1. Introduction

In water remediation, adsorption is a well-established and widely used technology due to its effectiveness, versatility and ease of use. However, adsorption treatment presents several challenges, including adsorbent selectivity, adsorption capacity and the reduction of problems associated with its acquisition, costs and waste disposal [

1]. Research is underway to address these challenges, including the use of waste from different sources as raw material for the synthesis of adsorbents.

Additionally, the rapid development of agriculture has led to a significant increase in agricultural and forestry waste. The amount of agricultural waste generated worldwide in 2019 was about 20.3 billion tons [

2]. Specifically, tree pruning is a waste generated by agriculture and municipalities. This waste is composed of leaves, seeds, fruits and stem, and in the case of the tree pruning from municipalities, it is usually disposed improperly (causing biosecurity problems) or in landfills. However, this waste can be fully utilized for beneficial purposes, reducing amount of solid waste and providing economic benefits [

2,

3].

In this way, tree pruning waste can be used to produce adsorbents for wastewater treatment, enabling the remediation of contaminated water and the reuse of waste, boosting the circular economy and sustainability. The production of adsorbents from organic waste can be carried out by thermochemical process in an inert atmosphere to produce biochar, a porous solid containing carbon [

4]. Due to their porous structure, resulting from thermal treatment and the biomass used, these materials can contain a large surface area available for adsorption or separation of components. Their surface charge is conducive to the retention of cations, such as some metals, pesticides, and synthetic organic dyes in aqueous solutions.

Recent studies have shown the use of biochar derived from the pruning of different tree species for the adsorption of various contaminants, such as pinewood biochar to remove petroleum [

5]; forest and agri-food waste for the removal of fluoxetine [

6]; oriental plane tree for the removal of bisphenol [

7]; and Conocarpus pruning for the removal of Pb

2+ [

8]. The use of different pruning waste, under varying thermochemical process, can yield in materials with different adsorption capacities to remove a wide range of contaminants. However, no studies were found proposing the use of pruning waste biochar for the removal of dyes and the influence of particle size of the adsorbent in the adsorption process.

Among the dyes, methylene blue (MB) is part of a class of reactive dyes with greater chemical stability [

9]. It is mainly used in the textile and hospital industries, due to its high solubility, brightness, resistance, and wide applicability [

10]. Since synthetic organic dyes are not treated in conventional treatments, it is necessary to apply additional techniques, such as filtration, photochemical processes, adsorption, among others [

11,

12]. Amongst these methods, adsorption stands out as an efficient process.

Adsorption is based on the separation of a substance or compound in solid, liquid or gas phase through surface phenomena until an adsorbate–adsorbent equilibrium is reached. The adsorption capacity is associated with the number of adsorption sites present in the surface of the adsorbent. The analysis of adsorption mechanisms with new adsorbents is crucial for determining their application in water treatment. In general, these mechanisms are evaluated using standard isotherm models such as Freundlich, Langmuir, and Temkin [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The adsorption isotherm characterizes and predicts the quantity of adsorbed material as a function of pressure (or concentration) at a constant temperature [

13]. The Langmuir model assumes homogeneous adsorption, while the Freundlich model is typically applied to studies of adsorption on multisite surfaces. Whereas the Temkin model assumes a multilayer adsorption process [

13].

The adsorption capacity of an adsorbent can be enhanced through the activation of biochar; however, this process can be onerous. A more cost-effective process to improve adsorption capacity is the selection of particle size and the use of different temperatures to produce biochar. Previous studies reported that the adsorption amount increased by decreasing the particle size of adsorbents [

11,

12,

15]; whereas the efficiency was enhanced by the increase in temperature of the thermochemical process. However, no study considering the variation in particle sizes and thermochemical process to compare the removal performance of tree pruning biochar were found. Therefore, this study aims to address such a research gap by evaluating the removal of emerging contaminant MB using biochar produced from the pruning of mango and pitanga trees under two temperatures and with varying particle sizes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production and Preparation of Biochar

