1. Introduction

The global production of plastics has increased to historically unparalleled levels, reflecting a sustained ascending trend driven by industrial demand and consumer use., with approximately 400 million metric tons (Mt) generated in 2022 alone, of which polypropylene (PP) accounts for nearly 19% of total output [

1]. While demand for plastic materials remains high, particularly in packaging, which represented 36.5% of total plastic consumption in 2023, the environmental burden of plastic waste is intensifying [

2]. In the same year, an estimated 267.7 Mt of plastic waste was produced globally, yet only 9% was recycled, with the remainder incinerated, landfilled, or mismanaged [

1] A massive amount of this mismanaged waste ends up in the oceans, mainly due to inadequate waste infrastructure in middle-income countries [

3]. These developments highlight the importance of implementing circular economy strategies that incorporate mechanical recycling of polyolefins into manufacturing processes, with careful consideration of maintaining their performance in technically demanding applications.

Mechanical recycling constitutes a highly viable strategy for recovering and reintegrating post-consumer plastics into the production cycle. Post-consumer recycled polypropylene, commonly recovered from packaging waste, is often a heterogeneous mixture containing varying grades of PP, stabilizers, and contaminants [

4,

5,

6]. Although attractive from a sustainability perspective, PPr is prone to degradation due to previous processing, thermal, mechanical, and UV exposure, leading to reduced molecular weight and overall properties deterioration [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Even minor chemical modifications can lead to significant alterations in physical properties, particularly when polymers are used in outdoor environments where degradation is triggered by exposure to oxygen and ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight [

14,

15]. The incorporation of recycled polypropylene into virgin polypropylene constitutes a viable strategy for mitigating the degradation of material properties commonly observed in recycled polymers. This approach seeks to restore critical performance attributes such as mechanical integrity, thermal resistance, and processing behaviour by utilizing the superior structural and compositional characteristics of the virgin polymer to counterbalance the deficiencies inherent in the recycled fraction [

4,

16]

However, there are only few studies which demonstrated that incorporating low to moderate amounts of post-consumer recycled polypropylene into virgin polypropylene can be accomplished without causing substantial degradation in the material’s mechanical and thermal performance maintaining acceptable levels of tensile strength, impact resistance, and thermal stability, making them suitable for a range of non-critical applications. The slight reduction in performance observed at low to moderate levels of post-consumer recycled polypropylene is mainly due to the capacity of the virgin polymer matrix to mitigate the effects of structural imperfections, residual impurities, and thermal or oxidative degradation accumulated during previous processing cycles [

11,

17].

Although some progress has been made in understanding the properties of post- consumer PP, there is still a lack of comprehensive information regarding the effects of blending recycled polypropylene with virgin counterpart at different concentrations on key material characteristics. Specifically, the influence of such blending on crystallization behaviour, thermal decomposition patterns, and resistance to oxidative degradation remains insufficiently studied, particularly in comparison to materials that have not been homogenised by extrusion. In addition, the potential role of the extrusion process in promoting homogenization of post-consumer PP and hence restoring to some degree the material’s performance, has not yet been fully investigated or clearly established.

This study aims to evaluate the thermal, oxidative, and mechanical properties of blends containing 25%, 50%, and 75% PP

r, in addition to fully recycled and virgin counterparts and establish if the properties of these binary mixtures may be predicted by the Law of Mixture (LOM), also known as the rule of mixtures [

18,

19]. Moreover, a non-extruded version (rPPcw), obtained in previous work [

20] is also compared to isolate the effects of homogenization. The results are expected to contribute to the development of sustainable PP-based materials for more performance demanding applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The virgin PPv (CAPILENE R 50 homopolymer supplied by Carmel Olefins) was used as a reference material and for compounding with post-consumer PP, designated thereafter as PPr, was gathered from various decentralized recycling points through the yellow bin collection system. PPr was shredded and washed in cold water. More information about the preparation of PPr may be found elsewhere [

20].

Three blends of PPv and PPr were compounded using the Thermo Scientific Process 11 twin-screw extruder (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Prior to extrusion, PPv and PPr were mechanically mixed based on their weight percentage. Their compositions may be consulted in Error! Reference source not found..

Table 1.

Composition of the PP batches.

Table 1.

Composition of the PP batches.

| Batch |

PPv (wt.%) |

PPr (wt.%) |

| PPv |

100 |

0 |

| 25%PPr |

75 |

25 |

| 50%PPr |

50 |

50 |

| 75%PPr |

25 |

75 |

| PPr |

0 |

1001

|

Compounding was performed at a screw speed of 100 rpm, with a temperature gradually increasing along the extruder barrel from 180°C at the feeding zone to 220°C at the die. A total of five batches, detailed in

Table 1, were prepared. Virgin PP was used as received in pellet form, while PPr, which was initially in the form of shredded flakes, underwent extrusion to ensure the same processing conditions as PPv and PPr blends. The extruded materials were shredded using an SM 100 Cutting Mill (RETSCH GmbH, Haan, Germany) equipped with a 4 mm mesh sieve to prepare the granulates for further testing and processing.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Melt Flow Index

The melt flow index was measured using a Göttfert MI-3 machine (GÖTTFERT Werkstoff-Prüfmaschinen GmbH, Buchen, Germany) in accordance with ISO 1133-1997 (2.16 kg, 230 °C) [

21]. For each material, five samples were tested to ensure accuracy and reliability.

2.2.2. Thermal Analysis

To determine the melting temperature (Tm), crystallisation temperature (Tc), melting enthalpy (Hm), and cold crystallisation enthalpy (Hc), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on samples weighing approximately 5.5 ± 0.5mg. The tests were conducted using a DSC Discovery 250 instrument (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) by ISO 11357-6:2018 [

22]. Data was analysed using TRIOS software (V5.7), developed by TA Instruments. To eliminate any thermal history, each material lot underwent two heating and cooling cycles, with data from the second cycle used for analysis. Three samples were tested per material lot. The DSC procedure involved stabilising each sample at 20 °C, heating it to 200 °C, and then cooling it back to 20 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. The degree of crystallinity (χ) was calculated using Equation (1) [

23]

where

Hf (J/g) represents the melting enthalpy of the polymer under analysis. The melting enthalpy of 100% crystalline PP

(H0f) is known to be 207 J/g [

24].

The oxidative resistance of the materials was evaluated according to ASTM D3895-14 [

25]. Film samples weighing approximately 7 ± 1.0 mg were placed in open aluminium crucibles, forming a uniform layer at the bottom. The samples were first heated under a nitrogen atmosphere from room temperature to 200 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min, then held isothermally for 5 minutes. After that, the nitrogen atmosphere was replaced with oxygen and maintained until the onset of the exothermic peak.

