Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

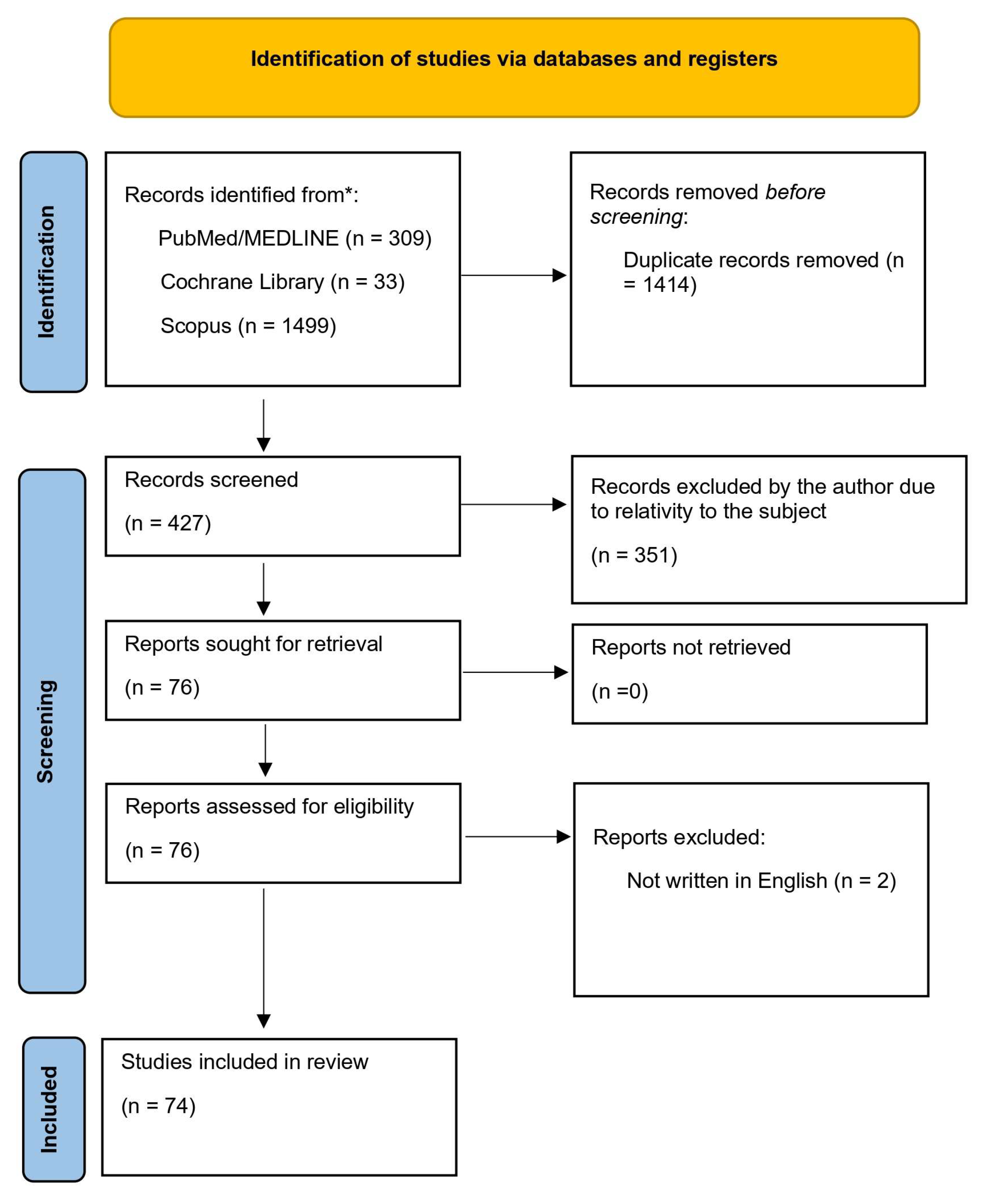

2. Materials and Methods

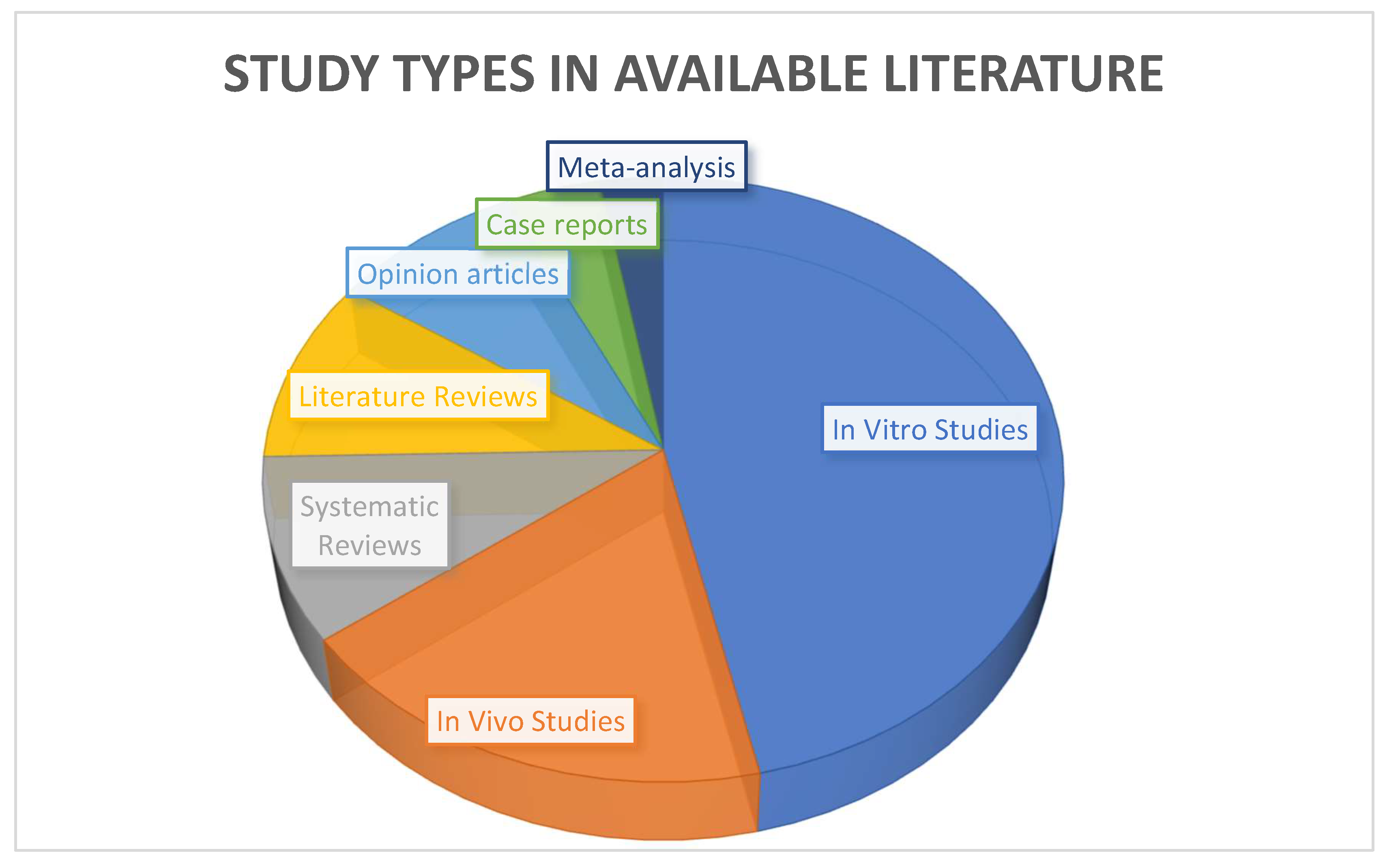

3. Results.

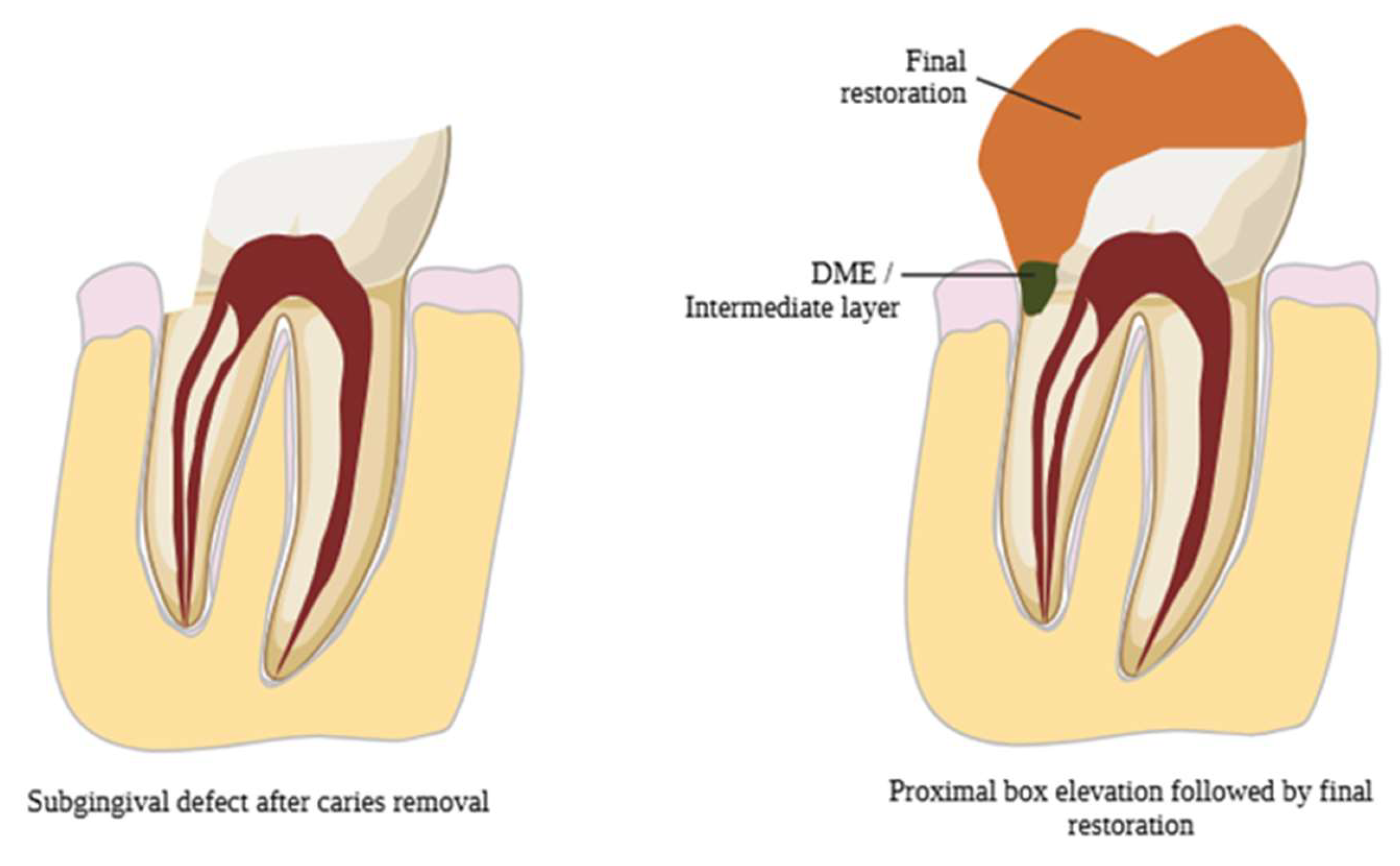

3.1. Evolution of DME

3.2. Indications for DME

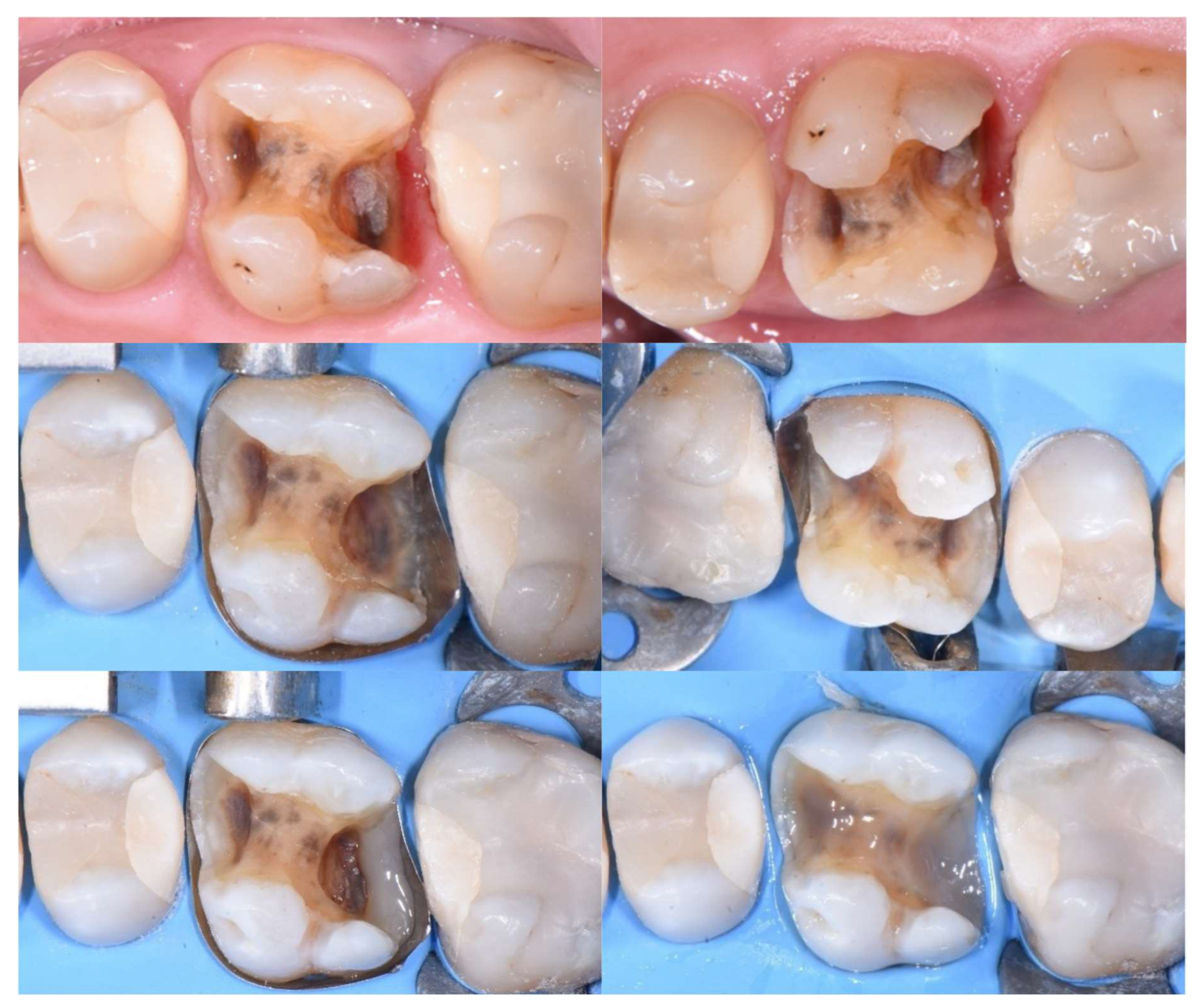

3.3. DME Technique

3.4. Microleakage & Marginal Adaptation

| Authors | Type of study | Bonding agent used | Means of evaluation | Results |

| Daghrery et al [34], 2024 | In vitro study | Total etch and 8th generation bonding agent | After thermal loading, marginal adaptation was assessed by measuring the vertical gaps between the lithium disilicate crown, the restorative material, and the underlying tooth structure. | Bulk