Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

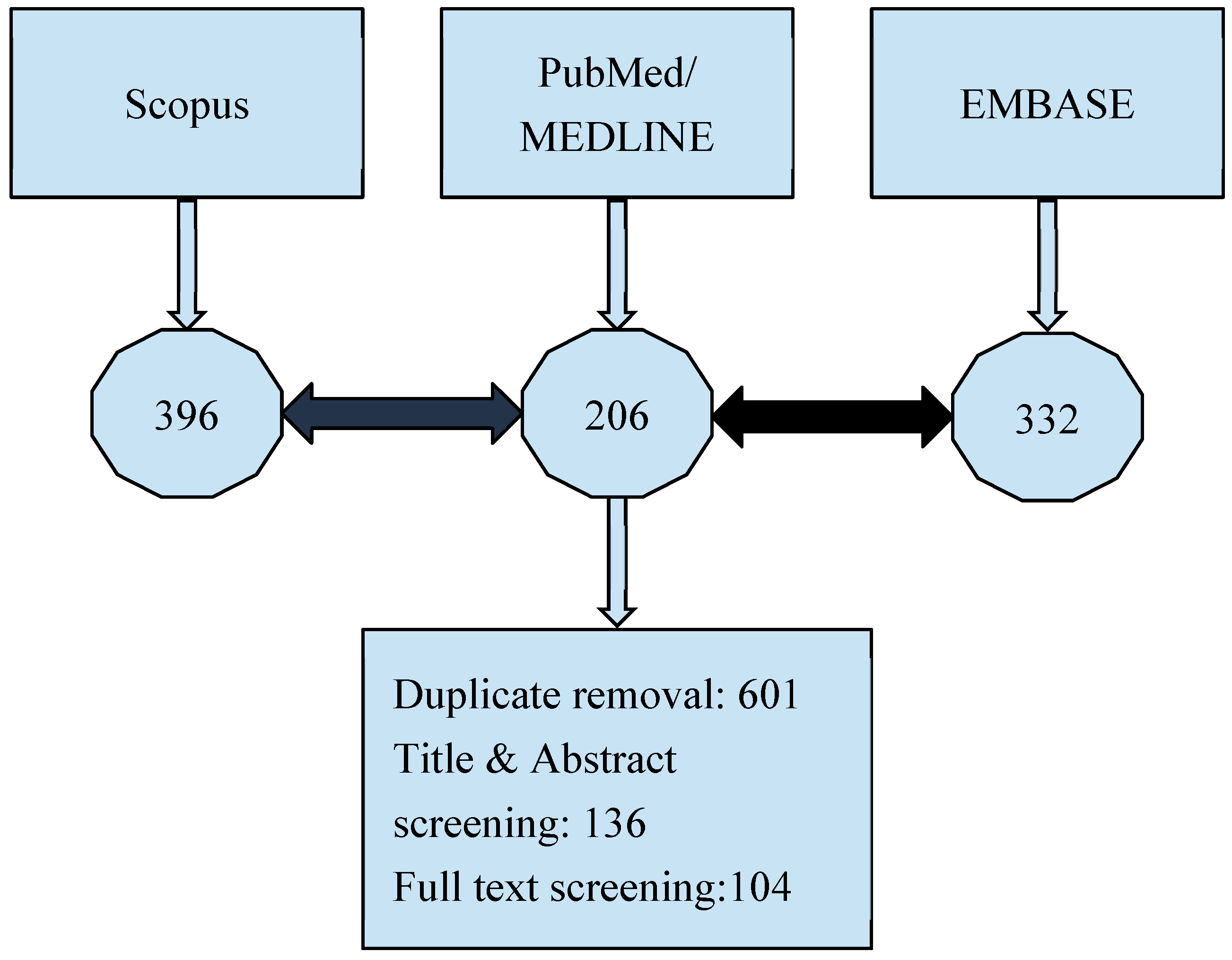

2. Materials and Methods

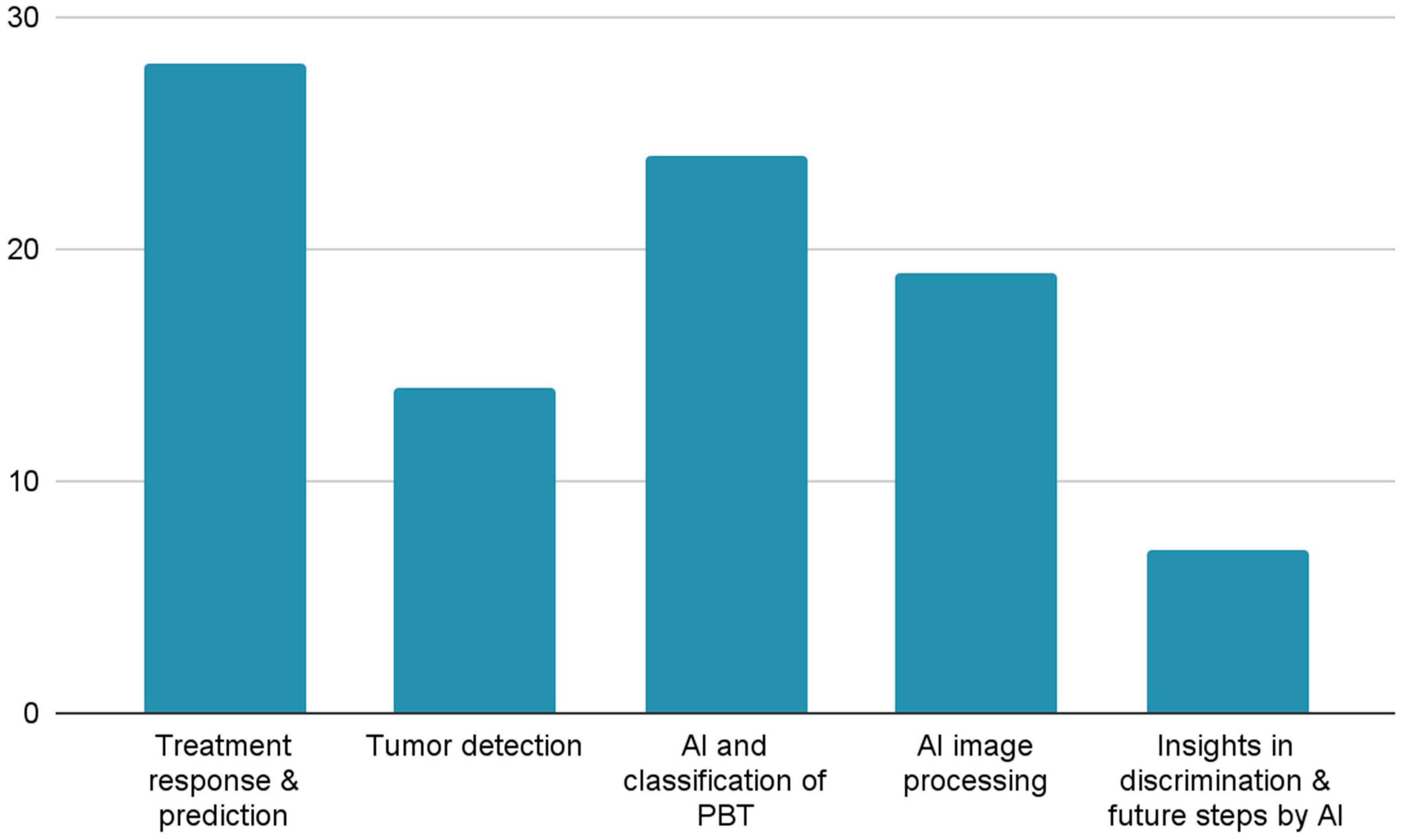

3. Results

4. Discussion

Treatment Response & Prediction

Tumor Detection

AI and Classification of PBT

Tumor Segmentation

Insights in Discrimination and Future Steps by AI

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| PBT | Primary Bone Tumors |

| NAC | Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| RS | Radiomics Signature |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| LR | Logic Recession |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| DCA | Decision Curve Analysis |

| DLRM | Deep Learning Radiomics Model |

| DIaL | Deep Learning Interactive Model |

| DS-Net | Deep Supervision Network |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| 18F-FDG | Fluorine 18 Fluorodeoxyglucose |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| DWI | Diffusion-Weighted Imaging |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| EPI | Edge Presence Index |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| ROI | Region Of Interest |

| T2WI | T2 Weighted Imaging |

| T1CE | T1 Weighted Contrast-Enhanced Imaging |

| KNN | K Nearest Neighbor |

| NAC | Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy |

| DCE-MRI | Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| SUVmax | Maximum Standardized Uptake Value |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| VGG16 | Visual Geometry Group 16 layer Network |

| VGG19 | Visual Geometry Group 19 layer Network |

| DenseNet201 | Densely Connected Convolutional Network 201 Layers |

| ResNet101 | Residual Network 101 Layers |

| NASNetLarge | Neural Architecture Search Network Large |

| EfficientNetV2L | Efficient Network Version 2 Large |

| IF-FSM-C | Inception Framework with Feature Selection Mechanism for Classification |

| BCDNet | Bone Cancer Detection Network |

| GCT | Giant Cell Tumor |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| ChatGPT-4 | Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4 |

| U-net | U-shaped Convolutional Network |

| DUconViT | Dual Convolutional Vision Transformer |

| Mask R-CNN | Mask Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network |

| PCA-IPSO | Principal Component Analysis Improved Particle Swarm Optimization |

| DECIDE | Deep Ensemble Classifier with Integration of Dual Enhancers |

| Grad-CAM | Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| CATS | Computer-Assisted Tumor Surgery |

