1. Introduction

Originally approved by the U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the 1960s, under the brand name Sinequan, the indications profile of doxepin has since expanded.[

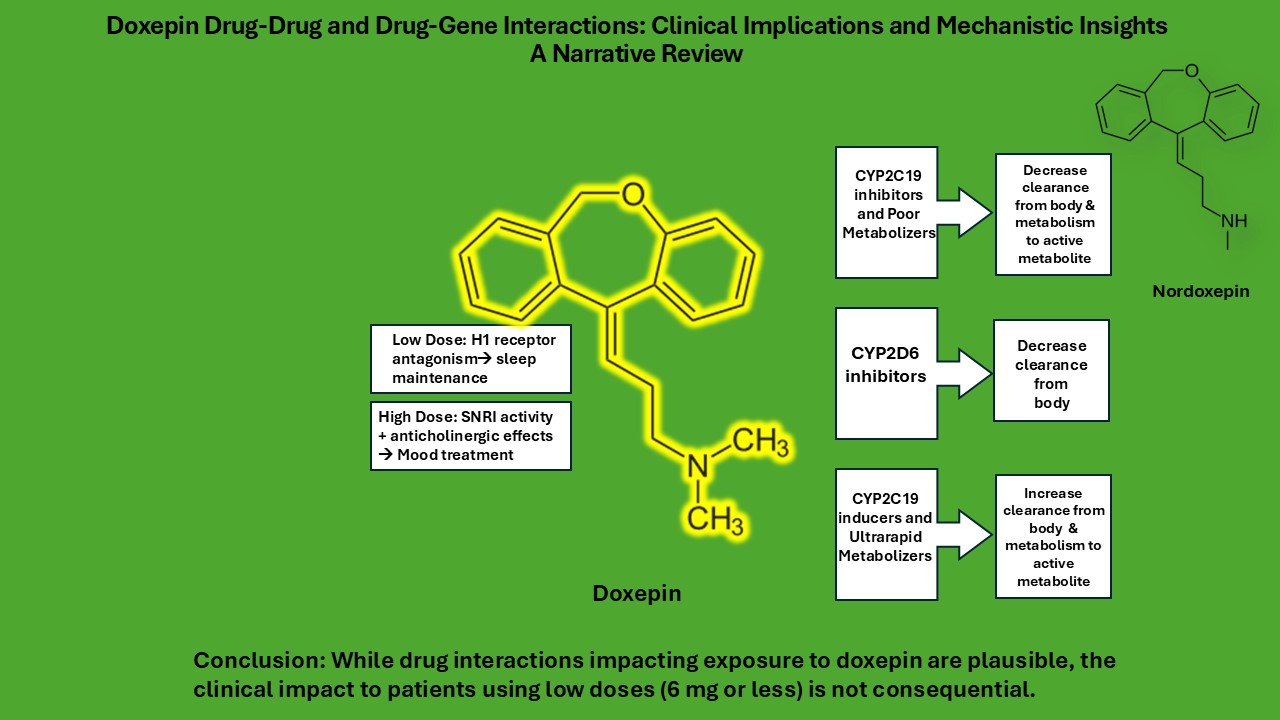

1] Doxepin’s affinity for different receptors, including histamine, alpha-1 adrenergic, and muscarinic receptors, varies with dose resulting in varying therapeutic effects.

1 This variability has contributed to its approval for various indications. At doses of 3 mg and 6 mg, doxepin functions as an antihistamine by strongly blocking H1 receptors. At these low doses doxepin is approved for insomnia under the brand name Silenor. At higher doses of 75-300mg/day, doxepin inhibits the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine. It also blocks alpha-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors at these high doses. Activity of doxepin at these receptors can lead to more pronounced side effects, which are not typically observed at the lower doses, such as dry mouth and constipation. A topical formulation of doxepin is approved under the brand name Zonalon for the treatment of epidermal pruritus. The exact mechanism of doxepin’s antipruritic effect is unknown but likely related to activity at H1 receptors. .[

1]With an expanding therapeutic profile, it is important to review the potential interactions of doxepin with other drugs.

