1. Introduction

Enterovirus represents a common cause of infection in the neonatal intensive care units (NICU). The route of transmission can be vertical 1, occurring before, during and after the delivery, or horizontal, involving contact with family members or health professionals.2 Seasonal variation or cluster in Enterovirus infection have been described. 3

Infection can be mildly symptomatic (up to 80% of patients 4) or severe with development of myocarditis, meningoencephalitis, hepatitis and other life-threatening conditions. 2 Maternal flu-like syndromes or diarrhea in the period from 2 months prepartum to 7 days postpartum have been reported in 30% of severe enterovirus infections. 2 However, the presence of symptoms at least 5-7 days before delivery is associated with a milder course in the neonate (due to specific maternal antibodies crossing the placenta). 3 In about 70% of cases, the age of onset of symptoms is less than 7 days of life (DOL). 2

Classic clinical symptomatology is characterized by fever or hypothermia, rash, lethargy, hyporexia, or respiratory distress. In cases of severe illness, the presence of heart failure with shock, arrhythmias or seizures may be present. 2

In a systematic review regarding severe enterovirus infection, 37.1% of the patients had myocarditis 2, of which approximately one third developed arrhythmias (30,7%) 2. Abnormalities observed in electrocardiograms may include sinus tachycardia, T wave abnormalities, ventricular tachycardia (VT), and supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). 1 ECG signs of inflammatory involvement may be present in up to 30% of cases 2. The prognosis for neonates who develop myocarditis associated with enterovirus infection is variable, ranging from a self-remitted course to the necessity for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Overall mortality for enterovirus-related myocarditis is estimated to be 38%2 %, reaching 67% in patients requiring ECMO 4.

The prevalence of neonatal arrhythmias (NAs) is reported to be between 1% and 5% in NICU 5. NAs can be classified as benign or non-benign, defined as the capacity to result in hemodynamic compromise or clinical deterioration. Regarding neonatal patients, non-benign arrhythmias (iterative SVT, AV dissociation, VT, ventricular fibrillation (VF) and long QT syndromes) have highest prevalence in extreme low birth weight individuals (ELBW) while benign NAs are more common in low birth weight (LBW) and moderate-to-late preterm neonates 5. As demonstrated by the Frank-Starling law, the limited functional reserve of the newborn heart means that any significant change in heart rate will result in a decline in cardiac output, impaired cardiac filling and venous congestion 6. This effect is more significant for premature neonates, those critically ill, or those with concomitant congenital heart disease. 5

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is one of the most common arrhythmic emergencies in newborns, occurring in approximately 1 in 250 to 1 in 1 000 live births. SVT in neonates and infants arises chiefly from reentrant circuits 7. Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT) via an accessory pathway (e.g., Wolff-Parkinson-White) is the predominant mechanism, accounting for 70–80 % of cases in infancy. Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT), due to dual slow and fast AV nodal pathways, occurs in 5–17 % of patients. A rarer but clinically important variant, permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia (PJRT), employs a slowly conducting posteroseptal accessory pathway to sustain incessant reentry and predispose to tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy 8 Far less common substrates include Mahaim fiber-mediated antidromic circuits and junctional ectopic tachycardia (JET) driven by His-bundle automaticity. Although most neonatal supraventricular tachycardias are due to congenital accessory conduction pathways, some of these arrhythmias may be acquired, for example, as a result of acute inflammatory injury in cases of myocardial involvement. Both viral and bacterial pathogens may cause such potentially dramatic complications 9,10

2. Case Report

A 27+6 GW female infant was born by urgent C-section for preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome and pathological Doppler sonography of the placental vessels. Prenatal ultrasound showed fetal growth restriction (FGR). Steroid prophylaxis with betamethasone was completed before delivery. No history of fetal arrhythmias has been reported. Birth weight was 760 grams and Apgar scores was 3, 5 and 7 at 1, 5 and 10 minutes, respectively. Umbilical arterial blood gas was normal (pH 7.19). Due to worsening respiratory distress (Silverman 4-5) and oxygen requirements (FiO2 up to 100%), the patient was intubated in the delivery room and transferred to NICU. During positive pressure ventilation (SIPPV), endotracheal surfactant therapy (Curosurf 200mg/kg) was administered on the first day of life with improvement in clinical condition. Antibiotic empiric treatment was started (Ampicillin 100mg/kg BID and Gentamicin 5mg/kg/die) and then suspended in the absence of signs of early onset sepsis.

