1. Introduction

The Internet of Things is an interactive paradigm that links everyday objects by allowing for easy access and interaction with several devices. The integration of new network technologies with IoT has considerably expanded the danger landscape for NGN-IoT networks and applications (Taleb et al. 2017; Sood et al. 2021). It is crucial to recognize that IoT devices are easily compromised due to their limited resources and inability to execute advanced computational authentication procedures at the endpoint. Conventional security solutions rely on bit-level identifiable information, such as Message Authentication Code (MAC) addresses and network cryptographic keys (Wright et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2014). It is, however, possible to duplicate or alter MAC addresses and to generate cryptographic keys (Dini et al. 2010; Ezuma et al. 2020). Once attackers have the traditional credentials, then they can deploy malicious devices in a new-generation network already in operation and make use of them to launch a variety of attacks or to create botnets (Gope et al. 2022).

Conventional IoT authentication solutions primarily emphasize credentials and cryptographic mechanisms. In authentication-based systems, the access control paradigm grants users network access contingent upon established credentials, including usernames and passwords. Conversely, cryptographic techniques facilitate encrypted communication channels through hashing algorithms. Both categories of authentication methods encounter significant dangers (Dubey et al. 2023; Hussain et al. 2020). Due to resource limitations, IoT devices are unable to execute power-intensive encryption algorithms on end nodes. Adversaries can readily incapacitate networks, infiltrate IoT devices, and repurpose them into botnets. Also, in certain instances, traditional authentication methods are unable to stop impersonation threats entirely (Bera et al. 2022; Das et al. 2021), especially when credentials have been stolen or when authentication is based on a certificate. NGN networks possess distinct characteristics that do not entirely accommodate conventional methods for achieving optimal performance. For example, 5G makes real-time applications possible, so the time it takes to authenticate and verify which nodes are legitimate and which ones are illegitimate remains below a certain threshold; otherwise, there will be much delay in Figureuring out which nodes are legitimate (Sood et al. 2021; Alladi et al. 2021). The current security methods reliant on traffic data analysis are equally inadequate and insecure for NGNs (Gomez et al. 2022). Authentication reliant on traffic data analysis is inadequate to prevent impersonation attacks. Consequently, authentication for next-generation IoT devices continues to pose a challenge.

Deep learning is widely used in the field of speech and image recognition (Krizhevsky et al. 2017; Collobert et al. 2008) due to its ability to extract features better than other methods. Recently, researchers have applied deep learning to wireless communication, namely within Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access (NOMA) and hybrid precoding, Multiple-Input Multiple-Output (MIMO) as well as Internet of Things applications (Gui et al. 2018; Huang et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2018; Sun et al. 2019). One of the benefits of deep learning is the fact that it can efficiently and automatically identify high-level representations of features from complex datasets that are interconnected (LeCun et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2019). A detailed model of power amplifiers (PAs) and digital pre-distortion in RF transmitters was discussed using neural networks (Benvenuto et al. 1993; Mkadem et al. 2011). For passive radar signal recognition, an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) with a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) architecture was used to Figure out the carefully built parameters for both single pulses and multiple pulses (Willson et al. 1990). From the fluctuating amplitudes in Wi-Fi waveforms (Ureten et al. 2007), a Probabilistic Neural Network (PNN) was utilized to predict the amplitude of eight Wi-Fi cards to determine the feature vectors of the desired target manually. Automated feature extraction, the primary advantage of deep learning, is not yet mentioned in all the research papers mentioned above. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) could make it easier to train different machine learning models and make people more confident in the results these systems find. Using XAI in intrusion detection systems lets them explain how they make decisions in a way that is easy to understand.

While machine learning and deep learning offer several advantages in intrusion detection, existing models for IoT intrusion detection face significant challenges. Many ML-based IDS models require high computational resources, making them unsuitable for IoT devices with limited processing power. Traditional models often lack efficient feature selection, leading to redundant computations and suboptimal detection accuracy. These challenges highlight the urgent need for more efficient and effective models, such as the DL-IID model.

This study introduces the DL-IID model, an efficient, lightweight, and explainable deep learning-based IoT intrusion detection framework. Specifically designed to enhance IoT security, the DL-IID model addresses the computational, feature selection, and explainability challenges present in existing IDS solutions. The main contributions of this research are as follows:

A deep learning architecture that combines DNN and BiLSTM for capturing temporal dependencies that are present in both forward and backward directions, improving the detection of complex attack patterns in IoT networks.

Efficient feature selection using the Genetic Algorithm (GA) is applied following the extraction of features to select the most relevant features to reduce computational complexity while preserving the accuracy of the detection.

The bidirectional feature extraction and GA-based feature selection are two complementary processes, with the first focused on learning patterns and the latter optimizing the feature set to increase efficiency.

Integrating Explainable AI (XAI) using Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) to provide transparency in intrusion detection, increasing trust and ease of interpretation.

Lightweight model optimization using post-training dynamic quantization, reducing the model size to 108.42 KB while maintaining high detection accuracy (99.84%).

The comprehensive performance evaluation using an RF fingerprinting dataset demonstrates that DL-IID outperforms existing IDS solutions in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. This thorough evaluation provides reassurance about the effectiveness of the DL-IID model in securing IoT networks.

The proposed DL-IID model provides a flexible and effective solution to secure IoT networks. It offers a balance between high accuracy and low computation, which makes it suitable for implementation in IoT within the real world.

The remaining part of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 offers a comprehensive summary of earlier studies. In

Section 3, we offer an in-depth explanation of the methodology used for the proposed scheme. The results of the performance evaluation and discussions are outlined in

Section 4, whereas Section 5 provides the conclusion and future scope of this paper. A list of abbreviations used in the paper is presented in

Table 1.

2. Litrature Survey

The authentication techniques based on RF fingerprinting are a recognized area of study within wireless networks. Furthermore, approaches utilizing deep learning for the verification of node legitimacy have gained popularity recently. The main objective of the extraction of features is to derive information from radio frequency signals to create a distinct identity for the device. RF fingerprinting methods utilize a variety of RF features such as carrier frequency differences (CFDs), carrier frequency offset (CFOs), channel state information (CSI), discrete wavelet transform (DWT), in-phase and quadrature (I/Q) origin offset, magnitude and phase errors, phase shift differences, power amplifier characteristics, power spectral density (PSD), normalized PSD, radio signal strength (RSS), synchronization frame correlation, and instantaneous phase, amplitude, and frequency (Soltanieh et al. 2020; Guo et al. 2019). Most current studies focus on extracting RF features from RF transmitter signals.

Table 2 presents the literature on some of the related machine and deep learning techniques used for intrusion detection purposes.

Mirsky et al. (2018) introduced the widely recognized Kitsune solution. The suggested method aims to find the attack on its own, without any help from a monitoring system, and the autoencoding algorithm was employed to learn the normal pattern and analyze abnormal conditions. In their study, Chatterjee et al. (2019) employed an artificial neural network to create a distinctive signature utilizing radio frequency fingerprinting characteristics such as frequency offset and I-Q imbalance. The study recommends that RF signature features be adjusted and evaluated to reduce the impact of channel conditions. Tu et al. (2019) suggested a method that combines principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce the number of dimensions and SVMs for classification utilizing four features, and their method attains a detection accuracy exceeding 95%. For classifying ZigBee devices according to the features under the area of significance, Yu et al. (2019) devised an RF fingerprinting method. To evaluate performance, the authors conducted tests under both line-of-sight (LOS) and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) situations, using a multisampling convolutional neural network (MSCNN) to extract features and classification. The method attained a peak accuracy of 97% under LOS conditions.

The article by Aghnaiya et al. (2019) provides a radio frequency fingerprinting technique employing variational mode decomposition (VMD), exploiting Bluetooth transient data to extract High Order Statistical (HOS) features. In contrast, the study employs a Linear Support Vector Machine (LSVM) to classify Bluetooth devices. SLoRa (Wang et al. 2020) is a commonly employed radio frequency fingerprinting technique for IoT devices. This study introduces an authentication method utilizing RF fingerprinting, which identifies two features: CFO and link signatures. By including these features, it is possible to improve the efficiency of eliminating attacks that use impersonation. The SVM is used in the classification model, and adding CFO and link signatures makes identification more accurate.

The use of RF fingerprinting was demonstrated by Ezuma et al. (2020) for both Wi-Fi and Bluetooth systems. The goal of this study is to discover ways to recognize and classify unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). The study uses a two-step RF fingerprinting technique. First, a naive Bayes method based on the Markov model is used to extract radio frequency signals. Then, the K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) model is used to identify them. Experiments involving 15 distinct UAV types are conducted across various SNR levels to evaluate the method with the analysis of five distinct machine learning models. Jian et al. (2020) used a lightweight convolutional neural network (CNN) model to increase the efficiency of fingerprints in a classification framework impressively.

The region of interest (ROI) is used in the classification processes. Initially, the raw photos are preprocessed before regions of interest patterns are extracted from the images. The input data used by neural network classifiers is provided through the ROI pattern used in the analysis.

Zong et al. (2020) developed an approach by modifying the classic CNN model for frequency fingerprint detection of VGG-16. The results show that the accuracy is stable as epochs increase, culminating in a final accuracy of 99.7%. Li et al. (2020) utilized the robust KNN model to improve recognition performance by selecting the optimal subset from the generated features. Its robustness was evaluated across different SNR levels, with a maximum accuracy of 97.86%. This robustness provides a reassuring foundation for further research and application in the field. Bovenzi et al. (2020) proposed H2ID in a separate study to enhance the efficiency of the detection of attacks. It presents a two-stage approach for identifying attacks: the first stage involves anomaly

detection utilizing a lightweight Deep Autoencoder solution. In contrast, the second stage focuses on attack classification through open-set classification method.

