1. Introduction

The forestry industry is one of the oldest industries created by humans, and the use of hand-sawn wood has been documented since ancient times. Wood has served humans as a source of energy since the discovery of fire, while the first industry to use wood to produce boards and planks for construction was sawmilling, following the invention of the steam engine [

1,

2,

3]. Diversification in the production and application of wood today makes the primary forestry industry enormously varied in its types of products, from sawn, planed, or dimensioned wood to the preparation of profiles, sticks, matches, plywood, veneers, fiberboard, particleboard, chips, pulp, cardboard, corrugated media, household paper, writing paper, newsprint, resin, rosin and its derivatives, specialized products [

1,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Within the timber industry, forest harvesting, which refers to the cutting and delivery of trees in a productive, safe, economical, and ecological process, is of decisive importance as it involves the conversion of trees into marketable raw materials by specific industrial or individual requirements and needs. Wood generally undergoes several processing steps before being transported: felling, delimbing, debarking, crosscutting, chipping, wood extraction, stacking, loading, and transport. Some of these steps may be skipped depending on quality requirements, environmental and social constraints, technological knowledge, and access to technologies [

12]. Of particular note in this process is the use of roundwood, which in Honduras is used for industrial and domestic purposes, and industrial use, which includes all wood from managed production forests. In some cases, it includes wood from trees felled by wind or burned in forest fires. Trees are cut down for infrastructure construction, infested trees, and the use of certified plantations.

Forest management is providing a forest with the proper care to keep it healthy and vigorous so that it can provide the products and amenities that the owner desires. Forest management, also known as forest planning, is developing and implementing a plan that integrates all the principles, practices, and techniques necessary to care for the forest properly. To this end, a forest management plan is used, which is a technical, legal, and operational document that establishes the objectives and purposes of the management of a given forest area, including the scheduling of necessary investments and silvicultural activities for protection, conservation, restoration, and utilization required to achieve forest sustainability per its economic, social, and environmental functions. Its validity is established based on the plan's objectives [

13,

14,

15].

During the first decade of the 21st century, forestry industries and their input and product markets have faced internal and external structural changes, following creative destruction [

16,

17] and the centralization of natural resource management in local actors. Although these processes are still relatively new in many cases, now is the time to begin analyzing these experiences, evaluating their development, and identifying promising trends and problematic developments that need to be adjusted for the future [

18]. This can be done in Latin America and the Caribbean, and especially in Central America, where environmental degradation is increasing and, for the moment, the situation is technically reversible [

19,

20].

In addition to the timber industry, Central America recognizes environmentally friendly services such as ecotourism, biodiversity, carbon sequestration, water conservation, and non-timber forest products. These services are important from an ecological and economic point of view and have a decisive influence on the socioeconomic well-being of the population. From an economic point of view, forests are mainly associated with products traded on the market. Still, if we study forests from an ecological economics perspective, we also include the relationships between humans and nature in a longer-term perspective [

21].

Within Central America, Honduras and Nicaragua have extensive natural forest cover and are highly dependent on natural resources for their economy and livelihoods [

22,

23]. In order to promote responsible timber consumption, other regions of the world, such as the European Union, have been promoting policies since 2003 that encourage legal timber trade to their countries. This strategy could also be applied in Central America, where there is less control over cross-border trade in these goods. Control could be achieved through greater digitization. There are more than 650 primary and secondary wood product companies in Costa Rica, with an estimated production value of US

$150 million. It is important to note that 35 companies are vertically integrated, from forest plantation management to sales and customer service. However, these leading companies are not technologically comparable to those in more developed countries [

24], leading to production and trade inefficiencies.

In 1974, a policy of sustained yield (balance between the extraction rate and natural growth) was established in Honduras. In 1975, the first Management Unit was established in the Las Lajas pine forest in Comayagua, followed by eight more units, the completion of the national forest inventory, and the start of the permanent plot program, which has formed the basis of the database on pine forest yields in Honduras [

7]. Similarly, Honduras' forest policies have undergone drastic changes in the last two decades, such as the Law for the Modernization and Development of the Agricultural Sector, which returned all property rights over forest resources to their rightful owners. In 2007, the new Forestry, Protected Areas, and Wildlife Law was passed, creating the National Institute for Forest Conservation and Development, Protected Areas, and Wildlife (ICF), which emphasizes promoting and managing public forests with community participation [

25].

In Honduras, the annual operational plan is the technical, legal, and operational instrument that establishes the forestry, protection, restoration, utilization, and other activities to be carried out during the period covered by the forest management plan. Forest management plans are approved for the total area covered by a legal document on land tenure. Thus, the total area of the management plan is that which is legally covered by a title deed, while the area to be managed is that in which protection and utilization activities will be carried out, and the area to be intervened is where forest utilization activities will be carried out [

26].

The ICF promotes the coordinated participation of the private and social sectors in sustainable forest management and the management of protected areas and wildlife, helping to improve forestry's contribution to Honduras's economic, social, and environmental development through job creation, increased production, and reduced ecological vulnerability. To be effective and efficient in carrying out the activities for which it is responsible by law, the ICF has been divided administratively at the national level into twelve forest regions and twenty-four local offices (

Table 1).

This research aims to analyze the current situation of the primary forestry industry in Honduras and propose strategies for improving the environment, production, and commercial efficiency to achieve a more ecologically sustainable world. The structure of this article is as follows: introduction, theoretical framework, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusions.

