Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

14 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Determination of Chlorophylls a and b Contents

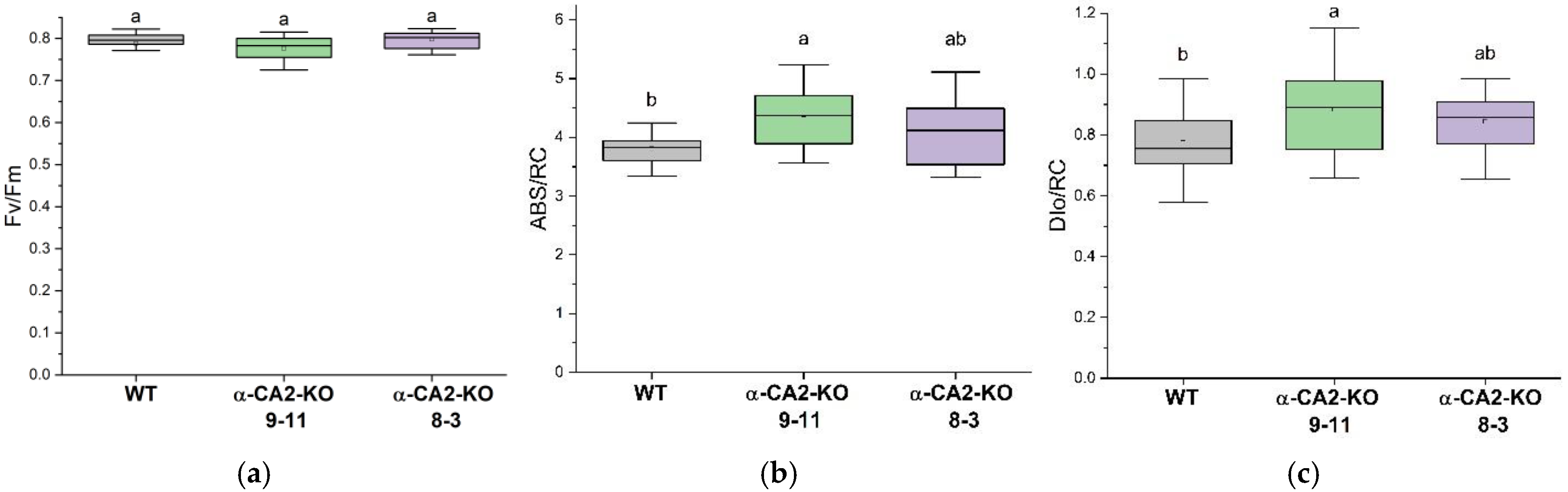

2.2. The Assessment of the Parameters of OJIP Kinetics

