1. Introduction

Spearmint (

Mentha spicata), fennel (

Foeniculum vulgare) and thyme (

Thymus vulgaris) are the most common herbs used not only in folk medicine, in the kitchen and in the food industry, but the attention is increasingly being paid to them in modern pharmacy and in bio industry (e.g. products with insecticidal activity). The mentioned plants contain a number of phenolic biologically active substances e.g. diosmin, diosmetin, hesperidin, luteolin, apigenin, rosmarinic acid in spearmint [1-3], chlorogenic acid, miquelianin, 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, kaempferol-3-glucuronide, kaempferol-3-arabinoside in fennel [

4,

5] and luteolin-7-glucuronide, apigenin-7-glucuronide, rosmarinic acid, salvianolic acid derivatives in thyme [

6,

7]. The dominant terpenic substances include e.g. carvacrol, thymol, p-cymene in thyme [

8], γ-terpinene, 4-allylanisole, anethole, limonene in fennel [9-11] and limonene, 1,8-cineole, carvone, cymene in spearmint [12-15].

An overview of phenolic substances and their testing in pharmacy is provided by several reviews, e.g. on the effects of mint substances [16-18], thyme substances [

18,

19] and fennel substances [

20,

21].

Regarding the fact that the herbs homogenates with a guaranteed content of active substances find increasing application in various preparations and food supplements, e.g. sage homogenate [

22], means that the homogenates must be in some way standardized. The technology of stabilizing homogenates has not yet been sufficiently studied, especially regarding the content of health-promoting substances. The goal of our work was therefore to determine the effect of the addition of ascorbic acid on the phenolic substances content in the final mint, fennel and thyme homogenates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

Mentha spicata (spearmint), Foeniculum vulgare (fennel) and Thymus vulgaris (thyme) were grown on the grounds of the Research Institute of Plant Production in Prague and Olomouc.

2.2. Preparations of Homogenates

The aerial parts of fresh herbs material were homogenized with or without the additions of water and ascorbic acid in different ratio and the final pH value of the mixture was measured. The experimental setup and pH value are given in

Table 1.

Fresh herbs were collected, and a small part was spread on sieves and let them dry for determination of dry matter and then placed in a cold room. Subsequently, homogenization of fresh herbs material was tested and performed using a Coupe R 301 mixer after the optimal addition of water was found to prepare final fine homogenate (it was different for each of the above herbs). Some samples were acidified with ascorbic acid to a pH of about 4, i.e. the addition of ascorbic acid (AA) was determined for each herb.

2.3. Microbial Analysis

Common cultivation method for microbial stability of homogenates was used. Plate count agar (Himedia, India) was used for total count of microorganisms and Yeast Glucose Chloramphenicol (YGC) Agar (Sigma-Aldrich, Czech Republic) was used for yeast and mold cultivation. Samples were cultivated at 30 °C and colony forming units (CFU) were enumerated.

2.4. High Pressure Processing

Samples given in

Table 1 represent homogenates that were filled into PET/Al/PE containers, which were vacuum sealed and then treated with a high pressure of 500 MPa for 10 minutes, then cooled to 15 °C and stored in refrigerator between 5 and 8 °C. The pressurizing was performed by a high-pressure press CYX 6/0103 (ŽĎAS a. S., Czech Republic). High pressure treatment was used as an antimicrobial intervention replacing pasteurization. Pressurized homogenates are stabile at least two years for food applications.

2.5. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Homogenate

The phenolic compounds were extracted from homogenates by methanol. 0.25 g of homogenate was extracted by 3 ml of 100% methanol and the extraction was carried out at 50 °C for 1 hour. After centrifugation, the sediment was washed twice with 1 ml of methanol. Supernatants were combined and the volume was subtracted. Each sample was prepared in triplicate and stored at -18 °C. The extracts were analysed using HPLC and LC/MS.

2.6. Extraction of Terpenes from Homogenates

Samples of plant material homogenates (thyme, fennel, mint) were prepared identically in the following manner. Approximately 0.3 g of homogenate was weighed in triplicates from each sample (double the amount for water-diluted homogenates). The weighed amount was extracted 3 times with 2 ml of hexane. After the first addition of hexane, the mixture was shaken for 1 h, the hexane was then collected in a separate vial. 2 ml of hexane were added again to the homogenate. This mixture was shaken for 0.5 h and then hexane was added to the first portion of hexane. Finally, 2 ml of hexane were added again and shaken for 0.5 h. The last portion of hexane was also added to the previous two. The hexane solution thus obtained was directly injected into the GC/MS. The hexane extract obtained from mint homogenates was diluted five times before measurement due to its high concentration.