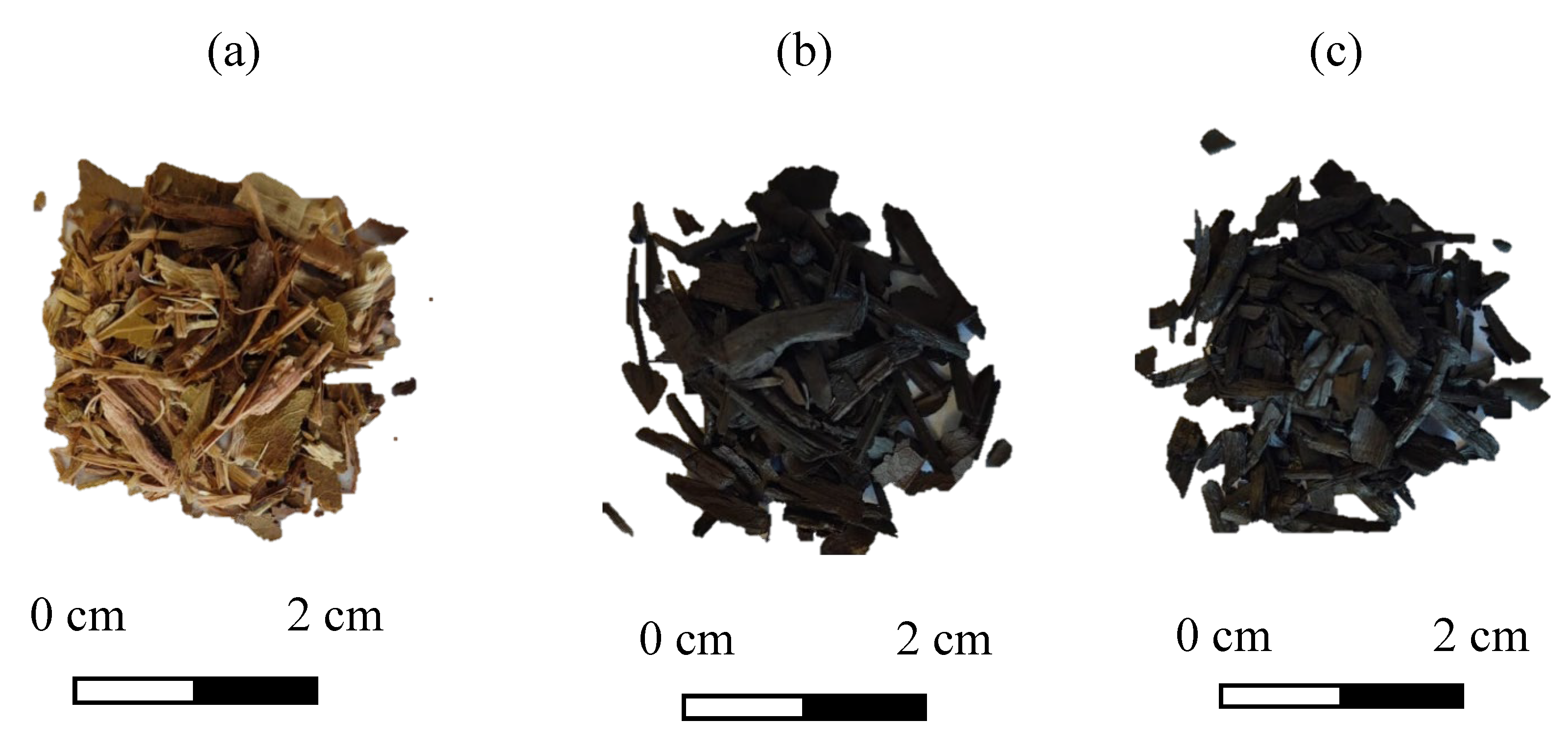

The biomasses from mango and pitanga tree pruning used in this work were collected from area 1 of the Lorena School of Engineering (EEL-USP). This material (composed mainly of stem and leaves) was sun-dried, crushed and pyrolyzed in an inert nitrogen atmosphere at 300 and 500 °C during 60 minutes. Thus, three samples were obtained: the biomass from tree prunings (raw material, called BTP-R), the biochar from tree prunings pyrolyzed at 300 °C (called BTP-300), and the biochar from tree pruning pyrolyzed at 500 °C (called BTP-500) (

Figure 1). For the adsorption tests, the material was comminuted using a knife mill.

2.2. Physical-Chemical Characterization

The characterization tests of raw and pyrolyzed biomass were performed as described in

Table 1. The tests were performed in triplicate, obtaining the mean values and standard deviations.

2.3. Preparation of Biochar and MB Solution

MB solution was prepared using distilled water and MB analytical grade (Synth®). The natural pH of the solution was determined to be 6.0. The absorbance was determined in UV–VIS (model K37-UVVIS from KASVI) and a quartz container with 10.0 mm optical path using 665 nm wavelength. Concentration was calculated using Lambert-Beer equation.

Biochar samples were disintegrated with a knife mill and sieved to achieve a target size of particles 1.25-2.00, 0.60-1.25, 0.40-0.60, 0.25-0.40 and <0.25 mm.

