1. Introduction

The integration of autonomous driving technologies with electric and hybrid vehicles (EV/HEV) marks a transformative era in modern transportation. This convergence is driven by environmental concerns, advances in artificial intelligence (AI), and the evolution of sensor and system integration technologies. Autonomous electric vehicles (AEVs) not only promise reduced carbon emissions but also represent the pinnacle of smart mobility, combining sustainability with cutting-edge innovation [

1,

2,

3].

At the heart of AEVs lies a complex symbiosis of AI algorithms, sensor arrays, and integrated frameworks. Sensors such as LiDAR, radar, ultrasonic devices, and high-resolution cameras form the foundation of environmental perception, enabling vehicles to sense dynamic driving environments in real time. These sensor systems work collaboratively through sensor fusion techniques, employing Kalman filters, particle filters, and deep learning models to provide a coherent understanding of surroundings even when individual sensors have limitations [

4,

5,

6].

Sensor calibration and reliability under various environmental conditions remain key areas of ongoing research [

7,

8,

9]. AI serves as the cognitive engine of autonomous systems, interpreting sensor data to make context-aware decisions. Techniques like convolutional neural networks (CNN), recurrent neural networks (RNN), and reinforcement learning are widely applied to object recognition, lane detection, pedestrian tracking, and path optimization tasks [

10,

11,

12].

AI also facilitates intelligent navigation and high-level decision-making, enabling safe operation in both urban and highway environments [

13,

14]. Furthermore, real-time path planning and behavior prediction are enhanced through deep learning architectures [

15,

16]. Simultaneously, the integration of AI with electric drive systems improves operational efficiency. AI-powered battery management systems (BMS) monitor charge status and optimize charging cycles, thereby extending battery life and improving range estimation [

17,

18]. Predictive maintenance technologies powered by AI can forecast component wear and recommend timely servicing, minimizing downtime and repair costs [

19,

20]. System integration in AEVs is multifaceted, encompassing vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication, cloud-edge computing, and over-the-air (OTA) updates [

21,

22]. Internet of Things (IoT) frameworks enable real-time interaction between vehicles and infrastructure, supporting applications such as intelligent traffic routing and dynamic charging coordination [

23,

24]. AI-driven OTA platforms continuously upgrade in-vehicle systems, introducing new features and addressing security threats [

25,

26].

Modern AEVs also adopt co-design strategies for hardware and software, balancing computational load between central processing units and dedicated accelerators [

27,

28]. Vision-based systems utilizing OpenCV and embedded platforms achieve high levels of automation while reducing costs [

29,

30]. Simulation and digital twin environments are increasingly used to evaluate autonomous vehicle behavior under various driving scenarios [

31,

32]. Despite substantial progress, major challenges remain. Ensuring robust performance in adverse weather, achieving real-time multi-sensor data fusion, resolving ethical dilemmas in decision-making, and complying with diverse regulatory frameworks continue to be critical areas of concern [

33,

34,

35,

36].

The dynamic nature of AI also raises issues of explainability, reliability, and safe integration into traditional vehicle platforms [

37,

38]. Lastly, public acceptance of fully autonomous EVs and the legal liabilities associated with them must be addressed in tandem with technology deployment [

39,

40]. In response, the research community is developing next-generation AI algorithms tailored for heterogeneous environments, with a focus on generalization, energy efficiency, and multi-agent coordination [

41,

42]. Cross-disciplinary collaboration is also fostering innovations that unify perception, localization, and planning into cohesive software stacks [

43,

44,

45].

This paper explores the technological foundations of autonomous driving in electric and hybrid vehicles, reviewing key developments in sensors, AI algorithms, and system integration. Through a comprehensive survey of current research and industrial practices, we aim to highlight state-of-the-art solutions, identify existing bottlenecks, and propose potential pathways for future advancement in the AEV domain.

2. Technological Synergy Between EV/HEV and Autonomous Driving

As the automotive industry evolves toward autonomy, electric and hybrid vehicles (EV/HEV) have proven to be the ideal platforms to support the advanced requirements of autonomous driving technologies. The synergy between these two fields is not just coincidental; it is driven by technological needs and the increasing demand for smart, sustainable, and reliable mobility solutions. In this chapter, we will explore how EV/HEV platforms overcome the challenges posed by traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles and offer substantial advantages for autonomous driving systems.

2.1. Overcoming ICE Limitations with Electric Vehicles

Electric vehicles are uniquely positioned to address several key limitations of traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, especially in the context of supporting autonomous driving systems. One of the primary advantages of EVs is their ability to provide sufficient, constant, and reliable power for the complex network of sensors, computing units, and AI algorithms required by autonomous vehicles (AVs). Unlike ICE vehicles, which have smaller electrical systems that are often inadequate to power the increasing demands of autonomous driving technology, EVs are designed with large-capacity batteries that deliver the necessary power for continuous sensor operations.

EV batteries not only provide ample power but also ensure that these systems remain operational for extended periods, an essential feature for autonomous vehicles that need to run continuously without interruption. For example, LiDAR sensors, cameras, radar systems, and AI computing units need to process massive amounts of data in real-time to make driving decisions. In traditional ICE vehicles, power fluctuations and energy limitations often lead to interruptions or decreased performance of these systems, particularly when the engine is not running, or when the vehicle is idling [

46].

Conversely, electric vehicles overcome this limitation with a consistent, stable energy source. The high capacity of EV batteries ensures that sensors and computational systems are powered continuously, making EVs more suitable for the increasingly complex requirements of autonomous driving. Additionally, the regenerative braking system in EVs can help to optimize energy use and reduce the burden on the vehicle’s battery, further enhancing the overall efficiency of the AV system.

2.2. OTA Updates and Their Role in Autonomous Driving

Another crucial advantage of electric vehicles in the context of autonomous driving is their ability to seamlessly integrate over-the-air (OTA) updates. As autonomous driving systems rely heavily on continuous software updates to improve their performance and safety, the ability to conduct these updates remotely is essential. Electric vehicles, with their always-on power systems, provide the ideal platform for this functionality.

The architecture of electric vehicles allows for uninterrupted operation of communication systems, which is a fundamental requirement for OTA updates. The powertrain’s design ensures that the vehicle can remain connected to the network while being charged, enabling the software updates that are essential for the continuous development of autonomous driving features. The vehicle’s charging status is integrated with the cloud-based system, allowing for remote updates of sensor calibration, AI algorithms, navigation maps, and safety features without the need for the vehicle to be physically serviced [

47].

In contrast, internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles face significant barriers when it comes to implementing OTA updates. The reliance on mechanical systems such as the engine and transmission means that many ICE vehicles cannot perform updates while the vehicle is in operation. Furthermore, many existing ICE vehicles do not have the robust communication systems required to support OTA functionality efficiently. As a result, the inflexibility of ICE vehicles limits their capacity to adopt the continuous development required for autonomous driving. For example, to enable software updates in ICE vehicles, the engine must often be running, and the system must be active. This is not only inconvenient but also impractical in many scenarios, such as when the vehicle is parked or when the engine is not running [

48].

The ability of electric vehicles to conduct these updates without such restrictions provides a significant advantage in terms of convenience, safety, and technological advancement, ensuring that autonomous driving systems can evolve continuously in response to new challenges and regulatory requirements. OTA capabilities make it possible for vehicles to be upgraded automatically, reducing downtime and enhancing user experience [

49].