fill flowable composite and bioactive composite demonstrated acceptable marginal adaptation. Glass ionomer cement produced the greatest change in vertical marginal adaptation. |

| Reddy et al [35], 2024 | In vitro study | Total etch and 5th generation bonding agent | Samples were examined for microleakage using confocal laser microscopy, and for interface integrity using scanning electron microscopy. | The use of glass ionomer cement (GIC) with hydroxyapatite addition ensures better marginal adaptation compared to flowable resins, but flowable resins create a more homogeneous surface. |

| Sadeghnezhad et al [1], 2024 | Meta-analysis | N/A | Data analysis was done by biostat software, 7 studies were included. | The use of DME had a positive effect in reducing microleakage compared to indirect restorations with subgingival extension. |

| Baldi et al [31], 2023 | In vitro study | Self-etch bonding agent | Specimens were scanned with micro-CT before after thermomechanical loading. | Flowable composites exhibited fewer interfacial gaps than nanohybrid composite. |

| Ismail HS et al [36], 2022 | Systematic review | N/A | Marginal adaptation was evaluated using a low vacuum scanning electron microscope. | Bulk-fill composites are recommended for proximal cavities with dentin/cementum margins, while RMGIs are better suited for poor moisture control or high caries risk. Despite bonding challenges, various adhesive protocols have shown comparable outcomes. |