On the third day of life, due to the persistence of mild respiratory distress, a second administration of surfactant was given (Curosurf 100mg/kg). Simultaneously, echocardiography showed an hemodynamically significative patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) with a left-to-right shunt. Medical therapy with paracetamol was started leading to complete PDA closure. On the fourth day of life, extubation was performed and nasal CPAP support was started.

The following clinical course was uneventful until the fourth week of life when, multiple apnoea episodes unresponsive to caffeine and doxapram therapies required reintubation. In clinical suspicion of late onset sepsis (LOS), empiric therapy with meropenem and vancomycin was started, and blood culture was performed (negative). CSF analysis was unreliable due to hematic contamination, and culture was negative. Repeated echocardiography showed sub-acute pericardial effusion with normal biventricular function and no associated valvular abnormalities. After 48 hours from the onset of the symptoms, sudden onset of narrow QRS tachycardia occurred (HR 240) with cessation after vagal manoeuvres. ECG was consistent for supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). No delta waves were present, so WPW was ruled out (

Figure 1).

Epicutaneo-caval catheter (ECC) location was outside the atrium and no electrolyte imbalance was identified. Slight increase of troponin I was reported (0,8ng/ml) in presence of markedly raised NT pro-BNP (19.000 pg/nl). Due to the recurrence of SVT episodes, therapy with propranolol was started. Complete blood tests showed elevation of transaminases (AST 128 U/L – ALT 117 U/L). Mild persistent c-reactive protein (CRP) elevation was noted despite antibiotic therapy (0,91 mg/dl). Considering the association between hepatic and cardiac involvement, a viral multiplex PCR screening was performed on a blood sample revealing the presence of Enterovirus RNA.

