Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Data Extraction and Inflammatory Indexes Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Subsection

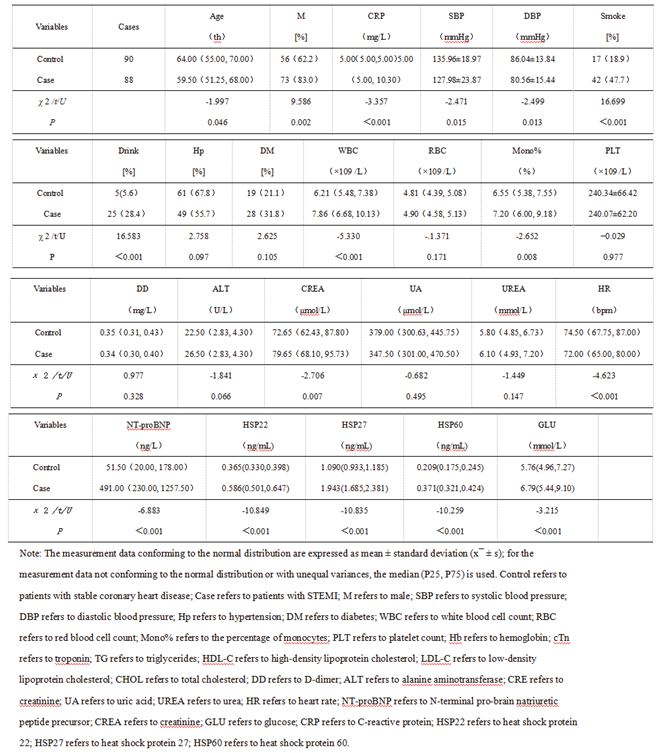

3.1.1. Comparison of Baseline Data and Serum Levels of HSP22, HSP27, and HSP60 at Admission Between the Stable Coronary Heart Disease Group and the STEMI Group