2.7. Determination of Phenolic Compounds

Quantification of phenolic compounds by HPLC: The samples were analysed using an HPLC apparatus (Hewlett Packard 1050) (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) with a diode array detector (DAD Agilent G1315B, USA) and column Phenomenex Luna C18(2) (3 µm, 2 × 150 mm) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA).

Mobile phase A: 5% acetonitrile + 0.1% o-phosphoric acid, mobile phase B: 80% acetonitrile + 0.1% o-phosphoric acid. Gradient for separation of fennel (35 °C): 9 % to 33 % of B during 35 min, 33 % to 45 % of B during 1 min, 45 % to 80 % of B during 2 min, 80 % to 100 % of B during 2 min. Gradient for separation of spearmint (25 °C): 2 % to 42 % of B during 40 min, 40 % to 80 % of B during 2 min, 80 % of B during 3 min. Gradient for thyme (35 °C): 0 % to 45 % of B during 55 min, 45 % to 80 % of B during 5 min. The volume of the injected sample was 5 µl. Flow rate was 0.25 ml/min.

Standards (diosmin, diosmetin, hesperidin, rosmarinic acid, luteolin, apigenin, chlorogenic acid, miquelianin, 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, luteolin-7-glucuronide) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Praha, Czech Republic; methanol and acetonitrile from Merck, Praha, Czech Republic, o-phosphoric acid from Fluka, formic acid from Sigma-Aldrich, Praha, Czech Republic.

Identification of phenolic compounds was performed by LC/MS. For compounds identification we used APCI-LC/MS in positive and negative mode. (LCQ Accela Fleet, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with the same column and gradients as in HPLC, but mobile phases were acidified by formic acid.

2.8. Determination of Volatile Terpenes

Terpenes from homogenates extracts were analysed on a Trace GC Ultra gas chromatograph (Thermo Fischer Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) equipped with a Restek fused silica capillary column, Rxi-5 ms, 30 m x 0.25 mm I.D. x 0.25 µm (Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA, USA), liner SKY, Splitless, 3 mm x 0.8 mm x 105 mm (Restek Corporation,) and coupled to a mass selective detector ISQ (Thermo Fischer Scientific) working at 70 eV of ionization energy. Helium was used as a carrier gas at 1.0 mL/min with injection of 1 µL in splitless mode at 250 °C. Split flow after 1 min was 50 mL/min. The oven temperature was programmed as follows: 40 ˚C for 5 min, then increase to 150 ˚C at a rate of 3˚C/min, further increase to 250 ˚C at 10˚C/min and finally increase to 290 ˚C at a rate of 25 ˚C/min, this temperature was then held for 2 min. Transfer line temperature was 250 ˚C, ion source temperature was set to 200 ˚C. Mass scanning was started at 7.00 min, masses were scanned in the full range 50-450 m/z.

2.9. Statistics

A Two-Way ANOVA [

23] was conducted to determine to what extent H

2O and ascorbic acid have an influence on contents of specific compounds.

3. Results and Discussion

Plant homogenates were prepared as shown in Materials and methods in

Table 1.

Microbial stability of homogenates with water and ascorbic acid was suitable for food application during 21 days of storage (see Table 2). The number of microorganisms did not exceed 1.3 x 103 during storage in laboratory temperature. Yeast and mold were not detected in all samples during storage period. Microbial stability of homogenates with ascorbic acid can be supported by pH lower than 4.5 and antimicrobial impact of phytochemical components.

Table 2.

The microbial stability of homogenates prepared with water and ascorbic acid.

Table 2.

The microbial stability of homogenates prepared with water and ascorbic acid.

| Sample |

Time of storage

(day) |

Total count

(CFU/g)

at 5 °C |

Total count

(CFU/g)

