1. Introduction

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has shown substantial success in Multi-Agent Systems (MAS), with notable applications in robotics [

1,

2], gaming [

3], and autonomous driving [

4]. Despite this progress, sparse reward environments continue to hinder learning efficiency, as agents often receive feedback only after completing complex tasks. This delayed reward signal limits exploration and makes policy optimization difficult.

To improve exploration under sparse rewards, several strategies have been proposed, including reward shaping [

5,

6], imitation learning [

7], policy transfer [

8], and curriculum learning [

9,

10]. These methods aim to strengthen the reward signal and guide agents toward effective behaviors. While effective in single-agent environments, their performance often degrades in MAS, where multiple interacting agents exacerbate environmental dynamics and expand the joint state-action space [

11,

12,

13].

In response, we propose Collaborative Multi-dimensional Course Learning (CCL), a co-evolutionary curriculum learning framework tailored for sparse-reward cooperative MAS. CCL introduces three core innovations:

- (1)

It generates agent-specific intermediate tasks using a variational evolutionary algorithm, enabling balanced strategy development.

- (2)

It models co-evolution between agents and their environment [

14], aligning task complexity with agents’ learning progress.

- (3)

It improves training stability by dynamically adapting task difficulty to match agent skill levels.

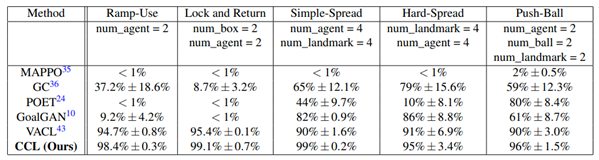

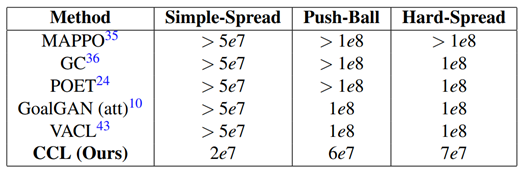

Through extensive experiments across five tasks in the MPE and Hide-and-Seek (HnS) environments, CCL consistently outperforms existing baselines, demonstrating enhanced learning efficiency and robustness in sparse-reward multi-agent scenarios.

