1. Introduction

Globally coral reefs are threatened with an increasing array of deleterious processes [

1] despite the implementation of beneficial management actions such as fishing exclusion [

2,

3,

4]. Processes, including ocean acidification, thermal stress, cyclones, disease and

Acanthaster sp. outbreaks, continually reduce coral cover [

5,

6,

7,

8]. However corals are able to create vast structures when conditions are favorable [

9].

Management agencies, such as the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, are already actively implementing policies to ameliorate pressures to support coral resilience to a changing climate [

4,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, long-term monitoring records from around the world indicate that current actions to manage chronic stressors, such as fishing pressure and water quality, are not enough on their own to prevent significant declines of coral reef ecosystems [

6,

15]. Each coral reef is exposed over time to a set of complex processes that are stochastic in magnitude and frequency [

16,

17]. Identification of the extent and magnitude of these stochastic pressures is the subject of extensive resilience research that aims to targeted supplementary management actions to support coral reef growth and recovery [

14,

18,

19].

Marine Science graduate understanding of the complexity associated with coral reef growth, in the face of natural environmental perturbations and anthropogenic stresses, is essential for ongoing support of management actions to support reef resilience [

20,

21]. Unfortunately, the intricate network of stochastic perturbations that are a natural feature of ecology, already present a significant communication and educational challenge [

22] for the agencies that are responsible for coral reef management [

23]. The educational challenges are amplified further by the future uncertainty due to the inherent model predictions [

24].

In particular, the description of how a coral reef ecosystem will undergo long-term state changes, as a function of sporadic pressures, is confusing. Rapid climate change means that the patterns of environmental conditions, already familiar to the public, are predicted to change significantly in the coming decades (Fischhoff, 2011). Informed managers plan for that change and identify strategies to support the processes that underpin coral reef health and resilience [

10,

25,

26]. Communicating this mix of long term strategies in the context of publicized short-term events such as coral bleaching and cyclone damage is difficult with existing tools [

27,

28]. Visual displays, such as hysteresis curves, are not effective dissemination tools for educational purposes [

28]. Creating awareness of the issues that face coral reef managers while continuing to operate in a stochastic environment is essential for effective long-term implementation of resilience strategies [

29]. Climate change will not result in a smooth regular transition [

30] from one state to another state for all coral reefs [

31], consequently, for any single coral reef the growth and decay trajectory can be seen as a game of chance within an environment of positive and negative influences.

Games of this type are prolific in the public domain (Landers 2015) and the rules and strategies are widely understood. Games like GREENIFY [

32], REEFGAME [

33] and KEEP COOL [

34] specifically target environmental change and attempt to motivate action based on a large-scale holistic approach. A popular board game called Snakes and Ladders (also marketed as Chutes and Ladders) incorporates the magnitude and frequency of both deleterious (snakes) and beneficial (ladders) events that are experienced as a function of chance (dice roll). Additionally the concept, that some players can proceed to the top of the board (considered to be the state of Nirvana in the original Indian game) while others might oscillate at a lower level, is understood to be a combination of board configuration and lucky moves [

35]. The simplicity of this game means that all players understand that skill plays no part in the success and that every player has a chance to win.

The Snakes and Ladders game can also be applied to scientific modelling of ecological systems. The game can be modelled as an absorbing Markov chain system such that a matrix defining the probability of moving from any location to any other for a given board configuration can be described [

35]. The state of the system can therefore be predicted for a large number of game plays given the configuration of the snakes and ladders.

The University of South Pacific third year course on Coral reef ecology and Management (MS306) has the relevant intended learning outcomes (ILO) listed; describe the ecology of coral reef habitats, assess human uses, values and major threats affecting coral reefs, and evaluate different coral reef management and conservation strategies. These learning outcomes cover a range of ecological topics with the general approach of providing students with deep understanding of the fundamental driving processes in coral reefs. Implementing educational strategies where the model behaviour is complex and uncertain requires a new understanding of ecological processes combined with dynamic appreciation of the environmental circumstances. In many cases there are not definable rules but rather an appreciation of the inherent complexity of time and space interactions that dominate marine ecology. Students, therefore, require an emergent approach that reflects the ILOs. Students are consequently exposed to the experience of ecological change without a formative basis so that reflective learning can be optimally introduced.

Translating this participatory game to the marine world for principally educational and communication purposes, we transform the fundamental elements of the Snakes and Ladders game to represent coral reef growth trajectories. Here we describe the game in detail and the ecological merits for using the game as an educational tool. We also present a free online dynamic simulation for enhanced educational purposes.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section we describe how the Snakes and Ladders concept can be applied to educational activities. Three specified uses are described and include:

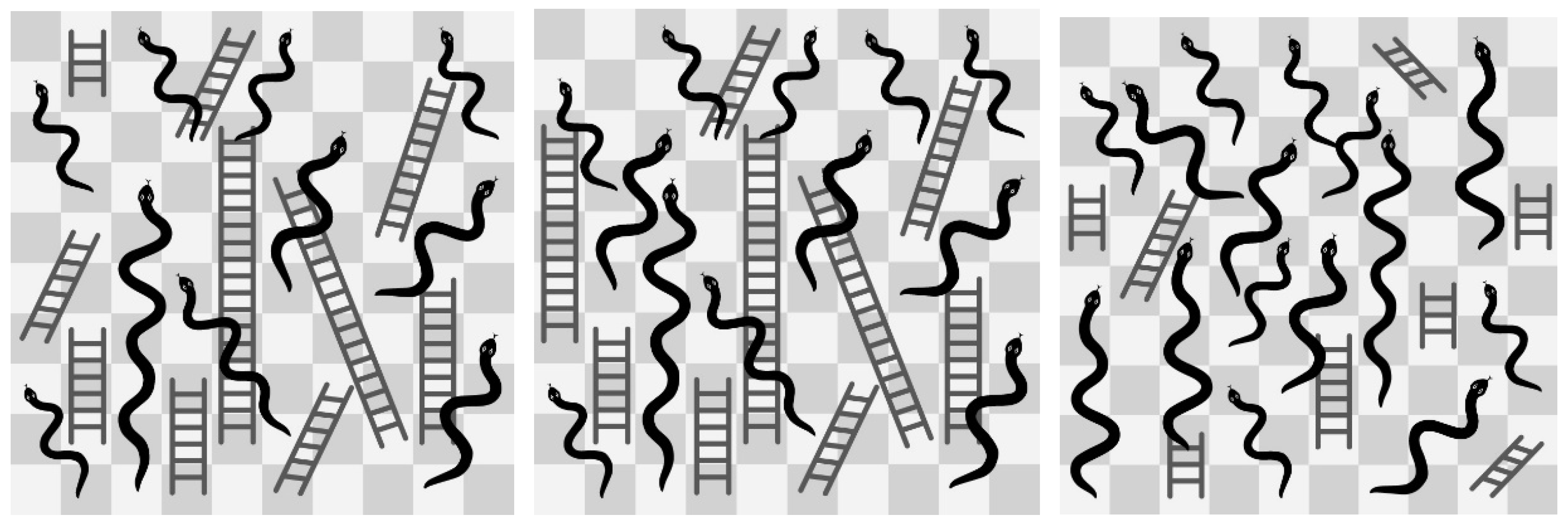

Board play in the traditional game manner but with alternative board configurations depicting projected stages in climate change stressors,

Visual comparison of the board configurations to highlight the environment that coral reefs are managed within,

An online simulation that permits the user to explore the impact of increased number and magnitude of snakes and ladders on the time taken to reach a high quality state.

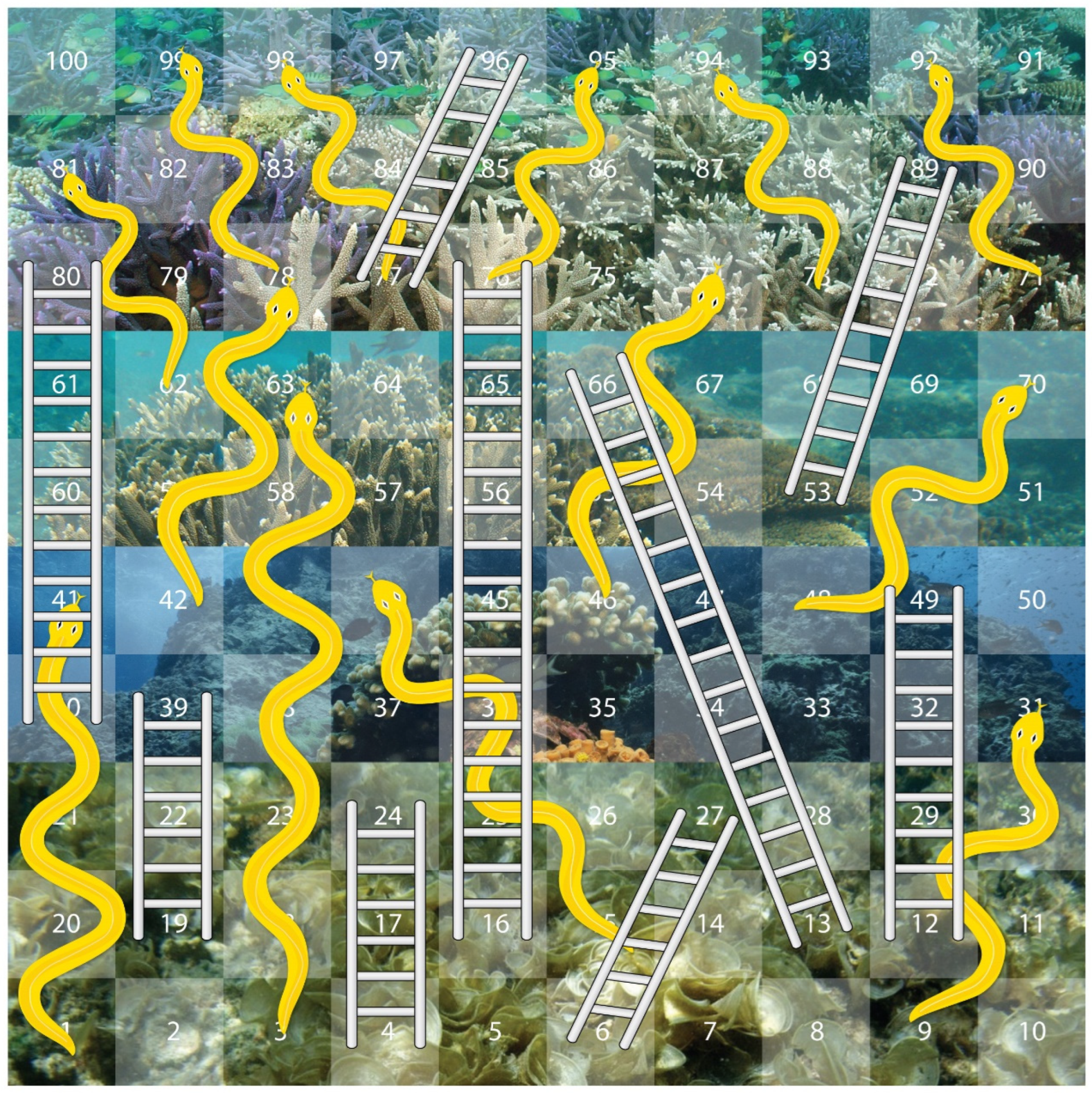

Modified Snakes and Ladders games were constructed with varying levels of stressors reflecting the predicted climate change scenarios for 1900, now and 2100 (Figure 2). To ensure maximum translation to ecology, we limited the changes to the popular version of the game. We used a 10 by 10 checkered board numbered sequentially from 1 to 100 (