According to its chemical structure doxepin is a tertiary amine. It undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism primarily via the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system, particularly through CYP2D6 and CYP2C19.[

2] The involvement of these enzymes not only contributes to the drug’s pharmacokinetic variability but also increases the potential for interactions with other medications metabolized by the same pathways and/or medications that inhibit those pathways. Doxepin is a mixture of Z(cis) and E(trans) isomers, usually in a Z:E,15:85 ratio.[

3] The E isomer is more selective as a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor while the Z isomer has over 5 times higher affinity for the H

1R receptor.[

3,

4] Both isomers are metabolized to the active metabolite, desmethyldoxepin (nordoxepin), through demethylation by CYP2C19 action.

The ratio of Z:E isomers for nordoxepin is 50:50, and, while less active in general than doxepin it is a more potent inhibitor of norepinephrine reuptake and less potent in its antiadrenergic, antihistamine and anticholinergic activity.[

5] The E-isomer also undergoes hydroxylation by CYP2D6. Drugs that inhibit CYP2C19 inhibit the metabolism of doxepin to its primary active metabolite while drugs that inhibit CYP2D6 would potentially increase plasma concentrations of the active metabolite and decrease clearance of both parent drug and resulting metabolites.

Understanding the drug interaction profile of doxepin is crucial, particularly given its usage in populations that often require polypharmacy, such as elderly patients or those with comorbid psychiatric conditions. The potential for adverse reactions with psychoactive medications necessitates a thorough evaluation of the literature.

This literature review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the current understanding of doxepin’s drug interactions, exploring both well-established and emerging data. By synthesizing findings from pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and clinical studies, this review will elucidate the mechanisms underlying these interactions and their potential clinical implications.

Low dose doxepin (3 and 6 mg) has demonstrated a robust treatment effect in adults with insomnia. Recent analyses have suggested that doxepin offers substantial benefits with limited adverse effects and is a highly attractive option relative to other options for the treatment of sleep maintenance difficulties. [

6,

7]Treatment guidelines confirm that doxepin is the only antihistamine-based treatment with adequate evidence. [

8]Given the large population of adults with sleep difficulties and the potential interest in doxepin as an evidence-based treatment, a better understanding of any relevant drug interactions is desirable.

2. Materials and Methods

This article is a narrative review. A literature search was performed using databases including PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar, with no restrictions on publication date.

3. Results

3.1. Doxepin CYP450 Enzyme Inhibition

There is currently no direct data available on doxepin’s CYP450 enzyme inhibition potential. However, based on estimates from structurally related drugs, it is possible that doxepin inhibits CYP2C19.[

9] At low doses (below 25mg) it is unlikely that this inhibition leads to significant clinical interactions.

3.2. CYP2D6/2C19 Inhibitors and Inducers

Doxepin is primarily metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system with both CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 playing a significant role in its biotransformation. As a result, drugs that inhibit these enzymes can impact doxepin’s pharmacokinetics, leading to elevated plasma concentrations and an increased risk of dose-dependent adverse effects. Among the most notable inhibitors of CYP2D6 are fluoxetine, sertraline, and cimetidine. Some CYP2C19 inhibitors include topiramate and fluvoxamine. Each of these drugs can potentially alter the safety and efficacy of doxepin therapy when used concurrently. While our search yielded few direct studies on the interaction between doxepin and CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 inhibitors, there have been studies on the coadministration of other drugs with similar metabolism to doxepin- desipramine, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, clomipramine, - and these inhibitors.

For doxepin, CYP2D6 metabolizes doxepin to E-hydroxydoxepin and transforms active metabolite desmethyldoxepin into E-hydroxydesmethyldoxepin. [

3]These metabolites retain some pharmacological activity and contribute to doxepin’s therapeutic effects. In general, these metabolites are considered less active than the parent drug. In the case of desipramine, an antidepressant closely related to doxepin, CYP2D6 also performs a hydroxylation reaction to transform desipramine into 2-hydroxydesipramine. [

10] This metabolite quantitatively and qualitatively is similar in biological activity to desipramine. Amitriptyline is converted to its primary active metabolite, nortriptyline, through CYP2C19 action. [

11] Nortriptyline, another related antidepressant, is also metabolized to an active metabolite, 10-hydroxynortryptline. [

11] Similarly to doxepin’s 2D6 metabolites, hydroxynortriptyline is less active than the parent drug. Clomipramine also uses the same metabolic pathways as doxepin. Both drugs are primarily metabolized by CYP2C19 into their primary metabolite and then further hydroxylated by 2D6 to a less active metabolite for clearance. They also both have direct metabolism of the parent drug by 2D6 into a less potent metabolite.[