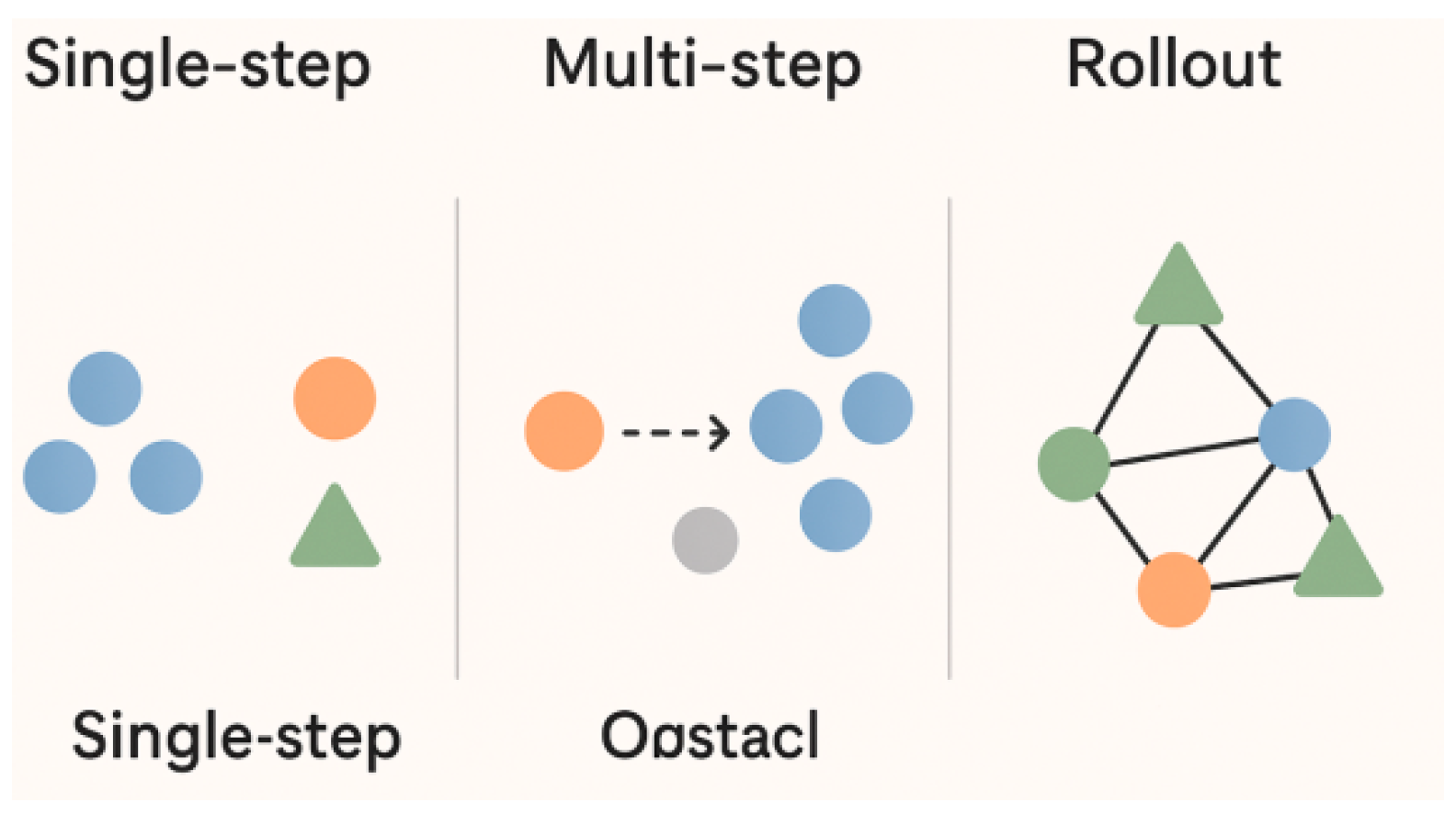

Figure 1.

MPE is validated with three different collaborative task scenarios.

Figure 1.

MPE is validated with three different collaborative task scenarios.

2. Problem Statement

In reinforcement learning, the reward signal is a critical feedback mechanism guiding agents to assess their actions and learn optimal policies via the Bellman equation [

15]. While a well-designed reward function defines the task objective and measures agent behavior, agents may still pursue suboptimal strategies. Nonetheless, carefully crafted rewards greatly enhance learning efficiency and policy convergence [

16].

