Submitted:

10 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Molecular Biomarkers

Molecular Biomarkers with Non-Specific Radiotracers

FDG-PET

SPECT

ECD and HMPAO- SPECT

Dopamine Transporter SPECT

Specific Radiotracers

Amyloid PET

Tau PET

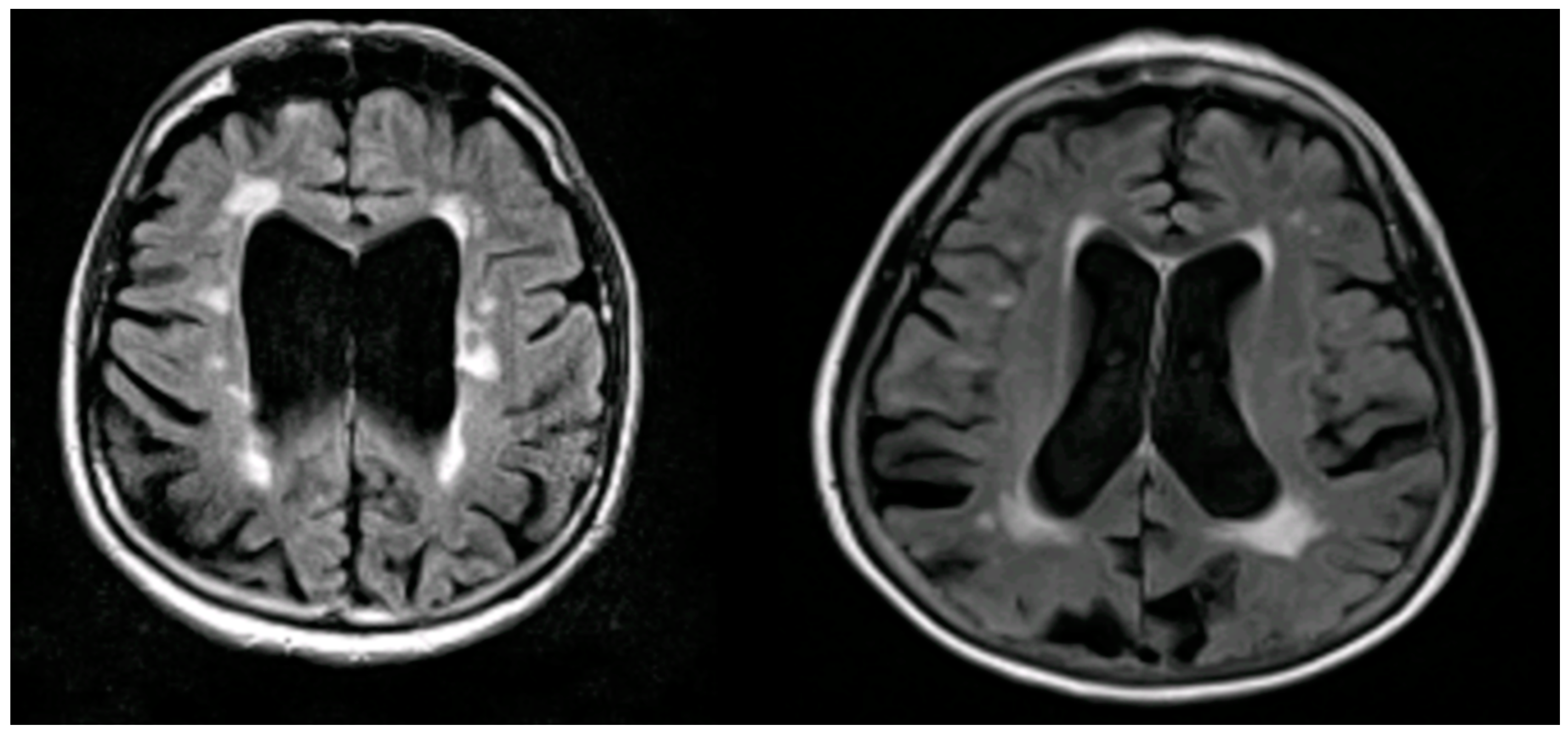

Structural Biomarkers

MRI Biomarkers in AD

Conclusion

References

- Agdeppa, E.D., Kepe, V., Liu, J., Flores-Torres, S., Satyamurthy, N., Petric, A., Cole, G.M., Small, G.W., Huang, S.C., Barrio, J.R., 2001. Binding characteristics of radiofluorinated 6-dialkylamino-2-naphthylethylidene derivatives as positron emission tomography imaging probes for beta-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 21, RC189. [CrossRef]

- AKDEMİR, Ü.Ö., BORA TOKÇAER, A., ATAY1, L.Ö., 2021. Dopamine transporter SPECT imaging in Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonian disorders. Turk J Med Sci 51, 400–410. [CrossRef]

- Antonini, A., Leenders, K.L., Vontobel, P., Maguire, R.P., Missimer, J., Psylla, M., Günther, I., 1997. Complementary PET studies of striatal neuronal function in the differential diagnosis between multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease. Brain 120, 2187–2195. [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, P.V., Growdon, J.H., Hedley-Whyte, E.T., Hyman, B.T., 1992. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 42, 631–639. [CrossRef]

- Bachurin, S.O., Bovina, E.V., Ustyugov, A.A., 2017. Drugs in Clinical Trials for Alzheimer’s Disease: The Major Trends. Med Res Rev 37, 1186–1225. [CrossRef]

- Bailly, M., Destrieux, C., Hommet, C., Mondon, K., Cottier, J.-P., Beaufils, E., Vierron, E., Vercouillie, J., Ibazizene, M., Voisin, T., Payoux, P., Barré, L., Camus, V., Guilloteau, D., Ribeiro, M.-J., 2015. Precuneus and Cingulate Cortex Atrophy and Hypometabolism in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: MRI and 18F-FDG PET Quantitative Analysis Using FreeSurfer. Biomed Res Int 2015. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A., Albert, M.S., Krauss, G., Speck, C.L., Gallagher, M., 2015. Response of the medial temporal lobe network in amnestic mild cognitive impairment to therapeutic intervention assessed by fMRI and memory task performance. Neuroimage Clin 7, 688–698. [CrossRef]

- Barthel, H., 2020. First Tau PET Tracer Approved: Toward Accurate In Vivo Diagnosis of Alzheimer Disease. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 61, 1409–1410. [CrossRef]

- Bendlin, B.B., Carlsson, C.M., Johnson, S.C., Zetterberg, H., Blennow, K., Willette, A.A., Okonkwo, O.C., Sodhi, A., Ries, M.L., Birdsill, A.C., Alexander, A.L., Rowley, H.A., Puglielli, L., Asthana, S., Sager, M.A., 2012. CSF T-Tau/Aβ42 predicts white matter microstructure in healthy adults at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 7, e37720. [CrossRef]

- Bhogal, P., Mahoney, C., Graeme-Baker, S., Roy, A., Shah, S., Fraioli, F., Cowley, P., Jäger, H.R., 2013. The common dementias: a pictorial review. Eur Radiol 23, 3405–3417. [CrossRef]

- Bierer, L.M., Hof, P.R., Purohit, D.P., Carlin, L., Schmeidler, J., Davis, K.L., Perl, D.P., 1995. Neocortical Neurofibrillary Tangles Correlate With Dementia Severity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Archives of Neurology 52, 81–88. [CrossRef]

- Bouter, C., Henniges, P., Franke, T.N., Irwin, C., Sahlmann, C.O., Sichler, M.E., Beindorff, N., Bayer, T.A., Bouter, Y., 2018. 18F-FDG-PET Detects Drastic Changes in Brain Metabolism in the Tg4-42 Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci 10, 425. [CrossRef]

- Braak, H., Braak, E., 1997. Staging of Alzheimer-related cortical destruction. Int Psychogeriatr 9 Suppl 1, 257–261; discussion 269-272.

- Braak, H., Braak, E., 1991. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82, 239–259. [CrossRef]

- Brass, L.M., Walovitch, R.C., Joseph, J.L., Léveillé, J., Marchand, L., Hellman, R.S., Tikofsky, R.S., Masdeu, J.C., Hall, K.M., Van Heertum, R.L., 1994. The role of single photon emission computed tomography brain imaging with 99mTc-bicisate in the localization and definition of mechanism of ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 14 Suppl 1, S91-98.