at 20 °C |

| M-1 |

0 |

1.1 x 103

|

1.1 x 103

|

| 7 |

1.3 x 103

|

1.1 x 103

|

14

21 |

1.1 x 103

9.1 x 102

|

1.1 x 103

9.3 x 102

|

| F-1 |

0 |

8.2 x 101

|

8.2 x 101

|

| 7 |

7.7 x 102

|

8.0 x 102

|

| 14 |

3.7 x 102

|

3.3 x 102

|

| 21 |

5.0 x 102

|

1.7 x 102

|

| T-1 |

0 |

6.1 x 101

|

6.1 x 101

|

7

14

21 |

3.8 x 102

2.3 x 102

2.5 x 102 |

1.4 x 102

1.6 x 102

1.7 x 102

|

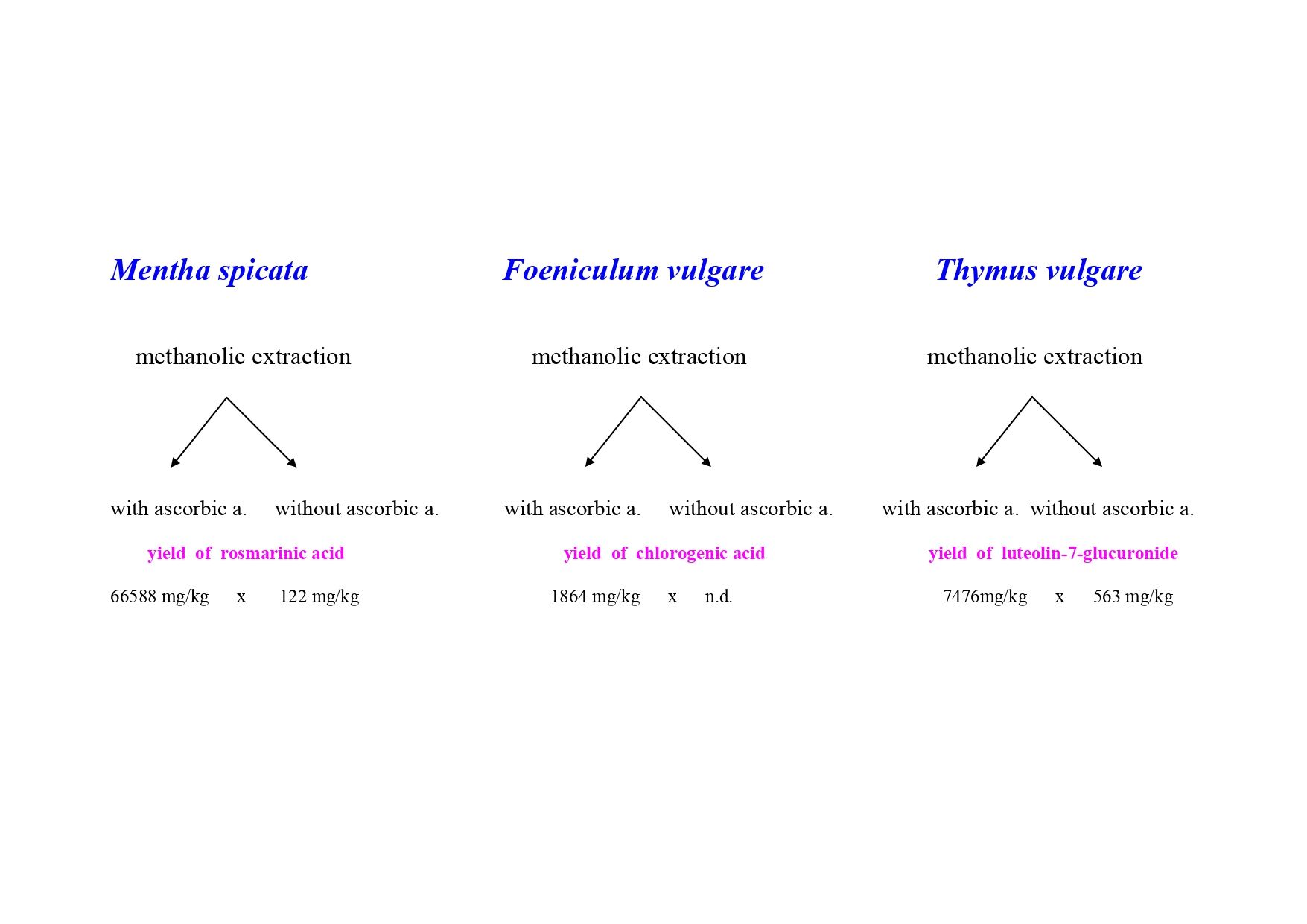

The results of analyses of the phenolic compounds of interest (Table 3) showed that the differences in the content of most substances in different homogenate preparation were considerable. The greatest effect has the addition of ascorbic acid during the homogenization process on the measured content of phenolic acids, e.g. chlorogenic acid, rosmarinic acid and their derivatives, while the measured amount of phenolic acids is minimal without addition of ascorbic acid. In thyme homogenates with ascorbic acid addition, the measured rosmarinic acid content is 37 212 mg/kg d. m., while in thyme homogenates without ascorbic acid the measured content of rosmarinic acid is only 196 mg/kg d. m. and in thyme homogenates without ascorbic acid but with water addition its content is even a little less (101 mg/kg d. m.) (Table 3). It is obvious that measured content of phenolic acids is higher in the presence of ascorbic acid, it means by lower pH value. Better stability of chlorogenic acid at low pH (pH 3) was described already in the literature [