2.4. Sorption Studies with Methylene Blue

The sorption studies were carried out to evaluate the influence of the temperature of the initial concentration of MB, the particle size of the adsorbent and the thermochemical process. For this purpose, batch equilibrium tests were performed in 15 mL Falcon tubes, where 0.10 g of adsorbent (BTP-R, BTP-300 and BTP-500) and 10 mL of MB solution were added. The proportion of 1:100 of biochar and solution was previously reported as an ideal portion of adsorbent and solution volume [

11].

Influence of initial dye concentration: to evaluate the influence of the initial MB concentration, the concentration of the dye solution was varied (25, 50, 100, 200 and 400 mg L-1), keeping the adsorbent mass (0.10 g) and the particle size fraction (< 0.60 mm) fixed. This particle size was selected based on previous studies.

Influence of the particle size: to evaluate the influence of particle size, the particle diameter of the adsorbent was varied (1.25-2.00, 0.60-1.25, 0.40-0.60, 0.25-0.40 and <0.25 mm), keeping the initial concentration of MB (100 mg L-1) fixed. The concentration was selected based on the results obtained previously, on the influence of initial dye concentration.

Influence of the thermochemical process: to evaluate the influence of the thermochemical process, the sorption studies were conducted with three different types of BTP (BTP-R, BTP-300 and BTP-500).

All tests were performed for a period of 24 hours on a shaker adjusted to 100 rpm, room temperature (27 °C) and natural pH of the solution. The dye concentration was determined by UV Spectrophotometer (model K37-UVVIS from KASVI) and a quartz container with 10.0 mm optical path using 665 nm wavelength. The absorbance of the samples in water (control) was also determined to assess whether the adsorbents eliminated any residue into the aqueous solution that could affect the colorimetric analysis.

The adsorption percentage and the adsorption capacity at equilibrium time (after 24 hours of testing), qe (mg g

-1), were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively:

Where, Co and Ce are the initial concentration and equilibrium concentration of MB (mg L-1), respectively. V is the volume of solution containing MB (L), and m is the mass of adsorbent (g).

2.5. Isotherm Studies

The experimental equilibrium data were modeled by Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin models, which were implemented for fitting the dye adsorption isotherm data.

The parameters of each model were obtained by the nonlinear form presented in Eqs 3, 4 and, respectively.

Where Ce (mg L-1) is the equilibrium concentration, qe (mg g-1) is the amount of dye adsorbed at equilibrium, qm (mg g-1) and KL (L mg-1) are Langmuir constants related to adsorption capacity and energy of adsorption, respectively, KF (mg g-1)(L mg-1)1/n is Freundlich adsorption constant, 1/n is a measure of adsorption intensity, b (J mol-1) is Temkin constant related to adsorption heat, KT (L mg-1) is Temkin constant, R is the universal ideal gas constant (8.31 J mol-1 K-1), T (K) is the absolute adsorption temperature, KS is Sips isotherm constant, and nS is Sips isotherm exponent.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Characterization of Adsorbent Materials

The physical-chemical characterization data of BTP-R, BTP-300 and BTP-500 are summarized in

Table 2. BTP-R has an acidic pH (4.7 ± 0.0) and oxidizing characteristics (Eh = 140.0 ± 2.8 mV). As the material was subjected to the thermal process, an increase in its pH was noted, moving into the alkaline range, from 4.7 (BTP-R) to 10.2 (BTP-500). This change in pH is due to the carbonization process and increased salt concentration [

18], also evident in the rise in EC, where an increase from 397.0 to 1643.5 µS cm

-1 was noted (

Table 2). With the thermal process, a change in the redox potential of the material was also observed, changing to reducing when pyrolyzed at 500 °C. ΔpH represents the balance of charges present on the surface of the material. In the case of the materials evaluated, negative values were obtained, indicating a predominance of negative charges on the surface of the material, which favors the adsorption of cations.

Shahrum et al. (2024) evaluated biochars produced from mango pruning residue and found an alkaline pH (10.0) and high electrical conductivity (34,600 µS cm

-1) [

19]. The authors report that the temperature in the reactor was 667 °C, which may have resulted in higher EC and pH values. Additionally, the reducing Eh was also observed in pruning waste biochar [

20].