12]

3.2.1. Fluoxetine

Fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Its primary mechanism of action involves inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin (5-HT) into presynaptic neurons, thereby increasing the concentration of serotonin in the synaptic cleft. [

13] From a pharmacokinetic perspective, fluoxetine has a long half-life, approximately 1-4 days for the parent drug and 7-15 days for its active metabolite, norfluoxetine. [

14] It is metabolized primarily by CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 and is a potent inhibitor of CYP2D6 and a moderate inhibitor of CYP2C19. [

13] Fluoxetine’s long half-life and its inhibition of doxepin’s primary metabolic pathway make it one of the most significant drugs of interest concerning doxepin drug interactions, however direct studies are lacking.

In one study, 12 male subjects were given a single dose of 50 mg desipramine or imipramine alone and in combination with 60 mg of fluoxetine. After 8 doses of fluoxetine, subjects receiving desipramine had a mean AUC of 1800 ng * hr/mL compared to 339 ng * hr/mL when taken alone. The Cmax when given with fluoxetine was 12ng/mL compared to 7.9ng/mL when taken alone. This represents a 1.5-fold increase in the Cmax. There were no increases in side effects observed in this study. [

15]

Another study that analyzed seven cases of fluoxetine coadministration with other drugs metabolized by CYP2D6, desipramine and nortriptyline, found that there was an increase in plasma levels of those drugs when administered with fluoxetine. The effect appeared to be greater with desipramine than nortriptyline. This is likely due to desipramine’s metabolite having similar activity to the parent drug unlike nortriptyline and doxepin’s metabolites. In one patient receiving fluoxetine and nortriptyline combination therapy, the plasma level of a 50 mg/day dose of nortriptyline and 40 mg dose of fluoxetine was 140 ng/mL. This was an increase from a level of 79 ng/mL on a 75mg dose of nortriptyline. Decreasing the dose of fluoxetine to 40 mg resulted in a plasma level of 113 ng/mL. Another patient on 150 mg dose of desipramine saw a plasma level increase from 183 ng/mL to 878 ng/mL after 6 months of 40 mg fluoxetine therapy. Decreasing the dose of desipramine to 30 mg led to a decrease in plasma level to 312 ng/mL after another 6 months. There was no side effect information provided. [

16]

A case study of an 87-year-old female found that fluoxetine decreases the hydroxylation of desipramine. Upon admission to the hospital, the patient was treated with 100 mg/day of desipramine due to the occurrence of anxiety, depression, and a sleep disturbance. This dose was increased from her outpatient dose of 75 mg/day. While her sleep and anxiety improved, depression remained. Fluoxetine was started at a dose of 20 mg/day. Seven days after initiation of fluoxetine, plasma desipramine increased to 357 ng/mL from a previous range of 180-199 ng/mL. [

16] Desipramine’s therapeutic range is 115-250 ng/mL with plasma levels >400 ng/mL generally regarded as toxic. [

18] After a 3 day hold the dose of desipramine was restarted at 50 mg/day and lowered again to 40 mg/day. The 40 mg/day dose of desipramine and 20mg/day dose of fluoxetine resulted in desipramine plasma levels of 202-233 ng/mL. The patient’s depressive symptoms were improved, and she was discharged on both fluoxetine and desipramine. There was no data on side effects presented in the case report. The major metabolite that 2D6 metabolizes desipramine into was present in a metabolite: desipramine ratio of 0.42 before fluoxetine was added. During combination therapy that ratio was reduced to 0.13. [

17]

One study discussed four cases where the combination therapy of clomipramine and fluoxetine showed increased benefits without increased side effects. [

19] In one of the cases the patient was on a 200 mg/ day dose of clomipramine and a 20 mg/day dose of fluoxetine. Although her clomipramine levels doubled, she experienced no side effects.

The results of these cases and research support the hypothesis that fluoxetine decreases the metabolism of doxepin and drugs with similar structural characteristics. They also support that the impact of this decrease is dose dependent and plasma level increases at lower doses would likely not result in a change in doxepin’s adverse effect profile.

