Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

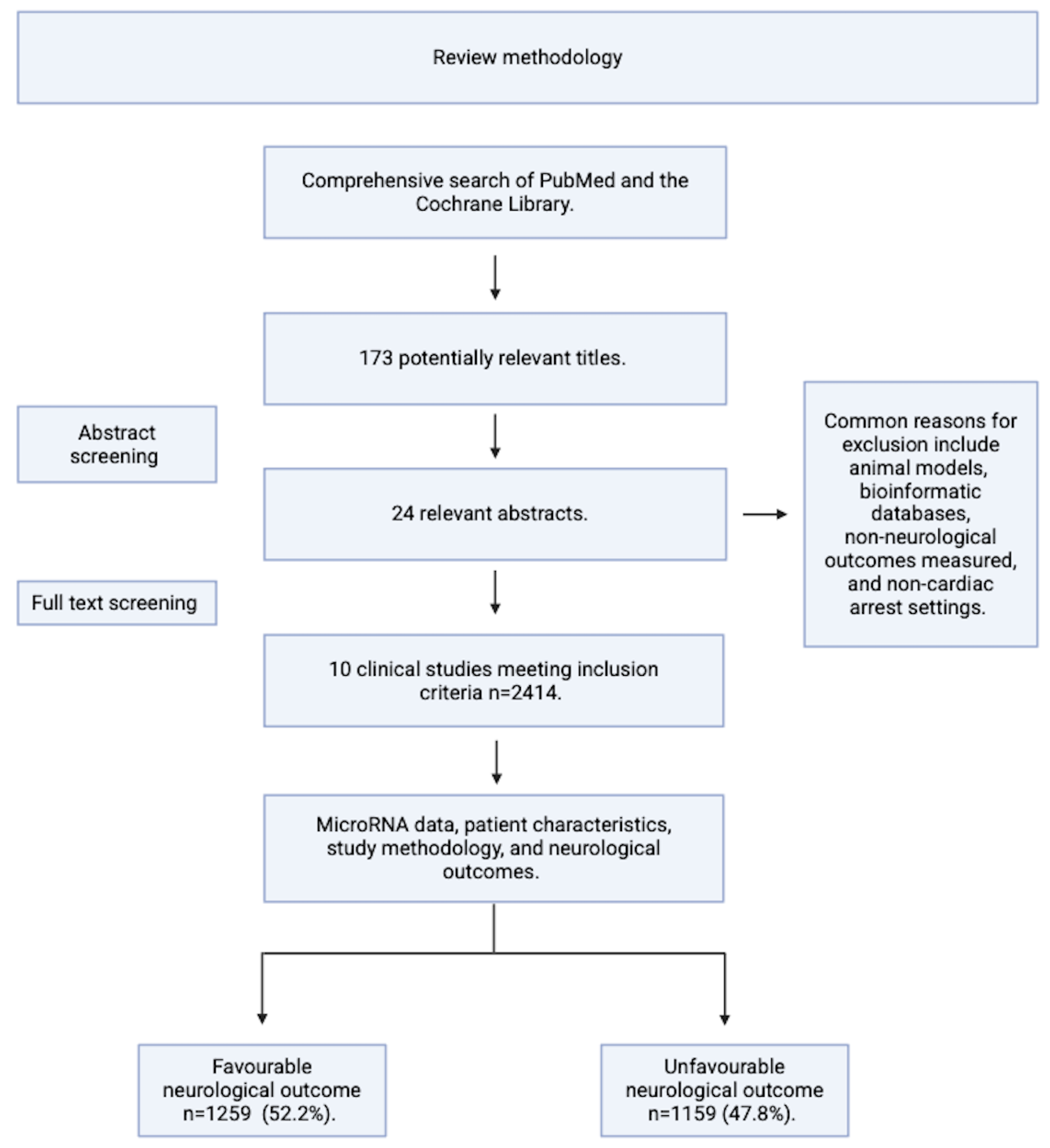

Methods and Aims

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Statistically significant results p <0.05 or FDR adjusted p value of <0.05 | Paediatric cardiac arrest. |

| Published in a peer reviewed journal since 1993*. | Bioinformatic/database driven research or animal models without original patients. |

| Written informed consent from the patient, the patient’s next of kin, or Doctor. | Post-mortem samples/ pathology analysis. |

| Appropriate quantitative methods for microRNA quantification e.g. microarray, polymerase chain reaction, or next generation sequencing. | Case studies. |

| Studies that obtained blood and quantified microRNA expression from patients who had either an in-hospital or out of hospital cardiac arrest within a defined period, either stated directly or deducible from the paper methodology. | Patients in which gene therapy/ gene editing treatments have been administered. |

