Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

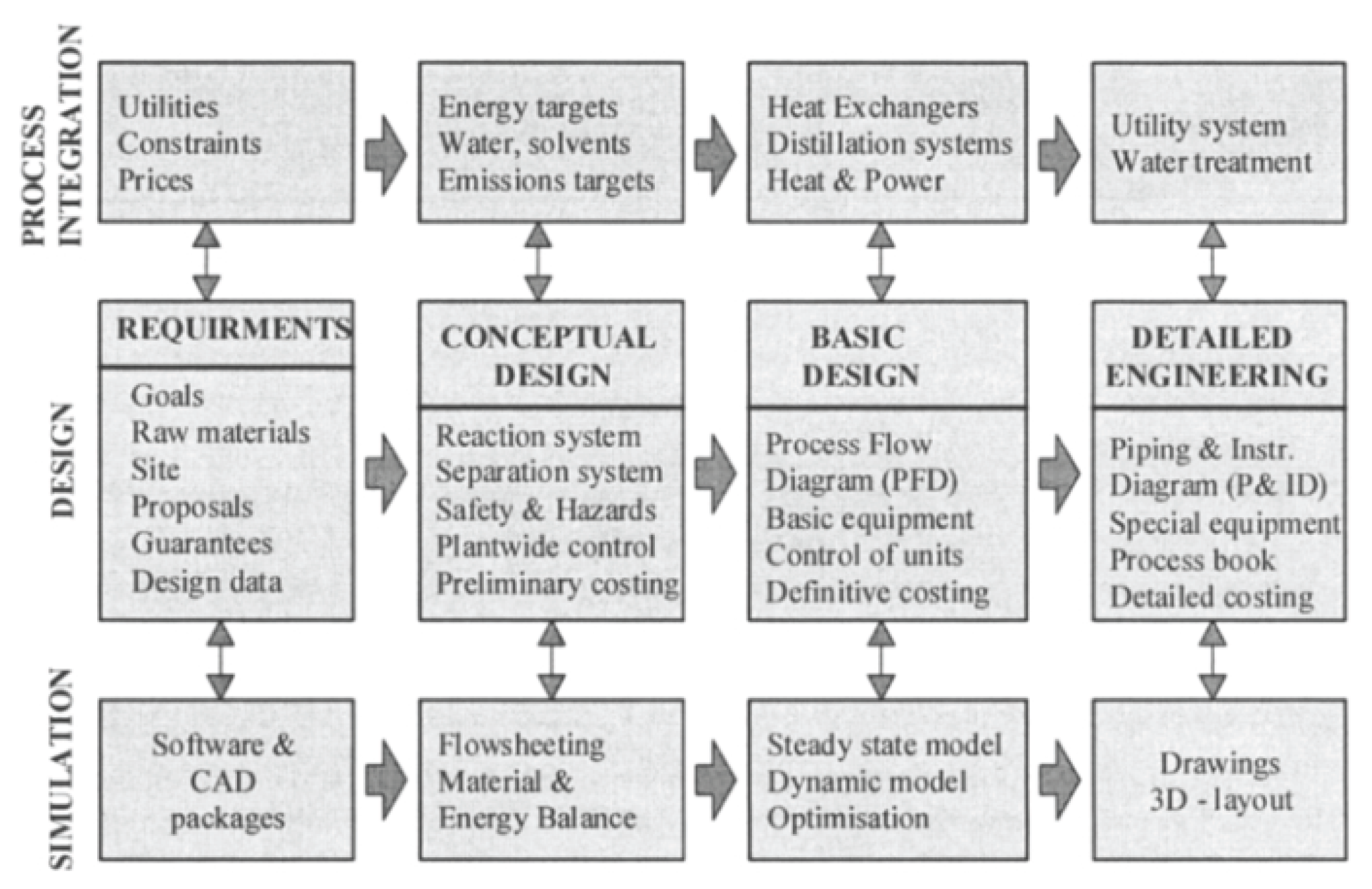

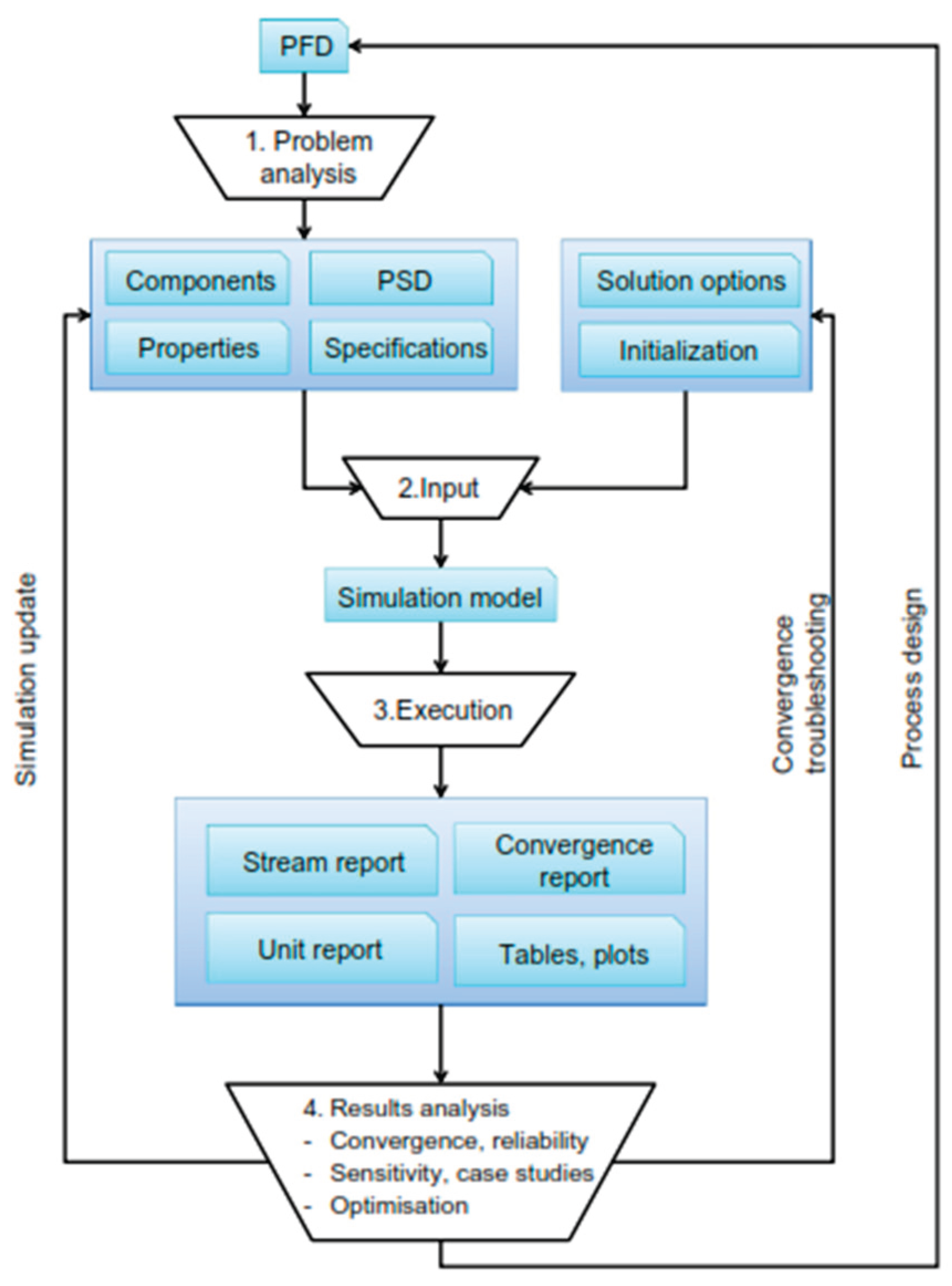

2.1. Proposal for the Design of the Technological Process

2.2. Proposal for the Design of the Technological Process

3. Results

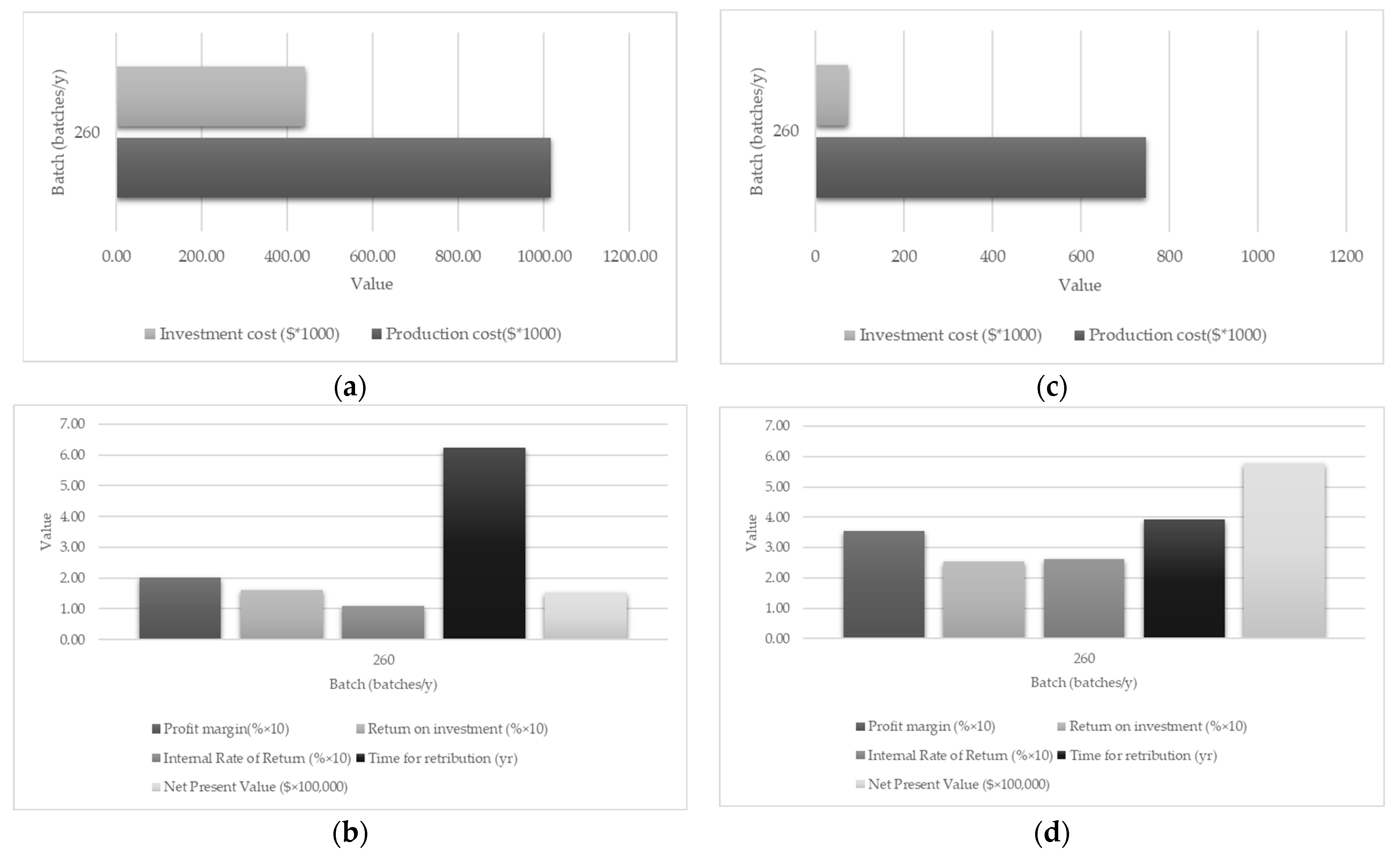

3.1. Proposal for the Design of the Technological Process