References

- Vogrin, M.; Trojner, T.; Kelc, R. Artificial Intelligence in Musculoskeletal Oncological Radiology. Radiol Oncol 2020, 55, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdem, F.; Tamsel, İ.; Demirpolat, G. The Use of Radiomics and Machine Learning for the Differentiation of Chondrosarcoma from Enchondroma. J Clin Ultrasound 2023, 51, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X. Artificial Intelligence-Based Radiomics in Bone Tumors: Technical Advances and Clinical Application. Semin Cancer Biol 2023, 95, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Yang, H.; Lin, B.; Wang, M.; Song, L.; Xie, Z.; Lu, Z.; Feng, Q.; Zhao, Y. Automatic Detection, Segmentation, and Classification of Primary Bone Tumors and Bone Infections Using an Ensemble Multi-Task Deep Learning Framework on Multi-Parametric MRIs: A Multi-Center Study. Eur Radiol 2024, 34, 4287–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emil, N.S.; Sibbitt, R.R.; Sibbitt, W.L., Jr. Machine Learning and Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Differentiating Benign from Malignant Osseous Tumors. J Clin Ultrasound 2023, 51, 1036–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, M.; Yildirim, H. CT Radiomics-Based Machine Learning Model for Differentiating between Enchondroma and Low-Grade Chondrosarcoma. Med. Baltim. 2024, 103, e39311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Yin, P.; Liang, K.; Wang, Y.; Hao, W.; Hao, Q.; Hong, N. Fusion Radiomics-Based Prediction of Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Osteosarcoma. Acad Radiol 2024, 31, 2444–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, E.; Sanelli, P.C.; Aboian, M.; Payabvash, S. Radiomics: A Primer on Processing Workflow and Analysis. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI 2022, 43, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.D.; Ahmed, S.R.; Choy, E.; Lozano-Calderon, S.A.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Chang, C.Y. Artificial Intelligence Applied to Musculoskeletal Oncology: A Systematic Review. Skelet. Radiol 2022, 51, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitto, S.; Corino, V.; Bologna, M.; Marzorati, L.; Milazzo Machado, E.; Albano, D.; Messina, C.; Mainardi, L.; Sconfienza, L.M. MRI Radiomics-Based Machine Learning to Predict Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Ewing Sarcoma. Insights Imaging 2022, 14, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitto, S.; Corino, V.D.A.; Annovazzi, A.; Milazzo Machado, E.; Bologna, M.; Marzorati, L.; Albano, D.; Messina, C.; Serpi, F.; Anelli, V.; et al. 3D vs. 2D MRI Radiomics in Skeletal Ewing Sarcoma: Feature Reproducibility and Preliminary Machine Learning Analysis on Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response Prediction. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 1016123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Yang, P.F.; Chen, S.; Shao, Y.Y.; Xu, L.; Wu, Y.; Teng, W.; Zhou, X.Z.; Li, B.H.; Luo, C.; et al. A Delta-Radiomics Model for Preoperative Evaluation of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in High-Grade Osteosarcoma. Cancer Imaging 2020, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Xie, L.; Sun, X.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, R.; Sun, K.; Shen, D.; Gu, J.; Ji, T.; et al. A Scoring System for Predicting Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Primary High-Grade Bone Sarcomas: A Multicenter Study. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 14, 2499–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhang, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Si, L.; Xing, Y.; Ding, D.; Geng, J.; Jiao, Q.; et al. Automated Prediction of the Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Osteosarcoma with Deep Learning and an MRI-Based Radiomics Nomogram. Eur Radiol 2022, 32, 6196–6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Zhao, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Dai, Z.; Wu, J.; et al. Can the Preoperative CT-Based Deep Learning Radiomics Model Predict Histologic Grade and Prognosis of Chondrosarcoma? Eur J Radiol 2024, 181, 111719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, K.Y.; Daescu, O.; Cederberg, K.; Sengupta, A.; Leavey, P.J. Correlation of Histopathology and Multi-Modal Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Childhood Osteosarcoma: Predicting Tumor Response to Chemotherapy. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0259564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.J.; Agaram, N.P.; Schüffler, P.J.; Vanderbilt, C.M.; Jean, M.-H.; Hameed, M.R.; Fuchs, T.J. Deep Interactive Learning: An Efficient Labeling Approach for Deep Learning-Based Osteosarcoma Treatment Response Assessment.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2020; Vol. 12265 LNCS, pp. 540–549.