24], but extraction is influenced also by water addition and statistically significant effect has water and ascorbic acid simultaneously. The higher content was also observed by the following flavonols glucuronides (quercetin-3-O-glucuronide (miquelianin), other quercetin derivative and kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide) and flavone glucuronides (luteolin-7-glucuronide and apigenin-7-glucuronide). All mentioned glucuronides have the highest content in the homogenates with added ascorbic acid whether water is added or not, this is due to the greater stability of glucuronides at lower pH [

25]. Extraction of mentioned flavonols is also influenced by water addition, ascorbic acid presence and their combination. Only for quercetin derivative in

Foeniculum vulgare does not show a statistically significant difference for the combined use of water and ascorbic acid. Kaempferol-arabinoside also shows greater availability in the presence of ascorbic acid and water.

Regarding flavan hesperidine, its content is highest in homogenates with ascorbic acid addition but without the addition of water. Combination of other conditions also influences the yield of extraction. The other flavones (luteolin, diosmin, diosmetin) are influenced with water and ascorbic acid presence in homogenate, and with their combination. Apigenin behaves rather differently, there is not so clear dependence on the presence of ascorbic acid, but from statistical point of view only water addition has significant effect (

Table 3). In the opposite, the highest content of diosmetin was found in all homogenates without ascorbic acid addition. The content of diosmin is the highest in homogenate with water addition, but without ascorbic acid addition; in water-free homogenates with or without ascorbic acid addition the content of diosmin is lower. In this context is clear that herb homogenates preparation and their analysis are very important steps, as our results show. The greatest changes are in the rosmarinic acid content. Pure rosmarinic acid is a stable substance and its solution in ethanol is also stable at different temperatures (10 °C - 40 °C) and under different light exposure as experimentally found [

26].

Table 2.

The content of monitored phenolic compounds (mg/kg dry matter).

Table 2.

The content of monitored phenolic compounds (mg/kg dry matter).