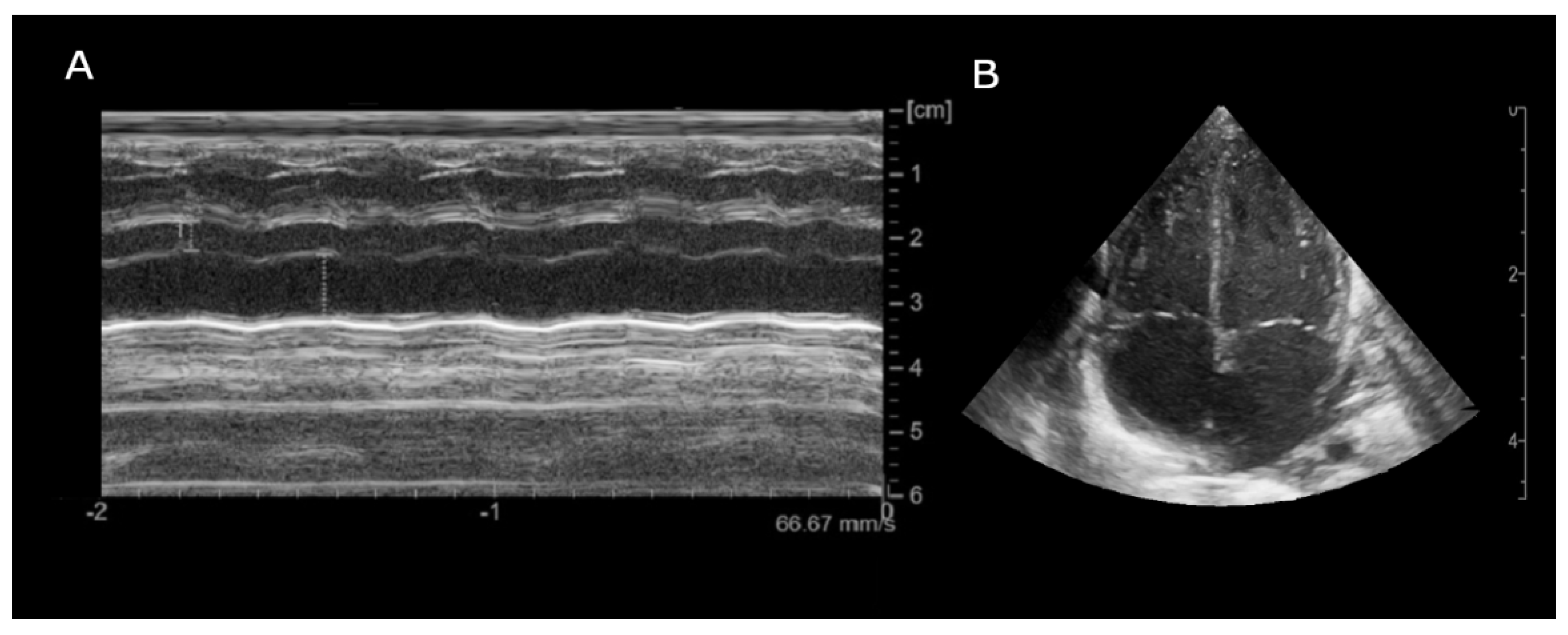

Prompt transfontanellar ultrasound showed low-grade bilateral IVH with no additional abnormalities. Brain and cardiac MRI were considered unfeasible due to unsafe clinical condition (increased SVT episodes frequency). Given the partial response to propranolol treatment, flecainide was added as second line therapy. Subsequent echocardiography showed new onset of focal hypokinesia of middle lower segment of the left ventricle, mild mitral regurgitation and enlargement of the left atrium (

Figure 2).

Given the progressive increase in the frequency of SVT episodes, a pharmacological cardioversion trial with adenosine was administered resulting in a transient response and a reset of the incessant atrial tachycardia. It was then decided to discontinue flecainide and initiate amiodarone therapy (with loading i.v. dose). Given no improvement in SVT control in 48 hours, also digoxin was started. This triple therapy resulted in a reduction of the heart rate to values compatible with gestational age (HR 140-160 bpm) however not achieving a stable sinus rhythm (

Figure 3).

Enterovirus RNA on blood was still positive at 12 weeks after onset of the symptoms. Given the absence retrieval of a sinus rhythm to digoxin and amiodarone therapy, these two drugs were discontinued at approximately three months of age.

The patient was then discharged with stable cardiac function and propranolol therapy with the exclusive aim of controlling the heart rate. Serial electrocardiographic evaluations showed persistence of junctional rhythm until 7th month of life, when, during a short hospitalization due to Influenza B virus, the appearance of atrial rhythm was identified (

Figure 4). Last echocardiography showed normal biventricular function (EF 55-60%) with enduring biatrial enlargement (

Figure 5).

One month after the patient is in good clinical conditions with serial ECG showing a stable heart rate with few atrial P-waves under propranolol prophylaxis.

4. Discussion

Cardiological involvement during enterovirus infection can lead to a severe clinical picture with the need for complex treatment. Immunohistochemical analysis (immunofluorescence assays) showed that evidence of enterovirus in cardiac tissue is much more frequent than in adult cases 11. In multiple case series with sudden infant death syndrome, enterovirus was detected from post-mortem myocardial samples. 12,13This data is apparently controversial when compared to different study. 14

Receptors expressed on the cell surface of cardiomyocytes (CAR) represent the target of certain types of enteroviruses (e.g. coxsackie B viruses). 15 Enterovirus has also showed the capability to induce cardiomyocyte apoptotic pathway by an up-regulation of Bax expression, potentially causing a progression of disease. 16 Specific enterovirus expressed proteases (2Apro and 3Cpro) appears also to be correlated with persistence of viral infection and tropism for cardiac proteins (e.g. dystrophin). 15 In adult population, Enteroviruses harbouring a 5’ terminal genomic RNA deletion tend to become chronic and have been associated with the pathogenesis of unexplained dilated cardiomyopathies. 17 These multiple mechanisms have been postulated in the development of cardiac conduction disturbances, cardiac injury and inflammation. 15,16

