1. Introduction

The increasing integration of embedded systems and IoT devices within cyber-physical systems (CPSs) has led to growing concerns regarding cybersecurity threats. Among these, side-channel attacks (SCAs) pose a significant challenge as they exploit unintended information leakage such as power consumption, electromagnetic emissions, and execution timing to extract sensitive cryptographic data [

1,

2]. While various countermeasures such as hiding and masking techniques have been developed to mitigate these threats, recent advancements in deep learning have exposed their potential vulnerabilities [

3]. Traditional hiding techniques aim to obfuscate power consumption patterns, making it difficult for attackers to extract meaningful information. However, machine learning models, particularly deep learning architectures, have shown a remarkable ability to differentiate between authentic cryptographic executions and those obfuscated by dummy power trace data, potentially rendering conventional hiding methods ineffective [

4].

This research systematically evaluates the limitations of existing hiding techniques when confronted with deep learning-based SCAs. Unlike traditional methods that rely on heuristic defenses, our study employs a controlled simulation environment to generate side-channel datasets and rigorously assess their resilience against machine learning-based attacks. Through extensive experiments, we demonstrate that deep learning classifiers can successfully identify patterns in dummy traces, significantly reducing their effectiveness as a countermeasure.

Our contributions are threefold. First, we propose a novel framework for generating and evaluating dummy power traces in a virtualized environment, ensuring reproducibility and cost-effectiveness. Second, we provide an empirical analysis of RNN, Bi-RNN, and MLP models, highlighting their capability to bypass traditional countermeasures. Third, we offer insights into enhancing cryptographic defenses by exploring potential counterstrategies, such as adversarial machine learning and adaptive obfuscation techniques.

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of SCAs and existing cryptographic defenses.

Section 3 presents the methodology for dataset generation and deep learning evaluation.

Section 4 discusses the experimental results, demonstrating the vulnerabilities of conventional hiding techniques. Finally,

Section 5 concludes with a discussion on the broader implications of our findings and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Side-Channel Attacks

SCAs exploit unintended information leakage from cryptographic implementations [

5,

6]. These attacks target physical characteristics of devices, such as power consumption, electromagnetic radiation, and timing variations, to extract cryptographic keys and other sensitive information. Unlike traditional cryptographic attacks that focus on breaking mathematical structures, SCAs take advantage of vulnerabilities in the physical execution of cryptographic algorithms.

Among the various SCA techniques, power analysis attacks, including Simple Power Analysis (SPA) and Differential Power Analysis (DPA), have proven to be particularly effective [

7,

8]. SPA relies on direct observation of power consumption patterns, while DPA employs statistical analysis to extract information from multiple power traces. Electromagnetic analysis and fault injection attacks further expand the range of SCAs, enabling adversaries to compromise cryptographic implementations with minimal access to the target system [

9].

Advancements in machine learning and deep learning have further elevated the risk posed by SCAs. Modern neural networks can process vast amounts of side-channel data, learning intricate patterns that allow attackers to derive cryptographic keys with higher efficiency than traditional statistical methods. The ability of deep learning models to generalize across different devices and encryption schemes presents an urgent need for robust and adaptive countermeasures against SCAs.

Figure 1 presents the time-sequenced attack and defense perspectives in an SCA scenario. The attacker first collects power traces from cryptographic operations and trains a deep learning model to extract cryptographic keys. To counteract this, the defender employs a combination of techniques, starting with dummy data generation to introduce noise, followed by hiding and masking strategies, and finally applying dynamic power management to further obfuscate the power consumption patterns. The final outcome ensures that key extraction attempts fail, securing the system from deep learning-based SCAs.

2.2. Countermeasures Against SCAs

To mitigate the risks posed by SCAs, several countermeasures have been developed. Hiding techniques attempt to randomize power consumption patterns by introducing noise or varying execution sequences, making it harder for attackers to extract meaningful information. Blinding methods involve mathematically altering cryptographic computations to obscure correlations between intermediate values and final results. Masking techniques introduce random values during encryption processes to prevent attackers from deriving sensitive data through statistical analysis [

10]. Despite their effectiveness, these countermeasures are increasingly challenged by deep learning-based SCA methodologies, which can adapt to and learn from complex data patterns, bypassing traditional security measures [

11,

12].

Recent studies have proposed hybrid countermeasures that combine multiple defensive techniques to improve resistance against deep learning-based SCAs [

13]. For example, dynamic power management, randomized instruction execution, and noise injection are being explored as complementary approaches to traditional hiding and masking techniques. The effectiveness of these combined countermeasures depends on implementation efficiency, resource overhead, and adaptability to evolving attack methodologies.

Table 1 presents an overview of countermeasures used against SCAs, categorizing them based on their primary defense mechanisms. These methods aim to either obscure power consumption patterns, introduce mathematical transformations, or combine multiple techniques to enhance resistance to deep learning-based attacks.

2.3. ELMO

One of the key tools for analyzing SCAs is the ELMO simulator, an open-source framework designed for power consumption modeling in embedded systems. ELMO allows researchers to simulate the effects of different cryptographic implementations, enabling precise measurement and evaluation of potential vulnerabilities [

6]. By leveraging such tools, researchers can develop and assess novel countermeasures against SCAs in a controlled environment.

