1. Introduction

Agriculture sector plays a critical role in the economy of Vietnam, contributing 12% to GDP, employing 27% of the labor force, and is the largest source of income for a significant share of rural households [

1]. Rice is Vietnam’s most important crop, cultivated on over 54% of the agricultural land, provides food security to over 90 % of the population and contributes over 30% of the country’s total agricultural production value [

2]. However, along with those remarkable successes, there are risks of a stagnant situation. The country’s advantages in rice exporting now become less valuable when trade liberalization brings new competitors and other challenges [

3]. In recent decades, the pressure to increase crop yields has raised many concerns. Furthermore, the negative impacts of rice production on environment are challenging, as it is responsible for 48% of the agricultural sector emissions and over 75% of methane emissions [

4]. Reducing emissions from rice cultivation is being raised as an urgent requirement to transformation toward more eco-friendly and sustainable agriculture. In addition, the rice production has been reduced significantly due to the negative effects of rising temperatures, more volatile rainfall, and increasing frequency of severe climate incidents (e.g., droughts, floods, and severe storms) in several regions [

2]. In fact, the agricultural sector is a manufacturing sector that is highly dependent on weather conditions and strongly impacted by extreme weather and climate events. The striking point should be noted that rice has a low profitability for farmers even though it is an important crop in Vietnam for food security and exports [

5]. Long-term monoculture has made farmers heavily reliant on rice farming, thereby reducing their capacity to diversify income sources and making them more vulnerable to market fluctuations. In addition, the efficiency of rice production may be questioned by the trending downward of rice consumption pattern has happened in Vietnam's rural and urban areas, as an inevitable consequence of income growth, urbanization and global integration [

6,

7]. Therefore, promoting high-value crops as alternative to rice can be seen as an urgent need for improving farmer’s income in Vietnam.

Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) is a major horticultural plant that has been widely grown in Southeast Asia, especially China, Thailand, and Vietnam [

8]. Lotus cultivation has been promoted in wetland areas as an ideal substitute to rice farming because of its resilience to floods. Therefore, it is cultivated as a specialty crop in Vietnam and has recently attracted significant attention as a promising commodity with great by-product potentials. Moreover, lotus plays an essential role as an effective strategy to adapt to climate change in the Mekong Delta region, which is known as the rice bowl of Vietnam [

9,

10]. Previous research has highlighted the significant economic benefits of lotus cultivation, particularly its role as an effective flood-based farming system. For instance, studies have shown that lotus crops can provide higher economic efficiency for farmers than rice during the third crop of triple cropping systems in high-dyke areas [

11]. Another study indicated that the integrated rice–lotus farming system generates better returns compared to the traditional double rice cropping system [

10]. Moreover, growing lotus during the flood season not only enhances farmers' income but also provides a sustainable livelihood strategy, as it helps improve soil quality more effectively than intensified rice cultivation [

12].

Despite promising findings from the studies, the role of lotus as an alternative to rice in Vietnam is still not fully understood. Most existing research has been conducted in the Mekong Delta, where favorable conditions such as dyke systems and predictable flooding support lotus cultivation as part of flood-based farming systems. In these areas, lotus is strongly promoted for its economic viability rather than as a coping strategy to the challenges of rice cultivation. In contrast, Central Vietnam is among the most vulnerable regions to extreme weather events such as floods, storms, and droughts, which makes it difficult to adopt the same farming strategies. This contrast raises important questions about the role of lotus, which has recently been promoted as an alternative crop to rice in the region. Therefore, this study aims to address this research gap through a case study of lotus cultivation in Thua Thien Hue Province, Central Vietnam.

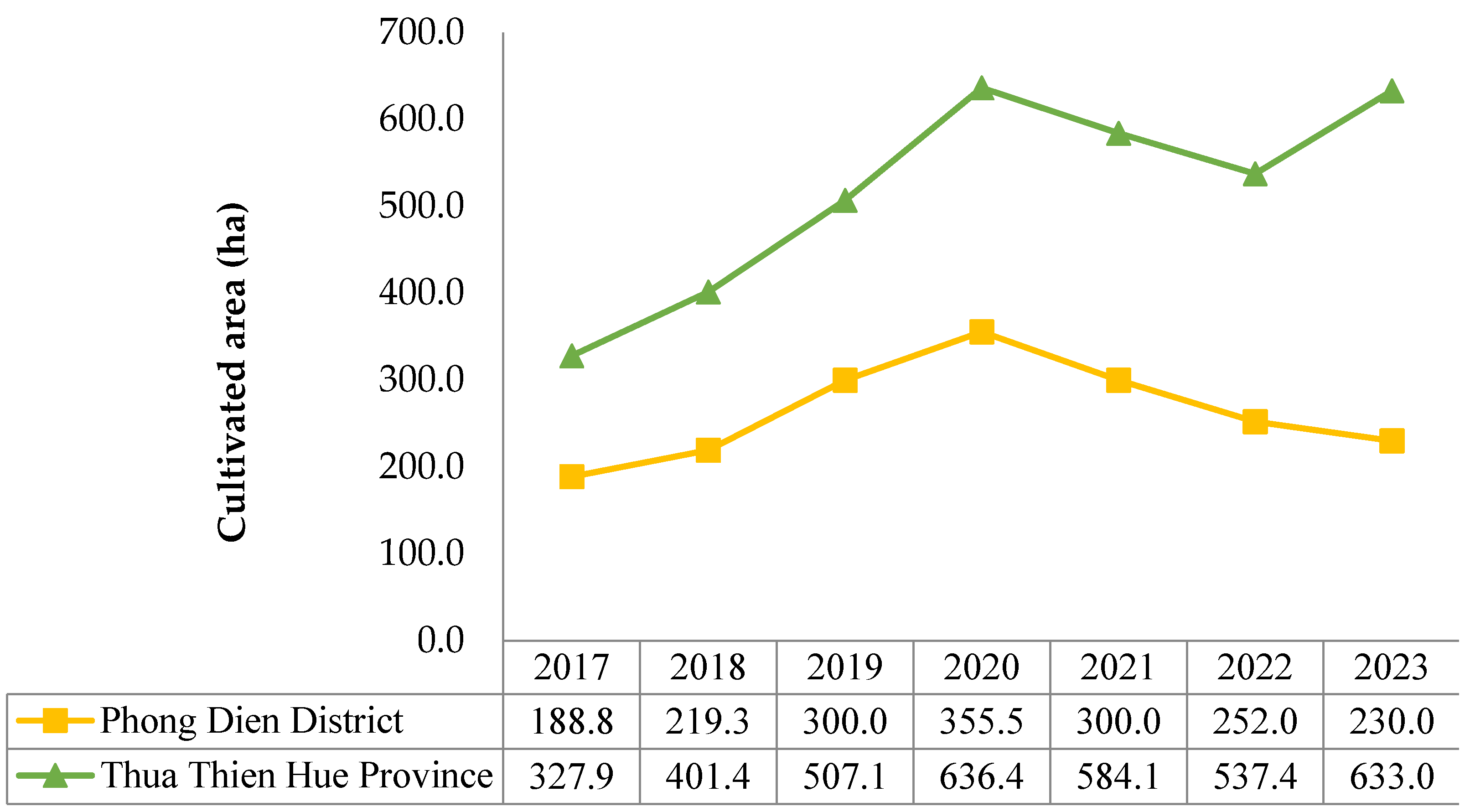

Thua Thien Hue, the largest lotus cultivation region of Central Vietnam, is also known as one of the area’s most susceptible to weather and climatic concerns. The province's high reliance on agricultural production, particularly rice harvests, contributes to its susceptibility as well. In this region, the lotus-growing career has been known for a long time and is being strongly promoted with the expectation to be a high-value crop that is particularly well-adapted to low-lying areas. Lotus production area, reaching 633 hectares for 2023, is sourced by taking abandoned wetland and converting from inefficient rice field areas, especially in lowland, vulnerable, flood-affected areas [

13]. Moreover, lotus is also defined as a specialty crop and promoted to be developed by the local government. This implies that lotus farming has provided a higher potential for adaptation in other wetland regions and low-lying areas that are currently in danger of being abandoned. However, the scale of production is still small, spontaneous, fragmented, and easily vulnerable. Lotus is currently growing at 64 communes and towns that belong to 6 districts and the city of Thua Thien Hue Province. Besides, marketing risks and other production risks of the lotus crop have raised alarming concerns about the sustainable development of the lotus industry.

