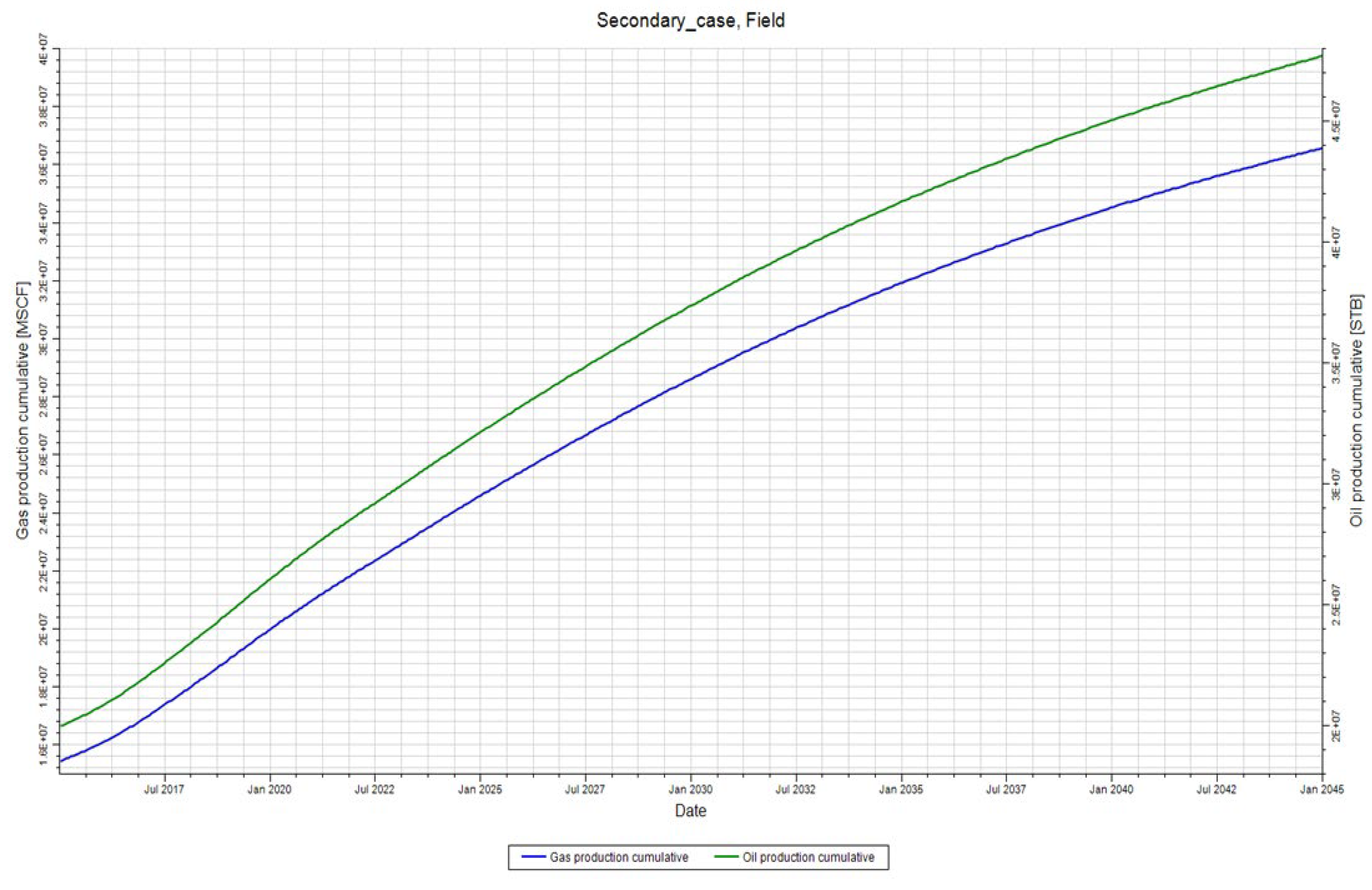

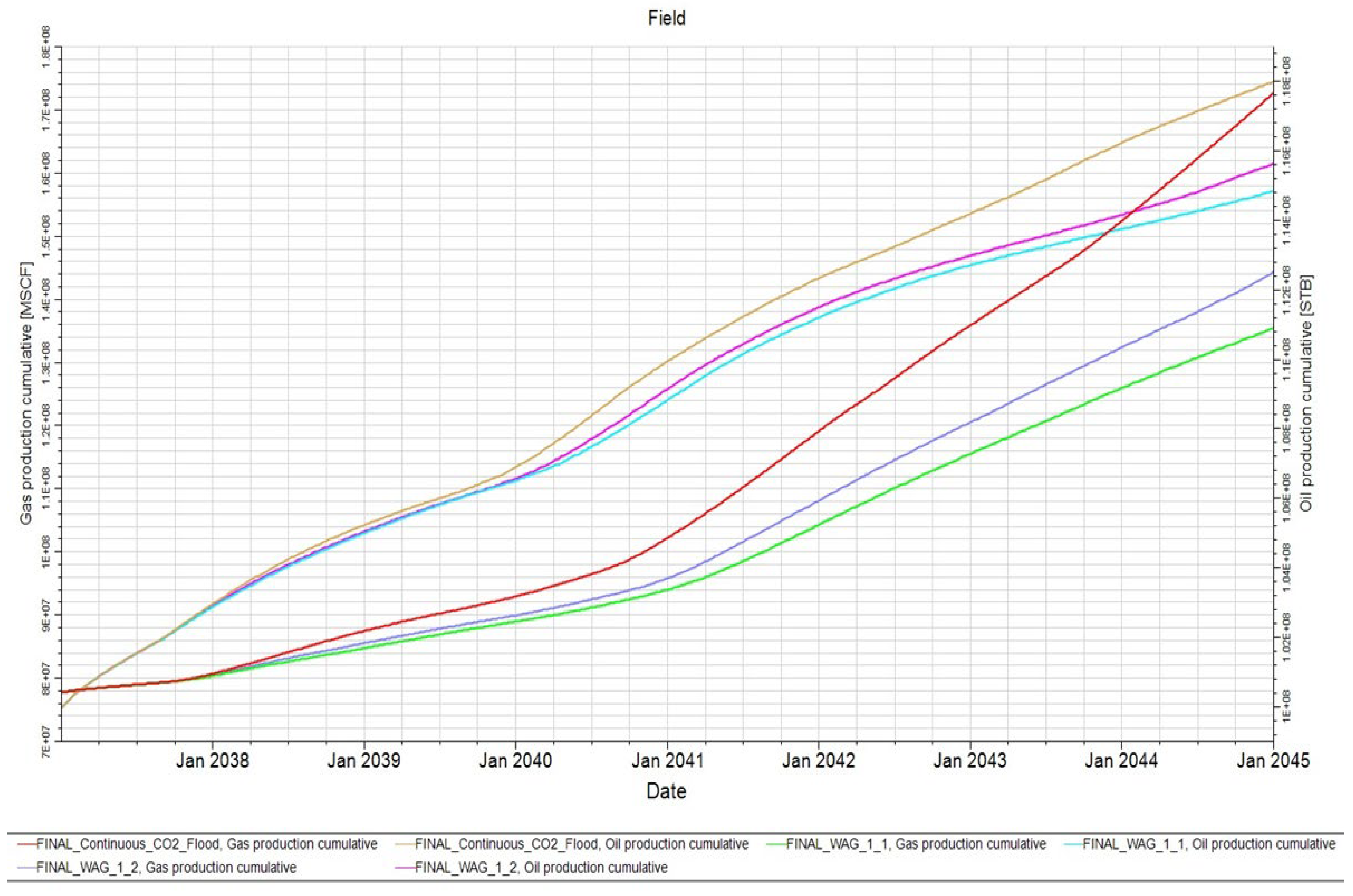

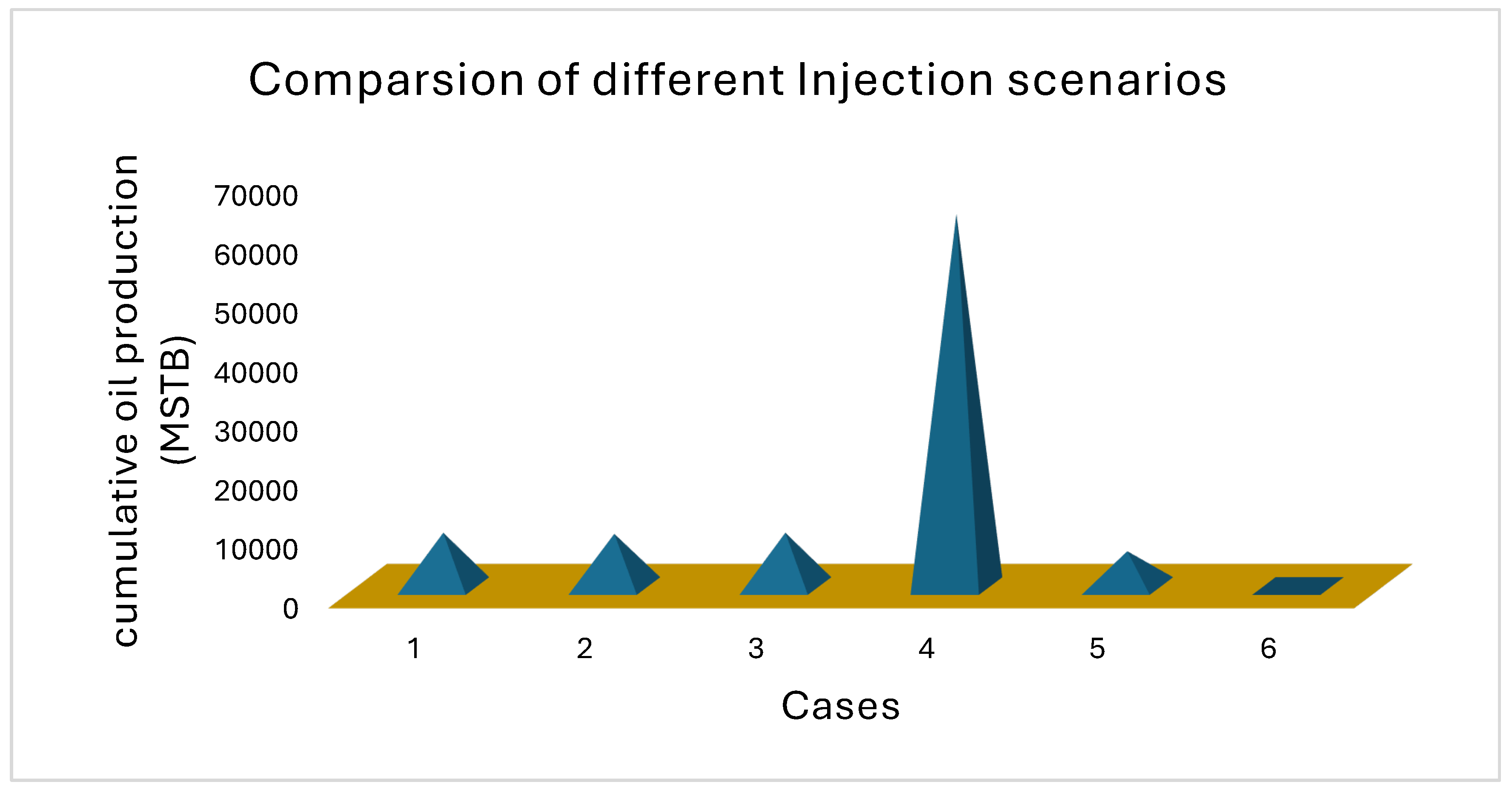

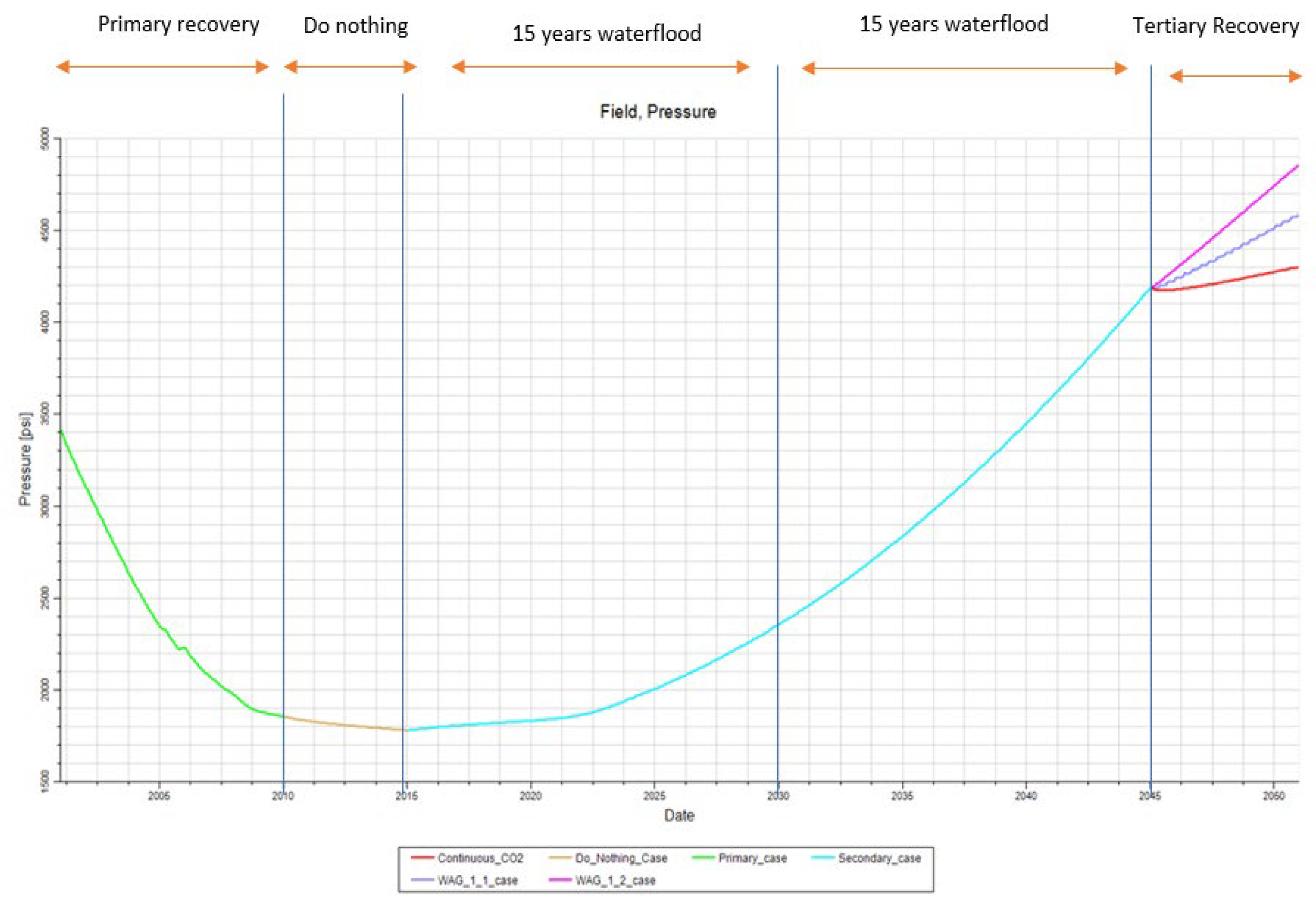

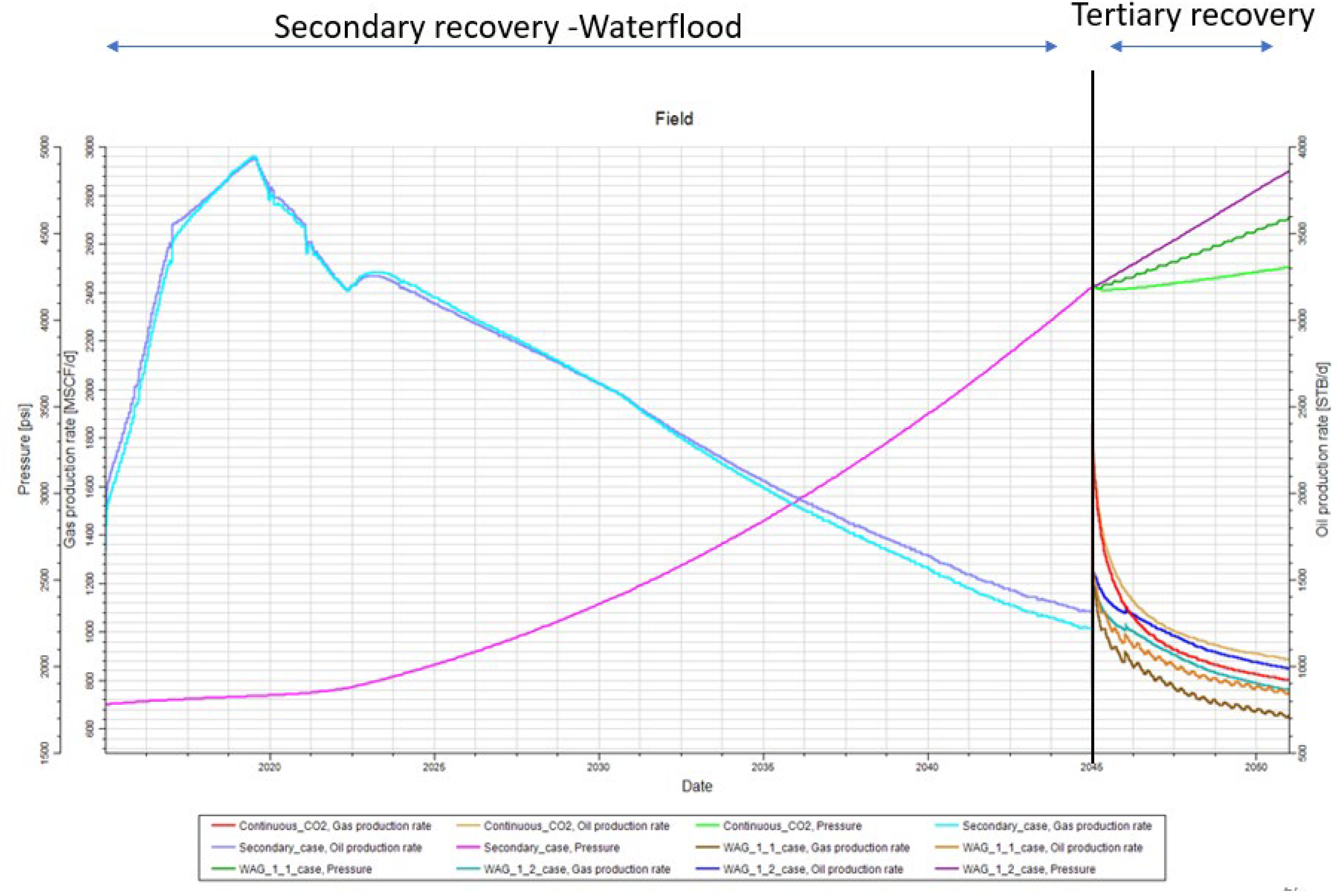

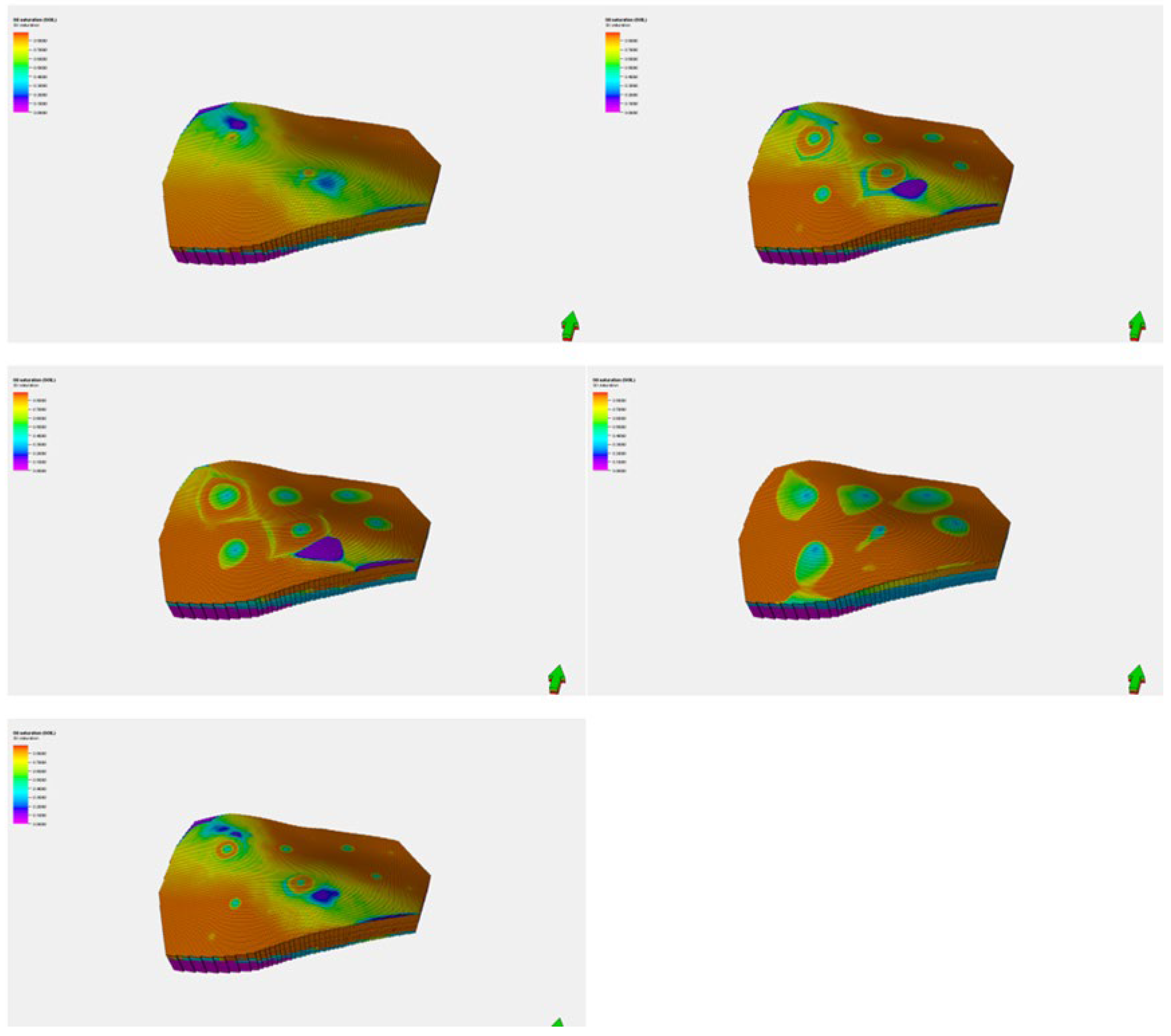

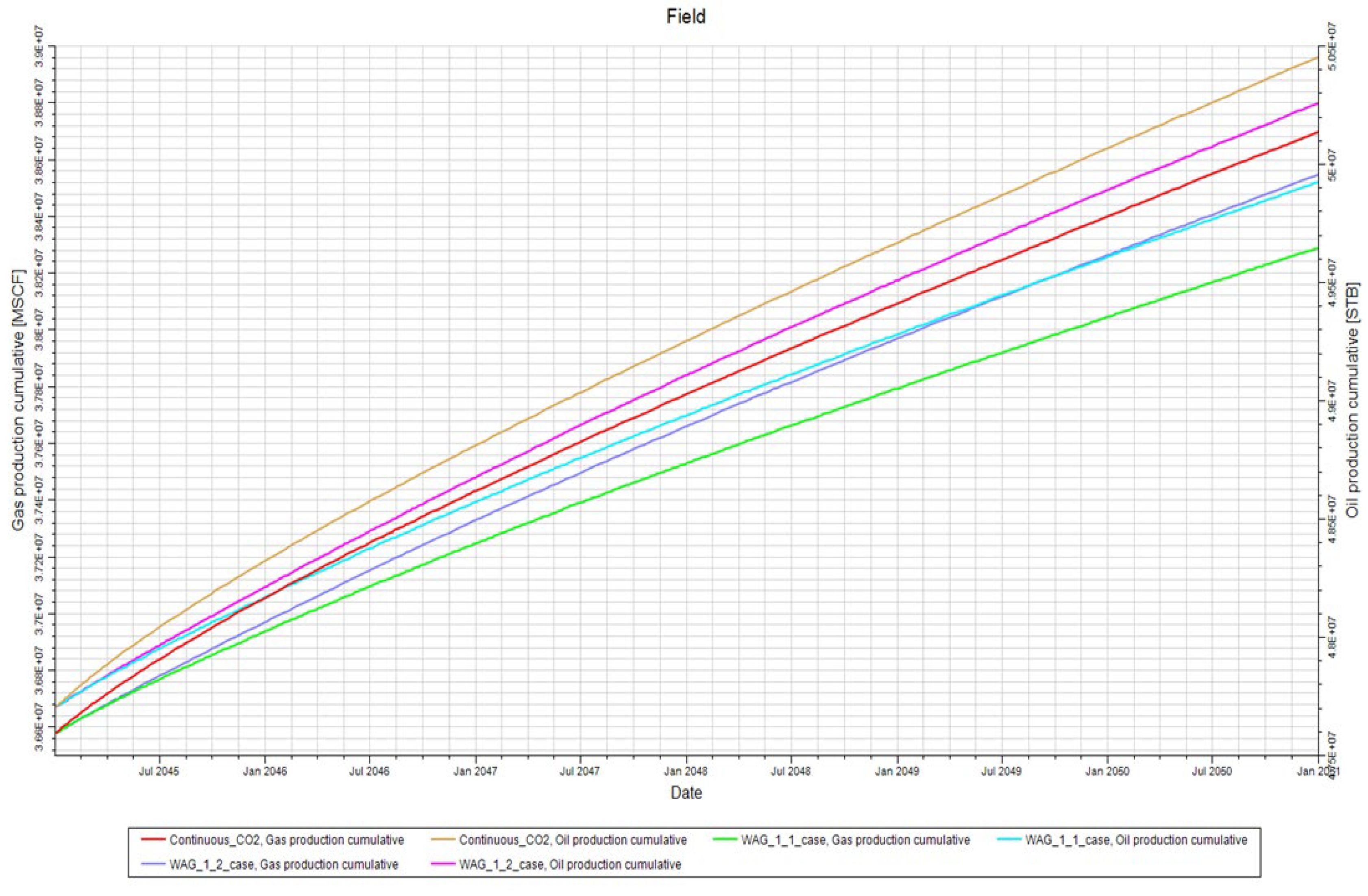

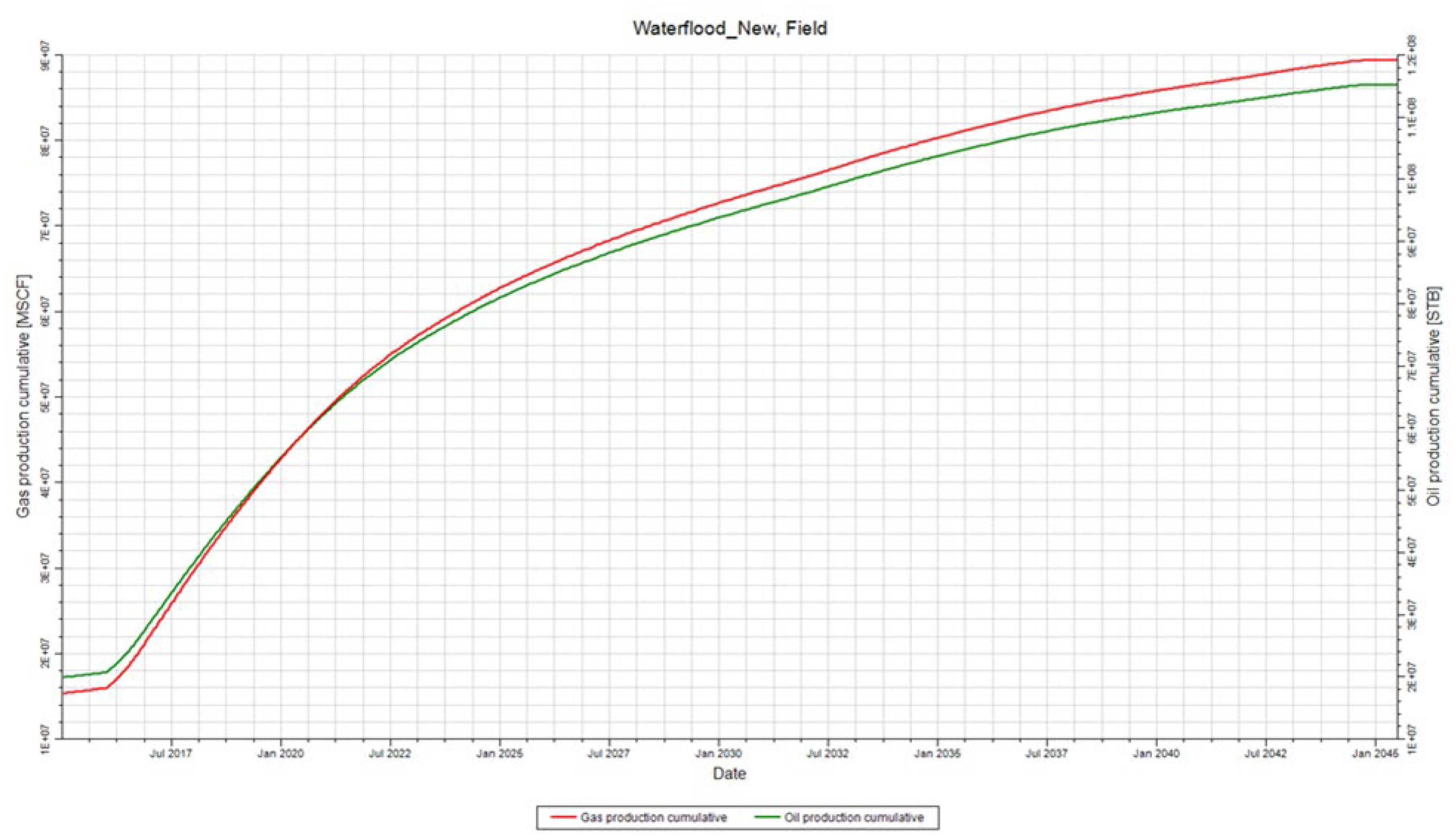

3.4. Scenario 1. Development Strategy Comparison- 3 injectors/ 3 producers

3.5. Scenario 2. Development Strategy Comparison- Infill Wells (Five-spot inverted)

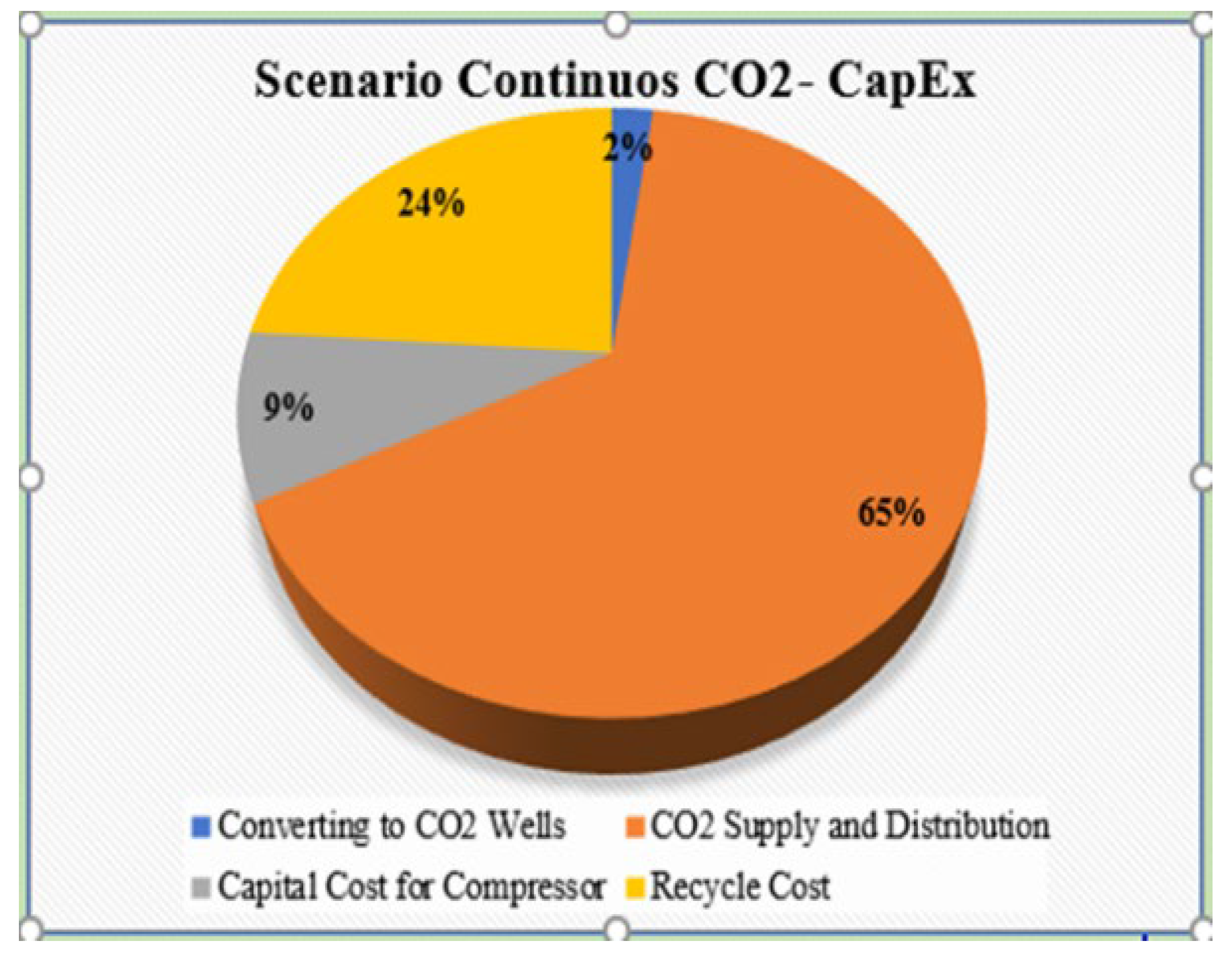

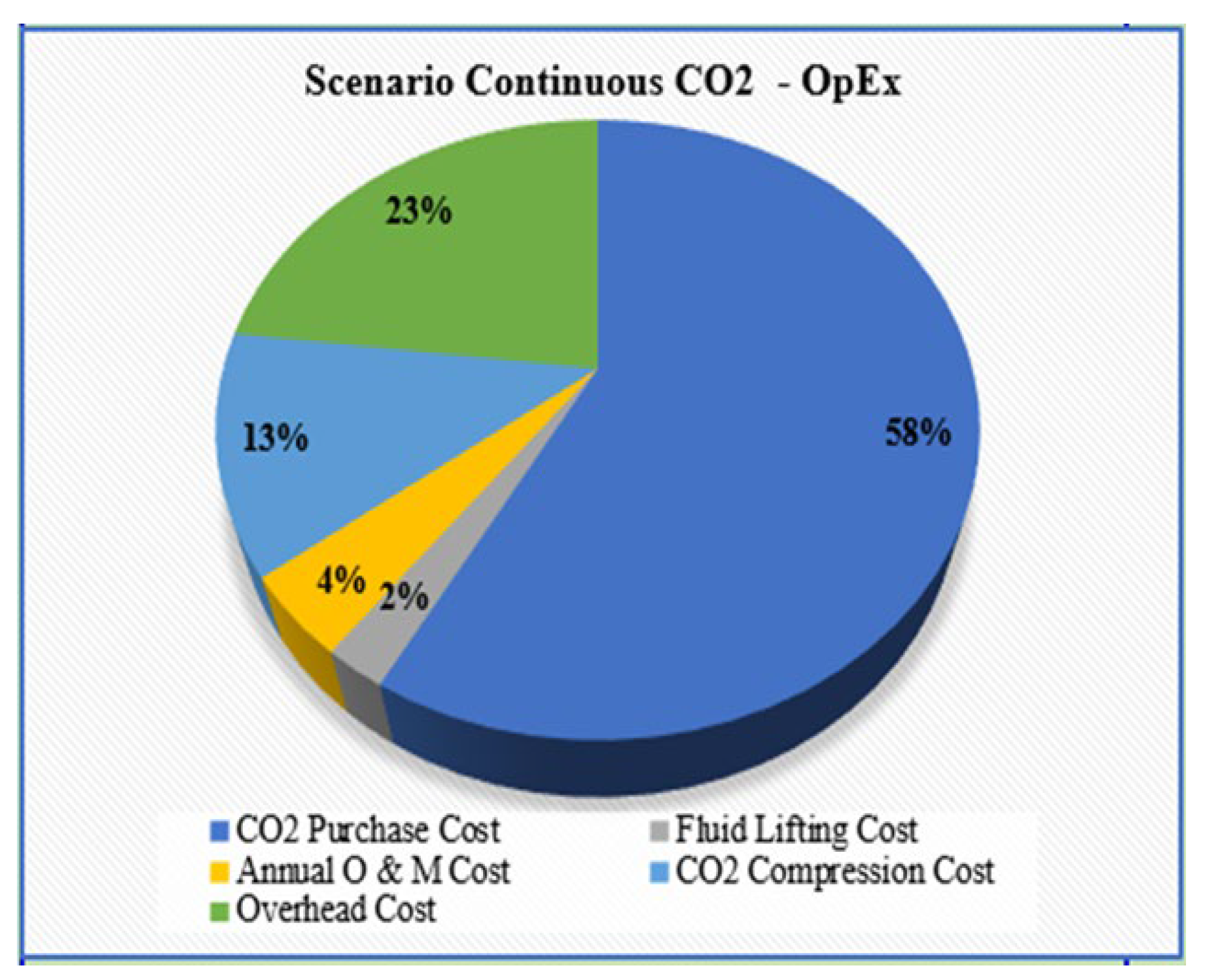

4. Economic Analysis – Scenario 1, 3 Injectors/ 3 Producers

|

CAPEX – Continuous CO2 scenario |

|

| Converting to CO2 Wells | $ 1,998,000 |

| C02 Supply and Distribution | $ 60,360,00 |

| Capital Cost for Compressor | $ 8,221,423 |

| Recycle Cost | $ 22,122,900 |

| Total | $ 70,519,323 |

| OPEX Yearly | |

| C02 Purchase Cost | $13,140,000 |

| Fluid Lifting Cost | $509,071 |

| Annual O & M Cost | $949,200 |

| CO2 Compression Cost | $2,832,811 |

| Overhead Cost | $5,229, 427.26 |

| Total | $22,660,853 |

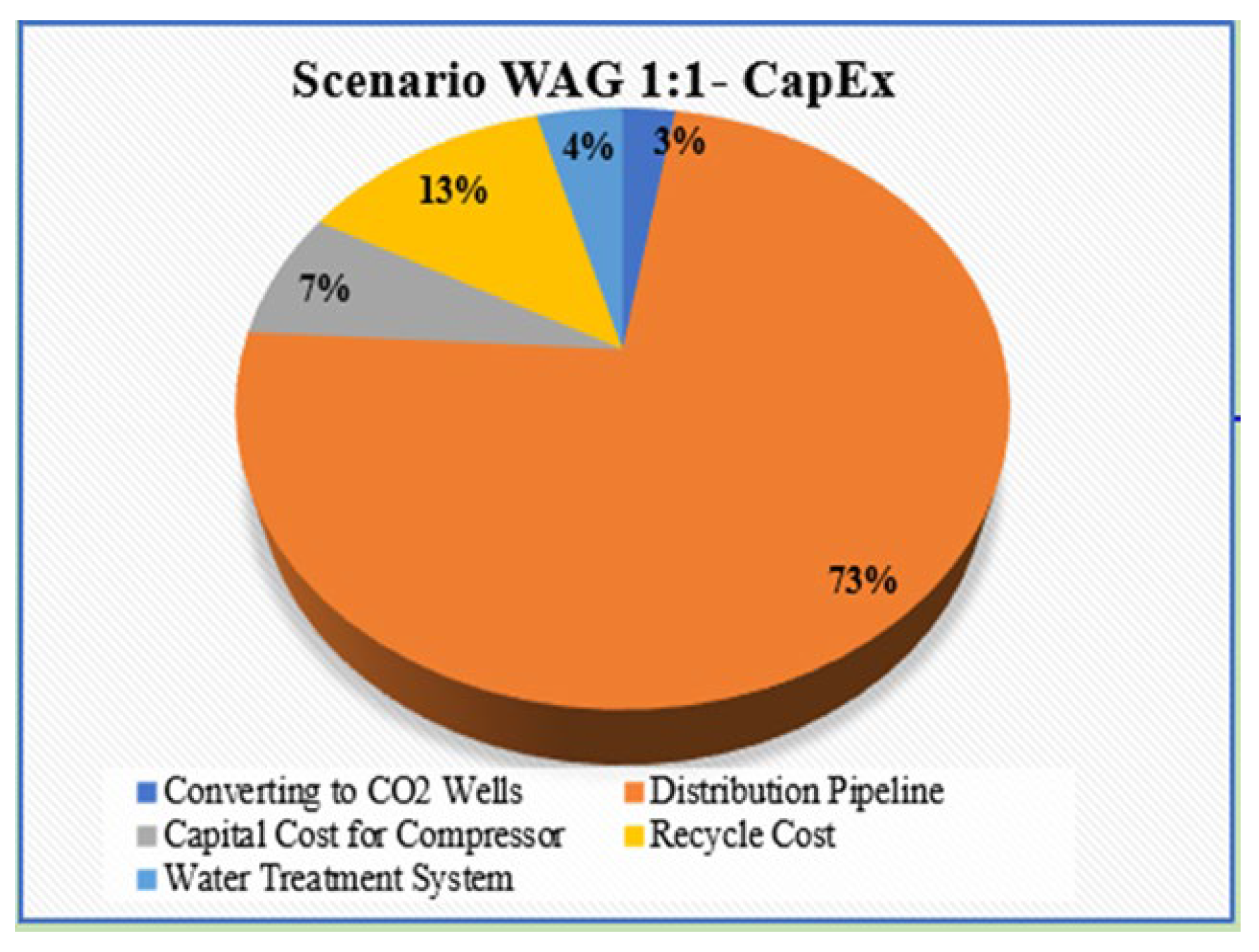

| CAPEX Yearly | |

| Converting to C02 wells | $1,998,000.00 |