3.2. Influence of the Initial Concentration of Methylene Blue on the Adsorption Studies

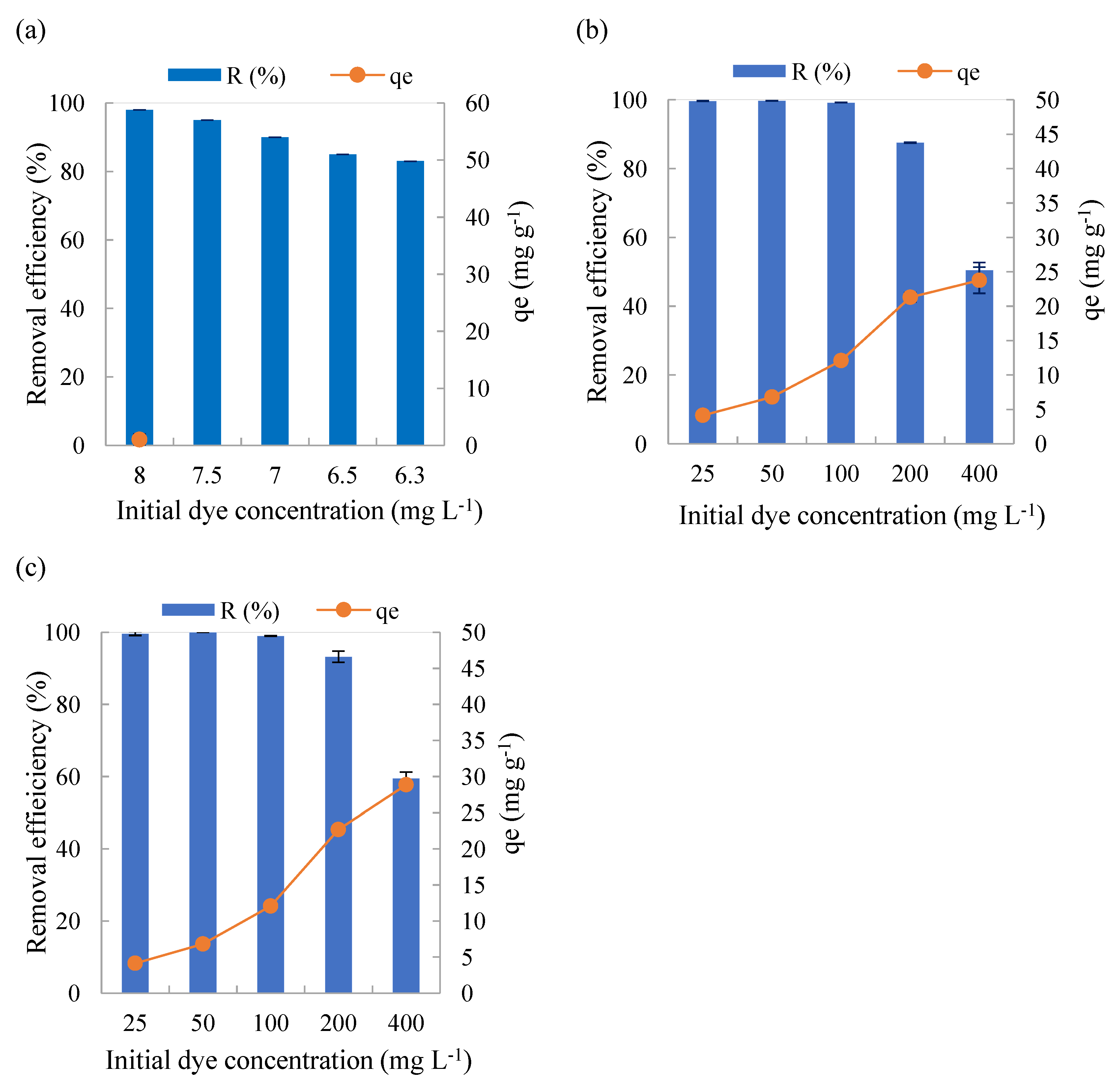

The results of the evaluation of the adsorptive processes aiming to identify the influence of the initial concentration of MB are available in

Figure 2.

BTP-R presented the highest removal rates in all tested concentrations, whereas BTP-300 and BTP-500 showed similar efficiencies. Although the high efficiencies indicates that BTP-R could potentially be used as an adsorbent, raw material is more perishable and subject to microbial activities.