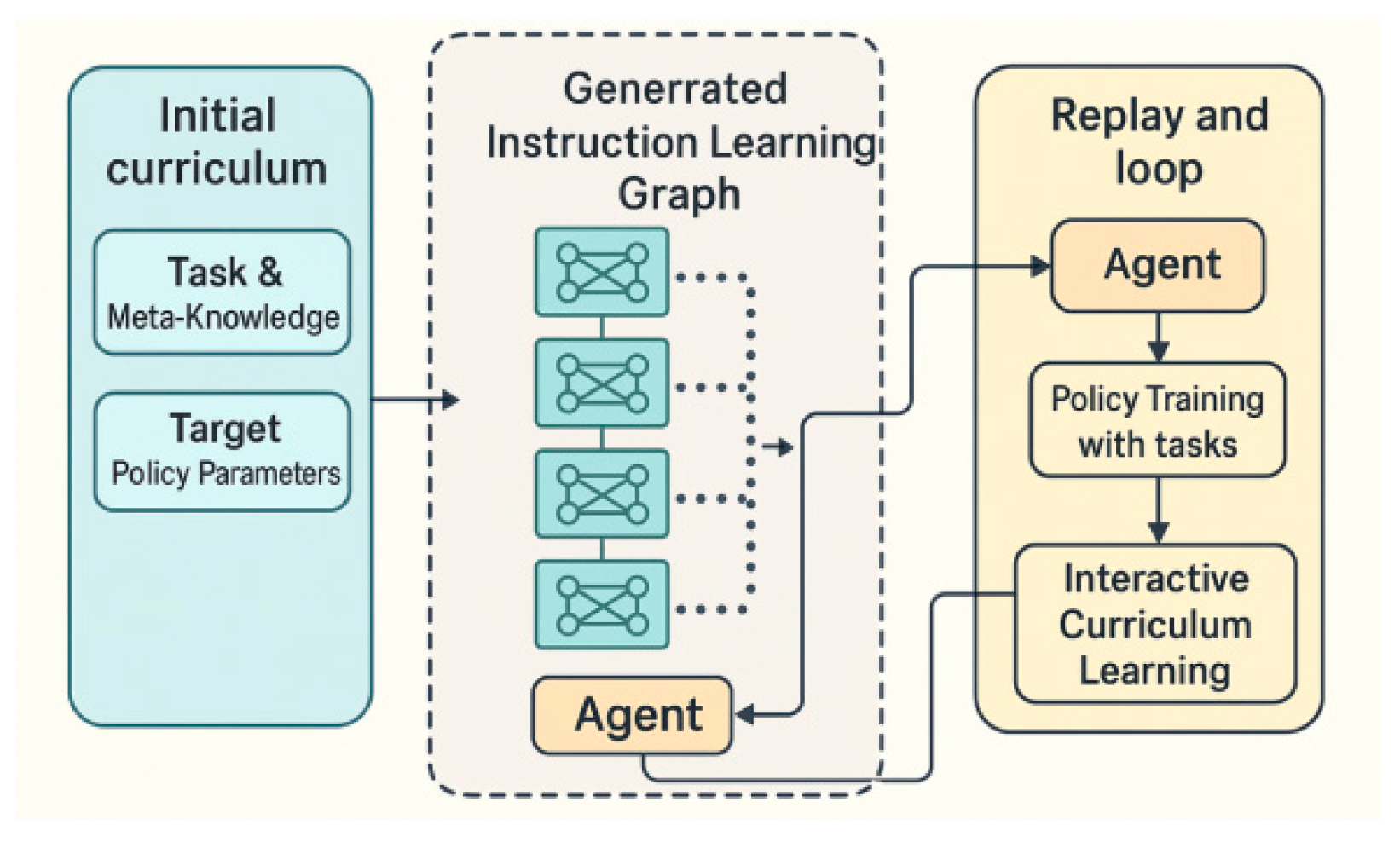

Figure 2.

Intermediate task generation in MAS is more complex than in single-agent settings due to the need to account for agent-specific subtasks. In sparse reward environments where rewards are shared, incorporating an individual perspective mechanism becomes essential to ensure effective task decomposition and learning.

Figure 2.

Intermediate task generation in MAS is more complex than in single-agent settings due to the need to account for agent-specific subtasks. In sparse reward environments where rewards are shared, incorporating an individual perspective mechanism becomes essential to ensure effective task decomposition and learning.

Designing dense rewards in complex MAS is challenging due to reliance on prior knowledge, which often fails to capture all interaction dynamics. Sparse rewards offer a more flexible alternative by providing feedback only upon reaching a critical goal state [

17], reducing dependence on manual reward design and improving generalization.

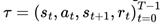

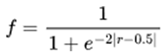

In non-sparse reward settings, at each time step

t, the agent observes its current state

and selects an action

based on its policy

. The chosen action results in a transition to a new state

st+1, determined by the environment’s transition dynamics

, and an associated reward

rt is obtained from the reward function

. The sequence of states, actions, following states, and rewards over an episode of

T time steps form the trajectory

, where

T is either determined by the maximum episode length or specific task termination conditions. This outlines the process of reinforcement learning for a single agent.

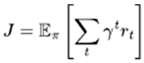

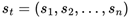

The goal of this individual agent is to learn and maximize its expected cumulative rewarded policy:

|

(1) |

where γ is the discount factor, representing future rewards’ diminishing value refinement degree of the optimization process is carried out by each time step inside the trajectory, that is, the optimization granularity is accurate to each time step.

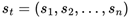

However, the system dynamics significantly intensify when extending this general framework to MAS under sparse reward conditions. In this system, there are

N decision-making agents, where each agent

i takes an action

ai at time step

t based on the observed state information and following its dedicated policy

. The global state st of the system is composed of the joint states of all individual agents, denoted as

. Correspondingly, the joint action

at at each time step is also formed by the combination of actions from all agents, i.e.,

. In the sparse reward environment, reward signals only emerge when the system achieves specific predefined goal states, posing more significant challenges for agent collaboration and strategy optimization.

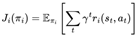

In cooperative multi-agent tasks, the goal of each agent is no longer focused on maximizing its reward but instead shifts toward optimizing the cumulative reward of the entire system. This requires agents to collaborate effectively, coordinating their actions to achieve the shared objective, thereby improving the overall performance of the multi-agent system. Consequently, the objective function

J for each agent

i is transformed into

, where

represents the reward received by agent

i at time step

t given the state st and joint action

at. The overall goal of the multi-agent system (MAS) then becomes the sum of the individual objectives, denoted as

.

