1. Introduction

Climate change is one of the most critical challenges of the current century that implicates ecosystems, economies, and societies. Urban areas, due to their density and excessive use of impermeable surfaces, are particularly vulnerable to its effects, especially with the Urban Heat Island (UHI) phenomenon, which intensifies temperatures in cities compared to their rural surroundings [

1,

2]. This rise in urban temperature poses significant risks to public health, particularly for vulnerable age groups that are less able to adapt to extreme heat conditions, such as the elderly and young children [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

In a global context of rising older population, the heat risks impose a growing concern, especially in densely populated cities in temperate climates where heat waves are increasingly frequent [

7]. One out of six world inhabitants will be over 65 years old in 2050 according to United Nations prospects [

9]. According to ISTAT, Italy’s population over 65 years old will increase from 24% to 34.5%. Therefore, the aim for reducing the heat related risks should be a priority for the public health and climate adaptation of cities [

10,

11,

12].

More localized and data-driven approaches to climate adaptation are essential to mitigate these risks [

13,

14]. The integration of remote sensing, demographic data, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) offers a tool to map and understand spatial patterns of heat exposure and vulnerability [

12,

15].

Milan was selected as the case study due to its significant climatic challenges. The city is experiencing intense UHI effects and is among the European cities with the hottest recorded urban areas [

16]. Its geographical position in the Pianura Padana, surrounded by the Alps, limits natural air circulation and facilitates heat retention. Using high-resolution satellite imagery and localised population estimates, the system identifies urban areas where vulnerable populations are at risk currently and in the future. A recent spatial analysis study on cardiovascular health emergencies was done in Milan highlighting the impact of urban features like temperature, access to drinking water fountains and population composition on the city’s heat vulnerability [

17], emphasizing the need for more targeted strategies to protect the groups that are at risk.

The aim of this research is to develop a novel methodology based on open-source GIS data to assess and identify urban areas with the highest health risks for vulnerable populations during heat waves. Specifically, the study proposes an innovative GIS-based methodology that combines Urban Heat Island data, demographic information, and green infrastructure mapping of Milan’s administrative districts. Unlike previous studies that focus either on thermal exposure or on population distribution separately, this study proposes a replicable and widely accessible workflow that combines environmental and social layers to create a risk assessing planning tool. This methodology is designed for scalability and transferability, therefore the data used is publicly available. Being able to combine different datasets, GIS allows for a comprehensive analysis of a city’s environmental context. It facilitates policymakers to take a step further in identifying high risk areas, evaluate the effectiveness of NBS and develop targeted strategies [

18,

19].

2. Materials and Methods

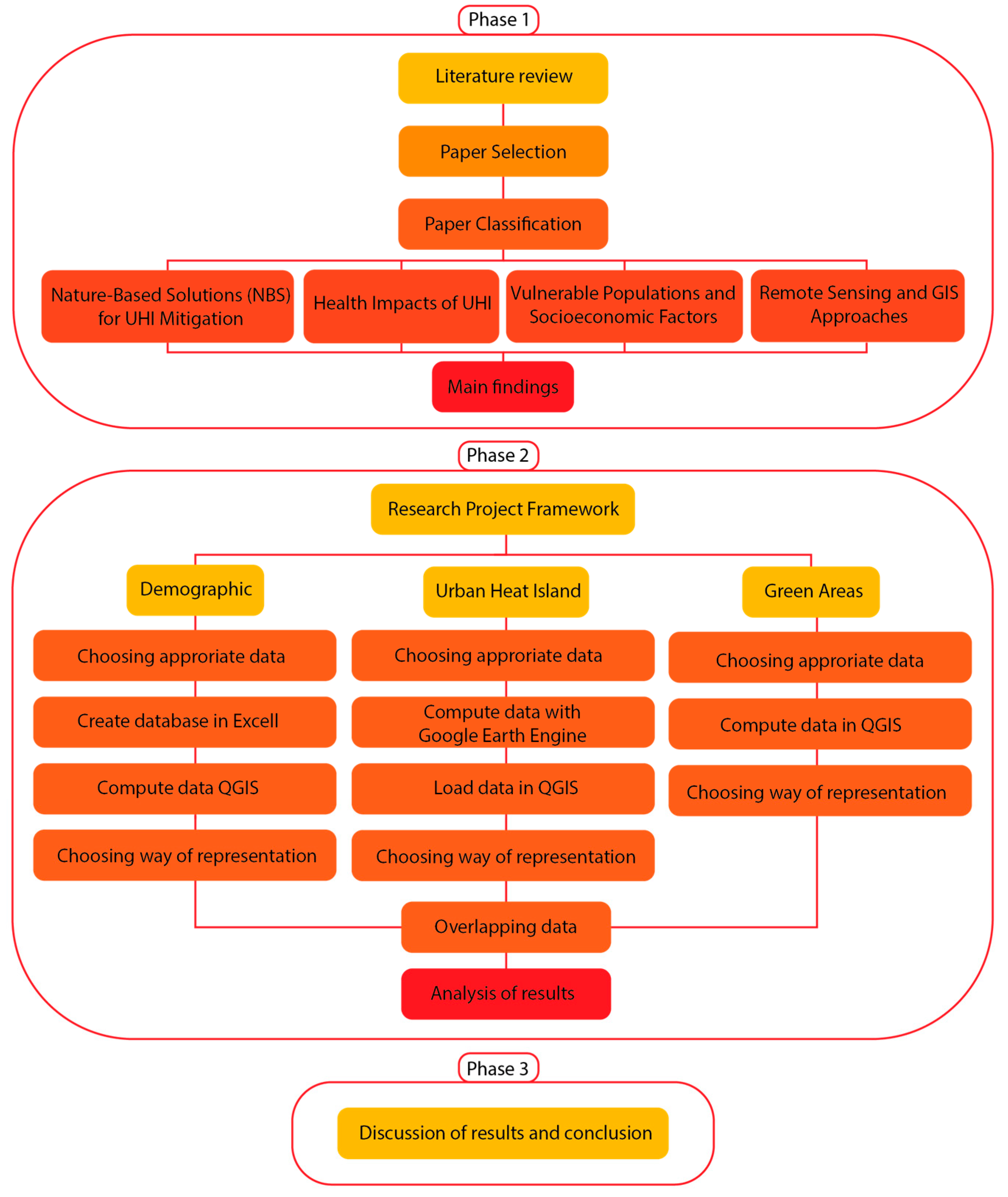

The research project was structured progressively in three main parts: 1) literature review; 2) methodology of spatial mapping and analysis; 3) Application and discussion of results for understanding the relationship between UHI and the vulnerable age groups in Milan. The phases of this project build upon each other, combining scientific research, spatial data analysis and public health issues to create a complete assessment of the risk of heat exposure and potential mitigation approaches.

The study initiates with a broad literature review, considering existing papers on climate change, UHI effects, nature-based solutions (NBS), and their implications for health. The review also assesses the role of remote sensing and GIS-based methodologies in UHI analysis, underlining other studies that incorporate demographic data to assess vulnerability. This initial work guarantees that the project relies on previous knowledge while identifying gaps that show the necessity for further spatial analysis.