- Brigo, F., Matinella, A., Erro, R., Tinazzi, M., 2014. [123I]FP-CIT SPECT (DaTSCAN) may be a useful tool to differentiate between Parkinson’s disease and vascular or drug-induced parkinsonisms: a meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol 21, 1369-e90. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.A., Deng, J., Neuhaus, J., Sible, I.J., Sias, A.C., Lee, S.E., Kornak, J., Marx, G.A., Karydas, A.M., Spina, S., Grinberg, L.T., Coppola, G., Geschwind, D.H., Kramer, J.H., Gorno-Tempini, M.L., Miller, B.L., Rosen, H.J., Seeley, W.W., 2019. Patient-Tailored, Connectivity-Based Forecasts of Spreading Brain Atrophy. Neuron 104, 856-868.e5. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.K.J., Bohnen, N.I., Wong, K.K., Minoshima, S., Frey, K.A., 2014. Brain PET in Suspected Dementia: Patterns of Altered FDG Metabolism. RadioGraphics 34, 684–701. [CrossRef]

- Catafau, A.M., 2001. Brain SPECT in clinical practice. Part I: perfusion. J Nucl Med 42, 259–271.

- Chen, G., Ward, B.D., Xie, C., Li, W., Wu, Z., Jones, J.L., Franczak, M., Antuono, P., Li, S.-J., 2011. Classification of Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, and normal cognitive status with large-scale network analysis based on resting-state functional MR imaging. Radiology 259, 213–221. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Langbaum, J.B.S., Fleisher, A.S., Ayutyanont, N., Reschke, C., Lee, W., Liu, X., Bandy, D., Alexander, G.E., Thompson, P.M., Foster, N.L., Harvey, D.J., de Leon, M.J., Koeppe, R.A., Jagust, W.J., Weiner, M.W., Reiman, E.M., 2010. Twelve-Month Metabolic Declines in Probable Alzheimer’s Disease and Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment Assessed Using an Empirically Pre-Defined Statistical Region-of-Interest: Findings from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Neuroimage 51, 654–664. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-D., Lu, J.-Y., Li, H.-Q., Yang, Y.-X., Jiang, J.-H., Cui, M., Zuo, C.-T., Tan, L., Dong, Q., Yu, J.-T., for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Weiner, M.W., Aisen, P., Petersen, Ronald, Jack, C.R., Jagust, W., Trojanowki, J.Q., Toga, A.W., Beckett, L., Green, R.C., Saykin, A.J., Morris, J.C., Perrin, R.J., Shaw, L.M., Carrillo, M., Potter, W., Barnes, L., Bernard, M., González, H., Ho, C., Hsiao, J.K., Jackson, J., Masliah, E., Masterman, D., Okonkwo, O., Perrin, R., Ryan, L., Silverberg, N., Fleisher, A., Sacrey, D.T., Fockler, J., Conti, C., Veitch, D., Neuhaus, J., Jin, C., Nosheny, R., Ashford, M., Flenniken, D., Kormos, A., Rafii, M., Raman, R., Jimenez, G., Donohue, Michael, Gessert, D., Salazar, J., Zimmerman, C., Cabrera, Y., Walter, S., Miller, G., Coker, G., Clanton, T., Hergesheimer, L., Smith, S., Adegoke, O., Mahboubi, P., Moore, S., Pizzola, J., Shaffer, E., Sloan, B., Harvey, D., Forghanian-Arani, A., Borowski, B., Ward, C., Schwarz, C., Jones, D., Gunter, J., Kantarci, K., Senjem, Matthew, Vemuri, P., Reid, R., Fox, N.C., Malone, I., Thompson, P., Thomopoulos, S.I., Nir, T.M., Jahanshad, N., DeCarli, C., Knaack, A., Fletcher, E., Tosun-Turgut, D., Chen, S.R., Choe, M., Crawford, K., Yushkevich, P.A., Das, S., Koeppe, R.A., Reiman, E.M., Chen, K., Mathis, C., Landau, S., Cairns, N.J., Householder, E., Franklin, E., Bernhardt, H., Taylor-Reinwald, L., Shaw, L.M., Trojanowki, J.Q., Korecka, M., Figurski, M., Crawford, K., Neu, S., Saykin, A.J., Nho, K., Risacher, S.L., Apostolova, L.G., Shen, L., Foroud, T.M., Nudelman, K., Faber, K., Wilmes, K., Thal, L., Khachaturian, Z., Hsiao, J.K., Silbert, L.C., Lind, B., Crissey, R., Kaye, J.A., Carter, R., Dolen, S., Quinn, J., Schneider, L.S., Pawluczyk, S., Becerra, M., Teodoro, L., Dagerman, K., Spann, B.M., Brewer, J., Vanderswag, H., Fleisher, A., Ziolkowski, J., Heidebrink, J.L., Zbizek-Nulph, L., Lord, J.L., Mason, S.S., Albers, C.S., Knopman, D., Johnson, Kris, Villanueva-Meyer, J., Pavlik, V., Pacini, N., Lamb, A., Kass, J.S., Doody, R.S., Shibley, V., Chowdhury, M., Rountree, S., Dang, M., Stern, Y., Honig, L.S., Mintz, A., Ances, B., Winkfield, D., Carroll, M., Stobbs-Cucchi, G., Oliver, A., Creech, M.L., Mintun, M.A., Schneider, S., Geldmacher, D., Love, M.N., Griffith, R., Clark, D., Brockington, J., Marson, D., Grossman, H., Goldstein, M.A., Greenberg, J., Mitsis, E., Shah, R.C., Lamar, M., Samuels, P., Duara, R., Greig-Custo, M.T., Rodriguez, R., Albert, M., Onyike, C., Farrington, L., Rudow, S., Brichko, R., Kielb, S., Smith, A., Raj, B.A., Fargher, K., Sadowski, M., Wisniewski, T., Shulman, M., Faustin, A., Rao, J., Castro, K.M., Ulysse, A., Chen, S., Sheikh, M.O., Singleton-Garvin, J., Doraiswamy, P.M., Petrella, J.R., James, O., Wong, T.Z., Borges-Neto, S., Karlawish, J.H., Wolk, D.A., Vaishnavi, S., Clark, C.M., Arnold, S.E., Smith, C.D., Jicha, G.A., El Khouli, R., Raslau, F.D., Lopez, O.L., Oakley, M., Simpson, D.M., Porsteinsson, A.P., Martin, K., Kowalski, N., Keltz, M., Goldstein, B.S., Makino, K.M., Ismail, M.S., Brand, C., Thai, G., Pierce, A., Yanez, B., Sosa, E., Witbracht, M., Kelley, B., Nguyen, T., Womack, K., Mathews, D., Quiceno, M., Levey, A.I., Lah, J.J., Hajjar, I., Cellar, J.S., Burns, J.M., Swerdlow, R.H., Brooks, W.M., Silverman, D.H.S., Kremen, S., Apostolova, L., Tingus, K., Lu, P.H., Bartzokis, G., Woo, E., Teng, E., Graff-Radford, N.R., Parfitt, F., Poki-Walker, K., Farlow, M.R., Hake, A.M., Matthews, B.R., Brosch, J.R., Herring, S., van Dyck, C.H., Mecca, A.P., Good, S.P., MacAvoy, M.G., Carson, R.E., Varma, P., Chertkow, H., Vaitekunis, S., Hosein, C., Black, S., Stefanovic, B., Heyn, C., Hsiung, G.-Y.R., Kim, E., Mudge, B., Sossi, V., Feldman, H., Assaly, M., Finger, E., Pasternak, S., Rachinsky, I., Kertesz, A., Drost, D., Rogers, J., Grant, I., Muse, B., Rogalski, E., Robson, J., Mesulam, M.-M., Kerwin, D., Wu, C.-K., Johnson, N., Lipowski, K., Weintraub, S., Bonakdarpour, B., Pomara, N., Hernando, R., Sarrael, A., Rosen, H.J., Miller, B.L., Perry, D., Turner, R.S., Johnson, Kathleen, Reynolds, B., MCCann, K., Poe, J., Sperling, R.A., Johnson, K.A., Marshall, G.A., Belden, C.M., Atri, A., Spann, B.M., Clark, K.A., Zamrini, E., Sabbagh, M., Killiany, R., Stern, R., Mez, J., Kowall, N., Budson, A.E., Obisesan, T.O., Ntekim, O.E., Wolday, S., Khan, J.I., Nwulia, E., Nadarajah, S., Lerner, A., Ogrocki, P., Tatsuoka, C., Fatica, P., Fletcher, E., Maillard, P., Olichney, J., DeCarli, C., Carmichael, O., Bates, V., Capote, H., Rainka, M., Borrie, M., Lee, T.-Y., Bartha, R., Johnson, S., Asthana, S., Carlsson, C.M., Perrin, A., Burke, A., Scharre, D.W., Kataki, M., Tarawneh, R., Kelley, B., Hart, D., Zimmerman, E.A., Celmins, D., Miller, D.D., Boles Ponto, L.L., Smith, K.E., Koleva, H., Shim, H., Nam, K.W., Schultz, S.K., Williamson, J.D., Craft, S., Cleveland, J., Yang, M., Sink, K.M., Ott, B.R., Drake, J., Tremont, G., Daiello, L.A., Drake, J.D., Sabbagh, M., Ritter, A., Bernick, C., Munic, D., Mintz, A., O’Connelll, A., Mintzer, J., Wiliams, A., Masdeu, J., Shi, J., Garcia, A., Sabbagh, M., Newhouse, P., Potkin, S., Salloway, S., Malloy, P., Correia, S., Kittur, S., Pearlson, G.D., Blank, K., Anderson, K., Flashman, L.A., Seltzer, M., Hynes, M.L., Santulli, R.B., Relkin, N., Chiang, G., Lin, M., Ravdin, L., Lee, A., Petersen, Ron, Neylan, T., Grafman, J., Montine, T., Petersen, Ronald, Hergesheimer, L., Danowski, S., Nguyen-Barrera, C., Hayes, J., Finley, S., Donohue, Michael, Bernstein, M., Senjem, Matt, Ward, C., Chen, S.R., Koeppe, R.A., Foster, N., Foroud, T.M., Potkin, S., Shen, L., Faber, K., Kim, S., Nho, K., Wilmes, K., Spann, B.M., Vanderswag, H., Fleisher, A., Sood, A., Blanchard, K.S., Fleischman, D., Arfanakis, K., Varon, D., Greig, M.T., Goldstein, B., Martin, K.S., Thai, G., Pierce, A., Reist, C., Yanez, B., Sosa, E., Witbracht, M., Sadowsky, C., Martinez, W., Villena, T., Rosen, H., Marshall, G., Nadarajah, S., Peskind, E.R., Petrie, E.C., Li, G., Yesavage, J., Taylor, J.L., Chao, S., Coleman, J., White, J.D., Lane, B., Rosen, A., Tinklenberg, J., Chiang, G., Mackin, S., Raman, R., Jimenez-Maggiora, G., Gessert, D., Salazar, J., Zimmerman, C., Walter, S., Adegoke, O., Mahboubi, P., Drake, E., Donohue, Mike, Nelson, C., Bickford, D., Butters, M., Zmuda, M., Borowski, B., Gunter, J., Senjem, Matt, Kantarci, K., Ward, C., Reyes, D., Faber, K.M., Nudelman, K.N., Au, Y.H., Scherer, K., Catalinotto, D., Stark, S., Ong, E., Fernandez, D., Zmuda, M., 2021. Staging tau pathology with tau PET in Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal study. Transl Psychiatry 11, 483. [CrossRef]