2.3. Electric Drivetrain and Gearbox Technologies for Autonomous Execution

The electric drivetrain and transmission systems in electric vehicles provide a critical advantage for autonomous driving. In autonomous driving systems, execution involves three main components: perception, planning, and control. Perception refers to the ability of the vehicle to sense its environment, planning is the decision-making process about how the vehicle should behave, and execution is the translation of these decisions into physical actions, such as steering, braking, and acceleration. A smooth and efficient execution phase is essential for the reliable operation of autonomous vehicles.

Electric drivetrains offer several key benefits for the execution phase of autonomous driving. The primary advantage lies in the simplicity and responsiveness of electric motors. Unlike the mechanical complexity found in internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, electric motors provide immediate torque, which enables smooth, precise control over the vehicle's movement. This feature is essential for the smooth execution of complex maneuvers, such as lane changes, acceleration, and deceleration in response to real-time sensor data and environmental conditions [

50].

Moreover, the absence of a traditional gearbox in electric vehicles eliminates the need for complex gear shifting, which can introduce delays and inefficiencies in the execution phase. In ICE vehicles, the shift from one gear to another can cause a lag, making the vehicle less responsive to immediate environmental changes. This is especially problematic for autonomous driving, which requires real-time, precise responses to sensor data in dynamic driving environments. Electric vehicles, by contrast, utilize a single-speed transmission, which provides a direct and efficient transfer of power to the wheels, ensuring that the vehicle remains agile and responsive [

51].

This drivetrain advantage not only improves the overall driving experience but also enhances the safety and reliability of autonomous systems. With precise and rapid control over vehicle movement, electric vehicles are better equipped to handle the nuanced demands of autonomous execution, such as avoiding obstacles, adjusting speed for tight curves, and following intricate traffic patterns [

52]. Furthermore, electric vehicles' integration with AI-based control systems allows for optimal coordination between perception and action, improving overall system performance and reducing the risk of errors during execution.

2.4. Functional Safety Advantages of EV/HEV Architectures for ASIL-D Autonomous Systems

A critical yet often overlooked benefit of electric and hybrid electric vehicles (EV/HEVs) lies in their natural alignment with functional safety requirements, particularly under the ISO 26262 standard for automotive electronics. As autonomous driving systems evolve toward ASIL-D (Automotive Safety Integrity Level D) certification—the most stringent safety classification—vehicles must ensure continuous, fault-tolerant operation, especially in power supply design. EV/HEV platforms offer unique architectural advantages that address these requirements more effectively than traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) counterparts.

Modern autonomous systems rely heavily on centralized domain controllers and a distributed network of sensors, all of which must remain operational even during a partial failure. ISO 26262 mandates that critical systems such as perception units, decision-making modules, and actuator controls must be powered redundantly—meaning that in the event of a single power source failure, a backup system must seamlessly take over without performance degradation or system shutdown.

EV/HEV platforms inherently facilitate such redundancy through their integrated high-voltage DC-DC converters and auxiliary 12V battery systems. The dual power architecture enables simultaneous, isolated power delivery to intelligent driving domain controllers (e.g., NVIDIA Orin, Black Sesame A1000) and safety-critical sensors (LiDAR, radar, cameras). In practice, this allows for redundant power rails where the main controller operates from one source (e.g., high-voltage DC-DC) and the fallback is instantly handled by the 12V auxiliary battery in the event of a primary failure.

This dual-source power system is not only crucial for sensor uptime but also ensures that vehicle control units can maintain emergency braking, steering overrides, and fail-safe modes even during voltage drops, wiring faults, or short circuits. In contrast, ICE-based architectures typically rely on a single alternator-powered 12V system, which lacks the robustness needed for ASIL-D compliance without significant reengineering.

Moreover, the modularity of EV powertrains allows easier isolation of high-risk functions and enhances diagnostic coverage—another ISO 26262 requirement. By embedding independent power monitoring and control logic at the subsystem level, EV/HEV-based autonomous platforms can detect anomalies early, initiate predictive fault handling, and preserve overall system integrity in real time.

As such, the convergence of electrified powertrains and autonomous technologies is not merely a technological convenience—it is a safety-enabling necessity. The structural capabilities of EV/HEV platforms naturally align with the rigorous safety requirements of high-level autonomy, making them indispensable in the realization of reliable, certifiable intelligent mobility systems.

2.5. Future Prospects and Innovations

The combination of electric drivetrain technology and autonomous driving has created a new paradigm for the automotive industry. As more vehicle manufacturers turn their attention to electric and hybrid platforms for autonomous driving, we can expect continuous innovation in both fields. For example, the development of more advanced electric drivetrains with higher torque density, improved energy efficiency, and faster charging times will only enhance the capability of autonomous vehicles [

53].

Similarly, advancements in AI algorithms and sensor fusion technologies will further optimize the coordination between perception, planning, and execution phases. By improving the accuracy and reliability of environmental sensing, electric vehicles will be able to handle more complex and diverse driving scenarios, from urban environments with heavy traffic to rural roads with less infrastructure [

54].

In conclusion, the integration of EV/HEV platforms with autonomous driving technologies offers a comprehensive solution to the challenges of modern transportation. From providing a stable power supply for advanced sensor systems to enabling continuous software updates and ensuring precise control through electric drivetrains, EVs have become the ideal platform for autonomous vehicles. As technology continues to evolve, the synergy between these two fields will drive the future of intelligent mobility, creating safer, more efficient, and environmentally friendly transportation systems.

3. Characteristics of China's Autonomous Driving Landscape under Electrification

3.1. National Policy Support and Electrification as a Catalyst

China’s dominance in electric vehicle (EV) adoption—accounting for nearly 60% of global EV/HEV sales in 2024—has laid not only a technological but also a strategic infrastructure foundation for the advancement of autonomous driving (AD). Two cornerstone policies anchor this transformation: the New Energy Vehicle Industry Development Plan (2021–2035) and the Intelligent Vehicle Innovation and Development Strategy. These national strategies articulate more than just high-level aspirations—they establish quantifiable milestones (e.g., L4 autonomous deployment by 2030), assign responsibilities across ministerial agencies, and incentivize implementation by state-owned enterprises, private OEMs, and municipal authorities [

55].

Central to these policies is the concept of electrification as a platform, not merely a drivetrain shift. The EV platform’s high-voltage architecture provides consistent power delivery for computation-heavy tasks like real-time perception, HD map processing, and vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication. This is particularly critical in China’s urban settings, where AVs operate in congested, multi-agent environments requiring fast sensor fusion and ultra-low-latency control loops [

56].

In contrast, internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles present energy management limitations. Their fluctuating power availability, especially at idle or during engine-off states, cannot sustain the performance demands of Level 3+ autonomous systems. Electric vehicles, by integrating large-capacity batteries with digital inverters and advanced electronic control units (ECUs), enable continuous operation of LiDAR arrays, millimeter-wave radar, multi-camera arrays, and AI accelerators—the essential stack of modern autonomous platforms.

Furthermore, China’s electrification rollout is not isolated. It is coordinated with infrastructure upgrades such as 5G V2X corridors, autonomous driving testing zones, and smart energy grids, reinforcing the link between electrification and autonomy. For instance, Beijing’s Yizhuang Zone and Shanghai’s Jiading Pilot Area feature electrified roads equipped with edge-computing roadside units that communicate directly with EVs, creating real-time urban driving simulations.

Therefore, electrification in China is not simply a facilitator of AV development—it is the foundational enabler. It provides the energy, architecture, and policy coherence required for scalable, commercially viable L3-L4 autonomous systems.