Figure 1). The lower numbers (1 to 20) represent an unspecified state of health that is poor (low coral cover or low biodiversity or low resilience) while the higher numbers (80 to 100) represent the healthiest state a reef can achieve. Therefore each player’s chip can represent a coral reef within a common geographic region in order to minimize environmental heterogeneity. Each player starts at the lowest number and using the standard dice values of 1 to 6 precede along the board. With a slight twist on the original game the number of moves required to reach the final square is the measure of success.

However the game is complicated by the addition of ‘snakes’ and ‘ladders’ that either accelerate or retard a ‘coral reef’ chip’s progress. Without these complications each ‘coral reef’ chip would take between 17 (17 x 6 dice moves = 102 squares crossed) and 100 (100 x 1 dice moves =100 squares crossed) moves and winning would simply be a game of lucky dice rolls. With the inclusion of snakes and ladder elements the layout of the board will determine the minimum number of moves possible. Snakes can represent many different processes (over fishing, disease, Acanthaster sp. outbreaks, cyclones, thermal coral bleaching, shipping disaster etc.) that span from retarding growth (perhaps a small magnitude that is less than a dice throw) or severely reducing coral reef health (large magnitude). Likewise the ladders can be used to represent a combination of management actions and natural conditions including marine reserves, shipping control, anchoring protection, strong recruitment, and favorable growth conditions etc.

Students in a third-year marine ecology course (n ≈ 30) engaged with printed board games and digital simulations. Game play was followed by guided debriefing sessions (30–45 minutes) where students discussed coral reef stressors, climate change trajectories, and potential management interventions. Sample prompts included: ‘What management actions could change the board layout?’, ‘What role does chance play in reef outcomes?’, and ‘How does this relate to real-world reef dynamics?’ While no formal evaluation was conducted in this iteration, student comments and reflections were informally documented as part of their course tutorials.

With the board layout as described above, the number of moves to ‘win’ the game will be determined by both the magnitude and frequency of the snakes and ladder elements and also the interaction between each element. We present the scenario that climate change can be sufficiently represented to the public by a modification of this configuration. To do this we presented three variations of the game with different snake and ladder magnitude and frequency values and noted that effect on the number of moves to complete the game. Students were encouraged to view how each game might progress given the variation in board configurations (

Figure 2) before using a dice roll.