This study, therefore, aims to identify the performance and contribution of lotus farming, as well as to explore the opportunities and challenges for the sustainable development of the lotus industry in the provincial context by addressing the following research questions:

How has lotus farming been expanded in low-lying areas?

What are the characteristics of lotus cultivation and its contributions to farmers’ income?

What strategies should be adopted to promote lotus cultivation in Thua Thien Hue Province?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Background and Conceptual Framework

2.1.1. Opportunities and Challenges of Alternative Crop Farming

Alternative crops, also known as orphan, abandoned, neglected, lost, underutilized, local, minor, traditional, niche, or underdeveloped crops, are part of a large portfolio of valuable species that are mostly ignored by policymakers, academics, and breeders [

14]. However, these crops have recently attracted significant attention by their critical role as a creative solution for guaranteeing food and nutritional security, particularly in a marginal environment [

15] and as a mean to enhance farm productivity through the diversity of agriculture systems by giving farmers a new cropping choice [

16]. Alternative crops are called so because they are cultivated to replace main staple crops when the productivity and performance of the latter is affected by biotic stresses (salinity, drought, heat, etc.) or abiotic stresses (pests, diseases, etc.), or introduced to new environments where other crops cannot be grown at all [

17]. Farmers also select these crops for their market potential or complementary functions in mixed systems, even if they are not traditionally cultivated in the region. Additionally, value-adding might result in higher-value alternative products and numerous applications for the crop, which will be more sustainable for income diversification, especially when market circumstances no longer seem as viable [

18].

The above definition is widely used in an agricultural context as cultural and newly bred crop species that replace, extend and complement the existing range of crops and contribute to broaden the spectrum of plant production [

19]. It also involves the reintroduction of crops that were previously grown but the output had dropped or interrupted due to poor yields, low quality, changes in technology, or food preferences.

The main benefits of alternative crops have been clearly pointed out in previous research [

14]. Based on this definition, alternative crops are particularly appropriate for marginal environments and problematic soils. However, they also offer high nutritional quality and can satisfy modern dietary demands. Thus, they can contribute to enhance food security at local and regional levels. These crops play an essential role in improving income and livelihood for small-scale farmers and contribute to empowers indigenous communities, especially women by promoting traditional specialties. The wide range of alternative crop species being studied globally illustrates how the scientific community acknowledges their significance in ensuring nutrition security and sustainable food supply. For example, quinoa, teff, tritordeum, sweet potato, chia, camelina and nigella are defined as typical cases of alternative crops in the Mediterranean Basin [

20]. From the producer’ aspect, the introduction of potential alternative crops is also the expansion market opportunities for small scale farmers who cannot improve their total income by producing only staple food crops. Empirical evidences of this function can be found by the success in introduction of alternative crops in many countries such as the case of Andean Grains in Bolivia and Peru [

21] and sugarcane in Thailand [

22]. At the same time, new markets for alternative food products have also been created because of consumer dietary changes. Therefore, alternative crops must be encouraged in order to increase farm profitability and to try to fill the new markets [

23].

Despite these benefits, the use of alternative crops by farmers and consumers is quite insignificant because they are in some way not competitive with other crop species in the same agricultural environment. They are usually grown in small areas and limited to domestically expansion by the characteristic of niche market [

24]. In most of the developing countries, non-staples markets are incredibly underdeveloped on all levels, including traditional local markets, regional markets, and national markets. Extensive efforts by the government to promote the development of staple crops in a long term can be considered as the main cause for this circumstance. However, these crops have attracted the attention of policy makers and scientific communities in recent years due to a wealth of biodiversity, improved security and nutrition. Many countries in Europe and Africa have recognized the importance of these crops and engaged in research on various aspects of these crops for further improvements and development [

14].

In Vietnam, due to cropping patterns of food crops alone giving low returns, a large number of rice farmers now grow other annual crops in conjunction with rice in rural areas [

9,

11,

12] or made adjustments to improve their livelihoods by diversifying their crops or gradually shifting from major food crops to high-value crops [

25,

26,

27]. However, the studies on the contributions of potential alternative crops to rice is still limited and mainly focused on the South of Vietnam. Very few studies, if any, have examined the characteristics of alternative crops in Central Vietnam. Furthermore, data from annual socio-economic reports [

1] indicate that the income and livelihoods of farmers in this region remain heavily dependent on agricultural production, particularly rice cultivation Therefore, a case study with closer looks at how to promote alternative crop as an opportunity to enhance farmer’s income in this region are suggested in order to build up more specific understandings and support the implication of policies in this field.

2.1.2. The Role of Lotus Crop as an Alternative Crop to Rice in Southeast Asia

First, lotus crop has been promoted as a high-value crop in many Asian countries. According to Zhu et al. [

28], lotus plays an essential role as a key agricultural industry in Southeast China, with its cultivation area rapidly increasing, reaching more than 600,000 hectares in 2021. Notably, lotus has long been cultivated as a specialty crop in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River and the lower reaches of the Yellow River in China[

29]. Observations from a case study of reclaimed wetlands surrounding the Pearl River Estuary in China show that three lotus production models demonstrate high economic viability and compete effectively for land use with nearby orchards, aquaculture ponds, and eco-tourism systems [

30]. The economic benefits of lotus cultivation are also highlighted in a case study conducted in Chhattisgarh, India. [

31]. Although lotus is typically cultivated as an annual crop, it can regenerate from underground rhizomes under favorable conditions, reducing the time and effort required from farmers in subsequent growing seasons [

32].

In addition, lotus has been recognized as an important flood-tolerant crop, particularly suitable for cultivation in flood-prone areas where other crops may struggle to survive. According to Jin et al. [

33], lotus utilizes specific microRNAs to regulate its physiological and morphological adaptations under submergence stress, thereby enhancing its tolerance to waterlogged environments. Given its adaptability, lotus presents a promising option for cultivation in wetland areas that are increasingly at risk of abandonment due to negative impacts of climate change such as erratic rainfall and recurrent flooding [

32]. Therefore, lotus farming plays an important role in flood-based farming systems in order to promoting conservation and development of wetland areas in China [

29,

30] and Vietnamese Mekong Delta [

9,

10,

11].

From the nutritional point of view, the beneficial characteristics of this plant, combined with the emerging demand for healthy food, drive its current production. Particularly, as the nutritional value and commodity value of lotus plants, especially lotus seeds, have been widely highlighted through recent studies. Evidence from recent studies suggests that lotus seeds, whether in the form of fresh seeds [

34] or processed flour [

35], have significantly higher protein content than common staples such as wheat, rice, and corn. In addition, their rich composition of high-quality proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, and bioactive compounds supports their potential use as a promising ingredient in functional foods and nutraceuticals [

36].

In conclusion, lotus not only plays a role as an alternative crop because of its good adaptability as a flood-resistant crop for low-lying areas, but also as a crop with high economic value which is potential use for improving farmer’s income and contribution on rural development, especially in extreme weather conditions.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Study Site

Thua Thien Hue is a coastal province in north-central Vietnam, bordered by Laos to the west and the East Sea to the east. It lies within the tropical monsoon zone and is frequently affected by extreme weather events such as floods and typhoons.

Figure 1.

Location of study sites. Source: GADM v4.1 and HDX, map generated using ArcGIS.

Figure 1.

Location of study sites. Source: GADM v4.1 and HDX, map generated using ArcGIS.