The increase in the initial concentration of MB implied in a reduction in the removal efficiency (

Figure 2), evident for the initial concentrations of 200 mg L

-1 and 400 mg L

-1. It was found that BTP-500 resulted in slightly more efficient material for adsorption than BTP-300. BTP-300 efficiencies greater than 99% were obtained for the lowest initial concentrations (25 to 100 mg L

-1). At concentrations of 200 and 400 mg L

-1, the efficiency was reduced to less than 80%, however, the adsorptive capacity was higher (approximately 24 mg g

-1). In the case of BTP-500, an improvement in the removal efficiency of MB was observed, with efficiencies greater than 90% being obtained for concentrations of 25 to 200 mg L

-1 and an adsorption capacity of 29 mg g

-1 for the initial concentration of 400 mg L

-1.

The increase in the initial MB concentration resulted in an increase in the adsorptive capacity (

Figure 2). This can be attributed to the increase in the initial concentration gradient of MB, which is the main driving force of adsorption [

3].

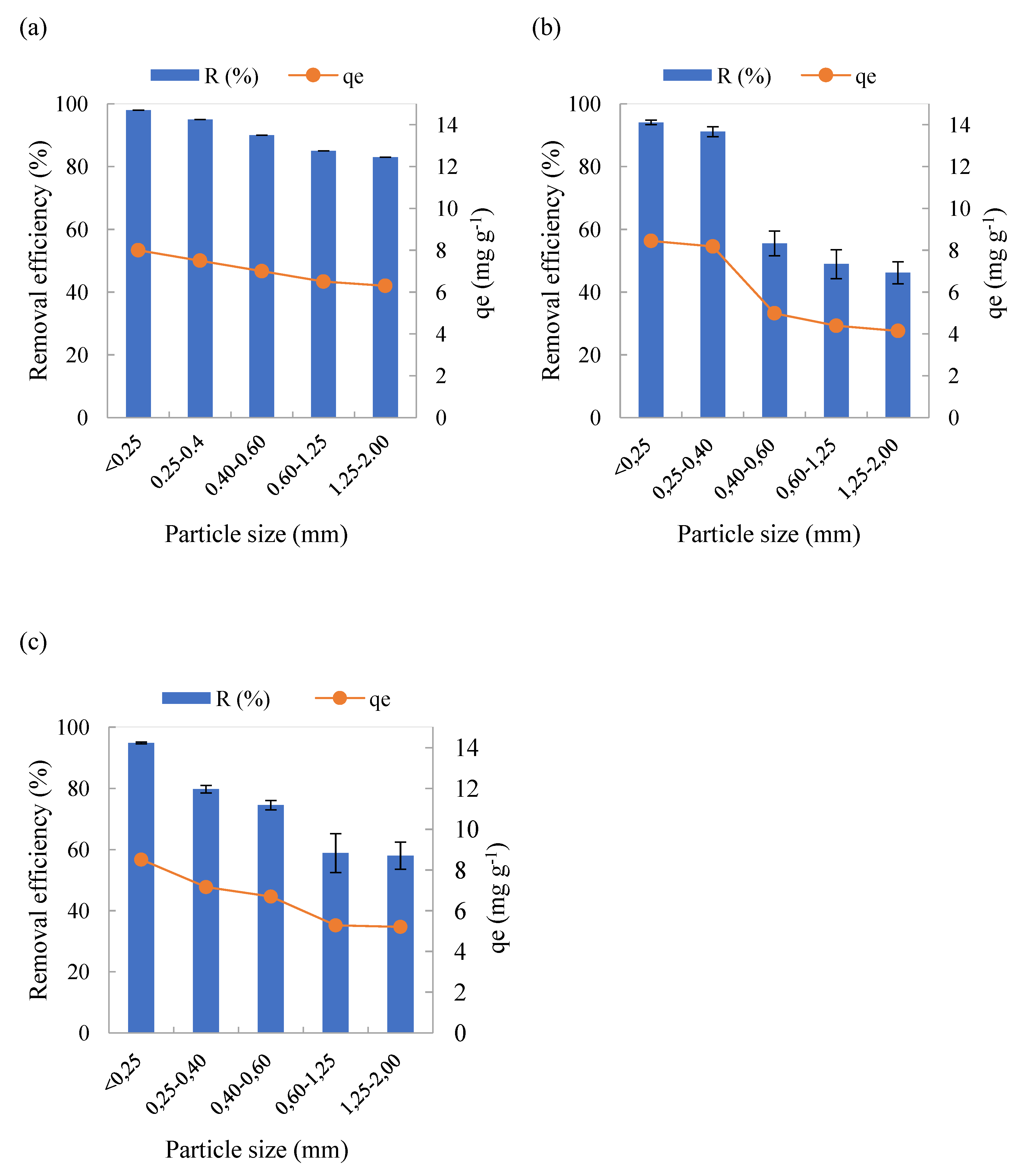

3.3. Influence of Adsorbent Particle Size on Adsorption Studies

In the BTP samples, it was found that when the average particle diameter was smaller, the removal efficiency was higher, implying a greater presence of adsorption sites in the finer particles (

Figure 3). When the particle diameter was inferior to 0.25 mm, efficiencies greater than 95% were obtained for BTP-R, BTP-300 and BTP-500 materials. On the other hand, for the largest particle sizes, lower efficiencies were observed, reaching less than 60% for materials with particle sizes from 0.60 to 2.00 mm. This indicates the importance of the particle size on the adsorption of MB onto BTP.

