1. Introduction

Older adults are defined as individuals aged 65 years or older who experience a decline in both physical and cognitive functions, making it difficult for them to perform daily activities and occupational tasks effectively [

1]. Most older adults experience physical frailty, leading to impaired balance, reduced agility, and decreased gait stability [

2], which are significant contributing factors to falls in this population [

3]. Falls often result in physical injuries such as fractures, sprains, and contusions, as well as psychological consequences, including fear of recurrent falls. Among these, older adults who sustain hip fractures due to falls frequently require hip arthroplasty as part of their medical intervention [

4,

5].

Hip arthroplasty is a surgical intervention performed to restore normal joint function in cases where the hip joint has been severely compromised due to conditions such as femoral head necrosis or osteoarthritis, or as a result of fractures caused by trauma, including falls [

6]. This procedure involves the removal of the damaged portion of the hip joint and its replacement with an artificial implant to restore its range of motion and functional capacity [

7]. However, hip arthroplasty is a major surgical procedure that can impose significant physical and psychological stress on patients, many of whom perceive the operation as a serious and daunting intervention [

8]. Postoperatively, patients often experience discomfort and anxiety due to pain and the necessity of adhering to positional restrictions aimed at preventing hip dislocation [

9]. Moreover, hospitalised patients may encounter complex psychological challenges, including fear of the unfamiliar hospital environment, a sense of isolation, and feelings of loss, which may further contribute to the deterioration of their overall health status [

10].

Furthermore, older adults who have experienced a fall may impose self-imposed limitations on their functional abilities due to the fear of recurrent falls, leading to a reduction in physical activity. This behavioural change can ultimately result in further deterioration of their physical function [

4,

11]. In addition, falls can trigger psychological issues such as fear and depression [

12]. Among older adults who have sustained fractures due to falls, these psychological challenges are often exacerbated compared to those who have not experienced a fracture, highlighting the heightened emotional distress associated with fall-related injuries.

Existing research on hip arthroplasty in older adults has predominantly focused on rehabilitation interventions, nursing care, post-surgical complications, and the psychological burden on caregivers [

3,

6]. While these studies are essential for facilitating the reintegration of older adults into daily life following hip arthroplasty, they may not fully address the psychological distress and challenges associated with post-operative movement restrictions, pain, unfamiliar environments, and potential trauma from the fall itself. Given these factors, it is crucial to develop practical interventions aimed at restoring both the physical and psychological well-being of older adults undergoing hip arthroplasty, enabling them to regain functional independence and resume daily activities. However, qualitative research exploring the lived experiences and psychological adaptations of older adults who have undergone hip arthroplasty due to fall-related fractures remains limited. Therefore, this study aims to qualitatively examine the changes in daily life and the physical and psychological transitions experienced by older adults following hip arthroplasty due to falls. The findings will serve as foundational data for the development of occupational therapy interventions tailored to this population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employs a qualitative case study approach to explore the physical, psychological, and daily life changes experienced by older adults (aged 65 and above) following hip arthroplasty due to fall-related fractures. A case study methodology is particularly suitable for examining the dynamic manifestation of phenomena, their process of change, specific details, and contextual factors at a given point in time [

13,

14]. Furthermore, this study aligns with an instrumental case study approach, as it aims to utilise participants' experiences as foundational data for the development of future intervention programmes. This study was registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS), Republic of Korea, which is a WHO-recognised primary registry. The registration number is KCT0010429.

2.2. Participants

The participants in this study were seven older adults who had undergone hip arthroplasty due to fall-related fractures and were hospitalised at I Rehabilitation Hospital, a recovery-phase rehabilitation facility located in Cheongju, South Korea. Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling method. During the recruitment process, individuals younger than 65 years of age and those who had undergone hip arthroplasty for reasons other than fall-related fractures were excluded.

To ensure that participants could provide rich narratives of their experiences, only individuals with a Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Korean version (MoCA-K) score of 23 or higher and the ability to communicate effectively with the researcher were included. Additionally, to derive comprehensive research findings, the sample was structured to ensure a diverse distribution in terms of participants' ages and the frequency of their past fall experiences.

