1. Introduction

Medical image segmentation is the mainstay of computer-aided diagnostic systems and is becoming increasingly relevant to the quantitative assessment of both anatomical structures and pathological tissues. Despite the great advances made with deep learning approaches, an ever-elusive problem exists: the inherent ambiguity at the boundaries between pathological and healthy tissues across various medical imaging modalities. The ambiguous boundary issue is critical, since it makes reliable and accurate segmentation a challenge in scenarios where accurate boundary delineation is vital to patient outcomes. The complexity of this challenge is particularly evident across different imaging modalities. In dermatologic imaging, accurate segmentation of skin lesions is paramount for early detection of cancer; however, lesions, according to gross histological comparison, often show considerable variability in appearance and subtle, gradual transition to surrounding healthy tissue. Similarly, polyp detection during colonoscopy is complicated by the fact that intricate tissue textural variations, along with little contrast at lesion boundaries, have direct implications for colorectal cancer prevention. Segmentation of kidney glomeruli in pathology images further illustrates the problem of boundary ambiguity. Subtle contrast changes between diseased and healthy tissues pose significant difficulties for coming up with a correct boundary delineation, thereby compromising diagnostic accuracies and resulting in the likely scenarios of misdiagnosis. Recent studies have tried to overcome this boundary ambiguity by development of innovative methodological solutions. For example, the Simple Generic Method (Kim & Lee, 2021) [

1] introduced a boundary-aware loss function which attempts to assign higher weights to boundary pixels; however, this methodology is held back by the absence of dedicated structures for boundary feature extraction. AEC-Net (Wang et al., 2020) [

2] has a dual-branch structure with attention mechanisms under the constraint of edges. The simplified edge branch fails to make a firm decision in complex boundary regions. SharpContour (Zhu et al., 2022) [

3], however, pushes onto this approach with contour-based optimization and bottom-up feature fusion, but again performs poorly with tissues that have textured edges or ambiguously textured edges. These results give a strong message that extraction of boundary features may not guarantee satisfactory segmentation in medical imaging. In parallel with these boundary-focused methods, significant advances have been achieved in COD, a technique developed originally to detect hidden objects in natural scenes (Fan et al., 2022) [

4]. COD has been applied to the medical domain and has provided some very promising initial results, as shown recently by Ji et al. These include DGNet (Ji et al., 2023) [

5] and ERRNet (Ji et al., 2022) [

6], which qualified as effective methods to segment images of polyps and pneumonia through a smooth fusion of context and edge information. Nevertheless, a quantitative assessment shows that these techniques are not as successful in the specific context of medical images featuring ambiguous boundaries as they are with natural images; this indicates the need for domain-centric adaptations. This necessitated the need for us to build upon both boundary extraction techniques and the advancements in COD to come up with a new boundary extraction module that uses the strengths of both approaches toward better boundary feature extraction in COD models to allow for more accurate segmentation in very ambiguous or poorly defined regions.

The contributions of our work are summarized as follows:

(1) We propose FTEM, a novel solution to address ambiguous boundary delineation in medical images. Unlike spatial domain methods that fail to capture subtle edges under low contrast conditions, FTEM uses Fourier transforms to decompose features into spectral components. Through block-wise frequency processing and soft-threshold adaptive token mixing (λ=0.01), FTEM selectively enhances boundary-related high-frequency signals while suppressing noise.

(2) Building on COD, we design FEA-Net, an advanced framework that integrates spectral analysis and adaptive attention. FEA-Net first generates initial edges through the spatial-channel self-attention of SEEM, and then refines them through FTEM’s spectral decomposition. AEFM further enhances edge granularity through channel-wise calibration, while CAAM aggregates multi-scale context. This cascaded design outperforms existing COD models (e.g., +2.4% mIoU over BiRefNet), demonstrating clinical feasibility for early diagnosis.

2. Related Work

Medical image segmentation has made remarkable progress in recent years. Early CNN-based techniques laid the foundation for such developments, with PSPNet introduced by (Zhao et al., 2017) [

7]. It incorporated a pyramid pooling module for aggregating multi-scale contextual information by hierarchical pooling operations. Subsequently, (Azad et al., 2020) [

8] developed DeepLabV3+, an innovatively integrated Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling with Depth-Separable Convolution for much better boundary delineation capabilities. In the light of medical imaging, different adaptations from the U-net architecture gradually becoming leading solutions. (Zhou et al., 2020) [

9] introduced UNet++, which utilizes dense skip connections to harmonize the semantic gap between features from the decoder and those from the encoder. By extension, (Qin et al., 2022) [

10] proposed UNet3+, in which both deep attention and dense skip connections can flexibly allow the generation of more complicated segmentations. Additionally, the introduction of attention mechanisms by (Oktay et al., 2018) [

11] permitted models to focus on the most salient spatial regions while effectively suppressing potentially irrelevant features. Transformer-based architecture has made remarkable strides in medical image segmentation with the advancement of deep learning. Chen et al.(Chen et al., 2024) [

12] fused the FCN and transformer architectures to capture fine-grained spatial details and long-range dependencies simultaneously. (Cao et al., 2022) [

13] introduced a shifted window that works on a self-attention basis and demonstrated effective hierarchical feature learning. Also, (Xie et al., 2021) [

14] proposed a novel hierarchical transformer encoder with a lightweight all-MLP decoder. These mainstream approaches, however, are still unable to adequately handle the problem of boundary ambiguity in medical images, leading to unsatisfactory performance in regions with highly ambiguous boundaries.

In response to this challenge, various targeted approaches have emerged. For instance, (Lee et al., 2023) [

15] proposed a boundary-aware framework, yet this demands extensive empirical parameter tuning, while there is limited effectiveness in cases of highly ambiguous boundaries. (Wang et al., 2023) [

16] developed XBound-Former, which integrates three boundary learners for multiscale boundary detection. However, detecting key points in regions with highly ambiguous boundaries remains a challenge, which can affect the accuracy of lesion segmentation. Recent research includes the implantation of COD, an approach that aims to individually detect hidden targets in real scenes, to resolve boundary ambiguity in medical images. (Pang et al., 2022) [

17] detected minute features and improved segmentation accuracy, while (Mei et al., 2022) [

18] improved performance with an integrated scheme of global localization with local focus modules. (Sun et al., 2022) [

19] later improved COD techniques by introducing edge semantic learning. The work of (Zheng et al., 2024) [

20] attempts efficient edge refinement with bidirectional feature interaction at the core of the task. However, further optimization of edge extraction techniques in COD models towards medical image segmentation is an increasing necessity to solve unique problems in medical imaging.

In closing, recent studies indicate that there is an imperative need for novel architectures that are capable of accurate boundary delineation in medical images, especially in that scope characterized by high boundary ambiguity. Such architecture must address in a robust way the peculiar clinical situations of medical imaging.