3.4. Isotherm Studies

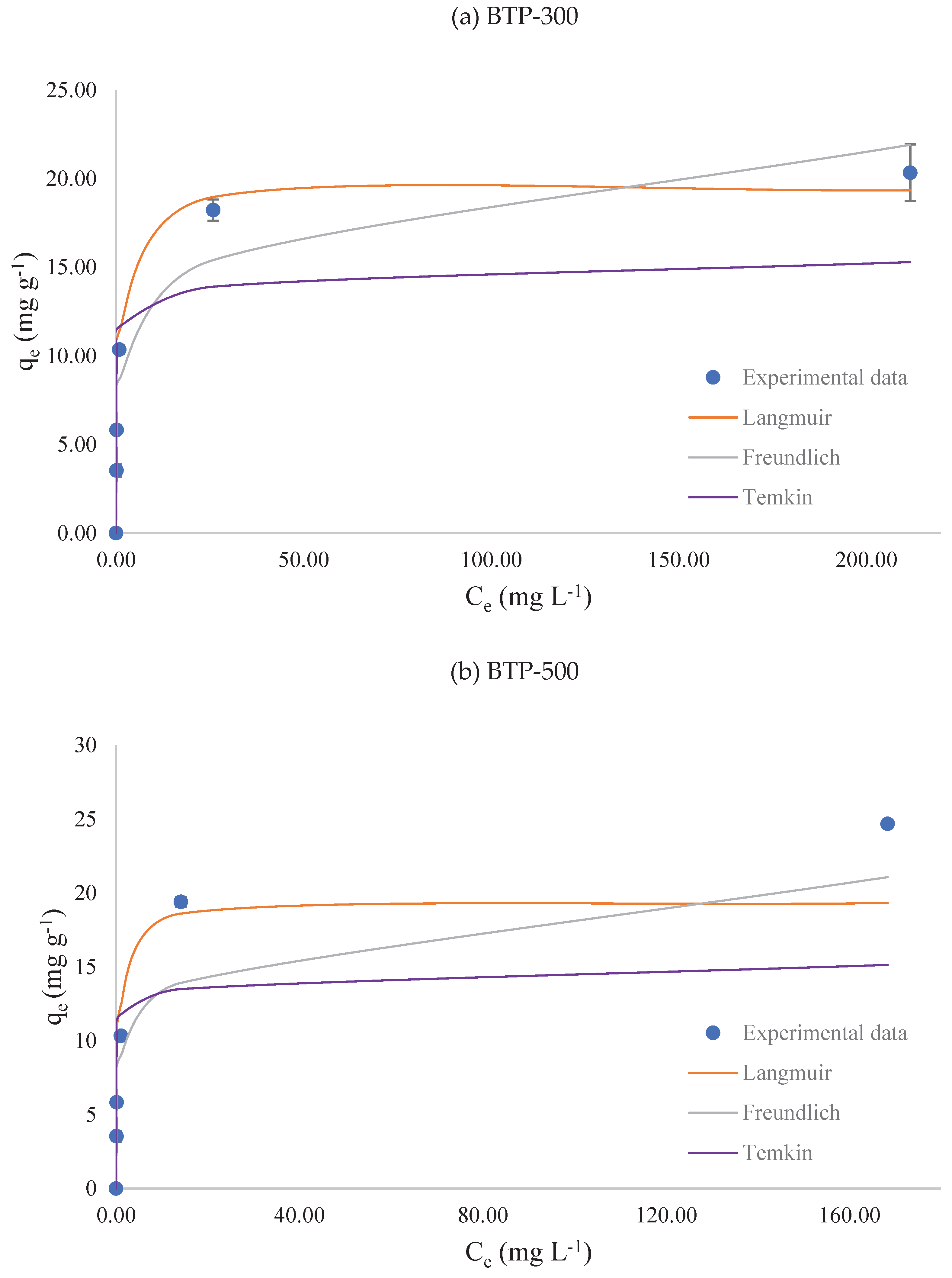

Three different types of adsorption isotherms were applied and analyzed towards the understanding of the association between BTP adsorption capacity and equilibrium of MB concentration in solution.

