1. Introduction

Climate change is one of the most critical challenges of the last century that implicates ecosystems, economies, and societies. Urban areas, are particularly prone to experience its effects due to their high population density, built-up infrastructure and over-usage of personal vehicles [

1]. Cities are often lacking in resilience measures to combat these impacts, placing their citizens at a high risk. Rural areas have lower temperatures as a result of more green areas and a reduced percentage of impervious surfaces and anthropogenic heat sources [

2]. UHIs directly impact energy consumption, biodiversity degradation, rising health risks and heat related deaths [

1]. Consequently, the topic of UHI has gathered the attention of scholars and policy makers, and it is treated as one of the main environmental threats in many cities worldwide [

3].

In 2024, infants and people aged 65 and over were exposed, on average, to 304% and 389% more heatwave days per person, respectively, compared to the 1986–2005 period [

4]. Heat exposure also heightens the risk of adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes, while aggravating existing neurological conditions [

5].

Given these escalating climatic and demographic pressures, understanding how urban environments exacerbate or mitigate heat-related risks has become a scientific and societal priority. This study aims to synthesise recent literature on the relationships between urban heat, health, and mitigation strategies, particularly the role of Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) and spatial analysis methods. By reviewing key research themes and identifying existing gaps, this work contributes to advancing climate-resilient and health-conscious approaches to urban planning.

2. Materials and Methods

This literature review was designed to systematically examine recent research on Urban Heat Islands (UHI), health impacts, vulnerable populations, and Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) for climate resilience. The review follows a structured and replicable approach to ensure the reliability, transparency, and focus of the selection and analysis process. It aims to synthesise the existing knowledge base and identify knowledge gaps in the intersection of UHI mitigation, public health, and spatial analysis.

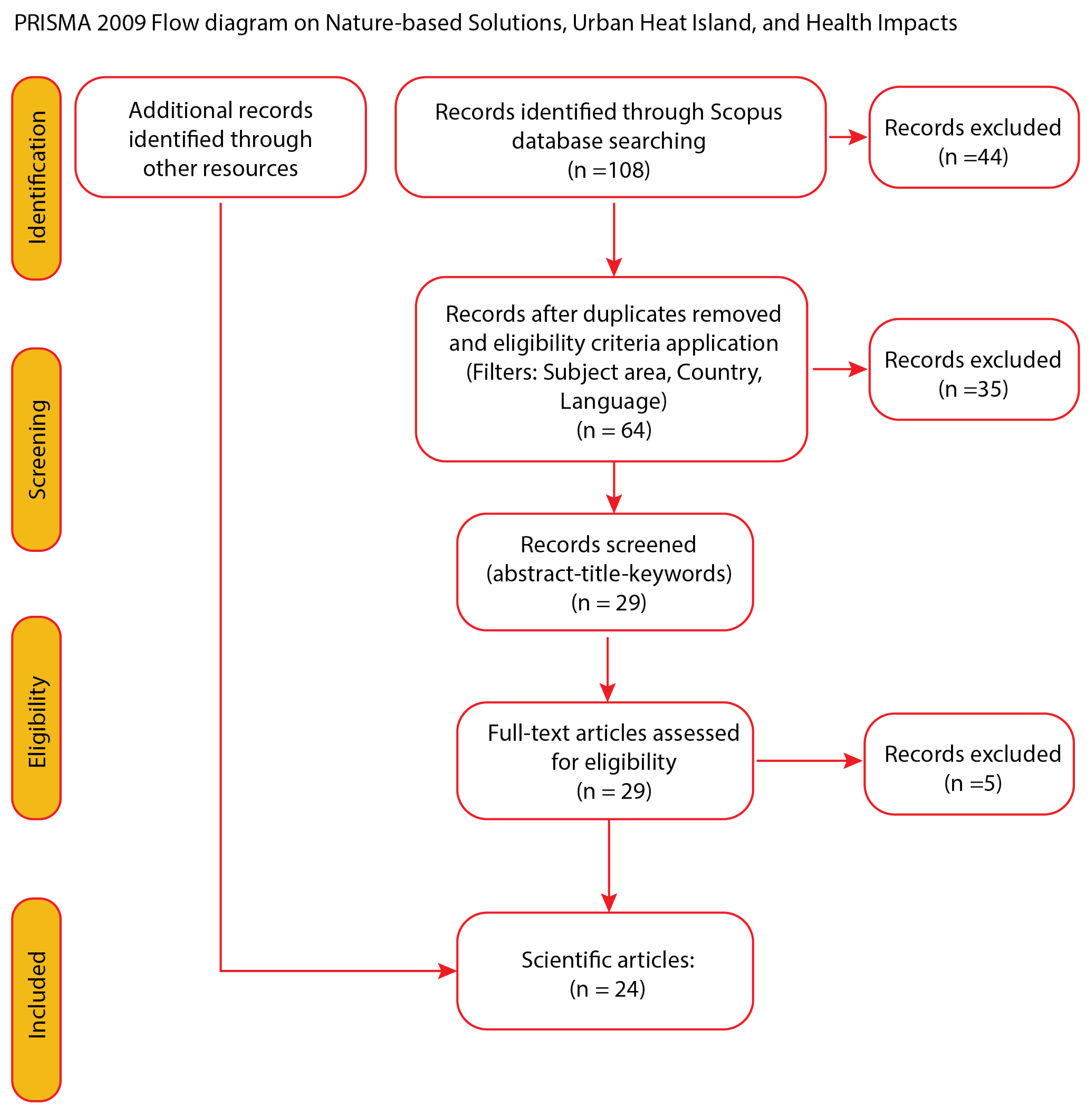

The literature search was carried out using the Scopus database, selected for its comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed scientific publications across disciplines. The first search string was built with the following keywords: (“Urban Heat Island” OR UHI) AND health AND impact AND (“nature-based solution*” OR NBS OR cooling). The reason for using these specific terms was to ensure that the retrieved literature directly touches on the connection between strategies aimed at analysing, mapping and tackling urban heat island effects, and their implication for population health. As shown in the PRISMA Diagram (

Figure 1), this initial string led to 108 papers, pondering on different study backgrounds covering various aspects of the searched topics. To refine this list and increase the relevance of the result, a series of filtering criteria were applied systematically. The inclusion criteria required studies to be: (i) peer-reviewed journal articles; (ii) focused on European urban contexts; and (iii) directly related to heat, Urban Heat Island (UHI) dynamics, Nature-Based Solutions, health outcomes, or spatial/remote-sensing assessments.

