Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

14 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

1.2. Research Objectives

- 1)

- To assess how well different attribution techniques (e.g., gradient-based, SHAP, XGBoost built-in) identify the true causal features versus non-causal (spurious or confounded) features in financial ML models.

- 2)

- To design and implement synthetic data-generating processes that mirror plausible causal structures found in three key financial scenarios: asset pricing, credit risk assessment, and fraud detection.

- 3)

- To identify specific scenarios and causal structures where current attribution methods are most likely to provide misleading or causally unfaithful explanations.

- 4)

- To provide insights and potential guidelines for financial practitioners on the cautious interpretation of feature attributions and the importance of considering underlying causal assumptions.

1.3. Significance in Financial Domain

- Investment Strategies: Misattributing market movements to spurious indicators rather than true economic drivers can lead to flawed investment strategies and capital misallocation.

- Credit Risk and Fairness: If a credit scoring model attributes risk to a feature that is merely a proxy for a protected attribute (e.g., race or gender) due to socioeconomic confounding, it can perpetuate and amplify biases, leading to unfair lending decisions.

- Fraud Detection: Mistaking consequences of fraud for its causes can lead to reactive rather than proactive fraud prevention measures, and potentially misdirect investigative efforts.

- Regulatory Compliance and Model Auditing: Regulators require transparent and fair models. If the explanations provided are not causally sound, institutions may fail to meet these requirements or, worse, mask problematic model behavior.

- Systemic Risk: A widespread reliance on models whose explanations are causally flawed could, in aggregate, contribute to systemic misjudgments of risk or market dynamics.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Feature Attribution Methods

- Gradient-based approaches: These methods utilize the gradients of the model’s output with respect to its inputs. A simple example is Saliency Maps [2], which use the absolute value of the gradient. Extensions include Gradient×Input [3], which multiplies the gradient by the input feature value, and Integrated Gradients (IG) [4], which satisfies axioms like sensitivity and implementation invariance by integrating gradients along a path from a baseline input to the actual input.

- Perturbation-based methods: These methods assess feature importance by observing the change in model output when features are perturbed, masked, or removed. LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) [5] is a prominent example, which learns a simple, interpretable local linear model around the prediction to be explained.

- Model-specific techniques: Some methods are tailored to particular model architectures. For tree-based ensembles like XGBoost, feature importances can be derived from metrics like “gain” (total reduction in loss due to splits on a feature), “weight” (number of times a feature is used to split), or “cover” (average number of samples affected by splits on a feature). SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [6] provides a unified framework based on game-theoretic Shapley values, offering both model-specific (e.g., TreeSHAP for tree ensembles) and model-agnostic (e.g., KernelSHAP) versions. Attention mechanisms in Transformer models can also be interpreted as a form of feature attribution, though their direct interpretation as importance scores is debated [7].

- Decomposition-based methods: Layer-Wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) [8] decomposes the prediction score backwards through the network layers to assign relevance scores to inputs.

2.2. Causal Inference in Machine Learning

- Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs): DAGs are used to represent causal assumptions among variables, where nodes are variables and directed edges represent causal influences. The absence of an edge implies no direct causal effect.

- Confounding Variables: A confounder is a variable that causally influences both the “treatment” (or feature of interest) and the “outcome” (or target variable), potentially creating a spurious correlation between them if not accounted for.

- Interventional vs. Observational Data: Observational data, common in finance, only allows us to see correlations (). Causal claims often require understanding interventional distributions (), i.e., the effect of actively changing X. ML models trained on observational data learn correlational patterns.

2.3. Explainable AI in Finance

- Regulatory Scrutiny: Regulations like the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) in the U.S. (requiring explanations for adverse credit decisions) and GDPR in Europe necessitate model transparency.

- Risk Management: Understanding model vulnerabilities, potential biases, and behavior under stress is crucial for internal risk control.

- Stakeholder Trust: Explanations can help build trust with clients, investors, and internal users.

- Model Debugging and Improvement: Interpretability aids in identifying model flaws and improving performance.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Causal Structures in Financial Data

-

Confounding Variables: These are ubiquitous in finance.

- Market-wide factors: Broad market sentiment, macroeconomic announcements (e.g., interest rate changes, inflation reports), geopolitical events, or even unobserved liquidity shocks can influence both individual asset prices (or other financial outcomes) and various observable features used by models. For example, strong positive market sentiment (Z) might simultaneously boost a stock’s price (Y) and increase trading volume () for that stock. A model might attribute predictive power to for Y, even if volume itself isn’t a direct cause, because both are driven by Z.

- Sector-specific effects: News or trends affecting an entire industry can act as confounders for individual company performance and related features.

- Socioeconomic factors in credit/fraud: In credit risk, variables like local unemployment rates or economic downturns (Z) can affect both an individual’s financial behavior (e.g., payment history, ) and their likelihood of default (Y), while also correlating with proxy variables like zip code ().

-

Proxy Variables and Indirect Indicators:

- Proxy Bias: Features that are not directly causal but are correlated with protected attributes (like race, gender) and also with the outcome (e.g., default risk) due to systemic biases or socioeconomic confounding. Attribution methods might highlight these proxies, leading to interpretations that mask discrimination or misattribute risk.

- Indirect Indicators (Consequences vs. Causes): In fraud detection, some features might be strong predictors because they are consequences of fraud, not its root causes. For instance, a sudden flurry of small transactions () might occur after an account is compromised (). While is predictive, attributing fraud to it mistakes an effect for a cause.

- Spurious Correlations due to Non-Stationarity and Noise: Financial time series are often non-stationary, and the sheer volume of available data can lead to coincidental correlations that hold over certain periods but lack any underlying causal link. Models can easily overfit to such patterns, and attribution methods would then highlight these spurious features.

- Temporal Dependencies and Feedback Loops: Past outcomes can influence future features and outcomes, creating complex feedback loops that are hard to disentangle causally from purely observational data.