- Chien, D.T., Bahri, S., Szardenings, A.K., Walsh, J.C., Mu, F., Su, M.-Y., Shankle, W.R., Elizarov, A., Kolb, H.C., 2013. Early clinical PET imaging results with the novel PHF-tau radioligand [F-18]-T807. J. Alzheimers Dis. 34, 457–468. [CrossRef]

- Chincarini, A., Bosco, P., Calvini, P., Gemme, G., Esposito, M., Olivieri, C., Rei, L., Squarcia, S., Rodriguez, G., Bellotti, R., Cerello, P., De Mitri, I., Retico, A., Nobili, F., Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, 2011. Local MRI analysis approach in the diagnosis of early and prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 58, 469–480. [CrossRef]

- Cho, H., Choi, J.Y., Hwang, M.S., Lee, J.H., Kim, Y.J., Lee, H.M., Lyoo, C.H., Ryu, Y.H., Lee, M.S., 2016. Tau PET in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 87, 375–383. [CrossRef]

- Chow, T.W., Fam, D., Graff-Guerrero, A., Verhoeff, N.P.G., Tang-Wai, D.F., Masellis, M., Black, S.E., Wilson, A.A., Houle, S., Pollock, B.G., 2013. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in semantic dementia after 6 months of memantine: an open-label pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 28, 319–325. [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.M., Schneider, J.A., Bedell, B.J., Beach, T.G., Bilker, W.B., Mintun, M.A., Pontecorvo, M.J., Hefti, F., Carpenter, A.P., Flitter, M.L., Krautkramer, M.J., Kung, H.F., Coleman, R.E., Doraiswamy, P.M., Fleisher, A.S., Sabbagh, M.N., Sadowsky, C.H., Reiman, E.P., Reiman, P.E.M., Zehntner, S.P., Skovronsky, D.M., AV45-A07 Study Group, 2011. Use of florbetapir-PET for imaging beta-amyloid pathology. JAMA 305, 275–283. [CrossRef]

- Claus, J.J., Walstra, G.J., Hijdra, A., Van Royen, E.A., Verbeeten, B., van Gool, W.A., 1999. Measurement of temporal regional cerebral perfusion with single-photon emission tomography predicts rate of decline in language function and survival in early Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med 26, 265–271. [CrossRef]

- Corrada, M.M., Brookmeyer, R., Paganini-Hill, A., Berlau, D., Kawas, C.H., 2010. Dementia Incidence Continues to Increase with Age in the Oldest Old The 90+ Study. Ann Neurol 67, 114–121. [CrossRef]

- Croall, I.D., Lohner, V., Moynihan, B., Khan, U., Hassan, A., O’Brien, J.T., Morris, R.G., Tozer, D.J., Cambridge, V.C., Harkness, K., Werring, D.J., Blamire, A.M., Ford, G.A., Barrick, T.R., Markus, H.S., 2017. Using DTI to assess white matter microstructure in cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) in multicentre studies. Clin Sci (Lond) 131, 1361–1373. [CrossRef]

- Dave, A., Hansen, N., Downey, R., Johnson, C., 2020. FDG-PET Imaging of Dementia and Neurodegenerative Disease. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 41, 562–571. [CrossRef]

- Declercq, L., Rombouts, F., Koole, M., Fierens, K., Mariën, J., Langlois, X., Andrés, J.I., Schmidt, M., Macdonald, G., Moechars, D., Vanduffel, W., Tousseyn, T., Vandenberghe, R., Van Laere, K., Verbruggen, A., Bormans, G., 2017. Preclinical Evaluation of 18F-JNJ64349311, a Novel PET Tracer for Tau Imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 58, 975–981. [CrossRef]

- Devous, M.D., 2005. Single-photon emission computed tomography in neurotherapeutics. NeuroRx 2, 237–249. [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, B.C., Bakkour, A., Salat, D.H., Feczko, E., Pacheco, J., Greve, D.N., Grodstein, F., Wright, C.I., Blacker, D., Rosas, H.D., Sperling, R.A., Atri, A., Growdon, J.H., Hyman, B.T., Morris, J.C., Fischl, B., Buckner, R.L., 2009. The cortical signature of Alzheimer’s disease: regionally specific cortical thinning relates to symptom severity in very mild to mild AD dementia and is detectable in asymptomatic amyloid-positive individuals. Cereb Cortex 19, 497–510. [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, B.C., Salat, D.H., Bates, J.F., Atiya, M., Killiany, R.J., Greve, D.N., Dale, A.M., Stern, C.E., Blacker, D., Albert, M.S., Sperling, R.A., 2004. Medial temporal lobe function and structure in mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol 56, 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, B.C., Stoub, T.R., Shah, R.C., Sperling, R.A., Killiany, R.J., Albert, M.S., Hyman, B.T., Blacker, D., Detoledo-Morrell, L., 2011. Alzheimer-signature MRI biomarker predicts AD dementia in cognitively normal adults. Neurology 76, 1395–1402. [CrossRef]

