1. Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is currently 3rd in globally ranked deaths related to cancer with close to 783,000 deaths each year [

1,

2]. As the 5th most diagnosed malignancy, nearly one million new incidents are reported every year with most cases diagnosed in advanced stages due to lack of early signs and symptoms [

2]. Incidence is highest in the Eastern/Central Asia and Latin America region with established risk factors such as

Helicobacter pylori infection, chronic tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and diet. Currently, first-line treatment options for advanced HER2-negative GC are PD-L1 inhibitor immunotherapy plus fluoropyrimidine and platinum combined chemotherapy with progression free survival (PFS) at 10.5 months and overall survival (OS) at 17.5 months [

3]. Although the addition of targeted immunotherapy served as a breakthrough discovery in treatment of advanced GC, the overall prognosis of these patients remains poor with a desperate need for new treatment options.

There is growing interest in the microbiome as a contributor to gastrointestinal cancer pathophysiology. Integrating microbiome data with other multi-omics biomarkers holds promise not only for predicting cancer risk but also for distinguishing early-onset cases suggesting its emerging role as a valuable predictive tool in precision oncology [

4]. The gut microbiota is the total collection of microorganisms within the gastrointestinal tract with functions that help sustain normal body physiology which includes the metabolism of nutrients, enhancing innate immunity, and maintaining the integrity and function of the intestinal tract. Pathogenic alterations of the gastric microbiota, known as dysbiosis, reduces the diversity of commensal microorganisms and results in decreased tumor immunity with the disinhibited production of pro-inflammatory markers. The compositional differences of the gut microbiota in precancerous versus malignant conditions has become of crucial value in the clinical setting as they carry heavy implications of novel biological markers which may help predict peritoneal carcinomatosis and serve as new therapeutic targets, potentially enhancing treatment response of currently available systemic and immunologic therapy.

Bifidobacterium is a gram-positive/anaerobic commensal with remarkable tumor suppressive properties with recent studies highlighting its role in enhancing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy [

4]. This genus is frequently observed to be downregulated in GC and is one of few biomarkers with incredible prospective value in clinical metastatic GC treatment. However, even with the emergence of these novel biomarkers, further investigation is needed before its implementation into actual practice. Therefore, the objective of this review is to further determine clinically relevant biomarkers of the gastric microbiome and their influence on tumor immunity in the setting of metastatic GC.

2. Microbial Signatures in Pre-Cancerous Versus Cancerous Gastric Mucosa

The healthy gut microbiome contains a diverse population of microorganisms throughout the gastrointestinal tract and is composed of nearly 35,000 bacterial species. These populations are not random in distribution as certain genera are observed to predominate different sections of the GI tract. As described by Jandhyala et al. the predominant phyla of the entire gut are the

Firmicutes,

Bacteroidetes,

Actinobacteria, and

Verrucomicrobia, whereas the most common genera in the gastric mucosa are the

Helicobacter,

Streptococcus,

Prevotella,

Veillonella, and

Rothia. These commensal organisms naturally inhabit the gastric mucosa and maintain population numbers in balanced ratios with each other [

5]. As certain bacterial populations are observed to increase or decrease in relative abundance, identifying these biomarkers and mechanisms towards cancer progression may be vital in the development and utility of therapeutic interventions to target pathways that may show clinical promise in the treatment of metastatic GC.

Helicobacter pylori infection is the greatest risk factor for GC development with its carcinogenic effects mediated through elusive virulence factors that confer its survival in the acidic gastric environment. Although its primary mechanism in GC carcinogenesis is through the production of inflammatory markers and oxidative stress,

H. pylori is a direct cause of decreased gut microbial diversity, a process known as dysbiosis which suggests a concomitant pathway in GC carcinogenesis [

6]. Guo et al. elaborated the changes in the microbiome due to

H. pylori by comparing changes in stool microbial 16S ribosomal RNA in

H. pylori infected subjects who succeeded/failed eradication therapy vs subjects without

H. pylori infection. Results demonstrated that subjects with known

H. pylori infection who successfully underwent eradication therapy had a significant increase in microbial diversity and richness (P<0.001), measured by Shannon index, with no statistical difference in diversity and richness compared to the negative control group (P=0.420, P=0.493 respectively). Taxonomic groups directly related to

H. pylori were also shown to significantly decrease in abundance post eradication therapy via gastric biopsy analysis with subsequent lower levels of Proteobacteria (phylum) and

Helicobacter (genus) [

6]. In contrast, certain phylum groups observed to have a significant increase in abundance post eradication therapy included

Bacteroidetes,

Fusobacteria,

Actinobacteria, and

Firmicutes. Via paired stool samples, successful eradication therapy showed a significant increase in both the

Clostridiales and

Bifidobacteriales order with a decrease in the

Bacteroidales order. The observed changes in bacterial taxonomic groups post successful

H. pylori eradication therapy are consistent with the normal distribution of gut flora described by Jandhyala et al. This review paper describes that the

Bacteroidetes,

Firmicutes, and

Actinobacteria phylum are generally the predominant taxonomic groups in the healthy gut. However, this paper explains the temporal variance of distribution from the esophagus to the cecum with

Bacteroidetes and

Bifidobacterium strongly considered as luminal bacteria while

Clostridium is predominant in both the lumen and mucosa aspect of the GI tract [

6].

While Jandhyala et al. extensively studied GC secondary

to H. pylori infection and its direct effects to the gastric microbiome, Zhang et al. performed a meta-analysis of 33 eligible case-control studies to comprehensively compare the microbiome in patients with GC, regardless of

H. pylori status. The primary outcomes for this study were changes in bacterial composition in patients with GC cancer compared those without and differences in biodiversity per Shannon index. Inclusion criteria for this study were adults diagnosed with GC via tissue biopsy and the control group consisting of non-GC subjects undergoing biopsy which also includes groups comprised of individuals with no known GC undergoing endoscopy or gastric biopsy including those with precancerous lesions such as chronic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia. Diversity was measured utilizing Shannon’s index which showed a statistically lower α-diversity in subjects with GC [-5.078 (-9.470, -0.686). At the phylum level, meta-analysis showed that there was no significant difference in

Actinobacteria,

Bacteroidetes,

Firmicutes,

Clostridia, and

Proteobacteria in individuals with and without GC. Interestingly, these results show some discordance with the previously mentioned study by Guo et al. as her results reflected relative phyla populations post

H. pylori eradication therapy which showed a decrease in

Proteobacteria with an increase in

Bacteroidetes,

Firmicutes, and

Actinobacteria. However, at the genus level, the meta-analysis did show a significant increase of

Lactobacillus and

Streptococcus [5.474 (0.949, 9.999), P=0.20], [5.095 (0.293, 9.897), P=0.038] with an identical decrease in both

Porphyromonas and

Rothia [-8.602 (-11.396, -5.808) [

7].