Exclusion criteria comprised: conference abstracts, non-peer-reviewed reports, studies limited exclusively to indoor environments, single-building thermal simulations unless explicitly linked to neighbourhood-scale heat exposure, and papers focused solely on plant physiology without an urban or climatic component.

Both original research articles and review papers (e.g., scientometric, systematic, or thematic reviews) were considered, provided they met the relevance criteria and contributed to understanding UHI, NBS, vulnerability, or health in European cities.

Applying these filters, resulted in the subtraction of 44 papers, therefore having a shorter list of 64 papers. These were subjected to a screening where the abstracts were read, out of which another 34 papers were excluded, bringing the number of currently relevant papers to 29. After reading the contents, 5 more papers were excluded, the number of relevant research papers dropping to 24. The exclusion criteria for the last papers eliminated were country of research being Sri Lanka (information not being disclosed in the title nor abstract), research focused on indoor spaces, paper referring only to UHI island effect on plant health, case study on a single building in Spain, research centred on modelling the cooling efficiency of single trees.

3. Results

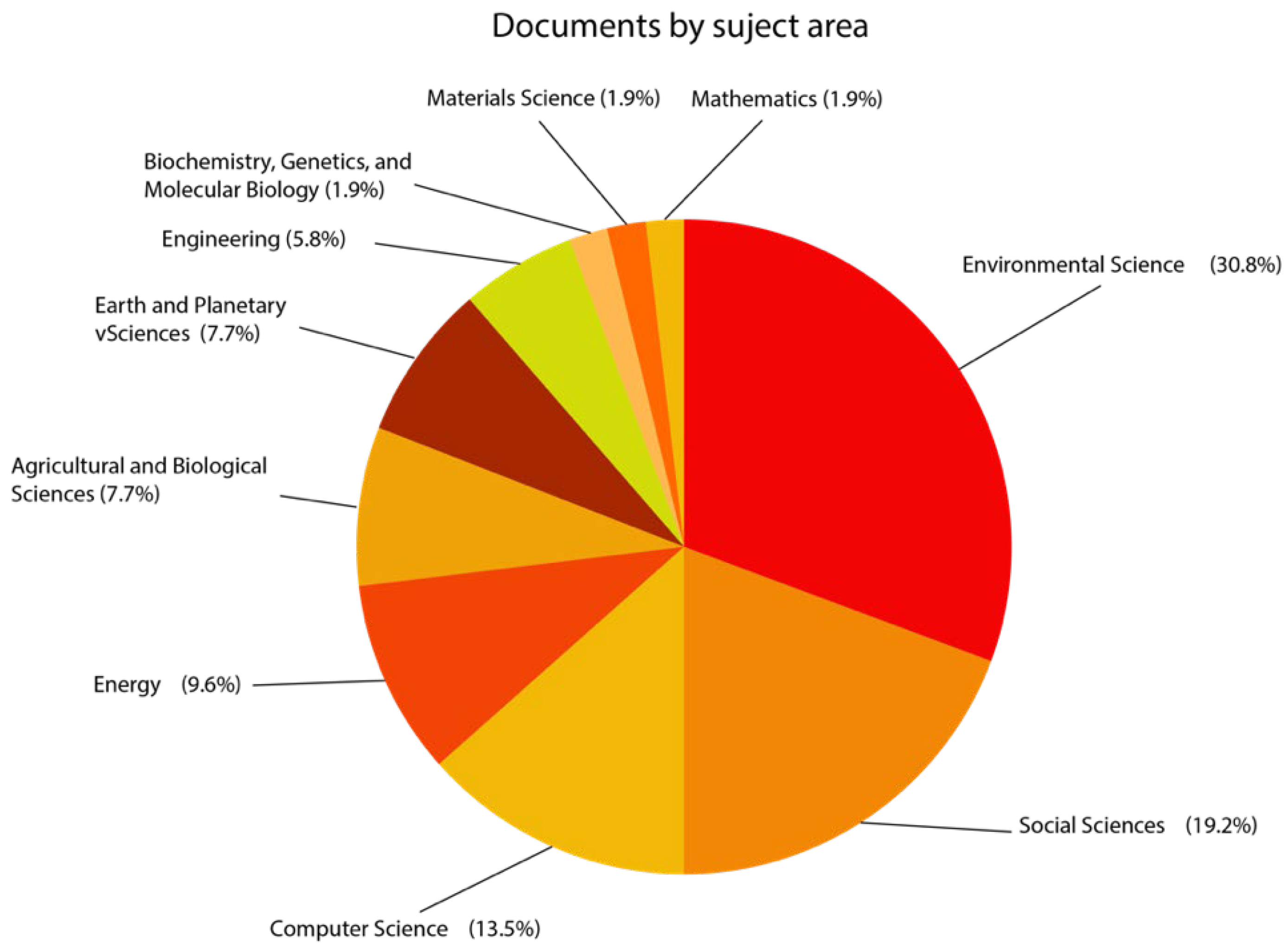

The papers are categorised in subject areas they relate to as noted in the Scopus database (

Figure 2) and it reflects the multidisciplinary nature of UHI research. This classification shows how different disciplines approach the analysis of heat exposure, mitigation strategies and social vulnerabilities. The subject area with the most papers found to be relevant is Environmental Science (16 papers). This highlights the predominance of research intended for climate adaptation, land surface temperature analysis and the role of Nature-based solutions as a mitigation strategy. Additionally, it confirms that UHI is fundamentally an environmental phenomenon, influenced by atmospheric conditions, land cover and urban morphology. The subsequent theme is Social Sciences with 10 documents, predominantly with the topic of public health in the context of UHI, underlining the fact that this phenomenon is not only a climatic issue but also a socio-economic one. Afterwards, Computer Science comprises of 7 papers on a variety of topics out of which only two refer directly to GIS mapping and remote sensing, another two are literature reviews and the other ones are case studies, however the majority are in fact using GIS technologies or analysing them. Several papers are within Energy (5 papers) and Engineering (3 papers) suggesting the focus on urban infrastructure, energy efficient cooling strategies and building materials. The existence of studies within Agricultural and Biological Sciences (4 papers) and Earth and Planetary Sciences (4 papers) implies a connection between urban climate dynamics and ecological processes, like evapotranspiration, land use changes, and biodiversity. The Biochemistry, Genetics, and Molecular Biology (1 paper) and Materials Science (1 paper) categories show reduced representation of biomedical and material innovation research in UHI studies. Even though UHI has clear public health implications, the absence of extensive health-related literature in this review implies a potential research gap in integrating the assessment of UHI vulnerability and health risk analysis.