Phong Dien is the largest coastal district in Thua Thien Hue Province. It also serves as a major agricultural zone, with 12,581 hectares of farmland, representing 18.55% of the provincial total [

13]. Benefiting from favorable conditions, it has emerged as the province’s leading lotus cultivation area, peaking at 355.5 hectares in 2020 —more than half of the province’s total lotus area. Despite rapid expansion between 2017 and 2020, the lotus-growing area dropped by more than 35% by 2023 (

Figure 2). This notable fluctuation underscores the need to explore its underlying causes, making Phong Dien a relevant and timely case study site.

Lotus is cultivated across all communes of Phong Dien District. For this study, two communes were purposefully selected based on lotus production area, number of lotus-growing households, and their representation of distinct agro-ecological zones. Dien Hoa, located in the coastal lagoon region, has the largest lotus area converted from low-efficiency rice fields. Phong Hien, situated in the inland plain, has long been recognized as a major lotus-producing area, with widespread household participation [

37].

2.2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Data Collection

This research employed a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative and qualitative techniques, including key informant interviews, focus group discussions, household surveys, and in-depth interviews [

38]. A pilot survey was conducted in July 2023 to test the questionnaire and refine the research design, including site selection and sample size. The main fieldwork took place from August to October 2024 through face-to-face interviews with local authorities, experts, lotus farmers, and traders.

Twelve key informants were interviewed, including lotus traders, university experts, and local government officials at both district and commune levels. These interviews explored the characteristics and historical development of lotus farming and collected secondary data from annual reports. Additional insights into market access, price fluctuations, and vertical coordination were gathered through direct interviews with traders in local and wholesale markets. Two focus group discussions were subsequently conducted in the selected communes with five and eight farmer representatives, respectively, to understand farmers’ perspectives, motivations for crop switching, and adaptive strategies. Key points of consensus and disagreement were noted, transcribed, and thematically analyzed to identify patterns across locations and production scales. Participants were selected for their direct involvement and long-term experience with lotus farming. Triangulation was employed to validate findings by comparing perspectives across different stakeholder groups [

39].

Although official statistics are unavailable, estimates from provincial and district agricultural officers suggest that approximately 300 households cultivate lotus across Thua Thien Hue Province, with over 200 located in Phong Dien District (

Table 1). Due to the fragmented nature of lotus cultivation in low-lying areas across communes, household identification is challenging. Therefore, purposive and quota sampling were applied to select households aligned with research objectives and varying in farming experience and production scale. Two communes were purposively selected based on their large lotus-growing areas and high concentration of growers. Within each commune, quota sampling targeted farmers with at least two years of lotus farming experience and differing landholding sizes to explore variations in production scale and adaptive strategies.

Household surveys were conducted with 95 lotus farmers using a semi-structured questionnaire. The survey collected data on socio-demographic characteristics, production practices, and changes in lotus cultivation, including area, yield, and selling price, from 2019 to 2024. The year 2019 was selected as the baseline, as commercial lotus farming expanded rapidly from that time with strong support from local authorities. To reflect differences in production scale, farmers were classified into three groups based on cultivated area: small (<1 ha), medium (1–2 ha), and large (>2 ha).

Twenty in-depth interviews were conducted to complement the quantitative findings. Respondents included eleven farmers who had shifted from rice to lotus, six large-scale producers cultivating lotus on abandoned wetlands, and three farmers who also acted as local collectors. With informed consent, all interviews were recorded, transcribed, and translated for thematic analysis. Each session lasted over an hour and provided insights into farmers’ experiences and strategies

Data Analysis

A one-way ANOVA was applied to test differences in farm characteristics and production costs across farm size groups. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize key features of lotus farming and farmers’ perceptions of crop failure and coping strategies. Benefit-cost analysis was conducted using the following formula:

Financial indicators, including cost, gross output, and profit, were used to assess the economic efficiency of lotus farming. Profit was calculated as:

with

Total costs included rental fees, seedling or cutting costs, fertilizers (both chemical and organic), pesticides, mechanization, irrigation, loans, and labor.

3. Results

3.1. Weather Conditions and Cultivation Period of Rice and Lotus Crop

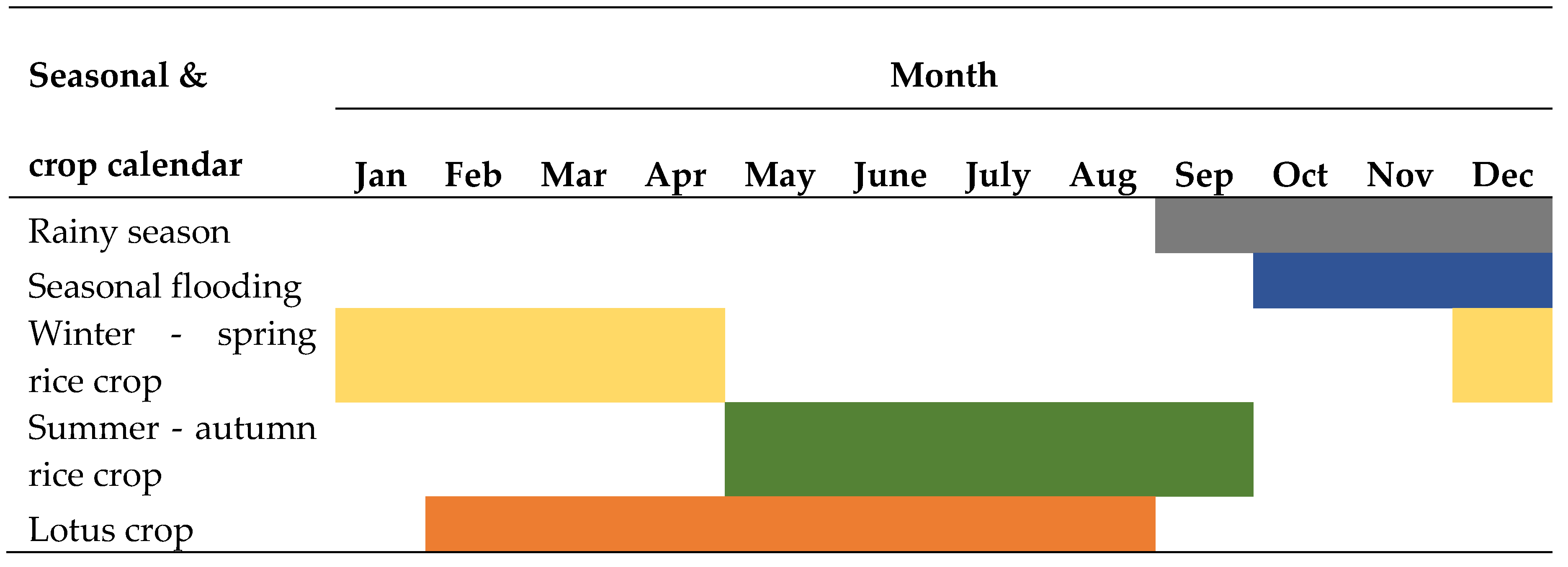

Figure 3 illustrates how seasonal weather patterns affect crop choices and cultivation timing. The rainy and flood season, from September to December, brings intense rainfall, with monthly precipitation reaching up to 1,600 mm, forcing farmers to leave fields fallow. Lotus is cultivated once a year, typically from January to August, with harvesting in July and August. This schedule excludes the second rice crop, requiring farmers to choose between two rice crops and one lotus crop. The absence of crop rotation reflects climatic constraints, unlike in the Mekong Delta, where dyke systems allow year-round lotus cultivation or rotation with rice. In Central Vietnam, lotus is not part of a flood-adaptive farming system but is instead restricted to a short planting window during the dry season.