Li and Cetin (2021) recently integrated the concept of RF fingerprinting with a technique that is based on deep learning within the waveform space. The identification of the device is achieved by the utilization of the waveform pictures obtained from the original sample, and it is recommended that dense neural networks be utilized for classification purposes. The method achieves around 99% accuracy when it comes to identification. The study evaluates the performance of the method across multiple scenarios that have differing SNR values and achieves a maximum accuracy of 95% in the optimal conFigureuration using the simple Nelder-Mead channel estimator to effectively lower the effect of noise on radio operation when Rayleigh fading is present (Fadul et al. 2021). Nguyen et al. (2023) propose an authentication method based on the Mahalanobis Distance with Chi-squared distribution theory in their paper. The method relies on the distinct RF signatures of IoT devices to distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate nodes. This study is among the first to utilize RF fingerprinting and distance-based techniques to authenticate 5G-IoT nodes. The framework is evaluated on the European Telecommunication Standards Institute (ETSI) open-source Network Functions Virtualization (NFV) platform offered by Amazon Web Service (AWS) to replicate real-world deployment scenarios.

Baldini et al. (2023) proposed a hybrid approach that combines convolutional neural networks (CNN) and feature selection techniques for intrusion detection on the Internet of Things. Their work focuses on improving the performance of detection by reducing the dimensionality of the model and improving the interpretability of the model. The study assesses several methods for selecting the most relevant attributes, resulting in better classification accuracy and reduced computational overhead. The experimental results show that the proposed CNN-based framework, combined with optimal selection of features, has superior performance in detection than traditional machine learning approaches. Recent research conducted by Turukmani et al. (2024) proposes the M-MultiSVM, which is a hybrid machine-learning framework designed for intrusion detection that addresses issues such as class imbalance and high-dimensional feature space. The approach includes preprocessing, advanced synthetic minority sampling techniques to mitigate class differences, and modified single-value decomposition (M-SvD) to ensure efficient feature extraction. The selection of features is optimized using an algorithm called the Northern Goshawk, which reduces dimensionality. For classification, a new multilayer SVM that supports mud rings combines SVM and MLP layers optimized by the mud ring optimization to increase the accuracy of the detection.

The study by Sadia et al. (2024) introduces a robust machine learning-based intrusion detection system for wireless sensor networks using the Aegean Wi-Fi Invasion Dataset (AWID). The authors employ a rigorous preprocessing process, including zero-value processing, structural engineering, and dimensional reduction, which reduces 154 elements to 13 critical attributes. They compare deep learning models such as convolutional neural networks, deep neural networks, and LSTMs for binary and multilayer attack classification. This paper underscores the robustness of CNNs in the extraction and recognition of patterns in WSN data, as validated by metrics such as accuracy, recall, and F1 score. Talukder et al. (2024) present a machine-learning approach to network intrusion detection that is robust and reliable, addressing the challenges of handling large and unbalanced data sets. Their model uses random over-sampling to reduce class imbalance, stacking of features (SFE) to extract meta-features, and principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality. The study highlights the importance of data mining and preprocessing techniques in improving the accuracy of detection, providing a robust solution for real-world cybersecurity applications.

The proposed DL-IID model stands out with several unique features. Unlike many previous studies, DL-IID leverages a genetic algorithm to select the best features, thereby reducing unnecessary computations. Post-training dynamic quantization is also applied, shrinking the model size to 108.42 KB while maintaining a high accuracy of 99.84%. This significant improvement over CNN-based and traditional ML approaches makes DL-IID a suitable choice for IoT devices with limited resources. Furthermore, the integration of LIME into the intrusion detection model enhances transparency and trust in security decisions.

3. Methodology

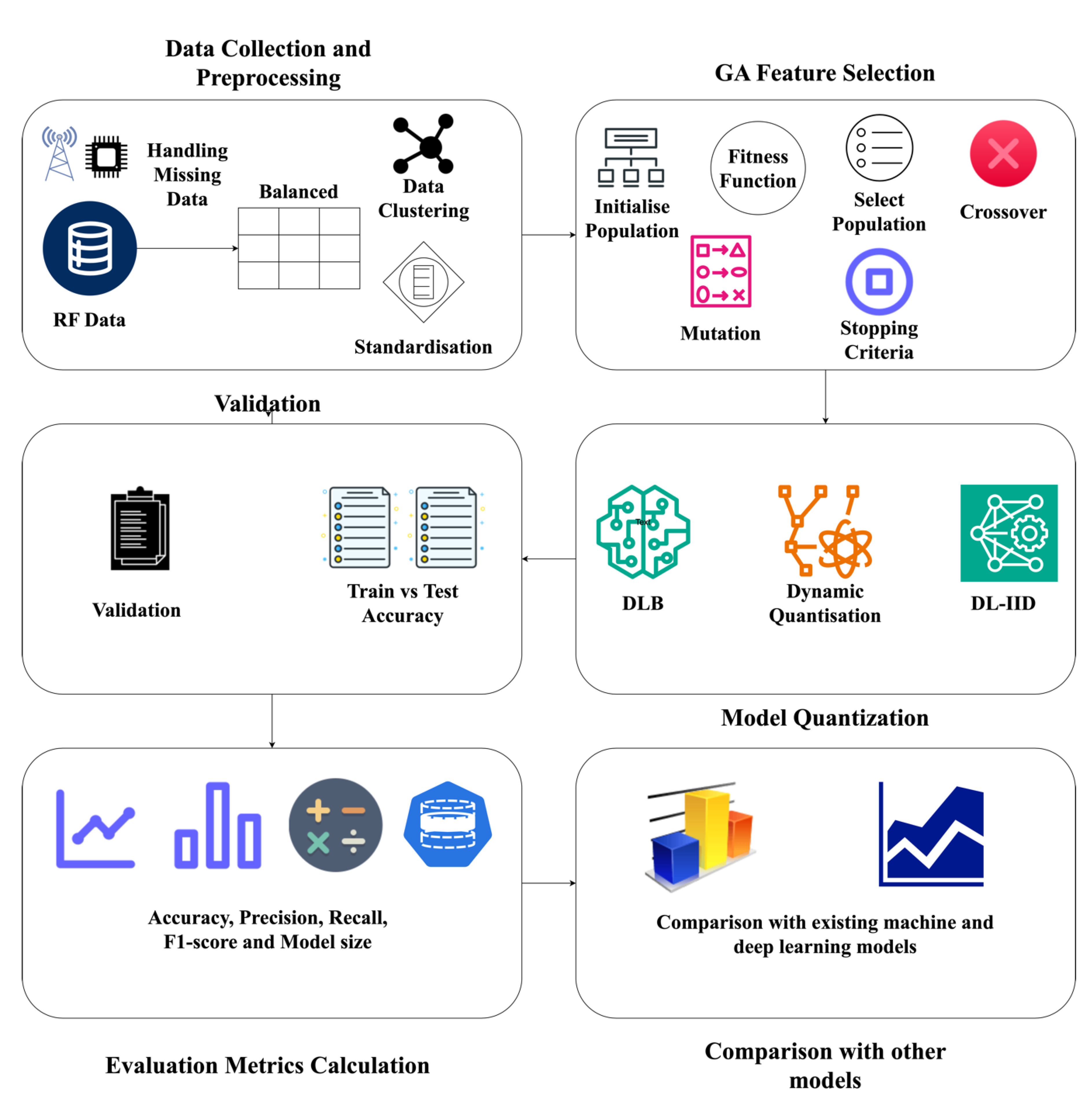

The overall framework of the proposed DL-IID method is presented in

Figure 1. The dataset that was used, data preprocessing methods, feature selection technique, use of XAI, and model quantization have all been covered. Many of the existing approaches for intrusion detection are based on limited machine learning methods. This is mainly a result of the resource constraints experienced by IoT devices in the deployment of intrusion detection systems. This research introduces an IoT intrusion detection system based on deep learning that employs an intrusion detection model, combining a dual hidden layer artificial (deep) neural network with bidirectional long short-term memory. The features derived from the utilization of GA are used to train the proposed DL-IID model. Algorithm 1 below shows a structured workflow for the DL-IID model, outlining feature selection, model training, quantization, and integration of LIME. The suggested model, with its high detection accuracy, provides a reassuring solution while maintaining minimal computational complexity.

| Algorithm 1 The workflow of the DL-IID Model |

Load Dataset

1. Load RF fingerprinting dataset (450 IoT devices, 100 samples/device).

2. Preprocess: Handle missing values (mean imputation), normalize (StandardScaler).

3. Apply K-Means clustering (K=2) to generate initial labels.

|

Feature Selection using Genetic Algorithm (GA)

1. Initialization:

Population size: 20 chromosomes (binary encoding).

Each chromosome: 7-bit string (1 = feature included, 0 = excluded).

2. Fitness Evaluation:

Train the DLB model on selected features.

Fitness score = (1 - classification error) + (1 – selected features / total features).

3. Selection: Tournament selection (size 2).

4. Crossover: Arithmetic crossover (probability = 0.8).

5. Mutation: Uniform mutation (probability = 0.05).

6. Stopping Criteria: 40 generations.

7. Output: Optimal feature subset.

|

Train DL-IID Model

1. Split data: 80% training, 20% testing.

2. Define DNN-BiLSTM architecture

3. Train the combined DNN–BiLSTM architecture using the selected features.

|

Post-Training Dynamic Quantization

1. Convert weights from float32 to int8.

2. Retain activation precision dynamically during inference.

|

Evaluate

1. Metrics: Accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, RMSE, MAPE.

2. Compare with baseline models.

|

Apply Explainable AI (LIME)

1. For test samples:

Generate perturbed instances around the sample.

Train local surrogate model.

Extract feature importance weights.

|

3.1. Details of Dataset Used

The datasets utilized in this study are widely recognized public datasets for intrusion detection experiments. Below, we describe the four data sets used by our intrusion detection model.

3.1.1. Radio Frequency (RF) Fingerprinting Dataset

The dataset was produced by the authors35 using the Wireless Waveform Generator toolbox in MATLAB. The 450 IoT devices are used to generate the dataset with varying RF characteristics in frequency, amplitude, and phase to replicate the non-idealities of RF characteristics. Each device generated 100 RF signal data points, utilizing RF features such as Carrier Frequency Offset (CFO), Amplitude Mismatch, Phase Offset, and other RF parameters, capturing device uniqueness in the experiments. While the dataset effectively simulates IoT device non-idealities, its primary limitation is controlled noise levels. In real-world IoT environments, RF signals may experience more dynamic variations, including interference from other networks, environmental noise affecting signal integrity, and real-time adversarial attacks.