Mentha

spicata

|

Water

|

Ascorbic

acid

|

Diosmin

|

Hesperidin

|

Rosmarinic

acid

|

Luteolin

|

Apigenin

|

Diosmetin

|

| M-1 |

water |

ascorbic acid |

18573 ± 571 abc

|

1281 ± 106 abc

|

33271 ± 2013 abc

|

1000 ± 25 abc

|

599 ± 9 a

|

720 ± 26 abc

|

| M-2 |

water |

0 |

22364 ± 1039 abc

|

1201 ± 66 abc

|

95 ± 4 abc

|

652 ± 29 abc

|

571 ± 60 a

|

1888 ± 143 abc

|

| M-3 |

0 |

0 |

12826 ± 524abc

|

893 ± 46abc

|

122 ± 27abc

|

485 ± 26 abc

|

485 ± 17 a

|

922 ± 111 abc

|

| M-4 |

0 |

ascorbic acid |

13862 ± 842 abc

|

2471 ± 144 abc

|

66588 ± 2393 abc

|

495 ± 31 abc

|

495 ± 46 a |

309 ± 44 abc

|

| Foeniculum |

Water |

Ascorbic |

Chlorogenic |

Miquelianin |

Quercetin |

1,5-dicaffeoylquinic |

Kaempferol- |

Kaempferol- |

| vulgare |

|

acid |

acid |

|

derivative |

acid |

3-O-glucuronide |

3-O-arabinoside |

| F-1 |

water |

ascorbic acid |

2021 ± 40 abc

|

2416 ± 66 abc

|

853 ± 28 ab |

617 ± 10 abc

|

1098 ± 35 abc

|

664 ± 28 abc

|

| F-2 |

water |

0 |

n.d. |

555 ± 41 abc

|

309 ± 16 ab

|

81 ± 18 abc

|

481 ± 17 abc

|

420 ± 15 abc

|

| F-3 |

0 |

0 |

n.d. |

527 ± 38 abc

|

372 ± 28 ab

|

n.d. |

495 ± 26 abc

|

443 ± 17 abc

|

| F-4 |

0 |

ascorbic acid |

1864 ± 46 abc

|

1933 ± 55 abc

|

889 ± 23 ab

|

716 ± 38 abc

|

798 ± 19 abc

|

579 ± 17 abc

|

| Thymus |

Water |

Ascorbic |

Luteolin- |

Apigenin |

Rosmarinic |

Rosmarinic acid |

Rosmarinic acid |

Caffeoyl- |

| vulgaris |

|

acid |

7-glucuronide |

7-glucuronide |

acid |

derivative 1 |

derivative 2 |

rosmarinic acid |

| T-1 |

water |

ascorbic acid |

8734 ± 84 abc

|

3011 ± 89 abc

|

33145 ± 255 abc

|

3779 ± 174 b

|

4611 ± 97 abc

|

2775 ± 44 abc

|

| T-2 |

water |

0 |

954 ± 81 abc

|

2550 ± 280 abc

|

196 ± 63 abc

|

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

| T-3 |

0 |

0 |

563 ± 3 abc

|

1476 ± 32 abc

|

101 ± 8 abc

|

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

| T-4 |

0 |

ascorbic acid |

7476 ± 39 abc

|

2608 ± 90 abc

|

37212 ± abc b

|

3737 ± 212 b

|

4098 ± 127 abc

|

3061 ± 145 abc

|

Table 3.

The content of monitored terpenes (% of peaks from normalized peak area).

Table 3.

The content of monitored terpenes (% of peaks from normalized peak area).

