1. Introduction

Walking is a fundamental mode of human locomotion, essential to preserve functional independence and perform activities of daily living [

1]. An efficient walking requires adequate coordination, which stems from the fine tuning of the degrees of freedom of the musculoskeletal segments involved in the gait cycle. However, several factors, including neurological disorders, musculoskeletal impairments, and physiological processes, such as aging, can alter gait execution [

2,

3]. The aging process is an inherent aspect of human biology that induces progressive that motor and cognitive changes significantly affect walking. In fact, these changes may lead to impaired coordination, which in turn may affect balance and overall gait stability [

4]. These alterations not only compromise mobility and independence but also increase the risk of falls, significantly affecting the ability to perform activities of daily living, and constituting a major global health problem [

5]. Research has also shown that ageing plays a crucial role in altering executive functions, attention and motor planning, and such cognitive changes can further impact coordination, exacerbating gait instability [

6]. Based on current knowledge, we believe that assessing gait kinematic coordination in relation to age and cognitive status may be relevant for identifying potential areas of intervention at both the motor and cognitive levels. Nevertheless, the literature still lacks a thorough investigation of these aspects. On one hand, most studies derive coordination indices from spatiotemporal gait features, such as variability and asymmetry, without considering the complex interactions between different body segments [

7,

8]. On the other hand, the cognitive dimension of physiological aging in relation to gait coordination remains poorly explored. These studies generally report a decline in inter-limb coordination [

9,

10], which, in some cases, is also associated with walking speed, a parameter known to decrease with advancing age [

11].

Moreover, Swanson & Fling further characterized this knowledge by demonstrating a relationship between coordination and motor cortex inhibition in older adults [

12]. Specifically, the authors reported that, unlike in young adults, greater inhibition of the motor cortex appeared to benefit gait coordination in older adults. Concerning the metrics used to define coordination, the phase coordination index (PCI) appears to be one of the most commonly used (Gimmon et al., 2018; Zadik et al., 2022). This index is based on the temporal aspects of steps and strides, and measures the accuracy and consistency of the phase relationship between the lower limbs during walking. However, despite its usefulness (particularly as a highly synthetic index), the PCI does not consider the spatio-temporal interactions among joints which are a key factor for determining coordination [

14]. In addition, since PCI is derived from average values calculated over multiple gait cycles, its application requires extended walking trials, which may be challenging or uncomfortable for some individuals [

15]. Indeed, to cite Turvey “coordination necessarily involves bringing into proper relation multiple and different component parts” [

16]. More in-depth analyses have instead been conducted by estimating coordination through the continuous relative phase between joints’ kinematics. However, in this case, the number of studies is limited, as is the number of joints involved in the analysis, which are almost exclusively intra-limb [

17,

18]. To address this limitation, we chose to apply network analysis to joint kinematics during gait. This approach, previously employed to analyze coordination between different parts of the body, is based on the use of a correlation matrix [

19,

20].

This matrix, named kinectome, represents kinematic interactions between pairs of joints (inter- and intra-limb). It consists of nodes, which correspond to joints, and links, which indicate correlation values and describe the degree of coordination between different joint pairs. This detailed mathematical description showed significant specificity for both subjects and movements and was able to describe movement patterns of coordination in both physiological and pathological conditions [

21,

22,

23]. By means of kinectomes, our aim is to investigate whether a relationship between gait coordination and both age and cognitive status exists, to then determine which specific joints are involved. Our hypotheses are that 1) capacity to coordinate lower limbs gets worse with advanced age; 2) the cognitive condition may be related to the coordination ability; 3) different joints are differently influenced by age and cognition. To test these hypotheses we used a stereophotogrammetric system to record gait from fifty-six healthy individuals. Network-based features of lower limbs joints were then extracted and correlation tests with age and cognitive scores were carried out.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