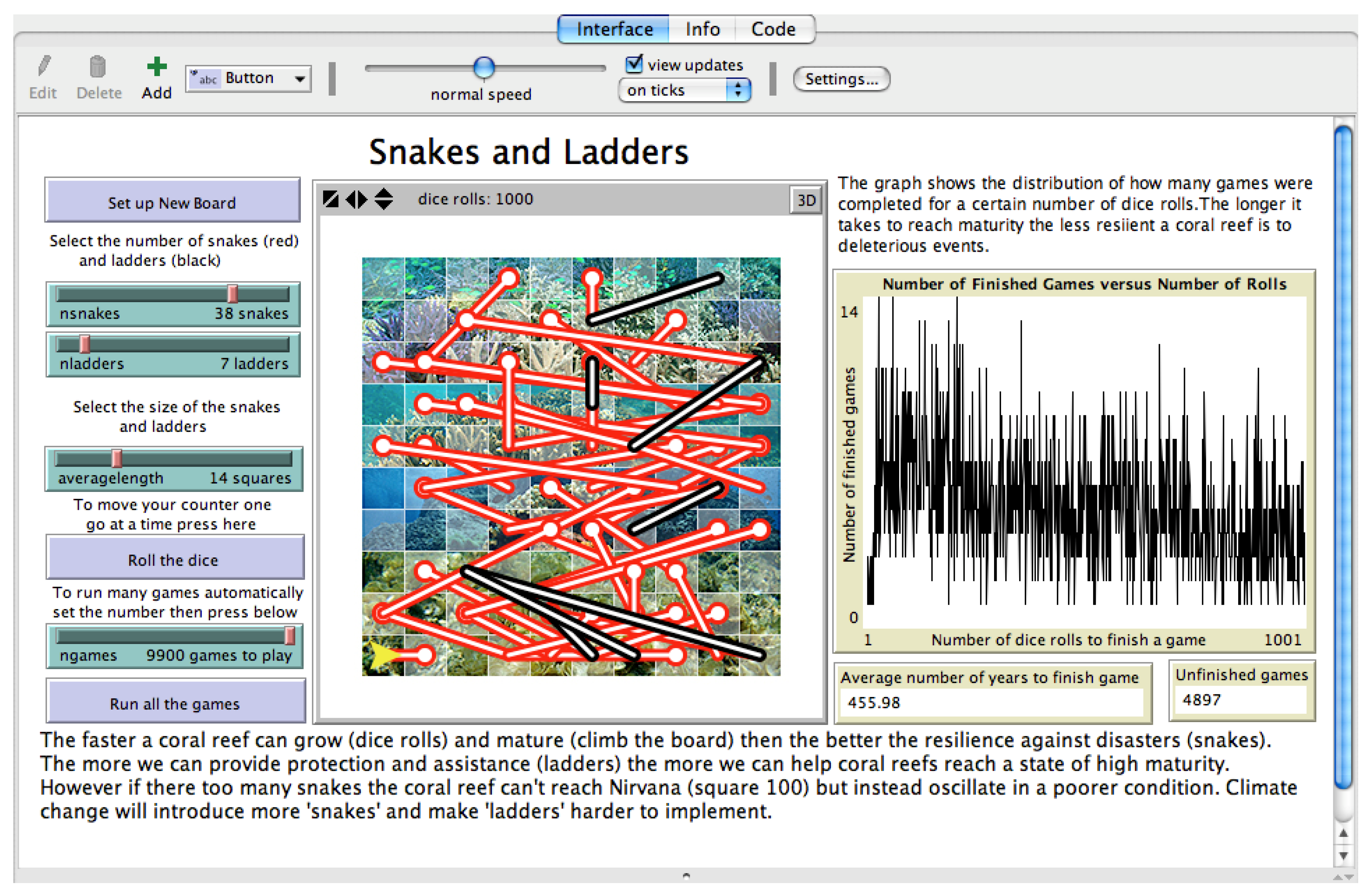

To provide participants the capacity to fully explore how the frequency and magnitude of snakes and ladders can impact on the time it takes to reach a final state we constructed a free deployment of the game. This is generated in the software environment called NetLogo and permits rapid deployment of simulation environments. In particular the simulation can be run through a web browser using a java applet. Users have the capacity to alter the model parameters and run the game thousands of times while viewing the results graphically. For this online game we allocate the magnitude (length) of the snakes and ladders over a Gaussian distribution with a specified mean value. The number of snakes and ladders is user specified while the critical starting point (head of snake and base of ladder) is randomly selected for each new board configuration. Adjustment is made for the snakes and ladder elements to avoid finishing outside of the board domain. Simulations are run 10,000 times for each possible configuration and the duration, in terms of dice rolls, of the game is recorded. Games exceeding 500 moves are considered to be in an endless oscillating system.

3. Results

Despite the simplicity of the game, the educational outcome of playing the Snakes and Ladders game provided robust discussion of the stochastic nature of coral reef growth and the role of management within a changing climate environment. This result was achieved through the simple manipulation of the number and magnitude of ‘snakes’ and ‘ladders’ while noting the capacity of coral reefs ‘chips’ to reach a healthy state (final high value squares). Subsequent discussions were then enhanced by the use of the game based terminology such as this comment ‘climate change snakes will be difficult to overcome with just short ladders’.

The three board configurations, depicting developing stages of climate change, were considered to highlight the plight of coral reefs. The first board configuration (

Figure 2) was designed to represent coral reefs that exist in an optimal environment free of anthropogenic stresses. The second configuration shows the possible state of the system today with a small number of anthropogenic stresses that can be managed with appropriate actions (i.e. fishing and marine reserves). The final board configuration is a futuristic example of what will occur with advanced climate change based stresses with limited management responses.