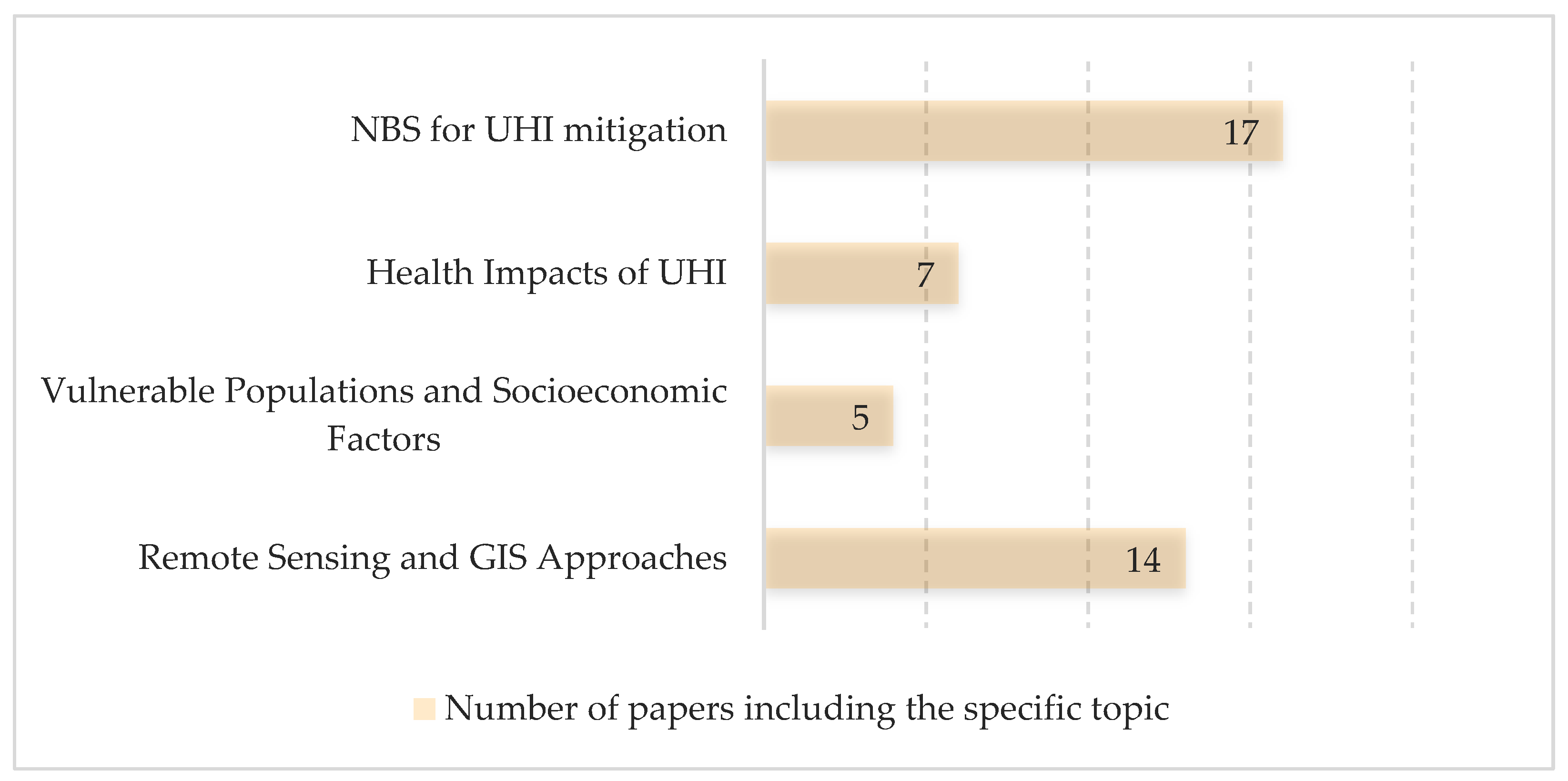

To systematically analyse the existing body of research relevant to this research, a structured approach was taken to categorize the selected studies into key thematic areas. Given the interdisciplinarity of Nature-Based Solutions (NBS), Urban Heat Islands (UHI), and health impacts, the literature was grouped into topics that reflect both the scientific foundations and the practical applications of urban climate adaptation.

The categorization process was guided by understanding the effectiveness of NBS in mitigating UHI, assessing the associated health benefits, evaluating spatial patterns through remote sensing, and exploring the socio-economic and policy dimensions of climate adaptation in urban environments. Each paper was analysed for its primary research focus, methods, and findings, allowing for a logical grouping into four main categories shown in

Table 1 as follows:

Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) for UHI Mitigation

Research in this category focuses on green infrastructure interventions such as green roofs, urban trees, and sustainable urban drainage systems as strategies for cooling urban areas. These studies are critical in assessing how NBS contribute to lowering temperatures, improving air quality, and enhancing urban resilience.

Health Impacts of UHI

This theme highlights the public health risks associated with urban heat islands, particularly for vulnerable populations. The selected papers examine heat stress, morbidity, and mortality rates, as well as the role of green infrastructure in reducing thermal discomfort and associated health risks.