| Mentha spicata |

Water |

Ascorbic acid |

β-Pinene |

Myrcene |

Limonene |

Eucalyptol |

trans-Caryophyllene |

Piperitenoneoxide |

|

| M-1 |

water |

ascorbic acid |

0.367 ± 0.012 ac

|

1.457 ± 0.026 abc

|

2.980 ± 0.128 ab

|

6.007 ± 0.118 b

|

1.720 ± 0.028 ac

|

81.890 ± 0.168 ac

|

|

| M-2 |

water |

0 |

0.350 ± 0.008 ac

|

1.140 ± 0.041 abc

|

2.583 ± 0.078 ab

|

5.563 ± 0.181 b

|

1.537 ± 0.024 ac

|

82.500 ± 0.268 ac

|

|

| M-3 |

0 |

0 |

0.337 ± 0.017 ac

|

1.090 ± 0.029 abc

|

2.517 ± 0.168 ab

|

5.443 ± 0.076 b

|

1.883 ± 0.125 ac

|

83.010 ± 0.403 ac

|

|

| M-4 |

0 |

ascorbic acid |

0.313 ± 0.005 ac

|

1.170 ± 0.037 abc

|

2.623 ± 0.063 ab

|

6.007 ± 0.046 b

|

1.800 ± 0.033 ac |

83.303 ± 0.172 ac

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Foeniculum vulgare |

Water |

Ascorbic acid |

α-Pinene |

Phelandrene |

4-Cymene |

Limonene |

Fenchone |

Estragole |

trans-Anethole |

| F-1 |

water |

ascorbic acid |

0.257 ± 0.012 abc

|

0.817 ± 0.024 ac

|

0.110 ± 0.008 bc

|

0.110 ± 0.008 ab

|

0.750 ± 0.024 ab

|

0.223 ± 0.005 abc

|

97.650 ± 0.029 abc

|

| F-2 |

water |

0 |

0.480 ± 0.054 abc

|

0.877 ± 0.052 ac

|

0.780 ± 0.078 bc

|

0.173 ± 0.017 ab

|

1.323 ± 0.068 ab

|

0.383 ± 0.009 abc

|

95.863 ± 0.130 abc

|

| F-3 |

0 |

0 |

0.717 ± 0.005 abc

|

1.153 ± 0.005 ac

|

0.570 ± 0.008 bc

|

0.217 ± 0.005 ab

|

1.160 ± 0.033 ab

|

0.260 ± 0.014 abc

|

95.800 ± 0.059 abc

|

| F-4 |

0 |

ascorbic acid |

0.650 ± 0.008 abc

|

1.295 ± 0.004 ac

|

0.210 ± 0.008 bc

|

0.160 ± 0.000 ab

|

0.775 ± 0.029 ab |

0.250 ± 0.024 abc

|

96.595 ± 0.061 abc

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Thymus vulgaris |

Water |

Ascorbic acid |

4-Cymene |

γ-Terpinene |

Linalool |

Borneol |

Terpinen-4-ol |

Thymol |

Carvacrol |

| T-1 |

water |

ascorbic acid |

0.593 ± 0.056 ab

|

1.510 ± 0.104 abc

|

0.090 ± 0.000 a

|

0.100 ± 0.000 a

|

0.200 ± 0.000 abc

|

92.663 ± 0.081 ac

|

2.750 ± 0.273 abc

|

| T-2 |

water |

0 |

2.733 ± 0.070 ab

|

0.257 ± 0.012 abc

|

0.100 ± 0.000 a

|

0.120 ± 0.008 a

|

0.027 ± 0.005 abc

|

91.180 ± 0.204 ac

|

2.510 ± 0.070 abc

|

| T-3 |

0 |

0 |

3.300 ± 0.062ab

|

0.377 ± 0.031 abc

|

0.177 ± 0.046 a

|

0.230 ± 0.043 a

|

0.057 ± 0.017 abc

|

88.897 ± 0.893 ac

|

2.760 ± 0.228 abc

|

| T-4 |

0 |

ascorbic acid |

1.147 ± 0.021 ab

|

2.243 ± 0.108 abc

|

0.207 ± 0.029 a

|

0.220 ± 0.033 a

|

0.313 ± 0.025 abc |

86.267 ± 1.319 ac

|

3.967 ± 0.180 abc

|

Rosmarinic acid content in

Melissa officinalis tinctures prepared from dry plant material was higher (2.96 - 22.18 mg/ml) than in the tinctures prepared from fresh ground-crushed material (less than 0.92 mg/ml) [

27]. Olah et al. [

28] found higher rosmarinic acid content in fresh

Rosmarinus officinalis tinctures (0.35 mg/ml) than in the tinctures prepared from dried material (0.18 mg/ml), but it should be noted that the above-mentioned authors did not cut or crush fresh material and thus the enzymatic activity was not increasing. Six et al. [

29] found that the amount of rosmarinic acid in a 50% ethanolic extract from the dried material of various Laminaceae decreases after 24 weeks by 14-27 %, even by 41 % in sage. Bodalska et al. [

30] tested the stability of rosmarinic acid in commercial herbal medicinal products and found that in aqueous tinctures is rosmarinic acid very unstable, stability is much better in water-ethanolic extracts. A very important step influencing the final content of the compounds of acidic nature is whether we will grind the samples or leave the whole fresh plant material intact. In the fresh plant homogenates, the released enzymes act on chlorogenic and rosmarinic acids and their derivatives, and these compounds are therefore the subject of rapid degradation. The presence of ascorbic acid has at least dual positive effects on the content of the compounds, first, ascorbic acid decreases pH and low pH blocks enzymatic activity and second, ascorbic acid suppresses ionization of acidic compounds in water, therefore they reveal higher yield during extraction step. The content of rosmarinic acid in homogenates from

Mentha spicata and

Thymus vulgaris was influenced not only by ascorbic acid addition, but also with water addition. The combination of these two additions has also a statistically significant effect. In both homogenates, without ascorbic acid addition was rosmarinic acid content very low, and the same was observed also for the rosmarinic acid derivatives 1 and 2. For extraction of rosmarinic acid and their derivatives is also important the presence of water, only rosmarinic acid derivative 1 was not influenced by water addition.

In acidic media, terpenes generally undergo various transformations. The complex mixtures of products obtained in these transformations are the major factors that hinder the proper interpretation of the analytical results especially because EOs themselves are a very complex matrix and, in addition, these processes can also be influenced by the phenolic substances present, as is the case, for example, with γ-terpinene. In the case of γ-terpinene we can see the largest changes in the homogenate from Thymus vulgaris in Tab. 3. In the presence of ascorbic acid and water, the amount of γ-terpinene increases from 0.377 to 1.510 (measured by the relative peak area – here and further in the discussion). The opposite is true for 4-cymene, the content decreased in this homogenate from 3.3 to 0.593, as well as in Foeniculum vulgare homogenate from 0.570 to 0.110. In this homogenate, the largest decrease in α-pinene was also observed, from 0.717 to 0.257. In contrast, this decrease in β-pinene content was not observed in the acidic environment in Mentha spicata homogenate.

It is clear from the literature that most plant enzymes are highly resistant to pressure-induced inactivation, with partial inactivation at most under commercially feasible HPP conditions. In general, enzymes are more resistant to inactivation than vegetative microorganisms, posing a challenge to the application of HPP for stabilization of fruit and vegetable products.

By using herbs homogenates as a food additive, a complex of substances having the same synergistic effect and the same biological effects as the original herb is introduced into the food, which is not ensured by adding only one major substance obtained from the herb by extraction. This was verified in the hops homogenate, where the complete homogenate had higher antimicrobial activity than individual alpha and beta bitter acids acting alone [

31]. It is quite clear that plant extracts and herbs homogenates in this case have shown a considerable promise in a range of applications in the food industry which also results from the published literature, e.g. [

32].