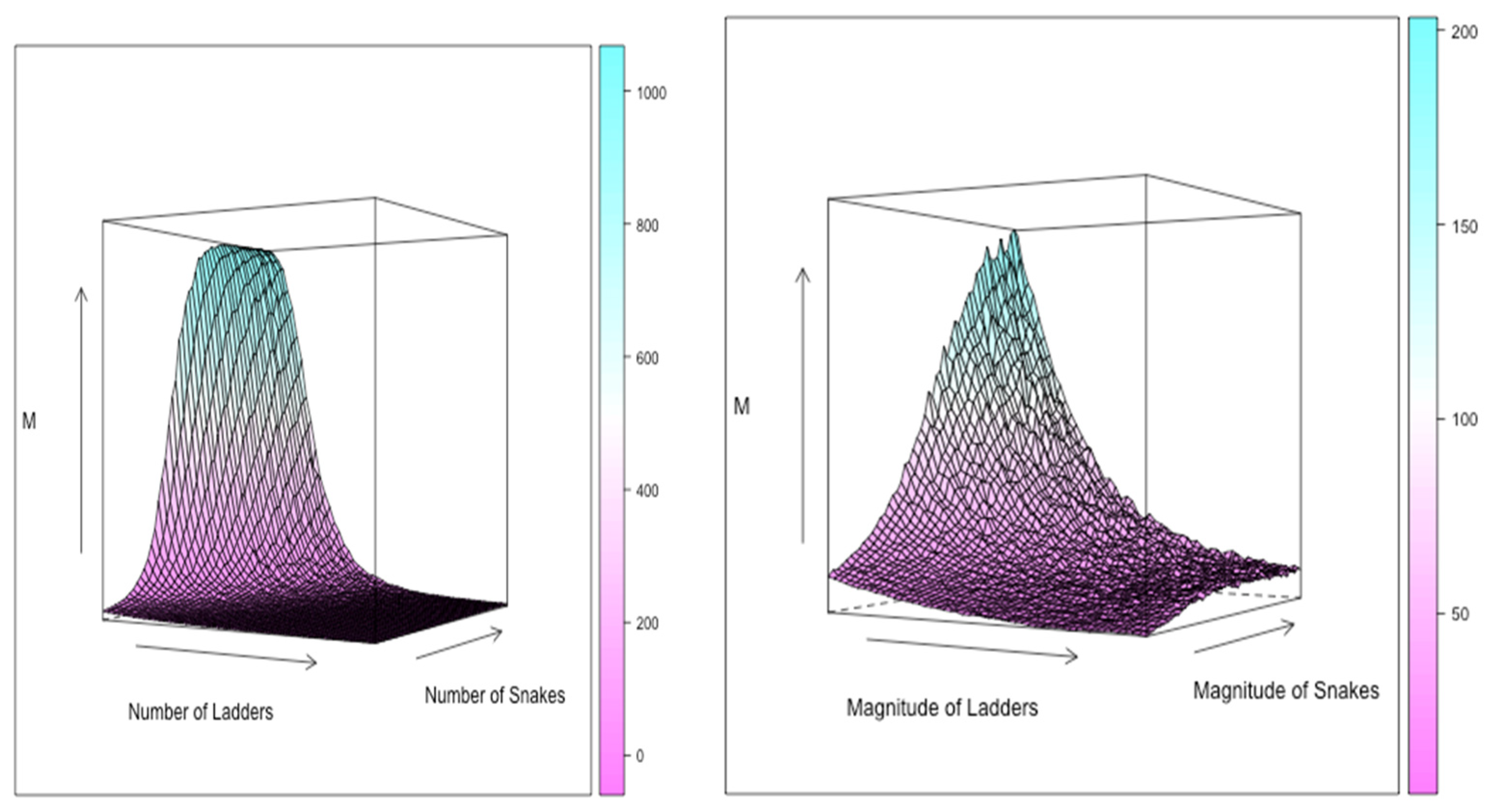

The digital game based on Netlogo 6.4.0 (

http://modelingcommons.org/browse/one_model/3617) permitted users to vary the snakes and ladders within a range from 1 to 50 in frequency and 1 to 50 in magnitude (

Figure 3). Low frequency values of snakes meant the game could be completed within a range of moves from 17 to approximately 300 while higher numbers of snakes can eventually result in the player oscillating in the middle of the board indefinitely. Participants noted that adding more snakes lowered the state of the ‘system’ or conversely rose the state by the addition of more ladders. This is despite some games resulting in rapid completions while other games taking an order of magnitude longer. The code for the game is publically accessible and available as a foundation of further development.

To examine the response of the game to the full parameter suite we used a simulation in the R software environment (

http://cran.r-project.org/). The

Figure 4 shows that as the number of ladders increases the number of moves to reach the finish decreases exponentially. Similarly as the number of snakes increases the number of moves also increases exponentially. A rapid increase in the number of moves when the number of ladders is low and the number of snakes increases is clearly observed. A similar result is observed for increases in the magnitude of the snakes and ladders. Eventually given a high number of snakes, the number of moves required to reach the final destination are infinite (restricted here to 500 moves) and the chip representing the coral reef oscillates around a particular sub-optimal value.

4. Discussion

Translating the Snakes and Ladders game to a model of the coral reef ecosystem highlights the interaction between the number and magnitude of stochastic environmental events and coral reef development in an intuitive format suitable for education. The game enables students to explore some of the key dimensions of resilience such as recruitment and recovery within a familiar setting. Such an approach can serve to bridge the gap between ecological and sociological definitions of resilience and highlight the merit of embracing both perspectives to set and implement conservation objectives [

36]. Importantly the Intended learning objectives can embrace complex ecological theory in a fun and engaging manner (Briggs and Tang 2011).

ILOs are often restricted in their capacity to shift from shallow to deep learning outcomes by the perceived complexity of the topic. In particular, marine science often operates underwater in challenging field environments that make reflective discussion in situ very problematic. Subsequent discussion and reflective sessions often lack the language to enable students to freely express their thoughts. Only when a diverse suite of labels and processes are comfortably assimilated into the students vocabulary that discussions about complex behaviour are productive [

37]. Here the games are rapidly played and the students can refer to elements of the game without hesitation. The immediate affect is to lift the discussion to a level of deep learning about coral reef ecology while slowly introducing scientific terms that have context. The ILOs can therefore be ambitious (Briggs and Tang 2011) and seek long term understanding of coral reef ecology.

As basic as this model is, the game of Snakes and Ladders demonstrates capacity to stimulate and educate about the complexity of the coral reef environment. Importantly management actions are viewed within the context of a dynamic environment [

27]. The language used to describe the resilience framework can now be based on a mix of ‘game duration’ and ‘chance’ rather than words like ‘phase shifts’ and ‘stochastic events’. Enhanced debriefing sessions that are not subdued by terminology can be a direct outcome [

38]. This capacity to appeal to a wider audience including school children is a strong motivator to adopt this game in educational activities [

28].

We acknowledge that several key processes are not encompassed by this model. In particular there is no formal interaction component between the coral reef ‘chips’, and spatial influences such as connectivity between neighbouring reefs [

39]. Also the game is played with no capacity to change the stresses or beneficial actions once the game is underway. Another omission in the model is the lack of variation in the capacity of the coral reef ‘chip’ to respond to stresses [

40] Every ‘chip’ is considered equal which is not evident in the natural systems [

41]. Additional complexity could be added to the game rules but this may detract from the educational appeal and communication value [

28].

The online simulation enables rapid visualization of the effects of adding or subtracting snakes and ladders. Players understand that if they suffer a deleterious event, such as landing on a snake, then they will be at a lower health level until they recover from the previous event. When more snakes are present they expect that more game time will be spent oscillating up and down the board until their lucky dice roll enables the snakes to be passed. Ladders obviously can assist with recovery but only as the board configuration permits. An emergent property of the game play is that a high number of ‘snakes’ makes a transition to a stable climatic state improbable. The translation to coral reef ecology is assisted by the photographic depictions of coral reefs across the board at various stages of development.

