Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search and Selection Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Activation Likelihood Estimation

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

3.1.1. Hypoactivation and Hyperactivation Pooled Together in the Whole Sample (Short-Term & Long-Term Abstinence)

3.1.2. Hypoactivated Foci in the Whole Sample

3.1.3. Hyperactivated Foci in the Whole Sample

3.1.4. Hypoactivation and Hyperactivation Pooled Together in the Short-Term Abstinent Sample

3.1.5. Hypoactivated Foci in the Short-Term Abstinent Sample

3.1.6. Hyperactivated Foci in the Short-Term Abstinent Sample

3.1.7. Hypoactivation and Hyperactivation Pooled Together in the Long-Term Abstinent Sample

3.1.8. Hypoactivated Foci in the Long-Term Abstinent Sample

3.1.9. Hyperactivated Foci in the Long-Term Abstinent Sample

3.2. Sub-Analyses on Socio-Demographic Variables, MRI Parameters and Task Types

4. Discussion

Author Contributors

Acknowledgments

References

- Meyer, J.; Farrar, A.M.; Bienzonski, D.; Yates, J.R. Psychopharmacology, Drugs, the Brain, and Behavior, 4th ed.; Press, O.U., Ed.; 2022.

- WHO. Over 3 million annual deaths due to alcohol and drug use, majority among men. 25 June 2024.