Historically, the diagnosis of myocarditis has been related to direct tissue examination using Dallas criteria 18. Nowadays, myocarditis diagnosis is pursued with multimodal approach using molecular technique (PCR) and functional cardiac exams (such as echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance)19. However, it is important to emphasize that the isolation of a viral agent in peripheral samples can only be regarded as an alternative to myocardial viral PCR if the latter is deemed to be unfeasible.19In our patient, given the ELBW and unstable clinical conditions, myocardial biopsy and cardiac MRI were considered unsafe and non-diagnostic.

Multiple case series have been reported regarding newborn with arrhythmia due to EV infection, summarized in

Table 1. The most frequently identified arrhythmia is supraventricular tachycardia (SVT, in addition with JT) followed by premature complexes (ventricular or atrial). Occasionally, atrial flutter and ventricular tachycardia have been reported. All the patients have been diagnosed with EV infection by analyses performed from stools, CSF or blood. No biopsies or cardiac MRI have been performed.

It should be noted that there is no specific antiarrhythmic drug preferred in patients with myocarditis 19. The latest guidelines regarding pharmacological management of arrhythmias in the neonatal period have been recently published by American Heart Association. 20 In the setting of SVT with pulse, adenosine is still considered as first line treatment in case of failure of vagal manoeuvres. Propranolol and digoxin should be considered for long-term SVT (digoxin should not be administered if there’s a suspicion for pre-excitation). 20 A multiagent drug regimen is often necessary 21. Long term therapy is recommended for a duration of approximately 6-12 months after SVT. 22

To our best knowledge, this is the first described case of EV-induced arrhythmia occurring in ELBW with FGR newborn. Given the more profound immaturity of the autonomic system and the fragility of cardiovascular regulation, the treatment must be timely and shared with paediatric cardiologists. In addition, recurrent SVT has been proposed as a risk factor necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) 23.

In EV-induced myocarditis survivors, the burden of long-term prognosis can be characterized by the development of cardiac comorbidities in up to 66% of patients (severe dysfunction of the left ventricle or mitral valve regurgitation). 24

In this light, serial echocardiography and ECG evaluations should be established in the longitudinal follow up of these patients. Educations of the caregivers in recognizing arrhythmia symptoms should also be sought.

5. Conclusions

Enterovirus infection in the neonatal period is a condition that can be life-threatening, due to the presence of a possible immature conduction system which may predispose to an increased risk of developing arrhythmias. In the case of patients with LOS that is unresponsive to therapy, virological work-up must also be considered. The management of these patients must be shared between neonatologists and paediatric cardiologists. The propensity for cardiological complications necessitates ongoing instrumental and functional evaluations during follow-up. In conclusion, investigation into the molecular mechanisms underlying the cardiac tropism of enteroviruses is crucial to identify new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M., A.C. (Alessio Conte), A.C. (Andrea Calandrino), A.P., R.F., and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M., A.C. (Alessio Conte), A.C. (Andrea Calandrino), F.V., and A.S. ; writing—review and editing, A.S., R.F., and L.A.R..; visualization, A.C. (Alessio Conte); A.C. (Andrea Calandrino); A.P.; supervision, R.F., and L.A.R..; project administration, A.C. (Andrea Calandrino), and L.A.R.; funding acquisition, A.C. (Andrea Calandrino). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by an IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini research grant [UAUT (2022_258_0)].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in compliance with the terms of the Helsinki Declaration and written informed consent for the enrolment and for the publication of individual clinical details was obtained from parents. In our country, namely Italy, this type of clinical study does not require Institutional Review Board/Institutional Ethics Committee approval to publish the results.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the subject involved in the present study.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini for the support given in several steps leading to the publication of the present study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NICU |