- Fu, Y.; Xue, P.; Ji, H.; Cui, W.; Dong, E. Deep Model with Siamese Network for Viable and Necrotic Tumor Regions Assessment in Osteosarcoma. Med Phys 2020, 47, 4895–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Park, J.; Sheen, H.; Byun, B.H.; Lim, I.; Kong, C.-B.; Lim, S.M.; Woo, S.-K. Development of Deep Learning Model for Prediction of Chemotherapy Response Using PET Images and Radiomics Features.; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2018.

- Hu, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhao, S.; Li, Y. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging-Magnetic Resonance Imaging Information under Class-Structured Deep Convolutional Neural Network Algorithm in the Prognostic Chemotherapy of Osteosarcoma. Sci Program 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuričić, G.J.; Ahammer, H.; Rajković, S.; Kovač, J.D.; Milošević, Z.; Sopta, J.P.; Radulovic, M. Directionally Sensitive Fractal Radiomics Compatible With Irregularly Shaped Magnetic Resonance Tumor Regions of Interest: Association With Osteosarcoma Chemoresistance. J Magn Reson Imaging 2023, 57, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, Q.; Dou, Y.; Cheng, T.; Xia, Y.; Li, H.; Gao, S. Evaluation of the Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Osteosarcoma Using the MRI DWI-Based Machine Learning Radiomics Nomogram. Front Oncol 2024, 14, 1345576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wang, J.; Sun, M.; Chen, X.; Xu, D.; Li, Z.P.; Ma, J.; Feng, S.T.; Gao, Z. Feasibility of Multi-Parametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging Combined with Machine Learning in the Assessment of Necrosis of Osteosarcoma after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: A Preliminary Study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ge, Y.; Gao, Q.; Zhao, F.; Cheng, T.; Li, H.; Xia, Y. Machine Learning-Based Radiomics Nomogram With Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI of the Osteosarcoma for Evaluation of Efficacy of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 758921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhi, L.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Chen, G.; Yin, S. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Radiomics Predicts Histological Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Localized High-Grade Osteosarcoma of the Extremities. Acad. Radiol. 2024, 31, 5100–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Ren, H.; Mori, N.; Watanuki, M.; Hitachi, S.; Watanabe, M.; Mugikura, S.; Takase, K. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Texture Analysis Based on Intraosseous and Extraosseous Lesions to Predict Prognosis in Patients with Osteosarcoma. Diagnostics 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Quan, X.; Deng, Y.; Lu, M.; Wei, Q.; Ye, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Xiang, Z.; et al. MRI-Based Radiomics Signature for Pretreatment Prediction of Pathological Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Osteosarcoma: A Multicenter Study. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 7913–7924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedler, J.; Schaal, M.; Götz, M.; Cario, H.; Beer, M. Potential Role of MRI-Based Radiomics in Prediction of Chemotherapy Response in Pediatric Patients with Ewing-Sarcoma. Pediatr. Radiol. 2023, 53, S163–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaber, R.; Arthur, C.J.; Łach, K.; Raciborska, A.; Michalak, E.; Bilska, K.; Drabko, K.; Depciuch, J.; Kaznowska, E.; Cebulski, J. Predicting Ewing Sarcoma Treatment Outcome Using Infrared Spectroscopy and Machine Learning. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufau, J.; Bouhamama, A.; Leporq, B.; Malaureille, L.; Beuf, O.; Gouin, F.; Pilleul, F.; Marec-Berard, P. Prediction of Chemotherapy Response in Primary Osteosarcoma Using the Machine Learning Technique on Radiomic Data. Bull. Cancer (Paris) 2019, 106, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.Y.; Kim, W.; Byun, B.H.; Kong, C.B.; Song, W.S.; Lim, I.; Lim, S.M.; Woo, S.K. Prediction of Chemotherapy Response of Osteosarcoma Using Baseline (18)F-FDG Textural Features Machine Learning Approaches with PCA. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2019, 2019, 3515080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhamama, A.; Leporq, B.; Khaled, W.; Nemeth, A.; Brahmi, M.; Dufau, J.; Marec-Bérard, P.; Drapé, J.L.; Gouin, F.; Bertrand-Vasseur, A.; et al. Prediction of Histologic Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Osteosarcoma Using Pretherapeutic MRI Radiomics. Radiol Imaging Cancer 2022, 4, e210107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jeong, S.Y.; Kim, B.C.; Byun, B.H.; Lim, I.; Kong, C.B.; Song, W.S.; Lim, S.M.; Woo, S.K. Prediction of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Osteosarcoma Using Convolutional Neural Network of Tumor Center (18)F-FDG PET Images. Diagn. Basel 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helen, R.; Gurumoorthy, G.; Thennarasu, S.R.; Sakthivel, P.R. Prediction of Osteosarcoma Using Binary Convolutional Neural Network: A Machine Learning Approach.; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024.