- Chikritzhs, T.; Livingston, M. Alcohol and the Risk of Injury. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, J.J.; Gonzales, K.R.; Bouchery, E.E.; Tomedi, L.E.; Brewer, R.D. 2010 National and State Costs of Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Am J Prev Med 2015, 49, e73–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorrisen, M.M.; Bonsaksen, T.; Hashemi, N.; Kjeken, I.; van Mechelen, W.; Aas, R.W. Association between alcohol consumption and impaired work performance (presenteeism): a systematic review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, H.F.J. Alcohol and Human Health: What Is the Evidence? Annu Rev Food Sci Technol 2020, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palzes, V.A.; Parthasarathy, S.; Chi, F.W.; Kline-Simon, A.H.; Lu, Y.; Weisner, C.; Ross, T.B.; Elson, J.; Sterling, S.A. Associations Between Psychiatric Disorders and Alcohol Consumption Levels in an Adult Primary Care Population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2020, 44, 2536–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, H.; Tan, G.C.; Ibrahim, S.F.; Shaikh, M.F.; Mohamed, I.N.; Mohamed, R.M.P.; Hamid, A.A.; Ugusman, A.; Kumar, J. Alcohol Use Disorder, Neurodegeneration, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Disease: Interplay Between Oxidative Stress, Neuroimmune Response and Excitotoxicity. Front Cell Neurosci 2020, 14, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, S.; Mackey, S.; Cousijn, J.; Foxe, J.J.; Heinz, A.; Hester, R.; Hutchinson, K.; Kiefer, F.; Korucuoglu, O.; Lett, T.; et al. Predicting alcohol dependence from multi-site brain structural measures. Hum Brain Mapp 2022, 43, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarri, X.; Afzali, M.H.; Lavoie, J.; Sinha, R.; Stein, D.J.; Momenan, R.; Veltman, D.J.; Korucuoglu, O.; Sjoerds, Z.; van Holst, R.J.; et al. How do substance use disorders compare to other psychiatric conditions on structural brain abnormalities? A cross-disorder meta-analytic comparison using the ENIGMA consortium findings. Hum Brain Mapp 2022, 43, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Meng, Y.J.; Li, X.J.; Zhang, C.; Liang, S.; Li, M.L.; Guo, W.; QiangWang; et al. Lower regional grey matter in alcohol use disorders: evidence from a voxel-based meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Tian, F.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, J.; Chen, T.; Wang, S.; Jia, Z.; Gong, Q. Cortical and subcortical gray matter shrinkage in alcohol-use disorders: a voxel-based meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016, 66, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pando-Naude, V.; Toxto, S.; Fernandez-Lozano, S.; Parsons, C.E.; Alcauter, S.; Garza-Villarreal, E.A. Gray and white matter morphology in substance use disorders: a neuroimaging systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spindler, C.; Mallien, L.; Trautmann, S.; Alexander, N.; Muehlhan, M. A coordinate-based meta-analysis of white matter alterations in patients with alcohol use disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnig, M.A.; Tonigan, J.S.; Yeo, R.A.; Thoma, R.J.; McCrady, B.S. White matter volume in alcohol use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addict Biol 2013, 18, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoto, F.; Zapparoli, L.; Spinelli, G.; Scotti, G.; Paulesu, E. How the harm of drugs and their availability affect brain reactions to drug cues: a meta-analysis of 64 neuroimaging activation studies. Transl Psychiatry 2020, 10, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klugah-Brown, B.; Di, X.; Zweerings, J.; Mathiak, K.; Becker, B.; Biswal, B. Common and separable neural alterations in substance use disorders: A coordinate-based meta-analyses of functional neuroimaging studies in humans. Hum Brain Mapp 2020, 41, 4459–4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberlin, B.G.; Shen, Y.I.; Kareken, D.A. Alcohol Use Disorder Interventions Targeting Brain Sites for Both Conditioned Reward and Delayed Gratification. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Yu, S.; Cao, H.; Su, Y.; Dong, Z.; Yang, X. Neurobiological correlates of cue-reactivity in alcohol-use disorders: A voxel-wise meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021, 128, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Tian, F.; Zeng, J.; Gong, Q.; Yang, X.; Jia, Z. The brain activity pattern in alcohol-use disorders under inhibition response Task. J Psychiatr Res 2023, 163, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; You, L.; Yang, F.; Luo, Y.; Yu, S.; Yan, J.; Liu, M.; Yang, X. A meta-analysis of the neural substrates of monetary reward anticipation and outcome in alcohol use disorder. Hum Brain Mapp 2023, 44, 2841–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugré, J.R.; Orban, P.; Potvin, S. Disrupted functional connectivity of the brain reward system in substance use problems: A meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Addict Biol 2023, 28, e13257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.I.; Cieslik, E.C.; Laird, A.R.; Fox, P.T.; Radua, J.