3.2. Land Sources for Lotus Farming and Land Tenure

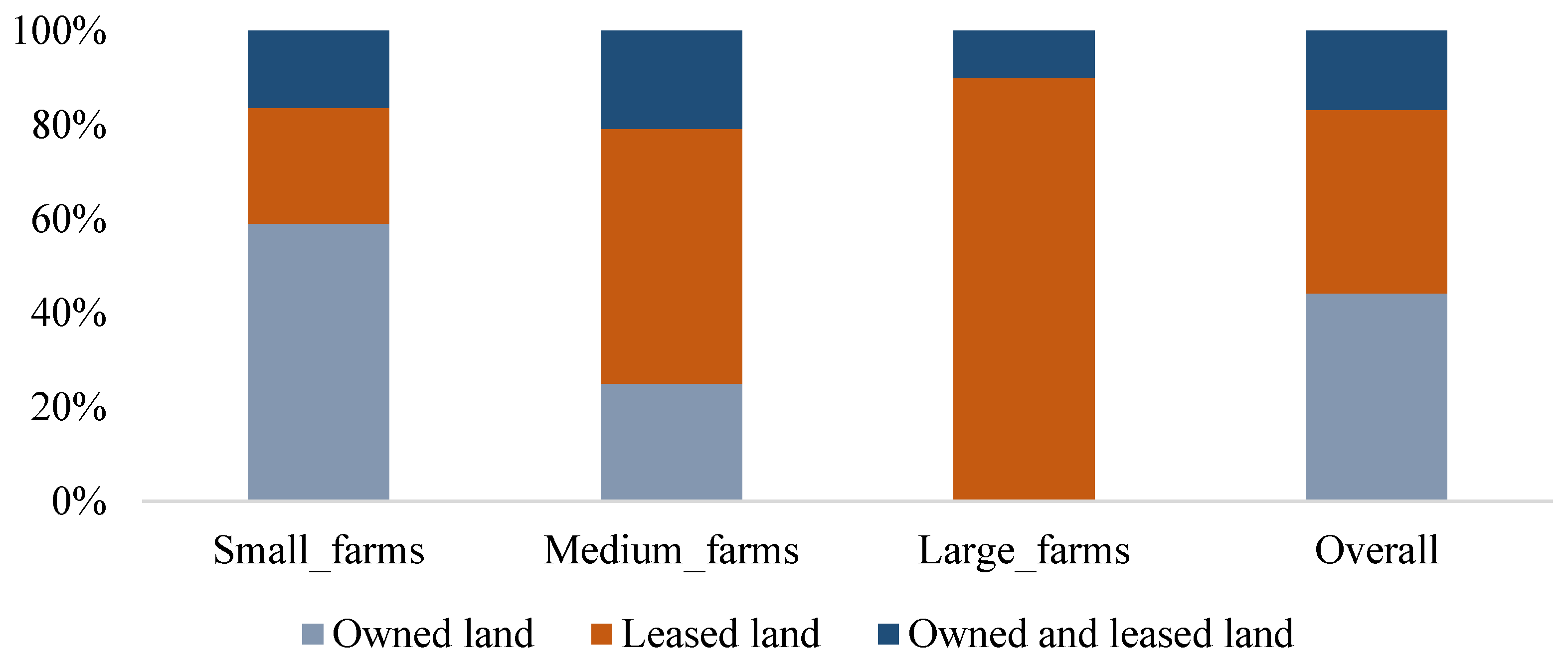

Lotus farming initially emerged as a land-use solution for low-lying areas at risk of abandonment, such as ponds, lakes, and fallow wetlands. However, its reliance on leased land and high initial investment remains a constraint, particularly for smallholders.

Poor drainage, thick mud, and frequent flooding have reduced the viability of rice cultivation in many low-lying areas. These conditions hinder mechanization, forcing farmers to rely on costly manual labor. As a result, many farmers have lost interest in rice cultivation and seek out alternative crops. Lotus is increasingly viewed as a viable alternative due to its tolerance of flooding and wet soil conditions. Its high market value and strong demand further support this transition, which has expanded notably in recent years across vulnerable lowland areas of Thua Thien Hue Province.

Results indicate that land access and the expansion of lotus cultivation are closely linked to crop restructuring policies, which allow farmers to convert inefficient rice fields into high-value alternatives. Since 2013, a national strategy (Decision No. 899/QD-TTg) has promoted agricultural restructuring toward high-value crops. In line with this, the provincial government introduced support policies in 2016 (Decision No. 32/QD-UBND) to encourage rice-to-lotus conversion. Further efforts were outlined in Plan No. 65 (2020), which targets expanding lotus cultivation to 745 hectares by 2025 by promoting conversion from inefficient rice fields and unused low-lying wetlands.

According to the findings, lotus land tenure comprises three forms: owned, leased, and mixed ownership.

Figure 4 presents differences in land tenure by farm size. Small-scale farmers mainly convert part of their own rice fields, while medium- and large-scale producers rely more on leasing. Specifically, 90% of large-scale and 54.17% of medium-scale farms are fully leased, with an additional 10% and 20.83%, respectively, combining leased and owned land.

3.3. Farming Systems, Lotus Varieties and Planting Technique

3.3.1. Farming System

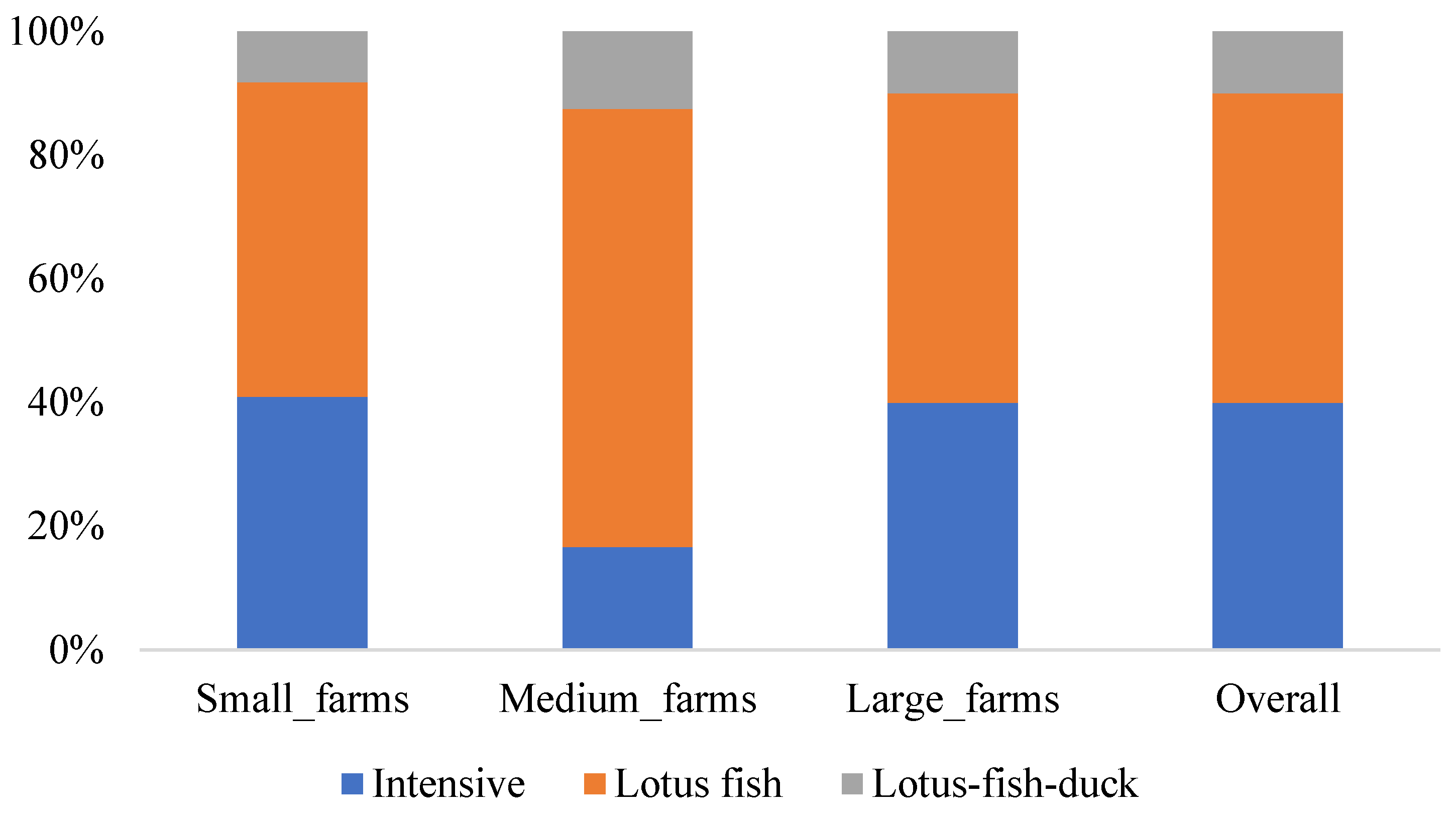

Three lotus-based farming systems are practiced in Phong Dien District: lotus monoculture, lotus–fish, and lotus–fish–duck systems. Among the three, the integrated lotus–fish model is the most widely adopted, practiced by 52.63% of surveyed households and up to 70.83% of those with medium-sized farms. This model provides additional income with minimal labor and technical input, as most farmers neither purchase juvenile fish nor supply extra feed. Fish are raised on a small scale, primarily for home consumption, but still allow households to diversify their outputs from lotus fields without significant investment.