Thermal stability was assessed by thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA), performed in a Netzsch – Jupiter STA 449 F3 apparatus (NEDGEX GmbH, Selb, Germany) according to E 2550-11 [

26]. Samples weighing 10 ± 1 mg were taken from the extruded PP

r and its blends with PP

v, while the PP

v sample was obtained from pellets. The samples were heated from 30 °C to 700 °C at a constant rate of 20 K/min under a nitrogen atmosphere (50 mL/min) in alumina (Al₂O₃) crucibles, and weight loss was recorded as a function of temperature. The derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curve, representing the rate of weight change, was also used to help interpret thermal degradation events.

2.2.3. Mechanical Properties

Tensile test specimens (ISO 527-2 type 5A [

27]) were produced by injection moulding using a HAAKE MiniJet II mini-injection moulding machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The processing conditions used for virgin PP recycled PP and their blends are detailed in

Error! Reference source not found..

Table 2.

Injection moulding processing conditions.

Table 2.

Injection moulding processing conditions.

| Processing Parameter |

Value |

| Plasticization chamber temperature (°C) |

230 |

| Mold temperature (°C) |

40 |

| Injection time (s) |

3 |

| Injection pressure (bar) |

300 |

| Packing time (s) |

17 |

| Packing pressure (bar) |

240 |

Tensile tests were conducted using a Shimadzu AGS-X 10 kN machine (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD, USA) by ISO 527-1 [

28]. All tests were performed at room temperature in two stages. In the first stage, specimens were stretched at a 1 mm/min rate to determine Young’s modulus. The tensile rate was increased to 50 mm/min in the second stage and maintained until specimen failure. Data from this stage were used to calculate the yield stress (σ

y) and strain (ε

y), as well as the tensile strength (σ

b) and strain at break (ε

b). Five specimens were tested for each material batch.

3. Results and Discussion

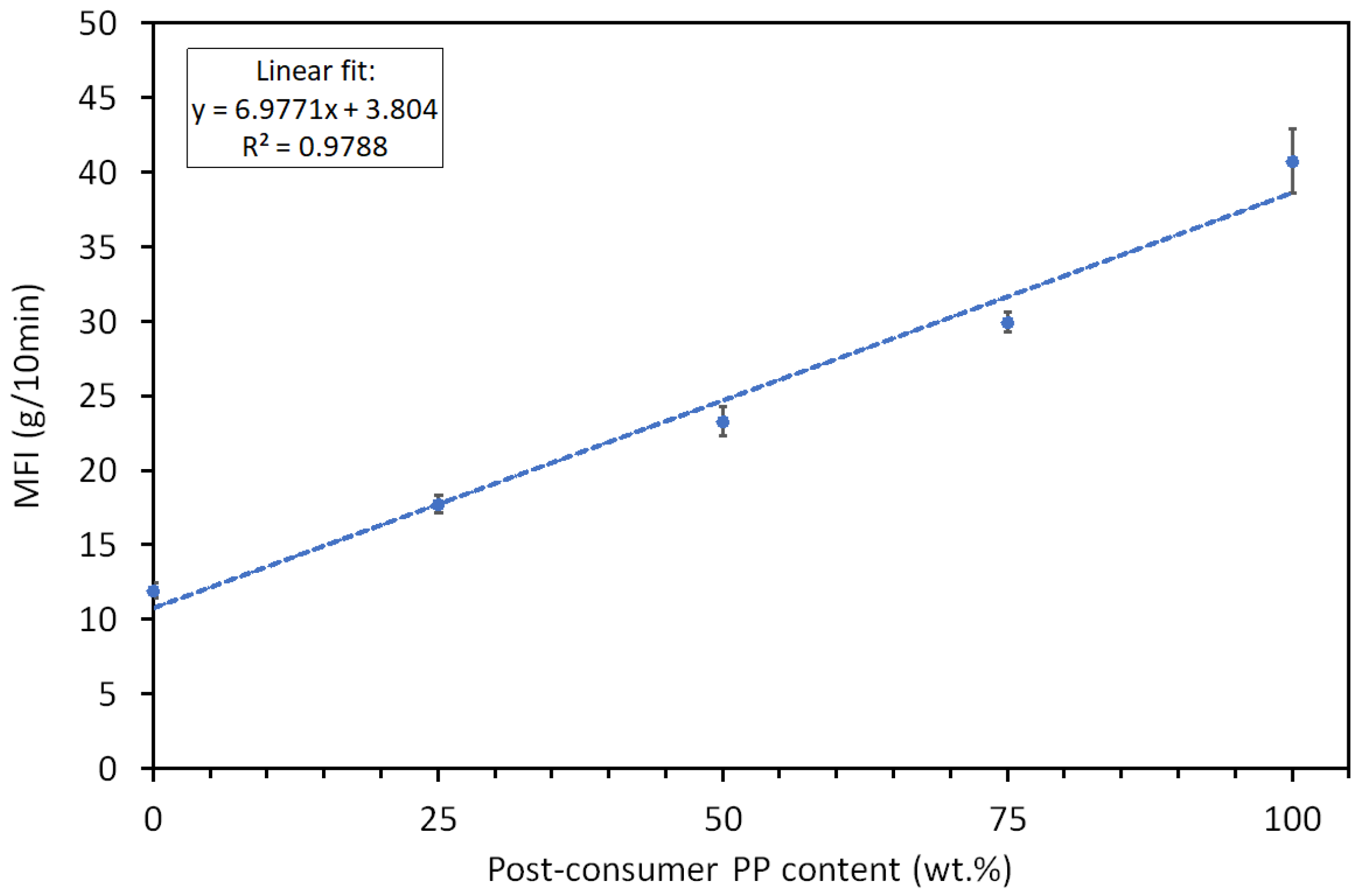

3.1. Melt Flow Index

The melt flow index measurements revealed a clear trend of increasing fluidity with the addition of post-consumer recycled polypropylene to virgin polypropylene. PP

v exhibited the lowest MFI value (11.94 ± 0.53 g/10 min), while 100% recycled PP showed the highest MFI (40.72 ± 2.16 (g/10 min)). PPv exhibited the lowest MFI value (11.94 ± 0.53 g/10 min), while 100% recycled PP showed the highest MFI (40.72 ± 2.16 (g/10 min)). No significant difference in the MFI (40.56 ± 1.49 (g/10 min)) was detected for the material (rPPcw) investigated in our earlier work [

20] when compared to PP

r. The rPPcw is identical in its composition to PP

r. The main difference is that the latter underwent additional extrusion step to ensure the homogenization of the recycled plastics mixture, while the rPPcw was moulded directly from reground recycled flakes.

Intermediate compositions, containing 25%, 50%, and 75% PPr, demonstrated a progressive increase in MFI values (17.74 ± 0.61, 23.32 ± 0.98, and 29.96 ± 0.66 (g/10 min), respectively) and hence decrease in molecular weight [

29]. Verification of the results via regression analysis (

Error! Reference source not found.), led to the conclusion that the MFI of the blends follows the Law of Mixtures (LOM) with good prediction reflected in the coefficient of determination of the fit

R2 =0.9788. The Law of Mixtures states that the properties of binary mixtures fall between those of the individual pure components and vary proportionally with their respective volume fractions (ν) [

18,

19]. In case of melt flow index, the MFI of a blend (

MFIb) should vary according to Equation 2, where subscripts

v and

r denote the virgin and recycled states, respectively.