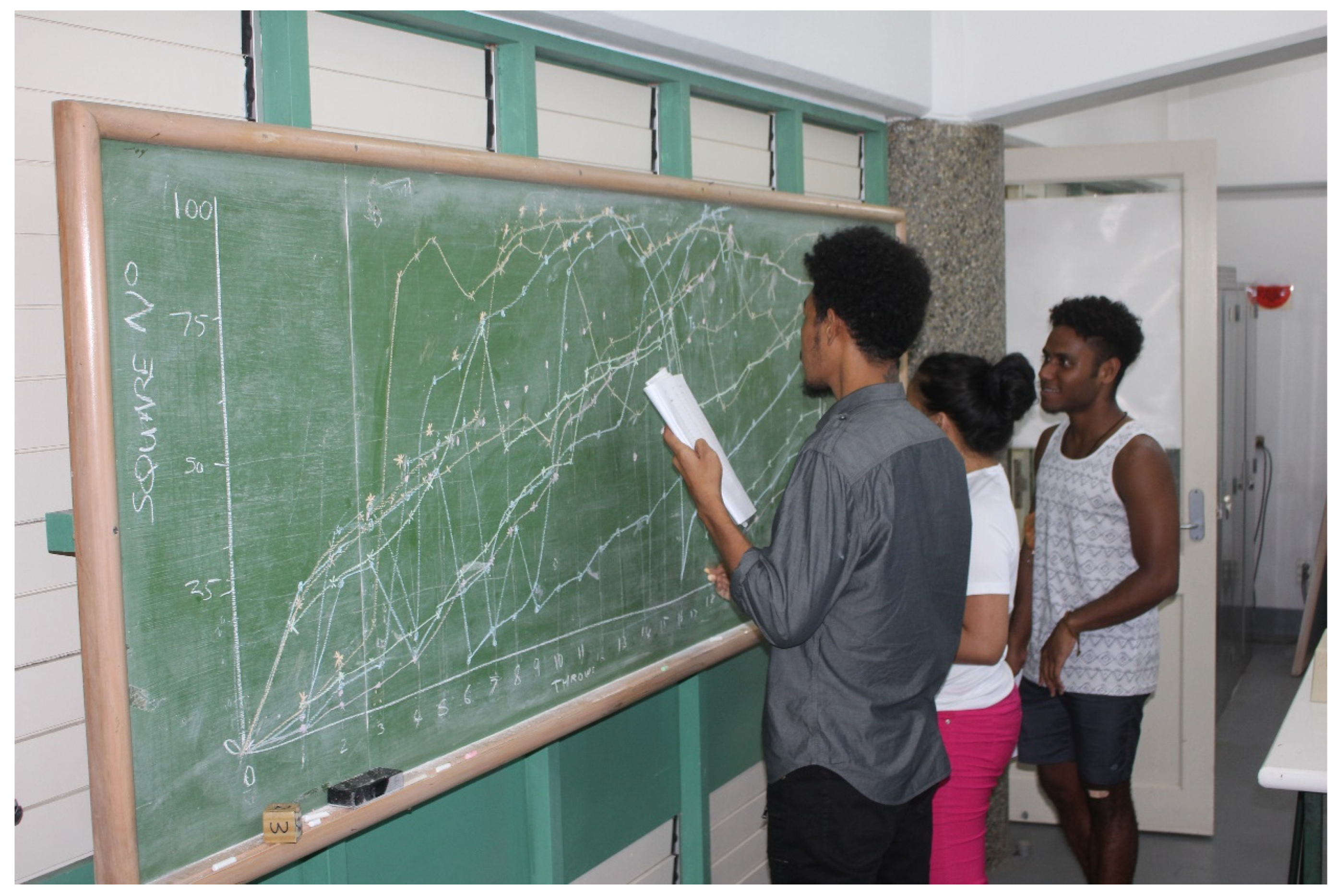

Figure 5.

Students mapping the dynamics of the moves across a class set whereby the x-axis is the number of dive rolls and the y-axis is the number of the square on the board.

Figure 5.

Students mapping the dynamics of the moves across a class set whereby the x-axis is the number of dive rolls and the y-axis is the number of the square on the board.

Players of the game will also strongly identify that the coral reefs do not remain at a steady state (Graham et al., 2011) since while the game is being played, there is a danger that their coral reef ‘chip’ will suffer a deleterious event. This fundamental ecological principal that the coral reefs are forever growing within an environment of positive and negative influences [

15,

16,

42] is useful especially to understanding management strategies such as reserve design [

43,

44]. Management actions often take many years to demonstrate the effectiveness and this is often due to the dynamic state of the system [

4,

45,

46].

Extrapolating the concept to climate change is possible given the current predictions concerning thermal stress, cyclone activity and acidification [

6,

7,

8,

47]. Climate change is predicted to increase the magnitude and frequency of deleterious events, and in many cases local management actions may not exist that can ameliorate the impact of these events on coral reef health. The wider educational community can use this game to visualize how the overall state of the system is depressed as a function of the increased frequency and / or severity of stressors. Key elements in understanding how humans are influencing the board configuration will assist the discussions regarding the appropriate and potentially drastic actions (i.e. transplanting corals and establishing artificial reefs) required to mitigate climate risk (Condie et al. 2021, Bozec et al. 2025 for example).

The key message (that is conveyed just by looking at the multiple climate change scenario boards) is that combinations of chance and board configuration determine the likelihood of a specified coral reef succeeding to reach a state of optimal health. Confusion exists in the popular media about the general state of the coral reefs given specific examples that conflict the broad scale trend [

48,

49]. Reefs that have escaped cyclones, coral bleaching and where they occur COTS outbreaks, may temporally show a high health state while other players may be trapped in the ‘poor’ health state regions of the board [

49]. Chance rather than skill will determine the capacity of each coral reef to succeed to an optimal health state.

By promoting the concept that climate change will potentially result in more and larger ‘snake’ elements the player is able to observe the stochastic changes to the game duration in the digital game. In particular the combined effect of increased deleterious events with reduced management options can be visualized. Importantly the game promotes the perspective that management actions are delivered within the context of the available opportunities for growth. In situations where the abundance of ‘snakes’ reduces the capacity of any ‘chip’ to occupy a healthy state (say top 20 squares) then the ‘ladders’ will be critical to enhance the health status of the simulated ecosystem.