The lotus–fish–duck system, recently introduced in Dien Hoa Commune, offers the highest income potential due to its diversified production. However, it requires more labor and infrastructure to manage both ducks and fish effectively, posing challenges for adoption among smallholder farmers.

3.3.2. Lotus Varieties and Planting Techniques

There are many lotus varieties, each used for different purposes such as seeds, roots, or flowers. Although Hue is renowned for its high-quality local varieties and the "Tinh Tam" brand, these local varieties have become less common in current cultivation practices. Most farmers have shifted to a high-yield variety from Dong Thap Province, primarily cultivated for lotus seed production. This variety is preferred due to its productivity, averaging 2 tons of grain per hectare, approximately twice the yield of local varieties.

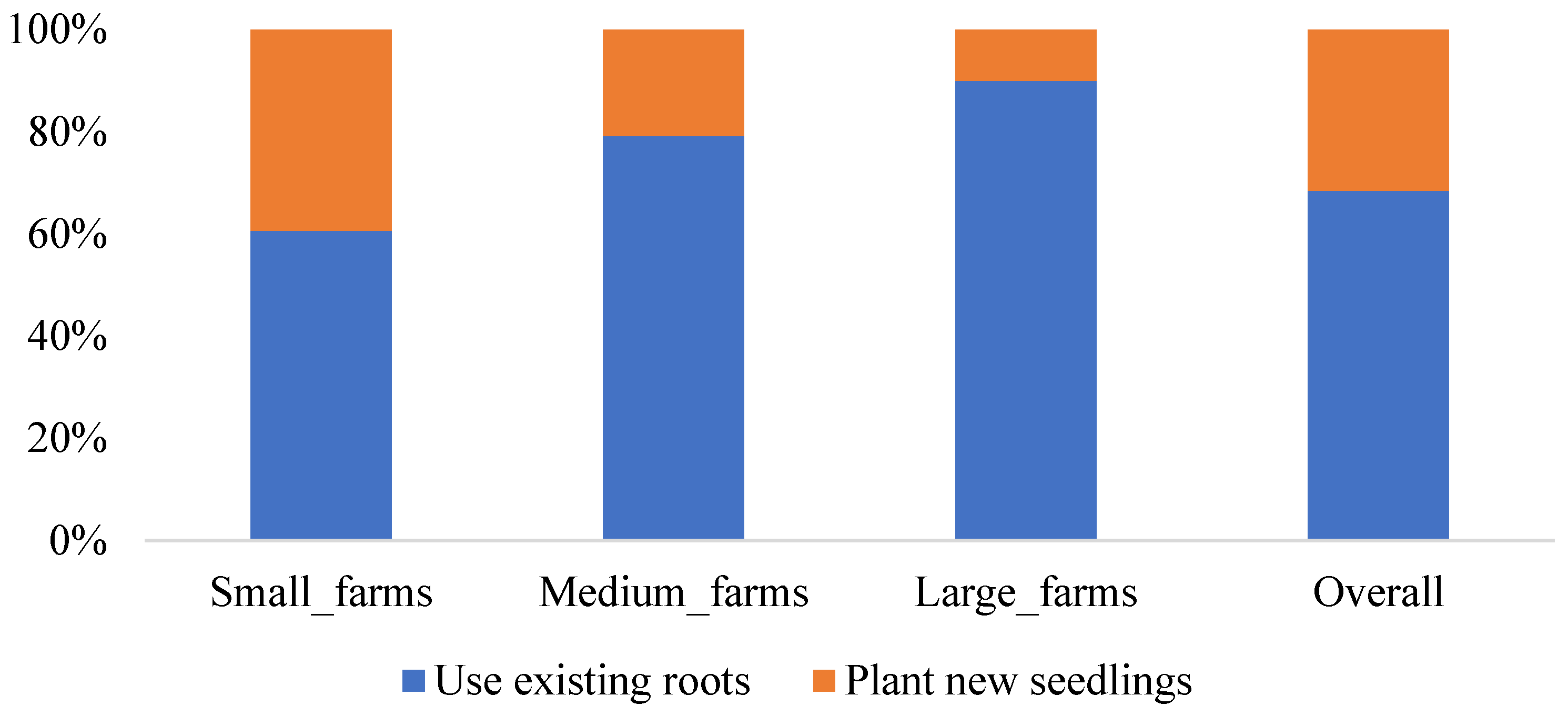

Lotus farmers currently apply two planting techniques: transplanting new seedlings or reusing lotus roots from the previous season. The findings show that 68.42% of farmers reuse existing roots to reduce seedling costs. This method is most common among large-scale producers, followed by medium- and small-scale farms (

Figure 6). If no disease outbreaks occur, farmers often continue this practice for three to five years. However, dependence on old roots increases the risk of soilborne diseases and potential yield reduction.

3.3.3. Market Accessing and Product’s Diversification

Lotus seeds have long been used in traditional cuisine in Thua Thien Hue Province, particularly in soups and specialty desserts. They are mainly consumed fresh or dried and distributed domestically through traders, wholesale markets, and small retail outlets. Although all parts of the lotus plant are edible, product diversification remains limited. Processed lotus seeds sell at two to three times the price of unpeeled seeds, yet most farmers sell them fresh immediately after harvest due to perishability. Limited labor, lack of processing equipment, and restricted market access hinder their ability to add value through post-harvest processing.

3.4. Characteristics of Lotus Farming

To examine lotus farming in the study area, this research compares small, medium, and large-scale households in terms of demographics, cost structure, and production efficiency per hectare.

Table 2 shows no significant differences in family labor, regular labor, off-farm income, or training access. Although early-stage labor demand is low, harvesting is labor-intensive, requiring an average of 2.5 workers per household. Most farmers rely on family labor due to high hiring costs and labor shortages. Larger farms depend more on seasonal labor, incurring higher costs. Harvesting occurs every two days over a period of one to three months, with seeds manually extracted and sold on the same day. Transport costs are minimal, as traders often collect seeds directly at the field or household.

Income diversification was commonly practiced, especially among small-scale growers, to reduce risks associated with reliance on agriculture. Most farmers had access to training on lotus farming techniques provided by the local government. Significant differences were observed in age, education, and farming experience across household groups. Larger-scale producers tend to be younger, better educated, and more experienced. These characteristics are associated with greater adaptability to crop conversion and modern farming practices. Higher income levels among large-scale households suggest stronger financial capacity, enabling further investment in expanding production.

A comparison of total farmland, rice-cultivated land, and lotus acreage reveals clear differences across production scales. Small-scale producers, who represent 64% of surveyed households, cultivate an average of 0.36 hectares of lotus. In contrast, medium- and large-scale producers, comprising 25% and 11% of the sample, manage significantly larger areas, averaging 1.21 and 3.97 hectares, respectively. As production scale increases, so does the share of farmland dedicate to lotus, as well as to rice and other crops. These differences in landholdings reflect broader resource advantages. Larger-scale farmers are more likely to access credit, enabling initial investments and further expansion of lotus cultivation.