The linear relationship between MFI and recycled content proves that the incorporation of recycled material systematically reduces the average molecular weight of the blends. However, it is important to note that the recycled material analysed represents mixed grades of polypropylene from unknown sources. Hence, direct molecular weight comparisons with their original virgin counterparts are impossible. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to assume that, at least in part, the average molecular weight reduction may be attributed to chain scission and degradation during prior use and reprocessing [

30]. Moreover, this reduction in molecular weight typically leads to a decrease in mechanical properties such as tensile strength, elongation at break, and impact resistance, which must be accounted for in material design and application [

4,

7,

8,

31,

32].

Figure 1.

MFI of PPv, PPr, and their blends at different recycled content levels.

Figure 1.

MFI of PPv, PPr, and their blends at different recycled content levels.

3.2. Thermal Characterization

3.2.1. Thermal Transitions and Crystallinity Analysis

The thermal behaviour of PPᵥ and its blends with PPr was evaluated by DSC and the respective values may be consulted from

Table 1, where: H

c (J/g) and T

c (°C) are respectively, crystallization enthalpy and temperature; H

f (J/g) and T

f (°C) are respectively fusion enthalpy and temperature; and χ (%) is the crystallinity degree. In

1.(±) represents the standard deviation

2. data from the study by Prior et al. [

20] are included for comparison purposes

3. data was not available

Table 2, it is shown how the thermal properties of the blends and PP

r vary as compared to PP

v.

Table 1.

Thermal properties of PPv, PPr, and their blends, determined by DSC.

Table 1.

Thermal properties of PPv, PPr, and their blends, determined by DSC.

| Material composition |

Hc (J/g) |

Tc (°C) |

Hf (J/g) |

Tf (°C) |

χ (%) |

| PPv

|

102.16 1.(±) 1.89 |

112.25 (±) 0.37 |

101.59 (±) 2 .06 |

163.61 (±) 0.12 |

49.08 |

| 25%PPr |

99.60 (±) 0.36 |

123.68 (±) 0.39 |

103.60 (±) 0.75 |

164.44 (±) 0.19 |

50.05 |

| 50%PPr |

94.23 (±) 1.61 |

124.41 (±) 0.10 |

97.37 (±) 3.50 |

163.75 (±) 0.07 |

47.04 |

| 75%PPr |

92.04 (±) 0.73 |

124.30 (±) 0.12 |

95.40 (±) 0.71 |

163.30 (±) 0.07 |

46.09 |

| PPr

|

86.82 (±) 0.58 |

124.19 (±) 0.02 |

92.04 (±) 1.37 |

162.63 (±) 0.09 |

44.46 |

|

2.rPPcw |

3.- |

122.23 (±) 0.16 |

99.05 (±) 0.54 |

162.32 (±) 0.21 |

48.00 |

Table 2.

Variation of thermal properties (%) of PP blends and PPr relative to virgin PP.

Table 2.

Variation of thermal properties (%) of PP blends and PPr relative to virgin PP.

| Material composition |

1.∆Hc (%) |

∆Tc (%) |

∆Hf (%) |

∆Tf (%) |

| 25%PPr

|

2.↓2,51 |

3.↑10.18 |

↑1.98 |

↑0.51 |

| 50%PPr

|

↓7.76 |

↑10,83 |

↓4.15 |

↑0.09 |

| 75%PPr

|

↓9,91 |

↑10.73 |

↓6.09 |

↓0.19 |

| PPr

|

↓15.02 |

↑10,64 |

↓9. 40 |

↓0,60 |

The fusion enthalpy decreased slightly with increasing PP

r content, from 101.59±2.06(J/g) for PPᵥ to 92.04±1.37 (J/g) for 100% PP

r, accompanied by a minor reduction in the degree of crystallinity (from 49.08% to 44.46%). However, the fusion temperature remained relatively stable across all compositions, ranging from 163.61±0.12°C (PPᵥ) to 162.63±0.09°C (PP

r), indicating that the crystalline structure of polypropylene does not undergo significant alteration. It should be noted, however, that the blend containing 25% recycled polypropylene (25%PP

r) exhibited slightly higher melting temperature, melting enthalpy, and hence, degree of crystallinity compared to the PP

v (

Table 1 and

1.(±) represents the standard deviation

2. data from the study by Prior et al. [

20] are included for comparison purposes

3. data was not available

Table 2). This behaviour can be attributed to residual crystalline fragments and particulate contamination within the recycled material, which may act as heterogeneous nucleating agents as blended at relatively low proportion (25%) with virgin PP [

33]. Such nucleating sites facilitate the crystallization process by promoting faster and more efficient organization of polymer chains during cooling. Furthermore, slight chain scission occurring during the recycling process may enhance molecular mobility, thereby favouring crystallization at low content of the recycled PP [

34]. These combined effects result in an initial increase in crystallinity at low PP

r content before the negative impact of accumulated degradation becomes more pronounced at higher PP

r percentages.

During the cooling cycle, the recrystallization enthalpy (H

c) decreased with higher PP

r content. Notably, the recrystallization temperature (T

c) of the blends increased approximately 10%, from 112.3°C for PPᵥ to 124.2°C for PPᵣ. This shift suggests that the recycled material promotes earlier nucleation during cooling, likely due to the presence of heterogeneous nucleation sites generated during prior processing cycles [

35]. Overall, the incorporation of recycled post-consumer polypropylene into virgin material does not significantly affects the thermal transitions and crystallinity. Moreover, the blend with 25% of the post-consumer PP showed a slight increase in crystallinity indicating a possible improvement of the mechanical properties which will become evident after their assessment.

The comparison between the thermal properties of extruded recycled polypropylene (PP

r) and its non-extruded counterpart (rPPcw) [

20], highlights the influence of prior homogenization on crystallization behaviour. While both materials show similar melting temperatures, rPPcw exhibits a higher melting enthalpy (99.05 ± 0.54 (J/g)) and crystallinity (48.00%) compared to PPr (92.04 ± 1.37 (J/g); 44.46%). This increase in crystallinity may be attributed to residual ordered structures or crystal fragments preserved in the rPPcw due to the absence of additional thermal and shear processing steps during extrusion [

33,

35] The crystallization temperature (T

c) of rPPcw is slightly lower (122.23 °C) than that of PP

r (124.19 °C), suggesting that although the crystallinity is higher, nucleation may have occurred later or more gradually. This behaviour may result from less uniform chain distribution or incomplete homogenization of rPPcw, as the material was directly processed from reground flakes. These findings suggest that the homogenization by extrusion process can disrupt some of the existing crystalline domains, reducing overall crystallinity and sequentially stiffness of the recycled PP but improving its ductility, as it was verified by mechanical testing further discussed ahead.