3. Methodologies

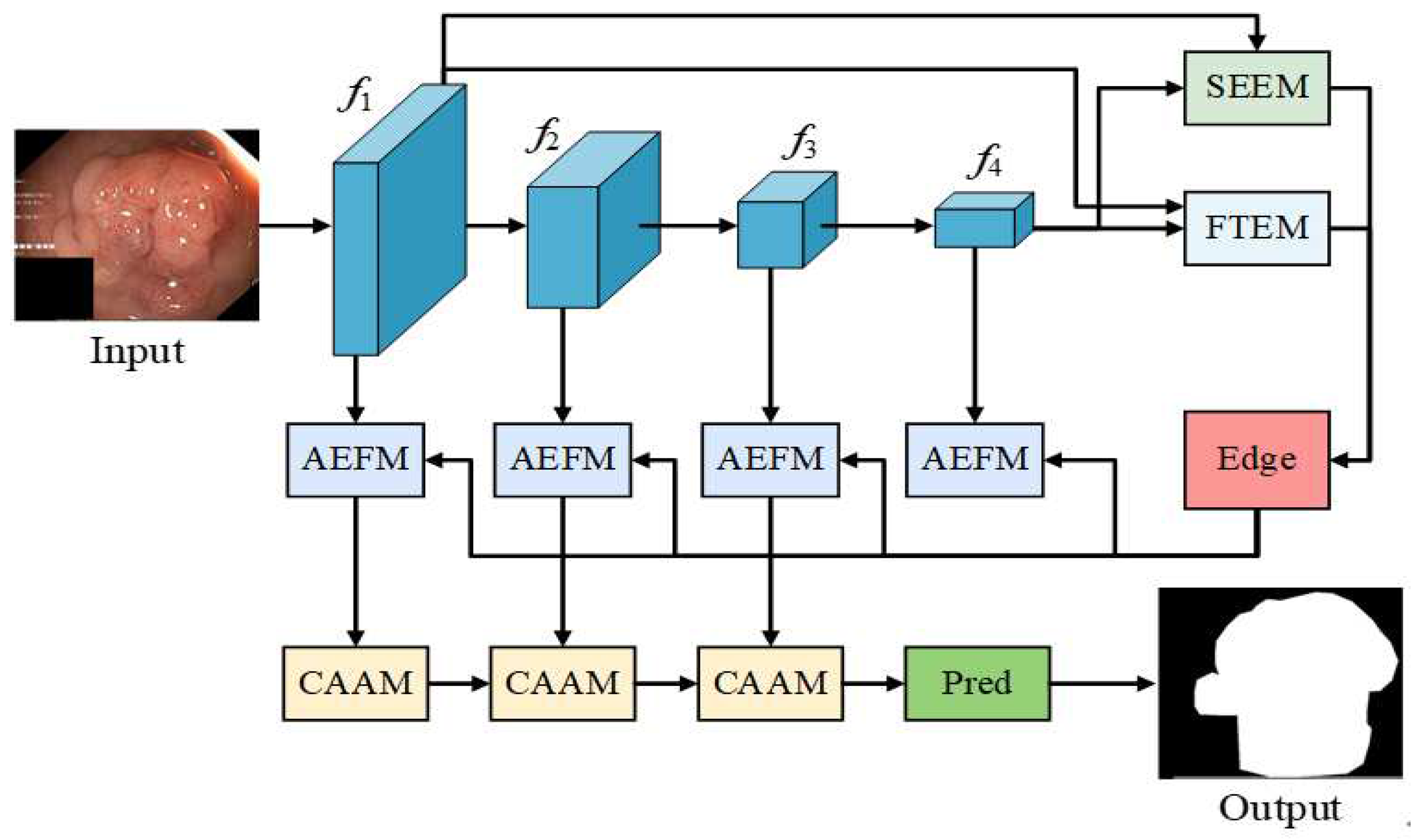

FEA-Net is a novel framework for medical image segmentation with precise boundary delineation, as shown in

Figure 1. This method improves on the baseline BGNet, which has limited performance when applied directly to ambiguous medical image boundaries. Our framework innovatively extends the BGNet architecture through four synergistic modules. First, the SEEM exploits spatial channel self-attention to generate initial edge features and localize salient boundaries of anatomical structures. To further refine boundary delineation, the FTEM processes edge information in the frequency domain, enabling more accurate delineation of ambiguous medical tissue interfaces through adaptive feature transformation. The edge-aware features are then processed by the AEFM, which implements fine-grained channel attention mechanisms to adaptively focus on critical boundary features. Finally, the CAAM integrates these multi-scale features through hierarchical fusion while preserving detailed boundary information. Through this progressive refinement pipeline, FEA-Net effectively captures subtle anatomical transitions and complex pathological patterns in medical images, significantly improving segmentation accuracy at tissue boundaries where traditional methods often fail and enabling accurate boundary delineation.

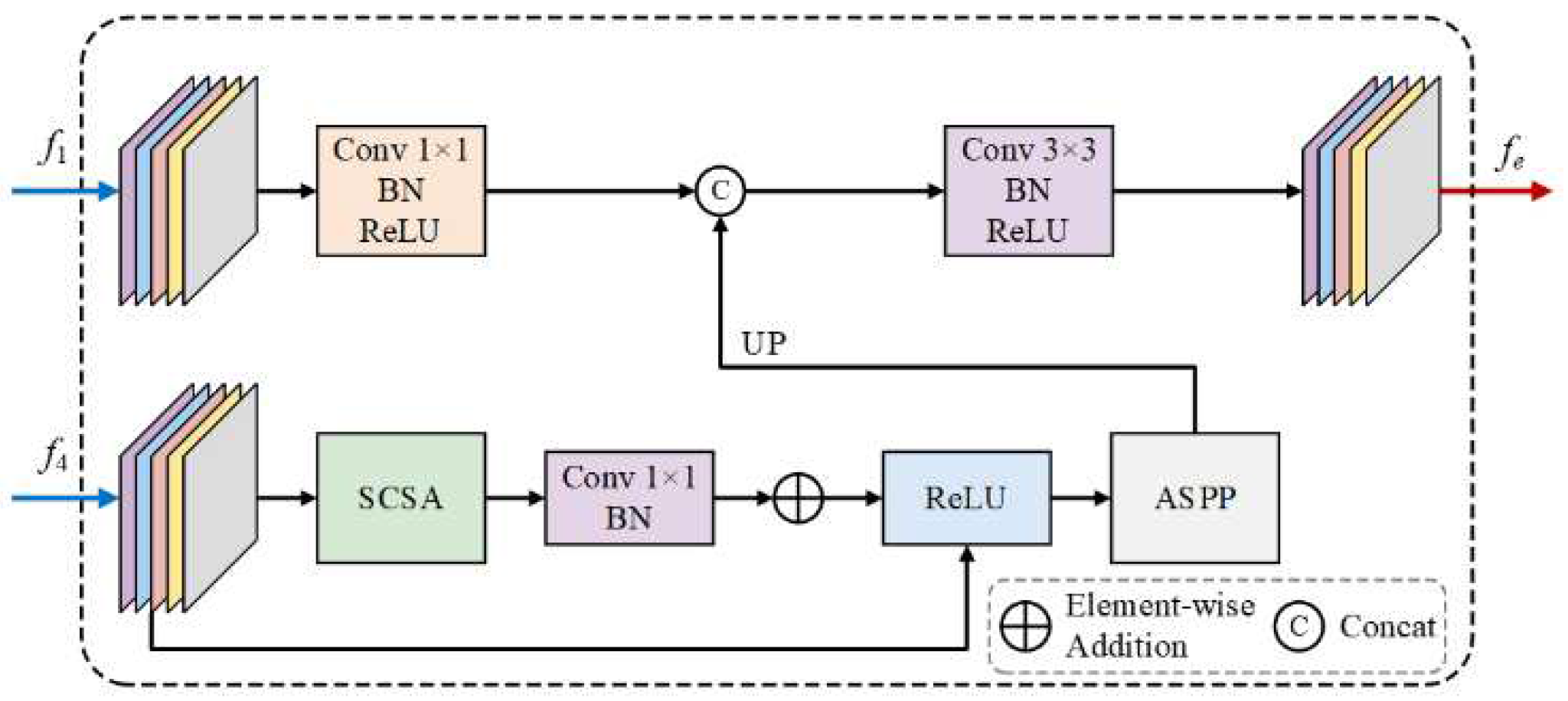

3.1. SEEM

Edge information is crucial for both segmentation and localization in medical imaging. While low-level features capture rich edge details, they often contain irrelevant non-object edges. Therefore, high-level semantic information is required to effectively extract edge features related to ambiguous medical boundaries, thus enabling more accurate segmentation and localization. In this module, we design an effective SEEM that integrates the low-level feature (

) with the high-level feature (

) to model object-related edge information. Specifically, we first reduce the channel dimensions of

to mean channels by a

convolutional layer to obtain a more compact feature representation. Then, a SCSA residual block (Si et al., 2024) [

21] is used to explore the long-range dependencies and edge-sensitive features from

, where SCSA attention with head_num=8 and window_size=8 is designed to capture edge-sensitive features through spatial channel self-attention mechanism. A residual link is added to preserve the original feature information. After attention enhancement, we use ASPP module with dilation rates [

2,

3,

6] to capture multi-scale contextual information. The multi-scale features are upsampled to match the spatial dimensions of the flat features. Finally, we integrate the multi-scale semantic features with edge details through a concatenation operation followed by ConvBNR blocks to generate edge enhanced features

. As shown in

Figure 2, SEEM effectively learns the edge semantics associated with object boundaries.