Remote Sensing and GIS Approaches

Given the importance of spatial analysis in climate adaptation, this category includes studies that use satellite imagery, thermal mapping, and GIS-based models to assess the extent of UHI, vegetation coverage, and urban cooling patterns.

Vulnerable Populations and Socioeconomic Factors

Research in this area examines how UHI disproportionately affects low-income communities, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups. These studies highlight environmental justice concerns and provide evidence for targeting interventions in areas with higher social and climatic risks.

As

Figure 3 shows, the Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) for UHI Mitigation topic has the most papers, with 17 investigations exploring the impact of green and blue infrastructure on urban heat mitigation. The Health Impacts of UHI collection comprises 7 studies that examine the impact of urban heat on public health and potential strategies to improve thermal comfort. Five studies in the Vulnerable Populations and Socioeconomic Factors series examine how different social groups are impacted by the rising heat and the resulting inequities. Fourteen papers cover remote sensing and GIS approaches, emphasising the significance of spatial analysis and satellite data in understanding UHI and climate resilience.

3.1. Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) for UHI Mitigation

As the world grapples with the challenges of urban heat islands, nature-based solutions have emerged as a promising way to address this issue. Urban heat islands refer to the phenomenon where urban areas experience high temperatures compared to their surrounding rural counterparts, largely due to the prevalence of impervious surfaces, anthropogenic activities, and the lack of vegetation [

30]. The research in this category primarily explores green roofs, urban green spaces, and blue-green infrastructure as effective cooling interventions. The reviewed studies examine the implementation of NBS across distinct urban contexts and are assessing their cooling benefits, integration with the city’s heritage and their effectiveness in improving the microclimate [

12,

22].

While the primary objective of these papers is evaluating the effectiveness of NBS in mitigating UHI, their approach is different. In the broader study of Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) for Urban Heat Island (UHI) reduction, 17 papers were selected as relevant to the topic. However, while many look at the effects of green infrastructure on UHI, only a handful specifically addresses Nature-Based Solutions as a concept. To guarantee a methodical and focused discussion,

Table 2 contains only four significant publications that explicitly address NBS as an urban planning and climate adaptation strategy.

These publications [

7,

22,

27,

30], explicitly discuss Nature-Based Solutions and assess their effectiveness in mitigating UHI using GIS, remote sensing, or climate modelling methodologies. Furthermore, they evaluate NBS's multifunctionality, considering not just thermal comfort but also social resilience, psychological well-being, and vulnerable populations' access to cooling infrastructure. Their findings have a direct impact on the issue of how NBS may be implemented in cities as a climate adaptation strategy, making them especially relevant to this review.

While the other 13 papers in the Nature-Based Solutions category mention the cooling impacts of urban greenery and blue infrastructure, they do not clearly relate their findings explicitly to NBS. Instead, they concentrate on the biophysical effects of green spaces, urban parks, tree canopies, and blue spaces in lowering urban temperatures. Although they give important evidence on the association between vegetation and UHI reduction, they do not focus on Nature-Based Solutions as a strategy framework for urban resilience. [

12] is the only one referring to the implementation of NBS into the built heritage for the enhancement of urban sustainability without interfering with the historic urban landscapes. The other two papers are taking a case study methodology approach to assess real world implementation of NBS, predominantly in Mediterranean and temperate climates where UHI have the worst impact [

22,

24]. [

22] is using GIS-based thermal assessments and [

21] is using microclimate modelling and site-specific temperature measurements.

The reviewed literature consistently indicates the significant impact of NBS in reducing urban temperatures, with their cooling effects varying based on location, vegetation density and climate conditions [

19,

22,

24]. The studies focused on green roofs demonstrate the effective heat reduction in urban areas, lowering surface temperatures by several degrees [

19,

22]. Other papers concentrated on tree canopies and green infrastructure implementation, have showed the importance of the strategic placement of green infrastructure in improving shading and foster evapotranspiration which helps in mitigating UHI effects [

24,

30]. The study focused on heritage conservation, suggest that green roofs and vertical greenery can be integrated into existing structures without compromising architectural integrity [

12]. To maximise outdoor thermal comfort, a study in Madrid showed the importance of integrating water features, vegetation and shading structures [

22]. Additionally, research on psychological well-being indicates that beyond temperature regulation, NBS contributes to stress reduction and enhanced urban liveability, making it a multi-functional climate adaptation tool [

30].

3.2. Health Impacts of UHI

The influence of urban heat islands on human health has become an important topic in recent years. Several research have investigated the numerous aspects that can influence inhabitants' sensitivity to heat exposure in urban contexts. In Europe, heat vulnerability increased by 9% between 1990 and 2022 (from 37.9% to 41.2%), as rising exposure to high temperatures disproportionately affected older adults, individuals with chronic conditions, urban residents, outdoor workers (often migrants), socially deprived groups, pregnant women, and newborns [

5].

Table 3.

Health Impacts of UHI

Table 3.

Health Impacts of UHI

| Author/s |

Methodology |

Outcomes |

[8] - Arellano and Roca, 2022

|

Remote sensing study using Landsat 8 and Sentinel 2 to analyse urban greenery and its impact on nighttime UHI in Barcelona. |

Found that urban vegetation significantly reduces nighttime temperatures, mitigating heatwaves and improving public health by decreasing respiratory and cardiovascular risks during extreme heat events. |

| [9] - Aznarez, C. et al. (2024) |

Analysed inequalities in urban heat vulnerability by assessing mismatches in ecosystem services using GIS and environmental datasets. |

Low-income and marginalized communities have reduced access to cooling ecosystem services, making them more vulnerable to heat-related health issues. |

| [10] - Buchin, O. et al. (2016) |

Modelled and evaluated health-risk reduction potential of UHI countermeasures. |

Increasing green infrastructure and reflective surfaces significantly reduce heat stress and related health risks in urban areas. |

| [11] - Capari, L. et al. (2022) |

Scientometric study analysing urban green/blue infrastructure and climate-induced public health effects. |

Strong correlation between green & blue infrastructure and reduced heat-related illnesses and mortality. |

| [15] - Hoeven, F. van der and Wandl, A. (2015) |

Mapped land use, UHI, and health implications using GIS and spatial analysis in Amsterdam. |