An important logistical factor regarding this study is the external validity as most of the subjects studied were from East Asia with few from Portugal, Mexico, and Lithuania. Although these populations are most affected by GC on the global scale, variations of microbial compositions specific to select regions must be considered in those with and without GC for gastric microbial biomarkers to be appropriately utilized in GC treatment.

Liu et al. was particularly interested in potential biomarkers from the intestinal microbiota as the number of bacteria is close to hundreds of millions of times that of the stomach and is the largest functional immune unit within the total immunological system. With these implications, Liu et al. compared stool samples between healthy and GC patients via 16S sRNA sequencing and determined that phylum level

Proteobacteria,

Desulfovibrio, and

Escherichia were significantly increased in feces in patients with GC (P<0.05, P<0.05, P< 0.01, respectively) [

8]. This study explored the potential role of the gut microbiota, specifically

Desulfovibrio, in GC (GC) development. To investigate the underlying mechanism, HT-29 colon cancer cells were treated with sodium hydrogen sulfide (NaHS), a hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) donor, to mimic microbial influence. Exposure to 50 μM NaHS led to a significant increase in nitric oxide (NO) production compared to control cells treated with phosphate-buffered saline. This was accompanied by upregulation of NOS2 mRNA, indicating enhanced activity of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Inflammatory responses were also elevated, as evidenced by increased production of IL-1β and IL-18, two key pro-inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, there was an upregulation of NOS2 mRNA expression, indicating enhanced inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity. Inflammatory responses were similarly elevated, as shown by significantly increased production of IL-1β and IL-18, two key pro-inflammatory cytokines. These findings suggest that

Desulfovibrio-derived metabolites like hydrogen sulfide may promote a pro-inflammatory environment and contribute to gastric carcinogenesis, positioning gut microbial products as potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets for early GC detection [

8].

Further studies should also include differences in the microbiome in more taxonomic categories to establish other correlations of GC to microbial groups.

3. Key Bacterial Biomarkers in the Development of GC

Microbial signatures discussed in the previous section are further discussed here as potential biomarkers that may help predict or modulate GC in patients.

3.1. Desulfovibrio

Desulfovibrio is a genus of gram negative, sulfate reducing bacteria from the class Deltaproteobacteria. Commonly found in the gut microbiome, it plays a role in maintaining microbial balance but can also contribute to gastrointestinal disease under certain conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer and irritable bowel syndrome.

Desulfovibrio species use sulfate as an electron acceptor and produce H₂S as a metabolic byproduct which may contribute to DNA damage and carcinogenesis. Foods rich in sulfate such as red meat and processed foods can promote

Desulfovibrio growth and H₂S production. In a study by Liu et. al., patients with stage IV GC were identified to have significantly more

Desulfovibrio than those with stage I, II, and III. In fact, of the 10 hosts who have greater than 1% fecal

Desulfovibrio, 9 have GC.

Desulfovibrio has also been observed with other bacteria. For example, Cao

et. al., investigated the effect of adding

Clostridium butyricum (C. butyricum) in GC patients after gastrectomy. They found that adding

C. butyricum, decreased pathologic bacteria such as

Desulfovibrio at the genus level [

8].

3.2. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus

The Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus genera are both gram positive/anaerobe commensal groups, extensively found throughout the healthy GI tract and are known to be key players in maintaining gut homeostasis. There is no coincidence that these groups are marketed in the probiotic industry with purposes to improve gut health, however, their therapeutic value in the realm of advanced GC remains under investigation. As further discussed in the previous sections, Bifidobacterium is found to be downregulated in GC while Lactobacillus is generally observed to be upregulated.

A preclinical study by Kim et al. investigated anti-tumor effects of

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus on cancerous cells by first analyzing the cytotoxic effect of these genera via MTT assay. Human GC MKN1 cells were treated with multiple heat-killed

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus species. MKN1 cell viability showed the greatest reduction with

Bifidobacterium bifidum (

B. bifidum) and

Lactobacillus rhamnosus (

L. rhamnosus) treatment with only 25.77% (P<0.05) and 57.33% (P<0.05) of GC cells left viable post treatment, respectively, compared to the untreated group [

9].

Kim et al. next investigated the pro-apoptotic effects of

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus via Annexin V-FITC and PI staining with subsequent flow cytometry. MKN1 cells were treated with heat killed

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus strains for 24 hours with total apoptosis % measured. Compared to control, all treated MKN1 cells had significantly increased total apoptosis % (P<0.05) with the greatest effect observed by

B. bifidum and

L. reuteri (13.3% and 24.6%, respectively). Kim et al. conducted an in vivo study using mice models grafted with MKN1 cells to analyze the effect of heat-treated Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus on tumor size. With a total of six groups including the control, the experimental groups were orally treated with either Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species or a mixture of both at different concentrations. All experimental groups showed a significant reduction in tumor volume with the greatest effect demonstrated by the mixture group comprised of

B. bifidum,

L. reuteri, and

L. rhamnosus at the higher concentration (3Mix-3), and

B. bifidum alone (MG731), with tumor volume of 122 ± 27 mm3 and 136 ± 22 mm3 respectively compared to control at 318 ± 15 mm3 on day 19 (P<0.05) [

9]. The tumor suppressive effects of

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus can be explained by their regulation on cellular proliferation and apoptosis via the akt-p53 pathway. Akt is a protein kinase that downregulates p53, a key tumor suppressor protein with roles of activating Bax and Bak to induce apoptosis. To determine the effect of

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus on this pathway, Kim et al. quantified the relative expression levels of these molecular markers in all groups, via Western blot and found that their expression was significantly lower in all treatment groups compared to the control (P<0.05). The greatest negative effect of p-Akt/Akt expression was achieved by MG5200 (

L. rhamnosus) with expression levels close to ~60% that of the control group. As expected, p53 levels were significantly increased in all treatment groups (P<0.05), however, the greatest effect was observed by the 3Mix-3 group with levels 2.48-fold compared to the control. Bax levels were significantly increased in the 3Mix-3 and the MG5200 (

L. rhamnosus) treatment group at up to ~2.25 and ~2 times the expression levels of the control, respectively (P<0.05). Similarly, Bak expression levels were significantly elevated in the 3Mix-3 and MG5200 (

L. rhamnosus) group at 2.49 and 1.86 times the expression of the control (P<0.05) [

9].