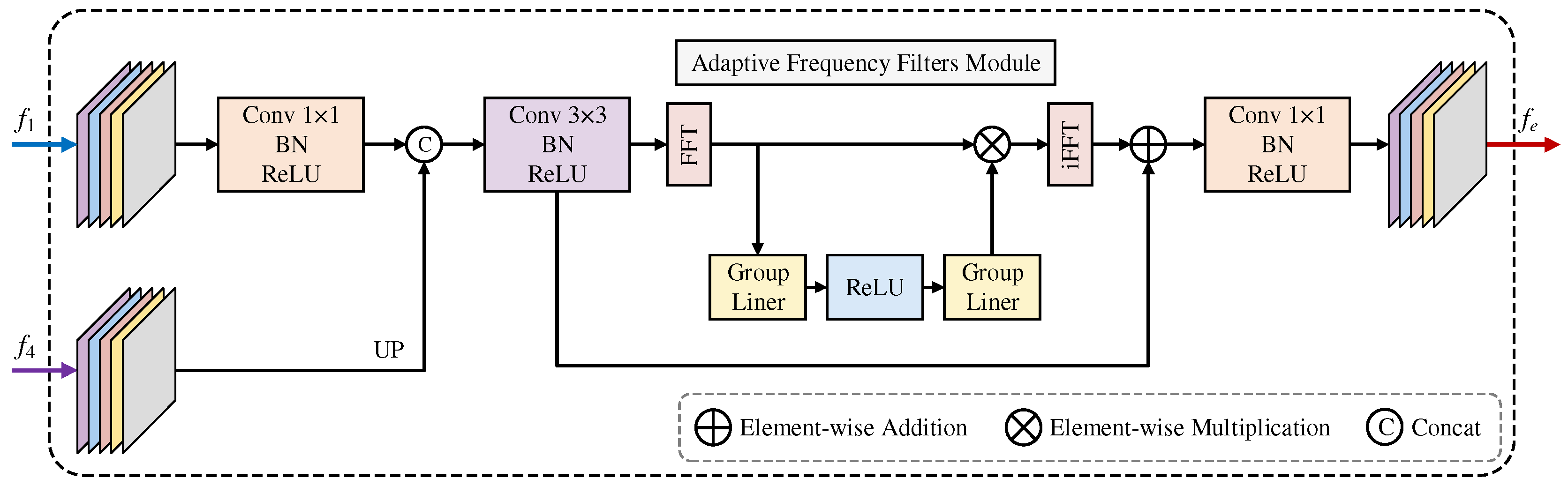

3.2. FTEM

In medical image analysis, boundary detection is particularly challenging due to inherent image blur, noise, and low contrast between anatomical structures. These boundaries often manifest as complex frequency patterns that are difficult to capture accurately in the spatial domain alone. To address this issue, we propose FTEM, which improves boundary feature extraction through frequency domain processing and adaptive frequency selection. Given input features

from backbone layer-1 and

from layer-4, FTEM first reduces their dimensions through

convolutions to obtain mid-level features. Core frequency processing is achieved by transforming the features into the Fourier domain

, where the frequency domain features undergo an efficient block diagonal transformation and adaptive frequency selection operation:

where

is the orthogonally normalized 2D Fast Fourier Transform that decomposes spatial features into frequency components,

and

are designed as

complex block-diagonal matrices of size

to achieve parameter-efficient frequency selection,

denotes ReLU activation, and

with

performs soft-thresholding to suppress noise in the frequency domain while preserving essential boundary information. The block diagonal structure ensures efficient computation by dividing the frequency channel space into

blocks. Complex transformations by

and

with their respective bias terms (

) enable selective frequency enhancement, while the residual connection preserves the original spatial details. This frequency-based process effectively captures boundary-related patterns that are difficult to detect through direct spatial domain operations. The complete architecture is illustrated in

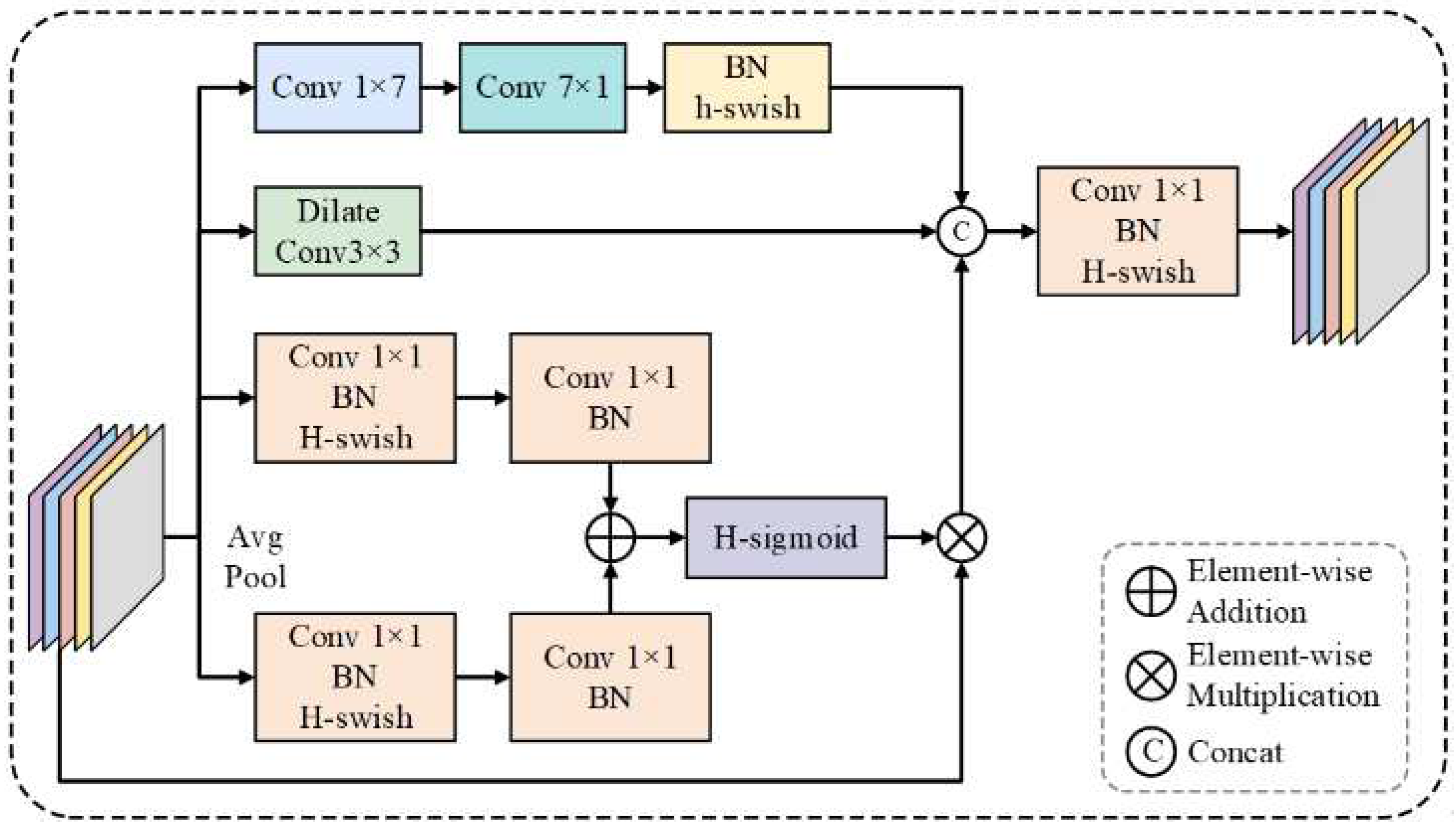

Figure 3.