| Vichitgomen et al [37], 2021 | In vitro study | 5th generation bonding agent | Marginal sealing ability at different interfaces was evaluated with a stereomicroscope at 40x magnification by scoring the depth of silver nitrate penetrating along the adhesive surfaces. | Microleakage was similar between DME and subgingival indirect restorations, but significantly higher with resin-modified glass ionomer cements. |

| Zhang et al [38], 2021 | In vitro study | Total etch | Specimens were coated with two layers of nail varnish extending 1 mm beyond the crown margins and immersed in a 0.55% methylene blue solution. Gingival microleakage was then evaluated under a stereomicroscope. | In endodontically treated teeth restored with an endocrown extending into the pulpal chamber, DME increased fracture resistance but did not reduce microleakage levels. |

| Jawaed et al [32], 2016 | In vitro study | Total etch | Specimens were sealed with acid-resistant varnish, leaving a 1 mm margin around the cervical area, and immersed in 2% buffered methylene blue solution for 24 hours. Microleakage was evaluated under a stereomicroscope, scored (0–4), and measured in millimeters. | The "snowplow" technique ensures lower microleakage in DME situations, because it reduces the thickness of the flowable resin at the base, which—due to its lower filler content—exhibits greater polymerization shrinkage. |

| Spreafico et al [21], 2016 | In vitro study | 4th generation bonding agent | Gold-sputtered epoxy replicas mounted on aluminum stubs were examined under SEM at 50X magnification. | No statistically significant differences in microleakage levels were found between margins with and without DME for indirect restorations. |

| Frankenberger et al [39], 2012 | In vitro study | Self-adhesive resin cements; | Microgaps were analyzed with SEM Analysis. | Direct bonding of glass ceramics to dentin showed the fewest microgaps (92%), followed by bonding to three-layered composite resin (84%), while repositioning with self-curing resin cement resulted in significantly more microgaps. |

| Stockton et al [33], 2007 | In vitro study | 5 groups: total etch; 6th generation; 7th generation; resin-modified-glass-ionomer-cement | Marginal integrity was measured by the percentage of surface area stained by silver nitrate solution. | On dentin, self-etch systems yielded lower microleakage rates. On enamel, they showed increased rates. |

3.5. Bond Strength & Layering

| Authors | Type of study | Bonding agent used | Means of evaluation | Results |

| Ismail et al [42], 2024 | In vitro study | 7th & 8th generation bonding agents | Specimens underwent μTBS testing after aging. | Light-cured adhesives showed the weakest μTBS to root-proximal dentin, while chemical and dual-cured agents performed comparably. |

| Balci et al [40], 2024 | In vitro study | Bonding agent N/A. Materials used for elevation: flowable composite, condensable composite. |

Static force was applied at an angle of 15° to the point of fracture. Fracture strength was measured and fracture types were examined under x6 magnification. | Flowable and condensable composite resin exhibited similar fracture resistance. |

| Juloski et al [43], 2020 | In vitro study | 7th generation bonding agent | SEM evaluation of marginal adaptation & microleakage evaluation with nail varnish | Self-etching or universal adhesives are recommended for DME to prevent dentin over-etching. |

| de Mattos Pimenta Vidal et al [44], 2012 | In vitro study | 5th generation b.a.; resin-modified-glass-ionomer | Two slabs per tooth were used for μTBS testing and two for nanoleakage assessment, based on penetration length (%) and silver nitrate deposition. | The presence of flowable composite significantly decreased micro tensile bond strength after aging simulation. |

3.6. Periodontal Response

3.7. Failure Rate

4. Discussion

4.1. Material Selection for DME

4.2. Long-Term Performance of DME

4.3. Relationship Between DME and Periodontal Health

4.4. Alternative Techniques for Managing Subgingival Cervical Margins

4.5. Decision-Making and New Classifications

4.6. Clinical Considerations

4.7. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DME | Deep Margin Elevation |

| STA | Supracrestal Tissue Attachment |

| IDS | Immediate Dentin Sealing |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| GIC | Glass Ionomer Cement |

| μTBS | Micro Tensile Bond Strength |

| BoP | Bleeding on Probing |

| PI | Plaque Index |

| PPD | Probing Pocket Depth |

| GI | Gingival Index |

| SCL | Surgical Crown Lengthening |

| RMGIC | Resin Modified Glass Ionomer |

| OE | Orthodontic Extrusion |

References

- Sadeghnezhad P, Sarraf Shirazi A, Borouziniat A, Majidinia S, Soltaninezhad P, Nejat AH. Enhancing subgingival margin restoration: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis of deep margin elevation's impact on microleakage. Evid Based Dent. 2024 Jun 21. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38907025. [CrossRef]

- Aldakheel M, Aldosary K, Alnafissah S, Alaamer R, Alqahtani A, Almuhtab N. Deep Margin Elevation: Current Concepts and Clinical Considerations: A Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022 Oct 18;58(10):1482. [CrossRef]

- Palma, P.J.; Neto, M.A.; Messias, A.; Amaro, A.M. Microtensile Bond Strength of Composite Restorations: Direct vs. Semi-Direct Technique Using the Same Adhesive System. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 203. [CrossRef]

- Alam MN, Ibraheem W, Ramalingam K, Sethuraman S, Basheer SN, Peeran SW. Identification, Evaluation, and Correction of Supracrestal Tissue Attachment (Previously Biologic Width) Violation: A Case Presentation with Literature Review. Cureus. 2024 Apr 12;16(4):e58128. [CrossRef]

- Felemban, M.F.; Khattak, O.; Alsharari, T.; Alzahrani, A.H.; Ganji, K.K.; Iqbal, A. Relationship between Deep Marginal Elevation and Periodontal Parameters: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 1948. [CrossRef]