Additionally, ELMO uses instruction flow analysis to predict power consumption cycles, providing insights into the power signatures of cryptographic operations [

14]. It categorizes assembly instructions into different groups, such as arithmetic logic unit (ALU) operations, load/store operations, and shift operations, which helps refine the accuracy of power analysis predictions.

Recent updates to ELMO have incorporated machine learning-based analysis, enhancing its ability to simulate real-world attacks [

15]. The integration of AI-driven predictive models into SCA research has allowed for more effective assessment of countermeasures and attack techniques. Researchers are now utilizing these advanced simulation tools to refine cryptographic implementations and develop adaptive defenses against evolving threats [

16].

Table 2 presents the classification of assembly instructions used in ELMO for power analysis. By categorizing instructions into arithmetic, shift, load/store, and multiplication operations, ELMO enables researchers to analyze the energy consumption patterns of cryptographic implementations more effectively.

As deep learning techniques continue to evolve, they present both challenges and opportunities in the field of cryptographic security. On one hand, machine learning models enhance the ability of attackers to conduct sophisticated SCAs, but on the other, they also provide avenues for developing more resilient countermeasures. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for advancing the security of cryptographic systems and ensuring robust protection against emerging threats.

3. Method of Generating Dummy Power Trace Data

This study proposes a systematic approach to generating dummy power trace data that closely resembles actual cryptographic power consumption patterns. By leveraging a controlled simulation environment, we aim to analyze and evaluate the effectiveness of dummy power traces in mitigating side-channel attacks. The process involves simulating cryptographic algorithm execution, extracting assembly-level instructions, and converting them into power trace data.

3.1. Simulation Environment Setup

To generate realistic dummy power traces, we construct a simulation environment based on QEMU and GDB, enabling precise extraction of execution-level data from cryptographic implementations [

14]. QEMU (Quick Emulator) is an open-source virtualization tool that emulates hardware architectures, allowing embedded system code to be executed in a controlled environment without physical hardware. GDB (GNU Debugger) is a widely used tool for debugging programs, enabling step-by-step execution analysis and real-time extraction of assembly instructions [

17].

The process of dummy power trace generation consists of three main stages: cryptographic code execution (Stage 1), processing via emulation and debugging (Stage 2), and extraction of assembly data followed by power trace conversion (Stage 3), as illustrated in

Figure 2. In Stage 1 (Input), cryptographic code written in assembly is executed within a simulated environment. The code is transferred to QEMU, a virtualized execution platform, where it undergoes controlled execution. In Stage 2 (Processing), QEMU functions as an ARM Cortex-M4 virtual machine, executing cryptographic operations while GDB is utilized for debugging [

17]. Through this debugging interface, assembly-level instructions are extracted in real time, enabling precise tracking of command execution and memory access patterns. Finally, in Stage 3 (Output), the extracted assembly data—comprising memory addresses, instruction sequences, and operand values—is processed using the ELMO simulator. This conversion generates power consumption patterns, which are then analyzed for potential vulnerabilities to side-channel attacks [

15].

This structured approach ensures a reproducible and controlled method for assessing cryptographic security against deep learning-based SCAs.

To demonstrate the execution of this simulation environment,

Figure 3 presents the actual QEMU setup and debugging output. This environment emulates an STM32F4 Discovery board, enabling the execution of cryptographic functions while providing detailed memory allocations and debugging information. The log output displays the initialization process of QEMU, system memory allocations, and GDB interactions, confirming the successful execution of cryptographic operations within the simulation setup.

3.2. Assembly Instruction Extraction

After executing cryptographic operations within the QEMU-based simulation environment, the next step involves extracting assembly-level instructions for each execution cycle. These instructions contain key details regarding the computational sequences being performed [

18]. The extracted data includes memory addresses where instructions are stored, the types of instructions being executed, and the corresponding operand values manipulated during execution. Extracting this information is critical because each instruction contributes differently to power consumption, which is later analyzed in SCAs [

15].

To retrieve these instructions, GDB is utilized to monitor and capture executed commands in real-time. This enables precise tracking of how cryptographic algorithms operate at the machine level, helping to identify which instructions might be susceptible to power analysis. The debugging interface of GDB provides a structured format where assembly instructions, memory access patterns, and register manipulations are recorded.

Table 3 presents an example of extracted assembly data obtained through GDB debugging. The extracted instructions include memory addresses, executed instruction types, and operand values stored in registers. This dataset serves as a representative example of how cryptographic operations are executed at the machine level and is crucial for power trace generation.

The extracted assembly data is then used to generate power traces through the ELMO simulator. Each instruction contributes to a unique power consumption pattern based on factors such as the number of bits changed in a register or memory operation complexity. By mapping these execution patterns to power traces, we can assess how deep learning models identify cryptographic operations and evaluate the vulnerability of existing countermeasures.

3.3. Converting Assembly Instructions to Power Trace Data

After extracting the assembly-level execution data from the QEMU-based simulation environment, the next step involves converting this data into power trace data using the ELMO simulator [

19]. ELMO (Embedded Leakage Model) is a widely used tool for modeling power consumption in cryptographic implementations. It estimates power consumption based on instruction-level characteristics and register interactions, providing a realistic power trace that represents the execution of cryptographic algorithms [

20].

The power trace conversion follows a mathematical model, where the power consumption

y is expressed as formula (1).