3.2.2. Sertraline

Sertraline, an SSRI, is approved for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Like fluoxetine, sertraline inhibits serotonin reuptake into presynaptic neurons. While sertraline is primarily metabolized by CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, it is also a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6. [

20] When co-administered with doxepin, sertraline can lead to elevated levels of doxepin in the bloodstream. A phase I study in the NDA submission for low dose doxepin found that that the area under the curve, AUC0-t, AUC0-∞, and Cmax of doxepin were approximately 28%, 21%, and 32% higher, respectively, compared to doxepin alone. Although these differences are statistically significant, the variability in doxepin pharmacokinetics suggests that these differences are not clinically meaningful, and no dose adjustment is typically required. [

21]

3.2.3. Cimetidine

A particularly strong interaction with doxepin occurs when combined with cimetidine, a histamine (H2) receptor antagonist. Cimetidine is used to treat conditions like heartburn. The half-life of cimetidine is approximately 2 hours. Cimetidine is a potent inhibitor of several CYP enzymes, particularly CYP2D6 and CYP1A2. [

22] Cimetidine can increase the exposure of doxepin by approximately two-fold, leading to higher plasma concentrations at all time points in the pharmacokinetic profile. [

21] Notably, at 6- and 8-hours post-dosing, mean doxepin plasma concentrations were recorded at 0.70 ng/mL and 0.55 ng/mL when doxepin was administered alone, compared to 1.30 ng/mL and 0.99mL when administered with cimetidine. A study comparing co administration of doxepin with cimetidine and ranitidine, showed that unlike ranitidine, cimetidine significantly inhibited the biotransformation of doxepin. After the addition of 600 mg twice daily (bid) of cimetidine to a 50 mg doxepin regimen, the steady state plasma concentration of doxepin was increased from 4.7 ng/mL to 9 ng/mL. The elimination half-life of doxepin was also prolonged from 13.2 hours to 19.6 hours when cimetidine was administered. The levels of desmethyldoxepin (the active metabolite of doxepin) were not significantly affected, though its half-life also increased. [

23] Since the formation of doxepin’s primary metabolite is not impacted, cimetidine’s inhibition of doxepin is limited to the CYP2D6 pathway.

3.2.4. Fluvoxamine

Fluvoxamine, another SSRI, is used in treating several disorders including depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Inhibition of CYP2C19 by fluvoxamine can lead to higher serum concentrations of the parent drug. [

24] In a case series of twenty-two adults the combination of fluvoxamine and clomipramine yielded no reports of serotonin syndrome. Although serum clomipramine levels were elevated, the coadministration of fluvoxamine and clomipramine was well tolerated. [

25]

Similarly to doxepin and clomipramine, amitriptyline is converted to an active metabolite, nortriptyline, through CYP2C19 action. When amitriptyline was co-administered with fluvoxamine, the Cmax of the active metabolite was 74 ng/mL as compared with a Cmax of 63.4 ng/mL when administered alone. The Cmax of the parent drug remained relatively unchanged (66.8/70.4 ng/mL). Side effects were neither more frequent nor more severe in patients that received both amitriptyline and fluvoxamine compared with those receiving either drug alone. [

26]

3.2.5. Rifampin

Rifampin, a potent inducer of cytochrome P450 enzymes has the potential to impact the metabolism of doxepin. [

27] Induction of CYP2C19 can accelerate the clearance of doxepin and increase Cmax of the active metabolite, nordoxepin. A study of the interaction of rifampin with nortriptyline provides some insight on what that interaction may look like. A 51-year-old patient with tuberculosis who was given combined antituberculosis therapy including 600 mg rifampin daily was subsequently diagnosed with depression. The patient was started on 10 mg of nortriptyline and slowly titrated up. To reach therapeutic levels, the nortriptyline needed to be titrated up to 175 mg daily. A typical dose of nortriptyline for the treatment of depression is 75-100 mg/ day. The level of nortriptyline after the tuberculous therapy was stopped was 193 nmol/L. Once the nortriptyline was reduced to 75 mg per day, the patient’s serum levels returned to therapeutic range. The only adverse drug event noted in this case was sudden drowsiness 3 weeks after TB therapy discontinuation prompting a repeat serum check that showed a level of 671 nmol/L. [

28]

3.3. Other Drug Interactions

3.3.1. Tolazamide

There have been two reported cases of hypoglycemia in patients taking doxepin alongside tolazamide, a sulfonylurea used to manage type 2 diabetes [

29,

30]. Tolazamide works by stimulating insulin release from pancreatic beta cells, lowering blood glucose levels. When combined with doxepin, this hypoglycemic effect may be potentiated. Although the exact mechanism is unclear, doxepin has been shown in some studies to increase insulin sensitivity and enhance the hypoglycemic effects of insulin in animal models. [

31] Tolazamide is no longer marketed in the US and is not in scope for this review.