Higher urban temperatures impact maternal and infant health by leading to lower birth weights in newborns. Birth weight is a critical health indicator, and exposure to excessive heat during pregnancy can have long-term developmental consequences for infants. |

| [21] - Mosca, F. et al. (2021) |

Explored the impact of urban heat islands (UHIs) on health, focusing on both thermal comfort and psychological well-being in Genoa, Italy. |

Highlighted that UHIs contribute to heat-related health issues, including heat stress and exacerbation of pre-existing conditions. |

| [27] - Vasconcelos, L. et al. (2024) |

Investigated urban green spaces as cooling solutions for older adults. |

Elderly populations benefit significantly from green spaces, reinforcing the role of nature-based climate shelters. |

Strong empirical evidence linking heatwaves to an increase in cardiovascular and respiratory emergency calls in Milan [

31] finding hotspots of health vulnerability by mapping Urban Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) values with geolocated emergency calls, showing that regions with higher UTCI values also had higher emergency call rates. Their findings show that socioeconomic and spatial disparities heighten heat-related health risks, particularly among older and low-income groups. Similarly, [

9] considered factors that could either amplify or mitigate the impact of heat exposure, like residents' ages and health status, including the percentage of the population aged 14 or younger and 65 or older, as well as the prevalence of respiratory diseases, diabetes, and pulmonary conditions in both male and female populations.

Additionally, [

10] highlighted the importance of analysing heat-related mortality in relation to indoor conditions, as vulnerable populations are primarily exposed indoors, where delayed risk increases during heat events result from the thermal inertia of buildings. A noteworthy study [

21] that focuses on the connection between public health decline and poor quality of the environment, especially how the elderly are disproportionally affected by heat, highlights the fact that poor air quality and high surface temperature exacerbates chronic illnesses.

Not many studies are focusing on the psychological wellbeing of the population relating to UHI, however the ones that mention it, are considering the benefits of green infrastructure on mental health. For example, [

12], while not part of this thematic category, explores the integration of heritage and green spaces and its positive effects on visitors’ mental health.

In a scientometric review, [

11], analysing the evolution of research on UHI and health impacts, they found that even though climate science has extensively studied UHI, the direct effects on public health are underexplored when comparing to other climate-related hazards. Their review highlights the need for multidisciplinary approaches, incorporating urban planning, climate adaptation approaches and health sciences to develop effective mitigation strategies.

The reviewed studies provide strong evidence the effects of UHI on health, worsening cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, indoor thermal comfort, chronic sicknesses, and psychological well-being. The findings emphasize the significance of combining climate adaptation measures, such as urban greening, improved building designs, and targeted interventions for high-risk groups into public health and urban policies.

4. Vulnerable Population and Socioeconomic Factors

The Urban Heat Island (UHI) intensity does not have an equal effect on everyone. Research shows that social and economic disparities influence the extent to which different demographics are exposed to heat risks [

31]. Vulnerable communities like the elderly, people with pre-existing health conditions or low income, and those with limited access to cooling amenities, are disproportionately affected by extreme heat events and long-term exposure to high urban temperatures [

26].

Table 4.

Vulnerable Population and Socioeconomic Factors

Table 4.

Vulnerable Population and Socioeconomic Factors

| Author/s |

Methodology |

Outcomes |

Suggested Solutions |

| [9] - Aznarez, C. et al. (2024) |

Used GIS and environmental datasets to analyse inequalities in urban heat vulnerability. |

Found that low-income and marginalized communities have reduced access to cooling ecosystem services, making them more vulnerable to heat-related health issues. |

Suggested that better urban planning and green infrastructure are needed to reduce UHI-related health disparities. |

| [11] - Capari, L. et al. (2022) |

Conducted a scientometric study analysing urban green/blue infrastructure and climate-induced public health effects, including impacts on vulnerable populations. |

Identified a strong correlation between green/blue infrastructure and reduced heat-related illnesses and mortality, particularly in vulnerable groups. |

Recommended increasing urban greenery to reduce health inequalities in cities. |

| [15] - Hoeven, F. van der and Wandl, A. (2015) |

Mapped land use, UHI, and health implications using GIS and spatial analysis in Amsterdam. |

Found that elderly and low-income populations are disproportionately affected by UHI. Also highlighted that mothers exposed to higher temperatures give birth to children with lower body weights, a key health risk for infants. |

Emphasised the need for targeted cooling strategies. |

| [26] - Sánchez, C.S.-G., Peiró, M.N. and González, Fco.J.N. (2017) |

Examined the relationship between UHI and vulnerable populations in Madrid, using socioeconomic and climate data. |

Determined that elderly and low-income communities are more susceptible to heat-related illnesses due to limited access to cooling infrastructure and urban greenery. |

Stressed the importance of targeted interventions. |

| [27] - Vasconcelos, L. et al. (2024) |

Investigated the role of urban green spaces as cooling solutions for older adults, particularly in warming cities. |

Found that elderly populations benefit significantly from urban green spaces, reinforcing the role of nature-based climate shelters in reducing heat-related health risks. |

Recommended policies to improve green space accessibility for vulnerable groups. |

This literature review topic critically evaluates key studies that address the connection between UHI, vulnerable populations, and socioeconomic factors, focusing on [

9,

11,

15,

26,

27]. These studies provide insight into the spatial distribution of heat-related risks, the more affected demographic groups, and policies for reducing the inequal effects of UHI.

In an Amsterdam study, [

15], focused on the health of the low-income areas and the energy efficiency of their buildings, emphasising the importance of applying regulations of building efficiency even in areas of higher poverty. While older adults face higher physiological risks, [

26] similarly expands the conversation by recognising other high-risk groups, such as low-income people, individuals living alone, those of lower education, and residents of high-rise dense areas. These groups are usually socially secluded and have reduced access to cooling infrastructure, therefore less able to react efficiently to extreme heat events. [

26] underlines that living in poor housing conditions or being financially unable to afford cooling systems worsen other health issues from heat stress or heat related mortality, highlighting the importance for targeted policies that support vulnerable residents during these events.