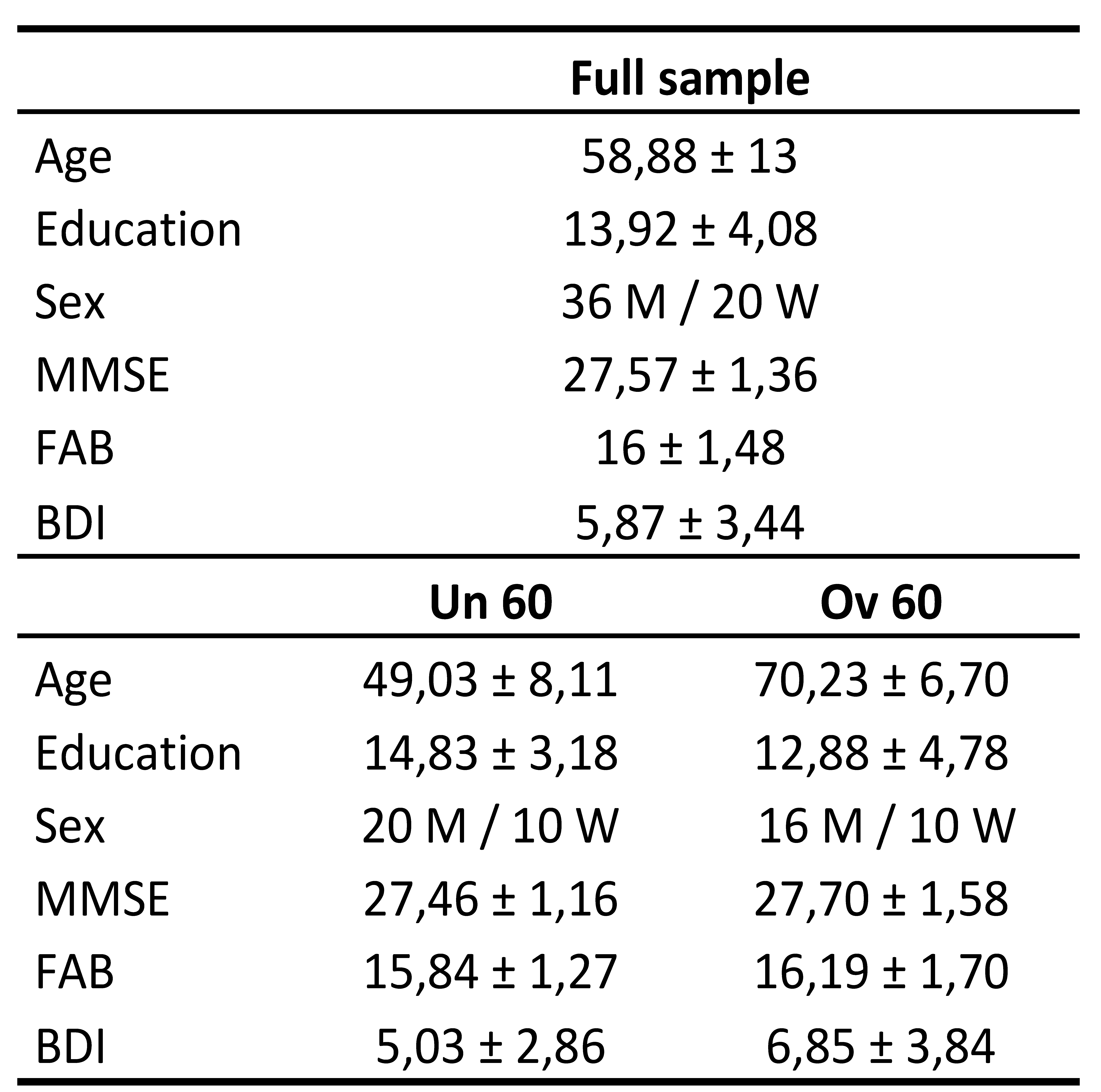

Fifty-six healthy subjects were recruited, consisting of 36 males and 20 females. The group included 30 participants under the age of 60 and 26 participants aged 60 and above. Demographic and cognitive data were collected as exclusion criteria and to perform further analysis. For testing cognitive conditions, participants performed neurological and psychological tests such as: Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [

24], Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) [

25], Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [

26] (Table. 1). The MMSE is a copyrighted instrument originally developed by Folstein et al. (1975), with distribution rights currently held by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. (PAR). In this study, the MMSE was administered exclusively for non-commercial, academic purposes, in compliance with fair use provisions. Exclusion criteria were: FAB < 12; MMSE < 24; BDI > 13; Intake psychoactive drugs; Physical or neurological condition leading to motor impairment.

Table 1.

Participants’ information. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the full sample and age subgroups (mid adults - under 60 years old - and older adults - over 60 years old). Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; FAB: Frontal Assessment Battery; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory.

Table 1.

Participants’ information. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the full sample and age subgroups (mid adults - under 60 years old - and older adults - over 60 years old). Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; FAB: Frontal Assessment Battery; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Psychological Research of the Department of Humanities of the University of Naples Federico II (protocol code 26/2020 approved on 10/9/2020).

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

2.2. Recording System and Processing Pipeline

The acquisitions were conducted at the Motion Analysis Laboratory of the University of Naples Parthenope. The gait data was collected using a stereophotogrammetric system comprising eight high-quality infrared cameras (Pro Reflex Unit – Qualisys Inc., Gothenburg, Sweden). The cameras tracked the light reflected by 55 passive markers placed on the participant

’s skin on specific bone landmarks, following a modified version of the Davis protocol [

27]. Participants were instructed to walk in a straight line at their usual comfortable pace. For each individual we collected data from two acquisitions including a complete gait cycle for both the left and right foot (i.e., four gait cycles) [

28]. Gait data were collected by the Qualisys Track Manager software (QTM), which accurately determined the three-dimensional position of each bone marker. Then, Visual 3D software was used to preprocess the data and extract the joints’ excursion angles. Specifically, the hip, knee, and ankle three-dimensional time series from both right and left lower limbs were imported in MATLAB (MathWorks, version R2023b), where we computed their first derivative, to obtain the velocity time series of each joint. Velocity of joints

’ excursion was considered as representative of movement control [

29].