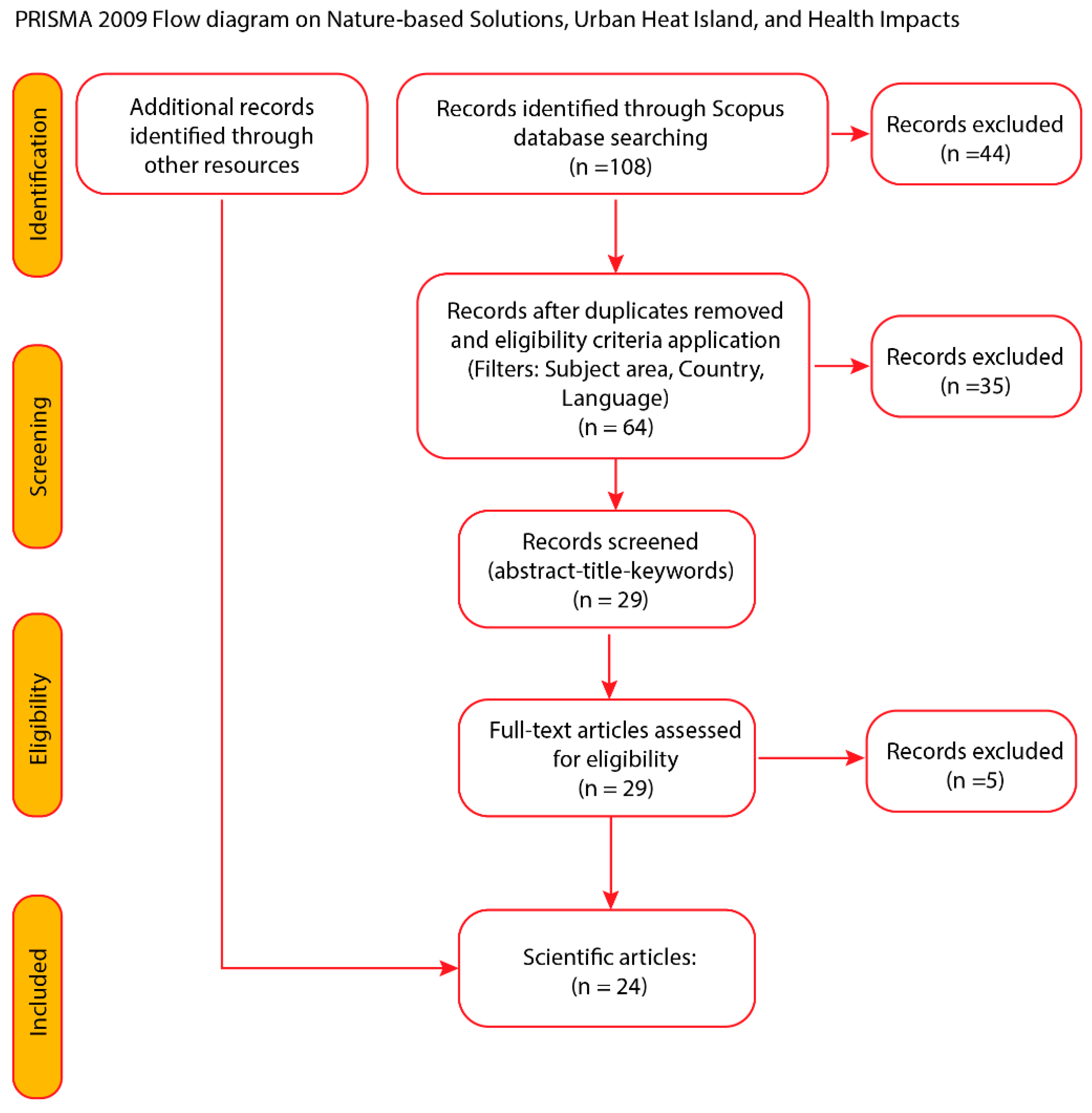

A structured literature review was conducted to evaluate the connections between UHI, nature-based solutions (NBS), and demographic vulnerability in European urban settings. The goal was to establish the basis for a GIS-based risk mapping framework. The first part has been carried out in a few steps using the Scopus database. The first search string was built with the following keywords: “Urban Heat Island” OR “UHI” AND “health” AND “impact” AND “nature-based solution” OR “NBS” OR “cooling”. The reason for using these specific terms was to ensure that the retrieved literature directly touches on the connection between strategies aimed at analysing, mapping and tackling urban heat island effects, their correlation with urban green space’s coverage or presence, and their implication for population health. As shown in the Prisma Diagram (

Figure 1), this initial string led to 108 papers, pondering on different study backgrounds covering various aspects of the searched topics. To refine this list and increase the relevance of the result, a series of filtering criteria were systematically applied. First, duplicates were removed. Then the papers that did not meet the following conditions were eliminated:

- Language: Papers not published in English were subtracted to maintain reliability and accessibility.

- Geographical area: Studies not carried in Europe were removed to ensure relevance to the context of this project.

- Urban Setting: Studies that were not focused on an urban area were omitted.

- Department of research: Papers that were not focused on the relevant research project issues.

Applying these filters to the titles of the articles, it has led to the exclusion of 44 papers, defining a shorter list of 64. These were subjected to a screening where the abstracts were read, out of which another 35 papers were excluded due to not being pertinent to the research objective. After reading the full texts and applying the same filtering criteria, additional five papers were excluded. The final number of scientific articles included in the review was 24.

Figure 1.

Prisma Flow diagram following the Scopus literature review.

Figure 1.

Prisma Flow diagram following the Scopus literature review.

To systematically analyse the existing body of research relevant to this thesis, a structured approach was taken to categorize the selected studies into key thematic areas. Given the interdisciplinary nature of the studies, the literature was grouped into four topics that reflect both the scientific foundations and the practical applications of urban climate adaptation:

- -

Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) for UHI Mitigation:

The reviewed studies examine the implementation of NBS across distinct urban contexts and are assessing their cooling benefits, integration with the city’s heritage and their effectiveness in improving the microclimate [

21,

22]. Ampatzidis P and Kershaw T conducted a comparative analysis of blue spaces’ impact on urban climate adaptation, using remote sensing and climate models and found that blue spaces provide a cooling effect, but their effectiveness varies depending on surrounding land use and urban density [

20]. Mosca EIM et al. conducted a case study in Genoa, using microclimate modelling, field measurements, and public perception surveys to assess NBS benefits demonstrating that NBS not only reduce UHI effects but also improve psychological well-being, enhancing both thermal comfort and mental health [

6]. Olivieri F, Sassenou LN and Olivieri L used GIS and ENVI-met microclimate simulation to quantify NBS effects on UHI, focusing on Matadero, Madrid finding that green infrastructure significantly lowers urban temperatures, with effectiveness dependent on urban morphology and climate conditions [

22]. Vasconcelos L et al. investigated urban green spaces as climate shelters for older adults, using GIS mapping and social analysis and confirmed that elderly populations benefit significantly from urban green spaces, reinforcing their role in reducing heat-related health risks [

3].