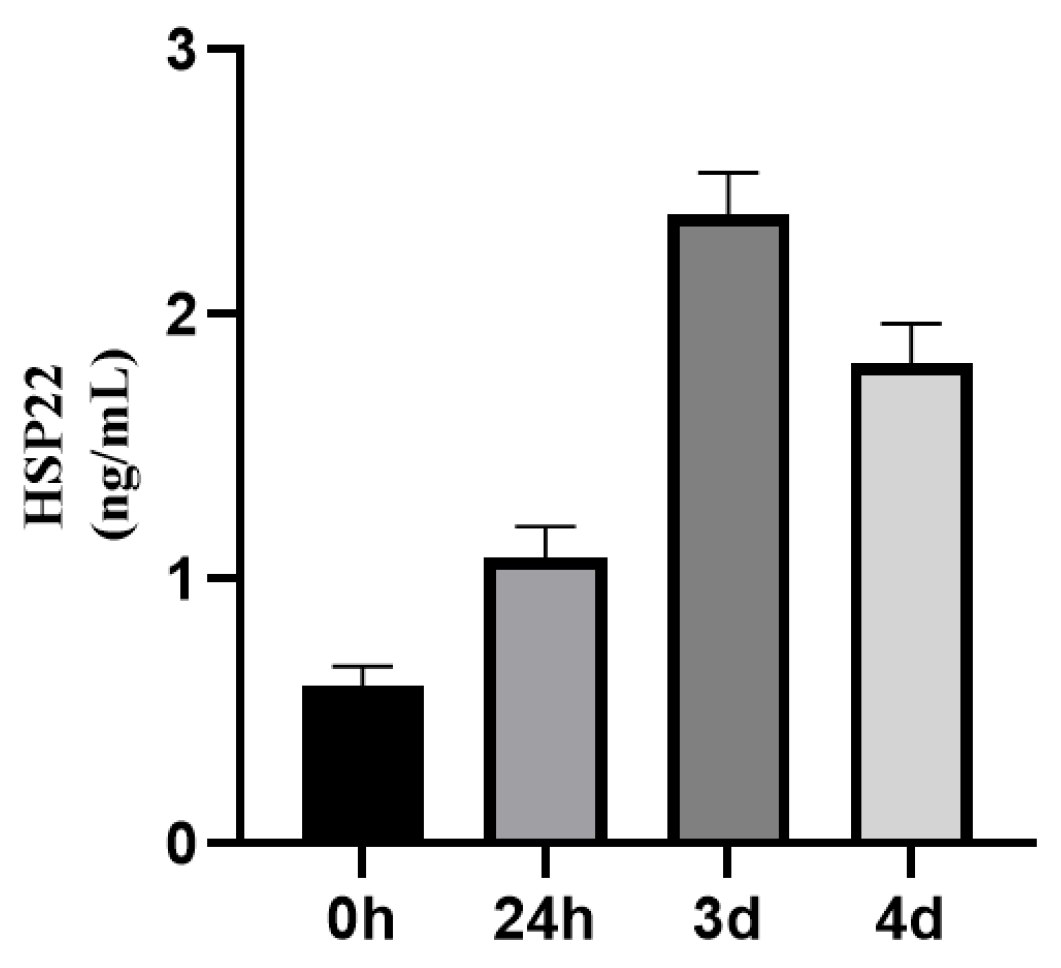

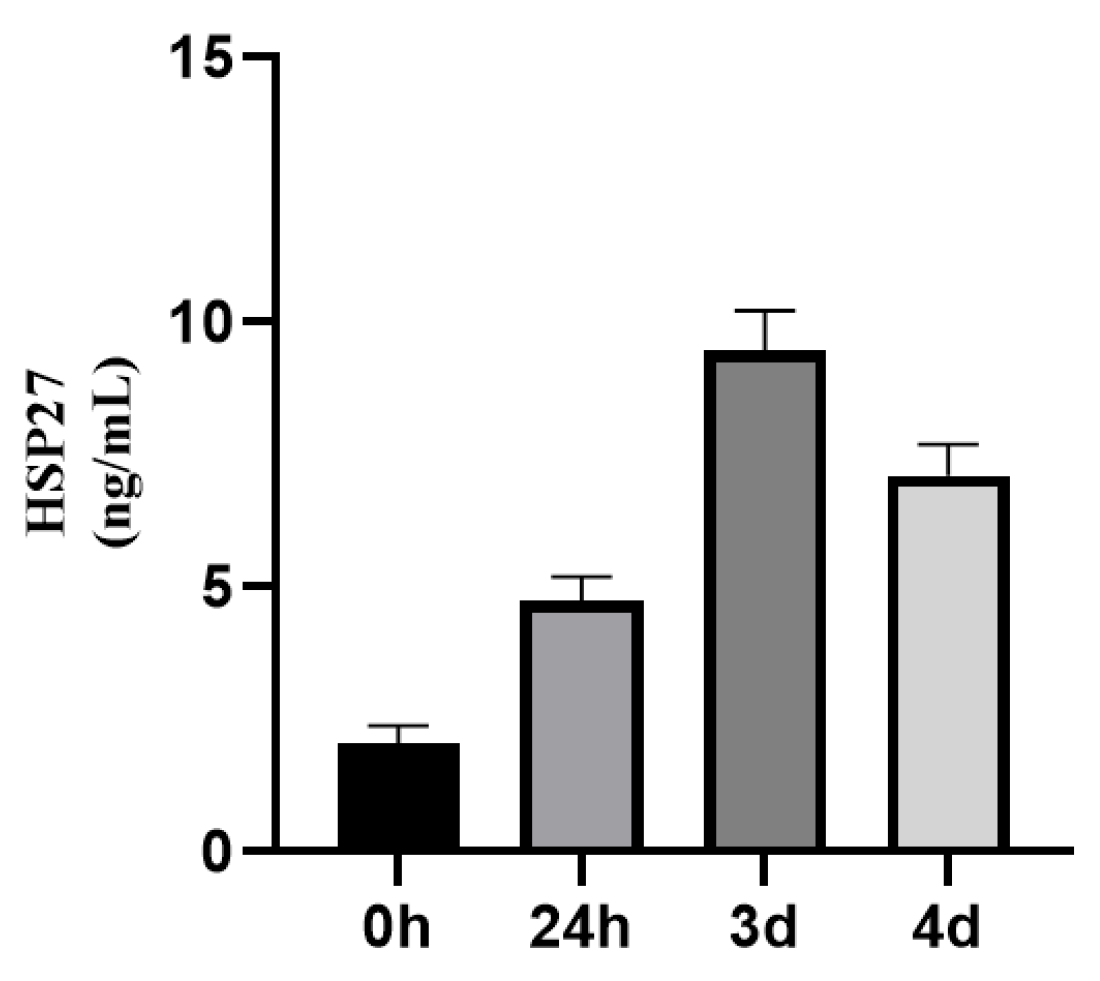

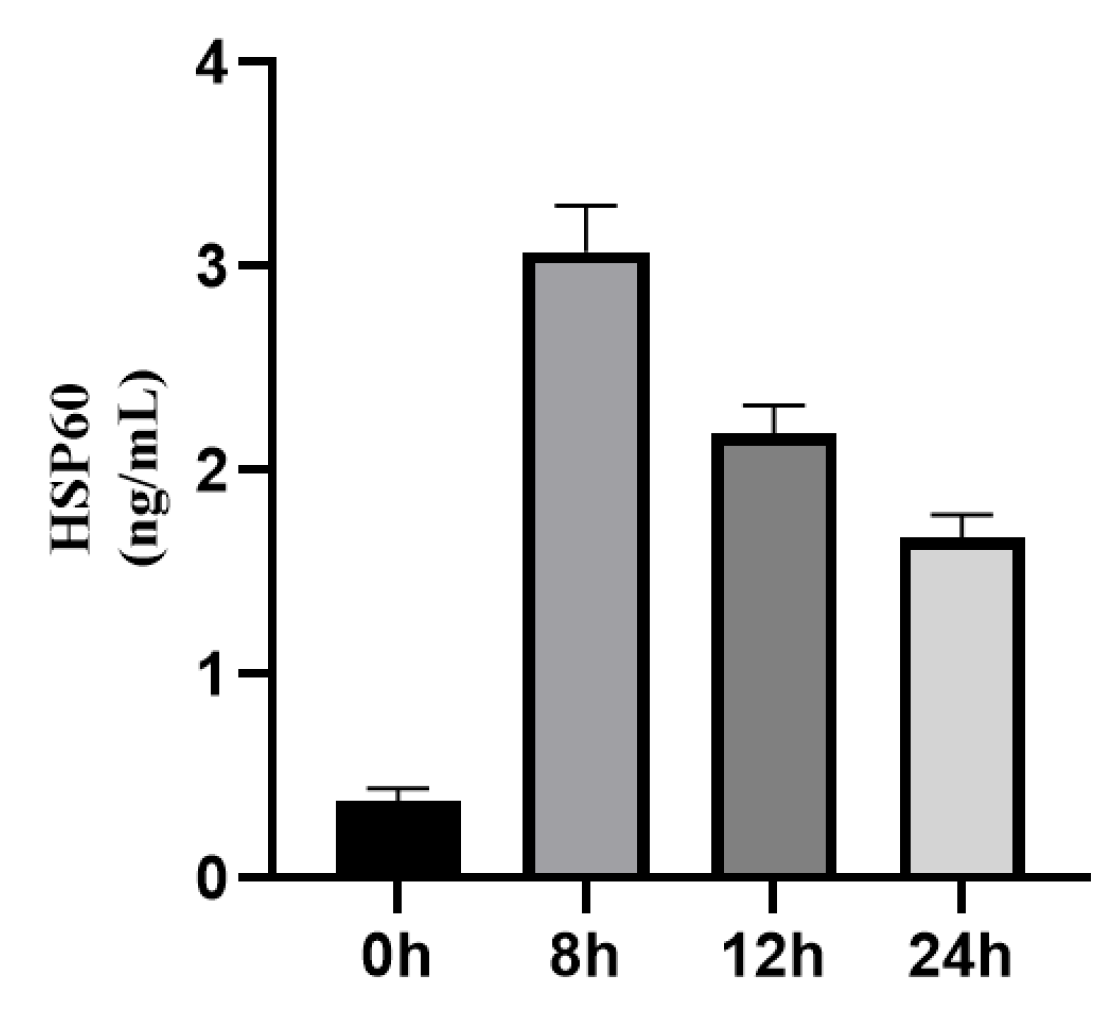

3.1.2. Dynamic Changes of HSP22, HSP27, and HSP60 Expressions in STEMI Patients Before and After Emergency PCI

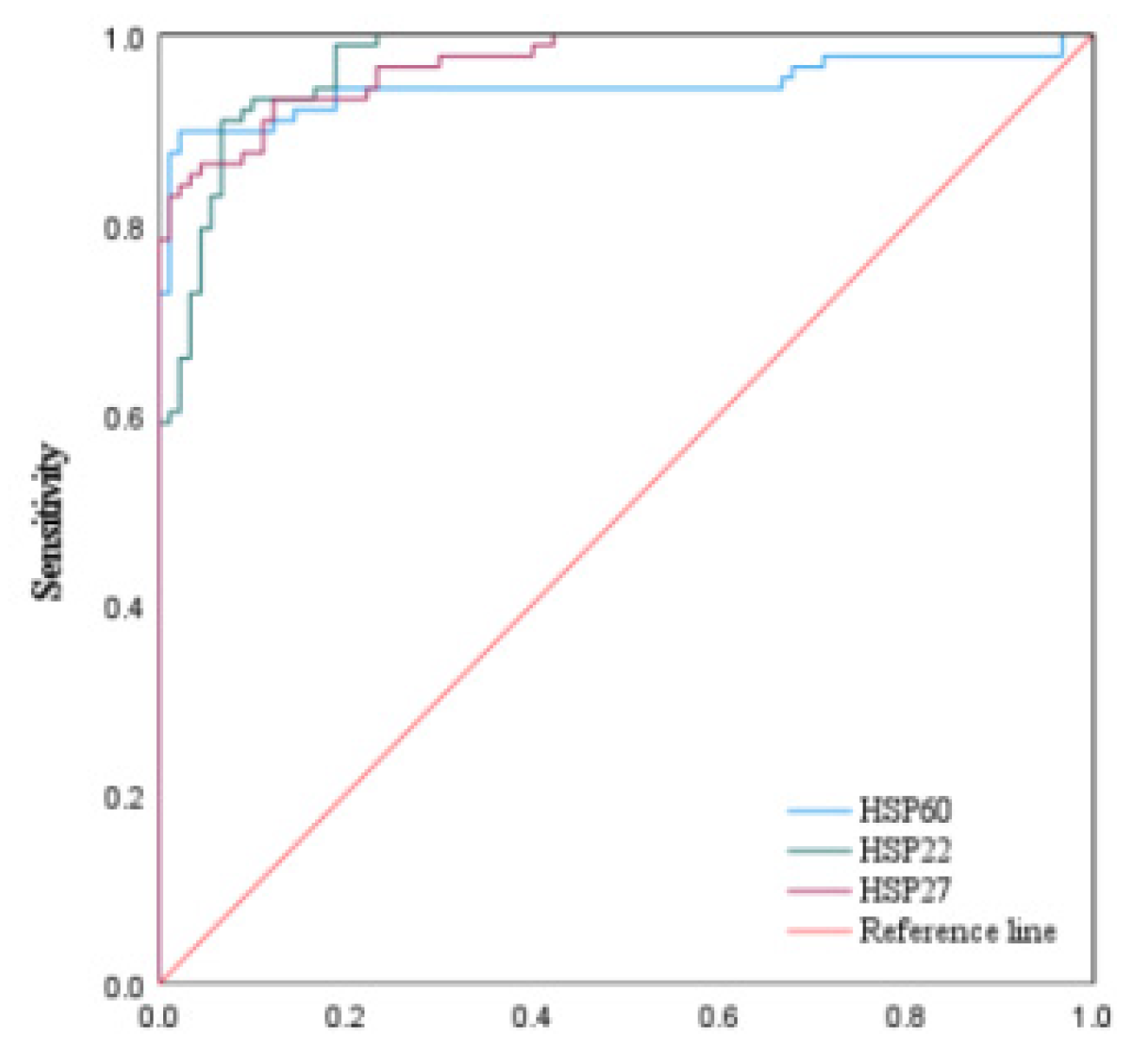

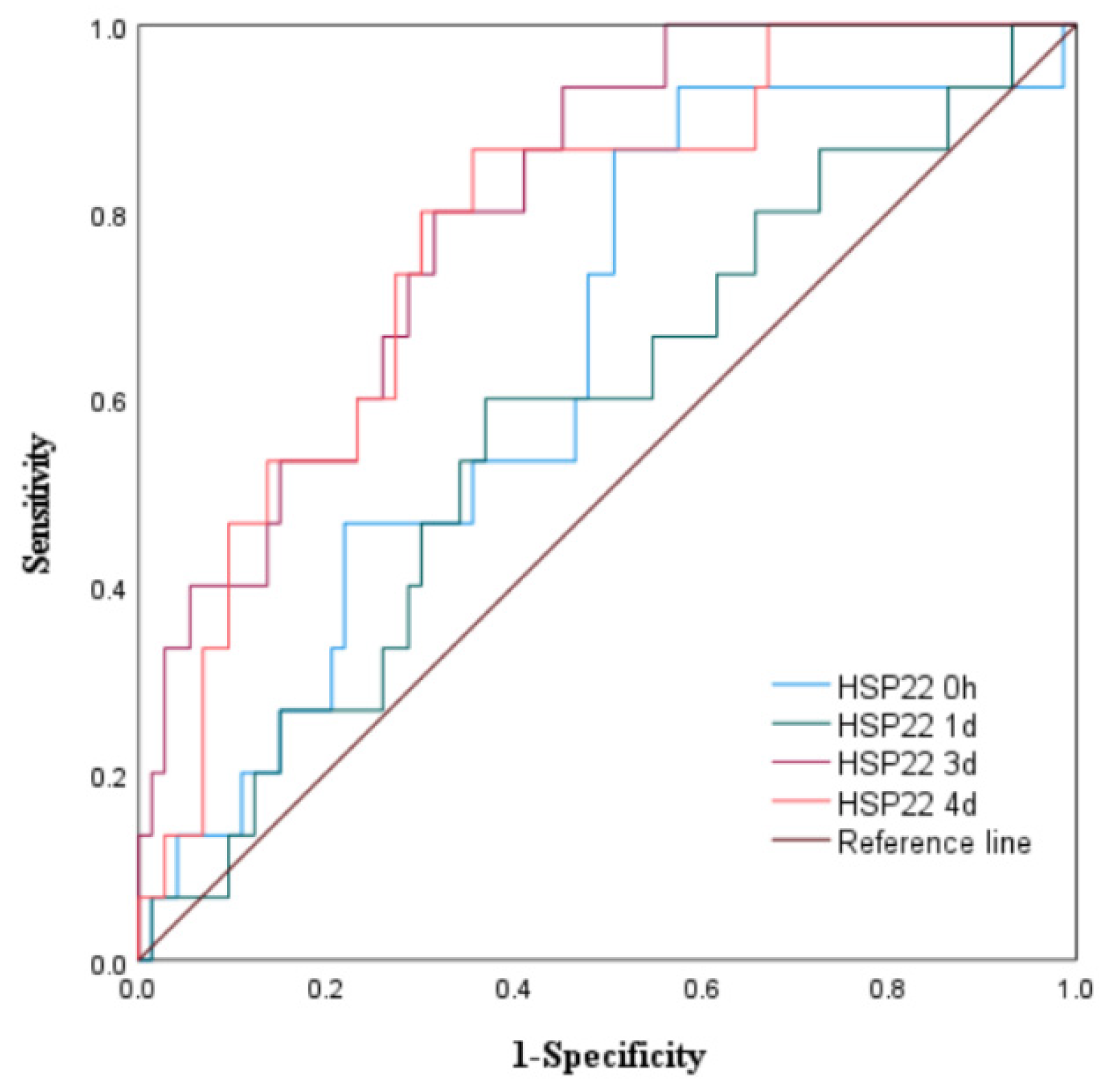

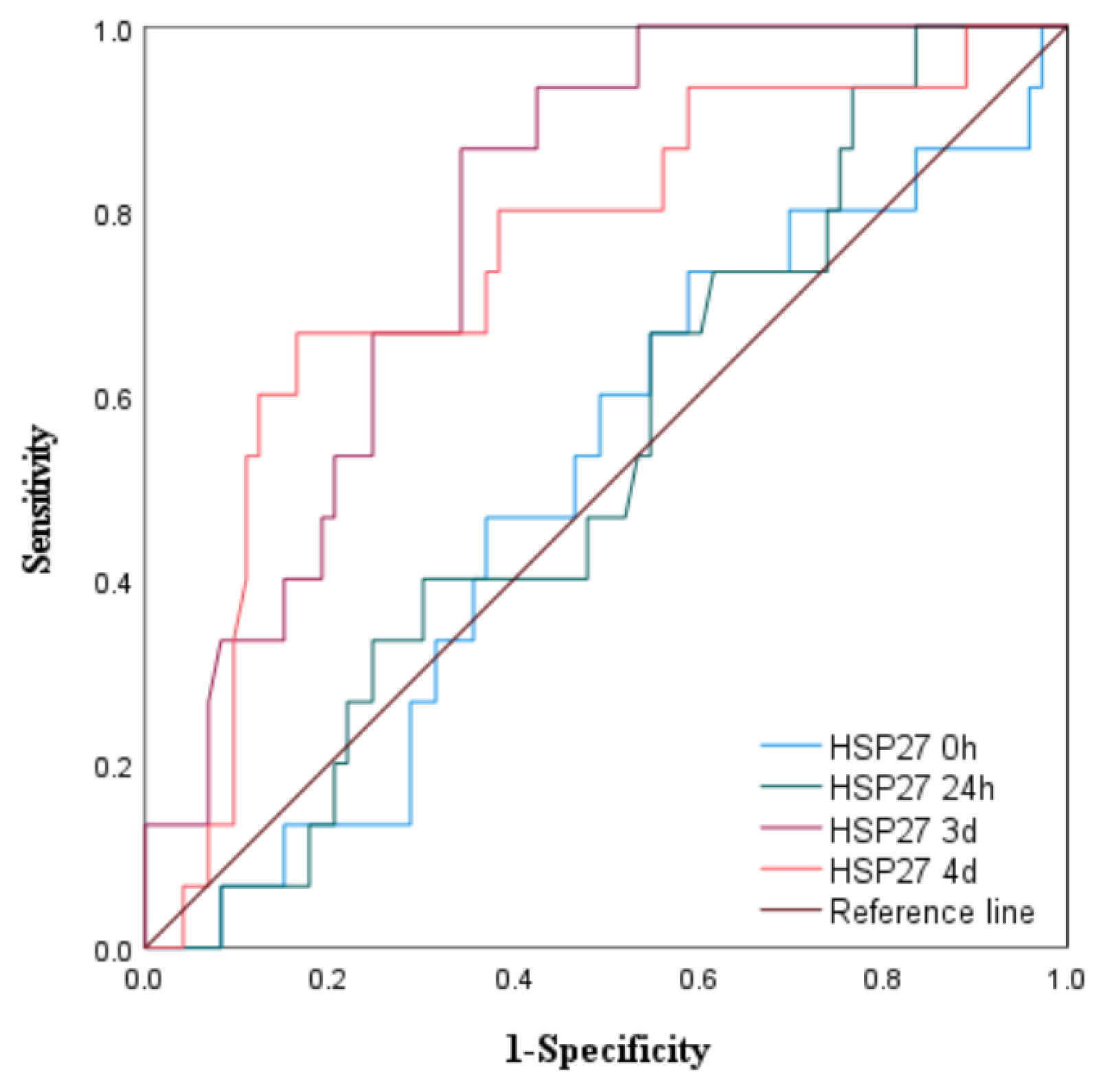

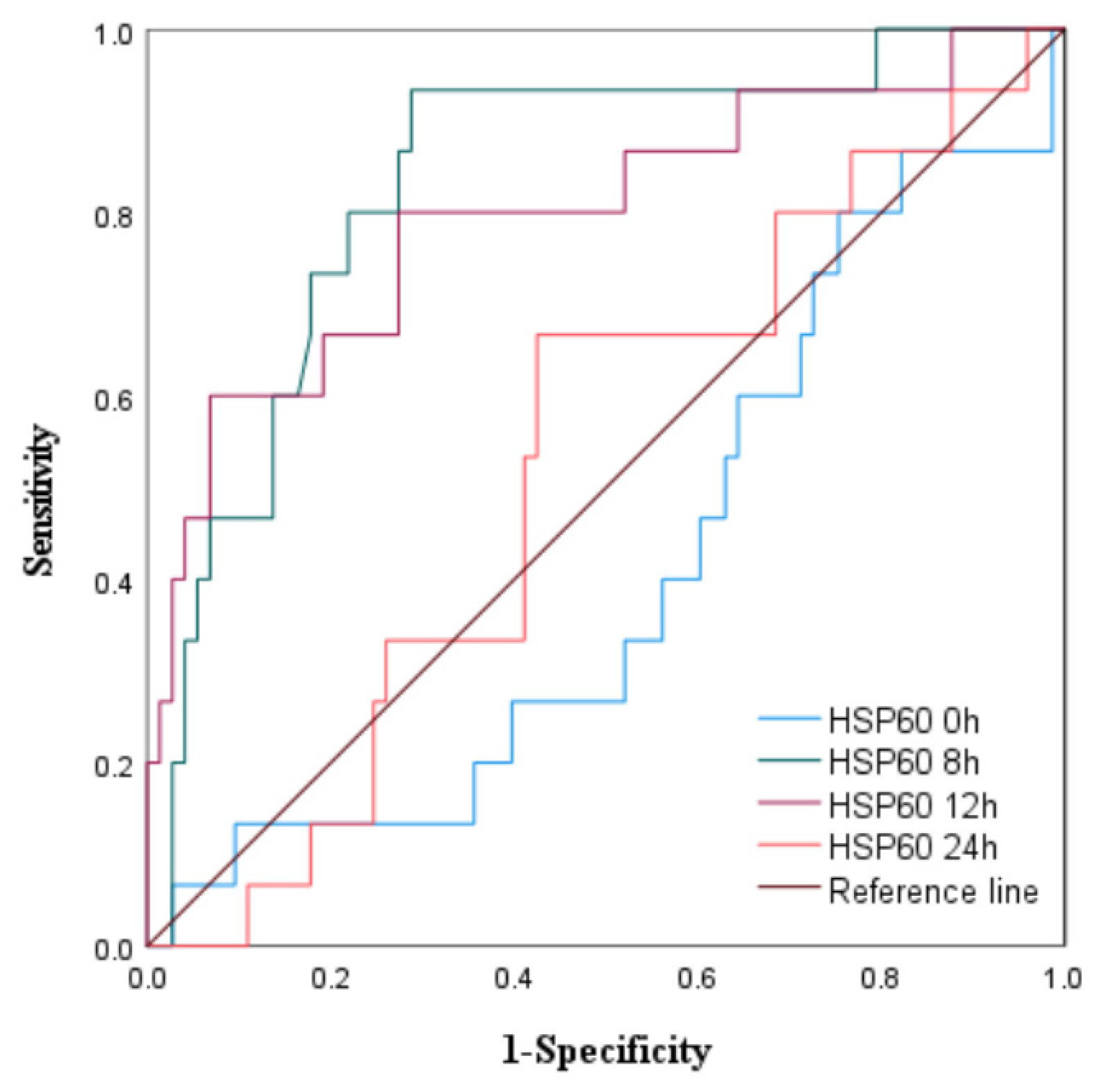

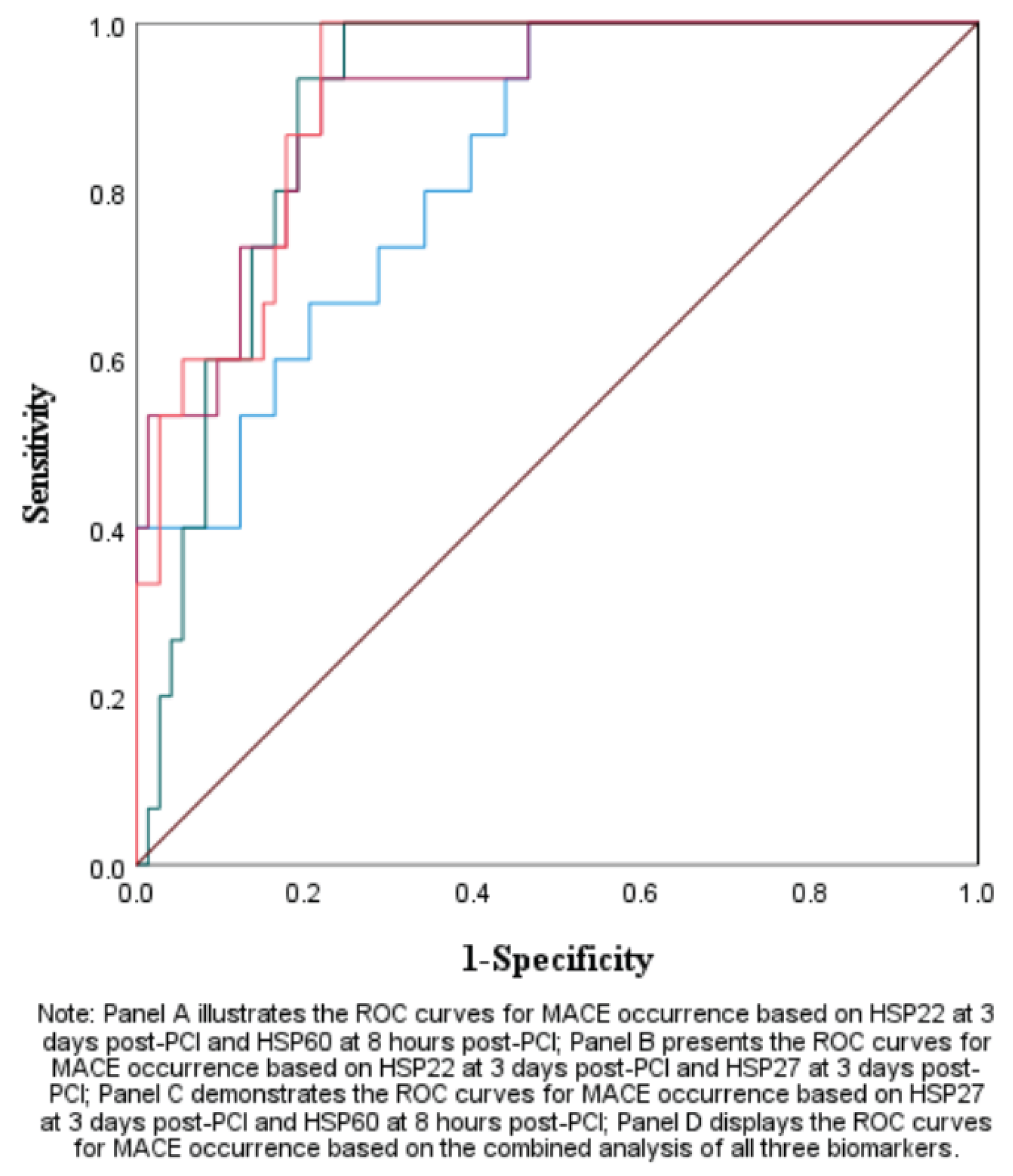

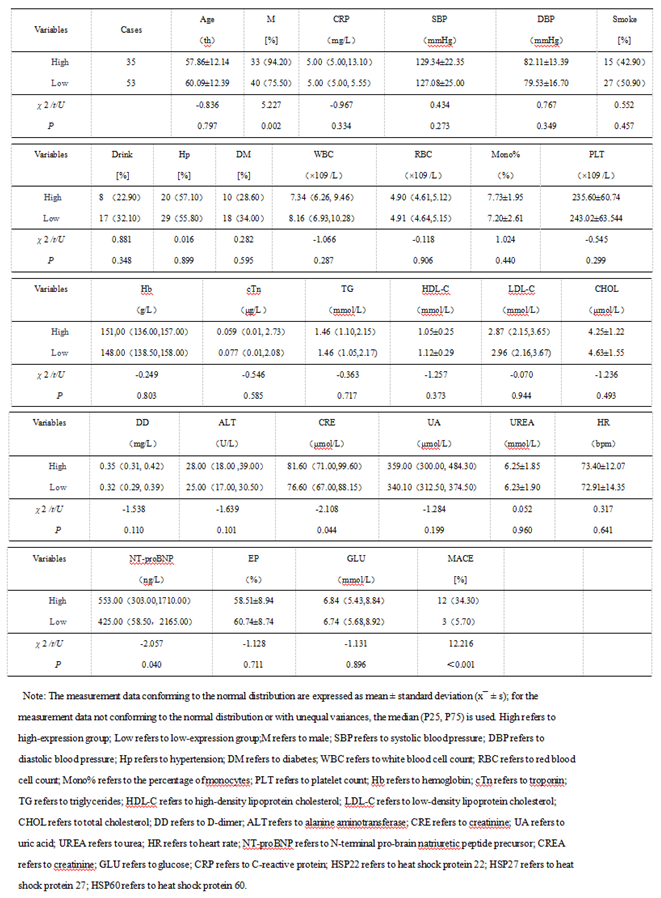