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Tench, C.R.; Yarkoni, T.; Nichols, T.E.; Turkeltaub, P.E.; et al. Ten simple rules for neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2018, 84, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagga, D.; Singh, N.; Modi, S.; Kumar, P.; Bhattacharya, D.; Garg, M.L.; Khushu, S. Assessment of lexical semantic judgment abilities in alcohol-dependent subjects: an fMRI study. J Biosci 2013, 38, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, D.; Smolka, M.N.; Klein, S.; Heinz, A.; Mann, K.; Braus, D.F. Reduced fMRI activation of an occipital area in recently detoxified alcohol-dependent patients in a visual and acoustic stimulation paradigm. Addict Biol 2007, 12, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.S.; Luo, X.; Yan, P.; Bergquist, K.; Sinha, R. Altered impulse control in alcohol dependence: neural measures of stop signal performance. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009, 33, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurage, P.; Joassin, F.; Philippot, P.; Heeren, A.; Vermeulen, N.; Mahau, P.; Delperdange, C.; Corneille, O.; Luminet, O.; de Timary, P. Disrupted regulation of social exclusion in alcohol-dependence: an fMRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 2067–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Holst, R.J.; Clark, L.; Veltman, D.J.; van den Brink, W.; Goudriaan, A.E. Enhanced striatal responses during expectancy coding in alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014, 142, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, R.K.; Weiss, R.D. Alcohol Use Disorder and Depressive Disorders. ALCOHOL RESEARCH Current Reviews, 8. [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.F.; Cammisuli, D.M.; Stranks, E.K. Widespread cognitive deficits in alcoholism persistent following prolonged abstinence: An updated meta-analysis of studies that used standardized neuropsychological assessment tools. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 2019, 35(1), 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavro, K.; Pelletier, J.; Potvin, S. Widespread and sustained cognitive deficits in alcoholism: a meta-analysis. Addict Biol 2013, 18, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degasperi, G.; Cristea, I.A.; Di Rosa, E.; Costa, C.; Gentili, C. Parsing variability in borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiri, D.; Moser, D.A.; Doucet, G.E.; Luber, M.J.; Rasgon, A.; Lee, W.H.; Murrough, J.W.; Sani, G.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Frangou, S. Shared Neural Phenotypes for Mood and Anxiety Disorders A Meta-Analysis of 226 Task-Related Functional Imaging Studies. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ) 2021, 19, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pico-Perez, M.; Vieira, R.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, M.; De Barros, M.A.P.; Radua, J.; Morgado, P. Multimodal meta-analysis of structural gray matter, neurocognitive and social cognitive fMRI findings in schizophrenia patients. Psychol Med 2022, 52, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomonov, N.; Victoria, L.W.; Lyons, K.; Phan, D.K.; Alexopoulos, G.S.; Gunning, F.M.; Fluckiger, C. Social reward processing in depressed and healthy individuals across the lifespan: A systematic review and a preliminary coordinate-based meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Behav Brain Res 2023, 454, 114632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamon, H.; Fujino, J.; Itahashi, T.; Frahm, L.; Parlatini, V.; Aoki, Y.Y.; Castellanos, F.X.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Cortese, S. Shared and Specific Neural Correlates of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of 243 Task-Based Functional MRI Studies. Am J Psychiatry 2024, 181, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, D.; Yang, L.; Wang, P.; Xiao, J.; Zou, Z.; Min, W.; He, Y.; Yuan, C.; Zhu, H.; et al. Similarities and differences between post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder: Evidence from task-evoked functional magnetic resonance imaging meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2024, 361, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickhoff, S.B.; Bzdok, D.; Laird, A.R.; Kurth, F.; Fox, P.T. Activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis revisited. Neuroimage 2012, 59, 2349–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, J.L.; Tordesillas-Gutierrez, D.; Martinez, M.; Salinas, F.; Evans, A.; Zilles, K.; Mazziotta, J.C.; Fox, P.T. Bias between MNI and Talairach coordinates analyzed using the ICBM-152 brain template. Hum Brain Mapp 2007, 28, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallach, J.D.; Gueorguieva, R.; Phan, H.; Witkiewitz, K.; Wu, R.; O'Malley, S.S. Predictors of abstinence, no heavy drinking days, and a 2-level reduction in World Health Organization drinking levels during treatment for alcohol use disorder in the COMBINE study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2022, 46, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickhoff, S.B.; Laird, A.R.; Grefkes, C.; Wang, L.E.; Zilles, K.; Fox, P.T. Coordinate-based activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of neuroimaging data: a random-effects approach based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty. Hum Brain Mapp 2009, 30, 2907–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fein, G.; Greenstein, D.; Cardenas, V.A.; Cuzen, N.L.; Fouche, J.P.; Ferrett, H.; Thomas, K.; Stein, D.J. Cortical and subcortical volumes in adolescents with alcohol dependence but without substance or psychiatric comorbidities. Psychiatry Res 2013, 214, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandili, M.; Munakomi, S. Neuroanatomy, Putamen. 2023.