- -

Health Impacts of UHI:

The reviewed studies provide strong evidence the effects of UHI on health, worsening cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, indoor thermal comfort, chronic sicknesses, and psychological well-being. Arellano and Roca remote sensing study using Landsat 8 and Sentinel 2 to analyse urban greenery and its impact on nighttime UHI in Barcelona [

23]. Found that urban vegetation significantly reduces nighttime temperatures, mitigating heatwaves and improving public health by decreasing respiratory and cardiovascular risks during extreme heat events. Strong empirical evidence linking heatwaves to an increase in cardiovascular and respiratory emergency calls in Milan may be found in the study of Zendeli [

24]. The researchers discovered hotspots of health vulnerability by mapping Urban Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) values with geolocated emergency calls, showing that regions with higher UTCI values also had higher emergency call rates.

- -

Remote Sensing and GIS Approaches:

The selected papers engage in various analytical approaches, including thermal imaging, spatial modelling, urban morphology analysis, or land cover classification, offering understandings for the influence of urban form, land use, and vegetation patterns on UHI distribution. Alexander C used LiDAR data, NDVI analysis, daytime LST finding that increasing tree height reduces LST by up to 5.75°C, highlighting the cooling effect of vegetation in urban areas [

25]. Arellano and Roca used Landsat 8 and Sentinel 2, GIS-based mapping of land surface temperature (LST) and land surface air temperature (LSAT) and found that nighttime UHI intensifies heat stress, especially in dense urban areas. They also found that large parks reduce temperatures by 1–4°C (day) and 2–5°C (night) [

23].

- -

Vulnerable Populations and Socioeconomic Factors:

This topic critically evaluates key studies that address the connection between UHI, vulnerable populations, and socioeconomic factors. Sánchez CS-G, Peiró MN and González JN used GIS – based mapping and climate data and found neighbourhoods in Madrid with an important presence of vulnerable population located in some of the hottest areas of the city [

12]. Van der Hoeven F and Wandl A mapped land use, UHI, and health implications using GIS and spatial analysis in Amsterdam and found that elderly and low-income populations are disproportionately affected by UHI [

10].

Through this literature review, the most appropriate sources and GIS-based data transfer methodologies for the research were identified.

Subsequently, the research focuses on the application of the methodology selected for mapping and analysing the UHI distribution in Milan, considering the spatial distribution of vulnerable people.

The Selection of the Optimal Heatwave Observation Date

The selection of appropriate Landsat imagery is an important step in creating UHI maps. However, the sixteen-day revisit time of Landsat satellites can be a challenge in assessing the effects of UHIs on specific days during the heatwaves. The images are directly processed in Google Earth Engine (GEE) using Javascript code to visualise the Land Surface Temperature and Urban Heat Islands. After processing the images, they will be inserted as a raster file in Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS) for further analysis and overlapping with the demographic data.

According to Osservatorio Meteorologico Milano Duomo, the hottest day during the 2024 heatwave was 12th of August. This heatwave was recorded between 11th of July and 14th of August (Fondazione OMD, Year). The Landsat 8 and Landsat 9 satellites do not have images from 12th of August considering that the revisit time for data collection is every 8 days. And the cloud cover selected must be <10% for better representation of the LST. After selecting the heatwave date range between 11th of July and 14th of August, the Landsat images available were on 15th, 22nd, 30th and 31st of July and 8th of August. There are images from two consecutive days at the end of July because the satellites operate in complementary orbits, and while each individual satellite has a 16-day revisit period, their combined operation allows for more frequent observations. Out of which 31st of July was the hottest considering the average day temperature graphic of Fondazione OMD - Osservatorio Meteorologico Milano Duomo as shown in Figure 6. This is an image acquired with Landsat-8.

Reading the text information from the acquired images, we can see that it was taken on July 31, 2024, at 10:03:35.9 UTC. The time provided (10:03:35.9 UTC) is in Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) and Milan, Italy, is in the Central European Time (CET) zone, or Central European Summer Time (CEST) during daylight saving time. Therefore, the local time in Milan when the picture was taken is: 10:03:35.9 UTC + 2 hours = 12:03:35.9 CEST.

The Humidex Calculation for the Selected Date and Time

While Land Surface Temperature (LST) is a key metric in UHI research, it does not specifically represent how heat is perceived by the human body. Therefore, the Humidex index is used as complementary tool that accounts for both temperature and humidity, providing a more appropriate measure of thermal discomfort. The paper titled “Thermal Environment Assessment Reliability of Humidity Indices” explores the accuracy of different thermal indices and confirms that Humidex effectively represents human discomfort in humid urban areas, making it a relevant choice for Milan. The study points out that while Wet-Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) and Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) require additional parameters like solar radiation and wind speed, which are not always available, Humidex relies on air temperature and humidity, making it a more practical tool for large-scale urban heat evaluations [

26].

Even though it was not possible to extract the hottest day during the heatwave, due to the satellite’s revisit period, the subsequently selected day was optimal for the purpose of this research, given the focus of the vulnerable population. The ranges of Humidex discomfort are as follows: 30°C ≤ HD ≤ 39°C representing some discomfort, 40°C ≤ HD ≤ 45°C meaning great discomfort and avoid exertion, and anything over 45°C is dangerous. According to Weather Underground data, on the 31st of July, at the exact time the satellite image was acquired, between 11:50 am and 12:20 pm the recorded temperature was 90 °F, and the dew point 68 °F, which were used to calculate the Humidex index. It resulted in 40°C at the time of the satellites’ visit. During the same day, only after 2 hours the humidex index was 43°C, when caution would be advised. Comparing with the hottest registered day within that heatwave period, the 12th of August, the peak Humidex was noted at 43.4°C.

The Selection of the Geographical Unit for the Analysis

The analysis is based on Local Identity Units (Nuclei di Identità Locale - NIL), a more detailed and targeted administrative boundary system of zoning and gathering demographic data in Milan. These were acquired from the administrative geoportal of the Municipality of Milan. To continue the analysis, these maps were overlaid with the data from the NIL database, helping the identification of areas where high temperatures overlap with the density of vulnerable age groups in the current scenario and for future projections (2030).