- Fichera G., Mazzitelli C., Picciariello V., Maravic T., Josic U., Annalisa Mazzoni A., Breschi L. Structurally compromised teeth. Part II: A novel approach to peripheral build up procedures. J Esthet Rest Dent, 2023, 36, 1, 20-31. Special Annual Issue: Advances in Esthetic Dentistry 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B., Shin, J., Jeong, T. et al. Combined treatment of surgical extrusion and crown lengthening procedure for severe crown-root fracture of a growing patient: a case report. BMC Oral Health 24, 1498 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Uravić Crljenica M., Perasso R., Imelio M., Viganoni C., Pozzan L. A systematic and comprehensive protocol for rapid orthodontic extrusion. J Esthet Rest Dent, 2024, 36, 6, 838-844. [CrossRef]

- Tu KW., Kuo CH, Hung CC., Yan DY., Mau JLP. Strategic sequencing of orthodontic treatment and periodontal regenerative surgery: A literature review. J Dent Sci. 2025.(In press). [CrossRef]

- Feu D. Orthodontic treatment of periodontal patients: challenges and solutions, from planning to retention. Dental Press J Orthod. 2020 Nov-Dec;25(6):79-116. [CrossRef]

- Bazos P, Magne P. Bio-Emulation: biomimetically emulating nature utilizing a histoanatomic approach; visual synthesis. Int J Esthet Dent. 2014;9(3):330-52.

- Magne PB. U Biomimetic restorative dentistry. Illinois: Quintessence; 2022.

- Dietschi D, Spreafico R. Current clinical concepts for adhesive cementation of tooth-colored posterior restorations. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1998 Jan-Feb;10(1):47-54; quiz 56. PMID: 9582662.

- Magne, P., Harrington, S., & Spreafico, R. (2012). Deep Margin Elevation: A Paradigm Shift.

- Taylor A, Burns L. Deep margin elevation in restorative dentistry: A scoping review. J Dent. 2024 Jul;146:105066. Epub 2024 May 12. PMID: 38740249. [CrossRef]

- Kwon T, Lamster IB, Levin L. Current Concepts in the Management of Periodontitis. Int Dent J. 2021 Dec;71(6):462-476. Epub 2021 Feb 19. [CrossRef]

- Chun EP, de Andrade GS, Grassi EDA, Garaicoa J, Garaicoa-Pazmino C. Impact of Deep Margin Elevation Procedures Upon Periodontal Parameters: A Systematic Review. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2023 Feb 28;31(1):10-21. PMID: 36446028. [CrossRef]

- University of Derby. Literature Reviews: systematic searching at various levels. Accessed on 28 April 2025 from https://libguides.derby.ac.uk/literature-reviews/prisma-lr.

- Mugri MH, Sayed ME, Nedumgottil BM, Bhandi S, Raj AT, Testarelli L, Khurshid Z, Jain S, Patil S. Treatment Prognosis of Restored Teeth with Crown Lengthening vs. Deep Margin Elevation: A Systematic Review. Materials (Basel). 2021 Nov 8;14(21):6733. [CrossRef]

- Loguercio AD, Alessandra R, Mazzocco KC, Dias AL, Busato AL, Singer Jda M, Rosa P. Microleakage in class II composite resin restorations: total bonding and open sandwich technique. J Adhes Dent. 2002 Summer;4(2):137-44.

- Spreafico R, Marchesi G, Turco G, Frassetto A, Di Lenarda R, Mazzoni A, Cadenaro M, Breschi L. Evaluation of the In Vitro Effects of Cervical Marginal Relocation Using Composite Resins on the Marginal Quality of CAD/CAM Crowns. J Adhes Dent. 2016;18(4):355-62. [CrossRef]

- Welbury RR, Murray JJ. A clinical trial of the glass-ionomer cement-composite resin "sandwich" technique in Class II cavities in permanent premolar and molar teeth. Quintessence Int. 1990, 6, 507-12.

- Andersson-Wenckert IE, van Dijken JW, Kieri C. Durability of extensive Class II open-sandwich restorations with a resin-modified glass ionomer cement after 6 years. Am J Dent. 2004 Feb;17(1):43-50.

- Da Silva Gonçalves D, Cura M, Ceballos L, Fuentes MV. Influence of proximal box elevation on bond strength of composite inlays. Clin Oral Investig. 2017 Jan;21(1):247-254. Epub 2016 Mar 11. PMID: 26969499. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari M, Koken S, Grandini S, Ferrari Cagidiaco E, Joda T, Discepoli N. Influence of cervical margin relocation (CMR) on periodontal health: 12-month results of a controlled trial. J Dent. 2018 Feb;69:70-76. Epub 2017 Oct 20. [CrossRef]

- Ismail EH, Ghazal SS, Alshehri RD, Albisher HN, Albishri RS, Balhaddad AA. Navigating the practical-knowledge gap in deep margin elevation: A step towards a structured case selection - a review. Saudi Dent J. 2024 May;36(5):674-681. Epub 2024 Mar 5. [CrossRef]

- Frese C, Wolff D, Staehle HJ. Proximal box elevation with resin composite and the dogma of biological width: clinical R2-technique and critical review. Oper Dent. 2014 Jan-Feb;39(1):22-31. Epub 2013 Jun 20. PMID: 23786609. [CrossRef]

- Samartzi TK, Papalexopoulos D, Ntovas P, Rahiotis C, Blatz MB. Deep Margin Elevation: A Literature Review. Dent J (Basel). 2022 Mar 14;10(3):48. PMID: 35323250; PMCID: PMC8947734. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh Oskoee P, Dibazar S. Deep margin elevation; Indications and periodontal considerations. J Adv Periodontol Implant Dent. 2024 Nov 6;16(2):91-93. [CrossRef]

- Eggmann F, Ayub JM, Conejo J, Blatz MB. Deep margin elevation-Present status and future directions. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2023 Jan;35(1):26-47. Epub 2023 Jan 5. PMID: 36602272. [CrossRef]

- A Baldi, A Comba, T Rossi, L Monticone, E Berutti, N Scotti, 127 - Effect of flowable viscosities on deep margin elevation: a microCT study, Dental Materials,Volume 39, Supplement 1,2023,Pages e69-e70,ISSN 0109-5641. [CrossRef]

- Jawaed NU, Abidi SY, Qazi FU, Ahmed S. An In-VitroEvaluation of Microleakage at the Cervical Margin Between two Different Class II Restorative Techniques Using Dye Penetration Method. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2016 Sep;26(9):748-52. PMID: 27671178.