3.1.2. CICIDS2017 Dataset

The CICIDS2017 dataset is a valuable resource as it contains benign and frequent attacks that closely resemble real-world data. It also contains network traffic analysis results from CICFlowMeter, a tool for accurate measurement of network traffic with time stamps, source and destination IP addresses, ports, protocols, and attacks. The data retention period started on Monday morning, 3 July 2017, and lasted for a total of five days, ending on Friday evening, 7 July 2017. Monday is a typical day and includes only light traffic. Among the attacks carried out are the Brute Force FTP, the Brute Force SSH, the DoS, the Heartbleed, the Web-based attack, the infiltration, the botnet, and the DDoS. On Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, they were executed both in the morning and the afternoon (Sharafaldin et al. 2018).

3.1.2. CIC IoMT 2024 Dataset

This dataset is of particular interest as it serves as a practical benchmark for the safety of internet-connected medical devices, i.e., the IoT. It contains 18 different cyber-attacks targeting 40 OTMs, providing a variety of protocols commonly used by medical devices, such as Wi-Fi, MQTT, and Bluetooth. The data collection process, which involved network tapping to capture traffic between the switch and IoMT-enabled devices for Wi-Fi and MQTT, has helped to create datasets for security and profiling. The use of the combination of a malicious PC and a smartphone to capture malicious and benign data for Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) enabled devices further increases the usability and relevance of the dataset (Dadkhah et al. 2024).

3.1.3. CIC UNSW-NB15 Dataset

The UNSW-NB15 dataset is a comprehensive resource that uses IXIA PerfectStorm to generate a dataset to produce modern normal and abnormal network traffic. Their data set includes nine categories of attacks and benign traffic. They captured 100GB of network traffic over two days, using the Argus and Bro-IDS tools to extract information from the traffic they intercepted. They extracted 47 categories of features, including Basic, Content, Time, and other features that they generated. The extracted flows are compared with the logs in the ground truth list according to source IP, target IP, source port, target port, and protocol. If the log matches any flow in the ground truth list, it will be flagged under the attack category. If more than one log in the ground truth list matches the flow, they compare the time stamps and select the log that matches the flow time stamp. The flow will be aborted in the worst case, even if they cannot decide on a label by comparison of the time stamp. All other flows will be flagged as benign after all malicious flows have been flagged, providing a comprehensive view of network traffic (Moustafa et al. 2015).

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Data Splitting

The dataset preparation process is a crucial step in the implementation of the proposed deep learning model. Each row in the dataset represents an IoT device sample. The cleaning process, which involves replacing missing values with the mean of the respective data instances, is a key part of this preparation. The use of the StandardScaler method to normalize the data ensures that the data points are on a balanced scale. Since the raw RF fingerprinting dataset is not predefined with labels, K-Means clustering is used to categorize the data points into two groups: legitimate IoT devices (Class 0) and malicious IoT devices (Class 1). Following K-Means clustering and feature selection, the dataset is then converted into NumPy arrays for efficient processing.

We divide the dataset into training sets (80%) and testing sets (20%). Afterward, 80% of the initial 80% subset was allocated for training purposes, while the remaining 20% was chosen for validation. The 20% validation set is employed after each training epoch to identify the optimal model performance, ensuring the model's accuracy. The development process includes an essential component that ensures the model's efficiency in identifying and predicting previously unseen data.

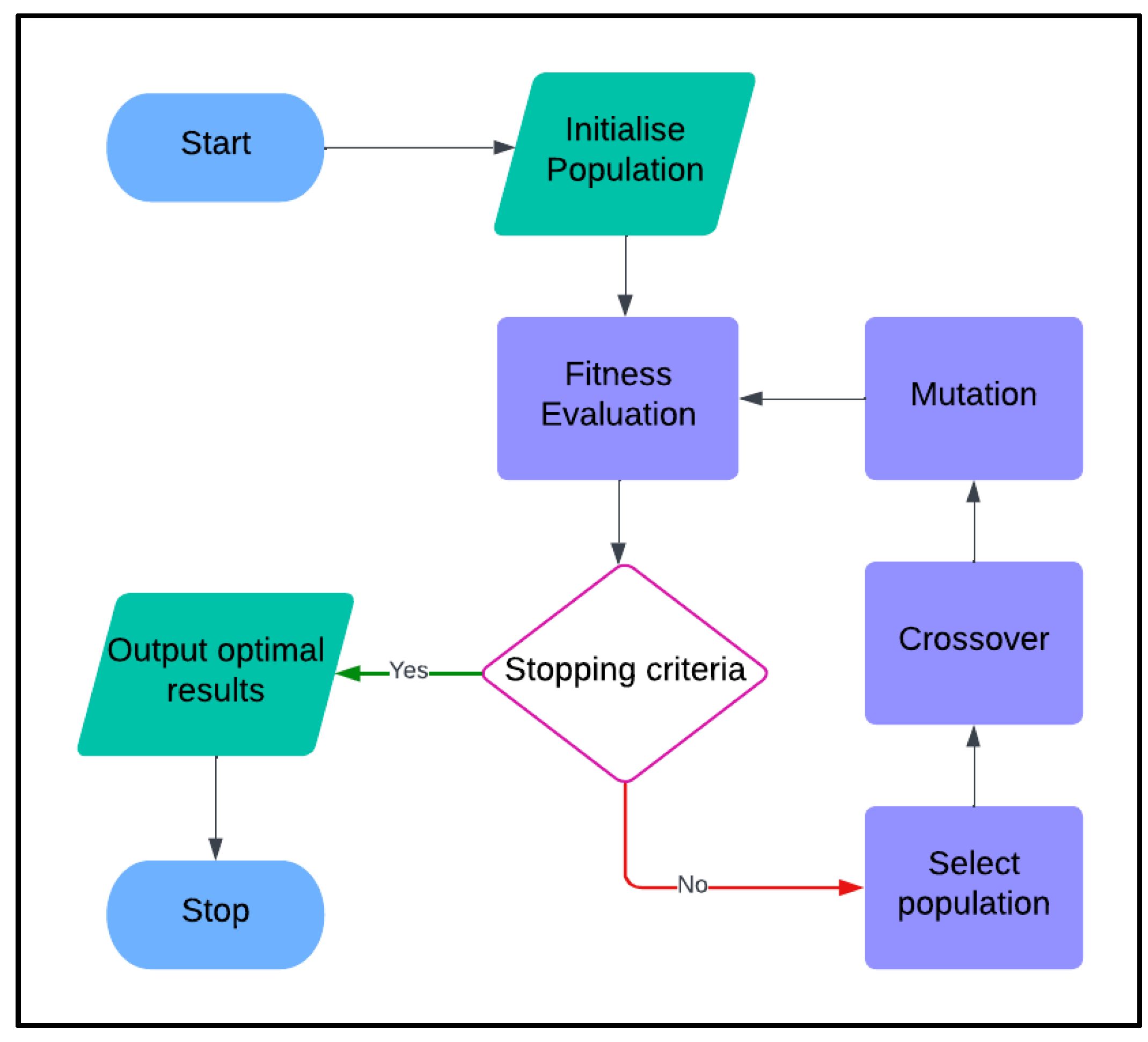

3.4. Feature Selection Using Genetic Algorithm

The initial dataset contains features that add complexity to the intrusion detection process, making the detection method more challenging. To enhance the performance of the intrusion detection approach, we employ a feature selection technique using the GA algorithm. The GA is a heuristic-based search approach that is based on Charles Darwin's natural evolution theory. It uses data structures with chromosomes that employ a recursive combination of searching techniques. This natural selection-based algorithm is a key part of our feature selection process (Pramanik et al. 2021). The fundamental workflow diagram that is used to design the genetic algorithm is shown in

Figure 2.

The key components of the GA-based feature selection are discussed below.

Chromosome Encoding: Each chromosome is represented by a binary string where 1 denotes the inclusion of a feature, and 0 denotes the exclusion of a feature.

Fitness Function: A DLB-based classification error function examines feature subsets. The goal is to reduce both the classification error and the total number of features chosen.

GA parameters:

Table 3 displays the parameters that are used in GA.

The procedure for feature selection using GA is discussed below.

Initial population: The inclusion or exclusion of a feature is represented as a random binary matrix. It ensures enough diversity across chromosomes to explore the search space.

Fitness evaluation: The step that separates the best from the rest. DLB is used to identify subsets of features and calculate classification errors. The less features and lower errors result in the best fitness scores, paving the way for high-quality feature selection.

Selection: The tournament selection ensures only the best chromosomes are carried forward, and then the two chromosomes are compared, and the one with better fitness is selected.

Crossover Binary XOR combines the two parent chromosomes to produce offspring.

Mutation: Alters bits in chromosomes with a low probability, playing a key role in promoting diversity and maintaining the genetic diversity of the population.

The new generation is formed by merging elite, crossover, and mutation offspring. This process repeats for 40 generations or until the GA converges.

Stopping criteria: The checkpoint that signals the end of our journey. The GA process stops if fitness improvements are minimal over 80 generations, ensuring we do not continue unnecessarily.

Our model's efficiency is underscored by the feature selection process of the Genetic Algorithm (GA). After creating each chromosome by randomly selecting genes (features), we form a new dataset using only the selected genes for classification. Once the GA converges, it considers only the features represented by the optimal chromosome for the dataset. GA selects three features in total, represented as binary 1s, with the positional index of 1s being 0 and 4.