- Im, H.-J.; McIlwain, S.; Ong, I.; Lee, I.; Song, C.; Shulkin, B.; Cho, S. Prediction of Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Using Machine Learning Algorithm Trained by Baseline FDG-PET Textural Parameters in Osteosarcoma. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Sheen, H.; Kim, W.; Byun, B.H.; Kong, C.-B.; Lim, I.; Lim, S.M.; Woo, S.-K. Prognostic and Predictive Logistic Model for Osteosarcoma Using Metabolic Imaging Phenotypes. J. Nucl. Med. 2019, 60. [Google Scholar]

- White, L.M.; Atinga, A.; Naraghi, A.M.; Lajkosz, K.; Wunder, J.S.; Ferguson, P.; Tsoi, K.; Griffin, A.; Haider, M. T2-Weighted MRI Radiomics in High-Grade Intramedullary Osteosarcoma: Predictive Accuracy in Assessing Histologic Response to Chemotherapy, Overall Survival, and Disease-Free Survival. Skelet. Radiol 2023, 52, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, K.; Rajagopal, S.; Chintanpalli, A. A Comparative Analysis of CNN-Based Deep Learning Architectures for Early Diagnosis of Bone Cancer Using CT Images. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, S.; Guo, J.; Hao, D.; Hou, F.; Wang, H.; Xu, W. A CT-Based Radiomics Nomogram for Distinguishing between Benign and Malignant Bone Tumours. Cancer Imaging 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartín, J.; Azuero, P.; Hurtado, R. A Modern Approach to Osteosarcoma Tumor Identification Through Integration of FP-Growth, Transfer Learning and Stacking Model.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2024; Vol. 932 LNNS, pp. 298–307.

- Gawade, S.; Bhansali, A.; Patil, K.; Shaikh, D. Application of the Convolutional Neural Networks and Supervised Deep-Learning Methods for Osteosarcoma Bone Cancer Detection. Healthc. Anal. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Gehlot, K.; Singhal, A.; Gupta, A. Automatic Detection of Osteosarcoma Based on Integrated Features and Feature Selection Using Binary Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm. Multimed. Tools Appl 2022, 81, 8807–8834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.; Qian, J.; Wang, X. Auxiliary Diagnosis of Primary Bone Tumors Based on Machine Learning Model. J. Bone Oncol. 2024, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.D.; Madhavi, K. BCDNet: A Deep Learning Model with Improved Convolutional Neural Network for Efficient Detection of Bone Cancer Using Histology Images. Int J Comput Exp Sci Eng 2024, 10, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Lin, H.; Ding, L.; Li, B.; Xu, D.; Sun, Y.; Guan, T.; Dai, H.; Liu, R.; Deng, D.; et al. Deep Learning for Differentiation of Osteolytic Osteosarcoma and Giant Cell Tumor around the Knee Joint on Radiographs: A Multicenter Study. Insights Imaging 2024, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Shen, Y.; Zeng, F.; Wang, M.; Li, B.; Shen, D.; Tang, X.; Wang, B. Exploiting Biochemical Data to Improve Osteosarcoma Diagnosis with Deep Learning. Health Inf Sci Syst 2024, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Jiang, L.; Xiang, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhao, Z.; Cai, H.; Yi, Z.; Li, L. Deep-Learning Model for Differentiation of Pediatric Bone Diseases by Bone Scintigraphy: A Feasibility Study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2023, 50, S727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Guo, Y.; He, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Huang, Q.; Yang, L. Exploring Whether ChatGPT-4 with Image Analysis Capabilities Can Diagnose Osteosarcoma from X-Ray Images. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loraksa, C.; Mongkolsomlit, S.; Nimsuk, N.; Uscharapong, M.; Kiatisevi, P. Effectiveness of Learning Systems from Common Image File Types to Detect Osteosarcoma Based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) Models. J Imaging 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasei, J.; Nakahara, R.; Otsuka, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Hironari, T.; Kahara, N.; Miwa, S.; Ohshika, S.; Nishimura, S.; Ikuta, K.; et al. High-Quality Expert Annotations Enhance Artificial Intelligence Model Accuracy for Osteosarcoma X-Ray Diagnosis. Cancer Sci 2024, 115, 3695–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Yang, S.; Gou, F.; Dai, Z.; Wu, J. Intelligent Assistant Diagnosis System of Osteosarcoma MRI Image Based on Transformer and Convolution in Developing Countries. IEEE J Biomed Health Inf. 2022, 26, 5563–5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Ran, T.; Wu, H.; Wang, M.; Pan, J. The Development of Mask R-CNN to Detect Osteosarcoma and Oste-Ochondroma in X-Ray Radiographs. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. Imaging Vis. 2023, 11, 1869–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Li, C.; Tan, L.; Wang, M.; Chen, X.; Ye, Q.; Li, S.; Zhang, R.; Zeng, Q.; Xie, Z.; et al. A Deep Learning Model to Enhance the Classification of Primary Bone Tumors Based on Incomplete Multimodal Images in X-Ray, CT, and MRI. Cancer Imaging 2024, 24, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhao, H.; Song, L.; Ye, Q.; Zhong, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, M.; Chen, X.; Lu, Z.; et al. A Radiograph-Based Deep Learning Model Improves Radiologists’ Performance for Classification of Histological Types of Primary Bone Tumors: A Multicenter Study. Eur J Radiol 2024, 176, 111496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Pan, I.; Bao, B.; Halsey, K.; Chang, M.; Liu, H.; Peng, S.; Sebro, R.A.; Guan, J.; Yi, T.; et al. Deep Learning-Based Classification of Primary Bone Tumors on Radiographs: A Preliminary Study. EBioMedicine 2020, 62, 103121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obaid, M.K.; Abed, H.A.; Abdullah, S.B.; Al-Jawahry, H.M.; Majed, S.; Hassan, A.R. Automated Osteosarcoma Detection and Classification Using Advanced Deep Learning with Remora Optimization Algorithm.; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023; pp. 122–128.