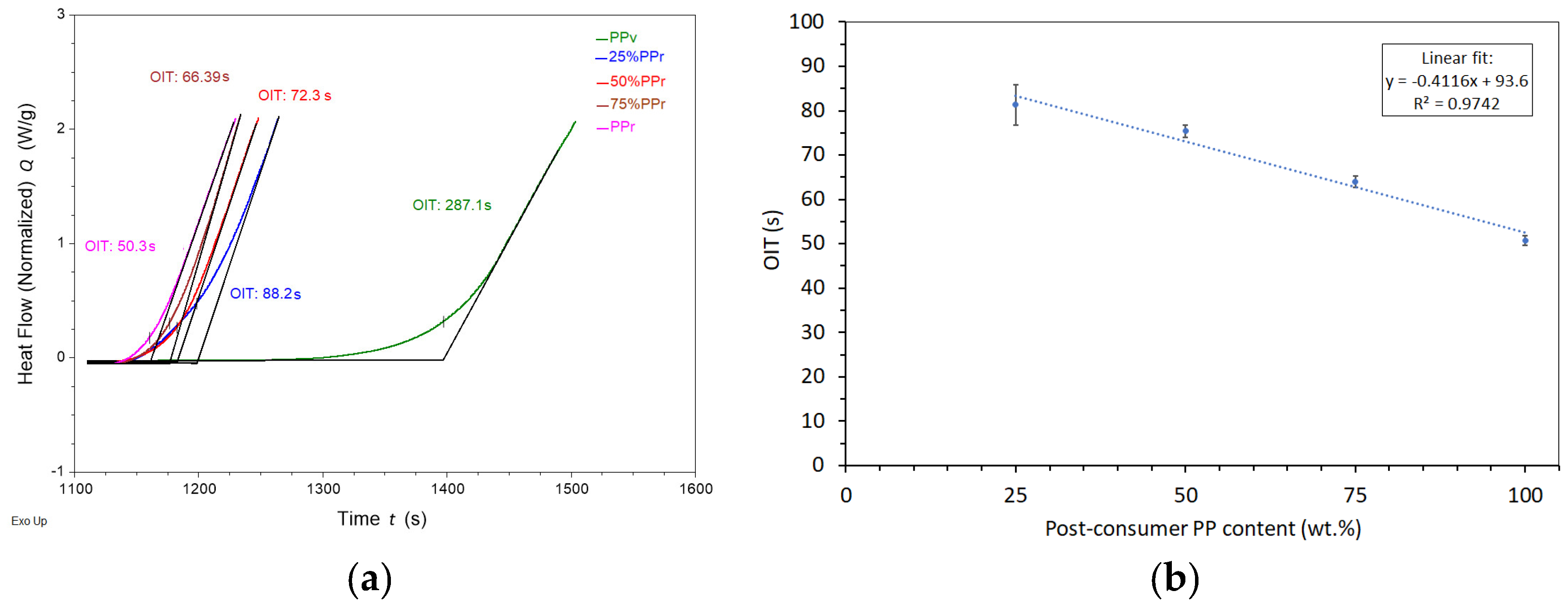

3.2.2. Oxidation Induction Time

Polypropylene is prone to oxidative degradation due to tertiary carbon atoms in its backbone, which are easily attacked by free radicals, especially under heat or UV exposure. This leads to chain scission, resulting in embrittlement and loss of mechanical properties [

36,

37]. Therefore, OIT analysis is essential for understanding how blending with virgin PP can attenuate oxidative degradation.

As shown in

Table 3 and exemplified in

Figure 1(a), virgin polypropylene’s oxidation induction time was 277.6 ± 55.3 s while adding just 25% PP

r led to a sharp decrease to 81.3 ± 6.9 s, representing a reduction of approximately 71%. Further increases in PP

r content continued to reduce the OIT, with values of 75, 4 ± 7.4 s, 64, 0 ± 6. 9 s and 50. ± 8.3 s for 50%, 75%, and 100% PP

r, respectively. These results indicate that recycled polypropylene contains a significantly lower amount of antioxidant stabilizers, which are typically consumed during the material’s prior thermal and mechanical processing cycles. The loss of antioxidants and the existence of oxidative breakdown products like peroxides and carbonyl compounds lower the material’s resistance to further oxidation attack [

20,

33]. Furthermore, recycled PP may contain residual catalysts and metal contaminants, which can act as pro-oxidants, enhancing the degradation rate. Such impurities exacerbate thermo-oxidative degradation of PP, leading to a compromised material performance [

38].

The slight improvement in oxidation induction time (OIT) from 41.6 ± 5.5 s [

20] in non-extruded recycled polypropylene (rPPcw) to 50.8 ± 8.3 s in extruded PP

r can be attributed to the homogenization effect of the extrusion process. Extrusion promotes a more uniform distribution of oxidative degradation products and residual antioxidants, reducing localized concentrations of reactive species that would otherwise accelerate degradation. Additionally, thermal and shear conditions during extrusion may partially remove volatile oxidative byproducts and facilitate structural reorganization, slightly enhancing oxidative resistance even without added stabilizers [

39].

Besides the sharp reduction in oxidation induction time (OIT) observed with the incorporation of 25% post-consumer recycled polypropylene (PP

r), the relationship between OIT and recycled content remains linear across the 25% to 100% range (

Figure 1(b)) in line with the Law of Mixtures, highlighting the strong negative correlation between increasing PP

r content and decreasing OIT at this range .