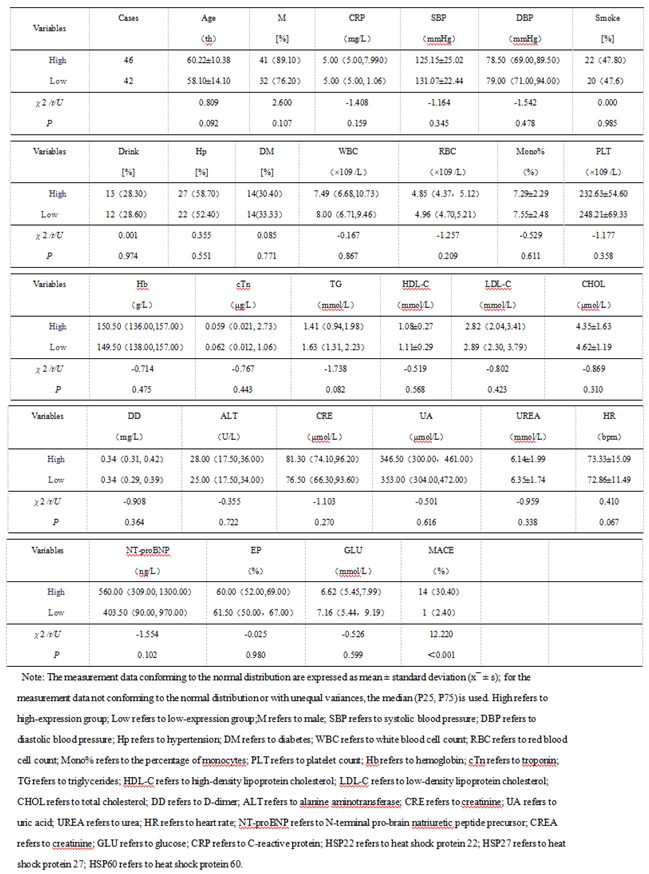

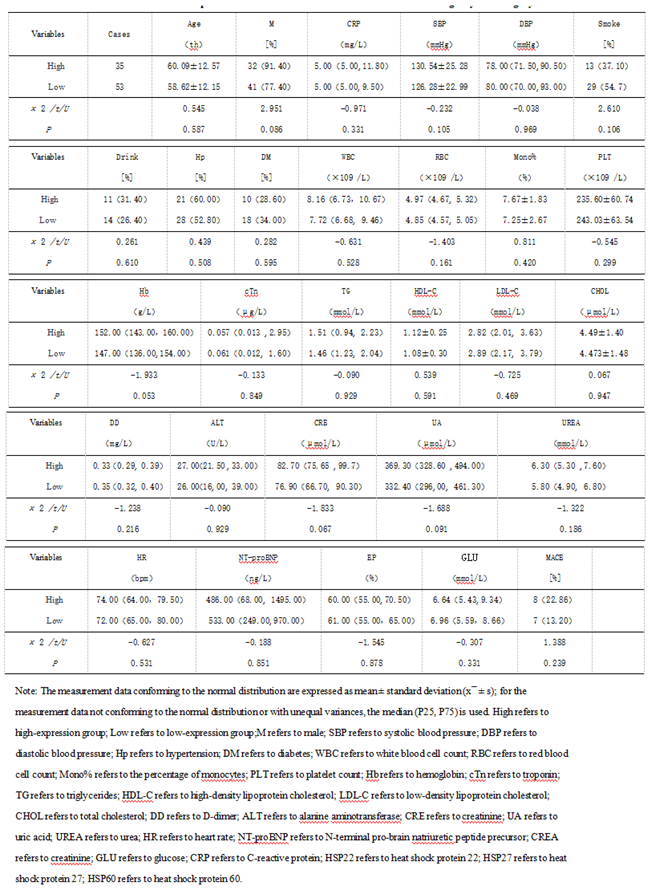

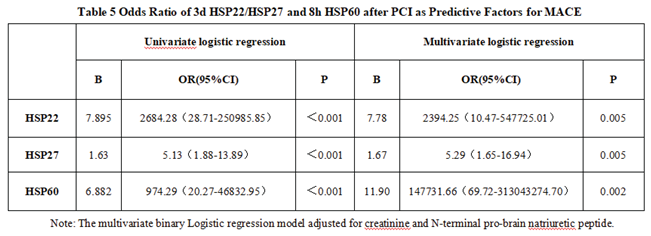

3.1.3. The Predictive Value of Peak Levels of HSP22, HSP27, and HSP60 for MACE in STEMI Patients After Emergency PCI

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVD | Cardiovascular diseases |

| STEMI | ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| PCI | Percutaneous coronary intervention |

| MACE | Major adverse cardiovascular events |