Main Body

Included Studies and Patient Demographics

| Patients with an Unfavourable Neurological Outcome after Cardiac Arrest and ROSC (CPC 3-5). | ||||||

| Study Identifier | n | Age (years) | M % | F % | Bystander CPR (y %) | Time to ROSC (min) |

| 1 | 67 | 66 | 87 | 13 | 78 | 26 |

| 2 | 30 | 72 | 53 | 47 | 37 | 25 |

| 3 | 14 | 63 | 9 | 91 | n.a | 30 |

| 4 | 275 | 68 | 77.8 | 22.2 | 66.2 | 30 |

| 5 | 34 | 60 | 73.5 | 26.5 | 52.9 | 34.5 |

| 6 | 118 | 54.08 | 56.8 | 43.2 | n.a | 89.16 |

| 7 | 18 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a |

| 8 | 283 | 68 | 77.4 | 22.6 | 66.1 | 30 |

| 9 | 291 | 68 | 76.92 | 23.08 | 66 | 30 |

| 10 | 25 | 70 | 84 | 16 | 72 | 30 |

| Average | 64.45 | 66.15 | 33.85 | 62.6 | 29.43 | |

| Total | 1155 | |||||

| Patients with a Favourable Neurological Outcome after Cardiac Arrest and ROSC (CPC 1-2). | ||||||

| Study Identifier | n | age (years) | M % | F % | Bystander CPR (y %) | Time to ROSC (min) |

