Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

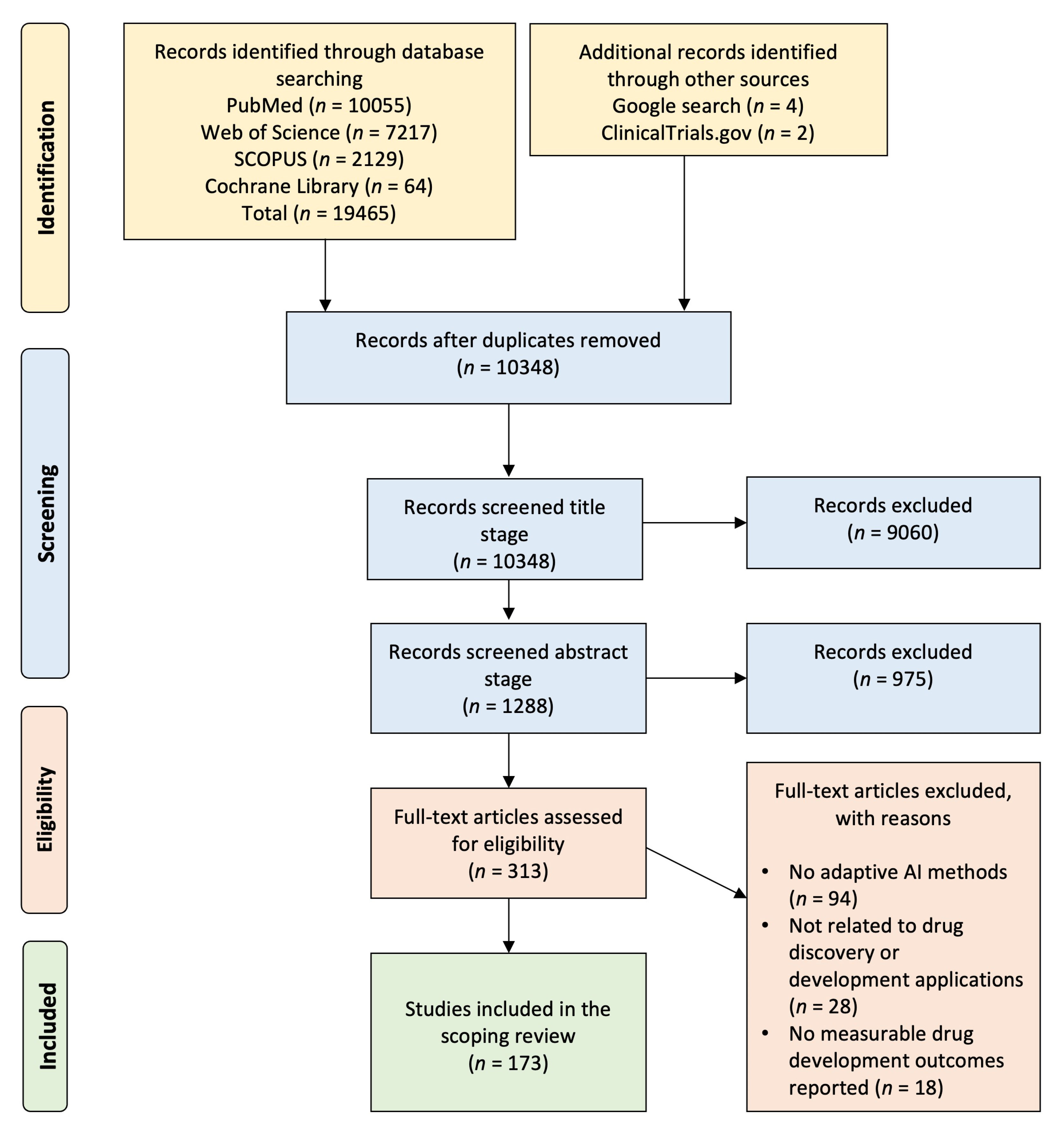

2.1. Systematic Literature Search and Study Selection Workflow

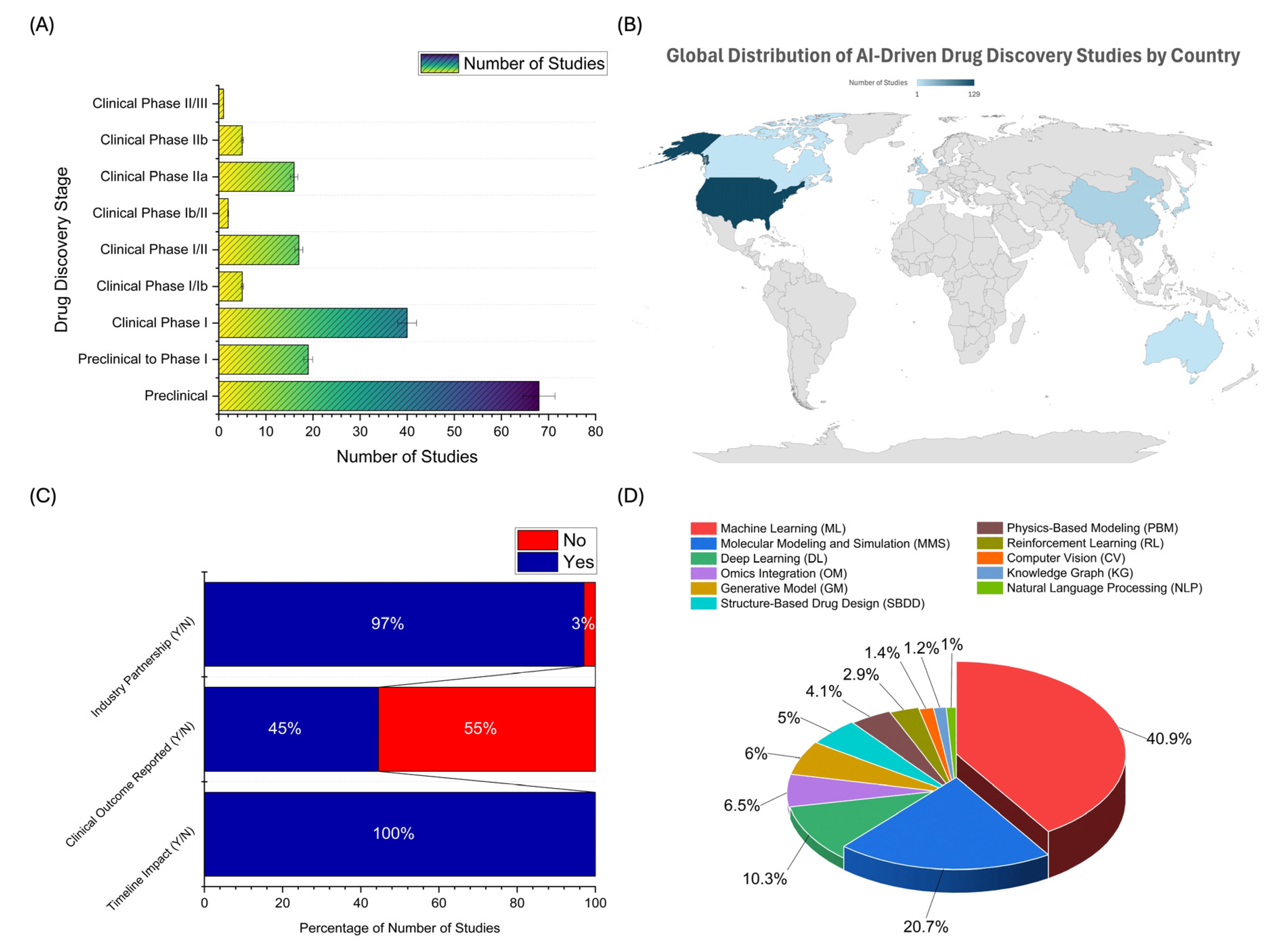

2.2. Distribution of AI Applications Across Drug Development Stages, Geographic Trends, Industry Collaboration, and AI Technology Adoption