Lastly, the study determined the relative concentrations of the mitochondrial proteins that directly induce apoptosis including caspase-9, caspase-3, and PARP. Caspase-9, otherwise known as the initiator caspase, was significantly higher in concentration in its active cleaved form in treatment groups MG731 and 3Mix-3 respectively which showed an increase by 2.30 and 2.09-fold, respectively, compared to the control (P<0.05). Caspase-3, activated by cleaved caspase-9, was also found to be increased compared to control in all groups by a factor of ~1.5 with the greatest effect observed in the 3Mix-3 and MG731 treatment groups (P<0.05). PARP, a known biomarker of apoptosis, was elevated in all treatment groups with 3Mix-3 and MG5200 showing the greatest increase at ~1.4-fold compared to control (P<0.05) [

9].

Despite the promising tumor-suppressive effects of

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus observed, it remains notable that Lactobacillus is often found to be upregulated in GC tissue. Preclinical studies suggest that while certain

Lactobacillus strains exert antitumor effects through pathways like Akt-p53 mediated apoptosis, the altered gastric environment in GC, characterized by hypochlorhydria and elevated pH, favors the expansion of acid-tolerant species like

Lactobacillus [

10]. A study done by Shin et al. showed the increase in relative abundance of

Lactobacillus is caused by the increased pH in the stomach during proton pump inhibitor treatments, allowing the overgrowth of

Lactobacillus over other bacteria in the microbiome [

11]. Furthermore, Lactobacillus produces lactic acid, which can accumulate in the TME and promote tumor progression by modulating immune cell polarization and serving as a metabolic substrate for cancer cells [

12]. Thus, while certain strains may exert antitumor properties in controlled experimental settings, the general increase of Lactobacillus in GC may contribute to tumorigenesis through metabolic and immunosuppressive pathways, highlighting a complex, context-dependent role.

3.3. Streptococcus

Streptococcus is a diverse genus of Gram-positive, facultatively anaerobic bacteria that primarily colonizes the nasopharynx and gastrointestinal tract. While many

Streptococcus species are commensal and contribute to normal microbiota, others are pathogenic, causing infections ranging from mild pharyngitis to severe diseases like pneumonia, endocarditis, and necrotizing fasciitis. Notably,

Streptococcus anginosus (

S. anginosus) has been implicated in gastrointestinal diseases, including GC, due to its ability to colonize the gastric mucosa, disrupt barrier function, and promote tumorigenesis through host-microbe interactions [

13].

A study done by Fu et al. examined the role of

S. anginosus in gastric carcinogenesis as an activator to the MAPK signaling pathway through the interaction between TMPC (Tumor Microenvironment Protein C) and ANXA2 (Annexin A2). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on gastric tissues from

S. anginosus-infected conventional mice at 12 months post-infection, revealing notable changes in gene expression. Results showed that 1,727 genes were upregulated, and 1,020 genes were downregulated in infected mice compared to controls [

14].

Several oncogenic pathways, including Ras, MAPK, and PI3K-AKT demonstrated significant upregulation in the infected tissues, with the MAPK pathway showing the strongest activation. Western blotting was performed to confirm the increased phosphorylation of key proteins in the MAPK signaling pathway, including ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2), JNK (p-JNK), and AKT (p-AKT), as well as the downstream cell cycle regulators Cyclin D1 and c-Myc. These results were replicated in a chemically induced GC mouse model (MNU GC mice) at 9 months post-infection, where

S. anginosus infection also led to significant activation of MAPK signaling. These findings suggest that the persistent activation of MAPK signaling by

S. anginosus plays a crucial role in its pro-tumorigenic effects in the gastric epithelium [

14].

Fu et al. further elucidated the role of the TMPC–ANXA2 interaction in the activation of the MAPK signaling pathway. In vitro co-culture experiments using Streptococcus anginosus with human gastric epithelial cells (GES-1) and gastric cancer (GC) cell lines (AGS) revealed activation of phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2), AKT (p-AKT), and JNK (p-JNK). Notably, this activation was abolished upon knockout of ANXA2 in these cell lines, confirming its essential role in S. anginosus-mediated MAPK activation. Furthermore, treatment with recombinant TMPC protein alone induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, AKT, and JNK in both AGS and NCI-N87 GC cells, highlighting the critical involvement of TMPC in the pro-tumorigenic signaling cascade. In vivo studies using YTN16 allograft models demonstrated that TMPC deletion prevented the activation of p-ERK1/2 and p-JNK, underscoring TMPC’s necessity in MAPK pathway activation in response to S. anginosus infection. Additionally, recombinant TMPC protein alone was capable of inducing p-ERK1/2, p-AKT, and p-JNK phosphorylation in both AGS and NCI-N87 GC cells, further demonstrating the significance of TMPC in mediating the pro-tumorigenic signaling of

S. anginosus [

14]. Collectively, these findings indicate that S. anginosus promotes MAPK signaling via TMPC–ANXA2 interaction, contributing to a pro-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic gastric microenvironment that facilitates GC development. [

14].

3.4. Rothia and Porphyromonas

Rothia and

Porphyromonas, both components of the normal oral and gastric microbiota, have emerged as significant taxa in the context of GC. A meta-analysis of 30 studies revealed a consistent and significant decrease in the abundance of these genera in GC patients compared to controls, with both exhibiting identical log odds ratios of −8.602 (95% CI: −11.396, −5.808) [

7].

Rothia, a member of the Actinobacteria phylum, is typically part of the healthy gastric core microbiome [

15]. It is known to produce butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) with anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory properties. Butyrate has been shown to suppress immunosuppressive markers such as PD-L1 and IL-10 in immune cells and inhibit tumor growth in vivo. The depletion of

Rothia may disrupt the local immune environment and compromise mucosal defense, contributing to GC pathogenesis. Additionally, SCFAs support epithelial barrier function and immune homeostasis by modulating macrophage and Th17 cell activity. Therefore, the depletion of

Rothia may reduce local butyrate availability, compromise mucosal defense and contribute to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in GC [

16].

Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis), a key periodontal pathogen, produces lipopolysaccharide (LPS) with distinctive immunomodulatory properties that may contribute to gastric carcinogenesis. Unlike classical endotoxins,

P. gingivalis LPS selectively activates p38 MAP kinase in human monocytes but not in endothelial or TLR4-transfected CHO cells, as demonstrated by Darveau et al. suggesting a cell-type-specific immune evasion strategy. Moreover, it inhibits E. coli-induced activation of inflammatory markers such as E-selectin and IL-8 in endothelial cells, further illustrating its capacity to subvert host immune responses and facilitate persistent colonization [

17].

Recent studies have expanded this understanding to the gastric environment, where epidemiological data supports a link between periodontal disease and GC. A study done by Oriuchi et al. examined this correlation. Results revealed that

P. gingivalis LPS was shown to compromise epithelial barrier integrity and upregulate TLR2, TNFα, and apoptosis-associated genes, indicating heightened susceptibility to inflammation-induced damage in GC patient-derived gastric mucosa. In an in vitro study,

P. gingivalis LPS triggered reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated apoptosis and activated TLR2–β-catenin signaling in gastric epithelial cells. This further amplifies ROS production and β-catenin signaling in epithelial cells, establishing a pro-inflammatory feed forward loop. in vivo studies in which oral administration of

P. gingivalis LPS in K19-Wnt1/C2mE transgenic (Gan) mice showed tumor enlargement, macrophage infiltration, elevated TNFα, and increased β-catenin activation. These discoveries highlight a novel mechanism where

P. gingivalis LPS may promote gastric tumorigenesis through immune modulation, barrier disruption, and sustained pro-tumorigenic signaling [

18].

While

P. gingivalis demonstrates tumorigenic properties through its LPS-mediated modulation of immune responses and promotion of pro-inflammatory signaling in gastric tissues, meta-analyses have reported a decreased abundance of this bacterium in patients with GC [

7]. This apparent discrepancy may be explained by the fact that P. gingivalis primarily colonizes the oral cavity, and its presence in the stomach likely results from transient oral-gastric translocation rather than stable colonization [

19]. Additionally, the acidic environment of the stomach may not favor long-term survival of

P. gingivalis, leading to its reduced detection in GC tissues [

20]. However, even in reduced abundance,

P. gingivalis LPS can still exert significant pathogenic effects on gastric epithelial cells, such as activation of TLR2–β-catenin signaling, generation of ROS, and disruption of epithelial barrier integrity, all of which contribute to a pro-tumorigenic environment [

18].

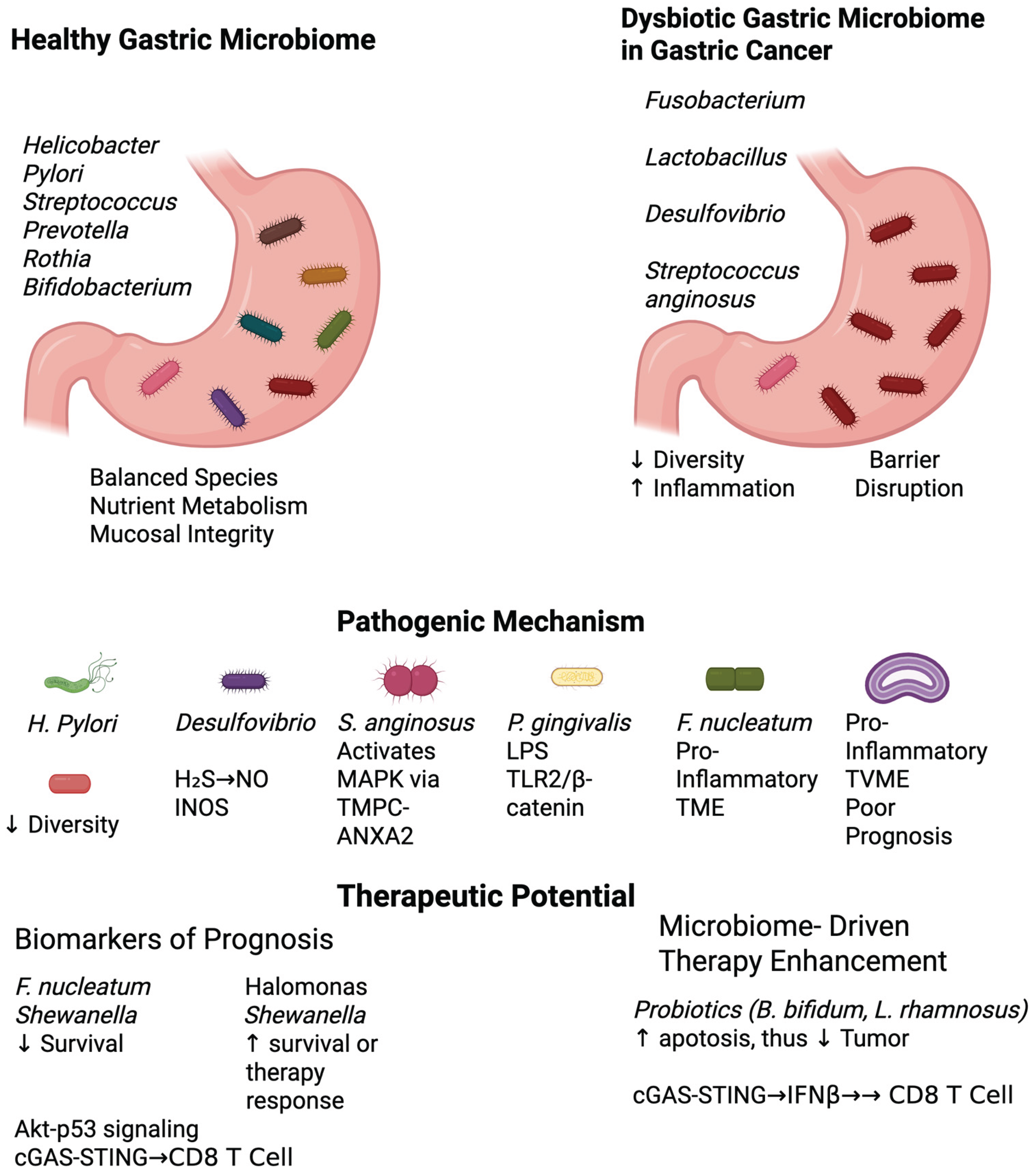

Figure 1.

Microbiome Signatures in Gastric Carcinogenesis and Treatment Response. TVME: Tumor-Associated Variable Microbial Environment, TME: Tumor Microenvironment.

Figure 1.

Microbiome Signatures in Gastric Carcinogenesis and Treatment Response. TVME: Tumor-Associated Variable Microbial Environment, TME: Tumor Microenvironment.