| HSPs | Heat shock proteins |

| HSP22 | Heat shock protein 22 |

| HSP27 | Heat shock protein 27 |

| HSP60 | Heat shock protein 60 |

References

- Zhao Y, Cui R, Du R, Song C,et al.Platelet-Derived Microvesicles Mediate Cardiomyocyte Ferroptosis by Transferring ACSL1 During Acute Myocardial Infarction. Mol Biotechnol. 2025 Feb;67(2):790-804. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Li M, Wu Y. Heat shock protein 22: A new direction for cardiovascular disease (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2025 Mar;31(3):82. [CrossRef]

- Wang ZY, Lu Y, Zhang WJ, Zhang JX,et al.[Effect of plasma RIPK3 levels on long-term prognosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2025 Mar 24;53(3):268-273. Chinese. [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Sánchez J, Teira Calderón A, Neves D, Cortés Villar C, Lukic A, Rumiz González E, Sánchez-Elvira G, Patricio L, Díez-Gil JL, García-García HM, Martínez Dolz L, San Román JA, Amat Santos I. Culprit-Lesion Drug-Coated-Balloon Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients Presenting with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI). J Clin Med. 2025 Jan 28;14(3):869. [CrossRef]

- O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD,et al. CF/AHA Task Force. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Jan 29;127(4):529-55.

- Chen Y, Li M, Wu Y. Heat shock protein 22: A new direction for cardiovascular disease (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2025 Mar;31(3):82. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin IJ and McMillan DR: Stress (heat shock) proteins:Molecular chaperones in cardiovascular biology and disease.Circ Res 83: 117-132, 1998.

- Deniset JF and Pierce GN: Heat shock proteins: Mediators of atherosclerotic development. Curr Drug Targets 16: 816-826,2015.

- Nayak Rao S: The role of heat shock proteins in kidney disease.J Transl Int Med 4: 114-117, 2016.