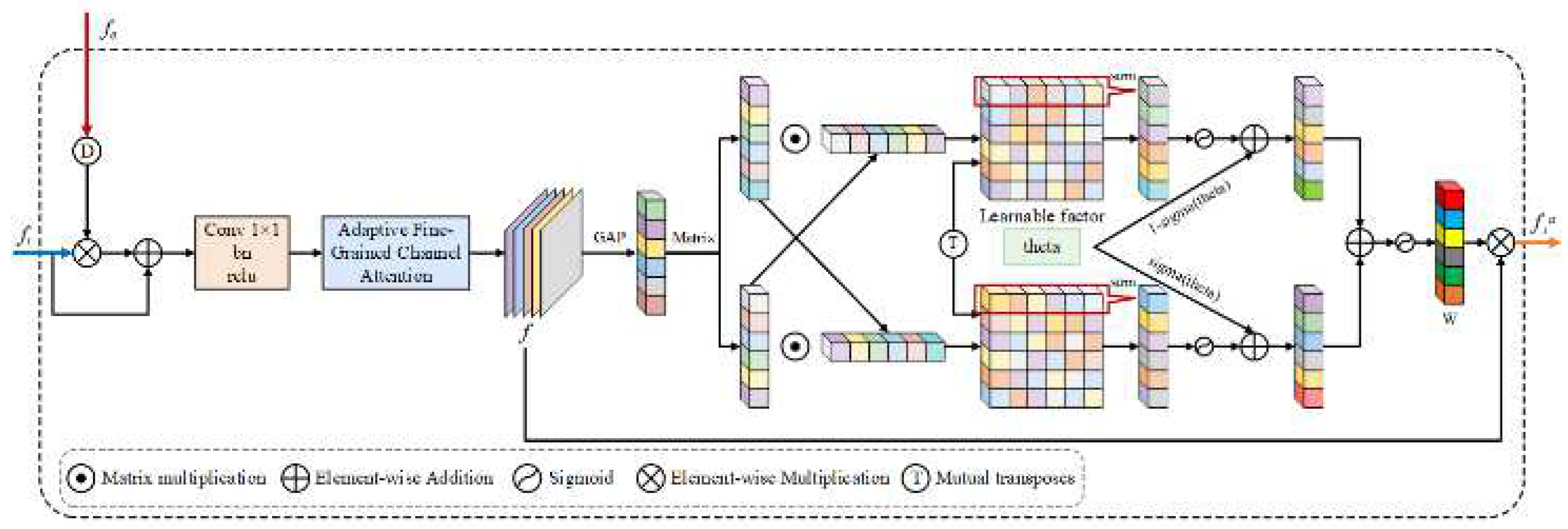

3.3. AEFM

AEFM is designed to refine the learning of boundary representations by incorporating edge-related cues into feature learning. Given the challenges of boundary ambiguity and structural inconsistencies in medical images, AEFM adaptively improves feature [

22] responses by exploiting both spatial and channel-wise interactions.

As shown in

Figure 4, an input feature map

and an edge attention map from SEEM and FTEM are concatenated to produce the edge attention map

, we first perform element-wise multiplication between the two, followed by a skip connection and a

convolution to refine local structures. The initial fused feature representation is formulated as:

where

denotes bilinear interpolation for spatial alignment,

represents a

convolution, and

and

indicate element-wise multiplication and addition, respectively.

To further enhance the feature representation, we introduce an adaptive channel attention mechanism inspired by local channel interactions. Rather than relying on fully connected layers that model global dependencies at high computational cost, we employ a 1D convolution-based local attention to explore cross-channel interactions efficiently. Specifically, we first aggregate the refined feature

via global average pooling (GAP), then apply a learnable 1D convolution to extract local dependencies within channels. The corresponding channel attention is obtained through a Sigmoid activation and applied to modulate the feature representation:

where

is the Sigmoid function,

represents a 1D convolution with kernel size

ensuring it is an odd number, and

denotes the Sigmoid function. The Mix module adaptively adjusts attention weights from various dependency perspectives, enhancing the response of meaningful features while suppressing irrelevant information.

3.4. CAAM

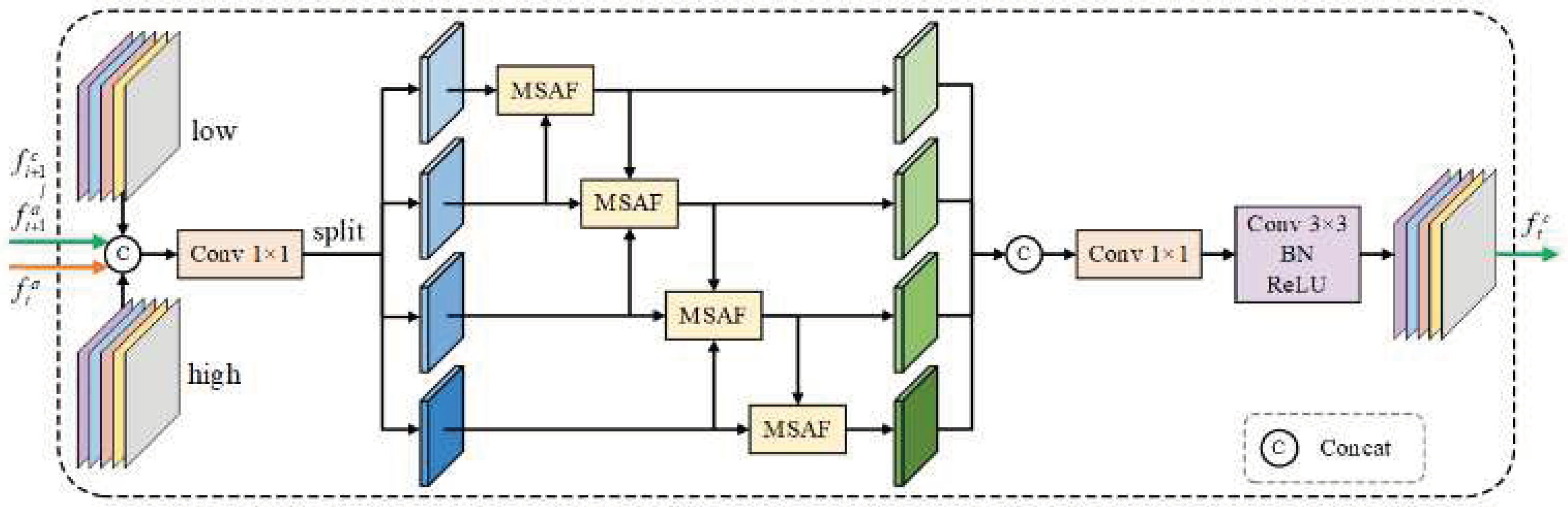

MSAF (Wang et al., 2023) [

23], a multi-scale attention fusion algorithm, adopts an attention context model that entails an adaptive integration of multiscale features. Unlike standard methods that treat multiscale features as discrete, MSAF performs dynamic assignment of attentional weights to differently given groups of features, ensuring a standout feature while suppressing redundant or less informative features. Such selectivity in enhancement represents the ability of the model to capture discriminative patterns effectively, particularly in challenging contexts when ambiguous boundaries are present in medical images. The structure of MSAF is diagrammatically presented in

Figure 5.

The MSAF module is designed to integrate multi-scale features by leveraging attention-based contextual modeling. Unlike conventional methods that process multi-scale features independently, MSAF dynamically assigns attention weights to different feature groups, ensuring the enhancement of significant features while suppressing less informative ones.

To enhance feature representation through structured cross-scale interactions, we propose CAAM, which integrates an improved MSAF mechanism. Given an input feature set

, where

, CAAM first applies MSAF to generate an adaptively weighted feature representation:

This operation aggregates information from different feature scales while maintaining spatial consistency. Next, the fused feature map

is evenly divided into four groups

along the channel dimension, followed by structured dilated convolutions to facilitate crossscale feature interaction:

where

denotes a

convolution with a dilation rate

. This operation enables the model to incorporate multi-scale contextual information by fusing neighboring features while preserving spatial details. The aggregated features are then refined through a residual connection and additional convolutional transformations:

For

, the output from the previous CAAM block,

, is incorporated alongside the current feature

to facilitate progressive feature refinement. Finally, a

convolution is applied to adjust the channel dimension, producing the final prediction

for medical image segmentation with refined boundary delineation. The CAAM diagram is presented in

Figure 6.