3.2. Attribution Methods’ Limitations in a Causal Context

- Correlation vs. Causation: Standard ML models are optimized to find correlational patterns that maximize predictive accuracy. If a non-causal feature is highly correlated with the target Y (perhaps due to a confounder Z), the model will likely learn to use . Attribution methods will then correctly report that is important to the model, but this can be easily misinterpreted as being causally important for Y in the real world.

- Sensitivity to Model Specification: The attributions are model-dependent. Different models, even if trained on the same data and achieving similar predictive accuracy, can learn different internal representations and thus yield different feature attributions. This makes it hard to claim a universal “causal” interpretation from model-based attributions alone.

- Local vs. Global Explanations: Methods like LIME provide local explanations. While useful for understanding a single prediction, these local attributions might not generalize to global causal statements, especially if the model’s decision boundaries are highly non-linear. Even global methods like SHAP average local effects, which might obscure context-specific causal relationships.

- Ignoring Unobserved Confounders: Attribution methods operate on the features provided to the model. If a critical unobserved confounder influences both an observed feature and the target, the observed feature might receive high attribution, masking the true causal role of the unobserved variable.

- Baseline Choice (for methods like Integrated Gradients): The choice of baseline for path-based attribution methods can significantly affect the resulting scores, and defining a causally meaningful baseline is non-trivial, especially for complex, high-dimensional financial data.

4. Methodology

4.1. Synthetic Data Generation

4.1.1. Asset Pricing Scenario

- Objective: Predict future stock returns (regression task).

- Features: Causal features (e.g., fundamental_0, fundamental_1) represent true economic drivers. Spurious features (e.g., spurious_0, spurious_1, spurious_2) are correlated with returns via common confounders (e.g., market sentiment) but are not direct causes.

4.1.2. Credit Risk Scenario

- Objective: Predict loan default probability (binary classification task).

- Features: Causal features (e.g., behavioral_0, behavioral_1) represent true behavioral risk factors. Proxy features (e.g., proxy_0, proxy_1) are non-causal but may be correlated with default through socioeconomic confounders, potentially capturing biases.

4.1.3. Fraud Detection Scenario

- Objective: Identify fraudulent transactions (imbalanced binary classification task).

- Features: Causal features (e.g., anomaly_0, anomaly_1) represent true indicators of fraudulent activity. Indirect indicators (e.g., indirect_0, indirect_1) are consequences of fraud (e.g., subsequent account lock) and are thus highly predictive but not causal drivers.

4.2. Model Architectures

- Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs): Standard feedforward neural networks.

- Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs): Intended for sequential data but applied to tabular data by treating samples as sequences.

- Gradient Boosting Machines (XGBoost): Utilizing the XGBoost library, known for strong performance on tabular data.

4.3. Attribution Methods to Evaluate

- Saliency Maps: Gradient-based.

- Gradient × Input: Modified gradient-based.

- Integrated Gradients (IG): Path-integral based gradient method.

- SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): Game-theoretic approach, using TreeSHAP for XGBoost models.

- XGBoost Built-in Feature Importance (denoted ’xgboost’ in results): Native feature importance scores from XGBoost models (based on ’gain’).

5. Experimental Design

5.1. Evaluation Metrics for Causal Faithfulness

-

Attribution Ranking Metrics:

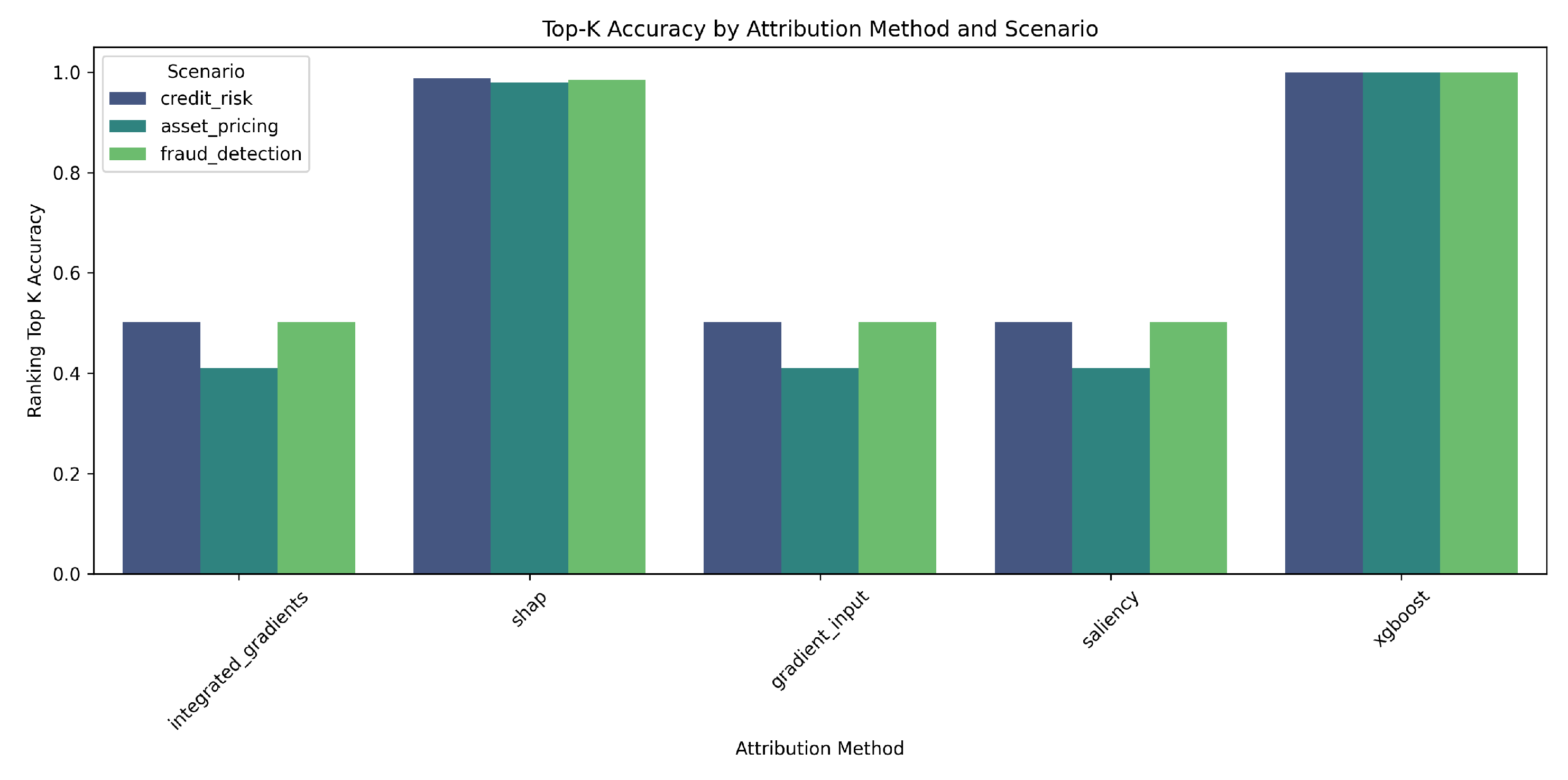

- Top-K Accuracy: Proportion of the top k attributed features (where k is the true number of causal features) that are indeed causal. Higher is better.

-

Attribution Magnitude Metrics:

- Attribution Ratio: Ratio of mean absolute attribution of causal features to non-causal features. Higher values indicate better discrimination.