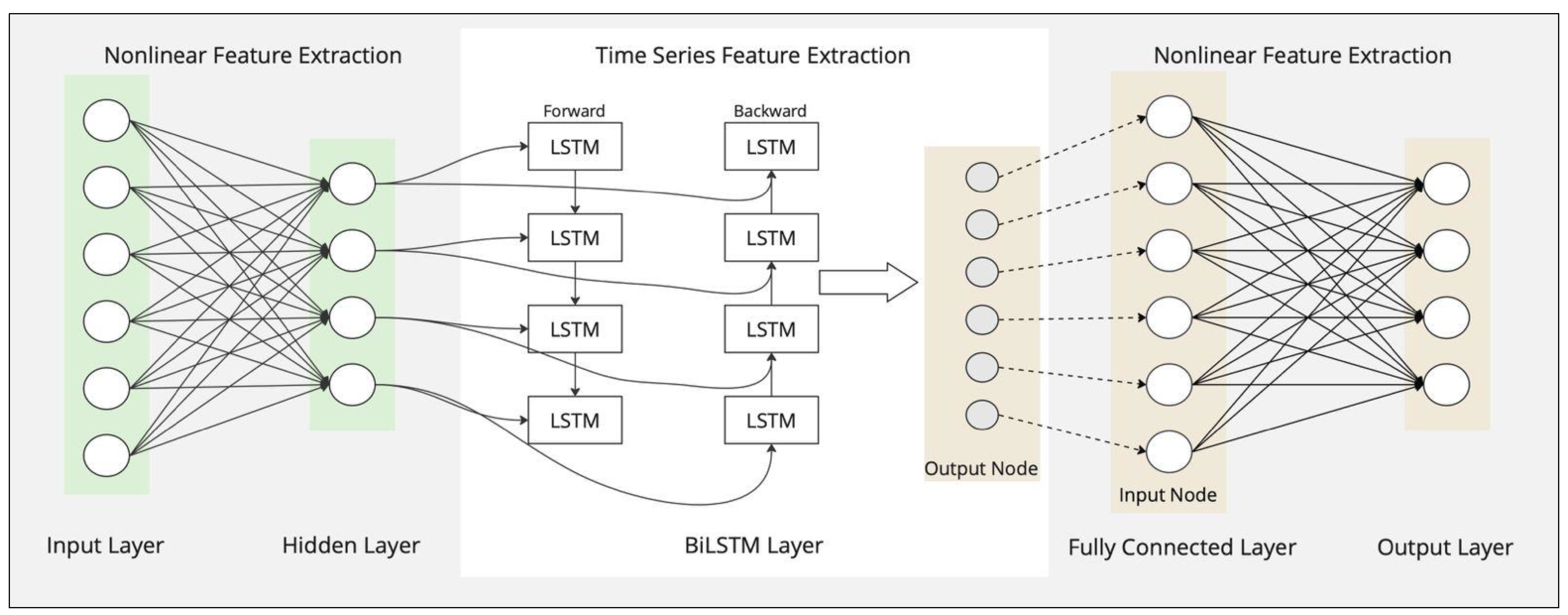

3.5. Model Selection

This study designs an intrusion detection model based on DLB to enhance the capabilities of BiLSTM in extracting nonlinear features and preserving its inherent bidirectional long-distance dependency characteristics. The use of deep neural networks to uncover hidden information within features and surpass traditional machine learning models is a unique approach. The DNN design is used to improve BiLSTM's deep nonlinear feature extraction capabilities. The combination of various network architectures typically increases the number of parameters within the original model, necessitating additional computational resources. A visual representation of the DNN-BiLSTM model architecture is shown in

Figure 3, illustrating the data flow through the model, including the input layer, hidden layers, BiLSTM layer, and output layer. When developing an IoT intrusion detection model, it is crucial to consider the model size and real-time performance, as well as how to enhance detection performance. These considerations are key to the successful implementation of the model.

The learning process of our model is facilitated by the activation functions in the Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). These functions allow for a variety of nonlinear transformations on the network data, helping the network to learn to perform complex tasks. The most used activation functions in neural networks are sigmoid, softmax, tanh, and ReLU. The deep neural networks extensively utilize the ReLU function, which outputs the same value for positive inputs and zero for negative inputs, facilitating rapid computation. Through the process of transforming the input into a nonlinear domain, these activation functions achieve the generation of nonlinear properties. The deep neural networks enable the system to acquire enhanced properties and functionalities through the combination of several nonlinear transformations.

The Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network is a specialized type of recurrent neural network (RNN) designed to overcome the gradient vanishing problem often encountered with long-term dependencies. This challenge is addressed through two key components in LSTM: the storage of cells and the management of cell states. These components allow the network to independently determine which information to retain and which to discard (Fu et al. 2022). Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) is an extension of the standard LSTM model that enhances sequential feature extraction by processing data in both forward and backward directions. Given an input sequence X = {x1, x2, ..., xT}, the equations below describe the computational units involved in the BiLSTM for updating each step.

- I.

Forward LSTM computations:

- II.

Backward LSTM computations:

The final output of BiLSTM is the concatenation of both hidden states:

where x

t is the notation used to indicate the current input, while h

t-1 and h

t+1 are the notations used to indicate the output from the final hidden layers. The output gate is responsible for determining whether the previously learned information c

t-1 may be kept.

Table 4 represents symbols used in the BiLSTM equations. The tanh function transforms any numerical input to a range between −1 and 1. To preserve the information for the current time step, the incoming signals pass sequentially through the gate cells.

The two layers of the LSTM are used to construct the bidirectional LSTM, and these layers work together to compute the hidden parameters in opposing directions. This bidirectional mechanism allows the network to capture long-range dependencies before and after each data point, improving intrusion detection accuracy (Cai et al. 2021).

Table 5 and

Table 6 represent the details of the model's layers and parameters used during the training, respectively.

3.6. Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME)

The LIME technique in XAI is employed to emphasize dataset features that are significant for training the proposed DL-IID. It enables the model to achieve the intended result (Ribeiro et al. 2016). It describes the predictions or detections generated by an ML or DL model by comparing them locally to a model that is easier to understand (Patil et al. 2022). Pantazatos et al. (2024) say that LIME is helpful because it is model-agnostic, which means it gives clear and easy-to-understand information on the importance of features. Security analysts can understand the reasons why different machine learning models make the predictions they do.

3.7. Model Quantization

Model quantization is a technique aimed at optimizing a model by decreasing the bit size of its variables from the standard 32-bit floating-point representation to a more limited 8-bit representation. This method uses an algorithm with a reduced bit size rather than the previously used full-precision techniques. Model quantization reduces computational resource consumption and enhances the model's inference speed. Model quantization generally employs a small 8-bit size for the representation of model parameters and activation functions. Consequently, we selected dynamic quantization for post-training as our method for model quantization. In the process of post-training dynamic quantization, weights are converted to int8, as is the case with all quantization methods. Additionally, activations are dynamically converted to int8, and efficient quantization is achieved by utilizing matrix multiplication and convolution during computation. In the research context described in this paper, post-training dynamic quantization is the best solution because it works independently of the dataset's training process, reduces model size, and maintains accuracy within acceptable limits. This makes deployment easier in IoT environments with limited resources.

4. Results and Discussion

In this section, we conduct experiments for the proposed IoT model to demonstrate its superior detection performance. The DLB model with the GA feature selection method is proposed because of its complex structure that protects against attacks on deep learning models compared to DNN and BiLSTM, which have simple model structures and are prone to adversarial attacks. We offer a concise summary of the experimental setup and the metrics used for evaluation.

We performed all evaluations on a Google Colab Platform with 12.7 GB of RAM and 107.7 GB disk space, using Python 3.10 and the Pytorch framework.

-

The study evaluates the model by measuring accuracy, precision, recall, and f1-score due to the complexity of intrusion detection in the IoT environment. The evaluation metrics and their corresponding calculation formulas are outlined below.

Accuracy: It measures the proportion of correct predictions.

Precision: It refers to an ability to identify intrusion instances correctly.

Recall: It refers to an ability to detect intrusion instances.

F1-Score: It calculates the harmonic mean of precision and recall.

where T

p is true positive, T

n is true negative, F

p is false positive, and F

n is false negative.

DLB + GA can be described as a type of model in which the DNN architecture is combined with BiLSTM. It is designed to work with features that are selected using the genetic algorithm to enhance its performance by focusing on the most relevant data attributes. This model is more robust but computationally intensive due to its complex architecture. On the other hand, DL-IID + GA is a lightweight version of DLB + GA. It similarly uses features selected by the genetic algorithm; however, it adopts a simplified architecture and employs dynamic quantization after the training process. This design enables DL-IID + GA to have reduced memory and reduced computation footprint, thus making it more suitable for resource-limited areas where effectiveness matters.

The proposed model is assessed in comparison to the base deep learning model with features extracted from GA using metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, f1-score, model size, and error metrics such as root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), and other. The outcomes of the experiments are presented in

Table 7 and

Table 8. The proposed method achieves a 99.84% accuracy, which is equivalent to the DLB + GA method and slightly higher than the DLB method (99.60%). In terms of precision, both DLB + GA and the proposed method achieve a perfect 100%, surpassing DLB (99.33%). The recall score of the proposed method (99.69%) is slightly higher than DLB + GA (99.67%). However, it is marginally lower than DLB (99.87%). Similarly, the F1-score for the proposed method and DLB + GA remains at 99.84%, outperforming DLB (99.60%). One of the most notable advantages of the proposed method is its significantly reduced model size (108.42 KB), making it more efficient compared to DLB (302.14 KB) and DLB + GA (299.66 KB). The results indicate that the proposed DL-IID + GA model maintains high classification performance while reducing computational complexity and storage requirements, making it a more efficient and scalable solution for intrusion detection.

The error metrics and their corresponding calculation formulas are outlined below.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): It indicates whether the model overestimates or underestimates values.

Mean Squared Error (MSE): It measures the average squared error of predictions.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): It shows how much the predictions deviate from actual values in absolute terms.

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE): It measures the percentage deviation of predictions from actual values.

Table 8 presents additional error metrics to evaluate the DL-IID model in comparison to DLB and DLB + GA. The metrics include MAE, MSE, RMSE, and MAPE. The proposed method (DL-IID + GA) achieves a MAE and MSE of 0.0016, which is comparable to DLB + GA and outperforms DLB, which has higher errors (0.0040). In terms of RMSE, the proposed method has a value of 0.0394, which is slightly lower than DLB + GA (0.0404) and significantly lower than DLB (0.0632), which indicates a lower prediction error. The MAPE for the proposed method is 0.31%, showing a minor improvement over DLB + GA (0.33%) but slightly higher than DLB (0.13%). These results show the efficiency of DL-IID + GA in minimizing error rates while maintaining high accuracy, demonstrating its reliability as an intrusion detection model. .