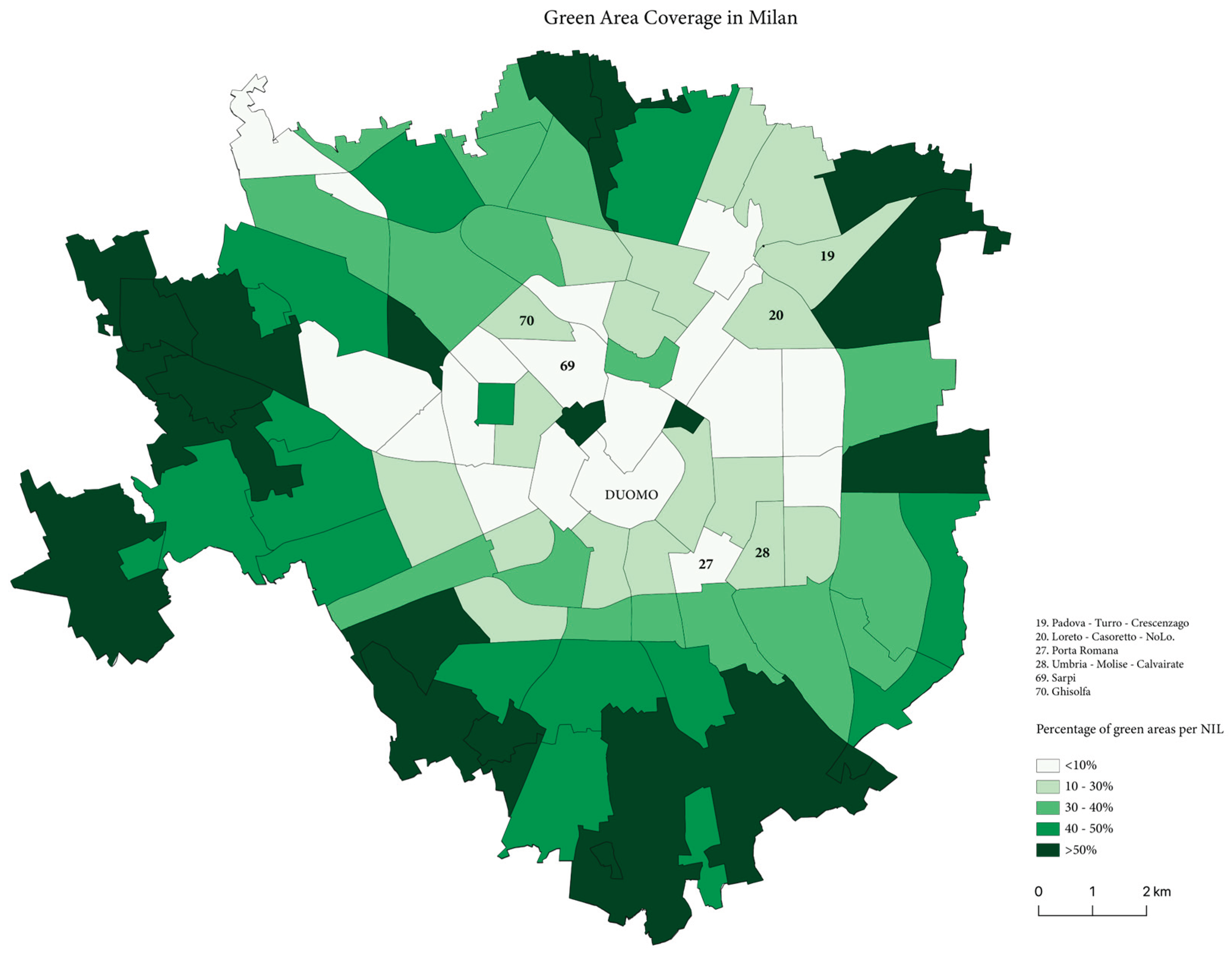

Selection of Green Infrastructure Data

NDVI-based approaches were considered in the early stages of the research to estimate vegetation cover. However, NDVI measures vegetation health, while this study focused on mapping urban heat exposure and demographic vulnerability. Additionally, in a dense urban context like Milan, NDVI outputs were found to be inconsistent due to mixed land uses and fragmented greenery. These limitations reduced the interpretability of NDVI at the neighbourhood scale and reinforced the decision to rely on detailed vector-based land use data for assessing green infrastructure.

Consequently, green infrastructure was ultimately assessed using official land use and vegetation shapefiles provided by the Municipality of Milan and the DUSAF 2021 dataset (Land Use 2021). These vector layers offer detailed typological classifications allowing for the calculation of green area percentages per NIL (Nucleo di Identità Locale) with a higher degree of spatial accuracy. From these categories, the ones considered to have a higher cooling potential such as tree rows and larger urban parks [

27] were selected for this study.

The final phase comprises the analysis and interpretation of spatial mapping results. This phase has been crucial for the assessment of the areas of heat exposure, the relationship between UHI and vulnerable communities, and the role of green infrastructures in mitigating extreme heat. The complete framework of the methodology performed for this study is shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research methodology framework.

Figure 1.

Research methodology framework.

3. Results

To better understand the risks maps, the context of the calculations that lead up to the final values need to be comprehended first.

For this risk assessment, sub-dividing the city in neighbourhood scale units was essential for evaluating both the density of vulnerable populations (children and the elderly) and the intensity of UHI during heat waves. This division allowed for analysis within smaller and homogenous areas. Milan is already split into 88 Local Identity Units (Nuclei di Identità Locale – NILs), thus, they were used as the spatial units for this analysis. For determing the LST, surface temperature inputs from the Landsat 8 satellite (open-source data) were used, specifically from the day with available data within the heat wave in Milan in 2024 (July 31st). The satellite imagery was processed for generating thermal maps using Google Earth Engine (GEE).

When computing the maps in GEE, the code also calculated the average Land Surface Temperature (LST) of Lombardia which is 33.96°C and of Milan, 40.8°C. Firstly, these results indicate a significant temperature difference of +6.85°C between Milan and its surrounding Lombardia region. This highlights that Milan is itself, a heat island in the north of Italy. This is due to the major urbanization and high density of impermeable land cover comparing to surrounding areas that benefit from vegetation and its evaporative cooling. Furthermore, the substantial temperature variations within Milan were highlighted. To analyse this, as mentioned before in the methodology, the UHI index was computed for each NIL. For more comprehensive understanding and reading of the values shown on the map, the UHI values were converted back to degrees Celsius using the standard deviation of LST in Milan (5.14°C), a value computed in GEE.