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| DOL |

Days of Life |

| VT |

Ventricular Tachycardia |

| SVT |

Supraventricular Tachycardia |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| ECMO |

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation |

| NAs |

Neonatal Arrhythmias |

| AV |

Atrioventricular |

| VF |

Ventricular Fibrillation |

| ELBW |

Extremely Low Birth Weight |

| LBW |

Low Birth Weight |

| AVRT |

Atrioventricular Reentrant Tachycardia |

| WPW |

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome |

| AVNRT |

Atrioventricular Nodal Reentrant Tachycardia |

| PJRT |

Permanent Junctional Reciprocating Tachycardia |

| JET |

Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia |

| GW |

Gestational Weeks |

| FGR |

Fetal Growth Restriction |

| FiO2 |

Fraction of Inspired Oxygen |

| SIPPV |

Synchronized Intermittent Positive Pressure Ventilation |

| BID |

Bis in Die |

| PDA |

Patent Ductus Arteriosus |

| CPAP |

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure |

| LOS |

Late Onset Sepsis |

| CSF |

Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| ECC |

Epicutaneo-Caval Catheter |

| NT-proBNP |

N-terminal pro b-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| AST |

Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| ALT |

Alanine Aminotransferase |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| IVH |

Intraventricular Hemorrhage |

| EF |

Ejection Fraction |

| CAR |

Coxsackievirus and Adenovirus Receptor |

| NEC |

Necrotizing Enterocolitis |

References

- Simpson, K.E.; Hulse, E.; Carlson, K. Atrial Tachyarrhythmias in Neonatal Enterovirus Myocarditis. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009, 30, 827–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Tang, J.; et al. Clinical characteristics of severe neonatal enterovirus infection: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.C.; Koay, K.W.; Ramers, C.B.; Milazzo, A.S.; Carolina, N. Neonate with Coxsackie B Infection, Cardiomyopathy and Arrhythmias.

- Madden, K.; Thiagarajan, R.R.; Rycus, P.T.; Rajagopal, S.K. Survival of neonates with enteroviral myocarditis requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2011, 12, 314–318. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry-Waterman, N.; Nashed, L.; Chidester, R.; et al. A Prospective Evaluation of Arrhythmias in a Large Tertiary Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Pediatr Cardiol. 2023, 44, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeggi, E.; Öhman, A. Fetal and Neonatal Arrhythmias. Clinics in Perinatology. 2016, 43, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruder, D.; Weber, R.; Gass, M.; Balmer, C.; Cavigelli-Brunner, A. Antiarrhythmic Medication in Neonates and Infants with Supraventricular Tachycardia. Pediatr Cardiol. 2022, 43, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.T.; Potts, J.E.; Radbill, A.E.; et al. Permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia in children: A multicenter experience. Heart Rhythm. 2014, 11, 1426–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, S.; Fettah, N.D.; Tuğcu, A.U.; Koyuncu, E.; Yoldaş, T.; Zenciroğlu, A. Supraventricular tachycardia after respiratory syncytial virus infection in a newborn. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 2022, 35, 705–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, M.; Keller, C.P.T.L.; Franca, H.; Mehrotra, K. Mycoplasma myocarditis presenting with sustained SVT and acute heart failure without signs of myocardiocytolysis and extra-cardiac disease. Clinical Case Reports. 2024, 12(5). [CrossRef]

- Muehlenbachs, A.; Bhatnagar, J.; Zaki, S.R. Tissue tropism, pathology and pathogenesis of enterovirus infection. The Journal of Pathology. 2015, 235, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaaloul, I.; Riabi, S.; Evans, M.; Hunter, T.; Huber, S.; Aouni, M. Postmortem diagnosis of infectious heart diseases: A mystifying cause of Sudden Infant Death. Forensic Science International. 2016, 262:166-172. [CrossRef]