| CO2 Supply and Distribution | $55,360,000.00 |

| Recycle Cost | $10,529,000.00 |

| CO2 Compression Cost | $8,330,000.00 |

| Water Treatment System | $5,229, 427.26 |

| Total | $68,988,000.00 |

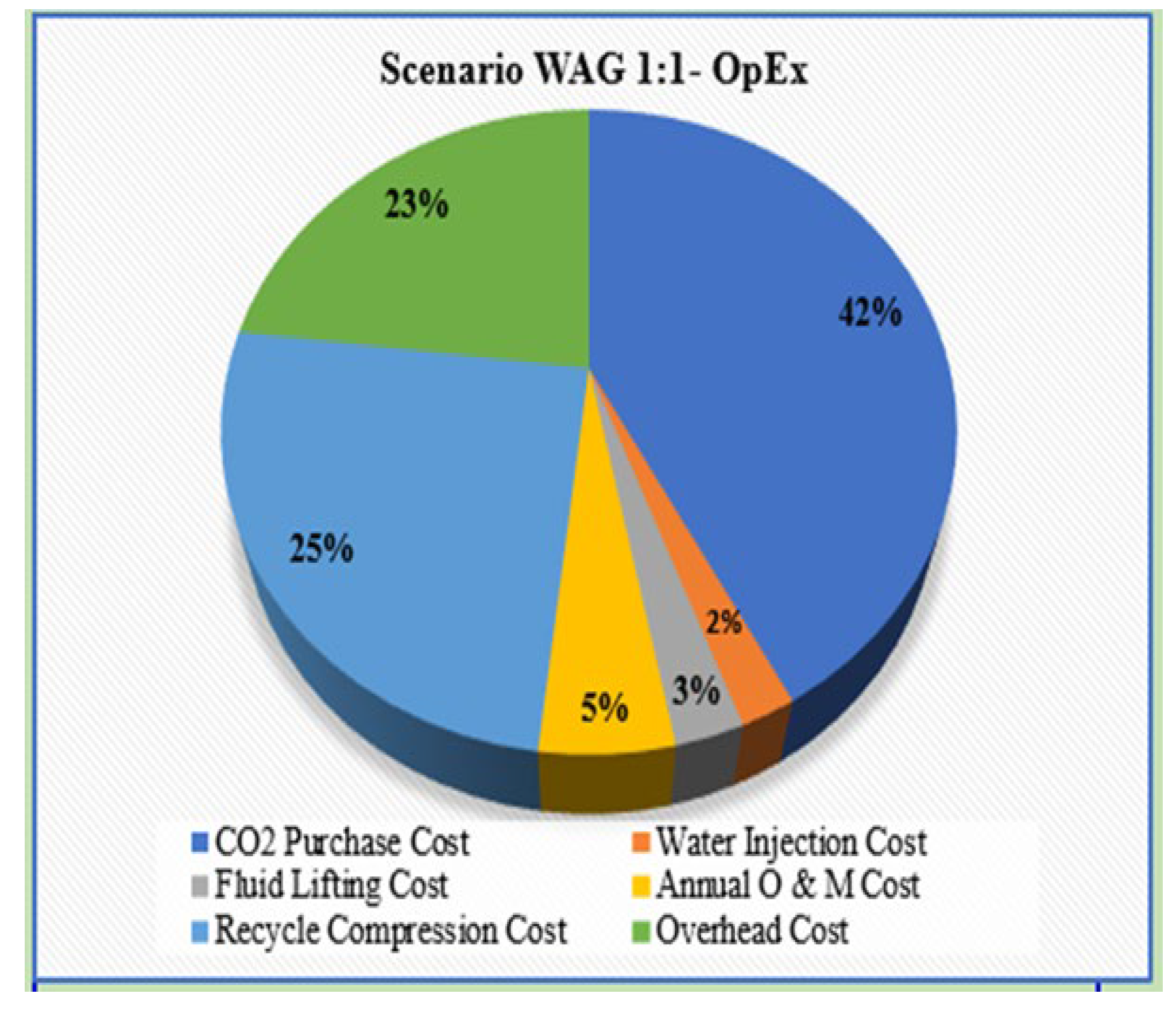

| OPEX Yearly | |

| CO2 Purchase Cost | $8,140,000.00 |

| Water Injection Cost | $395,657.00 |

| Fluid Lifting Cost | $488,698.00 |

| Annual O & M Cost | $949,200.00 |

| Recycle Compression Cost | $4,832,980.00 |

| Overhead Cost | 4,441,960.50 |

| Total | $19,248,496.0 |

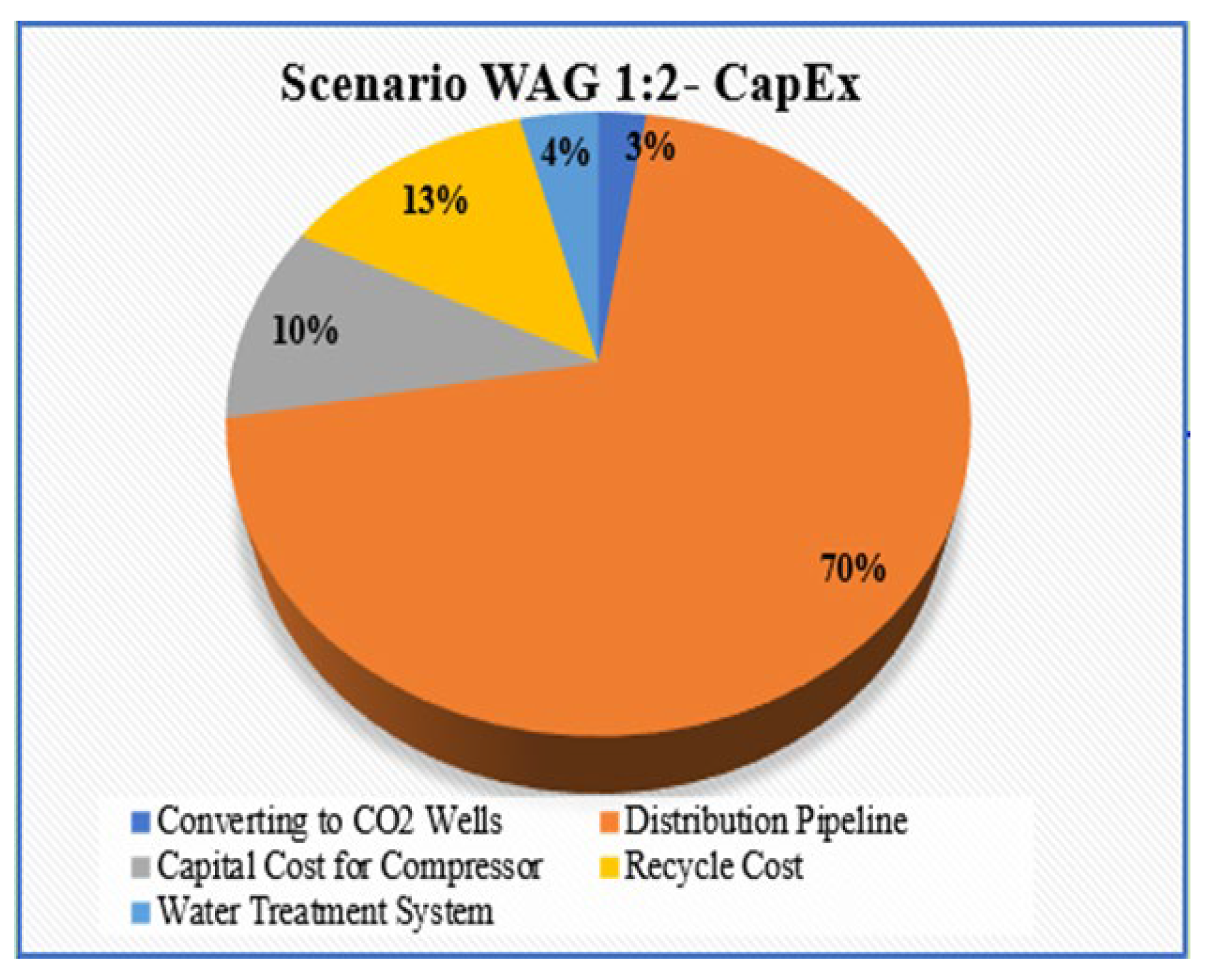

| CAPEX Yearly | |

| Converting to CO2 Wells | $1,998,000.00 |

| CO2 Supply and Distribution | $55,360,000.00 |

| Capital Cost for Compressor | $8,330,000.00 |

| Recycle Cost | $10,529,000.00 |

| Water Treatment System | $3,300,000.00 |

| Total | $68,988,000.00 |

| OPEX Yearly | |

| CO2 Purchase Cost | $10,140,000.00 |

| Water Injection Cost | $395,657.00 |

| Fluid Lifting Cost | $508,698.00 |

| Annual O & M Cost | $949,200.00 |

| Recycle Compression Cost | $4,832,980.00 |

| Overhead Cost | 5,047,960.50 |

| Total | $21,874,496.00 |

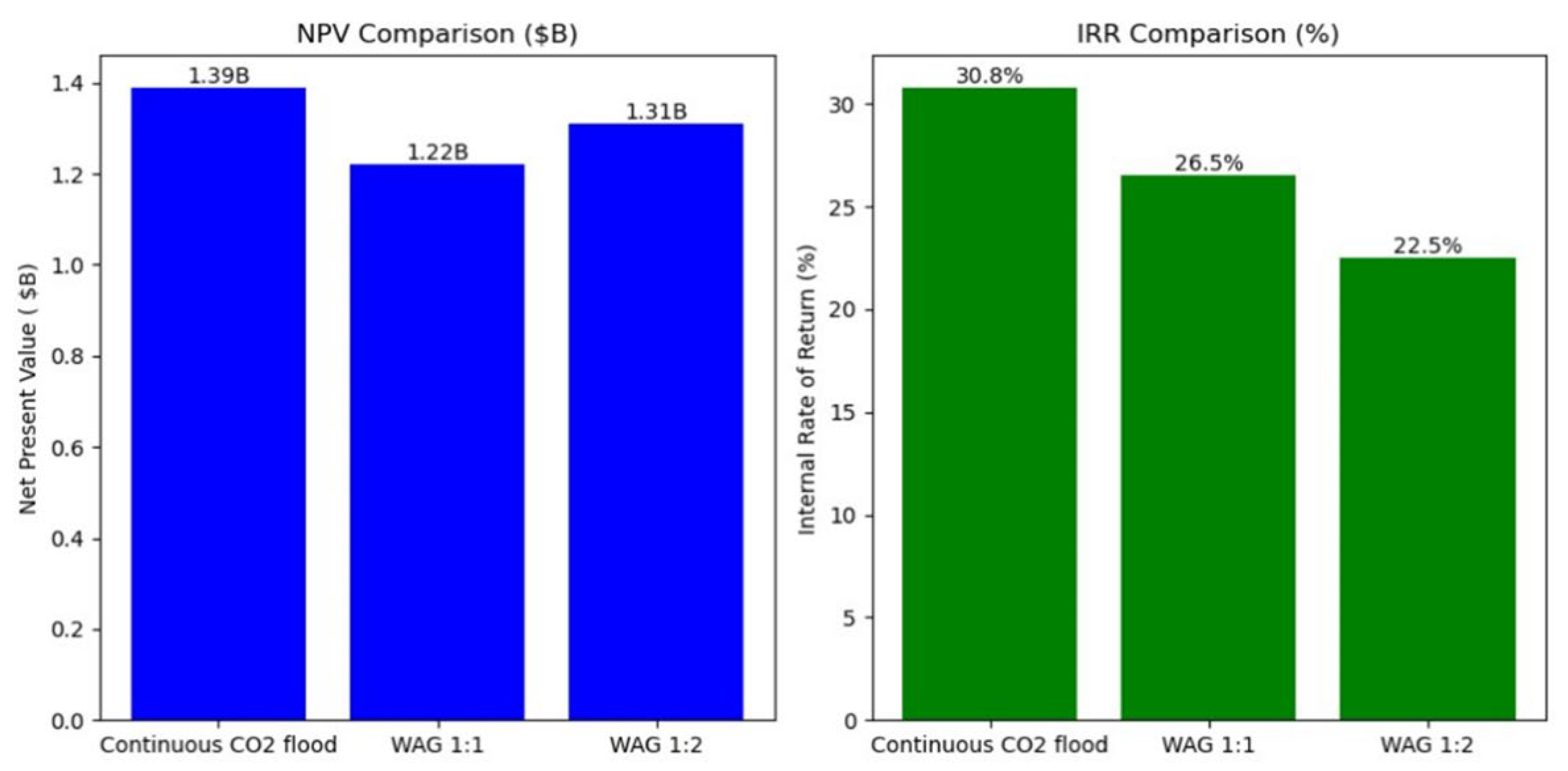

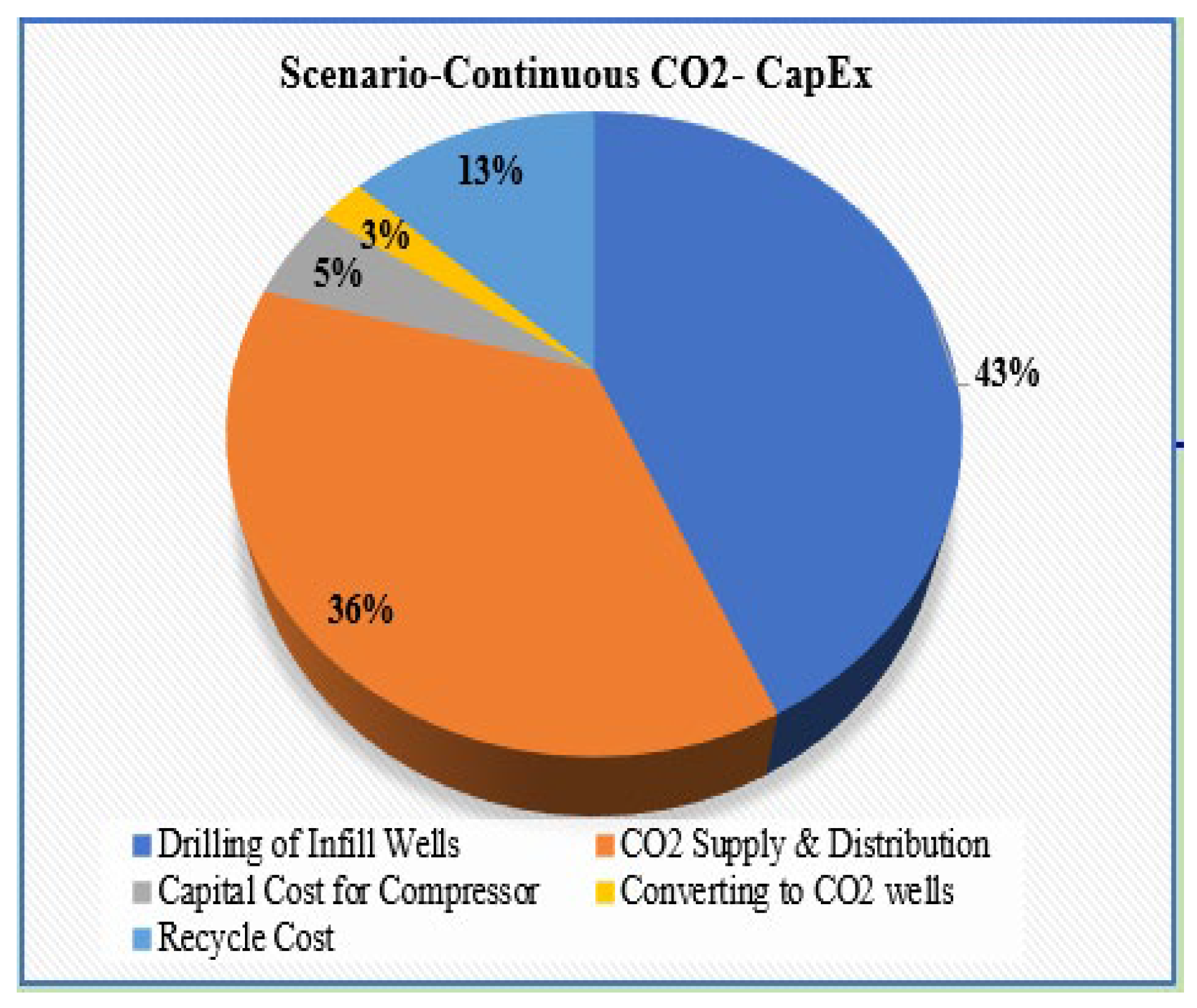

4.1. Economic Analysis – Scenario 2, 12 Injectors / 6 Producers