2.3. Data Collection

Prior to conducting this study, ethical approval was obtained from the Cheongju University Institutional Review Board (Approval No: 1041107-202412-HR-046-01). Before collecting data, the researchers thoroughly explained the study’s purpose and methodology to the participants and obtained their informed consent. Participants were also informed that they could withdraw from the interview at any time if they felt uncomfortable or unwilling to continue. All collected data were anonymised to ensure confidentiality.

Data collection was conducted through individual interviews with participants from February to March 2025. Interviews were scheduled on weekdays, after participants had completed their hospital treatment sessions and evening meals. To ensure that participants could express their negative experiences freely without external pressure, interviews were conducted in a private, soundproofed room, preventing interference from other patients or healthcare providers.

The interview questions were developed in a semi-structured format, balancing systematic questioning with natural conversational flow. The question framework was informed by previous qualitative studies on hip fractures and fall experiences among older adults [

15,

16]. Additionally, the question categories proposed by Kruger and Casey (2000) (i.e., opening, introductory, transition, key, and closing questions) were incorporated [

17]. The content of the questions was also structured based on the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, 4th Edition (OTPF-4), ensuring relevance to the domains of occupational performance. The final questionnaire was developed under the supervision of a senior occupational therapy professor with extensive experience in qualitative research.

To validate the questions, a pilot interview was conducted with one older adult who had undergone hip arthroplasty, allowing the researchers to refine the questionnaire as needed. The finalised set of interview questions is presented in

Table 1.

Before starting each interview, participants provided consent for audio recording, which was conducted using a mobile recording device. Recorded data were transcribed as soon as possible after the interviews. Additionally, researchers documented non-verbal expressions such as tone, gestures, and facial expressions during participants’ responses. They also took reflective notes on emerging thoughts and questions throughout the interview process. Each interview lasted approximately 60 minutes per participant.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were analysed using Krippendorff’s (2003) content analysis procedure, following a structured three-step process [

18]. Firstly, the researchers engaged in an in-depth familiarisation phase, repeatedly reading the transcribed interview records and audio recordings to comprehend the impact of participants' experiences. Secondly, meaningful statements were identified. The researchers transformed participants' verbal expressions into written statements, extracting key phrases to construct meaning. Thirdly, a categorisation process was conducted, where identified meaningful statements were conceptualised and grouped into categories based on their relationships and similarities.

2.5. Ensuring Research Rigor

To ensure the rigor of this qualitative study, the researchers adhered to the four criteria of trustworthiness—credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability—as proposed by Guba & Lincoln (1989) [

19]. Firstly, to enhance credibility, member checking was employed. After each interview, a brief summary of the discussion was presented to the participant for confirmation. Additionally, transcribed data were reviewed multiple times, and any ambiguous statements were clarified with participants to ensure accuracy. Secondly, transferability was strengthened by ensuring a diverse participant selection process. Participants were recruited with consideration of their general characteristics, allowing for the collection of rich and in-depth data that could be applicable to a broader population. Thirdly, to maintain dependability, the entire research process, including the interview framework and study methodology, was thoroughly reviewed by an occupational therapist with over four years of clinical experience in treating hip arthroplasty patients and a peer researcher specialising in related fields. Finally, to uphold confirmability, the researchers made a conscious effort to eliminate personal biases during data analysis. The categorised data were reviewed multiple times to ensure that interpretations remained objective and reflective of the participants' actual experiences.

3. Results

A total of seven patients participated in this study, and the general characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 2. Data collected through interviews were analysed through constant comparison, categorisation, and reorganisation. The key themes relating to the experiences of older adults who underwent total hip replacement surgery due to fall-induced fractures were classified into three major categories, seven subcategories, and 21 meaning units (