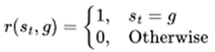

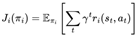

At this point, it becomes evident that the essence of a multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithm lies in utilizing the rewards earned by all agents to optimize the overall collaborative strategy. However, this challenge is significantly heightened in a sparse reward environment, where agents receive limited feedback, making it difficult to effectively guide their actions and improve coordination toward the collective goal. In the case that there are only very few 0-1 reward signals, the total reward of the system can be simplified to a binary function:

|

(2) |

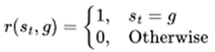

As the number of agents increases, training variance in MAS grows exponentially. In sparse reward settings, agents must achieve sub-goals aligned with a shared objective, yet often receive little to no feedback, making learning difficult. This lack of guidance hampers exploration and destabilizes training, rendering many single-agent methods ineffective. To address these challenges, we propose Collaborative Multi-dimensional Course Learning (CCL) for more stable and efficient multi-agent training.

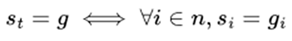

|

(3) |

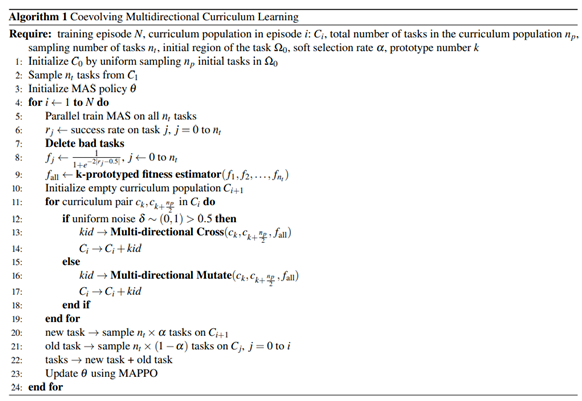

4. Methodology

4.1. The Variational Individual-Perspective Evolutionary Operator

In this section, we provide a detailed explanation of all the components of CMCL. As a coevolutionary system with two primary parts, the agents are trained using the existing Multi-Agent Proximal Policy Optimization (MAPPO) algorithm[

35], which will not be elaborated on here. The complete workflow of the CMCL algorithm is outlined in Algorithm 1.

Evolutionary Curriculum Initialization Due to the low initial policy performance of a MAS at the start of training, agents struggle to accomplish complex tasks. Therefore, minimizing the norm of task individuals within the initial population is essential. Assuming the initial task domain is Ω0, the randomly initialized task population should meet the following conditions, where d represents the initial Euclidean norm between the agent and the task, and δ is a robust hyperparameter, typically set to be about one percent of the total task space size.