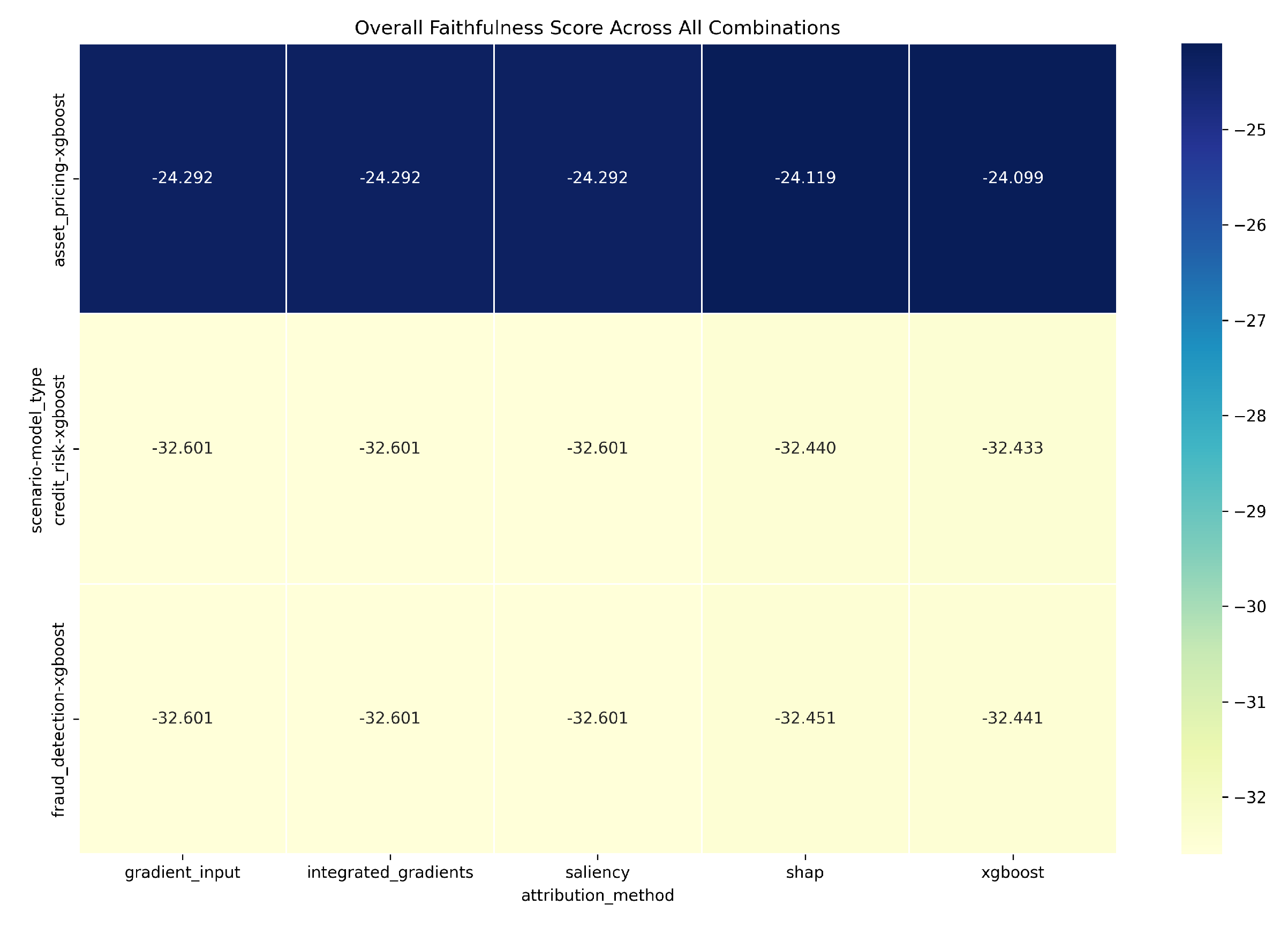

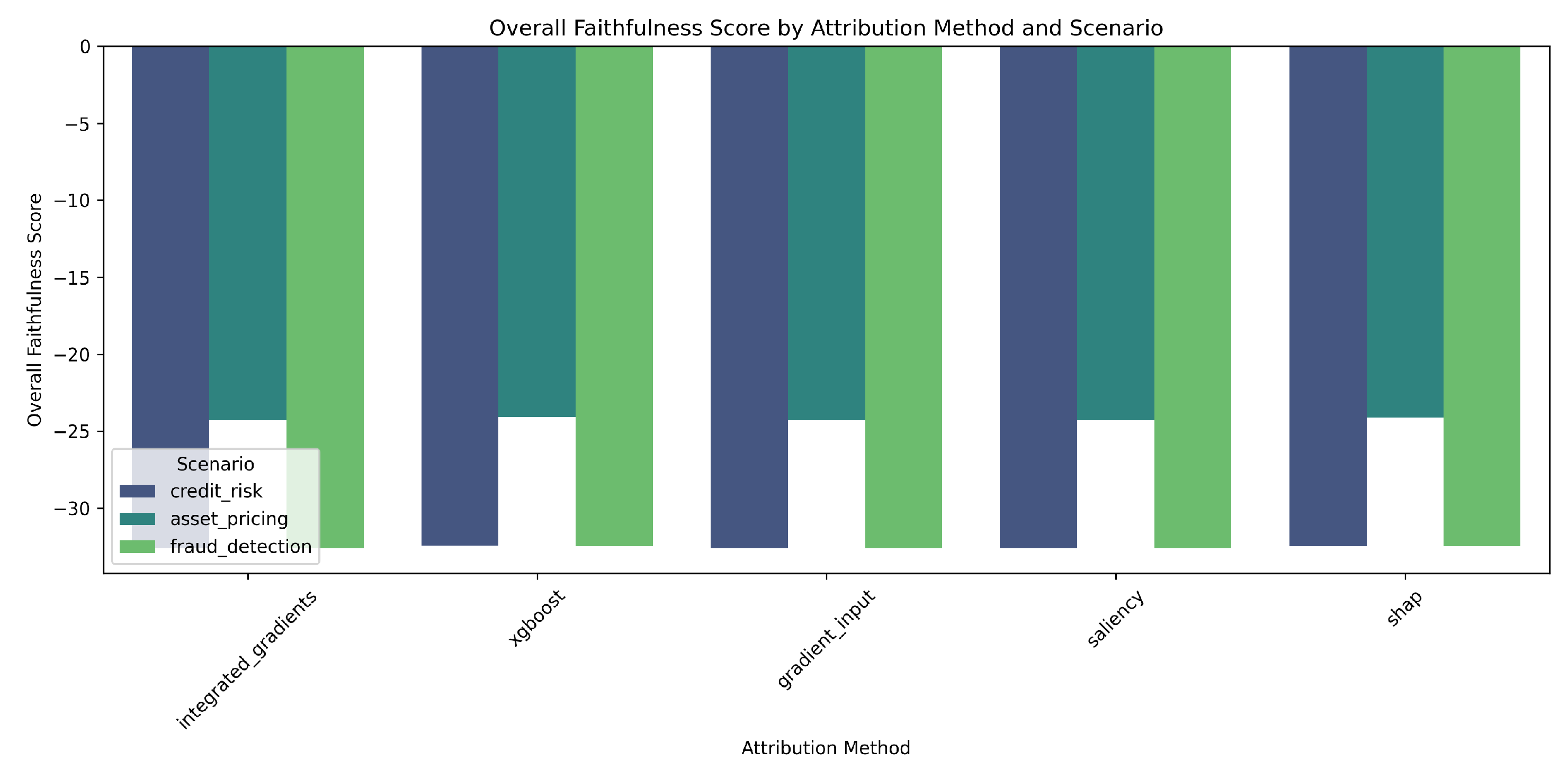

- Overall Faithfulness Score: A composite score combining several normalized key metrics. Less negative values (closer to zero) are better.

5.2. Benchmark Scenarios and Experimental Protocol

- Generating datasets for the three financial scenarios.

- Training MLP, LSTM, and XGBoost models on each scenario.

- Computing feature attributions using Saliency, Gradient×Input, Integrated Gradients, SHAP, and XGBoost built-in importance for the trained models (primarily XGBoost models in detailed analysis).

- Evaluating causal faithfulness using the metrics defined above and generating visualizations.