3.3. Pharmacogenomics

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how an individual’s genetic makeup influences their response to medications. By analyzing variations in genes that encode drug-metabolizing enzymes, transporters, and receptors, pharmacogenomics helps identify potential risks for adverse drug reactions or non-optimal therapeutic outcomes.

CYP2D6 poor metabolizers (PMs) may have higher plasma concentrations of nordoxepin while CYP2C19 PMs may have higher plasma concentrations of the parent drug. Outcomes for these individuals may be similar to those taking strong inhibitors of the enzymes, such as fluoxetine. [

32] An estimated 1-5% of the US population are CYP2C19 PMs. [

33]In a study of CYP2C19 PM a 2-fold decrease in clearance of doxepin was observed. Nordoxepin was still present as other enzymes, CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP3A4, play a role in the demethylation of doxepin. [

2] Current guidelines recommend a 50% reduction in the starting dose of doxepin in PMs. [

2]This recommendation is of relevance when considering the higher doses of doxepin used for depression. While there are no recommendations for low dose doxepin, there are for another similar drug at low doses, amitriptyline. At low doses amitriptyline can be used for the treatment of neuropathic pain and no dose modifications are recommended in CYP2D6 or CYP2C19 PMs. [

33] In the case of Ultra Rapid Metabolizers (UM), the efficacy of doxepin may be a concern. As seen in the case of the patient taking rifampin and nortriptyline, in the presence of increased enzyme action higher doses of the drug are needed to achieve therapeutic efficacy. [

28]

Screening for these polymorphisms is typically reserved for situations where initiating a drug significantly influenced by genetic factors is being considered. The FDA labeling for some drugs clearly states guidelines for dosing and/or testing recommendations. However, doxepin’s label does not include such recommendations.

4. Discussion

Doxepin’s primary metabolism via CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 makes it susceptible to interactions with drugs that inhibit those enzymes. However, studies on these specific interactions are limited.

While the information presented in this review relies on comparisons between doxepin and similar drugs, it is important to note some differences between these drugs that may affect the outcomes of potential drug interactions.

Table 1 compares the role of CYP450 enzymes in the metabolism of these drugs. For all drugs listed, the CYP2D6 hydroxylated metabolites are less active than parent drug. Doxepin is more potent than all listed drugs at H1 receptor antagonism. This receptor is responsible for its wake-inhibiting effects. At doses below 25 mg doxepin has little to no anticholinergic effects. [

36] Doxepin’s receptor profile and side effect profile are dose dependent. Lower doses of doxepin such as those used for insomnia have an extremely limited potential for consequential interactions.

In the case of the patient receiving a CYP2C19 inducer and nortriptyline, the nortriptyline dose needed to be increased significantly before the patient responded to treatment. As shown in

Table 1, although doxepin and nortriptyline are both converted to an active metabolite by CYP2C19, nortriptyline’s metabolite is not its primary metabolite. Doxepin’s metabolite also exhibits greater norepinephrine reuptake inhibition than doxepin and contributes to its therapeutic profile as an antidepressant.

As

Table 2 shows, many of the drug interactions do not lead to increased safety concerns even at very high doses of medications. Patients on low dose doxepin would not routinely require dose adjustments. Furthermore, some of the medications that doxepin interacts with have limited clinical use and the risk of concomitant use is therefore low. Despite the recall of ranitidine in 2019, use of cimetidine remains extremely low. [

37]Rifampin is FDA approved for the treatment of tuberculosis. In 2023 there were 9,633 reported TB cases in the US representing a rate of 2.9 cases per 100,000 persons.[

38] Rifampin’s specialized use in a specific infection like TB lends to its low frequency. Rifampin also interacts with many other drugs and a patient that is being treated with this medication would be closely monitored. Although listed on doxepin’s drug label, tolazamide is no longer marketed in the US. [

39]

5. Conclusions

Given the widening options for the treatment of depression and mood disorders, the use of doxepin is expected to be largely limited to low doses for the treatment of sleep maintenance difficulties. The safety profile of lower doses of doxepin (up to 6 mg/day) are inherently less concerning than higher doses used for mood disorders. However, the impact of any relevant drug interactions or metabolic challenges should be understood and put into context. This review paper has collected the relevant literature and suggests that virtually any circumstance related to low dose doxepin would not lead to any substantive clinical safety concern. Low doses of doxepin can be broadly used in the appropriate situations without concern for drug interactions or metabolic disposition that would have any meaningful consequences.