2. Materials and Methodology

Secondary information was used to prepare the analysis and compile existing documentation, primarily published literature, digital files distributed by recognized organizations, and unpublished reports. An exhaustive statistical review was conducted from 2014 to 2023, and a bibliographic review was conducted from 1998 to 2024 to analyze the sawmill industry in Honduras. A comparative analysis was then made of the prevailing conditions in this industry regarding the number of sawmills, production, apparent consumption, imports, and exports of sawn wood. Much of the analysis was carried out using information from the official databases of the Institute for Forest Conservation, Protected Areas, and Wildlife [

27,

28].

The forestry industry, whose categories and branches are shown in

Table 1, is divided into primary, secondary, and tertiary industries. The primary industry consists of the cultivation and planting of forests, including the extraction of wood and bamboo, as well as the cultivation of economic forest products and the utilization of wild animals. The secondary industry includes the processing and manufacturing timber and non-wood forest products. The tertiary sector includes forest ecosystem services, forest tourism services, and other services. The total value of forest production is the sum of the production values of the three [

29,

30,

31].

The current situation of the primary forestry industry worldwide is characterized by a complex interaction of ecological, economic, and social factors that influence its sustainability and development. The forestry industry is increasingly recognized for its potential to contribute to economic growth, and therefore, the environmental challenges that this growth entails must be addressed. The transformation of the forestry industry depends on establishing an innovative system that integrates state, regional, and municipal management efforts with research and business initiatives [

32], and high-value primary forests must be protected by preventing deforestation [

33]. The coupling of economic and ecological development in forest areas demonstrates a gradual enrichment of forest resources and a reduction in ecological vulnerability attributed to implementing ecological protection policies [

34].

In the forest products industry, it is essential to implement sustainable practices embedded in the circular economy to improve the resilience and adaptability of the industry. The concept of the circular economy, which is emerging as a vital framework for improving the sustainability of forest resources, emphasizes the need for innovative practices to mitigate the adverse effects of population growth and industrialization on forest ecosystems. Furthermore, given the impact of anthropogenic activities, particularly industrial-scale forestry, it is essential to ensure the sustainability of the forestry industry. Sustainability is assessed through methodologies that evaluate the sector's performance, as it significantly increases the added value and prices of forest products, underscoring the importance of the timber industry as a fundamental sector element.

Alongside sustainability, integrating carbon management strategies into biomass harvesting guidelines is crucial to align forest biomass use with climate change mitigation efforts. Research indicates that logging practices can cause a rapid decline in forest diversity and functionality, in contrast to the effects of natural disturbances such as forest fires. Effective management practices are essential to mitigate these impacts and ensure the sustainable production of industrial wood, which remains a key raw material for various sectors. Thus, in the context of a low-carbon economy, the role of the forestry industry is fundamental to driving so-called green economic growth.

2.1. The Current Situation of the Primary Forestry Industry in Latin America and the Caribbean

In Latin America and the Caribbean, this trend has implications for social justice and environmental sustainability, as it can perpetuate an agricultural system that does not adequately address the needs of local populations. The agricultural sector has been identified as one of the main contributors to deforestation. Socioeconomic pressures, including demand for land and resources from a growing population, exacerbate this trend. Between 2001 and 2015, Latin America experienced a loss of up to 25% of its original forest cover due to these land use changes. There has been an increasing emphasis on sustainable forest management practices in response to these challenges.

A successful example of the fight against deforestation in Latin America is the ‘Mata Atlântica program’, conceived and implemented in Brazil. This nation has suffered extensive degradation and has less than 16% of its original forest cover. Another example is Central America, particularly Honduras, where forest plantations have become a viable alternative to natural forests. Governments have promoted plantations to use abandoned agricultural land and mitigate the impacts of deforestation, which is why the '20 × 20 Initiative' carried out since 2014 in Latin American and Caribbean countries with the initial goal of restoring 20 million hectares of degraded land by 2000, a target that was later expanded to 50 million hectares of land by 2030, is an example of a change in the dynamics of land degradation in the region into fertile and productive land, It is therefore a public-private partnership that benefits not only the current generation, but above all future generations by emphasizing the importance of achieving multifunctional landscapes that improve ecosystem services and support human well-being. As a result, forestry practices throughout the Americas and the Caribbean have improved significantly, although the problem of biodiversity remains to be resolved. The region's biodiversity is under threat, requiring effective strategies to protect forest ecosystems, mainly due to the introduction of invasive species that have altered the ecosystem. These invasive tree species were planted solely for economic rather than environmental reasons. Aware of this fact, recent studies emphasize the importance of integrating ecological protection with economic development to ensure the sustainability of forest resources.

However, despite these efforts, the forestry industry in Latin America and the Caribbean continues to face challenges such as illegal logging, land tenure conflicts, and the need for effective governance structures to support sustainable practices. In addition, the role of biomass energy in the region is significant, as Latin America and the Caribbean countries are major consumers of biofuels derived from their extensive forest resources. Collaborative approaches that integrate local communities, governments, and non-governmental organizations are essential to the success of forest landscape restoration initiatives. Restoration efforts are critical for biodiversity conservation and providing vital ecosystem services to local communities.

Regarding the primary forestry industry in Central America, forestry companies are currently navigating a complex landscape characterized by development opportunities and challenges, among which illegal timber trade stands out. Illegal trade remains a critical problem driven by institutional weaknesses and socio-political factors undermining regulatory frameworks. This illegal activity impacts biodiversity and contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, as deforestation and forest degradation are significant sources of carbon emissions in the region. Therefore, strong governance and sustainable forest management practices are needed to avoid the adverse effects of growing pressure from population growth and economic development on the Honduran economy and population. Socioeconomic variables drive land use changes, negatively affecting biodiversity and carbon sequestration capacity.