6. Results and Analysis

6.1. Model Performance

6.2. Faithfulness Evaluation: Attribution Method Comparison

6.3. Scenario-Specific Analysis (XGBoost Model)

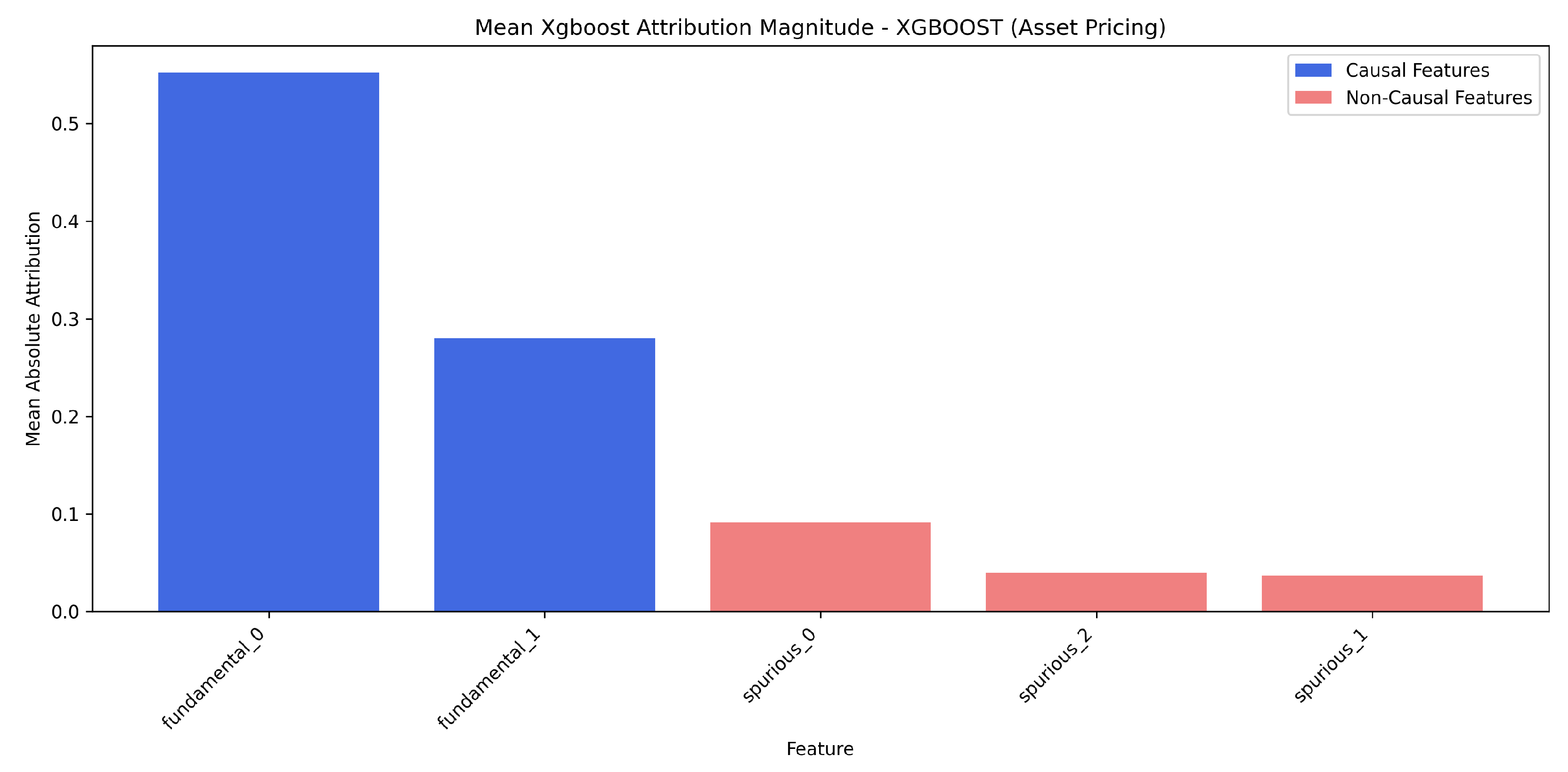

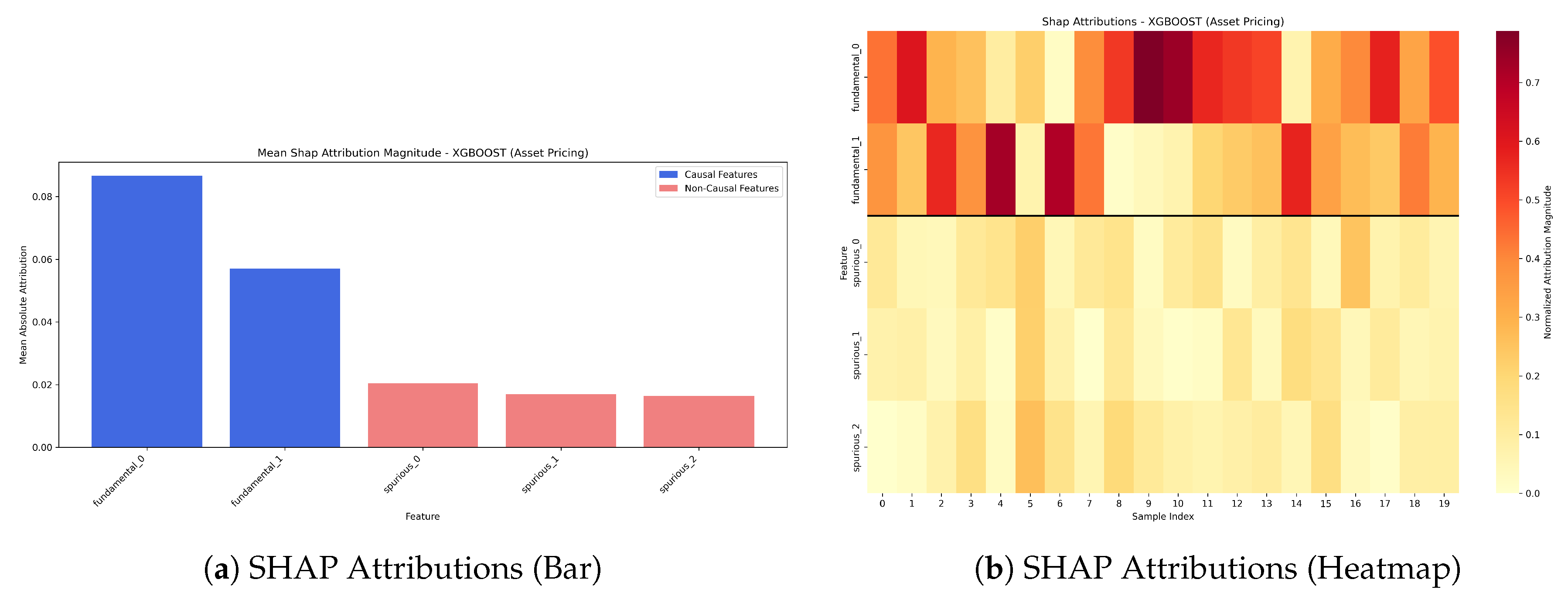

6.3.1. Asset Pricing

-

XGBoost model, ’xgboost’ method:

- –

- Overall Faithfulness Score: -24.0987

- –

- Top-K Accuracy: 1.0000

- –

- Attribution Ratio (Causal/Non-Causal): 7.4218

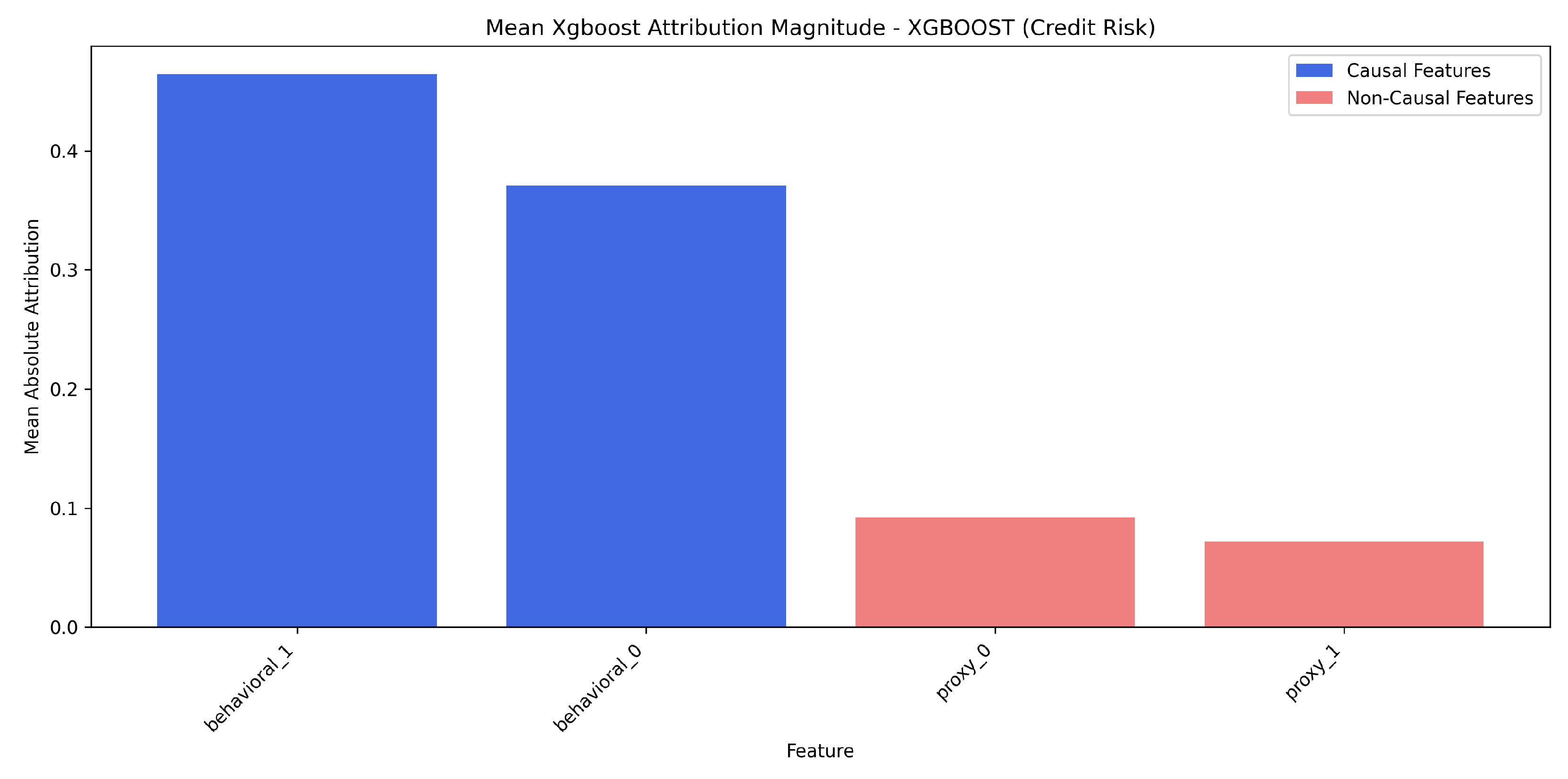

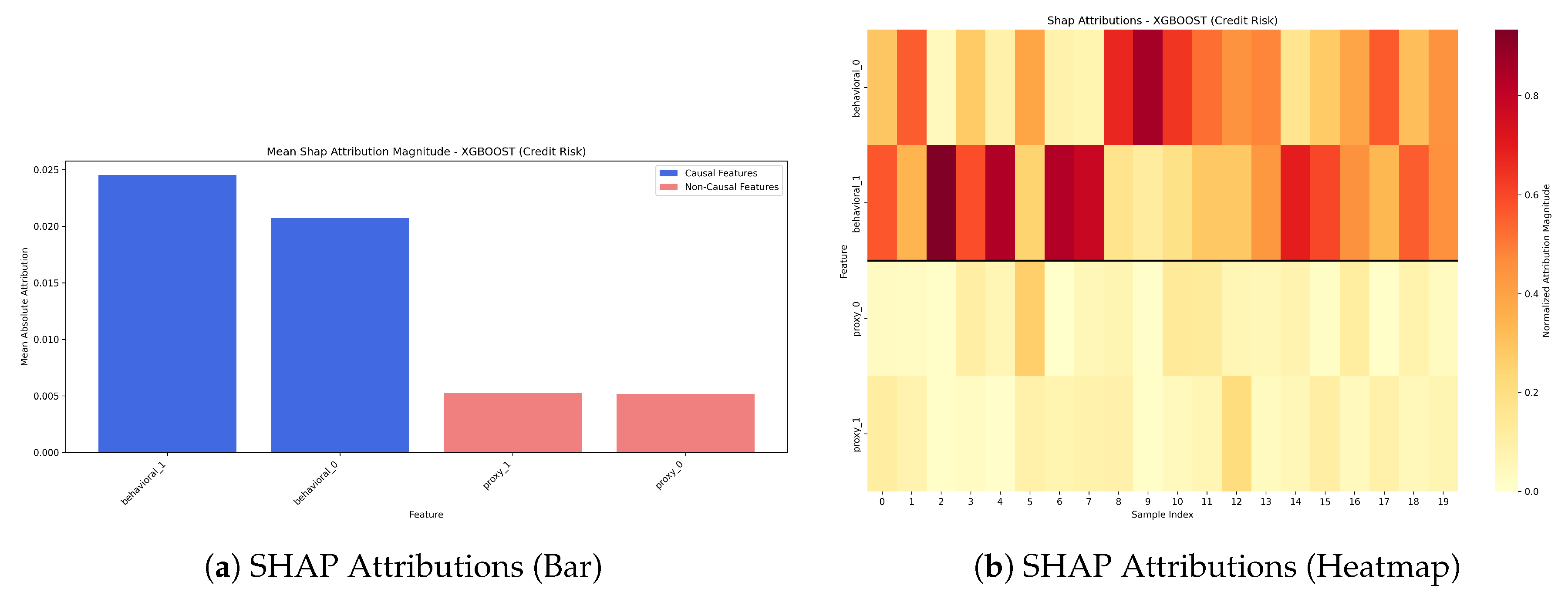

6.3.2. Credit Risk

-

XGBoost model, ’xgboost’ method:

- –

- Overall Faithfulness Score: -32.4329

- –

- Top-K Accuracy: 1.0000

- –

- Attribution Ratio (Causal/Non-Causal): 5.0847

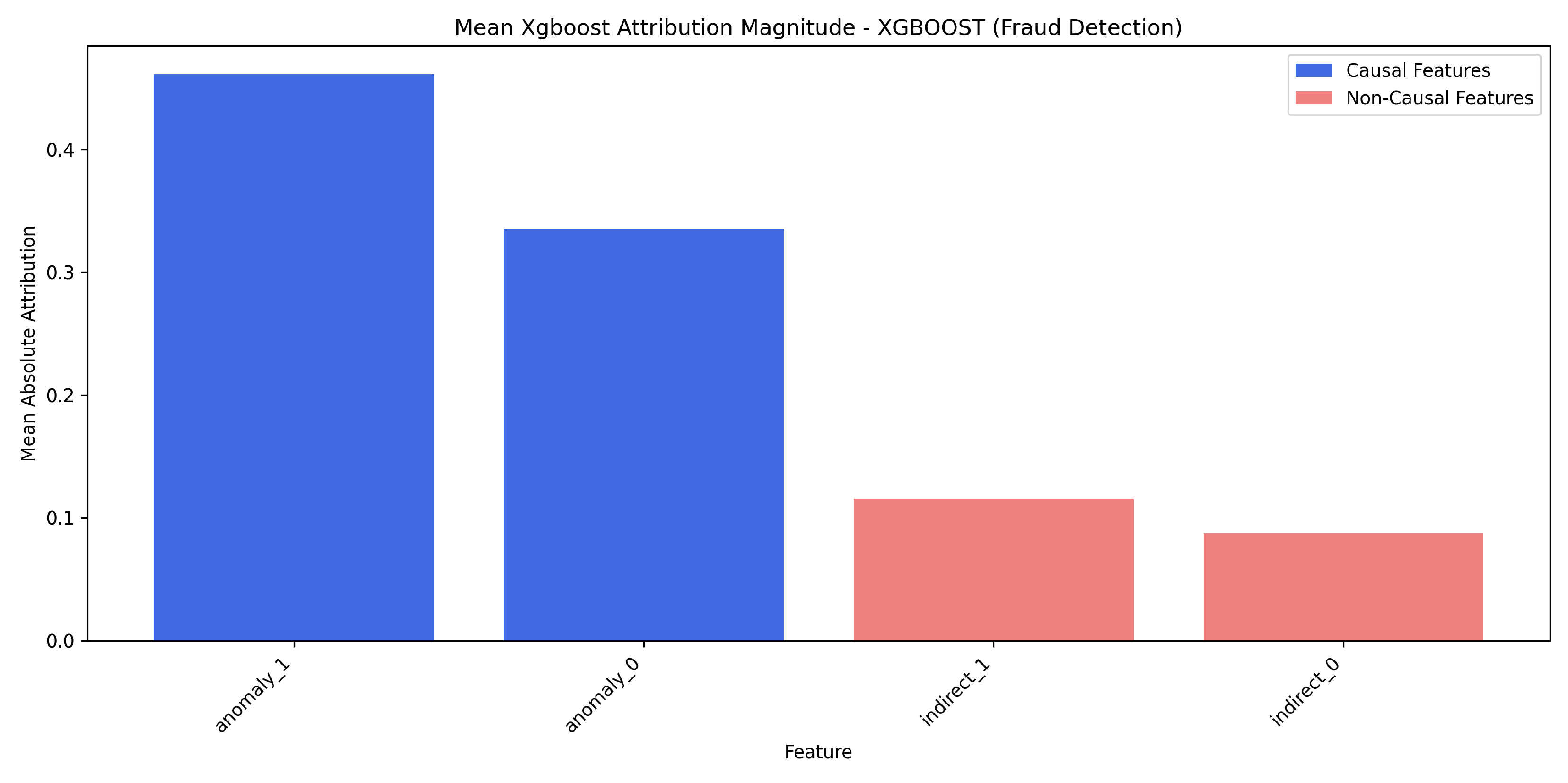

6.3.3. Fraud Detection

-

XGBoost model, ’xgboost’ method:

- –

- Overall Faithfulness Score: -32.4407

- –

- Top-K Accuracy: 1.0000

- –

- Attribution Ratio (Causal/Non-Causal): 3.9188

6.4. Model-Specific Analysis

7. Discussion

7.1. Key Findings and Implications

- Xgboost (built-in importance) performs best: Our experiments show that XGBoost’s native feature importance (referred to as the ’xgboost’ attribution method in results) provides the most causally faithful explanations on average across the financial scenarios when used with XGBoost models (Overall Score: -29.6574, Top-K Accuracy: 1.0000). SHAP is a strong second-best performer (Overall Score: -29.6700, Top-K Accuracy: 0.9837). Other gradient-based methods performed significantly worse.

- XGBOOST models yield more causally accurate attributions: XGBOOST models consistently demonstrated a superior ability to generate attributions that align with the true causal structure in our synthetic datasets, particularly when paired with robust attribution methods like its own built-in importance or SHAP.

- Fraud detection presents unique challenges: The fraud detection scenario highlighted a critical pitfall. Indirect indicators (which are consequences of fraud, not causes) often receive substantial attribution weight. This is because they are highly correlated with the fraudulent event, making them predictively useful for the model, but causally misleading if interpreted as drivers of fraud. This emphasizes the difficulty of distinguishing causes from effects using standard attribution methods, even with top-performing techniques.

- Multiple attribution methods recommended: The significant variability in performance across methods suggests that relying on a single technique, especially if it’s a simpler gradient-based one, might be insufficient. Using multiple, robust techniques can provide a more comprehensive understanding.