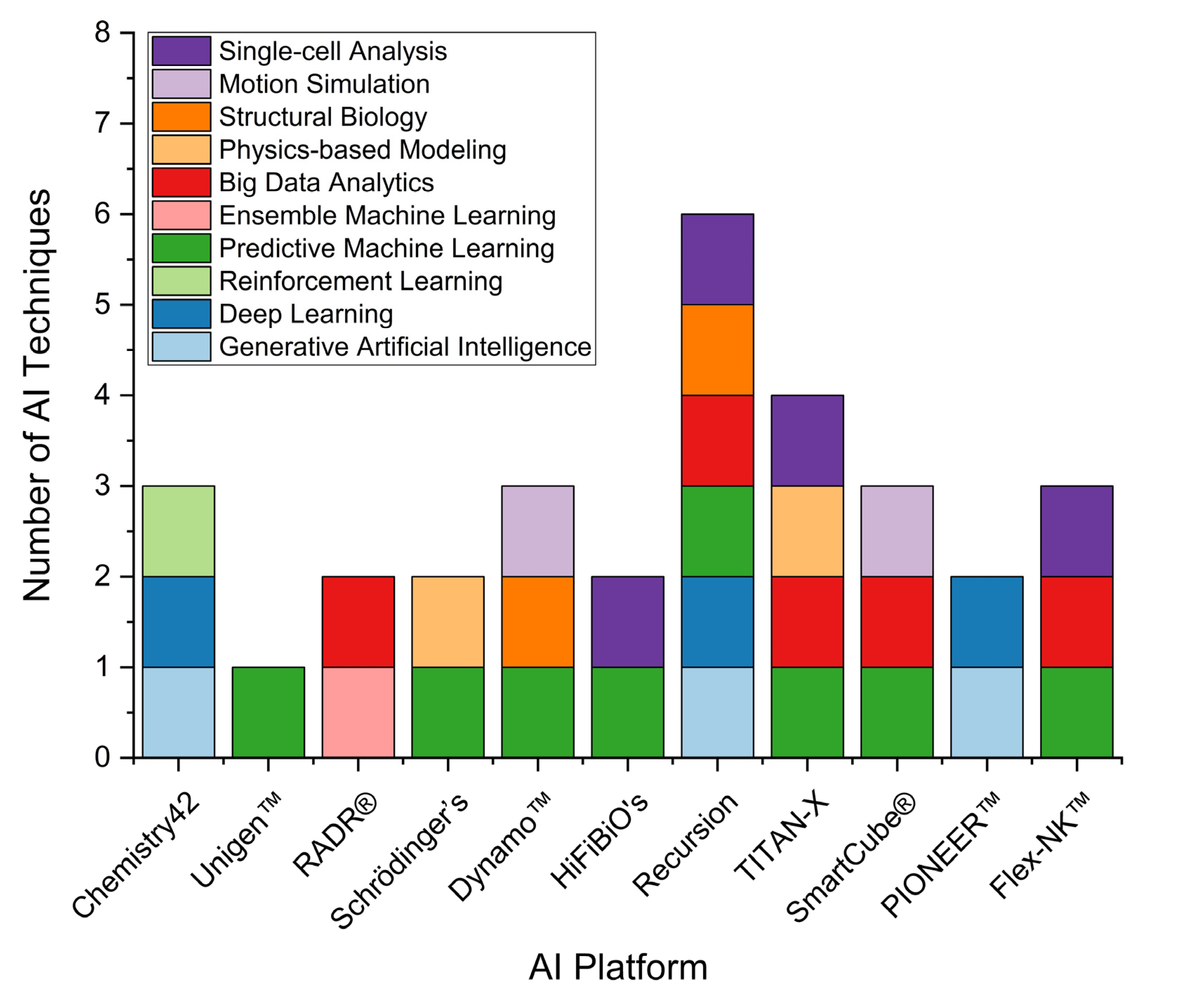

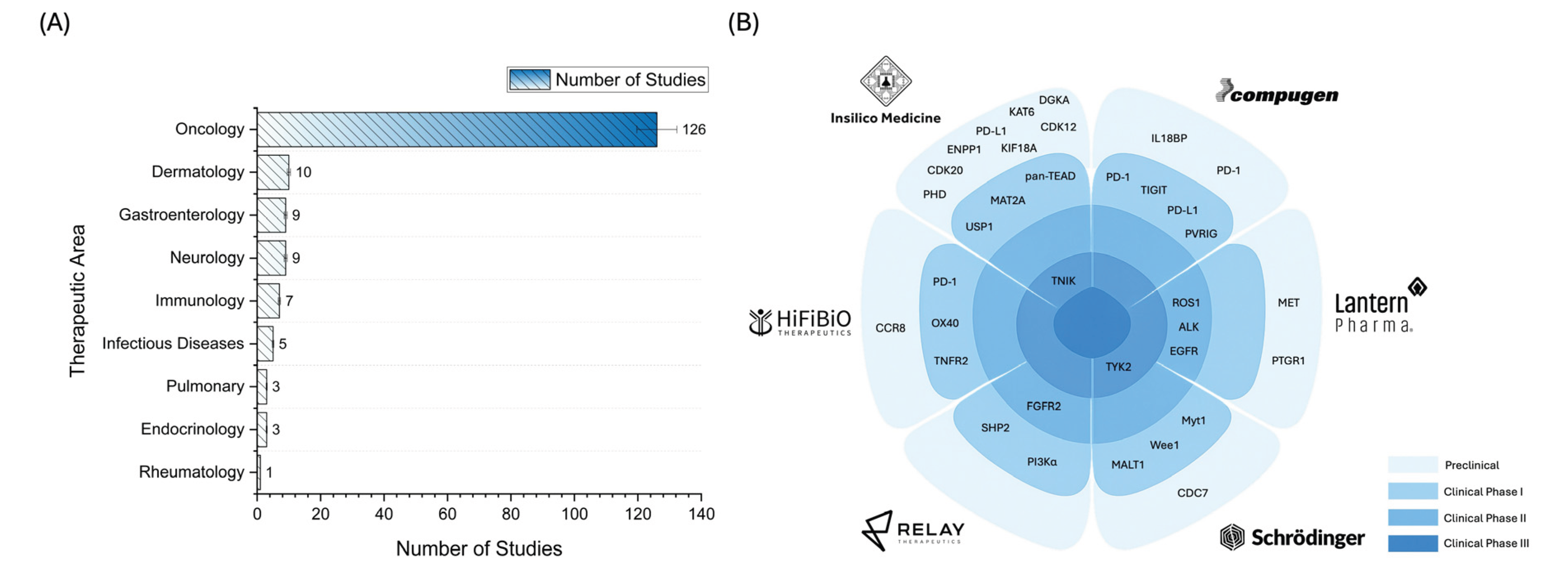

2.3. Landscape of AI Applications in Pharmaceutical R&D: Trends and Case Studies

3. Discussion

3.1. Main Findings and Comparison with Prior Works

3.2. Limitations and Future Works

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Eligibility Criteria

4.2. Information Sources

4.3. Search Strategy

4.4. Study Selection

4.5. Data Extraction

4.6. Data Synthesis and Interpretations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADMET | Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| CV | Computer vision |

| DDD | Drug discovery and development |

| DL | Deep learning |

| GM | Generative model |

| HGSOC | High-grade serous ovarian cancer |

| HTS | High-throughput screening |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| IND | Investigational new drug |

| IPF | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| KG | Knowledge graph |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MMS | Molecular modeling and simulation |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| OCD | Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

| OM | Omics integration |

| PBM | Physics-based modeling |

| PK/PD | Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics |

| PRISMA | Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses |

| QSAR | Quantitative structure–activity relationship |

| R&D | Research and development |

| RL | Reinforcement learning |

| SBDD | Structure-based drug design |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

References

- Paul, S.M. , et al., How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry's grand challenge. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2010. 9(3): p. 203-214.

- DiMasi, J.A. H.G. Grabowski, and R.W. Hansen, Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. J Health Econ, 2016. 47: p. 20-33.

- Berdigaliyev, N. and M. Aljofan, An overview of drug discovery and development. Future Med Chem, 2020. 12(10): p. 939-947.

- Hay, M. , et al., Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nat Biotechnol, 2014. 32(1): p. 40-51.