5. Conclusions

The use of gamification (Landers 2015) as a mechanism to provide complex models in easily understood formats [

50,

51] is illustrated here. Coral reef dynamics are complex and management responses are often difficult to fully interpret by students and the broader public. Understanding, at least in part, the capacity of coral reefs to grow under adversity is an important step in appreciating the difficulty managers have with climate change. Games that are simple, yet often result in complex behaviour, are useful to illustrate key concepts in the educational environment. The introduction of the simple terminology embedded in these games, that depict highly variable ecosystem dynamics, greatly enhances the potential of intended learning outcomes covering complex ecological topics particularly as they are altered by a rapidly changing climate.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, The code to run the Netlogo 6.4.0. Graphics for printing and operating the game for educational purposes are available on request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and R.B.; methodology, S.K.; software, S.K.; validation, S.K..; formal analysis, S.K..; investigation, S.K..; writing—original draft preparation, S.K..; writing—review and editing, S.K. and R.B..; visualization, S.K..; supervision, S.K..; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of The University of the South Pacific.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the students to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank the students of the University of the South Pacific especially the MS306 Coral Reef Ecology participants. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hughes, T.P.; Baird, A.H.; Bellwood, D.R.; Card, M.; Connolly, S.R.; Folke, C.; Grosberg, R.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jackson, J.B.C.; Kleypas, J.; et al. Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs. Science 2003, 301, 929–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbi, S.R. MARINE RESERVES AND OCEAN NEIGHBORHOODS: The Spatial Scale of Marine Populations and Their Management. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2004, 29, 31–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, G.; Stuart-Smith, R.; Willis, T.; Kininmonth, S.J.; Baker, S.C.; Banks, S.; Barrett, N.S.; Becerro, M. a.; Edgar, S.C.; Forsterra, G.; et al. Global conservation outcomes depend on marine protected areas with five key features. Nature 2014, 506, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, M.; Choukroun, S.; Emslie, M.J.; Harrison, H.B.; Leis, J.M.; Mason, L.B.; Srinivasan, M.; Williamson, D.H.; Jones, G.P. Marine reserves contribute half of the larval supply to a coral reef fishery. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadt0216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkelmans, R.; De’ath, G.; Kininmonth, S.; Skirving, W.J. A comparison of the 1998 and 2002 coral bleaching events on the Great Barrier Reef: spatial correlation, patterns, and predictions. Coral Reefs 2004, 23, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De’ath, G.; Fabricius, K.E.; Sweatman, H.; Puotinen, M. The 27-year decline of coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef and its causes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Climate change and coral reefs: Trojan horse or false prophecy? Coral Reefs 2009, 28, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Barnes, M.L.; Bellwood, D.R.; Cinner, J.E.; Cumming, G.S.; Jackson, J.B.C.; Kleypas, J.; van de Leemput, I.A.; Lough, J.M.; Morrison, T.H.; et al. Coral reefs in the Anthropocene. Nature 2017, 546, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Woesik, R.; Done, T.J. Coral communities and reef growth in the southern Great Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs 1997, 16, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Climate Change Adaption - Outcomes from the GBR Climate Change Action Plan 2007-2012; GBRMPA, Townsville, 2012; ISBN 9781921682865.

- Australian Government; Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Reef Outlook Report 2024; 2024; ISBN 9780645043877.

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Reef Blueprint 2030. 2024.

- Mellin, C.; Aaron Macneil, M.; Cheal, A.J.; Emslie, M.J.; Julian Caley, M. Marine protected areas increase resilience among coral reef communities. Ecol. Lett. 2016, 19, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, S.A.; Williamson, D.H.; Beeden, R.; Emslie, M.J.; Abom, R.T.M.; Beard, D.; Bonin, M.; Bray, P.; Campili, A.R.; Ceccarelli, D.M.; et al. Protecting Great Barrier Reef resilience through effective management of crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks. PLoS One 2024, 19, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condie, S.A.; Anthony, K.R.N.; Babcock, R.C.; Baird, M.E.; Beeden, R.; Fletcher, C.S.; Gorton, R.; Harrison, D.; Hobday, A.J.; Plagányi, É.E.; et al. Large-scale interventions may delay decline of the Great Barrier Reef. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, J.H.; Hughes, T.P.; Wallace, C.C.; Tanner, J.E.; Harms, K.E.; Kerr, A.M. A long-term study of competition and diversity of corals. Ecol. Monogr. 2004, 74, 179–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcleod, E.; Anthony, K.R.N.; Mumby, P.J.; Maynard, J.; Beeden, R.; Graham, N.A.J.; Heron, S.F.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jupiter, S.; MacGowan, P.; et al. The future of resilience-based management in coral reef ecosystems. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 233, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmhirst, T.; Connolly, S.R.; Hughes, T.P. Connectivity, regime shifts and the resilience of coral reefs. Coral Reefs 2009, 28, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.P.; Russ, G.R.; Sale, P.F.; Steneck, R.S. Theme section on “Larval connectivity, resilience and the future of coral reefs. ” Coral Reefs 2008, 28, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entremont, J.G.D. Building Trust, Empowering Resource Users: Efforts Underway to Educate, Encourage Participation of Fishermen in MPA Processes. MPA News 2003, 4, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P.; Drake, S.F. The international coral reef initiative: A strategy for the sustainable management of coral reefs and related ecosystems. 2008, 37–41.