3.4. Production Costs and Economic Efficiency

3.4.1. Structure of Production Costs by Three Farm Size Groups

The findings identify four primary cost components in lotus farming: family labor, chemical fertilizer, seedlings, and land rental. Family labor accounts for a significant portion across all production scales, reflecting the high labor demands of lotus cultivation, particularly during the extended harvest season. This makes the model more suitable for households with idle labor, especially male workers. Labor costs, including both family and hired labors, increase noticeably with farm size.

Rental costs vary significantly across household groups. Small-scale farmers mainly access farmland by converting from their own rice fields, whereas large-scale farmers expand their farmland by leasing. Consequently, the rental cost increases with production scale.

There are no significant differences in seedling and chemical fertilizer costs across household groups. Seedling costs average 6 million VND per hectare, covering 400 cuttings, transportation, and planting labor. Most farmers source cuttings from wholesalers. Due to the high cost and its substantial share of total expenses, many households opt to reuse lotus roots from the previous season (

Figure 6). Fertilizer expenditure averages 8 million VND, primarily for NPK, applied three times per season at 450 kg per hectare. Other costs, such as organic fertilizer, machinery rental, pesticides, irrigation, and interest payments, represent a small portion and show little variation among groups.

In general, the cost of lotus cultivation per hectare is relatively high, averaging 40 million VND per hectare. This cost gradually increases with production scale, reaching an average of 34 million VND for small-scale households, 45 million VND for medium-scale households, and 65 million VND for large-scale households.

3.4.1. Economic Analysis of Lotus Production

Lotus seed is a more profitable crop than rice in terms of market access and financial returns. Although the selling price of lotus seeds fluctuates significantly between early, mid, and late harvest season, the average price remains high. The table indicates an upward trend in the selling price of lotus seeds from 2019 to 2024. A similar trend is observed for rice, however, the price gap between lotus seeds and rice remains substantial. Fresh unpeeled lotus seeds can be sold at a price up to five times higher than rice.

Table 4.

Change in selling price of lotus and rice grain.

Table 4.

Change in selling price of lotus and rice grain.

| Year |

Unpeeled lotus seed

(thousand VND/kg) |

Rice grain

(thousand VND/kg) |

Lotus/Rice Ratio |

| 2019 |

31.53 ± 2.67 |

5.74 ± 0.53 |

5.49 |

| 2020 |

34.52 ± 8.60 |

5.93 ± 0.54 |

5.82 |

| 2021 |

34.32 ± 3.14 |

6.22 ± 0.67 |

5.51 |

| 2022 |

37.31 ± 5.67 |

6.77 ± 0.53 |

5.52 |

| 2023 |

40.94 ± 4.09 |

7.55 ± 0.53 |

5.43 |

| 2024 |

48.73 ± 3.58 |

8.48 ± 0.40 |

5.75 |

Although differences in yield and gross output are not statistically significant, the data indicates that large-scale farms have the highest average yield and gross production, while medium farms have the lowest values. Due to lower production costs, small-scale farmers achieve greater economic efficiency, as reflected in significantly higher net income and benefit-cost ratios. In contrast, higher labor and rental expenses result in negative profitability for medium- and large-scale households.

The findings suggest that reducing production costs, particularly labor expenses, is essential for improving the profitability of medium- and large-scale farms. Enhancing labor efficiency and minimizing inputs could support their financial viability. In contrast, low net profits among small-scale farmers are primarily linked to limited yields. Addressing yield constraints through targeted interventions is crucial to strengthen the economic viability of lotus farming.

Table 5.

Economic efficiency of lotus farming by farm size groups.

Table 5.

Economic efficiency of lotus farming by farm size groups.

| Variable |

Farm size group |

Overall |

P_value1

|

| Small |

Medium |

Large |

|

|

| Yield (ton/hectare) |

0.89 |

0.75 |

1.03 |

0.87 |

0.44 |

| Selling Price (thousand VND/kg) |

49.41 |

47.71 |

47.00 |

48.73 |

0.04* |

Gross Output

(mil.VND/hectare) |

43.63 |

35.74 |

47.63 |

42.06 |

0.46 |

| Total costs (mil.VND/hectare) |

34.02a

|

45.65b

|

64.83c

|

40.20 |

0.00* |

| Profit (mil.VND/hectare) |

9.61a

|

-9.91b

|

-17.20b

|

1.86 |

0.00* |

| Benefit-cost ratio |

0.28a

|

-0.22b

|

-0.27 |

0.05 |

0.01* |

| No. of observations |

61 |

24 |

10 |

95 |

|

3.4. Crop Failure and Farmer’s Perspective

3.4.1. Change in Acreage and Yield of Lotus Crop from 2019-2024

Results from

Table 6 reveal contrasting trends between the expansion of lotus cultivation and declining productivity among surveyed households from 2019 to 2024. The number of growers and the average area under lotus have steadily increased. However, yields remain low and have continued to decline throughout the period. This recurring underperformance raises concerns about the suitability of the high-yield variety, whose popularity is driven mainly by its perceived yield potential.

Several environmental and agronomic factors have contributed to the decline in lotus productivity and farm income. Most respondents identified extreme weather events, including heavy rainfall, unseasonal flooding, prolonged drought, and high temperatures, as the main causes of crop failure. Prolonged heat stress was reported to reduce yields, while excessive rainfall and flooding during the harvest period led to substantial losses. In addition to climatic challenges, soilborne diseases have become a major constraint in recent years. More than 90% of farmers reported that nematode infestations pose the greatest threat to their lotus fields.

“Once Nematode disease breaks out, I generally accepted the loss of the entire crop. Even when I replanted, the lotus crop loss continued. We are just hoping for a cure for this disease." Interview with a farmer at Phong Hien commune.

"Nematode disease is the main cause of crop failure and the reduction in lotus cultivation in our commune. Despite numerous visits from university research teams, the agricultural department, and the provincial agriculture office to seek solutions, no effective method has been found to manage and control this disease in lotus plants." Interview agricultural officer at Phong Hien commune.

3.4.1. Farmers Motivations and Their Intentions on Continuing Lotus Farming

Although farmers typically abandon crops after repeated failures, most farmers who experienced at least one failed lotus crop in the past five years still intended to continue cultivation. This decision is driven by two main reasons:

Firstly, all respondents identified profit expectations as their main motivation for switching to lotus farming. Despite production risks, lotus is perceived to offer significantly higher returns than rice, making its income potential a key factor sustaining farmers’ commitment to the crop.

“Agricultural production mainly depends on the weather, no matter which crop you choose to cultivate, you have to accept the risk of crop failure. There is no crop that is more profitable than lotus; a successful crop can cover losses of three previous crops. As long as I continue to grow lotus, I still have a chance to get back the money I lost”. Interview with a farmer at Phong Hien commune, Phong Dien district.

Secondly, the challenges that initially motivated farmers to switch from rice to lotus, such as limited mechanization in low-lying areas, have become barriers preventing them from returning to rice cultivation.

“My farmland is in a low-lying area, making rice cultivation very difficult because plow and harvester can’t be used. My spouse and I are also getting older, therefore, if we don’t grow lotus, we will likely leave the land fallow rather than continue farming on it”. Interview with a farmer at Dien Hoa commune, Phong Dien district.

4. Discussion

Lotus is widely regarded as a flood-tolerant and climate-adaptive crop in flood-prone regions. This perception is supported by studies from the Mekong Delta in Vietnam and the Yangtze River basin in China. However, the case study in Thua Thien Hue provides a contrasting perspective on its role as an alternative to rice in regions with harsher climate variability. According to Nohara & Tsuchiya [

40] and Deng et al. [

41], lotus is known for its flood tolerance, but this capacity is limited. Most cultivars cannot survive submergence beyond two to three meters or ten days, leading to growth reduction or mortality. Similarly, Wang et al. [

42] reported that prolonged inundation causes physiological stress and yield decline in lotus. The erratic and intense rainy season at the study site restricts lotus to a single annual crop, with no room for crop rotation. As a result, instead of supporting climate adaptation, lotus cultivation may heighten exposure to production risks and crop failure, particularly in low-lying areas. Nonetheless, lotus is still considered by both farmers and local authorities as a practical alternative to rice, primarily due to its potential to address structural limitations in lowland rice farming systems, where paddy land faces an increasing risk of abandonment. This perception stems from the fact that difficulties in mechanization, high labor costs, and declining soil quality have made rice cultivation increasingly unsustainable in these areas. This makes lotus, despite its agronomic limitations, a more compatible option under local conditions and a means to sustain land use where rice farming is no longer viable. This finding reframes the role of alternative crops in extreme climate conditions, highlighting their function not as inherently climate-resilient solutions, but as a practical response to the production challenges of existing farming systems. In this context, with appropriate support, lotus cultivation holds potential to contribute both economically and ecologically to sustainable land use in flood-prone areas.