- Wong, C.H. K.W. Siah, and A.W. Lo, Estimation of clinical trial success rates and related parameters. Biostatistics, 2019. 20(2): p. 273-286.

- Scannell, J.W. , et al., Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2012. 11(3): p. 191-200.

- Mak, K.K. and M.R. Pichika, Artificial intelligence in drug development: present status and future prospects. Drug Discov Today, 2019. 24(3): p. 773-780.

- Ekins, S. , et al., Exploiting machine learning for end-to-end drug discovery and development. Nat Mater, 2019. 18(5): p. 435-441.

- Wu, Y. and L. Xie, AI-driven multi-omics integration for multi-scale predictive modeling of genotype-environment-phenotype relationships. Comput Struct Biotechnol J, 2025. 27: p. 265-277.

- Vamathevan, J. , et al., Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2019. 18(6): p. 463-477.

- Zhavoronkov, A. From Start to Phase 1 in 30 Months: AI-discovered and AI-designed Anti-fibrotic Drug Enters Phase I Clinical Trial. 2022 [cited 2025 10 March]; Available from: https://insilico.com/phase1.

- Burki, T. , A new paradigm for drug development. Lancet Digit Health, 2020. 2(5): p. e226-e227.

- Serrano, D.R. , et al., Artificial Intelligence (AI) Applications in Drug Discovery and Drug Delivery: Revolutionizing Personalized Medicine. Pharmaceutics, 2024. 16(10).

- Andy, A. and C. James, Hybrid Physics-AI Approaches for Protein-Ligand Docking and Scoring. 2025.

- Niazi, S.K. and Z. Mariam, Computer-Aided Drug Design and Drug Discovery: A Prospective Analysis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2023. 17(1).

- Ren, F. , et al., A small-molecule TNIK inhibitor targets fibrosis in preclinical and clinical models. Nat Biotechnol, 2025. 43(1): p. 63-75.

- Waldron, J. Sanofi signs $1.2B pact with Atomwise in latest high-value AI drug discovery deal. 2022 [cited 2025 15th April]; Available from: https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/sanofi-signs-12b-pact-atomwise-latest-high-value-ai-drug-discovery-deal.

- AstraZeneca. AstraZeneca starts artificial intelligence collaboration to accelerate drug discovery, /: 2025 15th April]; Available from: https, 2025.