- Hu, W.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Wei, Z.; Tang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yang, J. Reward sensitivity modulates the brain reward pathway in stress resilience via the inherent neuroendocrine system. Neurobiol Stress 2022, 20, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.I. Neuroscientific model of motivational process. Front Psychol 2013, 4, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulton, A.; Hester, R. Transition to substance use disorders: impulsivity for reward and learning from reward. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2020, 15, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, A.M. Reward, motivation and brain imaging in human healthy participants - A narrative review. Front Behav Neurosci 2023, 17, 1123733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, G.; Deschietere, G.; Loas, G.; Luminet, O.; de Timary, P. Link Between Anhedonia and Depression During Early Alcohol Abstinence: Gender Matters. Alcohol Alcohol 2020, 55, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.; Sinha, R. Neuroplasticity and predictors of alcohol recovery. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews.

- Depue, B.E.; Banich, M.T. Increased inhibition and enhancement of memory retrieval are associated with reduced hippocampal volume. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.A.; Tambini, A.; Kiyonaga, A.; D'Esposito, M. Long-term learning transforms prefrontal cortex representations during working memory. Neuron 2022, 110, 3805–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldrati, V.; Patricelli, J.; Colombo, B.; Antonietti, A. The role of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in inhibition mechanism: A study on cognitive reflection test and similar tasks through neuromodulation. Neuropsychologia 2016, 91, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Caneda, E.; Rodriguez Holguin, S.; Cadaveira, F.; Corral, M.; Doallo, S. Impact of alcohol use on inhibitory control (and vice versa) during adolescence and young adulthood: a review. Alcohol Alcohol 2014, 49, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, M. Anti-saccade as a Tool to Evaluate Neurocognitive Impairment in Alcohol Use Disorder. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 823848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rure, D.; Shakya, M.; Singhal, A.; Varma, A.; Mishra, N.; Pathak, U. A Study of the association of neurocognition with relapse and quality of life in patients of alcohol dependence. Ind Psychiatry J 2024, 33, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, T.; Leff, A.; de Boissezon, X.; Joffe, A.; Sharp, D.J. Cognitive control and the salience network: an investigation of error processing and effective connectivity. J Neurosci 2013, 33, 7091–7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, P.; Dai, Z.; Zhong, J.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, H.; Pan, P. Regional gray matter deficits in alcohol dependence: A meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015, 153, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardee, J.E.; Weigard, A.S.; Heitzeg, M.M.; Martz, M.E.; Cope, L.M. Sex differences in distributed error-related neural activation in problem-drinking young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 2024, 263, 112421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Mitchell, D.; Jones, M.; Mondillo, K.; Vythilingam, M.; Blair, R.J. Common regions of dorsal anterior cingulate and prefrontal–parietal cortices provide attentional control of distracters varying in emotionality and visibility. NeuroImage 2007, 38(3), 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, L.; Welsh, J.C.; Johnson, C.G.; Kaiser, R.H.; Farchione, T.J.; Janes, A.C. Alcohol- and non-alcohol-related interference: An fMRI study of treatment-seeking adults with alcohol use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2022, 235, 109462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padula, C.B.; Tenekedjieva, L.T.; McCalley, D.M.; Al-Dasouqi, H.; Hanlon, C.A.; Williams, L.M.; Kozel, F.A.; Knutson, B.; Durazzo, T.C.; Yesavage, J.A.; et al. Targeting the Salience Network: A Mini-Review on a Novel Neuromodulation Approach for Treating Alcohol Use Disorder. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 893833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickhoff, S.B.; Nichols, T.E.; Laird, A.R.; Hoffstaedter, F.; Amunts, K.; Fox, P.T.; Bzdok, D.; Eickhoff, C.R. Behavior, sensitivity, and power of activation likelihood estimation characterized by massive empirical simulation. Neuroimage 2016, 137, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, J.R.; Done, J.; Simons, J.S. Interpretation of published meta-analytical studies affected by implementation errors in the GingerALE software. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019, 102, 424–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.H.; Han, K.; Jeong, S.M.; Park, J.; Yoo, J.E.; Yoo, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Shin, D.W. Changes in Alcohol Consumption and Risk of Dementia in a Nationwide Cohort in South Korea. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2254771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, H.; Wan, Y.; Tan, C.; Li, J.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.T. Alcohol consumption and dementia risk: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2017, 32, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarezadeh, M.; Mahmoudinezhad, M.; Faghfouri, A.H.; Mohammadzadeh Honarvar, N.; Regestein, Q.R.; Papatheodorou, S.I.; Mekary, R.A.; Willett, W.C. Alcohol consumption in relation to cognitive dysfunction and dementia: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of comparative longitudinal studies. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 100, 102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n cases | n controls | Mean age cases | Mean age controls | % of male for cases | % of male for controls | Mean days of abstinence (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole sample | ||||||

| 2,421 | 1,458 | 36.94 | 37.07 | 76.73 | 73.26 | 189.54 (5-2994)a |

| Short-term Abstinent sample | ||||||

| 1,097 | 653 | 35.71 | 34.46 | 76.32 | 70.71 | 16.10 (5-25.30)b |

| Long-term Abstinent sample | ||||||

| 991 | 488 | 37.42 | 40.15 | 77.56 | 78.35 | 416.47 (34-2994)c |

| Regions | L/R | Cluster size (mm3) | ALE value | Z-score | Coordinates (MNI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyper-Hypoactivation combined: whole sample | |||||