Hue lotus seeds fetch a price premium in local markets despite challenging natural conditions, due to their limited seasonal availability and single annual harvest. These favorable market conditions have strengthened farmers’ interest in lotus cultivation as a potential alternative to rice in lowland areas. In 2024, lotus farming did not generate positive returns for most surveyed households, especially among medium- and large-scale producers. Nonetheless, all farmers expressed an intention to continue cultivation. Their continued engagement reflects not only the potential for higher income under favorable conditions, but also the crop’s compatibility with underutilized land. Additional factors such as low labor requirements in the early stages, sustained land use, and alignment with local policy incentives further support this choice. These findings suggest that in adopting alternative crops, farmers prioritize long-term expectations and land-use considerations over short-term profitability.

All surveyed households currently cultivate the high-yield lotus variety from Dong Thap, based on the belief that it offers superior yields compared to indigenous varieties. Nonetheless, continued crop failures in recent years have raised concerns about the adaptability and disease resistance of this variety under local weather and soil conditions. Nematode infestation has become a major constraint to lotus cultivation. It caused serious losses in Tokushima, Japan [

43], and led to widespread crop failure in Dong Thap Province in 2018 [

10]. No effective control measures have yet been identified, leaving farmers highly vulnerable to future outbreaks. The adoption of continuous monoculture and the use of existing roots from previous seasons may increase vulnerability to soil-borne diseases and reduce yields. Wu et al. [

44] found that consecutive monoculture practices led to the accumulation of pathogenic plant viruses in the soil, thereby heightening the risk of soilborne disease outbreaks. To address these challenges, more attention should be directed toward researching the potential of indigenous lotus varieties, which have been largely overlooked in recent years. In addition to being valuable genetic resources, local cultivars have demonstrated superior nutritional quality. For instance, lotus seeds from Hue varieties such as Vinh Thanh, Phu Mong, and Gia Long pink lotus have been shown to surpass the high-yield variety in nutritional value [

45]. However, their cultivation remains limited, accounting for less than 10% of the province’s total lotus area [

13]. Further research is needed to assess their agronomic performance and resilience to climate stress and soilborne diseases. Promoting indigenous varieties as specialty crops could enhance product differentiation, strengthen the Hue lotus brand, and add value across the supply chain. This represents a promising strategy for advancing sustainable alternative crops in environmentally vulnerable areas, beyond the case of lotus in Thua Thien Hue.

High labor costs continue to pose a major barrier to scaling up and improving the efficiency of lotus farming. As harvesting is labor-intensive and cannot be mechanized, production costs increase with scale, resulting in the paradox that larger farms may become less cost-effective. This trend was also observed by C. V. Nguyen et al. [

46], who found that small-scale farmers, benefiting from lower labor costs, were better able to diversify and achieve higher economic efficiency. While lotus cultivation has been promoted as a response to labor shortages and mechanization challenges in lowland rice systems, its advantages are most apparent among smallholders who can draw on family labor for harvesting. These findings underscore the importance of policy support to promote context-appropriate mechanization, reduce production costs, and enhance efficiency. In addition, strengthening farmer cooperatives and investing in post-harvest innovations could further improve the scalability and competitiveness of lotus farming.

5. Conclusions

The study highlights several features of lotus farming in Phong Dien District, Thua Thien Hue Province. Land conversion from inefficient rice fields has been a key driver of its expansion, driven by limited mechanization, high labor costs, and frequent flooding. Lotus, promoted as a high-value crop suited to low-lying areas, has gained traction under supportive land policies.

Although lotus farming has been actively promoted in recent years, it is still limited in scale. High labor and rental costs remain key obstacles to expansion, particularly for large-scale producers who are constrained by seasonal labor shortages and heavy reliance on manual work. In contrast, lower input costs support higher efficiency among small-scale farms. Improving labor productivity and reducing costs are essential to enhancing overall economic viability.

One of the main challenges in lotus farming is recurring crop failure and declining yields, which led to substantial economic losses in 2024, particularly among medium- and large-scale producers. Farmers attributed these outcomes to extreme weather events and the spread of soil-borne diseases. These findings underscore the need to improve lotus seedling quality, varietal selection, and planting techniques, which currently rely heavily on high-yield cultivars and reused roots. Priority should be given to developing climate-resilient indigenous varieties and establishing reliable seedling systems to ensure planting material quality and reduce input costs. Addressing labor shortages through mechanization, cooperative models, and post-harvest innovations is also essential to enhance productivity, reduce risks, and ensure the long-term sustainability of lotus farming in lowland areas.

One limitation of this study is the lack of comparison between indigenous and high-yield lotus varieties. The scattered distribution of growers and limited data on those cultivating local varieties restricted access to this group. Further research is needed to better understand the role and potential of indigenous lotus varieties in diverse production environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.T.T., P.B., and P.L.; methodology, T.T.D., H.T.M.H., and H.A.; software, T.T.D., H.A., and H.T.M.H.; validation, H.T.M.H., P.B., and P.L.; formal analysis, T.T.D., H.A., and P.L.; investigation, T.T.D.; writing—original draft, T.T.D.; supervision, Q.T.T., P.B., and P.L.; project administration, Q.T.T., P.B., and P.L.; funding acquisition, Q.T.T., P.B., and P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Wallonia-Brussels International (WBI) Belgium, through the Bilateral Cooperation Agreement Wallonia–Brussels / Vietnam, 2022–2024 – Project 7.2: “Capacity building in training and research to mitigate the impacts of climate change in the sandy coastal areas of Central Vietnam”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved only voluntary socio-economic data collection through interviews and group discussions. No medical or health-related procedures were involved. According to national regulations, ethical approval is not legally required for non-medical socio-economic research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data related to the present study will be available upon request for any interested party.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the officers, traders, and farmers in Phong Dien District for their patience and cooperation during our field trips, and for generously providing valuable data that contributed significantly to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- General Statistics Office of Vietnam, “General Statistics Office of Vietnam.” Accessed: Mar. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.gso.gov.vn/.

- World Bank, Spearheading Vietnam’s Green Agricultural Transformation: Moving to Low-Carbon Rice. World Bank, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. H. H. Bui and Q. Chen, “An Analysis of Factors Influencing Rice Export in Vietnam Based on Gravity Model,” J Knowl Econ, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 830–844, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- I. Goli, M. Omidi Najafabadi, and F. Lashgarara, “Where are We Standing and Where Should We Be Going? Gender and Climate Change Adaptation Behavior,” J Agric Environ Ethics, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 187–218, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H.-T.-M. Nguyen, H. Do, and T. Kompas, “Economic efficiency versus social equity: The productivity challenge for rice production in a ‘greying’ rural Vietnam,” World Development, vol. 148, p. 105658, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Bairagi, S. Mohanty, S. Baruah, and H. T. Thi, “Changing food consumption patterns in rural and urban Vietnam: Implications for a future food supply system,” Aus J Agri & Res Econ, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 750–775, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T.-T. Nguyen, T. T. Nguyen, and U. Grote, “Credit, shocks and production efficiency of rice farmers in Vietnam,” Economic Analysis and Policy, vol. 77, pp. 780–791, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Lin, C. Zhang, D. Cao, R. N. Damaris, and P. Yang, “The Latest Studies on Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera)-an Emerging Horticultural Model Plant,” IJMS, vol. 20, no. 15, p. 3680, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Tran, G. Van Halsema, P. J. G. J. Hellegers, F. Ludwig, and C. Seijger, “Stakeholders’ assessment of dike-protected and flood-based alternatives from a sustainable livelihood perspective in An Giang Province, Mekong Delta, Vietnam,” Agricultural Water Management, vol. 206, pp. 187–199, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. T. M. Vo, G. Van Halsema, P. Hellegers, A. Wyatt, and Q. H. Nguyen, “The Emergence of Lotus Farming as an Innovation for Adapting to Climate Change in the Upper Vietnamese Mekong Delta,” Land, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 350, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Tran, G. Van Halsema, P. J. G. J. Hellegers, F. Ludwig, and A. Wyatt, “Questioning triple rice intensification on the Vietnamese mekong delta floodplains: An environmental and economic analysis of current land-use trends and alternatives,” Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 217, pp. 429–441, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Tran et al., “Advancing sustainable rice production in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta insights from ecological farming systems in An Giang Province,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 17, p. e37142, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Thua Thien Hue Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, “Agricultural production report 2023,” Thua Thien Hue Province, 2023.