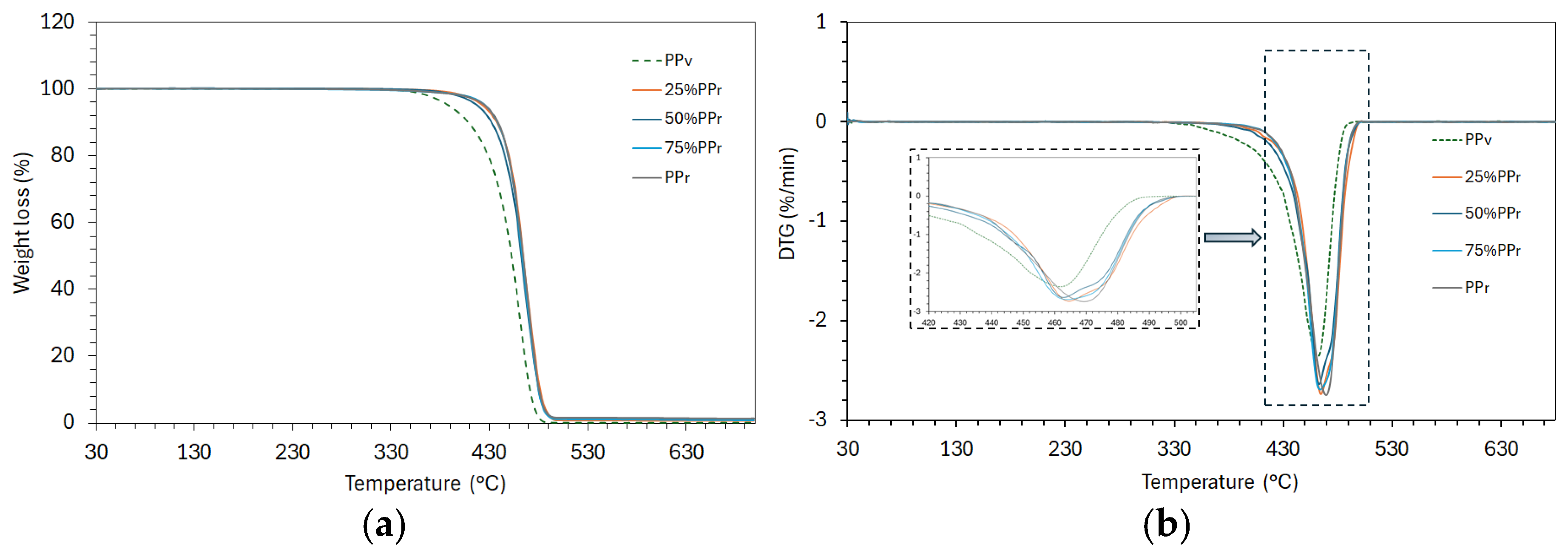

3.2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis

As demonstrated in

Figure 2 and

Table 4 the initial degradation temperature (T

on) of the virgin polypropylene is 325.5 °C, whereas all samples containing recycled PP exhibit a substantially higher T

on around 344°C (for 25%, 50%, 75% PP

r blends and 100% PP

r). It constitutes about a 19°C increase in onset temperature with any recycled content, indicating improved thermal stability in the blends and recycled material compared to virgin PP. The trend seems somewhat counterintuitive since polymer chain scission from prior processing typically reduces thermal stability, as it was reported that recycled PP often degrades at lower temperatures due to pre-existing oxidative damage and radical formation [

40,

41]. Moreover, the PP

r blends apart from 25%PP

r have lower crystallinity than PP

v. In general, higher crystallinity in polymers correlates with greater thermal stability, because tightly packed crystalline regions resist thermal motion and oxidative attack [

24]. Nevertheless, a similar trend has been reported by Stoian et al., who reported higher degradation onset in recycled PP and its blends with virgin PP compared to the latter [

42]. Recycled PP often contains residual antioxidants and stabilizers that delay the onset of thermal degradation. These additives scavenge free radicals and inhibit oxidative chain scission, thereby protecting the polymer during heating [

43]. The recycled fraction imparts enhanced stability to the blends: even at 25% PP

r content elevating T

on to the same level as 100% recycled PP, suggesting the presence of stabilizers or altered polymer segments in the recycled material dominates the initial decomposition behaviour of the blend, outweighing the crystallinity loss (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

The peak degradation temperature (T

p) corresponds to the temperature of the fastest mass loss (the DTG peak), as shown in detail in the inset of

Figure 2(b). All samples show a single prominent degradation peak, with T

p values clustered in the mid 460°C range. Virgin PP has T

p 463.3°C, and T

p of the 25–75% PP

r blends are very similar (within ±1°C, around 462–465°C). It indicates that the primary decomposition event occurs at essentially the same temperature for virgin and recycled blends, implying that the fundamental degradation mechanism is unchanged and typical for polypropylene, known to undergo a one-step, random-chain scission thermal decomposition [

34], indicating the single-step degradation for all formulations (virgin, recycled, and blends). The presence of recycled content up to 75% did not significantly alter the kinetics of this degradation step. The fully recycled PP shows a slightly higher T

p (469.3°C), about 6°C above the virgin/blend values, indicating higher thermal stability, however, coming at the cost of other properties, e.g., molecular weight reduction, as it was earlier discussed (

Error! Reference source not found.).

This slight shift to a higher peak temperature for the recycled sample implies that once degradation starts, minor cross-linking/branching from its past lifecycle or trace contaminants in the recycled stream, which decomposes at higher temperatures, may influence the peak position [

44]. Moreover, recycled PP may retain residual stabilizers such as phenolic antioxidants from previous processing cycles, which can delay thermal decomposition and increase T

p under inert conditions [

39].

However, it became clear from evaluation of the oxidation induction time (

Table 3) that PPr and its blends with PPv have experienced significant oxidative degradation during prior use and recycling, which may be attributed to chain scission and the formation of oxidation-prone functional groups, such as carbonyls [

38]. These structural modifications reduce the oxidative stability of the material, resulting in shorter OIT values when exposed to oxygen-rich environments. Therefore, while recycled PP may resist thermal decomposition at higher temperatures under inert conditions, its chemical structure makes it more vulnerable to oxidative attack [

39].[

45,

46].

ΔT=Te - Tp is a temperature interval over which the bulk of degradation occurs. In virgin PP, Te (end degradation temperature) is about 497.6°C, whereas in the blends and recycled PP, it slightly increases to roughly 501–502°C. The degradation interval ΔT for PPv spans a broader range (172.1°C). When recycled polypropylene is introduced, this degradation window narrows significantly. The 25%–75% PPr blends have a ΔT around 156–158°C, and the 100% recycled PP shows a ΔT of 156.6°C, allowing to conclude that the blends degrade over a lower temperature range, compared to virgin PP, reflecting a more uniform and quicker breakdown.