In this formula, represents the scalar intercept, which serves as the baseline power consumption level. The coefficients and capture the influence of the previous and next instructions, respectively, on power consumption. These coefficients are determined based on predefined instruction categories such as ALU operations, load/store, and shift operations. The operand-related values, represented by , consist of the set [|||], which encodes 128-bit operands and their interactions during execution. A crucial component in this model is , which is assigned a binary matrix value corresponding to the operand of the -th instruction in the execution sequence. The value of is calculated using an XOR operation between the current operand bit matrix and the previously assigned operand matrix. For instance, if the current operand matrix is ‘0101’ and the previous operand matrix is ‘1100’, the XOR operation results in ‘1001’ as the assigned value. Another key factor, , represents the Hamming weight of the previous 32-bit operation and the Hamming distance between the last two operation values. These parameters significantly influence power consumption as they dictate the number of bit transitions occurring within registers. Finally, ϵ denotes an error vector that accounts for noise in power consumption measurements, while β is a coefficient vector determined based on ELMO’s calibrated power model parameters.

By applying this model, the extracted assembly data is systematically converted into power traces that replicate real-world power consumption characteristics. These traces provide valuable insight into how cryptographic operations impact power consumption, allowing for an in-depth evaluation of their susceptibility to deep learning-based classification attacks.