- Stockton LW, Tsang ST. Microleakage of Class II posterior composite restorations with gingival margins placed entirely within dentin. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007 Apr;73(3):255. PMID: 17439712.

- Daghrery A, Jabarti E, Baras BH, Mitwalli H, Al Moaleem MM, Khojah MZ, Khayat W, Albar NH. Impact of Thermal Aging on Marginal Adaptation in Lithium Disilicate CAD/CAM Crowns with Deep Proximal Box Elevation. Med Sci Monit. 2025 Feb 3;31:e947191. PMID: 39895039; PMCID: PMC11804129. [CrossRef]

- Reddy KH, Priya BD, Malini DL, Mohan TM, Bollineni S, Gandhodi HC. Deep margin elevation in class II cavities: A comparative evaluation of microleakage and interface integrity using confocal laser microscopy and scanning electron microscopy. J Conserv Dent Endod. 2024 May;27(5):529-534. Epub 2024 May 10. PMID: 38939536; PMCID: PMC11205177. [CrossRef]

- Ismail HS, Ali AI, Mehesen RE, Juloski J, Garcia-Godoy F, Mahmoud SH. Deep proximal margin rebuilding with direct esthetic restorations: a systematic review of marginal adaptation and bond strength. Restor Dent Endod. 2022 Mar 4;47(2):e15. PMID: 35692223; PMCID: PMC9160765. [CrossRef]

- Vichitgomen J, Srisawasdi S. Deep margin elevation with resin composite and resin-modified glass-ionomer on marginal sealing of CAD-CAM ceramic inlays: An in vitro study. Am J Dent. 2021 Dec;34(6):327-332. PMID: 35051321.

- Zhang H, Li H, Cong Q, Zhang Z, Du A, Wang Y. Effect of proximal box elevation on fracture resistance and microleakage of premolars restored with ceramic endocrowns. PLoS One. 2021 May 26;16(5):e0252269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252269. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2021 Sep 23;16(9):e0258038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258038. PMID: 34038489; PMCID: PMC8153463.

- Frankenberger R, Hehn J, Hajtó J, Krämer N, Naumann M, Koch A, Roggendorf MJ. Effect of proximal box elevation with resin composite on marginal quality of ceramic inlays in vitro. Clin Oral Investig. 2013 Jan;17(1):177-83. Epub 2012 Feb 23. PMID: 22358378. [CrossRef]

- Balci ŞN, Tekçe N, Tuncer S, Demirci M. The effect of different deep margin elevation methods on the fracture strength of CAD-CAM restorations. Am J Dent. 2024 Jun;37(3):115-120. PMID: 38899989.

- Magne P, Mori Ubaldini AL. Thermal and bioactive optimization of a unidose 3-step etch-and-rinse dentin adhesive. J Prosthet Dent. 2020 Oct;124(4):487.e1-487.e7. Epub 2020 Jul 16. PMID: 32682525. [CrossRef]

- Ismail HS, Ali AI, Elawsya ME. Influence of curing mode and aging on the bonding performance of universal adhesives in coronal and root dentin. BMC Oral Health. 2024 Oct 5;24(1):1188. PMID: 39369181; PMCID: PMC11456248. [CrossRef]

- Juloski J, KÖken S, Ferrari M. No correlation between two methodological approaches applied to evaluate cervical margin relocation. Dent Mater J. 2020 Aug 2;39(4):624-632. Epub 2020 Apr 16. PMID: 32295986. [CrossRef]

- de Mattos Pimenta Vidal C, Pavan S, Briso AL, Bedran-Russo AK. Effects of three restorative techniques in the bond strength and nanoleakage at gingival wall of Class II restorations subjected to simulated aging. Clin Oral Investig. 2013 Mar;17(2):627-33. Epub 2012 May 11. PMID: 22576325. [CrossRef]

- Hausdörfer T, Lechte C, Kanzow P, Rödig T, Wiegand A. Periodontal health in teeth treated with deep-margin-elevation and CAD/CAM partial lithium disilicate restorations-a prospective controlled trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2024 Nov 30;28(12):670. PMID: 39613879; PMCID: PMC11606998. [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi C, Brambilla G, Conti A, Dosoli R, Ceroni F, Ferrantino L. Cervical margin relocation: case series and new classification system. Int J Esthet Dent. 2019;14(3):272-284. PMID: 31312813.