|

(4) |

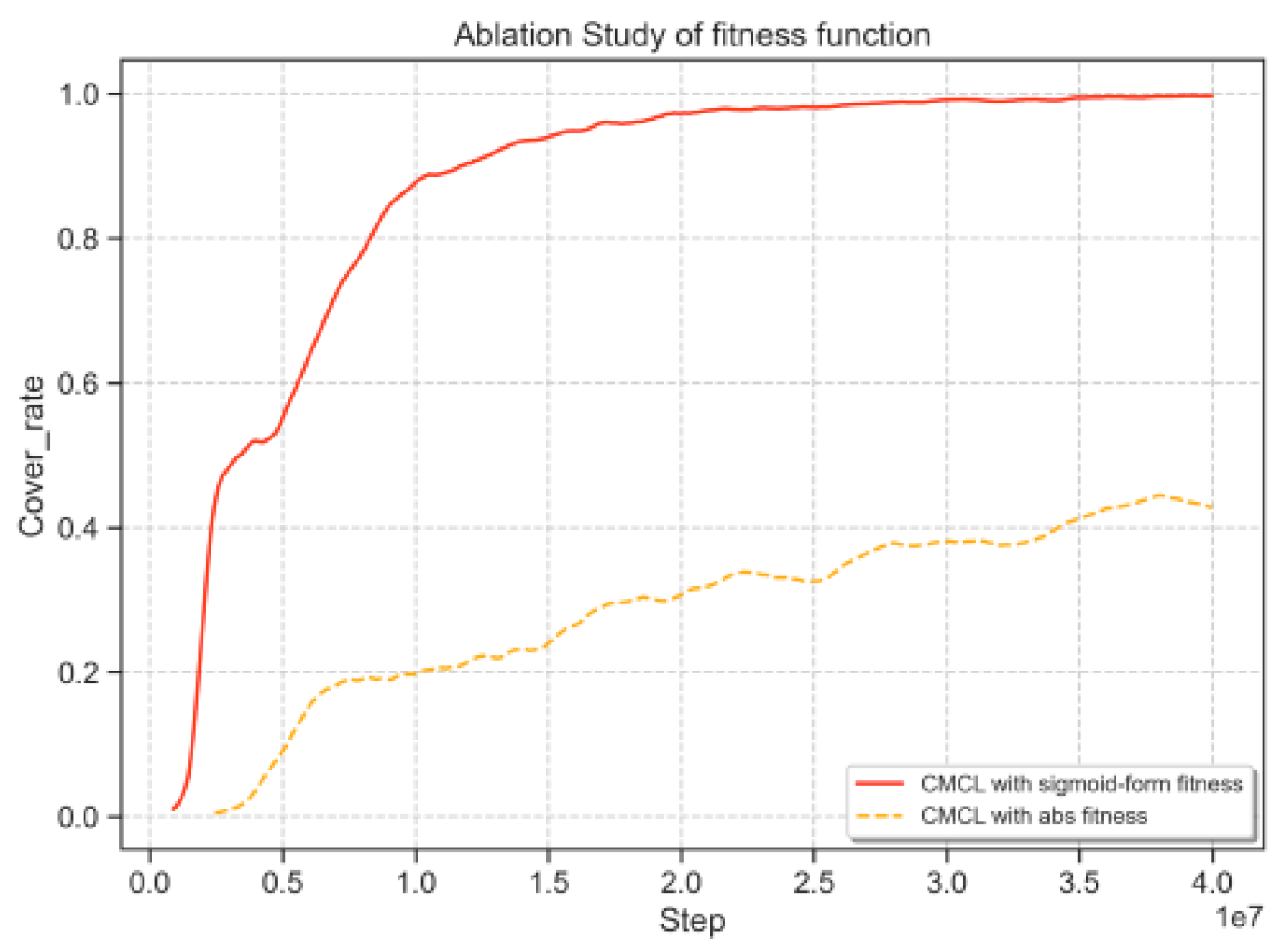

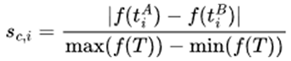

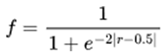

Task Fitness Definition: Previous methods often assessed intermediate tasks using agent performance metrics [

24,

30,

36] or simple binary filters [

37], which fail to capture the non-linear nature of task difficulty. Tasks with success rates near 0 or 1 offer little training value, while those closer to the midpoint present a more suitable challenge. To address this, we model fitness as a non-linear function, favoring tasks of moderate difficulty that best support learning progression. To capture this non-linear relationship, we establish a sigmoid-shaped fitness function to describe the adaptability of tasks to the current level of agent performance, where r represents the average success rate of the agents on task

t.

|

(5) |

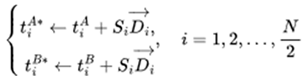

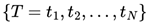

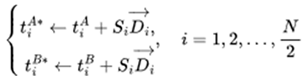

Variational Individual-perspective Crossover In a MAS, the single reward signal is distributed across multiple dimensions, especially from the perspective of different agents, leading to imbalances in the progression of individual strategies. Therefore, based on the encoding method mentioned earlier, operating on intermediate tasks at the individual level within the MAS is necessary. Assuming that in a particular round of intermediate task generation,

N individuals from the previous task generation

are randomly divided into two groups

TA and

TB. Then, we take

N/2task pairs

from and to produce new children in the population.

|

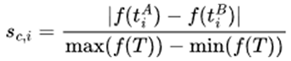

(6) |

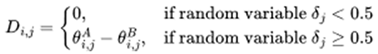

In the above formula,

si represents the crossover step size for pair

i, and

represents the crossover direction for pair

i. The calculations of

si and

are shown below:

|

(7) |

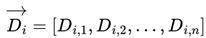

Di,j denotes the direction of the j-th agent in pair i, obtained by uniform random sampling.

|

(8) |

The proposed variational individual-perspective crossover ensures each agent's subtask direction contributes equally to curriculum evolution, enabling broader exploration compared to traditional methods. In a MAS with nnn entities, this results in 2n2^n2n possible direction combinations, enhancing diversity in intermediate task generation.