- A. Pradhan, J. Rane, and H. Pathak, “Alternative Crops for Augmenting Farmers’ Income in Abiotic Stress Regions,” CAR-National Institute of Abiotic Stress Management, Baramati, Pune, Maharashtra, vol. Technical Bulletin No. 29., p. 26, Feb. 2021.

- I. Elouafi, M. A. Shahid, A. Begmuratov, and A. Hirich, “The Contribution of Alternative Crops to Food Security in Marginal Environments,” in Emerging Research in Alternative Crops, vol. 58, A. Hirich, R. Choukr-Allah, and R. Ragab, Eds., in Environment & Policy, vol. 58., Cham: Springer International Publishing. 2020; pp. 1–23. [CrossRef]

- A. Mavroeidis, I. Roussis, and I. Kakabouki, “The Role of Alternative Crops in an Upcoming Global Food Crisis: A Concise Review,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 22, p. 3584, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Hirich, R. Choukr-Allah, and R. Ragab, Eds., Emerging Research in Alternative Crops, vol. 58. in Environment & Policy, vol. 58. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Isleib, “Exploring alternative field crops,” Michigan State University Extension, East Lansing, MI, Jun. 2012, Accessed: Mar. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/exploring_alternative_field_crops.

- P. Konvalina, Ed., Alternative Crops and Cropping Systems. InTech. 2016. [CrossRef]

- I. Kakabouki et al., “Introduction of alternative crops in the Mediterranean to satisfy EU Green Deal goals. A review,” Agron. Sustain. Dev., vol. 41, no. 6, p. 71, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Padulosi, K. Amaya, M. Jäger, E. Gotor, W. Rojas, and R. Valdivia, “A Holistic Approach to Enhance the Use of Neglected and Underutilized Species: The Case of Andean Grains in Bolivia and Peru,” Sustainability, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 1283–1312, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Suchato, A. Patoomnakul, and N. Photchanaprasert, “Alternative cropping adoption in Thailand: A case study of rice and sugarcane production,” Heliyon, vol. 7, no. 12, p. e08629, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Karelakis and G. Tsantopoulos, “Changing land use to alternative crops: A rural landholder’s perspective,” Land Use Policy, vol. 63, pp. 30–37, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Kumar and P. Bhalothia, “Orphan crops for future food security,” J Biosci, vol. 45, no. 1, p. 131, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Kaveney et al., “Inland dry season saline intrusion in the Vietnamese Mekong River Delta is driving the identification and implementation of alternative crops to rice,” Agricultural Systems, vol. 207, p. 103632, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. T. Le, N. H. Mao, P. Kristiansen, and M. Coleman, “Innovation in two contrasting value chains: Constraints and opportunities for adopting alternative crop production in the Vietnamese Mekong River Delta,” Regional Sustainability, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 100198, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. H. L. Le, P. Kristiansen, B. Vo, J. Moss, and M. Welch, “Understanding factors influencing farmers’ crop choice and agricultural transformation in the Upper Vietnamese Mekong Delta,” Agricultural Systems, vol. 216, p. 103899, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, K. Deng, P. Wu, K. Feng, S. Zhao, and L. Li, “Effects of Slow-Release Fertilizer on Lotus Rhizome Yield and Starch Quality under Different Fertilization Periods,” Plants, vol. 12, no. 6, p. 1311, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. B. Guo, “Cultivation of lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. ssp. nucifera) and its utilization in China,” Genet Resour Crop Evol, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 323–330, May. 2009. [CrossRef]

- H.-F. Lu et al., “Integrated emergy and economic evaluation of lotus-root production systems on reclaimed wetlands surrounding the Pearl River Estuary, China,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 158, pp. 367–379, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Rajeshwari Sahu and S. S. Chandravanshi, “Lotus Cultivation under Wetland: A Case Study of Farmers Innovation in Chhattisgarh, India,” International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 2018.

- A. Jain, R. Singh, and H. Singh, “Economic evaluation of lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn) cultivation in Sanapat lake, Manipur valley,” Natural Product Radiance, vol. 3, pp. 418–421, Jan. 2004.

- Q. Jin et al., “Identification of Submergence-Responsive MicroRNAs and Their Targets Reveals Complex MiRNA-Mediated Regulatory Networks in Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn),” Front. Plant Sci., vol. 8, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Shad, H. Nawaz, F. Siddique, J. Zahra, and A. Mushtaq, “Nutritional and Functional Characterization of Seed Kernel of Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera): Application of Response Surface Methodology,” FSTR, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 163–172, 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. Sopawong, D. Warodomwichit, W. Srichamnong, P. Methacanon, and N. Tangsuphoom, “Effect of Physical and Enzymatic Modifications on Composition, Properties and In Vitro Starch Digestibility of Sacred Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) Seed Flour,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 16, p. 2473, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Punia Bangar, K. Dunno, M. Kumar, H. Mostafa, and S. Maqsood, “A comprehensive review on lotus seeds (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.): Nutritional composition, health-related bioactive properties, and industrial applications,” Journal of Functional Foods, vol. 89, p. 104937, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Phong Dien District Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, “Anual Agricultural production report,” 2023.

-

S. N. Hesse-Biber, Mixed methods research: merging theory with practice; Guilford Press: New York, NY, 2010.

- N. Carter, D. Bryant-Lukosius, A. DiCenso, J. Blythe, and A. J. Neville, “The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research,” Oncology Nursing Forum, vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 545–547, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Nohara and T. Tsuchiya, “Effects of water level fluctuation on the growth of Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. in Lake Kasumigaura, Japan,” Ecological Research, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 237–252, Aug. 1990. [CrossRef]

- X. Deng et al., “Time-course analysis and transcriptomic identification of key response strategies of Nelumbo nucifera to complete submergence,” Horticulture Research, vol. 9, p. uhac001, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Wang et al., “Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of submerged lotus reveals cooperative regulation and gene responses,” Sci Rep, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 9187, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Koyama, S. P. Thar, C. Kizaki, K. Toyota, E. Sawada, and N. Abe, “Development of specific primers to Hirschmanniella spp. causing damage to lotus and their economic threshold level in Tokushima prefecture in Japan,” Nematol, vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 851–858, 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. Wu et al., “Consecutive monoculture regimes differently affected the diversity of the rhizosphere soil viral community and accumulated soil-borne plant viruses,” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, vol. 337, p. 108076, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Q. Trang, H. K. Hồng, and Đ. T. Long, “NGHIÊN CỨU THÀNH PHẦN DINH DƯỠNG VÀ KHẢ NĂNG CHỐNG OXY HÓA CỦA MỘT SỐ GIỐNG SEN HỒNG TRỒNG Ở TỈNH THỪA THIÊN HUẾ,” HueUni-JNS, vol. 128, no. 1E, pp. 153–162, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. V. Nguyen, M. Abwao, H. V. Nguyen, and H. D. Hoang, “Barriers to agricultural products diversification: An empirical analysis from lotus farming in Central Vietnam,” Rural Sustainability Research, vol. 50, no. 345, pp. 103–111, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).