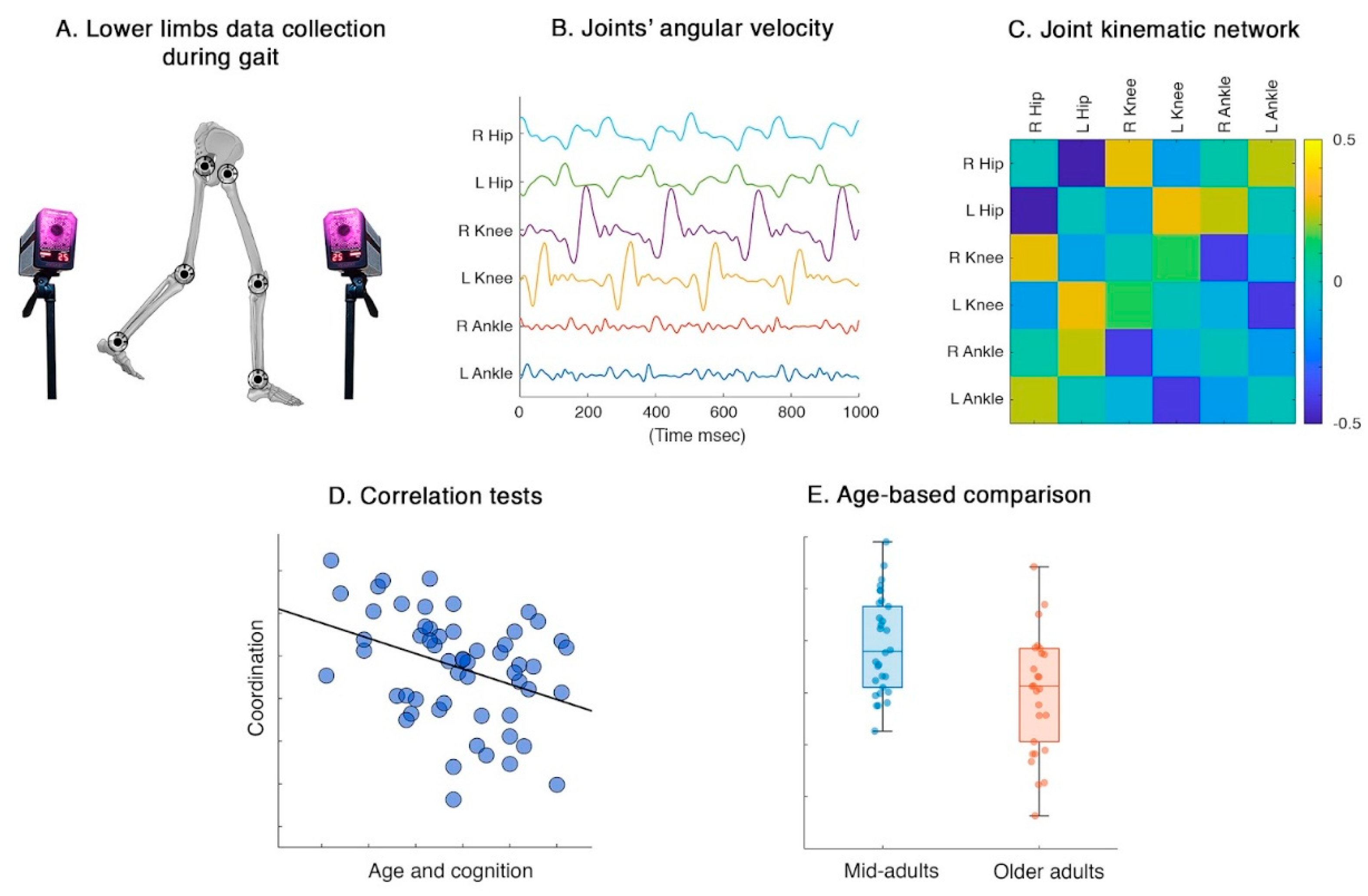

Figure 1.

Analysis pipeline. A) Gait from was recorded using a stereophotogrammetric system. B) Data on joints’ angular velocity was collected and analyzed. C) Coordination was estimated via network theory; pairwise Pearson correlation coefficient was computed among joints’ angular velocity time-series. D) Correlation tests were performed between global/joint-specific coordination features and demographic/cognitive characteristics. E) Coordination during gait was compared between mid-adults and older adults.

Figure 1.

Analysis pipeline. A) Gait from was recorded using a stereophotogrammetric system. B) Data on joints’ angular velocity was collected and analyzed. C) Coordination was estimated via network theory; pairwise Pearson correlation coefficient was computed among joints’ angular velocity time-series. D) Correlation tests were performed between global/joint-specific coordination features and demographic/cognitive characteristics. E) Coordination during gait was compared between mid-adults and older adults.