In addition, demand for wood, especially for sustainable construction, is rising. The global shift toward mass timber products, which offer a lower carbon footprint than traditional building materials, could benefit Central American and Honduran forestry by creating new markets for sustainably sourced wood. This trend aligns with the broader movement toward green building practices, which are gaining traction in various parts of the world, including Latin America and the Caribbean. The potential for wood to play an important role in sustainable construction is particularly relevant given the region's rich biodiversity and the rapid growth cycles of many native tree species [

35] and carbon sequestration. Management practices for these plantations are evolving, particularly nature-based management, which is a promising approach that balances economic returns with ecological sustainability [36].

Honduras, with a total area of 112,492 km2, of which 98,629 km2 is agricultural and forest land (87.67% of the territory)[

26], is the Central American country with the most significant area covered by forest (56.06% of the territory)[

26] (

Table 2), which is why it is the Central American country with the most significant potential to become the largest producer of wood and other non-timber forest products and, consequently, with significant potential to develop projects and contribute to climate change mitigation. Some 70 representative ecosystems of subtropical natural forests range from coastal beach ecosystems to cloud forests in the highest parts of the mountain ranges. Forests dominate the ecosystems in Honduras, with forest formations classified into five main forest types:

1) Pine forests with seven identified species (Pinus caribaea, Pinus oocarpa, Pinus maximinoi, Pinus tecumumanii, Pinus ayacahuite, Pinus pseudostrobus, and Pinus hartwegii);

2) Lowland broadleaf forests with more than 200 tree species and great biodiversity

3) Mangrove forests

4) Broadleaf cloud forests, pine forests, or mixed highland forests; and

5) Dry broadleaf forests

Table 2.

Primary categories in the forest and wood processing sector.

Table 2.

Primary categories in the forest and wood processing sector.

| Cluster category |

Industry branches |

| Forestry |

Forestry companies and consultants |

| Wood processing industry (primary wood processing) |

Sawmills, veneer, wood-based panels, and other wood processing industries |

| Wood manufacturing (secondary wood processing) |

Furniture, wood crafts, wood construction, wood-based packaging, and other specialized wood processing industries |

| Other wood industries |

Pulp and paper, printing and publishing, firewood, timber trade, and ancillary industries for wood products |

Table 2.

Area (in hectares) of forest cover in Honduras.

Table 2.

Area (in hectares) of forest cover in Honduras.

| Forest Type |

Hectares |

In % |

| Broadleaf Forest (including Mixed Forest and Tique palm Forest) |

4,312,771.59 |

68.30 |

| Coniferous Forest (including Plagued Forest) |

1,951,977.87 |

30.91 |

| Mangrove Forest |

50,065.14 |

0.79 |

| TOTAL |

6.314.814,60 |

100.0 |

Forest products are divided into three types: 1) Timber or wood products derived from roundwood, from which charcoal, firewood, and industrial roundwood are obtained. 2) Non-timber or non-wood products, also known as “minor” or “secondary” forest products, cover a wide range of animal and forest products other than wood. 3) Services: Traditionally, the forestry sector has been perceived only as a source of wood and firewood and as an obstacle to agricultural development. In recent years, this perception has changed, and greater importance has been given to the services provided by forests.

Table 3 shows the distribution of primary forestry companies by regional office, according to information provided in the Forestry Statistical Yearbook of the Forest Conservation Institute (ICF). Corresponding to the years 2014 to 2023, with estimates for 2024. From 2014 to 2016, the number of industries reporting production remained stable, but there was a decline in 2018. In 2019, there was an increase in the number of industries reporting production. In 2020 and 2021, the number declined due to COVID-19, while recovery has been steady since 2022.

Table 4 shows the economic value (in million USD) of coniferous and broadleaf wood products from 2016 to 2024. Data from 2023 and 2024 have been estimated using 3-year moving averages. Except for 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, timber production in Honduras has remained constant over the last decade.

As detailed in

Table 5, Honduras's wood processing industry produced 103.38 million board feet (MBF) of sawn wood from coniferous and broadleaf species. A significant portion, 84.06% or 86.8 MBF, of Honduras' forest production was concentrated in the forest regions of Francisco Morazán (71.35 MBF), Paraíso (9.62 MBF), and Noroccidente (5.91 MBF). The largest share of this production came from the primary forest industry, as detailed in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

Table 6 shows the Honduran exports, imports, and trade balance of forest products by market (value in USD). Except for Central America, North America, and the Caribbean countries, where Honduras has a trade surplus, all other regions of the world import more than they export, which shows the weakness of this sector's businesses in focusing solely on exports to regions closest to Honduras. It is therefore necessary to strengthen the export component of this industry by opening new markets and diversifying trade flows to reduce commercial risk.

Using data from

Table 4, we will apply a one-way ANOVA to investigate the effect of wood products (7 levels) and their interaction on the quantity produced (dependent variable) value. Data for 2023 and 2024 have been estimated using moving averages for the last three years. The initial hypotheses (null hypothesis and its corresponding alternative) are as follows, related to the main effect of the ‘product’ factor,

H0: There are no significant differences in the mean quantity produced between the seven wood products. Formally,

being the mean quantity produced of product 'j' [3]

H1: At least one product has a significantly different average quantity produced from the others. Formally,

for at least one pair of products ‘j’ and ‘k’ [4]