To address catastrophic forgetting [

38,

39], we adopt a soft selection strategy. Rather than discarding low-fitness individuals, the entire population is retained, and a fraction (α\alphaα, typically 0.2–0.4) of historical individuals is reintroduced each iteration. This maintains task diversity, preserves challenging tasks for future stages, and helps avoid local optima.

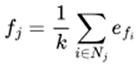

4.2. Elite Prototype Fitness Evaluation

Evolutionary algorithms often require maintaining a sufficiently large population to ensure diversity and prevent being trapped in local optima or influenced by randomness. However, evaluating the fitness of intermediate tasks in a large curriculum population significantly increases computational cost. To mitigate this issue, we propose a prototype-based fitness estimation method.

First, we uniformly sample tasks in each iteration and measure their success rate r and fitness f . These sampled tasks, called prototypes, are used in actual training. Next, we employ a K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) approach to estimate the fitness of tasks not directly used in training.

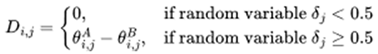

Assume there are m individuals in the prototype task set P, with fitness values fi for each i, and individuals in the query task set Q, represented as vectors qj for each j. For any individual qj in the query set Q, its fitness value fj can be calculated as shown below

|

(9) |

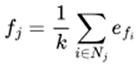

In the formula, Nj represents the set of indices of the k-closest individuals in the prototype task set P to the vector qj , based on the Euclidean distance. This can be expressed as follows:

|

(10) |

6. Conclusion

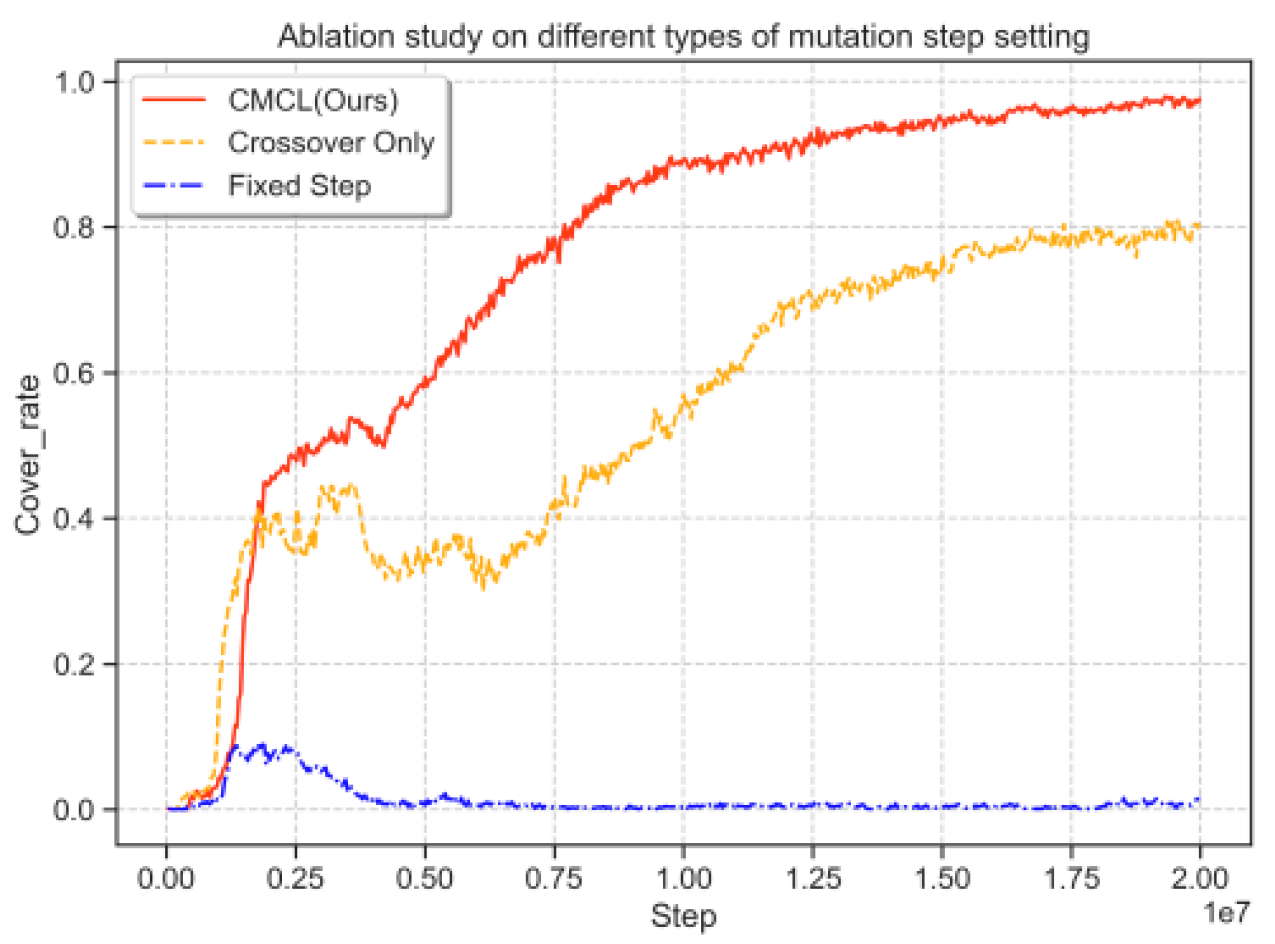

This paper presents CCL, a co-evolutionary curriculum learning framework designed to improve training stability and performance in sparse-reward multi-agent systems (MAS). By generating a population of intermediate tasks, using a variational individual-perspective crossover, and employing elite prototype-based fitness evaluation, CCL enhances exploration and coordination. Experiments in MPE and HnS environments show that CCL consistently outperforms existing baselines. Ablation studies further validate the importance of each component.

Despite its strengths, CCL’s current design is focused on cooperative MAS. Future work should explore its applicability in competitive or mixed-behavior settings, where coordination and conflict coexist. Moreover, the storage of historical tasks for soft selection increases memory usage; optimizing this via compression or selective retention is a promising direction for reducing overhead.

and selects an action

and selects an action  based on its policy

based on its policy  . The chosen action results in a transition to a new state st+1, determined by the environment’s transition dynamics

. The chosen action results in a transition to a new state st+1, determined by the environment’s transition dynamics  , and an associated reward rt is obtained from the reward function

, and an associated reward rt is obtained from the reward function  . The sequence of states, actions, following states, and rewards over an episode of T time steps form the trajectory

. The sequence of states, actions, following states, and rewards over an episode of T time steps form the trajectory  , where T is either determined by the maximum episode length or specific task termination conditions. This outlines the process of reinforcement learning for a single agent.

, where T is either determined by the maximum episode length or specific task termination conditions. This outlines the process of reinforcement learning for a single agent.

. The global state st of the system is composed of the joint states of all individual agents, denoted as

. The global state st of the system is composed of the joint states of all individual agents, denoted as  . Correspondingly, the joint action at at each time step is also formed by the combination of actions from all agents, i.e.,

. Correspondingly, the joint action at at each time step is also formed by the combination of actions from all agents, i.e.,  . In the sparse reward environment, reward signals only emerge when the system achieves specific predefined goal states, posing more significant challenges for agent collaboration and strategy optimization.

. In the sparse reward environment, reward signals only emerge when the system achieves specific predefined goal states, posing more significant challenges for agent collaboration and strategy optimization. , where

, where  represents the reward received by agent i at time step t given the state st and joint action at. The overall goal of the multi-agent system (MAS) then becomes the sum of the individual objectives, denoted as

represents the reward received by agent i at time step t given the state st and joint action at. The overall goal of the multi-agent system (MAS) then becomes the sum of the individual objectives, denoted as  .

.

are randomly divided into two groups TA and TB. Then, we take N/2task pairs

are randomly divided into two groups TA and TB. Then, we take N/2task pairs  from and to produce new children in the population.

from and to produce new children in the population.

represents the crossover direction for pair i. The calculations of si and

represents the crossover direction for pair i. The calculations of si and  are shown below:

are shown below:

. This improvement stems from the sigmoid function’s properties: as the agent’s success rate approaches 0 or 1, the task’s suitability to the agent’s abilities decreases exponentially. Specifically, when the success rate is exactly 0.5, the fitness value remains consistently at 0.5. This approach effectively integrates nonlinear elements into the success rate distribution, enabling the fitness function to more accurately represent the relationship between task difficulty and the agent’s skill level.

. This improvement stems from the sigmoid function’s properties: as the agent’s success rate approaches 0 or 1, the task’s suitability to the agent’s abilities decreases exponentially. Specifically, when the success rate is exactly 0.5, the fitness value remains consistently at 0.5. This approach effectively integrates nonlinear elements into the success rate distribution, enabling the fitness function to more accurately represent the relationship between task difficulty and the agent’s skill level.