Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background and Preliminaries

2.1. Distributed Training Paradigms

- Data Parallelism (DP): Each worker holds a full replica of the model and processes a unique batch shard. Gradients are averaged via all-reduce operations:where K is the number of devices [23].

- Tensor Parallelism (TP): Splits tensors across multiple devices. For instance, a matrix multiplication is computed by partitioning A column-wise and B row-wise, with intermediate aggregation.

- Pipeline Parallelism (PP): Model layers are partitioned into segments and assigned to pipeline stages. Each microbatch flows through stages in a staggered fashion [24].

- Hybrid Parallelism: Combines DP, TP, and PP hierarchically to scale to trillion-parameter models with minimal memory and latency overhead [25].

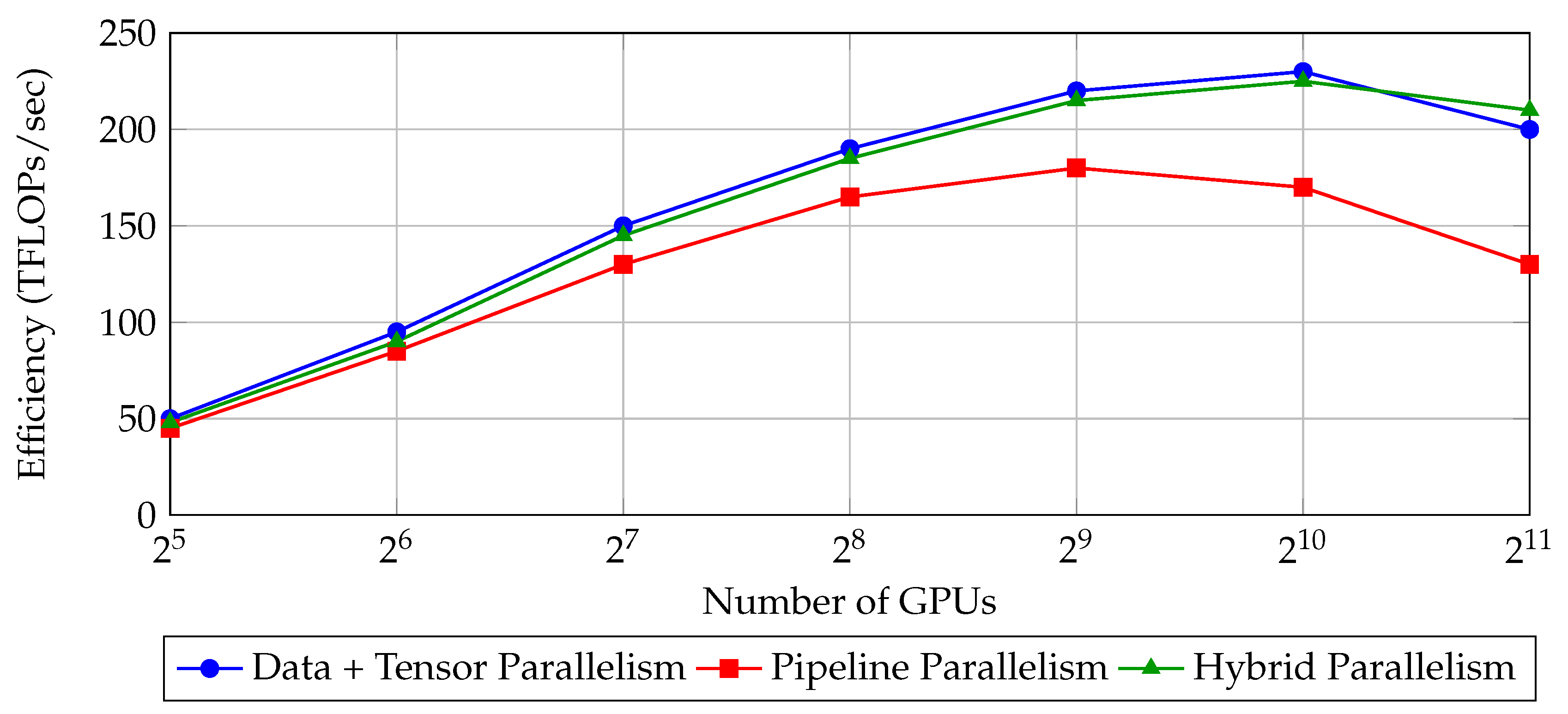

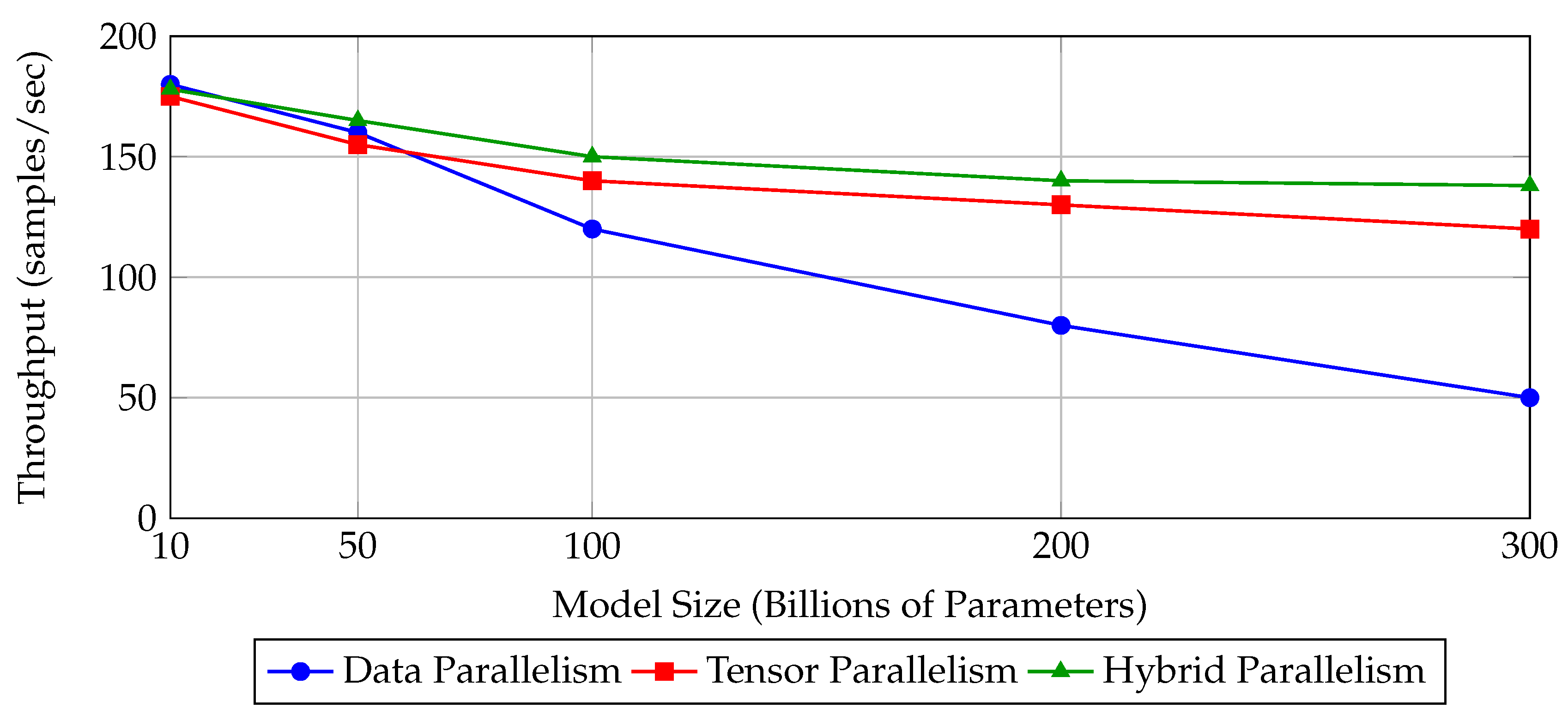

2.2. Scaling and Efficiency Visualization

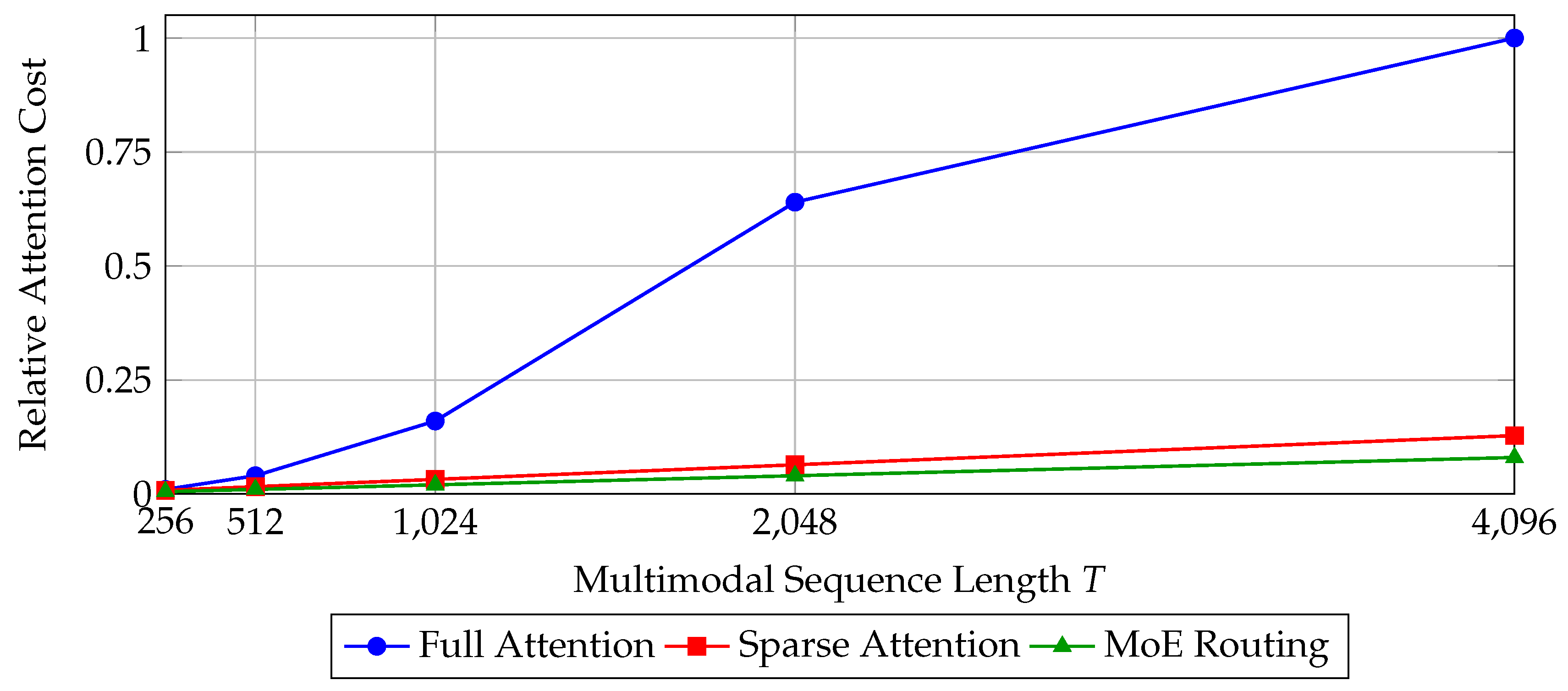

2.3. Multimodal Fusion Formalism

3. Distributed Training and Inference for LLMs

3.1. Parallelism Taxonomy and Scheduling

3.2. ZeRO: Memory-Efficient Data Parallelism

3.3. Inference Optimization and Quantization

3.4. Empirical Scaling of Throughput

3.5. Summary

4. Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs)

4.1. Modular Architecture and Embedding Alignment

4.2. Fusion Strategies and Temporal Modeling

- Early Fusion: Tokens from different modalities are concatenated before encoding, i.e., [56].

- Late Fusion: Independent modality outputs are combined at the decision layer, e.g., where is an MLP or attention function.

- Cross-Attention Fusion: One modality acts as a query over keys/values of another, as in [57].