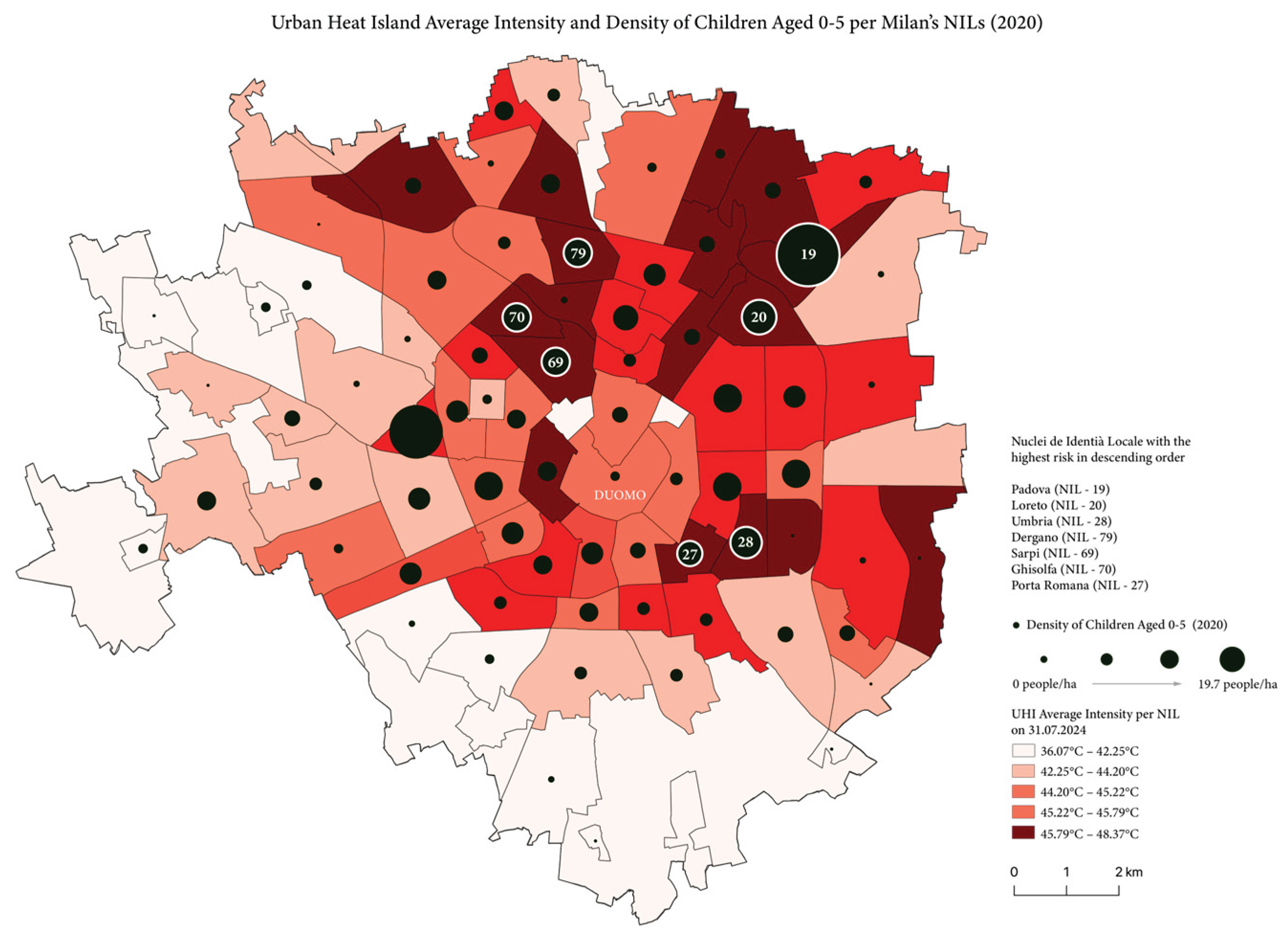

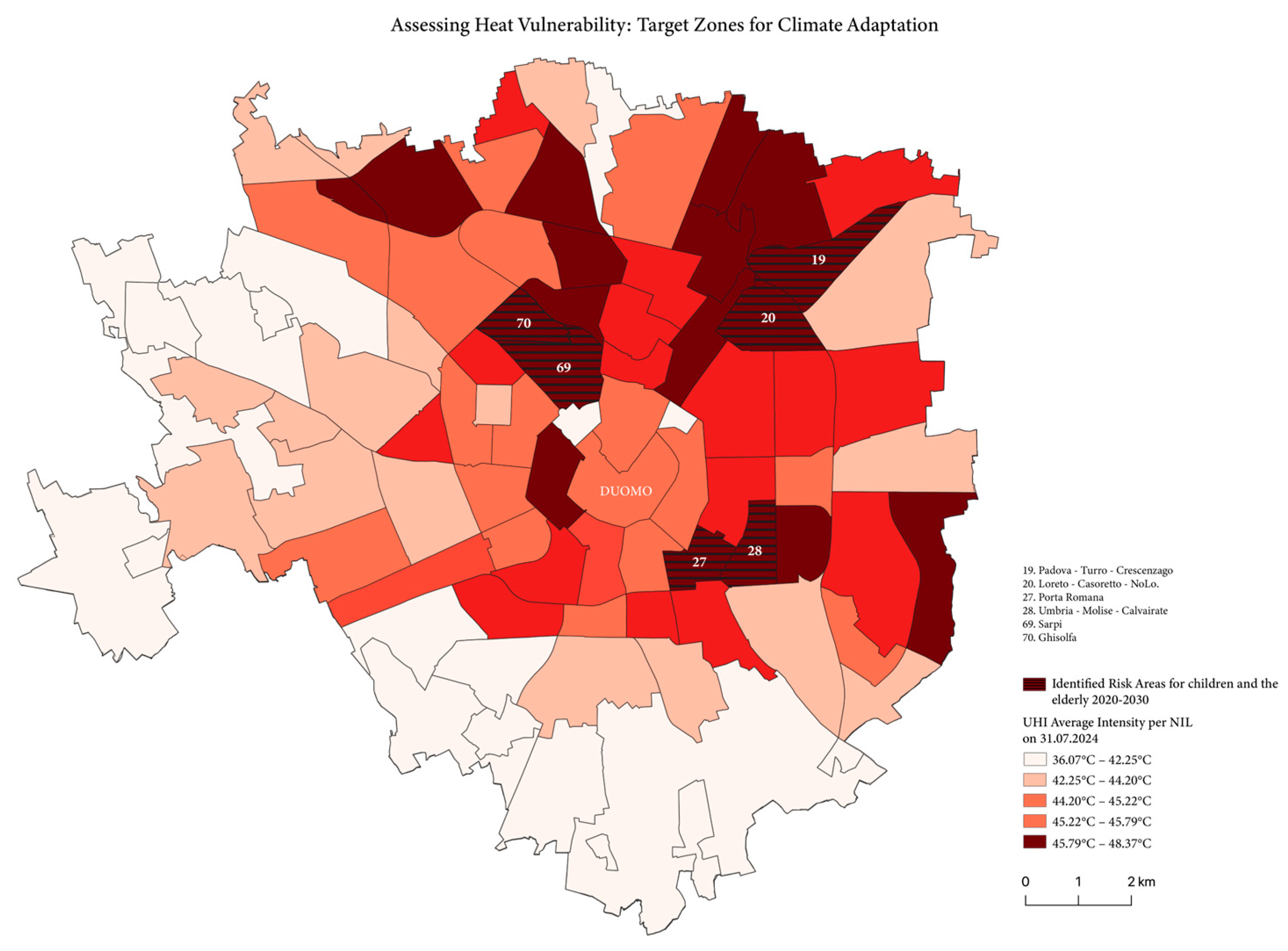

The results show a broad range of temperatures between the NILs. When reading this map, the UHI intensity average per NIL had a baseline represented by the citywide mean LST temperature on the 31st of July, of 40.8°C. As shown in the legend in

Figure 2, the UHI average intensity ranges from 36.07°C to 48.37°C in land surface temperature. This means the coolest NIL is 4.37°C less than Milan’s average of 40.8°C, calculated within GEE, and the hottest NIL is 7.56°C higher than the average.