| CAPEX – Continuous CO2 | scenario |

| Drilling of Infill Wells | $ 72,000,000.00 |

| C02 Supply and Distribution | $ 60,360,000.00 |

| Capital Cost for Compressor | $ 8,330,000.00 |

| Converting to CO2 wells | $ 4,050,000.00 |

| Recycle Cost | 22,125,000.00 |

| Total | $ 162,815,000.00 |

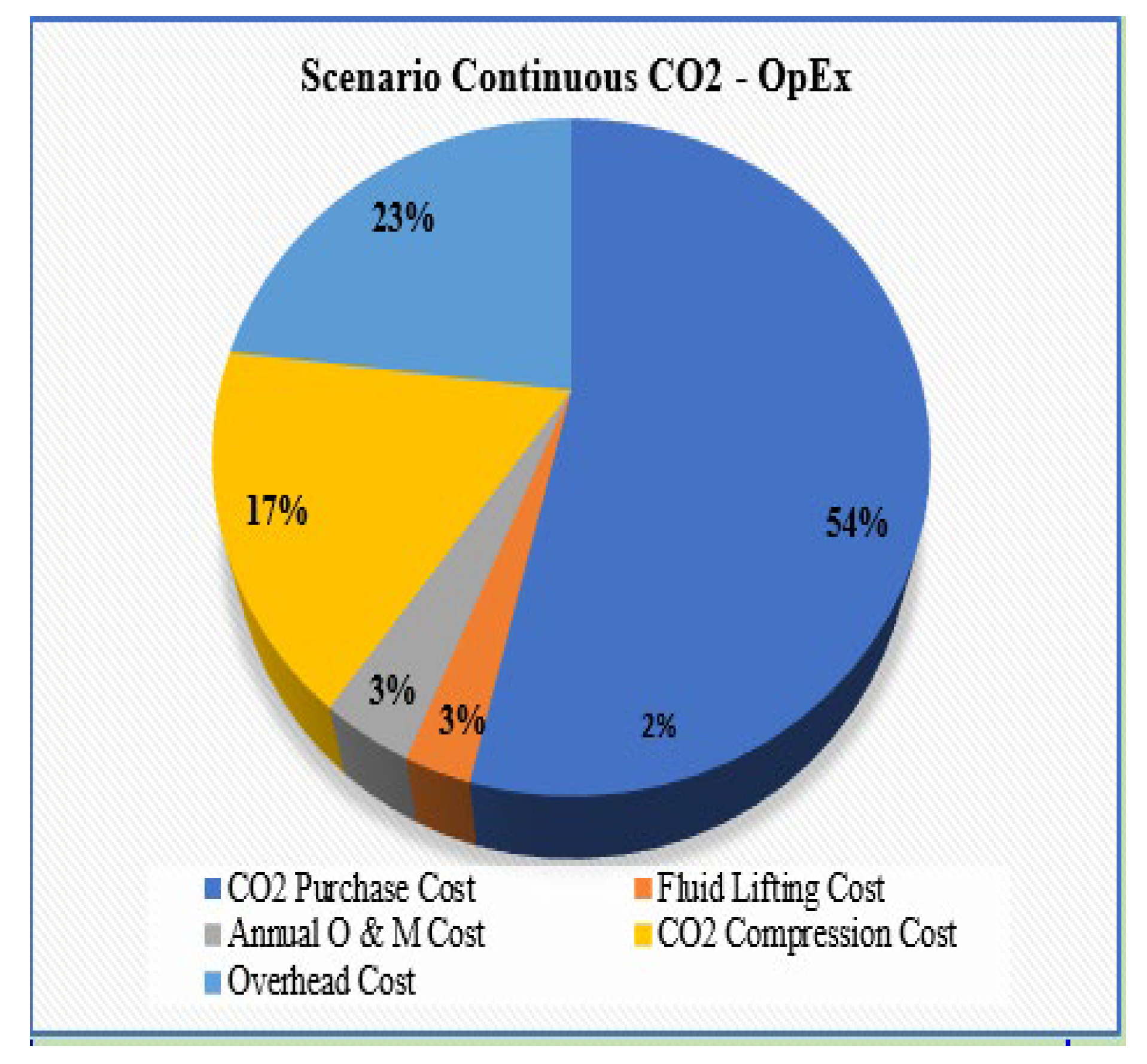

| OPEX Yearly | |

| CO2 Purchase Cost | $15,140,000.00 |

| Water Injection Cost | $395,657.00 |

| Fluid Lifting Cost | $708,698.00 |

| Annual O & M Cost | $989,200.00 |

| Recycle Compression Cost | $4,832,980.00 |

| Overhead Cost | $6,501,263.40 |

| Total | $28,172,141.00 |

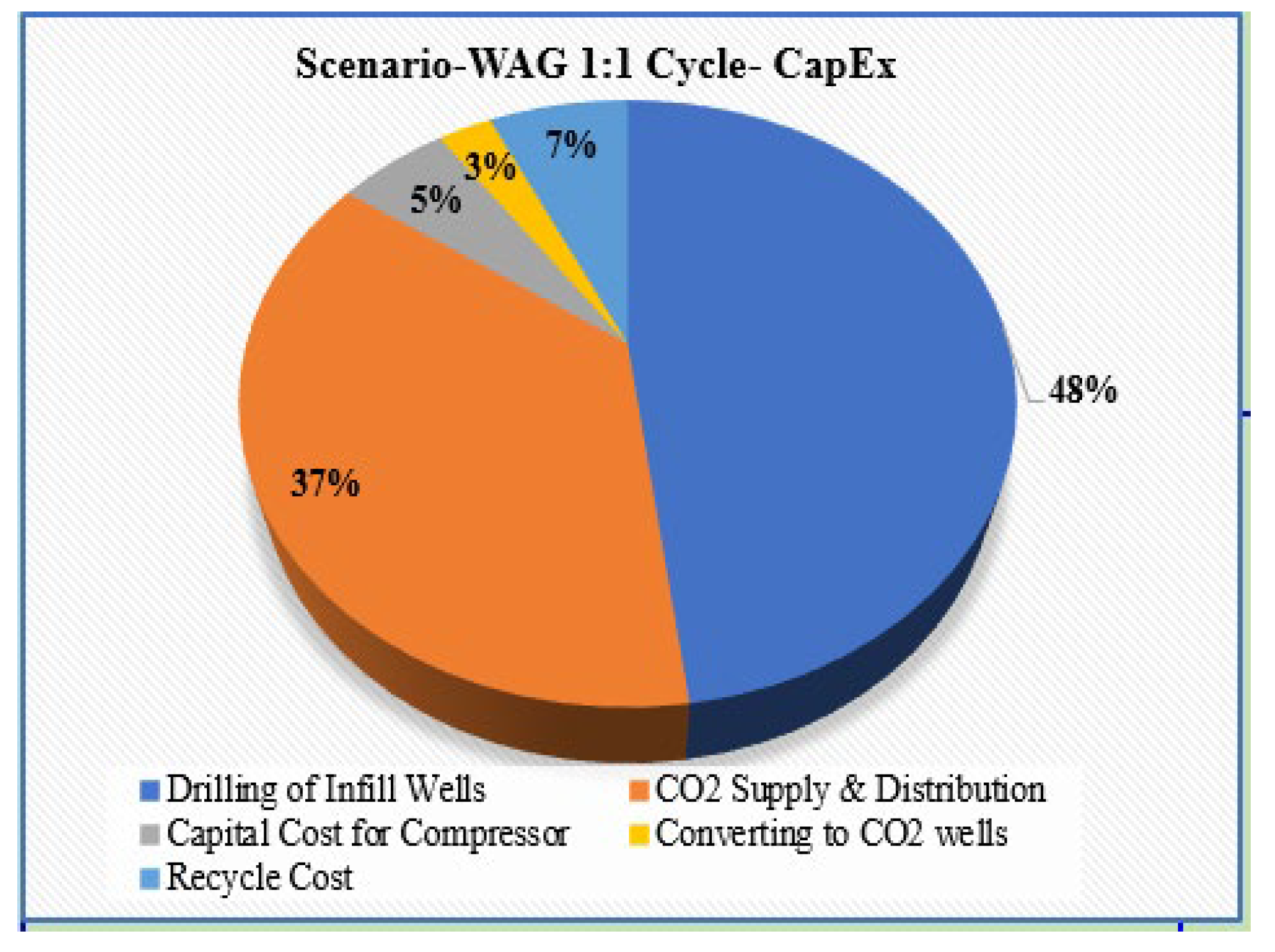

| CAPEX – WAG | scenario |

| Drilling of Infill Wells | $ 72,000,000.00 |

| C02 Supply and Distribution | $ 55,360,000.00 |

| Capital Cost for Compressor | $ 8,330,000.00 |

| Converting to CO2 wells | $ 4,050,000.00 |

| Recycle Cost | 22,125,000.00 |

| Total | $ 146,219,000.00 |

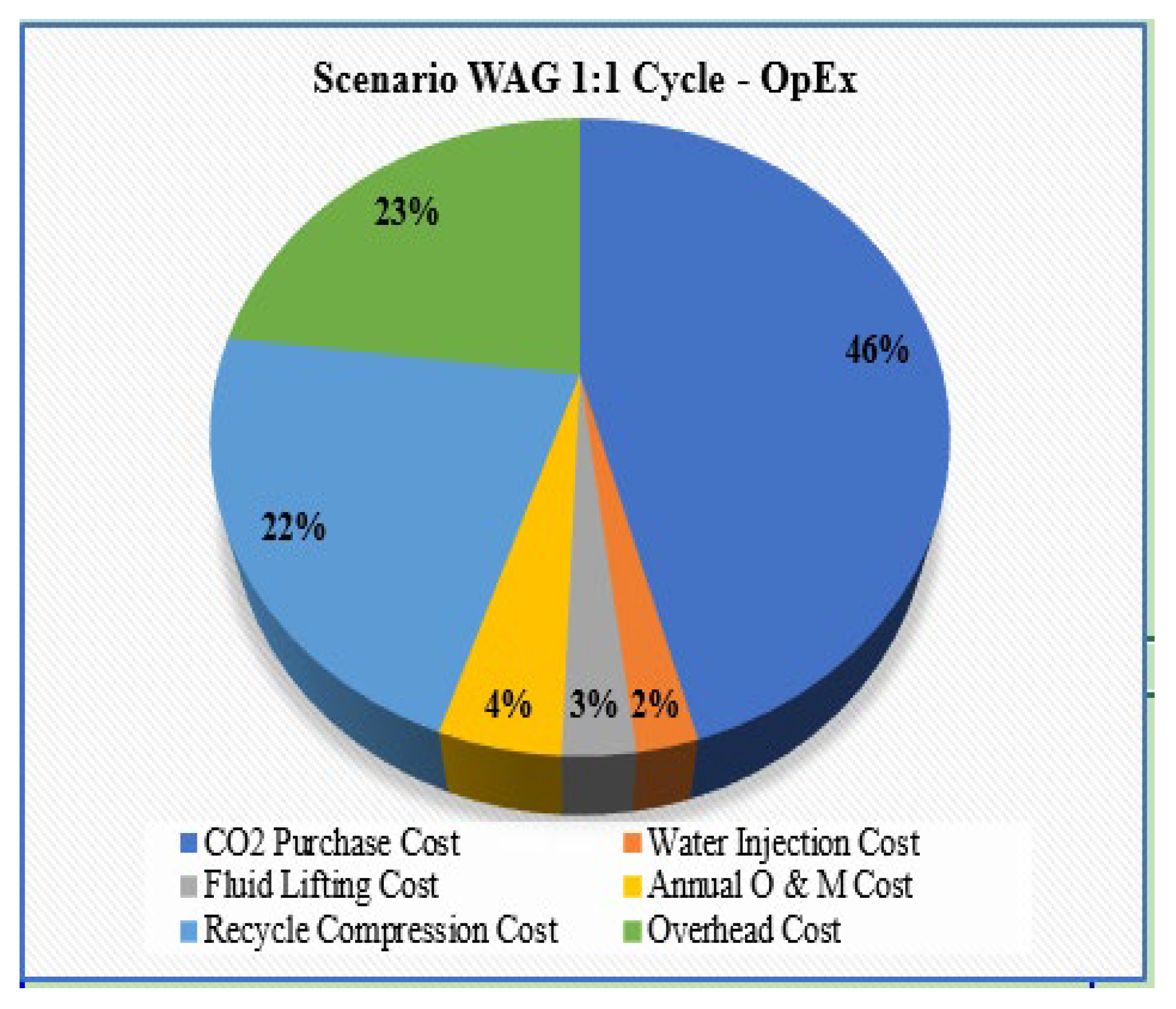

| OPEX Yearly | |

| CO2 Purchase Cost | $10,140,000.00 |

| Water Injection Cost | $495,657.00 |

| Fluid Lifting Cost | $588,698.00 |

| Annual O & M Cost | $989,200.00 |

| Recycle Compression Cost | $4,832,980.00 |