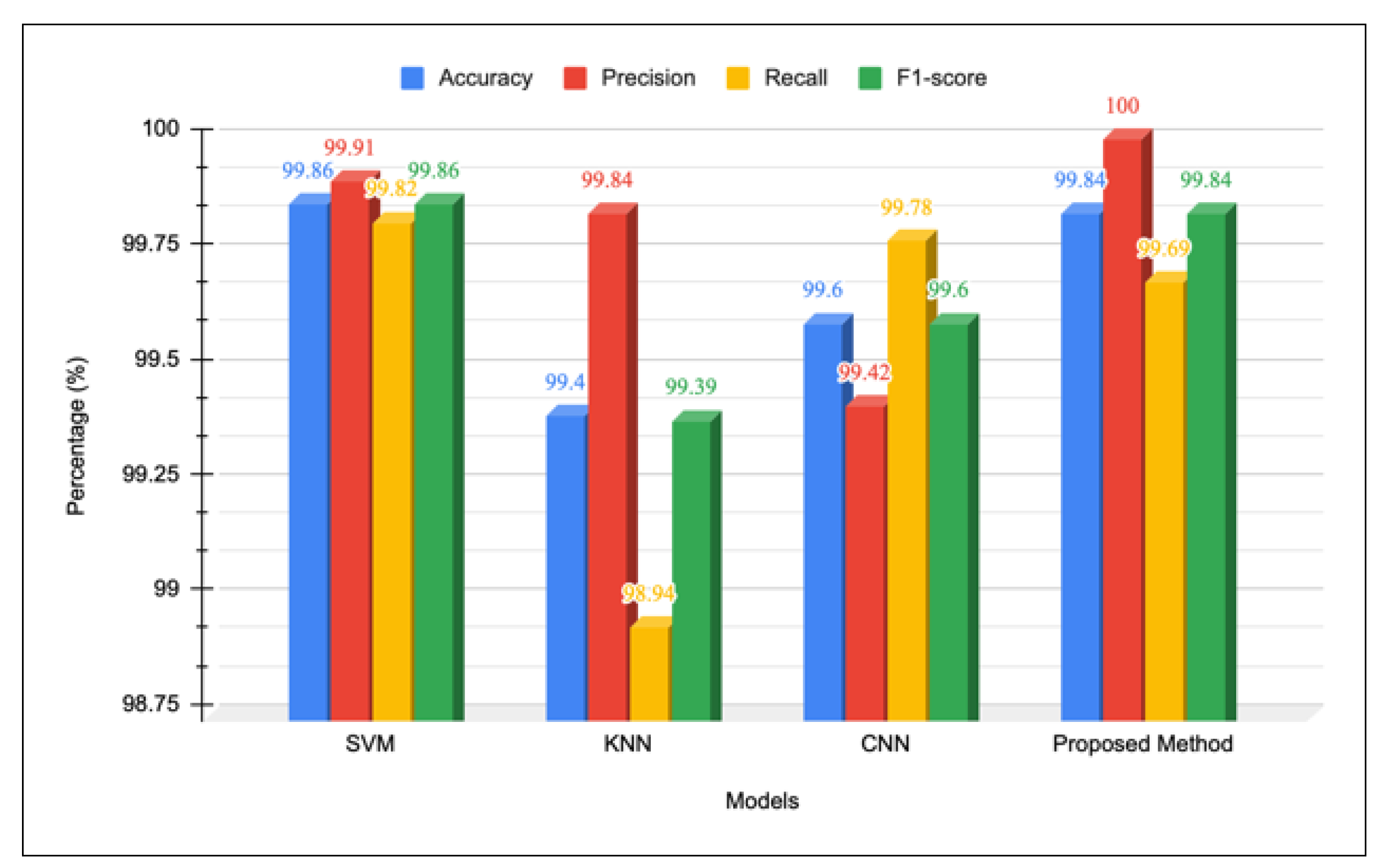

Moreover,

Table 9 gives a comparative analysis of the proposed DL-IID model with commonly used machine and deep learning-based intrusion detection methods. The DL-IID model surpasses existing IDS solutions in a variety of performance aspects. Compared to CNN (97.0%), KNN (98.13%), and LSVM (98.8%), DL-IID achieves a superior accuracy of 99.84%. In addition, error metrics support the effectiveness of the model as it has the lowest root mean squared error (RMSE) at 0.0394 and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of only 0.31%, which significantly reduces misclassification rates.

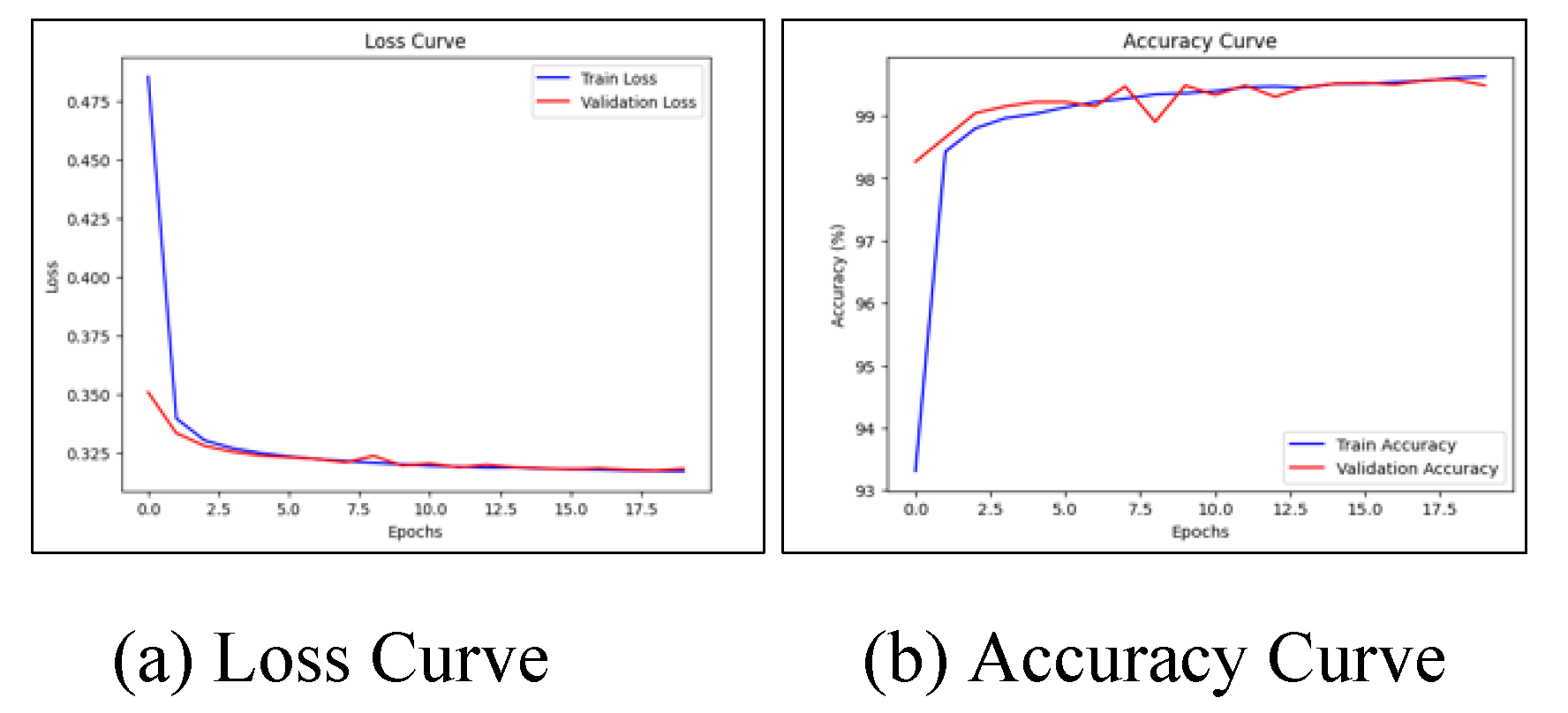

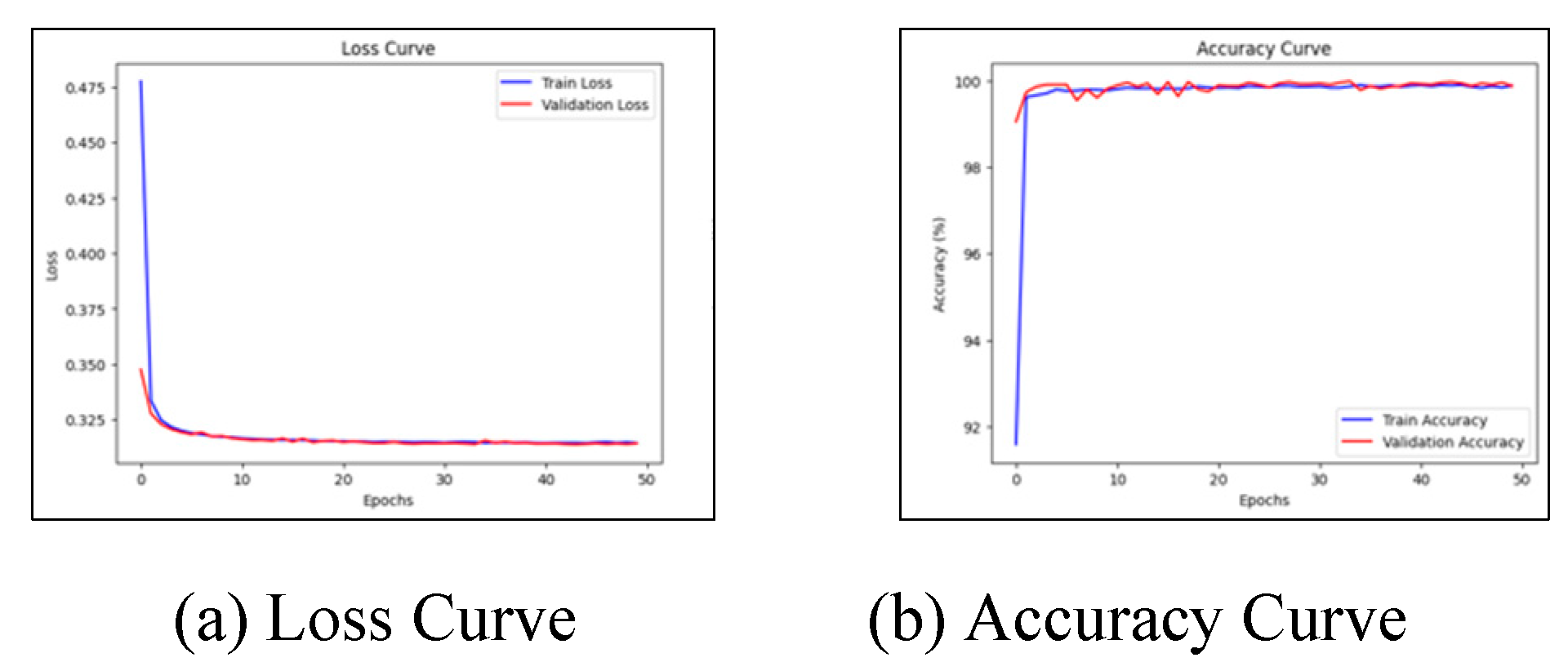

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the graphs of loss and accuracy during the training of the baseline deep learning model with and without selected features.