2.3. Lower Limbs Network

Using network theory, we built kinematic coordination matrices named kinectomes, whose nodes were represented by hips, knees, and ankles. The coordination between pairs of joints was expressed by the edges linking the nodes and was estimated as Pearson’s correlation coefficients between pairs of time series. We performed this computation for each axis separately, resulting in three kinectome per gait cycle for each participant. Our analysis mainly focused on joint excursions in the sagittal plane, as flexion-extension patterns represent the dominant movements during the gait cycle. Afterwards, kinectomes of different gait cycles of the same participant were averaged within the same plane. From kinectomes were extracted two different parameters: 1) the mean coordination, computed as the average value of a kinectome; 2) the nodal strength of each joint, computed as the sum of all edges belonging to a given node. While the first parameter is a global one, describing the whole lower limb joint coordination with a single score, the nodal strength is a joint-specific parameter able to represent the degree of synchronization of a single joint with respect to the whole system (i.e., lower limbs). Thereafter, we carried out correlation tests between these parameters and both demographic and neuropsychological variables. We also divided our sample around the 60-year threshold, creating a mid-adults (MA) and an older adults (OA) group, in order to test for potential age-related differences in coordination.

2.4. Statistics

Correlation tests were performed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient test. Comparison between groups were assessed through a permutation test by randomly shuffling group labels 10,000 times. In each permutation, the groups were randomly mixed, resulting in a distribution of differences that could occur by chance alone. A significant threshold of p < 0.05 was set and the outcomes were corrected using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) [

30] method for each analysis.

3. Results

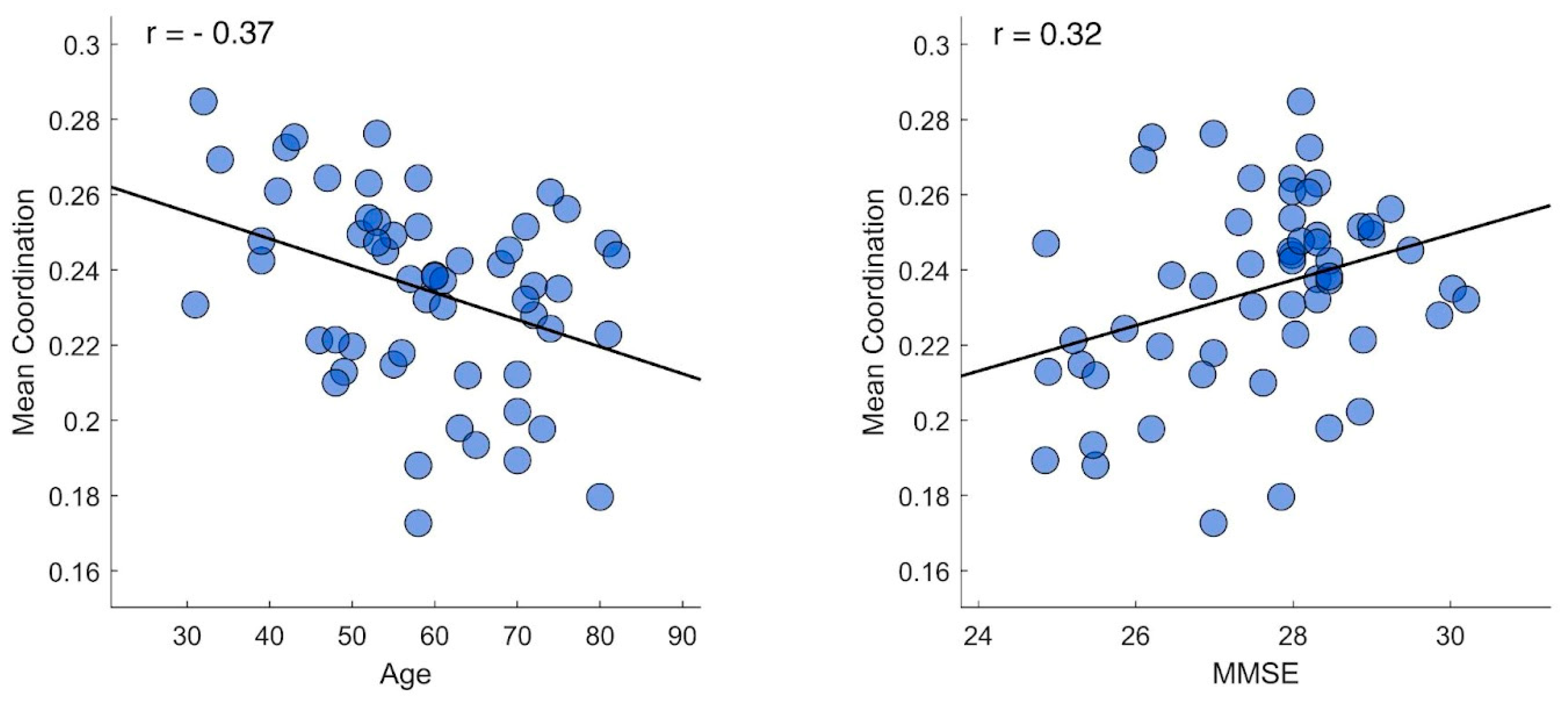

We conducted correlation tests between the average value of each participant’s kinectome (mean coordination) and both demographic and neuropsychological variables. As reported in Figure 2, we found that the mean coordination observed on the sagittal plane was significantly correlated with the participants’ age (r = -0.37 | p = 0.006 | pFDR = 0.023) and with the cognitive scores assessed with the MMSE test (r = 0.32 | p = 0.015 | pFDR = 0.03).