| 1 | 104 | 59 | 88 | 12 | 82 | 19 |

| 2 | 35 | 65 | 74 | 26 | 49 | 16 |

| 3 | 14 | 64 | 9 | 91 | n.a | 20 |

| 4 | 304 | 60 | 82.6 | 17.4 | 79.9 | 20 |

| 5 | 20 | 48 | 60 | 40 | 75 | 13 |

| 6 | 142 | 54.87 | 58.5 | 41.5 | n.a | 57.24 |

| 7 | 9 | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a | n.a |

| 8 | 307 | 60 | 82.7 | 17.3 | 79.5 | 20 |

| 9 | 299 | 61 | 83.9 | 16.1 | 81 | 20 |

| 10 | 25 | 62 | 84 | 16 | 76 | 20 |

| Average | 59.87 | 69.19 | 30.81 | 74.62 | 18.5 | |

| Total | 1259 | |||||

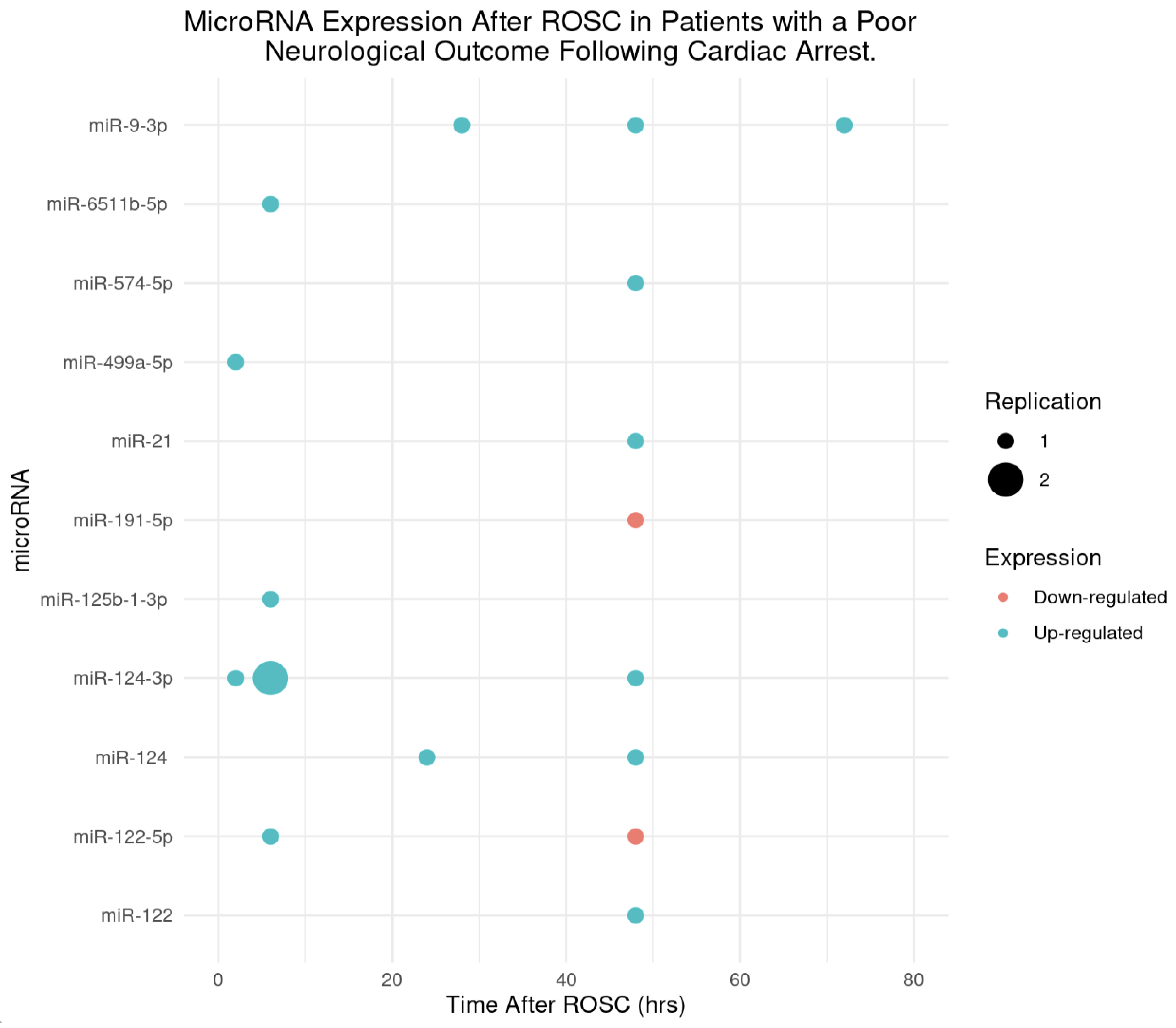

MicroRNAs and Their Expression Post-ROSC in Patients with an Unfavourable Neurological Outcome

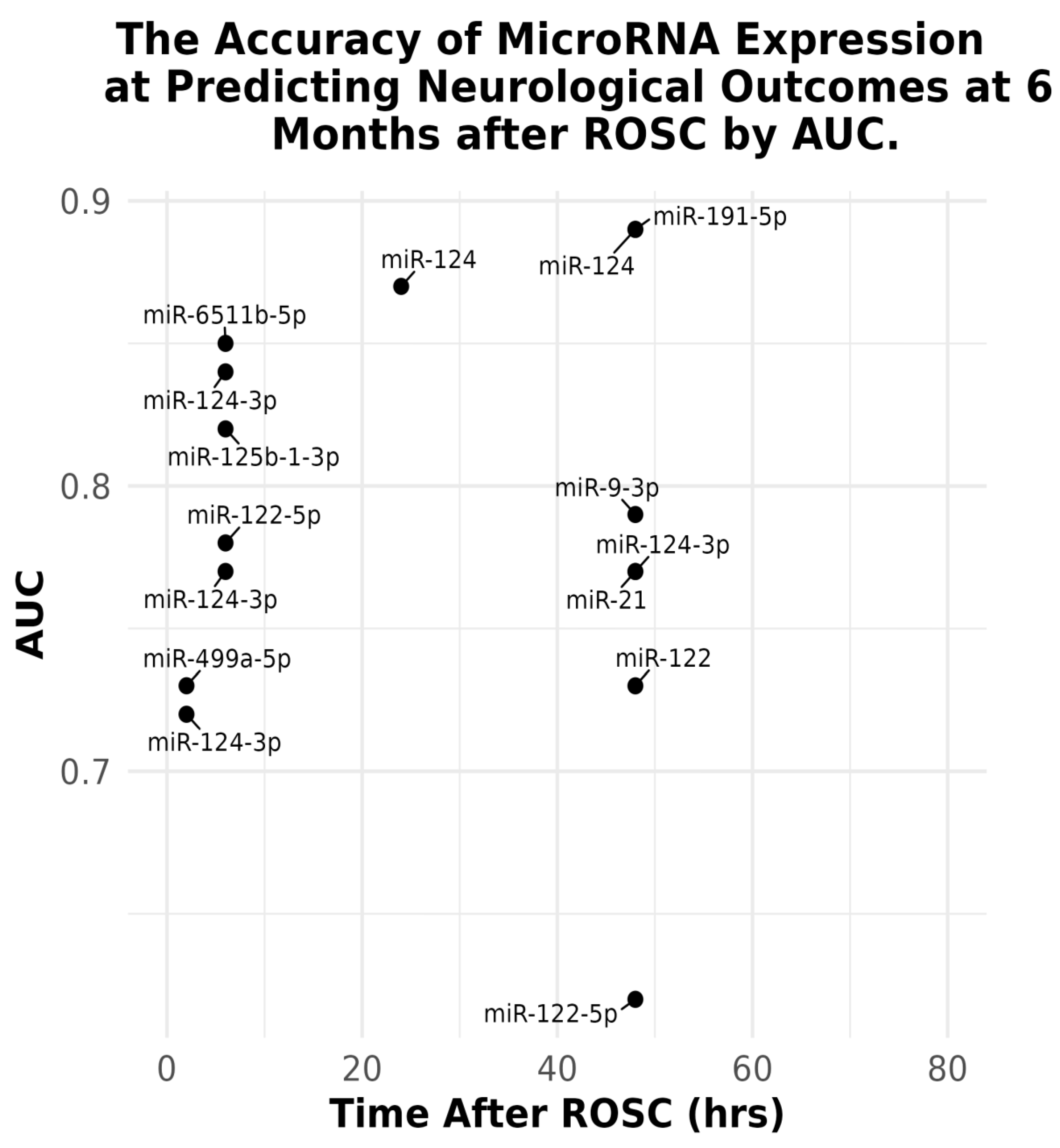

The Accuracy of Acute microRNAs Expression at Predicting Patient Neurological Outcome at 6 Months from ROSC