To evaluate the UHI's risk, another Excel database was made with the densities of vulnerable population per age group inside each NIL, using public demographic open source data. For each vulnerable group, GIS maps were developed showing the population density per NIL for the years of 2020 and 2030. Then, an overlay analysis was performed for each NIL, comparing vulnerable age groups with corresponding UHI values. Consequently, four maps were created: Urban Heat Island average intensity and density of children (aged 0–5) per NIL in 2020 (

Figure 2) and 2030; and Urban Heat Island average intensity and density of the elderly (aged 65+) per NIL in 2020 (

Figure 3) and 2030.

To provide clearer comparison across neighbourhoods, the children and elderly density data was overlapped with UHI intensity data in an Excel database. This allowed to identify the NILs with the highest risk within the vulnerable demographic density table, highlighting the most heat-exposed neighborhoods.

In

Figure 2 the Urban Heat Island (UHI) intensity across Milan’s NIL districts data is overlaid with the dark circles representing the density of children aged 0–5 years (2020), with graduated symbols indicating higher density. The map highlights Padova as the most critical NIL, where both the UHI index and the density of young children are particularly high. In descending order of risk, the other precarious neighbourhoods are Loreto (NIL - 20), Umbria (NIL - 28), Dergano (NIL – 79), Sarpi (NIL - 69), Ghisolfa (NIL - 70), and Porta Romana (NIL - 27).

The analysis of the map indicates that the NILs of Padova and San Siro exhibit the highest densities of children aged 0–5. Notably, San Siro is also among the most affected areas by elevated UHI intensity. Furthermore, the map reveals that other NILs with a high proportion of young children are predominantly located in zones with the highest recorded UHI values.

Another crucial aspect to highlight is that the hottest NILs are located in the northern and eastern part of the city, while the ones in southern and western sides (which are close to the big green area of the Parco Agricolo Sud Milano), turned out to be less critical neighbourhoods. Particularly, the hottest area in Milan is Magenta (NIL – 7), followed by Centrale (NIL – 10), Greco (NIL – 13) and Bicocca (NIL – 15). Moreover, Magenta (NIL – 7) has even a relatively high concentration of elderly that is projected to have a significant growth in 2030.

Another notable spatial pattern is the concentration of the highest UHI intensities in the northern and eastern parts of Milan, whereas the NILs located in the southern and western areas (particularly those bordering the Southern Agricultural Park) exhibit significantly lower surface temperatures. The NIL of Magenta (NIL – 7) emerges as the hottest area in the city, followed by Centrale (NIL – 10), Greco (NIL – 13), and Bicocca (NIL – 15). Of particular concern is Magenta: not only it records the highest UHI values, but it also has a relatively high density of elderly residents. Morevoer, the demographic projection shows a substantial increase of the elderly population by 2030, further heightening the area’s vulnerability to extreme heat.

In the risk maps showing the projection of the population density for children in 2030, the critical NILs remain relatively stable, being consistent with those identified in 2020.

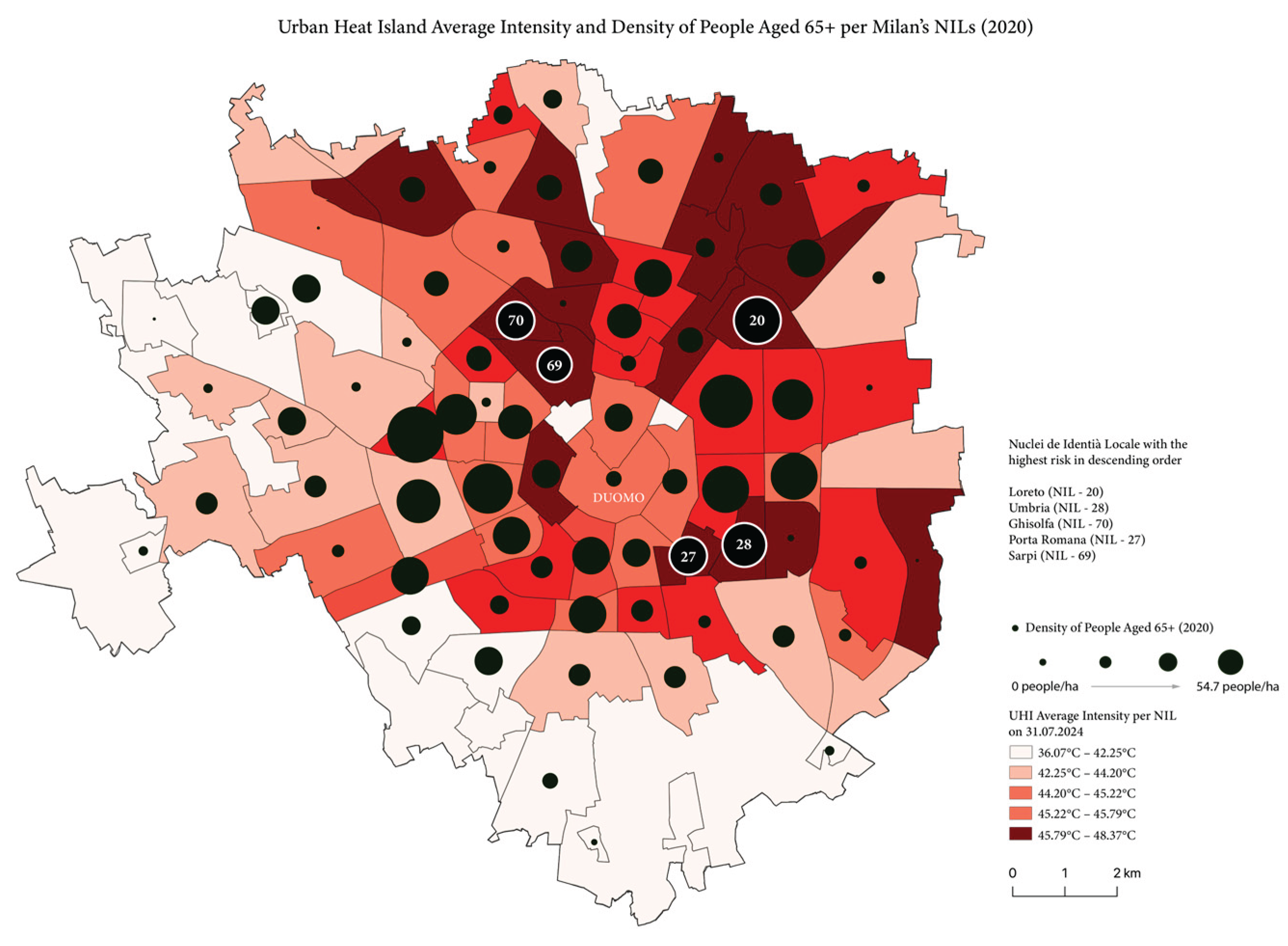

The density of individuals aged 65 and over is depicted in

Figure 3 and overlaid with the UHI intensity map per NIL. Dark circles denote the elderly population density, with larger circles representing higher concentrations. The map elicits highly critical heat-vulnerable districts, as Loreto (NIL - 20), Umbria (NIL - 28), Ghisolfa (NIL - 70), Porta Romana (NIL - 27) and Sarpi (NIL - 69).