Table 1.

Key Biomarkers of the Gastrointestinal Tract in GC.

Table 1.

Key Biomarkers of the Gastrointestinal Tract in GC.

| Biomarker |

Classification |

Properties |

GI Tract Prevalence |

Relative Abundance |

Role in GC |

| Desulfovibrio |

Gram-negative rod, anaerobe |

Sulfate- reducer |

Colon |

Increased in GC |

H₂S byproduct contributes to DNA damage and promotes carcinogenesis [8]. |

| Bifidobacterium |

Gram-positive rod (Y or V shape), anaerobe |

Utilizes fructose-6-phosphoketase (F6PPK) to produce acetate and lactate |

Colon |

Decreased in GC |

Both regulate cellular proliferation and apoptosis via akt-p53 pathway to induce apoptosis [9]. Lactobacillus has a potential dual role in tumorigenesis through lactic acid production to promote tumor growth [11]. |

| Lactobacillus |

Gram-positive rod, anaerobe |

Produces lactic acid through anaerobic fermentation |

Stomach, Small intestine, Colon |

Increased in GC |

| Streptococcus |

Gram-positive cocci, facultative/strict anaerobe |

Catalase-negative |

Esophagus, Stomach, Small intestine, Colon |

Increased in GC |

Induces a pro-inflammatory state and TME favorable for GC progression via MAPK signaling pathway via TMPC-ANXA2 interaction [14]. |

| Rothia |

Gram-positive rod, aerobe |

Produces butyrate, a SCFA |

Esophagus |

Decreased in GC |

Produces butyrate which suppress PD-L1 and IL-10 in immune cells and inhibit tumor growth [16]. |

| Porphyromonas |

Gram-negative rod, anaerobe |

Produces major virulence factors such as LPS |

Colon |

Decreased in GC |

LPS triggers ROS-mediated apoptosis with TLR2-β-catenin activation in gastric epithelial cells, promoting a pro-inflammatory feed forward loop [18]. |

Table 2.

Current Clinical Trials on Microbiome Biomarkers in GC Peritumoral Microbiota as Prognostic Indicators.

Table 2.

Current Clinical Trials on Microbiome Biomarkers in GC Peritumoral Microbiota as Prognostic Indicators.

| Trial Name |

Focus |

Sponsor |

Status |

ClinicalTrials.gov ID |

| Gut Microbiota and Immunotherapy Outcomes |

Predict immunotherapy response in advanced GC |

Sun Yat-Sen University |

Recruiting |

NCT05308753 |

| Gut Microbiota and Perioperative Outcomes |

Correlate pre-op microbiota with surgery outcomes |

Beijing Cancer Hospital |

Recruiting |

NCT04977364 |

| Microbiome and Neoadjuvant Therapy Response |

Microbiome changes before/after neoadjuvant therapy |

Seoul National University |

Active, not recruiting |

Not listed |

| Gut Microbiome and Chemotherapy Toxicity |

Predict chemotherapy-related toxicity |

University of Heidelberg |

Recruiting |

NCT04877386 |

| Microbiome-Guided Immunotherapy |

Personalized microbiome modulation before immunotherapy |

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute |

Recruiting |

NCT05692361 |

A study analyzing gastric mucosal microbiota found that higher abundances of

Halomonas and

Shewanella in peritumoral tissues were associated with poorer patient outcomes, whereas increased levels of

Helicobacter correlated with better prognoses [

21]. The combination of these three genera yielded a prognostic model with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.749, indicating moderate predictive power for patient survival.

Fusobacterium nucleatum was identified as being significantly associated with worse overall survival in GC patients. This association was validated using data from The Cancer Microbiome Atlas (TCMA), underscoring the potential of intratumoral microbiota as prognostic markers. A recent study leveraging previously published 16S rRNA gene sequencing data evaluated the prognostic significance of the gastric mucosal microbiota in GC. The analysis included a retrospective cohort of 132 GC patients with complete prognostic data with 50% of late stage III and IV, from whom 78 normal, 49 peritumoral, and 112 tumoral tissue samples were analyzed. Distinct microbial compositions and diversity were observed between patients with favorable and poor prognoses, early and late stages of GC. Notably, patients with poor outcomes exhibited a more complex microbial interaction network. In the peritumoral microenvironment,

Helicobacter was enriched in patients with good prognoses, whereas

Halomonas and

Shewanella were significantly elevated in those with poor prognoses. Functional prediction using PiCRU St indicated that the peritumoral microbiota harbored a greater number of differential KEGG pathways compared to tumoral and normal tissues. Collectively, these findings underscore the potential utility of gastric mucosal microbiota profiles as prognostic biomarkers in GC [

21].

4. Microbial Signatures Reflecting Tumor Aggressiveness

Another study demonstrated that specific microbial signatures within gastric tumors are associated with tumor aggressiveness. Notably, increased abundance of Fusobacterium and Prevotella was correlated with more aggressive tumor phenotypes and poorer clinical outcomes.

Using GC samples,

Fusobacterium nucleatum (

F. nucleatum) was identified as significantly associated with worse overall survival. This was validated using The Cancer Microbiome Atlas (TCMA), supporting its utility as a prognostic biomarker. In a cohort study involving paired samples of tumorous (T-GC) and adjacent non-tumorous (NT-GC) tissues from 64 patients with GC (n=128), high-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing yielded approximately half a million reads, which were consolidated into 5,450 unique phylotypes spanning 19 phyla and 296 genera. The study employed Cox regression models to explore associations between microbial taxa and patient survival. Univariable analyses demonstrated that UICC stage III–IV (P=0.04), and elevated relative abundances of

Prevotella (P=0.049) and

Fusobacterium (P=0.01), were significantly associated with poorer overall survival. Importantly, in multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis, diffuse-type histology per Lauren’s classification (P=0.002) and high

Fusobacterium abundance (P=0.009) emerged as independent predictors of worse overall survival [

22]. These findings further support the prognostic relevance of the tumor-associated microbiome, particularly the pathogenic role of

Fusobacterium in aggressive GC subtypes.