- Al-Idrus, A. AI drug prospector Recursion bumps IPO up (again) to $374M. 2021 [cited 2025 15th April]; Available from: https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/ai-drug-prospector-recursion-bumps-ipo-up-again-to-374m.

- Robinson, R. The Uptick in AI Use Will Bring Pharma Into the Future Faster. 2019 [cited 2025 15th April]; Available from: https://www.pharmavoice.com/news/2019-11-ai/612372/.

- Roche. Roche to acquire Flatiron Health to accelerate industry-wide development and delivery of breakthrough medicines for patients with cancer, /: 2025 16th April]; Available from: https, 2025.

- Novartis. Novartis and Microsoft announce collaboration to transform medicine with artificial intelligence, /: 2025 16th April]; Available from: https, 2025.

- Vatansever, S. , et al., Artificial intelligence and machine learning-aided drug discovery in central nervous system diseases: State-of-the-arts and future directions. Med Res Rev, 2021. 41(3): p. 1427-1473.

- Bera, I. and P.V. Payghan, Use of Molecular Dynamics Simulations in Structure-Based Drug Discovery. Curr Pharm Des, 2019. 25(31): p. 3339-3349.

- Alotaiq, N. D. Dermawan, and N.E. Elwali, Leveraging Therapeutic Proteins and Peptides from Lumbricus Earthworms: Targeting SOCS2 E3 Ligase for Cardiovascular Therapy through Molecular Dynamics Simulations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024. 25(19): p. 10818.

- Musliha, A. , et al., Unraveling modulation effects on albumin synthesis and inflammation by Striatin, a bioactive protein fraction isolated from Channa striata: In silico proteomics and in vitro approaches. Heliyon, 2024. 10(19): p. e38386.

- Choudhary, K. , et al., Recent advances and applications of deep learning methods in materials science. npj Computational Materials, 2022. 8(1): p. 59.

- Fu, C. and Q. Chen, The future of pharmaceuticals: Artificial intelligence in drug discovery and development. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis, 2025: p. 101248.

- Tong, X. , et al., Generative Models for De Novo Drug Design. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2021. 64.

- Gangwal, A. and A. Lavecchia, Unleashing the power of generative AI in drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today, 2024. 29(6): p. 103992.

- Ataeinia, B. and P. Heidari, Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Radiopharmaceutical Development:: In Silico Smart Molecular Design. PET Clin, 2021. 16(4): p. 513-523.

- Alotaiq, N. and D. Dermawan Computational Investigation of Montelukast and Its Structural Derivatives for Binding Affinity to Dopaminergic and Serotonergic Receptors: Insights from a Comprehensive Molecular Simulation. Pharmaceuticals, 2025. 18,. [CrossRef]

- Popova, M. O. Isayev, and A. Tropsha, Deep reinforcement learning for de novo drug design. Sci Adv, 2018. 4(7): p. eaap7885.

- Tan, R.K., Y. Liu, and L. Xie, Reinforcement learning for systems pharmacology-oriented and personalized drug design. Expert Opin Drug Discov, 2022. 17(8): p. 849-863.

- Lindroth, H. , et al. Applied Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: A Review of Computer Vision Technology Application in Hospital Settings, 2024; 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , et al., A comprehensive large scale biomedical knowledge graph for AI powered data driven biomedical research. bioRxiv, 2025.

- Perdomo-Quinteiro, P. and A. Belmonte-Hernández, Knowledge Graphs for drug repurposing: a review of databases and methods. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 2024. 25(6): p. bbae461.

- Jang, H. and B. Yoon, An explainable artificial intelligence – human collaborative model for. investigating patent novelty. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Just, J. , Natural language processing for innovation search – Reviewing an emerging non-human innovation intermediary. Technovation, 2024. 129: p. 102883.

- Ivanenkov, Y.A. , et al., Chemistry42: An AI-Driven Platform for Molecular Design and Optimization. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 2023. 63(3): p. 695-701.

- Kathad, U. , et al., Development and clinical validation of Lantern Pharma’s AI engine: Response algorithm for drug positioning and rescue (RADR). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 37(15_suppl): p. 3114-3114.

- Alexandrov, V. , et al., High-throughput analysis of behavior for drug discovery. European Journal of Pharmacology, 2015. 750: p. 82-89.

- Long, G.V. , et al., KEYNOTE – D36: Personalized Immunotherapy with a Neoepitope Vaccine, EVX-01 and Pembrolizumab in Advanced Melanoma. Future Oncology, 2022. 18(31): p. 3473-3480.

- Dumbrava, E.E. , et al., A first-in-human, phase 1 study evaluating oral TACC3 inhibitor, AO-252, in advanced solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2024. 42(16_suppl): p. TPS3176-TPS3176.

- Patel, M.R. , et al., Preliminary results from a phase 1 study of AC699, an orally bioavailable chimeric estrogen receptor degrader, in patients with advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2024. 42(16_suppl): p. 3074-3074.

- Niewiarowska, A. , et al., Phase 2 clinical investigation of BPM31510 (ubidecarenone) alone and in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Annals of Oncology, 2017. 28: p. v157.

- Xia, S. , et al., BSI-001, a novel anti-HER2 antibody exhibiting potent synergistic efficacy with trastuzumab. Cancer Research, 2022. 82(12_Supplement): p. 5290-5290.

- Molnar, J. , et al., DOP098 Development of BEN8744, a phase 2 ready, peripherally restricted PDE10 inhibitor targeting a new mechanism of action for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, 2025. 19(Supplement_1): p. i263-i263.

- Hartman, G. , et al., The discovery of novel and potent indazole NLRP3 inhibitors enabled by DNA-encoded library screening. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2024. 102: p. 129675.

- Risinger, R., L. Rajachandran, and H. Robinson, A Phase Ib/II Study of BXCL501 in Agitation Associated with Dementia. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 2025. 20.

- Rotta, M. , et al., Covalent-103: A phase 1, open-label, dose-escalation and expansion study of BMF-500, an oral covalent FLT3 inhibitor, in adults with acute leukemia (AL). Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2024. 42(16_suppl): p. TPS6589-TPS6589.

- Patel, J. , et al., EP.12H.01 A Phase 2 Study to Assess BDTX-1535, An Oral EGFR Inhibitor, in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 2024. 19(10, Supplement): p. S657.