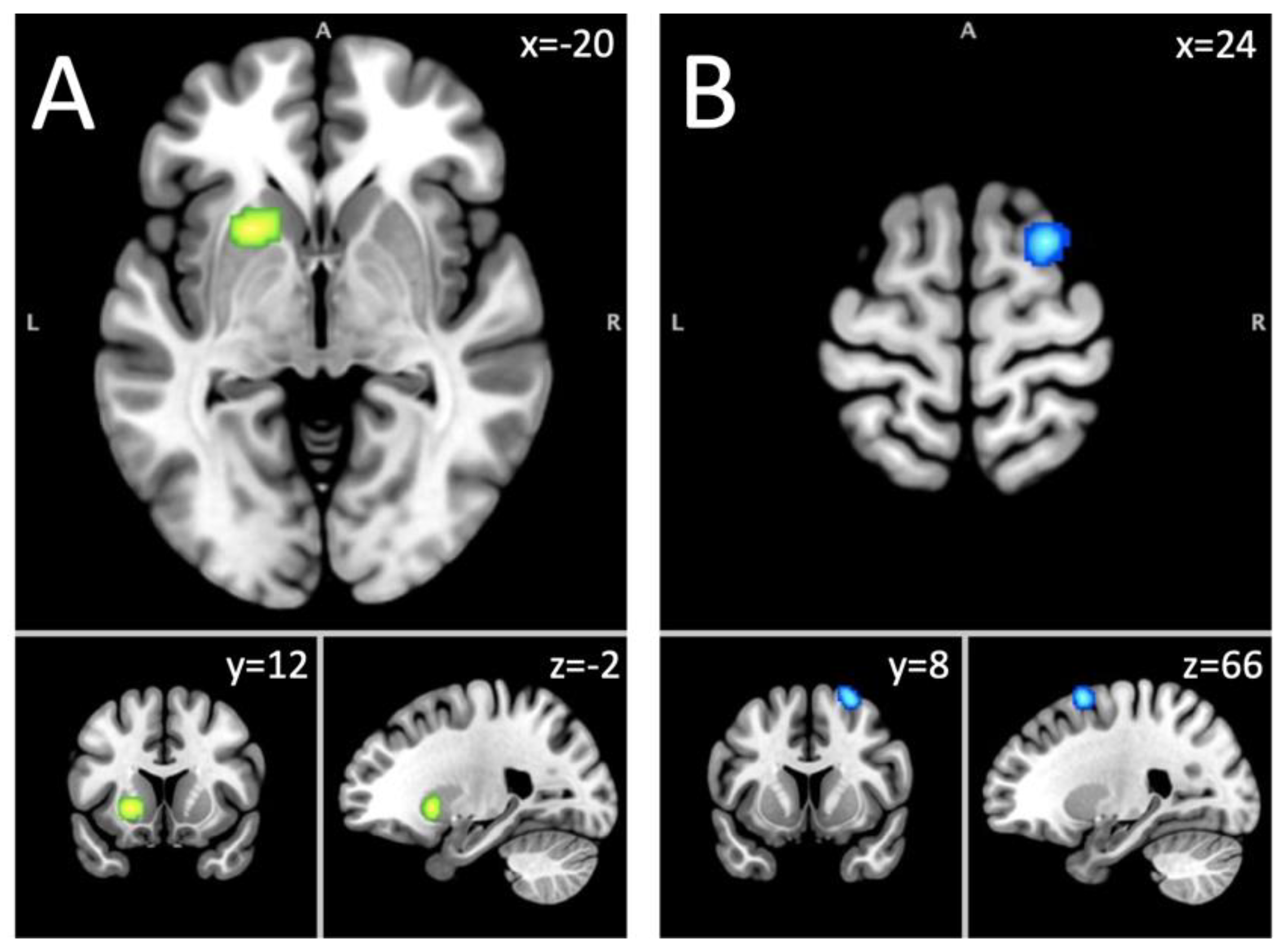

| Putamen, caudate body, caudate head | L | 1840 | 0.0367 | 5.66 | -20,12,-2 |

| Hyperactivation: whole sample | |||||

| No clusters found | |||||

| Hypoactivation: whole sample | |||||

| No clusters found | |||||

| Hyper-Hypoactivation combined: acute sample | |||||

| Putamen | L | 1096 | 0.0236 | 4.88 | -20,12,-2 |

| Hyperactivation: acute sample | |||||

| No clusters found | |||||

| Hypoactivation: acute sample | |||||

| Middle frontal gyrus, superior frontal gyrus, sub-gyral | R | 856 | 0.016 | 4.48 | 24,8,66 |