4. Experimental Results

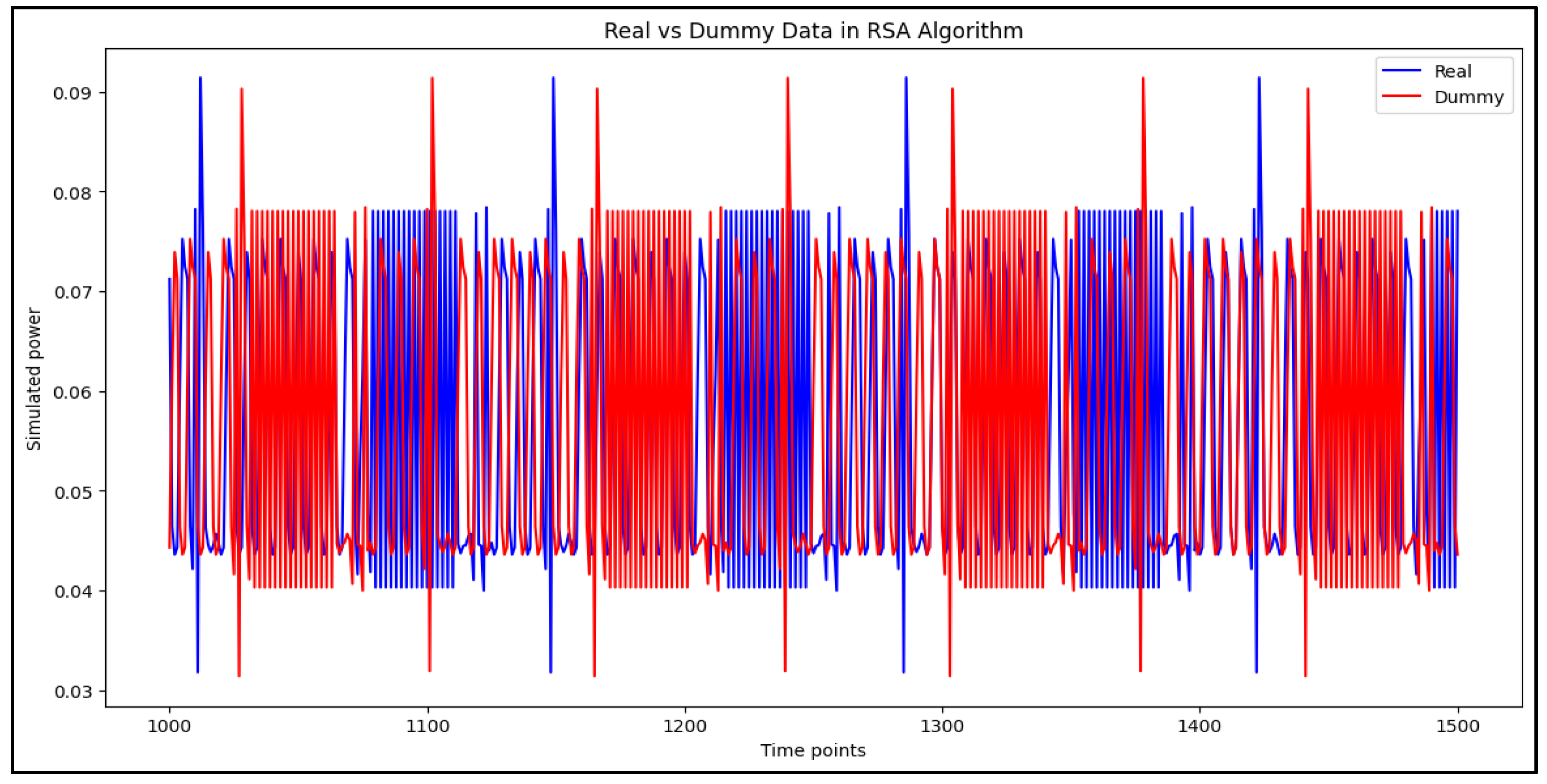

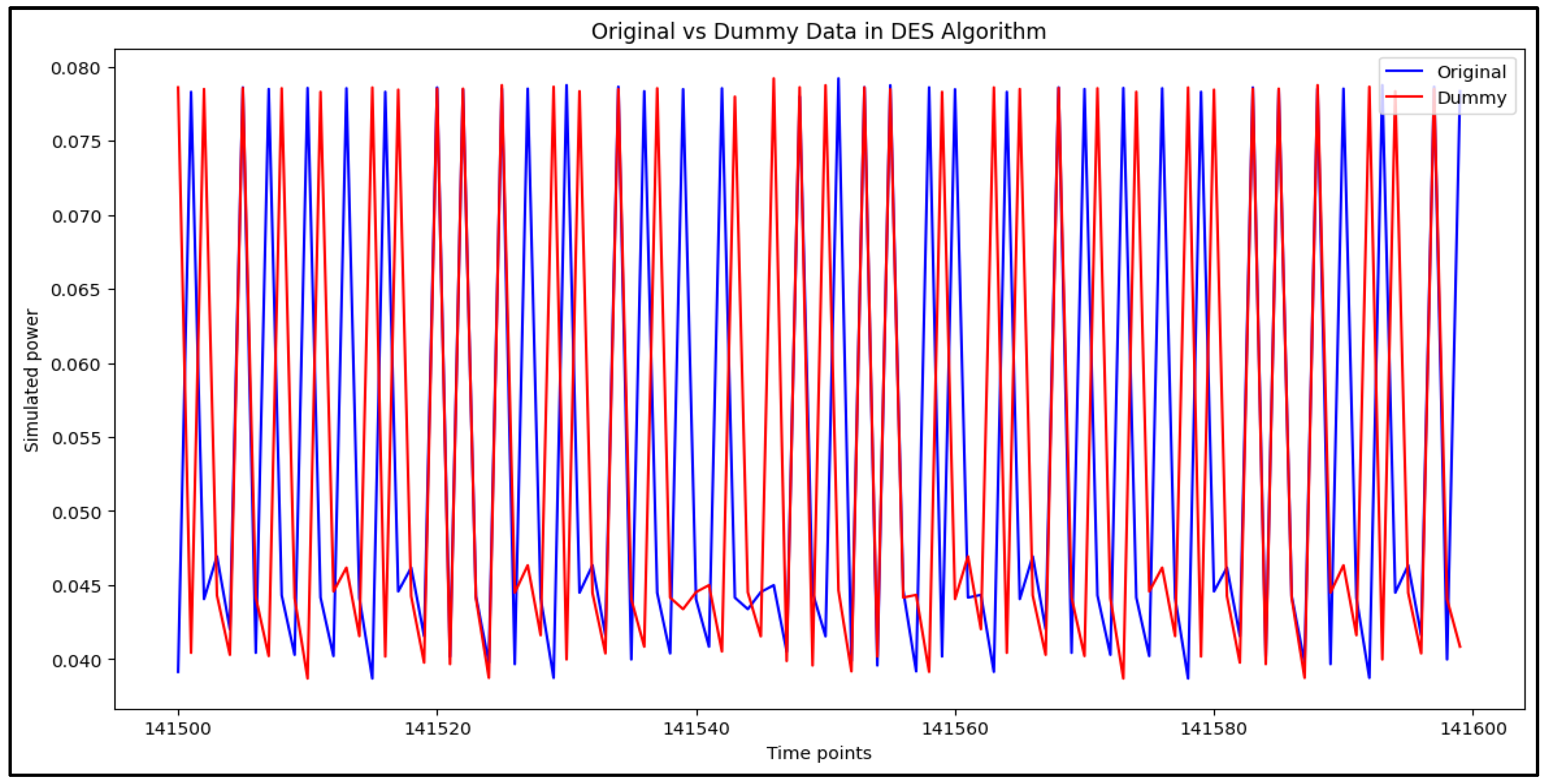

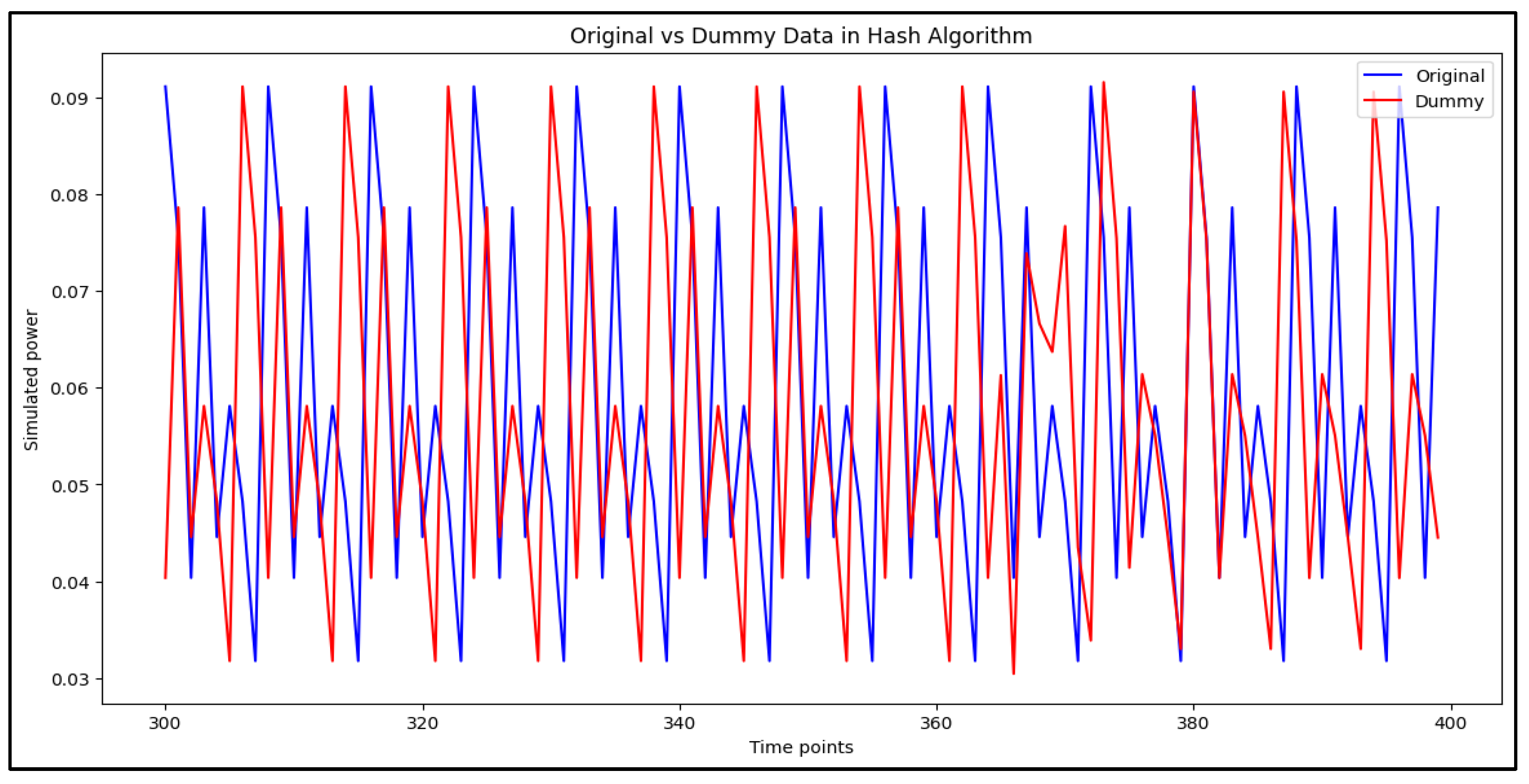

4.1. Data Generation & Preprocessing

To effectively analyze side-channel attacks on embedded systems, a dataset was generated using cryptographic algorithms, including RSA, DES, and Hash functions [

21]. The reason for selecting these algorithms in this study is that these algorithms are widely used in embedded systems and IoT environments and have been frequently targeted by recent side-channel attacks. In particular, RSA and DES are appropriate as representative examples, considering their cryptographic stability and usability in various industries [

5,

21]. The data collection was performed using a controlled simulation environment based on QEMU and GDB, allowing for the extraction of detailed assembly-level execution data.

The generated dataset underwent multiple stages of preprocessing to enhance its usability for deep learning models. Initially, the extracted instruction data was normalized to ensure consistency across different algorithm implementations [

19]. The dataset was then augmented by incorporating variations in memory access patterns and execution timing data, thereby capturing a more comprehensive representation of cryptographic behavior. This preprocessing step was crucial in facilitating robust model training and improving classification accuracy [

18].

The dataset was structured to maintain an equal distribution of original and dummy instructions, ensuring a balanced training set. This was essential for assessing the resilience of deep learning-based classifiers against side-channel attacks and validating the effectiveness of dummy power traces.

Table 4 presents the dataset distribution, highlighting the number of original and dummy instructions per cryptographic algorithm.

Maintaining such a balanced dataset was crucial for achieving realistic attack scenarios and assessing the effectiveness of countermeasures. Additionally, a thorough evaluation of instruction dependencies and opcode frequency distributions was conducted to identify potential biases in data generation, ensuring the robustness of the dataset used for classification tasks.