- Dougall, N.J., Bruggink, S., Ebmeier, K.P., 2004. Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of 99mTc-HMPAO-SPECT in dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12, 554–570. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B., Feldman, H.H., Jacova, C., Hampel, H., Molinuevo, J.L., Blennow, K., DeKosky, S.T., Gauthier, S., Selkoe, D., Bateman, R., Cappa, S., Crutch, S., Engelborghs, S., Frisoni, G.B., Fox, N.C., Galasko, D., Habert, M.-O., Jicha, G.A., Nordberg, A., Pasquier, F., Rabinovici, G., Robert, P., Rowe, C., Salloway, S., Sarazin, M., Epelbaum, S., de Souza, L.C., Vellas, B., Visser, P.J., Schneider, L., Stern, Y., Scheltens, P., Cummings, J.L., 2014. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol 13, 614–629. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B., von Arnim, C.A.F., Burnie, N., Bozeat, S., Cummings, J., 2023. Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: role in early and differential diagnosis and recognition of atypical variants. Alzheimers Res Ther 15, 175. [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, S., Caroli, A., Geroldi, C., Barillot, C., Frisoni, G.B., Collins, D.L., 2008. MRI-based automated computer classification of probable AD versus normal controls. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 27, 509–520. [CrossRef]

- Echeveste, B., Prieto, E., Guillén, E.F., Jimenez, A., Montoya, G., Villino, R., Riverol, M., Arbizu, J., 2025. Combination of amyloid and FDG PET for the prediction of short-term conversion from MCI to Alzheimer´s disease in the clinical practice. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. [CrossRef]

- Elman, J.A., Panizzon, M.S., Gustavson, D.E., Franz, C.E., Sanderson-Cimino, M.E., Lyons, M.J., Kremen, W.S., 2020. Amyloid-β Positivity Predicts Cognitive Decline but Cognition Predicts Progression to Amyloid-β Positivity. Biological Psychiatry 87, 819–828. [CrossRef]

- Esrael, S.M.A.M., Hamed, A.M.M., Khedr, E.M., Soliman, R.K., 2021. Application of diffusion tensor imaging in Alzheimer’s disease: quantification of white matter microstructural changes. Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine 52, 89. [CrossRef]

- Filippi, L., Chiaravalloti, A., Bagni, O., Schillaci, O., 2018. 18F-labeled radiopharmaceuticals for the molecular neuroimaging of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 8, 268–281.

- Fleisher, A.S., Pontecorvo, M.J., Devous, M.D., Lu, M., Arora, A.K., Truocchio, S.P., Aldea, P., Flitter, M., Locascio, T., Devine, M., Siderowf, A., Beach, T.G., Montine, T.J., Serrano, G.E., Curtis, C., Perrin, A., Salloway, S., Daniel, M., Wellman, C., Joshi, A.D., Irwin, D.J., Lowe, V.J., Seeley, W.W., Ikonomovic, M.D., Masdeu, J.C., Kennedy, I., Harris, T., Navitsky, M., Southekal, S., Mintun, M.A., A16 Study Investigators, 2020. Positron Emission Tomography Imaging With [18F]flortaucipir and Postmortem Assessment of Alzheimer Disease Neuropathologic Changes. JAMA Neurol 77, 829–839. [CrossRef]

- Fodero-Tavoletti, M.T., Okamura, N., Furumoto, S., Mulligan, R.S., Connor, A.R., McLean, C.A., Cao, D., Rigopoulos, A., Cartwright, G.A., O’Keefe, G., Gong, S., Adlard, P.A., Barnham, K.J., Rowe, C.C., Masters, C.L., Kudo, Y., Cappai, R., Yanai, K., Villemagne, V.L., 2011. 18F-THK523: a novel in vivo tau imaging ligand for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 134, 1089–1100. [CrossRef]

- Frisoni, G.B., Pievani, M., Testa, C., Sabattoli, F., Bresciani, L., Bonetti, M., Beltramello, A., Hayashi, K.M., Toga, A.W., Thompson, P.M., 2007. The topography of grey matter involvement in early and late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 130, 720–730. [CrossRef]

- Georgakas, J.E., Howe, M.D., Thompson, L.I., Riera, N.M., Riddle, M.C., 2023. Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: Past, present and future clinical use. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry 8, 100063. [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, L.C., Knust, H., Körner, M., Honer, M., Czech, C., Belli, S., Muri, D., Edelmann, M.R., Hartung, T., Erbsmehl, I., Grall-Ulsemer, S., Koblet, A., Rueher, M., Steiner, S., Ravert, H.T., Mathews, W.B., Holt, D.P., Kuwabara, H., Valentine, H., Dannals, R.F., Wong, D.F., Borroni, E., 2017. Identification of Three Novel Radiotracers for Imaging Aggregated Tau in Alzheimer’s Disease with Positron Emission Tomography. J. Med. Chem. 60, 7350–7370. [CrossRef]

- Greicius, M.D., Srivastava, G., Reiss, A.L., Menon, V., 2004. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 4637–4642. [CrossRef]

- Gunes, S., Aizawa, Y., Sugashi, T., Sugimoto, M., Rodrigues, P.P., 2022. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease in the Current State: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci 23, 4962. [CrossRef]

- Haller, S., Vernooij, M.W., Kuijer, J.P.A., Larsson, E.-M., Jäger, H.R., Barkhof, F., 2018. Cerebral Microbleeds: Imaging and Clinical Significance. Radiology 287, 11–28. [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H., O’Bryant, S.E., Durrleman, S., Younesi, E., Rojkova, K., Escott-Price, V., Corvol, J.-C., Broich, K., Dubois, B., Lista, S., Alzheimer Precision Medicine Initiative, 2017. A Precision Medicine Initiative for Alzheimer’s disease: the road ahead to biomarker-guided integrative disease modeling. Climacteric 20, 107–118. [CrossRef]

- Harada, R., Okamura, N., Furumoto, S., Furukawa, K., Ishiki, A., Tomita, N., Hiraoka, K., Watanuki, S., Shidahara, M., Miyake, M., Ishikawa, Y., Matsuda, R., Inami, A., Yoshikawa, T., Tago, T., Funaki, Y., Iwata, R., Tashiro, M., Yanai, K., Arai, H., Kudo, Y., 2015. [(18)F]THK-5117 PET for assessing neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 42, 1052–1061. [CrossRef]

- Harada, R., Okamura, N., Furumoto, S., Furukawa, K., Ishiki, A., Tomita, N., Tago, T., Hiraoka, K., Watanuki, S., Shidahara, M., Miyake, M., Ishikawa, Y., Matsuda, R., Inami, A., Yoshikawa, T., Funaki, Y., Iwata, R., Tashiro, M., Yanai, K., Arai, H., Kudo, Y., 2016. 18F-THK5351: A Novel PET Radiotracer for Imaging Neurofibrillary Pathology in Alzheimer Disease. J Nucl Med 57, 208–214. [CrossRef]

- Harper, L., Bouwman, F., Burton, E.J., Barkhof, F., Scheltens, P., O’Brien, J.T., Fox, N.C., Ridgway, G.R., Schott, J.M., 2017. Patterns of atrophy in pathologically confirmed dementias: a voxelwise analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 88, 908–916. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T.M., Du, R., Klencklen, G., Baker, S.L., Jagust, W.J., 2021. Distinct effects of beta-amyloid and tau on cortical thickness in cognitively healthy older adults. Alzheimers Dement 17, 1085–1096. [CrossRef]

- Heyer, S., Simon, M., Doyen, M., Mortada, A., Roch, V., Jeanbert, E., Thilly, N., Malaplate, C., Kearney-Schwartz, A., Jonveaux, T., Bannay, A., Verger, A., 2024. 18F-FDG PET can effectively rule out conversion to dementia and the presence of CSF biomarker of neurodegeneration: a real-world data analysis. Alzheimers Res Ther 16, 182. [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.L.G., Schwarz, A.J., Isaac, M., Pani, L., Vamvakas, S., Hemmings, R., Carrillo, M.C., Yu, P., Sun, J., Beckett, L., Boccardi, M., Brewer, J., Brumfield, M., Cantillon, M., Cole, P.E., Fox, N., Frisoni, G.B., Jack, C., Kelleher, T., Luo, F., Novak, G., Maguire, P., Meibach, R., Patterson, P., Bain, L., Sampaio, C., Raunig, D., Soares, H., Suhy, J., Wang, H., Wolz, R., Stephenson, D., 2014. Coalition Against Major Diseases/European Medicines Agency biomarker qualification of hippocampal volume for enrichment of clinical trials in predementia stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 10, 421-429.e3. [CrossRef]

- Hohenfeld, C., Werner, C.J., Reetz, K., 2018. Resting-state connectivity in neurodegenerative disorders: Is there potential for an imaging biomarker? Neuroimage Clin 18, 849–870. [CrossRef]

- Høilund-Carlsen, P.F., Revheim, M.-E., Costa, T., Kepp, K.P., Castellani, R.J., Perry, G., Alavi, A., Barrio, J.R., 2023. FDG-PET versus Amyloid-PET Imaging for Diagnosis and Response Evaluation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Benefits and Pitfalls. Diagnostics (Basel) 13, 2254. [CrossRef]

- Holman, B.L., Johnson, K.A., Gerada, B., Carvalho, P.A., Satlin, A., 1992. The scintigraphic appearance of Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective study using technetium-99m-HMPAO SPECT. J Nucl Med 33, 181–185.