Figure 4 displays the results of data modeling with Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin and

Table 3 shows the isotherm parameters.

The adsorption parameters obtained by the modelling of experimental data of BTP-300 and BTP-500 were very similar. However, adsorption of MB onto BTP-300 is best described by Langmuir model (R² = 0.9870), whereas BTP-500 is best described by Freundlich model (R² = 0.9543).

Langmuir assumes monolayer adsorption and is widely used to predict q

m. The maximum (monolayer) adsorption capacity, q

m, was 19.4 mg g

-1 for BTP-300 and BTP-500 (

Table 3). The model considers both adsorption and desorption rates are equal at equilibrium and K

L reflects the ratio of adsorption to desorption rate constants, which is a measure of the strength at which adsorbate molecules are adsorbed onto the adsorbent surface. Thus, for the modelling of equilibrium data it is observed that the temperature of the thermochemical process did not affect q

m. In this case, the use of 300 °C temperature in the slow pyrolysis reaction produced a very similar product to that obtained by 500 °C process. This finding indicates that the torrefaction process yields in a lower energy intake and in an adsorbate of equal q

m of that obtained by a higher energy intake process. Thus, the use of this material is sustainable and is aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations.

Freundlich assumes multilayer adsorption on heterogenous surface, for which parameter n describes the energetic heterogeneity of the adsorbent surface. When n = 1, the amount of adsorbate uptake is proportional to its concentration; when 1 < n ≤ 10, a favorable adsorption is expected; and when 0 < n < 1, an unfavorable one is expected. In both materials, n = 5.97, thus, adsorption is favorable.

Finally, Temkin is interpreted by the declining energy in adsorption reactions. Parameter b is related to the adsorption heat; when it is lower than 8 kJ mol−1, surface adsorption occurs physically. The b obtained for BTP suggests surface adsorption occurs physically (b < 8 kJ mol−1).

The increase in the temperature of thermochemical process did not affect the Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin isothermal parameters, however, it did affect the physico-chemical parameters (

Table 2). When the temperature of the process is increased, it is expected the formation of a more porous structure, which can provide more adsorption sites due to the increase in the specific surface area. However, lower temperature biochar comprehends more oxygen-containing functional groups [

21], which can favor chemical covalent bonds. A more detailed surficial characterization is indicated to comprehend the affect of the themochemical process on these structures.

Thus, in this study it was found that 300 °C is a more suitable temperature for the production of BTP for the adsortion of MB, considering the lower energy intake and the high removal efficiency. Additionally, in the isotherm studies using particle size <0.60 mm, qm of BTP-300 and BTP-500 were equal, which indicates once again the benefit of using torrefied biochar.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the adsorption potential of two materials from mango and pitanga tree prunings (BTP-300 and BTP-500) was characterized and evaluated. Increasing the temperature of the thermochemical process (from 300 °C to 500 °C) made the materials alkaline and reducing. In the adsorption studies, it was found that the pyrolysis process and the initial concentration of MB directly influences the process. Increasing the temperature of the treatment resulted in a slight increase in the efficiency and adsorption capacity of the material. Whereas, increasing the initial concentration of MB resulted in a reduction in the efficiency of the process, especially considering the concentration of 400 mg L-1. The granulometry of the material directly influenced the adsorption process, with finer materials (mainly with a diameter of less than 0.25 mm) being more efficient in adsorbing MB from the solution. Both materials presented similar modeled parameters for Langmuir Freundlich and Temkin isotherm equations. The adsorption at equilibrium of MB onto BTP-300 and BTP-500 is best described by Langmuir and Freundlich models, and the modeled maximum adsorption capacity of both materials is 19.4 mg g-1, proving its efficiency in the adsorption of MB.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M. C. K.; E. L. R.; and V. G. S. R.; methodology, M. C. K.; B. S. C. V. and E. L. R.; formal analysis, M. C. K.; V. G. S. R.; B. S. C. V.; and E. L. R.; investigation, M. C. K.; V. G. S. R.; B. S. C. V.; and E. L. R.; resources, M. C. K.; V. G. S. R.; and E. L. R.; data curation, M. C. K.; V. G. S. R.; and E. L. R.; writing—original draft preparation, M. C. K.; writing—review and editing, M. C. K.; V. G. S. R.; and E. L. R.; visualization, M. C. K.; E. L. R.; and V. G. S. R.; supervision, , M. C. K.; V. G. S. R.; and E. L. R.; project administration, M. C. K.; funding acquisition, M. C. K.; V. G. S. R.; and E. L. R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) grant number 403924/2021-9 and Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo grant number 2023/12078-6.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BTP |