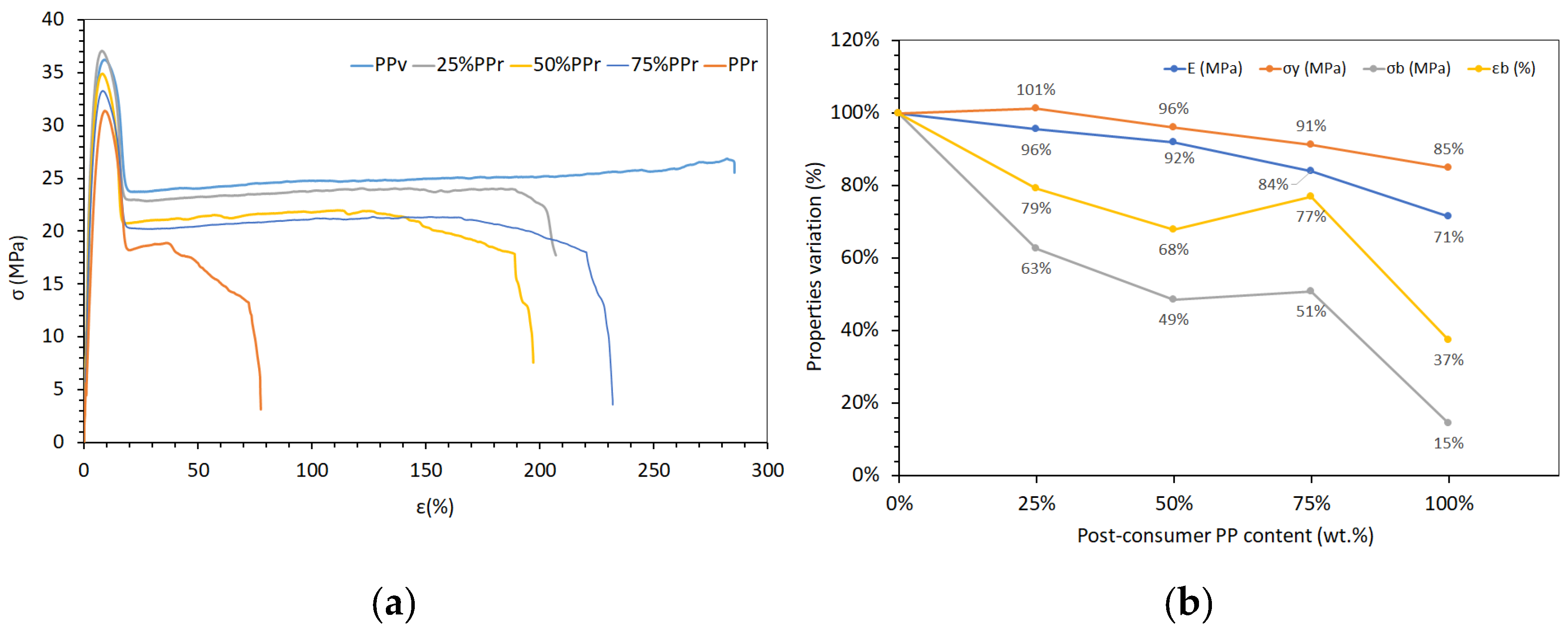

3.3. Mechanical Characterization

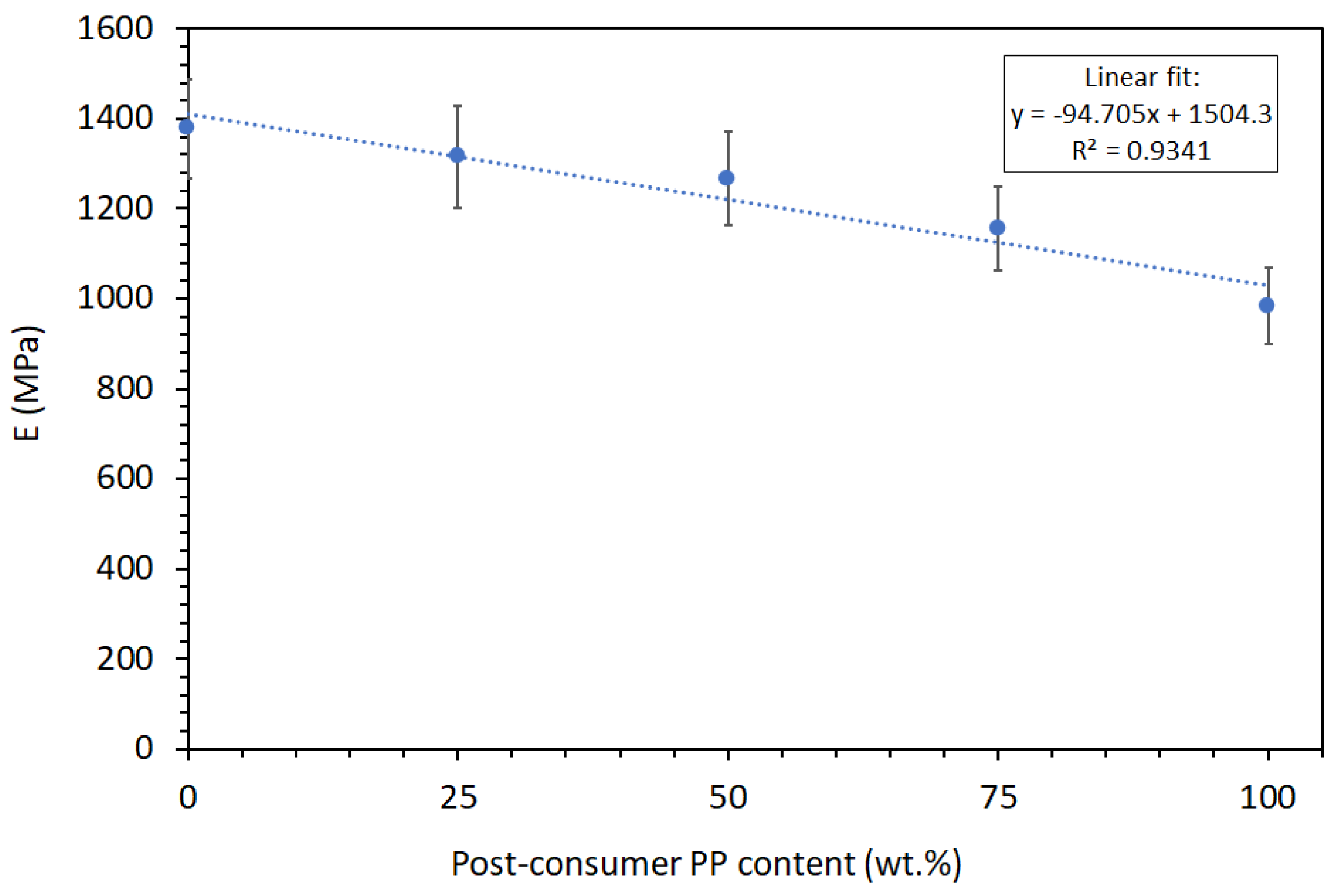

The tensile test results for virgin polypropylene (PP

v), its blends with post-consumer recycled polypropylene (PP

r), and unprocessed recycled PP (rPPcw) provide insights into how increasing recycled content affects mechanical properties (

Table 5 and

Figure 3). To enable a comparison between the different mechanical properties, all values were normalized relative to PP

v (

Figure 3(b)). There is a clear decreasing trend in elastic modulus (E) with increasing PP

r content. PP

v exhibits the highest modulus at approximately 1378 MPa, while 100% PP

r shows a reduced modulus of about 984 MPa. This 29% decline is due to the degradation of polymer chains during recycling, leading to lower molecular weight and reduced stiffness [

35]. As shown in

Error! Reference source not found., the elastic modulus follows the Law of Mixtures, allowing for accurate prediction of how PP

v/PP

r will perform in the elastic deformation region.

The yield strength (σ

y) remains relatively stable across the blends, with a maximum of 15% reduction from 36.67 MPa in PP

v to 31.08 MPa in PP

r. It indicates that the initial resistance to plastic deformation is not significantly compromised by the addition of recycled content, possibly due to the retention of crystalline regions that contribute to yield behaviour [

39] These findings corroborate the gradual decrease in elastic modulus and yield strength reported by Hincza et al. [

17] in virgin and recycled PP blends, not specifying, however, the origin of recycled PP. Curtzwiler et al. [

11] reported an opposite trend, showing a linear increase in yield strength and strain with increasing content of post-consumer polyolefin recyclates. These contradictory findings, however, may be explained by the composition of the recycled post-consumer material used by these authors, which consisted mainly of polyethylene with a low proportion of polypropylene.