3.2. Investment Landscape and Startup Ecosystem: A Global Front-Runner

From 2018 to 2024, China absorbed more than RMB 120 billion (approximately USD 16.5 billion) in investment across the autonomous driving (AV) value chain, placing it ahead of the European Union and positioning it on par with the United States in terms of AV innovation funding [

56]. This capital has not been confined to a few high-profile firms—it has catalyzed the formation of over 500 startups, spanning full-stack autonomous solution providers, algorithm developers, AI chip manufacturers, sensor module designers, HD mapping vendors, and autonomous freight service providers [

57].

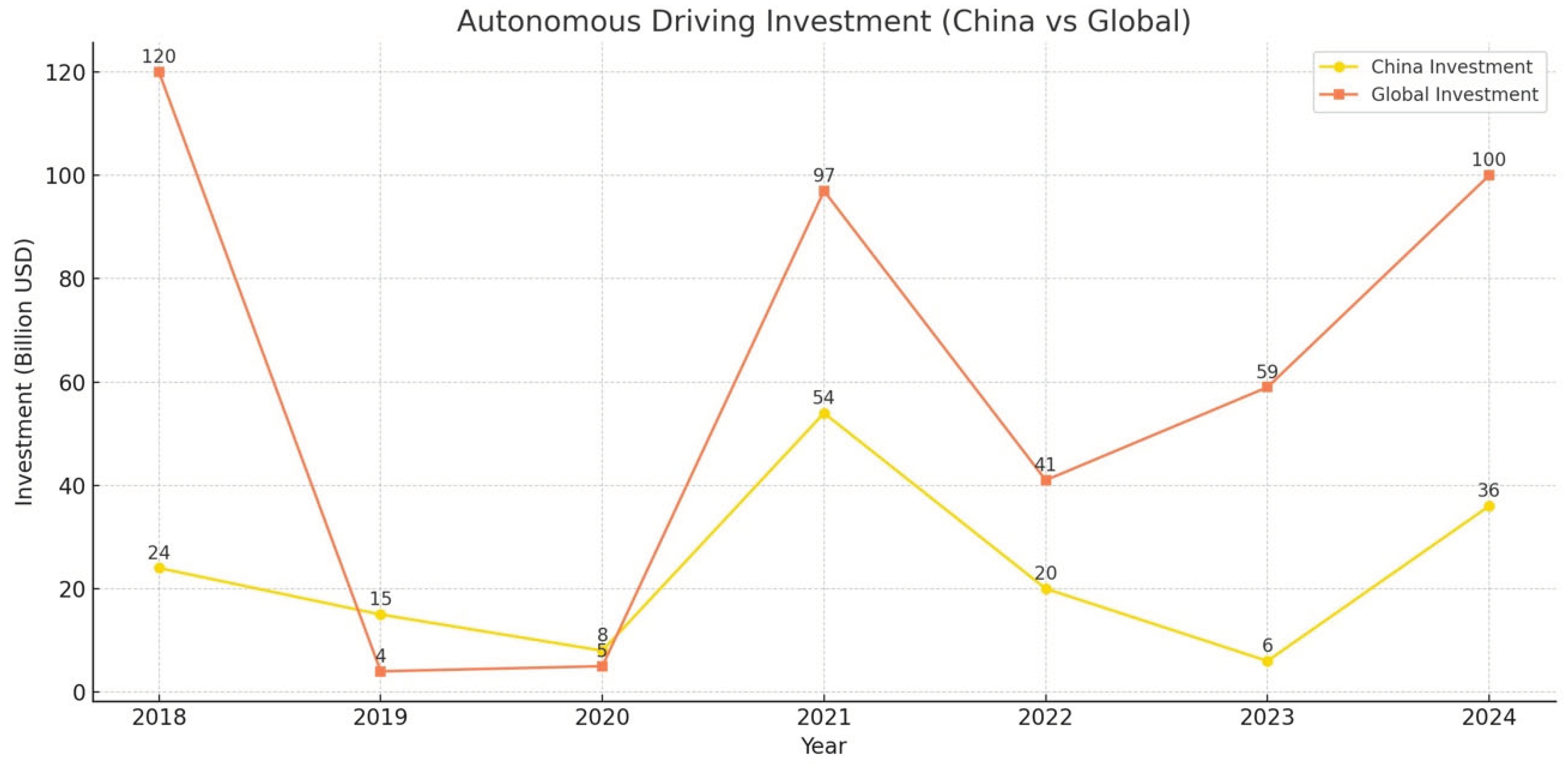

Figure 1.

Autonomous Drive Investment in China vs global*. *Data sourced from authoritative institutions including McKinsey, KPMG, Brookings Institution, iResearch, among others.

Figure 1.

Autonomous Drive Investment in China vs global*. *Data sourced from authoritative institutions including McKinsey, KPMG, Brookings Institution, iResearch, among others.

These investments are not random. They are guided by a state-industry coordination model. Central and provincial governments have established designated innovation parks—such as Shenzhen Pingshan Intelligent Vehicle Park, Hefei High-Tech Zone, and Jiading Intelligent Connected Vehicle Demonstration Area in Shanghai—which offer rent-free R&D space, corporate tax breaks, and subsidized access to closed-loop testing environments. These policy frameworks are designed to minimize time-to-market and reduce financial risk for startups, particularly in hardware-intensive areas like LiDAR calibration or AV compute modules [

58].

Flagship companies such as WeRide, Pony.ai, and DeepRoute.ai exemplify this high-velocity scaling strategy. Each has secured hundreds of millions USD in multiple funding rounds, with strategic investment participation from both local governments (via industrial guidance funds) and major OEMs such as Toyota, Dongfeng, and GAC. These companies advanced from algorithm prototyping to Level 4 pilot programs in Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Silicon Valley within 24–36 months of founding—demonstrating unprecedented speed.