The proposed DL-IID model achieves an overall performance evaluation index above 99.5%, as shown in

Table 9 and

Figure 6, compared to machine and deep learning models used in other existing works, including SVM-based IoT IDS (Wang et al., 2020), KNN for RF fingerprinting (Ezuma et al., 2020), and CNN-based RF fingerprinting (Yu et al., 2019). The DLB model primarily employed the features selected using the GA technique. The DNN model architecture in DL-IID facilitates more efficient feature extraction that may fix the drawbacks of the BiLSTM model, thereby enhancing classification detection capabilities beyond those of the original local techniques while utilizing minimal computational resources. The proposed model achieves a precision of 100%, outperforming all other methods while also maintaining a high accuracy (99.84%), recall (99.69%), and F1 score (99.84%). Compared to previous models, the proposed method significantly reduces the model size (108.42 KB), making it more lightweight than the CNN-based model (189.89 KB), SVM-based (880.97 KB), and KNN-based (2820.48 KB) models. The results show the superiority of the proposed DL-IID model in terms of precision, overall classification performance, and computational efficiency, making it a strong candidate for IoT-based intrusion detection.

Table 10 presents a comparative performance analysis of the binary classification of the proposed DL-IID model across four different datasets: RF Fingerprint, CICIDS2017, CICIOMT2024, and UNSW-NB15. The evaluation metrics considered include accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, RMSE, and MAPE, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the model's effectiveness.

The performance of the DL-IID model is truly impressive, achieving exceptional accuracy across all datasets. Its robustness in intrusion detection is evident, with the highest accuracy (100%) seen on the CICIDS2017 dataset, where the GA selected 49 out of 85 features. Similarly, the classification performance on the UNSW-NB15 dataset is outstanding, with an accuracy of 99.99%, precision, recall, and F1-score all at 99.99%, and a very low RMSE (0.0087) and MAPE (0.01%), indicating minimal error rates.

For the RF fingerprint dataset, the model achieved 99.84% accuracy while using only two features out of 7, highlighting GA’s efficiency in feature selection. The recall value of 99.69% suggests strong detection capabilities, with an RMSE of 0.0394 and MAPE of 0.31%, a little more than other datasets. For the CICIOMT2024 dataset, the model maintained an accuracy of 97.66%, with a recall of 100%, suggesting high sensitivity in identifying malicious activities, although with a slightly elevated RMSE (0.1531). Overall, the results show that the DL-IID model consistently outperforms traditional IDS approaches, with nearly perfect detection accuracy and minimal errors across various datasets.

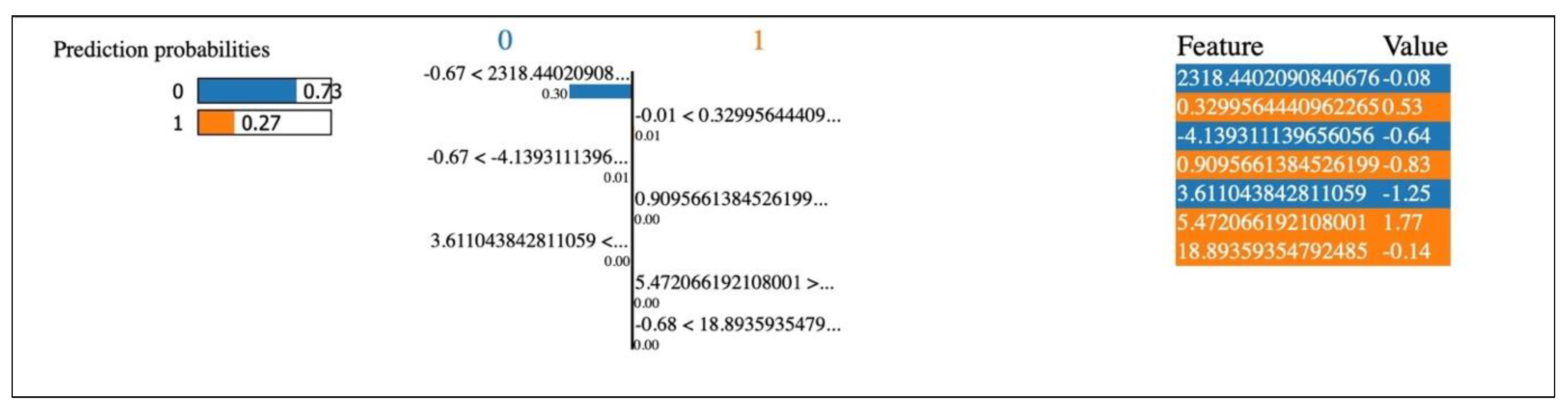

To conduct an analysis, we selected the tenth data point from the test set. This is because the first step in the operation of the LIME model is to select the data point that we want to understand. A new local dataset is produced by the LIME model by the modification of the tenth data point. After that, we proceeded to deploy the LIME model on the DLB and then set the number of features that corresponded with the dimensions of our training data. After that, we used DLB to generate predictions for the disturbed data instances, and then we trained a local interpretable model on those instances using the predictions provided by DLB. As seen in Figure. 7, the three different results are produced by LIME:

The first result shows the predicted probability assigned to each class label by the original model for the test data point.

The second result demonstrates the optimal properties that allow the local interpretable model to produce results for changed cases.

The third result shows a table showing the actual values for the elements.

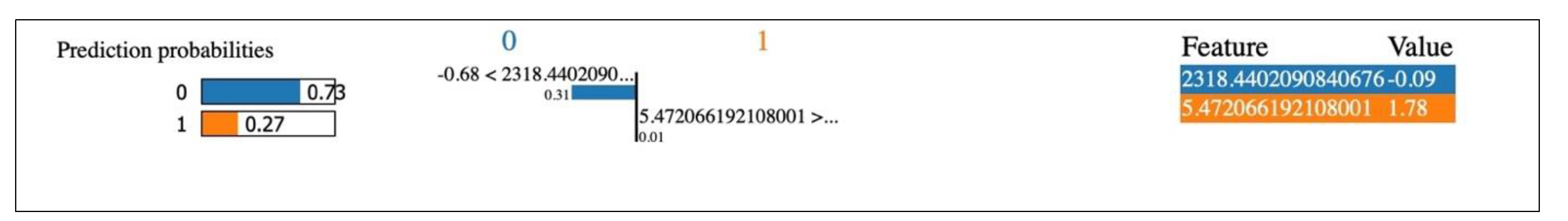

Figure 7 confirms that DLB accurately classified the specified test data point as 0, as confirmed by the output of the local model. In the end, we implement the LIME model on DLB using the features extracted from the GA method. Figure. 8 illustrates how Carrier Frequency Offset and Amplitude Mismatch are among the most effective features for classifying legitimate and malicious devices. A CFO deviation can increase the likelihood of a malicious classification. Likewise, Amplitude Mismatch can lead to false positives, underscoring the need to make changes for noisy conditions. While artificial intelligence-based intrusion detection systems (IDS) significantly increase security, they also present potential security risks and challenges that must be addressed. An important risk is adversarial attacks, where attackers deceive deep learning models using malicious inputs. Adversarial attacks involve subtle changes in the input data that cause the model to incorrectly classify threats while poisoning attacks involve the introduction of manipulated data into the training process, which degrades the performance of the model. Credibility and explainability are an issue, given that many deep learning models, such as BiLSTM, operate as black-box systems that make it challenging for security analysts to understand and verify their decisions. While LIME was selected due to its agnosticism to models and low computational costs that align with IoT environment demands, it does have some limitations when dealing with complicated nonlinear relations in a dataset. In addition, privacy concerns arise during training on sensitive IoT data, as models may inadvertently remember and disclose confidential information. The urgency of the situation is clear, and future work is needed to explore adversarial training, different privacy techniques, and robust modeling.

5. Conclusions and Future Scope

This research outlines the methodological basis and evaluation of the performance of the intrusion detection method that is based on the radio frequency fingerprinting capabilities that are present in IoT devices. The DL-IID model has several significant advantages over conventional IDS methods. It incorporates DNN and BiLSTM, which permit bidirectional feature extraction, leading to a higher degree of detection accuracy when compared to traditional CNN and SVM-based models. In addition, it uses the genetic algorithm effectively, which reduces the size of features, thereby increasing the efficiency of computation. Utilizing the XAI technique (LIME) guarantees better model interpretation, which increases confidence in the process of making decisions. Additionally, dynamic quantization decreases the size of the model, making it a viable option for resource-constrained IoT devices without causing significant performance degradation.

However, despite these benefits, there are some limitations. Although efficient in reducing the complexity of models, the quantization process could result in some slight errors in accuracy. In addition, the dataset that was used in this study, although extensive, does not completely replicate the changing and dynamic reality of IoT situations, as variables like the amount of network traffic congestion, adversarial interference, and protocol-related variability could affect the performance. Furthermore, even though LIME enhances explainability, it cannot handle complex, large-scale interactions between features, which may make it less effective in the deep feature extraction task. However, future research needs to concentrate on strengthening the model's resilience against adversarial attacks. This includes examining methods to protect privacy in training and evaluating the model on larger, more diverse datasets to increase generalization. In addition, other explainability techniques like SHAP or adversarial interpretability ought to be explored to gain deeper insight into the behavior of models. In addition, federated learning can be used to develop security models for intrusion detection in distributed IoT environments without exposing the data in its raw form, thus ensuring privacy and security.