Boehm et al. conducted a subgroup analysis based on Lauren’s classification, an established histopathological framework that reflects, to some extent, the underlying molecular subtypes of GC, yet remains underutilized in microbiome-focused research. While no significant survival associations were noted in the intestinal-type subgroup, diffuse-type GC patients with

Fusobacterium nucleatum-positive tumors exhibited significantly worse overall survival. To better understand the contribution of

Fusobacterium spp., particularly

F. nucleatum, to gastric carcinogenesis, the study extended its analysis to include normal gastric mucosa, as well as samples with chronic non-atrophic gastritis (CNAG) and those with atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia (AG/IM) [

23]. The presence of

F. nucleatum was then correlated with clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes, further supporting its potential role as a microbial biomarker in the diffuse-type GC subtype. These findings suggest that profiling the gastric tumor microbiome could serve as a valuable tool in predicting patient prognosis and tailoring treatment strategies. Incorporating microbial biomarkers into existing prognostic models may enhance the precision of risk stratification and inform decisions regarding therapeutic interventions.

Co-infection with

H. pylori and

F. nucleatum was associated with a higher tumor mutation burden (TMB) and ERBB2-PIK3-AKT-mTOR pathway alterations, both linked to poor survival outcomes [

24].

5. Gastric Microbiome Signatures as Predictive Biomarkers of Response to Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy

With increasing evidence that the gastric microbiome dynamically changes with the progression of GC with the introduction of novel bacterial biomarkers, its application with currently available management with surgery, chemotherapeutic agents, and immunotherapy must be considered to monitor cancer progression and improve clinical outcome in GC patients.

5.1. Roseburia Faecis Predicts Response to Chemotherapy in Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancers

Li et al. demonstrated the utility of

Roseburia faecis (

R. faecis) as a biomarker to predict response to chemotherapy in patients with advanced or metastatic gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies. 130 patients were enrolled with the following GI cancer distributions: Esophageal (n=40), gastric (n=46), colorectal cancer (n=44). 53 of the 130 patients had chemotherapy efficacy data with

R. faecis abundance measured before and after via 16S rRNA sequencing. Patients who responded to chemotherapy were categorized into the response group, partial response (PR) and stable disease (SD), and the no response group, progressive disease (PD), per RECIST 1.1 guidelines. Results showed that responders (PR+SD) to chemotherapy had a significant increase of

R. faecis abundance compared to the non-responders (PD) (P=0.028). Subgroup data showed that PR and SD patients endorsed a 69.2% and 57.6% increase in

R. faecis abundance compared to PD patients at only 14.3%. Although increased

R. faecis abundance is associated with chemotherapy response,

R. faecis as a prognostic biomarker may be limited. The median progression free survival (PFS) for patients with increased and decreased

R. faecis abundance was 12.0 months and 2.0 months respectively with no significant difference (P=0.613). A major limitation of this study is that only 53 patients with GI cancers were studied which may limit the power of statistical analyses performed in this group. Another limitation includes the lack of standardization of treatment as the choice of standard chemotherapy was per physicians’ choice. Future studies should include a larger sample size with a focus on advanced/metastatic GC with standardization of therapy and re-analysis of

R. faecis as a prognostic biomarker for PFS [

25].

5.2. Lactobacillus Rhamnosus (LGG) Has Synergistic Effects with Standard Immunotherapy and Chemotherapy for Treatment of GC in Murine Models

As the previous study focused on the association of R. faecis and chemotherapy response, Han et al. established the Lactobacillus genus as a potential prognostic biomarker in patients with HER-2 negative advanced GC/GJ adenocarcinoma. A total of 117 patients were enrolled and subdivided into three treatment groups consisting of XELOX chemotherapy alone (n=27), anti PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy alone (n=58), and combined XELOX chemotherapy/immunotherapy (n=32). Fecal samples were collected before treatment initiation and throughout the treatment course and results showed that patients receiving ICI or ICI/chemotherapy with high abundance of Lactobacillus experienced a significantly higher PFS compared to those with low abundance of Lactobacillus (P=0.024, P=0.013 respectively) [

26]. Lactobacillus as a positive prognostic biomarker and synergistic effect with ICI likely stems from its ability to enhance ICI response via cGAS/STING-dependent type I interferon production.

Wei et al. investigated the effect of oral administration of

Lactobacillus rhamonosus GG (LGG) and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy on tumor burden in murine models injected with MC38 colon adenocarcinoma cells. Results showed that after 34 days, tumor volume in mice with combined anti-PD-1 and LGG treatment was significantly lower at close to 50 mm^3 compared to anti-PD-1 treatment alone at close to 1500 mm^3 (P<0.0001). Percent survival of mice with combined anti-PD-1 and LGG treatment was also significantly higher at ~50% at 45 days compared to mice who received anti-PD-1 treatment alone with percent survival at 0% at 45 days (P <0.05). Wei et al. determined that the enhanced response with combination anti-PD-1 and LGG therapy is due to increased activation of CD8+ T cells measured by flow cytometry. Results showed that mice with combination anti-PD-1+LGG therapy showed a significant increase of CD8+ T cells in MC38 tumors on day 28 at ~12% compared to anti-PD-1 monotherapy at ~6% (P<0.001) [

27].

Building on the findings of Wei et al., which demonstrated synergistic effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, Rahimi et al. investigated the impact of LGG supplementation in combination with capecitabine chemotherapy on tumor burden in murine models implanted with human gastric cancer cells. Tumor volumes were measured after six weeks of treatment. Mice treated with capecitabine alone exhibited a mean tumor volume of 189.17 mm³, while those receiving the combination of capecitabine and LGG showed a significantly lower mean tumor volume of 71.28 mm³. Both treatment groups demonstrated significant tumor volume reductions compared to control mice (247.12 mm³; P<0.05 for capecitabine alone, P<0.001 for the combination). Notably, the combined LGG-capecitabine group exhibited a significantly greater reduction in tumor volume than the capecitabine-only group (P<0.01), indicating a potential synergistic therapeutic effect.[

28]. Overall, these results suggest that LGG in conjunction with standard therapy is superior compared to standard therapy alone.

5.3. Lactobacillus Rhamnosus (LGG) Induces Type I IFN Production via Activation of the cGAS and STING Pathway

The anti-tumorigenicity of LGG was demonstrated by its ability to induce type I IFN production in murine mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) of dendritic cells via activation of the cGAS/STING pathway. Results showed that LGG treated DCs induced significantly higher production of IFN-Beta at ~50 pg/ml compared to control at <10 pg/mL (P<0.0001) and LGG treated cGAS and STING deficient murine bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) demonstrated a significantly decreased amount of IFN-Beta production at ~11 pg/mL and ~15 pg/mL compared to control at ~42 pg/mL (P<0.0001, P<0.01 respectively) [

27]. These results show that LGG directly enhances immunogenic response via increased production of IFN-Beta through the cGAS and STING pathway and should strongly be considered as adjunctive therapy with currently available ICI in patients with GC.