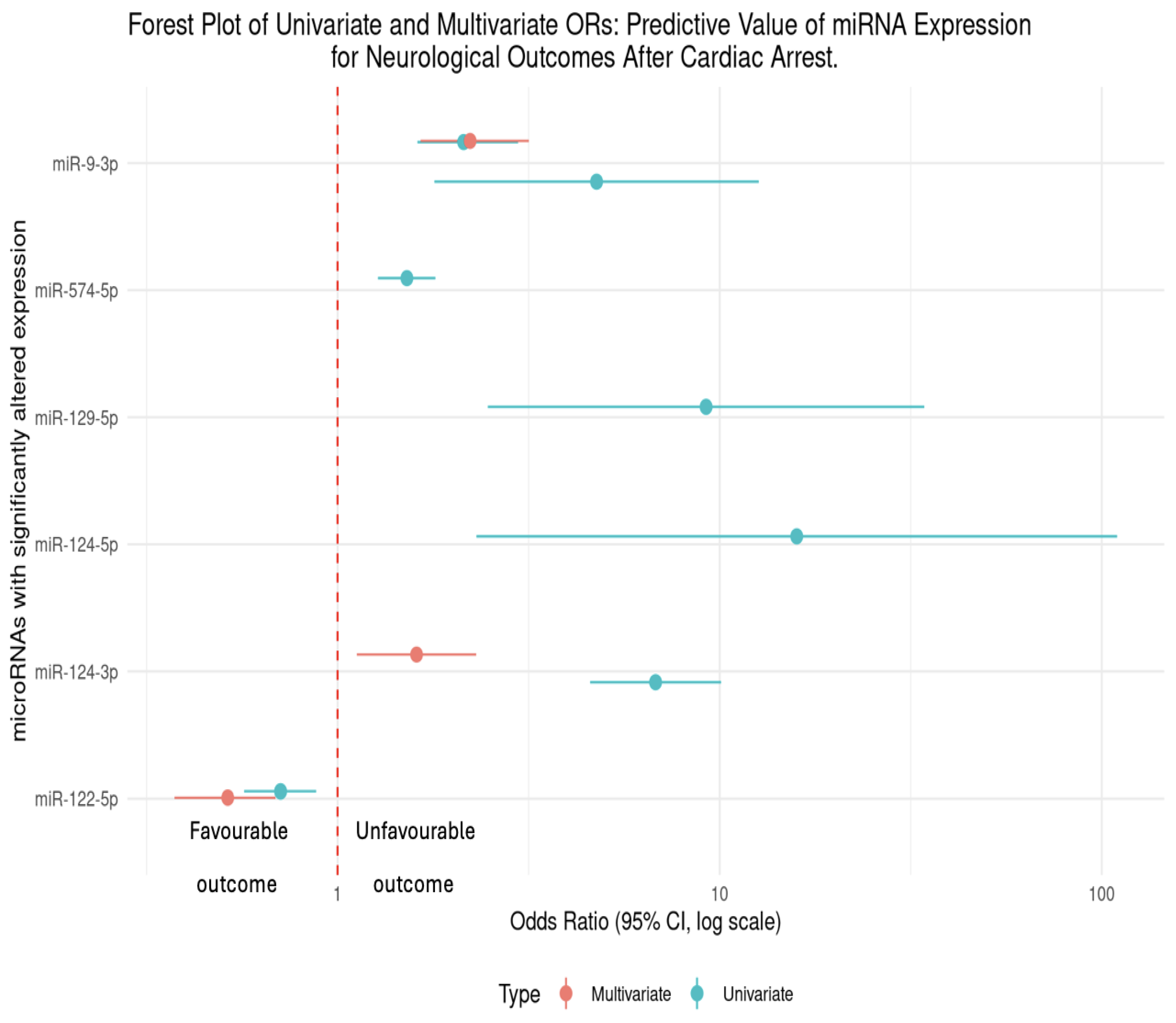

Significant Changes in Circulating microRNAs Mostly Predict Unfavourable Neurological Outcomes at 6 Months

Hazard Ratio (HR)

| Author / Year | Association between microRNAs after ROSC and Neurological Outcomes. |

| Beske et al 2022 | miR-9-3p was up-regulated at 48hrs post-ROSC. Univariate analysis revealed that patients in this study with elevated microRNA levels at 48hrs post-CA were more than twice as likely to have an unfavourable neurological outcome (OR = 2.14, 95%CI [1.62-2.97]), p<0.0001). From multivariate analysis, patients were twice as likely to have a poor neurological outcome with an elevated miR-9-5p (OR = 2.21, 95% CI [1.64-3.15]), p <0.0001). |

| Devaux et al 2016 | miR-124-3p which was up-regulated at 48hrs post-ROSC (p<0.001) found that patients with an elevated miR-124-3p were additionally at risk of an unfavourable outcome, which was quantified to be 6.72 times as likely (univariate OR = 6.72, 95% CI [4.53-9.97]). Following multivariate analysis, this unfavourable outcome was 1.6x as likely in patients with an elevated miR-124-3p (OR = 1.62, 95% CI [1.13-2.32]). |