- Bertoldi C, Monari E, Cortellini P, Generali L, Lucchi A, Spinato S, Zaffe D. Clinical and histological reaction of periodontal tissues to subgingival resin composite restorations. Clin Oral Investig. 2020 Feb;24(2):1001-1011. Epub 2019 Jul 8. PMID: 31286261. [CrossRef]

- Oppermann RV, Gomes SC, Cavagni J, Cayana EG, Conceição EN. Response to Proximal Restorations Placed Either Subgingivally or Following Crown Lengthening in Patients with No History of Periodontal Disease. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2016 Jan-Feb;36(1):117-24. PMID: 26697548. [CrossRef]

- Padbury A Jr, Eber R, Wang HL. Interactions between the gingiva and the margin of restorations. J Clin Periodontol. 2003 May;30(5):379-85. PMID: 12716328. [CrossRef]

- Bresser RA, Gerdolle D, van den Heijkant IA, Sluiter-Pouwels LMA, Cune MS, Gresnigt MMM. Up to 12 years clinical evaluation of 197 partial indirect restorations with deep margin elevation in the posterior region. J Dent. 2019 Dec;91:103227. Epub 2019 Nov 4. PMID: 31697971. [CrossRef]

- Cieplik F, Hiller KA, Buchalla W, Federlin M, Scholz KJ. Randomized clinical split-mouth study on a novel self-adhesive bulk-fill restorative vs. a conventional bulk-fill composite for restoration of class II cavities - results after three years. J Dent. 2022 Oct;125:104275. Epub 2022 Aug 28. PMID: 36044948. [CrossRef]

- Roggendorf MJ, Krämer N, Dippold C, Vosen VE, Naumann M, Jablonski-Momeni A, Frankenberger R. Effect of proximal box elevation with resin composite on marginal quality of resin composite inlays in vitro. J Dent. 2012 Dec;40(12):1068-73. Epub 2012 Sep 7. PMID: 22960537. [CrossRef]

- Kuper NK, Opdam NJ, Bronkhorst EM, Huysmans MC. The influence of approximal restoration extension on the development of secondary caries. J Dent. 2012 Mar;40(3):241-7. Epub 2011 Dec 27. PMID: 22226997. [CrossRef]

- Amesti-Garaizabal A, Agustín-Panadero R, Verdejo-Solá B, Fons-Font A, Fernández-Estevan L, Montiel-Company J, Solá-Ruíz MF. Fracture Resistance of Partial Indirect Restorations Made With CAD/CAM Technology. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2019 Nov 9;8(11):1932. PMID: 31717610; PMCID: PMC6912690. [CrossRef]

- Butt, Aftab. (2021). Cervical margin relocation and indirect restorations: Case report and literature review. Dental Update. 48. 93-97. [CrossRef]

- Onur Adson, Taha Yasin Sarıkaya, Bolay Şükran,,Margin Elevation for Posterior İndirect Restorations: 6-Month Clinical Outcomes, International Dental Journal, Volume 74, Supplement 1, 2024, Page S176, ISSN 0020-6539. [CrossRef]

- Gözetici-Çil B, Öztürk-Bozkurt F, Genç-Çalışkan G, Yılmaz B, Aksaka N, Özcan M. Clinical Performance of Posterior Indirect Resin Composite Restorations with the Proximal Box Elevation Technique: A Prospective Clinical Trial up to 3 Years. J Adhes Dent. 2024 Jan 26;26:19-30. PMID: 38276889; PMCID: PMC11740769. [CrossRef]

- Aziz AM, Suliman S, Sulaiman TA, Abdulmajeed A. Clinical and radiographical evaluation of CAD-CAM crowns with and without deep margin elevation: 10-year results. J Prosthet Dent. 2024 May 8:S0022-3913(24)00291-9. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38724338 . [CrossRef]

- Muscholl C, Zamorska N, Schoilew K, Sekundo C, Meller C, Büsch C, Wolff D, Frese C. Retrospective Clinical Evaluation of Subgingival Composite Resin Restorations with Deep-Margin Elevation. J Adhes Dent. 2022 Aug 19;24:335-344. PMID: 35983705. [CrossRef]

- Baldi A, Rossi T, Comba A, Monticone L, Paolone G, Sannino I, Vichi A, Goracci C, Scotti N. Three-Dimensional Internal Voids and Marginal Adaptation in Deep Margin Elevation Technique: Efficiency of Highly Filled Flowable Composites. J Adhes Dent. 2024 Oct 14;26:223-230. PMID: 39397757. [CrossRef]

- De Goes MF, Giannini M, Di Hipólito V, Carrilho MR, Daronch M, Rueggeberg FA. Microtensile bond strength of adhesive systems to dentin with or without application of an intermediate flowable resin layer. Braz Dent J. 2008;19(1):51-6. PMID: 18438560. [CrossRef]

- Ölçer Us Y, Aydınoğlu A, Erşahan Ş, Erdem Hepşenoğlu Y, Sağır K, Üşümez A. A comparison of the effects of incremental and snowplow techniques on the mechanical properties of composite restorations. Aust Dent J. 2024 Mar;69(1):40-48. Epub 2023 Oct 9. PMID: 37814190. [CrossRef]

- Francois P, Attal JP, Fasham T, Troizier-Cheyne M, Gouze H, Abdel-Gawad S, Le Goff S, Dursun E, Ceinos R. Flexural Properties, Wear Resistance, and Microstructural Analysis of Highly Filled Flowable Resin Composites. Oper Dent. 2024 Sep 1;49(5):597-607. PMID: 39169507 . [CrossRef]

- Lefever D, Gregor L, Bortolotto T, Krejci I. Supragingival relocation of subgingivally located margins for adhesive inlays/onlays with different materials. J Adhes Dent. 2012 Dec;14(6):561-7. PMID: 22724114. [CrossRef]

- Juloski J, Köken S, Ferrari M. Cervical margin relocation in indirect adhesive restorations: A literature review. J Prosthodont Res. 2018 Jul;62(3):273-280. Epub 2017 Nov 15. [CrossRef]

- Wu F, Su X, Shi Y, Bai J, Feng J, Sun X, Wang X, Wang H, Wen J, Kang J. Comparison of the biomechanical effects of the post-core crown, endocrown and inlay crown after deep margin elevation and its clinical significance. BMC Oral Health. 2024 Aug 23;24(1):990. [CrossRef]