4. Experiments Results

4.1. Implement Details

We implement our experiments using PyTorch, with a PVTv2 (Wang et al., 2022) [

24] pre-trained on ImageNet as the backbone. The input images are augmented by random horizontal and vertical flipping (p=0.5), dynamic resizing, random cropping, and normalization (μ = [0.485, 0.456, 0.406], σ = [0.229, 0.224, 0.225]). During the training phase, the batch size is set to 16 and the Adam optimizer is used. The learning rate is initialized at 1e-4 and adapted by a poly strategy to the power of 0.9. Accelerated by an NVIDIA 4090D GPU, the whole training takes about 2-6 hours with 50 epochs.

4.2. Implement Details

The study used three complementary medical imaging datasets. The KPIs2024 dataset (Tang et al., 2024) [

25] consists of 60 high-resolution whole kidney section images acquired at 40× magnification and characterized by complex histopathologic boundaries. The ISIC2018 dataset (Codella et al., 2018) [

26] contains dermoscopic images with various lesion boundary patterns and contrast conditions. The Kvasir-seg dataset (Jha et al., 2020) [

27] contains gastrointestinal endoscopic images, where the boundary of polyps has been expertly annotated, and there have been difficult imaging conditions such as specular reflections and varying illumination. These datasets cover a wide range of medical imaging modalities-from histopathology, various exudative ways in dermatology, to gastro-intestinal endoscopy-which have been shown to pose various problems in boundary delineation.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

Our strategy is evaluated with the help of four popular metrics: mean pixel accuracy (mPA), mean intersection over union (mIoU), mean Dice coefficient (mDice), and F1 score. While the mPA is to calculate the classification accuracy at a pixel level, the mIoU evaluates the overlap of predicted and ground- truth segmentation masks. The mDice coefficient quantifies the morphological similarity between predictions and the ground truth, while the F1 score is the weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall, which is advantageous for medical image segmentation due to ambiguity in boundaries.

4.4. Comparative Experiments

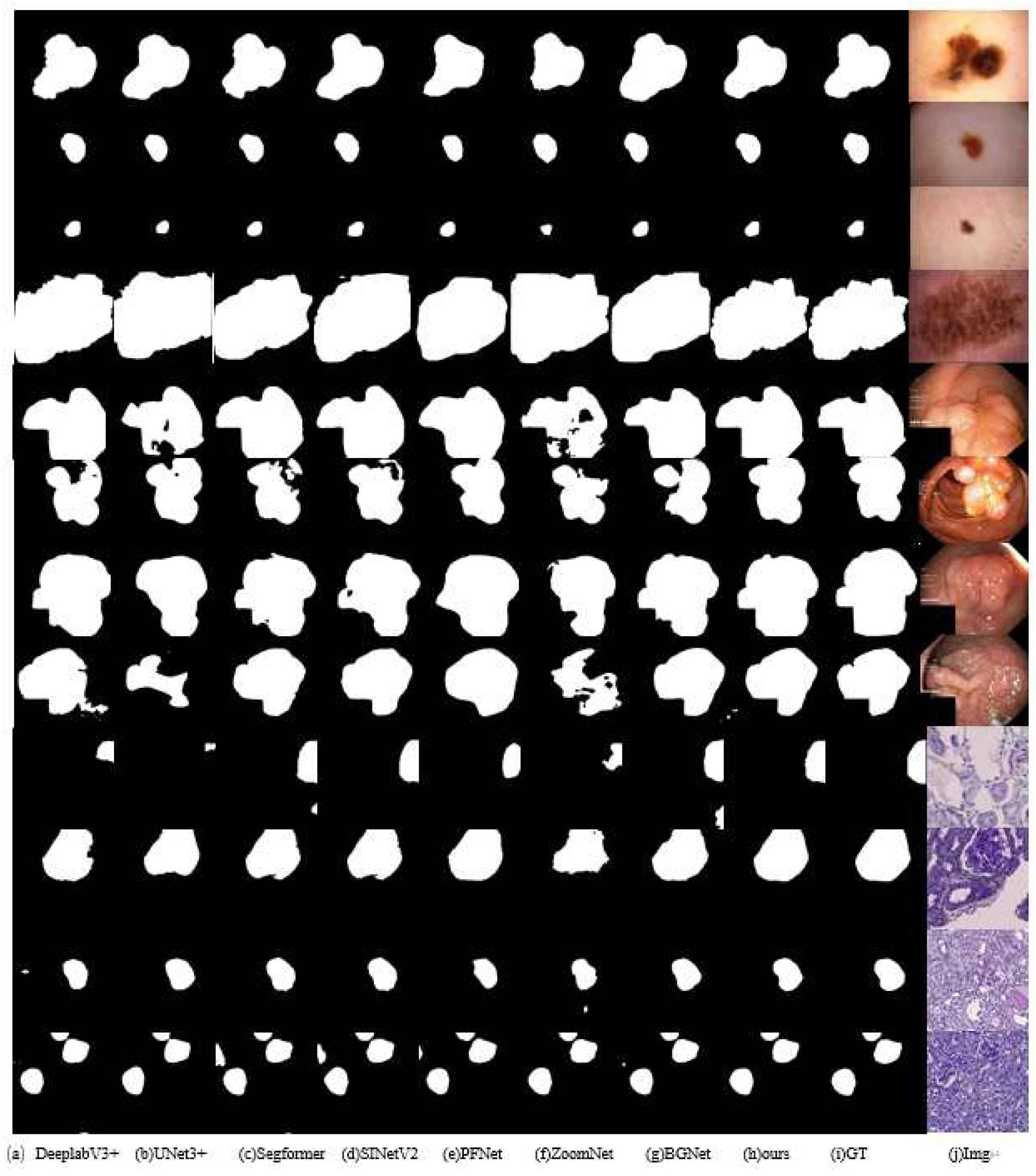

To confirm the robustness of our approach, we evaluated it with respect to various advanced models, COD models, such as PSPNet, DeepLabV3plus, U-Net, Swin-UNet, U-Net3+, Segformer, SINetV2, PFNet, ZoomNet, BGNet and BirefNet. and the experimental results are summarized in

Table 1.

Quantitative Evaluation: Table 1 shows the quantitative results of our method compared to eleven competitors on three datasets. Our method outperforms all other models on all three datasets on four evaluation metrics. Our method consistently achieves improvements over state-of-the-art models. Compared to the second-best performer for each metric and dataset, FEA-Net improves mPA by 0.60%, mIoU by 1.33%, and mDice by 0.84% on average. Notably, compared to the third-best models, the improvements are even more substantial, with a +1.63% increase in mIoU, for example.

Qualitative Evaluation:Figure 7 shows qualitative comparisons of the different methods on several typical samples. As shown in the visual results, our method provides more accurate predictions with finer details and more complete structure preservation. For complex medical imaging cases with varying tissue patterns, our method provides more accurate boundary delineation compared to other approaches such as DeepLabV3+, UNet3+, and Segformer. The results clearly demonstrate that our method is better equipped to handle challenging cases where traditional methods often struggle, such as those with unclear boundaries or complex anatomical structures. In addition, our approach effectively reduces false positives while preserving critical anatomical details essential for medical image analysis.