4.2. Model Training & Experimental Setup

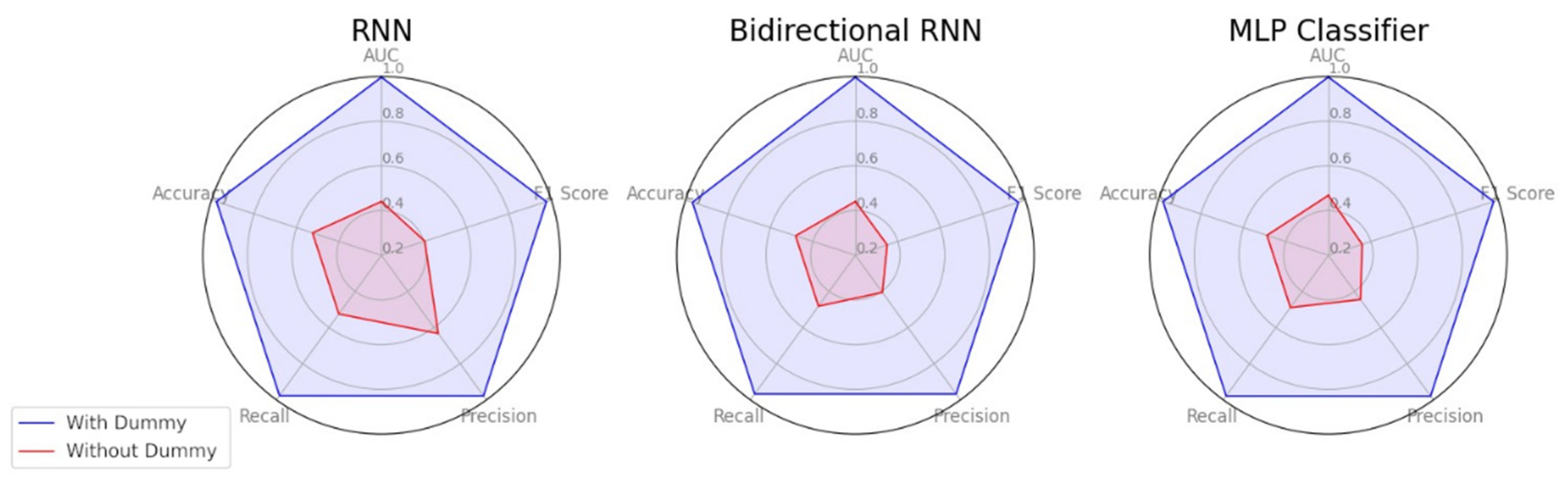

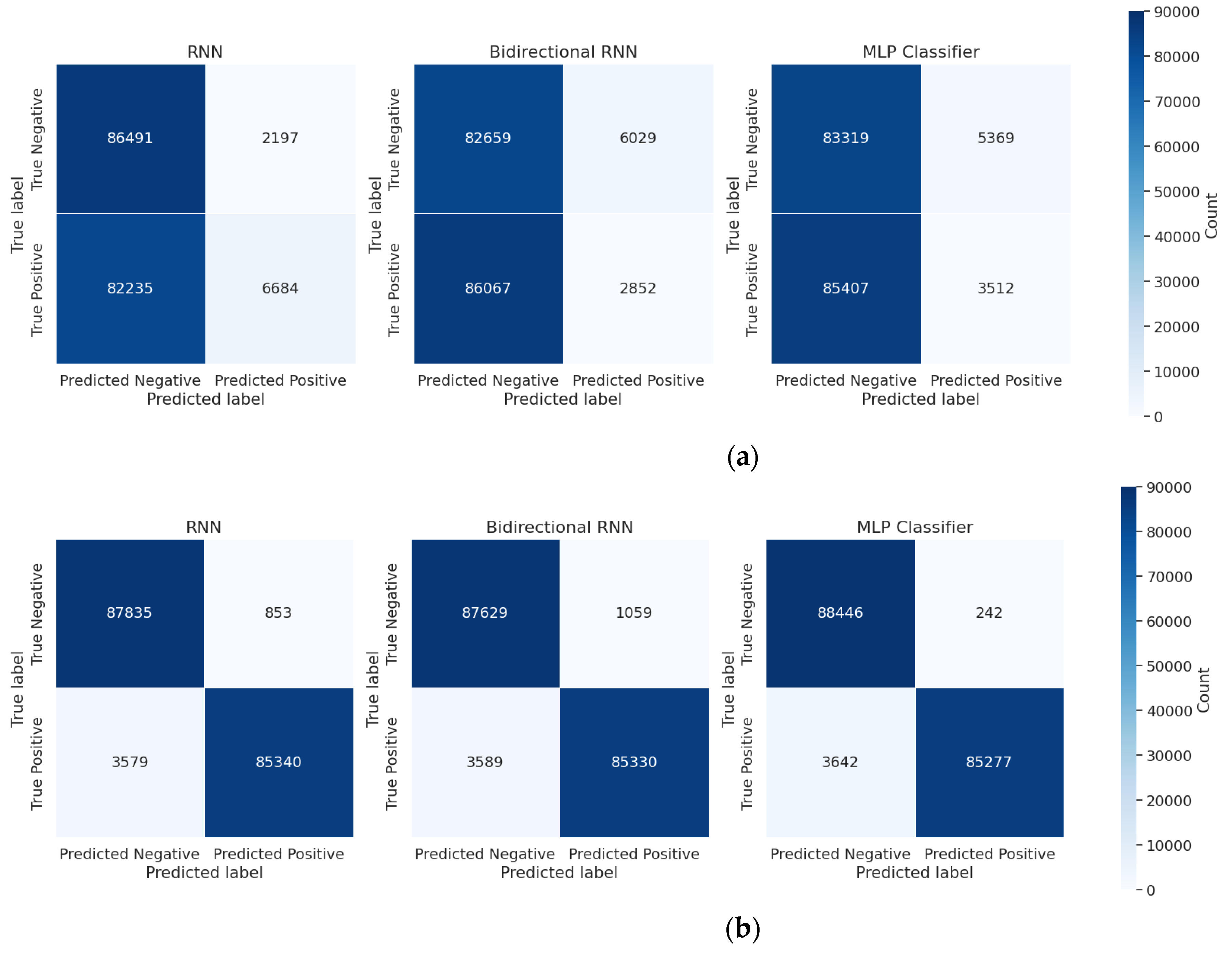

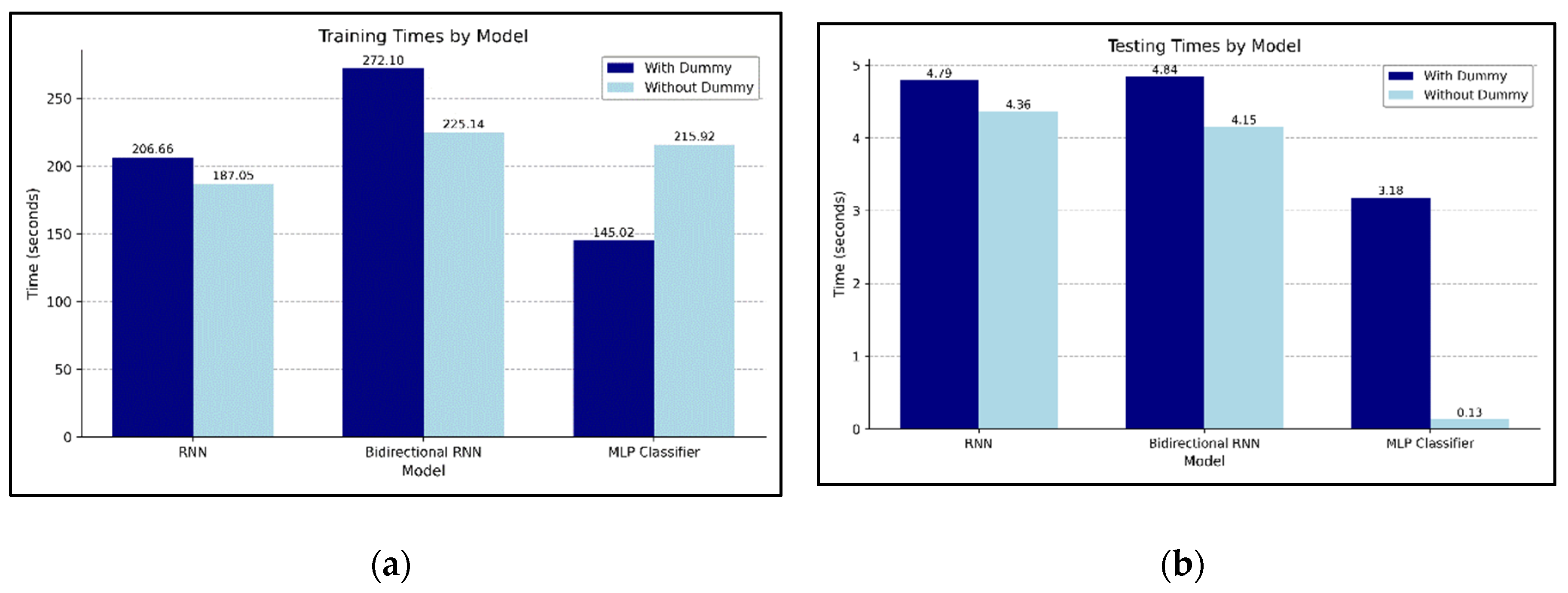

To evaluate the effectiveness of dummy power traces against side-channel attacks, deep learning models were trained and tested using the generated dataset. Three primary architectures were considered: Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Bidirectional RNNs (Bi-RNNs), and Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) [

16]. These models were selected due to their ability to capture sequential dependencies in power consumption patterns, making them particularly suitable for time-series classification tasks.

The dataset underwent preprocessing, including data normalization and augmentation to enhance model generalization. Controlled noise injection and jitter effects were applied to simulate real-world measurement variations. Training was conducted using a high-performance GPU to ensure efficient computation.

Each model was optimized using the Adam optimizer, with training parameters adjusted through iterative testing. To prevent overfitting, regularization techniques such as dropout and early stopping were applied. Performance evaluation was based on accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC, recorded at each epoch to track model improvements.

Figure 4 illustrates the accuracy progression during training, showing how each model converges over epochs. This figure provides insights into the training stability and comparative learning efficiency of different models. The results from

Figure 4 complement

Table 5, which presents final model performance metrics, by demonstrating how training progresses before achieving those final results.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the effectiveness of dummy power traces in mitigating side-channel attacks (SCAs) when analyzed using deep learning models. Our results indicate that while dummy traces introduce additional complexity, deep learning classifiers still differentiate between real and obfuscated traces with high accuracy, revealing the limitations of conventional hiding techniques. Through an extensive evaluation of RNN, Bi-RNN, and MLP models, we demonstrated that incorporating dummy traces improved classification accuracy, with an average F1-score of 97.65%.

Using a simulated environment based on QEMU and GDB, we successfully generated a large dataset of power traces, systematically incorporating dummy traces to analyze their impact on cryptographic security. The experimental results confirm that while dummy traces make side-channel analysis more challenging, they do not provide complete protection against deep learning-based attacks. These findings underscore the need for more robust countermeasures to enhance cryptographic security against evolving threats.

The key contributions of this study include the development of a novel framework for generating and evaluating dummy traces in a controlled environment, along with an empirical evaluation of the effectiveness and limitations of dummy-based hiding techniques against deep learning models. By leveraging deep learning techniques to assess the effectiveness of obfuscation strategies, this study lays the groundwork for developing improved security mechanisms resilient to AI-driven SCAs.