- Guo J, Wang Z, Li X, Sun C, Gao E, Li H. A comparison of the fracture resistances of endodontically treated mandibular premolars restored with endocrowns and glass fiber post-core retained conventional crowns. J Adv Prosthodont. 2016 Dec;8(6):489-493. Epub 2016 Dec 15. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi Yamchi F, Abbasi M, Atri F, Ahmadi E. Influence of Deep Margin Elevation Technique With Two Restorative Materials on Stress Distribution of e.max Endocrown Restorations: A Finite Element Analysis. Int J Dent. 2024 Nov 27;2024:6753069. [CrossRef]

- Bresser RA, Carvalho MA, Naves LZ, Melma H, Cune MS, Gresnigt MMM. Biomechanical behavior of molars restored with direct and indirect restorations in combination with deep margin elevation. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2024 Apr;152:106459. Epub 2024 Feb 12. [CrossRef]

- Sarfati A, Tirlet G. Deep margin elevation versus crown lengthening: biologic width revisited. Int J Esthet Dent. 2018;13(3):334-356. PMID: 30073217.

- van Dijken JW, Sjöström S, Wing K. The effect of different types of composite resin fillings on marginal gingiva. J Clin Periodontol. 1987 Apr;14(4):185-9. [CrossRef]

- Reichardt E, Krug R, Bornstein MM, Tomasch J, Verna C, Krastl G. Orthodontic Forced Eruption of Permanent Anterior Teeth with Subgingival Fractures: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Nov 29;18(23):12580. PMID: 34886307; PMCID: PMC8656787. [CrossRef]

- Plotino G, Abella Sans F, Duggal MS, Grande NM, Krastl G, Nagendrababu V, Gambarini G. Present status and future directions: Surgical extrusion, intentional replantation and tooth autotransplantation. Int Endod J. 2022 May;55 Suppl 3:827-842. Epub 2022 Mar 30. [CrossRef]

- Veneziani M. Adhesive restorations in the posterior area with subgingival cervical margins: new classification and differentiated treatment approach. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2010 Spring;5(1):50-76.

- Dablanca-Blanco AB, Blanco-Carrión J, Martín-Biedma B, Varela-Patiño P, Bello-Castro A, Castelo-Baz P. Management of large class II lesions in molars: how to restore and when to perform surgical crown lengthening? Restor Dent Endod. 2017 Aug;42(3):240-252. Epub 2017 Aug 3. [CrossRef]

| Authors | Type of study | Means of evaluation | Results |

| Hausdörfer et al [45], 2024 | Prospective controlled clinical trial | Following DME combined with indirect restoration, periodontal response was assessed with BoP, PI, PPD with a follow-up of 1 year | Proximal boxes treated with DME were correlated with increased risk of gingival inflammation. |

| Felemban et al [5], 2023 | Systematic review | 68 articles were included | If the cervical margin is <2 mm from the bone crest, DME is contraindicated, and surgical crown lengthening (SCL) should be performed. |

| Ghezzi et al [46], 2019 | Case series | Periodontal response was assessed with BoP | When the supracrestal tissue attachment (STA) is respected (>2.04 mm from the bone crest), DME is compatible with periodontal health, with reduced bleeding on probing observed over 12 months. |

| Bertoldi et al [47], 2019 | Clinical study | Periodontal response was assessed with full-mouth plaque and bleeding score, focal probing depth. | The DME technique is compatible with periodontal health, at levels similar to intact tooth surfaces. |

| Ferrari et al [25], 2017 | Clinical study | Periodontal response was assessed with BoP, GI, and PI. | A flat contour of the intermediate layer after deep margin elevation (DME) has been associated with intense inflammatory infiltration and subsequent bone resorption, while clinical observations reported an increased incidence of bleeding on probing around DME-treated surfaces; however, although elevated bleeding on probing was also noted at 12 months post-treatment, no bone resorption was detected, likely due to the insufficient follow-up period. |

| Oppermann et al [48] | Clinical study | Periodontal response was assessed with BoP, GI, and PI. | It was observed that subgingivally placed restorations had comparable behavior to sites treated with crown lengthening. |

| Padbury et al [49], 2003 | Literature review | Periodontal response was assessed with BoP and probing depth. | Overextended material near soft tissues can severely compromise periodontal health. |

| Authors | Type of study | Type of failure | Results |

| Adson et al [56], 2024 | Retrospective clinical stydy | Failures included marginal integrity (n=1) | Out of 50 indirect partial restorations with DME, the 6-months survival rate was 98%. |

| Gözetici-Çil et al [57], 2024 | Retrospective clinical study | Failures included: partial loss (n=5), material chipping (n=4), secondary caries (n=1) | Out of 80 indirect partial composite restorations with DME, the 3-year survival rate was 93.8%. |

| Aziz et al [58], 2024 | Retrospective clinical study | Failures included: secondary caries (n=15), pulpal necrosis (n=4), crown fractures (n=4), loss of crown retention (n=3) | Out of 153 restorations with DME and CAD/CAM crowns, the 10-year survival rate was 95.8%, with no significant differences between groups with or without DME. |

| Muscholl et al [59], 2022 |

Retrospective clinical study | No failures were recorded. Periodontal parameters assessed included bleeding on probing, gingival bleeding index, and plaque control record. | Out of the 60 participants included, no failures were recorded in a follow-up range of 2.70 ± 1.90 years. |

| Bresser et al [50], 2019 | Retrospective clinical study | Failures included: secondary caries (n=5), pulpal necrosis (n=1), severe periodontal breakdown (n=1) and fracture (n=1) | Out of the 197 restorations with DME included, 8 failures occurred between 46-57 months. |

| Kuper et al [53], 2011 | Retrospective clinical study | Failures included: secondary caries (n=44), fracture tooth (n=6), fracture restoration (n=8), extraction (n=10), other/unknown (n=4) | Out of 344 composite restorations with margins apical to the CEJ, 72 failures were recorded, with no details provided on material selection or layering technique. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).