- Hostetler, E.D., Walji, A.M., Zeng, Z., Miller, P., Bennacef, I., Salinas, C., Connolly, B., Gantert, L., Haley, H., Holahan, M., Purcell, M., Riffel, K., Lohith, T.G., Coleman, P., Soriano, A., Ogawa, A., Xu, S., Zhang, X., Joshi, E., Della Rocca, J., Hesk, D., Schenk, D.J., Evelhoch, J.L., 2016. Preclinical Characterization of 18F-MK-6240, a Promising PET Tracer for In Vivo Quantification of Human Neurofibrillary Tangles. J. Nucl. Med. 57, 1599–1606. [CrossRef]

- Huijbers, W., Mormino, E.C., Schultz, A.P., Wigman, S., Ward, A.M., Larvie, M., Amariglio, R.E., Marshall, G.A., Rentz, D.M., Johnson, K.A., Sperling, R.A., 2015. Amyloid-β deposition in mild cognitive impairment is associated with increased hippocampal activity, atrophy and clinical progression. Brain 138, 1023–1035. [CrossRef]

- Humpel, C., 2011. Identifying and validating biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Biotechnol 29, 26–32. [CrossRef]

- Imokawa, T., Yokoyama, K., Takahashi, K., Oyama, J., Tsuchiya, J., Sanjo, N., Tateishi, U., 2024. Brain perfusion SPECT in dementia: what radiologists should know. Jpn J Radiol 42, 1215–1230. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, K., Imamura, T., Sasaki, M., Yamaji, S., Sakamoto, S., Kitagaki, H., Hashimoto, M., Hirono, N., Shimomura, T., Mori, E., 1998. Regional cerebral glucose metabolism in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 51, 125–130. [CrossRef]

- Ito, K., Inui, Y., Kizawa, T., Kimura, Y., Kato, T., 2017. Current and future prospects of nuclear medicine in dementia. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 57, 479–484. [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Bennett, D.A., Blennow, K., Carrillo, M.C., Dunn, B., Haeberlein, S.B., Holtzman, D.M., Jagust, W., Jessen, F., Karlawish, J., Liu, E., Molinuevo, J.L., Montine, T., Phelps, C., Rankin, K.P., Rowe, C.C., Scheltens, P., Siemers, E., Snyder, H.M., Sperling, R., Contributors, 2018. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 14, 535–562. [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Bennett, D.A., Blennow, K., Carrillo, M.C., Feldman, H.H., Frisoni, G.B., Hampel, H., Jagust, W.J., Johnson, K.A., Knopman, D.S., Petersen, R.C., Scheltens, P., Sperling, R.A., Dubois, B., 2016. A/T/N: An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology 87, 539–547. [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Knopman, D.S., Jagust, W.J., Petersen, R.C., Weiner, M.W., Aisen, P.S., Shaw, L.M., Vemuri, P., Wiste, H.J., Weigand, S.D., Lesnick, T.G., Pankratz, V.S., Donohue, M.C., Trojanowski, J.Q., 2013. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol 12, 207–216. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-W., Kim, S., Na, H.Y., Ahn, S., Lee, S.J., Kwak, K.-H., Lee, M.-A., Hsiung, G.-Y.R., Choi, B.-S., Youn, Y.C., 2013. Effect of white matter hyperintensity on medial temporal lobe atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. Neurol. 69, 229–235. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, W.J., Ossenkoppele, R., Knol, D.L., Tijms, B.M., Scheltens, P., Verhey, F.R.J., Visser, P.J., Amyloid Biomarker Study Group, Aalten, P., Aarsland, D., Alcolea, D., Alexander, M., Almdahl, I.S., Arnold, S.E., Baldeiras, I., Barthel, H., van Berckel, B.N.M., Bibeau, K., Blennow, K., Brooks, D.J., van Buchem, M.A., Camus, V., Cavedo, E., Chen, K., Chetelat, G., Cohen, A.D., Drzezga, A., Engelborghs, S., Fagan, A.M., Fladby, T., Fleisher, A.S., van der Flier, W.M., Ford, L., Förster, S., Fortea, J., Foskett, N., Frederiksen, K.S., Freund-Levi, Y., Frisoni, G.B., Froelich, L., Gabryelewicz, T., Gill, K.D., Gkatzima, O., Gómez-Tortosa, E., Gordon, M.F., Grimmer, T., Hampel, H., Hausner, L., Hellwig, S., Herukka, S.-K., Hildebrandt, H., Ishihara, L., Ivanoiu, A., Jagust, W.J., Johannsen, P., Kandimalla, R., Kapaki, E., Klimkowicz-Mrowiec, A., Klunk, W.E., Köhler, S., Koglin, N., Kornhuber, J., Kramberger, M.G., Van Laere, K., Landau, S.M., Lee, D.Y., de Leon, M., Lisetti, V., Lleó, A., Madsen, K., Maier, W., Marcusson, J., Mattsson, N., de Mendonça, A., Meulenbroek, O., Meyer, P.T., Mintun, M.A., Mok, V., Molinuevo, J.L., Møllergård, H.M., Morris, J.C., Mroczko, B., Van der Mussele, S., Na, D.L., Newberg, A., Nordberg, A., Nordlund, A., Novak, G.P., Paraskevas, G.P., Parnetti, L., Perera, G., Peters, O., Popp, J., Prabhakar, S., Rabinovici, G.D., Ramakers, I.H.G.B., Rami, L., Resende de Oliveira, C., Rinne, J.O., Rodrigue, K.M., Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E., Roe, C.M., Rot, U., Rowe, C.C., Rüther, E., Sabri, O., Sanchez-Juan, P., Santana, I., Sarazin, M., Schröder, J., Schütte, C., Seo, S.W., Soetewey, F., Soininen, H., Spiru, L., Struyfs, H., Teunissen, C.E., Tsolaki, M., Vandenberghe, R., Verbeek, M.M., Villemagne, V.L., Vos, S.J.B., van Waalwijk van Doorn, L.J.C., Waldemar, G., Wallin, A., Wallin, Å.K., Wiltfang, J., Wolk, D.A., Zboch, M., Zetterberg, H., 2015. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA 313, 1924–1938. [CrossRef]

- Jingnan Wang, Ekin, A., de Haan, G., 2008. Shape analysis of brain ventricles for improved classification of Alzheimer’s patients, in: 2008 15th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing. Presented at the 2008 15th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, IEEE, San Diego, CA, USA, pp. 2252–2255. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A., Fox, N.C., Sperling, R.A., Klunk, W.E., 2012. Brain imaging in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2, a006213. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A., Minoshima, S., Bohnen, N.I., Donohoe, K.J., Foster, N.L., Herscovitch, P., Karlawish, J.H., Rowe, C.C., Carrillo, M.C., Hartley, D.M., Hedrick, S., Pappas, V., Thies, W.H., Alzheimer’s Association, Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, Amyloid Imaging Taskforce, 2013. Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: a report of the Amyloid Imaging Task Force, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimers Dement 9, e-1-16. [CrossRef]

- Kälin, A.M., Park, M.T.M., Chakravarty, M.M., Lerch, J.P., Michels, L., Schroeder, C., Broicher, S.D., Kollias, S., Nitsch, R.M., Gietl, A.F., Unschuld, P.G., Hock, C., Leh, S.E., 2017. Subcortical Shape Changes, Hippocampal Atrophy and Cortical Thinning in Future Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Front Aging Neurosci 9, 38. [CrossRef]

- Kanekar, S., Poot, J.D., 2014. Neuroimaging of vascular dementia. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 52, 383–401. [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, E.G., McNulty, J.P., Mullins, P.G., Bokde, A.L.W., 2014. Advances in MRI biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomark Med 8, 1151–1169. [CrossRef]