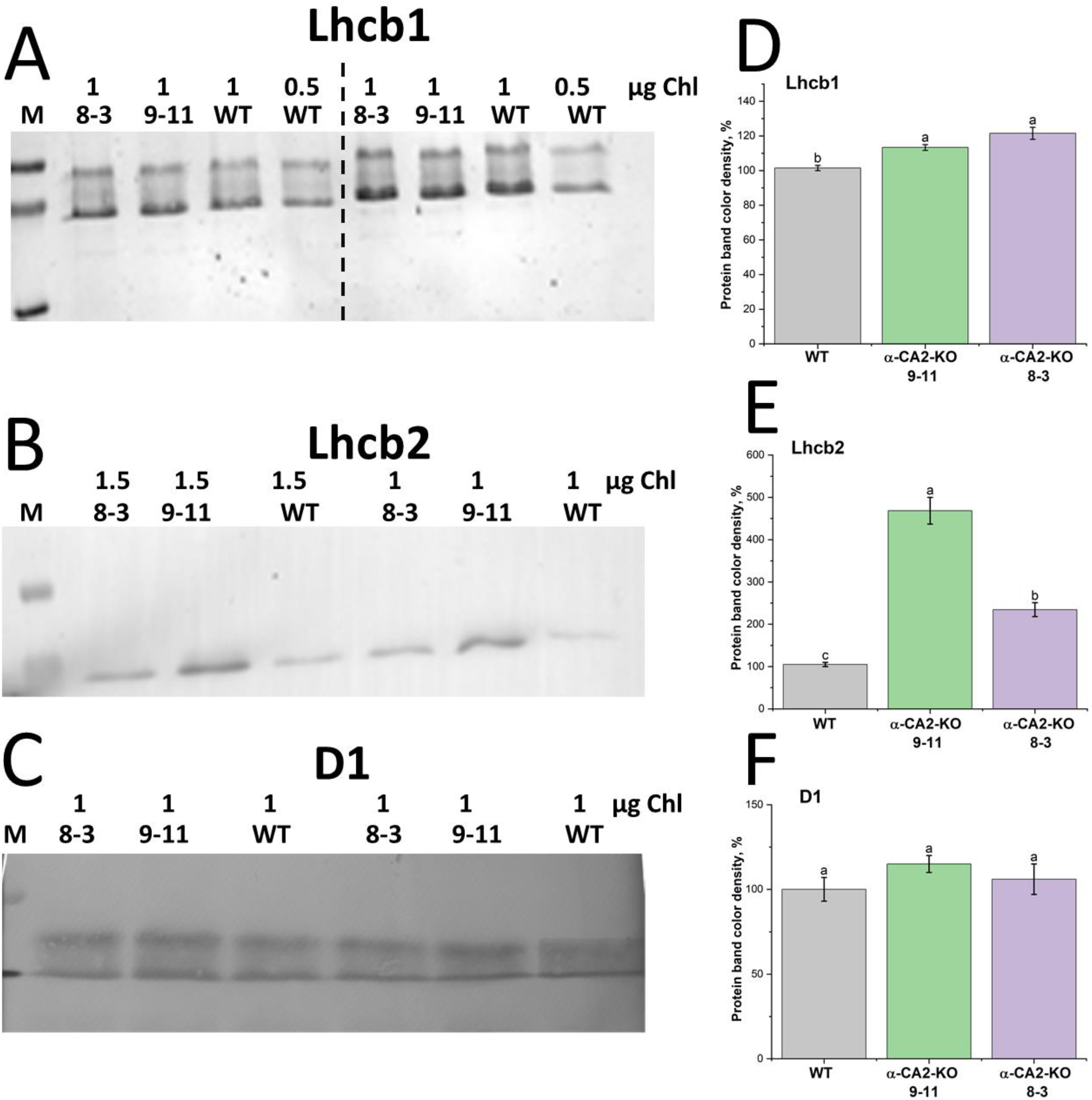

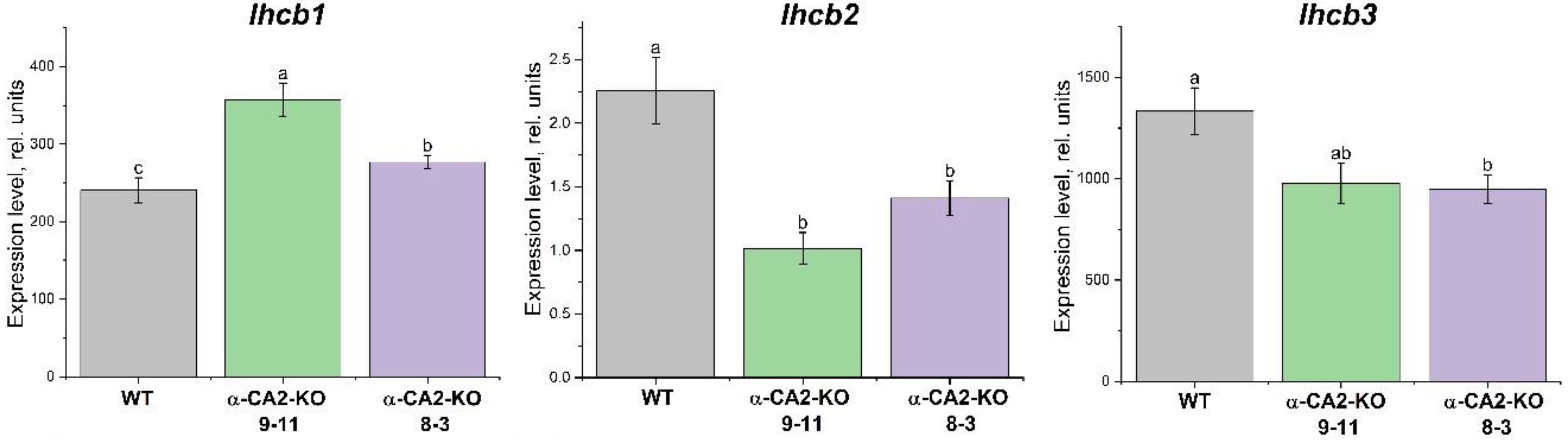

2.3. Estimation of the Amount of lhcb1, Lhcb2 and D1 Proteins and Evaluation of the Expression Level of Genes Encoding PSII Antenna Proteins