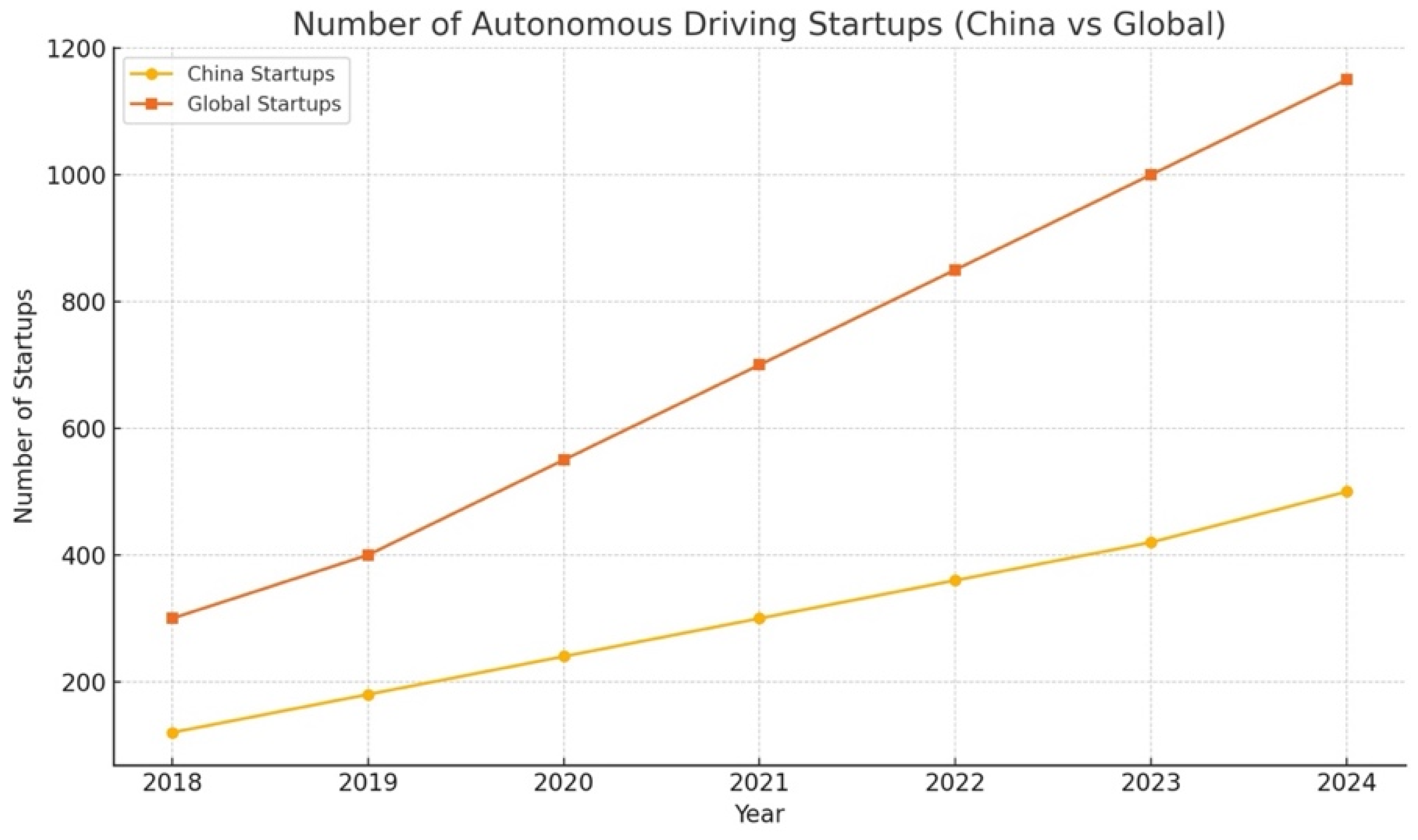

Figure 2.

Autonomous Startups in China vs Global.

Figure 2.

Autonomous Startups in China vs Global.

What distinguishes the Chinese AV startup ecosystem from its Silicon Valley counterpart is its early-stage structural alignment with public systems. Rather than operate in isolation, most Chinese startups enter strategic partnerships with SOEs (State-Owned Enterprises), transport bureaus, and digital infrastructure providers from the outset. For example, DeepRoute.ai works with the Shenzhen Transport Bureau on autonomous bus trials, while WeRide partners with Dongfeng Motor to accelerate the deployment of Robo-minibuses in designated corridors.

Moreover, AV capital is vertically integrated. AI chip firms (like Horizon Robotics) often co-invest with LiDAR manufacturers (like RoboSense), enabling better upstream-downstream hardware/software synergy and increasing ecosystem resilience. This industrial co-development model—where suppliers, startups, and public entities co-own pilot results—reduces duplication, enhances deployment speed, and ensures technological fit with China’s rapidly evolving regulatory and urban planning frameworks.

In short, China’s AV startup ecosystem reflects a hybrid model of venture dynamism + industrial policy discipline, producing fast-growing companies with real deployment footprints—not just unicorns chasing valuation headlines.

3.3. Proliferation of Sensor Manufacturers: From LiDAR to Ultrasonics

Sensors are the eyes, ears, and "intuition" of autonomous vehicles (AVs), providing the critical perception layer that enables navigation, object detection, and real-time decision-making. China, with its vast electronics manufacturing ecosystem, has rapidly transformed from a follower to a global innovation leader in AV sensor technologies:Lidar, Radar modules, HD cameras and Ultrasonic sensors.

LiDAR technology—once cost-prohibitive and bulky—has become commercially viable in China due to aggressive R&D and manufacturing scale. Companies like Hesai Technology and RoboSense have not only caught up with but outpaced legacy U.S. players such as Velodyne in terms of both unit shipment volume and system-level integration. By 2024, Hesai had delivered over 120,000 units, many integrated into production vehicles such as Li Auto’s L9 and Zeekr 001 FR, offering 360-degree horizontal field-of-view with multi-return and fog-penetration capabilities [

59].

These firms also lead in solid-state LiDAR and hybrid mechanical scanning units, optimized for cost-efficiency and robustness. Chinese OEMs increasingly adopt LiDAR not just in L4 Robotaxis, but also in premium L2+ and L3 consumer vehicles, marking a mainstreaming of advanced perception hardware.

Complementing LiDAR are millimeter-wave radar modules, typically operating in the 77GHz and 79GHz bands. As of 2024, over 70 Chinese radar startups are active in the sector, with companies such as Calterah Semiconductor, Maxieye, and ZongMu Tech achieving breakthroughs in in-house MMIC (Monolithic Microwave Integrated Circuit) design. These radars offer longitudinal object tracking, adaptive cruise control, and 4D imaging radar functions, essential for highway autonomy and lane-change planning.

Radar is also increasingly integrated with AI processors, enabling on-device fusion of speed, trajectory, and risk prediction, especially in multi-lane, multi-agent environments common in Chinese urban traffic.

The evolution of automotive-grade camera modules in China has been equally significant. Companies like SmartSens, OFILM, and Sunny Optical have repurposed their smartphone supply chain advantages to meet ADAS and AV-grade standards. Their products now rival Sony CMOS sensors in terms of resolution, low-light performance, and cost-efficiency. Modern camera systems include HDR (High Dynamic Range) sensors, global shutter arrays, and edge image signal processors (ISP) that preprocess visual inputs in real time. These are critical for traffic light recognition, pedestrian detection, and semantic segmentation, especially under complex lighting conditions such as tunnels or nighttime driving [

60].

Though often overshadowed by LiDAR and radar, ultrasonic sensors play an irreplaceable role in short-range maneuvering, parking assistance, and low-speed urban driving. In China, companies like INVT, JoyNext, and CanSemi mass-produce compact, low-cost modules capable of detecting objects within 0.3–5 meters. These sensors are essential for Robotaxi operations in constrained environments such as airports, underground garages, and last-mile delivery stations. Their simplicity, affordability, and robustness make them ideal for redundancy in sensor fusion frameworks, especially where visual occlusion or signal interference may occur.

Together, this multi-modal sensor landscape—built on China’s vertically integrated manufacturing capabilities—has positioned the country to deliver complete perception stacks that are cost-effective, high-performing, and scalable. These sensors are not developed in silos but co-engineered with chip vendors, algorithm developers, and OEMs to ensure seamless fusion, signal synchronization, and reliability under real-world driving conditions.

3.4. Rise of Algorithm-Centric AI Firms

Artificial intelligence (AI) serves as the computational and cognitive core of autonomous driving (AD) systems, transforming raw sensor data into actionable vehicle control decisions. In China, algorithm-centric firms are not only catching up with global peers—they are actively shaping the future of AV software stacks, particularly in the domains of perception, planning, and simulation.

Leading the charge is Momenta, whose VisionFusion platform utilizes a BEV (Bird's Eye View) transformer framework, combining multi-camera imagery into a unified spatial representation. This is paired with object detection through convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and trajectory forecasting via recurrent neural networks (RNNs). The company’s system supports urban lane following, unprotected left turns, and semantic localization, and is already deployed in over 100,000 vehicles, primarily through partnerships with SAIC Motor and BYD [

61].

Another major player, Pony.ai, takes a reinforcement learning (RL) approach. Its AV stack is trained in dynamic urban environments such as Guangzhou, Beijing, and Fremont (California), continuously adapting to local traffic idiosyncrasies. The system has demonstrated 96%+ perception accuracy in high-density traffic scenarios, excelling at multi-agent prediction and trajectory anticipation under occlusion and uncertainty.