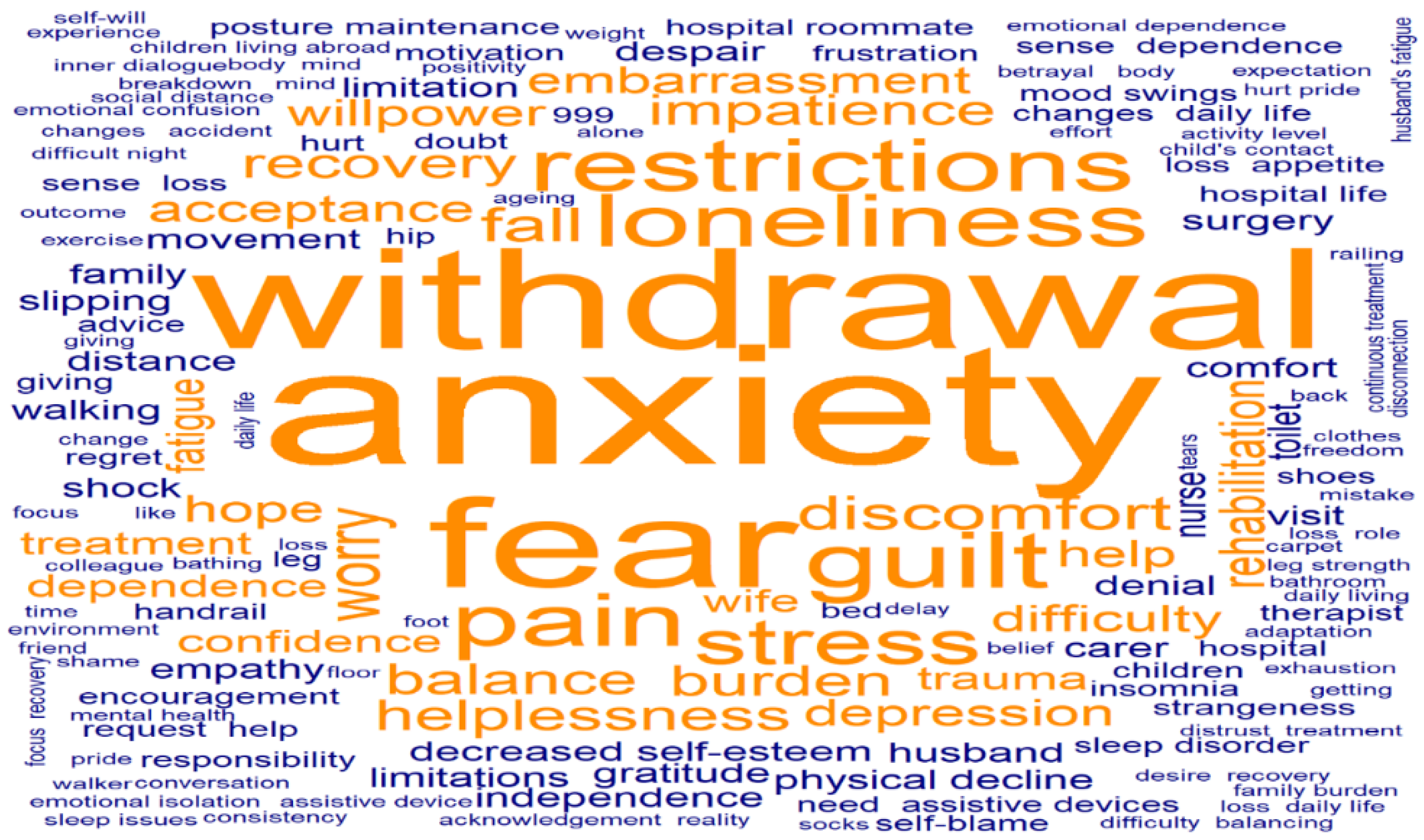

Table 3). In addition, to visualise the most frequently used words from participants’ responses, a Word Cloud was generated using R version 4.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) (

Figure 1).

3.1. Psychological Changes Following Surgery

3.1.1. Feelings of Helplessness, Loss of Self-Esteem, and Denial of Reality at the Time of the Fall

Participants experienced a profound sense of helplessness when they realised they could not move their bodies at the moment of the fall. Some also exhibited a tendency to deny reality, struggling to accept the fact that they had sustained a serious injury. It was particularly evident that participants who had previously been in good physical health found it more difficult to come to terms with the fact that they had experienced a fall.

"I never thought I was someone who would fall… But when I did, I tried to move my leg, and I just couldn’t. I touched it (referring to the operated leg), but there was no response… At that moment, my mind went blank. I thought, ‘This is it. It’s over.’"