3.1.1. Product in Demand

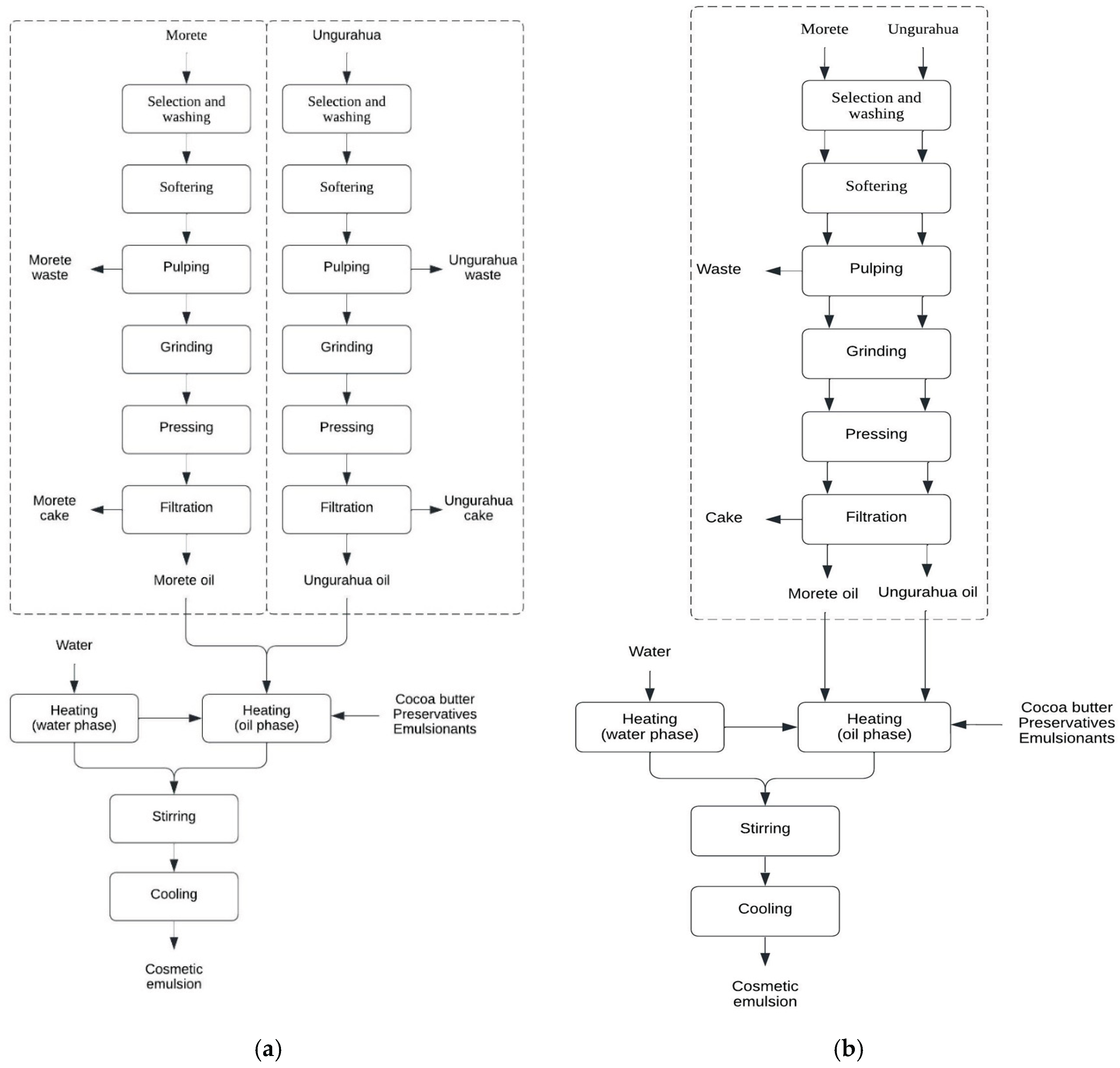

3.1.2. Technology Selection

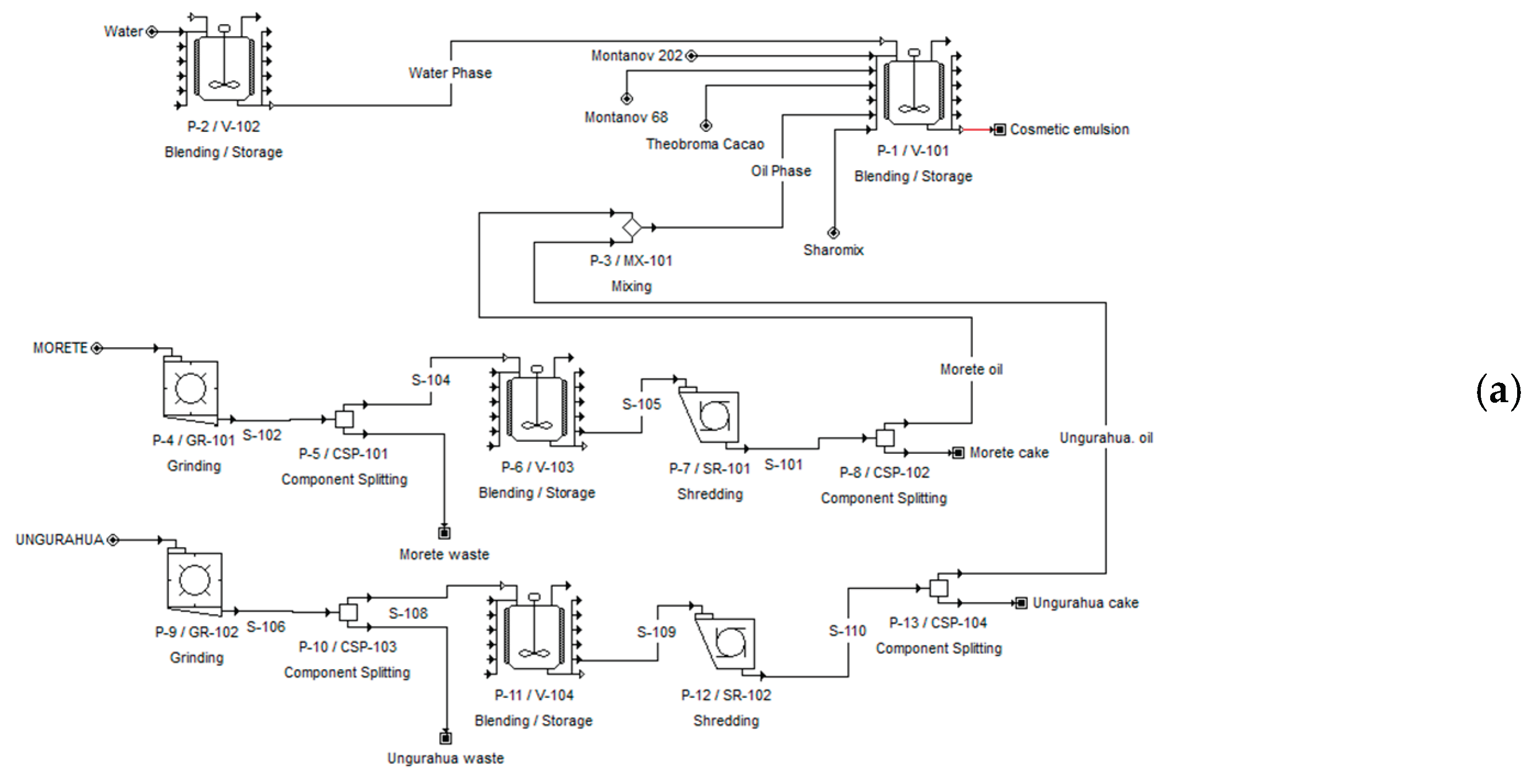

3.1.3. The Technological Scheme

3.1.4. Production Capacity Estimation

3.1.5. Location

3.1.6. Mass and Energy Balances, and Environmental Compatibility

3.1.7. Sizing and Cost of Acquisition of Equipment