Green infrastructure is proved to be a key adaptation strategy for reducing UHI intensity but access to its cooling benefits is also unequal among urban population. [

27] discovered that older adults keenly use parks for coping with heat, preferring abundant shade, leafy vegetation, and availability of close amenities like seating, water fountains or restrooms. Their findings show that urban green infrastructure should be planned considering the vulnerable populations, ensuring not only the presence of green spaces but also their accessibility, safety and functionality. Furthermore, [

9] stresses the lack of sufficient tree canopy and park access in low-income neighbourhoods, leaving them exposed to higher surface temperature. Additionally, a scientometric review, [

11], is underlining the socioeconomic risk within the study of the UHI still needs more exploration.

The reviewed studies within the theme of vulnerable population and socioeconomic factors, provide evidence of the disproportionate effects of UHI on the disadvantaged populations, worsening health issues and increasing mortality rates. Therefore, age, social isolation, income, housing and access to green areas are critical factors that can determine the most at-risk groups.

5. Remote sensing and GIS approaches

The Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect is a well-known phenomenon, but its spatial distribution, intensity, and impact on urban populations necessitates advanced methodologies for accurate assessment. Geographic Information System (GIS) and remote sensing methods are now, essential tools in studying urban heat intricacies, helping researchers to map temperature differences, identify high-risk zones, and evaluate the success of mitigation tactics.

This literature review concentrates on studies that use remote sensing data such as Landsat, Sentinel, or MODIS, and GIS spatial analysis to explore UHI intensity, land surface temperature (LST), and the role of urban vegetation for mitigation. The selected papers engage in various analytical approaches, including thermal imaging, spatial modelling, urban morphology analysis, or land cover classification, offering understandings for the influence of urban form, land use, and vegetation patterns on UHI distribution.

Table 5.

Remote sensing and GIS approaches

Table 5.

Remote sensing and GIS approaches

| Author/s |

Methodology |

Outcomes |

| [6] - Alexander, C. (2021) |

LiDAR data, NDVI analysis, daytime LST |

Vegetation cover and height significantly influence land surface temperature (LST). Increasing tree height reduces LST by up to 5.75°C, highlighting the cooling effect of vegetation in urban areas. |

| [7] - Ampatzidis, P. and Kershaw, T. (2020) |

Urban microclimate analysis, atmospheric conditions, remote sensing |

Highlights that blue spaces can contribute to cooling effects, particularly when combined with green infrastructure. |

[8] - Arellano and Roca, 2022

|

Used Landsat 8 and Sentinel 2, GIS-based mapping of land surface temperature (LST). Assessed the cooling effect of green spaces using spatial analysis. |

Nighttime UHI intensifies heat stress, especially in dense urban areas. Large parks reduce temperatures by 1–4°C (day) and 2–5°C (night). |

| [9] - Aznarez, C. et al. (2024) |

Analyses the supply and demand of temperature regulating ecosystem service (TR-ES) with remote sensing, health, and socio-demographic data with Artificial Intelligence for Environment and Sustainability (ARIES) and GIS. |

Show disparities in heat vulnerability, with increased exposure observed among socio-economically disadvantaged communities, the elderly, and people with health issues. |

| [13] - Eldesoky, A.H.M., Colaninno, N. and Morello, E. (2020) |

GIS-based ventilation corridor mapping, spatial analysi. |

Urban ventilation corridors play a significant role in nighttime cooling, as green corridors release stored heat more rapidly than built-up areas, providing localized cooling benefits. |

| [14] - Ge, X. et al. (2020) |

Landsat 8 imagery to analyse land cover changes and LST variations in Geneva and Paris. |

Green spaces help lower LST by providing shading and evapotranspiration effects. Impervious surfaces lead to higher LST, reinforcing the need for distributed greenery in urban areas. |

| [15] - Hoeven, F. van der and Wandl, A. (2015) |

Use NASA LANDSAT 5, Diurnal LST and nocturnal air temperature UHI mapping to analyze land use, health, and energy efficiency in Amsterdam. |

Mapped UHI variations in air temperature using Landsat 5 data and highlighted the stronger nocturnal UHI effect due to heat retention in built environments. |

| [16] - Isola, F., Leone, F. and Pittau, R. (2024) |

Systematic review of remote sensing and GIS methodologies for analysing UHI and ecosystem services. |

Identifies the most effective remote sensing approaches for studying urban climate and mitigation strategies. Landsat imagery being one of the most efficient. |

| [17] - Lauwaet, D. et al. (2024) |

UHI modeling across 100 European cities using UrbClim model, Air temperature UHI, NDVI from Copernicus Land service |

Demonstrates varying UHI intensities across different urban morphologies and provides a large-scale comparative analysis. |

| [18] - Marando, F. et al. (2019) |

Analyse UHI features in a spatially explicit way and on a seasonal basis, through the Land Surface Temperature (LST) derived from Landsat-8. |

Finally, the multiple-linear regression model have showed that firstly the NDVI, and then the surface covered by trees, that provision of the ES of climate regulation by GI. NBS have the highest potential to provide this ES in a Mediterranean city. |

| [22] - Olivieri, F., Sassenou, L.-N. and Olivieri, L. (2024) |

ENVI-met microclimate simulation. |

Finds that green infrastructure can significantly lower temperatures, with effectiveness dependent on urban context and climate. |

| [26] - Sánchez, C.S.-G., Peiró, |

GIS based mapping vulnerable population. |

Existence of several neighbourhoods in Madrid with an important presence of vulnerable population that are in some of the hottest areas of the city, |

| [29] - Vulova, S. et al. (2023) |

Evapotranspiration mapping, Sentinel-2, other remote sensing methods. |

Shows that evapotranspiration plays a key role in mitigating UHI, reinforcing the importance of urban vegetation. |

Limitations and accuracy in UHI analysis with remote sensing

The reliability of LST measurements is one of the concerns while performing satellite-based measurements, especially on an urban setting. [

7] notes that remote sensing can overestimate daytime temperature and underestimate the nighttime ones, mostly because of the way thermal sensors perceive surface-level temperature. Compared to actual air temperatures, the surfaces that have low thermal inertia captured by the sensors, fluctuate more in temperature. Therefore, this can lead to misinterpretation of UHI intensity, especially when comparing it to ground based air temperature measurements.