3. Results and Discussion

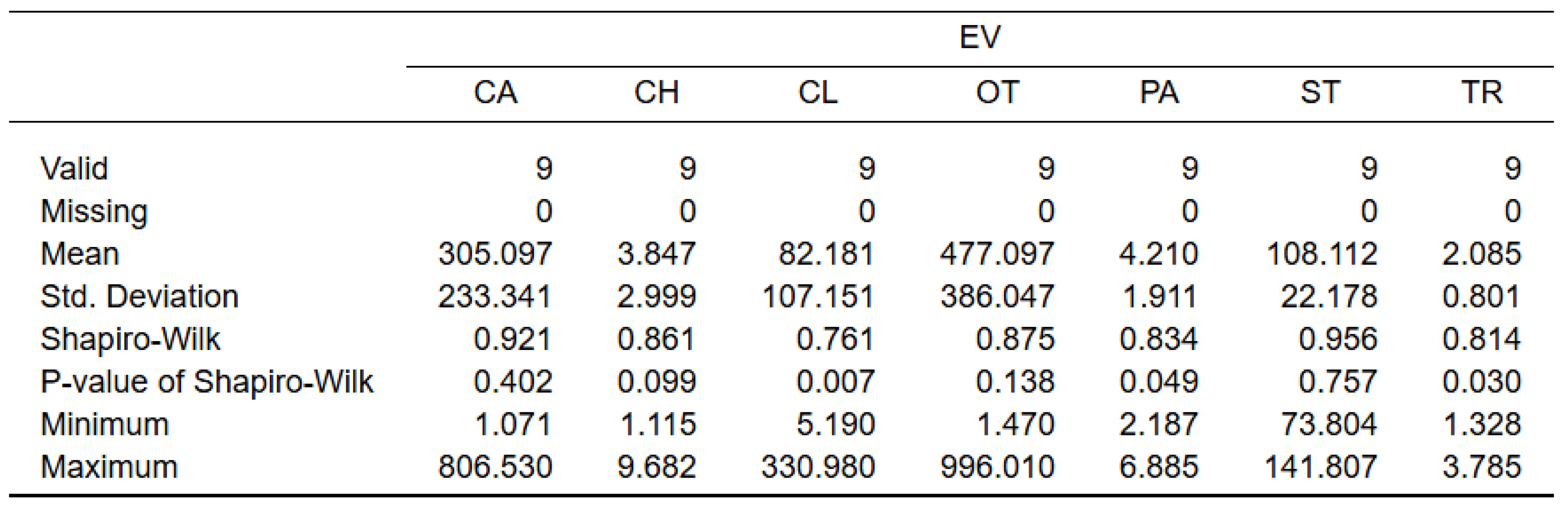

Table 7 shows the measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation, range) for each product in each region. In this respect, the economic value of the production of swan timber, caps, chopsticks, and other products derived from wood follows normal distribution, as shown by the p-value of Shapiro-Wilk (p > .005) (

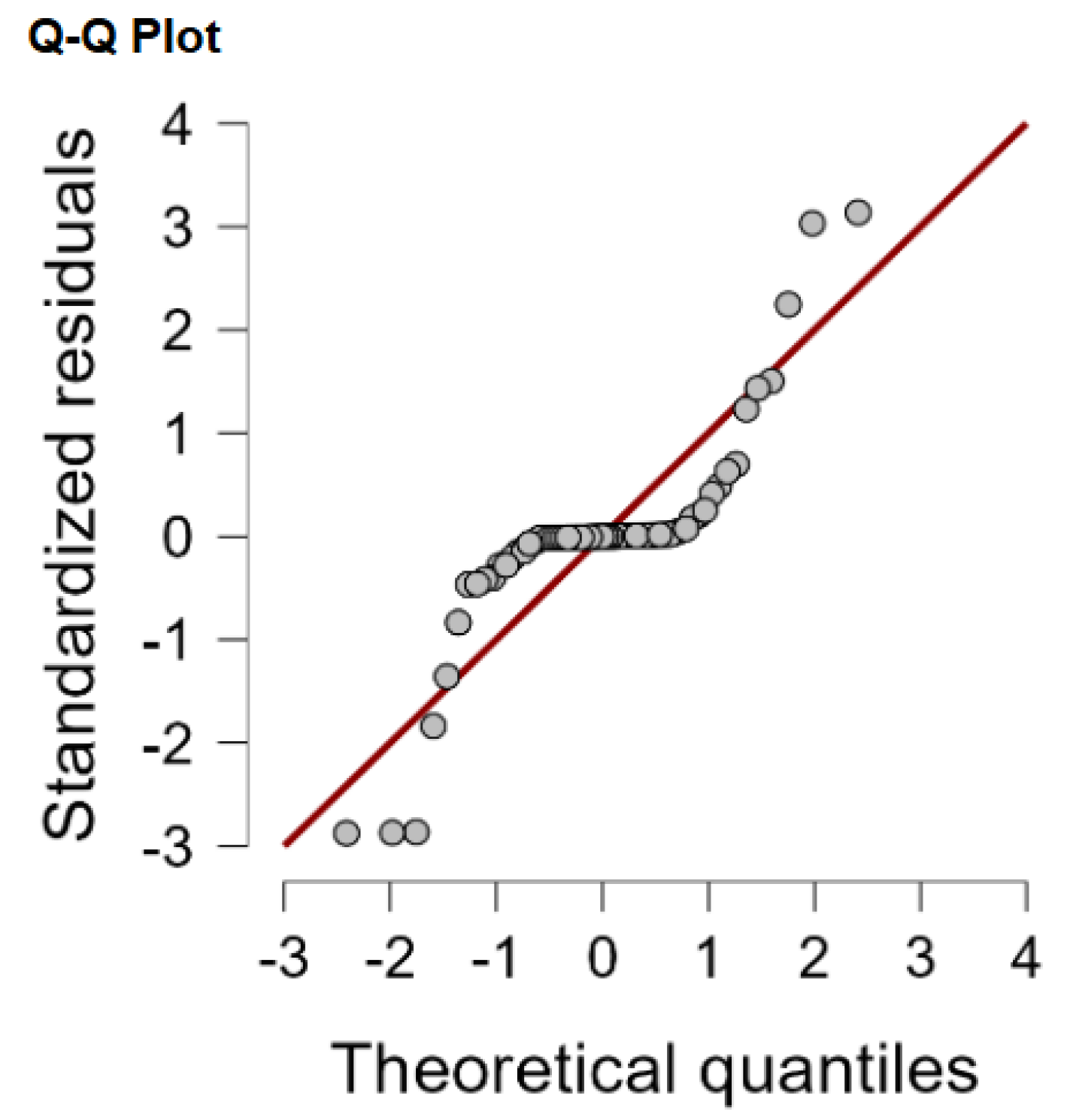

Table 1). As not all products analyzed follow a normal distribution, non-parametric analyses will be applied. Also, the Q-Q Plot (

Figure 1) shows that the residuals do not follow normality.