Orchid: Ahwar Khan https://orcid.org/0009-0002-9502-8235, Dr. Faisal Anwer https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7198-704X

Statements and Declarations

Availability of data and material: The datasets utilized in this paper for training, testing, and validating the experiment are freely available on the internet and can be accessed through the links: RF fingerprinting dataset

https://github.com/ndducnha/mahalanobis_dataset, CICIDS2017 dataset

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/chethuhn/network-intrusion-dataset, CICIoMT2024 dataset

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/erengencturk/svagdataset, and UNSW-NB15 dataset

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mrwellsdavid/unsw-nb15?select=UNSW_NB15_testing-set.csv. The source code for the experiments can be accessed through the GitHub repository:

https://github.com/ahwarkhan/DL-IID.

Author Contributions

Author 1 has experimented and written the complete manuscript. Author 2 has reviewed the manuscript and suggested modifications and changes for further improvements.

Acknowledgement

The completion of this research paper would not have been possible without the support and guidance of Dr. Faisal Anwer, Department of Computer Science, Aligarh Muslim University. His dedication and overwhelming attitude towards helping his students are solely responsible for completing the research paper. The encouragement and insightful feedback were instrumental in accomplishing this task.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial or non-financial interests that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Taleb, T.; Samdanis, K.; Mada, B.; Flinck, H.; Dutta, S.; Sabella, D. On multi-access edge computing: A survey of the emerging 5G network edge cloud architecture and orchestration. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2017,

19(3), 1657–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J. KillerBee: Practical ZigBee Exploitation Framework or “Hacking the Kinetic World.”, 2009.

- Zhang, K.; Liang, X.; Lu, R.; Shen, X. Sybil attacks and their defenses in the internet of things. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2014,

1(5), 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, G.; Tiloca, M. Considerations on security in zigbee networks. 2010 IEEE International Conference on Sensor Networks, Ubiquitous, and Trustworthy Computing; 2010; pp. 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gope, P.; Millwood, O.; Sikdar, B. A scalable protocol level approach to prevent machine learning attacks on physically unclonable function based authentication mechanisms for internet of medical things. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2022,

18(3), 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, K.; Yu, S.; Nguyen, D.D.N.; Xiang, Y.; Feng, B.; Zhang, X. A tutorial on next generation heterogeneous iot networks and node authentication. IEEE Internet of Things Magazine 2021,

4(4), 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.K. A survey on IoT security: Application areas, security threats, and solution architectures. ACCENTS Transactions on Information Security 2023,

7(26). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.; Hussain, R.; Hassan, S.A.; Hossain, E. Machine learning in iot security: Current solutions and future challenges. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2020,

22(3), 1686–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, B.; Das, A.K.; Garg, S.; Piran, Jalil; Hossain, Md.M.S. Access control protocol for battlefield surveillance in drone-assisted iot environment. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022,

9(4), 2708–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Bera, B.; Wazid, M.; Jamal, S.S.; Park, Y. On the security of a secure and lightweight authentication scheme for next generation iot infrastructure. IEEE Access 2021,

9, 71856–71867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alladi, T.; Venkatesh, V.; Chamola, V.; Chaturvedi, N. Drone-MAP: A novel authentication scheme for drone-assisted 5G networks. IEEE INFOCOM 2021-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS); 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Miguelez-Gomez, N.; Rojas-Nastrucci, E.A. (2022) Antenna additively manufactured engineered fingerprinting for physical-layer security enhancement for wireless communications. IEEE Open Journal of Antennas and Propagation

3, 637–651. [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. (2017) ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Communications of the ACM;

60, pp. 84–90.

- Collobert, R.; Weston, J. A unified architecture for natural language processing. In Proceedings of the 25th international conference on Machine learning-ICML ’08; 2008; pp. 160–167. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, G.; Huang, H.; Song, Y.; Sari, H. Deep learning for an effective nonorthogonal multiple access scheme. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2018,

67(9), 8440–8450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Song, Y.; Yang, J.; Gui, G.; Adachi, F. Deep-Learning-Based millimeter-wave massive MIMO for hybrid precoding. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2019,

68(3), 3027–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yang, J.; Huang, H.; Song, Y.; Gui, G. Deep learning for super-resolution channel estimation and DOA estimation based massive MIMO system. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2018,

67(9), 8549–8560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Gui, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, R.P.; An, Y. ResInNet: A novel deep neural network with feature reuse for internet of things. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2019,

6(1), 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015,

521(7553), 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Patras, P.; Haddadi, H. Deep Learning in Mobile and Wireless Networking: A Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2019,

21(3), 2224–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuto, N.; Piazza, F.; Uncini, A. A neural network approach to data predistortion with memory in digital radio systems. Proceedings of ICC ’93-IEEE International Conference on Communications

1, 232–236.

- Mkadem, F.; Boumaiza, S. Physically Inspired Neural Network Model for RF Power Amplifier Behavioral Modeling and Digital Predistortion. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2011,

59(4), 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, G.B. Radar classification using a neural network. SPIE Proceedings; 1990; pp. 200–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ureten, O.; Serinken, N. Wireless security through RF fingerprinting. Canadian Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering 2007,

32(1), 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Du, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, Q.; Xiang, W. A Deep Learning Model for Network Intrusion Detection with Imbalanced Data. Electronics 2022,

11(6), 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Tao, Y.; Zhu, T.; Deng, Z. Short-Term Load Forecasting Based on Deep Learning Bidirectional LSTM Neural Network. Applied Sciences 2021,

11(17), 8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Hu, A.; Li, G.; Peng, L. A Robust RF Fingerprinting Approach Using Multisampling Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2019,

6(4), 6786–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kong, L.; Wu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Xu, C.; Chen, G. SLoRa. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems; 2020; pp. 258–270. [Google Scholar]

- Fadul, M.; Reising, D.; Loveless, T.D.; Ofoli, A. Nelder-Mead Simplex Channel Estimation for the RF-DNA Fingerprinting of OFDM Transmitters Under Rayleigh Fading Conditions. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2021,

16, 2381–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezuma, M.; Erden, F.; Kumar Anjinappa, C.; Ozdemir, O.; Guvenc, I. Detection and Classification of UAVs Using RF Fingerprints in the Presence of Wi-Fi and Bluetooth Interference. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2020,

1, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghnaiya, A.; Ali, A.M.; Kara, A. Variational Mode Decomposition-Based Radio Frequency Fingerprinting of Bluetooth Devices. IEEE Access 2019,

7, 144054–144058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.D.N.; Sood, K.; Xiang, Y.; Gao, L.; Chi, L.; Yu, S. Toward IoT Node Authentication Mechanism in Next Generation Networks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023,

10(15), 13333–13341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanieh, N.; Norouzi, Y.; Yang, Y.; Karmakar, N.C. A Review of Radio Frequency Fingerprinting Techniques. IEEE Journal of Radio Frequency Identification 2020,

4(3), 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chang, J. Survey of Mobile Device Authentication Methods Based on RF Fingerprint. IEEE INFOCOM 2019-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, W.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H. Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network Based on Singularity ROI for Fingerprint Classification. IEEE Access 2020,

8, 54554–54563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsky, Y.; Doitshman, T.; Elovici, Y.; Shabtai, A. Kitsune: An Ensemble of Autoencoders for Online Network Intrusion Detection. Proceedings 2018 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, B.; Das, D.; Maity, S.; Sen, S. RF-PUF: Enhancing IoT Security Through Authentication of Wireless Nodes Using In-Situ Machine Learning. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2019,

6(1), 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Xiao, Y. Research on the Internet of Things Device Recognition Based on RF-Fingerprinting. IEEE Access 2019,

7, 37426–37431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, L.; Xu, C.; Yuan, H. A RF fingerprint recognition method based on deeply convolutional neural network. 2020 IEEE 5th Information Technology and Mechatronics Engineering Conference (ITOEC); 2020; pp. 1778–1781. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Lin, Y.; Dou, Z.; Chen, Y. (2020) Research on RF fingerprint feature selection method. 2020 IEEE 91st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Spring); pp. 1–5.

- Bovenzi, G.; Aceto, G.; Ciuonzo, D.; Persico, V.; Pescape, A. A hierarchical hybrid intrusion detection approach in iot scenarios. GLOBECOM 2020-2020 IEEE Global Communications Conference; 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Cetin, E. Waveform domain deep learning approach for RF fingerprinting. 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik, P.K.D.; Pal, S.; Mukhopadhyay, M.; Singh, S.P. Big Data classification: Techniques and tools. In Applications of Big Data in Healthcare; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why should I trust you?”. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S.; Varadarajan, V.; Mazhar, S.M.; Sahibzada, A.; Ahmed, N.; Sinha, O.; Kumar, S.; Shaw, K.; Kotecha, K. Explainable artificial intelligence for intrusion detection system. Electronics 2022,

11(19), 3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazatos, D.; Trilivas, A.; Meli, K.; Kotsifakos, D.; Douligeris, C. Machine learning and explainable artificial intelligence in education and training-Status and trends. In Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering; Springer Nature Switzerland; Cham, 2024; pp. 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sharafaldin, I.; Habibi Lashkari, A.; Ghorbani, A.A. Toward generating a new intrusion detection dataset and intrusion traffic characterization. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dadkhah, S.; Neto, E.C.P.; Ferreira, R.; Molokwu, R.C.; Sadeghi, S.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoMT2024: A benchmark dataset for multi-protocol security assessment in IoMT. Internet of Things 2024,

28, 101351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, N.; Slay, J. UNSW-NB15: A comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set). 2015 Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS); 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Baldini, G.; Amerini, I.; Dimc, F.; Bonavitacola, F. Convolutional neural networks combined with feature selection for radio-frequency fingerprinting. Computational Intelligence 2023,

39(5), 734–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turukmane, A.V.; Devendiran, R. M-MultiSVM: An efficient feature selection assisted network intrusion detection system using machine learning. Computers & Security 2024,

137, 103587. [Google Scholar]

- Sadia, H.; Farhan, S.; Haq, Y.U.; Sana, R.; Mahmood, T.; Bahaj, S.A.O.; Khan, A.R. Intrusion detection system for wireless sensor networks: A machine learning based approach. IEEE Access 2024,

12, 52565–52582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, Md.A.; Islam, Md.M.; Uddin, M.A.; Hasan, K.F.; Sharmin, S.; Alyami, S.A.; Moni, M.A. Machine learning-based network intrusion detection for big and imbalanced data using oversampling, stacking feature embedding and feature extraction. Journal of Big Data 2024,

11(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Overall framework of the proposed detection scheme.