4. Conclusions

The differences in the content of most polyphenolic compounds in different homogenate preparation were considerable. The greatest effect has the addition of ascorbic acid during the homogenization process on the content of phenolic acids, e.g. rosmarinic acid and chlorogenic acid, e.g. in thyme homogenates the rosmarinic acid content was almost 200 x higher compared to thyme homogenates without ascorbic acid. The content of flavonols glucuronides (quercetin-3-O-glucuronide, kaempferol-3-O-glucuronide) and flavone glucuronides (luteolin-7-glucuronide and apigenin-7-glucuronide) was also the highest in the presence of ascorbic acid. Flavones luteolin, apigenin, diosmin and diosmetin behave rather differently, there is not so clear dependence on the presence of ascorbic acid. From our experiments and from the literature we can conclude that for the preservation of phenolic acids, flavonols and flavone glucuronides in the fresh herbs homogenates it is very important to add ascorbic acid which will block enzymatic activity which prevents rapid degradation of the compounds and suppress ionization of acidic compounds in water, therefore compounds of acidic nature reveal higher yield during extraction step. The obtained results also show that in order to achieve the necessary accuracy in the analysis of natural substances containing phenolic compounds and terpenes, increased attention must be paid to setting and maintaining the optimal pH value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T. and N.V.; methodology, N.V.; validation and statistics, N.V., E.K. and P.N.; formal analysis, J.T.; high pressure treatment, J.S.; resources, J.T. and N.V.; data curation, N.V.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T.; writing—review and editing, M.H.; analyses of terpenes and data curation, J.B.; supervision, R.P.; project administration, R.P.; funding acquisition, R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research was funded by Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic (Medicinal plants in the food industry - a new direction for the prevention of civilization diseases, Project No. QL24010019), by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (AdAgriF; CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004635) and by Metrofood-CZ (Grant No: LM2023064).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study can be made available by the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gökbulut, A.; Şarer, E. Simultaneous Determination of Phenolic Compounds in Mentha Spicata L. Subsp. Spicata by RP-HPLC. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 7, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bimakr, M.; Rahman, L.A.; Taip, F.S.; Ganjloo, A.; Salleh, L.M.; Selamat, J.; Hamid, A.; Zaidul, I.S.M. Comparison of different extraction methods for the extraction of major bioactive flavonoid compounds from spearmint (Mentha spicata L.) leaves. Food Bioprod. Process. 2011, 89, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, I.; Hadjmohammadi, M.R.; Peyrovi, M.; Iranshahi, M.; Barfi, B.; Babaei, A. B.; Dust, A.M. HPLC determination of hesperidin, diosmin and eriocitrin in Iranian lime juice using polyamide as an adsorbent for solid phase extraction. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2011, 56, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Križman, M.; Baričevič, D.; Prošek, M. Determination of phenolic compounds in fennel by HPLC and HPLC–MS using a monolithic reversed-phase column. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2007, 43, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roby, M.H.H.; Sarhan, M.A.; Selim, K. A-H.; Khalel, I.K. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oil and extracts of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) and chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 44, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, T. O.; Solar, S.; Sontag, G.; Koenig, J. Identification of phenolic components in dried spices and influence of irradiation. Food Chem. 2011, 128, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roby, M.H.H.; Sarhan, M.A.; Selim, K. A-H.; Khalel, I.K. Evaluation of antioxidant activity, total phenols and phenolic compounds in thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.), sage (Salvia officinalis L.), and marjoram (Origanum majorana L.) extracts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 43, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela, R.; Sedlák, P. Post-application temperature as a factor influencing the insecticidal activity of essential oil from Thymus vulgaris. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 113, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeh, A.; Allaf, A.W. Determination of polyphenol component fractions and integral antioxidant capacity of Syrian aniseed and fennel seed extracts using GC–MS, HPLC analysis, and photochemiluminescence assay. Chem. Pap. 2017, 71, 1731–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, D.; Saxena, S.N.; Sharma, L.K.; Lal, G. Prevalence of Essential and Fatty Oil Constituents in Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill) Genotypes Grown in Semi-Arid Regions of India. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2018, 21, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najdoska-Bogdanov, M.; Bogdanov, J.B.; Stefova, M. Simultaneous determination of essential oil components and fatty acids in fennel using gas chromatography with a polar capillary column. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardaweel, S.K.; Bakchiche, B.; ALSalamat, H.M.; Rezzoug, M.; Gherib, A.; Flamini, G. Chemical composition, antioxidant, antimicrobial and Antiproliferative activities of essential oil of Mentha spicata L. (Lamiaceae) from Algerian Saharan atlas. BMC Complement. Alter. Med. 2018, 18, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishr, M.M.; Salama, O.M. Inter and intra GC-MS differential analysis of the essential oils of three Mentha species growing in Egypt. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 4, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, I.; Anwar, F. Effect of harvesting regions on physico-chemical and biological attributes of supercritical fluid-extracted spearmint (Mentha spicata L.) leaves essential oil. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2018, 21, 400–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Solana, R.; Salgado, J.M.; Domínguez, J. M.; Cortés-Diéguez, S. Comparison of Soxhlet, Accelerated Solvent and Supercritical Fluid Extraction Techniques for Volatile (GC–MS and GC/FID) and Phenolic Compounds (HPLC–ESI/MS/MS) from Lamiaceae Species. Phytochem. Anal. 2015, 26, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Gadewar, M.; Tahilyani, V.; Patel, D.K. A review on pharmacological and analytical aspects of diosmetin: A concise report. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2013, 19, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, G.L.; Ralston, R.A.; Schwartz, S.J. Flavones: Food Sources, Bioavailability, Metabolism, and Bioactivity. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-D.; Park, Y. S.; Jin, Y.-H.; Park, C.-S. Production and applications of rosmarinic acid and structurally related compounds. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 2083–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, S.; Kukhdan, A.J.; Hosseini, A.; Armand, R. The application of Thymus vulgaris in traditional and modern medicine: A review. Glob. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 9, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooti, W.; Moradi, M.; Ali-Akbari, S.; Sharafi-Ahvazi, N.; Asadi-Samani, M.; Ashtary-Larky, D. Therapeutic and pharmacological potential of Foeniculum vulgare Mill: a review. J. HerbMed. Pharmacol. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kushwah, P.; Patel, R.; Midda, A.; Kayande, N. Pharmacological review on Foeniculum vulgare. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. 2016, 1, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Strohalm, J.; Houška, M.; Novotná, P. A food preparation based on hydrocolloids with the addition of Mongolian milkvetch, Chinese knotweed and red sage. 2018, Utility Pattern No. 3144. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, O.J.; Clark, V.A. Applied Statistics: Analysis of Variance and Regression. NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1974.