| Devaux et al 2017 | miR-122-5p at 48hrs was found to be down-regulated (p<0.001) in patients with an unfavourable outcome. In univariate analysis, the odds ratio (OR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.57–0.88]) indicates that for each unit increase in miR-122-5p expression, the odds of a poor neurological outcome decreased by 29%. From multivariate analysis, the OR further decreased to 0.51 (95% CI [0.37–0.68]), suggesting a 49% reduction in the odds of an unfavourable outcome for higher levels of miR-122-5p.This demonstrates that higher miR-122-5p expression may have a neuro-protective effect following cardiac arrest. |

| Boileau et al 2019 | miR-574-5p was up-regulated at 48hrs (p<0.001). From univariate analysis, levels of miR-574-5p was a predictor of neurological outcomes (OR = 1.5, 95% CI [1.26-1.78]). Interestingly, this study reported sex specific differences in men vs women. From multivariate analysis, circulating levels of miR-574-5p predicted neurological outcomes in women (OR = 1.9, 95% CI [1.09-3.45]) but not in men (OR = 1.0, 95% CI [0.74-1.28]). |

| Steffanizzi et al 2020 | Logistic regression of miR-9-3p, miR-124-3p, and miR-129-5p found that these microRNAs were all associated with poorer outcomes, miR-9-3p (OR = 4.81, 95% CI [1.81-12.78]), miR-124-3p (OR = 15.92, 95% CI [2.31-109.74]) and miR-129-5p (OR = 9.2, 95% CI [2.47-34.26]). |

Discussion/Conclusions

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Competing Interests

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Materials:

List of Abbreviations

| MicroRNA/miRNA/miR | Micro ribonucleic acid. |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid. |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation. |

| UK | United Kingdom. |

| OHCA | Out of hospital cardiac arrest. |

| CA | Cardiac arrest. |

| ROSC | Return of spontaneous circulation. |

| HIBI | Hypoxic ischaemic brain injury. |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid. |

| UTR | Untranslated region. |

| qPCR | quantitative polymerase chain reaction. |

| ROC-AUC | Receiver operator characteristic area under the curve (value). |

| OR | Odds ratio. |

| HR | Hazard ratio. |

| CPC | Cerebral performance category. |

| FDR | False discovery rate. |

| CI | Confidence interval. |

| NSE | Neuron specific enolase. |

| HIF-1-alpha | Hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha. |

| MI/RI | Myocardial ischaemia reperfusion injury. |

| TTM | Targeted temperature management. |

Appendix A

- Beske RP, Bache S, Abild Stengaard Meyer M, Kjærgaard J, Bro-Jeppesen J, Obling L, Olsen MH, Rossing M, Nielsen FC, Møller K, Nielsen N, Hassager C. MicroRNA-9-3p: a novel predictor of neurological outcome after cardiac arrest. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2022 Aug 9;11(8):609-616. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjacc/zuac066

- Gilje P, Gidlöf O, Rundgren M, Cronberg T, Al-Mashat M, Olde B, Friberg H, Erlinge D. The brain-enriched microRNA miR-124 in plasma predicts neurological outcome after cardiac arrest. Crit Care. 2014 Mar 3;18(2):R40. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13753

- Stammet P, Goretti E, Vausort M, Zhang L, Wagner DR, Devaux Y. Circulating microRNAs after cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2012 Dec;40(12):3209-14. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825fdd5e

- Devaux Y, Dankiewicz J, Salgado-Somoza A, Stammet P, Collignon O, Gilje P, Gidlöf O, Zhang L, Vausort M, Hassager C, Wise MP, Kuiper M, Friberg H, Cronberg T, Erlinge D, Nielsen N; for Target Temperature Management After Cardiac Arrest Trial Investigators. Association of Circulating MicroRNA-124-3p Levels With Outcomes After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Substudy of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2016 Jun 1;1(3):305-13. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0480

- Oh SH, Kim HS, Park KN, Ji S, Park JY, Choi SP, Lim JY, Kim HJ, On Behalf Of Crown Investigators. The Levels of Circulating MicroRNAs at 6-Hour Cardiac Arrest Can Predict 6-Month Poor Neurological Outcome. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021 Oct 15;11(10):1905. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11101905

- Yu J, Zhou A, Li Y. Clinical value of miR-191-5p in predicting the neurological outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Ir J Med Sci. 2022 Aug;191(4):1607-1612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02745-6

- Shen H, Zaitseva D, Yang Z, Forsythe L, Joergensen S, Zone AI, Shehu J, Maghraoui S, Ghorbani A, Davila A, Issadore D, Abella BS. Brain-derived extracellular vesicles as serologic markers of brain injury following cardiac arrest: A pilot feasibility study. Resuscitation. 2023 Oct;191:109937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2023.109937