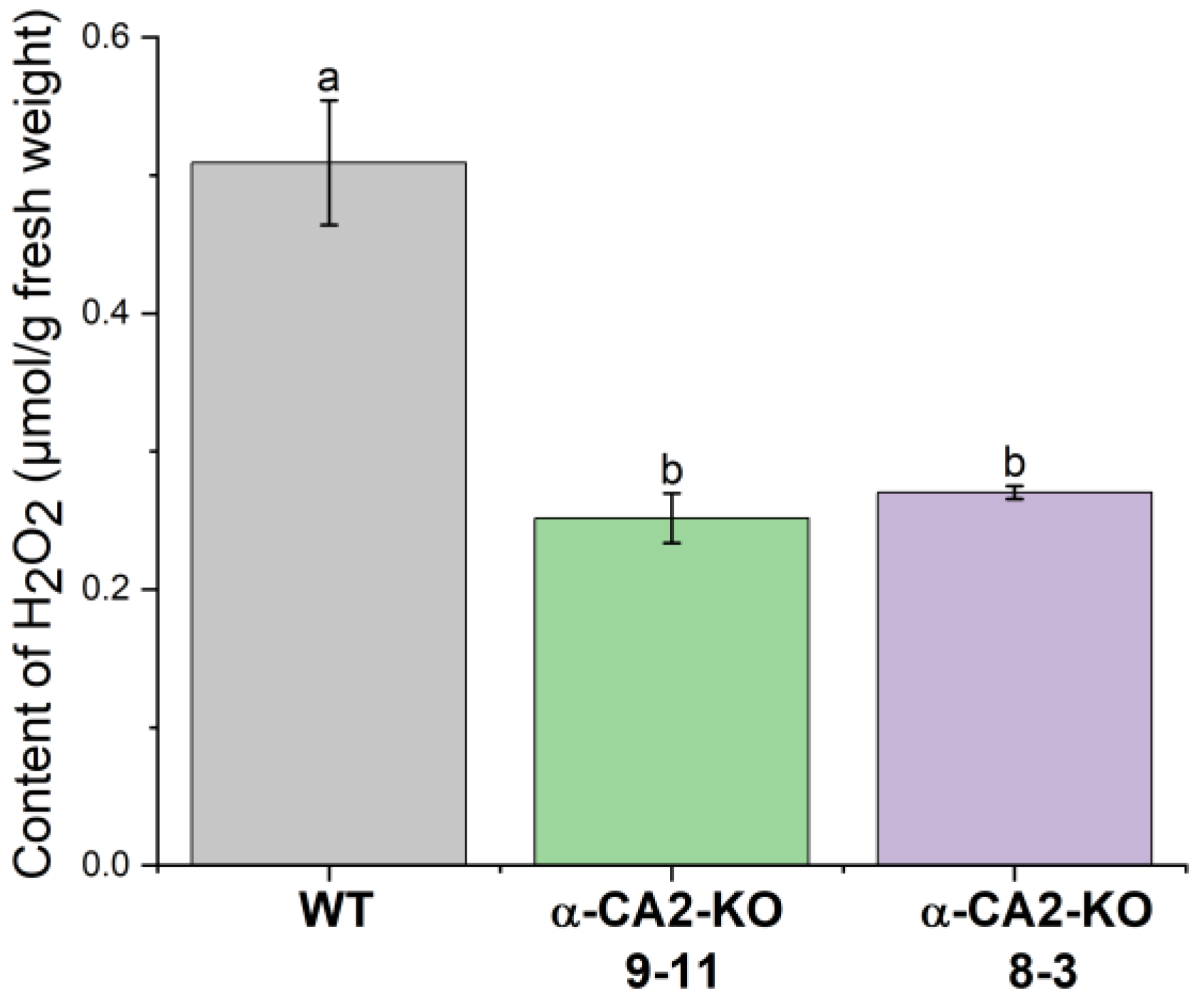

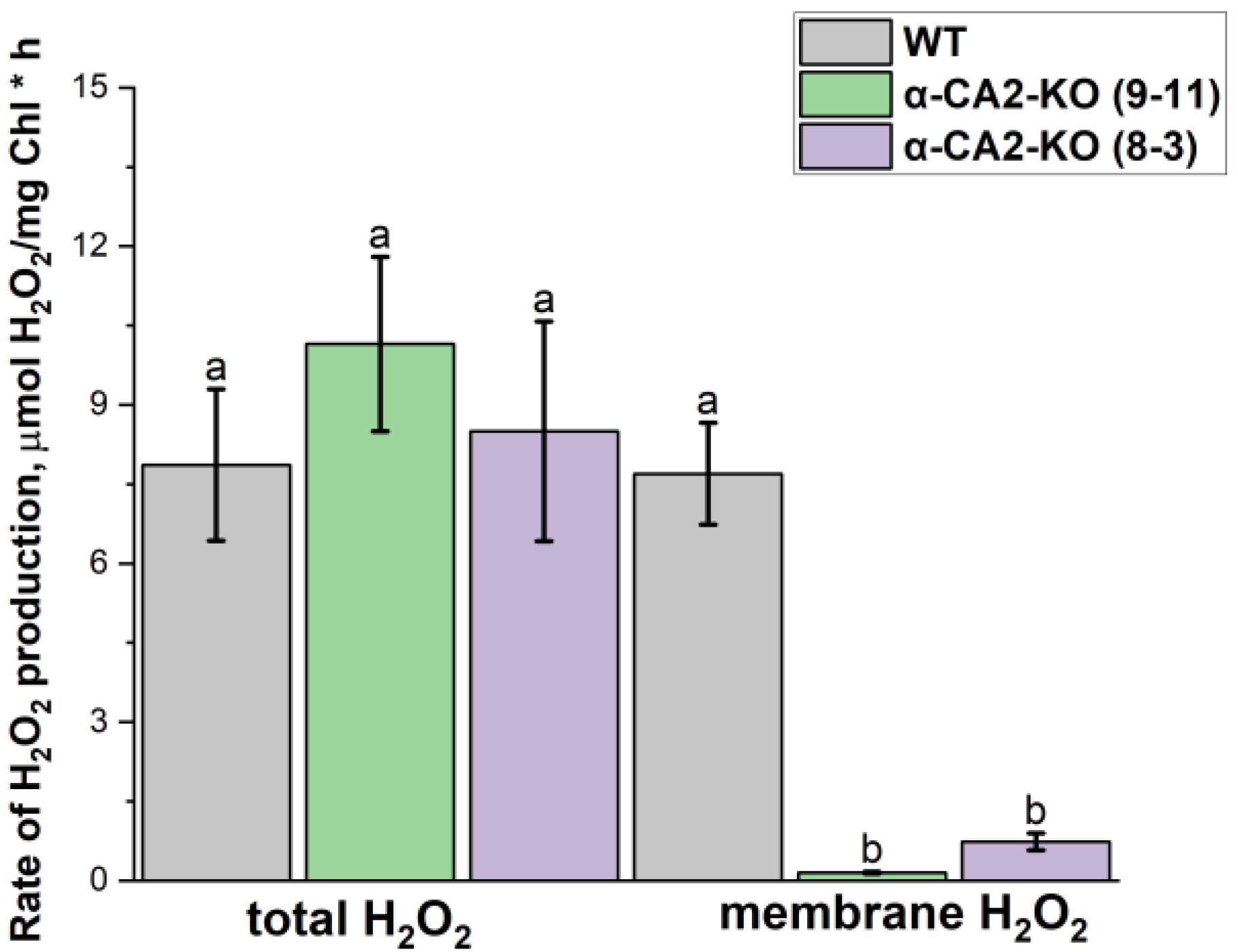

2.4. The Measurement of Hydrogen Peroxide Production

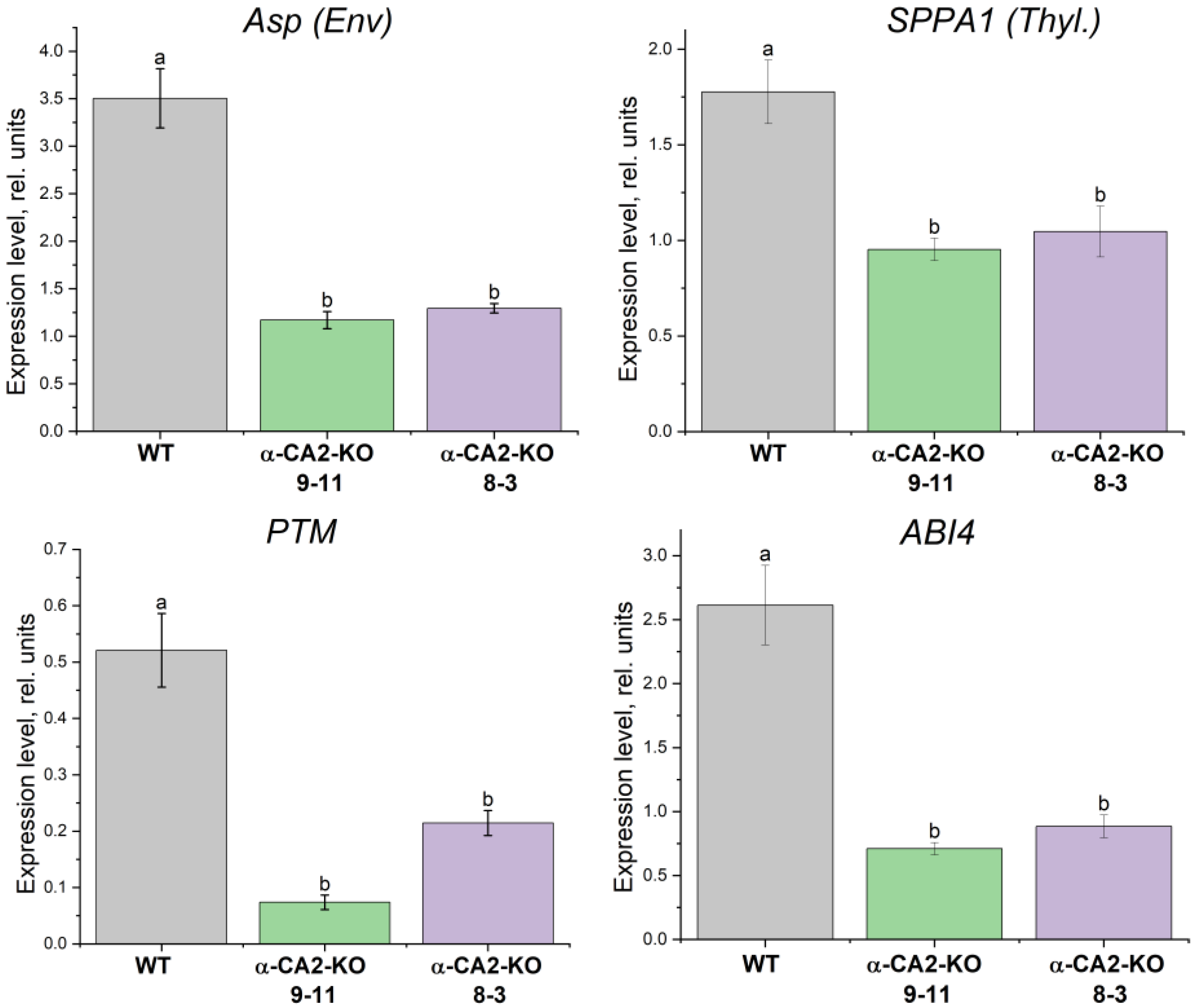

2.5. Evaluation of the Expression Level of Genes Encoding Proteins Included in Retrograde Signalling

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

4.3. Determination of Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Content

4.4. Western Blot Analysis

4.5. Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR

4.6. Measurement of Hydrogen Peroxide Content in Leaves

4.7. Measurement of the Light-Induced Changes of Oxygen Concentration in a Suspension of Isolated Thylakoids

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| α-CA2-KO | α-CA2 knockout |