(Participant 1)

"At first, I thought, ‘This is nothing, I just need some rest.’ I tried to hold out and avoid going to the hospital. But as time passed, the pain became unbearable, and in the end, I had no choice but to call 119 (emergency services)."

(Participant 4)

"To be honest, I still can’t accept it. Acknowledging that my body is not the same as before… That’s the hardest part."

(Participant 2)

3.1.2. Frustration and Anxiety During the Rehabilitation Process

Participants reported experiencing frustration during their initial rehabilitation sessions, particularly as they struggled with pain and the inability to control their movements as they had before. Some participants also exhibited resistance to rehabilitation, as they found it difficult to accept their physical limitations and the need for therapy.

"On the first day of rehabilitation, the therapist asked me to lift my leg, but it just wouldn’t move properly. I kept telling myself, ‘I need to move it,’ but every time I tried, the pain was too much, and I just couldn’t put in the effort."

(Participant 1)

"I have always been an active person who enjoys exercise. I never thought an injury like this would happen to me. It really hurt my pride… That’s why I didn’t even want to go through rehabilitation at first."

(Participant 3)

3.1.3. Anxiety and Realisation Regarding Slower-than-Expected Recovery

Participants initially expected that their bodies would naturally recover after a certain period following surgery. However, upon realising that their recovery was progressing more slowly than anticipated, they experienced psychological distress. Nevertheless, some participants adopted a positive mindset, recognising the need for active engagement in rehabilitation to facilitate their recovery.

"I thought I just needed to endure a little pain and I’d recover quickly. But when I actually started rehabilitation, I realised it wasn’t easy at all. My mind became overwhelmed with all these thoughts."

(Participant 7)

"I assumed that after surgery, time alone would heal me. But as I continued with my treatment, I came to understand—this isn’t something that just gets better on its own… I have to put in the effort myself."

(Participant 7)

(Sighing) "When you go through treatment, you expect to see improvement… but honestly, I feel like it’s getting harder instead. I haven’t been feeling great lately, and I’m really worried about what’s ahead. Even practising walking is incredibly painful and exhausting."

(Participant 5)

3.2. Changes in Social Relationships

3.2.1. Social Isolation During Hospitalisation

Participants reported experiencing increasing social isolation as their contact with existing social networks diminished during their hospitalisation. This isolation contributed to heightened feelings of depression and loneliness. On the other hand, some participants found emotional solace in interacting with other patients who were undergoing similar experiences.

"At first, my friends would contact me frequently, but now it’s become quieter. Since I’m in the hospital, I can’t go and meet them myself, so I just feel naturally distant from them."

(Participant 4)

"During the day, I’m okay, but at night, the hospital room becomes so quiet. After visiting hours, when my family leaves, it feels like the space around me suddenly gets bigger… and I feel this strange sense of loneliness."

(Participant 5)

"Even so, talking with other patients in the same situation made me feel a bit better. It made me realise I’m not the only one going through this, and we all seem to have similar thoughts."

(Participant 7)

3.2.2. The Emotional Burden of Dependency on Others

Participants expressed that relying on others for physical assistance, whether it be caregivers, nurses, or family members, was a significant psychological burden. This was particularly evident among those who had lived independently throughout their lives, as they reported experiencing heightened discomfort and distress in receiving care from others. Additionally, participants who were cared for by their spouses described feeling like a burden, especially when they noticed signs of exhaustion in their partner.

"I have never liked asking anyone for help. I’ve always handled everything on my own. But now, I have to ask for assistance just to go to the bathroom… even dressing and showering require someone else’s help. It’s frustrating and difficult."

(Participant 3)

"My wife is looking after me, but every time she seems tired, I feel uneasy. I keep thinking… I need to recover quickly and walk properly again."

(Participant 2)

3.3. Life After Discharge and the Process of Adaptation

3.3.1. Intense Anxiety About Experiencing Another Fall at Home

As they approached discharge, most participants expressed a deep fear of falling again. Many were particularly anxious about experiencing another fall in the same location where their initial injury occurred. In response, participants adjusted their movement patterns and adopted more cautious behaviours to prevent falls. Additionally, some participants were concerned about being discharged while their physical function was still not fully restored.