4.3. MLLM Architectural Comparison

4.4. Scaling Multimodal Input Length

4.5. Summary

5. Challenges and Open Problems

5.1. Scalability Bottlenecks in Distributed Environments

5.2. Cross-Modal Representation Alignment

5.3. Evaluation and Benchmarks

5.4. Trade-offs in Model Design

5.5. Ethical, Social, and Data Bias Challenges

5.6. Summary

6. Future Directions

6.1. Unified Multimodal Memory-Augmented Architectures

6.2. Modular, Composable LLM Systems

6.3. Toward Self-Aligning and Self-Evaluating LLMs

6.4. Emergence of Continual and Lifelong Multimodal Agents

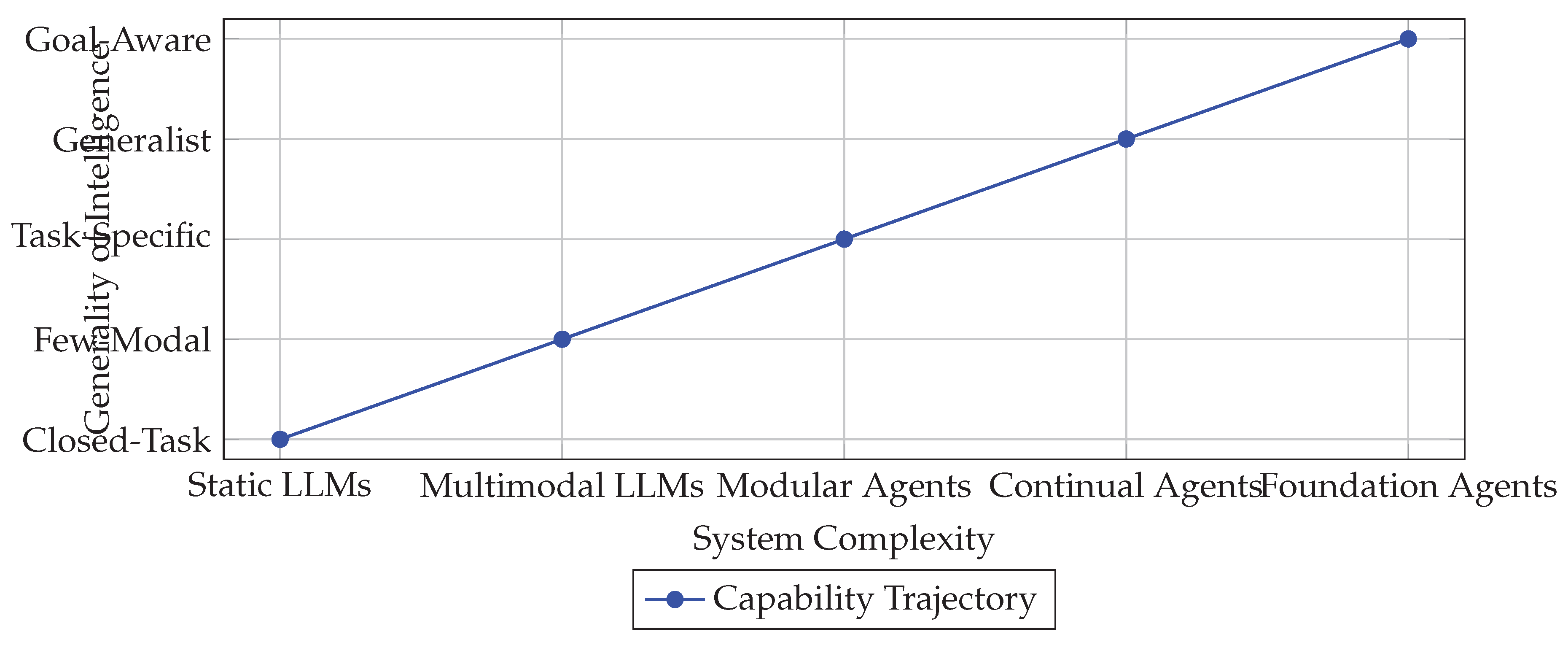

6.5. Toward General-Purpose Foundation Agents

- Causality-aware reasoning to distinguish correlation from intervention [96].

- Goal-conditioned generation with latent goal variables g, such that outputs are steered by high-level intent.

- Embodied learning where language and perception are grounded in sensorimotor experiences, leading to emergent affordances and world models [97].

6.6. Roadmap Summary

6.7. Concluding Remarks

7. Conclusions

References

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Yang, A.; Fan, A.; et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, C.T.; Chen, L.; Xuesong, Y.; Xudong, Z.; Bo, F. FedPEAT: Convergence of Federated Learning, Parameter-Efficient Fine Tuning, and Emulator Assisted Tuning for AI Foundation Models with Mobile Edge Computing. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.17491. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Li, W.; Yang, G.; Qiu, X.; Guo, S. Federated Learning Meets Edge Computing: A Hierarchical Aggregation Mechanism for Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Wireless Algorithms, Systems, and Applications. Springer, 2022, pp. 456–467.

- Abrahamyan, L.; Chen, Y.; Bekoulis, G.; Deligiannis, N. Learned gradient compression for distributed deep learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 33, 7330–7344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, E. Task Scheduling for Decentralized LLM Serving in Heterogeneous Networks. Technical Report No. UCB/EECS-2024-111 2024.

- Wu, L.; Zheng, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, H.; Gu, H.; Shen, T.; Qin, C.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Q.; et al. A survey on large language models for recommendation. World Wide Web 2024, 27, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.H.; Yatskar, M.; Yin, D.; Hsieh, C.J.; Chang, K.W. Visualbert: A simple and performant baseline for vision and language. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.03557. [Google Scholar]

- Fahad, M.; Shojafar, M.; Abbas, M.; Ahmed, I.; Ijaz, H. A multi-queue priority-based task scheduling algorithm in fog computing environment. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 2022, 34, e7376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, D.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, S.; Kuang, K.; Wu, F. An Adaptive Aggregation Method for Federated Learning via Meta Controller. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 6th ACM International Conference on Multimedia in Asia Workshops, 2024, pp. 1–1.