| WT | wild type |

| CA | carbonic anhydrase |

| LHCII | light-harvesting complex of photosystem II |

| PETC | photosynthetic electron transport chain |

| TF | transcription factor |

| PQ | plastoquinone |

| PQH2 | plastohydroquinone |

| PSII | photosystem II |

| PSI | photosystem I |

| Rubisco | Ribulose Bisphosphate Carboxylase/ oxygenase |

| ABI4 | absciscic acid insensitive 4 |

| GrD | gramicidin D |

References

- Fabre, N.; Reiter, I.M.; Becuwe-Linka, N.; Genty, B.; Rumeau, D. Characterization and Expression Analysis of Genes Encoding ? And ? Carbonic Anhydrases in Arabidopsis. Plant, Cell & Environment 2007, 30, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMario, R.J.; Quebedeaux, J.C.; Longstreth, D.J.; Dassanayake, M.; Hartman, M.M.; Moroney, J.V. The Cytoplasmic Carbonic Anhydrases β CA2 and β CA4 Are Required for Optimal Plant Growth at Low CO2. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarejo, A.; Burén, S.; Larsson, S.; Déjardin, A.; Monné, M.; Rudhe, C.; Karlsson, J.; Jansson, S.; Lerouge, P.; Rolland, N.; et al. Evidence for a Protein Transported through the Secretory Pathway En Route to the Higher Plant Chloroplast. Nature Cell Biology 2005, 7, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatova, L.; Zhurikova, E.; Ivanov, B. The Presence of the Low Molecular Mass Carbonic Anhydrase in Photosystem II of C3 Higher Plants. Journal of Plant Physiology 2019, 232, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorchuk, T.P.; Kireeva, I.A.; Opanasenko, V.K.; Terentyev, V.V.; Rudenko, N.N.; Borisova-Mubarakshina, M.M.; Ivanov, B.N. Alpha Carbonic Anhydrase 5 Mediates Stimulation of ATP Synthesis by Bicarbonate in Isolated Arabidopsis Thylakoids. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudenko, N.N.; Ignatova, L.K.; Ivanov, B.N. Multiple Sources of Carbonic Anhydrase Activity in Pea Thylakoids: Soluble and Membrane-Bound Forms. Photosynthesis Research 2007, 91, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorchuk, T.; Rudenko, N.; Ignatova, L.; Ivanov, B. The Presence of Soluble Carbonic Anhydrase in the Thylakoid Lumen of Chloroplasts from Arabidopsis Leaves. Journal of Plant Physiology 2014, 171, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, N.N.; Ivanov, B.N. Unsolved Problems of Carbonic Anhydrases Functioning in Photosynthetic Cells of Higher C3 Plants. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2021, 86, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, N.N.; Vetoshkina, D.V.; Fedorchuk, T.P.; Ivanov, B.N. Effect of Light Intensity under Different Photoperiods on Expression Level of Carbonic Anhydrase Genes of the α- and β-Families in Arabidopsis Thaliana Leaves. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2017, 82, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Duan, W.; Xue, B.; Cong, X.; Sun, P.; Hou, X.; Liang, Y.-K. OsαCA1 Affects Photosynthesis, Yield Potential, and Water Use Efficiency in Rice. IJMS 2023, 24, 5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, T.; Zhang, B.; Duanmu, D. Molecular Characterization of Carbonic Anhydrase Genes in Lotus Japonicus and Their Potential Roles in Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation. IJMS 2021, 22, 7766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasooriya, H.N.; Longstreth, D.J.; DiMario, R.J.; Rosati, V.C.; Cassel, B.A.; Moroney, J.V. Carbonic Anhydrases in the Cell Wall and Plasma Membrane of Arabidopsis Thaliana Are Required for Optimal Plant Growth on Low CO2. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1267046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhurikova, E.M.; Ignatova, L.K.; Rudenko, N.N.; Mudrik, V.A.; Vetoshkina, D.V.; Ivanov, B.N. Participation of Two Carbonic Anhydrases of the Alpha Family in Photosynthetic Reactions in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2016, 81, 1182–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeeva, E.M.; Ignatova, L.K.; Rudenko, N.N.; Vetoshkina, D.V.; Naydov, I.A.; Kozuleva, M.A.; Ivanov, B.N. Features of Photosynthesis in Arabidopsis Thaliana Plants with Knocked Out Gene of Alpha Carbonic Anhydrase 2. Plants 2023, 12, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.F. [No Title Found]. Photosynthesis Research 2002, 73, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoubas, J.M.; Lomas, M.; LaRoche, J.; Falkowski, P.G. Light Intensity Regulation of Cab Gene Transcription Is Signaled by the Redox State of the Plastoquinone Pool. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995, 92, 10237–10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova-Mubarakshina, M.M.; Vetoshkina, D.V.; Naydov, I.A.; Rudenko, N.N.; Zhurikova, E.M.; Balashov, N.V.; Ignatova, L.K.; Fedorchuk, T.P.; Ivanov, B.N. Regulation of the Size of Photosystem II Light Harvesting Antenna Represents a Universal Mechanism of Higher Plant Acclimation to Stress Conditions. Functional Plant Biol. 2020, 47, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mubarakshina, M.; Khorobrykh, S.; Ivanov, B. Oxygen Reduction in Chloroplast Thylakoids Results in Production of Hydrogen Peroxide inside the Membrane. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 2006, 1757, 1496–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Borisova-Mubarakshina, M.; A. Naydov, I.; V. Vetoshkina, D.; A. Kozuleva, M.; V. Vilyanen, D.; N. Rudenko, N.; N. Ivanov, B. M. Borisova-Mubarakshina, M.; A. Naydov, I.; V. Vetoshkina, D.; A. Kozuleva, M.; V. Vilyanen, D.; N. Rudenko, N.; N. Ivanov, B. Photosynthetic Antenna Size Regulation as an Essential Mechanism of Higher Plants Acclimation to Biotic and Abiotic Factors: The Role of the Chloroplast Plastoquinone Pool and Hydrogen Peroxide. In Vegetation Index and Dynamics; Cano Carmona, E., Cano Ortiz, A., Quinto Canas, R., Maria Musarella, C., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2022 ISBN 978-1-83969-385-4.