Moreover, [

29] highlights the 16-day revisit cycle of the Landsat satellites which also limits their capacity to capture specific extreme heat events. They discuss the fact that heat waves are usually events that last a few days which may not be within the revisit time, therefore failing to measure the LST during peak heat. Their paper suggests integrating higher-temporal-resolution data sources like Sentinel-2 (evapotranspiration models) to increase the precision of urban cooling effect assessments.

Despite these limitations, [

23] performed a systematic review of Landsat-based UHI research, discovering that Landsat 8 remains one of the most widely used data sources for urban thermal studies. Additionally, they also found irregularities in study methodologies, with many failing to specify whether their LST data was captured during daytime or nighttime, restricting comparability between studies.

The influence of green infrastructure in UHI mitigation: findings from remote sensing

Several studies showed that vegetation has an important role in cooling urban areas, quantifying these effects through Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Evapotranspiration (ET) mapping. Using Landsat 8 daytime LST analysis, [

14] noticed that surface temperature areas are reduced by vegetated areas through evaporative cooling and shading. Important to note are the findings of [

6] about the strong predictors of urban temperature variations being vegetation height and volume, and NDVI. Moreover, they suggested that tree canopy cover had a stronger cooling effect in comparison to vegetation height alone, recommending that greater green spatial coverage is more effective than tree size in UHI mitigation. This is especially significant for urban planning, as it shows the need for extensive rather than small, scattered green areas.

Microclimate modelling and urban ventilation analysis

Some studies have explored the influence of urban morphology on temperature distribution, adding another dimension to the study of UHI. [

22] used ENVI-met microclimate modelling to assess the interaction between buildings, vegetation, the atmosphere and other surfaces. Their findings confirm the significance of green infrastructure on outdoor thermal comfort, especially when added into dense urban areas that retain more heat.

Furthermore, the effect of cooling is not uniform throughout the whole day. Through studying urban ventilation corridors, [

13] found that green corridors perform more effective cooling during the night than the day. This is due to the low capacity of storing heat by the vegetated areas and their fast heat release at night, while impervious surfaces retain heat for longer. This paper advises that ventilation corridors should be considered by planners in cities where the nighttime UHI is high.

Combining NDVI with UrbClim model, [

17] analysed the variations of air temperature UHI intensity between seasons. Their outcomes show yet again the important role of green cover on seasonal cooling tendencies, adding that it is important to have year-round vegetation coverage instead of only concentrating on summer cooling benefits.

To conclude, the reviewed studies within the remote sensing and GIS approaches in UHI analysis illustrate both the strengths and limitations. Even though Landsat 8 daytime analysis is one of the widest methods used, it sometimes needs complementary methods like climate modelling, evapotranspiration and urban ventilation mapping. Therefore, combining multiple approaches, researchers can have a better understanding of climate dynamics, improving UHI mitigation strategies.

6. Discussion

The reviewed literature demonstrates the growing relevance of nature-based solutions (NBS) as an adaptive response to urban heat and health risks in European cities. Across studies, several recurrent patterns emerge: the measurable cooling potential of urban green and blue infrastructure; the uneven distribution of thermal exposure and adaptive capacity across social groups; and the increasing reliance on geospatial and remote-sensing methods to assess exposure, vulnerability, and the effectiveness of interventions. These topics collectively highlight that the mitigation of urban heat is both an environmental and a social challenge.

Nature-based solutions emerge across the reviewed studies as a key strategy to mitigate UHI intensity and improve thermal comfort. Vegetation, green roofs, urban parks, and water bodies contribute to local temperature reduction through shading and evapotranspiration, while also supporting air quality and psychological wellbeing. However, despite extensive evidence of their cooling potential, few studies frame these interventions explicitly within a governance or policy context, and even fewer assess their long-term health impacts. The literature therefore suggests that integrating NBS into planning and health adaptation frameworks remains a major challenge.

Spatial and remote-sensing analyses have become essential tools to quantify thermal patterns and evaluate exposure. Most studies rely on Land Surface Temperature (LST) derived from Landsat imagery, often combined with indices such as NDVI to relate vegetation coverage to cooling effects. Yet, methodological inconsistencies persist, particularly regarding temporal resolution, surface–air temperature differences, and validation with in-situ data. While these approaches allow comparison across urban districts and time periods, higher-resolution data and standardised reporting of data would enhance the comparability and transferability of results.

Overall, the literature demonstrates a growing interest toward integrating environmental data, socio-demographic factors, and spatial vulnerability mapping to identify priority areas for intervention. Nevertheless, the limited evaluation of implemented NBS, the underrepresentation of indoor thermal risk, and the lack of harmonised indicators remain important gaps. Future research would benefit from stronger interdisciplinary collaboration between public health, climate research, and urban planning to support evidence-based adaptation and equitable heat-mitigation strategies in European cities.

7. Conclusions

The synthesis of existing literature highlights the environmental and social dimensions of urban heat adaptation. Nature-based solutions consistently demonstrate potential for surface-temperature reduction and microclimatic regulation, yet their distribution and accessibility remain socially inequitable. Integrating remote-sensing with demographic and health data provides a way for identifying priority areas and designing equitable interventions. However, methodological standardisation, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and evaluation of health impacts remain underdeveloped.

Future research would benefit from longitudinal assessments of implemented NBS (measurements of thermal/health outcomes at multiple time points after implementation), explicit integration of indoor exposure metrics, and evaluation frameworks that connect biophysical indicators with measurable health outcomes. In addition, it should also prioritise the co-production of indicators with local authorities and public health agencies to ensure that heat-risk metrics are actionable and context-specific. Furthermore, the increasing availability of higher-resolution and near-real-time datasets, including Sentinel imagery and urban climate model outputs, offers significant potential to enhance heatwave monitoring and support evidence-based urban heat action plans.