The relationship between the microbiome and chemotherapy is inherently complex, characterized by reciprocal interactions. The microbiome has been shown to influence the metabolism of chemotherapeutic agents, which may impact both their efficacy and toxicity profiles. Conversely, chemotherapy can disrupt the composition and function of the gut microbiota, potentially contributing to treatment resistance and increased adverse effects. These insights are driving a paradigm shift toward microbiome-informed therapeutic strategies, in which modulation of the gut microbiota may enhance treatment outcomes and mitigate chemotherapy-related toxicity.

Chrysostomou et al. summarized the gut microbiome in cancer drug metabolism.

The study of cytotoxic chemotherapy underscores the microbiome’s role in modulating chemotherapy efficacy and toxicity, particularly through its capacity to metabolize cytotoxic agents such as irinotecan into active or toxic metabolites. Bacterial β-glucuronidases have been identified as key enzymes in this process [

29]. Understanding the dynamic interaction between the onco-microbiome and host across different treatment phases, pre-treatment, during therapy, and post-treatment—may enable clinically meaningful profiling of GC staging and response. However, data on onco-microbiome composition and function across these stages remain limited. Future prospective studies are needed to characterize the metabolic and immunosurveillance profiles of microbial biomarkers throughout the treatment continuum. Such insights may pave the way for more personalized therapy strategies in GC patients, ultimately improving clinical outcomes. Additionally, the use of multi-species probiotics has shown promise in preventing chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal toxicity by restoring gut microbial balance and reducing diarrhea, a common and debilitating side effect in this patient population.

Since sodium butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) produced by commensal gut microbiota, enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis in GC cells via the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, the presence or abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria in the gut (e.g.,

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii,

Roseburia spp.,

Eubacterium spp.) could serve as a predictive biomarker for chemotherapy sensitivity [

30]. Patients with a microbiome enriched in butyrate-producing species may exhibit improved responses to cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Thus, profiling the gut microbiota before treatment could identify patients more likely to benefit from standard or butyrate-enhanced chemotherapy regimens, offering a pathway for personalized therapeutic strategies in GC.

This study explored the potential role of the gut microbiota, specifically Desulfovibrio, in GC development. Researchers treated HT-29 colon cancer cells with sodium hydrogen sulfide (NaHS), a precursor of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), to model microbial influence. Cells exposed to H₂S (50 μM NaHS) exhibited a significant increase in nitric oxide (NO) production compared to control cells treated with phosphate-buffered saline [

30].

6. Future Directions

The study of the microbiome in clinical contexts faces several significant challenges and promising opportunities. One major hurdle is standardization, as there is no universal agreement on sample collection methods (e.g., biopsy vs. stool), sequencing strategies (16S rRNA vs. shotgun metagenomics), or data analysis pipelines, leading to inconsistent results across studies. Additionally, confounding factors such as antibiotic use, diet, and geographic location can significantly skew microbial profiles, complicating comparisons. A further limitation lies in distinguishing causation from correlation since many studies remain observational and do not establish direct causal relationships. On the other hand, exciting opportunities lie ahead. Integrative omics, the combination of microbiome data with transcriptomics, metabolomics, or circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), holds potential to enhance the precision of predictive models. Furthermore, therapeutic modulation of the microbiome, through approaches like probiotics, fecal microbiota transplants, or dietary interventions, may offer novel ways to boost treatment efficacy and reduce side effects.

7. Conclusion

Key biomarkers within the gastric microbiome pose significant implications in the comprehensive management and treatment of GC. Due to the indolent nature of GC, diagnosis is often made at the advanced stages with poor overall outcome. The gastric microbiome is incredibly diverse, and compositions change through age and location throughout the GI tract, however, diversity and abundances of key gastric microbiome organisms deviate from normal physiological conditions with gastric mucosal inflammation and carcinogenesis. Furthermore, the gut microbiome is proven to be an immunological barrier and further implicated in altering the metabolism of chemotherapeutic drugs and enhancing immunologic pathways. Therefore, these novel biomarkers must be considered at a more comprehensive level of diagnosis and prognosis in patients with GC to stratify patients at risk for GC and to help predict the course in patients already diagnosed with GC to guide appropriate management. Although there are many pre-clinical studies of these key biomarkers that highlight their therapeutic and diagnostic role in GC, future studies should focus on human based clinical studies that utilize these biomarkers as diagnostic/prognostic tools or as adjunctive therapy with current first-line agents with chemotherapy and ICI.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: D.C., G.B. Project supervision: D.C., G.B., K.K., H.Z Manuscript preparation: K.K., H.Z., D.T., P.S., V.G., D.C. Manuscript review and editing: all co-authors. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript to be published.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thanks Dr. Dani Castillo, Dr. Sumanta Kumar Pal, Dr. Miguel Zugman, and Dr. Gagandeep Brar for their administrative support and guidance throughout the production of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rawla P, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of gastric cancer: global trends, risk factors and prevention. pg. 2019;14(1):26–38. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Yang G, Tian Y, Zhang Q, Liu Z, Xin Y. The role of the gut microbiota in gastric cancer: the immunoregulation and immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2023 Jun 30;14:1183331. [CrossRef]

- Boku N, Ryu MH, Oh DY. LBA7_PR Nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in patients with previously untreated advanced or recurrent gastric/gastroesophageal junction (G/GEJ) cancer: ATTRACTION-4 (ONO-4538-37) study. Annals of Oncology. 31(S1192). [CrossRef]

- Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, Williams JB, Aquino-Michaels K, Earley ZM, Benyamin FW, Man Lei Y, Jabri B, Alegre ML, Chang EB, Gajewski TF. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti–PD-L1 efficacy. Science. 2015 Nov 27;350(6264):1084–9. [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, SM. Role of the normal gut microbiota. WJG. 2015;21(29):8787. [CrossRef]