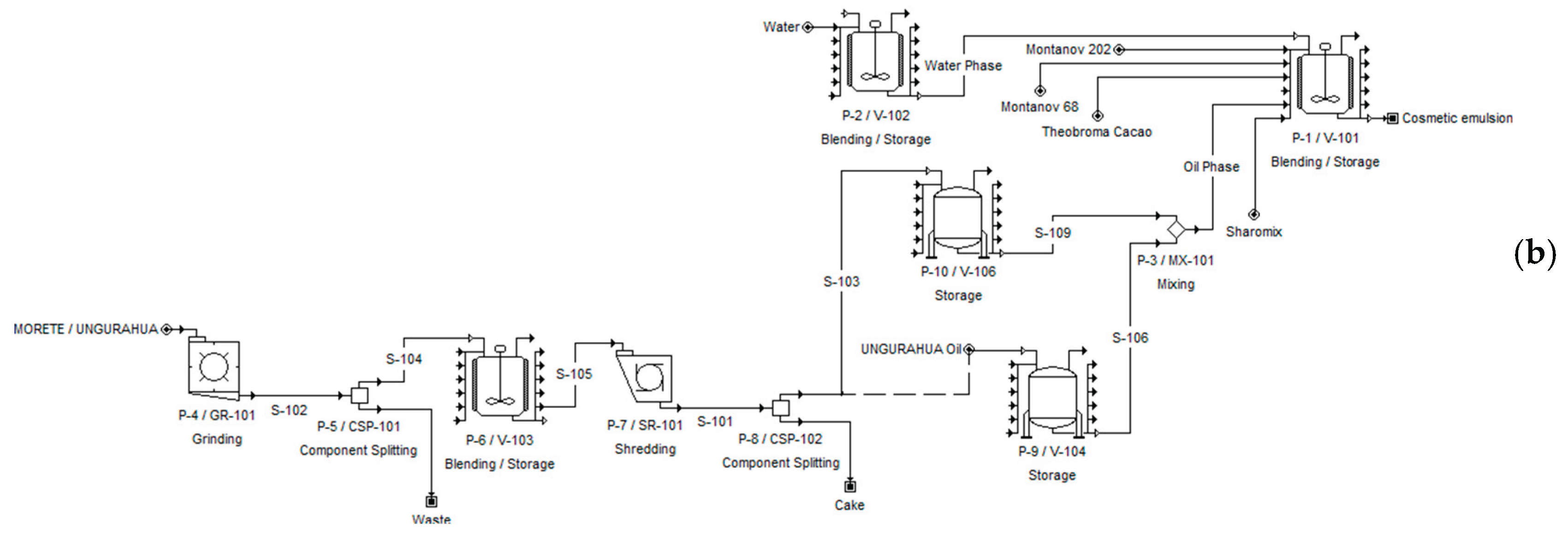

3.1.8. Economic Analysis and Feasibility

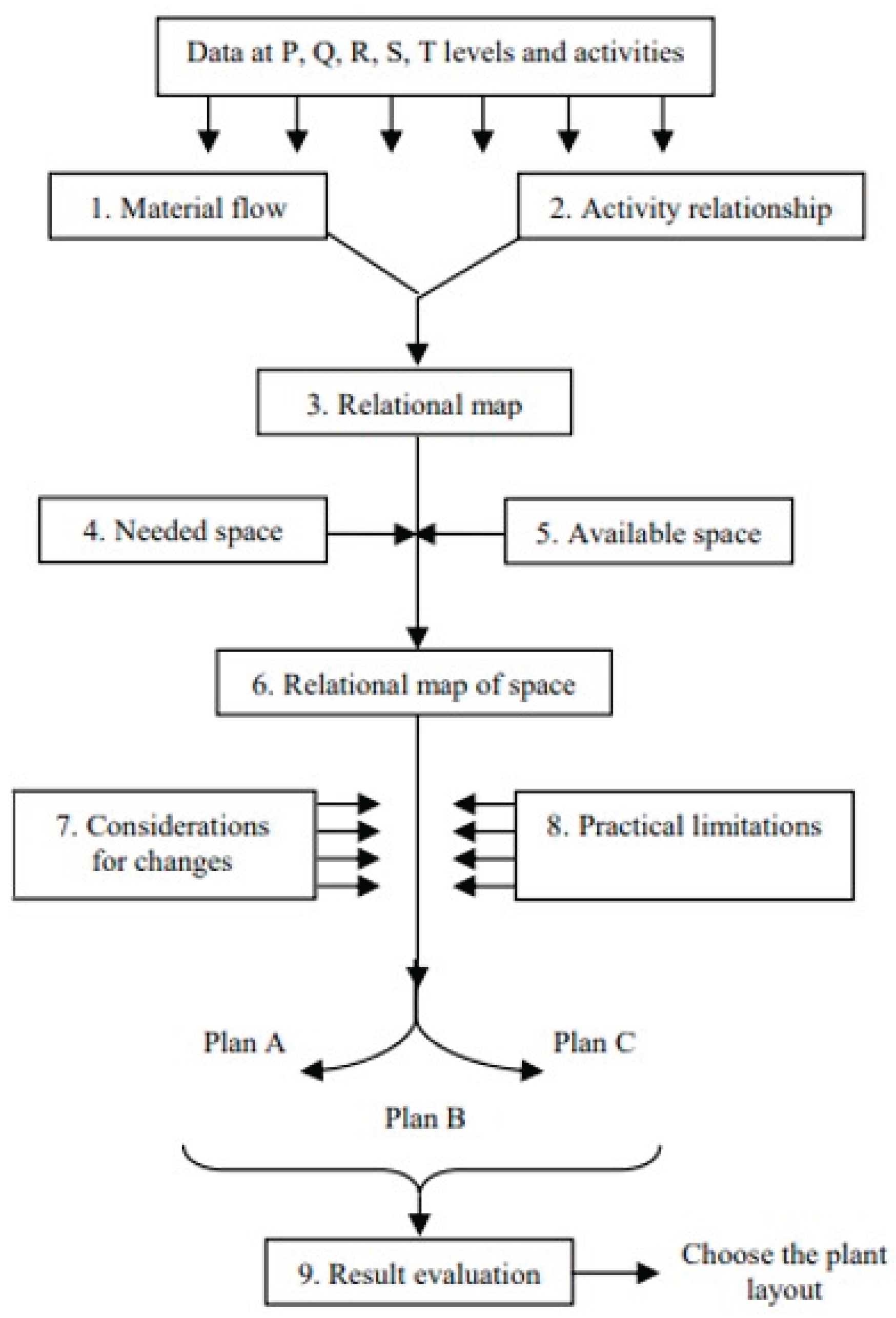

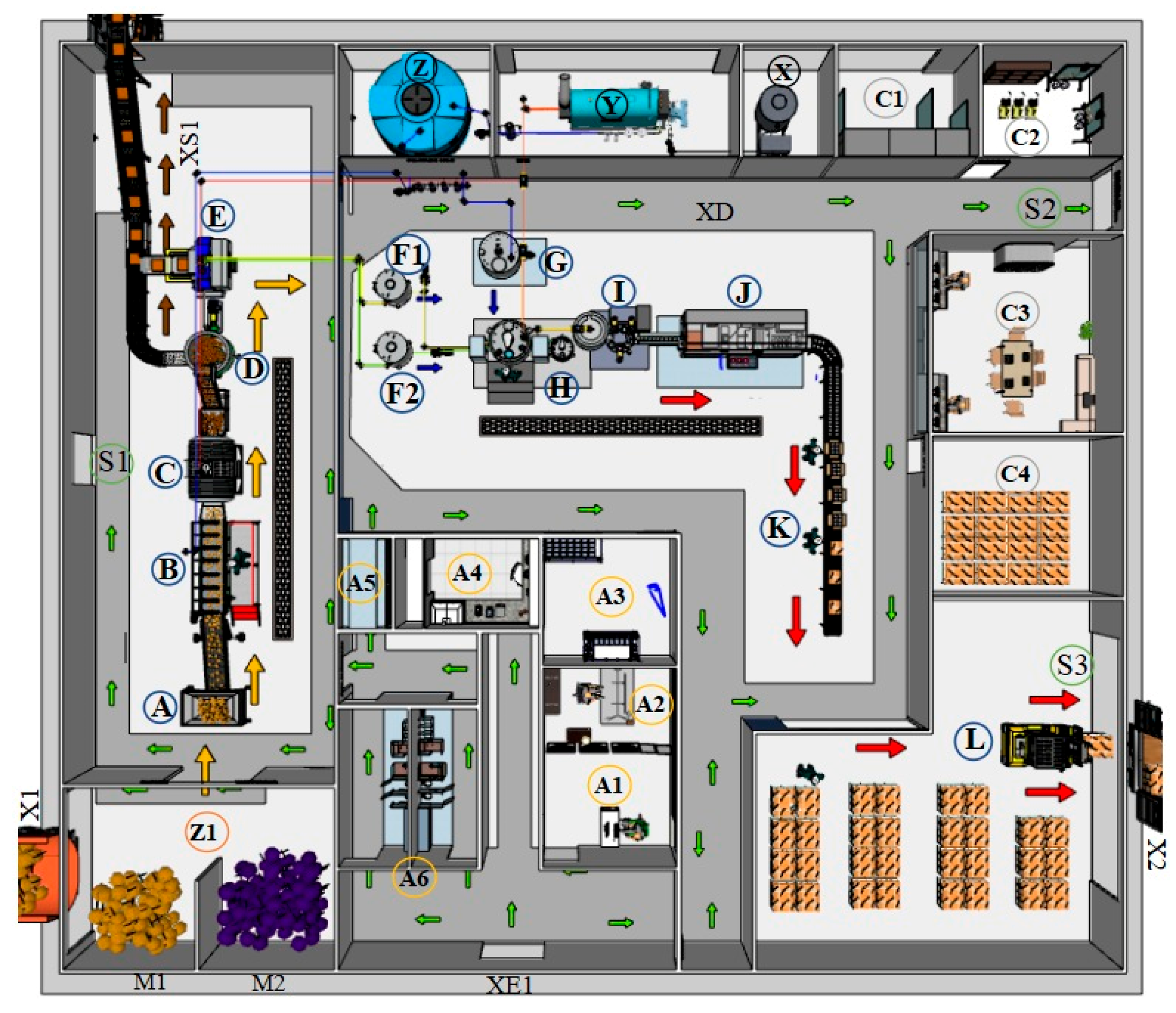

3.2. Plant Layout

3.2.1. Principle of Integration

3.2.2. Principle of the Minimum Distance Traveled

3.2.3. Principle of the Minimum Distance Traveled

3.2.4. Cubic Space Principle

3.2.5. Principle of Satisfaction and Security

3.2.6. Principle of Flexibility

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferreira, M.; Matos, A.; Couras, A.; Marto, J.; Ribeiro, H. Overview of Cosmetic Regulatory Frameworks around the World. Cosmetics 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruilova Accini, P.V.; Sempertegui Seminario, C.A.; Guerrero Muñoz, M.K. Calidad Del Servicio de Las Empresas Asociadas a La Industria Cosmética En El Ecuador. Sociedad & Tecnología 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancheno Saá, M.; Gamboa Salinas, M.J. El Branding Como Herramienta Para El Posicionamiento En La Industria Cosmética. Universidad y Sociedad 2018, 10, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Basurto Jimbo, E.; García Mir, V.; Rueda Rodríguez, E.; Noles Ramón, K. Elaboración de Una Crema Cosmética a Partir de Extractos Coriandrum Sativum L. (Culantro). Publicación Cuatrimestral 2021, 6, 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cobos Yanez, D.B. Elaboración de Una Crema Nutritiva Facial a Base de La Pulpa de Chirimoya (Annona Cherimola, Annonaceae), Quito, 2015.