Ultimate tensile strength (σ

b) and elongation at break (ε

b) show a marked decrease with higher PP

r content. PP

v has an ultimate tensile strength of 22.80 MPa and elongation at break of 293.86%, whereas PPr drops to 3.30 MPa and 109.79%, respectively. It should be noted that the material’s behaviour in the plastic deformation zone leads to high variability in the ultimate tensile strength values and elongation at break. As a result, it is impossible to establish a clear trend in their variation between 25% and 75% recycled content. The reduction in these properties indicates embrittlement, likely caused by chain scission and referred earlier oxidative degradation during recycling, which reduces the material’s ability to undergo plastic deformation before failure [

46].

Unprocessed by extrusion rPPcw (

Table 5) from these authors previous work [

20] exhibits an elastic modulus comparable to PP

v (1379.72 MPa) and a higher ultimate tensile strength (23.32 MPa) but significantly lower elongation at break (18.75%). This behaviour suggests that while stiffness and strength may be retained, the lack of homogenization through extrusion leads to poor ductility, possibly due to contaminants and inhomogeneities acting as stress concentrators [

33]. Overall, the incorporation of recycled polypropylene affects the mechanical properties of the blends, with higher recycled content leading to reduced stiffness, strength, and ductility. However, at lower concentrations (25%PP

r), the impact on mechanical properties is less pronounced, and even slightly improved as it is the case of yield strength indicating the potential for using recycled content without significantly compromising material performance.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential to tailor the physical properties of virgin polypropylene by incorporating post-consumer recycled polypropylene sourced from decentralised recycling systems. Melt blending significantly influences the material’s thermal, oxidative, and mechanical performance. Increasing PPr content enhanced melt flow and thermal stability under inert conditions but substantially reduced oxidation resistance and ductility due to stabilisers’ depletion and degradation products. Notably, a 25% PPr blend exhibited a favourable balance of properties, including slightly improved crystallinity and yield strength and increased thermal degradation resistance under a nitrogen atmosphere. A clear decline in Oxidation Induction Time was observed with increasing PPr content. In the sample composed entirely of recycled material, the OIT dropped about 82% in comparison to virgin PP, indicating a substantial loss of oxidative stability. This result points to the necessity of reintroducing stabilisers when using high proportions of recycled polypropylene. Homogenisation by extrusion improved the oxidative stability of PPr by 22% and increased ductility compared to the non-extruded counterpart (rPPcw), underlining its role in improving blend consistency and performance. Furthermore, the properties such as MFI, elastic modulus, and partially OIT followed the Law of Mixtures, making them predictable across blend compositions. This predictability supports the feasibility of engineering recycled PPv/PPr blends for non-critical structural applications. Future research should focus on long-term mechanical and oxidative aging to ensure durability and reliability in service environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. T.Z. and M.S.A.O.; data curation. T.Z.; formal analysis. T.Z. and M.S.A.O.; funding acquisition. T.Z. and M.S.A.O.; investigation. T.Z., and M.S.A.O.; methodology. T.Z., and M.S.A.O.; project administration. T.Z. and M.S.A.O.; resources. T.Z. and. M.S.A.O.; supervision. M.S.A.O.; validation. T.Z. and M.S.A.O.; writing—original draft. T.Z.; writing—review and editing. T.Z. and M.S.A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: The present study was supported by the project UID 00481 Centre for Mechanical Technology and Automation (TEMA)

Acknowledgments

T. Zhiltsova is grateful to the Portuguese national funds (OE). through FCT. I.P.. in the scope of the framework contract foreseen in the numbers 4. 5. and 6 of Article 23. of the Decree-Law 57/2016. of August 29. changed by Law 57/2017. of July 19.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DSC |

Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| LOM |

Law of Mixtures |

| MFI |

Melt Flow Index |

| OIT |

Oxidation Induction Time |

| PPr

|

Post-consumer recycled polypropylene |

| PPv

|

Virgin polypropylene |

| rPPcw |

Non-homogenized recycled PP |

| TGA |

Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| Te

|

End degradation temperature |

| Ton

|

Onset degradation temperature |

| Tp

|

Peak degradation temperature |

| σb

|

Ultimate tensile strength |

| σy

|

Yield strength |

| εb

|

Elongation at break |

| χ |

Crystallinity degree |

References

- K. Houssini, J. Li, and Q. Tan, “Complexities of the global plastics supply chain revealed in a trade-linked material flow analysis,” Commun Earth Environ, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 257, 2025. [CrossRef]

- “Circularise, ‘Global plastic consumption, production, and sustainability efforts’ ,” Circularise Blog. Accessed: May 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.circularise.com/blogs/global-plastic-consumption-production-and-sustainability-efforts.

- Ritchie H. and Roser M., “‘Plastic Pollution,’ Our World in Data.” Accessed: May 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution.

- P. Brachet, L. T. Høydal, E. L. Hinrichsen, and F. Melum, “Modification of mechanical properties of recycled polypropylene from post-consumer containers,” Waste Management, vol. 28, no. 12, pp. 2456–2464, 2008. [CrossRef]

- H. Dahlbo, V. Poliakova, V. Mylläri, O. Sahimaa, and R. Anderson, “Recycling potential of post-consumer plastic packaging waste in Finland,” Waste Management, vol. 71, pp. 52–61, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Paiva, I. B. Veroneze, M. Wrona, C. Nerín, and S. A. Cruz, “The Role of Residual Contaminants and Recycling Steps on Rheological Properties of Recycled Polypropylene,” J Polym Environ, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 494–503, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Jansson, K. Möller, and T. Gevert, “Degradation of post-consumer polypropylene materials exposed to simulated recycling—mechanical properties,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 37–46, 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. Gall, P. J. Freudenthaler, J. Fischer, and R. W. Lang, “Characterization of Composition and Structure–Property Relationships of Commercial Post-Consumer Polyethylene and Polypropylene Recyclates,” 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Arese, B. Cavallo, G. Ciaccio, and V. Brunella, “Characterization of Morphological, Thermal, and Mechanical Performances and UV Ageing Degradation of Post-Consumer Recycled Polypropylene for Automotive Industries,” Materials, vol. 18, no. 5, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Traxler, H. Kaineder, and J. Fischer, “Simultaneous Modification of Properties Relevant to the Processing and Application of Virgin and Post-Consumer Polypropylene,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 7, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. W. Curtzwiler, M. Schweitzer, Y. Li, S. Jiang, and K. L. Vorst, “Mixed post-consumer recycled polyolefins as a property tuning material for virgin polypropylene,” J Clean Prod, vol. 239, p. 117978, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Velásquez et al., “Effect of Organic Modifier Types on the Physical–Mechanical Properties and Overall Migration of Post-Consumer Polypropylene/Clay Nanocomposites for Food Packaging,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 13, no. 9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Freudenthaler, J. Fischer, Y. Liu, and R. W. Lang, “Polypropylene Pipe Compounds with Varying Post-Consumer Packaging Recyclate Content,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 23, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Celina, “A Review of Polymer Oxidation and its Relationship with Materials Performance and Lifetime Prediction.,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 98, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. Wiles and G. Scott, “Polyolefins with controlled environmental degradability,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 91, pp. 1581–1592, Jul. 2006. [CrossRef]