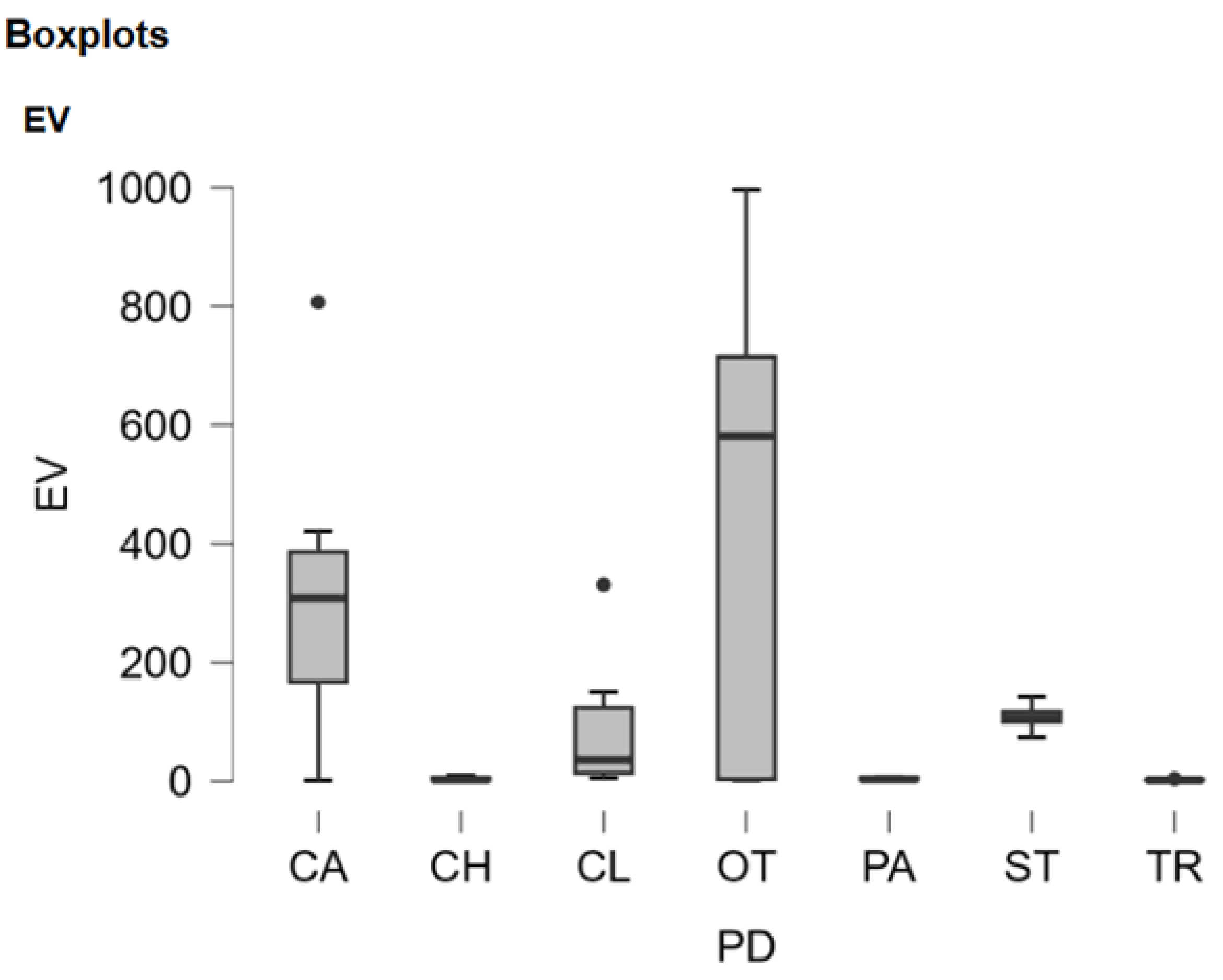

Figure 2 shows the distribution characteristics of each wood product, including their central tendency, dispersion, and outliers.

As in the test for equality of variances (Levene's), the p-value is less than .05 (

Table 8), at least one of the groups' variances is significantly different from the others, so the homogeneity of variances (heteroscedasticity) is not met. As a result, we will apply Welch's ANOVA as an alternative to one-factor ANOVA, which assumes homoscedasticity in parametric tests.

As shown in

Table 9, the main result of the ANOVA is the p-value (<.001) associated with the F statistic, which is very high because the differences observed between the means of the different groups are broadly significant compared to the dispersion of the data within each group. This result means that there are significant differences between the means of at least two of the products being compared.