Figure 2.

Mean coordination correlation tests. The figure displays the correlation plot between mean lower limb coordination and both age (left panel) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores (right panel). Each dot represents an individual participant. The tests were performed using Pearson correlation coefficient with significance set at p < 0.05 after false discovery rate correction.

Figure 2.

Mean coordination correlation tests. The figure displays the correlation plot between mean lower limb coordination and both age (left panel) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores (right panel). Each dot represents an individual participant. The tests were performed using Pearson correlation coefficient with significance set at p < 0.05 after false discovery rate correction.

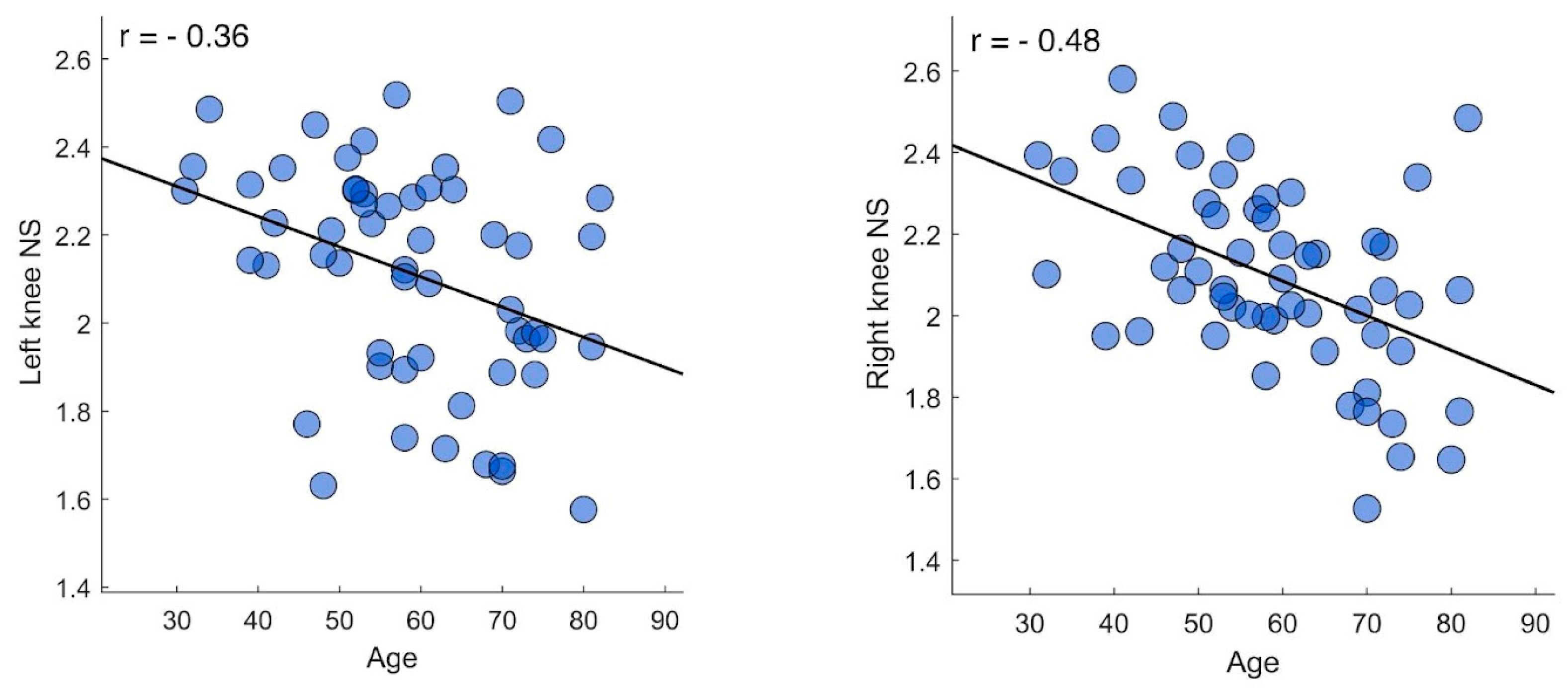

Then, we further analyzed gait coordination by repeating correlation tests focusing on individual joints. Hence, from each participant’s kinectome we extracted the nodal strength values of hips, knees, and ankles. In this case, we found significant negative correlations between the nodal strength of both knees on the sagittal plane and the participants’ age (right knee, r = - 0.48 | p < 0.001 | pFDR = 0.002) (left knee, r = - 0.36 | p = 0.007 | pFDR = 0.041), while no significant correlation was found between joints-specific coordination values and the MMSE scores. Further analysis was conducted to investigate whether the greater correlation between nodal values and knees also caused overall correlation. Excluding the kinematics of the knee, the correlation was no longer significant.

Figure 3.

Joints’ coordination correlation tests. The figure displays the correlation plot between age and both left (left panel) and right (right panel) nodal strength values. Each dot represents an individual participant. The tests were performed using Pearson correlation coefficient with significance set at p < 0.05 after false discovery rate correction.