- Kemp, P.M., Holmes, C., Hoffmann, S.M.A., Bolt, L., Holmes, R., Rowden, J., Fleming, J.S., 2003. Alzheimer’s disease: differences in technetium-99m HMPAO SPECT scan findings between early onset and late onset dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74, 715–719. [CrossRef]

- Khazaee, A., Ebrahimzadeh, A., Babajani-Feremi, A., 2015. Identifying patients with Alzheimer’s disease using resting-state fMRI and graph theory. Clin Neurophysiol 126, 2132–2141. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.W., MacFall, J.R., Payne, M.E., 2008. Classification of white matter lesions on magnetic resonance imaging in elderly persons. Biol Psychiatry 64, 273–280. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Rosenberg, P., Oh, E., 2018. A Review of Diagnostic Impact of Amyloid Positron Emission Tomography Imaging in Clinical Practice. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 46, 154–167. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y., Endo, H., Ichise, M., Shimada, H., Seki, C., Ikoma, Y., Shinotoh, H., Yamada, M., Higuchi, M., Zhang, M.-R., Suhara, T., 2016. A new method to quantify tau pathologies with (11)C-PBB3 PET using reference tissue voxels extracted from brain cortical gray matter. EJNMMI Res 6, 24. [CrossRef]

- Kljajevic, V., Grothe, M.J., Ewers, M., Teipel, S., Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, 2014. Distinct pattern of hypometabolism and atrophy in preclinical and predementia Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 35, 1973–1981. [CrossRef]

- Klunk, W.E., Engler, H., Nordberg, A., Wang, Y., Blomqvist, G., Holt, D.P., Bergström, M., Savitcheva, I., Huang, G., Estrada, S., Ausén, B., Debnath, M.L., Barletta, J., Price, J.C., Sandell, J., Lopresti, B.J., Wall, A., Koivisto, P., Antoni, G., Mathis, C.A., Långström, B., 2004. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann. Neurol. 55, 306–319. [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara, H., Comley, R.A., Borroni, E., Honer, M., Kitmiller, K., Roberts, J., Gapasin, L., Mathur, A., Klein, G., Wong, D.F., 2018. Evaluation of 18F-RO-948 PET for Quantitative Assessment of Tau Accumulation in the Human Brain. J Nucl Med 59, 1877–1884. [CrossRef]

- Landau, S.M., Harvey, D., Madison, C.M., Koeppe, R.A., Reiman, E.M., Foster, N.L., Weiner, M.W., Jagust, W.J., Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, 2011. Associations between cognitive, functional, and FDG-PET measures of decline in AD and MCI. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 1207–1218. [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, A.V., Westman, E., Beyer, M.K., Kramberger, M.G., Aguilar, C., Pirtosek, Z., Aarsland, D., 2013. Multivariate classification of patients with Alzheimer’s and dementia with Lewy bodies using high-dimensional cortical thickness measurements: an MRI surface-based morphometric study. J Neurol 260, 1104–1115. [CrossRef]

- Leuzy, A., Chiotis, K., Lemoine, L., Gillberg, P.-G., Almkvist, O., Rodriguez-Vieitez, E., Nordberg, A., 2019. Tau PET imaging in neurodegenerative tauopathies—still a challenge. Mol Psychiatry 24, 1112–1134. [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, S.N., Schöll, M., Baker, S.L., Ayakta, N., Swinnerton, K.N., Bell, R.K., Mellinger, T.J., Shah, V.D., O’Neil, J.P., Janabi, M., Jagust, W.J., 2017. Amyloid and tau PET demonstrate region-specific associations in normal older people. Neuroimage 150, 191–199. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C., Mena, E., Subramaniam, R.M., 2014. Brain PET in the Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Clin Nucl Med 39, e413–e426. [CrossRef]

- Marquié, M., Chong, M.S.T., Antón-Fernández, A., Verwer, E.E., Sáez-Calveras, N., Meltzer, A.C., Ramanan, P., Amaral, A.C., Gonzalez, J., Normandin, M.D., Frosch, M.P., Gómez-Isla, T., 2017. [F-18]-AV-1451 binding correlates with postmortem neurofibrillary tangle Braak staging. Acta Neuropathol 134, 619–628. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Macintosh, E.L., Broski, S.M., Johnson, G.B., Hunt, C.H., Cullen, E.L., Peller, P.J., 2016. Multimodality Imaging of Neurodegenerative Processes: Part 1, The Basics and Common Dementias. AJR Am J Roentgenol 207, 871–882. [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, M., Shimada, H., Suhara, T., Shinotoh, H., Ji, B., Maeda, J., Zhang, M.-R., Trojanowski, J.Q., Lee, V.M.-Y., Ono, M., Masamoto, K., Takano, H., Sahara, N., Iwata, N., Okamura, N., Furumoto, S., Kudo, Y., Chang, Q., Saido, T.C., Takashima, A., Lewis, J., Jang, M.-K., Aoki, I., Ito, H., Higuchi, M., 2013. Imaging of tau pathology in a tauopathy mouse model and in Alzheimer patients compared to normal controls. Neuron 79, 1094–1108. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, H., Mizumura, S., Nagao, T., Ota, T., Iizuka, T., Nemoto, K., Takemura, N., Arai, H., Homma, A., 2007. Automated discrimination between very early Alzheimer disease and controls using an easy Z-score imaging system for multicenter brain perfusion single-photon emission tomography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 28, 731–736.

- Matsunari, I., Samuraki, M., Chen, W.-P., Yanase, D., Takeda, N., Ono, K., Yoshita, M., Matsuda, H., Yamada, M., Kinuya, S., 2007. Comparison of 18F-FDG PET and optimized voxel-based morphometry for detection of Alzheimer’s disease: aging effect on diagnostic performance. J. Nucl. Med. 48, 1961–1970. [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, N., Carrillo, M.C., Dean, R.A., Devous, M.D., Nikolcheva, T., Pesini, P., Salter, H., Potter, W.Z., Sperling, R.S., Bateman, R.J., Bain, L.J., Liu, E., 2015. Revolutionizing Alzheimer’s disease and clinical trials through biomarkers. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 1, 412–419. [CrossRef]

- McKhann, G.M., Knopman, D.S., Chertkow, H., Hyman, B.T., Jack, C.R., Kawas, C.H., Klunk, W.E., Koroshetz, W.J., Manly, J.J., Mayeux, R., Mohs, R.C., Morris, J.C., Rossor, M.N., Scheltens, P., Carrillo, M.C., Thies, B., Weintraub, S., Phelps, C.H., 2011. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 263–269. [CrossRef]

- Minoshima, S., Mosci, K., Cross, D., Thientunyakit, T., 2021. Brain [F-18]FDG PET for Clinical Dementia Workup: Differential Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Types of Dementing Disorders. Semin Nucl Med 51, 230–240. [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.C., Ernesto, C., Schafer, K., Coats, M., Leon, S., Sano, M., Thal, L.J., Woodbury, P., 1997. Clinical dementia rating training and reliability in multicenter studies: the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study experience. Neurology 48, 1508–1510. [CrossRef]

- Mosconi, L., 2013. Glucose metabolism in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease: Methodological and physiological considerations for PET studies. Clin Transl Imaging 1. [CrossRef]

- Mosconi, L., Tsui, W.H., Herholz, K., Pupi, A., Drzezga, A., Lucignani, G., Reiman, E.M., Holthoff, V., Kalbe, E., Sorbi, S., Diehl-Schmid, J., Perneczky, R., Clerici, F., Caselli, R., Beuthien-Baumann, B., Kurz, A., Minoshima, S., de Leon, M.J., 2008. Multicenter standardized 18F-FDG PET diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and other dementias. J. Nucl. Med. 49, 390–398. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK), 2018. Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK), London.