The comparison of the map of the elderly population density with the one about the children reveals that older adults are more densely distributed across Milan. The maximum density for the elderly reaches approximately 25 people/ha, surpassing the children’s peak density of around 19 people/ha, indicating a generally higher occurrence of older adults in most NILs. Beyond the most heat vulnerable districts, medium-high risk NILs also emerged (in red colours), including Selinunte (NIL – 57), Buenos Aires (NIL – 21), XII Marzo (NIL – 26), Citta Studi (NIL – 22), Ticinese (NIL – 44), and Isola (NIL – 11).

For example, the highest density of people over 65 years old have been found in Loreto 44.8 people/ha, which is ranked as the 10th hottest area, while the highest density of children is in Padova with 19.7 people/ha (1.970 pp/Km2).

In the risk maps projecting the elderly population density for 2030, a greater number of NILs are classified as high-risk compared to 2020. Notably, Dergano and Magenta are expected to emerge as new high-density elderly areas, indicating an expansion of aging population in different neighbourhoods.

The overlap concerning NILs with high density of vulnerable people and the hottest zones identified in UHI mapping underlines an important persistent connection between climate risk and social vulnerability. Loreto (NIL - 20), Umbria (NIL - 28), Padova (NIL - 19), Ghisolfa (NIL - 70), Sarpi (NIL - 69), and Porta Romana (NIL - 27) consistently emerge within the vulnerable age groups (elderly and children) in 2020 and also in the maps of 2030 projections. Besides facing high heat exposure, these areas also house populations that are less resilient to extreme heat, making them crucial locations for targeted interventions.

Figure 4 spatially places the comprehensive risk index for children and the elderly resulted from the database overlapping the highest density of vulnerable population age groups in 2020 and in 2030 projections and peak UHI intensity.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of green areas per NIL to highlight the correlation with the high-risk zones for vulnerable age groups in 2020 and 2030. A clear inverse correlation is observed between UHI intensity and green area density, underscoring the role of vegetation in mitigating urban heat. Notably, NILs with the highest concentration of vulnerable population, consistently correspond to areas with limited green infrastructure. This spatial overlap highlights these districts as critical targets for future nature-based interventions aimed at reducing thermal stress and enhancing climate resilience. Moreover, proximity to green areas is essential for the physical and mental health of elderly people and children, reducing stress, and encouraging outdoor activity. Due to their cooling effect, green spaces provide safer spaces for age groups with thermal regulation sensitivity, especially young children and the elderly.

4. Discussion

The spatial analysis performed offers a comprehensive understanding of Urban Heat Island (UHI) intensity in Milan and its relationship with demographic vulnerability and distribution of green infrastructure. Through mapping, distinct spatial patterns reveal areas where extreme heat exposure overlaps with at-risk populations, particularly children (0-5 years old) and the elderly (65+ years old). These findings reinforce existing literature, which found that spatial mismatches between ecosystem services and vulnerable populations can exacerbate heat-related inequalities in urban areas. Additionally, the green space distribution map highlights a clearly inverted relationship between vegetation coverage and UHI intensity, emphasizing the critical role of Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) in mitigating urban heat. These findings strengthen existing literature that finds vegetation to be an important cooling strategy, reducing surface temperatures through shading and evapotranspiration processes.

Several NILs consistently emerge in both 2020 and 2030 as having a high density of elderly residents, respectively over 30 people per hectare. These include Loreto (NIL - 20), Umbria (NIL - 28), Padova (NIL - 19), Ghisolfa (NIL - 70), Sarpi (NIL – 69), and Porta Romana (NIL - 27), which should be priority areas for heat mitigation strategies over the next decade. Additionally, Dergano (NIL – 79) and Magenta (NIL – 07) are projected to emerge as new high-density elderly areas by 2030, signifying an expansion of aging populations into different neighbourhoods. The persistence of certain NILs across the 10-year difference suggests that these areas will continue to have substantial aging residents, emphasizing their long-term vulnerability to extreme heat events. The demographic modification observed in Dergano (NIL – 79) and Magenta (NIL – 07) also stresses that the risks are expanding into new areas, demanding the implementation of adaptation strategies while thinking forward.

Older populations are more vulnerable to extreme heat because of reduced thermoregulation, pre-existing health conditions, and social isolation. As emphasized by [

3], exposure to urban heat disproportionately affects elderly residents, and 54% of older adults in Barcelona use green spaces as primary means for cooling. Therefore, Milan’s NILs with high elderly population densities should be prioritized for UHI adaptation measures such as expanding urban greening and higher tree canopy coverage in pedestrian zones, increasing shaded public spaces and cooling centres.

The NILs with the highest density of children, respectively those over 19.7 children per hectare, remain relatively stable, with almost all appearing in both 2020 and 2030 projections. Padova (NIL - 19), Loreto (NIL - 20), Umbria (NIL - 28), Porta Romana (NIL - 27), Dergano (NIL – 79), Sarpi (NIL – 69), and Ghisolfa (NIL – 70) consistently exhibit high densities of young children, indicating that these areas will continue to be high risk neighbourhoods for heat exposure for children. This persistence of high density of children stresses the important need for child-friendly heat adaptation planning in these areas.

Children are more sensitive to heat stress due to dehydration risks and their underdeveloped thermoregulatory systems and pregnant women risk giving birth to children with lower body wights [

10]. The aforementioned NILs should be selected for interventions like shaded and vegetated play areas in residential regions, water features and cooling facilities in schools and public parks and incorporating heat adaptation strategies in childcare and health centers. Due to children having lower regulation of body temperature and being dependent on caregivers, implementing heat-adaptive urban planning that focuses on thermal comfort and safety in areas with more families is crucial.

The persistent overlap concerning NILs with high density of vulnerable people and the hottest zones identified in UHI mapping underlines an important connection between climate risk and social vulnerability. Loreto (NIL - 20), Umbria (NIL - 28), Padova (NIL - 19), Ghisolfa (NIL – 70), Sarpi (NIL – 69), and Porta Romana (NIL - 27), consistently emerge within the vulnerable age groups (elderly and children) in both 2020 and 2030 projections. Besides facing high heat exposure, these areas also house populations that are less resilient to extreme heat, making them crucial locations for targeted interventions.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the value of integrating GIS-based spatial analysis with demographic and environmental data to identify heat vulnerability in urban areas. By combining Urban Heat Island intensity, green infrastructure distribution, and vulnerable age groups demographic projections, the methodology supports targeted climate adaptation strategies. The approach is scalable, allowing application across multiple geographic levels, from neighbourhoods to cities or regions. It is also adaptable, as additional layers such as socio-economic, epidemiological, environmental, and infrastructural data can be incorporated for more comprehensive risk assessments. Furthermore, the method is replicable, relying on open-source tools and publicly accessible data.