"I fell while getting out of bed, so I keep worrying that it will happen again. I plan to keep a small light next to my bed and make sure I never move around recklessly at night."

(Participant 4)

"When I go to the bathroom alone in the hospital, I always look at the floor before taking a step. If there’s something to hold onto, I grab it before moving. I can’t just walk freely like I used to."

(Participant 1)

"I’m still struggling to walk… and yet, I already have to think about leaving the hospital. It feels overwhelming. If I could at least walk properly with a cane, I think I’d feel more confident about going home."

(Participant 5)

3.3.2. Recognising the Need to Modify the Home Environment to Prevent Falls

Participants strongly recognised the importance of creating a safer home environment to prevent future falls. In particular, there was an increased awareness of the need to implement fall prevention measures around areas such as bathrooms and bedsides, including installing handrails and using non-slip mats.

"When I get home, I plan to put a non-slip mat in the bathroom. It’s fine here in the hospital, but at home, my bathroom floor is quite slippery."

(Participant 2)

"I need to be extra careful when getting out of bed, so I’m thinking of installing handrails or some kind of support near my bed. Sometimes when I get up, I feel dizzy, so I need to take precautions."

(Participant 6)

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to qualitatively analyse the physical and psychological changes experienced by older adults following hip arthroplasty due to fall-related fractures. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with seven participants, and the collected data were analysed. The findings were categorised into three main themes, seven sub-themes, and 21 meaning units. The discussion of these findings is as follows.

Participants in this study experienced psychological changes following surgery, including loss of self-esteem, denial of reality, frustration, and anxiety. Notably, those who had previously been physically active and highly independent in daily activities exhibited a stronger tendency towards denial and depression. However, previous studies on falls among older adults have suggested that fall experiences can sometimes lead to positive psychological changes [

15]. For instance, participants in these studies demonstrated increased caution in physical activities, the adoption of fall prevention habits, and a greater commitment to maintaining their health, all of which contributed to a positive behavioural shift. In contrast, the participants in this study exhibited greater psychological withdrawal and intensified negative emotions rather than experiencing such adaptive changes. This discrepancy can be attributed to the severity of their injuries, as they did not simply experience a fall, but sustained serious hip fractures requiring major surgical intervention in the form of hip arthroplasty. These findings align with existing research, which indicates that the greater the physical damage following a fall, the more pronounced the psychological distress, leading to prolonged anxiety and depression [

16].

Additionally, participants in this study anticipated a swift recovery and return to daily life following surgery. However, as they progressed through rehabilitation, they encountered slower-than-expected recovery and persistent pain, which led to feelings of frustration and anxiety. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that persistent pain following hip arthroplasty can contribute to feelings of self-doubt, anxiety, and depression, ultimately having a negative impact on the overall recovery process [

20]. Furthermore, a prolonged recovery period can diminish patients' motivation to engage in rehabilitation, increasing the likelihood of helplessness and resignation rather than active participation in therapy [

21]. In this study, some participants exhibited resistance towards rehabilitation or demonstrated a passive attitude, suggesting that such psychological barriers may not only hinder physical recovery but also delay reintegration into daily life.

Furthermore, this study identified that the need to rely on others for assistance placed a psychological burden on participants. This was particularly evident among those who were cared for by their spouse or had previously led highly independent lives, as they reported experiencing discomfort and a sense of helplessness when receiving care. These findings align with previous research suggesting that older adults who have lived independently may experience significant psychological distress when faced with a loss of autonomy due to declining physical function [

22]. Therefore, it is essential to implement counselling and emotional support programmes during hospitalisation to help patients accept their reality, alleviate psychological stress, and enhance motivation for active participation in rehabilitation.

Participants in this study experienced psychological isolation as their existing social relationships weakened during hospitalisation. While family members and acquaintances initially maintained frequent contact and visits, these interactions gradually declined over time, leading participants to feel socially excluded. These findings are consistent with previous research, which suggests that the longer older adults remain hospitalised, the more socially isolated they become, increasing psychological stress and emotional distress [

23]. This highlights the crucial role of social support in both psychological well-being and physical recovery [

24]. Notably, some participants in this study found emotional comfort through interactions with fellow patients in similar situations, expressing a sense of relief in realising,

"I am not the only one going through this." Such findings indicate that emotional exchanges with peers during rehabilitation can foster positive psychological changes. Therefore, it may be beneficial to incorporate group-based therapeutic approaches in rehabilitation programmes to enhance social support and emotional well-being.