References

- Almasi, A.; Patel, P.; Meza, C. E. Doxepin. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542306/.

- Kirchheiner, J.; Meineke, I.; Muller, G.; Roots, I.; Brockmoller, J. Contributions of CYP2D6, CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 to the biotransformation of E- and Z-doxepin in healthy volunteers. Pharmacogenetics 2002,12(7),571–580. [CrossRef]

- PharmGKB. PharmGKB. https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA165981686/overview.

- Kaneko, H.; Korenaga, R.; Nakamura, R.; Kawai, S.; Ando, T.; Shiroishi, M. Binding characteristics of the doxepin E/Z-isomers to the histamine H1 receptor revealed by receptor-bound ligand analysis and molecular dynamics study. Journal of Molecular Recognition 2024, 37 (5). [CrossRef]

- Foye, W. O.; Lemke, T. L.; Williams, D. A. Foye’s Principles of Medicinal Chemistry; 2012.

- Cheung, J. M. Y.; Scott, H.; Muench, A.; Grunstein, R. R.; Krystal, A. D.; Riemann, D.; Perlis, M. Comparative short-term safety and efficacy of hypnotics: A quantitative risk–benefit analysis. Journal of Sleep Research 2023, 33 (4). [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J. M. Y.; Scott, H.; Muench, A.; Grunstein, R. R.; Krystal, A. D.; Riemann, D.; Perlis, M. Comparative short-term safety and efficacy of hypnotics: A quantitative risk–benefit analysis. Journal of Sleep Research 2023, 33 (4). [CrossRef]

- Sateia, M. J.; Buysse, D. J.; Krystal, A. D.; Neubauer, D. N.; Heald, J. L. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2017, 13 (02), 307–349. [CrossRef]

- Gillman, P. K. Tricyclic antidepressant pharmacology and therapeutic drug interactions updated. British Journal of Pharmacology 2007, 151 (6), 737–748. [CrossRef]

- PharmGKB. PharmGKB. https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA162359940/overview.

- PharmGKB. PharmGKB. https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA166163647.

- PharmGKB. PharmGKB. https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA165960076/pathway.

- PharmGKB. PharmGKB. https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA161749012.

- Altamura, A. C.; Moro, A. R.; Percudani, M. Clinical pharmacokinetics of fluoxetine. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 1994, 26 (3), 201–214. [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, R. F.; Peyton, A. L.; Lemberger, L. Quantification and mechanism of the fluoxetine and tricyclic antidepressant interaction. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 1992, 51 (3), 239–248. [CrossRef]

- Von Ammon Cavanaugh, S. Drug-Drug Interactions of Fluoxetine with Tricyclics. Psychosomatics 1990, 31 (3), 273–276. [CrossRef]

- Suckow, R. F.; Roose, S. P.; Cooper, T. B. Effect of fluoxetine on plasma desipramine and 2-hydroxydesipramine. Biological Psychiatry 1992, 31 (2), 200–204. [CrossRef]

- Hashim, I. A. Therapeutic drugs and toxicology testing. In Elsevier eBooks; 2023; pp 375–418. [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.; Horn, E.; Jones, T. T. The benefits of Clomipramine-Fluoxetine combination in obsessive Compulsive disorder. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 1993, 38 (4), 242–243. [CrossRef]

- PharmGKB. PharmGKB. https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA166181117.

- CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH. Biopharmaceutics review; report; Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 2009. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2010/022036Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf.

- Somogyi, A.; Gugler, R. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Cimetidine. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 1983, 8 (6), 463–495. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, D. L.; Remillard, A. J.; Haight, K. R.; Brown, M. A.; Old, L. The influence of cimetidine versus ranitidine on doxepin pharmacokinetics. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1987, 32 (2), 159–164. [CrossRef]

- Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs). In Elsevier eBooks; 2015; pp 317–337. [CrossRef]

- Szegedi, A.; Wetzel, H.; Leal, M.; Härtter, S.; Hiemke, C. Combination treatment with clomipramine and fluvoxamine: drug monitoring, safety, and tolerability data. PubMed 1996, 57 (6), 257–264.