Figure 3.

Joints’ coordination correlation tests. The figure displays the correlation plot between age and both left (left panel) and right (right panel) nodal strength values. Each dot represents an individual participant. The tests were performed using Pearson correlation coefficient with significance set at p < 0.05 after false discovery rate correction.

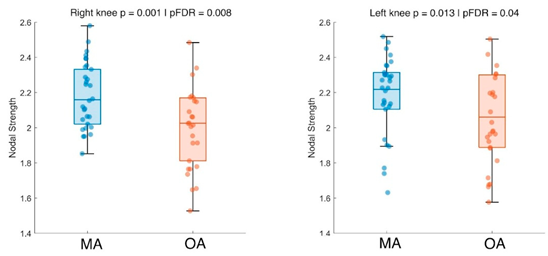

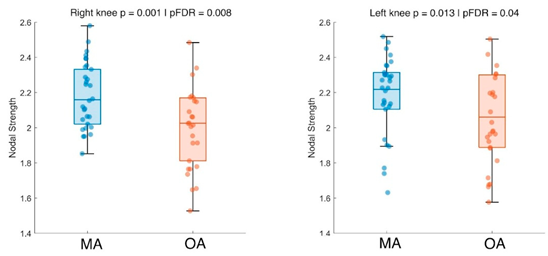

Finally, we compared coordination values between younger and older participants. The analysis showed that younger adults displayed higher coordination values on the sagittal plane for both the right (p = 0.001 | pFDR = 0.008) and left knee (p = 0.013 | pFDR = 0.04) (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

To assess the relationship between motor coordination during walking and factors such as age and cognitive abilities, we collected and analyzed data from fifty-six healthy individuals. After measuring their gait coordination using network theory applied to joint kinematics, we partly confirmed our hypotheses. In summary, our data showed that gait coordination is related to both age and cognition, but when inspecting specific joints, only knees displayed significant correlations. Furthermore, significant results were found exclusively on the sagittal plane emphasizing the significance of considering biomechanic dynamics in this specific direction. Our investigation offers a representation of the intricate interdependencies between age, cognitive function, and limb coordination during walking [

31]. The use of network theory for kinematic analysis made it possible to examine movement by revealing higher-order information compared to the analysis of individual body segments, taking into account the influence of different body parts on one another. Initially, we observed a correlation between age and global coordination during gait. However, a more detailed analysis revealed that the contribution of the knees to coordination is predominant and essential in determining this correlation. In fact, when this contribution is excluded, the global coordination no longer shows any significant association. Consistently, when we divided the sample into mid-adults and older adults, the level of knee coordination was found to be significantly different between the two groups, with a higher degree of coordination in young adults. These findings highlight the key role of the knees in gait coordination. Indeed, the negative correlation suggests that, with advancing age, there is a reduction in the overall contribution of the knees to the execution of the gait cycle. This may be due to several factors, including decreased strength and joint range of motion, which could alter the motor coordination pattern with aging [

32]. While age-related reductions in joint range of motion are well-documented, what this study adds to existing knowledge is the concurrent alteration in coordination patterns [

33,

34,

35]. Altogether, these insights suggest that training, rehabilitation, or functional recovery protocols should focus not only on improving joint range of motion, but also on enhancing the movement synergy between different lower limb joints, with particular attention to the knees. The decrease in knee joint synchronization with aging highlights a pertinent concern regarding impaired mobility, susceptibility to falls and a loss of independence in the elderly demographic cohort [

36].

Hence, the aging population’s increasing need for gait monitoring in daily life is emphasized to preserve older individuals’ mobility [

37]. In addition, it should be noted that previous studies also found that age affects hip and ankle coordination more than coordination across the knees [

38]. However, the parameters used to measure coordination vary across studies, and this may explain the differences, while at the same time offering different perspectives on the topic that could be integrated for a more comprehensive understanding. Furthermore, when analyzing the relationship between cognitive abilities, measured by MMSE test, and lower limb coordination, we found that the correlation was not directly influenced by specific joints, but was related to the overall average coordination. This suggests that the effects of ageing on cognition may indirectly impact the ability to properly coordinate lower limbs during gait [

39]. In fact, literature confirmed indirect effects of aging such as increased muscle co-activation leads to fatigue and loss of coordination [

40]. However, as a direct effect remains neuromuscular decline reduces muscle strength and joint range of motion [

41]. This is in agreement with previous research which affirmed that lower cognitive conditions are related to poorer performance in gait measurements such as speed, rhythm, or stride time and to a great variability [

42,

43]. Moreover, the relationship between lower limb function and cognitive abilities has already been explored, indicating that lower limb coordination and gait performance can serve as predictors of cognitive disorders in the elderly [

44,

45]. Kim and Ko compared the lower limb aspects such as walking speed and balance with cognitive functions and found an effective correlation. Savica examined specific gait parameters as predictors of cognitive decline and reported that spatial, temporal, and spatiotemporal measures of gait were associated with and predictive of both global and domain-specific cognitive decline. Our findings confirmed and extended the scope of application using specific joint kinematics as a possible predictor factor. These insights underscore the importance of adopting a multidimensional approach to intervention strategies aimed at preserving and enhancing lower limb coordination in older adults. However, this study have some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, since MMSE is a basically cognitive test, it doesn’t capture the full complexity of executive functions. Future research should consider correlating motor measures with specific neuropsychological tests that assess the various dimensions of executive functioning in a more detailed manner. Second, the definition of the elderly population has evolved, with the threshold for classification often shifting towards 65 years of age and beyond. In the context of future studies, it would be advantageous to investigate these motor-cognitive relationships across diverse age groups within the older adult population (i.e., young-old, old, senior, and oldest-old individuals over 90 years of age), given the heterogeneity of the aging process, which may result in the emergence of distinct patterns across subgroups.