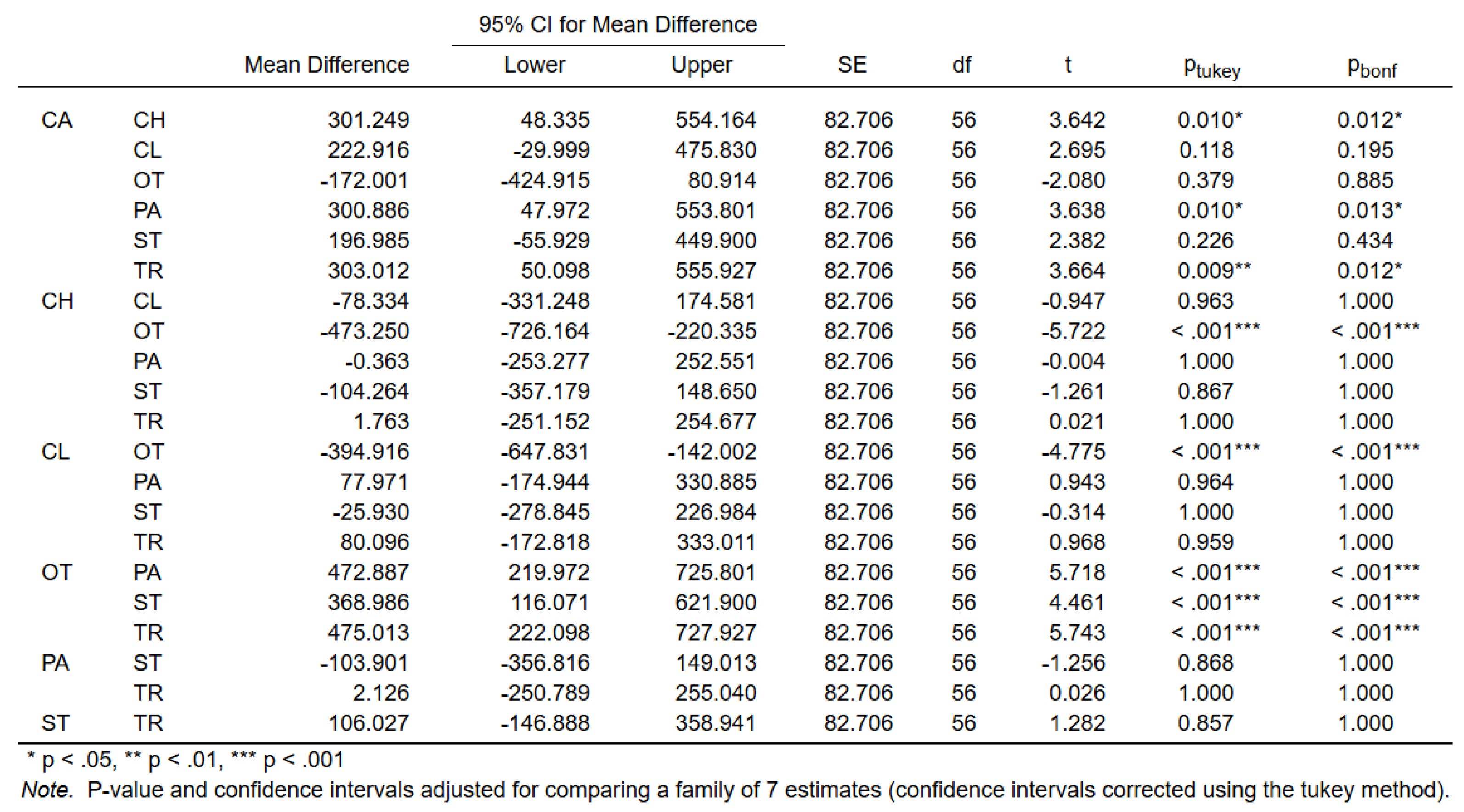

The importance of these differences is given by ω2. It shows that 45.6% of the variability of the dependent variable is due to differences between the groups defined by the independent variable. The rest (54.4%) is attributed to other factors, such as individual variability within groups or measurement error. To identify which specific groups are significantly different from each other, we will perform Tukey's post-hoc tests, since the sample sizes are equal, and Bonferroni tests to adjust the significance level for multiple comparisons.

The results of the Tukey HSD (Honestly Significant Difference) and Bonferrati post hoc tests are statistically significant in the relationships between the other wood products and the rest of the wood products, except sawn timber, as well as in the relationships between caps and chopsticks, pallets, and traps. These relationships show an interdependence between all wood-based products, demonstrating no significant differences in the mean quantity produced between the seven wood products, given that all waste generated in the sawing process is used, minimizing waste generation. As a result, hypothesis H0 is accepted.

However, the primary forestry industry in Honduras' use of wood products is far from ideal. This leads us to propose a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats)-CAME (Correct, Adapt, Maintain, Exploit) analysis summarized in

Table 11.

Most of Honduras' primary forestry industry, which includes sawmills and plywood plants, is located near forest resources. The sawmill production of coniferous and broadleaf forest species is a fully developed commercial business that has sustained a log export industry for many years. However, the primary industry has problems reducing costs. One of the main realities is that the domestic primary industry produces at a high cost, perhaps because its industries do not operate at full capacity due to the existence of obsolete machinery that breaks down frequently, which is estimated to be used at 50% of its capacity, raising production costs and creating inefficiencies that have not been corrected.

The primary forestry industry in Honduras faces significant challenges, mainly due to illegal logging, estimated at between 75% and 85% of hardwood production, which translates into around 125,000 to 145,000 cubic meters, while softwood production experiences similar illegal rates of 30% to 50%, equivalent to 350,000 to 600,000 cubic meters per year. Deforestation threatens biodiversity and disrupts critical ecosystem services, such as water regulation and carbon sequestration. For example, converting forested areas to agricultural land or urban development has increased surface runoff and reduced infiltration rates, essential for maintaining water quality and availability. This rampant illegal activity is exacerbated by weak governance structures and insufficient enforcement of forestry regulations in Honduras, which hinder sustainable management practices and contribute to significant deforestation. The ecological implications of illegal logging in Honduras are profound.