- Vezmar, S.; Miljkovic, B.; Vucicevic, K.; Timotijevic, I.; Prostran, M.; Todorovic, Z.; Pokrajac, M. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of fluvoxamine and amitriptyline in depression. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 2009, 110 (1), 98–104. [CrossRef]

- Niemi, M.; Backman, J. T.; Fromm, M. F.; Neuvonen, P. J.; Kivist, K. T. Pharmacokinetic Interactions with Rifampicin. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 2003, 42 (9), 819–850. [CrossRef]

- Bebchuk, J. M.; Stewart, D. E. Drug Interaction between Rifampin and Nortriptyline: A Case Report. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 1991, 21 (2), 183–187. [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, H. Z.; Kaur, J.; Stout, S. C.; Drake, T. Doxepin-Associated hypoglycemia in an ambulatory nondiabetic patient. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders 2023, 25 (4). [CrossRef]

- True, B. L.; Perry, P. J.; Burns, E. A. Profound hypoglycemia with the addition of a tricyclic antidepressant to maintenance sulfonylurea therapy [published erratum appears in Am J Psychiatry 1987 Nov;144(11):1521]. American Journal of Psychiatry 1987, 144 (9), 1220–1221. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.; Shakarwal, M. K.; Kumar, A.; Jaju, B. P. Modulation of glucose homeostasis by doxepin. PubMed 1992, 14 (1), 61–71.

- Klein, M. D.; Williams, A. K.; Lee, C. R.; Stouffer, G. A. Clinical utility of CYP2C19 genotyping to guide antiplatelet therapy in patients with an acute coronary syndrome or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology 2019, 39 (4), 647–652. [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J.; Sangkuhl, K.; Swen, J.; Ellingrod, V.; Müller, D.; Shimoda, K.; Bishop, J.; Kharasch, E.; Skaar, T.; Gaedigk, A.; Dunnenberger, H.; Klein, T.; Caudle, K.; Stingl, J. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline (CPIC) for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of tricyclic antidepressants: 2016 update. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2016, 102 (1), 37–44. [CrossRef]

- Krystal, A. D.; Richelson, E.; Roth, T. Review of the histamine system and the clinical effects of H1 antagonists: Basis for a new model for understanding the effects of insomnia medications. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2013, 17 (4), 263–272. [CrossRef]

- Bertilsson, L.; Mellström, B.; Sjöqvist, F. Pronounced inhibition of noradrenaline uptake by 10-hydroxymetabolites of nortriptyline. Life Sciences 1979, 25 (15), 1285–1292. [CrossRef]

- Balant-Gorgia, A. E.; Gex-Fabry, M.; Balant, L. P. Clinical pharmacokinetics of clomipramine. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 1991, 20 (6), 447–462. [CrossRef]

- Gunning, R.; Chu, C.; Nakhla, N.; Kim, K. C.; Suda, K. J.; Tadrous, M. Major shifts in acid suppression drug utilization after the 2019 ranitidine recalls in Canada and United States. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 2023, 68 (8), 3259–3267. [CrossRef]

- National data. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/tb-surveillance-report-2023/summary/national.html#:~:text=In%202023%2C%20the%20United%20States,to%20the%20COVID%2D19%20pandemic.

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Tolazamide. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501118/.

| Table 1 |

| Drug |

Primary CYP Enzyme |

Metabolitea |

Comparison of metabolite activity to Parent Drug b |

Comparison of parent drug to doxepin c |

| Doxepin |

2D6 |

E-Hydroxydoxepin, E-hydroxydesmethyldoxepin |

Low |

|

| 2C19 |

E/Z-Desmethyldoxepin (nordoxepin) * |

stronger inhibitor of norepinephrine reuptake and weaker inhibitor of serotonin reuptake |

|

| Clomipramine |

2D6 |

Hydroxylated metabolites |

Low |

less potent at H1 and NE receptors , slightly less potent at α1 ,more potent at Musc, 5-HT receptors |

| 2C19 |

Desmethylclomipramine* |

stronger inhibitor of norepinephrine reuptake and weaker inhibitor of serotonin reuptake |

|

| Amitriptyline |

2D6 |

Hydroxyamitriptyline |

Low |

Slightly less potent at H1, α1, less potent at NE more potent at 5-HT and Musc receptors. |

| 2C19 |

Nortriptyline * |

Stronger inhibitor of norepinephrine reuptake and weaker inhibitor of serotonin reuptake |