- A. Kikuchi, J. P. Coulter, D. Angstadt, and A. Pinarbasi, “Localized material and processing aspects related to enhanced recycled material utilization through vibration-assisted injection molding,” J Manuf Sci Eng, vol. 127, no. 2, pp. 402–410, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Hinczica, M. Messiha, T. Koch, A. Frank, and G. Pinter, “Influence of Recyclates on Mechanical Properties and Lifetime Performance of Polypropylene Materials,” Procedia Structural Integrity, vol. 42, pp. 139–146, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Gooch, Encyclopedic dictionary of polymers, vol. 1. Springer Science & Business Media, 2010.

- F. C. Campbell, Structural composite materials. ASM international, 2010.

- Prior, M. S. A. Oliveira, and T. Zhiltsova, “Assessment of the Impact of Superficial Contamination and Thermo-Oxidative Degradation on the Properties of Post-Consumer Recycled Polypropylene,” 2023. [CrossRef]

- “ISO 1133 : 1997 Determination of the melt mass-flow rate (MFR) and the melt volume-flow rate (MVR) of thermoplastics,” 2000.

- Technical Committee ISO/TC 61 “Plastics” in collaboration with Technical Committee CEN/TC 249 “Plastics,” “ISO 11357-6:2018: Plastics – Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) Part 6: Determination of oxidation induction time (isothermal OIT) and oxidation induction temperature (dynamic OIT) (ISO 11357-6:2018),” Brussels, 2018.

- S. Jurado-Contreras, F. J. Navas-Martos, J. A. Rodríguez-Liébana, A. J. Moya, and M. D. La Rubia, “Manufacture and Characterization of Recycled Polypropylene and Olive Pits Biocomposites,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 19, p. 4206, 2022, [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/14/19/4206.

- G. W. Ehrenstein, G. Riedel, and P. Trawiel, Thermal analysis of plastics. Munchen, Germany: Hanser Publishers, 2004. [CrossRef]

- ASTM International, “D3895 − 14 Standard Test Method for Oxidative-Induction Time of Polyolefins by Differential Scanning Calorimetry.”.

- ASTM International, “Standard Test Method for Thermal Stability by Thermogravimetry E2550-11.”. [CrossRef]

- ISO, “ISO 527-2: Plastics — Determination of tensile properties — Part 2: Test conditions for moulding and extrusion plastics,” 1996.

- International Organization for Standardization, “ISO 527-1: Plastics — Determination of tensile properties — Part 1: General principles,” 2012.

- F. Kamleitner, B. Duscher, T. Koch, S. Knaus, K. Schmid, and V.-M. Archodoulaki, “Influence of the Molar Mass on Long-Chain Branching of Polypropylene,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 9, no. 9, 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Esmizadeh, C. Tzoganakis, and T. H. Mekonnen, “Degradation Behavior of Polypropylene during Reprocessing and Its Biocomposites: Thermal and Oxidative Degradation Kinetics.,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 8, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Douiri, H. Jdidi, S. Kordoghli, G. El Hajj Sleiman, and Y. Béreaux, “Degradation indicators in multiple recycling processing loops of impact polypropylene and high density polyethylene,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 219, p. 110617, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Jmal et al., “Influence of the grade on the variability of the mechanical properties of polypropylene waste,” Waste management, vol. 75, pp. 160–173, 2018.

- B. Veroneze, L. A. Onoue, and S. A. Cruz, “Thermal Stability and Crystallization Behavior of Contaminated Recycled Polypropylene for Food Contact,” J Polym Environ, vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 3474–3482, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Peterson, S. Vyazovkin, and C. A. Wight, “Kinetics of the Thermal and Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of Polystyrene, Polyethylene and Poly(propylene),” Macromol Chem Phys, vol. 202, no. 6, pp. 775–784, Mar. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Mihelčič, A. Oseli, M. Huskić, and L. Slemenik Perše, “Influence of Stabilization Additive on Rheological, Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Recycled Polypropylene,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 24, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Wypych, Handbook of Material Weathering. Elsevier Science, 2013. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.pt/books?id=dRGRmgEACAAJ.

- M. S. Rabello and J. R. White, “The role of physical structure and morphology in the photodegradation behaviour of polypropylene,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 55–73, 1997. [CrossRef]

- C. Luis De Carvalho, A. F. Silveira, D. Dos, and S. Rosa, “A study of the controlled degradation of polypropylene containing pro-oxidant agents,” 2013. [Online]. Available: http://www.springerplus.com/content/2/1/623.

- Gijsman and R. Fiorio, “Long term thermo-oxidative degradation and stabilization of polypropylene (PP) and the implications for its recyclability,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 208, p. 110260, 2023.

- N. Vidakis et al., “Sustainable additive manufacturing: Mechanical response of polypropylene over multiple recycling processes,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–16, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Sadik, F. ezzahra Arrakhiz, and H. Idrissi-Saba, “Polypropylene material under simulated recycling: effect of degradation on mechanical, thermal and rheological properties,” in Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Engineering & MIS 2018, in ICEMIS ’18. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Stoian, A. R. Gabor, A.-M. Albu, C. A. Nicolae, V. Raditoiu, and D. M. Panaitescu, “Recycled polypropylene with improved thermal stability and melt processability,” J Therm Anal Calorim, vol. 138, no. 4, pp. 2469–2480, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Y. Zhou, G. C. P. Tsui, J. Z. Liang, S. Y. Zou, C. Y. Tang, and V. Mišković-Stanković, “Thermal properties and thermal stability of PP/MWCNT composites,” Compos B Eng, vol. 90, pp. 107–114, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wattanachai, B. Buasathain, C. Antonio, and S. Roces, “Open Loop Recycling of Recycled Polypropylene for Motorcycle Saddle Application,” ASEAN Journal of Chemical Engineering, vol. 17, no. No 2, pp. 60–76, 2017, Accessed: May 08, 2025. [Online]. Available:. [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, “Mechanistic action of phenolic antioxidants in polymers—A review,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 181–202, 1988. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Peterson, S. Vyazovkin, and C. A. Wight, “Kinetics of the Thermal and Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of Polystyrene, Polyethylene and Poly(propylene),” Macromol Chem Phys, vol. 202, no. 6, pp. 775–784, Mar. 2001. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).