- Zhao, D. FRAG: Toward Federated Vector Database Management for Collaborative and Secure Retrieval-Augmented Generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.13272. [Google Scholar]

- Choromanski, K.; Likhosherstov, V.; Dohan, D.; Song, X.; Gane, A.; Sarlos, T.; Hawkins, P.; Davis, J.; Mohiuddin, A.; Kaiser, L.; et al. Rethinking attention with performers. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.14794. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar]

- Brants, T.; Xu, P. Distributed language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Human Language Technologies: The 2009 Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Companion Volume: Tutorial Abstracts, 2009, pp. 3–4.

- Brown, T.; et al. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS, 2020.

- Chen, J.; Guo, H.; Yi, K.; Li, B.; Elhoseiny, M. Visualgpt: Data-efficient adaptation of pretrained language models for image captioning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 18030–18040.

- Taylor, R.; Kardas, M.; Cucurull, G.; Scialom, T.; Hartshorn, A.; Saravia, E.; Poulton, A.; Kerkez, V.; Stojnic, R. GALACTICA: A Large Language Model for Science. 2022.

- Alayrac, J.B.; Recasens, A.; Schneider, R.; et al. Flamingo: a Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.14198. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Ding, B. Improving loRA in privacy-preserving federated learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.12313. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. GPT-4V System Card, 2023. Accessed: 2024-10-29.

- Shen, X.; Kong, Z.; Yang, C.; Han, Z.; Lu, L.; Dong, P.; Lyu, C.; Li, C.h.; Guo, X.; Shu, Z.; et al. EdgeQAT: Entropy and Distribution Guided Quantization-Aware Training for the Acceleration of Lightweight LLMs on the Edge. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.10787. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; et al. Finetuned Language Models Are Zero-Shot Learners. ArXiv:2109.01652 2021.

- Ghiasvand, S.; Yang, Y.; Xue, Z.; Alizadeh, M.; Zhang, Z.; Pedarsani, R. Communication-Efficient and Tensorized Federated Fine-Tuning of Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.13097. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Cheng, F.; Du, Z.; Kiessling, J.; Ku, J.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Ma, M.; Molom-Ochir, T.; Morris, B.; et al. A Survey: Collaborative Hardware and Software Design in the Era of Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.07265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Chen, Q.; Wei, W.; Lin, Z.; Chen, X.; Huang, K. Mobile edge intelligence for large language models: A contemporary survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.18921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, I.; Vladu, A.; Guo, Q.; Alistarh, D. Quantized distributed training of large models with convergence guarantees. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 24020–24044.

- Xing, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Gu, X.; Wang, Y. A survey of efficient fine-tuning methods for vision-language models—prompt and adapter. Computers & Graphics 2024, 119, 103885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Efficient tensor decomposition-based filter pruning. Neural Networks 2024, 178, 106393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, B.; Wang, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Tian, Y. Galore: Memory-efficient LLM training by gradient low-rank projection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.03507. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Jin, H.; Shah, A.D.; Han, S.; Hu, Z.; Ran, Y.; Stripelis, D.; Xu, Z.; Avestimehr, S.; He, C. ScaleLLM: A Resource-Frugal LLM Serving Framework by Optimizing End-to-End Efficiency. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2408.00008. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Bansal, H.; Xia, T.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Hajishirzi, H.; Cheng, H.; Chang, K.W.; Galley, M.; Gao, J. Mathvista: Evaluating mathematical reasoning of foundation models in visual contexts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.02255. [Google Scholar]

- Javaheripi, M.; Bubeck, S.; Abdin, M.; Aneja, J.; Bubeck, S.; Mendes, C.C.T.; Chen, W.; Del Giorno, A.; Eldan, R.; Gopi, S.; et al. Phi-2: The surprising power of small language models. Microsoft Research Blog 2023, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09685, arXiv:2106.09685 2021.

- Li, J.; Han, B.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Li, J. CoLLM: A Collaborative LLM Inference Framework for Resource-Constrained Devices. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CIC International Conference on Communications in China (ICCC). IEEE, 2024, pp. 185–190.