- Devaux Y, Salgado-Somoza A, Dankiewicz J, Boileau A, Stammet P, Schritz A, Zhang L, Vausort M, Gilje P, Erlinge D, Hassager C, Wise MP, Kuiper M, Friberg H, Nielsen N; TTM-trial investigators. Incremental Value of Circulating MiR-122-5p to Predict Outcome after Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Theranostics. 2017 Jun 25;7(10):2555-2564. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.19851

- Boileau A, Somoza AS, Dankiewicz J, Stammet P, Gilje P, Erlinge D, Hassager C, Wise MP, Kuiper M, Friberg H, Nielsen N, Devaux Y; TTM-Trial Investigators on behalf of Cardiolinc Network. Circulating Levels of miR-574-5p Are Associated with Neurological Outcome after Cardiac Arrest in Women: A Target Temperature Management (TTM) Trial Substudy. Dis Markers. 2019 Jun 2;2019:1802879. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1802879

- Stefanizzi FM, Nielsen N, Zhang L, Dankiewicz J, Stammet P, Gilje P, Erlinge D, Hassager C, Wise MP, Kuiper M, Friberg H, Devaux Y, Salgado-Somoza A. Circulating Levels of Brain-Enriched MicroRNAs Correlate with Neuron Specific Enolase after Cardiac Arrest-A Substudy of the Target Temperature Management Trial. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jun 19;21(12):4353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21124353

References

- Lemiale V, Dumas F, Mongardon N, Giovanetti O, Charpentier J, Chiche JD, Carli P, Mira JP, Nolan J, Cariou A. Intensive care unit mortality after cardiac arrest: the relative contribution of shock and brain injury in a large cohort. Intensive Care Med. 2013 Nov;39(11):1972-80. [CrossRef]

- Perkins D.G., Nolan P.J., Soar J, Hawkes C, Wylie J, Skellet S, Lockey A, Hampshire S., Epidemiology of Cardiac Arrest Guidelines. Resuscitation Council UK. May 2020. Available at https://www.resus.org.uk/library/2021-resuscitation-guidelines/epidemiology-cardiac-arrest-guidelines.

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014 Jan 21;129(3):399-410. [CrossRef]

- Couper K, Ji C, Deakin CD, Fothergill RT, Nolan JP, Long JB, Mason JM, Michelet F, Norman C, Nwankwo H, Quinn T, Slowther AM, Smyth MA, Starr KR, Walker A, Wood S, Bell S, Bradley G, Brown M, Brown S, Burrow E, Charlton K, Claxton Dip A, Dra'gon V, Evans C, Falloon J, Foster T, Kearney J, Lang N, Limmer M, Mellett-Smith A, Miller J, Mills C, Osborne R, Rees N, Spaight RES, Squires GL, Tibbetts B, Waddington M, Whitley GA, Wiles JV, Williams J, Wiltshire S, Wright A, Lall R, Perkins GD; PARAMEDIC-3 Collaborators. A Randomized Trial of Drug Route in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. N Engl J Med. 2025 Jan 23;392(4):336-348. [CrossRef]

- Sandroni C, Cronberg T, Sekhon M. Brain injury after cardiac arrest: pathophysiology, treatment, and prognosis. Intensive Care Med. 2021 Dec;47(12):1393-1414. [CrossRef]

- Nolan JP, Sandroni C, Böttiger BW, Cariou A, Cronberg T, Friberg H, Genbrugge C, Haywood K, Lilja G, Moulaert VRM, Nikolaou N, Olasveengen TM, Skrifvars MB, Taccone F, Soar J. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine guidelines 2021: post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med. 2021 Apr;47(4):369-421. [CrossRef]

- Chalkias A, Xanthos T. Post-cardiac arrest brain injury: pathophysiology and treatment. J Neurol Sci. 2012 Apr 15;315(1-2):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Lassen NA. Normal average value of cerebral blood flow in younger adults is 50 ml/100 g/min. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985 Sep;5(3):347-9. [CrossRef]

- Donkor ES. Stroke in the 21st Century: A Snapshot of the Burden, Epidemiology, and Quality of Life. Stroke Res Treat. 2018 Nov 27;2018:3238165. [CrossRef]

- Hossmann KA. Viability thresholds and the penumbra of focal ischemia. Ann Neurol. 1994 Oct;36(4):557-65. [CrossRef]

- Salaudeen MA, Bello N, Danraka RN, Ammani ML. Understanding the Pathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke: The Basis of Current Therapies and Opportunity for New Ones. Biomolecules. 2024 Mar 4;14(3):305. [CrossRef]

- Woodruff TM, Thundyil J, Tang SC, Sobey CG, Taylor SM, Arumugam TV. Pathophysiology, treatment, and animal and cellular models of human ischemic stroke. Mol Neurodegener. 2011 Jan 25;6(1):11. [CrossRef]

- Qin C, Yang S, Chu YH, Zhang H, Pang XW, Chen L, Zhou LQ, Chen M, Tian DS, Wang W. Signalling pathways involved in ischemic stroke: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Jul 6;7(1):215. Erratum in: Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Aug 12;7(1):278. [CrossRef]