- He, J.; Bi, X. Automatic Classification of Spinal Osteosarcoma and Giant Cell Tumor of Bone Using Optimized DenseNet. J Bone Oncol 2024, 46, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malibari, A.A.; Alzahrani, J.S.; Obayya, M.; Negm, N.; Al-Hagery, M.A.; Salama, A.S.; Hilal, A.M. Biomedical Osteosarcoma Image Classification Using Elephant Herd Optimization and Deep Learning. Comput Mater Contin. 2022, 73, 6443–6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahouma, K.H.; Abdellatif, A.S. Bone Osteosarcoma Tumor Classification. Indones J Electr. Eng Comput Sci 2023, 31, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Yang, F. Comprehensive Diagnostic Model for Osteosarcoma Classification Using CT Imaging Features. J Bone Oncol 2024, 47, 100622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgeanu, V.; Mamuleanu, M.-L.; Selisteanu, D. Convolutional Neural Networks for Automated Detection and Classification of Bone Tumors in Magnetic Resonance Imaging.; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2021; pp. 5–7.

- Sagar, C.V.; Bhan, A. Machine Learning Approach to Classify and Predict Osteosarcoma Grading.; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024; pp. 470–474.

- Gitto, S.; Albano, D.; Chianca, V.; Cuocolo, R.; Ugga, L.; Messina, C.; Sconfienza, L.M. Machine Learning Classification of Low-Grade and High-Grade Chondrosarcomas Based on MRI-Based Texture Analysis. Semin. Musculoskelet. Radiol. 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitto, S.; Cuocolo, R.; van Langevelde, K.; van de Sande, M.A.J.; Parafioriti, A.; Luzzati, A.; Imbriaco, M.; Sconfienza, L.M.; Bloem, J.L. MRI Radiomics-Based Machine Learning Classification of Atypical Cartilaginous Tumour and Grade II Chondrosarcoma of Long Bones. EBioMedicine 2022, 75, 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitto, S.; Cuocolo, R.; Albano, D.; Chianca, V.; Messina, C.; Gambino, A.; Ugga, L.; Cortese, M.C.; Lazzara, A.; Ricci, D.; et al. MRI Radiomics-Based Machine-Learning Classification of Bone Chondrosarcoma. Eur J Radiol 2020, 128, 109043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiyapuri, T.; Jothi, A.; Narayanasamy, K.; Kamatchi, K.; Kadry, S.; Kim, J. Design of a Honey Badger Optimization Algorithm with a Deep Transfer Learning-Based Osteosarcoma Classification Model. Cancers Basel 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Nayak, P.; Mithun, S.; Sherkhane, U.; Jaiswar, V.; Nath, B.; Tripathi, A.; Mehta, G.M.; Panchal, S.; Purandare, N.; et al. Development and Validation of Radiomic Signature for Classification of High and Low-Grade Chondrosarcoma: A Pilot Study. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2022, 24, S218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hua, Y.; Mao, M.; Cai, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Gryak, J.; Najarian, K. Osteosarcoma Patients Classification Using Plain X-Rays and Metabolomic Data. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2018, 2018, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Miao, S.; Dong, C.; Gao, C.; Liu, X.; Hao, D.; Xu, W.; Huang, M.; et al. Primary Bone Tumor Detection and Classification in Full-Field Bone Radiographs via YOLO Deep Learning Model. Eur Radiol 2023, 33, 4237–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadi, M.R.; Hassan, A.R.; Mohammed, I.H.; Alazzai, W.K.; Alzubaidi, L.H.; Ai Sadi, H.I. Integrated Design of Artificial Neural Network with Bald Eagle Search Optimization for Osteosarcoma Classification.; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023; pp. 552–558.