| Overhead Cost | $5,113,960.50 |

| Total | $22,160,496.00 |

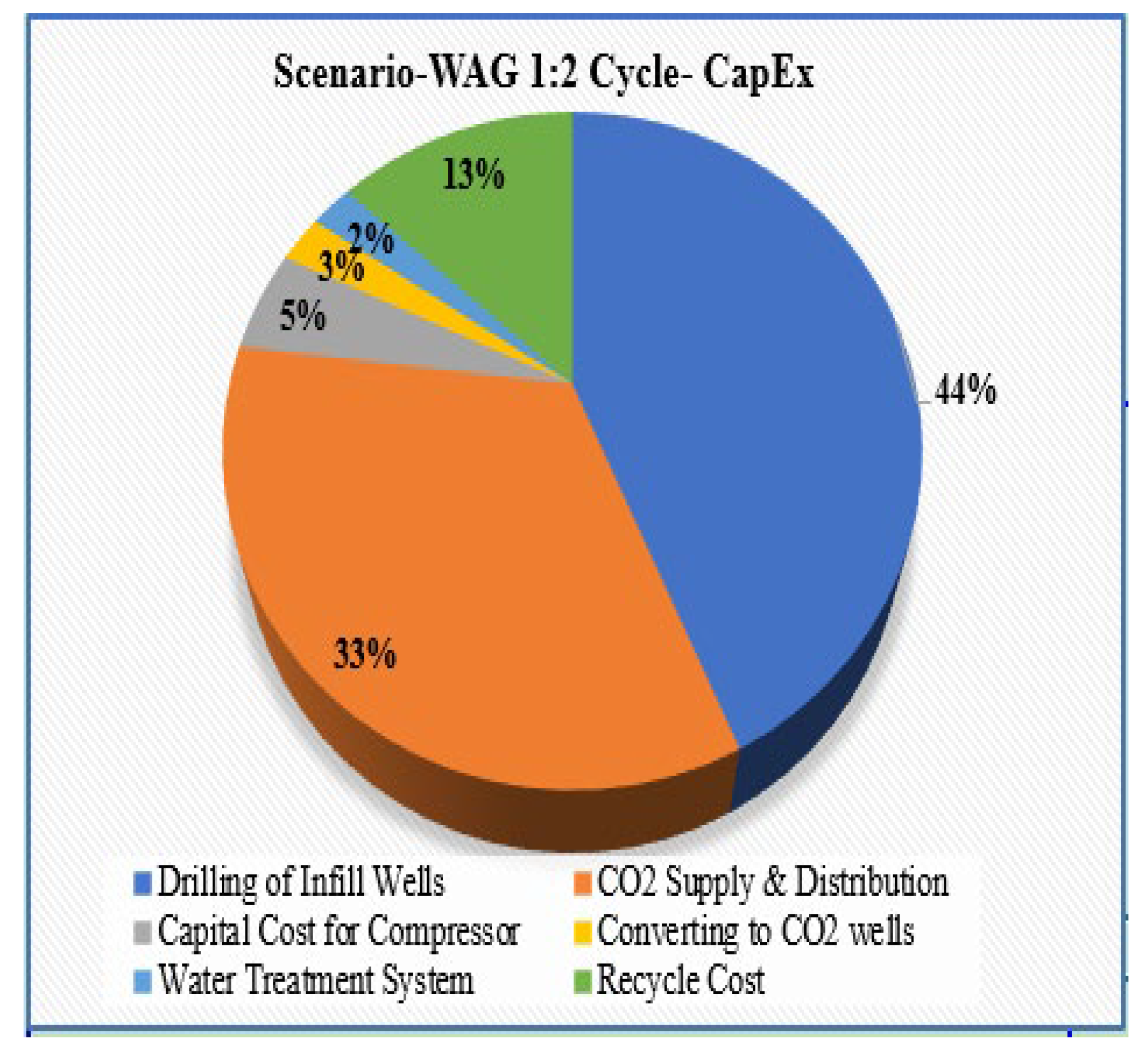

| CAPEX – WAG | scenario |

| Drilling of Infill Wells | $ 72,000,000.00 |

| C02 Supply and Distribution | $ 55,360,000.00 |

| Capital Cost for Compressor | $ 8,330,000.00 |

| Converting to CO2 wells | $ 4,050,000.00 |

| Water treatment system | $ 3,800,000.00 |

| Recycle Cost | 22,125,000.00 |

| Total | $ 157,815,000.00 |

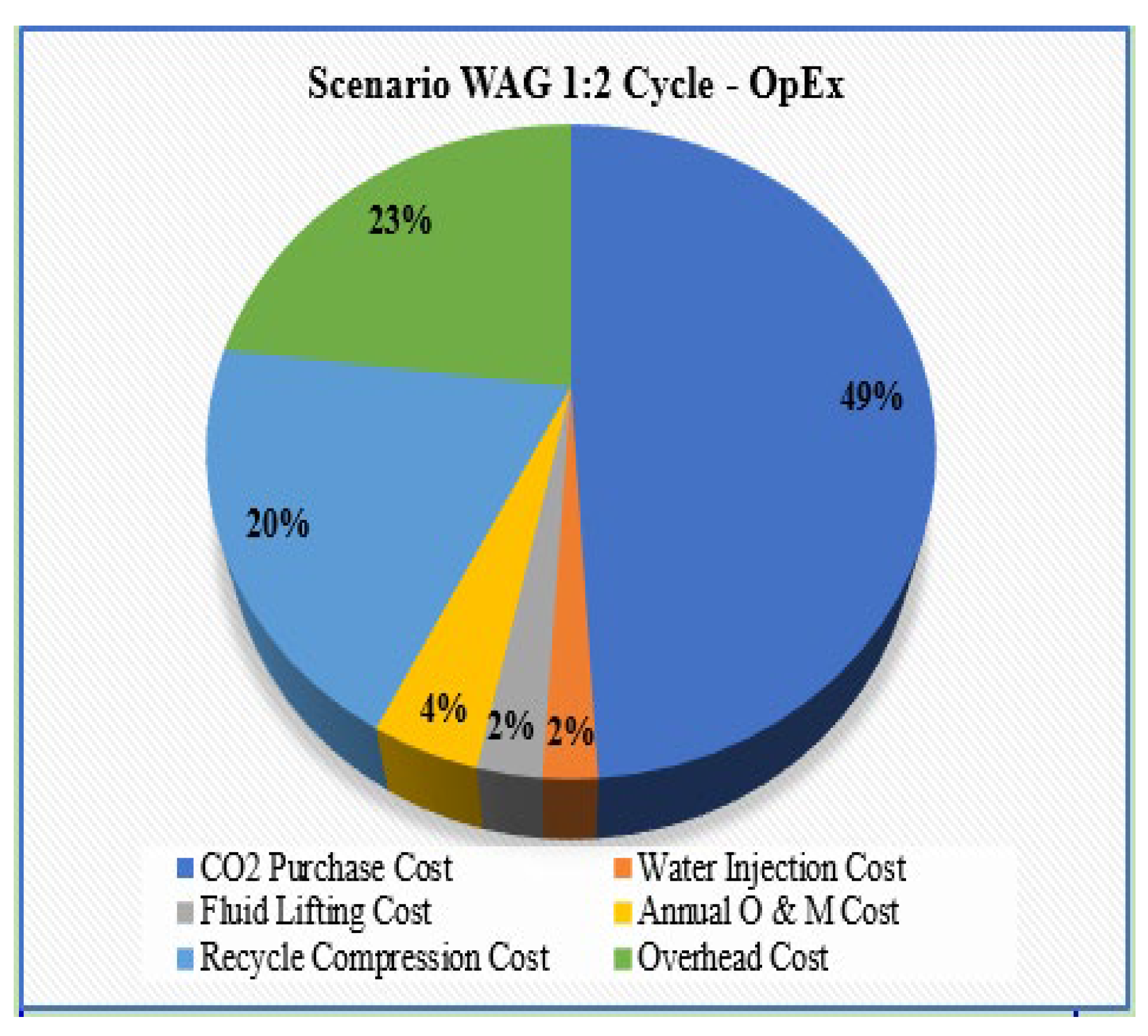

| OPEX Yearly | |

| CO2 Purchase Cost | $12,140,000.00 |

| Water Injection Cost | $495,657.00 |

| Fluid Lifting Cost | $588,698.00 |

| Annual O & M Cost | $989,200.00 |

| Recycle Compression Cost | $4,832,980.00 |

| Overhead Cost | $5,713,960.50 |

| Total | $24,760,496.00 |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perera, M.S.A.; Gamage, R.P.; Rathnaweera, T.D.; Ranathunga, A.S.; Koay, A.; Choi, X. A Review of CO2-Enhanced Oil Recovery with a Simulated Sensitivity Analysis. Energies 2016, 9, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Sampaio, M.A.; Ojha, K.; Hoteit, H.; Mandal, A. Fundamental aspects, mechanisms and emerging possibilities of CO2 miscible flooding in enhanced oil recovery: A review. Fuel 