Meanwhile, DeepRoute.ai is pioneering HD-map-free driving, addressing the scalability limitations of current AV mapping dependencies. Leveraging self-supervised learning techniques across over 5 million kilometers of real-world driving data, the firm has reduced reliance on high-definition prior maps, instead emphasizing on-the-fly localization and context-based planning—a crucial advancement for second- and third-tier city deployments where HD maps are often outdated or unavailable.

These firms are not just engineering-driven but also academically engaged. Their researchers and engineers frequently publish at top-tier conferences such as CVPR (Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition), NeurIPS (Neural Information Processing Systems), and ICCV (International Conference on Computer Vision). Recent contributions include work on:

Dynamic scene graph prediction for understanding pedestrian-vehicle interactions

Adversarial planning training to increase robustness against edge-case errors

Online multi-agent coordination networks, which allow AVs to negotiate merges, yields, and overtakes in dense traffic

Importantly, the algorithms developed by these firms are designed with Chinese traffic conditions in mind, including aggressive merging behavior, high pedestrian density, and heterogeneous lane usage (e.g., motorbikes sharing car lanes). This localized optimization contrasts with Western firms, which often focus on more structured urban layouts.

In addition, Chinese AV firms are integrating their software stacks directly with OEM production lines. For instance, Momenta’s ADAS algorithms are preloaded into vehicle ECUs during manufacturing, enabling a software-defined vehicle (SDV) model where features can be remotely activated or enhanced via OTA updates as new algorithms are validated.

Collectively, this cohort of algorithm-centric companies represents a technological and strategic asset for China’s AV industry—embedding intelligence not only into vehicles but also into the nation’s evolving mobility infrastructure.

3.5. Chip Ecosystem: From Emerging to Established

In the era of autonomous driving, compute power is as critical as horsepower—and China is rapidly building its own stack of AV-specific silicon to reduce reliance on foreign suppliers. Against the backdrop of the global semiconductor crunch, China has made the localization of intelligent driving chips a strategic priority. This push is backed by government initiatives such as the “Made in China 2025” plan, emphasizing autonomy in core automotive electronics.

Leading this transformation is Horizon Robotics, whose Journey5 SoC (System-on-Chip) delivers 128 TOPS (Tera Operations per Second) and is certified under ASIL-B safety protocols. Designed for both L2+ ADAS and L3 AV deployment, Journey 5 supports real-time data ingestion from up to 16 camera streams, along with radar and LiDAR fusion. The chip includes dedicated AI acceleration cores, image signal processors (ISPs), and fail-safe controls, making it suitable for production vehicles. As of 2024, it is already deployed in models by Chery, Dongfeng, Leapmotor, and increasingly in next-gen models from BAIC and Great Wall Motors [

62].

Another major player is Black Sesame Technologies, which specializes in domain controller-level AI computing for L3 and L4 systems. Its Huashan A1000 chip features heterogeneous compute architecture, with GPU, CPU, and NPU cores, and enables high-bandwidth processing for 3D semantic segmentation and BEV-based decision-making. Its positioning as a potential replacement for NVIDIA Orin makes it a key player for cost-sensitive OEMs that aim to reduce foreign chip dependency.

Emerging firms like Suiyuan Tech and Cambricon focus on AI coprocessors for edge inference, targeting mid-tier vehicles and dedicated computing modules for object tracking, lane detection, and driver monitoring systems. These chips are often optimized for low-latency, power-efficient inference, and can be embedded into sensor modules or vehicle gateways, enabling modular AI architecture for mass-market AV rollouts.

China’s chip ecosystem also benefits from cross-domain partnerships between silicon vendors, Tier-1 suppliers, and OEMs. Horizon Robotics, for instance, collaborates with Tier-1 integrators like Desay SV and Neusoft Reach to deliver plug-and-play computing platforms. These platforms combine hardware with preloaded ADAS algorithms, reducing integration time for car manufacturers.

Meanwhile, Chinese OEMs are pursuing dual-track chip strategies. Companies such as NIO and XPeng integrate NVIDIA’s Orin-X for flagship models, leveraging its 254 TOPS to enable L3+ features such as urban pilot, memory parking, and cross-floor valet. Simultaneously, they develop custom microcontroller units (MCUs) for real-time safety overrides, redundancy, and deterministic decision-making. This hybrid compute architecture ensures both cutting-edge performance and functional safety compliance.

From national-level incentives to deep vertical integration, China is laying the groundwork for a resilient, homegrown AV chip ecosystem. While international leaders like NVIDIA and Qualcomm still dominate high-end applications, Chinese firms are closing the gap, especially in cost-to-performance ratios, power efficiency, and regulatory compatibility. As the demand for localized AV compute intensifies, these domestic chip solutions will become central to China’s push for global autonomous driving leadership.

3.6. Diverse Technological Routes: China’s Strategic Pluralism

Whereas U.S. players often converge on singular tech stacks (e.g., Tesla’s camera-only or Waymo’s HD map-first), China encourages diverse approaches:

XPeng uses end-to-end transformer pipelines that predict motion from raw vision inputs.

Apollo (Baidu) adopts classical modular AV stacks, with layered perception, prediction, and planning modules.

DiDi utilizes simulation-first development with a focus on urban logistics and lane-level micro maneuvers.

Simulation ecosystems like CARLA, Alibaba DriveSim, and Tencent TAD allow thousands of corner-case scenarios to be tested virtually. This pluralism fosters rapid iteration and prevents ecosystem stagnation [

64].

3.7. Urban-Rural Disparities and Regional Innovation Hubs

China’s approach to autonomous driving (AV) deployment is distinctly regionalized and stratified, shaped by differences in urban density, infrastructure maturity, economic capacity, and policy autonomy. This urban-rural asymmetry has led to the emergence of multiple innovation hubs, each with specialized priorities and deployment strategies [

55].

3.7.1. Tier-1 Cities: Technology-Intensive Testbeds

Cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen serve as national-level experimental zones for advanced AV applications. These cities are equipped with:

High-density 5G-V2X corridors, enabling real-time vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communication

High-definition urban maps, updated frequently for localization precision

Dedicated AV testing areas, such as Beijing’s Yizhuang Pilot Zone, which spans over 100 km² and is embedded with edge AI units, Lidar-equipped traffic lights, and digital twin road models

Robotaxi fleets operated by Pony.ai, AutoX, and Baidu Apollo are running semi-commercially in these cities. These services operate under a hybrid model: Level 4-capable vehicles driven with safety drivers in place, with limited geographic and temporal freedom. In some zones of Shenzhen, select Robotaxi trials have fully removed safety operators, signaling a shift toward real-world autonomy.

3.7.2. Tier-2 Cities: Logistics and Freight Corridors

Cities such as Wuhan, Chongqing, and Hangzhou are emerging as freight-centric AV hubs, focused on autonomous trucking, highway platooning, and last-mile delivery. Wuhan’s AV Logistics Corridor, for example, connects inland ports with bonded warehouses using Level 3 autonomous trucks. These corridors are equipped with roadside units (RSUs) and smart toll gates, enabling coordinated vehicle scheduling and teleoperation fallback in emergencies. These cities also test AV buses and mini-shuttles in geofenced districts, especially in industrial parks, university campuses, and airports—offering real-world data while mitigating safety risks.