Finally, as participants approached discharge, they expressed anxiety about experiencing another fall in the same location where their initial injury occurred. Additionally, some were concerned about being discharged before their physical function had fully recovered. In response, participants exhibited a heightened sense of caution in their movements and recognised the need to modify their home environment to prevent future falls. Previous studies have also identified the fear of recurrent falls as one of the most significant concerns among fall survivors [

25], as this fear has been shown to contribute to increased psychological distress [

26]. Therefore, to ensure that patients can transition smoothly into daily life without excessive anxiety about future falls, it is crucial to provide individualised counselling and facilitate the appropriate use and installation of assistive equipment at home, similar to those used in the hospital setting.

Older adults who undergo hip arthroplasty due to fall-related fractures are more likely to experience stronger negative emotions compared to those who have experienced a general fall or undergone hip arthroplasty for degenerative joint conditions. These heightened psychological distress factors can lead to reduced engagement in rehabilitation therapy, potentially delaying both physical recovery and reintegration into daily life. This study underscores the importance of incorporating psychological recovery into rehabilitation goals, rather than focusing solely on physical restoration. It is essential to foster communication among hospitalised patients and develop post-discharge support programmes to enhance long-term recovery outcomes.

However, this study has several limitations. First, as the study was conducted with patients from a single hospital, the findings cannot be generalised to a broader population. Second, the study did not take into account the frequency of participants' past fall experiences. Third, key factors influencing falls, such as gait ability, balance, and muscle strength, were not examined. Therefore, future research should address these limitations to further enhance the understanding of the experiences of older adults undergoing hip arthroplasty due to fall-related fractures.

5. Conclusions

This study conducted an in-depth exploration of the daily life changes experienced by older adults following hip arthroplasty due to fall-related fractures, using a case study approach. The findings revealed that older adults experienced negative emotions and social isolation after surgery. Additionally, some participants exhibited a lack of awareness regarding safety concerns post-discharge. This study is significant in that, unlike previous research primarily focused on the physical recovery of hip arthroplasty patients, it provides insight into patients’ emotional states following surgery. Therefore, future research should focus on developing intervention programmes aimed at enhancing emotional support and alleviating psychological distress among patients undergoing hip arthroplasty. Furthermore, studies evaluating the effectiveness of such interventions would be valuable in advancing comprehensive rehabilitation strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1. Interview session details including dates, duration, and setting of each participant’s interview. Table S2. General demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants. Table S3. Categorisation of qualitative results based on thematic content analysis. Figure S1. Word cloud visualisation highlighting the most frequent terms extracted from interview transcripts. SRQR File: SRQR (Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research) checklist completed for this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M.Y. and J.H.P.; Methodology, Y.M.Y.; Investigation, Y.M.Y.; Formal Analysis, Y.M.Y. and B.S.W.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Y.M.Y. and B.S.W.; Writing – Review & Editing, J.H.P. and B.S.W.; Supervision, J.H.P.; Project Administration, J.H.P.

Funding

This Research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Cheongju University (approval number: 1041107-202412-HR-046-01).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants for the inclusion of anonymized interview excerpts in the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all those who provided support and encouragement during this study. No external funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kim BJ, Choi S, N. A Narrative Inquiry into the Experience of Art Therapists in Group Art Therapy with the Elderly. Korean Society of Gerontological Social Welfare. 2024;79(3):211-40. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y, Yoon H, Yoon H. Kinds of informal social networks and life satisfaction: difference between young-old and old-old Eldery. Korean J Reg Sociol. 2019;20:129-55. [CrossRef]

- Park EY, Choi H-R. Analysis of risk factors for complication after hip fracture surgery in the elderly according to geriatric interdisciplinary team care and orthopedic care. Journal of Korean Biological Nursing Science. 2016;18(4):193-202. [CrossRef]