- Fischhoff, B. Applying the science of communication to the communication of science. Clim. Change 2011, 108, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, N.E.; Zavaleta, E.S. Biodiversity management in the face of climate change: A review of 22 years of recommendations. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, D. A playful shift: Field-based experimental games offer insight into capacity reduction in small-scale fisheries. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 144, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Bellwood, D.R.; Folke, C.; Steneck, R.S.; Wilson, J. New paradigms for supporting the resilience of marine ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 380–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condie, S.A.; Anthony, K.R.N.; Babcock, R.C.; Baird, M.E.; Beeden, R.; Fletcher, C.S.; Gorton, R.; Harrison, D.; Hobday, A.J.; Plagányi, É.E.; et al. Large-scale interventions may delay decline of the Great Barrier Reef. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meadows, D. Climate Change and Four Goals for Operational Gaming. Simul. Gaming 2013, March, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckien, D.; Eisenack, K. Climate Change Gaming on Board and Screen: A Review. Simul. Gaming 2013, March, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, J.; Anthony, K.R.N.; Afatta, S.; Dahl-Tacconi, N.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Making a model meaningful to coral reef managers in a developing nation: a case study of overfishing and rock anchoring in Indonesia. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 1316–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnosky, A.D.; Hadly, E. a; Bascompte, J.; Berlow, E.L.; Brown, J.H.; Fortelius, M.; Getz, W.M.; Harte, J.; Hastings, A.; Marquet, P. a; et al. Approaching a state shift in Earth’s biosphere. Nature 2012, 486, 52–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeford, M.; Done, T.J.; Johnson, C.R. Decadal trends in a coral community and evidence of changed disturbance regime. Coral Reefs 2007, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Ceyhan, P.; Jordan-Cooley, W.; Sung, W. GREENIFY: A Real-World Action Game for Climate Change Education. Simul. Gaming 2013, 44, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, D.; Dray, A.; Perez, P.; Cruz-Trinidad, A.; Geronimo, R.; Kokotajlo, D.; Cleland, D. Simulating the Dynamics of Subsistence Fishing Communities: REEFGAME as a Learning and Data-Gathering Computer-Assisted Role-Play Game. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2012, 43, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenack, K. A Climate Change Board Game for Interdisciplinary Communication and Education. Simul. Gaming 2013, June, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althoen, S.; King, L.; Schilling, K. How long is a game of snakes and ladders? Math. Gaz. 1993, 77, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, F.S.; Jax, K. Focusing the Meaning ( s ) of Resilience: Resilience as a Descriptive Concept and a Boundary Object. Environ. Soc. 2007, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, B.; Proust, K. Introduction to Collaborative Conceptual Modelling. ANU Open Access Res. Work. Pap. 2012, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, B. Simple models, powerful ideas: Towards effective integrative practice. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2012, 22, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kininmonth, S.; De’ath, G.; Possingham, H. Graph theoretic topology of the Great but small Barrier Reef world. Theor. Ecol. 2010, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, N. a. J.; Nash, K.L.; Kool, J.T. Coral reef recovery dynamics in a changing world. Coral Reefs 2011, 30, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Game, E.T.; McDonald-Madden, E.; Puotinen, M.L.; Possingham, H.P. Should we protect the strong or the weak? Risk, resilience, and the selection of marine protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 1619–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozec, Y.; Adam, A.A.S.; Nava, B.A.; Cresswell, A.K. A rapidly closing window for coral persistence under global warming. 2025.

- Kininmonth, S.J.; Beger, M.; Bode, M.; Peterson, E.; Adams, V.M.; Dorfman, D.; Brumbaugh, D.R.; Possingham, H.P. Dispersal connectivity and reserve selection for marine conservation. Ecol. Modell. 2011, 222, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, M.E.; Ball, I.R.; Stewart, R.S.; Klein, C.J.; Wilson, K.; Steinback, C.; Lourival, R.; Kircher, L.; Possingham, H.P. Marxan with Zones: Software for optimal conservation based land- and sea-use zoning. Environ. Model. Softw. 2009, 24, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almany, G.R.; Connolly, S.R.; Heath, D.D.; Hogan, J.D.; Jones, G.P.; McCook, L.J.; Mills, M.; Pressey, R.L.; Williamson, D.H. Connectivity, biodiversity conservation and the design of marine reserve networks for coral reefs. Coral Reefs 2009, 28, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steneck, R.S.; Paris, C.B.; Arnold, S.N.; Ablan-Lagman, M.C.; Alcala, a. C.; Butler, M.J.; McCook, L.J.; Russ, G.R.; Sale, P.F. Thinking and managing outside the box: coalescing connectivity networks to build region-wide resilience in coral reef ecosystems. Coral Reefs 2009, 28, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De’ath, G.; Lough, J.M.; Fabricius, K.E. Declining coral calcification on the Great Barrier Reef. Science 2009, 323, 116–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veron, J.E.N. Mass extinctions and ocean acidification: biological constraints on geological dilemmas. Coral Reefs 2008, 27, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emslie, M.J.; Logan, M.; Bray, P.; Ceccarelli, D.M.; Cheal, A.J.; Hughes, T.P.; Johns, K.A.; Jonker, M.J.; Kennedy, E. V.; Kerry, J.T.; et al. Increasing disturbance frequency undermines coral reef recovery. Ecol. Monogr. 2024, 94, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszlo, A.; Rowland, R.; Taylor, G. World Futures: The Journal of Global Education Virtual Learning in a Socially Digitized World. World Futures 2012, 68, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Sicart, M.; Nacke, L.; O’Hara, K.; Dixon, D. Gamification. using game-design elements in non-gaming contexts. In Proceedings of the CHI 2011, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011; pp. 2–5. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).