- Idowu, O. , et al., 688P Pharmacokinetics of HMBD-001, a human monoclonal antibody targeting HER3, a CRUK first-in-human phase I trial in patients with advanced solid tumours. Annals of Oncology, 2023. 34: p. S480.

- Grant, S. , et al., DOP02 Single cell RNA sequencing of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Disease tissue samples informs the selection of Triggering Receptors Expressed on Myeloid Cells 1 (TREM1) as a target for the treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, 2023. 17(Supplement_1): p. i59-i60.

- Dumbrava, E. , et al., 477 COM902 (Anti-TIGIT antibody) monotherapy – preliminary evaluation of safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and receptor occupancy in patients with advanced solid tumors (NCT04354246). Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, 2021. 9(Suppl 2): p. A507.

- Khairnar, V. , et al., CYT-338 NK Cell Engager Mutispecific Antibody Engagement of NKp46 Activation Receptor Overcomes Anti-CD38 Mab Mediated Fratricide of NK Cells and Accords Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Blood, 2023. 142: p. 6725.

- Segal Salto, M. , et al., DC-9476, a Novel Selective BRD4(BD2) Inhibitor, Improves Arthritis Scores in Preclinical Models of Rheumatoid Arthritis by Regulating Key Inflammatory Pathways. Arthritis Rheumatol., 2024. 76(suppl 9).

- Xu, C. , et al., Alpha-kinase 1 (ALPK1) agonist DF-006 demonstrates potent efficacy in mouse and primary human hepatocyte (PHH) models of hepatitis B. Hepatology, 2023. 77(1): p. 275-289.

- Wong, G. , A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Ascending Dose Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of a Single Dose of EMP-012 for Injection Administered Subcutaneously to Healthy Volunteers, in CENTRAL 2024 Issue 6. 2024.

- Khattak, A. , et al., 782-H Effects of an AI generated personalized neopeptide-based immunotherapy, EVX-01, in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic melanoma: a clinical trial update. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, 2023. 11(Suppl 2): p. A1818.

- Diaz, N. , et al., Data from first-in-human study of EXS21546, an A2A receptor antagonist, now progressing into phase 1 in RCC/NSCLC. Cancer Research, 2023. 83(8_Supplement): p. CT114-CT114.

- Eckstein, F. , et al., Long-term efficacy and safety of intra-articular sprifermin in patients with knee osteoarthritis: results from the 5-year forward study. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 2020. 28: p. S77-S78.

- Keating, A.T. , et al., Phase 1/2 study of FMC-376 an oral KRAS G12C dual inhibitor in participants with locally advanced unresectable or metastatic solid tumors (PROSPER). Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2024. 42(16_suppl): p. TPS3184-TPS3184.

- Wentzel, K. , et al., A phase I/II, open-label study of the novel checkpoint IGSF8 inhibitor GV20-0251 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Annals of Oncology, 2024. 35: p. S680-S681.

- Guzman, B. , et al., GT-02287, a brain-penetrant structurally targeted allosteric regulator for glucocerebrosidase show evidence of pharmacological efficacy in models of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 2023. 113.

- De Alwis, D. , et al., First-in-human study of a novel half-life extended monoclonal antibody (GB-0669) against SARS-CoV2 and related sarbecoviruses. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 2025. 12(Supplement_1): p. ofae631.026.

- Spira, A.I. , et al., Phase I study of HFB200301, a first-in-class TNFR2 agonist monoclonal antibody in patients with solid tumors selected via Drug Intelligent Science (DIS). Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2022. 40(16_suppl): p. TPS2670-TPS2670.

- Sanborn, R.E. , et al., First-in-human (FIH) phase I data of HST-1011, an oral CBL-B inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Annals of Oncology, 2024. 35: p. S675-S676.

- Rodon Ahnert, J. , et al., A phase 1 first-in-human clinical trial of HMBD-002, an IgG4 monoclonal antibody targeting VISTA, in advanced solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2023. 41(16_suppl): p. TPS2664-TPS2664.

- Adjei, A.A. , et al., IAM1363-01: A phase 1/1b study of a selective and brain-penetrant HER2 inhibitor for HER2-driven solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2024. 42(16_suppl): p. TPS3186-TPS3186.

- Ren, F. , et al., A small-molecule TNIK inhibitor targets fibrosis in preclinical and clinical models. Nature Biotechnology, 2025. 43(1): p. 63-75.

- Kim, H. , et al., Development of a novel fusion protein, JUV-161, that enhances muscle regeneration for treatment of myotonic dystrophy type 1. Neuromuscular Disorders, 2024. 43: p. 104441.516.

- Leber, A. , et al., Efficacy and Safety of Omilancor in a Phase 2 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG, 2023. 118(10S).

- McKean, W. , et al., Phase 1 Clinical Trial of LP-284, a Novel Synthetically Lethal Small Molecule, in Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas and Solid Tumors. Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia, 2024. 24: p. S482-S483.

- Huang, Y. , et al., Organ-specific delivery of a mRNA-encoded bispecific T cell engager targeting Glypican-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, 2024. 12(Suppl 2): p. A1499.

- Wang, S. , et al., Halicin: A New Horizon in Antibacterial Therapy against Veterinary Pathogens. Antibiotics (Basel), 2024. 13(6).

- Verstockt, B. , et al., The Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Clinical Efficacy of the NLRX1 agonist NX-13 in Active Ulcerative Colitis: Results of a Phase 1b Study. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, 2024. 18(5): p. 762-772.

- Khanna, D. , et al., BASELINE DEMOGRAPHICS AND DISEASE CHARACTERISTICS IN SUBJECTS WITH ILD IN A PHASE 2 STUDY TO EVALUATE EFFICACY, SAFETY, AND TOLERABILITY OF MT-7117 IN DIFFUSE CUTANEOUS SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2024. 83: p. 1934-1935.

- Hussain, A. , et al., Changes in circulating lymphocyte subsets and CCR9 transcripts as mechanistic biomarkers of the small molecule α4β7 inhibitor MORF-057 in patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, 2025. 19(Supplement_1): p. i1854-i1855.

- Leber, A. , et al., Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of NIM-1324 an Oral LANCL2 Agonist in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase I Clinical Trial. Clin Transl Sci, 2025. 18(1): p. e70129.