- Sandroni C, D'Arrigo S, Nolan JP. Prognostication after cardiac arrest. Crit Care. 2018 Jun 5;22(1):150. [CrossRef]

- Bhalala OG, Srikanth M, Kessler JA. The emerging roles of microRNAs in CNS injuries. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013 Jun;9(6):328-39. [CrossRef]

- Calin GA, Hubé F, Ladomery MR, Delihas N, Ferracin M, Poliseno L, Agnelli L, Alahari SK, Yu AM, Zhong XB. The 2024 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine: microRNA Takes Center Stage. Noncoding RNA. 2024 Dec 12;10(6):62. [CrossRef]

- Çakmak HA, Demir M. MicroRNA and Cardiovascular Diseases. Balkan Med J. 2020 Feb 28;37(2):60-71. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Ss., Jin, Jp., Wang, Jq. et al. miRNAS in cardiovascular diseases: potential biomarkers, therapeutic targets and challenges. Acta Pharmacol Sin 39, 1073–1084 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kapplingattu, S.V., Bhattacharya, S. & Adlakha, Y.K. MiRNAs as major players in brain health and disease: current knowledge and future perspectives. Cell Death Discov. 11, 7 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Gao Y, Han D, Feng J. MicroRNA in multiple sclerosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2021 May;516:92-99. [CrossRef]

- Bassot, A., Dragic, H., Haddad, S.A. et al. Identification of a miRNA multi-targeting therapeutic strategy in glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis 14, 630 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Palizkaran Yazdi, M., Barjasteh, A. & Moghbeli, M. MicroRNAs as the pivotal regulators of Temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma. Mol Brain 17, 42 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Khan, P., Siddiqui, J.A., Kshirsagar, P.G. et al. MicroRNA-1 attenuates the growth and metastasis of small cell lung cancer through CXCR4/FOXM1/RRM2 axis. Mol Cancer 22, 1 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Yao Q, Wang X, He W, Song Z, Wang B, Zhang J, Qin Q. Circulating microRNA-144-3p and miR-762 are novel biomarkers of Graves' disease. Endocrine. 2019 Jul;65(1):102-109. [CrossRef]

- Huang C, Xing X, Xiang X, Fan X, Men R, Ye T, Yang L. MicroRNAs in autoimmune liver diseases: from diagnosis to potential therapeutic targets. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020 Oct;130:110558. [CrossRef]

- Metcalf G.A.D., (2024) Circulating biomarkers for the early detection of imperceptible cancers via biosensor and machine-learning advances, Oncogene. 43, 2135-2142). [CrossRef]

- Gayosso-Gómez, L.V, Ortiz-Quintero, B.,(2021) Circulating MicroRNAs in blood and other body fluids as biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy response in lung cancer, Diagnostics. 11,421. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell P.S, Parkin R.K, Kroh E.M, Fritz B.R, Wyman S.K, Pogosova-Agadjanyan E.L, Peterson A, Noteboom J, O'Briant K.C, Allen A, Lin D.W, Urban N, Drescher C.W, Knudsen B.S, Stirewalt D.L, Gentleman R, Vessella R.L, Nelson P.S, Martin D.B, Tewari M., (2008) Circulating microRNAs as stable blood based biomarkers for cancer detection, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA.105 (30) 10513-10518. [CrossRef]

- Gareev I, Beylerli O, Zhao B., (2024) MiRNAs as potential therapeutic targets and biomarkers for non-traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage, Biomark Res 12,17 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Geocadin, R. G. et al. Standards for Studies of Neurological Prognostication in Comatose Survivors of Cardiac Arrest: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 140(9), e517–e542.

- Edgren E, Hedstrand U, Kelsey S, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Safar P. Assessment of neurological prognosis in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. BRCT I Study Group. Lancet. 1994 Apr 30;343(8905):1055-9. [CrossRef]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993 Dec 3;75(5):843-54. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Feng Z, Du L, Huang Y, Ge J, Deng Y, Mei Z. The Potential Role of MicroRNA-124 in Cerebral Ischemia Injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Dec 23;21(1):120. [CrossRef]

- Huang P, Wei S, Ren J, Tang Z, Guo M, Situ F, Zhang D, Zhu J, Xiao L, Xu J, Liu G. MicroRNA-124-3p alleviates cerebral ischaemia-induced neuroaxonal damage by enhancing Nrep expression. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2023 Feb;32(2):106949. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., Murata, K., Ikeda, T. et al. miR-124-3p downregulates EGR1 to suppress ischemia-hypoxia reperfusion injury in human iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Sci Rep 14, 14811 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Han F, Chen Q, Su J, Zheng A, Chen K, Sun S, Wu H, Jiang L, Xu X, Yang M, Yang F, Zhu J, Zhang L. MicroRNA-124 regulates cardiomyocyte apoptosis and myocardial infarction through targeting Dhcr24. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019 Jul;132:178-188. [CrossRef]