Biochar tree pruning |

| MB |

Methylene blue |

|

. |

Adsorption capacity at equilibrium |

|

Adsorption efficiency at equilibrium |

References

- Fdez-Sanromán, A.; Pazos, M.; Rosales, E.; Sanromán, M.Á. Advancing in wastewater treatment using sustainable electrosorbents. Curr Opin Electrochem 2024, 44, 101450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; et al. A review on recent advances of biochar from agricultural and forestry wastes: Preparation, modification and applications in wastewater treatment. J Environ Chem Eng 2024, 12, 111638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M. Sustainable production of activated carbon from indigenous Acacia etbaica tree branches employing microwave induced and low temperature activation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; et al. Mechanisms of adsorption and functionalization of biochar for pesticides: A review. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2024, 272, 116019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurav, R.; et al. Adsorptive removal of crude petroleum oil from water using floating pinewood biochar decorated with coconut oil-derived fatty acids. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 781, 146636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, M.J.; et al. Evaluation of the adsorption potential of biochars prepared from forest and agri-food wastes for the removal of fluoxetine. Bioresour Technol 2019, 292, 121973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; et al. The adsorption mechanisms of oriental plane tree biochar toward bisphenol S: A combined thermodynamic evidence, spectroscopic analysis and theoretical calculations. Environmental Pollution 2022, 310, 119819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiq, M.; Alazba, A.A.; Amin, M.T. Eco-friendly nanocomposite of manganese-iron and plant waste derived biochar for optimizing Pb2+ adsorption: A response surface methodology approach. Desalination Water Treat 2025, 322, 101091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.P.; Costa, J.; Martins, A.; Fonseca, A.M.; Neves, I.C.; Nunes, N. Zeolite Modification for Optimizing Fenton Reaction in Methylene Blue Dye Degradation. Colorants 2025, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lermen, A.M.; et al. A utilização de resíduos agroindustriais para adsorção do corante azul de metileno: Uma breve revisão / The use of agro-industrial waste for adsorption of the blue dye of methylene: A brief review. Brazilian Applied Science Review 2021, 5, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemodel, M.C.; Romão, E.L.; Bueno, T.; Papa, R. Adsorption of methylene blue on babassu coconut (Orbignya speciosa) mesocarp commercial biochar. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2024, 21, 1671–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, N.; et al. Use of Construction and Demolition Waste for the Treatment of Dye-Contaminated Water Toward Circular economy. 123AD. [CrossRef]

- Majd, M.M.; Kordzadeh-Kermani, V.; Ghalandari, V.; Askari, A.; Sillanpää, M. Adsorption isotherm models: A comprehensive and systematic review (2010−2020). Science of The Total Environment 2022, 812, 151334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da S, R.; da Silva, M.R.M.; Lourenço, M.A.D.S.; Kasemodel, M.C. Evaluation of the adsorption potential of iron mining tailing and its effect on raphanus sativus germination. Engenharia Sanitaria e Ambiental 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Lv, Z.; Wang, S. Effects of particle size on the adsorption behavior and antifouling performance of magnetic resins. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 11926–11935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- César, P.; et al. Revista e ampliada. [Online]. Available: https://www.embrapa.br.

- Técnico, B.; De Camargo, O.A.; Moniz, A.C.; Jorge, J.A.; JValadares, M.A.S. GOVERNO DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO SECRETARIA DE AGRICULTURA E ABASTECIMENTO COORDENADORIA DA PESQUISA AGROPECUÁRIA INSTITUTO AGRONÔMICO. 2009.

- Singh, R.; Goyal, A.; Sinha, S. Global insights into biochar: Production, sustainable applications, and market dynamics. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 194, 107663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrun, M.S.; et al. Design of a pyrolysis system and the characterisation data of biochar produced from coconut shells, carambola pruning, and mango pruning using a low-temperature slow pyrolysis process. Data Brief 2024, 52, 109997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, J.P.; Vaz, C.M.P.; Rodrigues, V.G.S. Characterization of mixtures of Brazilian Ultisol with urban pruning waste biochar at two different proportions. J Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 3610–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.H.; Song, M.; Kwon, E.E. Low-temperature biochar production from torrefaction for wastewater treatment: A review. Bioresour Technol 2023, 387, 129588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).