- Wu, R. , et al., Discovery and characterization of NXV01c, an EGFR × cMET bispecific nanobody drug conjugate with potent anti-tumor activity. Cancer Research, 2024. 84(6_Supplement): p. 1871-1871.

- Noel, M.S. , et al., Phase 1/2 trial of the HPK1 inhibitor NDI-101150 as monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab: Clinical update. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2024. 42(16_suppl): p. 3083-3083.

- Papadopoulos, K.P. , et al., Phase 1/2 study of FOG-001, a first-in-class direct β-catenin:TCF inhibitor, in patients with colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and other locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2025. 43(4_suppl): p. TPS322-TPS322.

- Shin, D.-Y. , et al., PHI-101, a Novel FLT3 TKI, Shows Clinical Efficacy in Relapsed/Refractory FLT3-Mutated AML. Blood, 2024. 144: p. 1495.

- Alfa, R. , et al., Clinical pharmacology and tolerability of REC-994, a redox-cycling nitroxide compound, in randomized phase 1 dose-finding studies. Pharmacol Res Perspect, 2024. 12(3): p. e1200.

- Schönherr, H. , et al., Discovery of lirafugratinib (RLY-4008), a highly selective irreversible small-molecule inhibitor of FGFR2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2024. 121(6): p. e2317756121.

- Gamez, J. , et al., A proof-of-concept study with SOM3355 (bevantolol hydrochloride) for reducing chorea in Huntington's disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2023. 89(5): p. 1656-1664.

- Krueger, J.G. , et al., Clinical efficacy of TAK-279, a highly selective oral tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor, is associated with modulation of disease and TYK2 pathway biomarkers in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 2024. 91(3): p. AB159.

- Manasson, J. , et al., Preclinical Polypharmacology of S-1117, a Novel Engineered Fc-Fused IgG Degrading Enzyme, for Chronic Treatment of Autoantibody-Mediated Diseases. Blood, 2024. 144(Supplement 1): p. 2562-2562.

- Rao, S. , et al., Therapeutic potential of ISM8207: A novel QPCTL inhibitor, in triple-negative breast cancer and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Annals of Oncology, 2023. 34: p. S201.

- Dedic, N. , et al., SEP-363856, a Novel Psychotropic Agent with a Unique, Non-D(2) Receptor Mechanism of Action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2019. 371(1): p. 1-14.

- Koblan, K.S. , et al., Efficacy and Safety of SEP-363856, a Novel Psychotropic Agent with a Non-D2 Mechanism of Action, in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. CNS Spectrums, 2020. 25(2): p. 287-288.

- Sowell, R.T. , et al., STX-001, a locally administered LNP-formulated self-replicating mRNA that encodes the therapeutic payload IL-12, induces deep systemic immune responses to solid tumors. Cancer Research, 2023. 83(7_Supplement): p. 2731-2731.

- Fakih, M. , et al., Initial results from the phase I, first-in-human study of the covalent, PI3Kα inhibitor TOS-358 in patients with solid tumors, expressing PI3Kα mutations or amplifications. Annals of Oncology, 2024. 35: p. S499-S500.

- Gonciarz, M. , et al., TYK2 as a therapeutic target in the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Immunotherapy, 2021. 13(13): p. 1135-1150.

- Ubel, C. , et al., Establishing the role of tyrosine kinase 2 in cancer. Oncoimmunology, 2013. 2(1): p. e22840.

- Chen, H. , et al., The rise of deep learning in drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today, 2018. 23(6): p. 1241-1250.

- Vamathevan, J. , et al., Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2019. 18(6): p. 463-477.

- Mak, K.-K. and M.R. Pichika, Artificial intelligence in drug development: present status and future prospects. Drug Discovery Today, 2019. 24(3): p. 773-780.

- Patel, V. and M. Shah, Artificial intelligence and machine learning in drug discovery and development. Intelligent Medicine, 2022. 02(03): p. 134-140.

- Moher, D. , et al., Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 2009. 6(7): p. e1000097.

- Alotaiq, N. and D. Dermawan, Advancements in Virtual Bioequivalence: A Systematic Review of Computational Methods and Regulatory Perspectives in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Pharmaceutics, 2024. 16(11): p. 1414.

| Study; Year | AI Technique Used | Drug Discovery Stage | Therapeutic Area | Company/Funding Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dumbrava, EE. et al [44]; 2024 | Structure-Based Drug Design, Virtual Screening, ADMET Prediction, Biomarker Identification | Clinical Phase I | Oncology (TNBC, HGSOC, Endometrial Cancer with TP53 mutation/loss) |

A2A Pharmaceuticals |

| Patel, MR. et al [45]; 2024 | ChemiRise, Orbital Virtual Screening, Intelligent-SAR, Chemi-Net (AI-driven computational drug design, virtual screening, PK/PD prediction) | Clinical Phase I | Oncology (ER+/HER2- Breast Cancer) |

Accutar Biotechnology Inc |

| Niewiarowska, A. et al [46]; 2017 | BERG’s Interrogative Biology® platform + Oak Ridge Frontier supercomputer: Bayesian AI Modeling, Multi-Omics Data Integration, Supercomputing | Clinical Phase II | Oncology (Pancreatic Cancer) |

BERG LLC |

| Xia, S. et al [47]; 2022 | Deep learning for epitope mapping and functional screening, synthetic antigen design, multi-modal AI for antibody optimization | Preclinical | Oncology (HER2+ Breast Cancer) |

Baseimmune |

| Molnar, J. et al [48]; 2025 | Knowledge Graph and Machine Learning for Target Prioritization | Clinical Phase I | Gastroenterology (Ulcerative Colitis) |

BenevolentAI |

| Hartman, G. et al [49]; 2024 | DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) Screening, Computational Modeling, and Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis | Preclinical | Immunology (NLRP3-related) |

BioAge Labs |

| Risinger, R. et al [50]; 2025 | NovareAI: Drug repurposing via big data integration, ML-based target identification, predictive modeling for trial design | Clinical Phase Ib/II | Neuropsychiatry (Dementia/Agitation) |