The forestry industry in Honduras is poorly diversified and relies exclusively on solid wood. Most primary industries consist of sawmills with very little value-added activity and an incipient processing industry for value-added products. Most of the primary industry is in the pine forests of Francisco Morazán, Olancho, and Yoro, with a smaller presence in Comayagua and Cortés. The low economic returns from forests are due, among other things, to the following causes: 1) Legally and sustainably produced timber competes in the market with timber from illegal logging and/or deforestation, due to weak enforcement of forestry legislation; 2) Complex technical processes, delays, and administrative fees increase the transaction costs of forest licensing and approval processes; 3) Private owners and communities pay “use rights” for standing timber, even on their land. Often, the public forest administration, which is understaffed, under-equipped, and underfunded, depends on these fees to sustain its operations.

According to the statistical review from 2014 to 2024 regarding production, apparent consumption, exports, and imports, the primary forestry industry has performed well in recent years, except for the COVID-19 pandemic. Honduras' main customers and suppliers are in Central America, so given the process of globalization that requires commercial and financial contact between countries for trade purposes, it is necessary to train the country's forestry entrepreneurs and/or producers to compete adequately and reduce disadvantages with similar producers in other countries. At the same time, an efficient and competitive industrial plant needs to be developed to take advantage of Honduras' comparative advantages and promote a state policy that encourages, promotes, and strengthens the sector's development, among other actions. Short-term policy actions are needed to strengthen this industry, such as making the operating rules of forestry support programs more flexible, investing in the modernization of production facilities, and training the workforce.

4. Conclusions

The primary forestry industry in Honduras currently faces a complex range of challenges and opportunities influenced by socioeconomic factors, environmental conditions, and policy frameworks. The forestry sector plays a crucial role in the national economy, contributing to employment, income generation, and environmental sustainability. However, it is also beset by problems such as deforestation, illegal logging, and the need for sustainable management practices. Forestry in Honduras is an integral part of rural livelihoods, providing jobs and income to many communities. The sector has a significant direct and indirect impact on the economy, creating employment within forestry and related sectors such as agriculture and tourism.

By aligning the interests of various stakeholders, including the government, the private sector, and local communities, as well as public-private partnerships and cooperatives, it is possible to help create a more resilient and sustainable forestry sector. In terms of educational and professional development, there is an urgent need to transform forestry education to meet the changing demands of the industry. It is recognized that forest engineers are responsible for ensuring the management of natural resources by globally recognized principles of sustainability, as established in Honduran forestry laws. It is therefore important to recognize that employers in the public and private sectors must evaluate the job performance of professionals graduating from higher education institutions based on the quality and effectiveness of the product or service delivered.

Effective regulatory and governance frameworks are essential to combat these problems and promote sustainable practices within the forestry sector. In addition, the role of public-private partnerships in improving the forest economy is increasingly recognized. These collaborations can facilitate investment in sustainable forestry initiatives, improve resource management, and encourage innovation. Integrating sustainable forestry practices is essential to increase these economic benefits while ensuring environmental protection. For example, sustainable forest management practices can improve forest health and productivity, boosting local economies.

Exploiting forest resources for industrial purposes can harm the environment if poorly planned. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the impact of forest industry activities on the environment, not to jeopardize other forest goods, services, and benefits. These benefits include improving climate patterns, providing clean air, protecting biological diversity, protecting watersheds, soil, and food crops, and providing recreational facilities. Promoting a sustainable forestry industry is a way to improve rural economies while meeting sustainability goals.

Future research will analyze the environmental, economic, and social challenges of the secondary forestry industry value chain in one of Honduras' forest regions. The aim is to understand the value chain's performance and the industry's and end consumers' management regarding sustainable development goals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, KYCN and JMSA; methodology, JMSA; formal analysis, KYCN and JMSA; writing—original draft preparation, KYCN; writing—review and editing, JMSA; supervision, JMSA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Research official data is open access and easily accessible online.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the anonymous reviewers’ invaluable comments and suggestions on this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Flores Rodas, J.G. (1998). El clúster forestal de Honduras: el reto de la competitividad. PROFOR/GTZ-Honduras.

- Triboulot, P. (2016). Le bois dans la construction: réflexions sur les évolutions probables et conséquences pour l’amont de la filière. Rev.. For. Fr., 58(2), 127-132.

- Raju Polchorel, S. I.; Alward, G.; Lamsal, B.; Poudel, J.; Dahal, R.; Joshi, O.; (…) Leefers, L. (2024). A Methodological Framework for Decomposing the Value-Chain Economic Contribution: A Case of Forest Resource Industries of the Lake States in the United States. Forests, 15(305), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Pratt, L.; Quijandría, G. (1997). Sector Forestal en Honduras: Análisis de Sostenibilidad. Centro Latinoamericano de Competitividad y Desarrollo Sostenible INCAE.

- Pomareda, C.; Brenes, E.; Figueroa, L. (1998). La Industria de la Madera en Honduras: Condiciones de Competitividad. CLACDS, INCAE.

- Segura Bonilla, O.; Arias Murillo, G. (2000). Proyecto Regional para el fortalecimiento institucional y desarrollo del sector forestal Guatemala, Nicaragua y Costa Rica. CATIE.

- Flórez, E.; Mairena, R. (2005). Diagnóstico de la situación forestal en bosque de pino en Honduras. Rainforest Alliance.

- Brandeis, C.; Hodges, D.G. (2011). Forest Sector and Primary Forest Products Industry Contributions to the Economies of the Southern States: 2011 Update. J. For, 113(2), 205-209. [CrossRef]

- López, N.; Muñoz, J. (2017). La producción forestal una actividad con alto potencial en el Ecuador requiere un cambio. Bosques Latitud Cero, 7(1), 1-8. https://scholar.google.hn/scholar?