- Neagu, O.; Rodríguez, A.F.; Callon, D.; Andréoletti, L.; Cohen, M.C. Myocarditis Presenting as Sudden Death in Infants and Children: A Single Centre Analysis by ESGFOR Study Group. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2021, 24, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grangeot-Keros, L.; Broyer, M.; Briand, E.; et al. Enterovirus in sudden unexpected deaths in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis, J. 1996, 15, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, O.H.; Svedin, E.; Kapell, S.; Nurminen, A.; Hytönen, V.P.; Flodström-Tullberg, M. Enteroviral proteases: structure, host interactions and pathogenicity: Pathogenicity of enteroviral proteases. Rev Med Virol. 2016, 26, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venteo, L.; Bourlet, T.; Renois, F.; et al. Enterovirus-related activation of the cardiomyocyte mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in patients with acute myocarditis. European Heart Journal. 2010, 31, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouin, A.; Gretteau, P.A.; Wehbe, M.; et al. Enterovirus Persistence in Cardiac Cells of Patients With Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy Is Linked to 5’ Terminal Genomic RNA-Deleted Viral Populations With Viral-Encoded Proteinase Activities. Circulation. 2019, 139, 2326–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aretz, H.T.; Billingham, M.E.; Edwards, W.D.; et al. Myocarditis. A histopathologic definition and classification. Am J Cardiovasc Pathol. 1987, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Law, Y.M.; Lal, A.K.; Chen, S.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Myocarditis in Children: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021, 144(6). [CrossRef]

- Batra, A.S.; Silka, M.J.; Borquez, A.; et al. Pharmacological Management of Cardiac Arrhythmias in the Fetal and Neonatal Periods: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024, 149(10). [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.T.; Kim, Y.H.; Kwon, J.E. Effective Control of Supraventricular Tachycardia in Neonates May Requires Combination Pharmacologic Therapy. JCM. 2022, 11, 3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, O.A.; Herrick, N.L.; Borquez, A.A.; et al. Antiarrhythmic Treatment Duration and Tachycardia Recurrence in Infants with Supraventricular Tachycardia. Pediatr Cardiol. 2021, 42, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecarini, F.; Comitini, F.; Bardanzellu, F.; Neroni, P.; Fanos, V. Neonatal supraventricular tachycardia and necrotizing enterocolitis: case report and literature review. Ital J Pediatr. 2020, 46, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, M.W.; Kleinveld, G.; Krediet, T.G.; Van Loon, A.M.; Verboon-Maciolek, M.A. Prognosis for neonates with enterovirus myocarditis. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2010, 95, F206–F212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.; Hellenbrand, W.E.; Gallagher, P.G. Atrial Flutter Complicating Neonatal Coxsackie B2 Myocarditis. Pediatr Cardiol. 1998, 19, 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampetruzzi, S.; Sirico, D.; Mainini, N.; et al. Neonatal Enterovirus-Associated Myocarditis in Dizygotic Twins: Myocardial Longitudinal Strain Pattern Analysis. Children. 2024, 11, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, J.H. ECHO 11 VIRUS OUTBREAK IN A NURSERY ASSOCIATED WITH MYOCARDITIS. J Paediatr Child Health. 1973, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.R.; Ko, S.Y.; Yoon, S.Y.; Lee, Y.K.; Shin, S.M. Early Detection and Successful Treatment of Vertically Transmitted Fulminant Enteroviral Infection Associated with Various Forms of Arrhythmia and Severe Hepatitis with Coagulopathy. Pediatr Infect Vaccine. 2019, 26, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjac, L.; Nikcević, D.; Vujosević, D.; Raonić, J.; Banjac, G. Tachycardia in a newborn with enterovirus infection. Acta Clin Croat. 2014, 53, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weickmann, J.; Gebauer, R.A.; Paech, C. Junctional ectopic tachycardia in neonatal enterovirus myocarditis. Clinical Case Reports. 2020, 8, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, Y.; Wada, M. Accelerated ventricular rhythm associated with myocarditis in a neonate. Pediatr Cardiol. 1989, 10, 178–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).