- Liang Y.P, Liu Q, Xu G.H, Zhang J, Chen Y, Hua F.Z, Deng C.Q, Hu Y.H., (2019)The lncRNA ROR/miR-124-3p/TRAF6 axis regulated the ischaemia reperfusion injury-induced inflammatory response in human cardiac myocytes. J Bioenerg Biomembr 51, 381–392. [CrossRef]

- Han F, Chen Q, Su J, Zheng A, Chen K, Sun S, Wu H, Jiang L, Xu X, Yang M, Yang F, Zhu J, Zhang L. MicroRNA-124 regulates cardiomyocyte apoptosis and myocardial infarction through targeting Dhcr24. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019 Jul;132:178-188. [CrossRef]

- Hu, G., Ma, L., Dong, F., Hu, X., Liu, S., & Sun, H. (2019). Inhibition of microRNA-124-3p protects against acute myocardial infarction by suppressing the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes. Molecular Medicine Reports, 20, 3379-3387. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., Ai, M., Xie, S. et al. NSE and S100β as serum alarmins in predicting neurological outcomes after cardiac arrest. Sci Rep 14, 25539 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Rundgren M, Karlsson T, Nielsen N, Cronberg T, Johnsson P, Friberg H. Neuron specific enolase and S-100B as predictors of outcome after cardiac arrest and induced hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2009 Jul;80(7):784-9. [CrossRef]

- Scolletta S, Donadello K, Santonocito C, Franchi F, Taccone FS. Biomarkers as predictors of outcome after cardiac arrest. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2012 Nov;5(6):687-99. [CrossRef]

- Nolan JP, Sandroni C, Böttiger BW, Cariou A, Cronberg T, Friberg H, Genbrugge C, Haywood K, Lilja G, Moulaert VRM, Nikolaou N, Olasveengen TM, Skrifvars MB, Taccone F, Soar J. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine guidelines 2021: post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med. 2021 Apr;47(4):369-421. [CrossRef]

- Ramont L, Thoannes H, Volondat A, Chastang F, Millet MC, Maquart FX. Effects of hemolysis and storage condition on neuron-specific enolase (NSE) in cerebrospinal fluid and serum: implications in clinical practice. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43(11):1215-7. [CrossRef]

- Stern P, Bartos V, Uhrova J, Bezdickova D, Vanickova Z, Tichy V, Pelinkova K, Prusa R, Zima T. Performance characteristics of seven neuron-specific enolase assays. Tumour Biol. 2007;28(2):84-92. [CrossRef]

- Sandau, U.S., Wiedrick, J.T., McFarland, T.J. et al. Analysis of the longitudinal stability of human plasma miRNAs and implications for disease biomarkers. Sci Rep 14, 2148 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Glinge C, Clauss S, Boddum K, Jabbari R, Jabbari J, Risgaard B, Tomsits P, Hildebrand B, Kääb S, Wakili R, Jespersen T, Tfelt-Hansen J. Stability of Circulating Blood-Based MicroRNAs - Pre-Analytic Methodological Considerations. PLoS One. 2017 Feb 2;12(2):e0167969. [CrossRef]

- Faramin Lashkarian, M., Hashemipour, N., Niaraki, N. et al. MicroRNA-122 in human cancers: from mechanistic to clinical perspectives. Cancer Cell Int 23, 29 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Feng, W., Ying, Z., Ke, F., & Mei-Lin, X. (2021). Apigenin suppresses TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblast differentiation and collagen synthesis through the downregulation of HIF-1α expression by miR-122-5p. Phytomedicine, 83, 153481. [CrossRef]

- Bamahel, A.S., Sun, X., Wu, W. et al. Regulatory Roles and Therapeutic Potential of miR-122-5p in Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury: Comprehensive Review. Cell Biochem Biophys (2025). [CrossRef]

- Kong Y, Li S, Cheng X, Ren H, Zhang B, Ma H, Li M, Zhang XA. Brain Ischemia Significantly Alters microRNA Expression in Human Peripheral Blood Natural Killer Cells. Front Immunol. 2020 May 14;11:759. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Fu L, Zhang J, Zhou B, Tang Y, Zhang Z, Gu T. Inhibition of MicroRNA-122-5p Relieves Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury via SOCS1. Hamostaseologie. 2023 Aug;43(4):271-280. [CrossRef]

- Jenike AE, Halushka MK. miR-21: a non-specific biomarker of all maladies. Biomark Res. 2021 Mar 12;9(1):18. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, Erlinge D, Gasche Y, Hassager C, Horn J, Hovdenes J, Kjaergaard J, Kuiper M, Pellis T, Stammet P, Wanscher M, Wise MP, Åneman A, Al-Subaie N, Boesgaard S, Bro-Jeppesen J, Brunetti I, Bugge JF, Hingston CD, Juffermans NP, Koopmans M, Køber L, Langørgen J, Lilja G, Møller JE, Rundgren M, Rylander C, Smid O, Werer C, Winkel P, Friberg H; TTM Trial Investigators. Targeted temperature management at 33°C versus 36°C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013 Dec 5;369(23):2197-206. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).