- Nelson, P.T., Alafuzoff, I., Bigio, E.H., Bouras, C., Braak, H., Cairns, N.J., Castellani, R.J., Crain, B.J., Davies, P., Del Tredici, K., Duyckaerts, C., Frosch, M.P., Haroutunian, V., Hof, P.R., Hulette, C.M., Hyman, B.T., Iwatsubo, T., Jellinger, K.A., Jicha, G.A., Kövari, E., Kukull, W.A., Leverenz, J.B., Love, S., Mackenzie, I.R., Mann, D.M., Masliah, E., McKee, A.C., Montine, T.J., Morris, J.C., Schneider, J.A., Sonnen, J.A., Thal, D.R., Trojanowski, J.Q., Troncoso, J.C., Wisniewski, T., Woltjer, R.L., Beach, T.G., 2012. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 71, 362–381. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T., Hashikawa, K., Fukuyama, H., Kubota, T., Kitamura, S., Matsuda, H., Hanyu, H., Nabatame, H., Oku, N., Tanabe, H., Kuwabara, Y., Jinnouchi, S., Kubol, A., 2007. Decreased cerebral blood flow and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a multicenter HMPAO-SPECT study. Ann Nucl Med 21, 15–23. [CrossRef]

- Nitrini, R., Buchpiguel, C.A., Caramelli, P., Bahia, V.S., Mathias, S.C., Nascimento, C.M., Degenszajn, J., Caixeta, L., 2000. SPECT in Alzheimer’s disease: features associated with bilateral parietotemporal hypoperfusion. Acta Neurol Scand 101, 172–176. [CrossRef]

- Nordberg, A., Carter, S.F., Rinne, J., Drzezga, A., Brooks, D.J., Vandenberghe, R., Perani, D., Forsberg, A., Långström, B., Scheinin, N., Karrasch, M., Någren, K., Grimmer, T., Miederer, I., Edison, P., Okello, A., Van Laere, K., Nelissen, N., Vandenbulcke, M., Garibotto, V., Almkvist, O., Kalbe, E., Hinz, R., Herholz, K., 2013. A European multicentre PET study of fibrillar amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 40, 104–114. [CrossRef]

- Okamura, N., Furumoto, S., Fodero-Tavoletti, M.T., Mulligan, R.S., Harada, R., Yates, P., Pejoska, S., Kudo, Y., Masters, C.L., Yanai, K., Rowe, C.C., Villemagne, V.L., 2014. Non-invasive assessment of Alzheimer’s disease neurofibrillary pathology using 18F-THK5105 PET. Brain 137, 1762–1771. [CrossRef]

- Okello, A., Koivunen, J., Edison, P., Archer, H.A., Turkheimer, F.E., Någren, K., Bullock, R., Walker, Z., Kennedy, A., Fox, N.C., Rossor, M.N., Rinne, J.O., Brooks, D.J., 2009. Conversion of amyloid positive and negative MCI to AD over 3 years. Neurology 73, 754–760. [CrossRef]

- Ossenkoppele, R., Smith, R., Mattsson-Carlgren, N., Groot, C., Leuzy, A., Strandberg, O., Palmqvist, S., Olsson, T., Jögi, J., Stormrud, E., Cho, H., Ryu, Y.H., Choi, J.Y., Boxer, A.L., Gorno-Tempini, M.L., Miller, B.L., Soleimani-Meigooni, D., Iaccarino, L., La Joie, R., Baker, S., Borroni, E., Klein, G., Pontecorvo, M.J., Devous, M.D., Jagust, W.J., Lyoo, C.H., Rabinovici, G.D., Hansson, O., 2021. Accuracy of Tau Positron Emission Tomography as a Prognostic Marker in Preclinical and Prodromal Alzheimer Disease: A Head-to-Head Comparison Against Amyloid Positron Emission Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JAMA Neurol 78, 961–971. [CrossRef]

- Ossenkoppele, R., Smith, R., Ohlsson, T., Strandberg, O., Mattsson, N., Insel, P.S., Palmqvist, S., Hansson, O., 2019. Associations between tau, Aβ, and cortical thickness with cognition in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 92, e601–e612. [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.-N., Xu, W., Li, J.-Q., Guo, Y., Cui, M., Chen, K.-L., Huang, Y.-Y., Dong, Q., Tan, L., Yu, J.-T., on behalf of Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, 2019. FDG-PET as an independent biomarker for Alzheimer’s biological diagnosis: a longitudinal study. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 11, 57. [CrossRef]

- Oxford, A.E., Stewart, E.S., Rohn, T.T., 2020. Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Hurdle in the Path of Remedy. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2020, 5380346. [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, M., Amthauer, H., Klaffke, S., Kühn, A., Lüdemann, L., Arnold, G., Wernecke, K.-D., Kupsch, A., Felix, R., Venz, S., 2005. Combined 123I-FP-CIT and 123I-IBZM SPECT for the diagnosis of parkinsonian syndromes: study on 72 patients. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 112, 677–692. [CrossRef]

- Podhorna, J., Krahnke, T., Shear, M., Harrison, J.E., Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, 2016. Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale variants in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease: change over time and the effect of enrichment strategies. Alzheimers Res Ther 8, 8. [CrossRef]

- Pontecorvo, M.J., Devous, M.D., Navitsky, M., Lu, M., Salloway, S., Schaerf, F.W., Jennings, D., Arora, A.K., McGeehan, A., Lim, N.C., Xiong, H., Joshi, A.D., Siderowf, A., Mintun, M.A., 18F-AV-1451-A05 investigators, 2017. Relationships between flortaucipir PET tau binding and amyloid burden, clinical diagnosis, age and cognition. Brain 140, 748–763. [CrossRef]

- Potkin, S.G., Anand, R., Fleming, K., Alva, G., Keator, D., Carreon, D., Messina, J., Wu, J.C., Hartman, R., Fallon, J.H., 2001. Brain metabolic and clinical effects of rivastigmine in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 4, 223–230. [CrossRef]

- Rabinovici, G.D., Jagust, W.J., 2009. Amyloid imaging in aging and dementia: testing the amyloid hypothesis in vivo. Behav Neurol 21, 117–128. [CrossRef]

- Rabinovici, G.D., Rosen, H.J., Alkalay, A., Kornak, J., Furst, A.J., Agarwal, N., Mormino, E.C., O’Neil, J.P., Janabi, M., Karydas, A., Growdon, M.E., Jang, J.Y., Huang, E.J., Dearmond, S.J., Trojanowski, J.Q., Grinberg, L.T., Gorno-Tempini, M.L., Seeley, W.W., Miller, B.L., Jagust, W.J., 2011. Amyloid vs FDG-PET in the differential diagnosis of AD and FTLD. Neurology 77, 2034–2042. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J., Langerman, H., 2019. Alzheimer’s Disease – Why We Need Early Diagnosis. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis 9, 123–130. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, G., Nobili, F., Copello, F., Vitali, P., Gianelli, M.V., Taddei, G., Catsafados, E., Mariani, G., 1999. 99mTc-HMPAO regional cerebral blood flow and quantitative electroencephalography in Alzheimer’s disease: a correlative study. J Nucl Med 40, 522–529.

- Rosen, W.G., Mohs, R.C., Davis, K.L., 1984. A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 141, 1356–1364. [CrossRef]

- Salmon, E., Collette, F., Bastin, C., 2024. Cerebral glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex 179, 50–61. [CrossRef]

- Sanabria Bohórquez, S., Marik, J., Ogasawara, A., Tinianow, J.N., Gill, H.S., Barret, O., Tamagnan, G., Alagille, D., Ayalon, G., Manser, P., Bengtsson, T., Ward, M., Williams, S.-P., Kerchner, G.A., Seibyl, J.P., Marek, K., Weimer, R.M., 2019. [18F]GTP1 (Genentech Tau Probe 1), a radioligand for detecting neurofibrillary tangle tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 46, 2077–2089. [CrossRef]

- Scherfler, C., Nocker, M., 2009. Dopamine transporter SPECT: how to remove subjectivity? Mov Disord 24 Suppl 2, S721-724. [CrossRef]

- Sevigny, J., Chiao, P., Bussière, T., Weinreb, P.H., Williams, L., Maier, M., Dunstan, R., Salloway, S., Chen, T., Ling, Y., O’Gorman, J., Qian, F., Arastu, M., Li, M., Chollate, S., Brennan, M.S., Quintero-Monzon, O., Scannevin, R.H., Arnold, H.M., Engber, T., Rhodes, K., Ferrero, J., Hang, Y., Mikulskis, A., Grimm, J., Hock, C., Nitsch, R.M., Sandrock, A., 2016. The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 537, 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P.F., Gemmell, H.G., Murray, A.D. (Eds.), 2005. Practical nuclear medicine, 3rd ed. ed. Springer, London ; New York.

- Shoghi-Jadid, K., Small, G.W., Agdeppa, E.D., Kepe, V., Ercoli, L.M., Siddarth, P., Read, S., Satyamurthy, N., Petric, A., Huang, S.-C., Barrio, J.R., 2002. Localization of neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid plaques in the brains of living patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 10, 24–35.