BioXcel Therapeutics |

| Rotta, M. et al [51]; 2024 | AI-driven FUSION™ System: Target ID, molecular modeling, PK/PD modeling, biomarker stratification | Clinical Phase I | Oncology (Acute myeloid leukemia/AML) |

Biomea Fusion Inc |

| Patel, J. et al [52]; 2024 | AI-based MAP platform for mutation analysis, allosteric site prediction, compound optimization, PK/PD modeling | Clinical Phase II | Oncology (Glioblastoma, non-small cell lung cancer/NSCLC) |

Black Diamond Therapeutics |

| Idowu, O. et al [53]; 2023 | AI-driven epitope prediction, multi-omic integration, biomarker stratification, and predictive modeling via RAD platform | Clinical Phase I/II | Oncology (Advanced solid tumors) | Cancer Research UK |

| Grant, S. et al [54]; 2023 | Machine Learning (target identification from scRNA-seq data via SCOPE platform) | Preclinical to Clinical Phase I | Gastroenterology (Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease) |

Celsius Therapeutics |

| Dumbrava, E. et al [55]; 2021 | Unigen™: Machine learning–based predictive target discovery, AI-driven antibody design, spatial transcriptomics integration, and combination therapy modeling | Clinical Phase I | Oncology (Advanced Solid Tumors) |

Compugen Ltd |

| Khairnar, V. et al [56]; 2023 | Flex-NK™ platform: Computational antibody design, gene expression profiling, in vitro and in vivo modeling, combination therapy optimization using AI-driven analyses and structural modeling | Preclinical | Oncology (Multiple Myeloma) |

Cytovia Therapeutics |

| Salto, MS. et al [57]; 2024 | Generative AI for compound design, reinforcement learning for chemical space exploration, physics-based simulations for binding affinity optimization, automated synthesis and screening | Preclinical | Immunology (Rheumatoid Arthritis) |

DeepCure Inc |

| Xu, C. et al [58]; 2023 | IDInVivo platform: AI-driven in vivo gene targeting, preclinical efficacy modeling, PK/PD prediction, biomarker identification | Preclinical | Infectious Diseases (Hepatitis B) | Drug Farm |

| Wong, G [59]; 2024 | AI-driven target discovery (Precision Insights), siRNA design (siRCH), pharmacokinetics modeling, biomarker-based stratification | Preclinical to Clinical Phase I | Pulmonary (Chronic Lung Disease) |

Empirico |

| Khattak, A. et al [60]; 2023 | AI-Immunology™ platform (PIONEER™): Neoantigen prediction, ML, immune response modeling | Clinical Phase II | Oncology (Melanoma) |

Evaxion Biotech |

| Diaz, N. et al [61]; 2023 | Generative design, machine learning for predictive modeling, simulation-guided clinical trial design | Clinical Phase I | Oncology (Renal cell carcinoma/RCC, NSCLC) |

Exscientia and Evotec |

| Eckstein, F. et al [62]; 2020 | AI-assisted MRI segmentation and quantitative MRI (qMRI) analysis, location-independent cartilage change analysis, post-hoc data analysis | Clinical Phase II | Rheumatology (Knee Osteoarthritis) |

Formation Bio |

| Keating, AT. et al [63]; 2024 | AI-driven chemoproteomics, Druggability Atlas™ construction, covalent fragment-based drug discovery, machine learning, predictive modeling of resistance mechanisms | Clinical Phase I/II | Oncology (KRASG12C Mutant Tumors: NSCLC, PDAC, CRC) |

Frontier Medicines |

| Wentzel, K. et al [64]; 2024 | GV20's STEAD platform: AI-driven target discovery, antibody sequence prediction, and functional genomics integration | Clinical Phase I/II | Oncology (Advanced solid tumors) |

GV20 Therapeutics |

| Guzman, B. et al [65]; 2023 | Magellan™ AI platform for allosteric modulator discovery, Structural modeling, Predictive modeling (PK/PD), Biomarker identification | Preclinical | Neurology (Parkinson’s Disease) |

Gain Therapeutics |

| Alwis, DD. et al [66]; 2025 | Machine learning (Generate Platform) + iterative computation-experimentation loop | Clinical Phase I | Infectious Diseases (COVID-19 prophylaxis) | Generate Biomedicines |

| Spira, AI. et al [67]; 2022 | Generative AI, Multi-Modal Predictive Modeling, Convolutional Neural Networks | Clinical Phase I | Oncology (Solid tumors including EBV+ gastric cancer, ccRCC, melanoma, mesothelioma) | HiFiBiO Therapeutics |

| Sanborn, RE. et al [68]; 2024 | Smart Allostery™ platform: AI-driven data mining, computational modeling | Clinical Phase I/II | Oncology (Advanced solid tumors) | HotSpot Therapeutics |

| Ahnert, JR. et al [69]; 2023 | RAD platform (AI-driven epitope prediction), mAbPredictAI (AI-guided antibody design), cross-species AI analysis, systems biology integration | Clinical Phase I | Oncology (TNBC, NSCLC, other solid tumors) | Hummingbird Bioscience |

| Adjei, AA. et al [70]; 2024 | Iambic AI: Physics-informed AI drug discovery platform | Clinical Phase I/Ib | Oncology (HER2-driven solid tumors) |

Iambic Therapeutics |

| Ren, F. et al [71]; 2025 | Chemistry42: Generative Models and Reinforcement Learning | Clinical Phase III | Pulmonary (Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis /IPF) |

Insilico Medicine |

| Kim, H. et al [72]; 2024 | AI-driven secretome mining, quantitative proteomics, and phenotypic validation | Preclinical | Endocrinology (Diabetes Type 1) |

Juvena Therapeutics |

| Leber, A. et al [73]; 2023 | LANCE® AI Platform, TITAN-X AI Platform: machine learning, multiscale modeling, predictive analytics, and bioinformatics | Clinical Phase II | Gastroenterology (Ulcerative Colitis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease/IBD) |

Landos Biopharma |

| McKean, W. et al [74]; 2024 | RADR® AI platform for identifying DNA repair vulnerabilities, biomarker signatures, and mechanism of action of LP-284 | Clinical Phase I/Ib | Oncology (Relapsed/Refractory B-cell NHL, Solid Tumors) |