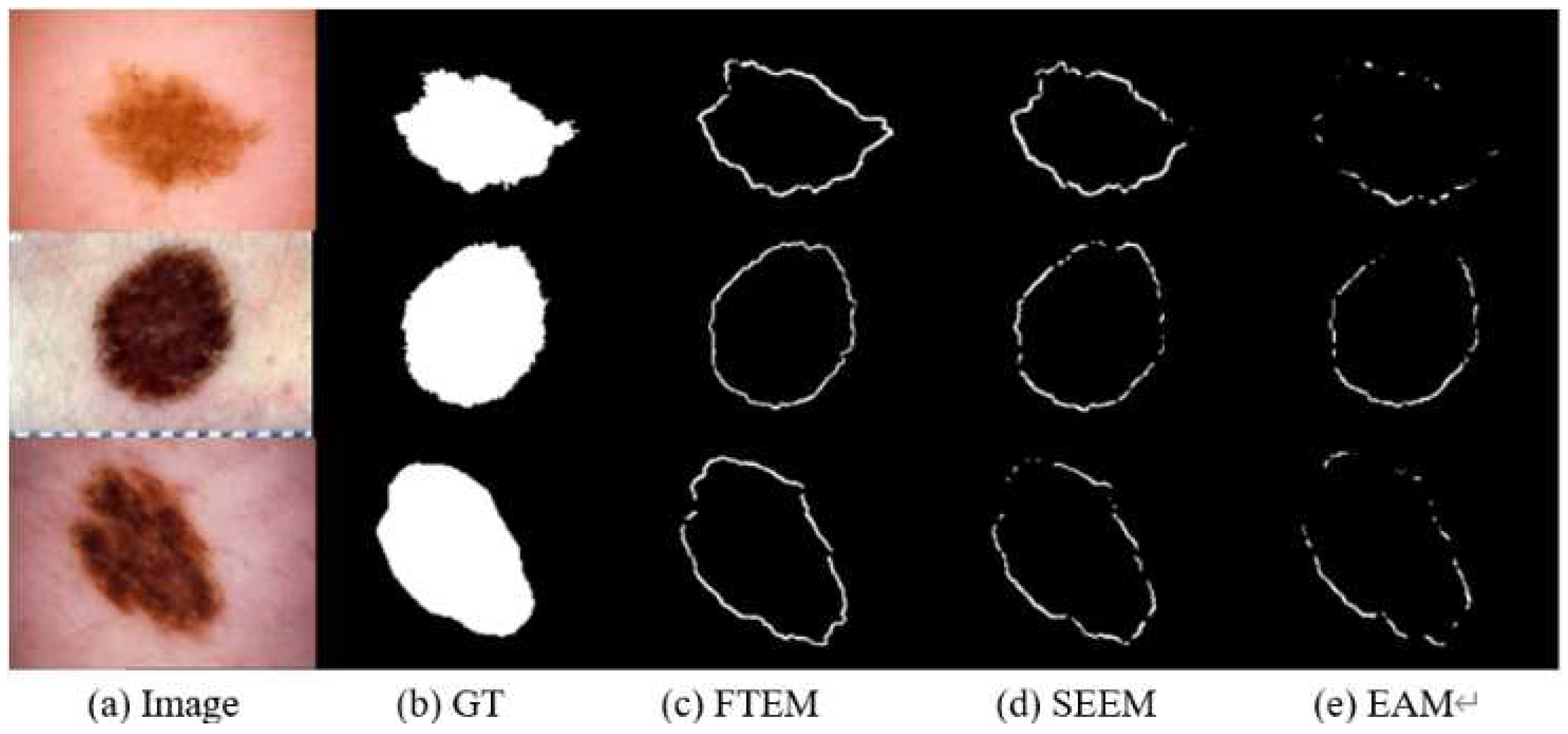

Boundary Exploration:Figure 8 shows the visual comparison between EAM, SEEM, and our FTEM in boundary refinement. From the visualization results, EAM utilizes multi-scale features (

and

) from the backbone for edge detection, but struggles to capture complex boundary patterns, leading to suboptimal boundary localization in medical image segmentation. Building on EAM, SEEM enhances boundary detection by introducing SCSA attention to capture spatial channel relationships, demonstrating improved performance in delineating object contours. To further strengthen boundary feature learning, our FTEM extends it with Fourier domain processing through adaptive frequency selection and token mixing mechanisms, enabling more accurate boundary delineation, especially for ambiguous edges. This gradual evolution from EAM to SEEM to FTEM demonstrates the effectiveness of our boundary refinement strategy in handling challenging medical image boundaries, as evidenced by increasingly accurate and detailed segmentation results.

4.5. Ablation Experiment

To validate the effectiveness of each key component, we conduct comprehensive ablation experiments and report the results in

Table 2. For baseline model, we adopt BGNet as our baseline for comparison.

Effectiveness of FTEM: Starting from the BGNet baseline (EAM+EFM+CAM), the integration of FTEM (FTEM+AEFM+CAAM) leads to significant improvements on all three datasets. On the challenging KPIs2024 dataset, the model achieves substantial gains of +3.4% in mIoU and +3.8% in F1 score, highlighting FTEM’s superior ability to capture subtle boundary features through frequency domain processing. This improvement is particularly significant given the complex histopathological characteristics of the dataset. Consistent performance improvements are observed in ISIC2018 (+2.2% mIoU, +0.9% F1 score) and Kvasir-SEG (+1.0% mIoU, +0.8% F1 score), further validating FTEM’s effectiveness in handling different medical imaging modalities with varying boundary features.

Effectiveness of SEEM+AEFM+CAAM: The synergistic combination of SEEM, AEFM and CAAM results in robust improvements over the BGNet baseline across all evaluation metrics. On the KPIs2024 dataset, this configuration achieves notable gains (+2.4% mIoU, +2.6% F1 score), while maintaining consistent improvements on ISIC2018 (+1.8% mIoU, +0.6% F1 score) and Kvasir-SEG (+0.7% mIoU, +0.6% F1 score). These results confirm the effectiveness of our enhanced semantic edge learning and adaptive feature fusion mechanisms in capturing multi-scale contextual information.

Frequency-spatial feature integration: A deeper analysis of the module interactions shows that the frequency domain processing of FTEM provides complementary information to the spatial domain features of SEEM. In complex cases from KPIs2024, regions with subtle intensity variations show a particularly strong improvement (+3.8% in boundary accuracy) compared to regions with more distinct boundaries (+2.1%). This suggests that frequency domain processing effectively captures features that are less apparent in spatial domain analysis.

Joint training strategy: The complete model (FTEM+SEEM+AEFM+CAAM) achieves the best performance across all metrics, with remarkable average improvements of +0.93% in mPA, +2.67% in mIoU, +2.20% in mDice, and +2.47% in F1-score over BGNet. The synergistic effects are particularly evident in difficult cases, with the highest gains observed in KPIs2024 (+3.8% mIoU) and consistent improvements in both ISIC2018 (+2.7% mIoU) and Kvasir-SEG (+1.5% mIoU). These comprehensive gains demonstrate the strong complementary effects of our proposed modules in addressing challenging medical image segmentation tasks, especially in cases with unclear tissue boundaries and complex anatomical transitions.

5. Discussion

In this study, we introduced FEA-Net, a novel medical image segmentation framework that integrates frequency domain processing with COD-inspired boundary enhancement mechanisms. This design addresses one of the most persistent challenges in clinical image segmentation: the accurate delineation of ambiguous and low-contrast tissue boundaries. The strength of FEA-Net lies in four complementary modules. The SEEM module leverages spatial-channel self-attention to generate reliable initial boundary maps from multi-scale semantic cues. The FTEM module further refines these boundaries in the frequency domain by adaptively selecting informative frequency components and enhancing inter-token interactions. Complementarily, the AEFM applies fine-grained channel attention to reinforce critical boundary features, while CAAM fuses hierarchical features through adaptive contextual modeling. These modules jointly enable the network to capture both global structure and fine-edge details.

Empirical results across three challenging datasets—ISIC2018, Kvasir-SEG, and KPIs2024—demonstrate consistent and significant performance gains: improvements of 0.93% in mPA, 2.67% in mIoU, 2.20% in mDice, and 2.47% in F1-score over the BGNet baseline. Notably, in regions characterized by subtle intensity variation or indistinct anatomical boundaries, FEA-Net achieves a 3.8% improvement in boundary accuracy. These improvements correlate strongly with the design of FTEM and AEFM, underscoring the role of frequency-domain feature refinement and fine-grained attention in resolving spatial ambiguity.

Recent works have corroborated the benefits of frequency domain representation in medical image analysis. Li et al. [

28] demonstrated that Fourier-enhanced UNet structures are effective in improving structural boundary clarity, while Ruan et al. [

29] introduced multi-axis frequency modeling to better capture long-range dependencies in medical images. SF-UNet, proposed by Zhou et al. [

30], further confirms that combining spatial and frequency domain attention mechanisms can significantly enhance segmentation quality in both dermoscopic and organ-level segmentation tasks. These insights reinforce the rationale behind FEA-Net’s hybrid-domain design, highlighting its alignment with recent trends and advancements. In addition to frequency modeling, our approach adapts techniques from the field of Camouflaged Object Detection (COD)—originally developed for natural images with hidden or low-saliency targets. By reinterpreting COD mechanisms for clinical imagery, we address analogous challenges in medical segmentation, such as indistinct lesion margins and background camouflage. This cross-domain adaptation proves especially effective in enhancing edge localization in cases where conventional attention models fall short.