2022, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplygin, V.V.; Poplygina, I.S.; Mordvinov, V.A. Influence of Reservoir Properties on the Velocity of Water Movement from Injection to Production Well. Energies 2022, 15, 7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPE_39657”.

- Morrow, “Wettability and Its Effect on Oil Recovery,” 1990.

- Yuan, S.; Han, H.; Wang, H.; Luo, J.; Wang, Q.; Lei, Z.; Xi, C.; Li, J. Research progress and potential of new enhanced oil recovery methods in oilfield development. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 963–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. E. Greenberg, “ILLINOIS BASIN DECATUR PROJECT Final Report An Assessment of Geologic Carbon Sequestration Options in the Illinois Basin: Phase III.

- CMTC-151027-PP NETL CO 2 Injection and Storage Cost Model,” 2012.

- Bikkina, P.; Wan, J.; Kim, Y.; Kneafsey, T.J.; Tokunaga, T.K. Influence of wettability and permeability heterogeneity on miscible CO2 flooding efficiency. Fuel 2016, 166, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katterbauer, K.; Arango, S.; Sun, S.; Hoteit, I. Multi-data reservoir history matching for enhanced reservoir forecasting and uncertainty quantification. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 128, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Cui, S.; Shang, G.; Reynolds, A.C.; Guo, Z.; Li, H.A. History matching and production optimization of water flooding based on a data-driven interwell numerical simulation model. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 31, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwechungura, R.W.; Dadashpour, M.; Kleppe, J. Advanced History Matching Techniques Reviewed. SPE Middle East Oil and Gas Show and Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, BahrainDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Abdullah, N.; Hasan, N. The implementation of Water Alternating (WAG) injection to obtain optimum recovery in Cornea Field, Australia. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2021, 11, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghnejad, S.; Manteghian, M.; Ruzsaz, H. Simulation Optimization of Water Alternating Gas (WAG) Process under Operational Constraints: A Case Study in the Persian Gulf. Sci. Iran. 2019, 26, 3431–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, V.; Bidarigh, M.; Bahrami, P. Experimental Study and Performance Investigation of Miscible Water-Alternating-CO2Flooding for Enhancing Oil Recovery in the Sarvak Formation. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. – Rev. d’IFP Energies Nouv. 2017, 72, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.; Nguyen, S.; Ampomah, W.; Acheampong, S.A.; Hama, A.; Amosu, A.; Koray, A.-M.; Kubi, E.A. A Comparison of Water Flooding and CO2-EOR Strategies for the Optimization of Oil Recovery: A Case Study of a Highly Heterogeneous Sandstone Formation. Gases 2024, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. A. Mou, “A PROJECT PROPOSAL On ‘“Simulation on oil production from steam flooding process in heavy oil-sand reservoirs.

- Wang, L.; Tian, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, C.; Yao, B.; Wang, S.; Winterfeld, P.H.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Advances in improved/enhanced oil recovery technologies for tight and shale reservoirs. Fuel 2017, 210, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Almehaideb, R.; Al-Khanbashi, A.S.; Abdulkarim, M.; A Ali, M. EOS tuning to model full field crude oil properties using multiple well fluid PVT analysis. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2000, 26, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunda, D.; Ampomah, W.; Grigg, R.; Balch, R. Reservoir Fluid Characterization for Miscible Enhanced Oil Recovery. Carbon Management Technology Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE;

| Model | Dimension, ft nI | nJ nK Total Cells |

| I J | ||

| Upscaled Model | 100 100 216 | 162 172 207690 |

| Criteria | Optimum Condition |

| Depth, ft | 2500 - 3000 |

| Reservoir Temperature, 0F | < 120 |

| Reservoir pressure, psi | > 3000 |

| Total dissolved Solids (TDS) | < 10000mg/L |

| Oil gravity | Medium to light (27- 390 API |

| Oil viscosity, cp | < 10 |

| Reservoir Type | Carbonate reservoir preferred than sandstone |

| Minimum Miscibility Pressure, psi | 1300 -2500 |

| Oil saturation | >20% |

| Net Pay Thickness, ft | 75-137 |

| Porosity | >7% |

| Permeability | >10mD |

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 Case 4 Case 5 Case 6 | |

| Number of Injectors Cumulative Production (MSTB) Incremental Oil Recovery (%) Injection Mode |

3 | 3 | 3 2 2 2 |

| 9043.8 3.82 WAG |

8852 3.73 Continuous Miscible CO2 |

9043.8 63109.4 5907.4 0.1 3.82 26.63 2.49 0 Waterflood WAG Continuous Waterflood Miscible CO2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).