| Hyper-Hypoactivation combined: abstinent sample | |||||

| No clusters found | |||||

| Hyperactivation: abstinent sample | |||||

| No clusters found | |||||

| Hypoactivation: abstinent sample | |||||

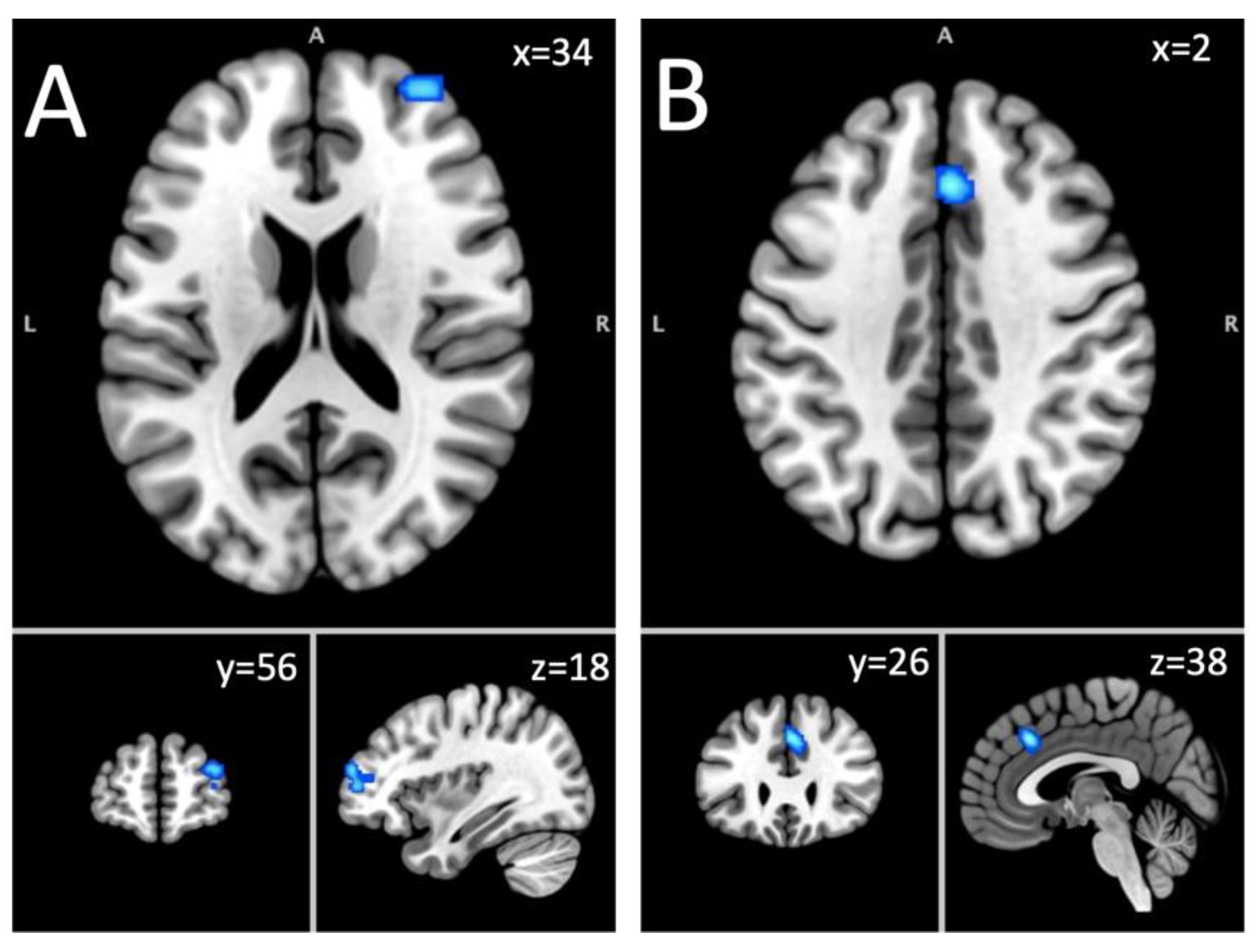

| Superior frontal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus | R | 856 | 0.0147 | 3.85 | 34,56,18 |

| Cingulate gyrus, medial frontal gyrus | R & L | 800 | 0.017 | 4.26 | 2,26,38 |

| 95 C.I. for odds ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Odds ratio | Lower | Higher | p-value |