Advancing these dimensions will strengthen the evidence base required to embed NBS within climate-health policy and spatial planning, contributing to more resilient and equitable European urban environments.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UHI |

Urban Heat Island |

| LST |

Land Surface Temperature |

| GIS |

Geographic Information Systems |

| NBS |

Nature-Based Solutions |

| MODIS |

Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| NDVI |

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| ET |

Evapotranspiration |

| UTCI |

Universal Thermal Climate Index |

| UrbClim |

Urban climate model |

| TR-ES |

Temperature-Regulating Ecosystem Services |

| LiDAR |

Light Detection and Ranging |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

References

- Kalantari, Z.; Ferreira, C. S. S.; Pan, H.; Pereira, e P. Nature-based solutions to global environmental challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, vol. 880, 163227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, F. , «Using green to cool the grey: Modelling the cooling effect of green spaces with a high spatial resolution. Sci. Total Environ. vol. 724, 138182, lug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Panno; Carrus, G.; Lafortezza, R.; Mariani, L.; Sanesi, G. Nature-based solutions to promote human resilience and wellbeing in cities during increasingly hot summers. Environ. Res. 2017, vol. 159, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanello, M. , «The 2024 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: facing record-breaking threats from delayed action. The Lancet 2024, vol. 404(fasc. 10465), 1847–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Daalen, K. R. The 2024 Europe report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: unprecedented warming demands unprecedented action. Lancet Public Health 2024, vol. 9, fasc. 7–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C. Influence of the proportion, height and proximity of vegetation and buildings on urban land surface temperature. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2021, vol. 95, 102265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampatzidis e, P.; Kershaw, T. A review of the impact of blue space on the urban microclimate. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, vol. 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, B.; Roca, J. EFFECTS OF URBAN GREENERY ON HEALTH. A STUDY FROM REMOTE SENSING. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, vol. XLIII-B3-2022, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznarez, C.; Kumar, S.; Marquez-Torres, A.; Pascual, U.; Baró, F. Ecosystem service mismatches evidence inequalities in urban heat vulnerability. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, vol. 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchin, M.-T.; Hoelscher; Meier, F.; Nehls, T.; Ziegler, e F. Evaluation of the health-risk reduction potential of countermeasures to urban heat islands. Energy Build. 2016, vol. 114, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capari, L.; Wilfing, H.; Exner, A.; Höflehner, T.; Haluza, e D. Cooling the City? A Scientometric Study on Urban Green and Blue Infrastructure and Climate Change-Induced Public Health Effects. Sustain. Switz. 2022, vol. 14, fasc. 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes e, M. A.; Viles, H. A. Integrating nature-based solutions and the conservation of urban built heritage: Challenges, opportunities, and prospects. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, vol. 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesoky, H. M.; Colaninno, N.; Morello, e E. Mapping Urban ventilation corridors and assessing their impact upon the cooling effect of greening solutions. In presentato al International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences - ISPRS Archives; 2020; pp. 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Mauree, D.; Castello, R.; Scartezzini, J.-L. Spatio-Temporal Relationship between Land Cover and Land Surface Temperature in Urban Areas: A Case Study in Geneva and Paris. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, vol. 9(fasc. 10), 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Hoeven e, F.; Wandl, A. Amsterwarm: Mapping the landuse, health and energy-efficiency implications of the Amsterdam urban heat island. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2015, vol. 36(fasc. 1), 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola et al. - 2024 - Urban Heat Island Phenomenon and Ecosystem Service.pdf.

- Lauwaet, D. High resolution modelling of the urban heat island of 100 European cities. Urban Clim. 2024, vol. 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marando, F.; Salvatori, E.; Sebastiani, A.; Fusaro, L.; Manes, F. Regulating Ecosystem Services and Green Infrastructure: assessment of Urban Heat Island effect mitigation in the municipality of Rome, Italy. Ecol. Model. 2019, vol. 392, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalakakou, G. Green roofs as a nature-based solution for improving urban sustainability: Progress and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, vol. 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz Monteiro, M.; Doick, K. J.; Handley, P.; Peace, e A. The impact of greenspace size on the extent of local nocturnal air temperature cooling in London. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, vol. 16, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca et al. - 2021 - Nature-Based Solutions Thermal Comfort Improvemen.pdf.

- Olivieri, F.; Sassenou, L.-N.; Olivieri, e L. Potential of Nature-Based Solutions to Diminish Urban Heat Island Effects and Improve Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Summer: Case Study of Matadero Madrid. Sustain. Switz. 2024, vol. 16, fasc. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, F.; Leone, F.; Pittau, e R. Evaluating the urban heat island phenomenon from a spatial planning viewpoint. A systematic review. TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2023, vol. 2023, fasc. Special(Issue 2), 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perini, K.; Calise, C.; Castellari, P.; Roccotiello, e E. Microclimatic and Environmental Improvement in a Mediterranean City through the Regeneration of an Area with Nature-Based Solutions: A Case Study. Sustain. Switz. 2022, vol. 14, fasc. 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rötzer, T.; Rahman, M. A.; Moser-Reischl, A.; Pauleit, S.; Pretzsch, e H. Process based simulation of tree growth and ecosystem services of urban trees under present and future climate conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, vol. 676, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Guevara Sánchez, C.; Núñez Peiró, M.; Neila González, e F. J. Urban heat Island and vulnerable population. The case of Madrid. Sustainable Development and Renovation in Architecture, Urbanism and Engineering 2017, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, L.; Langemeyer, J.; Cole, H. V. S.; Baró, e F. Nature-based climate shelters? Exploring urban green spaces as cooling solutions for older adults in a warming city. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, vol. 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J. Green spaces are not all the same for the provision of air purification and climate regulation services: The case of urban parks. Environ. Res. 2018, vol. 160, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vulova, S. City-wide, high-resolution mapping of evapotranspiration to guide climate-resilient planning. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, vol. 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, F.; Dotti Sani, G. M.; Giachetta, A.; Perini, K. Nature-Based Solutions: Thermal Comfort Improvement and Psychological Wellbeing, a Case Study in Genoa, Italy. Sustainability 2021, vol. 13(fasc. 21), 11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendeli, D. , «From heatwaves to ‘healthwaves’: A spatial study on the impact of urban heat on cardiovascular and respiratory emergency calls in the city of Milan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, vol. 124, 106181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).