- Kambugu, R. K.; Banana, A. Y.; Byakagaba, P.; Bosse, C.; Ihalainen, M.; Mukasa, C.; (…) Cerutti, P. O. (2023). The informal sawn wood value chains in Uganda: structure and actors. International Forestry Review, 25(1), 61-74.

- Markowski-Lindsay, M.; Brandeis, C.; Butler, B. J. (2023). USDA Forest Service Timber Products Output Survey Item Nonresponse Analysis. Forest Science, 69(1), 321-333. [CrossRef]

- Nutto, L.; Malinovski, J. R.; Castro, G. P.; Malinovski, R. A. (2016). Harvesting Process. En L. Pancel & M. Köhl (Eds). Tropical Forestry Handbook, 2363-2394. [CrossRef]

- Louman, B.; Stoian, D. (1992). Manejo forestal sostenible en América Latina: ¿económicamente viable o utopía? Revista Forestal Centroamericana, 25-32.

- Vallejo Larios, M. (2003). Gestión Forestal Municipal: Una nueva alternativa para Honduras. In L. Ferroukh, Gestión Forestal Municipal en América Latina (pp. 57-88). Lyes Ferroukh.

- ICF (2023). Anuario Estadístico Forestal de Honduras. http://www.icf.gob.hn.

- Hetemäki, L.; Hurmekoski, E. (2016). Forest Products Markets under Change: Review and Research Implications. Curr Forestry Rep, 2, 177-188. [CrossRef]

- Michal, J.; Brizina, D.; Safarik, D.; Babuka, R. (2021). Sustainable Development Model of Performance of Woodworking Enterprises in the Czech Republic. Forests, 12(672), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Larson, A. M. (2004). Democratic Decentralisation in the Forestry Sector: Lessons Learned from Africa, Asia and Latin America. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

- Golloway, G.; Kengen, S.; Louman, B.; Stoian, D.; Mery, G. (2005). Quince cambios en los paradigmas del sector forestal de América Latina. In G. A. Mery, Forest in the Global Balance – Changing Paradigms, 17, 1–35. IUFRO World Series.

- Larson, A. M.; Petkova, E. (2011). An Introduction to Forest Governance, People and REDD+ in Latin America: Obstacles and Opportunities. Forest, 2, 86-111. [CrossRef]

- Segura-Bonilla, O. (1997). Institutional Changes and Forestry in Central America. Researchgate, 1-22.

- Richards, M.; Wells, A.; Del Gatto, F.; Contreras-Hermosilla, A.; Pommier, D. (2003). Impacts of illegality and barriers to legality: a diagnostic analysis of illegal logging in Honduras and Nicaragua. International Forestry Review, 5(3), 282-292.

- Sánchez, M.; Navarro, G.; Del Gatto, F.; Sandoval, C.; Faurby, O. (2008). Análisis del comercio transfronterizo de productos forestales en Centroamérica. ResearchGate.

- Quesada-Pineda, H.; Haviarova, E.; Slaven, I. (2013). A Value Stream Mapping Analysis of Selected Wood Products Companies in Central America. Journal of Forest Products Business Research, 6(4), 1-13.

- Mendieta Durón, M. R. (2010). Potencialidad del sector forestal como facilitador del desarrollo humano sostenible. PhD Dissertation, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras.

- Flores-Velázquez, R.; Serrano-Gálvez, E.; Palacio-Muñoz, V.H.; Chapela, G. (2007). Análisis de la industria de la madera aserrada en México. Madera y Bosques, 13(1), 47-59. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, I.E.; Velásquez, I.; Villatoro, D. (2012). Explotación del sector forestal y su aporte al crecimiento económico de Honduras en el periodo 2002-2012.

- Nybakk, E.; Crespell, P.; Hansen, E. (2011). Climate for Innovation and Innovation Strategy as Drivers for Success in the Wood Industry: Moderation Effects of Firm Size, Industry Sector, and Country of Operation. Silva Fennica, 3(45), 415-430. http://www.metla.fi/silvafennica/full/sf45/sf453415.pdf.

- Ke, S.; Qiao, D.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Q. (2019). China's forestry and forest products industry has changed over the past 40 years, and challenges ahead. Forest Policy and Economics, 109, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Nedeljkovic, J.; Poduska, Z.; Krgovic, D.; Nonic, D. (2022). Critical success factors of small and medium enterprises in forestry and the wood industry in the Južnokučajsko forest region. Agriculture & Forestry, 68(1), 71-93. [CrossRef]

- Dayneko, D.; Dayneko, A.; Dayneko, V. (2021). Problems and Prospects of the Forest Industry Development in Russia: a case study of the Baikal region. E3S Web of Conference, 247, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Martinez, R. M.; Xu, Y.; Huang, A.; Duan, Y.; Ji, Z.; Huang, L. (2021). The spatiotemporal patterns and pathways of forest transition in China. Land Degrad Dev., 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R. (2022). Coupling and Coordination Relationship between Economic and Ecological-Environmental Developments in China’s Key State-Owned Forest Areas. Sustainability, 14, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Araya, R.; Guillaumet, A.; do Valle, Â.; Duque, M.; Gonzalez, G.; Cabrero, J.M.; … Castro, F. (2022). Development of Sustainable Timber Construction in Ibero-America: State of the Art in the Region and Identification of Current International Gaps in the Construction Industry. Sustainability, 14(1170), 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Pinnschmidt, A. (2024). Close-to-nature management of tropical timber plantations is economically viable and provides biodiversity benefits. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).