3.7.3. Rural and Low-Tier Cities: The Next Frontier

China’s rural zones and third-tier cities face challenges in AV readiness:

However, the central government has launched targeted subsidy programs under the Rural Digital Infrastructure Plan, encouraging AV companies to conduct low-speed logistics trials and postal delivery pilots in these regions. For example, JD Logistics operates autonomous delivery pods in county towns of Jiangsu and Sichuan, delivering parcels in areas where labor costs are high and vehicle density is low.

These environments serve as controlled testing grounds for sensor-light, AI-heavy systems that do not depend on high-resolution maps or infrastructure support. This helps push forward AV innovation for edge-case environments that urban AVs are not yet equipped to handle.

By orchestrating AV rollouts across this urban-rural gradient, China ensures a context-sensitive, tiered innovation model. Each city or region becomes a specialized lab, contributing localized data, public feedback, and regulatory insight to the national AV strategy. This dynamic accelerates both technical progress and regulatory preparedness across multiple scenarios, laying the groundwork for nationwide scalable autonomy.

3.8. Integration with Smart Infrastructure and OTA Platforms

Autonomous driving (AD) in China is not evolving in isolation—it is deeply embedded in the broader transformation of urban infrastructure toward smart, responsive, and interconnected systems. In this context, smart infrastructureserves as a digital scaffold, enhancing the perception, decision-making, and control capabilities of autonomous vehicles (AVs) through cooperative intelligence.

Leading cities such as Suzhou, Chongqing, and Wuxi have implemented full-spectrum vehicle-road-cloud (V2X) integration architectures. These systems allow AVs to communicate in real time with:

Smart traffic lights, enabling predictive stopping and acceleration

Pedestrian crossings, which transmit signals when in use or blocked

Emergency vehicles and priority lanes, which coordinate passage rules with AVs via cloud-edge systems

Suzhou’s Wuzhong District, for instance, has deployed over 200 roadside sensing units, enabling Level 4 AVs from firms like WeRide to coordinate with traffic management centers and dynamically re-route based on real-time congestion and construction alerts. This cooperative vehicle infrastructure system (C-V2X) reduces blind spots, minimizes latency in decision loops, and improves system-wide safety and efficiency [

56].

In parallel, AV software is evolving under the Software-Defined Vehicle (SDV) paradigm, where over-the-air (OTA) updates continuously enhance system intelligence post-deployment. Companies such as XPeng and NIO have developed cloud-native operating systems—Xmart OS and NAD (NIO Autonomous Driving), respectively—that integrate:

Real-time AI model training and deployment

Continuous HD map layer updates

Remote diagnostics and sensor calibration

Fleet-wide coordination using big data analytics and edge AI

XPeng, for example, pushes weekly OTA updates to improve performance in urban environments based on data collected from millions of kilometers of real-world driving. These updates can alter everything from path planning behavior to voice-assisted driving instructions, enhancing driver experience while upgrading AV capabilities without hardware changes.

These integrated SDV platforms are 5G-enabled, leveraging low-latency, high-throughput communication channelsto exchange vehicle-state data, road conditions, and AI inference results between edge units and cloud centers. The cloud component hosts simulation sandboxes, enabling “digital twins” of AVs to test new functions in virtual environments before real-world rollout—greatly reducing risk.

Together, the convergence of AVs with smart infrastructure and OTA/cloud ecosystems forms the backbone of China’s strategy to achieve safe, adaptive, and scalable autonomy. It ensures not only rapid responsiveness to edge cases(e.g., road obstructions, abnormal pedestrian behavior), but also provides the digital continuity needed to transform AVs into ever-evolving intelligent agents within the city fabric.

3.9. Industrial Alliances and Collaborative Platforms

The development of autonomous driving (AV) technology in China has become a deeply collaborative process, involving a vast network of technology companies, traditional automotive manufacturers, Tier-1 suppliers, academic institutions, and government agencies. Rather than rely solely on individual corporate breakthroughs, China’s strategy promotes platform-based industrial alliances, creating an open, co-evolutionary environment for AV innovation.

At the forefront of this effort is the Apollo Autonomous Driving Alliance, launched by Baidu in 2017. As of 2024, it includes over 200 partners, spanning automotive OEMs (e.g., BAIC, FAW, Geely), chipmakers (e.g., Horizon Robotics), cloud service providers (e.g., Alibaba Cloud), and local governments. Apollo offers:

Open-source perception and planning algorithms

High-fidelity simulation environments

Standardized hardware-software interfaces (Apollo Computing Unit - ACU)

Training data sets curated from multi-sensor fleets

Through Apollo, even smaller OEMs and regional integrators gain access to cutting-edge AV stacks without building them from scratch. The result is a modular, scalable AV development platform, reducing R&D costs and accelerating go-to-market cycles [

58].

Another prominent example is DiDi Autonomous Driving, which collaborates with state-owned FAW Group and SAIC Motor on large-scale Robotaxi operations. Their fleets share a standardized hardware configuration, featuring unified sensor placements, calibration protocols, and computing architectures. This enables consistent performance and streamlined maintenance across cities such as Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Suzhou.

Huawei, while not an OEM, plays a pivotal role as an infrastructure enabler through its Mobile Data Center (MDC)solution—a modular autonomous driving computing platform. Huawei’s MDC offers customizable SoC integration, cloud-edge communication modules, and functional safety isolation layers. It is already adopted by OEMs such as SERES, Arcfox, and Avatr, providing AV compute platforms that are compliant with China’s evolving cybersecurity and data localization regulations.

Industrial alliances also extend into mapping, simulation, and regulation:

NavInfo, AutoNavi, and municipal transport bureaus work together to deliver dynamic HD maps via open APIs.

Simulation platforms such as Tencent TAD allow AV firms to share digital twins and test thousands of virtual edge-case scenarios.

Joint testing centers, such as the China Intelligent Vehicle Innovation Center (CIVIC), enable pre-market safety validation aligned with Ministry of Transport standards.

These alliances function not only as technology accelerators, but also as risk-sharing consortia. By promoting standardization across sensor formats, control interfaces, and data exchange protocols, they minimize vendor lock-in and create cross-compatible AV ecosystems. This approach also deters monopolistic behavior, as it prevents any single company from controlling too many nodes in the AV value chain.

In summary, industrial alliances in China form a multi-tiered innovation fabric. They bind together R&D, policy, infrastructure, and commercialization in a way that lowers cost barriers, enhances deployment speed, and builds national competitiveness. The collaborative model not only strengthens the supply chain but also creates a resilient, scalable pathway for nationwide AV implementation.

3.10. Cross-Industry Integration and Platform Synergies

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) in China are increasingly viewed not as isolated mobility technologies but as integrated nodes in a national digital infrastructure ecosystem. The convergence of AVs with other smart systems—urban, industrial, and energy—reflects a strategic redefinition of the automobile as both a data terminal and an active agent in cyber-physical platform coordination.

3.10.1. Integration with Smart Cities

In smart urban planning, AVs are embedded into city-scale digital twins, enabling real-time coordination with traffic control, emergency response, and pedestrian flow systems. For example, in Hangzhou, AVs developed by Alibaba DAMO Academy and AutoX are connected to the city’s urban operating system, which ingests traffic sensor data, predictive analytics, and environmental inputs. Through V2I (Vehicle-to-Infrastructure) protocols, AVs receive signal phase timing, rerouting instructions, and congestion forecasts, enabling smoother traffic patterns and reduced idle emissions [

59].

AVs also serve as mobile sensing platforms, collecting data on road quality, air pollution, and urban heat zones. This real-time data feeds back to urban management platforms, enhancing city resilience and environmental planning.