- Guo, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, J. Radiographic Imaging and Diagnosis of Spinal Bone Tumors: AlexNet and ResNet for the Classification of Tumor Malignancy. J Bone Oncol 2024, 48, 100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, B.; Yuan, P. The Diagnostic Value of Machine Learning for the Classification of Malignant Bone Tumor: A Systematic Evaluation and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitto, S.; Cuocolo, R.; Annovazzi, A.; Anelli, V.; Acquasanta, M.; Cincotta, A.; Albano, D.; Chianca, V.; Ferraresi, V.; Messina, C.; et al. CT Radiomics-Based Machine Learning Classification of Atypical Cartilaginous Tumours and Appendicular Chondrosarcomas. EBioMedicine 2021, 68, 103407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Liu, R.; Zheng, B.; Yuan, J.; Zeng, H.; He, Z.; Luo, Z.; Qin, G.; Chen, W. Using Machine Learning to Unravel the Value of Radiographic Features for the Classification of Bone Tumors. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Schacky, C.E.; Wilhelm, N.J.; Schäfer, V.S.; Leonhardt, Y.; Jung, M.; Jungmann, P.M.; Russe, M.F.; Foreman, S.C.; Gassert, F.G.; Gassert, F.T.; et al. Development and Evaluation of Machine Learning Models Based on X-Ray Radiomics for the Classification and Differentiation of Malignant and Benign Bone Tumors. Eur Radiol 2022, 32, 6247–6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitto, S.; Annovazzi, A.; Nulle, K.; Interlenghi, M.; Salvatore, C.; Anelli, V.; Baldi, J.; Messina, C.; Albano, D.; Di Luca, F.; et al. X-Rays Radiomics-Based Machine Learning Classification of Atypical Cartilaginous Tumour and High-Grade Chondrosarcoma of Long Bones. EBioMedicine 2024, 101, 105018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Schacky, C.E.; Wilhelm, N.J.; Schäfer, V.S.; Leonhardt, Y.; Gassert, F.G.; Foreman, S.C.; Gassert, F.T.; Jung, M.; Jungmann, P.M.; Russe, M.F.; et al. Multitask Deep Learning for Segmentation and Classification of Primary Bone Tumors on Radiographs. Radiology 2021, 301, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Hu, Y.; Ge, X.; Xing, Y.; Ding, D.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Q.; Yao, W. A Systematic Review of Radiomics in Chondrosarcoma: Assessment of Study Quality and Clinical Value Needs Handy Tools. Eur Radiol 2023, 33, 1433–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xiao, P.; Huang, H.; Gou, F.; Zhou, Z.; Dai, Z. An Artificial Intelligence Multiprocessing Scheme for the Diagnosis of Osteosarcoma MRI Images. IEEE J Biomed Health Inf. 2022, 26, 4656–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Liu, J.; Long, H.; Zhu, J.; Tang, H.; Gou, F.; Wu, J. An Intelligent Auxiliary Framework for Bone Malignant Tumor Lesion Segmentation in Medical Image Analysis. Diagn. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Gou, F.; Wu, J. An Intelligent MRI Assisted Diagnosis and Treatment System for Osteosarcoma Based on Super-Resolution. Complex Intell Syst 2024, 10, 6031–6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Nie, J.; Gou, F.; Wu, J. Artificial Intelligence-Aided Diagnosis Solution by Enhancing the Edge Features of Medical Images. Diagn. Basel 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, L.; Zhu, J.; Tang, H.; Gou, F.; Wu, J. Auxiliary Segmentation Method of Osteosarcoma in MRI Images Based on Denoising and Local Enhancement. Healthc. Basel 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhu, J.; Lv, B.; Yang, L.; Sun, W.; Dai, Z.; Gou, F.; Wu, J. Auxiliary Segmentation Method of Osteosarcoma MRI Image Based on Transformer and U-Net. Comput Intell Neurosci 2022, 2022, 9990092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Gou, F.; Zhu, J.; Tang, H.; Zhou, X.; Xiong, W. BA-GCA Net: Boundary-Aware Grid Contextual Attention Net in Osteosarcoma MRI Image Segmentation. Comput Intell Neurosci 2022, 2022, 3881833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.C.; Ling, A.H.W.; Chong, Y.F.; Mashor, M.Y.; Alshantti, K.; Aziz, M.E. Comparative Analysis of Image Processing Techniques for Enhanced MRI Image Quality: 3D Reconstruction and Segmentation Using 3D U-Net Architecture. Diagn. Basel 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, S. DECIDE: A Decoupled Semantic and Boundary Learning Network for Precise Osteosarcoma Segmentation by Integrating Multi-Modality MRI. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, S.; Gou, F.; Zhou, Z.; Xie, P.; Xu, N.; Dai, Z. Intelligent Segmentation Medical Assistance System for MRI Images of Osteosarcoma in Developing Countries. Comput Math Methods Med 2022, 2022, 7703583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionísio, F.C.F.; Oliveira, L.S.; Hernandes, M.A.; Engel, E.E.; Rangayyan, R.M.; Azevedo-Marques, P.M.; Nogueira-Barbosa, M.H. Manual and Semiautomatic Segmentation of Bone Sarcomas on MRI Have High Similarity. Braz J Med Biol Res 2020, 53, e8962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Huang, L.; Xia, W.; Zhang, B.; Qiu, B.; Gao, X. Multiple Supervised Residual Network for Osteosarcoma Segmentation in CT Images. Comput Med Imaging Graph 2018, 63, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Gou, F.; Dai, Z. Osteosarcoma MRI Image-Assisted Segmentation System Base on Guided Aggregated Bilateral Network. Mathematics 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørum, L.; Banke, K.; Borgwardt, L.; Hansen, A.; Højgaard, L.; Andersen, F.; Ladefoged, C. Pediatric Sarcoma Segmentation Using Deep Learning. J. Nucl. Med. 2019, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, C.; Grag, U. Preprocessing and Segmentation of MRI Images for Bone Cancer Detection Using Aurous Spatial Pooling With Deeplabv3.; Grenze Scientific Society, 2024; Vol. 2, pp. 2374–2383.