6. Limitations and Further Developments

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of relying on using satellite-derived LST alone as an indicator of human-perceived thermal stress. LST represents surface temperature, which differs from actual ambient conditions experienced by individuals. Human thermal comfort is influenced by a combination of variables such as air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation, which LST does not capture on its own. As shown in recent literature [

28], the use of comprehensive thermal indices such as the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI), the Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET) and PALM model system for microscale simulations, can have high-resolution outputs for accurate representations of outdoor heat stress by integrating multiple meteorological inputs. Additionally, evaluating the thermal performance of shade and the use of physically based microclimate models such as ENVI-met [

29] can improve the small-scale dimension of this analysis.

However, due to data limitations and the spatial scale of this research, such indices were not implementable within the scope of the study. Instead, LST was selected as a practical and replicable metric, widely used in urban climate research, particularly for large-scale analysis. To partially address this, we incorporated the Humidex index, calculated for the same date and time as the available satellite imagery, using ground-level air temperature and dew point data. This provided a supplementary indication of thermal discomfort and confirmed that the selected date represented severe heat stress conditions. We recognize that future research should aim to integrate more refined thermal indices and ground validation to enhance the precision of the study.

The analysis was intentionally focused on a single representative day within the 2024 heatwave, rather than a temporal composite, to align thermal conditions with demographic vulnerability using the Humidex index. While this approach is focused on a single day risk snapshot, we acknowledge that for identifying persistent or seasonal UHI patterns, it would be beneficial in future studies to incorporate multiple satellite images within the heatwave.

Looking forward, there is a need for the digitalization of urban and demographic datasets in editable formats such as Excel, CSV, or geolocated GIS packages. Additionally, better organization and accessibility of spatial and statistical data by public institutions would significantly enhance the quality and efficiency of such research, enabling more informed and equitable urban planning decisions.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UHI |

Urban Heat Island |

| LST |

Land Surface Temperature |

| GEE |

Google Earth Engine |

| GIS |

Geographic Information Systems |

| NBS |

Nature-Based Solutions |

| NIL |

Nuclei di Identità Locale |

References

- Grilo, F.; et al. «Using green to cool the grey: Modelling the cooling effect of green spaces with a high spatial resolution». Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 724, 138182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantari, Z.; Ferreira, C.S.S.; Pan, H.; Pereira, P. «Nature-based solutions to global environmental challenges». Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, L.; Langemeyer, J.; Cole, H.V.S.; Baró, F. «Nature-based climate shelters? Exploring urban green spaces as cooling solutions for older adults in a warming city». Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 98, 128408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; et al. «Climate Change and Children’s Health—A Call for Research on What Works to Protect Children». Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2012, 9, 3298–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capari, L.; Wilfing, H.; Exner, A.; Höflehner, T.; Haluza, D. «Cooling the City? A Scientometric Study on Urban Green and Blue Infrastructure and Climate Change-Induced Public Health Effects». Sustainability 2022, 14, 4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, F.; Sani, G.M.D.; Giachetta, A.; Perini, K. «Nature-Based Solutions: Thermal Comfort Improvement and Psychological Wellbeing, a Case Study in Genoa, Italy». Sustainability 2021, 13, 11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznarez, C.; Kumar, S.; Marquez-Torres, A.; Pascual, U.; Baró, F. «Ecosystem service mismatches evidence inequalities in urban heat vulnerability». Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfredi, V.; et al. «Urban Green Spaces and Public Health Outcomes: a systematic review of literature». Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31 (Suppl. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nations, U. «Ageing». United Nations. Consultato: 6 maggio 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/ageing.

- Van Der Hoeven, F.; Wandl, A. «Amsterwarm: Mapping the landuse, health and energy-efficiency implications of the Amsterdam urban heat island». Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2015, 36, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alied, M.; Huy, N.T. «A reminder to keep an eye on older people during heatwaves». Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e647–e648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.S.-G.; Peiró, M.N.; González, F.J.N. Madrid». In Sustainable Development and Renovation in Architecture, Urbanism and Engineering; Mercader-Moyano, P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppio, A.; Caprioli, C.; Dell’Ovo, M.; Bottero, M. «Assessing Ecosystem Services through a multimethodological approach based on multicriteria analysis and cost-benefits analysis: A case study in Turin (Italy)». J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 472, 143472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradelos, E.; Papathanasiou, I.; Mitsi, D.; Tsaras, K.; Kleisiaris, C.; Kourkouta, L. «Health Based Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and their Applications». Acta Inform. Med. 2014, 22, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khashoggi, B.F.; Murad, A. «Issues of Healthcare Planning and GIS: A Review». ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwaet, D.; et al. «High resolution modelling of the urban heat island of 100 European cities». Urban Clim. 2024, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaro, J.; Gianquintieri, L.; Pagliosa, A.; Sechi, G.M.; Caiani, E.G. «Neighborhood determinants of vulnerability to heat for cardiovascular health: a spatial analysis of Milan, Italy». Popul. Environ. 2024, 46, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, F.; Leone, F.; Pittau, R. «Evaluating the urban heat island phenomenon from a spatial planning viewpoint. A systematic review». TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2023, 2, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchin, O.; Hoelscher, M.-T.; Meier, F.; Nehls, T.; Ziegler, F. «Evaluation of the health-risk reduction potential of countermeasures to urban heat islands». Energy Build. 2016, 114, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampatzidis, P.; Kershaw, T. «A review of the impact of blue space on the urban microclimate». Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 730, 139068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, M.A.; Viles, H.A. «Integrating nature-based solutions and the conservation of urban built heritage: Challenges, opportunities, and prospects». Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 63, 127192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, F.; Sassenou, L.-N.; Olivieri, L. «Potential of Nature-Based Solutions to Diminish Urban Heat Island Effects and Improve Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Summer: Case Study of Matadero Madrid». Sustainability 2024, 16, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, B.; Roca, J. «EFFECTS OF URBAN GREENERY ON HEALTH. A STUDY FROM REMOTE SENSING». Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendeli, D.; et al. «From heatwaves to ‘healthwaves’: A spatial study on the impact of urban heat on cardiovascular and respiratory emergency calls in the city of Milan». Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 124, 106181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C. «Influence of the proportion, height and proximity of vegetation and buildings on urban land surface temperature». Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2021, 95, 102265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, F.R.D.M.R.S.O.; Palella, B.I.; Riccio, G. «Thermal Environment Assessment Reliability Using Temperature —Humidity Indices». Ind. Health 2011, 49, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.; et al. «Green spaces are not all the same for the provision of air purification and climate regulation services: The case of urban parks». Environ. Res. 2018, 160, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, J.; Schubert, S.; Maronga, B.; Salim, M. «Simplifying heat stress assessment: Evaluating meteorological variables as single indicators of outdoor thermal comfort in urban environments». Build. Environ. 2025, 274, 112658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middel, A.; AlKhaled, S.; Schneider, F.A.; Hagen, B.; Coseo, P. «50 Grades of Shade». Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, E1805–E1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).