- Capp Zilles, J.; Vallenot Lemos, M.A.; Anders Apel, M.; Kulkamp-Guerreiro, I.C.; Rigon Zimmer, A.; Vidor Contri, R. Vegetable Oils in Skin Whitening - A Narrative Review. Curr Pharm Des 2025, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jašek, V.; Figalla, S. Vegetable Oils for Material Applications - Available Biobased Compounds Seeking Their Utilities. ACS Polymers Au 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pupiales Martínez, S.A.; Torres Cando, T.E. Obtención de Aceites Esenciales a Partir de Pino (Pinus), Eucalipto (Eucalyptus), Menta (Mentha), Caléndula (Caléndula Officinalis), y Su Aplicación En La Elaboración de Una Crema Con Fines Terapéuticos Fines Terapéuticos, Guaranda, 2023.

- Madurga, M. El Papel de La Cosmética: Excipientes y Conservantes. Revista de Pediatría de Atención Primaria.

- Montalván, M.; Malagón, O.; Cumbicus, N.; Tanitana, F.; Gilardoni, G. Análisis Químico de Aceites Esenciales Amazónicos de Una Comunidad Shuar Ecuatoriana. Granja 2023, 38, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, G.A. Aceites Vegetales, Hacia Una Producción Sostenible. El Hombre y la Máquina 2015, 46, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Guardado Yordi, E.; Radice, M.; Scalvenzi, L.; Pérez Martínez, A. Diseño Del Proceso Sostenible Para La Obtención de Una Emulsión Cosmética Desde Un Enfoque de Biocomercio. Revista Politécnica 2024, 54, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, T.; Noriega, P.; Tapia, W.; Pérez, S.H. Evaluación de La Eficacia Cosmética de Cremas Elaboradas Con Aceites Extraídos de Especies Vegetales Amazónicas: Mauritia Flexuosa (Morete), Plukenetia Volubilis (Sacha Inchi) y Oenocarpus Bataua (Ungurahua). La Granja 2012, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proaño, J.; Rivadeneira, E.; Moncayo, P.; Mosquera, E. Aceite de Maracuyá (Passiflora Edulis): Aprovechamiento de Las Semillas En Productos Cosméticos. Enfoque UTE 2020, 11, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.; Luna, S.; Rodríguez, N.; Dahua, R. Evaluación de Las Propiedades Antioxidantes y Físicas de Una Crema Exfoliante Desarrollada a Partir de La Cáscara de Mauritia Flexuosa L. (Morete). Polo del Conocimiento 2024, 9, 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.A.; Gómez-García, R.; Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Madureira, A.R.; Pintado, M.M. Management of Fruit Industrial By-products—a Case Study on Circular Economy Approach. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Rio Osorio, L.L.; Flórez-López, E.; Grande-Tovar, C.D. The Potential of Selected Agri-Food Loss and Waste to Contribute to a Circular Economy: Applications in the Food, Cosmetic and Pharmaceutical Industries. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, M.; Silva, S.; Costa, E.M. Byproducts as a Sustainable Source of Cosmetic Ingredients. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondello, A.; Salomone, R.; Mondello, G. Exploring Circular Economy in the Cosmetic Industry: Insights from a Literature Review. Environ Impact Assess Rev 2024, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardado Yordi, E.; Sofia, I.; Guaman, G.; Elizabeth, M.; Fuentes, F.; Radice, M.; Scalvenzi, L.; Abreu-Naranjo, R.; Ramón Bravo Sánchez, L.; Pérez Martínez, A. Conceptual Design of the Process for Making Cosmetic Emulsion Using Amazonian Oils. 13. [CrossRef]

- Romero, D.; Aillón, F.; Freire, A.; Radice, M. Design of an Industrial Process Focused on the Elaboration of Cosmetics from Amazonian Oils: A Biotrade Opportunity. Mol2Net 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda-Mejía, V.; González-Suárez, E.; Guardado-Yordi, E.; Cerda-Mejía, G.; Pérez Martínez, A. Producción de Gel Hidroalcohólico En Tiempos de COVID-19, Oportunidad Para Diseñar El Proceso Que Garantice La Calidad. Centro Azúcar 2021, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Chacón, J.P.; Aguayo Carvajal, V.R. Estudio Técnico: Localización y Diseño de Plantas Agroindustriales. Brazilian Journal of Business 2022, 4, 1951–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Cortina, J. Contribución al Estudio de La Intensificación Del Proceso de Secado de Tomillo (Thymus Vulgaris l.): Aplicación de Ultrasonidos de Potencia y Secado Intermitente, 2013.

- Rodríguez Barragán, Ó.A. Intensificacion de Procesos de Transferencia de Materia Mediante Ultrasonidos de Potencia. Aplicacion al Secado Convectivo y a La Extraccion Con Fluidos Supercriticos, 2014, Vol. 3.