Future research should focus on applying adversarial machine learning techniques to enhance deep learning-based SCAs. Specifically, data filtering and robustness evaluation should be emphasized as key countermeasures against model confusion induced by data poisoning attacks [

11,

20]. Additionally, it is necessary to expand the research by evaluating the effects of measurement errors and noise, which are not present in simulation environments, through real hardware implementations, to improve the practical applicability of the research findings [

18].

As SCAs continue to evolve, cryptographic security mechanisms must advance in parallel. Based on the findings of this study, developers of embedded systems and IoT devices should move beyond static obfuscation strategies and consider adopting dynamic obfuscation techniques that modify patterns in real time or at regular intervals [

10]. Furthermore, it is recommended to establish a security framework that incorporates a real-time anomaly detection system for power consumption data to proactively detect and prevent potential attacks [

3].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., A.S., and Y.S.; methodology, S.P., A.S., M.C. and Y.S.; software, A.S., M.C. and H.K.; validation, S.P. and A.S.; formal analysis, A.S., M.C., J.K. and Y.S.; investigation, S.P., A.S. and M.C.; resources, S.P. and A.S.; data curation, A.S. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., A.S. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, S.P. and Y.S.; visualization, A.S. and M.C.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) under the Artificial Intelligence Convergence Innovation Human Resources Development (IITP-2025-RS-2023-00254592) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT). This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. 20224000000020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nguyen, D. H.; Seo, A.; Nnamdi, N. P.; Son, Y. False Alarm Reduction Method for Weakness Static Analysis Using BERT Model. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Jaouhari, S.; Bouvet, E. Secure firmware Over-The-Air updates for IoT: Survey, challenges, and discussions. Internet of Things 2022, 18, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Tyagi, A. Using Power Clues to Hack IoT Devices: The power side channel provides for instruction-level disassembly. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2017, 6, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, D.; Ma, Z.; Buttyan, L. Embedded systems security: Threats, vulnerabilities, and attack taxonomy. In 2015 13th Annual Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST), Izmir, Turkey, 3 September 2015; pp. 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Kolias, C.; Kambourakis, G.; Stavrou, A.; Voas, J. DDoS in the IoT: Mirai and Other Botnets. Computer 2017, 50, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Xu, X.; Jin, Y.; Forte, D.; Tehranipoor, M. Power-based Side-Channel Instruction-level Disassembler. In 2018 55th ACM/ESDA/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20 September 2018. [CrossRef]

- Alabdulwahab, S.; Kim, Y.-T.; Seo, A.; Son, Y. Generating Synthetic Dataset for ML-Based IDS Using CTGAN and Feature Selection to Protect Smart IoT Environments. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, P.; Jaffe, J.; Jun, B. Differential Power Analysis. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Cryptology Conference (CRYPTO 1999), Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 15–19 August 1999; pp. 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ou, Y. A deep learning-based side channel attack model for different block ciphers. J. Comput. Sci. 2023, 72, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.; Fu, X.; Xu, Z. A Secure Reconfigurable Crypto IC With Countermeasures Against SPA, DPA, and EMA. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Design Integr. Circuits Syst. 2015, 34, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissbart, L.; Picek, S.; Batina, L. One Trace Is All It Takes: Machine Learning-Based Side-Channel Attack on EdDSA. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Security, Privacy, and Applied Cryptography Engineering (SPACE 2019), Gandhinagar, India, 3-7 December 2019; pp. 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulwahab, S.; Cheong, M.; Seo, A.; Kim, Y.-T.; Son, Y. Enhancing deep learning-based side-channel analysis using feature engineering in a fully simulated IoT system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 266, 126079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangard, S.; Oswald, E.; Popp, T. Power Analysis Attacks: Revealing the Secrets of Smart Cards; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-387-30857-9. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, A.; Kim, Y.-T.; Yang, J. S.; Lee, Y.; Son, Y. Software Weakness Detection in Solidity Smart Contracts Using Control and Data Flow Analysis: A Novel Approach with Graph Neural Networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaish, N.; Khosla, C. Uniform debugging interface for simulators. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Advanced Informatics for Computing Research (ICAICR 2019), Shimla, India, 15-16 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brier, E.; Clavier, C.; Olivier, F. Correlation power analysis with a leakage model. In Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems (CHES 2004), Cambridge, MA, USA, 11–13 August 2004; pp. 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, D.; Ihm, S.-Y.; Lee, Y.; Son, Y. Multilateral Personal Portfolio Authentication System Based on Hyperledger Fabric. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, E.; Mateos, R.; Bueno, E. J.; Nieto, R. Enabling Parallelized-QEMU for Hardware/Software Co-Simulation Virtual Platforms. Electronics 2021, 10, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ihm, S.-Y.; Son, Y. Two-Level Blockchain System for Digital Crime Evidence Management. Sensors 2021, 21, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, D.; Oswald, E.; Whitnall, C. Towards Practical Tools for Side Channel Aware Software Engineering: ‘Grey Box’ Modelling for Instruction Leakages. In Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Conference on Security Symposium, Vancouver, Canada, 16-18 August 2017; pp. 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Su, N.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M. Research on Data Encryption Standard Based on AES Algorithm in Internet of Things Environment. In 2019 IEEE 3rd Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC), Chengdu, China, 15-17 March 2019; pp. 2071–2075. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).