- Lee, T.; Tu, H.; Wong, C.H.; Zheng, W.; Zhou, Y.; Mai, Y.; Roberts, J.; Yasunaga, M.; Yao, H.; Xie, C.; et al. Vhelm: A holistic evaluation of vision language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 140632–140666. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Liu, J.; Huang, H.; Qiao, C.; Zhao, Y. Resource-efficient federated learning with hierarchical aggregation in edge computing. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2021-IEEE conference on computer communications. IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–10.

- Ben Melech Stan, G.; Aflalo, E.; Rohekar, R.Y.; Bhiwandiwalla, A.; Tseng, S.Y.; Olson, M.L.; Gurwicz, Y.; Wu, C.; Duan, N.; Lal, V. LVLM-Intrepret: An Interpretability Tool for Large Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 8182–8187.

- Shi, S.; Chu, X.; Cheung, K.C.; See, S. Understanding top-k sparsification in distributed deep learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.08772. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Chen, Y. Generative AI for Synthetic Data Generation: Methods, Challenges and the Future. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.04190. [Google Scholar]

- Rafailov, R.; Sharma, A.; Mitchell, E.; Manning, C.D.; Ermon, S.; Finn, C. Direct preference optimization: Your language model is secretly a reward model. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, D.; Wang, J. ALISA: Accelerating Large Language Model Inference via Sparsity-Aware KV Caching. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.17312. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ning, J.; Ye, H.J.; Zhan, D.C.; Liu, Z. Learning without forgetting for vision-language models. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, M.; Hu, H.; Myers, V.; Karamcheti, S.; Dragan, A.; Sadigh, D. Toward grounded commonsense reasoning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 5463–5470.

- The, L.; Barrault, L.; Duquenne, P.A.; Elbayad, M.; Kozhevnikov, A.; Alastruey, B.; Andrews, P.; Coria, M.; Couairon, G.; Costa-jussà, M.R.; et al. Large Concept Models: Language Modeling in a Sentence Representation Space. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.08821. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Chhaparia, R.; Douillard, A.; Kale, S.; Rusu, A.A.; Shen, J.; Szlam, A.; Ranzato, M. Asynchronous Local-SGD Training for Language Modeling. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09135. [Google Scholar]

- Kombrink, S.; Mikolov, T.; Karafiát, M.; Burget, L. Recurrent Neural Network Based Language Modeling in Meeting Recognition. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, 2011, Vol. 11, pp. 2877–2880.

- Sergeev, A.; Del Balso, M. Horovod: fast and easy distributed deep learning in TensorFlow. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.05799. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.; Ma, Y.; Cao, X.; Ye, W.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, K.; Chen, J.; Lu, J.; Yang, Z.; Liao, K.D.; et al. A survey on multimodal large language models for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2024, pp. 958–979.

- Minaee, S.; Mikolov, T.; Nikzad, N.; Chenaghlu, M.; Socher, R.; Amatriain, X.; Gao, J. Large language models: A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.06196. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeepa, S.; Kavinda, K.; Hashika, E.; Sandeepa, C.; Gamage, T.; Liyanage, M. DisLLM: Distributed LLMs for Privacy Assurance in Resource-Constrained Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–9.

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I.; et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, H.B.; Moore, E.; et al. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.05629. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, T.; Yatskar, M.; Ordonez, V.; Chang, K.W. Men also like shopping: Reducing gender bias amplification using corpus-level constraints. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.09457. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, J.; Bae, S.; Park, K.; Canini, M.; Hwang, C. Immediate Communication for Distributed AI Tasks. The 2nd Workshop on Hot Topics in System Infrastructure 2024.

- Huang, K.; Yin, H.; Huang, H.; Gao, W. Towards Green AI in Fine-tuning Large Language Models via Adaptive Backpropagation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.13192 2023. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.13192. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, X.; Chen, Q.; Gao, C.; Huang, W. Fedbone: Towards large-scale federated multi-task learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.17465 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.; Ghemawat, S. MapReduce: simplified data processing on large clusters. Communications of the ACM 2008, 51, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahia, O.; Kumar, S.; Gonen, H.; Hoffman, V.; Limisiewicz, T.; Tsvetkov, Y.; Smith, N.A. MAGNET: Improving the Multilingual Fairness of Language Models with Adaptive Gradient-Based Tokenization. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2407.08818. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R.; Oh, T.H.; Grauman, K.; Torresani, L. Listen to look: Action recognition by previewing audio. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 10457–10467.

- Wu, W.; Sun, Z.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Ouyang, W. Transferring vision-language models for visual recognition: A classifier perspective. International Journal of Computer Vision 2024, 132, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanghe, P.; Jun, C.; Linjun, D.; Xiaobo, Z.; Hongyan, Z. Cloud-Edge Collaborative Large Model Services: Challenges and Solutions. IEEE Network 2024.