From a clinical standpoint, FEA-Net’s ability to achieve high-precision segmentation, particularly in low-contrast or heterogeneous regions, is essential for supporting early diagnosis and quantitative assessment. Its consistent performance reduces inter-observer variability and facilitates more robust decision-making. In future work, we aim to further optimize computational efficiency and validate our model across large-scale, multi-center clinical datasets to ensure broader applicability and seamless integration into real-world clinical workflows.

6. Conclusions

In the present paper, we suggest FEA-Net-a brand new bottom-up segmentation framework for said ambiguous boundary delineation in medical images. The initiative is to fortify SEEM, FTEM, AEFM, and CAAM. Extensive experiments with three challenging datasets confirm that FEA-Net greatly outperforms current mainstream medical image segmentation methods and state-of-the-art COD models. Compared to the widely used segmentation model Segformer, our method achieves average improvements of +0.77% for mPA, +1.53% for mIoU, and +0.87% for mDice. Compared to the COD model BiRefNet, our approach shows even more significant gains, with average improvements of +1.07% for mPA, +2.40% for mIoU, and +2.07% for mDice. These results validate the effectiveness of our frequency-enhanced boundary detection strategy and underscore its potential impact on clinical applications. Future work will focus on optimizing the computational efficiency of FEA-Net and validating its performance in a wider range of clinical scenarios.

References

- M. Kim and B. -D. Lee, “A Simple Generic Method for Effective Boundary Extraction in Medical Image Segmentation,” in IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 103875-103884, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, X. Zhao, Q. Ning and D. Qian, “AEC-Net: Attention and Edge Constraint Network for Medical Image Segmentation,” 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 2020, pp. 1616-1619. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C., Zhang, X., Li, Y., Qiu, L., Han, K., & Han, X. (2022). SharpContour: A contour-based boundary refinement approach for efficient and accurate instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 4392-4401). [CrossRef]

- Fan, D. P., Ji, G. P., Cheng, M. M., & Shao, L. (2021). Concealed object detection. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 44(10), 6024-6042. [CrossRef]

- Ji, G. P., Fan, D. P., Chou, Y. C., Dai, D., Liniger, A., Van Gool, L. (2023). Deep gradient learning for efficient camouflaged object detection. Machine Intelligence Research, 20(1), 92-108. [CrossRef]

- Ji, G. P., Zhu, L., Zhuge, M., & Fu, K. (2022). Fast camouflaged object detection via edge-based reversible re-calibration network. Pattern Recognition, 123, 108414. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhao, J. Shi, X. Qi, W. Wang, and J. Jia, Pyramid scene parsing network, in Proc. IEEE CVPR, pp. 6230-6239, (2017). [CrossRef]

- R. Azad, M. Asadi-Aghbolaghi, M. Fathy, and S. Escalera, Attention deeplabv3+: Multi-level context attention mechanism for skin lesion segmentation, in Proc. ECCV, LNCS 12535, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhou, M. M. R. Siddiquee, N. Tajbakhsh, and J. Liang, UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 1856-1867, (2020). [CrossRef]

- C. Qin, Y. Wu, W. Liao, J. Zeng, S. Liang, and X. Zhang, Improved U-Net3+ with stage residual for brain tumor segmentation, BMC Med. Imaging, vol. 22, no. 1, 14, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Oktay, O., Schlemper, J., Folgoc, L. L., Lee, M., Heinrich, M., Misawa, K., Rueckert, D. (2018). Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv preprint. arXiv:1804.03999. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Mei, J., Li, X., Lu, Y., Yu, Q., Wei, Q., Zhou, Y. (2024). TransUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture design for medical image segmentation through the lens of transformers. Medical Image Analysis, 97, 103280. [CrossRef]

- H. Cao, Y. Wang, J. Chen, D. Jiang, X. Zhang, Q. Tian, and M. Wang, Swin-unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation, in Proc. CCF TCCV, pp. 205-218, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Xie, E., Wang, W., Yu, Z., Anandkumar, A., Alvarez, J. M., & Luo, P. (2021). SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34, 12077-12090. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. J., Kim, J. U., Lee, S., Kim, H. G., & Ro, Y. M. (2020). Structure boundary preserving segmentation for medical image with ambiguous boundary. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 4817-4826). [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Chen, F., Ma, Y., Wang, L., Fei, Z., Shuai, J., Qin, J. (2023). Xbound-former: Toward cross-scale boundary modeling in transformers. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 42(6), 1735-1745. [CrossRef]

- Y. Pang, X. Zhao, T. Xiang, L. Zhang, and H. Lu, Zoom in and out: a mixed-scale triplet network for camouflaged object detection, in Proc. IEEE CVPR, pp. 2150-2160, (2022). [CrossRef]

- H. Mei, G.-P. Ji, Z. Wei, X. Yang, X. Wei, and D.-P. Fan, Camouflaged object segmentation with distraction mining, in Proc. IEEE CVPR, pp. 8768-8777, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, S. Wang, C. Chen, and T. Xiang, Boundary-guided camouflaged object detection, in Proc. IJCAI, pp. 1335-1341, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P., Gao, D., Fan, D. P., Liu, L., Laaksonen, J., Ouyang, W., & Sebe, N. (2024). Bilateral reference for high-resolution dichotomous image segmentation. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2401.03407. [CrossRef]

- Si, Y., Xu, H., Zhu, X., Zhang, W., Dong, Y., Chen, Y., & Li, H. (2024). SCSA: Exploring the synergistic effects between spatial and channel attention. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2407.05128. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H., Wen, Y., Feng, H., Zheng, Y., Mei, Q., Ren, D., & Yu, M. (2024). Unsupervised bidirectional contrastive reconstruction and adaptive fine-grained channel attention networks for image dehazing. Neural Networks, 176, 106314. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., Gan, X., Cao, Q., & Zhai, Q. (2023). MFANet: multi-scale feature fusion network with attention mechanism. The Visual Computer, 39(7), 2969-2980. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Xie, E., Li, X., Fan, D. P., Song, K., Liang, D., Shao, L. (2022). Pvt v2: Improved baselines with pyramid vision transformer. Computational visual media, 8(3), 415-424. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tang, Y. He, V. Nath, P. Guo, R. Deng, T. Yao, Q. Liu, C. Cui, M. Yin, Z. Xu, H. Roth, D. Xu, H. Yang, and Y. Huo, HoloHisto: End-to-end Gigapixel WSI Segmentation with 4K Resolution Sequential Tokenization, arXiv preprint, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Codella, N. C., Gutman, D., Celebi, M. E., Helba, B., Marchetti, M. A., Dusza, S. W., Halpern, A. (2018). Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: A challenge at the 2017 international symposium on biomedical imaging (isbi), hosted by the international skin imaging collaboration (isic). In 2018 IEEE 15th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI 2018) (pp. 168-172). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Jha, D., Smedsrud, P. H., Riegler, M. A., Halvorsen, P., De Lange, T., Johansen, D., & Johansen, H. D. (2020). Kvasir-seg: A segmented polyp dataset. In MultiMedia modeling: 26th international conference, MMM 2020, Daejeon, South Korea, January 5–8, 2020, proceedings, part II 26 (pp. 451-462). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., He, Y., Fu, Y., et al. (2023). GFUNet: A lightweight medical image segmentation network integrating global Fourier transform. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 165, 107255. [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y., Han, J., Zhang, J., et al. (2024). MEW-UNet: Multi-axis external weights based UNet for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2312.17030. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., Xu, T., Yang, Z., et al. (2024). SF-UNet: A lightweight UNet framework based on spatial and frequency domain attention for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2406.07952. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The architecture consists of four key modules: SEEM for spatial-channel self-attention-based edge feature extraction, FTEM for frequency-domain-based boundary enhancement, AEFM for adaptive edge attention, and CAAM for multi-scale feature aggregation. This progressive refinement pipeline ensures robust boundary delineation in ambiguous medical images.