- Dimian, A.C. Integrated Design and Simulation of Chemical Processes.; R., Gani, Ed.; primera.; Elsevier: USA-Amsterdam The Netherlands, 2003; ISBN 978-0-444-62700-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Martinez, A.; Cervantes-Mendieta, E.; M. C., J.-R.; González-Suárez, E.; Gómez-Atanay, A.; Oquendo-Ferrer, H.; Galindo-Llanes, P.; Ramos-Sánchez, L. Procedimiento Para Enfrentar Tareas de Diseño de Procesos de La Industria Azucarera y Sus Derivados. Rev Mex Ing Quim 2012, 11, 333–349. [Google Scholar]

- Dimian, A.C.; Bildea, C.S.; Kiss, A.A. Chapter 2 - Introduction in Process Simulation. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Elsevier: USA-Amsterdam The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dimian, A.C.; Bildea, C.S.; Kiss, A.A. Chapter 2 - Introduction in Process Simulation. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Elsevier: USA-Amsterdam The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Muther, R. Planificación y Proyección de La Empresa Industrial: (Método S.P.L., Sistematic Layout Planning).; Carreras Fontseré, L., Ed.; Primera.; Editores Técnicos Asociados, S.A.: Kansas City, Missouri (U.S.A.), 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Suhardini, D.; Septiani, W.; Fauziah, S. Design and Simulation Plant Layout Using Systematic Layout Planning. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2017, 277, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Arias, D.; De Ávila Moore, J.; Hurtado Rivera, J. Aplicación de Metodología SLP Para Redistribución de Planta En Micro Empresa Colombiana Del Sector Marroquinero: Un Estudio de Caso. Boletín de Innovación, Logística y Operaciones 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnet, S.H.; Silva, L.H.M. da; Rodrigues, A.M. da C.; Lins, R.T. Nutritional Composition, Fatty Acid and Tocopherol Contents of Buriti (Mauritia Flexuosa) and Patawa (Oenocarpus Bataua) Fruit Pulp from the Amazon Region. Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos 2011, 31, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, I.; Olivera-Montenegro, L.; Cartagena-Gonzales, Z.; Arana-Copa, O.; Zabot, G. Techno-Economic Evaluation of the Production of Oil and Phenolic-Rich Extracts from Mauritia Flexuosa L. In f. Using Sequential Supercritical and Conventional Solvent Extraction. In Proceedings of the The 2nd International Electronic Conference on Foods—; “Future Foods and Food Technologies for a Sustainable World” MDPI: Basel Switzerland, October 14, 2021; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Stankiewicz, A.I.; Moulijn, J.A. Process Intensification: Transforming Chemical Engineering. Chem Eng Prog 2000, 96, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, J.B.; Martins, A.M.; Almeida, C.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Marto, J. Water Sustainability: A Waterless Life Cycle for Cosmetic Products. Sustain Prod Consum 2022, 32, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancuța, P.; Sonia, A. Oil Press-Cakes and Meals Valorization through Circular Economy Approaches: A Review. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 7432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environmental Indicator | Input/Output Current | Amount | Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional technology | Intensified technology | |||

| Raw material consumption | Montanov 68 | 0.011 | 0.011 | kg/kg |

| Montanov 202 | 0.036 | 0.036 | kg/kg | |

| Morete fruit | 0.136 | 0.136 | kg/kg | |

| Sharomix | 0.011 | 0.011 | kg/kg | |

| Cocoa butter | 0.111 | 0.111 | kg/kg | |

| Ungurahua fruit | 0.563 | 0.563 | kg/kg | |

| Water consumption | Water | 48.411 | 48.411 | kg/kg |

| Energy consumption | Power consumption | 5.86 | 5.86 | kW⋅h/kg |

| Steam consumption | 10 | 10 | kg/kg | |

| Refrigerated water | 260 | 260 | kg/kg | |

| Discharge | Of gases | - | - | - |

| Of liquids | - | - | - | |

| Of solids | 0.56 | 0.56 | kg/kg | |

| Cosmetic emulsion | 4717.48 | 4717.48 | kg/yr | |

| Quantity | Name | Design Parameter | Cost (USD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional technology | Intensified technology | |||

| 1 | Turbo-emulsifier | Tank volume = 22.47 L | 20 000 | 20 000 |

| 1 | Turbo-emulsifier | Tank volume = 14.66 L | 20 000 | 20 000 |

| 1 | Pulper | Nominal Yield = 2.55 kg/h | 14 000 | 14 000 |

| 1 | Pulper | Nominal Yield = 10.58 kg/h | 14 000 | |

| 1 | Jacketed tank | Tank volume = 2.62 L | 10 000 | 10 000 |

| 1 | Jacketed tank | Tank volume = 8.95 L | 10 000 | |

| 1 | Shredder | Nominal Yield = 2.55 kg/h | 1 000 | 6 000 |

| 1 | Shredder | Nominal Yield = 2.16 kg/h | 1 000 | |

| 1 | Press | Nominal Yield = 12.98 kg/h | 6 000 | |

| 1 | Press | Nominal Yield = 45.82 kg/h | 6 000 | |

| 1 | Storage tank | Tank volume = 1.11 L | - | 1 000 |

| 1 | Storage tank | Tank volume = 2.58 L | - | 1 000 |

| Equipment not listed | 25 000 | 18 000 | ||

| Total | 126 000 | 88 000 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).