- Sun, X.; Feng, P.; Xu, X.; Guo, H.; Ma, J.; Chi, W.; Lin, R.; Lu, C.; Zhang, L. A Chloroplast Envelope-Bound PHD Transcription Factor Mediates Chloroplast Signals to the Nucleus. Nat Commun 2011, 2, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-W.; Zhang, G.-C.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, D.-W.; Yuan, S. The Roles of Tetrapyrroles in Plastid Retrograde Signaling and Tolerance to Environmental Stresses. Planta 2015, 242, 1263–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurina, N.P.; Odintsova, M.S. Chloroplast Retrograde Signaling System. Russ J Plant Physiol 2019, 66, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, C.M.; Harmacek, L.D.; Yuan, L.H.; Wopereis, J.L.M.; Chubb, R.; Turini, P. Loss of Chloroplast Protease SPPA Function Alters High Light Acclimation Processes in Arabidopsis Thaliana L. (Heynh.). Journal of Experimental Botany 2009, 60, 1715–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, Z. Plastid Intramembrane Proteolysis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 2015, 1847, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindahl, M.; Yang, D.; Andersson, B. Regulatory Proteolysis of the Major Light-Harvesting Chlorophyll a/b Protein of Photosystem II by a Light-Induced Membrane-Associated Enzymic System. European Journal of Biochemistry 1995, 231, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, S.; Campoli, C.; Zorzan, S.; Fantoni, L.I.; Crosatti, C.; Drepper, F.; Haehnel, W.; Cattivelli, L.; Morosinotto, T.; Bassi, R. Photosynthetic Antenna Size in Higher Plants Is Controlled by the Plastoquinone Redox State at the Post-Transcriptional Rather than Transcriptional Level. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007, 282, 29457–29469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballottari, M.; Dall’Osto, L.; Morosinotto, T.; Bassi, R. Contrasting Behavior of Higher Plant Photosystem I and II Antenna Systems during Acclimation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007, 282, 8947–8958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirbet, A. ; Govindjee On the Relation between the Kautsky Effect (Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Induction) and Photosystem II: Basics and Applications of the OJIP Fluorescence Transient. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2011, 104, 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova-Mubarakshina, M.M.; Ivanov, B.N.; Vetoshkina, D.V.; Lubimov, V.Y.; Fedorchuk, T.P.; Naydov, I.A.; Kozuleva, M.A.; Rudenko, N.N.; Dall’Osto, L.; Cazzaniga, S.; et al. Long-Term Acclimatory Response to Excess Excitation Energy: Evidence for a Role of Hydrogen Peroxide in the Regulation of Photosystem II Antenna Size. EXBOTJ 2015, 66, 7151–7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova-Mubarakshina, M.M.; Vetoshkina, D.V.; Rudenko, N.N.; Shirshikova, G.N.; Fedorchuk, T.P.; Naydov, I.A.; Ivanov, B.N. The Size of the Light-Harvesting Antenna of Higher Plant Photosystem Ii Is Regulated by Illumination Intensity through Transcription of Antenna Protein Genes. Biochemistry Moscow 2014, 79, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Redox Regulation in Photosynthetic Organisms: Signaling, Acclimation, and Practical Implications. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2009, 11, 861–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biver, S.; Portetelle, D.; Vandenbol, M. Characterization of a New Oxidant-Stable Serine Protease Isolated by Functional Metagenomics. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmijewski, J.W.; Banerjee, S.; Bae, H.; Friggeri, A.; Lazarowski, E.R.; Abraham, E. Exposure to Hydrogen Peroxide Induces Oxidation and Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 33154–33164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minagawa, J. Dynamic Reorganization of Photosynthetic Supercomplexes during Environmental Acclimation of Photosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, M.T.G.; Da Luz, A.C.; Dos Santos, M.R.; Do Carmo Pimentel Batitucci, M.; Silva, D.M.; Falqueto, A.R. Drought Tolerance of Passion Fruit Plants Assessed by the OJIP Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Transient. Scientia Horticulturae 2012, 142, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrar, H.; Hussain, T.; Hadi, S.M.S.; Gul, B.; Nielsen, B.L.; Khan, M.A. Salinity Induced Changes in Light Harvesting and Carbon Assimilating Complexes of Desmostachya Bipinnata (L.) Staph. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2017, 135, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. [34] Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Pigments of Photosynthetic Biomembranes. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 1987; Vol. 148, pp. 350–382 ISBN 978-0-12-182048-0.