- Caution needed when interpreting attributions as causal: Our findings strongly underscore that feature attributions should not be naively interpreted as causal explanations without substantial domain expertise and proper validation. Even the best-performing methods can be misleading in complex scenarios.

7.2. Misinterpretation Risks in Financial Contexts

- Investment Strategy: Over-reliance on spuriously correlated features in asset pricing can lead to flawed strategies if explanations are not causally sound.

- Lending Decisions: Attributing credit risk to proxies confounded with protected attributes can perpetuate bias, even if the model is predictively accurate.

- Fraud Prevention: Mistaking consequences for causes in fraud detection can lead to ineffective, reactive measures rather than addressing root causes.

7.3. Model Auditing and Regulatory Implications

7.4. Practical Guidelines for Financial Practitioners

- Favor XGBoost Models and Robust Attributions: When causal understanding is crucial for tabular financial data, XGBoost models paired with their built-in feature importance or SHAP provide the most reliable feature attributions among those tested.

- Exercise Caution, Especially with Indirect Effects and Confounding: Be critically aware of the data generating process. In scenarios like fraud detection (indirect effects) or credit risk (potential proxies), domain expertise is vital to critically assess attributions.

- Verify Attributions with Multiple Methods and Domain Knowledge: Given the variability, using multiple robust techniques alongside deep domain understanding can provide a more holistic view of feature importance.

- Contextualize Interpretations and Validate: While asset pricing showed the best overall scores with top methods, no method is universally perfect. Always validate interpretations against known facts and be particularly skeptical in scenarios prone to complex causal mimicry.

8. Conclusions

8.1. Summary of Key Findings

8.2. Limitations

8.3. Future Research Directions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Appendix A. Detailed DAG Specifications

Appendix A.1. Asset Pricing Scenario

Appendix A.2. Credit Risk Scenario

Appendix A.3. Fraud Detection Scenario

Appendix B. Synthetic Data Generation Code

Appendix C. Model Architectures and Hyperparameters

- MLP: Hidden Layers [64, 32], ReLU, Adam optimizer.

- LSTM: 2 LSTM layers, hidden dim 64, Adam optimizer.

- XGBoost: 100 estimators, max depth 6, learning rate 0.1.

Appendix D. Supplementary Experimental Results

| Scenario | Model Type | Gradient Input | Integrated Gradients | Saliency | SHAP | XGBoost |

| asset_pricing | xgboost | -24.292 | -24.292 | -24.292 | -24.119 | -24.099 |

| credit_risk | xgboost | -32.601 | -32.601 | -32.601 | -32.440 | -32.433 |

| fraud_detection | xgboost | -32.601 | -32.601 | -32.601 | -32.451 | -32.441 |

| Scenario | Model Type | Gradient Input | Integrated Gradients | Saliency | SHAP | XGBoost |

| asset_pricing | xgboost | 0.410 | 0.410 | 0.410 | 0.979 | 1.000 |

| credit_risk | xgboost | 0.501 | 0.501 | 0.501 | 0.988 | 1.000 |

| fraud_detection | xgboost | 0.501 | 0.501 | 0.501 | 0.984 | 1.000 |

| Scenario | Model Type | Gradient Input | Integrated Gradients | Saliency | SHAP | XGBoost |

| asset_pricing | xgboost | 1.030 | 1.030 | 1.030 | 4.003 | 7.422 |

| credit_risk | xgboost | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.979 | 4.355 | 5.085 |

| fraud_detection | xgboost | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.979 | 3.189 | 3.919 |

References

- Doshi-Velez, F.; Kim, B. Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608 2017. [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Deep inside convolutional networks: Visualising image classification models and saliency maps. In Proceedings of the Workshop at International Conference on Learning Representations, 2013.

- Shrikumar, A.; Greenside, P.; Kundaje, A. Learning important features through propagating activation differences. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2017, pp. 3145–3153.

- Sundararajan, M.; Taly, A.; Yan, Q. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2017, pp. 3319–3328.

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Why should I trust you?: Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2016, pp. 1135–1144.

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30.

- Jacovi, A.; Goldberg, Y. Towards faithful explanations of attention-based models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2020, Vol. 34, pp. 13076–13083.

- Bach, S.; Binder, A.; Montavon, G.; Klauschen, F.; Müller, K.R.; Samek, W. On pixel-wise explanations for non-linear classifier decisions by layer-wise relevance propagation. In Proceedings of the PloS one, 2015, Vol. 10.

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, reasoning and inference; Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Arjovsky, M.; Bottou, L.; Gulrajani, I.; Lopez-Paz, D. Invariant risk minimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.02893 2019. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kallus, N.; Mao, X.; Svacha, G.; Udell, M. True to the model or true to the data? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 2020, pp. 245–251.

| Scenario | Model Type | Accuracy | F1 Score | MSE | R² |

| asset_pricing | mlp | N/A | N/A | 0.2362 | 0.9402 |

| asset_pricing | lstm | N/A | N/A | 1.5332 | 0.6116 |

| asset_pricing | xgboost | N/A | N/A | 0.1806 | 0.9543 |

| credit_risk | mlp | 0.9444 | 0.9448 | N/A | N/A |

| credit_risk | lstm | 0.8998 | 0.9005 | N/A | N/A |

| credit_risk | xgboost | 0.9650 | 0.9653 | N/A | N/A |

| fraud_detection | mlp | 0.9890 | 0.8898 | N/A | N/A |

| fraud_detection | lstm | 0.9821 | 0.8212 | N/A | N/A |

| fraud_detection | xgboost | 0.9957 | 0.9561 | N/A | N/A |

| Attribution Method | Overall Score | Top-K Accuracy | Attribution Ratio |

| xgboost | -29.6574 | 1.0000 | 5.4751 |

| shap | -29.6700 | 0.9837 | 3.8490 |

| saliency | -29.8310 | 0.4710 | 0.9961 |

| gradient_input | -29.8310 | 0.4710 | 0.9961 |

| integrated_gradients | -29.8310 | 0.4710 | 0.9961 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).