5. Conclusions

The results of this research provide insights into the relationship between cognitive abilities, aging, and coordination of the lower limbs during walking. Our findings indicate an association between age and lower limb coordination, particularly evident in the knees. This suggests that as individuals age, there is a potential decrease in the synchronization of knee movements during walking. Furthermore, cognitive status shows a connection with limb coordination, though this association appears to be not joint-specific but related to an overall coordination pattern of the lower limbs. Further studies should focus on the underlying mechanisms of age-related alterations in motor function and cognitive-motor interactions. Indeed, gaining a deeper understanding of these processes, it can be possible to develop targeted interventions to optimize functional mobility and enhance the quality of life for aging populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Mario De Luca and Emahnuel Troisi Lopez; Data curation, Roberta Minino; Formal analysis, Mario De Luca; Funding acquisition, Giuseppe Sorrentino; Investigation, Mario De Luca and Emahnuel Troisi Lopez; Methodology, Emahnuel Troisi Lopez; Project administration, Giuseppe Sorrentino; Software, Pierpaolo Sorrentino; Supervision, Laura Mandolesi and Giuseppe Sorrentino; Writing – original draft, Mario De Luca; Writing – review & editing, Mario De Luca, Roberta Minino, Arianna Polverino, Enrica Gallo and Emahnuel Troisi Lopez.

All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor.

Funding

This research was funded by European Union “NextGenerationEU”, (Investimento 3.1.M4. C2), EBRAINS-Italy of PNRR, grant number IR0000011 and Governo Italiano Ministero per lo sviluppo Economico, ACCORDI PER INNOVAZIONE. Approccio User-friendly integrato per Diagnosi, Assistenza e Cura Efficaci—AUDACE grant number B69J23006050007.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Psychological Research of the Department of Humanities of the University of Naples Federico II (protocol code 26/2020 approved on 10/9/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCI |

Principal Component Analysis |

| MMSE |

Mini-Mental State Examination |

| FAB |

Front Assessment Battery |

| BDI |

Back Depression Inventory |

| MA |

Mid-Adults |

| OA |

Older Adults |

| FDR |

False Discovery Rate |

References

- A. Middleton, S. L. Fritz, e M. Lusardi, «Walking Speed: The Functional Vital Sign». J. Aging Phys. Act. 2015, 23, 314–322. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Troisi Lopez et al., «Kinematic network of joint motion provides insight on gait coordination: An observational study on Parkinson’s disease». Heliyon 2024, 10, 15. [CrossRef]

- E. Troisi Lopez et al., «A synthetic kinematic index of trunk displacement conveying the overall motor condition in Parkinson’s disease». 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Osoba, A. K. Rao, S. K. Agrawal, e A. K. Lalwani, «Balance and gait in the elderly: A contemporary review». Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2019, 4, 143–153. [CrossRef]

- B. Klimova e R. Dostalova, «The Impact of Physical Activities on Cognitive Performance among Healthy Older Individuals». Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 377. [CrossRef]

- G. Yogev-Seligmann, J. M. Hausdorff, e N. Giladi, «The role of executive function and attention in gait». Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 329–342. [CrossRef]

- K. Kozlowska, M. Latka, e B. West, «Asymmetry of short-term control of spatio-temporal gait parameters during treadmill walking». Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Scarano, L. Tesio, V. Rota, V. Cerina, L. Catino, e C. Malloggi, «Dynamic Asymmetries Do Not Match Spatiotemporal Step Asymmetries during Split-Belt Walking». Symmetry 2021, 13, 6. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gimmon et al., «Gait Coordination Deteriorates in Independent Old-Old Adults». J. Aging Phys. Act. 2018, 26, 382–389. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Han et al., «Quantitative analysis of the bilateral coordination and gait asymmetry using inertial measurement unit-based gait analysis». PloS One 2019, 14, e0222913. [CrossRef]

- E. G. James et al., «Walking Speed Affects Gait Coordination and Variability Among Older Adults With and Without Mobility Limitations». Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1377–1382. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Swanson e B. W. Fling, «Associations between gait coordination, variability and motor cortex inhibition in young and older adults». Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 113, 163–172. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Zadik, A. Benady, S. Gutwillig, M. M. Florentine, R. E. Solymani, e M. Plotnik, «Age related changes in gait variability, asymmetry, and bilateral coordination - When does deterioration starts?». Gait Posture 2022, 96, 87–92. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, N. The Co-ordination and Regulation of Movements. Pergamon Press, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- L. Kribus-Shmiel, G. Zeilig, B. Sokolovski, e M. Plotnik, «How many strides are required for a reliable estimation of temporal gait parameters? Implementation of a new algorithm on the phase coordination index». PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192049. [CrossRef]