- Patnaik S, Nathan S,et al. The Role of Extracellular Heat Shock Proteins in Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomedicines. 2023 May 27;11(6):1557.

- ó Hartaigh B, Bosch JA, Thomas GN,et al. (2012)Which leukocyte subsets predict cardiovascular mortality? From the LUdwigshafen RIsk and Cardiovascular Health (LURIC) Study. Atheroscle -rosis 224(1):161–169.

- Mandal K, Jahangiri M, Xu Q. Autoimmune mechanisms of atherosclerosis. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2005;170:723–43.

- Núñez J, Núñez E, Bodí V, et al. (2008) Usefulness of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in predicting long-termmortality in ST segment elevationmy-ocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 101(6):747–752.

- Xu Q. Role of heat shock proteins in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22(10):1547–59.

- Savovic Z, Pindovic B, Nikolic M, et al. Prognostic Value of Redox Status Biomarkers in Patients Presenting with STEMI or Non-STEMI: A Prospective Case-Control Clinical Study. J Pers Med. 2023 Jun 26;13(7):1050. [CrossRef]

- Xu Q, Metzler B, Jahangiri M,et al.Molecular chaperones and heat shock proteins in atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302(3):H506–14. [CrossRef]

- Boteanu RM, Suica VI, Uyy E, Ivan L, Dima SO, Popescu I, Simionescu M, Antohe F. Alarmins in chronic noncommunicable diseases: Atherosclerosis, diabetes and cancer. J Proteomics. 2017;153:21–9.

- Wang S, Zhang G Association Between Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index and Adverse Out-comes inPatientsWithAcuteCoronarySyndrome:A Meta-Analysis. Angiology. 2024 Jun 21:33197241263399.

- de Liyis BG,Ciaves AF, Intizam MH,et al. Hematological biomarkers of troponin, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio serve as effective predictive indicators of high-risk mortality in acute coronary syndrome. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2023 Dec 1;13(4):32-43.

- Antonopoulos AS, Angelopoulos A, Papaniko-laou P, et al. (2022) Biomarkers of Vascular Inflammation for Cardiovascular RiskPrognostica-tion: A Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging15(3):460–471. [CrossRef]

- Kappé G, Verschuure P, Philipsen RL, et al. Characterization of two novel human small heat shock proteins: Protein kinase-related HspB8 and testis-specific HspB9. Biochim Biophys Acta 1520: 1-6, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Sui X,Li D, Qiu H,et al.Activation of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor by H11kinase/Hsp22 promotes cardiac cell growth and survival. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 887–895. [CrossRef]

- Depre C,Wang L, Sui X, et al. H11 kinase prevents myocardial infarction by preemptive preconditioning of the heart. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 280–288. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Lizano P,Zhao X, et al.Preemptive conditioning of the swine heart by H11 kinase/Hsp22 provides cardiac protection through inducible nitric oxide synthase. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 300, H1303–H1310. [CrossRef]

- Lizano P,Rashed E, Kang, H,et al. The valosin-containing protein promotes cardiac survival through the inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 99, 685–693.

- Qiu H, Lizano P, Laure L, et al.H11 kinase/heat shock protein 22 deletion impairs both nuclear and mitochondrial functions of STAT3 and accelerates the transition into heart failure on cardiac overload. Circulation 124: 406-415, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Wu W, Sun X, Shi X, et al.Hsp22 deficiency induces age-dependent cardiac dilation and dysfunction by impairing autophagy, metabolism, and oxidative response. Antioxidants (Basel) 10: 1550, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Adamo L, Rocha-Resende C, Prabhu SD, et al. Reappraising the role of inflammation in heart failure[J]. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2020,17(5):269-285. [CrossRef]

- Wolf D, Ley K. Immunity and inflammation in atherosclerosis[J]. Circ Res,2019,124(2):315-327. [CrossRef]

- Mcdonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure[J]. Eur Heart J,2021,42(36):3599-3726.

- Pulakazhi Venu VK, Adijiang A, Seibert T, et al.O’Brien ER. Heat shock protein 27-derived atheroprotection involves reverse cholesterol transport that is dependent on GM-CSF to maintain ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression in ApoE-/- mice. FASEB J. 2017 Jun;31(6):2364-2379.

- Murphy SP, Kakkar R, McCarthy CP, et al. Inflammation in heart failure: JACC state-of-the-art review[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol,2020,75(11):1324-1340.

- Liu S, Iskandar R, Chen W, et al. Soluble glycoprotein 130 and heat shock protein 27 as novel candidate biomarkers of chronic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction[J]. Heart Lung Circ,2016,25(10):1000-1006. [CrossRef]

- Caruso Bavisotto C, Alberti G, Vitale AM, et al.Hsp60 Post-translational Modifications: Functional and Pathological Consequences. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:95.

- Liyanagamage D, Martinus RD. Role of Mitochondrial Stress Pro-tein HSP60 in Diabetes -Induced Neuroinflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2020;2020:8073516.

- Tian J, Guo X, Liu XM, et al. Extracellular HSP60 induces inflammation through activating and up-regulating TLRs in cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2013 Jun 1;98(3):391-401.

- Knoflach M, Bernhard D, Wick G. Anti-HSP60 immunity is already associated with atherosclerosis early in life. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1051:323–31.

- Zonnar S, Saeedy SAG, Nemati F,et al.Decrescent role of recombinant HSP60 antibody against atherosclerosis in high-cholesterol diet immunized rabbits. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2022;25(1):32–8.

- Amirfakhryan H. Vaccination against atherosclerosis: An overview. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2020;61(2):78–91.

- Wang S, Chen Y, Zhou D, et al. Pathogenic Autoimmunity in Atherosclerosis Evolves from HSP60-Reactive CD4 + T Cells. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2024 Oct;17(5):1172-1180.

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).