- Guo Y, Zhang Y, Gerhard M, Gao JJ, Mejias-Luque R, Zhang L, Vieth M, Ma JL, Bajbouj M, Suchanek S, Liu WD, Ulm K, Quante M, Li ZX, Zhou T, Schmid R, Classen M, Li WQ, You WC, Pan KF. Effect of Helicobacter pylori on gastrointestinal microbiota: a population-based study in Linqu, a high-risk area of gastric cancer. Gut. 2020 Sep;69(9):1598–607. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Wu Y, Ju W, Wang S, Liu Y, Zhu H. Corrigendum: Gut microbiome alterations during gastric cancer: evidence assessment of case–control studies. Front Microbiol. 2024 Jun 25;15:1448265. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Dai J, Lan X, Fan B, Dong T, Zhang Y, Han M. Intestinal bacteria are potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for gastric cancer. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2021 Feb;151:104747. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Lee HH, Choi W, Kang CH, Kim GH, Cho H. Anti-Tumor Effect of Heat-Killed Bifidobacterium bifidum on Human Gastric Cancer through Akt-p53-Dependent Mitochondrial Apoptosis in Xenograft Models. IJMS. 2022 Aug 29;23(17):9788. [CrossRef]

- Li ZP, Liu JX, Lu LL, Wang LL, Xu L, Guo ZH, Dong QJ. Overgrowth of Lactobacillus in gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021 Sep 15;13(9):1099–108. [CrossRef]

- Shin CM, Kim N, Kim YS, Nam RH, Park JH, Lee DH, Seok YJ, Kim YR, Kim JH, Kim JM, Kim JS, Jung HC. Impact of Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy on Gut Microbiota in F344 Rats: Pilot Study. Gut and Liver. 2016 Nov 15;10(6):896–901. [CrossRef]

- Wang JX, Choi SYC, Niu X, Kang N, Xue H, Killam J, Wang Y. Lactic Acid and an Acidic Tumor Microenvironment suppress Anticancer Immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Nov 7;21(21):8363. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, MJ. Streptococcus. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology [Internet]. 4th ed. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996 [cited 2025 Apr 27]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7611/.

- Fu K, Cheung AHK, Wong CC, Liu W, Zhou Y, Wang F, Huang P, Yuan K, Coker OO, Pan Y, Chen D, Lam NM, Gao M, Zhang X, Huang H, To KF, Sung JJY, Yu J. Streptococcus anginosus promotes gastric inflammation, atrophy, and tumorigenesis in mice. Cell. 2024 Feb;187(4):882-896.e17. [CrossRef]

- Nardone G, Compare D. The human gastric microbiota: Is it time to rethink the pathogenesis of stomach diseases? UEG Journal. 2015 Jun;3(3):255–60. [CrossRef]

- Lee SY, Jhun J, Woo JS, Lee KH, Hwang SH, Moon J, Park G, Choi SS, Kim SJ, Jung YJ, Song KY, Cho ML. Gut microbiome-derived butyrate inhibits the immunosuppressive factors PD-L1 and IL-10 in tumor-associated macrophages in gastric cancer. Gut Microbes. 2024 Dec 31;16(1):2300846. [CrossRef]

- Darveau RP, Arbabi S, Garcia I, Bainbridge B, Maier RV. Porphyromonas gingivalis Lipopolysaccharide Is Both Agonist and Antagonist for p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Activation. Infect Immun. 2002 Apr;70(4):1867–73. [CrossRef]

- Oriuchi M, Lee S, Uno K, Sudo K, Kusano K, Asano N, Hamada S, Hatta W, Koike T, Imatani A, Masamune A. Porphyromonas gingivalis Lipopolysaccharide Damages Mucosal Barrier to Promote Gastritis-Associated Carcinogenesis. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Jan;69(1):95–111. [CrossRef]

- De Jongh CA, De Vries TJ, Bikker FJ, Gibbs S, Krom BP. Mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis to translocate over the oral mucosa and other tissue barriers. Journal of Oral Microbiology. 2023 Dec 31;15(1):2205291. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Medel M, Pinto MP, Goralsky L, Cáceres M, Villarroel-Espíndola F, Manque P, Pinto A, Garcia-Bloj B, de Mayo T, Godoy JA, Garrido M, Retamal IN. Porphyromonas gingivalis, a bridge between oral health and immune evasion in gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1403089. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Xu J, Ling Z, Zhou X, Si Y, Liu X, Ji F. Prognostic effects of the gastric mucosal microbiota in gastric cancer. Cancer Science. 2023 Mar;114(3):1075–85. [CrossRef]

- Lehr K, Nikitina D, Vilchez-Vargas R, Steponaitiene R, Thon C, Skieceviciene J, Schanze D, Zenker M, Malfertheiner P, Kupcinskas J, Link A. Microbial composition of tumorous and adjacent gastric tissue is associated with prognosis of gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2023 Mar 21;13(1):4640. [CrossRef]

- Boehm ET, Thon C, Kupcinskas J, Steponaitiene R, Skieceviciene J, Canbay A, Malfertheiner P, Link A. Fusobacterium nucleatum is associated with worse prognosis in Lauren’s diffuse type gastric cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2020 Oct 1;10(1):16240. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh YY, Kuo WL, Hsu WT, Tung SY, Li C. Fusobacterium Nucleatum-Induced Tumor Mutation Burden Predicts Poor Survival of Gastric Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Dec 30;15(1):269. [CrossRef]

- Li N, Bai C, Zhao L, Sun Z, Ge Y, Li X. The Relationship Between Gut Microbiome Features and Chemotherapy Response in Gastrointestinal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:781697. [CrossRef]

- Han Z, Cheng S, Dai D, Kou Y, Zhang X, Li F, Yin X, Ji J, Zhang Z, Wang X, Zhu N, Zhang Q, Tan Y, Guo X, Shen L, Peng Z. The gut microbiome affects response of treatments in HER2-negative advanced gastric cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2023 Jul;13(7):e1312. [CrossRef]

- Si W, Liang H, Bugno J, Xu Q, Ding X, Yang K, Fu Y, Weichselbaum RR, Zhao X, Wang L. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG induces cGAS/STING- dependent type I interferon and improves response to immune checkpoint blockade. Gut. 2022 Mar;71(3):521–33. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi AM, Nabavizadeh F, Ashabi G, Halimi S, Rahimpour M, Vahedian J, Panahi M. Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus Supplementation Improved Capecitabine Protective Effect against Gastric Cancer Growth in Male BALB/c Mice. Nutrition and Cancer. 2021 Nov 26;73(10):2089–99. [CrossRef]

- Chrysostomou D, Roberts LA, Marchesi JR, Kinross JM. Gut Microbiota Modulation of Efficacy and Toxicity of Cancer Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2023 Feb;164(2):198–213. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, He P, Liu Y, Qi M, Dong W. Combining Sodium Butyrate With Cisplatin Increases the Apoptosis of Gastric Cancer In Vivo and In Vitro via the Mitochondrial Apoptosis Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Aug 27;12:708093. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).