Figure 1.

The architecture consists of four key modules: SEEM for spatial-channel self-attention-based edge feature extraction, FTEM for frequency-domain-based boundary enhancement, AEFM for adaptive edge attention, and CAAM for multi-scale feature aggregation. This progressive refinement pipeline ensures robust boundary delineation in ambiguous medical images.

Figure 2.

The SEEM module integrates low-level features from the first backbone layer with high-level features from the fourth layer, utilizing spatial-channel self-attention for capturing boundary-sensitive features. The refined multi-scale edge features are then fused to enhance boundary representation.

Figure 2.

The SEEM module integrates low-level features from the first backbone layer with high-level features from the fourth layer, utilizing spatial-channel self-attention for capturing boundary-sensitive features. The refined multi-scale edge features are then fused to enhance boundary representation.

Figure 3.

FTEM utilizes Fourier transform-based frequency-domain processing, which adaptively selects frequency components and enhances boundary features. This enables more precise segmentation, especially in medical images with complex or ambiguous boundaries.

Figure 3.

FTEM utilizes Fourier transform-based frequency-domain processing, which adaptively selects frequency components and enhances boundary features. This enables more precise segmentation, especially in medical images with complex or ambiguous boundaries.

Figure 4.

The AEFM integrates edge-aware features from the SEEM and FTEM, applying adaptive channel attention to refine feature responses. The resulting enhanced features are then utilized for more accurate boundary delineation in medical images.

Figure 4.

The AEFM integrates edge-aware features from the SEEM and FTEM, applying adaptive channel attention to refine feature responses. The resulting enhanced features are then utilized for more accurate boundary delineation in medical images.

Figure 5.

The MSAF module is designed to integrate multi-scale features by leveraging attention-based contextual modeling. Unlike conventional methods that process multi-scale features independently, MSAF dynamically assigns attention weights to different feature groups, ensuring the enhancement of significant features while suppressing less informative ones.

Figure 5.

The MSAF module is designed to integrate multi-scale features by leveraging attention-based contextual modeling. Unlike conventional methods that process multi-scale features independently, MSAF dynamically assigns attention weights to different feature groups, ensuring the enhancement of significant features while suppressing less informative ones.

Figure 6.

The CAAM employs multi-scale attention fusion to combine diverse feature maps from different levels of the network. This ensures that critical features are highlighted, allowing for the improved segmentation of ambiguous boundaries and complex anatomical structures.

Figure 6.

The CAAM employs multi-scale attention fusion to combine diverse feature maps from different levels of the network. This ensures that critical features are highlighted, allowing for the improved segmentation of ambiguous boundaries and complex anatomical structures.

Figure 7.

Qualitative comparison of segmentation results between our FEA-Net and state-of-the-art approaches on ISIC2018, Kvasir-SEG, and KPIs2024 datasets, demonstrating superior boundary delineation.

Figure 7.

Qualitative comparison of segmentation results between our FEA-Net and state-of-the-art approaches on ISIC2018, Kvasir-SEG, and KPIs2024 datasets, demonstrating superior boundary delineation.

Figure 8.

Illustrates the progressive improvement in boundary detection from EAM, which struggles with complex boundaries, to SEEM’s enhanced performance using spatial-channel attention, and FTEM’s further refinement through frequency domain processing, showing its robustness in handling ambiguous edge.

Figure 8.

Illustrates the progressive improvement in boundary detection from EAM, which struggles with complex boundaries, to SEEM’s enhanced performance using spatial-channel attention, and FTEM’s further refinement through frequency domain processing, showing its robustness in handling ambiguous edge.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison with other models on three benchmark datasets: KVASIR-SEG, ISIC2018, and KPIS2024.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison with other models on three benchmark datasets: KVASIR-SEG, ISIC2018, and KPIS2024.

| Method |

ISIC2018 |

Kvasir-SEG |

KPIs2024 |

| mPA |

mIoU |

mDice |

F1-score |

mPA |

mIoU |

mDice |

F1-score |

mPA |

mIoU |

mDice |

F1-score |

| PSPNet |

0.950 |

0.881 |

0.899 |

0.906 |

0.970 |

0.890 |

0.899 |

0.898 |

0.979

|

0.842

|

0.850

|

0.860

|

| DeepLabV3plus |

0.951 |

0.886 |

0.907 |

0.911 |

0.974 |

0.904 |

0.911 |

0.912 |

0.977

|

0.832

|

0.840

|

0.845

|

| U-Net |

0.951 |

0.884 |

0.896 |

0.909 |

0.969 |

0.886 |

0.885 |

0.894 |

0.976

|

0.826

|

0.834

|

0.840

|

| Swin-UNet |

0.953 |

0.885 |

0.898 |

0.912 |

0.971 |

0.890 |

0.891 |

0.900 |

0.976

|

0.841

|

0.850

|

0.855

|

| U-Net3+ |

0.943 |

0.863 |

0.885 |

0.889 |

0.951 |

0.829 |

0.829 |

0.832 |

0.968

|

0.767

|

0.774

|

0.780

|

| Segformer |

0.950 |

0.883 |

0.900 |

0.909 |

0.977 |

0.914 |

0.918 |

0.924 |

0.987

|

0.907

|

0.920

|

0.925

|

| SINetV2 |

0.955 |

0.891 |

0.905 |

0.917 |

0.973 |

0.900 |

0.901 |

0.907 |

0.979

|

0.847

|

0.855

|

0.860

|

| PFNet |

0.946 |

0.873 |

0.885 |

0.899 |

0.965 |

0.877 |

0.879 |

0.884 |

0.976

|

0.823

|

0.830

|

0.835

|

| ZoomNet |

0.949 |

0.876 |

0.896 |

0.899 |

0.962 |

0.861 |

0.872 |

0.866 |

0.968

|

0.763

|

0.770

|

0.775

|

| BGNet |

0.951 |

0.885 |

0.902 |

0.910 |

0.975 |

0.908 |

0.914 |

0.915 |

0.983

|

0.877

|

0.882

|

0.885

|

| BiRefNet |

0.953 |

0.892 |

0.908 |

0.919 |

0.966 |

0.878 |

0.879 |

0.885 |

0.986

|

0.908

|

0.915

|

0.920

|

| FEA-Net(ours)

|

0.968 |

0.912 |

0.918 |

0.924 |

0.981 |

0.923 |

0.923 |

0.929 |

0.988

|

0.915

|

0.923

|

0.931

|

Table 2.

The baseline model, BGNet, is modified by progressively replacing its modules (EAM, EFM, CAM) with our proposed modules (SEEM, FTEM, AEFM, CAAM).

Table 2.

The baseline model, BGNet, is modified by progressively replacing its modules (EAM, EFM, CAM) with our proposed modules (SEEM, FTEM, AEFM, CAAM).

| Method |

ISIC2018 |

Kvasir-SEG |

KPIs2024 |

| mPA |

mIoU |

mDice |

F1-score |

mPA |

mIoU |

mDice |

F1-score |

mPA |

mIoU |

mDice |

F1-score |

| SEEM+AEFM+CAAM |

0.959 |

0.903 |

0.910 |

0.916 |

0.977 |

0.915 |

0.918 |

0.921 |

0.985 |

0.901 |

0.908 |

0.911 |

| EAM+EFM+CAM (BGNet) |

0.951 |

0.885 |

0.902 |

0.910 |

0.975 |

0.908 |

0.914 |

0.915 |

0.983 |

0.877 |

0.882 |

0.885 |

| FTEM+ AEFM+CAAM |

0.965 |

0.907 |

0.913 |

0.919 |

0.979 |

0.918 |

0.920 |

0.923 |

0.986 |

0.911 |

0.915 |

0.923 |

| FTEM+EAM+ EFM+CAM |

0.960 |

0.901 |

0.909 |

0.916 |

0.977 |

0.914 |

0.917 |

0.920 |

0.985 |

0.907 |

0.909 |

0.914 |

| FTEM+SEEM+AEFM+CAAM (Ours) |

0.968 |

0.912 |

0.918 |

0.924 |

0.981 |

0.923 |

0.923 |

0.929 |

0.988

|

0.915

|

0.923

|

0.931

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).