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S. Blip: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training for unified vision-language understanding and generation. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2022, pp. 12888–12900.

- Pisarchyk, Y.; Lee, J. Efficient memory management for deep neural net inference. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.03288. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ma, S.; Dong, L.; Huang, S.; Wang, H.; Ma, L.; Yang, F.; Wang, R.; Wu, Y.; Wei, F. Bitnet: Scaling 1-bit transformers for large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.11453. [Google Scholar]

- Christiano, P.F.; Leike, J.; Brown, T.B.; Martic, M.; Legg, S.; Amodei, D. Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017, pp. 4299–4307.

- Bitton Guetta, N.; Slobodkin, A.; Maimon, A.; Habba, E.; Rassin, R.; Bitton, Y.; Szpektor, I.; Globerson, A.; Elovici, Y. Visual riddles: A commonsense and world knowledge challenge for large vision and language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 139561–139588. [Google Scholar]

- Biderman, S.; Schoelkopf, H.; Anthony, Q.G.; Bradley, H.; O’Brien, K.; Hallahan, E.; Khan, M.A.; Purohit, S.; Prashanth, U.S.; Raff, E.; et al. Pythia: A suite for analyzing large language models across training and scaling. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 2397–2430.

- Wu, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Zhao, P.; Liu, Z. CG-FedLLM: How to Compress Gradients in Federated Fune-tuning for Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.13746. [Google Scholar]

- Rasley, J.; Rajbhandari, S.; Ruwase, O.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y. Deepspeed: System optimizations enable training deep learning models with over 100 billion parameters. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.00072. [Google Scholar]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024. [CrossRef]

- Laurençon, H.; Tronchon, L.; Cord, M.; Sanh, V. What matters when building vision-language models? Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 87874–87907. [Google Scholar]

- Denton, E.L.; Zaremba, W.; Bruna, J.; LeCun, Y.; Fergus, R. Exploiting linear structure within convolutional networks for efficient evaluation. Advances in neural information processing systems 2014, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, S.; Qin, F.; Wang, Y. DISTMM: Accelerating Distributed Multimodal Model Training. In Proceedings of the 21st USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 24), 2024, pp. 1157–1171.

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Tang, J.; Wu, J.; Gao, J.; Wang, J. BinaryBERT: Pushing the limit of BERT quantization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2020, pp. 4334–4343.

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Qiu, W.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, Z. Safely Learning with Private Data: A Federated Learning Framework for Large Language Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.14898. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Yang, M.; Qu, X.; Zhou, P.; Cheng, Y.; Hu, W. A survey of attacks on large vision-language models: Resources, advances, and future trends. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.07403. [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek, F. Statistical methods for speech recognition; MIT press, 1998.

- Zhu, K.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Xie, C.; Wu, F.; Xie, R. An Energy-Efficient Dynamic Offloading Algorithm for Edge Computing Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2024. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Hu, R.; Goswami, V.; Couairon, G.; Galuba, W.; Rohrbach, M.; Kiela, D. Flava: A foundational language and vision alignment model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 15638–15650.

- Tan, A.Z.; Yu, H.; Cui, L.; Yang, Q. Towards personalized federated learning. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2022, 34, 9587–9603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.; Kudinov, M.; Piontkovskaya, I.; Vytovtov, P.; Nevidomsky, A. Distributed fine-tuning of language models on private data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2018.

- Youyang, Q.; Jinwen, Z.; Qi, C. Federated Learning driven Large Language Models for Swarm Intelligence: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.09831. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Cai, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, S.; Zhou, A. FedRDMA: Communication-Efficient Cross-Silo Federated LLM via Chunked RDMA Transmission. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Machine Learning and Systems, 2024, pp. 126–133.

- Fan, T.; Kang, Y.; Ma, G.; Chen, W.; Wei, W.; Fan, L.; Yang, Q. Fate-LLM: A industrial grade federated learning framework for large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.10049. [Google Scholar]

- Shenghui, L.; Wei, L.; Lin, W. Synergizing Foundation Models and Federated Learning: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.12844. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Yu, H.; Song, X.; Liu, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, D. Mobilebert: a compact task-agnostic bert for resource-limited devices. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.02984. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, C.V.; Shen, X.; Aponte, R.; Xia, Y.; et al. A Survey of Small Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.20011. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Shao, R.; Xie, A.; Xing, E.P.; Ma, X.; Stoica, I.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Zhang, H. DISTFLASHATTN: Distributed Memory-efficient Attention for Long-context LLMs Training. In Proceedings of the First Conference on Language Modeling, 2024.

- Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Agarwal, S.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14165 2020, 1. arXiv:2005.14165 2020, 1.

- Rui, Y.; Jingyi, C.; Dihan, L.; Wenhao, W.; Yaxin, D.; Yanfeng, W.; Siheng, C. FedLLM-Bench: Realistic Benchmarks for Federated Learning of Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.04845. [Google Scholar]

- Markov, I.; Vladu, A.; Guo, Q.; Alistarh, D. Quantized distributed training of large models with convergence guarantees. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 24020–24044.

- Zhang, M.; Arora, S.; Chalamala, R.; Wu, A.; Spector, B.; Singhal, A.; Ramesh, K.; Ré, C. LoLCATs: On Low-Rank Linearizing of Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.10254. [Google Scholar]

- Borzunov, A.; Baranchuk, D.; Dettmers, T.; Ryabinin, M.; Belkada, Y.; Chumachenko, A.; Samygin, P.; Raffel, C. Petals: Collaborative inference and fine-tuning of large models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.01188. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Lee, M.; Jajoo, A.; Kim, G.W.; Xu, H.; Akella, A. Blockllm: Multi-tenant finer-grained serving for large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.18322. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Yu, T.; Zhang, A.; Wang, C.; Cui, J.; Zhu, H.; Cai, T.; Li, H.; Zhao, W.; He, Z.; et al. MiniCPM-V: A GPT-4V Level MLLM on Your Phone. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.01800. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, T.; Huang, H.; Ning, X.; Zhang, G.; Chen, B.; Wu, T.; Wang, H.; Huang, Z.; Li, S.; Yan, S.; et al. Moa: Mixture of sparse attention for automatic large language model compression. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.14909. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Guo, Q.; He, W.; Ji, W. PerLLM: Personalized Inference Scheduling with Edge-Cloud Collaboration for Diverse LLM Services. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14636. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Xu, G.; Chen, F.; Yuan, Y.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, M.; Lu, J.; Yu, D. Unity is Power: Semi-Asynchronous Collaborative Training of Large-Scale Models with Structured Pruning in Resource-Limited Clients. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.08457. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.S.; Ali, M.; Bhatti, D.M.S.; Choi, B.J. dy-TACFL: Dynamic Temporal Adaptive Clustered Federated Learning for Heterogeneous Clients. Electronics 2025, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanie, S.; Nagrani, A.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Emotion recognition in speech using cross-modal transfer in the wild. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th ACM international conference on Multimedia, 2018, pp. 292–301.

- Bai, J.; Chen, D.; Qian, B.; Yao, L.; Li, Y. Federated fine-tuning of large language models under heterogeneous language tasks and client resources. arXiv e-prints 2024, pp. arXiv–2402.

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Ré, C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00396. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Gong, R.; Jiang, S.; Qiu, L.; Huang, S.; Liang, X.; Zhu, S.C. Inter-GPS: Interpretable geometry problem solving with formal language and symbolic reasoning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.04165. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, W.; Wang, Q.; Gao, X.; Cai, Q.; Ling, Z. On-device language models: A comprehensive review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.00088. [Google Scholar]

| Strategy | Memory Efficiency | Communication Overhead | Sync Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Parallelism | High | High (All-reduce) | Per step |

| Tensor Parallelism | Moderate | Moderate (Slice gather) | Per layer |

| Pipeline Parallelism | High | Low (Stage buffer) | Per microbatch |

| Hybrid Parallelism | Optimal | Complex | Variable |

| Framework | Parallelism | Memory Optimization | Inference | Used In |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Megatron-LM | DP, TP, PP | Activation recompute | Yes | GPT-NeoX |

| DeepSpeed | DP, ZeRO (1–3), PP | 8-bit Opt [39]. | Yes | BLOOM |

| FSDP (PyTorch) | DP (sharded weights) | sharding | Partial | Meta OPT-66B |

| Colossal-AI | DP, TP, MoE | Low-rank compression | Yes | OpenBMB |

| Model | Modalities | Fusion Method | Pretraining Objective | Scale (Params) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLIP | Image + Text | Contrastive (Late) | Contrastive Learning | 400M |

| Flamingo | Image + Text | Cross-Attention (Late) | Language Modeling | 80B |

| PaLI-X | Image + Text | Unified Transformer | Multitask (VQA, OCR) | 55B |

| GPT-4V | Image + Text | Interleaved Token Stream | Causal LM | 100B+ (est.) |

| GIT | Image + Text | Early Fusion | Captioning (Supervised) | 345M |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).