| Hyper-hypoactivation in the short-term abstinent sample: Putamen | ||||

| Age | 0.985 | 0.900 | 1.077 | 0.735 |

| Sex ratio (% male) | 0.981 | 0.951 | 1.013 | 0.245 |

| Days of abstinence | 0.939 | 0.746 | 1.182 | 0.590 |

| MRI field strength | 0.737 | 0.110 | 4.955 | 0.753 |

| Smoothing level | 0.701 | 0.422 | 1.164 | 0.170 |

| Voxel size | 1.047 | 0.993 | 1.103 | 0.088 |

| Time repetition | 0.998 | 0.996 | 1.000 | 0.115 |

| Craving studies | 0.489 | 0.050 | 4.793 | 0.539 |

| Decision-making studies | 9.333 | 1.270 | 68.597 | 0.028* |

| Emotion studies | 1.350 | 0.124 | 14.734 | 0.806 |

| Executive functions studies | 0.364 | 0.038 | 3.518 | 0.382 |

| Reward processing studies | 30.000 | 2.330 | 386.325 | 0.009* |

| Other task studies | 3.375 | 0.459 | 24.837 | 0.232 |

| Hypoactivation in the short-term abstinent sample: Middle frontal gyrus | ||||

| Age | 0.942 | 0.854 | 1.040 | 0.234 |

| Sex ratio (% male) | 0.985 | 0.951 | 1.021 | 0.417 |

| Days of abstinence | 0.859 | 0.664 | 1.113 | 0.251 |

| MRI field strength | 0.762 | 0.060 | 9.611 | 0.833 |

| Smoothing level | 1.068 | 0.648 | 1.760 | 0.797 |

| Voxel size | 1.054 | 0.989 | 1.123 | 0.108 |

| Time repetition | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.001 | 0.924 |

| Craving studies | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.999 |

| Decision-making studies | 7.250 | 0.786 | 66.842 | 0.080 |

| Emotion studies | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.999 |

| Executive functions studies | 2.300 | 0.283 | 18.705 | 0.436 |

| Reward processing studies | 3.333 | 0.259 | 42.925 | 0.356 |

| Other task studies | 1.867 | 0.160 | 21.742 | 0.618 |

| Hypoactivation in the long-term abstinent sample: Superior frontal gyrus | ||||

| Age | 0.963 | 0.894 | 1.038 | 0.323 |

| Sex ratio (% male) | 0.993 | 0.950 | 1.037 | 0.746 |

| Days of abstinence | 1.002 | 0.999 | 1.004 | 0.153 |

| MRI field strength | 0.500 | 0.066 | 3.770 | 0.501 |

| Smoothing level | 0.586 | 0.278 | 1.233 | 0.159 |

| Voxel size | 0.980 | 0.939 | 1.022 | 0.337 |

| Time repetition | 1.001 | 0.999 | 1.004 | 0.267 |

| Craving studies | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.999 |

| Decision-making studies | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Emotion studies | 3.800 | 0.201 | 72.000 | 0.374 |

| Executive functions studies | 1.167 | 0.166 | 8.186 | 0.877 |

| Reward processing studies | 9.000 | 1.031 | 78.574 | 0.047* |

| Other task studies | 1.500 | 0.208 | 10.823 | 0.688 |

| Hypoactivation in the long-term abstinent sample: Cingulate gyrus | ||||

| Age | 1.025 | 0.931 | 1.128 | 0.617 |

| Sex ratio (% male) | 1.022 | 0.964 | 1.084 | 0.456 |

| Days of abstinence | 0.997 | 0.990 | 1.004 | 0.387 |

| MRI field strength | 1.125 | 0.097 | 13.036 | 0.925 |

| Smoothing level | 0.956 | 0.450 | 2.031 | 0.906 |

| Voxel size | 0.999 | 0.948 | 1.052 | 0.955 |

| Time repetition | 1.000 | 0.997 | 1.002 | 0.708 |

| Craving studies | 1.500 | 0.122 | 18.441 | 0.751 |

| Decision-making studies | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Emotion studies | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.999 |

| Executive functions studies | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.999 |

| Reward processing studies | 6.333 | 0.630 | 63.639 | 0.117 |

| Other task studies | 3.400 | 0.377 | 30.655 | 0.275 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).