Lantern Pharma Inc |

| Huang, Y. et al [75]; 2024 | AiLNP (Artificial Intelligence Lipid Nanoparticle) platform for lipid formulation optimization; AiTEM (Artificial Intelligence Therapeutic Engine for mRNA) for mRNA therapeutic candidate optimization. | Preclinical | Oncology (Hepatocellular Carcinoma) |

METiS Pharmaceuticals |

| Wang, S. et al [76]; 2024 | Deep learning, AI-based identification, and screening using IBM Watson | Preclinical | Infectious Diseases (Veterinary Bacterial Infections) | MIT and IBM Watson |

| Verstockt, B. et al [77]; 2024 | AI-powered precision medicine (TITAN-X Platform) for target discovery, biomarker identification, and trial optimization | Clinical Phase I/Ib | Gastroenterology (Ulcerative Colitis) |

MedChemExpress, NIMML Institute |

| Khanna, D. et al [78]; 2024 | Machine learning, QSAR models | Clinical Phase II | Dermatology (Skin diseases, autoimmune, fibrotic disorders) |

Medi-Tate and Medidata AI |

| Hussain, A. et al [79]; 2025 | Schrödinger LiveDesign platform: Computational modeling, structural biology, machine learning | Clinical Phase IIa | Gastroenterology (Ulcerative Colitis) | Morphic Therapeutic, Schrödinger, Lilly |

| Leber, A. et al [80]; 2025 | TITAN-X Precision Medicine Platform: Gene expression analysis, Predictive modeling, Multiomics data integration, Mechanistic modeling, Pharmacokinetic simulations | Clinical Phase I | Immunology (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus/SLE) |

NImmune, MedPath, BioSpace |

| Wu, R. et al [81]; 2024 | neoBiologics™ and neoDegrader™ (AI for antibody design, protein degradation, PPI analysis, and immunogenicity prediction) | Preclinical to Clinical Phase I | Oncology (NSCLC, gastric, liver, esophageal tumors) |

NeoX Biotech |

| Noel, MS. et al [82]; 2024 | Structure-based drug design, machine learning-based predictive modeling, medicinal chemistry optimization | Clinical Phase I/II | Oncology (Solid tumors) |

Nimbus Therapeutics |

| Papadopoulos, KP. et al [83]; 2025 | AI-Driven Helicon Design, Computational Physics Integration, Data Science for Trial Optimization | Clinical Phase I/II | Oncology (Solid tumors) |

Parabilis Medicines |

| Shin, DY. et al [84]; 2024 | AI-driven Chemiverse Platform: Target Identification, Compound Screening, ADMET Prediction | Clinical Phase I/II | Oncology (Acute Myeloid Leukemia) |

Pharos iBio |

| Alfa, R. et al [85]; 2024 | Recursion OS: AI-driven drug discovery (deep learning, machine vision, predictive modeling, computational chemistry) | Clinical Phase I | Neurology (Cerebral Cavernous Malformations) |

Recursion Pharmaceuticals |

| Schönherr, H. et al [86]; 2024 | Dynamo™ platform: Motion-Based Drug Design (MBDD), Molecular Dynamics Simulations, Machine Learning, AI-Driven Modeling | Clinical Phase I | Oncology (Solid Tumors, Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma) |

Relay Therapeutics |

| Gamez, J. et al [87]; 2023 | SOMAIPRO platform: AI-driven computational techniques to identify new mechanisms of action, predict drug-target interactions, and repurpose existing drugs for new indications | Clinical Phase II | Neurology (Huntington’s Disease) |

SOM Biotech |

| Krueger, JG. et al [88]; 2024 | Deep learning, molecular dynamics simulations, free energy perturbation (FEP) | Clinical Phase III | Dermatology (Psoriasis) |

Schrödinger Inc |

| Manasson, J. et al [89]; 2024 | IMPACT platform: Machine learning-driven AI for IgG protease design, Deimmunization (epitope elimination), Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling, and multi-mechanistic targeting for optimal drug performance | Preclinical | Immuno-oncology (Thrombocytopenia/ITP and Evans syndrome) | Seismic Therapeutic |

| Rao, S. et al [90]; 2023 | Pharma.AI: Deep Learning, Reinforcement Learning, and Generative Chemistry | Preclinical | Oncology (Triple-negative breast cancer, B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma) |

Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical Development Co. Ltd, Insilico Medicine |

| Dedic, N. et al [91]; 2019 | SmartCube® platform (phenotypic screening, computer vision, machine learning) | Preclinical to Clinical Phase I | Neurology (Schizophrenia) |

Sumitomo Pharma and PsychoGenics |

| Koblan, KS. et al [92]; 2020 | SmartCube® platform (phenotypic screening, computer vision, machine learning) | Clinical Phase II | Neurology (Schizophrenia) |

Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc |

| Sowell, RT. et al [93]; 2023 | AI/ML-enabled target discovery, compound generation, and ADMET prediction | Preclinical | Oncology (Solid Tumors) |

Supercede Therapeutics |

| Fakih, M. et al [94]; 2024 | DNA-Encoded Library Screening, Machine Learning | Clinical Phase I | Oncology (Cancer) |

Totus Medicines |

| Criteria Type | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Study Type | Peer-reviewed original research articles, white papers, or technical reports focusing on AI-driven drug discovery or development | Editorials, opinion pieces, reviews, commentaries, preprints, general reviews without AI focus, or unverified grey literature |

| AI Method | Studies applying machine learning, deep learning, natural language processing, generative AI, reinforcement learning, or knowledge graph-based models | Studies based solely on rule-based systems, deterministic algorithms, or expert systems without adaptive or learning capabilities |

| Application Focus | Application of AI in drug discovery pipeline stages: target identification, hit/lead optimization, compound screening, preclinical evaluation, IND submission | Studies focused on AI in diagnostics, radiology, electronic health records, hospital operations, marketing, or unrelated computational biology applications |

| Outcome Measures | Studies reporting on outcomes such as candidate nomination, time-to-lead, IND approval acceleration, development timeline reduction, or pipeline productivity | Studies lacking measurable outcomes or reporting only theoretical models without downstream drug development relevance |

| Language | Published in English | Published in languages other than English |

| Publication Date | Published between January 2015 and April 2025 | Published before January 2015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).