|

| Nortriptyline |

2D6 |

10-hydroxynortryptiline* |

Low |

less potent at 5-HT, α1, H1 receptors , more potent at Musc, NE and α1 receptors |

| 2C19 |

Desmethylnortryptiline |

Low |

|

| Imipramine |

2D6 |

Desipramine* |

Stronger inhibitor of norepinephrine and weaker inhibitor of serotonin reuptake |

less potent at α1, NE, H1 receptors , more potent at 5-HT, Musc |

| |

2C19 |

Hydroxylated metabolites |

Low |

|

| Desipramine |

2D6 |

2-hydroxydesipramine * |

Low |

Less potent at H1, α1, muscarinic receptors. More potent 5-HT, NE |

| |

2C19 |

E-Hydroxydoxepin, E-hydroxydesmethyldoxepin |

Low |

|

| * Primary active metabolite |

a Data adapted from:3,7,8,9

b Data adapted from: 5,6,31,32

c Data adapted from 6

d Abbreviations: 5-HT, serotonin receptor; NE, norepinephrine; H1, Histamine type 1, Musc; acetylcholine muscarinic; α1, α1 adrenoreceptor

d

|

Table 2.

Summary of Interactions.

Table 2.

Summary of Interactions.

| Study Name |

Interacting Drugs |

Results |

Author Conclusions |

Relevance to Low Dose Doxepin |

Bergstrom et al. (1992)

|

Desipramine 50 mg and Fluoxetine 60mg |

There was a 1.5-fold increase in Cmax and no increases in side effects. |

Fluoxetine causes an inhibition of tricyclic 2-hydroxylation and may decrease first-pass and systemic metabolism. |

Fluoxetine likely decreases doxepin metabolism but at low doses this interaction would not yield safety concerns |

Von Ammon Cavanaugh (1990)

|

Desipramine and Fluoxetine

Amitriptyline and Fluoxetine

|

There was an increase in plasma levels of desipramine and amitriptyline. The effect was more profound with desipramine than amitriptyline. |

Suckow et al. (1992)

|

Desipramine and Fluoxetine |

The patient’s depressive symptoms improved, and they were discharged on the combination therapy.

|

Browne et al. (1993)

|

Clomipramine and Fluoxetine |

The combination therapy showed increased benefits without increased side effects. |

| 022036Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf |

Doxepin 6mg and Sertraline 50mg |

Doxepin Cmax increased by 32% when given with sertraline. |

|

Not clinically meaningful and requires no dose adjustments |

| 022036Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf |

Doxepin 6mg and Cimetidine 300mg bid |

There was a 2-fold increase in doxepin exposure |

Dose of doxepin should be limited to 3mg when co administered with cimetidine |

Although a 2-fold increase in exposure may be clinically significant, doxepin’s therapeutic profile suggest that a low dose with 2x exposure would not yield significant safety concerns. |

Sutherland et al. (1987)

|

Doxepin 50 and Cimetidine 600 mg bid |

Plasma concentration of doxepin increased from 4.7 ng/mL to 9 ng/mL |

Cimetidine inhibits the biotransformation of doxepin. |

Szegedi et al. (1996)

|

Clomipramine and Fluvoxamine |

Serum clomipramine levels were elevated, and the combination therapy was well tolerated.

|

The pharmacokinetic interactions between fluvoxamine and clomipramine may be well tolerated in a majority of patients. |

While fluvoxamine may reduce the metabolism of doxepin the impact on treatment and safety would not be harmful. |

Vezmar et al. (2009)

|

Amitriptyline 75mg and Fluvoxamine 100mg |

The Cmax of amitriptyline remained unchanged while the

Cmax of its metabolite increased from 7 to 17.6. There were no significant differences in adverse effects. Patients with major depression had stronger onset of clinical response. |

pharmacokinetic interaction between fluvoxamine and amitriptyline resulting in impaired metabolism of the latter. However, no significant impact of the interaction on treatment safety was observed. |

Bebchuk and Stewart (1991)

|

Nortriptyline and Rifampin |

Nortriptyline titrated from 10 mg to 175 mg for therapeutic effect

Drowsiness at serum level of 671 |

Higher than expected doses of nortriptyline were required to obtain a therapeutic drug level while the patient was receiving rifampin. |

Patients on low dose doxepin may not receive therapeutic benefits from doxepin during rifampin treatment |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).