- Friedman, M.; Jürgens, H.S. Effect of pH on the stability of plant phenolic compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 2101–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S. R. Bioanalytical challenges and strategies for accurately measuring acyl glucuronide metabolites in biological fluids. Biomed. Chromatog. 2020, 34, Article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Smuts, J.P.; Dodbiba, E.; Rangarajan, R.; Lang, J.C.; Armstrong, D.W. Degradation study of carnosic acid, carnosol, rosmarinic acid and rosemary extract (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) assessed using HPLC. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9305–9314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Medina, A.; Etheridge, C.J.; Hawkes, G.E.; Hylands, P.J.; Pendry, B.A.; Hughes, M.J.; Corcoran, O. Comparison of rosmarinic acid content in commercial tinctures produced from fresh and dried lemon balm (Melissa officinalis). J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 10, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, N.K.; Osser, G.; Campean, R.F.; Furtuna, F.R.; Benedec, D.; Filip, L.; Raita, O.; Hanganu, D. The study of polyphenolic compounds profile of some Rosmarinus officinalis L. extracts. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 29, 2355–2361. [Google Scholar]

- Sik, B.; Lakatos, E.H.; Kapcsándi, V.; Székelyhidi, R.; Ajtony, Z. Investigation of the long-term stability of various tinctures belonging to the lamiaceae family by HPLC and spectrophotometry method. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 5781–5791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodalska, A.; Kowalczyk, A.; Fecka, I. Stability of rosmarinic acid and flavonoid glycosides in liquid forms of herbal medicinal products - A preliminary study. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čermák, P.; Palečková, V.; Houška, M.; Strohalm, J.; Novotná, P.; Mikyška, A.; Jurková, M.; Sikorová, M. Inhibitory effects of fresh hops on Helicobacter pylori strains. Czech J. Food Sci. 2015, 33, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, P.S. Plant extracts for the control of bacterial growth: Efficacy, stability and safety issues for food application. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2012, 156, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Compositions and pH of the homogenates.

Table 1.

Compositions and pH of the homogenates.

| Sample |

Sample composition |

pH value |

| M-1 |

400 g M + 400 g W + 18 g AA |

4.34 |

M-2

M-3

M-4 |

400 g M + 400 g W

400 g M

400 g M + 18 g AA |

6.60

6.17

4.24 |

F-1

F-2

F-3

F-4

|

400 g F + 200 g W + 10 g AA

400 g F + 200 g W

400 g F

348 g F + 30 g W + 6 g AA

|

4.18

5.59

5.71

4.17

|

| T-1 |

400 g T + 600 g W + 24 g AA |

3.91 |

| T-2 |

200 g T + 300 g W |

6.18 |

T-3

T-4 |

400 g T

300 g T + 18 g AA |

6.20

3.91 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).