- Turvey, M.T. «Coordination». Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 938–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Ippersiel, S. M. Robbins, e P. C. Dixon, «Lower-limb coordination and variability during gait: The effects of age and walking surface». Gait Posture 2021, 85, 251–257. [CrossRef]

- H.-C. Yen, H.-L. Chen, M.-W. Liu, H.-C. Liu, e T.-W. Lu, «Age effects on the inter-joint coordination during obstacle-crossing». J. Biomech. 2009, 42, 2501–2506. [CrossRef]

- A. Romano et al., «The effect of dopaminergic treatment on whole body kinematics explored through network theory». Sci. Rep. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Troisi, Lopez; et al. , «The kinectome: A comprehensive kinematic map of human motion in health and disease», Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2022, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Lopez et al., «Artificial Intelligence for automatic movement recognition: a network-based approach», 3 marzo 2025. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- R. Minino et al., «“The influence of auditory stimulation on whole body variability in healthy older adults during gait”», J. Biomech. 2024, 172, 112222. [CrossRef]

- A. Romano et al., «The effect of dopaminergic treatment on whole body kinematics explored through network theory», Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1913. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Folstein, S. E. Folstein, e P. R. McHugh, «“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician», J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [CrossRef]

- B. Dubois, A. Slachevsky, I. Litvan, e B. Pillon, «The FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside», Neurology 2000, 55, 1621–1626. [CrossRef]

- A. T. Beck, R. A. Steer, R. Ball, e W. Ranieri, «Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients». J. Pers. Assess. 1996, 67, 588–597. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Davis, S. Õunpuu, D. Tyburski, e J. R. Gage, «A gait analysis data collection and reduction technique». Hum. Mov. Sci. 1991, 10, 575–587. [CrossRef]

- R. Minino et al., «The effects of different frequencies of rhythmic acoustic stimulation on gait stability in healthy elderly individuals: a pilot study». Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19530. [CrossRef]

- Flanders, M. «Voluntary Movement». In Encyclopedia of Neuroscience; M. D. Binder, N. Hirokawa, e U. Windhorst, Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009; pp. 4371–4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Benjamini e Y. Hochberg, «Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing». J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [CrossRef]

- P. Sunderaraman et al., «Differential Associations Between Distinct Components of Cognitive Function and Mobility: Implications for Understanding Aging, Turning and Dual-Task Walking.». Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Hunter, H. M. Pereira, e K. G. Keenan, «The aging neuromuscular system and motor performance.». J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 121. [CrossRef]

- J. Bocksnick, Sharp-Chrunik,Brayden, e A. and Bjerkseth, «Changes in Range of Motion in Response to Acute Exercise in Older and Younger Adults: Implications for Activities of Daily Living». Act. Adapt. Aging 2016, 40, 20–34. [CrossRef]

- J. Hwang e M.-C. and Jung, «Age and sex differences in ranges of motion and motion patterns». Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2015, 21, 173–186. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Intolo, S. Milosavljevic, D. G. Baxter, A. B. Carman, P. Pal, e J. Munn, «The effect of age on lumbar range of motion: A systematic review». Man. Ther. 2009, 14, 596–604. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou et al., «The detection of age groups by dynamic gait outcomes using machine learning approaches». Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4426. [CrossRef]

- M. Mundt, W. Thomsen, F. Bamer, e B. Makert, «Determination of gait parameters in real-world environment using low-cost inertial sensors». PAMM 2018, 18, e201800014. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Hafer e K. A. Boyer, «Age related differences in segment coordination and its variability during gait». Gait Posture 2018, 62, 92–98. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. A. Vernooij, G. Rao, E. Berton, F. Retornaz, e J.-J. Temprado, «The Effect of Aging on Muscular Dynamics Underlying Movement Patterns Changes». Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 309. [CrossRef]

- H.-J. Lee, W. H. Chang, B.-O. Choi, G.-H. Ryu, e Y.-H. Kim, «Age-related differences in muscle co-activation during locomotion and their relationship with gait speed: a pilot study». BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 44. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhai et al., «Effects of age-related changes in trunk and lower limb range of motion on gait». BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 234. [CrossRef]

- O. Beauchet et al., «Poor Gait Performance and Prediction of Dementia: Results From a Meta-Analysis». J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 482–490. [CrossRef]

- K. L. Martin et al., «Cognitive Function, Gait, and Gait Variability in Older People: A Population-Based Study». J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2013, 68, 726–732. [CrossRef]

- A.-S. Kim e H.-J. Ko, «Lower Limb Function in Elderly Korean Adults Is Related to Cognitive Function». J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 5. [CrossRef]

- R. Savica et al., «Comparison of Gait Parameters for Predicting Cognitive Decline: The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging». J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 55, 559–567. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).