3.10.2. Smart Energy and Grid Synergy

In the realm of smart energy, AVs—particularly EV-based autonomous fleets—are key actors in Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) systems. Companies such as NIO, in collaboration with State Grid Corporation of China, are piloting platforms in Shenzhen where idle autonomous EVs feed electricity back to the grid during peak demand hours, effectively becoming distributed energy storage units [

60].

These AVs operate within predictive load-balancing algorithms, which forecast grid usage and dynamically schedule charging and discharging cycles. This integration not only enhances energy efficiency but also supports China’s broader dual-carbon targets and renewable energy adoption goals.

3.10.3. Autonomous Logistics in Smart Manufacturing

AVs are also revolutionizing intra-factory logistics and supply chain automation in smart manufacturing contexts. BYD, for instance, deploys autonomous guided vehicles (AGVs) to transport battery modules within giga-factories, coordinating with robotic assembly lines through industrial 5G networks. Similarly, Haier’s COSMOPlat factory network uses AV-powered logistics platforms that synchronize with AI control towers for real-time material flow, fault detection, and inventory tracking [

61].

This AV-in-factory integration reduces labor costs, minimizes downtime, and enhances production precision—especially in multi-variant production models where flexibility is essential.

In summary, AVs in China are not simply tools of mobility but central actuators within a multi-domain digital ecosystem. By linking mobility with energy management, city operations, and industrial automation, China is positioning AVs as key infrastructure in its national smartization strategy. This cross-industry synergy not only maximizes ROI on AV investments but also lays the foundation for next-generation urban operating systems driven by AI and real-time data fusion.

3.11. Public-Private Innovation Models in Autonomous Driving

China’s approach to autonomous driving (AV) development is shaped by a hybrid governance model, which combines top-down strategic planning with bottom-up innovation. This model has proven highly effective in coordinating stakeholders, reducing institutional friction, and accelerating technological deployment in complex real-world environments.

3.11.1. Top-Down Policy Design and Regulatory Sandboxes

At the national level, ministries such as the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and the Ministry of Transport (MOT) issue broad frameworks that define AV classification standards (e.g., GB/T 40429-2021 for L0–L5), infrastructure integration guidelines (e.g., 5G-V2X rollout), and data security protocols (e.g., cross-border AV data storage restrictions). These policies are further operationalized through municipal-level pilot zones.

The most prominent example is the Beijing High-Level Autonomous Driving Demonstration Zone, launched in Yizhuang District. Covering over 60 km² and equipped with over 300 V2X-enabled intersections, the zone allows over 100 AVs from companies such as Baidu, Pony.ai, and WeRide to operate in real-world traffic with progressively fewer safety constraints. It provides AV-specific license plates, dynamic geofencing, and localized insurance pilots, making it a testbed for both technical and legal experimentation.

3.11.2. Bottom-Up Enterprise Innovation and Platform Co-creation

Private firms are not passive recipients of regulation but active co-creators of the AV ecosystem. Leading technology developers partner with academia and public research institutes to create joint research platforms. For instance, the Tsinghua-Pony.ai Joint Institute for Autonomous Driving develops industry benchmarks for perception accuracy, fail-safe planning, and traffic interaction behavior. These are shared across stakeholders via white papers and policy recommendations.

Local governments often provide policy credits and fast-track approvals to AV firms that relocate R&D or testing centers to designated areas. These incentives include:

Fleet licensing exemptions

Land use grants for data centers and simulation labs

Subsidized insurance frameworks for AV pilots Such measures reduce the cost and friction of deploying Level 3 and above autonomy systems, especially in public-facing contexts like Robotaxis and smart buses.

3.11.3. Collaborative Governance and National Platforms

Beyond bilateral partnerships, China is establishing multi-party governance platforms. The China Intelligent Connected Vehicle Innovation Platform (CICVIP), funded by the MIIT, brings together over 300 entities, including Huawei, SAIC, CATARC, and major universities. It serves as a central hub for:

Developing test protocols

Validating national datasets

Building shared simulation libraries This collaborative governance approach ensures interoperability, standardization, and public accountability, even as firms compete commercially.

In essence, China’s AV public-private innovation model reflects a "guided experimentation" paradigm, where central direction sets the vision, and local actors operationalize it through adaptive learning. This layered governance allows China to pilot policies, correct technical trajectories, and build legitimacy for AVs through stakeholder inclusion—paving the way for scalable and nationally coherent autonomous mobility solutions.

China has become the epicenter of autonomous driving innovation under the enabling umbrella of electrification. Its strengths lie not only in massive investment and market scale but also in its diversified strategies and resilient ecosystem. As technical bottlenecks like long-tail safety scenarios and regulatory variance are addressed, China is poised to shape the next global wave of autonomous mobility.

4. Future Challenges of Autonomous Driving in China

4.1. The Long-Tail Challenge and Delayed L4 for Private Owned Vehicles

While China’s AV sector has achieved commendable advancements in core modules such as perception, localization, and basic decision-making, the industry continues to face significant hurdles in resolving the “long-tail problem”—a term referring to rare, unpredictable, or anomalous driving scenarios that do not appear frequently enough in datasets to train AI models effectively. These include events such as roadside construction with ad hoc signs, children playing on the roadside, or animals entering a highway, all of which can cause unpredictable agent behaviors and require contextual reasoning far beyond current systems' capabilities [

66].

In particular, the long-tail issue is especially problematic for privately owned L4-level vehicles, which are expected to function without geofencing constraints or remote monitoring. Unlike commercial Robotaxi fleets that operate within tightly controlled environments and rely on remote human teleoperators when needed, private AVs must make autonomous decisions in dynamic, unstructured, and often poorly mapped environments, such as rural areas or older urban districts [

67].

Current reinforcement learning and simulation-based training pipelines have made progress in addressing edge cases, but behavior prediction in socially ambiguous scenarios—like whether a pedestrian intends to jaywalk—remains an unsolved challenge. AI models still struggle to infer intentions or contextual cues from subtle human behavior, which humans can interpret intuitively. Moreover, weather variability, such as heavy rain or snow, introduces additional perceptual noise, further compounding decision uncertainty.

Leading researchers and AV engineers suggest that true generalization for L4 autonomy may be a decade or more away, especially for use in privately owned vehicles without human fallback systems [

68]. Even in tightly geofenced commercial deployments, such as Robotaxi fleets in Guangzhou or Beijing, long-tail scenarios have caused unexpected system shutdowns or erratic behavior. These have, in turn, required frequent human interventions, undermining public confidence and commercial scalability [

69].

Consequently, while L4 systems for shared fleets in urban areas may scale incrementally, the rollout of L4-level autonomy for the consumer market—especially in unstructured, decentralized environments—is likely to be delayed until the long-tail problem is substantially mitigated through breakthroughs in generalizable AI, multi-modal prediction, and context-aware planning algorithms.

4.2. Commercial Scalability and Collapse of Chinese AV Startups

As China transitions from pilot deployments to large-scale commercialization of autonomous vehicles (AVs), the commercial scalability dilemma has emerged as a critical bottleneck, particularly for AV startups that flourished in the venture capital boom between 2018 and 2021. While early enthusiasm fueled massive investment rounds and rapid technical iteration, a combination of market overcapacity, uncertain monetization models, and inconsistent policy coordination has led to the collapse or stagnation of dozens of AV startups since 2022 [

70].