- Ouyang, T.; Yang, S.; Gou, F.; Dai, Z.; Wu, J. Rethinking U-Net from an Attention Perspective with Transformers for Osteosarcoma MRI Image Segmentation. Comput Intell Neurosci 2022, 2022, 7973404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Y.; Qin, F.; Wang, C. RTUNet++: Assessment of Osteosarcoma MRI Image Segmentation Leveraging Hybrid CNN-Transformer Approach with Dense Skip Connection.; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023; pp. 217–223.

- Baidya Kayal, E.; Kandasamy, D.; Sharma, R.; Bakhshi, S.; Mehndiratta, A. Segmentation of Osteosarcoma Tumor Using Diffusion Weighted MRI: A Comparative Study Using Nine Segmentation Algorithms. Signal Image Video Process 2020, 14, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Xie, P.; Dai, Z.; Wu, J. Self-Supervised Tumor Segmentation and Prognosis Prediction in Osteosarcoma Using Multiparametric MRI and Clinical Characteristics. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilengir, A.H.; Evrimler, S.; Serel, T.A.; Uluc, E.; Tosun, O. The Diagnostic Value of Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Based Texture Analysis in Differentiating Enchondroma and Chondrosarcoma. Skelet. Radiol 2023, 52, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Liu, T.; Sun, C.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Hong, N. The Potential for Different Computed Tomography-Based Machine Learning Networks to Automatically Segment and Differentiate Pelvic and Sacral Osteosarcoma from Ewing’s Sarcoma. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2023, 13, 3174–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consalvo, S.; Hinterwimmer, F.; Neumann, J.; Steinborn, M.; Salzmann, M.; Seidl, F.; Lenze, U.; Knebel, C.; Rueckert, D.; Burgkart, R.H.H. Two-Phase Deep Learning Algorithm for Detection and Differentiation of Ewing Sarcoma and Acute Osteomyelitis in Paediatric Radiographs. Anticancer Res 2022, 42, 4371–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, H.B.; Mishra, R.; Daescu, O.; Cederberg, K.; Rakheja, D.; Sengupta, A.; Leonard, D.; Hallac, R.; Leavey, P. Viable and Necrotic Tumor Assessment from Whole Slide Images of Osteosarcoma Using Machine-Learning and Deep-Learning Models. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0210706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prexler, C.; Kesper, M.S.; Mustafa, M.; Seemann, W.; Schmidt, O.; Gall, K.; Specht, K.; Rechl, H.; Knebel, C.; Woertler, K.; et al. Radiogenomics in Ewing Sarcoma: Integration of Functional Imaging and Transcriptomics Characterizes Tumor Glucose Uptake. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, S694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Butola, A.; Kumar, A.; Thapa, P.; Joshi, A.; Jadhav, S.; Singh, N.; Prasad, D.K.; Agarwal, K.; Mehta, D.S. Single-Shot Multispectral Quantitative Phase Imaging of Biological Samples Using Deep Learning. Appl Opt 2023, 62, 3989–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, R.A.; Frisoni, T.; Kurunskal, V.; Donati, D.M.; Jeys, L. Computer Navigation and 3d Printing in the Surgical Management of Bone Sarcoma. Cells 2021, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).