Figure 1.

Overall framework of the proposed detection scheme.

Figure 2.

A general workflow diagram of Genetic Algorithm for feature selection.

Figure 2.

A general workflow diagram of Genetic Algorithm for feature selection.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. The visual representation of the DNN-BiLSTM Model Architecture.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. The visual representation of the DNN-BiLSTM Model Architecture.

Figure 4.

Training Loss and Accuracy Curves for DLB Model without GA-based Feature Selection.

Figure 4.

Training Loss and Accuracy Curves for DLB Model without GA-based Feature Selection.

Figure 5.

Training Loss and Accuracy Curves for DLB Model with GA-based Feature Selection.

Figure 5.

Training Loss and Accuracy Curves for DLB Model with GA-based Feature Selection.

Figure 6.

Performance evaluation of our proposed scheme compared to existing works .

Figure 6.

Performance evaluation of our proposed scheme compared to existing works .

Figure 7.

LIME results of DLB without GA-based feature selection.

Figure 7.

LIME results of DLB without GA-based feature selection.

Figure 8.

LIME results of DLB with GA-based feature selection.

Figure 8.

LIME results of DLB with GA-based feature selection.

Table 1.

List of abbreviations used in the paper.

Table 1.

List of abbreviations used in the paper.

| BiLSTM |

Bidirectional LSTM |

| CD |

Chi-square Distribution |

| CFO |

Carrier Frequency Offset |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| DL-IID |

Deep Learning-based IoT Intrusion Detection |

| DNN |

Deep Neural Network |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithm |

| KNN |

K-Nearest Neighbor |

| LIME |

Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| LSVM |

Linear Support Vector Machine |

| MAC |

Message Authentication Code |

| MD |

Mahalanobis Distance |

| MSCNN |

Multisampling Convolutional Neural Network |

| NGN-IoT |

The Next Generation Networks and IoT |

| NGNs |

The Next Generation Networks |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| RF |

Radio Frequency |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Network |

| ROI |

Region Of Interest |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| XAI |

Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

Table 2.

Summary of the related machine and deep learning methods in the intrusion detection domain.

Table 2.

Summary of the related machine and deep learning methods in the intrusion detection domain.

| Year [Ref.] |

Model |

Overview |

Feature Extraction / Feature Selection |

Model Optimization |

| 2018 |

Autoencoder |

Kitsune aims to minimize labeling efforts by utilizing an Autoencoder to distinguish between normal and abnormal patterns. |

Damped Incremental Statistics |

No |

| 2019 |

PCA + SVM |

Utilize PCA for dimensionality reduction and SVM to classify RF fingerprinting features. |

PCA |

No |

| 2019 |

MSCNN |

Utilize MSCNN to sort ZigBee devices into groups based on features of interest in a certain area. |

MSCNN |

No |

| 2019 |

LSVM |

Utilizes RF fingerprinting and LSVM for classification purposes. |

Higher Order Statistics |

No |

| 2020 |

KNN |

Identification and categorization of UAVs by RF fingerprinting methods used on wireless communication protocols. |

Neighborhood Component Analysis (NCA) |

No |

| 2020 |

CNN |

Adapt the traditional CNN architecture of VG-16 for frequency fingerprint recognition. |

VGG-16 |

No |

| 2020 |

KNN |

Employed KNN for classification and improved recognition performance by selecting a compatible feature subset. |

RELIEF-F, F Score, Laplacian Score |

No |

| 2021 |

MDA/ML |

Utilize the simple Nelder-Mead bandwidth estimator to mitigate noise in Rayleigh fading environments. |

No |

Nelder-Mead (N-M) Simplex Algorithm |

| 2023 |

MD/CD |

An efficient authentication mechanism for IoT nodes in 5G networks utilizing radio frequency fingerprinting when combined with Mahalanobis Distance (MD) and Chi-square Distribution (CD) theories. |

Base Stations |

No |

| 2023 |

CNN |

A CNN-based intrusion detection framework with feature selection to enhance accuracy and reduce computational complexity in IoT networks. |

ReliefF, Generalized Fisher score, Structured Graph Optimization, etc. |

No |

| 2024 |

M-MultiSVM |

A hybrid machine learning framework for intrusion detection, which addresses problems such as class imbalance and high-dimensional feature space. |

Modified single-value decomposition (M-SvD) |

Mud ring optimization |

| 2024 |

CNN |

A CNN-based intrusion detection system for wireless sensor networks using the Aegean Wi-Fi Invasion Dataset (AWID). |

No |

No |

| 2024 |

Decision Tree, Random Forest, Extra Trees, XGBoost |

A machine learning-based intrusion detection system using Random Oversampling, Stacking Feature Embedding, and PCA. |

Stacking of features, PCA |

No |

Table 3.

Parameters used in Genetic Algorithm for feature selection.

Table 3.

Parameters used in Genetic Algorithm for feature selection.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Population size |

20 |

| Number of features |

7 |

| Selection mechanism |

Tournament selection |

| Crossover type |

Arithmetic |

| Crossover probability |

0.8 |

| Mutation type |

Uniform |

| Mutation probability |

0.05 |

Table 4.

Notations for BiLSTM Equations.

Table 4.

Notations for BiLSTM Equations.

| Symbol |

Description |

|

Input gate (forward/backward direction) |

|

Forget gate (forward/backward direction) |

|

Output gate (forward/backward direction) |

|

Cell state (forward/backward direction) |

|

Cell hidden state (forward/backward direction) |

|

Element-wise multiplication |

|

Weight matrices for input and hidden states |

|

Sigmoid activation function |

Table 5.

Layer details of the proposed model architecture.

Table 5.

Layer details of the proposed model architecture.

| Layer No. |

Layer Type |

Input Shape |

Output Shape |

Activation Function |

| 1 |

Fully Connected (FC) |

(batch_size, input_size) |

(batch_size, 128) |

ReLU |

| 2 |

Fully Connected (FC) |

(batch_size, 128) |

(batch_size, 64) |

ReLU |

| 3 |

Reshape (Unsqueeze) |

(batch_size, 64) |

(batch_size, 1, 64) |

- |

| 4 |

BiLSTM |

(batch_size, 1, 64) |

(batch_size, 1, hidden_size*2) |

- |

| 5 |

Fully Connected (FC) |

(batch_size, hidden_size*2) |

(batch_size, output_size) |

Softmax |

Table 6.

Parameters used during the training of the proposed model.

Table 6.

Parameters used during the training of the proposed model.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Optimizer |

Adam |

| Learning Rate |

0.0001 |

| Input Size |

7 |

| Batch Size |

128 |

| Hidden Size |

64 |

| Output Size |

2 |

| Epochs |

50 |

| Loss Function |

Cross Entropy Loss |

Table 7.

Performance evaluation of our proposed scheme compared to the baseline model with and without GA-based feature selection.

Table 7.

Performance evaluation of our proposed scheme compared to the baseline model with and without GA-based feature selection.

| Model |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-score (%) |

Model Size (KB) |

| DLB |

99.60 |

99.33 |

99.87 |

99.60 |

302.14 |

| DLB + GA |

99.84 |

100.0 |

99.67 |

99.84 |

299.66 |

| Proposed method (DL-IID + GA) |

99.84 |

100.0 |

99.69 |

99.84 |

108.42 |

Table 8.

Error metrics for evaluation of DL-IID to baseline model with and without GA-based feature selection.

Table 8.

Error metrics for evaluation of DL-IID to baseline model with and without GA-based feature selection.

| Model |

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) |

Mean Squared Error (MSE) |

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) |

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) |

| DLB |

0.0040 |

0.0040 |

0.0632 |

0.13% |

| DLB + GA |

0.0016 |

0.0016 |

0.0404 |

0.33% |

| Proposed method (DL-IID + GA) |

0.0016 |

0.0016 |

0.0394 |

0.31% |

Table 9.

Classification metrics of the proposed method in comparison with the existing works.

Table 9.

Classification metrics of the proposed method in comparison with the existing works.

| Study |

Methodology |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-score (%) |

Model Size (KB) |

| Wang et al. (2020) |

SVM-based IoT IDS |

99.86 |

99.91 |

99.82 |

99.86 |

880.97 |

| Ezuma et al. (2020) |

KNN for RF fingerprinting |

99.40 |

99.84 |

98.94 |

99.39 |

2709.34 |

| Yu et al. (2019) |

CNN-based RF fingerprinting |

99.60 |

99.42 |

99.78 |

99.60 |

189.89 |

| Proposed DL-IID Model |

DNN-BiLSTM-Quantization-based IoT IDS |

99.84 |

100.0 |

99.69 |

99.84 |

108.42 |

Table 10.

Results of binary classification comparison of the proposed DL-IID model on different datasets.

Table 10.

Results of binary classification comparison of the proposed DL-IID model on different datasets.

| Dataset |

Total number of features |

Features Selected |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-score (%) |

RMSE |

MAPE (%) |

| RF Fingerprint |

7 |

2 |

99.84 |

100.0 |

99.69 |

99.84 |

0.0394 |

0.31 |

| CICIDS2017 |

85 |

49 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

0.0038 |

0.00 |

| CICIoMT2024 |

45 |

26 |

97.66 |

97.66 |

100.0 |

98.81 |

0.1531 |

0.00 |

| UNSW-NB15 |

44 |

20 |

99.99 |

99.99 |

99.99 |

99.99 |

0.0087 |

0.01 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).