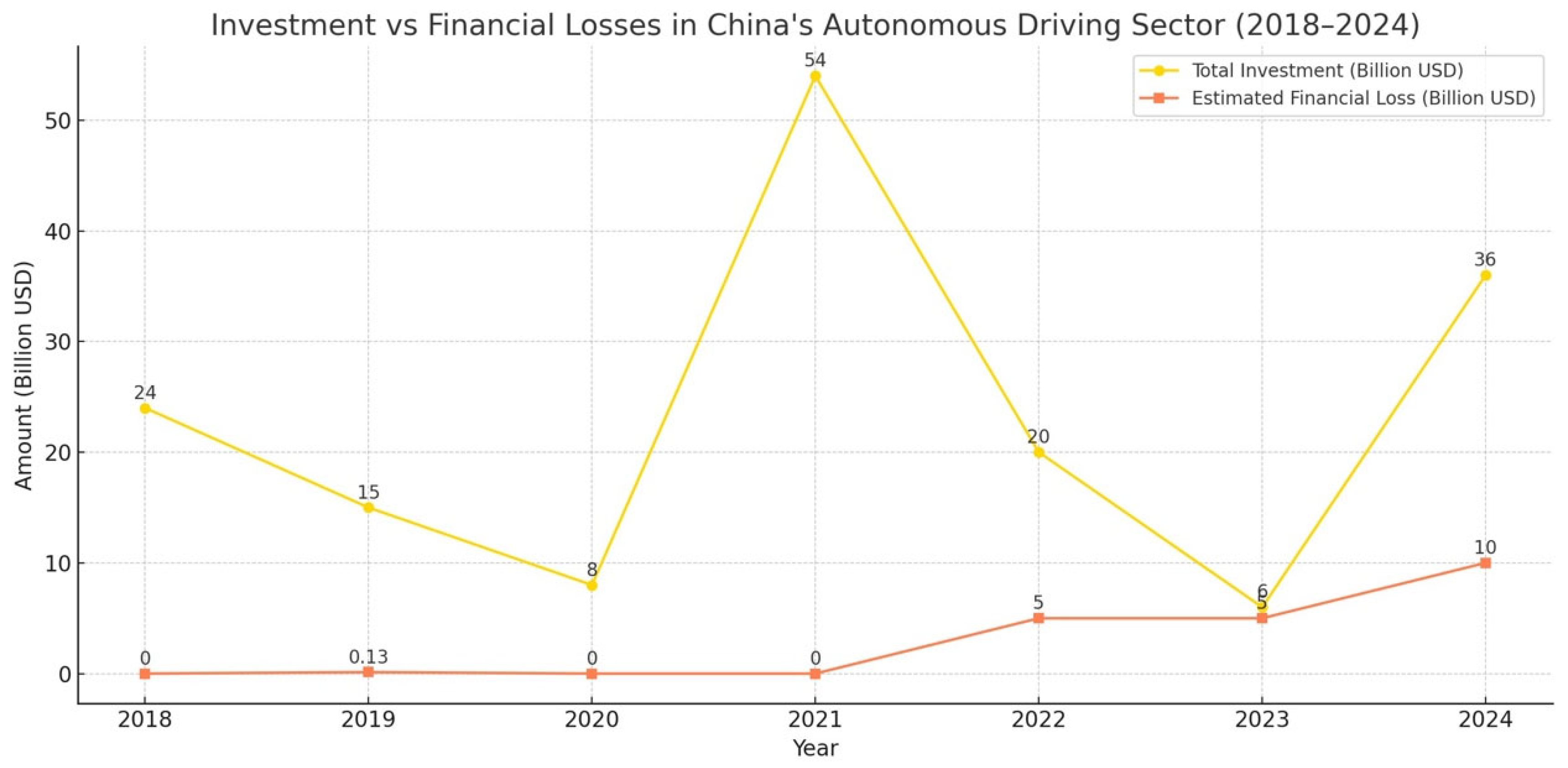

Figure 3.

Financial losses in China's Autonomous Drive*. *These data are sourced from authoritative institutions such as CCID Consulting and IT Juzi.

Figure 3.

Financial losses in China's Autonomous Drive*. *These data are sourced from authoritative institutions such as CCID Consulting and IT Juzi.

Many Chinese AV startups demonstrated impressive prototypes and simulation results, yet struggled to transition to profitable business models. Their core technologies often require high-end sensors and compute units that are costly and difficult to scale. Additionally, competition from OEMs with in-house R&D capabilities or partnerships with giants like NVIDIA has crowded the startup space.

Operating costs remain high for AV fleets, including remote monitoring, insurance, regular recalibration, and safety driver requirements. These factors limit profitability, especially in a market like China where ride-hailing fares are relatively low [

71].

The capital market has also cooled, with investment shifting toward generative AI and battery tech. Some AV startups have delayed IPO plans or shut down due to internal or market issues. Without alignment with evolving government regulations or the ability to scale quickly, many smaller AV players are exiting the market, consolidating the industry around a few major firms [

72].

This trend suggests that the future of China’s AV sector will be dominated by vertically integrated, well-capitalized firms capable of managing everything from AI chip design to full-stack autonomy deployment. Smaller players may survive only by focusing on niche applications, licensing software modules, or being acquired into broader technology ecosystems.

4.3. Safety and Social Acceptance in a Mixed-Traffic Society

In China’s urban environments, the coexistence of autonomous vehicles with traditional human-driven vehicles, pedestrians, e-scooters, and informal road users poses major safety and acceptance challenges. The unpredictability of traffic behavior, including jaywalking, informal signaling, and rule-bending maneuvers, makes consistent AV decision-making difficult. AVs often drive conservatively in these settings, leading to hesitancy, traffic disruption, or human driver frustration [

73].

Public trust is also limited. Surveys show that less than half of Chinese urban residents fully trust AVs, with concerns including AI errors, system hacks, and unclear liability in the case of accidents. High-profile incidents involving AV test vehicles have further fueled skepticism.

Efforts to address this include external human-machine interfaces (eHMI) that display AV intent, third-party safety audits, and public dashboards explaining AV decision logic. In districts like

Beijing Shunyi, local governments have initiated community engagement programs where residents are invited to observe AV testing and interact with engineers [

74].

In the long term, building social acceptance will require not only safer AV behavior but also transparent communication with the public, inclusive regulatory design, and demonstrable benefits such as reduced traffic deaths or cleaner air—benefits that must be clearly measured and widely publicized.

4.4. Ethical Governance and Data Sovereignty in the AV Era

As AV systems increasingly intersect with national infrastructure and citizen behavior, ethical dilemmas and data sovereignty concerns have come to the forefront. The lack of clear ethical decision-making standards—such as how to prioritize lives in unavoidable crash scenarios—has raised questions about the moral logic embedded in AV algorithms. Institutions like

Tsinghua University are working on guidelines, but most AV firms remain non-transparent in how these decisions are handled [

75].

On the data side, Chinese law mandates that AV data collected in domestic territory must be stored and processed locally. This applies to vehicle location, video footage, pedestrian biometrics, and driving behavior. Foreign firms must comply by establishing local data centers. These rules protect digital sovereignty but create challenges for global interoperability and AV export.

Furthermore, AVs collect data on bystanders and infrastructure passively, often without explicit consent. Without clear citizen opt-in mechanisms, the tension between innovation and privacy will grow unless transparent data governance frameworks are developed in parallel with technical deployment. To maintain public trust and regulatory stability, China must develop nationally unified ethical standards, improve citizen data rights, and build a multi-stakeholder AV governance framework that includes industry, government, academia, and civil society.

The promise of L4 autonomous driving remains compelling, yet its implementation is fraught with unresolved challenges. From the technical limitations posed by long-tail edge cases to the regulatory and societal hurdles of liability and trust, the industry must navigate a complex landscape.

Until these foundational issues are resolved, mass deployment — particularly in privately owned vehicles — will remain a long-term goal rather than near-term reality.