- Casazza, A.P.; Tarantino, D.; Soave, C. Preparation and Functional Characterization of Thylakoids from Arabidopsis Thaliana. Photosynthesis Research 2001, 68, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plants | Pigment Content (mg/g Fresh Weight) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chl a | Chl b | Chl a/Chl b | Carotenoids | |

| WT | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 2.45 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

| α-CA2-KO (9-11) | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 0.41 ± 0.04* | 2.12± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.02 |

| α-CA2-KO (8-3) | 0.89 ± 0.07 | 0.38 ± 0.02* | 2.34 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.02 |

| Genes | Nucleotide Sequences of Primers | |

|---|---|---|

| At1g73990Arabidopsis Serin Protease (SPPA) gene) | F | TCATTCTCGTGGTCTAATAGATGCTGTC |

| R | CGT CGA GCA GTC CTT TTA ATG TTC TG | |

| At2g32480 (Arabidopsis Serin Protease (ASP) gene) | F | TGTGGGAAGGGAGTTTATGGGG |

| R | GCTGCGAATTGGTAAAGCCC | |

| At5g35210 (Arabidopsis PTM gene) | F | TGA AAAGGGTCTGAGATATTCATATAA GAGATCA |

| R | GAGCACTCTGAGTCCAAGCAT | |

| At2g40220 (Arabidopsis ABI4 gene) | F | GTTGGAGATGGATCTTCGACCATTT |

| R | TTG ACC GAC CTT AGG GAT GCT | |

| At1g29930(Arabidopsis Lhcb1 gene) | F | AGCTCAAGAACGGAAGATTGG |

| R | GCCAAATGGTCAGCAAGGTT | |

| At2g05070(Arabidopsis Lhcb2 gene) | F | GTCCATACCAGATGCTTTGGGGAG |

| R | CTCACACTCTCTCTTCAATCCTTTCCTTTCAT | |

| At5g25760 (Arabidopsis Ubiquitin gene) | F | TGCTTGGAGTCCTGCTTGGA |

| R | TGTGCCATTGAATTGAACCCTCT | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).