- Siger, M., Schuff, N., Zhu, X., Miller, B.L., Weiner, M.W., 2009. Regional myo-inositol concentration in mild cognitive impairment Using 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 23, 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, L., Igel, C., Liv Hansen, N., Osler, M., Lauritzen, M., Rostrup, E., Nielsen, M., Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative and the Australian Imaging Biomarkers and Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing, 2016. Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease using MRI hippocampal texture. Hum Brain Mapp 37, 1148–1161. [CrossRef]

- Sperling, R.A., Aisen, P.S., Beckett, L.A., Bennett, D.A., Craft, S., Fagan, A.M., Iwatsubo, T., Jack, C.R., Kaye, J., Montine, T.J., Park, D.C., Reiman, E.M., Rowe, C.C., Siemers, E., Stern, Y., Yaffe, K., Carrillo, M.C., Thies, B., Morrison-Bogorad, M., Wagster, M.V., Phelps, C.H., 2011. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 280–292. [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y., 2012. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol 11, 1006–1012. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S., 2019. Tau Propagation as a Diagnostic and Therapeutic Target for Dementia: Potentials and Unanswered Questions. Front Neurosci 13, 1274. [CrossRef]

- Talbot, P.R., Lloyd, J.J., Snowden, J.S., Neary, D., Testa, H.J., 1998. A clinical role for 99mTc-HMPAO SPECT in the investigation of dementia? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 64, 306–313. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, Madhavi, Tripathi, Manjari, Damle, N., Kushwaha, S., Jaimini, A., D’Souza, M.M., Sharma, R., Saw, S., Mondal, A., 2014. Differential Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Dementias Using Metabolic Phenotypes on F-18 FDG PET/CT. Neuroradiol J 27, 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.M., Murray, A.D., 2021. Alzheimer’s Dementia: The Emerging Role of Positron Emission Tomography. Neuroscientist 1073858421997035. [CrossRef]

- Vaamonde-Gamo, J., Flores-Barragán, J.M., Ibáñez, R., Gudín, M., Hernández, A., 2005. [DaT-SCAN SPECT in the differential diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease]. Rev Neurol 41, 276–279.

- Valotassiou, V., Malamitsi, J., Papatriantafyllou, J., Dardiotis, E., Tsougos, I., Psimadas, D., Alexiou, S., Hadjigeorgiou, G., Georgoulias, P., 2018. SPECT and PET imaging in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Nucl Med 32, 583–593. [CrossRef]

- Valotassiou, V., Sifakis, N., Papatriantafyllou, J., Angelidis, G., Georgoulias, P., 2011. The Clinical Use of SPECT and PET Molecular Imaging in Alzheimer’s Disease, The Clinical Spectrum of Alzheimer’s Disease -The Charge Toward Comprehensive Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Varghese, T., Sheelakumari, R., James, J.S., Mathuranath, P., 2013. A review of neuroimaging biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Asia 18, 239–248.

- Villemagne, V.L., Burnham, S., Bourgeat, P., Brown, B., Ellis, K.A., Salvado, O., Szoeke, C., Macaulay, S.L., Martins, R., Maruff, P., Ames, D., Rowe, C.C., Masters, C.L., Australian Imaging Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) Research Group, 2013. Amyloid β deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 12, 357–367. [CrossRef]

- Villemagne, V.L., Furumoto, S., Fodero-Tavoletti, M., Harada, R., Mulligan, R.S., Kudo, Y., Masters, C.L., Yanai, K., Rowe, C.C., Okamura, N., 2012. The challenges of tau imaging. Future Neurology 7, 409–421. [CrossRef]

- Villemagne, V.L., Furumoto, S., Fodero-Tavoletti, M.T., Mulligan, R.S., Hodges, J., Harada, R., Yates, P., Piguet, O., Pejoska, S., Doré, V., Yanai, K., Masters, C.L., Kudo, Y., Rowe, C.C., Okamura, N., 2014. In vivo evaluation of a novel tau imaging tracer for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 41, 816–826. [CrossRef]

- Wahlster, P., Niederländer, C., Kriza, C., Schaller, S., Kolominsky-Rabas, P.L., 2013. Clinical assessment of amyloid imaging in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of the literature. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 36, 263–278. [CrossRef]

- Waldemar, G., Walovitch, R.C., Andersen, A.R., Hasselbalch, S.G., Bigelow, R., Joseph, J.L., Paulson, O.B., Lassen, N.A., 1994. 99mTc-bicisate (neurolite) SPECT brain imaging and cognitive impairment in dementia of the Alzheimer type: a blinded read of image sets from a multicenter SPECT trial. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 14 Suppl 1, S99-105.

- Wattamwar, P.R., Mathuranath, P.S., 2010. An overview of biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 13, S116-123. [CrossRef]

- Whitwell, J.L., Josephs, K.A., Murray, M.E., Kantarci, K., Przybelski, S.A., Weigand, S.D., Vemuri, P., Senjem, M.L., Parisi, J.E., Knopman, D.S., Boeve, B.F., Petersen, R.C., Dickson, D.W., Jack, C.R., 2008. MRI correlates of neurofibrillary tangle pathology at autopsy: A voxel-based morphometry study. Neurology 71, 743–749. [CrossRef]

- Wolk, D.A., Klunk, W.E., 2009. Update on amyloid imaging: From healthy aging to Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 9, 345–352. [CrossRef]

- Wong, R., Luo, Y., Mok, V.C., Shi, L., 2021. Advances in computerized MRI-based biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Science Advances 7, 26–43. [CrossRef]

- Wuestefeld, A., Pichet Binette, A., Berron, D., Spotorno, N., van Westen, D., Stomrud, E., Mattsson-Carlgren, N., Strandberg, O., Smith, R., Palmqvist, S., Glenn, T., Moes, S., Honer, M., Arfanakis, K., Barnes, L.L., Bennett, D.A., Schneider, J.A., Wisse, L.E.M., Hansson, O., 2023. Age-related and amyloid-beta-independent tau deposition and its downstream effects. Brain 146, 3192–3205. [CrossRef]

- Xue, C., Kowshik, S.S., Lteif, D., Puducheri, S., Jasodanand, V.H., Zhou, O.T., Walia, A.S., Guney, O.B., Zhang, J.D., Poésy, S., Kaliaev, A., Andreu-Arasa, V.C., Dwyer, B.C., Farris, C.W., Hao, H., Kedar, S., Mian, A.Z., Murman, D.L., O’Shea, S.A., Paul, A.B., Rohatgi, S., Saint-Hilaire, M.-H., Sartor, E.A., Setty, B.N., Small, J.E., Swaminathan, A., Taraschenko, O., Yuan, J., Zhou, Y., Zhu, S., Karjadi, C., Alvin Ang, T.F., Bargal, S.A., Plummer, B.A., Poston, K.L., Ahangaran, M., Au, R., Kolachalama, V.B., 2024. AI-based differential diagnosis of dementia etiologies on multimodal data. Nat Med 30, 2977–2989. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Zhi, W., Wang, L., 2024. Role of Tau Protein in Neurodegenerative Diseases and Development of Its Targeted Drugs: A Literature Review. Molecules 29, 2812. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K., Hata, Y., Ichimata, S., Nishida, N., 2019. Tau and Amyloid-β Pathology in Japanese Forensic Autopsy Series Under 40 Years of Age: Prevalence and Association with APOE Genotype and Suicide Risk. J. Alzheimers Dis. 72, 641–652. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q., Mai, Y., Ruan, Y., Luo, Y., Zhao, L., Fang, W., Cao, Z., Li, Y., Liao, W., Xiao, S., Mok, V.C.T., Shi, L., Liu, J., National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration Neuroimaging Initiative, 2021. An MRI-based strategy for differentiation of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 13, 23. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Arteaga, J., Cashion, D.K., Chen, G., Gangadharmath, U., Gomez, L.F., Kasi, D., Lam, C., Liang, Q., Liu, C., Mocharla, V.P., Mu, F., Sinha, A., Szardenings, A.K., Wang, E., Walsh, J.C., Xia, C., Yu, C., Zhao, T., Kolb, H.C., 2012. A highly selective and specific PET tracer for imaging of tau pathologies. J. Alzheimers Dis. 31, 601–612. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Chen, H., Li, R., Sterling, K., Song, W., 2023. Amyloid β-based therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: challenges, successes and future. Signal Transduct Target Ther 8, 248. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).