- Lee S-G, Kim H-J. Factors influencing the fear of falling in elderly in rural communities. Journal of agricultural medicine and community health. 2011;36(4):251-63. [CrossRef]

- Jeon E, Son J, Kim N. A Systematic Literature Review on Rehabilitation Nursing for Elderly Patients with Total Hip Arthroplasty. The Korean Journal of Rehabilitation Nursing. 2023;26(2):66-76. [CrossRef]

- Knight SR, Aujla R, Biswas SP. Total Hip Arthroplasty-over 100 years of operative history. Orthopedic reviews. 2011;3(2):e16. [CrossRef]

- Kim BA, Kim JY, Kim SY, Lee GE. The Study on the Cognitive Function of the Elderly Patients with Total Hip Arthroplasty: A comparison between female elderly and male elderly. PNU Journals of Women's Studies. 2017;27(3):231-55. [CrossRef]

- Ryu SH, Jo HS. Effect of real patient controlled analgesia (PCA) education with practice on postoperative pain, consumption of analgesics, and anxiety for elderly patients with total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Korean Clinical Nursing Research. 2016;22(2):152-60. [CrossRef]

- Moon S, Kim K. Review of postoperative rehabilitation and exercise for total knee and hip arthroplasty cases in Germany. The Korean Journal of Growth and Development. 2015;23(1):1-7. Available from: https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART001968321.

- Yoo S. Analysis of research trends about hospitalization stress. The Korean journal of stress research. 2015;23:49-61. [CrossRef]

- Scheffer AC, Schuurmans MJ, Van Dijk N, Van Der Hooft T, De Rooij SE. Fear of falling: measurement strategy, prevalence, risk factors and consequences among older persons. Age and ageing. 2008;37(1):19-24. [CrossRef]

- Nam I, Yoon H. An analysis of the interrelationship between depression and falls in Korean older people. J Korea Gerontol Soc. 2014;34:523-37. Available from: https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART001904251.

- Yin RK. Case study research: Design and methods: sage; 2009.

- Cresswell JW. Research design, qualitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Inc DOI. 2003;10(08941939.2012):723954.

- Shin K, Kang Y, Jung D, Park H, Eom J, Yun E, et al. Experiences among older adults who have fallen. Qualitative Research. 2010;11(1):26-35. Available from: https://www.riss.kr/link?id=A82459485.

- Kim GY. The relationship between the mental health and falling experience an elderly: Graduate School of Chosun University; 2018. Available from: https://www.riss.kr/link?id=T15050031.

- Kruger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups-A practical guide for applied research (3rd ed.): Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.; 2000.

- Giannantonio CM. Book Review: Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;13(2):392-4.

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Fourth generation evaluation: Sage; 1989.

- Xu L, Chong HJ. A Review of Music Intervention Fidelity for the Pain Alleviation after Joint Replacement Surgery. Journal of Naturopathy. 2023;12(2):77-84. [CrossRef]

- Flanigan DC, Everhart JS, Glassman AH. Psychological factors affecting rehabilitation and outcomes following elective orthopaedic surgery. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2015;23(9):563-70. [CrossRef]

- Albanese AM, Bartz-Overman C, Parikh M, Toral, Thielke SM. Associations between activities of daily living independence and mental health status among medicare managed care patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020;68(6):1301-6. [CrossRef]

- Jeong H, Kwon S, Jung YJ. Hospital life experience of older patients hospitalized for a long time in long-term care hospitals without visitors: A phenomenological study. Journal of Korean Gerontological Nursing. 2024;26(2):191-202. [CrossRef]

- CHOI H-J, CHANG H-K. Psychosocial Factors Affecting Post-acute Stroke Patients’ Rehabilitation Adherence. Korean Journal of Rehabilitation Nursing. 2022:49-60. [CrossRef]

- Kim YJ. Nurses' experience of inpatients' falls. Journal of Korean Academy of Fundamentals of Nursing. 2017;24(2):106-17. [CrossRef]

- Jung D-Y, Shin K-R, Kang Y-H, Kang J-S, Kim K-H. A study on the falls, fear of falling, depression, and perceived health status among the older adults. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing. 2008;20(1):91-101. Available from: https://www.riss.kr/link?id=A99897846.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).